CHARLES J. VAN SCHAICK AND HIS PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE HO-CHUNK

Matthew Daniel Mason

FOR MORE THAN SIXTY YEARS, professional photographer Charles Josiah Van Schaick (1852–1946) chronicled the lives of people in and around Black River Falls, Wisconsin. Beginning in 1879, he methodically captured images of his neighbors and friends who visited his gallery, as well as creating views of their homes and businesses. He also took informal snapshots that documented the changes and constancies in his community. His photographs provide especially rich visual documents of the Ho-Chunk. The studio portraits of tribal members depict them dressed in traditional regalia and contemporary fashions, as well as identifying themselves as indigenous peoples to the camera lens. Van Schaick did not systematically create portraits of Ho-Chunk. Instead, they patronized his business because he created fine images. His enduring role in the community allowed him to document generations of Native families.

Van Schaick left a rich photographic collection, but he did not leave any publicly accessible personal papers in the form of business records, journals, or correspondence. Consequently, much of his biographical and professional information derives chiefly from period newspaper accounts, as well as printed sources and the records of governmental and corporate bodies.1

The following briefly relates highlights from the professional life of Van Schaick and outlines the stewardship of his photographic collection by the Jackson County Historical Society in Black River Falls and the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison. It also discusses some of the different photographic formats used by Van Schaick to market portraits to his Ho-Chunk clients and identifies several of his contemporaries who also photographed Native Americans in Wisconsin and throughout North America. It concludes with a discussion of the portrait photography and the meanings a viewer may derive from these images as documents of the past.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF A PHOTOGRAPHER AND SHUTTERBUG CHRONICLER

Charles Josiah Van Schaick was born on June 18, 1852, in Manlius, New York. His parents were John B. Van Schaick (1818–1894), a farmer and butcher, and Sophronia Adams (1820–1877). Charles grew up a middle child with three older half sisters and an older brother, as well as a younger brother and sister. In 1855, his family moved to Springvale in Columbia County, Wisconsin, where Charles’s paternal grandfather, Josiah Robbins Van Schaick (1790–1864) had established a farm five years earlier. Charles was educated in a one-room schoolhouse near his family’s farm, and during his young adulthood he likely gained training as a schoolteacher.

In September 1872, his older brother, John Adams Van Schaick (1849–1875) married Florence L. Beedy (1856–1892), a sixteen-year-old schoolteacher from Albion, a small town west of Black River Falls in Jackson County, Wisconsin. Within two years, Charles moved to Albion and began courting Ida Adella Beedy (1858–1924), Florence’s younger sister. Ida taught at the nearby Wrightsville School, which served the towns of Albion and Alma, while Charles worked as a teacher four miles away in Disco.2

During this time, Charles explored different careers. In February 1877, he traveled to the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory with Ida’s father, Joseph S. Beedy (1841–1900) and local butcher Hiram B. Greenly (1841–1925) to sell smoked meat and dry goods for seven months in the mining camps. On returning from the Dakota Territory, Van Schaick temporarily returned to teaching. He then changed his career path from teaching to photography.

In June 1879, Van Schaick rented the photographic gallery formerly occupied by Edward P. Slater and began offering his services in Black River Falls. He probably received his training from Slater or from an “itinerant picture man,” who had offered to train individuals the previous year. By November 1881, a local news-paper reported that Van Schaick surprised “his many friends in the proficiency he has made in this art and the amount of business he is doing.” With the success of his gallery, Van Schaick married Ida on December 20, 1881. The next day they left for an extended honeymoon in Milwaukee, where he also took lessons in retouching photographs. Over the next forty years, they would raise three sons to adulthood.

In October 1882, Van Schaick hired an itinerant painter to paint backdrop scenes and build an ornamental stone balustrade; both appeared in nearly six decades of portraiture he created in his gallery. Painted backdrops were common fixtures in studio portraits. They typically consisted of an oversize painting on a heavy cotton weave or thin canvas with reinforced edges that included loops or ties to fasten the fabric tautly to a frame. Patrons posed sitting on the stone balustrade or on chairs and stools, or standing in front of painted backdrops.3 Other consistent features of Van Schaick’s portraits included sections of a rustic wooden fence, as well as blankets, rugs, and other set pieces such as liquor bottles, despite Van Schaick being an ardent supporter of temperance.

In September 1884, Van Schaick moved to a gallery on the second floor of the newly constructed “Independent Building,” located on Mason Street, later known as South First Street, in Black River Falls (see page 4). He remained at this location for the rest of his career. The skylight and sidelight for the gallery both faced north, which provided the studio with consistent light throughout the day. The waiting rooms offered a cooler space for customers during the summer despite its location on the second floor of the building. Nevertheless, the gallery was usually a jumble of frames and display cases filled with photographs.

In May 1885, Van Schaick’s father-in-law served as a government agent to the Ho-Chunk. This may partially explain why many of Van Schaick’s Ho-Chunk clientele had portraits created at his gallery. Studio portraits comprised a significant portion of his business; they encompass nearly sixty percent of his approximately 5,700 extant negatives, while portraits of Ho-Chunk people account for nearly one-third of the surviving studio work. Similar to other customers, Ho-Chunks bought portraits to place in their albums and to give to family and friends, as well as to mark events and occasions such as weddings and funerals.

Van Schaick also created informal photographs of powwows and tribal events of the Ho-Chunk, usually with a portable camera that he bought in May 1885 (see page 109). With this camera, Van Schaick captured candid images of everyday life in the city, which included informal portraits and extemporaneous townscapes. He created many street portraits of Ho-Chunk individuals and families that congregated on the streets of Black River Falls during the winter to collect their annuity payments from the federal government (see page 131).4

Charles J. Van Schaick sitting on a stone balustrade in front of a painted background, ca. 1882–1885. The photograph was probably taken by one of his assistants, Louis Sander, A. R. Cottrell, or S. Wohl.

The building that housed the gallery of Van Schaick and the dental offices of Edward F. Long, ca. 1890. Over the years, the building also accommodated a newspaper office and a telephone company.

Skilled in his craft, Van Schaick generally adhered to the same methods throughout his career. This included using primarily glass plate negatives rather than film negatives. Glass plate negatives consist of glass with a coating of a light-sensitive emulsion, while film negatives of the period have emulsion coated on a transparent flexible plastic material, usually nitrocellulose. Widely available after 1890, film negatives weighed considerably less and occupied less space than glass plate negatives, and proved instrumental in the development of portable cameras for amateur photographers.5 Van Schaick would routinely retouch the emulsion of glass plate negatives to remove facial flaws such as pock marks and wrinkles.

Though he did not make the switch to film negatives in his studio work, Van Schaick did not avoid all developments in photographic technology. He made some early experiments in stereoscopic photography, which uses two images captured simultaneously at slightly different positions to produce the appearance of three-dimensionality. He occasionally employed flashlight powder, a mixture of magnesium and other chemicals, which burned quickly to produce a bright white light to illuminate interior photographs. Around 1911, he began using a panoramic camera, which captured images encompassing a field of 140 degrees in 3½ × 12 inch exposures on a film negative (see page 112).

In addition to his photography business, Van Schaick participated in local politics. By June 1893, he became a court commissioner for Jackson County, and in April 1906, voters elected him as a justice of the peace. In this capacity, he served as a judge of a court that heard misdemeanor cases and other petty criminal infractions.

In his photographic work, Van Schaick documented major events in the region. For example, on October 6, 1911, following a month of intermittent rainfall and a continuous deluge the week before, the Black River flooded its banks. The floodwaters washed away eighty-five percent of the downtown district of Black River Falls and destroyed more than eighty buildings. The floodwaters spared his building, so Van Schaick had an advantage in creating photographs of the reconstruction of the downtown district from the vantage point of his gallery. Van Schaick demonstrated the scope of the destruction through photographs he created before and after the flood.6

Despite Van Schaick’s success as a businessman, the role of the town photographer began to lessen around the turn of the twentieth century. Since the 1890s, the development of film negatives and relatively inexpensive cameras had allowed amateur photographers to create their own portraits and views. Despite this, in 1913 Van Schaick sold a group of twenty-seven photographic prints, comprising mostly studio portraits depicting Ho-Chunk, to the Wisconsin Historical Society for $2.20.7 In November 1917, a local newspaper featured the oldest business owners in Black River Falls and stated, “C. J. Van Schaick was ‘making faces’ for the public and still stands by the camera.” Years later, another newspaper article reported that Van Schaick kept an eye on the Black River and he “watched the various moods and tenses of the river as long, if not longer, than anybody else here.”

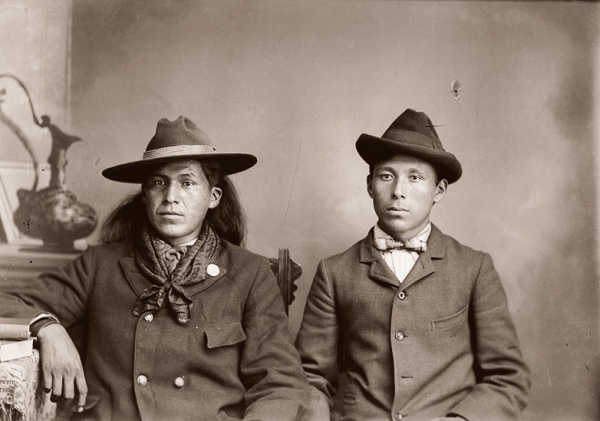

A glass plate negative and final studio portrait of Sam Carley Blowsnake (HoChunkHaTeKah), pictured with long hair, and Martin Green (Snake) (KeeMeeNunkKah), ca. 1910. The negative shows retouching Van Schaick applied to the emulsion around their faces.

Stereographic view of a man on Main Street in Black River Falls, ca. 1886, created by Van Schaick or his colleague Thomas T. McAdam.

On December 13, 1924, Ida Van Schaick died as a result of liver disease. In the decade following her death, Van Schaick continued to take photographs, but with less regularity. Over the years, he often visited his sons and their families, but he always returned quickly to Black River Falls.8

On June 16, 1942, Van Schaick sold his interest in the building that held his gallery to the Community Telephone Company of Wisconsin. He also retired after sixty-three years as a professional photographer, and more than forty years as a justice of the peace. With its purchase of the building, the telephone company acquired the contents of the gallery, consisting of thousands of photographic prints and an estimated nine thousand glass plate negatives. The company immediately donated the collection to the Jackson County Historical Society, which stored it in the basement of the public library. Nearly four years later, Charles Van Schaick died, on May 25, 1946, twenty-four days short of his ninety-fourth birthday and after a long career of documenting his community.

Informal portrait of Charles J. Van Schaick sitting by the window in his gallery, taken by his son Roy Van Schaick in 1942.

RECOVERING THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF VAN SCHAICK

After his retirement, the negatives and photographic prints created by Charles J. Van Schaick remained in relative obscurity in the basement of the public library. In 1954, workers renovating the telephone company building found another group of negatives and donated them to the Jackson County Historical Society. Stimulated by this discovery, local librarian Frances R. Perry (1897–1996) took on the daunting task of organizing the collection. She sought advice from Paul Vanderbilt (1905–1992), the recently hired Curator of Iconography at the Wisconsin Historical Society, for the best approach to organize and care for the collection. Vanderbilt advocated that she retain images that could “transmit ‘the feeling of its time,’ transmit personal experience, [and] give one the feeling (in [the] case of a portrait) of being there, face to face with that person.” Vanderbilt further suggested she discard duplicate or very similar images and suggested the Wisconsin Historical Society acquire superfluous material.

Over the next year, Perry worked with high school student volunteers to sort the photographs and negatives. She decided to discard broken glass plate negatives, as well as those with peeling emulsion, poor exposures, or scratches. They also discarded “uninteresting” negatives, which generally depicted people with no conspicuous features, probably including many unidentified studio portraits. The majority of these discarded negatives were taken to the town dump, while a smaller portion found their way into the personal collections of the volunteers and others. One volunteer recalls that they often made arbitrary choices. They also kept images that personally interested Perry: street scenes, women with children, and especially portraits of Ho-Chunk people, which reflected her personal interest in their language and culture. Perry also provided many of the identifications of Ho-Chunk in the images, often with her friend Flora Thundercloud Funmaker Bearheart. Many Ho-Chunk had a fondness and respect for Perry, and she was given a Ho-Chunk name, Blue Wing, by Adam Thundercloud.

Local photographer James Speltz (1923–1969) suggested the Jackson County Historical Society create 35mm copy slides from the original glass plate negatives, rather than photographic prints. He believed that creating modern photographic prints would require a large quantity of storage space, while constant handling would degrade their quality over time. More importantly, slides would allow the group to present slide shows for local groups. To ensure the best copies, Perry and the volunteers cleaned each negative. Speltz constructed a light box from a radio console and created over 2,200 individual 35mm slides from the glass plate negatives. The Jackson County Historical Society devoted portions of meetings to identifying locations and individuals in the images. For instance, at a meeting held at the Winnebago Indian Mission Church on November 30, 1961, fifty Ho-Chunk elders and their families identified many of the images of Native American people and activities. Other meetings took place over the ensuing years between elders and members of the historical society, as well as between Perry and individual Ho-Chunk people, to identify images.

In May 1957, Perry invited Vanderbilt to examine the negatives in the Van Schaick collection and select a portion for the Wisconsin Historical Society. He spent a week examining the collection and ultimately selected six boxes of glass plate negatives, making up nearly two thousand glass negatives. Since their acquisition, authors and publishers have used many of the images to illustrate publications throughout the world, ranging from textbooks to record album covers.

The most prominent use of the Van Schaick collection occurred when Michael Lesy used its imagery in his book, Wisconsin Death Trip (1973).9 This work, which also represents his dissertation for a doctoral degree in history at Rutgers University, has become a cult classic. It ostensibly relates social conditions and events in western Wisconsin during the last decades of the nineteenth century. For its source material, it chiefly uses items from the Badger State Banner newspaper in Black River Falls, Wisconsin, from 1885 to 1886 and 1890 to 1900, positing them among images created by Van Schaick, but manipulated by Lesy. Throughout Wisconsin Death Trip, Lesy provides a limited historical view of the region by explicitly shaping textual and visual source material to fit his preconception that “something very strange was happening” at the turn of the twentieth century.10 He particularly chafed at a nostalgic view of the period. For example, he argues in an early version of the work that the newspaper accounts “were considered neither sensational, nor exceptional when they were printed. If you will believe them, then at least you’ll be free of the good old days.”11

For his text in Wisconsin Death Trip, Lesy chose to highlight lurid excerpts from the Badger State Banner, medical records from a distant psychiatric asylum, and a hodgepodge of literary works by authors who did not live in the region. These works highlight the harsher features of rural life in the American Midwest on the precipice of the twentieth century, presenting a landscape run rampant with crime, disease, and insanity. Lesy manipulated sources, did not provide context for events, and infers a relationship between the photographs, newspaper accounts, and other sources.

Furthermore, Lesy selectively uses images created by Van Schaick in Wisconsin Death Trip in ways that the photographer and his customers would not have presented them. In a manner similar to the sensational newspaper accounts of his source material, Lesy manipulates original photographs through cropping, reversing, and creating montages that transmit his perception of insanity and death in a Wisconsin community. He thereby influences the way the reader interprets the imagery in a manner much different from the photograph in its original context. Lesy only uses a few images of Ho-Chunk in the work. These portraits include Flora Thundercloud Funmaker Bearheart (see page 48), a portrait of George Blackhawk with an unnamed man, and Thomas Thunder with his wife, Addie Littlesoldier Lewis Thunder (see below). While Lesy accurately presents most of these images, he does create a cropped montage of a detail from the portrait of George Blackhawk and an unidentified man, which implies that the former is missing the forefinger on his left hand.12 Overall, the text and images in Wisconsin Death Trip are a partial presentation of the past that encourages the reader to make misleading connections among unconnected material.

While the negatives at the Wisconsin Historical Society appeared in a variety of publications, the Jackson County Historical Society continued to care for its collection of negatives and photographic prints. In February 1968, it purchased the building that formerly held the photography gallery of Charles Van Schaick from the Community Telephone Company of Wisconsin. At that time a portion of the negatives and photographs made by Van Schaick returned to the place of their creation. During the winter of 1973 to 1974, likely stimulated by the publication of Wisconsin Death Trip, a team of volunteers supervised by Perry cleaned thousands of additional glass negatives.

Over the next two decades, the remaining glass negatives in the Van Schaick collections at the Jackson County Historical Society received relatively little attention from its members or researchers. After a series of discussions in 1994, the board members of the Jackson County Historical Society decided to donate nearly three thousand glass plate negatives to the Wisconsin Historical Society, which included the bulk of the portraits of Ho-Chunk. Nearly 115 years after Van Schaick began his career as a photographer and more than five decades after his retirement, most of the extant negatives reside in a single location and total around 5,700 negatives. The Jackson County Historical Society has retained a few glass plate negatives, which supplement its rich collection of photographic prints and copy slides of the negatives.

Studio portrait of George Blackhawk (WonkShiekChoNeeKah), sitting, and an unidentified man wearing an otter-fur hat, ca. 1895.

Studio portrait of Thomas Thunder (HoonkHaGaKah) and his wife, Addie Littlesoldier Lewis Thunder (WauShinGaSaGah), ca. 1915.

Beginning in April 1998, I volunteered to organize and describe the glass plate negatives in the Charles J. Van Schaick Collection at the Wisconsin Historical Society. Over six years, I individually inspected each negative, captured digital reference images, composed detailed descriptions of the images, and placed the negatives into photographically safe housing. In December 2008, I completed a dissertation enriched by my discoveries in the collection for a doctoral degree from the Department of History at the University of Memphis. Since then, the staff at the Wisconsin Historical Society continue to build on the work of Perry, Vanderbilt, and others to ensure that the work of Van Schaick will inform our view of his time and place.

MARKETING NATIVE PHOTOGRAPHS

Over the years, Van Schaick provided different photographic formats to his customers. These mostly consisted of photographic prints mounted on cardboard, known as card photographs. During the nineteenth century, card photographs were a popular way to present photographic prints, especially cartes-de-visite and cabinet photographs. The cardboard mounts of card photographs often have printed or embossed decorations or benchmarks that conveyed advertisements about the photographer or the studio and location, as well as any awards, areas of expertise, or prominent patrons (see page 10).

Cartes-de-visite derive their name from French calling cards and became a popular photograph format in the United States around 1860. They consisted of photographic prints that usually measure 2⅛ × 3½ inches mounted on cardboard measuring 2½ × 4½ inches. Carte-de-visite photographs remained a popular form in the United States into the early 1870s, when cabinet photographs eclipsed them. Cabinet photographs are larger than carte-de-visite photographs, usually 3½ × 5½ inches mounted on cardboard 4½ × 6¼ inches. Cabinet cards remained popular during the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Variants of card photographs continued into the twentieth century in a variety of dimensions.

During the early twentieth century, Van Schaick also offered his customers photographic postcards of their images. These consisted of a photographic print on postcard stock that generally measured approximately 3½ × 5½ inches. The Eastman Kodak Company first marketed this format to amateur photographers in 1903, and its competitors soon followed suit. The format remained popular until around 1930. Other photographers used the format to supplement their gallery business by creating postcards for sale to tourists. For example, a contemporary photographer of Van Schaick, Arthur Jerome Kingsbury (1875–1956), worked in Antigo, Wisconsin. He created a series of informal portraits on photographic postcards of Menominee on the Menominee Indian Reservation in northeastern Wisconsin, circa 1907–1909, which he marketed to tourists. Van Schaick apparently did not market postcards of Ho-Chunk or other images to tourists. Some businesses in Black River Falls and Jackson County did use images created by Van Schaick in mass-produced postcards as advertisements, but these were not generated by him for distribution. Still, Van Schaick did maintain a stock of photographic postcards for his Ho-Chunk customers tacked on a wall in his gallery for sale. Ho-Chunk patrons would then buy these postcard images of their family and friends. Many vintage prints in family collections have pinholes in them that reflect this marketing of images to Ho-Chunk clientele.13

Other professional photographers contemporary to Van Schaick created portraits of Ho-Chunk in Wisconsin, although they did not create portraits in a similar quantity. For example, Henry Hamilton Bennett (1843–1908) of Kilbourn City, later known as Wisconsin Dells, was a photographer active from 1866 until his death. He created several images of local Ho-Chunk to publicize the natural wonders in and around the Wisconsin Dells, but they only account for several dozen images. Another contemporary photographer in Wisconsin, David F. Barry (1854–1934), operated a gallery in Superior after he sold his gallery in Bismarck, Dakota Territory, in 1883, where he created iconic portraits of Sitting Bull and other Dakota Indians.14

Other photographers contemporary to Van Schaick explicitly sought to document the Native peoples across the continent. Most notably, Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868–1952) sought to record the traditional lives of Native peoples during the first three decades of the twentieth century. This led to the publication of his twenty-one-volume series, The North American Indian (1907–1930), in which Curtis presented images of Native culture and costume in the wake of the transcontinental expansion of the United States. Overall, the work presents Native peoples as historical features of a landscape and apart from contemporary society. Another midwestern photographer, Frank Albert Rinehart (1861–1928), collaborated with his assistant Adolph F. Muhr (circa 1860–1913) to document representatives from Native groups attending the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1898. Some Native peoples also operated galleries and documented their communities. For example, in Oklahoma, Kiowa photographer Horace Poolaw (1906–1984) documented changes in Native life from 1923 until sometime after 1955.15

Cabinet photograph with a studio portrait of Emma Lookingglass Greengrass (ChayHeHooNooKah) sitting in front of, left to right, an unknown man, Howard Joseph McKee Sr. (CharWaShepInKaw) holding a small revolver, and Louis Johnson (HaNuKaw), ca. 1895. McKee and Johnson were on the rolls of the Nebraska Winnebago (Ho-Chunk).

ENGAGING IMAGES OF THE HO-CHUNK

Like many of his contemporaries, Van Schaick clearly possessed a measure of respect and admiration for his Ho-Chunk customers and neighbors. This becomes particularly evident when viewing individual portraits and exploring the levels of meanings within them. The moment between the portrait photographer and their subjects becomes salient in the image that develops from it. In front of the camera, the subject of a portrait usually suspends their naturalness and impulsiveness to present the best image of themselves to the photographer and the eventual recipient of their visage. By extension, the photographer becomes an inextricable part of the captured frame through framing, lighting, and exposure.

Portrait photographs allow the viewer to see individuals in the past through a frame and perspective they created with the photographer. With portraits of American Indians, common cultural knowledge provides some standard for interpreting images. Consider the portrait of Benjamin Raymond Thundercloud (born circa 1896) created around 1915 (see page 45). The young man wears a headdress of eagle feathers, a woodland floral breechcloth, beaded belt, rings, bracelets, and moccasins, and he holds a pipe bag. His physical features, clothing, and accoutrements embody an American Indian. Viewers read the image and create a probable context based on shared cultural perceptions.

Still, reflecting traditions of other indigenous peoples, Ho-Chunk individuals inter-married with other cultures and groups, as well as adopting some non-indigenous peoples into the nation. For example, Carrie Elk (born circa 1888) had a mixed racial heritage of African American and Ho-Chunk but wholeheartedly identified herself as Ho-Chunk—she was raised by her Ho-Chunk grandparents and spoke primarily Ho-Chunk. Her portraits with other women also attest to her self-identification as a Ho-Chunk (see pages 172 and 173).

In addition to common cultural knowledge, documentary evidence provides context for interpreting portrait photographs. This may include knowledge of the date, time, perspective, and subject captured in the image, as well as the equipment used in making photographs and the uses of the prints. This contextual knowledge becomes less necessary when viewing and appreciating photographic images on purely aesthetic merits, but the documentary context adds dimension to its depth or meaning. For example, in the portrait of two men on page 5, the man on the right is identified as Martin Green or Martin Snake, and the man on the left is Sam Carley Blowsnake (born circa 1876), also known as Crashing Thunder. Blowsnake was described as a well-known member of the Ho-Chunk Nation in “Autobiography of a Winnebago Indian,” transcribed and edited by anthropologist Paul Radin (1883–1959) in the early twentieth century. This autobiography and other accounts provide much of the anthropological information known about the nation.16 In this portrait, although dressed in modern clothing, the men distinguish themselves as Ho-Chunk by their physical characteristics. This is particularly the case with Blowsnake’s long hair, which mirrored hairstyles of Native American men of the Great Plains. Long hair was not traditionally worn by Ho-Chunk men at that time, so Blowsnake probably grew it while working as a performer with Wild West shows to signify a Native American identity among the other performers.

Van Schaick and his contemporary photographers often positioned their subjects following the conventions of portraiture. This often delineated hierarchy, authority, and subordination in the arrangement of individuals in a frame, especially in family groups, arranging men, women, and children in positions and relationships to each other. Historian Alan Trachtenberg points out that “group portraits come laden with a surplus of information, but there’s always something more we want to know—about the group’s history, its inner dynamics.”17 For example, consider the portrait of five Ho-Chunk men—four men posed sitting and one man standing—as well as a white man, circa 1905, from a photographic print by another photographer that Van Schaick copied for a customer (see page 111). All of the men wear traditional regalia, including beadwork clothing, necklaces, earrings, and feathers, while the white man additionally wears a hat. The portrait raises many questions: Who are these men? Why group them together? In fact, these men toured and performed in traveling Wild West shows organized by the white man in the photograph, Thomas R. Roddy (1860–1924), also known as White Buffalo, who traded extensively with the Ho-Chunk.18

Portrait photographs possess aesthetic qualities that can distinguish them. Images that depict frontal views possess a greater aura of authenticity. The eyes of the subject and the photographer—and by extension the viewer—meet and provide a forthright acknowledgment of the portrait process. In other examples, averted glances and expressions may create a sense of intimacy in the image. The two portraits of George Hindsley (1887–1967) on a single negative, circa 1900, express the different senses of this individual.

Developments in the technology of photography also reduced exposure times for negatives. This allowed amateur and professional photographers to capture spontaneous emotions and movements, which proved especially useful in photographing children, whose frequent movement often blurred their portraits. In a portrait of two Ho-Chunk girls, identified as Maude Browneagle and her sister, Liola, the instantaneous shutter captured a moment of their childhood (see page 250).

The images of Ho-Chunk captured by Charles J. Van Schaick document the different ways individuals identified themselves as indigenous peoples in front of the camera lens. The photographs show the relationships within families and between individuals. By providing contextual information, the following pages pay homage to the work of Van Schaick and the Ho-Chunk individuals in these images.

Dual studio portrait of George Hindsley (AHoShipKah), ca. 1910.