HOWARD W. BUFFETT

Debate between scholars and practitioners over the need to shift broad economic development policy and implementation toward regionally contextual, place-based strategies has intensified over the past decade.1 Interest and investment in place-based initiatives among funders, ranging from economic development institutions,2 to private and family foundations,3 to U.S. government agencies,4 has helped fuel this debate. Neither the concept nor practice is new, but the financial crisis and great recession of 2007–2009 prompted reexamination of traditional economic development models.5 As a result, place-based initiatives received greater attention, including new research and expanded dialogue by think tanks6 and academic institutions.7

Initiatives are often considered place-based when they bring together multiple partners and stakeholders to develop long-term, comprehensive strategies that support or revitalize a defined geographic area8 such as a neighborhood or a community.9 These initiatives attempt to improve social conditions by integrating contributions from funders, implementers, and stakeholders. They form and interconnect programs and services in the given place, often using a common analysis framework for defining and evaluating measures of success.10 In effect, place-based initiatives are intended to concentrate and coordinate resources, and when designed well, they empower local stakeholders and engage them in the design and implementation of how those resources are deployed.11

The programs in the Afghanistan case exhibited many of the characteristics of a place-based approach. Partners coinvested their time, energy, and resources in a set of interconnected programs in and around the city of Herat. Stakeholders in the area worked together with government agencies, foundations, NGOs, and others to design, plan, and carry out the overall partnership. Local entities, ranging from community councils to the public university in Herat, took ownership of the projects, determined program governance, and codeveloped priorities and time lines with the other partners. The initiative’s funders and implementers entered the partnership with a specific mentality, treating the community and other stakeholders as true shareholders, or permanent co-owners of the investments being made.

Overall, the approach was supported by an important sense of place, it built on a disposition of longevity, and it engendered stewardship among all partners over shared resources.12 The management approach of this particular case, and the resulting collaborative attitude between partners, may have been somewhat unusual, but we believe the lessons from its stakeholder focus are important.13 This focus built trust and encouraged cooperation between community members and local organizations, and it prompted partners to emphasize programs and investments that would yield positive results over the long run. Each of these aspects, fundamental to the social value investing approach, was critical to the initiative’s overall success.

In this chapter we will explore ways in which funders, implementers, and stakeholders can work together in partnership through commitments to candid and open dialogue, accountability, and active participation between teams. We discuss ways to support inclusive engagement and consensus building through a joint scoping exercise, and the need for principles that reinforce collaborative ownership. Finally, we outline a process for partners to mutually determine how they prioritize projects through a scoring methodology based on partners’ preferences and priorities. This common analysis framework, called the Impact Balance Sheet, is a tool that helps partners cooperatively evaluate program options and plan activities throughout the life cycle of a partnership.14

INCLUSIVE PLANNING REQUIRES INTENTION

Cross-sector partnerships involve participants from numerous organizations differing in size, scope, and mission, and with differing timetables and priorities.15 These participants have to collaborate under diverse leadership styles, and they have to balance their organization’s respective objectives, requirements, and resources while working toward common goals. However, few organizations have adopted norms, guidelines, or standard operating procedures for how they will plan and interact with other participants in a cross-sector partnership.16 This is especially important when collaborative efforts involve neighborhoods, community-based organizations, or individual stakeholders with a highly vested interest in the activities or outcomes of the partnership.17 The absence of widely established principles for stakeholder inclusion in place-based development can result in stakeholder disenfranchisement, can lead to harmful unintended consequences, or can create resistance to a partnership’s objectives.18 Not only does this present moral considerations,19 it is also problematic when solutions to complex societal challenges require the willful, active, and coordinated participation of many diverse individuals and organizations.20

Almost by default do investors or donors enter a partnership in a position of power or control because they can stipulate requirements for their funding.21 Often this allows them to set the agenda, determine the goals, unilaterally make major capital allocation decisions, and even micromanage the activities of other partners.22 As a result, funders may end up imposing their approaches or beliefs on the cooperating organizations whether or not those views are accurate or appropriate for a given context.23 This means a partnership’s goals may be overly “top down,” may fail to account for stakeholder preferences or customs, or may fail to identify a problem’s root causes.24 Similarly, when implementation partners respond to requests for proposals or tenders, it positions them to prioritize the wishes and perspectives of the funder above all others. In these cases, delivery of a partnership’s programs could be based on misperceptions, uniformed assumptions, or biases rather than on a community’s true needs or interests.25

For cross-sector partnerships to be effective at providing lasting solutions to problems facing society, funders, implementers, and stakeholders alike must be involved in a partnership’s decision-making process.26 As was done in the Afghanistan case, leaders and participants across organizations should view partnerships as a long-term coinvestment of their time and resources, and stakeholders should be treated as co-owners of the partnership’s outcomes.27 Partners should mutually design the scope of the partnership, develop and follow cooperative principles, and determine agreed-upon responsibilities between participants.28 Doing so will result in an effective partnership strategy that guides the goals, implementation, and outcomes of the engagement, as well as its governance and the resolution of conflict.29

COOPERATIVE PRINCIPLES FOR PLACE-BASED COLLABORATION

Teams in a partnership have unique underlying core identities, and what goes into developing and strengthening those identities is outlined in chapter 6.30 For example, teams often engage in important rituals that maintain team cohesiveness, and they hold loyalties toward their organization, fellow members, or leaders. Teams strive toward ideals and values, and team members all go through a variety of shared emotional experiences together. Finally, teams often share a set of common principles that guide their thinking and the execution of their work.

Similarly, partners working collaboratively must share a set of common principles to guide their cooperation throughout the partnership. Funders, implementers, and stakeholders will have diverse preferences and priorities that may come into conflict, and cooperative principles are critical for supporting ongoing work at challenging times. As collaborative efforts become increasingly complex, cooperative principles can help guide ongoing program development and support effective teamwork between partners. The following principles are relevant to cross-sector partnerships engaging in place-based strategy deveopment:31

Inclusive Engagement. Effective planning of place-based strategies includes as many stakeholders as possible who have a vested interest in the activities and outcomes of the partnership. Partners should conduct exercises to assist with stakeholder identification, mapping, and assessment to help develop engagement strategies. Partners also may conduct scoping exercises to outline programs and help guide decision making early in the partnership. The scoping method (discussed later in this chapter) can assist partners in understanding partnership activities and outcomes in relation to stakeholder preferences and priorities. This is especially important due to the imbalance of power among partners; funders and implementers must embrace inclusive participation and allocate time and resources for consensus building. Doing so benefits the partnership by helping to avoid barriers and opposition to program selection.32

Committed Leadership. Organizations and stakeholder groups working together must have leaders committed to the goals and outcomes of the partnership. These leaders must establish teams responsible for specific activities and outputs throughout the time line of the partnership, otherwise the collaboration itself is unlikely to survive. Each partner should identify the individuals, including representation from their organization’s senior leadership, who will support inclusive engagement and advance partnership goals. Leaders should invest time outside of their partnership teams as well so the goals of the partnership are fully understood and embraced by the entire staff of participating organizations.33

Mutual Accountability. Initiatives must articulate methods of accountability between partners’ respective ownership teams and the stakeholders or members of the local community engaged in the partnership. Partners must mutually develop a set of high-level guidelines to support one another during partnership development and to help establish appropriate expectations regarding program activity. These guidelines may govern conduct between members or outline specific responsibilities undertaken by the partners. The resulting responsibilities must take into account the differing roles, strengths, and activities of funders, implementers, and stakeholders within the partnership.34

Recognition of Progress. Designing, building, and managing cross-sector partnerships is complex and difficult work that requires ongoing effort. Sometimes partnerships occur over protracted periods with lengthy program time lines that can suffer from stagnation or lead to partner disengagement. Teams and communities alike benefit when milestones are celebrated, partners are brought together frequently, and progress is recognized toward the partnership’s goals. Continually recognizing progress is self-reinforcing—it encourages ongoing participation, supports consensus building, and encourages participants to constantly build on relationships and reinforce mutual commitments.35

Participatory Decision Making. Inclusive partnerships use open and transparent processes to guide governance; this is particularly important for program selection criteria. Effective place-based strategies draw from evaluation models developed cooperatively across partners and stakeholder groups. Similar to the analysis framework outlined later in this chapter, these models help partners customize measures of success, analyze program options, and revise objectives as necessary. To avoid inadvertently excluding stakeholders, the funders and implementers in a partnership must actively support necessary participatory decision-making activities. Initiatives must incorporate ways in which participants can constantly share information and engage in open and honest dialogue.36

Continual Improvement. Partnering organizations must support methods for continual process and program improvement throughout strategic planning and partnership implementation. Resources will be required to develop tools and methods to monitor, evaluate, and report the progress of programs. Partners must ensure there are opportunities for communities or individuals to contribute ideas, viewpoints, and commentary throughout the life cycle of the partnership. Furthermore, initiatives must use effective feedback loops to capture lessons learned, share insights across organizations and individual stakeholders, embrace best practices, and avoid unnecessary activity or the duplication of efforts.37

This is not an exhaustive list, and partners are encouraged to expand on these principles in ways that are relevant for their specific programs and working environments.

Creating an effective and collaborative environment for participants in a cross-sector partnership relies on principles with a common theme: stakeholders must be proactively engaged throughout the design, development, and deployment of place-based strategies.38 Funders and implementers must be inclusive and welcoming of stakeholders ranging from community individuals to local political leadership to community-based organizations to neighborhood associations and beyond.

ESTABLISHING THE SCOPE OF A PLACE-BASED PARTNERSHIP

Including multiple partners and stakeholder groups in partnership planning and engagement helps align their activities and goals around a common mission and set of shared objectives. Partners who understand each other’s preferences and priorities are more likely to respect differences, overcome potential conflict, and appreciate diverse viewpoints.39 Knowing each partner’s perspectives regarding the type and scope of programs that align with their mission means that partners will be better equipped to plan inclusively.40

A value chain analysis identifies gaps that a partnership can fill, and the logic flow model outlines inputs, activities, and outputs required to accomplish a partnership’s outcomes (see chapter 4). Both should be developed in a cooperative manner; however, neither tool includes elements of partner preference (such as ideal program scale) or operational or mission-related priorities (such as program time lines) in the planning process. Engaging funders, implementers, and stakeholders in a scoping exercise can add those dimensions and provide commonality for exploring respective viewpoints.

In our examples of partnerships throughout the book, initiatives show a higher degree of success when partner’s preferences, priorities, and collective actions are harmonized across participants. The thoroughness and inclusivity of partnership planning often governs this harmony and affects whether partners remain engaged, programs meet objectives, and partnerships provide lasting outcomes over time.41 In particular, funders and implementers in our examples support stakeholder-led development of program plans, or ensure program alignment with existing plans, so that activities reflect stakeholder needs and desires.

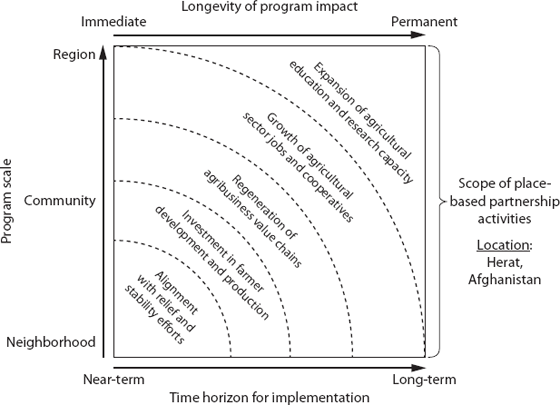

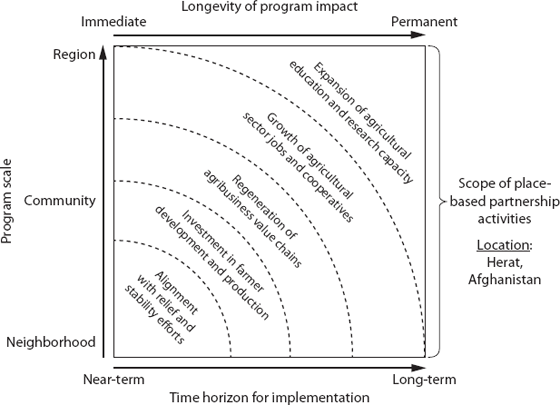

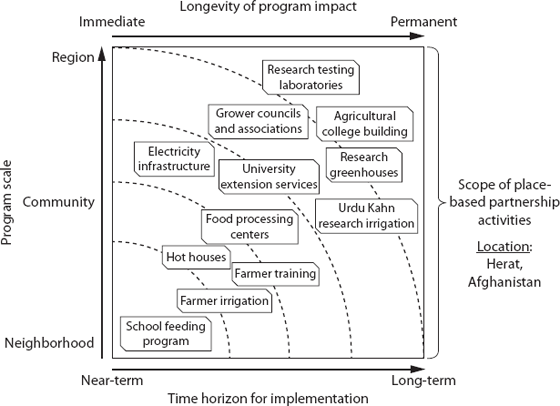

Figure 8.1 illustrates the scope of activities in a place-based partnership. These partnerships have a defined geography, or place (the y axis), have defined program time lines (the lower x axis), and are comprised of programs with differing degrees of impact (the top x axis). This chart shows the generalized relationship between those factors and enables funders, implementers, and stakeholders to collaboratively plot their activities within the scope of the partnership regardless of their respective role, sector, or mission. Partners may begin by outlining the partnership’s goals or objectives on the chart. This example includes strategic and program focus areas from the place-based strategy in the Afghanistan case.

Figure 8.1 A scoping exercise allows partners to plot multiple aspects of a place-based partnership, as seen in this example based on the Afghanistan case. Strategic focus areas falling further along the right of the x axis generally require more time to implement but have a higher potential longevity of impact. The y axis delimits the potential or targeted geographic scale of reach, and these values can be exchanged for varying scales (for example, a range from city block to citywide, or from province to multinational).

In Afghanistan numerous organizations worked alongside one another. These groups operated programs meeting different needs, and their preferences and priorities are represented by different areas in the figure. For example, food aid and relief efforts were operated by the United Nations World Food Programme located at small primary schools. The administrator overseeing those school-level programs, or a leader in charge of a nonprofit providing similar programs, may prioritize how many hungry mouths get fed in a given day and the next. They may prefer working at the individual school level due to local logistical constraints and the ability to cluster other services on site. Activities such as these provided an important quick-response stabilization function in our case and fall into the lower left area in the chart.

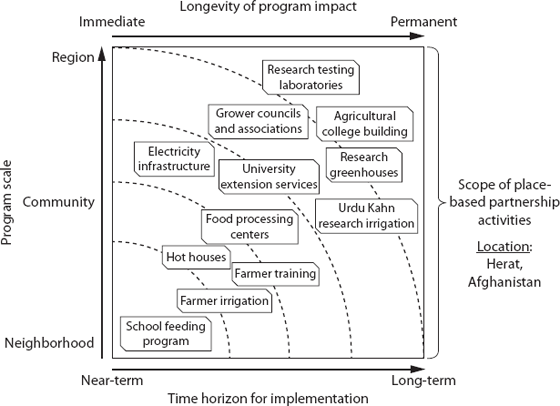

The Department of Defense (DoD) team worked closely with communities of farmers at the village level on training and the installation of irrigation infrastructure. Local governance councils were most interested in program options that would have a fairly quick and direct impact on their crop production, therefore leading to increases in income and village-level prosperity. The team also worked with small groups of women entrepreneurs whose preference was to serve a broader population than that of the farmer-based programs. In tandem with the governance councils, these entrepreneurs formed cooperative food processing centers to provide the community with access to value-added food products. These centers were supplemented by somewhat limited-use, but important hot houses that extended growing seasons for processed crops. Overall, these activities fall higher on the chart’s program scale than the school feeding programs, but they took longer to implement. As reflected in figure 8.2, the depth of the effect of the food processing centers on the community was expected to be similar to that of the farmer irrigation projects in their respective villages.

Figure 8.2 The scoping chart illustrates specific programs across strategic focus areas, as seen with this mapping of activities depicted in the Afghanistan case.

A collaboration between Afghanistan’s Ministry of Agriculture and Herat University led to the development of multiple farmer-owned cooperatives, which were organized under the Herat Cooperative Council Growers Association. The association reached across multiple communities in the area, and over time it improved the quality of crop production and supported more stable local commodity markets. Program participants received training and new knowledge through increased university extension services and access to research conducted at new university greenhouses. Furthermore, partners worked closely with the city and provincial government in Herat, which increased political support for the university’s new programs and the village- and community-level initiatives. For example, a local politician committed resources for new electricity supply and infrastructure serving the partnership’s projects east of the city of Herat. Not only did this deliver improved services and assistance to his constituents, it provided the official with a widely visible “quick win,” which is plotted in the upper left area of figure 8.2.

Finally, partners made numerous long-term investments in agricultural research and educational capacity at Herat University’s College of Agriculture. The university and the Ministry of Agriculture both had an interest in supporting knowledge development that would span a multiyear time horizon. This interest included long-term, advanced research needs and new opportunities for students in relevant areas of study. High-tech laboratories for commodity and soil testing provided services to local farmers and cooperatives and led to important advanced research data for improving crop production at a regional level.

Based on this outline, we can plot Herat’s place-based programs and activities across figure 8.2.

In the Afghanistan case, all partners worked well together, but this type of seamless integration is more often an exception than the norm. A frequent challenge in partnership building is conflicting implementation schedules and objectives for desired outcomes between teams.42 Because of differing preferences and priorities, teams must work collaboratively to ensure that early or small-scale activities support strategic objectives and the resiliency of the partnership’s programs over time. Concurrent programming should be considered throughout the continuum of short-, to medium-, to long-term planning efforts, ranging from actions that meet immediate needs to ones that coordinate community resources, address policy changes, or expand enabling systems or infrastructure. Engaging in inclusive planning helps groups look beyond individual constraints—such as limited resources, information, influence, or time—and illustrates how coordinated action supports the accomplishment of a partnership’s goals and outcomes.

MUTUAL ACCOUNTABILITY AMONG PARTNERS

Partners in a successful place-based strategy maintain mutual accountability to one another and support ongoing cooperative action among participants.43 Effective place-based partnership strategies establish high-level expectations regarding important conduct that is representative of the partnership’s scope and in line with its collaborative principles. This conduct can be governed by operational standards and responsibilities agreed on by the partners, and may be customized and expanded so it is relevant to the nature of specific programs in a given partnership. These standards and responsibilities should be mutually developed and accepted by all participants involved in the engagement, whether they are funders, implementers, or stakeholders.44 We have found that the following list of accountability practices, grouped by partner role, has led to successful partnerships.

Funders

Organizations assuming the role of investor or donor in a partnership (such as foundations, corporations, or government entities) should consider the following practices:

■ Allocate funding for or make up-front investments in the development of human capital in implementation partners or stakeholder groups if needed. In some cases, this may take a significant amount of lead time and may include training or knowledge transfer for partnering teams or team leaders. Or it could include local or regional capacity building, infrastructure investment in academic or research institutions, or the development of a new knowledge base necessary for making informed decisions.45

■ Ensure that ample time is spent on the alignment of missions and priorities between partnering organizations. Although a seemingly straightforward task, this requires a concerted effort to give a voice to all partners during partnership planning.46 It also requires frequent or consistent revisiting of plans and procedures to ensure that necessary course corrections are made throughout the partnership’s time line.

■ Support linkages between team leaders, program and project managers, external advisors, and other participants across the funders, implementers, and stakeholders in the partnership. Investors or donors often are well positioned to allocate resources to coordinate these linkages, which can help keep otherwise disparate activities aligned.47

■ Provide guidance and insight on the principles of operation, performance metrics, and the desired long-term goals of the partnership—and how these factors can build on or benefit from other programs or initiatives falling outside the scope of the place-based strategy. Funders can draw on analogous experiences and provide access to advisors or other teams who can introduce new information and fresh perspectives in the development of a partnership’s strategy. However, this must be done collaboratively with other partners, and not by directive.48

The Defense Department followed many of these practices in the Afghanistan case. The DoD team prioritized contextually appropriate proposals by investing in months of preliminary research and by supporting hundreds of field visits during program design. The team also set clear expectations for stakeholder engagement; implementation partners were both empowered and required to integrate local perspectives and preferences in program planning and development.

Implementers

The implementers in a partnership (such as contractors, NGOs, or publicly funded aid agencies), should consider the following practices:

■ Identify and recruit world class talent, as needed, to support the development of the partnership strategy and the delivery of programs and operations.49 This is particularly important when there is a need for specialized capacity building, or when partners are operating in difficult or challenging environments. Outside expertise must be brought in with the intent of supplementing existing team experience and stakeholder knowledge rather than supplanting it.

■ Assess available resources and key resource constraints required for the partnership to succeed. Implementers must have an understanding of what place-based capacities will be necessary for an effective collaboration, and whether or not those capacities exist.50 Implementers may need to encourage funders to invest the time and resources required for a proper survey and analysis before full program deployment.

■ Create feedback loops for sharing information about partner expectations, program implementation, and stakeholder satisfaction throughout all stages of the partnership. This function is particularly important for maintaining communication between funders and stakeholders, especially at the individual or community level where resources often are deployed. This is frequently a critical missing link in the development of projects, leading to a mismatch between donor or investor intent and community or stakeholder needs and preferences.51 Without this link, there may be few other means by which to enable effective accountability between the participants in a partnership.

■ Improve on or develop new solutions by identifying outside resources not otherwise available to a community or stakeholder group.52 Implementers may have team members with experience working across wide geographic areas or networks that can be tapped into for innovative ideas. Team members may be able to draw from similar project experiences and responsibly integrate new capabilities or fresh knowledge into the strategy. Implementers also may have access to important political capital relevant to specific program barriers or to the broad scope of the partnership.

In the Afghanistan study, both the Norman Borlaug Institute of International Agriculture and Herat University were key implementation partners. In each case, these implementers oversaw daily project activities and were in constant contact with stakeholder groups throughout the program’s planning and operational phases. Because members of the DoD team moved frequently between initiatives in various provinces, and were back and forth between the United States and Afghanistan, the implementation partners provided essential continuity and consistent feedback. They conducted frequent stakeholder interviews and worked with regional partners, including military programs, to acquire additional funding and equipment to support the projects.

Stakeholders

Stakeholders with a highly vested interest in a partnership’s outcomes (which may include community members, local experts, community-based institutions, neighborhood associations, and others) should consider the following practices:

■ Supply domain knowledge and local expertise for identifying program opportunities with the greatest potential effect in a given geography or for a given population.53 Locally engaged organizations and community members are well positioned to provide input on whether or not approaches and proposed solutions are contextually and culturally appropriate or welcome.

■ Participate and remain fully engaged in the strategic planning and development of as many aspects of program design and implementation as possible.54 Stakeholders and implementers should collaboratively plan meetings at times and locations that allow for broad and inclusive participation, taking into account the conditions and constraints of various stakeholder groups. Some stakeholder groups may need to rely on an independent consensus process and self-select members to represent their interests or participate by proxy.

■ Develop diverse community support and foster ongoing engagement throughout the life cycle of the partnership to provide practical and constructive input to the partners.55 Local leaders or representatives must communicate goals effectively and accurately, collect feedback and suggestions, and integrate community perspectives throughout the deployment of the partnership’s activities.

■ Provide insight on community history and background, social and group identities, and collective beliefs or norms that would otherwise be unknown to outsiders.56 Every community is made up of unique tangible and intangible attributes, nuanced culture, and shared emotional experiences that help define the character and energy of its stakeholders. These fundamental aspects all contribute to a community’s preferences and priorities and cannot be overlooked when developing a place-based strategy.57

Local communities were heavily engaged in all aspects of the Herat initiative in the Afghanistan case. One of the village shuras coordinated farmer participation and crop planning for the center pivot irrigation project. This was a delicate matter requiring some field boundary adjustments and updated cultivation practices. In another instance, the head of one of the food processing centers was heavily involved in the design, sizing, and layout for the center. She corrected some preliminary assumptions around the building’s overall square footage and staffing capacity, and the implementation partners adjusted plans accordingly.58

In the case of the cross-sector partnerships in Afghanistan, funders and implementers made program and infrastructure investments in locally or publicly owned entities—Afghan NGOs, the public university, community cooperatives, and so on. However, in some partnerships, a funder (such as a government entity) may maintain ownership over an investment rather than transfer direct ownership to an implementer or community-based institution. In these cases, partnerships involving public assets should be structured so that stakeholders benefit regardless of ownership or control, such as the arrangement with the Central Park Conservancy profiled in chapter 5. There are many sources of further information on partnership models where the government maintains asset ownership. For example, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe published a relevant typology in its Guidebook on Promoting Good Governance in Public-Private Partnerships.59 Regardless of the model used, successful and collaborative place-based partnerships should exhibit and follow a well-established set of operational standards and responsibilities.

Cooperatively Designing an Analysis Framework

When collaborative principles and mutual responsibilities are established, partners will be better equipped to design the partnership’s program analysis framework. Numerous tools exist on which to base the design of the framework.60 Given the complexity of decision making in cross-sector partnerships, tools drawing on multiattribute utility theory may be most applicable.61 For example, a Pugh matrix analysis62 may be well suited when partners engage in multiple criteria decision making.63 Regardless of a framework’s specific attributes, the analysis helps illustrate the alignment of participants’ respective priorities and preferences with the partnership’s strategy and intended outcomes. In effective place-based strategies, these frameworks are developed cooperatively across all partners, and partners work together to use the information to analyze program options and guide decision making.64

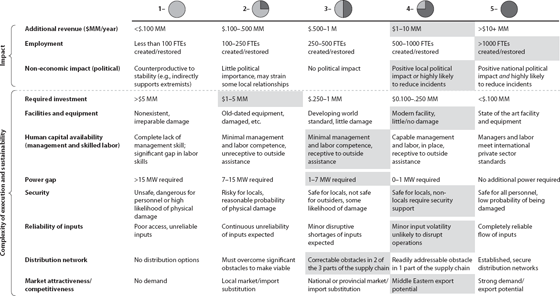

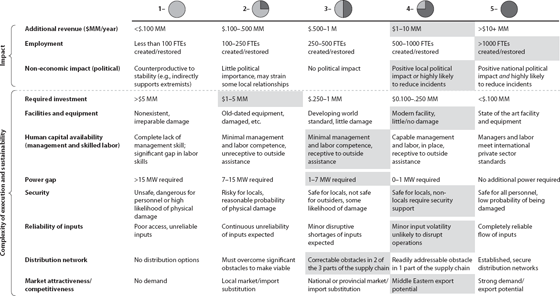

In the case of Afghanistan, the DoD, the Borlaug Institute, and Herat University collaboratively developed an evaluation tool that was used to analyze proposed programming early in the partnership. This tool included evaluation categories such as “expected impact” and “complexity of program implementation.” Each category included project-specific measures such as “employment generated,” “safety and security” in a given project’s location, and “speed or time required” for project completion. Measures for each criterion were divided into a range from one (the lowest score) to five (the highest score), and all projects were evaluated using this standardized scoring. Figure 8.3 is an excerpt from a project evaluation in Herat.

Figure 8.3 A simple weighted project evaluation excerpt conducted by partners operating in the Herat region in the Afghanistan case. Measures for specific project attributes (the rows) and assigned scores (the columns) are indicated by the shaded boxes. In this example, the evaluated project is expected to generate $1–10 MM of additional revenue, therefore scoring four points in that category.

Evaluation tools can be highly flexible and as multifaceted as required based on the complexity of a partnership and the preferences of funders, implementers, or stakeholders. Although the structure of the initial Defense Department tool was fairly straightforward, portions of it were similar to a more complex model described in the next section.

The Impact Balance Sheet

We assume that partnering organizations have established a collaborative logic flow model and have surveyed various value chains relevant to the partnership’s goals. Partners have leaders with diverse skills and experiences in place and have a plan for maintaining team momentum throughout the life cycle of the partnership. We also assume that partners understand each other’s strengths, constraints, priorities, and respective time lines, as discussed previously.

Partners also need to formalize how they analyze program options for the partnership and what aspects of analysis will be most helpful and relevant to collaborative decision making. The Impact Balance Sheet forms the basis for the place-based program analysis framework outlined here, and derives from an analytical tool codeveloped with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.65 Furthermore, it is an integrated component of the Impact Rate of Return (iRR) formula presented in chapter 12—specifically, it contributes to iRR’s Impact Multiplier variable.

Effective frameworks for place-based partnerships provide funders, implementers, and stakeholders with a model consisting of the following attributes:66

■ A set of evaluation criteria reflective of each partner’s preferences and priorities regarding options for program implementation. These criteria should be context relevant within the place-based strategy and are used to score or rank program alternatives within the partnership. In the Herat assessment tool, one criterion was the amount of time required for project completion.

■ An assessment platform that allows for customized weighting between different criteria—depending on the importance of those criteria to the partners—and yet provides a consistent scoring structure across partners’ frameworks and between program analyses. One partner may view the safety and security in a given project location as a more important criterion than the project’s expected time to completion. In such a case, that partner would assign a higher numerical weight to its preferred criterion (safety).

■ An ability to adjust weighted criteria scores based on the confidence the partners have in assigning scores. There may be varying levels of uncertainty across criteria and between projects, and this acts as a discounting factor. For example, if partners have a high level of uncertainty about the amount of time required to complete a project, they may discount that score by a relatively high amount.

■ An analytical output that is meaningful, comparable between program alternatives, easy to communicate, and can be plotted in different ways (for example, the time required for project completion relative to a project location’s safety, or the size of the population reached relative to the expected economic impact).

Analysis frameworks vary from partnership to partnership, and the specifics of a given place-based strategy will influence which evaluation criteria are used to score the different program options. Although individual criteria may differ between frameworks, we suggest that the criteria categories generally include the following groups:67

1. Program Alignment. This aspect of the framework evaluates the extent to which a given project or program aligns with high-level goals or parameters established by the partners’ leadership teams. When developing cross-sector partnerships, there may be many options for allocating resources. Taking into account that a full assessment of all options against all criteria could take considerable effort, cost, and time, this section acts as a stage gate for the overall process. If a project or program alternative does not achieve a minimum alignment score, as mutually determined by the partners, it will not be considered further within the analysis.

This category may include line items related to the size of funding for a project (relative to the overall partnership’s budget), the type of program activity (for example, product or service delivery, knowledge development, or policy change), how well the project fits partners’ missions, the degree of alignment with community-led plans, and so on.

2. Program Objectives. This aspect of the framework evaluates how well a given project or program aligns with the partnership’s defined objectives. The program objective score may include line items such as the size of population reached, depth and longevity of impact, sustainability of a project, or cost efficiency of a program. Other factors that may be considered include the uniqueness of the opportunity for the given partnership and the time horizon within which the given program or project can be implemented.

This category helps determine what aspects of program impact are most important to the partners, and how effective a given opportunity may be at delivering such impact. This category often includes criteria representing the operational factors making up the x and y axes of the scoping chart (see figure 8.1).

3. Program Risk. The final aspect of the evaluation framework looks at types of risk related to program options, such as the risk that a set of activities will not result in the intended outcomes or that a program will lead to unintended consequences that cause harm or disrupt the partnership’s time line. It also questions whether the partners can properly implement the project being evaluated.

This category may include criteria that account for risk to the partnership or partners’ reputation, risk based on a project’s overall complexity, or whether or not there is a risk that significant amounts of unexpected or unavailable follow-on funding could be required.

These categories help partners define the overall areas they will evaluate, and line items in each category address how the partners will evaluate specific programs. Partners also determine how they will score the valuations across the categories and criteria and how they will assign weighting depending on outcome preferences. This will answer what specific metrics the analysis framework will use to measure opportunities against each other and how important each metric will be.

As an example, one of the program objective categories may be allocated 200 points. A line item within that category, say, the predicted breadth of impact of a given project, may be weighted with 25 percent of the overall points in that category relative to the other line items. This would yield a possible 50 points for that line item.

Criteria within the line item help define what partners mean by breadth of impact. This can be customized depending on program specifics, but may include the number of people reached directly and indirectly by a project, as well as the likelihood a project can build off of other projects already taking place in the program area. Each of these criteria are subweighted within the possible 50 points for that line item. The criterion people reached directly may receive 50 percent of the 50 possible points allocated, or 25 possible points.

Performance ranges define the evaluation ratings for each of the criteria, and these ratings determine what percentage of possible points the project actually receives. Continuing with this example, if a project is predicted to reach more than 10,000 stakeholders, it may receive a rating of 3. If it will reach between 1,000 and 10,000 stakeholders, it may receive a rating of 2, and so on.

In our example, a rating of 2 is only 75 percent as good as a rating of 3, so if that criterion is rated a 2, it receives 75 percent of 25 points, or roughly 19 points. Figure 8.4 shows a few line items from a simplified version of the Impact Balance Sheet analysis framework and illustrates this calculation across category line 2.1, criterion 2.1.a.

Figure 8.4 The Impact Balance Sheet tool allows partners to develop complex evaluation models for program selection. In this example excerpt, line 2.1.a illustrates how a given partner may assign weights and scoring to a specific criterion regarding the number of people directly reached by a program under consideration.

The evaluation rating portion of the model helps partners describe, in a quantifiable way, how they differentiate scales or qualities of impact across their line items—something central to the Impact Rate of Return formula (see chapter 12). This example uses a simplistic three-step rating scale, in which an evaluation rating of 3 equates to “high quality impact,” a 2 equates to “medium quality impact,” and a 1 equates to “low quality impact.” Fully customizing a model of this type provides partners with a means to define their joint priorities and to collaboratively determine what metrics and ranges should be used to evaluate many possible projects in a consistent manner.

In more complex evaluation models, each of the scores can be adjusted based on the partner’s perceived level of confidence in assigning a given valuation (for example, the partner’s level of confidence that a given project will reach the claimed scale of population, or succeed in time). A discounting factor can be applied based on levels of uncertainty, which is particularly helpful when projects use untested methods or partners operate in locations with instability, unreliable infrastructure, or other constraints.

These categories combine to provide an overall project evaluation score, discounted appropriately based on the confidence ratings. The results can be plotted on a scoping chart to illustrate how the methodologies work together visually. This is a useful tool showing an easily understandable relationship between projects and user-selected variables (such as program cost and implementation risk). For example, figure 8.5 plots scoring criteria representing a subset of consolidated projects from the Afghanistan study.

Figure 8.5 Plotting program evaluation scores on the previously outlined scoping chart provides a visually useful output illustrating the relationship between projects and partner selected variables. This example includes operational variables such as the scale of program cost and program implementation risk.

Co-creating a comprehensive strategy between organizations from different sectors must account for their different strengths, motivations, time lines, and cultures. This is a challenge, particularly when it is time for organizations to prioritize their activities. Partnerships often offer a positive-sum result, yielding successes far greater than any one organization could achieve alone.68 But it is not unusual for partners to fall into a negative-sum mind-set and worry about how and where to allocate finite resources. This is ironic because it is often the case in resource constrained environments that “cooperation is not merely a luxury but a necessity to address complex societal problems.”69

Developing an effective place-based strategy requires funders to involve other partners in making decisions about budgets and goals. They must be willing to consider new, and perhaps less exciting, ways of allocating funding over longer time horizons or in ways that support transitions between short-, medium-, and long-term programs. It is likely that funders will need to consider making up-front investments in preliminary work that supports the development of local and regional capacities.

In general, funders and implementers must be willing to do something that has been traditionally difficult for them: engage stakeholders at the community level, involve them in project development and decision making, and provide them with the opportunity to shift the course of programs during the life cycle of a partnership.70 Furthermore, implementers must constantly ask themselves how they can do a better job facilitating open communication between funders and stakeholders and how they can provide feedback loops between the two.

Challenges at a local level also may impede a successful place-based partnership strategy:

Stakeholder Rejection. A community or group of stakeholders may not wish to engage in partnership building if that group has developed mistrust in outside partners, or if there is a track record of failure. This could be because a funder or implementer did not develop plans inclusively or follow a set of cooperative principles in the past.71

Challenging Conditions. Certain locations may lack a degree of governance, rule of law, or enforcement mechanisms (for contracts, for example) that are necessary for effective engagements between funders, implementers, and local communities or community-based intuitions.72 This can be particularly difficult for organizations without experience operating in such environments.

Foundational Needs. The absence of basic services (such as quality health care or education) or enabling infrastructure (such as roads or Internet access) can be prohibitive for successful partnerships.73 This is especially true if funders are unable or unwilling to take on the responsibility of making up-front investments to address these needs or to invest in local capacity building.

Partner Mismatch. A funder’s intentions and a community’s needs may be incompatible, or a funder or implementer may misunderstand stakeholder preferences. Staff of an implementation partner may believe their experiences working in one environment will translate well to another—and be mistaken. Implementers may find that they are unable to deliver on a project, leading to unfulfilled commitments or partnership stagnation. Any of these may result from a lack of early and inclusive planning, quality discussion, or the alignment of partner preferences and priorities.74

These are just a few of the potential difficulties. Other possible obstacles include coordination complexity, the prevalence or persistence of corruption, unanticipated resource constraints, and more. We will illustrate some of these challenges in the case outlining partnerships delivered for the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (see chapter 13).

CONCLUSION

The recommendations outlined in this chapter may not be universally applicable or practicable. Every partnership is unique, constantly changing, and dependent on each partner’s willingness to work collaboratively through conditions both positive and challenging. It is critically important for funders and implementers to engage stakeholders thoroughly in partnership planning and development.

As we saw in the case of Afghanistan, a strong connection between funders, implementers, and stakeholders was a vital component of the initiative. In any partnership, success relies on the delicate relationship between all groups involved, as well as their commitment to work together over time regardless of the difficulties that present themselves. Open, honest, and frequent communication is important, as is the partnership’s emphasis on building community and the partnering team’s familiarity and camaraderie with its participants.

The set of operational responsibilities and cooperative principles described in this chapter can guide these engagements, helping to conceptualize and encourage a long-term sense of place and inclusion in support of a partnership strategy. By incorporating these principles, we expect that partners will be more willing to act in the interests of all who are involved, and funders and implementers will treat stakeholders as they would want to be treated themselves, working collaboratively through setbacks and sharing in the partnership’s success.