WILLIAM B. EIMICKE

We began this book with the story of Central Park and the High Line because they so dramatically and visually demonstrate how cross-sector partnerships can achieve amazing results simply not possible under a more traditional single sector, hierarchical, organizational structure. These stories demonstrate the power of partnerships led by people with collaborative leadership skills. Were it not for a handful of committed, experienced, and focused leaders, Central Park and the High Line might still be dangerous eyesores, as they both were not so long ago. In each case, a nonprofit organization formed to rescue or create these iconic parks. In partnership with New York City government and businesses and community organizations, the Central Park Conservancy (CPC) and Friends of the High Line operate and maintain these public spaces primarily with their own funds and free of admission charges to visitors. As important, and mirroring many elements of the social value investing framework, these two partnerships have led to a new way to create, rehabilitate, and operate public parks that can be replicated in cities across the United States and around the world.

In chapter 3, we saw effective partnership processes operating through Digital India and Apollo Telemedicine. These partnerships succeeded under the strong, collaborative leadership of the Modi administration in partnership with India’s major technology companies, the global Apollo health care organizations, and local entrepreneurs. In this chapter, we look at how Gordon Davis of the New York City Parks Department and Betsy Rogers of the fledgling Central Park Conservancy built a partnership, slowly and methodically over time, through motivational leadership and a relentless commitment to a shared vision. Later, under the collaborative leadership of Doug Blonsky, the Central Park Conservancy implemented an innovative Zone Management System and more effective ways to manage turf, care for trees and plants, remove trash, and reuse biowaste. Applying many aspects of the social value investing framework—a formal partnership structure, mutual operations, and a comprehensive strategy—the decentralized zone park maintenance system is operated by forty-nine diverse teams across Central Park, each with the necessary experience, skills, and autonomy. In addition, CPC created a subsidiary education and training institute to help its partner, the New York City Parks Department, successfully apply these innovative techniques in dozens of parks run directly by city employees.

Comparable to CPC is the success of the High Line, which is largely attributable to another decentralized team approach implemented by an equally extraordinary, collaborative, but somewhat different style of leadership. Joshua David and Robert Hammond came from the community and formed the nonprofit Friends of the High Line to preserve and reuse what they perceived as a potential community asset. David and Hammond also sought the broadest possible public participation and acted as community advocates throughout the partnership (in line with the place element of social value investing, which is discussed in chapters 7 and 8). They also recruited John Alschuler, a nationally recognized real estate expert and consultant, to help define and quantify measurable indictors of success. Using the CPC as a model, they developed a portfolio of funding, securing risk capital from a number of high-profile philanthropists and working closely with influential and powerful members of New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s team, including Amanda Burden, chair of the City Planning Commission, first deputy mayor Patricia E. Harris, deputy mayor of economic development Dan Doctoroff, and parks commissioner Adrian Benepe. The city leaders brought the power of zoning, substantial capital dollars, political expertise, and parks knowledge. The Friends of the High Line brought the vision, the community support, philanthropic dollars, and the willingness to sustain the project over the long haul.

Both the Central Park restoration and creation of the High Line were made possible by effective cross-sector partnerships led by collaborative leaders who were in touch with their team’s needs and motivations. These leaders clearly and mutually established measurable indicators (by freely sharing data and information between organizations) and defined success around their shared goals. It is important to recognize that in both cases these organizations do much more than raise a great deal of money for the maintenance and operations of the parks. They run the parks with their own staff and equipment, using innovative management techniques developed with their partners, and they have subsequently helped the City Parks Department apply these techniques widely.

THE QUINTESSENTIAL NINETEENTH-CENTURY PARK

Most people flying into New York City over Manhattan are amazed by the size of the green space in the heart of the most densely populated city in the United States, a city often referred to as the City of Skyscrapers. Central Park is huge for an urban park: 843 acres, 2.5 miles long, and half a mile wide. It stretches from 59th Street—bookended by Columbus Circle on one side and the Plaza Hotel on Fifth Avenue on the other—all the way up to 110th Street in Morningside Heights, just south of Columbia University and Harlem. It is open every day of the year from 6:00 AM to 1:00 AM.1

Central Park was designed in 1858 by Frederick Law Olmsted, its superintendent of construction, and English architect Calvert Vaux. The site was set aside for a public park by the government, and Olmsted and Vaux were chosen to design it through an open competition. Built out to its current dimensions in 1873, the original land area is largely intact to this day.2 In addition to the trees and open green spaces, the architects designed footpaths, bridle paths for horses, and carriage paths, along with four sunken transverse roads, enabling cars to pass through the park without disruption. Most of the park is relatively free of cars and buses to this day.3

The uses of the park have changed somewhat over the past 150 years to reflect “the most important values held by the society of the day.”4 Built as a quintessential nineteenth-century park for peaceful thought and joyful celebration of nature, in the twentieth century the park dramatically expanded recreational opportunities, including more than twenty playgrounds for children, skating rinks, a swimming pool, tennis courts, and ball fields. Today the park is an important component of urban infrastructure. It serves as a major tourist attraction, a place for cycling and jogging, and as the backyard and “view” for some of the world’s most valuable residential properties. These views help generate hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes for the city government, as well as tax revenue from visitors coming from all over the world.

CYCLE OF DECLINE AND RESTORATION

Great vision and tremendous effort made Central Park possible. Maintaining and protecting it from politics, opportunism, progress, and underfunding over its entire history has proven equally difficult. Olmsted applied for the position of superintendent of Central Park in 1857 and was hired by a park board appointed by a Democratic administration and run by a corrupt political machine widely known as Tammany Hall.5 Nominally a Republican, Olmsted was highly qualified for the job, and the board viewed the appointment as an opportunity to satisfy Republican demands for a share of the patronage controlled by Tammany Hall.6 It was Olmstead’s visionary and inspirational leadership, professional expertise, and ability to navigate the politics of the board and the city government that enabled him to keep the park in good condition for as long as he did.

Olmsted sought to manage the park professionally, but he was constantly caught in the crosscurrents of New York City and New York State politics. Between 1870 and 1883 he was forced out, reinstated, resigned, came back in a lower position, was let go, and was retained as a consultant. Finally, in 1883, he relocated to Boston and worked on building their park system.7 The permanent departure of Olmsted and the death of Calvert Vaux in 1895 marked the beginning of a slow but steady decline in the condition of Central Park.8

Under the control of Tammany Hall, the city parks became “fiefs for private gain.”9 As a result, the parks, including Central Park, became “scabs on the face of the city.”10 Between 1900 and 1934, the park’s great lawns turned to weeds, then to dirt and mud holes when it rained. The paths and walkways were littered and broken. Buildings, fountains, statues, and walls were filled with graffiti, vandalized, and, in many cases, literally were falling down. The city park workers “complemented the scenery” with their appearance.11 The condition of the park worsened with the onset of the Great Depression when homeless men constructed and lived in more than two hundred shacks behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art.12

The depression era also marked the beginning of the restoration of Central Park, with significant assistance from New York State and the federal government. In 1933, Fiorello H. La Guardia, a reformer and liberal Republican running on the Fusion ticket, was elected in a three-way race with only 40 percent of the vote. According to historian Robert A. Caro, it was the last minute but passionate endorsement by the widely-known and influential Robert Moses that put La Guardia over the top. In return, La Guardia supported state legislation drafted by Moses that consolidated the city’s five borough parks departments into a citywide department and enabled Moses to simultaneously hold the positions of state and city parks commissioner as well as several other commissions and authorities concerned with parks and roads.13 Moses pulled together important financial support to accomplish the parks restorations and engaged numerous federal, state, and local agencies to get the necessary work done. He was a strong leader but hardly a collaborative one, as his many very public battles and reputation attest.

On January 19, 1934, Moses became New York City Parks Commissioner, and he began what would be twenty-six years of restoration and innovation for Central Park. Between 1934 and 1938, he used federal Civil Works Administration (CWA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA) dollars to fund architects, engineers, and thousands of laborers working in three shifts, 24/7, through even the most severe winter weather, to bring Central Park back to its former beauty.14 He planted trees, flowers, and bushes; fixed roads and bridges; restored paths and modernized playgrounds, ball fields, and the landscape of the “Great Lawn”—he even reinvented the Central Park Zoo. Moses was often hailed in the press for these achievements—“dynamic,” “brilliant,” “Moses’ New Deal for Parks,” “Moses made an urban desert bloom”—and by the general public as well.15

Moses is sometimes criticized for changing the original look of the park, replacing many of the original materials with red brick. Some of his new structures blocked important views designed by Olmsted and Vaux.16 On the positive side, Moses restored Central Park and ushered in an era of professional management and maintenance. He also initiated a wide range of free entertainment and programs for children and their families, including a Winter Carnival, dance competitions, puppet shows, an entire children’s district (including a musical clock, the zoo, sculptures, the boat house, and concessions), and the very popular Shakespeare in the Park produced by Joseph Papp.17 Ironically, it was a very public battle with Papp over the future of Shakespeare in the Park that contributed to the end of the Moses era in Central Park.18

Moses resigned as City Parks Commissioner on May 23, 1960, to accept the presidency of the 1964–65 World’s Fair in Queens, New York.19 Many of Moses’s hires remained in the Parks Department, and Moses himself continued to exercise some behind the scenes influence, but his departure marked the beginning of nearly two decades of severe decline in infrastructure, cleanliness, and safety in the park.

The social movements and upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s often used the park as a site for gathering and demonstration. Lax management permitted heavy use of high-impact sports, with and without permits. Lawns were turned to dust and mud, and clogged catch basins resulted in frequent flooding of open spaces, paths, and walkways.20 The simultaneous decline of New York City’s fiscal health was unfolding—the city nearly went bankrupt in 1975, and local tabloid headlines announced that then President Ford told New York it could drop dead.21 The loss of the city’s manufacturing industry to the lower-cost southern states and the massive exodus of the city’s middle class (over highways and bridges built by Robert Moses’s public authorities), combined with a national recession, put the city budget in severe imbalance. Banks cut off the city’s credit and, ultimately, a financial control board and state assistance were put in place. The price for the city was severe, and budget cuts resulted in the loss of 6,000 police officers, 6,000 teachers, and 2,500 firefighters.22

The consequences for parks in general and Central Park in particular also were severe. The City Board of Estimate had approved a $7 million Central Park rehabilitation fund, but newly elected Mayor Abraham D. Beame chose to use that fund for other parks around the city. Shortly thereafter, in 1975, the fiscal crisis put all parks restoration projects on hold.23 For Central Park, this led to vandalism, graffiti, piling up of garbage, and deferred maintenance.24

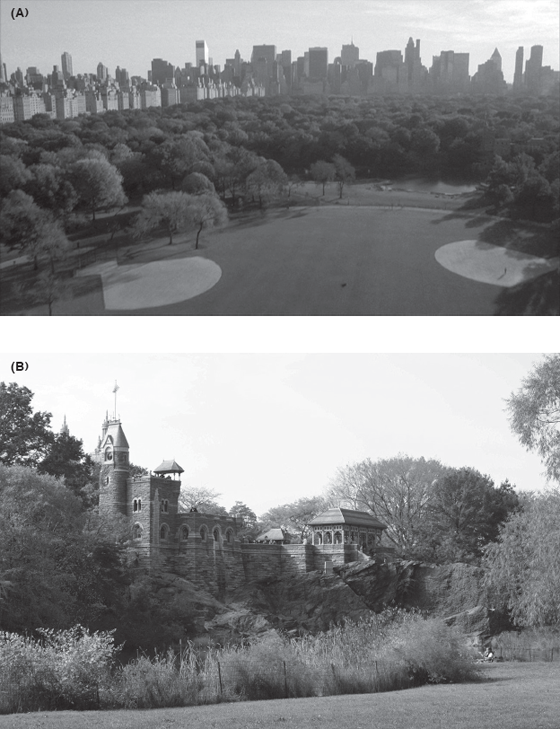

Broken benches, playground equipment, and lights that were never fixed created an environment that invited crime, as is often described in the broken windows theory of policing.25 As recent Central Park Administrator and Central Park Conservancy President and CEO Doug Blonsky described the situation, “the bridle path had more rats than people, the Great Lawn had become the Great Dustbowl, Turtle Pond was filled with the stink of dead fish, and the Castle was covered in graffiti, surrounded by razor wire, and inaccessible to the public.”26 Central Park became so dilapidated (figure 5.1) that major feature films including Annie Hall and Six Degrees of Separation used it as a symbol of New York City’s physical decline and dangerously high crime rate.

Figure 5.1 (a): Belvedere Castle with graffiti before its renovation in 1984; (b) the dilapidated Great Lawn. These images illustrate conditions in the park before the partnership between the New York City Parks Department and the Central Park Conservancy. Photos by Sara Cedar Miller, courtesy of CPC.

Despite the city’s ever-worsening fiscal condition, the New York City Parks Department workforce swelled to more than three hundred on the government payroll assigned to Central Park. Without a leader with the strength, dedication, and command of Olmsted, Moses, or Blonsky, and without performance measures to hold those workers accountable, the parks continued to decline.27 Perhaps the low point in the history of Central Park was the beating and rape of Trisha Meili—known as the Central Park Jogger case—which filled the world’s tabloid headlines in the spring of 1989.28

For many outsiders, Central Park is a very visible symbol and a barometer of the state of the city, and in the 1980s and early 1990s New York City was a very dangerous place. In 1990, 2,245 people were killed in New York City, an all-time record and up 17.8 percent from 1989. Then police commissioner Lee Brown blamed the absolutely frightening totals on drugs and guns.29 To put this in perspective, 2015 was a year in which murders spiked nationwide: New York City had 352 murders, and Chicago, with a third of the population of New York City, led U.S. cities with 488 murders. Today the media often represents Chicago as a very dangerous city, which gives you a sense of how really unsafe it was in New York City in 1990.30

These tragedies created fear across the city and around the nation. Central Park is located in the heart of Manhattan, easily accessible to residents, commuters, and tourists alike.31 Because of its beautiful, pastoral setting in midtown Manhattan, some of the most expensive and exclusive high-rise residences, hotels, and office buildings surround its perimeter. This location and its influential neighbors made the sad and dangerous state of Central Park in the 1970s and 1980s a very visible, much discussed, and very troubling state of affairs.

The wealthy occupants and owners of the buildings surrounding the park view Central Park as their backyard—and its condition has a material impact on their quality of life and the value of their substantial real estate investments. The danger and violence in Central Park was danger and violence in their backyard, the backyard of the “rich and famous.” To combat the decline, several voluntary organizations and friends of the park groups formed to try to restore the park to its former glory.32

PARTNERING TO BRING THE PARK BACK

One such group, the Central Park Community Fund, led by two wealthy financiers, George Soros and Richard Gilder, commissioned a study of the park’s management in 1974. Published in 1976, it became known as the Savas Report, after its author, then Columbia Business School professor E. S. Savas (who subsequently became well-known as one of the intellectual forces behind the privatization movement).33 The report made three major recommendations: first, create a Chief Executive Officer for Central Park (and the city’s other flagship parks) with full responsibility for parks operation (which emphasized collaborative leadership); second, establish a Central Park Board of Guardians responsible for developing a strategic plan (or comprehensive strategy) for the park and for ensuring its implementation; and, third, promote civic engagement (and community ownership) through the planning process, including private fund-raising to realize the strategic plan.34

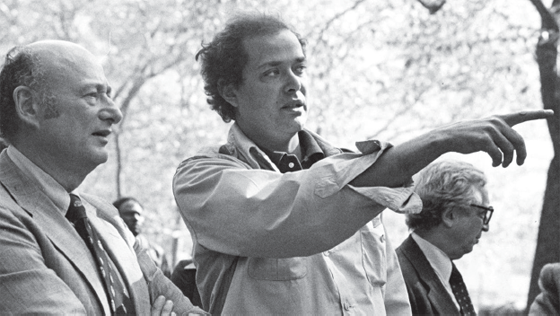

In 1978, newly elected New York City mayor Edward I. Koch was rightly focused on restoring the city’s fiscal health: balancing the budget and establishing a sustainable, long-term fiscal plan while keeping the city livable and thereby growing its economy. His mantra to the agency commissioners he appointed was the same, repeated ad nauseam: “Do more with less!”35 To head the Department of Parks and Recreation, Koch chose Gordon Davis (figure 5.2), a Harvard-educated attorney with prior New York City government experience under former mayor John Lindsay.

Figure 5.2 New York City Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis (appointed in 1978) recruited Central Park’s first Administrator, Betsy (Barlow) Rogers. The two led the park’s revitalization by establishing the Central Park Conservancy partnership. Photo courtesy of CPC.

Gordon’s response to Koch’s “Doing more with less” was, “Give me a break!”36 What Commissioner Davis meant was that funding for parks had already been cut dramatically. The Parks Department staff was down from 8,000 during the Moses years to 2,500 in 1978, so there would be few savings and much potential danger in further cuts. Davis instead developed a multidimensional strategy founded on decentralization, collaboration, and partnerships, very much in line with our social value investing model.37

Internally, Davis advanced a decentralized team approach for managing the city’s parks by creating the new position of Borough Parks Commissioner, who acted as a chief executive for all of the parks in each of the city’s five boroughs (otherwise known as counties). He also appointed an administrator for each large park, which proved to be critical to the future of Central Park. To deal with the staffing crisis, Davis leveraged complementary federal Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) funds to create new parks jobs that were paid entirely by CETA for the first eighteen months for positions qualifying for federal job training funds under the act.

He also worked with the mayor’s office to obtain authorization for a new job classification, Urban Park Ranger, which was outside the department’s existing civil service titles and enabled Davis to bring in young, well-educated, dedicated individuals with management skills and a customer service attitude. New uniforms and young, friendly professionals as a visible presence in parks, particularly in Central Park, helped project the reality that things were getting better.38 One of those rangers, Adrian Benepe, later became the Commissioner of Parks and Recreation under Mayor Michael Bloomberg. This parallel structure to the traditional Parks Department organization and staffing would continue to expand as the management of Central Park shifted from direct city operation to the cross-sector partnership that runs it today.

BETSY ROGERS AND THE CONSERVANCY

Perhaps the important innovation of Commissioner Davis was his decision to hire Elizabeth “Betsy” (then Barlow) Rogers—a young Yale educated urban planner, writer, and Olmsted expert—as the first Central Park Administrator in 1979. Prior to her appointment, she was the director of the Central Park Task Force’s program for summer youth interns, which worked closely with the Parks Department.

As administrator, Rogers was directly responsible for all aspects of the daily operations, exactly what the Savas Report recommended. Upon taking the job, Rogers asked some logical questions: Where is my office? What’s the budget? And what are my responsibilities? Davis told her that he didn’t know if there was an office, there was no budget, and they would figure out her responsibilities as they went along.39

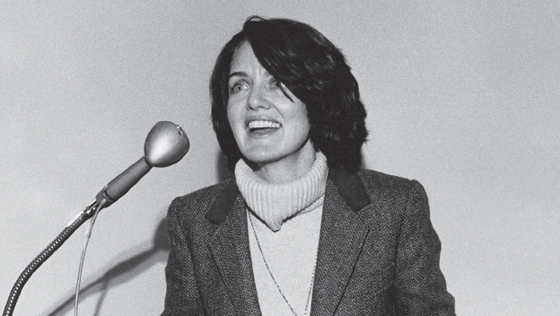

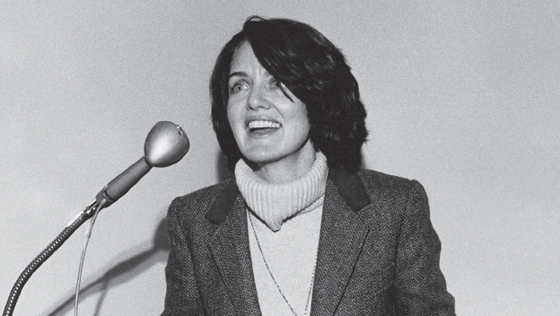

A self-described “zealous nut” about the importance of Central Park to the future of New York City, Rogers (figure 5.3) loved the mission of restoring the park to its former greatness.40 It was Rogers (with full support from Commissioner Davis) who developed the vision of a cross-sector partnership to restore and maintain Central Park primarily with private dollars. She acquired and used a small gift from the Vincent Astor Foundation to hire a horticulturist, summer interns with some horticulture training, and an environmentalist, and she completed several small but visible restorations to show the public and potential donors that Central Park was on the way back.41 From the very beginning, Rogers used a collaborative leadership approach as she brought together the city administration, the Parks Department, outside funders, community leaders, and volunteers with a passion to help restore Central Park.

Figure 5.3 Betsy (Barlow) Rogers, the first Central Park Administrator and first President and CEO of the Central Park Conservancy (positions she held simultaneously). Photo courtesy of CPC.

A year later, Rogers became president of the newly created Central Park Conservancy, merging two existing and important advocacy groups: the Central Park Task Force and the Central Park Community Fund (an organization similar to what the Savas Report recommended). Rogers masterfully leveraged private donations to add to city tax dollars to help the government run the park; she continued on as Central Park Administrator while simultaneously serving as president of CPC. Some advocates suggested she couldn’t criticize the city when necessary and appropriate if she also sat on their side of the table. Her response, “I don’t want to be critical. I want to work with the city.”42 In that spirit, Mayor Ed Koch assured the Conservancy that he would not reduce the city’s financial commitment to Central Park as more private dollars were raised and contributed to the Park from CPC. By sharing success in this way, the CPC built credibility with donors, knowing that their gifts would accelerate the park’s restoration, not just provide general budget relief to the still-stressed New York City finances.

Initially, the city government provided virtually all of Central Park’s operating funds, and the Conservancy—which had fewer than thirty employees as late as 1985—focused on funding the design and preparation of major shovel-ready capital projects such as the restoration and renovation of the Sheep’s Meadow, the Dairy, the Cherry Hill foundations, and Belvedere Castle.43 The team knew they needed a big, visible success early on to show there was reason to believe the park could be rescued, and Davis wanted Sheep’s Meadow to be that symbol. This project, however, cost well beyond an amount they could dream of raising at the time. It just so happened that New York City governor Hugh Carey was also looking for a highly visible project to signal hope for the city’s future. To Davis’s surprise, Carey also settled on Sheep’s Meadow and secured state funds for the restoration.44

Commissioner Davis and Administrator Rogers recognized from the beginning that they were forming a cross-sector partnership that could transform Central Park for decades to come. They also recognized that there were great risks: conflicts between the two workforces, significant differences over priorities and policies, and real and perceived issues regarding private entities having any kind of control over public spaces, particularly such an important public space as Central Park. Partnerships, even more traditional PPPs, were somewhat uncommon in the United States at the time and virtually unheard of for the operation of large public parks, so Davis and Rogers kept the relationship as informal as possible, “No lease…no license agreement.”45 Although they consistently acted as collaborative leaders with complementary yet diverse teams, they delayed formalizing the partnership until they had achieved sufficiently broad public participation and support.

Rogers also trod lightly on issues regarding location of the two groups of workers, differences in training, and equipment. She found many of the civil service workers poorly trained and unmotivated, and there was resentment. As Rogers recalled, initially the Conservancy workers were not welcome in the City Parks building and were forced to use a small pesticide shed as their “headquarters.”46 Rogers preferred to hire new workers through the CPC, without civil service red tape and negotiations with citywide public employee unions. Nevertheless, she worked hard to maintain integrity and respect; and over time, the two workforces came together.

CPC AND BLONSKY TAKE THE LEAD

Doug Blonsky, a landscape architect, joined the Conservancy’s Capital Projects office in 1985. His technical expertise and passion for being hands-on in the field, along with his coordinating skills, propelled him up the organization’s management ladder—from supervising construction projects to chief of operations, then to Betsy Roger’s title of Central Park Administrator. His intimate knowledge of park management and maintenance provided him with critical leadership skills for success. Since 2004, he also has held the title of president of the Conservancy and CEO, responsible not only for the park’s management and operations but also for fund-raising.

Like Rogers, Blonsky supervised both Conservancy and City Parks Department staff. It is a real challenge to create diverse teams of workers from two very different cultures and to establish a unified set of standard operating procedures, job descriptions, and roles and responsibilities. By listening, learning, and then leading, Blonsky established a common culture of professionalism and innovation that characterizes the CPC-Parks Department combined staff to this day.

Blonsky implemented a comprehensive management strategy (an important partnership process) at CPC called Zone Management, which divides the park into forty-nine geographic zones for managerial purposes. Each zone is headed by a zone gardener, who supervises grounds technicians and volunteers. Each is held accountable for his or her area, according to maintenance standards set out in a management and restoration plan. Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Conservancy used strategic planning and measurable performance indicators and accountability to define success. They also used ongoing fund-raising to eventually create a formal partnership with the City Parks Department. As Blonsky commented,

We were very good at having projects truly shovel-ready and prepared. We would do the designs, have the plans complete, and then at the end of the fiscal year, City Hall would go to the Parks Department and say, “We have this pot of money, do you have any projects ready to go?” We did, and it became a really great way for us to get City money invested into the park, leveraged by the private dollars we used for the designs and plans.47

In 1987, the Conservancy launched its first capital campaign, which raised $50 million. Although significant improvements in the park had been achieved throughout the 1980s, an economic slowdown in the city economy led to major cuts in Parks Department staff and maintenance. There were delays in capital projects, and it became more difficult to raise private donations. In 1990, Rogers said, “These are the hardest times we’ve seen in 10 years. The Great Lawn is a dust bowl [again] and the pond is almost completely silted up.”48

In response, Richard Gilder created a challenge grant in 1993 to support the Conservancy and the city in their second “The Wonder of New York Campaign.” That campaign reached its goal of $51 million—$17 million from Gilder, $17 million from the city, and $17 million raised by CPC from other donors. From this point forward, the Conservancy would provide at least two-thirds of the capital budget for the park and an ever-larger share of the operating budget and staff.49

Although crime in the city continued to rise until 1990, the work of the Conservancy in beginning to reclaim and rebuild Central Park provided a very visible symbol of hope for the city overall. Then mayor David Dinkins secured state funding to significantly increase the number of NYPD police on patrol through his “Safe Streets, Safe City” initiative. In 1994, NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton’s CompStat innovation (see chapter 11) started to significantly reduce crime and restore the quality of life in what would become the safest big city in the Americas. In many respects, CPC’s work in Central Park and the NYPD’s work on the city streets were mutually reinforcing efforts to make New York City livable again.

The collaboration between CPC and New York City became a formal, structured partnership in a contract signed in 1998. Under the eight-year agreement, the Conservancy, led by Central Park Administrator Doug Blonsky and CPC Chair Ira Millstein, reported to the Parks Department Commissioner Henry Stern under then mayor Rudolph Giuliani. The city would contribute up to $4 million annually (it averaged $3.7 million over the term of the contract), up from about $3 million under the informal relationship. In return, the CPC would take full responsibility for operation and maintenance of the park, including operating expenses in excess of the city’s contribution, and nearly all capital costs would come from CPC fund-raising.50 Blonsky was okay with the deal because he really thought of the park’s budget as one big pot. CPC did not own the assets. For him, creating and maintaining a great park was a combination of capital restoration and maintenance, cutting the grass, pruning the trees and bushes, a lot of picking up of garbage, security, and customer service. To Blonsky it was one big job with one big budget.

Even back then, some were concerned that CPC’s reliance on (and success at) fund-raising would drain public and private resources from the rest of the parks in the system. Those concerns persist today, but the true sharing of success and the smooth operation of the partnership continues to attract much more praise and support than criticism. From the city side, as NYC Parks Deputy Commissioner Robert Garafola said, the city still owns and controls the park. They have a contract with CPC to run the park, and the Parks Department ensures contract compliance and mutual operations.51

CPC and the New York City renewed the contract to operate Central Park in 2006 for a second eight years, and in 2013 for a third eight years, for what will be twenty-four years of formal partnership and nineteen years of informal collaboration (1979–1998). By 2017, CPC provided approximately 75 percent of Central Park’s $67 million annual operating budget. Since 1980, CPC has invested $950 million in the park.52

MAKING SURE THE IMPROVEMENTS ARE SUSTAINABLE

CPC leadership stressed a long-term strategic approach from day one. A 1985 report commissioned by the CPC, “Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan” became the foundation of a comprehensive strategy to revitalize and maintain Central Park. That strategic approach, combined with project-by-project success and superior ongoing maintenance, encouraged more and more private donors, foundations, and corporations to invest in rebuilding and restoring Central Park (figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 The Great Lawn (a; photo by Sara Cedar Miller) and the Belvedere Castle (b; photo courtesy of CPC), have been fully restored due to the success and sustainable operations of the partnership between New York City Parks and the Central Park Conservancy.

Following the first two campaigns in 1987 and 1993, the Conservancy launched its third one, the Campaign for Central Park. That campaign concluded in 2008, raising $120 million, which enabled CPC to fund the continuing implementation of the 1985 restoration plan.53 In addition, the Conservancy created an endowment that it is hoped will permanently end the history of cyclical decline and restoration.54 On October 23, 2012, John A. Paulson (a hedge fund manager) announced a $100 million gift to the Central Park Conservancy, the largest donation in the history of the city’s park system. Half of the gift went to long-term operating support and the other half to capital improvements.55

In the summer of 2016, CPC announced an ambitious ten-year, $300 million plan, “Forever Green: Ensuring the Future of Central Park.”56 The new campaign will help fill the ongoing and growing need for maintenance in a huge park that also now has the challenging reality of over forty million visitors, often 250,000 in a single day. Among the projects to be funded from the new campaign are restoration of Belvedere Castle, dredging and repairing the Ravine in the North Woods, replacing and revitalizing much of the Naumburg Bandshell, restoring the badly deteriorating Dairy, and many other pressing infrastructure needs such as upgrading the irrigation and drainage systems. Less than a year into the campaign, the goal was raised to $500 million, with approximately $300 million planned for capital projects and $200 million for operating support and the endowment. By design, the capital budget schedule can be accelerated or stretched out, depending on the size of the endowment and the demands of the operating budget.57

HELPING OTHER PARKS AROUND THE CITY AND AROUND THE WORLD

Over the past several years, CPC created and expanded a new program, the Institute for Urban Parks, to share the knowledge and tools developed over nearly forty years of restoring and maintaining Central Park. The institute educates and trains urban park users and managers on how to care for urban parks in New York City, across the United States, and around the world, through more than a dozen management seminars and webinars annually. The institute also develops educational programming and experiences for children and their families on the importance of urban parks, how ecosystems work, and how to become responsible users and urban park stewards.58

Additionally, the institute offers apprenticeships, internships, and fellowships to aspiring park managers. Consulting services, including detailed manuals and training sessions on trash management and recycling and turf management, are given to park managers and workers throughout the city and across the region. The Conservancy’s Five Borough Crew program supports fifteen city park sites around New York City, including direct services, training programs, and management plans. In 2014 alone, the Conservancy spent more than $2.6 million in services to other parks.59

In 2015, CPC’s Institute for Urban Parks began working with students and faculty from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and Columbia’s Earth Institute to pilot a Certified Urban Park Manager (CUPM) education, training, examination, and certification program. Three successive capstone classes worked on building out the pilot program, and in the spring of 2016 CPC committed to launch a pilot test class for certification during 2017–18.60

In June 2016, the CPC and Forest Park Forever of St. Louis hosted a National Forum on Urban Park Sustainability and Public-Private Partnerships in New York City. Seven conservancies, one alliance, and a foundation came together to explore how they could work collectively to protect and improve their own parks over future generations and to share their learning with public and private urban park managers.

REDEFINING SUCCESS FOR NEARLY FOUR DECADES

Since 1979, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation and the Central Park Conservancy have partnered to rescue, restore, and enhance Central Park for the people of New York City and millions of visitors from all over the world. In 1978, Gordon Davis took over as Parks Commissioner when he and Betsy Rogers were perhaps the only people who could envision what we enjoy today. Working together as visionary, coordinated, and collaborative leaders, Rogers and Davis forged what has become a model for outstanding cross-sector partnerships like those profiled and analyzed in this book.

The success of the partnership goes beyond the boundaries of Central Park. The city’s economy stimulates restoration of the park every day, and the benefits are much greater than those generated by the spending of tourists visiting the park during their stays. A 2007 study found that the revitalized Central Park added $17.7 billion to property values around the park, an 18 percent premium, or about 8.1 percent of the total property value for all of Manhattan.61 Estimates of annual economic activity and revenues generated for the city by Central Park exceed $1 billion.62 By 2015, an updated economic impact study estimated that Central Park had added $26 billion to property values around the park, and the taxes and fees paid to New York City government attributable to the Conservancy and related Central Park enterprises totaled more than $1.4 billion for 2014 alone. The Conservancy itself employs over 450 with a payroll of $21.4 million.63

CPC and the revitalized Central Park do much more than generate additional taxes and increase property values in the area, as important as that is to New Yorkers. In 2014, the 41.8 million visitors to the park included 8.3 million from outside the United States and 13.7 million from outside the metropolitan region, supporting nearly 1,900 full-time job equivalents and over $200 million in economic output. As important, New York City residents made approximately 27 million visits to Central Park in 2014 for exercise, recreation, cultural, and entertainment activities, and the quiet appreciation of nature.64

Today Central Park is treasured by everyone, a space that is both a respite from the city that never sleeps and a free and open space enjoyed by many from around the world. Despite the heavy use, the Conservancy’s zero tolerance for both garbage and graffiti has changed the way people behave in the park. In the words of the Conservancy, “the American ideal of a great public park and its importance as a place to model and shape public behavior and enhance the quality of life for all its citizens once again defines the measurement of a great municipality.”65

Through the efforts of the Institute for Urban Parks, CPC is sharing its recipes for success with parks departments, conservancies, and aspiring parks professionals and volunteers from all over the world.66

THE HIGH LINE

Just across town and a few blocks south “a pair of nobodies…undertook [an] impossible mission”:67 use the Central Park Conservancy playbook to create a new urban park atop an abandoned elevated railroad track in what was then a rough neighborhood on Manhattan’s West Side (figure 5.5). A few years later there is now a public park known as the High Line, free and open to all. Already visited by millions from around the city and around the world, the High Line is a partnership between the New York City government and the Friends of the High Line. Similar to Central Park, the High Line is operated by the Friends of the High Line and most of the operating funds come from private donations.

Figure 5.5 The High Line as an active rail line in the 1930’s (a; photo by Fred Doyle); and abandoned and overgrown in the 1980’s (b). Photo courtesy of Friends of the Highline.

The West Side Line was once a very active commercial railroad line on the west side of Manhattan, serving the factories, meatpacking, dairy, and food stuffs businesses in the area. Western Electric built telephones beside the rail lines, and later Bell Telephone Laboratories conducted research there until 1966, when they moved to New Jersey. As trucks replaced rail as the primary distribution method in the 1950s and 1960s, traffic on the West Line declined precipitously. By 1960, the southernmost section of the West Line was demolished. In 1980, Conrail ceased using the remaining half of the line.68

During the 1970s, an attempt to reuse the line for passenger rail failed, and support for demolition of the elevated rail structure grew. At the same time, residents in the neighborhood started to become interested in the wild natural “garden” growing along the line. By 1999, the New York City government was ready to sign off on the demolition of the elevated tracks running from Gansevoort Street north to the 34th Street rail yards through Chelsea and the West Village.

A group of neighborhood residents, preservationists, naturalists, and artists had another idea. Led by residents Joshua David, a freelance magazine writer and editor, and Robert Hammond, who worked for a variety of entrepreneurial start-ups, they formed a nonprofit organization called Friends of the High Line.69 In almost every respect the creation and maturation of the Friends of the High Line reflects important aspects of collaborative cross-sector partnerships and leadership, which we analyze in chapter 6.

Initially, David and Hammond were focused on just preserving the railroad structure. Using the Central Park Conservancy as the model, the group determined that the best way to preserve the structure was to raise private and public funds to convert and operate the space as a linear, elevated park, not unlike the Promenade Plantée in Paris (also constructed on an abandoned railroad line).70 A federal program would permit the CSX rail company to transfer the property to New York City for park purposes.71 If the city chose to do so, it could work with Friends of the High Line to develop a revitalized residential and commercial neighborhood around the new public park.72

Fortuitously, there was a personal connection between Friends of the High Line and CPC—the families of Robert Hammond and Betsy Rogers were friends from previous days in San Antonio, Texas. As Robert Hammond said, “Betsy Barlow Rogers and the Central Park Conservancy had always been models for us. Theirs was an existing park, but a group of private citizens had come along, saved it from ruin, and then gone on to manage and operate it, raising the majority of funds to do so.”73

To persuade the city to go along with their vision, Friends of the High Line would need to find a way to finance both construction and ongoing operations and maintenance. John Alschuler, a nationally known and well-regarded real estate consultant (who later became board chair), advised the Friends team on how to structure the project. Designing it as a cross-sector partnership could deliver the park and open space at a lower cost than the city could do on its own and, over time, would make a significant “profit” for the city financially in terms of the incremental increase in real estate values, economic development, tourism, and higher income, sales, and property tax revenues. This would be the same Central Park effect that a similar study of Central Park found.74 Specifically, Alschuler’s study found that, while the High Line would be costly to build (his first estimate was low, predicting only $65 million), it would generate significant additional tax revenues to the city over its first twenty years of operation.75 Originally, this increase in revenue was estimated at $140 million, and was later revised to $900 million, indicating the amount of unexpected value unlocked through the partnership.76

Alschuler was a strong believer in the power of cross-sector partnerships to build and maintain great cities. He noted that the New York City subway system and regional commuter rail systems were both built with private capital and are now maintained and operated by public authorities. Central Park was originally built and maintained with public capital and was restored and now maintained and improved primarily with private capital and managed by a nonprofit entity. He believed the High Line could follow that same proven plan for sustainable success.77

The New York City government under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani did not favor the Friends’ vision for the High Line; in fact, the city had already begun plans to demolish the elevated structure. Friends of the High Line filed a lawsuit to block the action, but the city government never moved forward. The attacks of September 11, 2001, occupied the attention of Mayor Giuliani and his staff for the remainder of his term.

In January 2002, the new mayor Michael Bloomberg took office with the revitalization of Lower Manhattan one of his top priorities. As a successful businessman, he was already aware of the potential benefits of cross-sector partnerships, and he was and is a strong supporter of the Central Park Conservancy. Even as a candidate, Bloomberg had expressed support for the High Line.78 Beginning in 2002, Bloomberg, his first deputy mayor Patricia E. Harris, his deputy mayor for economic development Dan Doctoroff, Amanda Burden, chair of the City Planning Commission, and Parks commissioner Adrian Benepe all became active and supportive of the High Line project.79

“OUR GENERATION’S CENTRAL PARK”80

To capture public attention, in 2003 Friends of the High Line launched a light-hearted competition for the best ideas to reuse the old rail line. First place for the best idea went to building a lap pool along the entire length of nearly two miles; second place went to a roller coaster of the same length. Although many of the ideas were silly, the main objective—to bring attention to the High Line and engage the community—succeeded. A formal design competition in 2004 selected James Corner Field Operations, Piet Oudolf, and Diller Scofidio+Renfro as project leads and landscape architect.81 The team essentially had a blank—but challenging—canvas on which to work.

According to Amanda Burden, the city considered la Promenade Plantée in Paris as a model and sent the design team to visit it.82 The Promenade Plantée runs along the former path of the Vincennes railway line, which linked the Bastille station to Verneuil–l’Étang until 1969, after which it was replaced by a commuter rail line. In the 1980s, the entire Promenade Plantée area was redeveloped, and the Bastille station was demolished and replaced by the Opera Bastille. Landscaper Jacques Vergely and architect Philippe Mathieux designed the park to reuse the abandoned rail line between Bastille and the old Montempoivre gate to the city. The shops below the park were renovated in the late 1980s, and the Promenade Plantée was officially inaugurated in 1993.83

The Plantée was an interesting approach for the High Line development. The New York City government took a number of steps to make the park feasible and to ensure that the redevelopment had a major, positive economic effect for the city overall and would create a vibrant and diverse neighborhood. Previously zoned for light industry (the southern end is widely known as the Meatpacking District), the new Special West Chelsea district (from 16th Street to 30th Street, between 10th and 11th Avenues) allowed for a mix of manufacturing and art galleries and residential and commercial development. To gain the support of private owners under or adjacent to the proposed elevated park, those owners would be able to sell their development rights to properties on 10th and 11th Avenues, enabling developers to go higher and thereby make more money.84

This aspect of the project was crucial and substantial. Zoning changes to permit greater density and more profitable development uses attracted significant private investment, as well as fees and property taxes on higher property valuations, which made the High Line financially feasible and sustainable. Furthermore, there was a zoning bonus to exceed the zoning height limits, provided the developer pay a fee of $50 per square foot to the High Line Improvement Fund. This was attractive, as the market rate in the area was several hundred dollars per square foot. For the city, the fees and taxes from increased property values would help finance the long-term capital costs of the park. The owners of a large development in the area—Chelsea Market—convinced the City Planning Commission to expand the district north to include them. In return, the developer agreed to pay about a third of the $19 million fee for affordable housing and education programs for public housing in the neighborhood.85 Overall, the High Line financing plan led to an important portfolio of substantial, complementary investments necessary to help overcome common fiscal limitations on “public” projects.

BUILDING A SPECIAL PLACE

Development of the project was complicated by the number of partners involved. Superficially, it was a partnership between Friends of the High Line and the New York City government; in practice, New York City involved four different agencies—the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, the Department of City Planning, New York City Economic Development Corporation, and the Mayor’s Office. Despite the challenges of five sign-offs on every significant design issue, such as whether market-rate new buildings should have private entrances to the park, and many not-so-significant issues (such as twelve-inch versus eighteen-inch bench seat widths), a groundbreaking for the first section occurred in 2006. That first section, from Ganesvoort to West 20th Street, was opened to the public in 2009.86

Also in 2009, Friends of the High Line signed a formal partnership license agreement with the City of New York. Under the agreement, the city would own the elevated structure in exchange for fully funding the three phases of construction and restoration. Friends of the High Line agreed to raise funds from private sources to cover 90 percent of the park’s annual operation and maintenance costs, public programming, and community outreach.87 It is not surprising that the agreement mirrors that between the city and the Central Park Conservancy.

Even in 2009 New York City did not have the resources to adequately fund and manage the parks it already had (figure 5.6). At the same time, many of the donors who had helped sustain the project from the beginning would continue to contribute only if the vision and commitment of the Friends organization had a major role in its operations. So, as Joshua David said,

Neither Robert nor I ever felt that we would stand off to the side. But ultimately to occupy the central role, like that of the Central Park Conservancy, would mean stepping up and being the park’s primary funder—forever, basically…. We were setting up an organization that was aiming to run a public park in New York City.88

Figure 5.6 Friends of the High Line founders Joshua David and Robert Hammond on the High Line before its transformation began. Photo by Joan Garvin, courtesy of Friends of the Highline.

The second section of the park, from West 20th Street to West 30th Street opened to the public in 2011. Together, construction of the first two sections of the park cost a little over $152 million,89 nearly 75 percent provided by the city and roughly half the remaining covered between the federal government and private sources (New York State contributed $400,000).90 The third section, known as the Rail Yards, opened in September 2014 and runs from West 30th Street to 34th Street and cost about $75 million to construct.91 As New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman said, “Phase 3, like the rest of the High Line, cost more per acre than probably any park in human history.”92 At the same time, he also said, “If the newest last stretch of the High Line doesn’t make you fall in love with New York all over again, I really don’t know what to say.”93

What he did not say is that more and more of the cost of creating and maintaining the High Line was coming from private contributions raised by the Friends of the High Line. Encouraged by Alex von Furstenberg, a member of the Friends of the High Line board, his mother, Diane von Furstenberg, and her husband, Barry Diller, visited an exhibition on the High Line on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). A proposal for funding soon followed. Before the end of 2005, von Furstenberg and Diller pledged $5 million in support.94 In 2008, despite the onset of the world economic crisis (and charitable contributions drying up for organizations across the city), the Diller-von Furstenberg family made a $10 million challenge gift.95

In 2011, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced that the Barry Diller-Diane von Furstenberg Family Foundation was making a $20 million gift to pay for the design of the third phase and build the endowment for the park (this was on top of their previous gifts).96 It was the largest gift given to New York parks at that time, prior to the $100 million gift to Central Park by John Paulson. In addition to raising substantial funds for capital expenses and an endowment, the Friends of the High Line continues to cover nearly all of the park’s annual operating budget.97

Similar to Central Park and CPC, city officials and developers from all over the world—Rotterdam, Hong Kong, Jerusalem, Singapore, Chicago, Memphis, and Atlanta, just to name a few98—are coming to see the High Line, as much for its partnership model as for its innovative and spectacular design. The formal partnership between the city and Friends of the High Line is extremely important and is a key to the huge success of the High Line. Emeritus Friends board chair John Alschuler also stresses the importance of community involvement: “The most important partnership here is between engaged and passionate citizens and their government. These partnerships are economic. They’re legal. They’re civic. They are ways for the passion of citizens to be engaged in the democracy that reflects their values.”99

ALL THINGS TO ALL PEOPLE?

The High Line has already attracted over twenty million visitors from all over the world and the Friends organization has worked hard to be a good neighbor, as demonstrated in part by over 450 public programs and events hosted annually. Nine seasonal food vendors serve tourists and daily meals for people who live and work in the community. Over 120 artists from all over the world have exhibited in the park. It is also a public garden, with over 350 species of perennials, grasses, shrubs, vines, and trees, with plenty of spaces to walk, sit, read, chat, people watch, paint, take pictures, or just think. Due to the strong public-private efforts it took to create and sustain the High Line, today it is a free and public park owned by the City of New York.100

Just as Alschuler predicted, the High Line is proving to be a very good financial investment for the New York City government and its taxpayers (figure 5.7). City officials estimate that the first two sections alone have generated more than $2 billion in planned or new development.101 In 2016, the Wall Street Journal reported that the High Line was having a “halo effect” on properties along the park, with resale prices 10 percentage points higher than properties only a few blocks farther away.102 In 2016, when resale prices were softening throughout Manhattan, prices near the High Line (and Central Park) continued to rise. More restaurants and shops are serving the neighborhood, but the area retains its image of “hipness.”103

Figure 5.7 The High Line as it appears now, following its complete renovation. Photo courtesy of Friends of the Highline.

Twenty apartments in the High Line neighborhood have sold for $10 million or more since 2009, and the median price for condos has risen from $1,000 a square foot in 2009 to between $2,000 and $3,000 in 2016. In 2016, there were eleven projects with 155 apartments under construction and nine more with 751 apartments planned.104 Interestingly, the High Line park area has developed a reputation as family-friendly, and developers are building family-sized apartments to meet their needs. According to real estate experts, families that previously focused their home searches on the traditional family neighborhoods in the Upper East and Upper West Sides are also looking at the High Line area as a preferred location.105

Real estate development in New York City is often controversial and political. Before the High Line, the surrounding Chelsea neighborhood provoked images of a place where prostitutes were a familiar sight on the streets at all hours of the day, drugs were dealt openly and often accompanied by violent crimes, and the infamous Westies crime gang often ventured in from neighboring Hell’s Kitchen. The neighborhood continued to improve as the High Line was constructed and completed, and many observers worried about rising prices, higher densities, and gentrification. John Alschuler saw it another way,

One of the great things about New York is, we all coexist as part of a diverse neighborhood. It’s one of the reasons why public housing is so essential, [so] that when neighborhoods such as West Chelsea do transition, there are important blocks of housing that will be perpetually devoted to low and moderate income people and their future in a diverse neighborhood.106

Even as the neighborhoods around the High Line continue to attract new housing and commercial investment (some would call it gentrification), the High Line neighborhood remains the permanent and longtime home to three major New York City Housing Authority low-income developments with a total of two thousand apartments. Chelsea Houses has two twenty-one-story buildings on 1.71 acres, opened in 1964, and is located on Ninth Avenue between West 25th and West 26th Streets. Chelsea Houses Addition is a fourteen-story tower for seniors completed in 1968 on a one-acre parcel bordering Chelsea Park at West 26th Street and Tenth Avenue. Elliott Houses, four high-rise buildings, opened in 1947, covers 4.70 acres between West 25th Street, Ninth and Tenth Avenues, and Chelsea Park, and is named after John Lovejoy Elliott, who was passionate about one of the city’s worst neighborhoods and became a major force in getting the Elliott and Chelsea developments built. He was the founder of the Hudson Guild, which operates a summer camp program for young children in the area. Fulton Houses, eleven buildings between six- and twenty-five-stories tall, opened in 1965 on 6 acres located at Ninth Avenue between West 16th and West 19th Streets. The project is named after Robert Fulton who produced the first practical steamboat, the “Clermont”; its first successful voyage was from New Harbor, up the Hudson River, to Albany.107

Although the neighborhood now has one of the greatest levels of inequality in the city, the large number of public housing units in the community also makes it one of the most economically diverse. Due to vigilant civic engagement and responsible public policy, the public housing locations have never been seriously threatened with relocation, nor is there any imminent threat. A study in 2015 found that public housing residents in the area are benefiting from safer streets and better schools, and incomes of the residents are rising, probably due to better job opportunities in the neighborhood. Residents also enjoy the many free entertainment events organized by the Friends of the High Line. Nevertheless, longtime residents miss the many locally owned and operated stores whose spaces are now occupied by higher-end retailers and restaurants. Many residents must travel well outside the neighborhood to shop for lower-priced groceries and find more affordable restaurants.108

On balance, it seems that most people feel that things are better for the residents of public housing as a result of the High Line and the development it has spurred. As the vice president of the Elliot Houses tenants’ association (and president of the Hudson Guild advisory committee) told the New York Times, “I’d rather have Chelsea as it is today. There’s more people. It’s brighter, it’s beautiful, it’s more inviting than it used to be. We’re very lucky to be able to stay in housing that hopefully will not disappear.”109

BETTER PARKS THROUGH COLLABORATIVE LEADERSHIP

The renaissance of Central Park and the creation of the High Line are successes brought to fruition by cross-sector partnerships and exceptional, collaborative leadership. Neither park would exist if it weren’t for enlightened government officials (and the citizens that support them) such as Parks Administrator Frederick Law Olmstead, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis, mayors Ed Koch, David Dinkins, Rudy Giuliani, and Mike Bloomberg, and parks commissioners Henry Stern and Adrian Benepe. Despite best efforts though, even well-funded cities such as New York simply do not have the resources to sustain great parks consistently, and support from private partners and donors has proven indispensable.

Partnering with the Central Park Conservancy and the Friends of the High Line saved one great park and built a new one, thanks to a large number of consistently generous donors and a number of visionary and tireless collaborative leaders, particularly, Betsy Rogers, Doug Blonsky, and Ira Millstein for Central Park, and John Alschuler, Joshua David, Robert Hammond, and Phil Aarons for the High Line. The city did not, could not, and would not have done it on its own. The same could be said about Battery Park, Prospect Park, Brooklyn Bridge Park, Bryant Park, and many other great parks from Forest Park in St. Louis to Golden Gate Park in San Francisco.

With the majority of the world’s population living in cities (and expected to reach 66 percent by 2050),110 the world will need more and better urban parks—and it will take partnerships like those of Central Park and the High Line to meet the growing demand.

In recent years, New York City mayors Mike Bloomberg and Bill de Blasio significantly increased the public funding for parks, stemming decades of cuts in public dollars. Bloomberg spent hundreds of millions of city capital dollars to help create the High Line, the new Brooklyn Bridge Park, and parts of the Hudson River Park.111 Mayor de Blasio created three programs to help parks that have not yet attracted significant private investments. Five large parks, one in each borough, will get $30 million each between 2016 and 2020, and projects in the parks will be chosen in collaboration with the local communities. The second program, the Community Parks Initiative, will invest $285 million to improve sixty smaller parks around the city. And the Parks Without Borders program will spend $50 million to make parks more accessible and inviting by opening them up to the neighborhood streets and taking down high fences.112

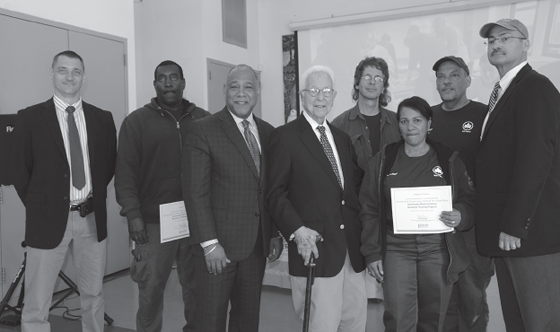

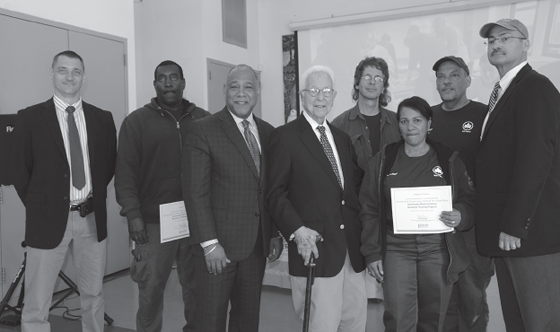

Current Parks Commissioner Mitchell Silver (figure 5.8), an active partner of the Central Park Conservancy and the Friends of the High Line, recently won a significant increase in Parks Department staffing, which had not happened in some time. We believe that the success of the Central Park and High Line partnerships has raised public consciousness about the importance of urban parks for all New Yorkers. That, coupled with the budget relief to the city government provided by all the private dollars flowing to the flagship parks with private partners, has enabled and encouraged city officials to provide significantly more tax dollars to the other city parks without access to private support.113

Figure 5.8 Graduates of the Community Parks Initiative Gardener Training Program in 2017. Attending the ceremony were New York City Parks Commissioner Mitchell J. Silver (third from the left), CPC Institute for Urban Parks Chair Ira Millstein (center) and Central Park Conservancy President Doug Blonsky (far right). Photo courtesy of CPC.

Success in cross-sector partnerships is best accomplished when everyone coordinates their efforts to achieve the maximum benefit for the people and the communities they serve. It also works best when each partner contributes its fair share of resources and effort to reach the partnership’s goal. And that is exactly why so many parks in New York City are better than they have ever been—and why millions of people from all over the city and all over the world enjoy them every day.

In chapter 6, we analyze how partnerships work best when leaders act collaboratively and their organizations operate as decentralized teams, each with its own expertise and areas of responsibility. Keeping partner organizations in alignment so that they are working efficiently and effectively toward common objectives and goals is a key responsibility of leaders. This is a complex and difficult task, and we outline how leaders can operate effectively when encountering unexpected challenges and opportunities.