Lecture 7

1 DECEMBER 1933

IN TODAY’S LECTURE, I shall discuss Mrs. Hauffe’s symptoms. Her case belongs to the field of mediumistic phenomena. Strictly speaking, these lie outside the field of medicine, and are part of parapsychology. I must mention these phenomena, however, since they do exist and are therefore psychologically important. We can well maintain a critical attitude toward these matters, but we have to heed the facts, keep our minds open, and prevent theoretical biases from obstructing our thinking.

Mrs. Hauffe’s condition was first and foremost of a somnambulistic nature: everyday consciousness slipped away from her. Somnambulism 208 is an exceptional psychic state, not a twilight state. For the Seeress, it constitutes a heightened state of consciousness that, for her, is actually the more normal state than the waking state. Such conditions involve great exertion, however, and therefore cannot be sustained for a long time. If she had managed to maintain these states, she would have been a “higher” being.

For instance, she speaks in verse. Other phenomena include visions and hallucinations; for example, she sees a mass of fire in her body. 209 This phenomenon can also be observed, by the way, in the case of ordinary neuroses; the visions are of a symbolic nature. Another phenomenon in her case is autoscopy: 210 for instance, she was lying in bed while seeing herself sitting beside it, 211 that is, she beheld an exteriorized image of herself. This is not unusual in such cases, and also occurs with the seriously ill and dying.

After that, her eye affliction recurred, and again she shunned light. 212 Outer light was painful to her, and so she concentrated on the inner light. She no longer looked out of the front door, so to speak, but out of the backdoor, into the depths of the subjective world, thus bringing about other positive manifestations of the unconscious, of the background. She saw all kinds of things which she projected into the outer world as ghost figures—some related to her, some related to other people. The ghosts provided her with treatment, notably with Mesmeric sayings 213 and magnetic manipulations. She frequently had a double vision of other people, since behind their personality, perceptible through the senses, there stood another that bore the qualities of the soul. 214

Her condition worsened rapidly on account of all these apparitions. She subsisted on a very poor diet; and when she came to Kerner in 1826 she was already in a very bad state, suffering from malnutrition and scurvy. 215 She had no appetite, which evinces a deficient will to live and corresponds to a sentiment of death, as we can also see in cases of melancholia. Fasting is also a technique in asceticism and yoga; deadening the drives depotentiates the outer world so that the vision can be directed purely inward.

As I mentioned, the Seeress came to Kerner in 1826. He attended to her and examined her as best he could, that is, in a most naive and primitive way. For instance, he firmly believed the nurse’s report of being unable to bathe the patient, since she would float on the water and could not be submerged:

When she was placed in a bath in this [magnetic] state, extraordinary phenomena were exhibited—namely, that her limbs, breast, and the lower part of her person, possessed by a strange elasticity, involuntarily emerged from the water. Her attendants used every effort to submerge her body, but she could not be kept down; and had she at these times been thrown into a river, she would no more have sunk than a cork.

“This circumstance,” Kerner continues, “reminds us of the test applied to witches, who were often, doubtless, persons under magnetic conditions; and thus, contrary to ordinary law, floated on water.” 216 In Basel, for example, witches were thrown bound by their hands and legs from the Rhine bridge into the waters. Those who had not drowned upon reaching the suburb of St. Johann were certain to be regarded as witches! It makes no difference whether or not this holds true for the Seeress. The fact remains that she affected others in a way so that they believed such things to be true about her.

She also developed a strange sense of, or a particular sensitivity to, the properties of materials, particularly of stones and minerals, which exerted a certain influence on her, thus prompting Kerner to conduct numerous experiments. 217 What this faculty is we do not know. With regard to her visual faculty, too, Kerner observed strange, crystallomantic phenomena in her. Some people, when placed before a mirror or crystal ball, see things that are not there, that is, past, present, and future events; some are actually hypnotized by this. Crystal balls were one of the props employed by medieval sorcerers. They also served divinatory purposes 218 in China. What such people see, if anything at all, are of course processes from their own unconscious.

The Seeress also possessed this faculty when Kerner placed her under hypnosis. He describes one of his experiments thus:

A child happening to blow soap-bubbles: She exclaimed, “Ah, my God! I behold in the bubbles every thing I can think of, although it be distant—not in little, but as large as life—but it frightens me.” I then made a soap-bubble, and bade her look for her child that was far away. She said she saw him in bed, and it gave her much pleasure. At another time she saw my wife, who was in another house, and described precisely the situation she was in at the moment—a point I took care immediately to ascertain. 219

On another occasion, she looked into a glass of water and saw in it a carriage that did in fact pass them by twenty minutes later. 220 Here I would like to remind you of the scène de la carafe in Dumas’s Joseph Balsamo. 221 These are ancient magical practices, and it is not impossible, after all, that they are true. As I mentioned, however, we must leave aside this question at this juncture.

Not only could the Seeress see with her eyes, but also with the pit of her stomach, in that she could recognize objects placed there. Kerner writes:

I gave Mrs. H– two pieces of paper, carefully folded: on one of which I had secretly written, “There is a God”; on the other, “There is no God.” I put them into her left hand, when she was apparently awake, and asked her if she felt any difference between them. After a pause, she returned me the first, and said, “This gives me a sensation, the other feels like a void.” I repeated the experiment four times, and always with the same result. 222

In a further experiment, Kerner wrote on one piece of paper, “There are spectres,” and on another, “There are no spectres.” “She laid the first on the pit of her stomach, and held the other in her hand, and read them both.” 223 The fact that the visual sense is transferred onto another sense is not unique. Rather, it is said to occur in other cases, such as when one places one’s hand upon an object in order to see something. In this regard, I refer to the famous American medium Mrs. Piper, who was William James’s medium, and who placed letters upon her forehead in order to read them. 224 In those days, it was believed that such experiments only succeed when those who have written the letters in question were still alive. One of Mrs. Piper’s female friends bequeathed a letter to her, depositing it at a bank. When the friend died, the letter was fetched from the bank, and placed with the envelope upon the medium’s forehead. She focused on it with utmost concentration, much more than customarily, and eventually she said: “I believe it says thus and so”; the contents, however, were in fact utterly different. 225

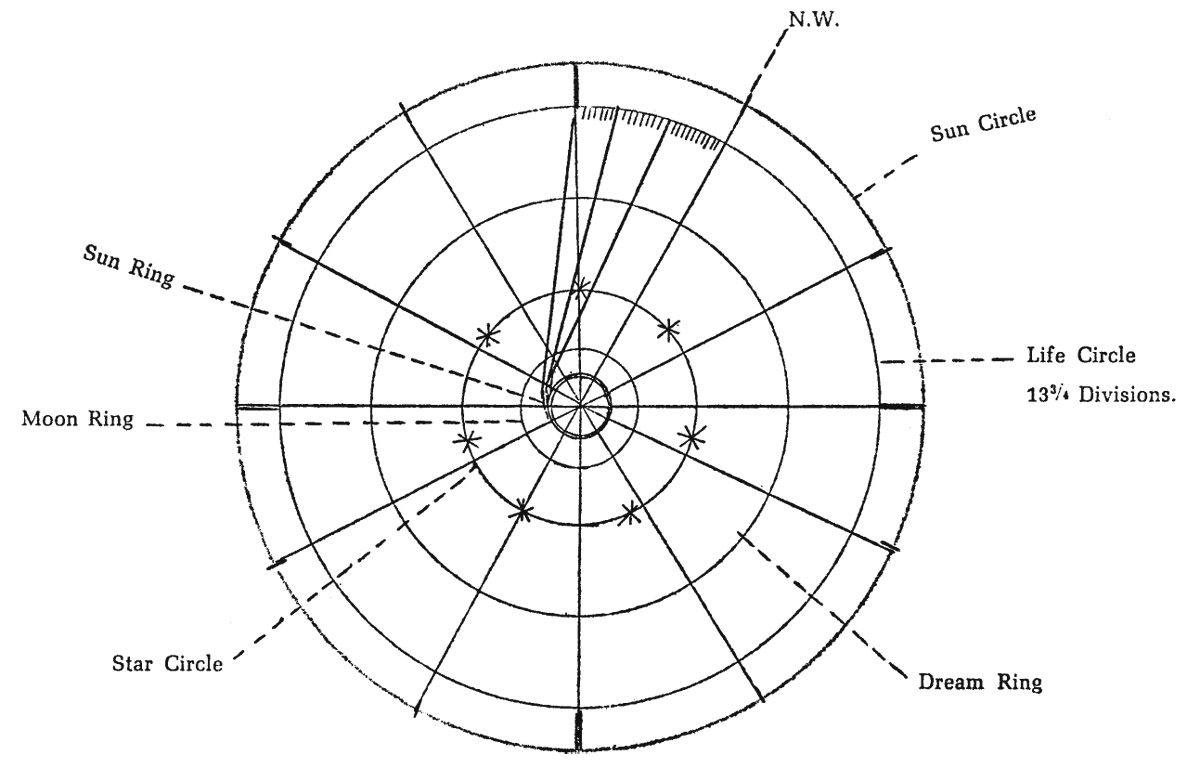

Up until that time, the visions and perceptions that had occurred to the Seeress bore reference solely to outer matters, in other words ones that could ultimately be verified. Then, however, she had a rather curious vision that dumbfounded Kerner, and that used to baffle me, too—namely, the vision of a sun-sphere. In her vision, it assumed the shape of a real solar disc, situated in the region of the stomach or of the solar plexus. The disc rotated slowly and scratched her, thus agitating her nerves. 226 Later she had such a distinct vision of this sun-sphere that she could furnish a very interesting drawing of it.

Four points are indicated on the circle, 227 but we have no knowledge what they mean. 228 The [outer] sun circle is divided into twelve parts or segments, corresponding to the twelve months, that is, the zodiacal circle or the sun year. This sun circle is the sixth one; under it lie five others, and above it a seventh, empty circle. 229 We must picture these things as though they were lying in a horizontal position. This is how the vision appeared. For us the concept of an empty circle is an extremely strange idea, for we have lost touch with such matters, because we are accustomed to constantly directing our attention outward and only rarely do we turn to look inward. Any educated Hindu, however, will immediately recognize the meaning. Since this empty circle does not appear in the drawing, the sun circle represents the outermost circle or the circumference.

The next [fifth] circle is divided into thirteen and three-quarter segments, which correspond roughly to a lunar cycle of 27.3 days. Thus, the Chinese not only have a solar cycle, but also one that follows the course of the moon. The whole is therefore a kind of time wheel that has sun divisions as well as moon divisions. This fifth or life circle she called her “calendar,” upon which she entered minute strokes to record facts or experiences that affected her in a pleasant or unpleasant way: headaches, heart cramp, and so on.

The circles lie under each other and rotate, with rotation commencing in the northwestern point. Thus, this curious calendrical calculation begins in the northwest—and, regarding direction, moves not clockwise but counterclockwise as in the German swastika. Whereas the lines for the month run radially from the sun circle straight to the center, the lines from the life circle are drawn at a tangent, so that what emerges is not a rotating but rather a spiraling movement.

Next comes the fourth circle, which is also divided into twelve segments. 230 She referred to it as the “dream ring” or the “realm of the souls of animals.” This is difficult to explain, since Kerner’s account is unclear. These three constitute the outer circles.

The third circle, which is the outermost of the three inner circles, is characterized by a division into seven segments; it is the circle of the seven stars. Next comes the second circle, the “moon ring,” and finally the innermost circle, the so-called sun ring, which is bright and shines like a sun. In this center, there is also the spirit and the truth. She called it the “bright mid-point,” the “sun of grace.” Of this, she caught merely a fleeting glimpse, during which she beheld her “conductress” or protecting spirit [Führerin]; she believed, furthermore, that with her many other ghosts had peered inside.

The Seeress said that the sun circle was like a wall, through which nothing could reach her. 231 Outside lay the bright everyday world, where life was dreadful, and she therefore preferred to remain confined within these rings. In her drawing, she depicted people as little hooks, pointed and unpleasant. She felt them as blue flames on the outer ring, not at all corporeal, but only ideational. For her, Justinus Kerner was the mediator between herself and the dangerous outer world.

About the first, central circle she said that she would feel comfortable there, looking from there into the world, the paradisiacal world, that is—by which she means the inner world—in which she had once been. She asserted that the [second] moon ring was a cold and bleak sphere, representing the abode of the souls in the “intermediate region.” She shuddered to think of it and was scared of it. She had only vague recollections of it because out of fear she “only swam hither and thither over it.” From there, the souls entered either the sun or the stars. This, too, is a strange idea, unless we consider it in the light of history: since time immemorial the moon was thought of as receptaculum animarum, the seat of the souls. Manichaeism explains the waxing and waning of the moon each month as its filling with the souls of the deceased until it is filled completely, turns towards the sun, gives the souls to it and thus is on the wane again. Then a new circle begins. This idea was brought from Beijing to southern France through the heretic teachings of the Albigenses. 232 Today, this obviously strikes us as an old tale, but such matters remain pertinent. One fantasy claims that after the [First] World War all souls arrived on the moon and fertilized it so much that grass began to grow there. 233

We see that, in the case of the Seeress, we are dealing with the revival of an archaic image, a palingenesis, unless, that is, somebody had insinuated that idea to her in her past, although this is quite unlikely in view of her strictly Catholic environment. The notion that souls wander from the moon to the stars is not new, either: stars have been associated with birth and death since time immemorial. Meteors are souls. Or when a Roman Caesar died the astronomers had to find a new star in the sky to account for his soul. We also find this idea in the Indians and in poetic language. The fact that there are seven stars corresponds to a mythological conception: seven is a sacred number, just as all cardinal numbers from one to nine are sacred, in different ways in different peoples.

The reason for this is that primitives can solely count to ten, since they can count only their 2 × 5 fingers. For instance, Swahili 234 has only five numerals; numbers greater than five are designated by “many,” whether this be six, a thousand, or a hundred thousand. Before the outbreak of the First World War, rumor had it in East Africa that one thousand 235 German soldiers had marched through the region. Troops were committed to investigate the incident, and it turned out that only a patrol of six men had been seen! Failing a corresponding word for the actual number, the corporal who made the sighting had simply reported “many.” Many: nyingi; very many: nyingi sana. But when very many are meant, perhaps a million, their voices imitate the throwing of a stone: very many: nyingy sa-a-na—a. Besides, primitives associate numbers with geometrical figures: for example, 2 = II; 3 = III or ∆; 4 = IIII or □. Their conception of numbers is entirely unarithmetic. Thus, for instance, two matchsticks plus one matchstick does not equal three matchsticks, but two two-matchsticks and one one-matchstick. The number is a quality that inheres in the matchstick. A “three-matchstick” cannot turn into a “four.” Such thinking results from the magical character of all perceptions among these people.

Therefore they can count without being able to count. For instance, they base counting on images, such as the one that grows from a herd or the size of the plot of land occupied by a herd. One native owned a herd of approximately 150 cows, which he would count every evening. But he could count only to ten. He knew the name of each cow, however, and immediately noticed when a particular cow was missing.

208. Here, not sleepwalking, but an altered state of consciousness, a kind of “sleep-waking” state, or “magnetic sleep,” a condition, however, we “must not call . . . sleep—it is rather a state of the most perfect vigilance” (Seeress, p. 24). Already Armand de Puységur (1751–1825), a disciple of Mesmer (see below) and a pioneer of magnetism, described how people in that state were able to diagnose their illness, to foresee its course, and to prescribe the correct treatment.

209. “At one time, she spoke for three days only in verse; and at another, she saw for the same period nothing but a ball of fire, that ran through her whole body as if on thin bright threads” (ibid., p. 44).

210. The experience of seeing one’s own body from a vantage point or position outside of the physical body.

211. Ibid., p. 44; cf. pp. 57–58.

212. Ibid., p. 44.

213. Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815), German physician, and famous, charismatic, and highly controversial healer. Noted for his theory and practice of “animal magnetism.” Kerner was well acquainted with his ideas—he himself had been cured from a nervous affliction, as a boy, by a “magnetic” cure—and in his old age paid homage to Mesmer in a monograph (Kerner, 1856).

214. “When Mrs. H– looked into the right eye of a person, she saw . . . the picture of that person’s inner-self. . . . If she looked into the left eye, she saw immediately whatever internal disease existed . . . and prescribed for it” (Seeress, pp. 73–74). In other instances, she saw “another person behind the one she was looking at,” for example, “behind her youngest sister she saw her deceased brother” (ibid., p. 46).

215. Her gums had become scorbutic, and she had “lost all her teeth” (ibid., p. 52). The ultimate cause of scurvy—a deficiency of vitamin C—was not known until 1932, and treatment was inconsistent.

216. Ibid., pp. 65–66.

217. Cf. Seeress, chapter 8. Only fragments of this chapter appeared in the English edition of 1845.

218. That is, the art of prophecy.

219. Ibid., pp. 74–75.

220. “She . . . saw . . . a carriage travelling on the road to B–, which was not visible from where she was. She described the vehicle, the persons that were in it, the horses, &c.; and in half an hour afterwards this equipage arrived at the house” (ibid., pp. 46–47).

222. Ibid., pp. 75–76.

223. Ibid.

224. Cf. James, 1886, 1890b, 1909. Leonora Piper (1857–1950) was a famous American medium, and the subject of investigation, apart from William James, of leading psi researchers at the time.

225. A detailed description of this experiment is in Sage, 1904, chapter 7 (pp. 52–64).

226. Seeress, p. 114; the chapter on “Spheres” was heavily abridged in the English translation of 1845, so that the mentioned details are missing there.

227. The following descriptions of the seven circles or rings differ considerably in the various lecture notes, and sometimes they even contradict one another. I have attempted to “extract” a description that is as clear as possible and in accordance with Kerner’s account (which is itself rather unclear, as Jung duly notes), which facilitates reading, but also means that this is the passage of which we can least be sure that it is a faithful and more or less literal reproduction of what Jung actually said. The numbering of the circles, too, is inconsistent—sometimes they are counted from the center to the periphery, sometimes the other way around, even by Mrs. Hauffe herself. To avoid confusion, this has been standardized to the second method here.

228. These are the four “cardinal points”; see the beginning of the next lecture.

229. Ich fühle unter diesem Ringe noch fünf solcher Ringe und über ihm noch einen leeren [I feel that there are another five spheres beneath this one, and above it one other, empty sphere], the Seeress is quoted by Kerner (only in German edition of Seeress, p. 114).

230. The description of the spheres and the following quotes are in Seeress, ed. 2012, pp. 114 sqq., and ed. 1845, pp. 114–115, 130–131.

231. durch die nichts an mich konnte (p. 115). The English translation is misleading: “like a wall, beyond which she could not move” (p. 130).

232. The Albigenses, or Cathars, represented the most influential Christian heretical movement in the Middle Ages, thriving in some areas of Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France, between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries.

233. In general, “[a]ccording to the ancient belief, the moon is the gathering-place of departed souls” (Transformations, § 487), “the abode [receptaculum] of departed souls” (Jung, 1927 [1931], § 330). The claim that the moon was so fertilized by the many souls of soldiers killed during the First World War that a green spot appeared on it goes back to the Greek-Armenian mystic, writer, composer, and choreographer, George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (1866? –1949). According to Gurdjieff, the moon feeds on souls, and when the moon is very hungry, there are wars. Jung quoted this story also in his seminar on children’s dreams (Jung, 1987 [2008], p. 167). In Barbara Hannah’s English edition of these lectures, however, and in contrast to all other lecture notes, this belief of Gurdjieff’s is rendered differently: he would have been “convinced that the spots on the sun are caused by the unusual number of souls that migrated there during the war, and I [Jung] have met two doctors who firmly believe him” (p. 35; italics added).

234. Jung had learned some Swahili for his stay at Mount Elgon, and “manage[d] to speak to [the natives] by making ample use of a small dictionary” (Memories, p. 294).

235. In Hannah: “10,000” (p. 35).