![]()

![]()

Personal and treatment factors

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Medications that prevent blood vessel growth

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Central nervous system metastases

![]()

![]()

When breast cancer spreads to other organs, such as the bones, lungs or liver, it’s referred to as advanced breast cancer. Other terms commonly used are metastatic cancer or stage IV cancer. Some women have advanced breast cancer when they’re first diagnosed, but more often it develops when the cancer recurs.

Usually, women with metastatic breast cancer have been through diagnosis and treatment before, when their original tumors were first found. The process of diagnosis and treatment this time has some similarities to that first experience, but it also has some key differences. This chapter focuses on the evaluation and treatment of women with metastatic breast cancer.

Whether or not this is your first experience with breast cancer, you may be thinking that not much can be done for advanced breast cancer. In fact, treatment options are available for breast cancer in its later stages. Even though stage IV breast cancer typically can’t be cured, treatment may provide long-term control of the disease. As breast cancer treatments become more and more effective, women are surviving longer with metastatic breast cancer.

Metastatic breast cancer isn’t a simple, uniform disease. Instead of viewing it as a single entity, picture it as a spectrum. At one end of the spectrum is a rapidly progressive disease with extensive spread to vital organs. At this end, the disease may be resistant to hormone therapy and chemotherapy. Average survival may be measured in terms of a few months.

At the other end of the spectrum are instances where the cancer follows a long, slow course. Women in this situation generally have cancer spread to bone or soft tissue, but their internal organs aren’t affected. At this end, the disease tends to be more sensitive to hormone therapy and chemotherapy. Women with this type of recurrence may live for years or, occasionally, decades. Very rarely, a woman will do well for decades without treatment to halt the disease’s progression.

In general, the average length of survival for women who receive a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer is between two and three years. But survival may vary considerably, based on various tumor behaviors.

In predicting how a woman’s cancer will behave and the disease’s likely course, doctors rely on a number of factors (prognostic factors). These involve not only characteristics of the disease but also factors related to the person being treated and the type of treatment received.

Disease characteristics

Characteristics related to the cancer can help determine how it may behave:

Disease-free interval

The disease-free interval refers to the time from initial diagnosis to recurrence. This is often one of the best predictors of how the cancer will act after it has recurred.

Women who develop evidence of metastatic breast cancer early on, while they’re still receiving initial treatment for breast cancer or soon after treatment ends, generally have a very poor prognosis. If, on the other hand, metastatic breast cancer becomes apparent 10 to 15 years after the initial diagnosis, the course of the disease is often slow and the prognosis better.

Hormone receptor status

Women with hormone receptor positive breast cancer — estrogen receptor positive, progesterone receptor positive or both — generally have a slower disease course than do women with hormone receptor negative cancers.

Prognostic factors in metastatic breast cancer

Disease characteristics

Disease-free period between initial diagnosis and metastatic recurrence

Hormone receptor status

HER2 status

Locations of disease

Extent of disease

Personal and treatment factors

Ability to get around (performance status)

Presence of other medical conditions

Prior treatment

Age

HER2 status

In the past, it was generally noted that women with HER2-positive cancers had a poorer prognosis than did women whose tumors were HER2 negative. HER2-positive cancers are more aggressive and less sensitive to hormone treatments.

However, HER2-targeted drugs such as trastuzumab (Herceptin) provide a new form of treatment for women with HER2-positive cancers. The drugs have greatly improved long-term outcomes.

Locations of disease

Women with metastatic disease that’s limited to the skin, lymph nodes or bones generally have a better prognosis, compared with women who have tumors in multiple sites or in the liver or brain. Women with cancer in the lungs or the tissue surrounding them have an intermediate prognosis.

Extent of disease

Women with only small amounts of metastatic disease tend to do better than do women with extensive disease.

Personal and treatment factors

A number of personal and treatment factors also can affect your prognosis, including mobility, other medical conditions, prior treatment and age.

Mobility

Mobility (performance status) refers to your ability to be up and about and to carry on normal activities. Your mobility helps determine how well you may tolerate certain treatments and how likely these treatments are to help.

Other medical conditions

Conditions such as heart disease, stroke or diabetes can affect your prognosis.

Prior treatment

How well a person with metastatic disease will do may be affected by the extent of the treatment she received when her breast cancer was originally diagnosed.

Your doctor will review your breast cancer history. He or she will also look at the speed at which your cancer has progressed. For example, did the cancer’s spread become apparent 10 years after your initial diagnosis? Or did it occur two months after the completion of your initial treatment? These are two very different scenarios that have different effects on prognosis and treatment decisions.

Age

Whether age affects the course of breast cancer after it becomes metastatic is a matter of debate. Some data suggest that particularly young women or older women have poorer prognoses.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Whether hormone therapy or chemotherapy actually prolongs survival in women with metastatic breast cancer has never been put to a proper scientific test. Doing so would mean that half the participants in the trial would receive drug therapy and the other half would receive no treatment. Because drug therapy appears to benefit the vast majority of women with breast cancer, it’s generally considered unethical to conduct a trial that would deny treatment to half the participants.

Based on available information, it appears that women who receive hormone therapy or chemotherapy or a combination of the two do live longer than do women who don’t receive such treatment. How much of a benefit is achieved? An average improvement in survival of a year or two appears to be a reasonable estimate. This average includes some women who clearly live many years longer than would have been expected if they had never received such treatment.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Because the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, treatment for metastatic breast cancer generally involves whole-body (systemic) therapy rather than local therapy, such as surgery or radiation. Several options are available, including:

You may find that there are easily 10 to 20 different options that may be used to treat metastatic breast cancer. You’ll want to work with your doctor to decide which option is most appropriate for you. In addition, if one treatment doesn’t work or stops working, you will likely be able to try other treatments.

Treatment goals

When devising a therapy plan, you and your doctor may want to address two important questions:

The answer to the first question generally is no. Curing metastatic breast cancer isn’t a realistic goal. However, in the majority of women, it can be controlled. This generally means reducing the size of the tumors, controlling symptoms and minimizing toxic effects from the medications. The goal of your treatment is to help you live as well as possible for as long as possible.

This doesn’t mean, though, that women have never been cured of advanced breast cancer — meaning that the answer to the second question may be yes. Although being cured typically isn’t a goal of metastatic breast cancer treatment, occasionally — maybe 1 to 3 percent of the time — women with metastatic breast cancer will experience a complete remission of their disease that lasts 10 to 15 years or longer. Women with isolated metastatic cancer are more likely to experience a cure than women whose cancer is widespread.

![]()

QUESTION & ANSWER

Q: How do you know when you’re past menopause?

A: The definition of menopausal status varies. One definition that’s commonly used is the absence of any menstrual period for at least 12 months. In some situations, such as if your period has ceased for other reasons, this may not apply. For example, in women whose ovaries are intact but who no longer have a uterus, this definition isn’t useful. If your menopausal status is unclear, blood tests may be obtained to help determine your hormone levels. The tests may reveal whether you’re premenopausal or postmenopausal, but often the answer isn’t clear-cut.

Hormone therapy

It’s well known that the female hormones estrogen and progesterone influence the growth and development of a majority of breast cancers. As a result, breast cancers that make receptors for estrogen and progesterone — referred to as hormone receptor positive cancers — can be treated with hormone therapy.

Your menopausal status is often the first thing a doctor evaluates in determining your hormone therapy options. Treatment options are different for premenopausal and postmenopausal women, primarily because of the difference in the levels of estrogen in their bodies. Premenopausal women have high estrogen levels. In postmenopausal women, the ovaries no longer produce estrogen or progesterone, but the adrenal glands and fat tissue still continue to produce some estrogen, although in reduced amounts.

Premenopausal women

There are different ways to moderate the influence of estrogen and progesterone in premenopausal women whose ovaries are still fully functional. Treatment options include ovarian suppression, tamoxifen or both.

Ovarian suppression

One of the oldest methods of hormone therapy is ovarian suppression — keeping the ovaries from producing estrogen and progesterone. This can be done by surgically removing them (oophorectomy), radiating them or using medications.

Oophorectomy. The first description of the use of oophorectomy to treat metastatic breast cancer dates back to 1896 by Sir George Beatson. He had previously noted hormone changes in animals when their ovaries were removed. So he performed an oophorectomy in a young woman with recurrent breast cancer who was willing to try the experiment. Within months, there was a dramatic shrinkage of the young woman’s cancer.

For many decades following, oophorectomy became the mainstay of treatment for premenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer, with approximately one-third of the women responding to the therapy.

When medical scientists found a way to identify the presence or absence of estrogen and progesterone receptors on breast cancer cells — indicating whether the cancer was sensitive to hormones — responses could be better predicted. Women with estrogen receptor positive cancers have approximately a 60 percent response rate to oophorectomy, whereas only about 10 percent or less of women with estrogen receptor negative cancers respond to this therapy. The highest response rates to ovarian suppression are generally seen in women who have cancers with both estrogen and progesterone receptors and who experience a long duration between initial treatment and relapse.

Although oophorectomy is a century-old procedure, it’s still a viable and effective treatment option.

Medications. Another method of suppressing the ovaries is with a group of drugs called luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) agonists. These include drugs such as goserelin (Zoladex), leuprolide (Lupron) and triptorelin (Trelstar).

The medications, generally given by injection once a month, effectively shut off ovarian function. They’re used instead of surgery in a large number of women. This means ovarian suppression may be reversible by stopping the medications. However, depending on how close to menopause a woman is and how long she takes these drugs, her ovaries may shut down permanently.

Tamoxifen

The medication tamoxifen is another form of hormone treatment for women with metastatic breast cancer. It differs from drugs used in hormone suppression in that it doesn’t prevent the ovaries from producing female hormones. Tamoxifen is a synthetic hormone belonging to a class of drugs known as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). It works by keeping estrogen from attaching to estrogen receptors on breast cancer cells, thus blocking estrogen’s influence on the tumor’s growth (see Tamoxifen’s Dual Role).

Tamoxifen is as effective as oophorectomy among women with metastatic breast cancer, and because it’s less invasive than is oophorectomy, it’s become a common form of hormone therapy for premenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer. For more information on tamoxifen, see Chapter 11.

Tamoxifen and ovarian suppression

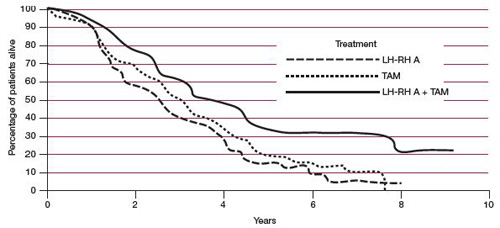

A clinical trial conducted in Europe tested the idea of combining tamoxifen and the LH-RH agonist buserelin to see if the combination would improve treatment results. In the trial, 161 premenopausal estrogen receptor positive women with metastatic breast cancer were randomly selected to receive one of three treatments: tamoxifen only, buserelin only, or both tamoxifen and buserelin.

After about seven years of follow-up, the results showed an overall benefit in survival for the group that received the drug combination, compared with the group that received only one medication (see the graph above). Average survival with the combination approach was approximately one year greater compared, with the single-drug approach. Thirty-four percent of the participants receiving the drug combination were still alive five years after they started their treatment, compared with approximately 15 percent of the participants who received only one of the drugs. Other similar trials generally reached the same conclusion.

Based on this information, a common approach to treatment for premenopausal women with hormone receptor positive metastatic breast cancer is a combination of ovarian suppression and tamoxifen.

Other options

If the combination of ovarian suppression and tamoxifen isn’t effective and your doctor thinks that it’s reasonable to consider another form of hormone therapy, several approaches are possible. The drug megestrol acetate (Megace), which is a progesterone medication, and the androgenic agent fluoxymesterone, which is similar to testosterone, have been used. More often, though, doctors are prescribing medications called aromatase inhibitors in combination with continued ovarian suppression. In women who are premenopausal, aromatase inhibitors are effective only when other treatment is included that stops the ovaries from functioning. The drugs aren’t effective if your ovaries are still making estrogen.

Combination hormone treatment improves survival

LH-RH A = luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (buserelin). TAM = tamoxifen LH-RH A + TAM = buserelin plus tamoxifen.

Source: J. G. M. Klijn et al., Combined Treatment With Buserelin and Tamoxifen in Premenopausal Metastatic Breast Cancer: a Randomized Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2000;92(11):903.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

The goal of treatment for metastatic breast cancer is to have you do as well as possible for as long as possible. Finding therapies with the best response rate and the fewest side effects is important.

Hormone therapy is generally associated with fewer side effects than is chemotherapy. A common initial impression is that chemotherapy is better and more powerful than is hormone therapy and therefore should be used first.

In some situations, though, hormone therapy may have a better chance of fighting the cancer than will chemotherapy. In addition, several studies have shown that people receiving hormone therapy as initial treatment for metastatic breast cancer do as well in terms of survival and life quality as do women who receive chemotherapy as their initial treatment.

Here’s an example. A woman with estrogen receptor positive and progesterone receptor positive breast cancer develops a couple of small metastatic tumors in the lungs 10 years after she was initially diagnosed with breast cancer. Chances are that this woman may have a higher response rate to hormone therapy (about 80 percent) than to chemotherapy (60 to 70 percent).

Factors that tend to predict that hormone therapy will be helpful include:

In general, hormone therapy is recommended if you have a reasonable chance of responding well to it, and the extent of the cancer is such that you can safely wait a month or two to see if the therapy is working.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Postmenopausal women

In postmenopausal women, ovarian suppression isn’t necessary because the ovaries have already stopped producing estrogen. However, a number of other treatment options are available to this group.

Treatment for postmenopausal women with hormone-responsive breast cancer has changed dramatically over the past 40 years. Tamoxifen was the first-line agent for many years. However, accumulating evidence shows that, compared with tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors produce better response rates and they slightly improve survival. Following are hormone therapies used to treat hormone-responsive metastatic breast cancer.

High-dose estrogen vs. tamoxifen

Four to five decades ago, the primary form of hormone therapy for postmenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer was high doses of estrogen in the form of a hormone called diethylstilbestrol (DES). Although this sounds strange because estrogen can stimulate cancer growth, in a substantial percentage of women, very high doses of estrogen cause tumors to shrink.

When tamoxifen became available, studies found both methods to be similarly effective. But tamoxifen became the standard treatment approach because it was less toxic than was DES. In some situations, however, high-dose estrogen treatment may still be used.

Aromatase inhibitors

Before the availability of tamoxifen, another type of hormone therapy for postmenopausal women was surgical removal of the adrenal glands — the organs located just above the kidneys. The adrenal glands produce a variety of hormones including androgens. An enzyme called aromatase found in fat cells and breast tissue turns androgen into estrogen. In postmenopausal women, this becomes one of the main sources of estrogen.

Eventually, this surgical procedure was replaced by the invention of a class of medications called aromatase inhibitors, which suppress aromatase enzymes, preventing the conversion of androgen to estrogen. Currently, three aromatase inhibitors are in use, which appear to be equally effective: anastrozole (Arimidex), letrozole (Femara) and exemestane (Aromasin).

In randomized trials comparing aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors appear to suppress the cancer’s growth rate for a longer period of time than does tamoxifen, and they increase average survival times slightly. Based on these studies, doctors usually recommend aromatase inhibitors as initial treatment for postmenopausal metastatic breast cancer that’s hormone receptor positive.

However, other factors may influence which medication your doctor recommends first. These include the type of side effects produced by each drug, their cost — currently tamoxifen is cheaper — and whether one of the medications was already used when the cancer was first diagnosed and treated.

Researchers are now studying if it’s best to prescribe an aromatase inhibitor with another medication. Results of one trial found that women who received an aromatase inhibitor combined with an investigational medication called everolimus (Afinitor) did better than women who received an aromatase inhibitor alone. However, further study is still needed.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Interestingly, one way of shrinking breast cancer tumors is to take away a hormone medication that was previously effective. Although this may seem like a paradox, it does sometimes work.

This type of response was initially observed when high doses of estrogen, in the form of diethylstilbestrol (DES) therapy, were used to treat metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

In women who received this therapy and experienced tumor shrinkage but later experienced regrowth, stopping the DES therapy caused the cancers to shrink again. This was called DES withdrawal.

What seems to be occurring is that after long exposure to hormone treatment, the cancer cells figure out how to grow during the treatment and are even stimulated by the medication. This same phenomenon has been seen with other types of hormone therapy, including tamoxifen, for women with breast cancer. It also has been seen in men with prostate cancer, another type of hormone-responsive cancer.

What all this means is that sometimes just stopping use of a previously effective hormone medication can in itself be an effective form of treatment.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Fulvestrant

Fulvestrant (Faslodex) is an estrogen receptor antagonist that may be helpful for women whose cancer has become resistant to tamoxifen. Whereas tamoxifen works by blocking estrogen, and aromatase inhibitors work by preventing the production of estrogen, fulvestrant works by destroying estrogen receptors in breast cancer cells. Clinical trials involving this medication show its benefits to be similar to those of aromatase inhibitors.

Others

Older hormone therapies also may be considered in postmenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer if other therapies don’t work. These include megestrol acetate (Megace) and fluoxymesterone. These therapies can produce side effects. You and your doctor will need to consider the potential benefits and disadvantages of these options.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Classes of chemotherapy drugs used to treat metastatic breast cancer include:

Anti-tumor antibiotics

Different from antibiotics used to treat bacterial infections, anti-tumor antibiotics inhibit the ability of cancer cells to multiply by interfering with DNA and by blocking RNA and key enzymes.

Mitotic inhibitors

Mitotic inhibitors disrupt division of individual cells by interfering with the specific cellular machinery that separates dividing cells into daughter cells.

Vinca alkaloids

Vinca alkaloids are another form of mitotic inhibitors. They work similarly to taxanes.

Anti-metabolites

Anti-metabolites are medications that block enzymes vital to cancer cell growth by interfering with the synthesis of DNA.

Alkylating agents

Alkylating agents interfere with the rapid growth of cancer cells by forming direct chemical bonds with DNA, inhibiting its function.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is most often used to treat metastatic breast cancer when the cancer isn’t sensitive to hormone therapy or when the cancer is life-threatening because it has spread so widely or progressed rapidly. Multiple chemotherapy options are available.

Single-agent vs. combination

Chemotherapy refers to a group of drugs that, when ingested or given intravenously, are toxic to cancer cells. Chemotherapy treatment may consist of taking just one drug (single-agent chemotherapy) or a combination of drugs (combination chemotherapy). Combination chemotherapy uses multiple drugs, with each attacking the cancer in a different way. The medications have different side effects, and the combinations are devised to try to increase destruction of tumor cells and minimize side effects.

Doctors have long debated the merits of using individual chemotherapy agents among women with metastatic breast cancer versus combining two to four agents into a combination chemotherapy regimen. This debate still continues, particularly as new information becomes available from clinical trials.

In general, combination chemotherapy, when compared with single-agent chemotherapy, has a higher chance of causing the cancer to shrink and remain smaller for a longer period of time. But combination chemotherapy also tends to produce more side effects.

A fair amount of evidence also suggests that using medications sequentially — that is, using one drug until it stops working and then using another one — leads to a similar length of survival and fewer side effects, when compared with combination chemotherapy.

It’s generally agreed that women with rapidly progressing, life-threatening disease should be treated with combination chemotherapy, assuming that they’re otherwise healthy enough to withstand the side effects of the drugs. Among women with breast cancer that’s not as aggressive, many doctors prefer single-agent chemotherapy.

In one study which addressed the question of single-agent chemotherapy versus combination chemotherapy, women participating in the trial received either doxorubicin alone, paclitaxel (Onxol) alone, or a combination of the two drugs. The trial found that no one treatment approach was superior to the other.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Chemotherapy drugs are often given in combination in order to fight cancer cells in different ways. Some combinations used for metastatic breast cancer include:

*CAF and FAC differ by dose and frequency.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Drug options

An array of chemotherapy drugs may be used to treat metastatic breast cancer. The drugs are grouped into categories based on the mechanism by which they work. Some factors that you and your doctor may consider in deciding which drugs to use include:

One of the chemotherapy medications for metastatic breast cancer is called capecitabine. This medication is similar to fluorouracil, one of the older chemotherapy drugs. Unlike many chemotherapy medications, which are given intravenously, capecitabine is given in the form of a pill. It’s often used as the first line of treatment for women with metastatic breast cancer.

There are also multiple combination chemotherapy regimens that your doctor may consider when determining your treatment. You may start off with a well-established combination regimen, which usually has a good balance between potency and side effects. If this doesn’t work, your doctor may suggest other combinations.

To learn more about chemotherapy medications, see Chapter 11.

Chemotherapy holidays

Once a woman begins chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer, a question that often arises is how long she should continue to take chemotherapy. Studies involving older chemotherapy drugs suggested the longer the better — the longer chemotherapy was used the longer the cancer stayed under control. Such studies have not been done with newer chemotherapy drugs.

For a woman who is tolerating chemotherapy well, it’s reasonable to continue taking the medication as long as it appears to be providing a benefit. If you’re having difficulties with side effects from the drugs, your doctor may suggest a chemotherapy holiday — a break from the medication that allows you time to feel better and more fully engage in day-to-day activities. Women with HER2-positive cancers may want to continue their HER2 medications while on a chemotherapy holiday.

HER2 medications

About 20 to 25 percent of women with breast cancer have cancer cells that overproduce a protein called HER2. This protein is normally produced by a gene that regulates cell growth. Certain breast cancers overproduce the HER2 protein. As a result, cells become overstimulated, aiding in the development and growth of a tumor.

Women whose breast cancers are characterized by an overproduction of the HER2 protein are referred to as HER2 positive. For more information on HER2, see Chapter 11.

Herceptin

A drug called trastuzumab (Herceptin) — a type of drug known as a monoclonal antibody — was developed to fight HER2-positive cancers. The drug works by attaching to HER2 receptors on cancer cells, blocking the action of the receptors. This inhibits the multiplication of HER2-positive cancer cells and, in some cases, is able to shrink the tumor.

Studies show additional benefits when trastuzumab is combined with chemotherapy. In more than half of cases, the drug combination causes tumor shrinkage. One study found that in comparison to women taking chemotherapy alone, those taking trastuzumab and chemotherapy:

Based on this evidence, trastuzumab has become an important part of treatment for women with advanced HER2-positive cancers.

If your tumor is HER2 positive and you’re about to start chemotherapy, your doctor likely will recommend that you take trastuzumab. Among women who also have estrogen receptor positive cancer, it’s not clear if trastuzumab should be given at the same time as hormone therapy, considering that hormone therapy may work for a considerable period of time.

While it’s true that combining hormone therapy with trastuzumab will shrink tumors for a longer period of time, there’s no proof that the combination approach will cause women to live longer than if they take the medications one following the other (sequentially).

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

In general, medications aimed at halting cancer progression are stopped when the disease continues to progress despite use of the drugs. But whether to discontinue trastuzumab (Herceptin) in women who are HER2 positive was unclear and for several years a subject of debate.

In women whose tumors continue to grow while receiving trastuzumab alone, doctors usually continue the medication but add to it a chemotherapy regimen. That’s because evidence indicates that chemotherapy combined with trastuzumab works better than chemotherapy alone.

More recent evidence indicates it’s also best to continue anti-HER2 therapy in women whose cancer continues to progress while receiving a combination of trastuzumab and chemotherapy. This may be done by combining trastuzumab with a different medication aimed at slowing progression of the disease, or by replacing trastuzumab with another medication that targets HER2 receptors, such as the medication lapatinib (Tykerb).

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Other HER2 medications

Other medications have also been developed that attack HER2 receptors. One of them is lapatinib (Tykerb). This medication is generally given when trastuzumab is no longer effective. At least one study suggests that when lapatinib is combined with chemotherapy it can halt cancer progression in women with metastatic breast cancer for a longer period of time than if the chemotherapy was taken alone.

Another HER2 medication that appears to be of some benefit and is undergoing clinical trials is the drug pertuzumab. In addition, researchers are examining if combining HER2 medications — such as taking trastuzumab and lapatinib together — is more effective than receiving one drug at a time.

Medications that prevent blood vessel growth

For cancers to grow and spread, they need blood vessels to supply them with nutrients and oxygen. Many cancerous tumors send out messages to surrounding tissue cells that encourage new blood vessel growth.

Medications have been developed that aim to stop cancer growth by preventing the growth of blood vessels to tumors. The most common is a drug called bevacizumab (Avastin). It received temporary Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval after early studies found it effective in shrinking tumors and halting cancer spread when combined with chemotherapy. Recently, though, the FDA revoked its approval of bevacizumab because of potentially serious side effects, including blood pressure problems and some trouble with bleeding and blood clotting. What the future holds in store for this medication is uncertain.

Other drugs that also inhibit blood vessel growth to tumors are under study and may be available in the future.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

As you try to make some decisions about using various drug therapies for treating metastatic breast cancer, it may be helpful to try to address the following questions:

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

New therapies

New knowledge about the underlying drivers of breast cancer — molecular pathways that allow cancer to start and keep going — has spurred new ideas for drug treatment. Instead of standard chemotherapy, drug manufacturers today are focused on so-called “targeted therapies.”

Cancer biology and Drug therapy show illustrations of a cell and its inner workings. The pathways shown in the illustrations are the targets of many new medications. To stop cancer growth, researchers are developing medications that act on:

These new medications use a variety of mechanisms to reach their pathways of interest, as is shown in the diagram How new cancer drugs work.

As progress in targeted therapies proceeds, there’s also interest in testing the medications in women with metastatic cancer to see if a particular drug might be effective. This kind of approach is generally done within a clinical trial. Be sure to ask your doctor if such an approach might be right for you.

![]()

QUESTION & ANSWER

Q: Are bone marrow transplants ever used to treat advanced breast cancer?

A: In the 1980s and 1990s, there was a lot of enthusiasm about the use of high-dose chemotherapy combined with bone marrow transplantation as treatment for women with breast cancer. The treatment was based on the idea that if some chemotherapy is good, then more should be better. Randomized clinical trials were set up, and women with metastatic breast cancer were randomly assigned to receive either standard chemotherapy or standard chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy with bone marrow transplantation. The results of these trials didn’t suggest any survival benefit in using high-dose chemotherapy with bone marrow transplantation, and as a result, enthusiasm for the treatment has waned considerably.

Once you begin treatment, your doctor will frequently monitor the status of your cancer by taking note of how you’re feeling, and the results of physical exams and periodic tests.

The most important of these is probably the medical history, which includes how you’ve felt since your last appointment and any new signs or symptoms you’ve noticed. Many times this provides the best information for your doctor to determine the effectiveness of treatment. A physical examination is probably the next most important determinant of how you’re doing. Various tests can also shed light on how your cancer is responding to treatment. These may include various blood tests and imaging procedures.

After completing his or her assessment, your doctor should be able to place your cancer status into one of three categories:

This last category can be subdivided even further:

In addition to monitoring your tumor status, your doctor will also look at how you’re tolerating the treatment and its side effects. Based on all of this information, you and your doctor can decide whether to continue your treatment. If you decide to stop it, the two of you then need to decide whether to try another form of treatment, and what that treatment should be.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

This chapter discusses the benefits and the risks of treatments for metastatic breast cancer. All this information has become available because of women who have participated in clinical trials. For some of the treatments you may be considering, there may be a clinical trial in which you can participate.

These trials, as a rule, are safe and they provide access to the newest ideas and approaches. They’re the best way to continue to identify new treatment options for women with metastatic breast cancer.

You can find out about specific clinical trials by asking your doctor or a member of your health care team or by visiting the National Cancer Institute’s website (see Additional Resources). For general information on clinical trials, see Chapter 2.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Depending on where a cancer has spread and what symptoms it may be causing, a number of treatments may be directed toward specific sites of your body, as opposed to the whole-body (systemic) treatment approaches already described.

Bone metastases

A group of medications (bisphosphonates) used to treat osteoporosis, a disease that causes bones to become weak and prone to fracture, also is used to treat women with metastatic breast cancer to their bones.

In one study, participants with breast cancer metastasis to bone were randomly assigned to receive a bisphosphonate or an inactive substance (placebo) in addition to their standard cancer treatment. Women receiving the bisphosphonate were less likely to develop subsequent bone fractures or to need radiation therapy to relieve bone pain. Based on this evidence, bisphosphonates are now commonly used in women with metastatic breast cancer in their bones.

In this study, women were given doses of bisphosphonates every month. Other studies are evaluating whether it’s best to receive the therapy once a month or once every three months. The results of these studies should be available in the near future.

Because bisphosphonates can cause kidney damage and can lower blood calcium levels, your doctor will likely monitor your kidney function during the course of treatment.

Another side effect of bisphosphonates is a condition called osteonecrosis of the jaw. Osteo means “bone” and necrosis means “the death of tissue.” Jawbone tissues die, leading to a painful lesion which can erode through the gums. The chance of this happening is higher in people with poor dental health or who have been on high doses of bisphosphonates for a long time. Because of this, before prescribing bisphosphonate therapy, your doctor will want to make sure your dental health is as good as it can be.

How long to use bisphosphonates is unclear. There’s some evidence people who are on bisphosphonates for a long period of time can actually develop brittle bones that fracture more easily.

Until better data are available, many doctors are now giving less frequent doses of the medication to women who have been on the therapy for a year or more. Newer drugs that act similarly to bisphosphonates also are being studied.

Pleural effusions

At times, cancer can develop in the pleural lining of the lungs, leading to the buildup of fluid around the lungs (pleural effusion). This may require removal of the fluid by draining it with a needle or by a more extensive process in which the fluid is removed either through a chest tube or a surgical procedure. Your doctor may then insert a chemical irritant into the space between the chest wall and lungs (pleural space) to create scar tissue and close up the space. This is done to decrease the chance that the fluid buildup will recur.

Another method for treating the fluid buildup is a procedure in which a catheter is inserted into the pleural space. The catheter contains a mechanism that allows it to be opened and closed, so fluid can be drained as needed.

Central nervous system metastases

If metastatic cancer develops in the brain or around the spinal cord, steroid medications are generally used to try to decrease the swelling and any resulting pain or neurological problems. Sometimes a neuro-surgeon may be called upon to try to remove some of the cancer. More often, however, radiation therapy is used to treat the cancer.

Sometimes, radiation is given to the whole brain to treat not only visible cancer but also cancer that may be too small to be seen. This can lead to side effects that may show up months to years later.

Another approach is to treat localized areas of the brain with what’s known as radiosurgery, or Gamma Knife treatment. It allows for areas where cancer is present to receive high-dose radiation treatment, without causing as much toxicity to the rest of the brain. Sometimes, the two — localized brain radiation and whole-brain radiation — are performed together.

These new treatment approaches, combined with earlier diagnosis of cancer spread with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have improved the prognosis for women with breast cancer whose cancer has spread to the brain.

Unfortunately, there are no guarantees that any particular treatment will work. When there’s evidence that the disease is progressing despite treatment, it’s a reasonable choice to reanalyze what your next step might be — similar to what you and your doctor did when you first learned you had metastatic breast cancer and were deciding on treatment.

With metastatic breast cancer, the value of each subsequent treatment tends to decrease. For example, in a woman who starts off with chemotherapy, the initial response rate might be around 50 to 70 percent, and the benefits may last for an average of 10 to 12 months. If the disease progresses, a second chemotherapy regimen might have only a 30 to 35 percent response rate, with an average response duration of just four to six months.

In addition, studies suggest that some people who receive less chemotherapy in their last weeks of life actually live longer than do those who receive more chemotherapy. It’s possible that as the cancer becomes more resistant to chemotherapy and the body becomes less tolerant of its effects, chemotherapy can, in fact, shorten both the quality and duration of life.

There may come a time when it is appropriate for you to say no to further treatment. For some women and their doctors, this may seem like giving up. But this assumption is generally incorrect. If the treatment is more likely to cause troublesome side effects — and not prolong your length of life or improve your quality of life — declining treatment is a reasonable choice. This shouldn’t be construed as giving up.

At this point, the goals of your treatment change. The focus of treatment is no longer on controlling the cancer but, instead, on controlling your symptoms and making you as comfortable as possible. This is called supportive care. For additional information on making the transition to supportive care, see Chapter 23.

![]()

3 Stories of Advanced Breast Cancer

This book includes many personal stories of women who have survived cancer, who are undergoing treatment or who have taken steps in hopes of preventing cancer. The women discuss why they made the decisions they did and, in many cases, how well they’ve done.

Unfortunately, though, not all women do well with their cancers. It’s important that we tell you not just the good-news stories, but also the ones that didn’t have such happy endings.

The pages that follow contain the stories of three women with advanced breast cancer. The first story is of a young woman who died prematurely of a very aggressive cancer. It needs to be noted that this story does not depict a typical case. Rather, it represents one end of the spectrum of metastatic breast cancer. In addition, it illustrates the fortitude of this young woman as she dealt with her disease. If you don’t think that you’re ready to read this story now, skip over it and consider coming back to it later.

The second story is a hypothetical one that combines parts of several actual cases. The story describes a more typical outcome for a woman diagnosed with recurrent breast cancer. It tells of a woman who does eventually die of her disease, but only after living with it for a relatively lengthy period. We’ll call the patient Jane.

The third story is of a woman who amazed her doctors for almost 50 years before she died of breast cancer.

Carol’s Story

At the age of 31, Carol was diagnosed with cancer in her left breast. The diagnosis came just a few weeks after she noticed a lump in the breast. Carol decided to have a lumpectomy, and her surgeon removed the lymph nodes under her left arm. The tumor was 2.5 centimeters (about an inch) in diameter — not particularly large — and all the lymph nodes tested negative for cancer. The tumor was also estrogen receptor positive and HER2 receptor negative. Based on the characteristics of her tumor and the laboratory results, estimates were that with just surgery alone, Carol had a 75 percent chance of living disease-free for at least 10 years.

At the time of Carol’s diagnosis, for a young woman with a tumor like hers, it was standard practice to recommend chemotherapy after surgery. Carol agreed with the treatment and received the medications doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. With chemotherapy, Carol’s chances of living disease-free for another 10 years increased to an estimated 80 percent.

After completing treatment with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, Carol discussed with her doctor the potential benefit of receiving additional chemotherapy with a medication called paclitaxel. Based on the information available at the time, it was estimated that paclitaxel might boost her 10-year survival chances by a couple more percentage points. Because Carol was young and had a young child, she wanted to be aggressive in treating her cancer. So Carol decided to undergo an additional two months of treatment with paclitaxel.

Upon completion of her chemotherapy, Carol met with her doctor to discuss radiation treatment to her left breast. During that visit, her doctor noticed a change in her left breast, which led to further tests. To everyone’s dismay, a computerized tomography (CT) scan revealed a large recurrent tumor in her left breast and cancer in some remaining lymph nodes under her left arm and her breastbone (sternum).

Her doctor recommended that Carol begin taking a hormone medication to turn off production of estrogen by her ovaries, as well as the medication tamoxifen. She also received radiation to her left chest wall to try to control the disease, knowing that there was a chance the radiation wouldn’t be successful, based on the aggressiveness of her cancer.

During a visit to her doctor a few months later, Carol had more fullness in her left upper breast region. A CT scan showed enlarging tumor masses in the breast and lymph node areas, in addition to spots in her liver, consistent with the spread of breast cancer to the liver.

At this juncture, Carol had to make some tough decisions regarding future treatment. Knowing that there wasn’t a chance of curing the cancer, and that the chance of chemotherapy shrinking the cancer was quite small, Carol, with input from her medical team and her husband, decided to try another chemotherapy medication.

Within a month, however, it was clear that not only was the cancer in her liver growing, but it had also spread to her spine, where it was causing considerable pain. To help control the pain, Carol received a course of radiation therapy to her spine. Over the next few weeks, she received even more radiation therapy to new painful sites in her spine, and she had a mastectomy because the tumor in her breast continued to grow and was causing considerable pain. After the mastectomy, Carol decided to try yet another chemotherapy drug, but it was stopped within two weeks because the cancer continued to grow and the drug was causing side effects that only added to her discomfort.

Carol continued to receive supportive care from her health care team to ensure that she was as comfortable as she could be. A little more than a year from when she was diagnosed with cancer, Carol died at home with her extended family present. Despite the relentlessly aggressive course of her disease, Carol lived her life as fully as was feasible. Although they did plan for her likely death, up to the very end, Carol and her husband never gave up hope.

Before her death, Carol began writing poetry as a way to cope with her illness. Following is one of her poems:

I had a dream

I dreamed the other night

I married the man I love so

For better, for worse, in sickness, in health

We live, we love, and we grow

I dreamed the other night

A beautiful boy was born

Thanks, praise, adoring him so

We live, we love, and we grow

I dreamed the other night

A cancer crept within

Faith, prayer, strength, hope

We live, we love, and we grow

I dreamed the other night

I was a survivor that had made it through

For better, for worse, in sickness, in health

We lived, we loved, and we grew

Carol Alcalá-Samaniego

Jane’s Story

Jane was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 58. On a mammogram, doctors noticed abnormal calcifications in one of her breasts. A biopsy revealed invasive ductal cancer. Imaging tests didn’t find any evidence of cancer elsewhere in her body, and Jane was otherwise healthy. After discussing potential treatment options with her doctor, Jane decided to have a lumpectomy, to be followed by radiation therapy.

During her surgery, Jane also had a sentinel node biopsy to check for cancer spread to nearby underarm (axillary) lymph nodes. The test revealed cancer cells in the sentinel lymph node. In light of this finding, other lymph nodes under Jane’s arm were removed.

The pathology report following her surgery indicated that Jane had a tumor in her breast that was 2.5 centimeters (about an inch) in diameter and that two of 18 lymph nodes from under her arm contained cancer cells. Jane’s tumor was also found to be estrogen and progesterone receptor positive and HER2 negative.

After her surgery, Jane met with her oncologist who estimated that with surgery and radiation alone, she had about a 50 percent chance of living without a cancer recurrence for the next 10 years. With the addition of chemotherapy and tamoxifen to her treatment regimen, that number increased to 63 percent. Jane chose to have chemotherapy and was given four cycles of the medications doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. After chemotherapy, she began taking tamoxifen and also received radiation therapy to her breast. She took tamoxifen for five years.

Jane continued to do well for another two years, when she developed back pain. A bone scan revealed metastatic breast cancer in her bones. Jane received radiation therapy to a painful area in her lower back where the cancer had spread. She also started taking the hormone medication anastrozole.

The radiation therapy helped relieve Jane’s pain, and for 14 months anastrozole controlled the spread of the cancer. Eventually, Jane developed some shortness of breath caused by fluid around one of her lungs. The fluid was drained and found to contain cancer cells. A surgical procedure was performed to help keep the fluid from re-accumulating. The anastrozole was stopped, and Jane was given another hormone medication. Six months later she developed some pain in her right upper abdomen, and tests indicated that the cancer had spread to her liver.

At this point, Jane and her doctor decided to stop hormone therapy and switch to chemotherapy. The chemotherapy initially shrank the tumors in her liver, but eight months later the cancer began to grow again. She switched to a different chemotherapy medication, which had the same results. The tumors initially regressed, but started to grow again eight months later. A couple more chemotherapy medications were tried over the next three months, but her cancer didn’t respond well to them.

Jane discussed the pros and cons of additional treatment with her doctor, and it was clear to both of them, and to her family, that the risk of serious side effects from the medications was greater than any potential benefit they might bring. Jane decided to stop all efforts to control the cancer, and her medical team concentrated on making sure that Jane was as comfortable as possible. Jane received hospice care, and five months later she died in her home with her family present.

Although Jane did eventually die of her breast cancer, she lived for more than 10 years after her initial diagnosis. And, for many of those years, she led a full life, keeping the disease from interfering with her life as much as was possible.

Margaret’s Story

Margaret Gilseth at home in her den, where she kept busy writing and communicating with family and friends.

To say that Margaret Gilseth lived with breast cancer most of her life is true. Margaret first noticed a lump in her breast when she was 39 years old. That was in 1957. Margaret had a mastectomy to remove her left breast, which was standard procedure at the time. Two years later, a small growth appeared on her incision scar. It turns out, it would be the first of many such tumors. Initially, the tumors were limited to her left chest wall, but eventually they began to spread across her chest wall and developed in her right breast as well.

Margaret handled each of the recurrences as she did her initial diagnosis. “I took them one at a time, and was glad to get rid of them. And then I went on living each time. I think you make use of each day.”

“Getting rid” of her tumors required many major and minor surgeries and radiation therapy. She had more than 25 separate surgical procedures, which removed more than 65 tumor nodules.

To keep new tumors from developing, or at least slow their growth, Margaret received multiple anti-cancer hormone therapies. She did this on and off for well over 20 years. When the effects of one medication began to wear off — signaled by the appearance of new growths — her hormone therapy was changed.

In addition to her strong faith, one of Margaret’s biggest allies in her lifelong battle with cancer was a pen and paper, which eventually gave way to a computer.

An English teacher for 25 years, Margaret enjoyed writing and she always kept a journal. Her journal helped her face, and then let go of, her worries and fears. Writing became her therapy. “I always tell people if they have something bothering them — anxieties that persist — there’s nothing better than writing.”

After her retirement, with more time on her hands, Margaret’s writing took on a broader scope. She wrote a novel about the lives of several generations of a Norwegian immigrant family, based, in part, on her own family’s experiences. Additional books and collections of poetry followed. Eventually, she wrote a book about her personal battle with breast cancer, called Silver Linings.

When she wasn’t writing, Margaret found other ways to keep busy. She volunteered at the local nursing home, read to children in the Head Start program and taught Norwegian in community education classes. She and her husband, Walter, traveled when they could, often as part of a volunteer organization. For Margaret, volunteer work was another part of her therapy, another way of coping and carrying on. ”I think taking an interest in other people makes a lot of difference. If you just go around thinking about yourself, it can cause you problems.”

Over the years, whenever Margaret was facing another surgery or a change in treatment — times when she wondered if “this was the one,” the one recurrence that she wouldn’t be able to overcome — her son Steve would offer her comfort by telling her in his lighthearted manner that she was going to live to a ripe, old age. It turns out, Steve was right.

Margaret continued to live a full life until she fell on some ice while out walking and broke her hip. After that incident, her breast cancer seemed to become more aggressive. She tried chemotherapy for a short period, but she didn’t like it. Almost 50 years after her breast cancer was diagnosed, Margaret died at the age of 88.

So, why did Margaret do so well despite her breast cancer that kept recurring? The oncologist who cared for Margaret the last two decades of her life — Margaret having outlived the 30-year career of her previous doctor — readily admits that he doesn’t know. Under the microscope, Margaret’s cancer looked like a routine type of breast cancer. Why it acted so differently from 99+ percent of other such cancers is a real mystery. Hopefully, it’s a mystery that can one day be solved to help doctors better understand cancer and better help patients.

Margaret’s story is a great reminder to women with cancer and their doctors to never say never, and never say always.

![]()