![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

You might wonder why ovarian cancer is included in this book. The reason is that breast cancer survivors have an increased risk of ovarian cancer. In addition, women from breast cancer families often have an increased risk of ovarian cancer. In this chapter, we will describe what ovarian cancer is, how common it is, the possibility of screening for it, and some basic information about its staging, treatment and outcomes. Genetic testing for inherited mutations that increase your risk of both ovarian and breast cancers is mentioned in this chapter but discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 5.

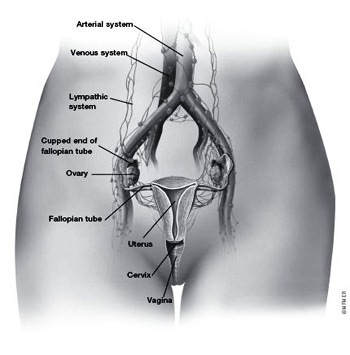

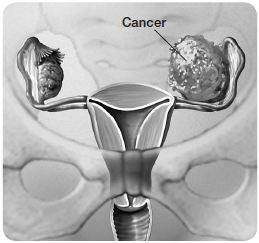

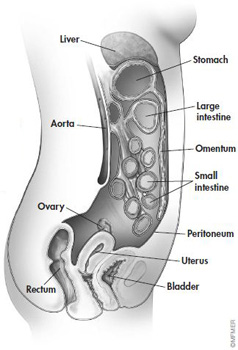

The ovaries are walnut-sized organs situated in the lower portion of your pelvis on each side of your uterus (see the illustration Gynecologic anatomy). During your menstrual cycle, your ovaries can change in size slightly. After menopause, they shrink to less than half their premenopausal size.

The ovaries produce eggs (ova). When a baby girl is born, her ovaries contain all the eggs that she’ll need throughout her life. Each month, beginning when a girl reaches puberty and continuing until menopause, the ovaries grow cyst-like structures called follicles. During ovulation, one follicle releases an egg into a fallopian tube, which connects the ovary to the uterus.

The ovaries are also the primary source of the female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone. These hormones influence the development and maintenance of feminine physical characteristics, such as breast development, body shape and body hair. Estrogen and progesterone also help regulate menstrual cycles and pregnancy. At menopause the ovaries stop producing eggs and these hormones.

Gynecologic anatomy

The ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and vagina make up the female reproductive system. Women have two ovaries, one on each side of the uterus. The ovaries — each about the size of a walnut — produce eggs (ova) as well as the hormones estrogen, progesterone and testosterone. Ovarian cancer is a type of cancer that begins in the ovaries or the thin layer of tissue covering them (epithelium). Cancer that develops in the ovaries may spread directly to other structures in the abdominal-pelvic cavity or through lymph channels (lymphatic system) or blood vessels (arterial and venous systems).

Like other cancers, ovarian cancer results from the loss of control of normal cell growth and regulation. Over time, abnormal cells in an ovary accumulate into a mass of tissue called a growth, or tumor. An ovarian tumor may be noncancerous (benign) or cancerous (malignant). Although benign tumors are made up of cells that are growing in excess numbers, they don’t spread (metastasize) to other body tissues. Malignant cells typically spread directly to nearby tissues in the abdominal-pelvic cavity or, less often, they may spread throughout your body by way of your blood vessels or lymphatic system.

While there are several types of cancer that can start in the ovaries, the most common — epithelial ovarian cancer — starts in the epithelial cells that cover the surface of the ovaries. In this book, all references to ovarian cancer are to epithelial ovarian cancer. This is the type that most often develops in breast cancer survivors and breast cancer families. Also, recent research has shown that cells from the cupped end of the fallopian tube that surrounds an ovary may become cancerous and spread immediately to an ovary, contributing to what we have called ovarian cancer. A closely related cancer called primary peritoneal cancer starts in the cells that line the abdominal cavity (see Primary Peritoneal Cancer).

Ovarian cancer causes more deaths than any other gynecologic cancer for two main reasons. First, in its early stages, ovarian cancer produces few — if any — signs or symptoms. And when symptoms do occur, they can easily be confused with those of other conditions. Second, as discussed later in this chapter, there isn’t yet an effective test to screen for ovarian cancer. For these reasons, more than two-thirds of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer have advanced-stage disease, meaning that it has at least spread within the abdomen.

However, there is some good news. There’s been major progress in unraveling the underlying biology and genetics of ovarian cancer. In addition, some cancers previously considered ovarian cancers actually appear to begin in the fallopian tube. This finding opens up new lines of research for both the causes of ovarian cancer and possible screening techniques to identify the disease earlier.

Another bright spot: Ovarian cancers tend to be responsive to chemotherapy —more so than many other types of cancer. With improvements in chemotherapy, there’s longer survival for women with ovarian cancer. In the 1970s, the average survival for women with ovarian cancer was about two years. But today, the average survival is closer to four years.

Also, important progress has been made in the ability to identify women at increased risk of ovarian cancer, especially those with hereditary risk. Research has also shown the effectiveness of surgery to prevent the development of ovarian cancer in women who are at high risk. See Chapter 6 for more information on cancer prevention options.

![]()

FASTFACT

Most common cancers among American women

| Type | Estimated number of new cases in 2012 |

| 1. Breast cancer (invasive only) | 226,870 |

| 2. Lung cancer | 109,690 |

| 3. Colorectal cancer | 70,040 |

| 4. Uterine (endometrial) cancer | 47,130 |

| 5. Thyroid cancer | 43,210 |

| 6. Melanoma | 32,000 |

| 7. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 31,970 |

| 8. Kidney cancer | 24,520 |

| 9. Ovarian cancer | 22,280 |

| 10. Pancreatic cancer | 21,830 |

Source: American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. Atlanta, Ga.: American Cancer Society, Inc.

The incidence of ovarian cancer — the number of new cases diagnosed each year — is low compared with breast cancer. There are about 22,000 new ovarian cancer diagnoses made in the United States each year. However, because symptoms are hard to identify and screening options are limited, the disease tends to have a high mortality rate. About 14,000 women in the U.S. die of the disease annually.

To put these figures in perspective, a woman at average risk has about a 1 in 70 (1.5 percent) chance of getting ovarian cancer during her lifetime if she lives to age 80. Compare that with the lifetime risk of breast cancer. About 1 in 8 women (or 12 percent) who live to age 80 will develop breast cancer at some point in their lives.

Ovarian cancer rates are the highest in Europe, the United States and Canada. The disease is more common in Jewish women of Ashkenazi descent (Eastern and Central European). In the United States, the incidence of ovarian cancer is slightly higher among white women than it is among black, Asian-American and Hispanic women.

The most significant risk factor for ovarian cancer is inheriting a mutation in breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or breast cancer gene 2 (BRCA2). These genes were originally identified in breast cancer families, but they’re also responsible for about 10 percent of ovarian cancers.

Women with a BRCA1 mutation have an estimated 39 percent chance of developing ovarian cancer by age 70. Women with a BRCA2 mutation have a 15 percent chance, compared with a 1.5 percent chance for the general population of women. Estimates vary from study to study based on the location of the particular mutation and the features of the women who participated in the studies.

Women of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry have a higher likelihood of being born with a BRCA mutation than does the general population of women. For women not of Ashkenazi descent, the likelihood of inheriting a BRCA mutation is 1 in 800. For women of Ashkenazi descent, it’s 1 in 40. For more information on the BRCA genes and genetic testing, see Chapter 5.

Another known genetic link involves an inherited syndrome called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Individuals in HNPCC families are at increased risk of cancers of the colon and rectum, uterine lining (endometrium), ovary, stomach, and small intestine. The risk of ovarian cancer associated with HNPCC is lower than that associated with BRCA mutations.

Besides these hereditary factors, age is the single greatest risk factor for ovarian cancer. This type of cancer is uncommon in women younger than age 40. In fact, the average age at diagnosis is 60. Other risk factors include never having had children, being of white race, menstruation before age 12, and late menopause. The average age at menopause in the U.S. is 51.

BRCA genes increase risk

| BRCA1 mutation carriers | BRCA2 mutation carriers | General population | |

| Risk of developing breast cancer by age 70 | 54% | 45% | 8-10% |

| Risk of developing ovarian cancer by age 70 | 39% | 16% | 1.5% |

Women who inherit BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations are at significantly higher risk of developing breast and ovarian cancers than are women in the general population.

Data from Sining Chen and Giovanni Parmigiani, Meta-Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Penetrance. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2007;25:1329.

Nothing can completely eliminate your risk of ovarian cancer. But, just as certain factors may increase your risk of this cancer, others may reduce it. If you’re concerned that you may be at high risk of ovarian cancer, talk to your doctor about your situation.

Birth control pills

Multiple studies show a protective benefit from use of birth control pills. Use of oral contraceptives for three or more years reduces a woman’s risk of ovarian cancer by as much as 50 percent, compared with women who have never used them. The protective effect continues for at least 10 to 15 years after you stop taking the pill.

Birth control pills work by suppressing hormones needed for ovulation. These hormones, as well as the inflammation within the ovaries caused by ovulation, may promote the development of cancerous cells. So suppressing ovulation and these hormones with birth control pills may help prevent ovarian cancer.

If you have a strong family history of breast cancer or a known BRCA mutation, talk with your doctor about whether it would be beneficial for you to take oral contraceptives. Along with the benefits, there are some risks. Some studies have suggested that birth control pills may slightly increase breast cancer risk in women at high risk of the disease.

Prophylactic oophorectomy

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Reduces ovarian cancer risk by at least 90 percent | Causes premature menopause and accompanying signs and symptoms |

| Reduces breast cancer risk up to 50 percent if done before menopause | Increases risk of osteoporosis |

| Causes loss of fertility in premenopausal women |

Removal of your ovaries

Women at very high risk of developing ovarian cancer may choose to have their ovaries removed to prevent the disease. This surgery, known as preventive (prophylactic) oophorectomy, is recommended primarily for women who’ve tested positive for a BRCA gene mutation or women who have a strong family history of breast and ovarian cancer, even if no genetic mutation has been identified. Studies indicate that prophylactic oophorectomy lowers ovarian cancer risk by at least 90 percent. The procedure also reduces the risk of breast cancer if the ovaries are removed before menopause.

Today, it’s common practice that both ovaries and the fallopian tubes are removed during the prophylactic surgery. This is technically known as a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The step of removing the fallopian tubes is important because tubal tissue appears to be the source of ovarian cancer in some women.

Prophylactic oophorectomy doesn’t completely eliminate cancer risk because despite having both the ovaries and fallopian tubes removed, some women still develop cancer in the cells lining the abdominal and pelvic cavity. This condition, called primary peritoneal carcinoma, behaves much like ovarian cancer (see the Primary Peritoneal Carcinoma).

The optimal age at which to have a prophylactic oophorectomy depends on whether you carry a BRCA mutation, the age at which other family members received a diagnosis of breast or ovarian cancer, and whether you have other health risks, such as the bone-thinning disease osteoporosis. Prophylactic oophorectomy isn’t an option for a younger woman who wants to maintain her fertility. Many experts recommend that high-risk women have the procedure after age 35 or when they feel that childbearing is complete for them. Women considering the procedure who haven’t completed childbearing may wish to talk with a fertility specialist about options for fertility preservation.

The main drawback of prophylactic oophorectomy is that it causes early menopause. Menopausal signs and symptoms include hot flashes, vaginal dryness, sleep disturbances and sexual problems. In addition, premature menopause has been linked to an increased risk of osteoporosis later in life.

The decision to have this preventive surgery is a major one. Before you make a final decision, discuss the pros and cons of the surgery in detail with your doctor. It’s key that you have an accurate understanding of your risk of ovarian cancer. Genetic testing may be an option to help define your risk (see Chapter 5).

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Closely related to epithelial ovarian cancer is a cancer called primary peritoneal carcinoma. It starts in cells that line the abdominal-pelvic cavity (peritoneum). These cells are very similar to those on the surface of the ovaries (epithelial cells). Under a microscope, peritoneal cancer looks just like epithelial ovarian cancer. It also acts in a manner similar to ovarian cancer and is treated the same way. Women with a family history of ovarian cancer who’ve had their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed still have some risk of developing primary peritoneal carcinoma.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

As Chapter 7 explains, screening involves looking for a disease before any signs or symptoms appear. Routine screening methods have been developed for several cancers, including mammograms for breast cancer, colonoscopy for colon cancer and the Pap test for cervical cancer. Screening helps save lives by detecting diseases in their early stages, when they’re most curable.

There has been extensive research done to test the possible value of screening for ovarian cancer. The bottom line is that doctors don’t routinely screen for ovarian cancer. Why not? In a nutshell: Researchers haven’t yet found a screening test that’s sensitive enough to detect ovarian cancer in its early stages and specific enough to distinguish ovarian cancer from other, noncancerous conditions. Developing a good screening test for ovarian cancer is hampered by two key factors:

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Most women have ovarian cysts at some point. Ovarian cysts are fluid-filled sacs in an ovary or on its surface. In women who are still menstruating, cysts typically occur as a normal and expected part of ovulation. Each release of an egg (ovulation) leaves behind a cyst about an inch in diameter. Normally, these cysts disappear without any treatment. In rare cases, though, they persist and grow larger. Some ovarian cancers can have cyst-like components, but most ovarian cysts aren’t cancerous and produce few or no symptoms. Unlike malignant tumors, ovarian cysts don’t invade neighboring tissue. However, if an ovarian cyst is large, it can cause pelvic discomfort. In some cases, it may interfere with the production of normal ovarian hormones, which could result in irregular vaginal bleeding. If a large cyst presses on your bladder, it may reduce your bladder’s capacity, causing you to urinate more frequently.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Ongoing efforts

There are two main tests that have been used for ovarian cancer screening. For both, a major flaw is that they produce too many false-positives. In addition, the tests miss many early cancers. Such results are called false-negatives.

CA 125

CA 125 is a blood test that measures the level of a circulating protein. This protein is produced by a variety of cells, including most ovarian cancer cells, especially in their later stages. Most healthy women have CA 125 levels below 35 units per milliliter of blood. In women with ovarian cancer, the level is often, but not always, elevated. However, measuring a woman’s CA 125 level isn’t a reliable screening tool for ovarian cancer, for a couple of reasons:

For a woman at high risk of ovarian cancer or for someone who’s experiencing signs or symptoms of the disease, a doctor may recommend a CA 125 test. But the test isn’t sensitive or specific enough to be used routinely for the general public.

Pelvic ultrasound

Another possible screening method is ultrasound, which uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of the inside of the body. Although pelvic ultrasound can help find an ovarian mass, it doesn’t accurately determine whether the mass is benign or malignant. This is a real problem because benign ovarian cysts are common. This limits the test’s effectiveness as a screening tool.

A transvaginal ultrasound can also be done, where an ultrasound probe (about the size of a tampon) is inserted into the vagina. This provides a better view of the ovaries.

Screening research

Recently, the National Cancer Institute studied the possible benefit of screening for ovarian cancer in a multi-institution study involving more than 78,000 women. These women were not known to be at increased risk of ovarian cancer (although about 15 percent of the women had some family history of breast or ovarian cancer). Half of the women were screened each year with CA 125 and ultrasound. The other half had typical medical care without screening. After about 12 years of follow-up, there was no difference in ovarian cancer deaths in the screened group versus the unscreened group. Additionally, there was evidence of harm from screening. Some women in the screened group received false-positive results, which resulted in many unnecessary surgeries.

At this time, a trial of transvaginal ultrasound and CA 125 testing involving more than 200,000 women is ongoing in Britain. The results of this study are expected in the near future.

Current research is focusing on the use of a panel of blood markers, including CA 125, in hopes of finding a better-performing test.

Recommendations

Because of the limitations of screening tests for ovarian cancer, the National Institutes of Health doesn’t recommend screening for ovarian cancer among women at average risk of the disease. Experts do recommend, though, that all women have a regular pelvic exam (see Pelvic Exam). Occasionally, an ovarian mass can be felt on such an examination.

Remember that regular pelvic exams are important to have. They’re needed not only for checking the ovaries but also for but for helping to discover cancer of the uterus, cervix or vagina at earlier an stage. It’s recommended that women begin having regular pelvic exams at approximately age 21. Women who’ve had their uterus removed but still have their ovaries should continue to have pelvic exams.

Screening women at high risk

Screening for ovarian cancer is recommended only for women who are at high risk of the disease. Women at high risk include those who carry breast cancer gene (BRCA) mutations or have a significant family history of ovarian or breast cancer, such as two or more family members with ovarian cancer. Even for this group, there’s no good evidence that screening saves lives, but it’s the best option available for finding ovarian cancer early, when the chance of a cure is greatest.

For women at high risk of ovarian cancer, doctors recommend a pelvic exam, a CA 125 blood test and ultrasound twice a year beginning at ages 30 to 35, or five to 10 years before the earliest diagnosis of ovarian cancer in the family — whichever comes first. Depending on the results of the tests and a woman’s individual circumstances, other tests may also be recommended.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

PELVIC EXAM

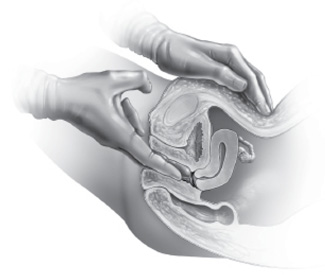

In a pelvic exam, you lie on an examining table with your knees bent and your heels in stirrups. After examining your external genitals, your doctor performs the following:

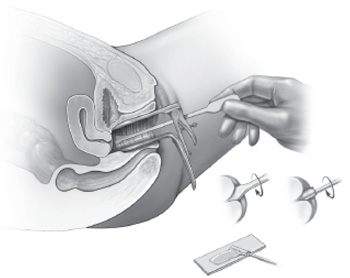

Pap test

To see the inner walls of your vagina and cervix, your doctor inserts an instrument called a speculum into the vagina. When in the open position, the speculum holds the vaginal walls apart so that the cervix can be seen. Your doctor then shines a light inside to look at the walls of the vagina for lesions, inflammation, abnormal discharge and anything else that’s unusual. During a Pap test — which is generally included in a pelvic exam — a sample of cells is taken from your cervix.

Vaginal exam

To check the condition of your uterus and ovaries, your doctor inserts one or two lubricated, gloved fingers into the vagina and presses down on your abdomen with the other hand. This allows your doctor to locate your uterus, ovaries and other organs, judge their size, and confirm that they’re in the proper position. While exploring the contours of these organs and the pelvis, your doctor feels for any lumps or changes that may signal a problem.

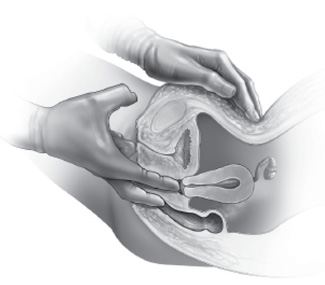

Rectovaginal exam

A rectovaginal exam checks the same organs as the vaginal exam, but from a different angle. For this exam, your doctor inserts one finger into your rectum while another remains in your vagina.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Most of the signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer relate to abdominal bloating or discomfort and other gastrointestinal disturbances. Signs and symptoms that women with ovarian cancer may experience include:

Less common symptoms include:

Nonspecific symptoms

Because the signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer are associated with many diseases and disorders, they’re said to be nonspecific. A woman or her doctor may assume that a more common condition is to blame. In fact, it’s not unusual for women with ovarian cancer to be diagnosed with another condition before finally learning they have cancer. The key seems to be having persistent or worsening signs and symptoms. With a digestive disorder, difficulties tend to come and go, or they occur in certain situations or after eating certain foods. With ovarian cancer, there’s typically little fluctuation — signs and symptoms are persistent and may gradually worsen.

Researchers have studied whether or not specific symptoms of ovarian cancer are reliable indicators that the disease is present. Unfortunately, there’s no one symptom or cluster of symptoms that can clearly point to ovarian cancer, such as the way that a dark, enlarging mole on the skin often signals skin cancer. The reality is that the ovaries are located deep in the pelvis where a problem may go undetected. And the signs and symptoms of the disease, such as abdominal bloating, generally don’t occur until after the disease has progressed.

Nevertheless, finding ovarian cancer as early as possible improves the oddsof successful treatment. If you’re experiencing persistent signs and symptoms, talk to your doctor. If you’ve already seen a doctor and received a diagnosis other than ovarian cancer, but you’re not getting relief from the treatment, schedule a follow-up visit with your doctor or get a second opinion.

In particular, don’t ignore persistent abdominal bloating or discomfort. Unusual bloating may indicate that ovarian cancer has spread to your upper abdomen, causing a buildup of fluid, a condition known as ascites. A pelvic examination, a CA 125 blood test, and an ultrasound exam or computerized tomography (CT) scan may help to rule out ovarian cancer as the cause of your symptoms.

Understand that your odds of developing both breast cancer and ovarian cancer are generally low. But because there are links, especially for women with a genetic susceptibility, it’s important to be vigilant. Get an accurate estimate of your risk. If a screening schedule is recommended by your doctor, stick to it. And be watchful for any warning signs.

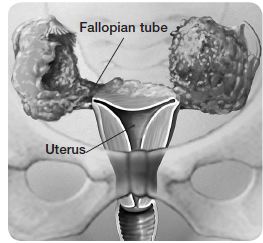

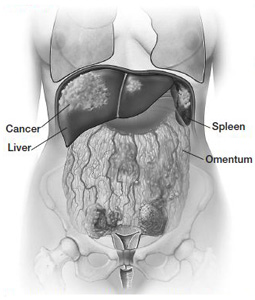

As the tumor grows on the surface of the ovary and becomes larger, it can shed cells like seeds directly into the abdominal-pelvic cavity. The shed cells can become implanted on the surrounding tissues and organs, such as the membrane that lines the abdominal-pelvic cavity (peritoneum), diaphragm, fallopian tubes, uterus, bladder, spleen and liver. The seeded cells then form new tumors in these sites. One of the most common sites for this spread is the fatty apron that covers the stomach and intestines (omentum). Seeding within the peritoneal cavity is the most common way ovarian cancer spreads.

As the disease spreads, it may cause fluid to collect in the abdominal cavity. The tumor nodules themselves may cause formation of excessive fluid. Or a collection of tumors may interfere with normal fluid drainage from the abdominal cavity. This abnormal fluid collection is known as ascites. In some women, several quarts of excess fluid may accumulate.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

OVARIAN CANCER STAGES

Stage I

Stage I cancer is confined to one or both ovaries.

Stage II

In stage II ovarian cancer, the cancer has spread from one or both ovaries to another organ in the pelvis. This may include the uterus, fallopian tubes, bladder, rectum or pelvic sidewalls.

Stage III

The cancer is in one or both ovaries and has spread beyond the pelvis to the surface of organs in the upper abdomen or to the lymph nodes.

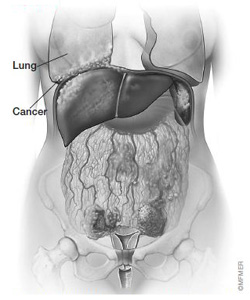

Stage IV

The cancer is found outside the abdominal-pelvic cavity, such as the area surrounding the lungs. The cancer may have spread to the interior of the liver or spleen.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Ovarian cancer spread

Ovarian cancer typically spreads when the tumor sheds cancerous (malignant) cells into the abdominal-pelvic cavity (seeding). These cells can then implant in the lining of the abdominal-pelvic cavity (peritoneum) or on the surface of other organs. Ovarian cancer may also spread to lymph nodes in the groin and pelvic area or to lymph nodes near the aorta. Less commonly, the cancer may travel to other parts of the body by way of the bloodstream.

Ovarian cancer is often diagnosed with a concerning ultrasound or CT scan and abdominal or pelvic surgery that’s based on worrisome symptoms. It’s very important that this surgery be performed by a gynecologic oncologist. A gynecologic oncologist is a surgeon with extensive training in the care and treatment of women with cancers of the reproductive tract.

The goal of surgery is to remove as much of the ovarian cancer as possible. Numerous studies have shown that the more effective this initial surgery, the better the outcome. If you’ve been told that you may have ovarian cancer or another type of gynecologic cancer, ask for a referral to a gynecologic oncologist.

Based on the results of your surgery and laboratory tests, your doctor or team of doctors gathers all of the information needed to classify the stage of your cancer — or how far the cancer has spread. Staging is a key factor in determining your prognosis and the treatment approaches that will be used. The stages of ovarian cancer are shown on above.

After surgery, you’ll likely receive combination chemotherapy with a platinum agent and a taxane. This is done to try to destroy cancer cells that may have remained. You might consider taking part in a clinical trial aimed at improving upon standard chemotherapy. Such trials are available in most centers that specialize in treating ovarian cancer.

![]()

Pat Goldman speaking at a meeting of the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance, the ovarian cancer awareness organization she helped establish.

Pat’s Story

Pat Goldman’s journey from survivor to activist began when she was 50 years old. On a November day, she saw a gynecologist because she had had some breakthrough spotting between her regular periods. The doctor did an endometrial biopsy, which found nothing, and an ultrasound, which revealed gallstones. The doctor told her that everything seemed to be fine and recommended regular checkups.

Early the following year, Pat got a call from a resident at the hospital where she had had the ultrasound. The resident had seen Pat’s ultrasound and suspected that she might have adenomyosis, a noncancerous (benign) thickening of the outside of the uterus. Pat was offered a free magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)scan as part of a study the resident was conducting on diagnosing adenomyosis.

Pat had the test, and the resident confirmed that she had the condition. “I was not the aggressive or informed consumer prior to my ovarian cancer diagnosis that I am today,” she reflects. “When the resident said that was what I had, I accepted it, never asked for a written report or copy of the pictures. With today’s knowledge, I certainly wouldn’t have accepted a phone diagnosis. I would have insisted on seeing her, the records and my gynecologist for a follow-up.”

Pat was told she may need a hysterectomy, but it wasn’t urgent. Over the next few months, she experienced more discomfort. “I’d roll over in bed and feel a twinge,” she recalls. “In the car, driving over bumps made my stomach hurt.” She went up two dress sizes and could no longer fit into her pants because she was so bloated.

By the following July, Pat was so uncomfortable that she could barely eat. She went back to her regular doctor and had another ultrasound. This time it showed a mass. She was referred to a gynecologic oncologist. Pat had surgery and was diagnosed with stage II ovarian cancer.

“I was devastated … because the only thing I knew was that Gilda Radner had it, and she died,” Pat says. “First you expect you’re going to die, then you have to figure out how to live.”

That wasn’t easy at first. After she finished her treatment, she kept expecting to have a recurrence, even though her surgeon told her that her relatively early stage at diagnosis improved her odds. Pat even postponed needed hernia surgery, figuring she was going to have another operation for cancer anyway, so she could take care of everything at once. Meanwhile, she began educating herself about ovarian cancer. She read a lot and looked for a support group. To her disappointment, she couldn’t find one. She told a friend involved with a breast cancer organization, who said, “You can’t do this alone. You’re going to have to find others.”

Gradually, Pat connected with other ovarian cancer survivors. She and a few other women in the Washington, D.C., area put a notice in The Washington Post announcing a meeting on ovarian cancer advocacy. To their surprise, 30 people showed up. They formed a group called the Ovarian Cancer Coalition of Greater Washington.

From there, Pat, representing the Washington group, and leaders from six other organizations established the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance (OCNA). From the beginning, OCNA’s foremost goal has been to raise awareness of ovarian cancer among the public, physicians and policymakers. As Pat’s experience demonstrates, ovarian cancer often goes undetected or misdiagnosed at an early stage. Alliance members have worked to promote earlier detection. As Pat and her colleagues continue to say today, “Until there’s a test, awareness is best.”

![]()