Pregnancy unleashes powerful forms of natural selection during the gestational phase of the mammalian life cycle. From the outset, however, I want to emphasize that not all expressions of mammalian pregnancy necessarily register adaptations shaped by natural selection. Thus there is no need to invoke adaptive justifications for all empirical facets of mammalian pregnancies. Indeed, chapter 5 noted that human pregnancy is often maladaptive (even lethal) to the participants. Here we take a broader evolutionary look at how natural selection both shapes and can be directed by mammalian-style viviparity. I first discuss natural selection’s likely influence (or sometimes lack thereof) on the evolution of three common gestational phenomena in mammals: (a) delayed implantation, which indeed demands an adaptive explanation; (b) sporadic polyembryony, which calls for no adaptive interpretation; and (c) dizygotic twinning, some biological elements of which require adaptive explication and others probably do not.

In some viviparous animals such as badgers (fig. 6.1), skunks, and wolverines, long intervals occur between fertilization and implantation of an embryo in the dam’s uterus. In other words, in species with delayed implantation (DI), the developmental “tabs” for syngamy and implantation have evolved to be further apart along the temporal axis of ontogeny (see fig. 1.4). Delayed implantation is merely one subcategory of embryonic diapause, which is defined broadly as any temporary arrest in embryonic development regardless of the mechanism. Delayed implantation can extend the duration of a pregnancy, sometimes dramatically.

FIGURE 6.1 American badger, Taxidea taxus (Mustelidae), a species that displays delayed implantation or embryonic diapause.

Factoid: Did you know? Although humans do not have delayed implantation, one artificial case of DI was described in Homo sapiens (Grinsted and Avery 1996). Following in vitro fertilization (IVF) and embryo transfer, a woman eventually gave birth, but her pregnancy in effect had begun after a 5-week delay following the original aspiration and IVF of her oocyte.

In nature, embryonic diapause is routine in almost 100 mammalian species representing 7 taxonomic orders (Renfree and Shaw 2000). Members of the family Mustelidae are of special interest because DI is highly developed in some mustelid lineages but absent in others (fig. 6.2). Delayed implantation is probably the ancestral condition in Mustelidae, in whom several independent evolutionary switches between DI and non-DI are required to explain the phylogenetic arrangement of embryonic diapause among extant species (Lindenfors et al. 2003; Thom et al. 2004).

FIGURE 6.2 Phylogenetic distribution of delayed implantation or embryonic diapause along an evolutionary tree for mammalian species in the family Mustelidae (from Avise 2006).

Factoid: Did you know? Mustelidae (from the Latin “mustela,” meaning “weasel”) is the largest and most diverse family of carnivorous mammals.

Given that DI evolved convergently on several independent occasions in mustelids and various other mammals, what (if any) is its adaptive significance? One compelling idea is that DI could enhance an animal’s genetic fitness whenever natural selection favors a decoupling of the times of mating and parturition. This should be the case, for example, in environments where harsh winters and pronounced seasonality give a fitness advantage to any female who can mate in one season (e.g., the autumn) but delay giving birth until a distant season (typically the spring or summer) that may better facilitate the survival of her progeny. In many bears (Ursidae), DI occurs on a different schedule, which eventuates in a midwinter birth as the mother delivers her offspring while she hibernates. Thus, a generalized version of the adaptationist hypothesis is that DI could be beneficial in any biological or ecological setting in which the optimal periods for mating and birthing differ. During evolution, natural selection then acts to adjust the duration of embryonic diapause in each species so as to achieve a suitable match between reproductive biology and environmental demands.

Polyembryony, or monozygotic twinning, is the production of two or more genetically identical offspring (clonemates) from a single zygote. Depending on the taxon, polyembryony may be either sporadic (occasional) or constitutive (when it occurs consistently in a species). Polyembryonic pregnancies in sexual organisms present an evolutionary enigma (Craig et al. 1995, 1997). Why would natural selection ever favor the production of polyembryos (as opposed to genetically diverse offspring) within a clutch? The famous evolutionary biologist George Williams (1975) analogized the mystery to the purchase of multiple lottery tickets with the same number even though no reason exists to prefer one number to another. In any polyembryonic pregnancy, the parents’ entire evolutionary wager for the litter is placed on one cloned genotype. Furthermore, because that genotype was generated sexually and differs from those of both parents, it is functionally untested and ecologically unproven. The evolutionary paradox is that polyembryony appears to lack the fitness advantages normally associated with either sexual or asexual reproduction. Standard sexual reproduction yields genetically diverse progeny, at least some of which might fare well in new ecological circumstances, and standard asexual reproduction (as in parthenogenesis) yields genetically uniform progeny whose multilocus genotype survived field testing in the parents. However, neither of these benefits would seem to occur with polyembryony. Thus, polyembryony at face value seems to combine some of sexuality’s worst elements (the deployment of newly recombined and untested genotypes) with clonality’s worst elements (lack of genetic heterogeneity within a brood).

As described in chapter 5, polyembryony in humans and many other vertebrates is rare and sporadic. Furthermore, because fraternal twins are usually more common than identical twins, there is no compelling evidence that sporadic polyembryony per se offers fitness advantages during a multibirth pregnancy. Thus, although polyembryony in humans is scientifically interesting and certainly has social and medical implications for affected families, it requires no special adaptive explanation, nor is it likely to have dramatic consequences for how natural selection operates in humans or other mammalian species in which the phenomenon is rare and sporadic. The same sentiment may not be true, however, for sexual species with constitutive polyembryony.

Armadillos in the genus Dasypus are the only vertebrates known to produce polyembryonic litters consistently and apparently exclusively. Six extant Dasypus species reside mostly in South America, but the nine-banded armadillo (fig. 6.3) reaches the southeastern United States. Each litter of D. novemcinctus typically consists of genetically identical quadruplets, although unusual instances of twins, triplets, quintuplets, and sextuplets have been reported (Newman 1913; Buchanan 1957; Galbreath 1985). In other species of the genus, standard litter sizes vary from two (D. kappleri) to four or eight (as in D. sabanicola, D. septemcinctus, and D. hybridus) to as many as twelve in rare instances. Several other armadillo genera also reside in the Dasypodidae. The closest relatives of Dasypus appear to be in Tolypeutes and Cabassous, two genera with species that usually produce only one offspring per pregnancy (Wetzel 1985). This taxonomic distribution of litter sizes indicates that constitutive polyembryony in the Dasypus lineage probably arose from an ancestral condition of one armadillo pup per litter.

Polyembryony in Dasypus armadillos has long been suspected from indirect evidence: littermates are invariably the same sex, and multiple embryos in each pregnancy are encased in a single chorionic membrane. Not until late in the 20th century, however, was the clonal identity of armadillo littermates confirmed directly from molecular markers (Prodöhl et al. 1996, 1998) and other genetic evidence (Billingham and Neaves 2005).

FIGURE 6.3 Nine-banded armadillo, Dasypus novemcinctus (Dasypodidae), a species that consistently gives birth to monozygotic quadruplets.

Factoid: Did you know? “Armadillo” is Spanish for “little armored one,” in reference to the animal’s leathery, plated shell, which serves as a protective covering.

How might constitutive polyembryony have arisen in armadillos, and should natural selection be invoked? One chain of argument about the evolution of obligate polyembryony proceeds as follows. In any sexual species, parents who produce nonclonemate offspring are hedging their bets by securing different genetic tickets in the reproductive sweepstakes. However, from each offspring’s selfish perspective, a heavy parental investment in one specific genotype (its own and that of its polyembryonically identical siblings) is the preferred option. Thus, in sexual species with extended parental care of young, parents and their progeny typically have inherent conflicts of interest over optimal parental investment tactics (Parker 1985; Stamps et al. 1978; Trivers 1974). By this reasoning, polyembryony might be interpreted as a special case in which the offspring’s preferred tactic in effect has won this evolutionary tug-of-war (Williams, 1975). The theoretical challenge then would be to elucidate particular ecological or ontogenetic conditions in which any genetic disposition for monozygotic twinning might invade the gene pool of a population otherwise engaged in sexual reproduction without polyembryony (Gleeson et al. 1994). On the other hand, the tug-of-war metaphor might be entirely inappropriate.

Musings about the optimal genetic composition of a brood have given rise to several other hypotheses about how constitutive polyembryony might evolve in particular species. With respect to life-history features, conventional speculation has been that polyembryony might be favored (all else being equal) in species in which early stages of embryonic development are lengthy, pregnant females face unpredictable resource availabilities, and/or when sperm cells are in limited supply, because a case can be made in each such biological circumstance that polyembryony might be of benefit to both a pregnant female and her offspring. However, it seems unlikely that these conditions apply with any special force to armadillos as compared to the other vertebrate groups that have not evolved constitutive polyembryony. Thus, some other evolutionary explanation for constitutive polyembryony may be required.

Another general line of speculation is that polyembryony tends to evolve when parents have less information about optimal clutch size than do their offspring (Craig et al. 1997). Whenever progeny are in the best position to judge the quality or quantity of environmental resources that will be available to them, polyembryony could be favored because it might allow such littermates to adjust the extent of their clonal proliferation accordingly. This hypothesis was motivated by the observed tendency in invertebrate animals for polyembryony to be associated with endoparasitism (see box 6.1). However, it seems doubtful that Dasypus biology uniquely qualifies armadillos to have evolved polyembryony in this manner.

BOX 6.1 Polyembryony in Endoparasitic Invertebrates

Polyembryony is a regular occurrence in invertebrate animals in several phyla (Craig et al. 1997; Avise 2008). Many of these species show internal brooding or various other pregnancy-like phenomena. For example, bryozoans in the order Cyclostomata are small colonial marine animals that produce up to hundreds of genetically identical progeny (known as gonozooids) in specialized brood chambers (Reed 1991; Ryland 1970). A very different form of polyembryonic “pregnancy” is displayed by a freshwater hydrozoan (Polypodium hydriforme; Cnidaria) that uses eggs of the fish species that it parasitizes as brooding chambers for its young.

Many other polyembryonic invertebrates are also endoparasites (Godfray 1994) (i.e., parasites that live within the body of a host organism). For example, a tiny wasp, Copidosoma floridanum (see the figure in this box), which parasitizes moths, provides another fascinating expression of both polyembryony and interspecific larval brooding (Strand 1989a, 1989b).

In this species, each female wasp oviposits one or two eggs in an egg of the host moth. After the host egg hatches and begins to develop into a caterpillar (a “heterospecific womb”), the wasp egg divides mitotically and produces hundreds or even thousands of polyembryos within the host (Grbic et al. 1998). A few of these clonemate wasps become soldiers that patrol inside the caterpillar’s body to prevent subsequent invasion by other parasitoids (Cruz 1981; Giron et al. 2004; Hughes 1989). Other members of the brood eventually kill the caterpillar by eating their way out of its body. The wasp larvae then pupate on the corpse’s skin. Copidosoma floridanum is just one of many polyembryonic parasitoid wasps, an invertebrate assemblage in which polyembryony has evolved convergently on multiple occasions (Craig et al. 1997).

Craig et al. (1997) interpreted the association between polyembryony and parasitism in many invertebrates as an evolutionary response to selection pressures related to a mother’s inability to predict her optimal brood size. In the case of Copidosoma floridanum, for example, each female who oviposits into a host’s egg would ideally “want to know” just how big the moth caterpillar (her progeny’s food source) will become so that she can properly adjust the number of fertilized eggs that she deposits. But such information is presumably unavailable to her. Furthermore, the moth egg offers little space for a female wasp to oviposit a multiegg clutch (Hardy 1995). Given these special circumstances, both the mother wasp and her progeny might benefit if proliferation within the brood is delayed until the caterpillar stage of the host, and polyembryony is the only available postoviposition mechanism for achieving this outcome. A further potential advantage of polyembryony in this biological setting is that competition among clonemates should be minimized and collaborative behaviors rewarded via the intense kin selection that can come into play within the tight ecological quarters of the host caterpillar.

Interestingly, an analogous argument can be made for the adaptive significance of polyembryony in armadillos if the “uterine constraint hypothesis” (see the text) is correct (Loughry et al. 1998). For the parasitoid wasps, a tiny moth egg is the resource bottleneck that later expands into a spacious caterpillar, whose food-rich body can support the development of many wasp polyembryos. For the armadillos, a tiny uterine implantation site is the resource bottleneck that later expands into a spacious womb that can house and nourish multiple clonal littermates. Thus, for wasps and armadillos alike, polyembryony circumvents a temporary restriction on brood size by capitalizing upon what soon becomes a richly expanded ecological setting (caterpillar or uterus, respectively) for further embryonic development.

A third general hypothesis for the evolution of polyembryony entertains the notion of nepotism (i.e., favoritism toward kin) (box 6.2). As applied to armadillos, a kin-selection hypothesis for polyembryony would require that littermates help one another to build dens, find food, detect predators, groom parasites, defeat competitors, or otherwise benefit from mutual aid. If so, any genes underlying polyembryony might have been favored by kin selection if pronounced cooperation among clonal littermates led to higher mean rates of survival and successful reproduction of clonal littermates than was true for nonclone littermates. Alas, this appealing evolutionary hypothesis also appears inadequate to account for polyembryony in armadillos. Genetic analyses in conjunction with field investigations have revealed that weaned armadillos in nature seldom remain together long after birth, and even when pups are found together, they appear not to display nepotistic behaviors (Loughry et al. 1998a, 1998b).

BOX 6.2 Inclusive Genetic Fitness and Kin Selection

In 1964, the famous evolutionary biologist William Hamilton formally introduced the important concept that an individual in any species can transmit copies of its genes to the next generation in two ways: directly (by producing offspring) or indirectly (by helping close relatives leave descendants). The former is personal genetic fitness, whereas the latter contributes to an individual’s inclusive genetic fitness. Hamilton demonstrated mathematically that any gene-encoding nepotistic behavior can in principle spread in a population if the cost that it imposes on an individual’s reproduction is more than offset by the enhanced transmission of copies of that gene to the nepotist’s relatives. Such kin selection should operate far more effectively on close relatives (who likely share copies of a specified gene) than on distant cousins (who likely do not). Clonemates (such as identical twins) are obviously the nearest of genetic kin. Thus, species that routinely display polyembryonic pregnancies might be especially prone to kin-selection pressures that favor the evolution of nepotistic behaviors.

Before Hamilton (1964), genetic fitness had been defined as an individual’s (or a genotype’s) average reproductive success in comparison to that of other individuals (or other genotypes) in the population. Inclusive fitness entails a broader view of genotypic transmission across the generations because it incorporates both the individual’s personal or classic fitness and the probability that the individual’s genotype is passed on by genetic relatives. These latter transmission probabilities in turn depend on how close the kin are. Concepts of inclusive fitness were advanced to explain the evolution of “self-sacrificial” behaviors, wherein any alleles for altruism may have spread in populations under the influences of kin selection. According to “Hamilton’s rule,” an allele will tend to increase in frequency if the cost C it entails (loss in personal fitness through self-sacrificial behavior) relative to the benefit B it receives via increased reproduction of kin is less than r (i.e., whenever C/B < r). Thus, in one proverbial example of “altruism,” individuals could improve their inclusive genetic fitness by sacrificing their own life for those of two full sibs, four half-sibs, or eight first cousins!

Although the twin topics of kin selection and inclusive fitness remain controversial in some evolutionary circles (Nowak et al., 2010; Nowak and Highfield, 2011), unquestionably they have added exciting new perspectives to traditional Darwinian reasoning.

An entirely different explanation of constitutive polyembryony in armadillos appears more plausible (Galbreath 1985). At the outset of her pregnancy, a female armadillo’s uterus is highly constricted and has only one implantation site. Only later does the womb enlarge and make room for additional offspring, who then arise polyembryonically. This situation contrasts with the physical setup in many other mammalian species, in which multiple implantation sites exist and more of the female’s uterus can thereby serve to initiate a multipup pregnancy. Thus, under the “uterine-constraint hypothesis” (Prodöhl et al. 1998; Loughry et al. 1998b), obligate polyembryony in armadillos might be a highly evolved strategy that has been maintained by natural selection because it ameliorates the severe limit on litter size otherwise imposed by the peculiar physical configuration of the maternal uterus. Thus, from the fitness perspectives of both mother and offspring, polyembryony in armadillos could be interpreted as “making the best of the available anatomical situation.”

Although the uterine-constraint hypothesis for constitutive polyembryony in armadillos remains speculative, it does illustrate how an enigmatic biological phenomenon might have an unanticipated adaptive explanation after all. However, even if the uterine-constraint hypothesis is true, it leaves unanswered the deeper question of why armadillos evolved a constricted uterus in the first place.

Marmosets and tamarins (fig. 6.4) are small arboreal primates that normally give birth to two or more fraternal (nonidentical) offspring per pregnancy. These species live in highly social groups and are atypical among primates in the degree to which one female in each troop monopolizes reproduction (Anzenberger 1992). Furthermore, adult and subadult nonbreeders (who typically are progeny from the breeding couple’s earlier litters) routinely help their parents rear additional offspring.

FIGURE 6.4 Golden lion tamarin, Leontopithecus rosalia (Callitrichidae), a primate that consistently gives birth to dizygotic twins.

Factoid: Did you know? Marmosets and tamarins (family Callitrichidae) are among the world’s smallest primates, and adults in some species reach only 5 inches in length (not counting the equally long tail).

Why would nonbreeding individuals forego personal reproduction to help others rear offspring? Most researchers interpret such “alloparental care” in any species as being potentially adaptive for the helpers for one or both of the following reasons. First, substantial but indirect genetic benefits might accrue to any caregiver who is the son or daughter of the breeders because some genes that the helper shares with its parents would be transmitted to new brothers and sisters. Thus, by becoming a helper, a genetically related caregiver might improve its “inclusive genetic fitness” via kin selection (box 6.2). Second, for related and unrelated caregivers alike, reproductive assistance could be self-serving if the helper learns valuable social or parenting skills that it might later utilize if it gets an opportunity to breed. Unfortunately, little empirical evidence exists either to support or refute such hypotheses for marmosets and tamarins in nature.

An astonishing discovery, based in part on molecular markers, is that each individual marmoset or tamarin is a genetic chimera (Benirschke et al. 1962): a creature whose somatic cells collectively are a mixture of distinct genotypes (Signer et al. 2000). This peculiar genetic outcome seems to be almost unique to marmosets and tamarins, where it happens routinely as follows. These primate twins start life as separate fertilized eggs (each with its own distinctive diploid genotype), but during the first month of pregnancy the embryos partially fuse inside their mother’s uterus, exchanging blood cells and some other body tissues. Although the fraternal twins become physically separated before birth, each member of a set of twins in effect is genetically partly itself and partly its brother or sister.

Discovery of this odd state of affairs prompted the development of a sophisticated mathematical argument for the evolution of alloparental care in these primates (Haig 1999b). The hypothesis hinges on the suspicion that by virtue of being a chimera, each tamarin is related more closely on average to its parents than to its own sex cells (sperm or eggs). If so, then one of the two sets of genes in each chimeric twin would, in effect, devalue the animal’s personal reproductive efforts in relation to any behavior directed toward helping its parents. Thus, genetic chimerism itself tips the scales toward the evolution of cooperative behavior in marmosets and tamarins by predisposing each chimeric animal to suppress personal reproduction in favor of helping its parents. As detailed by Haig (1999b), placental chimerism might also have several evolutionary implications for kin interactions within the womb, including how natural selection could promote both antagonistic and cooperative interactions between sibling embryos. Haig’s intriguing genetic hypothesis remains to be tested empirically, but it does highlight the broader evolutionary notion that the mammalian womb is a key biological arena wherein selective interactions between sibling genotypes (as well as between parental and offspring genotypes) are likely to transpire. These genetic hypotheses also highlight the point that natural selection and adaptation are not synonymous; natural selection is a relational process involving differential reproduction among genotypes, whereas adaptation is some absolute measure of how well an organism matches environmental demands. In the case of marmosets and tamarins, dizygotic twinning can clearly influence the way in which natural selection operates during (as well as before and after) a pregnancy, but the phenomenon itself need not be interpreted as an evolutionary adaptation. Instead, intrauterine chimerism might just be a coincidental biological condition (or perhaps a phylogenetic legacy) with selective consequences.

Pregnancy might seem to be the ultimate collaborative endeavor between individuals because (a) a mother and her fetus both have a vested personal interest in a successful outcome and (b) so too does the father. Indeed, all three participants (sire, dam, and fetus) in a pregnancy would seem to have a coincident mutuality of interest that progeny are born healthy after a productive incubation. On the other hand, each female mammal alone bears the physical burden of incubation and nursing, whereas the male may have little or no reproductive involvement beyond his original genetic contribution. Also, in nearly all sexual species each family member has a unique genotype, implying that a gene’s optimal tactic for self-perpetuation depends at least to some degree on which of the individuals house that gene and any of its copies. Furthermore, the selfish genetic interests of interacting organisms tend to be aligned only insofar as those individuals are related (Hamilton 1964; Mock and Parker 1997; Clutton-Brock 1991), and coefficients of genetic relatedness (r) between pairs of individuals in a nuclear family vary widely. For example, a mother and her offspring normally share half their genes (r = 0.5), as do full sibs in a multibirth litter; however, half-sib progeny share only one-quarter of their genes (r = 0.25), and a sire and dam typically are unrelated (r = 0.0).

For these and other reasons, each nuclear mammalian family is not simply a serene setting for harmonious interactions but can also be an evolutionary minefield of oft-competing genetic fitness interests, both inter- and intragenerational. Furthermore, many of these conflicts play out forcefully during each pregnancy (i.e. within the mammalian womb) (box 6.3). Of course, maternal-offspring relations entail many elements of cooperation as well as conflict; these two categories of interaction need not always be interpreted as mutually exclusive (Strassmann et al. 2011).

BOX 6.3 Trench Warfare at the Maternal-Fetal Interface

Haig (2010a) recently reviewed the history of scientific thought about physiological happenings at the anatomical boundary between a pregnant mother and a fetus. Before the 1890s, many physicians viewed implantation as basically a cooperative process, in which the mother’s placenta provided a spongy bed that welcomed and nourished the nascent embryo. Another metaphor conveying this peaceful sentiment was that the lining, or decidua, of the mother’s uterus acted like fertile soil that supported the growth of the embryo as the latter developed within the womb. However, embryological discoveries in the late 1890s soon changed such amicable metaphors to alternative descriptions of implantation as a hostile process in which the embryo was portrayed as a ruthless invader against which maternal defenses were deployed at the decidual interface.

Indeed, some biologists soon began to apply explicit battlefield imagery to the implantation process and to other maternal-fetal interactions during a pregnancy. For example, in describing the maternal-fetal placental boundary, Johnstone (1914, 258) wrote the following: “The border zone … is not a sharp line, for it is in truth the fighting line where the conflict between maternal cells and the invading trophoderm [the part of the blastocyst that attaches to the uterine wall] takes place, and it is strewn with such of the dead on both sides as have not already been carried off the field” (quoted in Haig 1993, 500). Similarly, Page (1939, 292) described the placenta as a “ruthless parasitic organ existing solely for the maintenance and protection of the fetus, perhaps too often to the disregard of the maternal organism” (also quoted in Haig, 1993, 516). Metaphors involving parasitic associations, trench warfare, and other battleground imagery were sometimes extended to other aspects of mammalian pregnancy as well. Such metaphors were motivated not by any philosophical or theoretical argument but were meant simply to summarize empirical observations made under the microscope about cellular happenings at the maternal-embryo interface. Another half-century would pass before an evolutionary rationale would be advanced that helped to make sense of the physiological, cellular, and biochemical turmoil between a mother and her fetus.

That breakthrough came in 1974, when evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers published a revolutionary manuscript titled “parent-offspring conflict.” In that work, Trivers extended Hamilton’s (1964) kin-selection logic by verbally and graphically formalizing the notion that conflict (rather than pure cooperation) is an inherent evolutionary feature of interactions between parents and their progeny in sexually reproducing species. Taking into account an offspring’s inclusive fitness (rather than solely the conventional perspective of a parent’s reproductive success), Trivers surmised that parents and their progeny should routinely disagree about the magnitude and duration of parental care, assuming that natural selection has shaped these actors’ behavioral proclivities. Furthermore, various expressions of this conflict are to be expected throughout the period of parental care, which in female mammals normally reaches its zenith during pregnancy (i.e., in the interval between implantation and parturition). (However, parental care in many mammals in effect begins even before conception [as in den-building species such as beavers], and it can extend well beyond birth and weaning, as in pack-hunting species such as wolves). Nevertheless, parturition marks an important biological transition because it represents essentially the last good opportunity for fetal genes to use biochemical and physiological mechanisms to manipulate maternal responses directly. Although genes in progeny may remain under selection to manipulate parents long after parturition, their modes of action then are likely to be behavioral as opposed to biochemical.

In the early 1970s, Robert Trivers (1972, 1974) introduced an evolutionary interpretation of parent-offspring conflict. Trivers’s basic insight was that sexually produced offspring are typically under selection to demand more resources from their mothers than the latter will have been selected to provide. Furthermore, the same argument applies to fathers, with the added stipulation that a male might be expected to resist an offspring’s demands even more strenuously than the mother, especially if he is uncertain about genetic paternity. When viewed in this evolutionary manner, mammalian pregnancy becomes a prime biological arena for intergenerational conflict over parental resources: each offspring is under selection to seek as many parental resources as possible, limited only by any negative effects on its inclusive fitness (see box 6.2) that such demands impose on copies of its genes carried by littermates or parents (all of whose reproductive successes might be diminished if they acquiesced fully to the focal offspring’s demands). Nearly all mammals display female pregnancy and female lactation, so many of these inherent parent-offspring conflicts boil down to disputes between a dam and her progeny. The net result of each such evolutionary “tug-of-war” (Moore and Haig 1991) between mother and child is some ontogenetic balance in which each offspring must settle for fewer maternal resources than it might ideally wish, and a mother surrenders more resources than she might otherwise prefer to offer. However, by evolutionary reckoning, any such maternal-fetal compromise during or after a pregnancy is less the result of a harmonious mutualism than it is an outcome of conflict mediation (see box 6.3). Indeed, if this were not true, mammalian pregnancy would probably have evolved to be less traumatic for the mother and less dangerous for her gestating embryo(s).

In his formulation of parent-offspring conflict, Trivers (1974) defined parental investment as any investment by the parent in an individual offspring that affords fitness benefits (B) to that offspring at a cost (C) to the parent’s ability to invest in other progeny. Thus, by definition, a fitness tradeoff attends any such parental expenditure. From a parent’s perspective, further investment in the focal offspring is favored if B > C; however, from an offspring’s perspective, further investment is favored when B > rC, where r is the chance that another sibling shares with the focal individual a copy of a randomly chosen gene. Thus, when r ≤ 0.5 (as is true for littermates in almost all sexual species), genes in each offspring are normally under selection to seek more resources from the pregnant parent than genes in the latter are under selection to supply.

Trivers (1974) applied his ideas mostly to postpartum parent-offspring conflict, but the theory similarly pertains to maternal-fetal interactions within the mammalian womb, as detailed in an important series of papers by David Haig (1996a, 1996b, 1996c, 1999a, 2004a, 2004b, 2007). In particular, Haig’s (1993) paper, titled “genetic conflicts in human pregnancy,” extended Trivers’s evolutionary reasoning by elaborating many physiological skirmishes that arise routinely during mammalian pregnancy. Consider, for example, fetal growth and nutrition. Early in each pregnancy, a mother stores lipids in preparation for later gestation and lactation, but her fat supplies have peaked and begun to decline by the end of the second trimester as fetal growth diminishes maternal reserves and stresses both mother and child, especially if the dam’s food intake becomes limited. Perhaps partly for this reason, each pregnant female appears to impose a physiological upper limit on how much nutrition she delivers to her progeny in utero. Maternal-fetal conflicts likewise arise and play out with respect to calcium metabolism (Haig 2004a), uteroplacental blood flow (Haig 2007), placental hormones (Haig 1996c), and a host of other metabolites and metabolic signals between mother and child (Wilkins and Haig 2003).

To describe the many maternal-fetal conflicts during a pregnancy, Neese and Williams (1994, 197) stated the situation as follows: “From the mother’s point of view, benefits given to the fetus help only half of her genes, so that her optimum donation to the fetus is lower than the amount that is optimal for the fetus. She is also vulnerable to injury or death from the birth of too large a baby. The fitness interests of the fetus and the mother are therefore not identical, and we can predict that the fetus will have mechanisms to manipulate the mother to provide more nutrition and that the mother will have mechanisms to resist this manipulation.” The authors then went on to suggest that serious medical problems commonly arise when the balance of power between mother and fetus becomes disrupted for any reason.

One example of a serious medical condition in many human pregnancies involves a substance known as human placental lactogen (hPL), which ties up maternal insulin such that maternal blood-glucose levels rise and the fetus thereby receives extra glucose (i.e., more nutrition). In response to this biochemical manipulation by the fetus, the mother in effect develops insulin resistance and becomes predisposed to secrete more insulin, which in turn stimulates the fetus to secrete more hPL (Neese and Williams 1994). If the mother also happens for any genetic or other reason to be deficient in her physiological capacity to produce insulin, the net result can be gestational diabetes and hyperglycemia (too much glucose in the blood), which, in the extreme, may be fatal to both mother and child. Although this latter outcome is clearly undesired by both parties, it can be interpreted as an unhappy evolutionary byproduct of the greedy behavior of an offspring in its hegemonic attempts to extract extra maternal resources, in this case using hormones as a means of waging physiological warfare while still in the womb.

Another example of maternal-fetal conflict involves preeclampsia (high blood pressure), a second major scourge in human pregnancy (Redman 1989; Haig 1993; Neese and Williams 1994). Preeclampsia begins in the early stages of a pregnancy when placental cells destroy uterine nerve fibers and muscles that otherwise adjust the blood flow from the mother to the placenta. The result is a cascade of physiological effects that may include a constriction of arteries in the mother, an increase in her blood pressure (hypertension), delivery of more blood to the placenta, and a greater transfer of nutrients to the fetus. Under an evolutionary interpretation, selfish conceptuses across the generations have experienced selection pressures that have promoted such mechanisms to garner maternal resources, even if by doing so they sometimes compromise their mother’s health and may even threaten her life.

Factoid: Did you know? Gestational diabetes occurs in about 4% of human pregnancies, meaning that approximately 135,000 pregnant women per year experience this condition in the United States alone.

Factoid: Did you know? Preeclampsia affects about 5% of human pregnancies and is a leading cause of perinatal mortality, preterm birth, and maternal morbidity (Aubuchon et al. 2011).

A third possible example of maternal-fetal conflict involves human chorionic gonadotropin (hGH), a hormone produced by the conceptus that enters the mother’s bloodstream and impels her body to retain (rather than abort) the fetus (Neese and Williams 1994). Without such fetal manipulation of maternal physiology, mothers otherwise seem to have evolved surveillance mechanisms to recognize and reject defective fetuses. Such maternal screening mechanisms make evolutionary sense because a female can increase her lifelong genetic fitness by detecting and aborting any defective conceptus early in a pregnancy (and then perhaps starting over), even if this comes at the increased risk of occasionally killing a normal embryo. By secreting high levels of hGH, the fetus in effect is trying to prove its good health to a mother who has evolved physiological mechanisms that make her suspicious of such biochemical manipulations by the embryo.

Sometimes maternal-fetal gamesmanship during evolution can play out in ways that are subtler or far less disastrous for a pregnancy than are gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, or spontaneous abortion. An interesting case in point is the common phenomenon of “morning sickness” or “pregnancy sickness,” wherein expectant mothers become easily nauseated and show strong aversions to or cravings for specific foods. One proximate explanation is that high levels of hGH contribute to this sensitivity, in which case morning sickness might be viewed as an unhappy evolutionary by-product of the genetic conflict between mother and embryo (Haig 1993; Forbes 2002). Another evolutionary interpretation is perhaps more conventional (Hook 1978): that mothers have evolved physiologies that confer sensitivities to any environmental contaminants that might compromise an otherwise successful pregnancy (Profet 1988, 1992; Sherman and Flaxman 2001). According to this view, morning sickness could be part of an adaptive response that discourages the ingestion of toxins and promotes the ingestion of healthy foods during a pregnancy. Under either explanation, pregnancy sickness is not an inexplicable pathological condition but a syndrome that emerged in response to selective pressures in the stressful biological environments in which humans evolved.

Factoid: Did you know? Pregnancy sickness in its most extreme forms (known as hyperemesis gravidarum) can be fatal due to electrolyte imbalances from persistent nausea and vomiting, which may extend well beyond the first trimester of a pregnancy.

Immunological rejection of an embryo by its mother is another potential source of parent-offspring conflict within the womb, especially in mammals with refined histocompatibility systems that otherwise recognize and attack foreign tissues (Medawar 1953). Because a sexually produced fetus differs genetically from both of its parents, why does the mother’s immune system not perceive the conceptus as alien and attempt to destroy it (as it would do for an invasive pathogen or a parasite)? The general answer is that viviparous mammals have evolved mechanisms that circumvent rejection responses during a pregnancy and thereby permit the dam to gestate “nonself” tissue. These physiological arrangements are not necessarily ideal from a health perspective, but they do constitute a workable accommodation between mother and fetus that normally permits the pair to survive the protracted intimate contact that mammalian pregnancy entails. The immunosuppressive mechanisms that operate during a pregnancy are especially remarkable because, throughout the entire evolutionary process by which they arose, both mother and fetus had to remain able to fend off infections by bona-fide parasites and pathogens. Thus, immunosuppression could not be accomplished simply by shutting down the immune systems of parent and child.

Instead, eutherian mammals appear to have evolved several other routes to fetal survival in the face of maternal immunosurveillance. Three of the primary physiological pathways are as follows: (a) fetal modification of the expression of transplantation antigens in the conceptus; (b) fetal alteration of the maternal immune system to its own advantage; and (c) placental limitations on the passage of effector molecules that otherwise might implement the immune response. All of these categories of immunological circumvention have been documented and illuminated to varying degrees in various mammals. However, the mechanistic details are complicated (box 6.4), and they also seem to vary considerably among species, for reasons that remain poorly understood (Bainbridge 2000). One possibility is that the highly variable lengths of gestation in different mammals produce different selective pressures that have yielded diverse evolutionary responses to the immunological challenges of pregnancy. Or perhaps much of the interspecific variation is due to historical contingencies and phylogenetic legacies. Only further research will tell. Suffice it here to say that any such physiological mechanisms of immunosuppression during a mammalian pregnancy have clearly evolved to minimize the risk that a mother will treat her fetus as a deleterious invasive parasite.

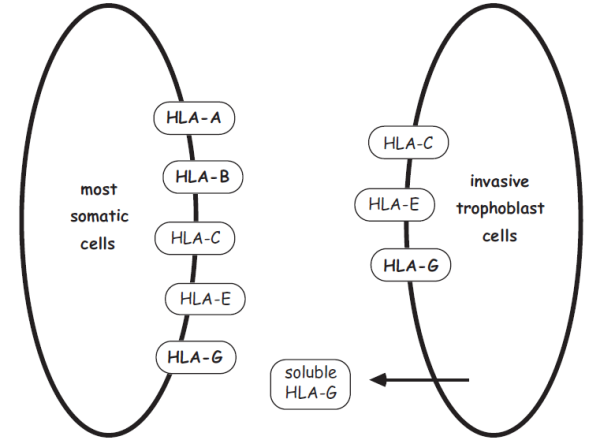

BOX 6.4 The Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC)

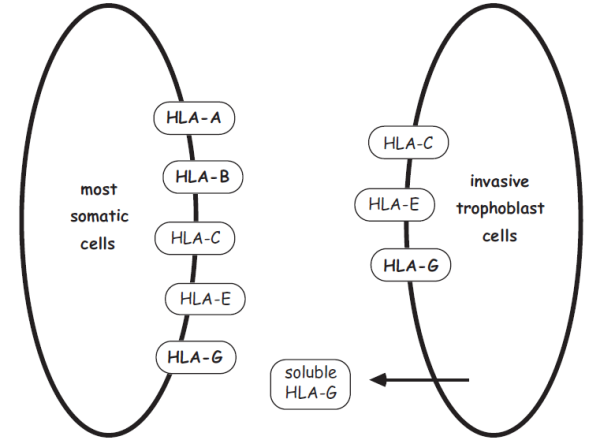

As an example of the biochemical complexity underlying immunological interactions between mother and fetus, consider the expression of a set of loci in the “major histocompatibility complex” (MHC), whose products are responsible for most rejection responses in tissue transplantations. Of special importance are “class I” MHC loci, which typically have two major types of interaction with immune cells: (a) activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (white blood cells) if the latter bear receptors that recognize a specific MHC-peptide combination in the foreign cell; and (b) inhibition of attack by natural killer cells that bear other combinations of MHC receptors. The net effect of these mechanistic operations is to enable an individual to accept or reject specific foreign or domestic cells depending on how their MHC products are expressed. Accordingly, much scientific interest has centered on MHC gene expression in tissues of the placental region and in the trophoblast (the nonembryonic portion of the blastocyst that attaches to the uterine wall and later develops into the fetal portion of the placenta). For example, one basic immunological question has been whether cells of the placenta evade rejection by reducing their expression of molecules that otherwise would provoke the immune response.

Interestingly, the answers have not always proved to be straightforward or easy to interpret. For example, although a reduction in the expression of MHC genes (especially those of paternal origin) has been demonstrated in the placental tissues of some mammals (Antczak 1989), a puzzling finding is that MHC expression is often reestablished in trophoblast cells (perhaps because this somehow either aids the invasion process or exerts an immunoprotective effect on the fetus; Bainbridge 2000). In any event, it seems to be true (as shown in the diagram) that trophoblast cells express a suite of MHC products that differ from most body cells, and immunologists are still exploring many ramifications of these differences for a pregnancy.

In the extreme, a pregnant female who is under exceptional physiological stress may “decide” to resorb some or all of her current litter and perhaps start over when environmental conditions improve. This practice of “brood reduction” is known to occur routinely in sheep, rats, and rodents, for example (Hayssen 1984). Although maternally initiated abortions of this sort might seem shocking, any maternal genes that encode such behaviors are likely to be selectively favored when resorption preferentially involves defective embryos or when the mother’s future reproductive success might otherwise be compromised (Haig 1990). By evolutionary logic, we might predict that most such spontaneous abortions occur very early in a pregnancy (as indeed they do), before mother and fetus become intimately connected via the placenta and when the female is still young and perhaps healthy enough to start a pregnancy anew if need be. We might also predict that in response to the possibility of resorption by their dams, early-term embryos will have evolved hormonal or other countermeasures (such as secreting hGH, as described earlier) to avoid this form of infanticide.

Another type of infant mortality occurs when an adult (sometimes even a parent) kills postpartum young. Such infanticide occurs occasionally in mammals and many other taxa (Hausfater and Hrdy 1984; Parmigiani and Vom Saal 1994), and it appears to have different biological motivations, depending on the species and circumstance. For example, in some cases an adult might kill even its own offspring when both are directly competing for a limited resource such as food, water, territory, or a mate. For an adult male, such shocking behavior can nevertheless make some evolutionary sense when he has a clear physical superiority and especially when he has a poor assurance of paternity for the offspring he attacks (as might be expected, for example, in species that are highly polygamous because the nonrelated victim would unlikely carry copies of the murderer’s genes). Indeed, when a male almost surely is not the biological sire of the infants he assaults, infanticide can sometimes pay double dividends. For example, when an outsider lion takes over a pride, he often kills the kittens and thereby not only destroys the genes of competitor males but also brings each resident lioness into estrus and thereby sets the stage to sire future litters of his own.

Factoid: Did you know? Group-living female mongooses have evolved synchronized pregnancies, and recent research (Hodge et al. 2011) suggests an explanation based on selection against outlier pregnancies. Namely, offspring born too early suffer high rates of infanticide by adults, whereas infants born too late suffer intense competition from other juveniles.

A woman’s monthly bleeding might itself be interpreted as an evolutionary outcome of escalating maternal-fetal conflict (Haig 2010a). Implantation has sometimes been likened to a maternal interview of a conceptus prior to the mother’s full commitment to a laborious pregnancy. In ancestral primates from which humans descended, conceptuses rejected very early in a pregnancy may have differentially involved those that were only superficially (rather than deeply) implanted in their mother’s uterine lining. At the end of each estrus cycle, the flushed material might thus have been little more than the outermost layer of endometrium, and therefore this light menstruation would selectively have favored the survival of any embryos that had invaded the interstitial uterine lining more aggressively. Thus, across the generations, embryos would presumably have evolved tendencies to invade the endometrium ever more deeply, and, in response, females would have evolved stronger tendencies to shed the endometrium in order to maintain an effective screen for potentially defective applicants to the womb. Thus, for the primate lineage leading to humans, an evolutionary hypothesis worthy of further consideration is that “a history of facultative abortion, embryonic evasion of quality control, and maternal responses may help to explain the origin of interstitial implantation and copious menstruation” (Haig 2010a, 167).

Maternal-fetal disputes are not the only types of evolutionary conflict that mammalian pregnancy promotes. The following sections describe two other categories of biological warfare (among siblings and between parents) that arise or tend to be exacerbated in viviparous and other species that practice extensive parental care of offspring.

Most human pregnancies entail singletons, but multibirth pregnancies are the norm in many other mammals. Whenever two or more siblings share a womb, opportunities arise for prebirth intersibling competition for maternal resources such as space and nutrition. Sometimes this struggle can escalate into extreme outcomes such as in utero siblicide (the murder of one sibling by another while both are still in the womb). In mammals, this phenomenon has been well documented in the pronghorn, Antilocarpa americana (fig. 6.5). In this ungulate species, the first blastocyst that implants in a mother’s uterus routinely sends out invasive tissues that pierce and kill some of the other embryos (O’Gara 1969). One net result of such in utero siblicide is that a female pronghorn normally gives birth to twins at most despite the fact that she may have ovulated several eggs that were fertilized in quick succession during her reproductive cycle.

In many other mammals, a less overt form of siblicide in effect occurs postpartum, when suckling by a newborn instigates hormonal changes in the mother’s body that may block a subsequent pregnancy’s initial stages (such as the implantation or preliminary development of another conceptus). Indeed, early embryonic death has been documented as an extended physiological consequence of lactation in several species of domestic ungulates (Jainudeen and Hafez 1980). More generally, however, the incidence rate of such preimplantation siblicide is hard to quantify, partly because a female is likely to resorb remnants of any aborted embryo long before her pregnancy becomes recognizable to researchers and partly because it is unclear in specific instances whether the embryonic deaths should be considered murder by a sibling or infanticide by the mother. By contrast, postimplantation siblicide is somewhat easier to identify and has been reported in several mammalian species (Hayssen 1984). Especially in mammals in which a mother delivers extensive postpartum care to her offspring via lactation, any pre- or postimplantation siblicide promoted by suckling can be interpreted as selfish endeavor by the newborn to short-circuit subsequent pregnancies and thereby promote undivided attention from its mother. Nonetheless, as with all topics reproductive, there is a limit to how far selection can go in promoting such self-serving behavior because the mother, too, has her own vested interests in renewed reproduction, as do any genes in her earlier offspring, which would have copies represented in any additional full-sib or half-sib kin that the focal female might bear.

FIGURE 6.5 The pronghorn, Antilocarpa americana, a North American ungulate mammal with frequent in utero siblicide.

Sibling rivalries and competition for parental resources can extend long beyond infancy as offspring continue to vie for their parents’ finite resources (Hudson and Trillmich 2008). In extreme cases, these conflicts can escalate even to the point of postpartum siblicide, which is common in many nestling birds, for example. Finally, even in species such as humans, which give birth mostly to singletons (i.e., are monotocous), siblings from successive pregnancies are likely to compete for parental resources and may attempt to manipulate their parents (behaviorally, psychologically, or otherwise) even long after their own parturitions (Clutton-Brock 1991; Trillmich and Wolf 2007). Sometimes such attempts at parental manipulation might seem subtle (Sikes and Ylönen 1998), as in kangaroos, where lactation results in the deferred implantation (diapause) of a waiting embryo (Tyndale-Biscoe and Renfree 1987), or in many primates where lactation and nursing temporarily suppress a mother’s fertility (Simpson et al. 1981).

Factoid: Did you know? Nipple stimulation seems to be the proximate factor responsible for the reproductive inhibition and long interbirth intervals experienced by mothers in some primate species (Gomendio 1990).

Selective pressures that pregnancy promotes have led to some outcomes that were entirely unanticipated by the scientific community. One such phenomenon is genetic imprinting: the expression of a gene that is inherited from one parent but not from the other (Solter 1988). In such cases a gene can have very different effects on offspring (and therefore on the course of a pregnancy), depending on whether it was transmitted via the dam (egg) or sire (sperm). Genetic imprinting in animals appears to be confined mostly to viviparous mammals, but the phenomenon is also common in plants (Scott and Spielman 2006; Feil and Berger 2007; Suzuki et al. 2007). In recent years, scientists have discovered imprinted genes in many marsupial and placental mammals, including Homo sapiens, where imprinting has been documented at approximately 100 loci to date. Mechanistically, imprinting usually results from the addition of methyl (–CH3) groups to particular nucleotides during the production of male or female gametes, resulting in the specific inactivation of either maternal or paternal genes in offspring (Reik and Walter 2001). The terms padumnal and madumnal refer to paternally and maternally derived alleles in offspring (in contradistinction to paternal and maternal alleles present in sires and dams, respectively). Thus, genetic imprinting essentially involves altered expressions of madumnal or padumnal alleles (Haig 1996c).

Factoid: Did you know? Imprinted genes account for only about 0.1–0.5% of a mammalian genome, but they have a disproportionately large influence on embryonic growth and development.

Haig (1993, 495) introduced evolutionary interpretations of genetic imprinting (and of various other expressions of conflict during mammalian pregnancy):

“The effects of natural selection on genes expressed in fetuses may be opposed by the effects of natural selection on genes expressed in mothers. In this sense, a genetic conflict can be said to exist between maternal and fetal genes. Fetal genes will be selected to increase the transfer of nutrients to their fetus, and maternal genes will be selected to limit transfers in excess of some maternal optimum. Thus a process of evolutionary escalation is predicted in which fetal actions are opposed by maternal countermeasures. The phenomenon of genomic imprinting means that a similar conflict exists within fetal cells between genes that are expressed when maternally derived, and genes that are expressed when paternally derived.”

In other words, in addition to standard parent-offspring and offspring-offspring conflicts during a pregnancy, we might expect to observe what in effect are parent-parent conflicts with respect to how madumnal versus padumnal genes impinge on resource-acquisition behaviors (and associated growth profiles) of embryos within the mammalian womb. Haig’s seminal ideas have become known as the “conflict hypothesis” or the kinship hypothesis for genetic imprinting. Although other theories of genetic imprinting have been advanced (box 6.5), the conflict hypothesis remains the leading evolutionary explanation for the imprinting phenomenon.

BOX 6.5 Alternatives and Extensions to the Conflict Theory of Genomic Imprinting

At least two other proposals exist for the evolution of genomic imprinting (Haig 2003). First, McGowan and Martin (1997) and Beaudet and Jiang (2002) proposed that imprinting evolved because it imbued populations with increased evolvability. Their basic idea is that whenever an imprinted allele is silenced for one or more generations and thereby effectively masked from exposure to natural selection, it becomes freer to accumulate mutations and thereby adds to the pool of hidden genetic variation that sooner or later might contribute to evolutionary responses to environmental change. This hypothesis at face value is unappealing to many evolutionary biologists not only because it seems to invoke group selection but also because it is vague about which particular genes should be imprinted and why those genes are marked but not others. Second, Varmuza and Mann (1994) proposed that oocyte genes responsible for trophoblast formation (and perhaps some “bystander” loci also in the oocyte) are inactivated so as to prevent diseases (such as teratomas) that can otherwise arise when an unfertilized egg implants inappropriately. Formal evolutionary models have shown that this “ovarian time bomb” hypothesis is at least plausible (Weisstein et al. 2002), but whether it is the correct general explanation of genomic imprinting remains to be determined.

Apart from genetic imprinting per se, several other genomic phenomena have been proposed to arise from evolutionary conflicts of interest between padumnal and madumnal genes during ontogeny. For example, Frank and Crespi (2011) suggest that such intragenomic conflict may affect the regulation of embryonic growth in ways that may precipitate various pathologies such as some cancers and psychiatric disorders (including some cases of autism and schizophrenia). More generally, these authors view evolutionary-genetic conflict as sexual antagonism that can lead to pathologies whenever opposing genetic interests that normally are precariously balanced become unbalanced for any reason. Burt and Trivers (2006) extend this evolutionary argumentation to a broad spectrum of otherwise puzzling empirical properties of genomes.

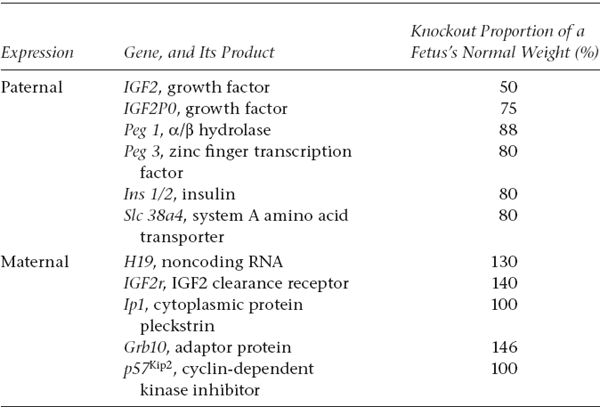

Subsequent research has shown that imprinting is most prevalent for genes expressed in tissues that are specialized for transporting maternal nutrients to the embryo, namely, the placenta in mammals and the endosperm in plants. Given the benefit of evolutionary hindsight, perhaps these two foci for imprinting are not surprising. In plants and mammals alike, mothers invest heavily in their progeny (by supplying seeds with nourishment and by becoming pregnant, respectively). Especially in such species with highly gender-asymmetric parental care, genes carried by males versus females presumably experience different selective pressures related to their prospects for survival and replication in progeny. Thus, genes transmitted to embryos from dams versus sires are likely to view the reproductive world through very different eyes, and this gender-based difference appears to play out during evolution in how specific genes become imprinted in embryo-nurturing tissues. Two such placental genes that appear to influence an embryo’s acquisition of maternal nutrients during gestation are insulin-like growth factor II (IGF2) and insulin-like growth-factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), and both of these loci have been the subject of extensive investigations in an imprinting context (Tycko and Morrison 2002; Reik et al. 2003; Frost and Moore 2010; Panhuis et al. 2011). Several more such imprinted genes and their empirical effects on intrauterine growth are compiled in table 6.1.

TABLE 6.1 Examples of imprinted mammalian genes and their effects on intrauterine growth of mouse embryos1

Note that the paternally expressed alleles tend to stimulate embryonic growth (because knocking them out reduces fetal weight), whereas maternally expressed genes tend to depress intrauterine growth (because knocking them out boosts fetal weight).

1After Fowden et al. 2006.

Factoid: Did you know? The endosperm of a plant is an extraembryonic structure that nourishes a plant embryo much as the placenta nourishes a mammalian embryo.

The basic evolutionary idea is that from a father’s selfish fitness perspective, any paternal genes in his progeny should be expressed in such a way as to promote the health and survival of his offspring (each of whom shares 50% of his genes) even if this comes at the expense of the health of the mother (who normally shares 0% of her genes with the sire) and her future offspring (who might have different sires). Conversely, maternal genes should be expressed in such as way as to limit the current offspring’s hegemony over maternal resources to a level that is more compatible with the mother’s continued health and future reproduction. In other words, the conflict or kinship theory of genomic imprinting states that paternal genes maximize the extraction of maternal resources for the benefit of the focal sire’s offspring but does so at the expense of offspring from future pregnancies, who may have different sires; by contrast, the maternal genome limits its support for each embryo irrespective of the paternal genome. Such evolutionary reasoning also highlights the fact that the phenomena of genomic imprinting and kin selection are thoroughly intertwined (Haig 2002, 2004b).

Thus, what emerges in each species during the evolutionary process is some resolution of the conflict between the optimal tactic for genes inherited from the sire versus that for genes inherited from the dam (reviews in de la Casa-Esperon and Sapienza 2003; Wilkins 2005; Haig 2000). In general, padumnal genes are under selection to promote embryos to extract the maximum possible nutrition from the mother, whereas madumnal genes tend to be under selection to relinquish fewer resources. Furthermore, many biologists now suspect that these skirmishes over maternal resources transpire precisely where they might be most expected: at the physical sites (placenta and endosperm) where mothers deploy nutrients to their embryos. Unfortunately, these strategic battles between madumnal and padumnal genes in utero come not without serious medical consequences, especially for embryos that may be caught in the evolutionary crossfire.

Consider, for example, conflicts between paternally and maternally derived genes along a small region of human chromosome 15 that is responsible for two contrasting medical disorders: the Prader-Willi and the Angelman syndromes. In normal pregnancies, paternally derived genes in this chromosomal region probably favor high infant activity (including sleeplessness and aggressive feeding), whereas maternally derived genes in the same locus have more of a restraining influence on an infant’s behavior. However, when the padumnal copy of the gene is unexpressed (e.g., either because of a small deletion or via imprinting), the net result is Prader-Willi disorder, which causes the affected child to be short of stature and obese and to display poor motor skills, underdeveloped sex organs, and mental retardation. Conversely, when the madumnal copy of the gene is unexpressed (again because of a deletion or imprinting), the net result is a child with Angelman disorder, which causes slow development and certain neurological difficulties. Thus, these complementary syndromes, which originate in the same chromosomal region, exemplify at least two points relevant to the current discussion: (a) the paternal versus the maternal source of particular genes can in some cases cause large differences in offspring behavior, and (b) when the expression of the maternal or paternal copies of such genes is disrupted for any reason, interallelic conflicts may occur and sometimes have major consequences for human health.

TABLE 6.2 Human disorders related to imprintingi

Shown are examples of human metabolic disorders for which genomic imprinting is known to be a contributing factor in at least some cases.ii

Angelman syndrome. A disorder that causes delayed development and neurological problems, including jerky movements, sleep disorders, and seizures; associated with a small gene region on chromosome 15, which, when improperly imprinted or missing in progeny, results in this syndrome (see also Prader-Willi syndrome).

Fetal growth restriction. A condition in which a fetus is unable to reach its genetic potential for body size; can have many different etiologies, including errors in genetic imprinting.

Gestational diabetes. A form of diabetes (a disease in which the pancreas cannot properly produce or utilize insulin) that occurs in otherwise nondiabetic women during pregnancy.

Prader-Willi syndrome. Another serious genetic disorder associated with imprinting or other errors at a gene region on chromosome 15 (see also Angelman syndrome).

Preeclampsia. A disorder that affects both the mother and fetus typically in the second or third trimester; it involves rapidly progressing symptoms, including sudden weight gain, headaches, and changes in vision; affects 5–8% of all pregnancies and can be fatal.

Rett syndrome. A neurological disorder that begins in early childhood and is characterized by autistic-like behavior, language impairment, and mental retardation; caused by male germ-line mutations in an X-linked gene (MECP2) that codes for a methyl-CpG binding protein.

Spontaneous miscarriage. Termination of a pregnancy during the first 20 weeks of gestation; can have many different causes, but some cases involve imprinting errors.

Turner syndrome. A genetic disorder in girls often associated with failed ovarian development, webbed neck, drooping eyelids, heart and kidney defects, and other symptoms; caused by a missing or defective X chromosome with some of the health problems, depending upon whether the chromosome came from the sire or dam.

iAfter Avise 2010.

iiMany of these syndromes relate directly or indirectly to pregnancy phenomena.

Several other imprinted genes in humans are likewise known to cause serious disorders. Consider, for example, the IGF2 gene, which encodes an insulin-like growth factor. Normally, only the paternal copy of IGF2 is expressed in offspring, but if the sire’s copy of IGF2 is silenced through a biochemical mishap during spermatogenesis, a child may be born with Silver-Russell syndrome, which is characterized by abnormally low birth weight and retarded growth. Conversely, if the mother’s copy of IGF2 is silenced by a biochemical mishap during oogenesis, her child may display Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, characterized by high birth weight and symptoms of overgrowth often associated with an increased risk of tumors. As summarized in table 6.2, abnormalities in genomic imprinting similarly play leading roles in at least some clinical cases of several other common metabolic disorders during human pregnancy, including preeclampsia, miscarriage, fetal growth restriction, and gestational diabetes. Scientific evidence further suggests that some widespread psychiatric illnesses, including autism and schizophrenia, might also be linked to the imbalanced gene expression that is sometimes related to imprinting (Badcock and Crespi 2006; Crespi and Badcock 2008; Crespi et al. 2010). One scientific suggestion is that patterns of imprinted-gene expression affect not only pregnancy but also brain development (Gregg et al. 2010; Keverne 2010) and that deviations in those imprinting patterns can cause metabolic imbalances that can lead in exceptional cases to severe mental illness. If so, where one resides on a spectrum ranging from autism to normalcy to psychosis may be partly the result of one’s imprinted genes, which themselves probably became imprinted ultimately because of the evolutionary “battle of the sexes” (Badcock and Crespi 2008) that mammalian pregnancy promotes.

1. Pregnancy in mammals has been shaped by and in turn energizes powerful forms of natural selection, both positive and negative. However, not all pregnancy-related phenomena in viviparous mammals evidence selective effects or demand adaptive explanations; some almost certainly do, some almost certainly do not, and others are ambiguous in this regard.

2. Embryonic diapause (a delay between conception and implantation) has evolved independently in several mammalian taxa and can be highly adaptive in particular environments. Sporadic polyembryony (the occasional production of clonal siblings) occurs in several mammals, including humans, but is probably happenstantial and has no special selective significance. Both constitutive polyembryony and dizygotic twinning in particular mammalian taxa have elements that remain controversial in terms of their evolutionary motivations and their ramifications for natural selection.

3. Despite outward appearances, mammalian pregnancy is not simply a loving collaborative venture within the nuclear family (mother, father, and child); rather, it is a phenomenon rife with inherent evolutionary genetic conflicts that sometimes escalate to what has often been described as biological warfare. In pregnancy, such conflicts can be both intra- and intergenerational, and they include (a) disagreements between parents and progeny about the delivery of offspring care, (b) sibling competition both in utero and postpartum, and (c) in effect, parental disputes about how genes of maternal versus paternal origin should be expressed in conceptuses.

4. Many physiological conflicts and accommodations exist between a pregnant mother and her sexually produced fetus. Generally, each self-serving offspring is under selection to seek more maternal resources than its mother might wish to relinquish given the negative effects that such donations can have on a dam’s lifetime genetic fitness. Ultimately, such conflicts are resolved as evolutionary compromises between the oft-competing genetic interests of mother and child. Proximately, maternal-fetal conflicts during a pregnancy can register as a wide array of health problems ranging from the relatively subtle (such as morning sickness) to the egregious (such as infanticide and litter reduction by spontaneous abortion).

5. One of the wonders of mammalian pregnancy is that the mother’s immune system does not recognize and reject the fetus as being genetically foreign (as it would do for any other invasive parasite). Several mechanisms have evolved by which mothers and their fetuses circumvent histoincompatibility. These often fall into three categories: fetal modification of the expression of its transplantation antigens; fetal modulation of the maternal immune system to its own advantage; and placental impediments to the passage of effector molecules that otherwise implement the immune response.

6. Even menstruation might be interpreted as an evolutionary outcome of parent-offspring conflict early in a pregnancy. The process by which an embryo implants into its mother’s uterus can be likened to a maternal “interview” of a conceptus prior to the dam’s full commitment to a laborious pregnancy. During this interview, fetuses are under selection to avoid rejection, while the female is under selection to maintain an effective screening of womb applicants. The net result may have been increased invasiveness by the embryo and the evolution of menstruation, wherein primate females shed increasing amounts of uterine tissue in their efforts to abort defective conceptuses.

7. Especially in mammals with multipup litters, conflicts over finite maternal resources routinely arise among siblings, both in utero and postpartum. Such disputes sometimes escalate to overt siblicide, but often they are expressed in subtler ways, such as when suckling by a newborn stimulates hormonal responses in the mother that prompt her to delay or even abort subsequent conceptions.

8. Another category of genetic conflict exaggerated by pregnancy pertains to the two parents because selfish genes of paternal versus maternal origin in progeny inevitably experience different selective pressures. In mammals, this sexual difference sometimes plays out via genetic imprinting, wherein gene expression in progeny depends on which of the two parents transmitted the imprinted gene. Understandably, genetic imprinting seems to be especially prominent in the placenta (in mammals) and the endosperm (in plants), two tissues intimately involved in supplying nutrients to embryos. Imprinted genes are now known to underlie many biochemical imbalances that cause serious metabolic disorders in humans.