Each human pregnancy technically begins when a sperm cell and an ovum unite inside a woman and produce a fertilized egg or zygote, whose nucleus contains 2 nearly matched sets of genetic material, one from the father and the other from the mother. This never-before-seen mixture of genes interacts to help direct the progeny’s biological life—from preembryo to the person’s death perhaps decades later. However, in the first 2–4 rounds of cell division, most of the RNA and protein molecules that orchestrate ontogeny are maternal holdovers that the mother produced and deposited into the egg’s cytoplasm. Much of the primary activation in the zygotic genome itself occurs after a ball of 4–16 preembryonic cells has formed. After further rounds of cellular division, a fluid-filled cavity forms within the growing cell ball. This hollow sphere, known as a blastula, consists initially of approximately 100 cells. To one side of its central cavity is a knob of undifferentiated cells, the inner cell mass from which embryonic stem cells are derived. Eventually, these cells give rise to all of the approximately 260 different cell types that make up each person’s tissues, organs, and all other body parts (including gonads, which are destined to produce gametic cells of the potentially immortal germ line).

Another key event in pregnancy occurs when the conceptus, now called a blastocyst, implants in the mother’s uterine wall during the second week after fertilization. Differentiation of the embryo’s body parts (and the pregnancy itself) then begins in earnest. For example, by week four an embryonic heart takes shape and begins to beat. One week later, the embryo reaches a length of about one-third of an inch. By week eight, rudimentary precursors to all adult body structures are present, and the developing individual is termed a fetus. By the end of the first trimester (12 weeks), the 2-inch-long fetus becomes recognizably human (as opposed to another animal). By the end of the second trimester (at 24 weeks), the fetus is almost a foot long, and at 37–40 weeks the mother enters labor, and a baby is born.

The birth or delivery of a child represents the transition from the highly intimate bonds of internal gestation to what is thereafter a physical separateness of offspring and mother. Clearly, pregnancy is a major happening that directly affects a woman’s life much more so than a man’s. From an evolutionary perspective, pregnancy is yet another of the many pronounced reproductive asymmetries between the sexes that stem ultimately from anisogamy and can make procreative dramas so poignant in sexually reproducing species (table 5.1).

Although no book on pregnancy would be complete without at least some discussion of viviparity in Homo sapiens (fig. 5.1), I keep this chapter rather short for several reasons: (a) It would be presumptuous of me to expound unduly on a biological phenomenon about which nearly 50% of humanity (women) have far more personal knowledge than I do; (b) broader evolutionary ramifications of mammalian (including human) pregnancy are detailed in chapter 6; and (c) I prefer here just to introduce some fascinating peculiarities and oddities of human pregnancy, in both fact and fiction.

The mythologies and religions of most human cultures are replete with stories of varied biological phenomena that are often associated with real-life pregnancies. What follows are merely a few examples involving either the gods and heroes of ancient Greece (mostly from a review by Iavazzo 2008) or the folklore of Native Americans (mostly from Niethammer 1977).

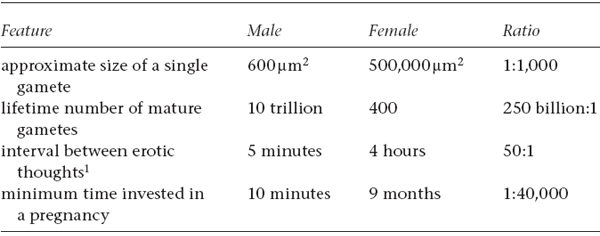

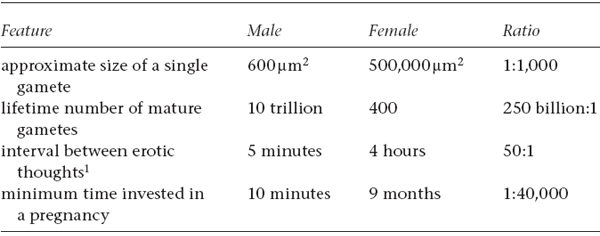

TABLE 5.1 Reproductive disparities between human males and females.

Shown are merely a few examples of how dramatically men and women can differ in features related to reproduction and pregnancy. In the ratio column, each “1” applies to the male sex and the other number applies to the female sex.

1This estimate is merely a guess.

FIGURE 5.1 The beauty and burden of human pregnancy.

Most human societies have recognized at least some general connection between sexual intercourse and pregnancy, but a clear understanding of fertilization and embryonic development is a surprisingly recent achievement in human history. In several Native American tribes, including the Apache, the blood (semen) from a man that enters a woman during coitus was thought to be opposed by the woman’s blood, such that repeated lovemaking was required to build up the supply of male seed within a woman and thereby overcome her inherent resistance to pregnancy. The Hopi tribe of northern Arizona went one step further by supposing that continued sex throughout the pregnancy was important for fetal growth in much the same way that continued irrigation promoted the growth of their crops. On the other hand, women of the Fox tribe in Wisconsin generally abstained from sex during pregnancy for fear that their babies otherwise would be born “filthy.”

Factoid: Did you know? As a fetus, each human female has about seven million potential eggs (primary oocytes), but only 350 of these survive to reach maturity in a grown woman, and only a few of the latter may become fertilized and eventuate in a successful pregnancy.

With respect to overcoming problems of infertility, women in various Native American tribes tried all sorts of remedies: rituals, such as praying or placing little girls’ clothing on a special “baby hill”; consultation with older women or with a wise medicine man; and numerous dietary gimmicks ranging from eating red ants to drinking boiled water saturated with rat urine and feces (an extreme practice reported in the Havasupai tribe living near the Grand Canyon).

Understandably, Native American women showed similar inventiveness in their ritualistic and other efforts to achieve exactly the reverse outcome: birth control (box 5.1). Indeed, quests for workable methods of birth control and its antithesis (fertility enhancement) have preoccupied nearly all human societies, cultures, and religions (Maguire 2003). Among native North Americans, some methods employed to avoid pregnancy include the following: brewing abortive potions from various plants in the local environments, as did many women in the Quinault and Salish tribes; licking the powder from dried and pulverized ground squirrels, as did some Havasupai women; and urinating on ant mounds or willing persistently that a child not be conceived, as did Yuma women who sought to avoid pregnancy.

BOX 5.1 Birth Control

Technically, the phrase “birth control” can refer to any method used either to prevent syngamy or to interrupt a pregnancy at any stage before parturition. It thus can include any of the following: any contraceptive device (such as a condom or diaphragm) or substance (such as a spermicidal gel) or behavior (such as coitus interruptus or withdrawal) or medical procedure (such as a male vasectomy) that in effect foils the fertilization process; any contragestive approach (such as a physical intrauterine device or hormonal intervention) that prevents implantation of the blastocyst in the womb; or any abortion of a pregnancy that already is under way. To the extent that a birth control method is effective, it can give a couple some degree of proactive control (other than sexual abstinence) over reproduction and family planning. Little wonder that women (and men) throughout the ages have sought to discover and employ effective birth-control methods. To the ancient Romans and Greeks, this often meant ingesting particular plants (such as pennyroyal or willow) or using intravaginal potions (such as mixtures of honey and acacia gum) that were thought to have contraceptive properties. Early texts in Islam and Christianity indicate that women have long used a variety of vaginal suppositories ranging from rock salt to elephant dung in their efforts to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Even some men occasionally did their part by using all sorts of contraceptive devices intended to short-circuit ejaculations or otherwise block sperm transfer to their mate.

In the modern era, several effective barrier methods are available for birth control, as are various ingestible, injectable, or implantable methods for delivering a range of hormones that may act either as contraceptives or contragestives. Most of the latter are designed for use by women, but attempts also continue to develop an effective oral or other contraceptive drug for men. Of course, modern medicine has also made abortion a much safer (although no less socially controversial) procedure of last resort.

In 1978, the world witnessed the birth of the first “test-tube baby,” Louise Joy Brown. Louise had been conceived by an assisted reproductive technology (ART) known as in vitro fertilization (IVF). In this then-revolutionary method, an ovum and a sperm are united in a petri dish (rather than in the woman’s reproductive tract via coitus), and the resulting product is then implanted in a woman’s uterus, where gestation of the embryo and fetus proceeds as usual. For many couples IVF proved to be a godsend because it can bypass numerous sources of infertility such as sperm immotility or even structural damage to a female’s reproductive tract (especially if the IVF embryo is implanted and then incubated in the womb of a surrogate mother, as often is done). By 1995, nearly 150,000 IVF babies had been born, and the number of such babies today exceeds three million worldwide. Nowadays IVF is just one of several ARTs that can help couples (or even singles) produce babies in nonconventional ways (Avise 2004a).

Unconventional conceptions and ARTs were anticipated in Greek mythology. Indeed, two of the ancients’ most famous female protagonists—the goddess Aphrodite and the beautiful Helen of Troy—both arose by nonstandard means. Aphrodite’s story begins with the castration of Uranus (the father of the gods) by his son Cronus, while Uranus slept with the goddess Night. Cronus then threw the severed genitals into the Mediterranean Sea, where they formed a frothy brew from which Aphrodite (from aphros, meaning “sea foam”) arose in what might be deemed an extracorporeal type of fertilization or pregnancy. Aphrodite later became the irresistible (aphrodisiacal) goddess of love and sexual rapture.

Helen of Troy’s birth can be interpreted as an ancient example of surrogate motherhood (and perhaps of ovoviviparity, too). Helen was the daughter of Zeus and either Leda or Nemesis. The maternal ambiguity arises as follows. By one account, Nemesis initially refused Zeus’s sexual advances by transforming herself into a goose. When Zeus discovered this trick, he transmogrified into a swan and slept with Nemesis. What resulted from this union was a blue egg that Leda later recovered and put into her vagina to keep warm. Thus, when Helen finally emerged from the inserted egg, her surrogate mother may have been the ovoviviparous Leda, but her biological or genetic mother apparently was Nemesis.

Superfetation is the co-occurrence of two or more embryos at different developmental stages in a pregnancy because fertilization took place on separate occasions within the mother’s body, implying either that the embryos had different sires or that their mother’s ova were fertilized at different times by the same male. Although superfetation is common in some animals, including particular fish species (see box 2.2), in humans it is an extremely rare occurrence at best, with fewer than a dozen (mostly anecdotal) reports of such happenings. In one such media-dramatized case, an Arkansas woman purportedly became pregnant twice, two weeks apart. In theory, superfetation in humans would normally require a conjunction of two rare events within the female body: continued ovulation after the first conception and successful implantation of a second fertilized egg at an atypical gestational site (see the later section on ectopic pregnancy). This type of conjunction is statistically highly unlikely because the joint occurrence of two or more rare events is equal to the product of their separate probabilities.

Factoid: Did you know? Uterus didelphis is a rare embryological malformation that results in the duplication of portions of a woman’s reproductive tract, such that her uterus exists as a paired organ rather than the standard singleton. This condition apparently underlies some of the reports of superfetation in human twin pregnancies (Williams and Cummings 1953; Dorgan and Clarke 1956). For example, in one case a woman with uterus didelphis delivered twins with a birth interval of more than two months (Nohara et al. 2003).

Exactly how often bona fide superfetation occurs in Homo sapiens remains unclear, but what is undeniable is that superfetation took place in Greek mythology. One such case involved the twin pregnancy of Hercules and Eficles, both born of Alcmene (the princess of the Greek kingdom of Mycenae and the wife of Amfitryon, the king of another Greek city-kingdom). This all came about because Alcmene had an illicit affair with Zeus on the same long night that she also slept with her husband, such that the two boys were conceived of different fathers. Presumably this explains why the twins had such different personalities. An analogous story applies to Leda’s twin pregnancy of Castor (son of Zeus) and Pollux (son of the king of Sparta). Apparently Leda, too, displayed a high libido and was rather promiscuous.

In modern human populations, approximately 1% of pregnancies result in the birth of twins, and in about one-third of those cases the twins are genetically identical (i.e., they are clonemates) (Bulmer 1970; MacGillivray et al. 1988). Identical twins, triplets, quadruplets, and so on are invariably the same sex (barring developmental anomalies). They arise via a phenomenon known as polyembryony, wherein a single fertilized egg mitotically divides into two or more genetically identical cells or sets of cells, each of which initiates embryogenesis in the mother’s womb. Thus, all polyembryonic offspring in a pregnancy share a unique combination of paternal and maternal genes that were joined in a single union of sperm and egg. Monozygotic or identical twins are to be distinguished from dizygotic (nonidentical) twins, which arise from separate unions between sperm and oocytes. Genetically, dizygotic human twins (also called fraternal twins) are as different from one another as are any other full siblings (brothers and sisters from a woman’s separate pregnancies with the same sire). Multiple offspring (such as triplets) within a single human pregnancy sometimes include both fraternal and identical individuals.

Factoid: Did you know? A few well-documented human pregnancies have involved as many as eight babies born alive and more than a dozen embryos carried in utero for at least a short time. In recent years, multiple embryo transfer and the use of fertility drugs (which stimulate multiple eggs to mature in an ovulatory cycle) have greatly increased the frequency of human multiple births.

Extremely rare instances of the delivery of more than two monozygotic individuals are known in human pregnancies (Dallapiccola et al. 1985; Markovic and Trisovic 1979; Steinman 1998). Occasional or sporadic instances of identical twins have also been recorded in several other vertebrate species, including cattle (Ensminger 1980), pigs (Ashworth et al. 1998), deer (Robinette et al. 1977), whales (Zinchenko and Ivashin 1987), various birds (Berger 1953; Olsen 1962; Pattee et al. 1984), and fish (Laale 1984; Owusu-Frimpong and Hargreaves 2000). However, the phenomenon of sporadic polyembryony might be underreported for many sexual species because, to my knowledge, no one has searched methodically—using suitable genetic markers—for polyembryonic (clonemate) progeny in nature.

On rare occasions, the bodies of identical twins become joined in utero and might later be delivered as “conjoined twins” (also known as “Siamese twins”), whose bodies are partly fused. Conjoined twins, who usually arise by the partial fission of a fertilized egg, share the same embryonic membranes and placenta during gestation. Today, conjoined human twins can sometimes be separated by surgical procedures (depending on the placement and extent of their melded body parts). However, some conjoined twins grow and spend their lives together in a partially welded condition.

Twins of various sorts were also a recurring theme in Greek and other mythologies. One such example mentioned earlier involved Hercules and Eficles, both born of Alcmene but sired by different fathers. In this fictional case, Hercules and Eficles would have been “half-sib twins” rather than “full-sib twins” because they shared only one parent. Another fictitious example of a half-sib twin pregnancy (i.e., superfetation) involved Leda’s gestation of Castor and Pollux (mentioned earlier). Apollo (the sun god) and Artemis (the moon goddess) are a more conventional pair of twins from Greek mythology. Many other mythological twins likewise have dualistic natures or split personalities. Some examples include the Egyptian figures Geb (the earth god) and Nut (the sky goddess); the twins Ahriman (the spirit of evil) and Ahura Mazda (the spirit of good) of Zoroastrian mythology; and the twin brothers Kuat (who became the sun) and Iae (the moon god) in the creation mythology of the Xingu people of Brazil.

Factoid: Did you know? In humans, the incidence of conjoined twins is about one such pair per 50,000–100,000 live births.

For many Native North Americans, twins had a special significance both in mythology and in peoples’ mortal lives. In an example of mythological twins, some northeastern tribes believed that the creator god Gluskap had an evil twin, Malsum, the ruler of demons. With regard to more concrete examples from daily life, some tribal societies supposed that a woman’s birth of twins evidenced a special potency or virility of her mate or that twins perhaps resulted from too much sex. And in some Native American cultures, women who wished not to conceive twins often avoided eating paired fruits, such as double almonds or split bananas.

This unusual phenomenon—implantation of the embryo outside the normal uterine cavity—is a contributor to spontaneous abortion and an important cause of maternal mortality during the first trimester of human pregnancy (Khan et al. 2006). A fallopian tube, which connects each ovary to the uterus, is the most common site for an ectopic pregnancy, but in rare circumstances other known locations have been a woman’s ovary, her general stomach area (Tait 1880; Stromme et al. 1959), and her cervix (the constricted lower end of her uterus). The developing cells of the embryo cannot survive for long in these nonstandard locations, so real-world ectopic pregnancies almost invariably fail.

Ectopic pregnancies are not necessarily lacking in the world of Greek mythology, however. Athena (the goddess of wisdom, war, arts, industry, justice, and skill) was live-born from a truly bizarre form of ectopic pregnancy. Athena was the daughter of Zeus and his first wife, Metis. During Metis’s pregnancy, Zeus heard a prophecy that his child would someday slay him in order to inherit the throne. To avoid this fate, Zeus ate Metis, only to find himself suffering from a severe headache exactly nine months later. To alleviate this pain, Prometheus (the Titan god of forethought) opened Zeus’s head with an axe, and out popped a healthy Athena. Zeus’s head had provided a serviceable substitute womb for this strangely ectopic pregnancy!

Factoid: Did you know? Fallopian tubes get their name from Gabriele Falloppio, a prominent Italian anatomist and physician of the 16th century. He worked mostly on the anatomy of the human head and ear, but he also studied the reproductive organs of both sexes.

By definition, any onset of human labor prior to 37 weeks of gestation can lead to the “preterm birth” of a premature baby (sometimes insensitively called a “preemie”). In the United States, preterm birth occurs in about 12% of pregnancies and is a leading cause of perinatal (“near-birth”) mortality (Goldenberg et al. 2008). Worldwide, “prematurity” yields about 500,000 neonatal deaths per year (lung failure is a common proximate causal agent because the lungs are among the slowest organs to develop in a fetus). All else being equal, the survival rates of premature babies tend to increase in direct proportion to the duration of prelabor gestation. However, premature infants who receive heroic medical care (including attachment to a respirometer) stand a reasonably good (50%) chance of survival even if they have gestated internally for as little as 24 weeks (Kaempf et al. 2006).

Prolonged pregnancy (Higgins 1954) lies at the opposite end of the spectrum from preterm labor. Usually a prolonged pregnancy in humans is defined as any gestation that exceeds 41–42 weeks. Without intervention (i.e., via the induction of labor or a cesarean section), 7–18% of all pregnancies in the United States reach these impressive temporal milestones.

In Greek mythology, a famous story of a preterm birth in one pregnancy and a delayed birth in another involved the pregnancies of Alcmene, when she bore Heracles (one of the greatest of the Greek heroes), and of Nikippi, when she bore Eurystheas (who would later rule the city of Argos). The unusual durations of these two pregnancies came about as follows. During Alcmene’s pregnancy, Zeus (the likely father) announced to the gods that the first child born to the family of Perseas (the grandfather of Alcmene) would become the king of Argos. Hera (Zeus’s wife) understandably became disturbed when she learned of this promise, so she asked Eilytheia (the goddess of labor) to help her thwart Zeus’s plans. Eilytheia complied by delaying Alcmene’s labor while at the same time greatly hastening that of Eurystheas. As a result of these two temporal adjustments, when Zeus’s oath was fulfilled, it was indeed Eurystheas (not Heracles) who eventually became the ruler of Argos.

Factoid: Did you know? The shortest-term premature human baby on record had a gestation of only 21 weeks and 6 days.

Factoid: Did you know? Compared to other primates, gestation times in humans have evolved to be extraordinarily short relative to neonatal body size, probably because of our need to deliver large-headed babies through a narrow birth canal. Furthermore, scientists recently discovered one of the “birth-timing” genes responsible for the relatively short gestations in Homo sapiens (Haataja et al. 2011).

Leto (another of Zeus’s many lovers) is another example of prolonged pregnancy in the tales of the ancient Greeks. When a jealous Hera learned of Leto’s pregnancy, she sent a big snake (a python) to chase Leto and thereby thwart Leto’s attempts to find a safe birthing site. This long and eventful chase across much of Greece greatly delayed Leto’s birth of Apollo and Artemis and thus can be considered the root cause of Leto’s prolonged pregnancy.

A spontaneous abortion or miscarriage is usually defined as the expulsion (and death) of a human embryo or fetus before approximately the 22nd week of gestation. Particular instances may have a genetic etiology (frequently involving difficulties in chromosomal replication in the embryo; Plachot 1989), or they may be due to physical trauma or to biochemical or physiological difficulties during a pregnancy. Approximately 10–50% of human pregnancies eventuate in a clinically apparent miscarriage, but these statistics are misleadingly low because most miscarriages occur very early in a pregnancy and often are unbeknownst even to the mother. For example, one scientific study found that 70% of conceptuses were lost within the first 12 weeks postfertilization (Edmonds et al. 1982), and another study (Roberts and Lowe 1975) estimated that 78% of human conceptions never come to a full-term fruition. Thus, human pregnancy far more often leads to the death rather than to the successful birth of a new person.

Factoid: Did you know? Human mothers have remarkably effective physiological screening mechanisms that endogenously examine and often sift out (spontaneously abort) genetically defective embryos (Forbes 1997).

People have always appreciated (or presumed) that a mother’s actions during a pregnancy can affect the outcome. Depending upon the circumstances, sometimes a woman’s intent is to avoid a spontaneous abortion, and sometimes it is to induce the abortion of an unwanted child. Either way, pregnant women in all human cultures have certainly had no end of folklore and potential remedies to draw upon (Maguire 2003). For example, in the second century a Greek physician, Soranus, wrote in Gynaecology that an unwanted pregnancy might be aborted if a woman jumped vigorously, lifted heavy objects, or rode animals. Moreover, the ancient Greeks were neither the first nor the last to suggest that the ingestion of various medicinal plants (such as silphium) or other food substances could terminate a pregnancy. In the modern era, induced abortions (both legal and illegal) continue and indeed are standard medical practice in many countries (especially when the mother’s health is at severe risk).

Apart from the issue of whether a pregnancy goes to term, many cultures have had notions that external prenatal events affect fetal development and perhaps even influence the baby’s mode of delivery. Among Native North Americans, a common belief was that a pregnant woman should avoid viewing or mocking a deformed or an injured person lest her own child be born with that same defect. Some pregnant women avoided eating livers and berries lest their babies be born with dark skin or birthmarks, respectively. Similarly, eating an animal’s feet was perilous because it might cause a woman’s fetus to be born feet first. Personality traits were no less subject to dietary and other environmental influences. For the Lummi tribe of northwestern Washington, a prospective mother who ate venison might give birth to an absent-minded child, and one who ate seagulls would likely deliver a crybaby. Today, in the United States, many parents suspect that a fetus’s exposure to classical music while still in the womb might later promote musical abilities in the child.

Among Native North Americans, societal customs and beliefs related to abortions varied widely. Some Plains tribes such as the Cheyenne considered abortion to be outright homicide, and accordingly they prosecuted as a murderess any woman who purposely killed her unborn child. On the other hand, although the Papagos of southern Arizona disapproved of and criticized any woman who sought abortions, they exercised no official sanctions against the practice, believing instead that the decision was best left to the woman and her family.

Factoid: Did you know? In the United States today and in recent decades, about 2% of all pregnancies are purposely terminated in facilities such as abortion clinics, doctors’ offices, and hospitals (Jones and Kooistra 2011). In other words, approximately 25 legal abortions are conducted per 1,000 pregnancies (and the number of undocumented illegal abortions is surely much higher).

Even infanticide (the killing of a live-birthed child) was tolerated in some tribal societies in the Americas, especially in harsh environments, where the sheer survival of the family or group sometimes had to take precedence over having yet another mouth to feed. For example, in the severe conditions of life in the arctic and subarctic, the Eyak and Kaska peoples occasionally resorted to infanticide as a last-resort method of population control when starvation otherwise loomed for all. In other cases, infanticide was motivated not by harsh environmental conditions but rather by the birth of a severely deformed or diseased infant who would only be a burden to family or tribe. Among the Comanches of the Southern Plains, the fate of a child with a disability was decided by medicine women after consultation with other people who had attended the infant’s birth. Finally, in some tribal cultures such as the Hopi of Arizona, medicine men did not purposely kill infants with defects, but neither did they go to great lengths to keep these infants with deformities alive.

A C-section (CS) is a surgical procedure in which an incision is made in a mother’s abdomen and uterus to free one or more babies there. Contrary to popular belief, the name of this nonvaginal mode of delivery has nothing to do with the birth of Julius Caesar. Instead, it probably traces back to an ancient Roman law (ca. 700 b.c.) known as Lex Caesarea, which forbade the burial of any fetus-carrying woman who had died during childbirth (van Dongen 2009). The baby first had to be removed (cut out) from within its deceased mother.

Factoid: Did you know? The first well-documented cesarean section performed on a live woman took place in Germany in 1610. The woman survived for nearly a month before dying of infection, and the child lived for 9 years.

In general, a successful C-section can be defined as the survival of both mother and child for at least 1 month after the CS was performed. By this criterion, successful CSs were extremely rare before the introduction of anesthesia, antisepsis, and other premodern surgical procedures of the 19th century. Nevertheless, occasional reports persist from earlier times of partly successful CSs (in the sense that the baby may have survived). For example, Bindusara (an early emperor of India) was reportedly delivered by CS just after his pregnant mother had died by consuming poison. Today, cesarean sections are standard practice in many countries. For example, nearly one-third of all babies are now delivered by CS in some parts of the United States and in particular regions of other countries such as Italy and Brazil.

Factoid: Did you know? Perhaps the world’s oldest pregnant woman—Omkari Panwar—gave birth by cesarean section to twins at the age of 70. (However, lack of a birth certificate for Panwar makes the precise age of her pregnancy less than certain.)

Long before modern medicine, cesarean sections were the stuff of legend. In Greek mythology, Prometheus’s use of an axe to cleave open Zeus’s head (mentioned earlier) could be deemed a rather literal example of a “cesarean section” of a highly ectopic pregnancy. A more conventional type of CS from that era involved the birth of Asklepios, the Greek god of medicine and the son of Apollo. Apollo himself performed this CS after he learned that his beloved nymph, Coronis, had been unfaithful. Enraged, Apollo arranged for the murder of Coronis, but then, in an act of compassion, he removed his son from the dead body of Coronis even as she lay on the funeral pyre.

“Abdominal delivery” via CS was also a recurring topic in several of the world’s prominent religions (van Dongen 2009), including Buddhism (Buddha was born from the right flank of his mother, Maya), Judaism (delivery by a cut in the abdomen was mentioned in the Jewish law, Mishnah), and Christianity (where by some accounts the Antichrist was born via CS and thereby symbolizes the destruction of both mother and child). (Given all the biological mishaps that can occur before, during, and shortly after embryonic gestation in humans, pregnancy indeed might seem like a devil’s playground.) Finally, even Shakespeare used the concept of cesarean section in one of his plots by invoking this poetic phrase: “for none of woman born shall harm Macbeth.” Thus, Macbeth believed he was invincible until, in the end, he is killed by a man (Macduff) who “was from his mother’s womb untimely ripp’d” (presumably by cesarean section, thus rendering Macbeth mortal after all).

This phrase refers to an early onset of puberty for any reason: normal extremes in the wide standard variation of human development or, perhaps in other cases, to overt hormonal imbalances triggered by a pituitary tumor or by some other trauma to a person’s brain or gonads. Typically, puberty is considered at least somewhat early if it occurs in a child who is younger than about 8 or 9 years of age. Otherwise, the time of first menstruation (menarche) for girls in developed Western countries is about 13 years. The onset of menstruation (box 5.2) is an especially important component of female puberty because it signals the beginning of a woman’s effective fecundity. Precocious puberty can make a girl capable of conceiving and giving birth while still very young.

BOX 5.2 Menstruation (Menses)

This is the periodic flow of blood and mucosal tissue from the uterus to the outside of the body via the vagina. In humans, the material expressed normally consists of a few teaspoons of blood plus remnants of the endometrium (the lining of the uterus). Menstruation in a woman occurs on a more or less monthly schedule, lasts 2–8 days, and is often accompanied by cramps (dysmenorrhea), caused mostly by contractions of uterine muscles. Each menstrual period is part of a monthly cycle of hormonal and reproductive changes, during which a haploid egg cell completes its maturation in the ovary and is shed (ovulated) into the oviduct, where it temporarily becomes available for fertilization. Ovulation usually occurs midway through the monthly cycle (i.e., about 2 weeks after and 2 weeks before successive menstruations).

Overt menstruation, which is rare in the biological world, is confined mostly to humans and some of our closest evolutionary relatives, including chimpanzees. Instead, most other placental mammals have covert menstruation, in which a female reabsorbs the endometrium at the end of her reproductive cycle. Anthropologists have speculated on this evolutionary difference, and one has suggested that females with covert menstruation save considerable energy by not having to rebuild the uterine lining for each fertility cycle (Strassmann 1996). But why then do humans have overt menstruation? One hypothesis is that prolonged fetal development in Homo sapiens requires a thick and highly developed endometrium that is too difficult for a female to reabsorb completely (Strassmann 1996). Furthermore, appreciable energetic costs might be associated with having to maintain a uterine lining continuously.

Menarche, in effect marks the beginning of a woman’s fertility, which later ebbs and eventually ends with the cessation of menstruation during menopause. Also, menstruation may be suspended temporarily (a condition known as amenorrhea) during otherwise fertile portions of a woman’s lifespan, such as pregnancy, the period immediately following childbirth, and episodes of exceptional physical or emotional stress or ill health.

Many cultures and religions have special traditions regarding menstruation. For example, orthodox Judaism and Islam discourage intercourse during a woman’s “period,” and some traditional societies construct “menstrual huts,” where women must sequester themselves at the appropriate times.

Factoid: Did you know? The youngest well-documented mother (and successful pregnancy) on record involved a Peruvian girl, Lina Medina, who gave birth by cesarean section at the age of 5 years and 8 months (Escomel 1939). She was estimated to have begun menstruating at 1–2 years of age and had prominent breast development by age four.

“Delayed puberty” resides at the opposite end of this temporal spectrum. Although precise definitions of the phenomenon are difficult because the age of puberty shows considerable variation even in healthy populations, puberty might be considered exceptionally late or even pathologically delayed if a girl fails to experience menarche by the age of 18 or if a boy shows little testicular development by about age 20. Among the possible causes are exogenous factors such as malnutrition or disease and numerous endogenous factors, including genetic disorders or the body’s inappropriate production of or response to sex hormones.

When discussing human pregnancy in an evolutionary framework, perhaps the most widely appreciated fact is the difficulty of childbirth due to the large size of a fetus’s head relative to the birth canal. By favoring an increased mental capacity in our evolutionary ancestors, natural selection seems to have pushed the size of the human brain and cranium nearly to the physical limit, as any woman who experiences the pain of labor’s second stage (fetal expulsion) is likely to attest. Indeed, despite the remarkable dilation of the woman’s reproductive tract (notably the cervix, which is the gateway from the uterus to the vagina) that occurs during the first active phase of childbirth, an obstetrician may later perform an episiotomy or a perineotomy—a surgical incision in the woman’s posterior vaginal wall that enlarges the opening and allows the baby to squeeze through. In addition to the physical challenges of childbirth, the delivery phenomenon has psychological consequences for the mother that can range from great elation to postpartum depression. The relative immaturity and helplessness of human babies compared to the offspring of many other primates are further testimony to the evolutionary premium of keeping babies small enough to pass through the birth canal despite the competing selection pressures for larger heads and brains. As is true in so many facets of human life, successful reproduction under an evolutionary view is an amalgam of oft-competing interests and tradeoffs between opposed selection pressures.

With respect to the difficulty of childbirth, humans are exceptional but hardly unique. In many other mammalian species such as giraffes and other ungulates (hoofed animals), females seem to experience considerable discomfort as they give birth to large or otherwise cumbersome infants. On the other hand, childbirth in many other mammals seems downright effortless. In some marsupials, for example, mothers deliver tiny babies, who then continue much of their development in an external marsupium, or pouch. But bears (Ursidae) provide even better examples of carefree childbirths. Consider, for example, the black bear (Ursus americanus), in which a 300-pound pregnant female gives birth during hibernation (effectively while asleep) to infants so tiny that each could fit inside a teacup. During the winter months, as mom continues to snooze in her den, her cubs suckle and grow from the nutrition that she provides by transforming her thick body fat to milk.

In humans, another component (the third, or final, stage) of a standard vaginal delivery typically occurs within 15–30 minutes of childbirth. It is the expulsion of the afterbirth (i.e., the remnants of the placenta). In Egyptian mythology, the redness of the dawn sky after a dark night was sometimes interpreted as a bloody afterbirth that accompanied the birth of the sun god with each new day.

Factoid: Did you know? Maternal mortality is defined as the death of a woman during pregnancy or in the 42 days postpartum due to causes directly or indirectly associated with the pregnancy. In recent decades, maternal mortality worldwide has averaged about 40 deaths per 100,000 human live births, or more than half a million maternal deaths per year (Hill et al. 2007).

Factoid: Did you know? In many other mammalian species, the mother, after giving birth, bites through the umbilical cord and then eats it and the placental remnants—a feeding behavior known as placentophagy.

During a pregnancy, the human placenta (from the Latin “plakóeis,” meaning flat cake) is a disk-shaped organ on the mother’s uterine wall that attaches to a ropelike structure (the umbilical cord) that serves as a conduit not only for delivering nutrients from the mother to the child but also for exchanging gases (oxygen and carbon dioxide) and eliminating embryonic wastes.

The mammalian placenta is a crucial physical link between embryo and mother. It arises early in a pregnancy as follows (fig. 5.2). After the new zygote has undergone several mitotic cell divisions, the resulting cells separate into two genetically identical subpopulations: the inner cell mass, which eventuates in the embryo, and the trophectoderm, which will form the placenta. Thus, from a genetic perspective, cells of the placenta are identical to those of the prospective fetus, so in this respect the placenta can be deemed the embryo’s identical twin since both share the same cramped womb. From a physiological and biochemical perspective, however, the placenta has both fetal and maternal components that were generated after the blastocyst implanted in the mother’s uterine wall. The placenta grows throughout a pregnancy and produces a succession of reproductive hormones (some constructed from imported maternal precursor molecules) that help to orchestrate the gestational process and direct the embryo’s development (Bonnin et al. 2011). Indeed, some of these hormones (such as placental lactogen or chorionic somatomammotropin in some species) have effects that extend beyond parturition, such as by preparing the mother for postpartum lactation.

Although the placenta is at the maternal-fetal interface, the maternal and fetal bloodstreams do not intermingle directly. Instead, microcapillaries from the two circulatory systems merely come into proximity at the “placental barrier” (near the junction of the umbilical cord and the placenta), where they are so apposed that gases and nutrients diffuse across the barrier.

Factoid: Did you know? The human placenta is nearly 1 foot long, 1 inch thick at its center, weighs about 1 pound, and is maroon in color. The umbilical cord, to which it connects, is about 2 feet long and terminates at the fetus’s “belly button,” the navel.

FIGURE 5.2 The ontogenetic origin of each mammalian placenta and its associated embryo (after McKay 2011). From a genetic perspective, the two can be thought of as identical twins (see the text).

Factoid: Did you know? One of the earliest hormones produced by the placenta is human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a substance whose detection in a woman’s urine provides the basis for commercial test kits for pregnancy.

Because most of the cells composing the placenta are genetically identical to those of the conceptus, both the placenta and the fetus can be deemed foreign tissues that in effect have become allografted inside the dam’s pregnant body. The placental barrier is one of several evolved mechanisms that enable a mother and her embedded newcomer to evade the immunological surveillance systems that otherwise would promote the rejection of such foreign tissue and thereby abort the pregnancy (see chapter 6). Other avoidance mechanisms are physiological (Bainbridge 2000) and include the secretion of special phosphocoline molecules by the placenta and the production of lymphocyte-suppressor cells by the fetus, both of which further help in evading the immunological rejection response. Overall, the placenta is a truly unique and special organ.

Closer to the realm of fiction, the placenta is a complicated structure that holds a varied significance among different peoples. Many Nepalese, Malaysians, and Nigerians consider the placenta (as represented by the afterbirth) to have been a living creature—such as a friend of the baby, a baby’s sibling, a spirit of the baby, or perhaps even a deceased twin. In various other cultures, the placenta and afterbirth are treated with deference. For example, a formal or informal practice in many societies has been to bury the placenta from a newborn in the belief that this might ensure the health of baby and mother, promote a couple’s future fertility, give the newborn special skills, perhaps appease the gods, or otherwise honor the connection between humans and the earth. Regarding various Native North American tribes, the Paiute believed that a placenta buried upside down would lead to woman’s barrenness; the Lummi imagined that throwing the placenta into the swirling water of a river would protect a woman against future conceptions; the Cherokee imagined that burying a placenta several hills away from the birthing site would yield a corresponding several years before the woman might again conceive; and some Kaska women supposed that packing an expelled placenta with porcupine quills might help to alleviate physical pain in future deliveries.

This condition (from the Greek words “mens,” meaning “monthly,” and “pausis,” meaning “cessation”) normally terminates a woman’s fecundity and therefore truncates her potential for standard pregnancy. It is defined as the normal age-associated cessation of menstruation for 12 consecutive months. In healthy women, premenopause (when menstrual periods become irregular and finally stop) usually begins between the ages of 40 and 51. Thus, few women become pregnant and give birth after age 50 (Salihu et al. 2003). However, with the advent of assisted reproductive technologies such as fertility treatments, in vitro fertilization (IVF), ovum donation, surrogate motherhood, cesarean sections, and generally improved medical practices, increasing numbers of older women now are bearing children. Indeed, a number of well-documented reports exist of women beyond the age of 50 and even 55 having assisted or unassisted conceptions and standard or nonstandard pregnancies, followed by either natural or unnatural childbirths. Here are just four of many interesting examples: in 1669 (long before the era of modern medicine), a 54-year-old English woman (Elizabeth Greenhill) gave birth to a naturally conceived child; in 1956, a 57-year-old American woman (Ruth Kistler) conceived naturally (one of the oldest women known to have done so) and later gave birth to a viable daughter; in 2003, a 65-year-old Indian woman (Satyabhama Mahapatra) became pregnant—with the help of IVF, using sperm from her husband and an ovum donated by her 26-year-old niece—and later gave birth by cesarean section to a healthy boy; and in 2010, a 60-year-old Brazilian woman gave birth to her own granddaughter after agreeing to act as a gestational surrogate for her 32-year-old daughter, who was infertile.

Factoid: Did you know? A Russian peasant named Valentina Vassilyev (approx. 1707) holds the record for most children birthed by one woman. She delivered a total of 69 children: 16 pairs of twins, 7 sets of triplets, and 4 sets of quadruplets. Unfortunately, few other details are known of her life, such as her date of birth or death.

Male pipefishes and seahorses routinely become pregnant and give birth to live young (chapter 7), but does this phenomenon ever occur in humans as well? Yes, at least in fiction. One amusing example comes from contemporary society. In the 1994 comedic film Junior, a very manly scientific researcher, Alex Hesse (played by Arnold Schwarzenegger, recent governor of California), becomes pregnant after accidentally taking an experimental drug designed to reduce the chances of a woman having a miscarriage. Alex soon becomes emotionally attached to his unborn baby, which gradually grows to considerable size within his “Arnie’s womb.”

Factoid: Did you know? A few “bona-fide male pregnancies” widely reported in the media have involved transgender humans who were born with functional ovaries and other female body parts but after being impregnated consider themselves pregnant transgender men.

Can a human male truly get pregnant in real life? As the promotional ads for Junior proclaim, “Nothing is inconceivable.” Indeed, in 1992 the tabloid world was shocked by media reports (complete with convincing pictures) of a very pregnant Taiwanese man (a Mr. Lee) who had purportedly volunteered to have an IVF embryo implanted into his abdominal cavity, with the expectation that a full-term baby would later be delivered by cesarean section. Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), the report and the doctored photos turned out to be nothing more than an elaborate hoax. Still, the account prompted much speculation about what might theoretically be possible in the age of assisted reproductive technologies. Assuming that many biological and technological hurdles might someday be overcome, it is perhaps conceivable that some sort of ectopic implantation could produce a “pregnant” man, who carries an embryo internally, at least for some time. However, relatively few men may be eager to explore such possibilities.

Finally, many science-fiction writers have envisioned strange reproductive worlds. For example, in Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, anyone can become pregnant, whereas in Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time, no one becomes pregnant, and, instead, all human gestations transpire in artificial wombs.

1. Pregnancy is a prominent feature of human existence not only in obstetrical practice but also in many of our mythologies and cultural traditions. Much is mechanistically understood about the standard course of real-life events during a human pregnancy, from its beginning with conception and implantation to its conclusion at parturition of the child and its afterbirth twin.

2. Much is also known about various pregnancy phenomena that are somewhat less standard. Some of the atypical expressions of pregnancy that have been documented in humans include the following: extracorporeal fertilization (syngamy at a site other than the normal location within the female’s reproductive tract); superfetation (the co-occurrence of two or more embryos at different stages of development); multibirth pregnancy (the bearing of two or more same-stage offspring that may be either genetically identical [monozygotic] or different [multizygotic or fraternal]); ectopic pregnancy (implantation of an embryo outside the normal uterine cavity); preterm labor, which may yield a “preemie” baby; prolonged pregnancy, which lasts beyond about 41–42 weeks; spontaneous abortion, which terminates a pregnancy prematurely; cesarean section, the delivery of a baby by means of an incision in a mother’s abdomen and uterus; precocious puberty, wherein a female may become pregnant at an unusually young age; and male pregnancy, wherein an apparent man (or more likely a transgender person) becomes impregnated.

3. All of these and other pregnancy-related phenomena are also richly represented in the mythologies, cultural beliefs, and religious practices of human societies, giving further testament to the central position of pregnancy in peoples’ thoughts throughout human history. Many fictitious tales about gestation, though sometimes wildly exaggerated, find recognizable analogues in some real-life human pregnancies.

4. Among many other subjects that arise routinely in discussions of human pregnancy are the following: the placenta and umbilical cord, which physically connect mother and fetus; menopause, which normally ends a woman’s potential to become pregnant; various methods of birth control; and menstruation (menses) and menarche (the time of a girl’s first menstrual period). In many human societies past and present, all of these subjects are deeply engrained in cultural superstitions, folklore, customs, and rituals.