CREATIVITY IS CENTRAL to the investment process, whether it is structuring a unique deal with a borrower, hunting for the elusive diamond-in-the-rough investment, or cleverly determining the optimal capital structure of a business. It is little surprise, then, that the creative process practiced by successful investors was eventually turned not just to the sourcing and creation of investments themselves, but to the very business of investment management.

For most of the twentieth century, larger institutions and wealth management divisions within commercial banking bodies and investment banks primarily drove the world of investment management. Managing investments tended to be a large-scale corporate endeavor, involving the coordination of many individuals across a firm. While these corporate employees were reasonably well compensated, the days of astronomical compensation had not yet dawned. But during the 1970s, investment advisers and money managers began to leave larger institutions in order to strike out on their own. This move toward independence was coupled with an entrepreneurial spirit, and these two forces created the conditions for an era of financial innovation.

As these investment managers became equity owners of their own firms, the industry itself became larger and, in many cases, more lucrative for those who built these new investment management enterprises. These new independent firms attracted a great number of clients, often at significantly higher fees than were prevalent in the past. Within several decades, there was a profound shift in the economics and organization of investment management, which in turn would have a dramatic impact on the future of the industry. This trend toward a greater emphasis on the creation of wealth and true value in investment management expanded the innovative and entrepreneurial possibilities for individual managers.

Despite this sea change, these innovations are in many respects a byproduct of the democratization of investment, for many of the clients for alternative products are larger institutional clients like insurance companies and pension plans, whose assets come from a much wider percentage of the population. However, the investment of these democratized assets in new products and independent firms has also resulted in the creation of vast wealth for a “new elite” in the investment management industry.

INDEPENDENCE AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP: ENVIRONMENT, MOTIVES, AND BEHAVIORS

Economic leaders have long recognized the benefits of enterprise and independent action in producing superior outcomes and returns. Even the early history of agriculture in ancient Mesopotamia reveals the emergence of private farmers contracting with state-owned agricultural entities in order to improve their efficiency. In order to promote the growth and profitability of their operations, the merchant bankers of the Italian city-states, including prominently the Medici, created decentralized organizations and hired nonfamily partners who had wide autonomy. This decentralized management strategy is also followed by many successful modern industrial managers.

Investment management is not very different and has proven to be a fertile field for independence and innovation, attracting many entrepreneurial individuals. In fact, most of the newer styles of investment management developed in the last one hundred years have been created by new independent firms, which often launch entirely new vehicles in order to attract clients with the expectation of superior returns. The 1970s saw the advent of a new entrepreneurial trend in investment management, which was in part due to the rise in large institutional and wealth management accounts, client receptivity to higher fee rates, and growing asset flows. Investment managers left banks, insurance companies, and larger, more established mutual funds, becoming equity owners of their own firms following these emergent trends of independence, especially with respect to managerial incentives and decision-making processes.

At first, independent investment managers primarily dealt with long-only equity strategies for investing. Their management fees, a simple percentage of the total balance of assets they were managing, were arranged with no expectations of large performance incentives or stakes in client profits. Clients, too, had only modest expectations. However, once a critical mass of managers broke away from their firms, the industry began to shift toward creating inherent value in money management for the first time. They began to think as entrepreneurs, focusing on performance and revenue maximization, investment philosophy, style, products, and marketing. The development of innovative investment methodologies, best practices, and personnel management strategies also characterized this trend toward independence. Investment managers, long trained in the craft of assessing the prospects of other firms, became businesspeople themselves.

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 was a key piece of legislation that helped pave the way for independence in investment management. It was passed by Congress in order to set minimum standards for private pension plans.1 Its primary effects on the broader investment management industry were twofold. First, it provided investment managers with freedom to creatively fulfill their fiduciary duty to investors while acting responsibly within the confines of the law. This facilitated innovation by allowing independent managers to invest for higher risk-adjusted returns through a variety of means, most of which still fell under the definitions set forth by the government. Second, by establishing industry-wide standards for the new investment management firms to which it gave rise, ERISA encouraged many more managers to break away from larger institutions and pursue their own endeavors in the investing world. Coupled with the very low seed capital requirements of new investment management firms, ERISA created the conditions under which independent firms could flourish.

This synergy between independence, entrepreneurship, and innovation was highly valued by these newly independent managers for a number of reasons. First, they were able to manage money without being restricted by large institutional protocols and bureaucracy. They had the freedom to perform superior work in terms of making investment decisions and evaluating potential investments. Second, these managers gave priority to their client relationships, or at least they believed that as an independent firm, they could do a better job at this than the large institutions. Managers who broke away often felt that their unilateral focus on clients’ results would prove useful in their independent endeavors, because many Wall Street firms seemed focused too much on firm results rather than on maximizing value for their clients, and this became a fundamental concern for these managers when the two objectives were not properly aligned.2

Clients have often agreed with this insight; many have felt that there are advantages to working with independent investment managers, including the incentives to maximize client gains. As history shows, busy individuals with investable capital have frequently hired money managers who have expertise in investment decision making. While the decision to hire a person to manage one’s capital and investments is largely driven by the demands of time and skill, this motive does not explain why independent money managers would be preferred by the client over traditional institutional managers. However, the new independent firms were indeed promising superior returns and offering innovative investment products, which lured significant numbers of clients away from traditional institutions. A prominent investment adviser once declared that there are two ways a portfolio manager can outperform his or her peers, aside from sheer luck. The first of these is possession of or access to information superior to that which others have; the second is superior capacity to synthesize and draw conclusions from the information that is available to all investors.3 In becoming independent, managers of their own firms strove to maximize returns for their investors, predicated upon the belief that they possessed such exceptional abilities (though at least a portion of the first kind of superior ability has been regulated away by securities regulators around the world with rules and enforcement related to material nonpublic information).

There was no stigma attached to the idea of breaking away from a traditional corporate financial services institution to begin work in an independent investment management firm. Rather, this move was encouraged by the growing culture of entrepreneurship and the allure of greater rewards—both financial and personal—through the means of creating value and wealth in a superior fashion for clients. This entrepreneurial streak continued in the investment management industry, and further innovative trends emerged with the advent of private equity, hedge funds, and other alternative investment managers.

As this independence trend took hold, various money management veterans at large institutions saw the competitive forces they were facing. Many who stayed with larger institutions echoed the independence rationale, advocating for the “relative charms” of leading a separate unit within an enduring, time-tested institution, with its involvement in many markets and a broader mandate than that of any independent management firm. Specifically, one Morgan Stanley investment management executive cited his ability to manage a top-notch investment management unit as part of a larger financial institution with a global brand as a reason for the supposed superiority of institutional money management over independent management. However, as the same executive conceded, the number of managers who have been very successful inside large institutions has been rather small in recent years.4 The forces moving toward independence were too strong for the traditional money management industry to monopolize the new industry paradigm.

Of course, the lack of scale made breaking away more difficult, and asset management firms have a powerful ability to scale on the business side (though not on the investment side, where significant scale can make it more difficult to find pockets of great value). In particular, the back office (compliance, personnel, legal staff, and marketing) tends to scale quite well in asset management. The high scalability of the business means that costs of managing a fund as a percentage of assets under management tend to decline as the asset base grows.5 This scalability made it more difficult for independent asset managers to instantly compete with their already scaled competitors within large institutions, but it also meant that running such independent firms would become less costly with new growth. Fortunately, for some newly independent firms, this scalability was reached rapidly because many clients of independent firms were actually larger institutional clients.

The creative impulse and the desire to move beyond the rigid bureaucracies of larger financial firms may explain why investment managers were eager to offer their services independently, but these factors do not account for why the trend toward independence began in the 1970s. For that, one needs to understand the sources of demand for these investment management services. This growth occurred largely because of demand driven by ever-greater savings for retirement, a subject covered at length in chapter 3. In 1974, retirement assets totaled about $370 billion, equivalent to more than $1.75 trillion in today’s dollars.6 As of the middle of 2014, total retirement assets numbered $24 trillion. Furthermore, IRAs as introduced by ERISA, which have $7.2 trillion in assets, were entirely new in 1974. Defined contribution plans, too, have grown materially in the past forty years as employers have tended to shift away from defined benefit plans, and this pool totaled $6.6 trillion in mid-2014.7

Increasingly since the 1970s, substantial new assets needed to be invested, and doing so typically involved a professional asset manager. In 1980, only 3 percent of American household financial assets was held by investment companies. By 1995, this number was greater than 10 percent, and in 2011, almost a full quarter of household financial assets was managed by investment companies, with retirement assets composing a large portion of the total. Mutual funds in household retirement accounts slowly escalated from 13 percent of retirement assets in 1991 to 55 percent of retirement assets by 2011 for defined contribution retirement plans, and 24 percent of retirement assets in 1991 to 45 percent of retirement assets by 2011 for IRAs.8

These new pools of retirement assets created increasing demand for investment management services, driving the revenues of the entire industry to new heights. It is difficult to overstate just how much growth the investment management industry has seen over this time frame. To consider just mutual funds, for example, the assets under management in equity mutual funds grew 135-fold from 1980 to 2010. The average annual expense ratio for a mutual fund grew by a total of 4.8 percent, so the resulting revenue to the equity mutual fund industry grew by over 141 times, representing a compounded annual growth rate of 17.9 percent.9 Indeed, in just a single generation, mutual funds investing in equities experienced a rate of growth hard to fathom outside of high-tech segments of the economy. At the beginning of the independence trend, these growth rates were impossible to imagine. However, the rates make sense when one accounts for the fortuitous combination of independence and entrepreneurship with the growth of investment assets as a result of the democratization of investment.

THE RISE OF INNOVATION AND ALTERNATIVES

Managers who succeeded in this new entrepreneurial era now included many who invented and exploited new investment approaches, techniques, and products that offered advantages in terms of performance, often at higher fees. The very first clients of hedge funds and private equity firms were those who had significantly more risk-tolerant profiles for their capital. This was understandable, as at the time there were often short, incomplete, or even nonexistent track records of performance for hedge funds or private equity firms. In fact, the justification for investing capital with such firms was largely theoretical.

After a few years, however, the “alternatives” and the innovative investment strategies employed by these new independent money managers started to demonstrate a marked ability to achieve improved risk-adjusted return in some scenarios. One of the very first institutional movers into this segment of alternative investments was the Yale University endowment, headed by David Swensen beginning in 1985. Yale began investing in alternatives shortly into Swensen’s tenure in 1986. With Swensen at the helm, the Yale endowment jumped in value, overtaking that of Princeton and the University of Texas to be second in size only to Harvard University’s. Average annual returns outperformed both the stock market and the average college endowment. Much of this success was driven by increased exposure and capital allocation to private equity, timberland, real estate, and hedge funds.10

State governments, such as that of Oregon, were also early adopters of alternatives. Entities created at the state level, such as the Oregon Investment Council, were mandated with investing all government funds, including those in public employee retirement funds and accident insurance funds, for instance.11 All in all, it is clear that early conversion to alternative investments served the first movers well. Independent and alternative investment managers were to have a bright few decades, and those who got in on the ground level—as with many other innovations—reaped the profits accordingly. Clearly, these first movers were motivated by the prospect of improved risk-adjusted returns. Moreover, several observers of the investment world at the time remarked that traditional long-only investment strategies with stocks and bonds were viewed by some as less appealing than alternative investments, especially when it came time to raise funds or attract new capital into an investment fund. Over time, the first innovators and clients were joined by larger numbers of high-net-worth individuals and retail investors, leading to a correspondingly huge influx of capital into these strategies. Originally fairly simple, the strategies have grown and evolved over the last three decades to become increasingly complex and sophisticated.

In order to understand the “conversion” of investors to independent asset managers in general and to alternative investments in particular, we must fully appreciate the tremendous innovation employed by the creators, such as the private equity industry. Though the private equity investment management industry itself has been treated separately in the alternative investments section of this book, innovation of private equity itself was a truly dramatic inflection point of the entrepreneurial story of investment in the twentieth century. A look at the various strategies employed by hedge funds today, discussed in chapter 8, reveals how quickly fund methodologies aimed at generating superior risk-adjusted returns can evolve and develop. Most of these investment strategies, philosophies, and techniques did not exist even two or three decades ago.

Outcomes: New Clients, Performance Success, and Firm Size

As a result of the good performance of many of the early movers, a large segment of the potential client population became captivated by this success and was willing to pay significantly higher management and performance fees to get into the fray. The appeal of hedge fund and private equity firms soared, even as public scrutiny and media criticism of these alternative investment vehicles increased as well. By the 1990s, investors, clients, and competing managers were all captivated by the potential success an independent manager could achieve, both in terms of performance for the client and compensation for the manager.

One central commonality among the independent firms that demonstrated remarkable performance in the early 2000s is the relatively smaller size of successful managers. Economic theory and past academic consensus suggest that larger asset management companies would benefit from economies of scale in technology, distribution, hiring, and legal issues, as noted earlier. However, becoming too large sometimes disadvantaged the investor or client when it came to performance, because performance of investments often does not scale in the same way as costs do, as discussed in the context of hedge funds in chapter 8.12 Perhaps the most important reason for this is that smaller investment management firms can often exploit undercovered or more esoteric corners of the market. These may include smaller securities in complicated situations that cannot accommodate exceptionally large investments. When a firm grows too large and needs to invest beyond its core areas of expertise, where its edge is not as pronounced, returns may drop.

Very few areas within the financial services economy prospered in the immediate aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Independent asset management, however, was absolutely one of them. After the crisis, some high-net-worth individuals and wealthy clients moved to independent asset managers in order to avoid the tarnished reputations of many large institutions.13 Some of this was likely a reaction to revelations that some investment banks were selling to their clients the very products they were betting against with proprietary capital. At this stage of the game, of course, the rise of independent managers was well underway, and the independent asset manager was a major player in the financial services realm.

Independence Becomes Mainstream

A look at America’s top 300 money managers in terms of assets under management at the end of 2013 reveals the extent to which independence has defined success in the world of money management. In fact, four of the eight largest money managers in the United States fall under this “independent” classification if we define independence to include the following: unaffiliated mutual fund managers, independent investment advisory firms, largely manager-owned investing firms, and today’s private equity and hedge funds (excluding large investment and commercial banks and departments within these institutions, such as bank trust departments, institution-owned hedge funds, quasi-independent advisories, and bank-controlled wealth managers).14

The largest firm in terms of assets under management is New York–based independent asset manager BlackRock, which controls $4.3 trillion. The second-largest is Boston-based State Street Global Advisors, which manages $2.3 trillion; but since it is under the control of State Street Corporation, a large institutional financial services firm, it is not an independent investment manager. Next on the list is the independent Vanguard Group, with over $2.2 trillion in assets under management.15 Clearly, with two of the top three investment management firms in the United States classified as independent asset managers and together controlling over $6.5 trillion in assets under management, independent managers have come to define the very nature of investment management today.

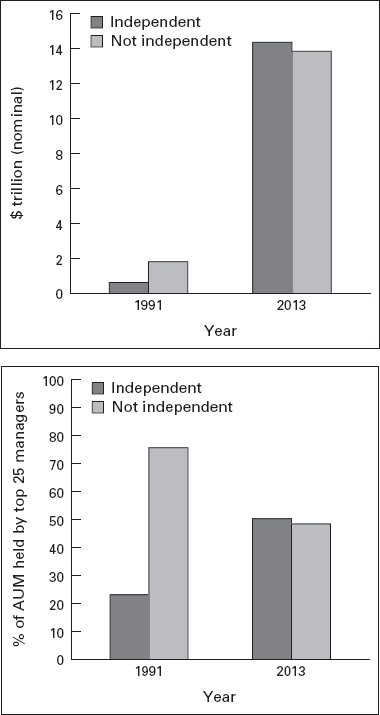

In fact, comparing independent asset managers with affiliated asset managers by taking a closer look at the list of America’s top money managers from today and years past, as compiled by Institutional Investor, reveals some interesting insights. For example, in 1991, the proportion of assets managed by independent managers among the top twenty-five money managers in America was at 24 percent. The next two decades, despite major global macroeconomic uncertainty in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, saw a dramatic uptick of inflows into independent asset managers when it came to the top twenty-five money managers in the United States. By 2013, 51 percent of assets among the top managers were managed by independent firms (see figure 9.1).16

This trend, at first glance, suggests that independent asset managers are gaining popularity among clients and that capital inflows are favorable. Moreover, while many large banks and traditional financial institutions, such as divisions of Goldman Sachs and J. P. Morgan, are present in the top rankings of money managers by assets under management, most of the top three hundred asset managers are independently owned and managed entities.17

Figure 9.1 Title: Assets Under Management, Top Twenty-Five US Managers

A wealth of data exists surrounding the dramatic surge in popularity of independent asset managers, indicating that the era of independent asset management is here to stay. Thus, innovation in investment management methodologies and in the organizational approach of independent investment firms laid a strong foundation for the independent investment managers of the twenty-first century.

A Contrary Movement: Market Efficiency and Indexing

While independent managers were breaking away from larger financial institutions and finding success in their own money management enterprises, a parallel movement driven by efficient market theorists and the phenomenon of indexing emerged. Indexing is the investment strategy of passively tracking collections of stocks and bonds that are represented in indices, or collections of firms that benchmark certain parts of the market. Two schools of thought on indexing and market efficiency have existed. The first, to which many of the independent investment managers presumably subscribe, is that active management can indeed add value for clients and investors in the medium and long term and that there is significant alpha to be gained over indexed investment portfolios.

The second, to which adherents of the market efficiency movement belong, holds that active management in the long term is usually not fruitful and that in general the capital markets are quite efficient in terms of pricing. Because of this, it has been significantly cheaper and much more productive for investors to select indexed vehicles. Some in this camp believe the origins of some of the best track records of active managers are produced by survivorship bias; that is, there are many failed investors for every great investor, and what separates greatness from failure is often luck or fortunate market tailwinds.

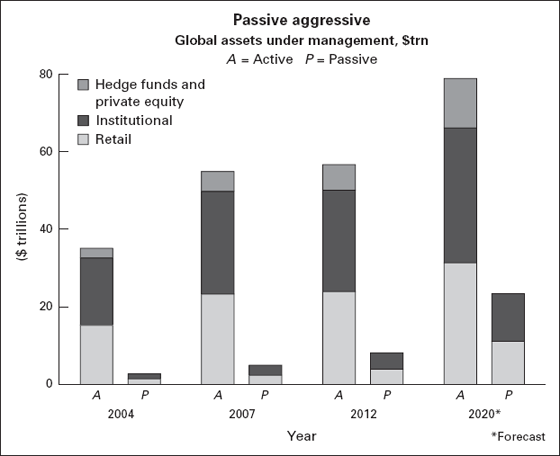

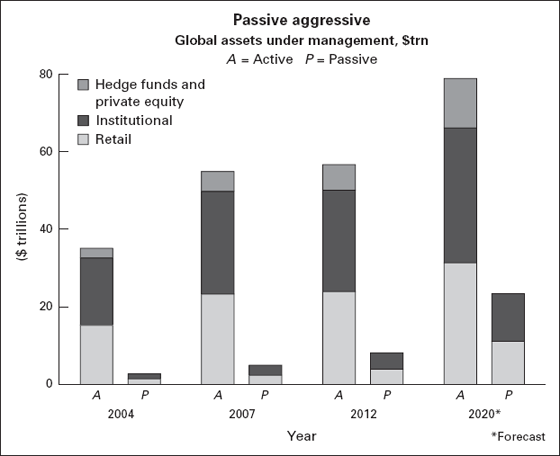

The fees on “tracker” or “passive” funds, which make no claims to beating the market and simply try to replicate it in most instances, are just a few basis points (hundredths of a percentage point)—a far cry from the “2 percent and 20 percent” being charged by active hedge fund and private equity managers in the independent investment management world (see figure 9.2). High fees can be a significant drag on compounded returns over time. One noted observer points out the dangers of such high fees and the potential benefits in investing in index funds by noting that investing $100,000 for thirty years at 6 percent, with annual charges of twenty-five basis points, and a portfolio will be worth almost $535,000; if the annual charges are higher at 1.5 percent, the portfolio will be worth only $375,000 after the thirty-year period. One prominent industry report in 2014 estimated that low-cost index funds, which appeal to those who believe in this alternative school of thought about market efficiency, were on track to experience a 100 percent increase in their market share globally by 2020, from 11 percent to 22 percent.18

Figure 9.2 Passive Aggressive: Global Assets Under Management, $Trillions

One analysis by the Economist in May 2014 argued that this more recent change—the shift toward more passive management—is happening for several reasons. First, more advisers are being paid fees by their clients rather than taking commissions from fund providers with whom they invest clients’ capital. This approach aligns client and adviser incentives more appropriately and enables advisers to recommend a low-cost index fund or ETF, for instance, over a similarly exposed actively managed fund that might have higher fees. Second, “smart-beta” funds that use different metrics to assemble custom indices (aside from, for example, the classic market capitalization–based indices) have started to emerge and have grown in popularity. Finally, defined benefit pension plans are shrinking in terms of total managed capital and are giving way to defined contribution plans for retirement, thereby somewhat reducing the rate of growth of pension fund allocations to alternatives from what would have been the case if this rotation from defined benefit to defined contribution were not underway.19

Over the decades, the efficient market and indexing school of thought has experienced varying fortunes; with the performance success and enthusiasm generated by alternative investment managers and the subsequent “validation” of active management, some subscribers to this school fell away and paid the higher fees for the chance at higher return. However, the key is that the performance of passive indices is entirely a function of the market beta, or risk premium of a given asset class or other systematic strategy, rather than the active security selection of a manager, while superior performance by many alternative strategies is proving difficult to maintain over time.

Reward: Vast Revenue Growth and Wealth Creation for Investment Managers

Efficient market theory implies that no manager should be able to achieve outsized risk-adjusted returns consistently over time without a fundamental informational advantage, and much of the academic work regarding the performance of index funds, ETFs, mutual funds, and other investment vehicles discussed in this book seems to validate this thesis. However, this body of work seemingly fails to explain the phenomenon of a limited number of real-life, individual, independent money managers consistently beating the market or posting superior risk-adjusted returns year after year, at least for an extended period of their careers. It is worth turning our attention for a moment to the “ultrasuccessful” investment managers who have accumulated vast wealth and influence. In March 2014, the total number of American billionaires stood at 512. The total number of American billionaires in finance and investments was 128, meaning that they composed 25 percent of the total billionaires in the United States. This is, of course, in an industry that employs far less than 1 percent of the country’s workers. The investment manager proportion of billionaires has been steadily increasing over recent decades, according to Forbes. This subset of American billionaires includes those whose primary means of accumulating wealth are listed by Forbes as investments, hedge funds, leveraged buyouts, private equity, and the like.20

The compensation arrangements that exist in the investment management world today are interacting with tremendous growth in investment assets under management and the changing business and legal structures that have allowed alternative investment vehicles to proliferate. These conditions serve as the primary means for their owners, shareholders, and executives to become part of a new elite. The rise of a new money-managing elite is also dependent on a variety of fee types and structures. While the compensation arrangements vary when it comes to hedge funds, private equity, mutual funds, and other vehicles for investment, there are management fees, performance fees, expense fees, event-based fees, carried interest, and other sources that all add to the potential compensation of an asset manager.

Management fees, or fees on assets under management, are period-based fees driven primarily by the size of the fund involved. These fees can vary from a few basis points to a few percentage points. A typical hedge fund fee structure is “2 and 20,” or 2 percent of assets under management for the management fee and 20 percent of profits generated for clients by the manager for the performance fee. For a hedge fund, performance fees are also period-based fees, driven primarily by the return generated by a manager in a given period, usually a calendar year. For a private equity firm, the performance fee is levied on the returns of a given fund vintage and is typically subject to a hurdle, which is a minimum return the fund must post before the general partner is entitled to receive the performance fee. Expense fees are also period based and driven by the operating expenses of a fund or investment management firm. Active managers often charge high expense fees, whereas passive managers and some mutual funds can charge lower expense fees. Transaction fees are event-based fees driven primarily by the size of a transaction undertaken by a manager. Brokers and prime brokers generally charge small transaction fees for the individuals or firms engaging in securities transactions with them.

Soon, it was widely realized that the most compelling economic opportunity for an individual was to become one of the “hedge fund masters of the universe.” Indeed, in 2010, the twenty-five highest-earning hedge fund managers combined made in excess of four times what all five hundred CEOs of the S&P 500 index companies earned combined. As recently as 2012, for instance, the ten highest-earning US hedge fund managers made over $10.1 billion in earnings from management and performance fees. The ten highest-earning corporate CEOs, by comparison, made a “mere” $380 million.21 These years of astounding compensation were not new. Well before the financial crisis, the average top twenty-five hedge fund manager made upward of $100 million a year. In 2007, just before the crisis, the average figure made by this super elite crowd was upward of $1 billion. In 2012, this figure stood at a relatively smaller but still huge $540 million.22 To be fair, it is difficult to determine precisely how much the individuals themselves are earning, because some earnings may be shared with their teams.

No matter how one examines these compensation figures, it is indisputable that in the world of hedge funds, the performance incentives given to the most successful independent hedge fund managers have created a new elite. The rewards given—through voluntary contracts with investors—to the top hedge fund managers have driven vast fee and revenue growth for many independent investment managers in recent years, and this phenomenon seems far from over.

One should keep in mind that the earnings figures reported here are entirely cash compensation numbers; an examination of net worth increases in 2013, for example, including gains made in the value of equity owned and traded on the open market, shows that different individuals are on the list of highest earners. Warren Buffett, the acclaimed investor, tops this list, making on average $37 million a day in 2013 without being a traditional 2-and-20 percent hedge fund manager on the capital appreciation of his Berkshire Hathaway stock.23 The other members of this elite cadre are primarily founders of now-large companies, whose market capitalizations increased dramatically in a year in which the S&P 500 stock index rose more than 30 percent.

In 2012, the highest paid hedge fund manager posted net returns of nearly 30 percent in his flagship fund and personally made $2.2 billion.24 From one perspective, this income was well deserved for a manager who tremendously outperformed the stock market and the average hedge fund. From another perspective, however, the manager’s clients were paying him a vast sum that may be inconsistent with the work required to achieve it.

Only very recently has discussion emerged about curtailing these remarkable earnings. For instance, in some cases investors have been able to push the average hedge fund asset management fee down from the traditional 2 percent of assets under management to 1.5 percent across a number of top asset managers. Even so, many hedge funds and publicly traded private equity firms are generating more and more of their revenue from fees even as this percentage goes down and do so because of the continuing increase in assets under management attracted to their strong returns in a zero-interest-rate environment.

This situation has created a remarkable dilemma for some asset managers: should they focus on maximizing returns or on increasing assets under management? Doing the first certainly helps achieve the second, as more investors will try to participate in a fund with a good track record. However, the managerial compensation incentive structure can become skewed because managers will often focus excessively on maximizing assets under management at the expense of returns—spending days on end meeting potential clients, for instance, rather than focusing on investment diligence and valuation.

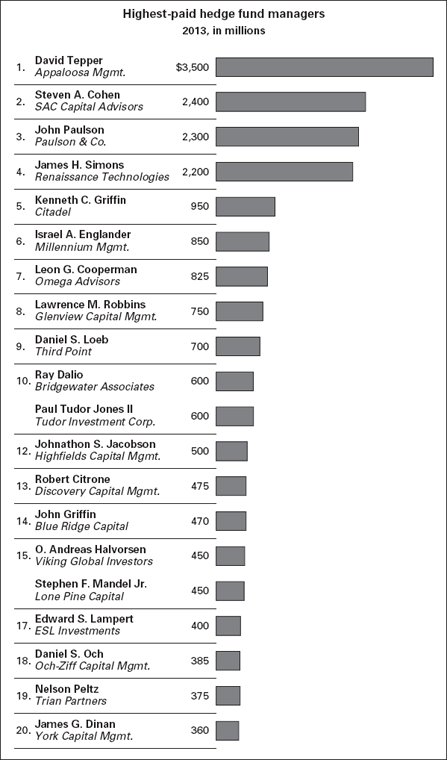

In May 2014, the trend of top hedge fund managers becoming wealthier and wealthier was confirmed: the top twenty-five most highly compensated hedge fund managers earned $21.15 billion in 2013. This compensation figure is the largest such amount since 2010, and it represented a 50 percent increase in top hedge fund manager compensation from 2012. The manager who topped the list earned $3.5 billion, an amount that is $1.3 billion more than the top 2012 compensation (see figure 9.3). This increase was partly driven by a return of 42 percent to investors in two of his funds, which carry the typical fee structure described herein.25 These returns were outstanding, but it is worth noting that not all of the returns achieved for investors by these top hedge fund earners were outstanding relative to the performance of widely followed market indices.

Figure 9.3 Highest-Paid Hedge Fund Managers

The year 2013, however, was the fifth consecutive year that, on average, hedge funds fell short of the performance of the broader stock market. This seems surprising for an asset class whose value proposition is to outperform the market in both good times and bad. The average hedge fund returned 9.1 percent in 2013, according to industry-tracking firm HFR after analysis of over 2,000 portfolios. In comparison, the S&P 500, one of the broadest American equity market indices, returned 32.4 percent after including dividends paid by component companies.26 To be clear, it is not entirely fair to compare the returns of hedge funds directly to the S&P 500 for two reasons. First, the S&P 500 simply represents a single asset class (US equities), and hedge funds often have exposure to a wider array of asset classes. Second, hedge funds typically have a different (and usually lower) beta than the S&P 500 by virtue of hedging or having exposure to lower correlated asset classes through distinct strategies, and thus for the most meaningful comparison one must compare risk-adjusted returns rather than total returns. Still, the comparison does hold in general terms with respect to the large performance discrepancy. Despite this lackluster performance record as compared to the broad equities market, record amounts of capital continue to flow into the hedge fund industry.

In recent years, the private equity industry compensation vehicle of carried interest (the profit share paid to the manager for performance) has also been the subject of much scrutiny. As a complex tax issue, carried interest has often been described as the primary means by which asset managers—including both private equity managers and hedge fund portfolio managers—rake in large amounts of compensation.27 Because carried interest and performance fees represent the majority of the large sums earned by the top-performing independent asset managers, the taxation of carried interest has become a controversial political issue. Currently in the United States, carried interest has been defined as a capital gain for individuals receiving these payments, and as such it has been subject to materially lower capital gains tax rates. Supporters of characterizing carried interest as a capital gain argue that this policy encourages productive investment and economic growth. Detractors point to relative tax burdens and the undermining of a progressive taxation system. Whatever the relative merits of these positions, it is indisputable that carried interest and its capital gains treatment are certainly contributing to the rise and continued financial success of this new elite.

THE COMPENSATION STRUCTURE AND ITS NUANCES

The Problem of Bundling Beta and Alpha

Performance fees are almost always paid on return, not alpha. Alpha is the amount of risk-adjusted value, relative to the appropriate benchmark, that a manager has added through investment management talent—that is, through some combination of security selection, timing, sizing investments, or risk management. However, the return of a fund is a function of both the alpha and the beta. To give an example, imagine a long-biased hedge fund (meaning a fund that may do some shorting but tends to be “net long” the market), and imagine that because of this long bias its investments tend to move up, in aggregate, 60 percent of what the market moves up. If the market moves up 20 percent in a given year, the fund is expected to move up 12 percent from beta, or just by virtue of its market exposure. Assume that despite the market’s move upward, the manager did not add any alpha and returned only 12 percent that year. In a traditional hedge fund, the investor would still owe 20 percent of the 12 percent move as a performance fee, leaving the investor liable for a 2.4 percent payment to the investment manager for beta alone.

However, the investor could just as easily have purchased that same market exposure by buying an equity index like the S&P 500 for a negligible fee. This is, in effect, the first problem with the performance fee: it is paid on a bundle of alpha (the manager’s value-add) and beta (the market return), whereas it would be more logical for the fee to be paid on alpha alone to represent the excess returns the manager generated. This problem plagues investors in funds that tend to have significant market exposure, like long-biased funds, private equity funds, commodities funds, and sector funds that tend to run net long. There should be a greater attempt by the manager and the investor to agree upon a benchmark and a methodology for calculating alpha such that the manager is paid only for “outperformance.” To be clear, there are times when this would be advantageous to the manager too. If a fund is long biased, for instance, and the market moves down sharply but the manager is down less than the beta would suggest, the manager has outperformed and should be rewarded accordingly. The goal is to align the incentives of the manager and the investor appropriately such that the performance fee is paid according to how much the manager beats the market and not on market return, because an index that has the desired beta can be purchased much more cheaply through index funds or ETFs or through holding securities directly.

Fees as a Misleading Proxy for Quality

There is a comical corollary to the fact that the alternatives market standard is the 2-and-20 fee regime: if a hedge fund or private equity firm charges fees substantially below market in order to bring its compensation system into a fairer alignment, many investors will question this move. What is wrong with this group that it cannot charge full fees? Why is the manager leaving money on the table if it is otherwise competent enough to charge full fees? Usually, a fund offers below-market fees because it is a new fund launch or perhaps because the previous funds (in the case of a private equity firm) did not perform very well.

In this regard, there is a curious similarity between investment managers and, for example, surgeons. Imagine needing to have surgery performed for a dangerous medical condition. An individual may check various hospitals, receiving consultations and arranging for approximate quotes on what the surgery may cost. Consider the case where the individual receives the following price quotes from different doctors: $60,000, $55,000, $70,000, and $20,000. Unlike the market for many goods and services, the individual is unlikely to pounce on the opportunity to employ the low-cost provider. This is a service that requires a highly skilled practitioner, and without being a surgeon himself, the consumer has a very limited ability to make judgments about the relative skill and expertise of each surgeon. Therefore, the individual is inclined to believe that there must be a reason the fourth surgeon is so inexpensive—perhaps the surgeon has had poor surgical outcomes resulting in fewer patients, requiring discount prices to draw new patients, or insufficient training and experience to allow the surgeon to compete with more highly skilled and expensive surgeons. Thus, for some investors, price is seen as a proxy for quality. This may also mean that there may not be very high price elasticity among investors; thus, if a manager lowers fees dramatically, the fund’s assets may not scale to the point where it is value additive to do so. In short, in this market, price discovery is an enormously difficult task, and those managers who cut fees materially are often met with reactions of suspicion or unease.

The Performance Fee as a Call Option

Furthermore, the performance fee is essentially a call option. That is, the manager receives 20 percent of the upside and none of the downside, so the fee has the same characteristics as a call option struck at the fund’s net asset value (with a strike price resetting at the high-water mark each year). One of the determinants of the value of an option is volatility because the higher the volatility of the underlying assets, the more valuable the option. Managers are, in theory, financially incentivized to have higher volatility, as their expected payout tends to increase. In other words, there is an incentive to make riskier bets. To be clear, most managers are careful stewards of capital. Indeed, over the long term, it is rational for them to be because a significant drawdown can mark the end of a fund and damage the reputation and career prospects for the team involved. However, when looking at performance fees as a call option, managers who are not careful financial stewards could be tempted to take larger bets because “heads I win, tails you lose.” Investors may thus need to pay attention to how much of the manager’s own capital is in the fund and whether risk-control measures are well developed and properly overseen to ensure proper alignment.

An Implication of High Fees: Competitiveness of Alpha and the Brain Drain to Investment Management

Besides providing extraordinarily high compensation to the heads of the most successful firms, these fee structures have other effects on the labor market. Other employees of the firm on the investment team also enjoy very high levels of compensation. Therefore, successful investment management firms have the ability to attract top talent. Decades ago, the prevailing joke was that it was the “dumbest son” who would go on to manage the family’s money because the job seemed dull and unchallenging. Today, to the contrary, investment management firms attract very accomplished individuals with physics, mathematics, statistics, and other technical backgrounds. Others simply pay top dollar for brilliant individuals who can do deep fundamental or statistical analysis. It is no surprise, then, that 15 percent of Harvard College graduates reported plans to enter finance immediately after graduation in 2013. This percentage is actually in decline, compared to the 2007 rate of 47 percent, prior to the 2008 financial crisis.28 To be clear, the “finance” umbrella is much broader than just investment management and includes positions in banking or some corporate finance jobs. A brain drain is indeed underway; individuals who used to become scientists, doctors, engineers, and mathematicians are now migrating toward finance.

Some individuals, like Michael Mauboussin (the head of Global Financial Strategies at Credit Suisse), think an interesting phenomenon may be at play in the investment management industry. Mauboussin discussed the work of Stephen Jay Gould, who analyzed why Ted Williams was the last Major League Baseball player to have a batting average exceeding .400. According to Gould, the quality of pitching has become better over time, which means that the level of competition is also higher. At least some part of Ted Williams’s success, as phenomenal a player as he was, was because he was a big fish in a smaller pond. That pond has now become filled with other big fish, and the dominance of one player over another has thus been reduced. Mauboussin points out the irony here: “Absolute skill rises, but relative skill declines, leaving more to luck.”29 Likewise in the financial industry, it may be more difficult for individuals to outperform the average as the talent and skills of all managers are rising as the industry pays more to attract top talent.

Performance versus Fees?

Several questions emerge regarding the relative performance of various subsets of independent investment managers. For instance, are hedge funds adding value for their clients in aggregate, net of fees? Do private equity firms continue to generate superior risk-adjusted returns, or is the growth of private equity as an investment vehicle merely an influx of capital into an asset class that temporarily outperformed by accepting illiquidity when the premium for doing so was large?

Alternative investment managers today are enjoying a tremendously attractive compensation scheme in an era where returns for clients, net of fees, are not nearly what they were in earlier periods. The average hedge fund and average private equity firm are certainly not currently outperforming basic market measures of absolute return, and even many of the top performers are outperforming only in certain years and on an inconsistent basis.

Given these results, why does the marketplace support 2-and-20 fees? One contributing factor is the asymmetric process of setting fees. When clients really want a particular manager to run their money, few management or performance fees seem to be considered too high. The investor is excited about the manager, the strategy, and the prospective alpha. Conversely, when clients decide that a manager’s performance, service, or investment style no longer fits their desires, they will not pressure the manager to lower the fees he or she is charging but will instead fire the manager and move capital elsewhere. The investor is dismayed and disillusioned because the strategy did not work, the manager did not execute, or the market soured. These reasons cause any initial excitement the investor may have had to dissipate, and the last issue on the investor’s mind is reducing fees, which are seen as negligible relative to the subpar returns earned through the manager in the first place.

Thus, if one views the investment management fee market through the lens of traditional neoclassical economics, there is far less downward pressure on fees than one would think the basic laws of supply and demand should dictate. In this sense, the manager is the price setter and the client is the price taker. Clients who fall out of love with a manager and want to take their business elsewhere do not become price setters; rather, they shop around for a new manager instead of negotiating a lower or more advantageous fee structure. Thus, managers remain price setters in the industry. This dynamic has contributed a great deal to the rise of the new elite and the simultaneous decline in relative value for the end-client.

The other issue at play is the “easier” pools of capital that managers are able to capture. Certain very large institutions, from pension plans to sovereign wealth funds, have a strong need to allocate large amounts of assets in a short time frame and have to spend more of their limited resources identifying new opportunities than negotiating fees. Many times, these pools of capital do not put substantial pressure on managers to make their terms more client-friendly. If there are enough such investors a manager can capture, the manager has little interest in seeking capital from institutions that attempt to drive hard terms. These easier pools of capital effectively diminish the ability of other institutions to drive the proverbial hard bargain with a manager.

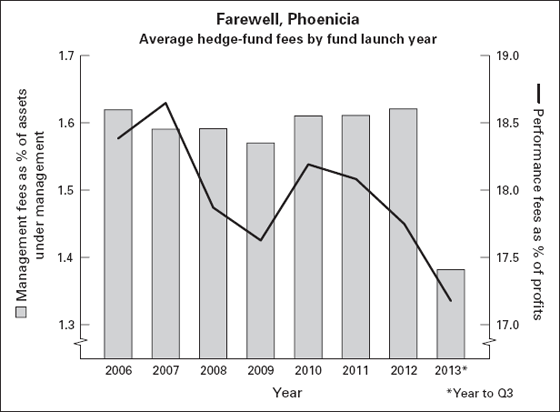

This situation, though, does seem to be improving over time. There are more sophisticated and better resourced pools of capital that are learning to drive fees. Although it is difficult to generalize, there is some evidence of fees slowly ticking down to the order of “1.4 and 17” instead of “2 and 20,” as figure 9.4 illustrates. Some observers attribute this not only to the relatively low returns alternatives have provided in recent years but also to this increased investment savvy leading to greater negotiating power exercised by newer alternatives clients. The 2 percent management fee seems to be under the most pressure.30

Figure 9.4 Farewell, Phoenicia

There is, though, one other source of downward pressure that is probably underappreciated: the systematization of alpha delivered at lower prices. Recent years have also seen the systematization of once “secret-sauce,” alpha-generating strategies that previously required great specialization to achieve. For instance, merger arbitrage or momentum investing strategies were relatively rare before the late twentieth century, when hedge fund managers and others identified the alpha-generating potential of such methods. Now, after the turn of the twenty-first century, more capital flows into such investment strategies as a direct result of their success in creating value for investors. As a result, generalist portfolio managers are able to create funds around such special, historically successful strategies and capitalize on their mass-market potential. Also, multiproduct firms sell exposure to such strategies at lower fees than the standard 2-and-20 arrangement. Indeed, in recent years, merger arbitrage mutual funds have emerged, again attesting to the cheaper delivery of a once rare, sophisticated strategy. Hedge funds in particular will have to compete with these lower-cost providers of hedge fund–like alpha strategies in the future. Of course, the proliferation of a successful strategy that lowers fees may also impair its alpha by creating a growing pool of competitors.

CONCLUSION

It is clear that the second half of the twentieth century was of great importance in the history of global investment management. Investment management was thoroughly revolutionized by the creation of a class of independent investment managers who harnessed an entrepreneurial drive in order to produce sophisticated and innovative products. The rewards for this independence came to managers and clients alike: high-quality products for clients, the value added by particular managers, improved investment returns, and freedom to manage creatively. On the entrepreneurial side, issues of organizational leadership, profitability, business management, and microeconomics all contributed to the success or failure of individual independent managers.

Though the era of independent investment management began with individual managers breaking away from larger financial institutions, today’s world of independent money management has a clear winner, at least in terms of compensation: the hedge fund and private equity “masters of the universe.” These members of the new elite not only have benefited supremely from the last decades but also will probably continue to thrive in the future, as compensation trends and growth rates remain in only moderate danger of decline.

As the long history of investment through the ages seems to indicate, it is probably not possible to devise a single superior investment technique that works era after era after era. Like so many important innovations in the history of investment and investment management, competition and changing market conditions eventually moderate such high performance rates. However, this seems not yet to be clear to the client in the modern money management world—the limited partner (that is, the investor) of a hedge fund or private equity firm seeking to perform supremely well in all periods. Managers—those who consistently outperform and perhaps even those well-organized firms who do not add significant value for their clients—may continue to be well compensated, barring major changes in fee structures or introduction of exogenous downward pressure on fees to relieve the asymmetry issues discussed in this chapter. Thus, this era of vast earnings by top investment managers, while likely to moderate slowly over time, is unlikely to disappear completely.

At the end of the day, though, the next generation of financial innovations will likely take the spotlight. The changes may occur in niche corners of the market, like algorithmic trading, commodities strategies, or real assets, or they may involve a holistic approach like the endowment-style or multistrategy firm. Only time will tell what financial innovations the future holds.