CHAPTER 31

The staff experience: 1867–1939

Nicholas Flood Davin’s 1879 report to the federal government on the future of residential schooling in Canada recommended the creation of a system of church-run schools. He described the existing church-operated schools as “monuments of religious zeal and heroic self-sacrifice.” He believed that because the religious schools were staffed mostly by missionaries, the government would gain access to a low-cost and highly effective labour force. In his mind, each school employee would be “an enthusiastic person, with, therefore, a motive power beyond anything pecuniary remuneration could supply.”1

The government accepted his advice. As a result, the story of the people who worked in the residential schools from 1867 to 1939 cannot be separated from that of the religious organizations for which they worked. At one point during this period, four distinct churches operated schools in Canada. These schools were administered by a variety of missionary organizations, and, in the case of the Roman Catholics, the schools were staffed by the members of several, different, Catholic religious orders.

Each school was a miniature society, often with more than twenty employees. In addition to teachers, there were cooks, seamstresses, housekeepers, matrons, disciplinarians, farmers, carpenters, blacksmiths, engineers (to operate the heating and electrical generators), shoemakers, and even bandmasters. In 1930, there were eighty schools in operation. Although many of the school staff stayed for decades, complaints of high staff turnover were common. It is clear that thousands of people worked at residential schools during this period. They came for a variety of reasons, many staying for only a short time, while others lived the rest of their lives in the schools. Given all these variations, it is possible to present only a sketch of the staff of these schools.

This chapter opens with a description of the various motivations that drew people to work in residential schools, and is followed by a discussion of the Protestant and Roman Catholic missionary organizations that recruited and supported the residential school staff. The chapter pays particular attention to the role that women played in the history of these organizations, and attempts to give some sense of the experience of working in a residential school. Life in close quarters both generated tensions and served as the basis for long-lasting relationships, not only among different members of the staff, but also between staff members and students. The chapter also profiles some of the Aboriginal people who worked in the schools, and concludes with a survey of the critiques of residential schooling that were developed by some of the people who were involved in operating the system.

Motivations

A discussion of residential school staff has to begin with an understanding of the schools’ religious mission. At any given time during this period, almost all the schools were run under the auspices of one of four Canadian churches. While the government had the right to approve or reject the appointment of school principals, the churches had the right to nominate the principals. The churches also usually had responsibility for hiring all additional staff (this was not necessarily the case in the early industrial schools). Each church sought to employ only members of its own faith. For example, at the Anglican schools, every staff member was expected, “so far as circumstances will admit,” to be a member of the Church of England and to attend daily prayer services.2

It is not surprising, then, that most of the early school staff members believed they were participating in a moral crusade. In her history of the McDougall Orphanage, the predecessor of the Morley school in Alberta, Mrs. J. McDougall recalled that during the twelve years her husband managed the institution, he was often “greatly worried and the financial burden upon him was heavy and we as a family underwent many times great sacrifice.” She described the work of the mission and orphanage as “going out after the wild and ignorant and bringing them into a Christian home and blessing the body, culturing the mind and trying to raise spiritual vision.” She felt the work justified the sacrifice. It was, she felt, “good work and surely it must be blest.”3 Given the health conditions that prevailed in many communities and schools, the missionaries assured themselves that even if they could not save lives, they could save souls. Writing of her time as a matron at the Anglican school in Fort George, Québec, Louise Topping recalled how “many a night she stayed up to watch a child with feverish hands and head as they clung to her and she counted the last dieing [sic] breaths. Even in death they were wonderful Christians and would say Jesus was waiting for them and say they were glad to go to him.”4

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was a common belief among Protestant leaders that the Canadian nation could serve as the basis for God’s kingdom on earth. This nation was ideally white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant. They also believed that the character of this nation was under threat from French-speaking Catholics in Québec, and from European immigrants. If Canada were to achieve its mission, these people, along with Aboriginal people, had to accept the benefits of Protestant civilization and become assimilated.5 For such Protestant men and women, devoting oneself to residential school work was a way of helping Canada fulfill a divinely ordained mission.

Some believed it would be possible to evangelize the world in a generation.6 The completion of this task of conversion would be the prelude, they expected, to the day of final judgment. Victoria Roman Catholic Bishop Charles John Seghers believed the Inuit of Alaska were the last people on earth who had not heard the Christian message. He expected that their conversion to Christianity would usher in the second coming of Christ. In order to bring about this conversion, Seghers undertook a poorly planned and poorly provisioned expedition to Alaska. It did not result in the second coming, but rather in his own tragic death.7

Most missionaries had more mundane motives. Alarmed by deteriorating health conditions in many Aboriginal communities in the late nineteenth century, they believed that without their assistance, Aboriginal peoples could not survive the disease, poverty, and dislocation that followed upon their contact with European societies. As W. H. Withrow, the editor of the Canadian Methodist Magazine, wrote in 1875, although the supplanting of a weaker race by a stronger one was “a step towards a higher and nobler human development,” the incoming Europeans had assumed new responsibilities, having become “wardens to those weak and dying races.”8

Although these views may have been based on ‘good intentions,’ those intentions were forged in Europe and implemented without any consultation with Aboriginal people. Such a strong belief in the rightness of their intentions and the divine nature of their mission suggests that the missionaries—and, by extension, the people who founded and operated residential schools—were convinced of their own cultural and, often, racial superiority.

As a young man, T. B. R. Westgate had worked as a missionary in both Paraguay and German East Africa.9 Of his experiences in Africa, Westgate wrote that “the vanity and impudence of the educated nigger … passes comprehension. There is no more contemptible or despicable production under the sun.”10 Westgate went on to play a leading role in the operation of the Anglican residential schools in Canada from 1920 to the 1940s.

One finds echoes of these racially laced thoughts in the writings of prominent school officials well into the early twentieth century. Brandon, Manitoba, principal T. Ferrier in 1903; Mount Elgin, Ontario, principal S. R. McVitty in 1913; and Kuper Island, British Columbia, principal W. Lemmens in 1915—all used the word “evil” in describing tendencies in Aboriginal culture.11 Aboriginal people were also seen as being essentially lazy. In 1877, the superintendent of the Wawanosh Home near Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, a Miss Capelle, complained:

They are in general very lazy, even more so than the negroes, who have a great heat as their excuse; but the Indians living in the most healthy climate of the world, in a bracing air, have only neglected their mental as well as their bodily powers, and a good discipline is wanted to change them in a lapse of time to really useful working people.12

Margaret Butcher wrote of the First Nations people she encountered at Kitamaat, British Columbia, in 1917:

They are a slow, indolent, dirty people bound very strongly by custom and superstition. Matron says the young folk who have been educated in this school and at Coqualeetza will have more chance when some half dozen of the old folks of the Village, who still hold fast to their ancient customs are dead and one hopes that it is so. In all our bunch of 37 children there are only two who appear cunning and they are half-breeds.13

In another letter, she wrote, “These people have no history—or written language—no arts or handicrafts.”14

When teacher Maggie Nicoll was accused of mistreating children at the Presbyterian school in northwestern Ontario in 1902, she asked if Aboriginal people had any right to comment on staff behaviour.

Do you think an Indian—whose children simply run wild—one day having a feast, and at another time having perhaps only one article of food, and not enough of that—with clothing half in rags, and even in the middle of winter, sometimes having neither shoes nor moccasins—is capable of judging what is proper treatment for a child? And still further mention may be made of this fact, that until an Indian has that sort of respect, which savors somewhat of awe or fear perhaps, for the person who has to deal with him in school management nothing can be done.15

When faced with a former student’s complaints about his treatment at the Shubenacadie school in Nova Scotia, Principal J. P. Mackey depicted the student as shiftless: “To play a game of baseball was work for Tom; he would rather sit in the sun and pester a bumblebee or a fly, by pulling off one wing and one leg at a time. To make an Indian work is the unpardonable sin among them.” Mackey portrayed all Aboriginal people as natural liars. “For myself, I never hope to catch up with the Indian and his lies, and in fact I am not going to try.”16

Residential school staff members were representatives of colonial authority. Whether they were proclaiming the Anglican school at Aklavik to be the “most northerly residential school in the British Empire,” or using the cadet corps to instill in boys at the Roman Catholic school at Williams Lake, British Columbia, “some feeling of pride in belonging to the British Empire,” many of the staff were proud of the schools’ connection to the British Empire.17 It was not uncommon for missionaries to assume that by mitigating the harsher impacts of colonialism, they were, in effect, upholding the honour of the empire. Selina Bompas, the wife of Anglican Bishop William Bompas, spent much of her life in the Yukon. In a speech to the Dawson Anglican women’s auxiliary, she reminded members:

The poor Indians are nearly swamped by the white man. You have invaded their territory, cut down their forests, thereby driving away their moose and caribou, and depriving them of their very means of subsistence. Yet the evil is not unmixed with good. The banner of the Cross is now, thank God, unfurled among you, and now sick Indians are welcomed and lovingly tended in your hospitals. The children are taught freely in your school.18

In an effort to uphold the honour of the imperial project, missionaries and principals often acted as advocates on behalf of Aboriginal people. Hugh McKay, the superintendent of Presbyterian work among Aboriginal people, concluded that Aboriginal people were “a people that is becoming extinct, a poor people suffering for want of the necessaries of life and dying without any sure hope for the life to come.”19 McKay criticized the federal government for failing to implement its Treaty promises and for failing to alleviate the hunger crisis on the Prairies.20 Similarly, William Duncan, the Anglican missionary at Metlakatla, British Columbia, advised the Tsimshian on how to advance arguments in favour of Aboriginal title. The Oblates assisted First Nations in making claims to land by circulating petitions and attempting to enforce their rights. Nicolas Coccola, who was principal of the Cranbrook and Williams Lake schools, travelled to Ottawa to argue on behalf of First Nations fishers whose traditional fishing practices had been criminalized by federal laws.21

Not all missionaries or residential school officials felt the same strong degree of loyalty to the British Empire. Many of the early Oblates came from France and Belgium. The women who were recruited to the female orders often came from Québec or Ireland. Their world views were shaped by their deep commitment to Roman Catholicism and by their generally French or French-Canadian background. While they were an integral part of the colonial process and shared many of the racial attitudes of other settlers, they stood apart from—and, at times, were in opposition to—the British Protestant colonial movement.22

Many of the staff members were motivated by a spirit of adventure as well as a religious commitment. As a young seminary student in Corsica, a French island in the Mediterranean, Nicolas Coccola concluded that he wanted more than a life as a priest. In his memoir, he wrote, “The desire of foreign missions with the hope of martyrdom appeared to me as a higher calling.”23 It was his desire to work in China.24 When he was undergoing his training as an Oblate, the French government adopted laws that placed the Oblates’ lands and communities in that country in jeopardy. In keeping with his adventurous nature, Coccola said to his superiors, “Give us guns, and protection will be assured.” Instead of arming him, the Oblates sent him to Canada.25

Others were less bellicose, but still inspired by a sense of adventure. As a small boy in England in the middle of the nineteenth century, Gibbon Stocken read with enthusiasm the missionary literature sent to him by an aunt. When he turned seventeen, he volunteered his services to the Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS). He hoped to be sent to India. Instead, after a brief period of training at the CMS’S Islington training school, he was offered a position on the Blackfoot Reserve in what is now southern Alberta.26 It was only after coming to Canada that Stocken was ordained as an Anglican minister.27 In 1887, once he was settled, he married the daughter of an English clergyman and brought her over to Canada. She died two years later.28 To help him in his work on the Prairies, Stocken was joined by his two younger brothers.29

British-born nurse and midwife Margaret Butcher managed to get to India, where she worked for a British family. From there, she made her way to British Columbia, where she worked with a Methodist mission to Japanese immigrants.30 In 1916, she was on her way to a job at the Methodist residential school in Kitamaat, British Columbia. She wrote to friends, “Here is Maggie, on the Ocean at the North of Vancouver Island, 200 miles away from her nearest relatives or acquaintances, with about £5 in her pocket, going to unknown shores. Isn’t it lovely!”31

Elizabeth Scott, who worked for many years at the Onion Lake, Saskatchewan, school, was raised in rural Manitoba. After a brief time as a rural schoolteacher, she went on to study medicine. She interrupted her studies in 1889 to travel to India to work with the Presbyterian missions there. Illness forced her to return in two years’ time.32

A similar thirst for experience motivated the four young people who set off from Toronto to establish an Anglican residential school for Inuit children at Shingle Point on the Arctic Ocean in 1929. The party included Anglican minister Sherman Shepherd, his sister Priscilla, who had training as a nurse, and two young teachers, Bessie Quirt and Florence Hirst. Quirt had just finished a year of training as a deaconess and had several years of experience in teaching school, and Hirst, according to Quirt, “had come from England a year before seeking adventure in a new land.” In a memoir, Quirt recalled:

There were no conveniences of any kind—water had to be brought from a fresh water stream some distance away, fuel was driftwood, fresh food was fish, light was from kerosene and gasoline lamps. In one’s wildest imagination it was difficult to see how we could survive a winter let alone operate a school.33

Two stories, one from southern Alberta in 1899 and the other from the Yukon in 1929, provide insight into the range of people who worked in a residential school and into the often improvised nature of school hiring.

On August 16, 1899, Maud Waldbrooke arrived at the Red Deer industrial school to take her place as matron. Initially, she seemed in good spirits, but within a few days of her arrival, she had lapsed into a depression. She told co-workers “she was quite prepared to die, and that her life was a burden to her, and if anybody would give her 25¢ worth of anything, she would take it.” On the evening of August 27, she said she was ill and took a large drink of alcohol from the school’s medicine cupboard. She disappeared from the school that evening. When her absence was noted the following morning, the principal had the school building searched and then notified the police. It was not until two days later that the principal, under pressure from the staff, conducted a fruitless search of the brush around the school. In the opinion of a police officer who conducted a later investigation, the principal’s efforts were too little, too late.

Six days after the matron had gone missing, an unknown man approached the school. When the school farmer, Mr. Owens, asked the man for his name, he turned and ran. Owens, believing the man was connected to Waldbrooke’s disappearance, got a revolver from the school and fired a shot at the man, reportedly aiming over his head. According to Owens, the man turned, returned fire, and fled into the bush. Three months later, an unknown person broke into the principal’s home but, despite the opportunity, did not steal any valuables. Shortly thereafter, a man was seen lurking around the school stable one morning. Owens chased him off. However, as he escaped, the man fired three gunshots at the farmer. In mid-December, evidence was found that suggested someone had been peering in the dormitory and staff-room windows. The mysterious events culminated with the destruction by fire of the pig barn. A police investigation concluded, however, that the fire was not arson. A police investigator also doubted there was any connection among the various events that followed Waldbrooke’s disappearance.34

Waldbrooke’s family came to help look for her, but she was never found. The family members believed that the father of a student she had reprimanded had killed her, but police officials believed the disappearance was, in all likelihood, suicide.35 The mystery of what became of her was never resolved.

In 1929, the staff of the Dawson Hostel for Aboriginal students in the Yukon included a so-called mystery woman. According to director C. F. Johnson, she was “a Polish peasant woman who walked all the way from Telegraph Creek to Dawson arriving here just as winter was setting in.” The hostel took her in after she had lost several other jobs. Johnson said she was “uncouth, proud and ignorant and of uncertain temper and there is very little she can do. However she irons and sews after a fashion so that she earns her board. Every little bit that she does is a real help and relieves the others just that much.”36 However, by spring, “the girls got on her nerves and she ‘ran amuck’ amongst them,” so Johnson let her go.37

The missionary societies

In recruiting staff, there was a major distinction between the Roman Catholic and Protestant missionary organizations. The Roman Catholic schools during this period could draw staff from a number of Catholic religious orders, most of whose members had made explicit vows of obedience, poverty, and chastity. In the spirit of those vows, they would be obliged to go where they were sent, would not expect payment, and would have no families to support. The vast majority of Protestant principals were male clergy. They too often were assigned their posting by missionary societies. Unlike the Roman Catholic principals, however, the Protestant principals often were married men with families to support. Protestant school staff members were not violating sacred vows if they accumulated personal savings, refused postings, or resigned. The Catholics and Protestants also differed in that each Protestant church developed a single national entity to oversee its Aboriginal missionary work in Canada. Typically, this agency had responsibility for residential schools. Within the Roman Catholic Church, responsibility was more diffused. The order of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate was responsible for the majority of the residential schools, but the order was slow in developing a national body that would represent it in its dealings with Ottawa. Furthermore, the Oblates could not claim to speak or act for the Roman Catholic Church as a whole.

Although the Roman Catholics operated most of the residential schools, the church, often with good reason, viewed itself as an embattled minority in Canada. In 1871, Roman Catholics accounted for 40% of the Canadian population; Methodists, 16%; Presbyterians, 15%; Anglicans, 13%; and Baptists, 7%. In 1921, the share was virtually the same.38 In 1941, at the end of the period under review in this chapter, Roman Catholics accounted for 43% of the population; the United Church (formerly Methodist and some Presbyterians), 19%; Presbyterians, 7%; and Anglicans, 15%. Yet, while the Catholic Church may have been the largest Christian denomination in Canada, 60% of their adherents lived in one province: Québec.39 Table 31.1 shows the distribution of residential schools by religious denomination in the 1930–31 school year. That year, there were eighty schools, the highest number to operate at one time during this period (from 1867 to 1939).

Table 31.1. Residential schools by religious denomination, 1930–31.

| Church |

Number of schools |

% of total number of schools |

| Roman Catholic |

44 |

55 |

| Church of England |

21 |

26.25 |

| United Church |

13 |

16.25 |

| Presbyterian |

2 |

2.5 |

Source: Canada, Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs, 1931, 13.

From these figures and the chart above, it is clear that the number of schools allotted to each church was not a reflection of that denomination’s share of the general population. Rather, the number of schools was the product of each church’s history of missionary work. Roman Catholic and Anglican dominance was the outcome of the work that Roman Catholic Oblate missionaries and the Anglican Church Missionary Society missionaries carried out in the Canadian Northwest in the nineteenth century. Although staff life in Protestant and Catholic residential boarding schools had much in common, it should be recognized that there also were significant differences, arising from the central role that male and female religious orders played in the Roman Catholic schools. (That role is discussed in more detail below.)

The Anglican missionary societies

For most of the nineteenth century, Anglican missionary work in British North America was funded and directed by the British-based Church Missionary Society (CMS). (The history and work of this society are outlined earlier in this volume.) This began to change in the 1880s with the establishment of the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Province of Canada of the Church of England (DFMS). Because the more evangelical Anglicans viewed the DFMS as being too bureaucratic and ineffective, they established a second, competing, organization in 1894: the Canadian Church Missionary Association. The two organizations merged in 1902 to create the Missionary Society of the Church of England in Canada (MSCC).40 The new body’s founding principles held that “it is the first duty of the church to evangelize the world.”41 In 1903, the British CMS announced it was going to gradually withdraw from work among Canadian Aboriginal people. By 1920, all aid was to cease.42 The prospect of the loss of funding from Britain, coupled with reports on ill health at residential schools, led prominent Anglican evangelical Samuel Blake to mount his campaign to reduce Anglican involvement in residential schooling. That campaign failed. Instead, the Canadian MSCC took over responsibility for most of the Anglican residential schools in Canada, which quickly became the society’s largest expenditure. The exceptions in this period were the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario; the St. George’s school in Lytton, British Columbia (which had been founded by the British-based New England Company); and the Gordon’s Reserve school near Punnichy, Saskatchewan. The MSCC was not directly responsible for these three schools.43

In 1920, the MSCC formally assumed responsibility for “Indian and Eskimo work in the Dominion of Canada.”44 By the following year, it had established an Indian and Eskimo Commission to direct its Aboriginal residential schools.45 Sidney Gould became the general secretary of the MSCC in 1910. Born in England, he and his family immigrated to Canada in 1883 when he was fifteen. Gould attended Wycliffe College in Toronto, where he pledged, “It is my purpose, God permitting, to become a foreign missionary.” After receiving his medical degree, he carried out missionary work in Palestine before returning to Canada. As head of the MSCC, he played a central role in transferring responsibility for Anglican work with Aboriginal people from the British Church Missionary Society to the MSCC.46 He continued in his position with the MSCC until his death in 1938.47 From its creation in the 1920s until the mid-1940s, the Indian and Eskimo Commission’s field secretary was T. B. R. Westgate of Winnipeg.48 Westgate had joined the Church Missionary Society in German East Africa in 1902. He was imprisoned by the Germans during the First World War and returned to Canada after his release. He also conducted missionary work in Paraguay.49

The Methodist missionary societies

From the late 1870s onward, the Methodist missionary work in Canada was carried out by the Methodist Church’s Board of Missions under the direction of Alexander Sutherland. In 1906, the Board of Missions was split into two organizations: one with responsibility for missionary work in Canada; and one with responsibility for foreign work, which also had responsibility for work with Aboriginal people. Sutherland became the head of the Foreign Missions Board. He was succeeded in this by Egerton Shore and, later, James Endicott.50 James Woodsworth was the director of western missions for the Methodist Church from 1886 to 1915.51 One of his sons, J. F. Woodsworth, served as principal of both the Red Deer and Edmonton residential schools. (James Woodsworth was also the father of J. S. Woodsworth, the founder of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, a forerunner of today’s New Democratic Party.)52

At the time of the creation of the United Church of Canada in 1925, the Methodist Church of Canada operated three residential schools in British Columbia (Chilliwack, Kitamaat, and Port Simpson), two in Alberta (Edmonton and Morley, which was operated as a semi-residential school until 1926, when a new residential facility was built), two in Manitoba (Brandon and Norway House), and one in Ontario (Mount Elgin at Muncey). After amalgamation, the United Church assumed responsibility for all these schools.53

The Presbyterian missionary organization

While most of the Presbyterian Church’s missionary efforts were devoted to overseas missions, the Presbyterian Foreign Mission Committee (FMC) was responsible for all Presbyterian Church work with Aboriginal, Jewish, and Chinese peoples in Canada until 1912.54 The FMC’S full-time secretary, R. P. MacKay, played a central role in determining and implementing Presbyterian Church missionary policy from 1892 to 1925.55 The Home Mission Committee (Western Section) handled all other mission work in Canada west of the Maritimes. In 1912, the commission was renamed the Board of Home Missions (Western Section). This body took on responsibility for work with Aboriginal and Jewish peoples, while the Foreign Mission Committee retained responsibility for work with Chinese people in Canada. James Robertson, the superintendent of missions for the West, oversaw much of the Presbyterian missionary work in western Canada until his death in 1902.56 The Presbyterians were relatively late in establishing residential schools. They established two in British Columbia (at Ahousaht and Alberni), four in Saskatchewan (Kamsack, File Hills, Regina, and Round Lake), two in Manitoba (Birtle and Portage la Prairie), and one in northwestern Ontario (originally near Shoal Lake, later in Kenora). After the creation of the United Church in 1925, the Presbyterian Church in Canada retained responsibility for just two schools: Birtle and the school in northwestern Ontario. The rest of the schools that were still open were transferred to the United Church.57 (The Regina school had closed in 1910; the Kamsack school, in 1915.)58

The United Church missionary organization

After the church union in 1925, the United Church created its Board of Home Missions,59 with C. E. Manning and J. H. Edmison as the board’s joint secretaries.60 Along with responsibility for work with French Canadians and with immigrants, the Board of Home Missions had responsibility for residential schools.61 In 1927, the United Church operated thirteen schools with 1,227 students. The total cost of operating the schools was $215,727. Of this amount, $181,000 came from the federal government, and $34,727 came from the United Church, of which the United Church Women’s Missionary Society (WMS) raised $21,157.62 The fact that such a large portion of the church contribution came from the WMS underscores the significant role that women played in funding, organizing, and staffing residential schools.

There was a measure of co-operation among the Protestant missionary organizations. They had an informal agreement by which they would not compete for converts within the same geographic region.63 As a result, for example, there were no Presbyterian schools in Alberta, or any Methodist schools in Saskatchewan. The foreign mission boards of the Anglican, Congregational, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches co-operated in 1921 to establish a Canadian School of Missions in Toronto.64

The Protestant women’s organization

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, women began to have a more significant presence in public life in Europe, the United States, and Canada. This was linked to the growth of a feminist consciousness and the teaching of the Social Gospel, which argued that there were specific female values that women could contribute to campaigns for social reform. While many restrictions still applied to their participation in church life, women did come to play an important role in supporting, directing, and carrying out church missionary work.65

Austin McKitrick, the principal of the Presbyterian school at Shoal Lake in northwestern Ontario, acknowledged this when he wrote in 1901, “I think if we men were to put ourselves in the places of some overworked, tired-out women, we would perhaps not stand it so patiently as they often do.”66 Presbyterian school principal W. W. McLaren worried that female staff members often were worked to exhaustion. In 1912, he wrote of the need to require

a medical examination for the lady workers in particular and a means of superannuation of ladyworkers [sic] whose strength is no longer equal to the strain and who are yet dependent upon their salaries for maintenance. None but strong active sound [illegible, possibly “nerved”] women are suitable for this work. Many of the difficulties and misunderstandings that arise are due almost entirely to the neurotic condition of some of the workers.67

One missionary wrote that, knowing what he did about what was expected of female missionaries, he would discourage any daughter of his from working for the Methodist Women’s Missionary Society.68

Protestant women’s organizations raised funds and sponsored school operations. These organizations also recruited, trained, and supported female school workers.69 Many women who felt a call to do missionary work married missionaries, and found themselves taking on a central—and sometimes unpaid—position in running residential schools.70

One of the first organizations founded by Christian lay women to promote missionary work was the United Baptist Missionary Union, established in the Maritimes in the 1870s. It was followed in 1876 by the Women’s Baptist Foreign Missionary Society of Eastern Ontario and Québec.71 The Women’s Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada was established in 1876.72 The merger of the Methodist Episcopal Church and the Methodist Church in Canada in 1881 led to the creation of the Canadian Methodist Women’s Missionary Society (MWMS).73 The society operated until 1925, when the United Church was created. During its forty-four-year history, the MWMS employed more than 300 women at missions in Japan, China, and Canada. Many of them came from small towns in Ontario and the Maritimes. They were often daughters of ministers, merchants, and professionals. Many had training as teachers, nurses, or doctors; they were usually sent overseas. The less-qualified missionaries were placed in home missions, working with recent immigrants and Aboriginal peoples. Some women spent their working lives in the missionary field; two-thirds of them, however, left after two or three years.74

Initially, the society was intended to raise money to support specific elements of the Methodist Church’s general missionary society.75 The Methodist Women’s Missionary Society was particularly charged with funding Thomas Crosby’s work with Aboriginal people in Port Simpson, British Columbia. In its first year of operation, the society raised $200 to support Crosby’s work.76 The MWMS also supported the McDougall Orphanage for Aboriginal children in Morleyville in what is now Alberta, and helped fund work among Roman Catholics in Montréal, as well as a female missionary in Japan.77 The society contributed funds to support the establishment of the Coqualeetza Institute in Chilliwack, British Columbia, in 1885. It recruited four women who served as matrons at the school during its first fifteen years of operation. From 1889 on, the society also supported a girls’ home in Kitamaat, British Columbia.78 Over a four-decade history, the MWMS raised $6.5 million.79

In recruiting missionaries, the MWMS sought to set a high standard. A candidate for mission work was to “believe herself divinely called to the work” and to have experienced “salvation through the atonement of Jesus Christ our Lord.”80 Successful candidates were expected to make a five-year commitment and to remain single during that period. Those who did not live up to those commitments were expected to pay back all or a portion of the cost of transporting them to the mission and establishing them there.81

One of the first Methodist female missionaries sent to work with Aboriginal people was Kezia Hendrie, a dressmaker from Brantford. She was hired in 1882 to work as the matron of the Port Simpson girls’ school. Although she underwent what she described as a “spiritual salvation” at the school, she found the supervision of the girls to be difficult. After three years on the job, she resigned to marry another Methodist missionary, Edward Nicholas.82 Her replacement, Agnes Knight, was proud of the regimentation she imposed on the school, and recorded, “We have bed-room, dining-room, kitchen and washroom rules, also general rules, or a timetable giving the hour for everything, from the rising-bell to bed-time.”83

With the coming of the creation of the United Church, the MWMS ceased to exist. It was replaced by the United Church Women’s Missionary Society, with a million-dollar budget that supported 400 mission workers.84

In 1885, Anglican women organized a women’s auxiliary. One of the organization’s early tasks was to collect and send clothes to missions.85 In 1912, the Anglican Women’s Auxiliary (WA) and the Anglican Missionary Society of the Church in England reached an agreement: the WA was to do “all the work among women and children in the Foreign Fields of the Missionary Society of the Church of England in the Dominion of Canada.”86 While women were to remain on the fringes of Anglican Church government, the Women’s Auxiliary constituted a parallel operation. By 1923, it was raising 43% of the Canadian church’s missionary budget (for both Canadian and foreign missions).87 The Women’s Auxiliary was the source of many of the nurses in Anglican residential schools. In 1920, the auxiliary put out a call for women “preferably but not necessarily between 30 and 40 years of age possessing sound health, adaptability to unusual conditions, capacity for co-operating harmoniously with fellow workers and ability to live contentedly in a small community with little opportunity for social pleasures.”88

The Presbyterian Women’s Foreign Missionary Society (PWFMS) was formed in 1876. Among its early leading figures were Marjory McLaren, the wife of the convenor of the church’s Foreign Missionary Society, and Catherine Ewart, a sister-in-law of Ontario premier Oliver Mowat.89 Initially, it supported the work of women working in India, and it was not until 1885 that it began working in Canada.90 The move into Canadian work was, in part, a response to reports of the success of Roman Catholic missionaries working among Aboriginal people.91 All its work focused on the conversion of women and children.92 By 1902, the PWFMS was funding all the Presbyterian work among Aboriginal peoples in British Columbia, and providing half the budget for work in Manitoba and what is now Saskatchewan and Alberta.93 In explaining why a “foreign” mission society was doing so much work in Canada, pwmfs official Elizabeth Harvie wrote that work with Aboriginal people was “work among the heathen.”94 In 1914, the Presbyterians merged their women’s foreign missionary organization with the women’s domestic missionary organization to create the Women’s Missionary Society.95 A Presbyterian society in Scotland also sponsored the higher education of graduates of the Presbyterian residential schools.96

In some cases, local women’s committees led the way in establishing residential schools. Presbyterian women in Portage la Prairie were distressed by conditions in a nearby First Nations community in 1886. When local church leaders turned down their request for support, the women established their own missionary society and opened a day school for First Nations children, and provided the students with a daily lunch. The school was eventually turned over to the PWFMS, which converted it into a boarding school.97

Although the Protestant churches did not have female religious orders, they did have deaconesses. These were women who had undergone religious and practical training with the intent of a career of church service. The deaconess movement first emerged in Germany in the 1830s.98 Starting in the 1860s, institutions were established in England to provide training for female Protestant missionaries. Deaconess training included religious studies, cooking, nursing, and accounting. Although a deaconess had a title and specific training, the position of a deaconess was not formally defined until well into the twentieth century. Like the Roman Catholic nun, the deaconess was expected to provide assistance to the male missionary. But, while it was a subservient position, it did allow women an opportunity to step outside the domestic sphere to which society sought to limit them in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.99

Several training programs developed in Canada for deaconesses. The Anglicans opened a deaconess training school in Toronto in 1892. A Methodist facility was established in Toronto in 1894.100 The two-year training program was divided into nursing and non-nursing sections, and the school was an important training ground for female missionaries.101 The Presbyterian Women’s Foreign Missionary Society established the Ewart Training Home in Toronto in 1897. In 1908, the Presbyterians established a formal order of deaconesses, leading to the creation of the Presbyterian Deaconess and Missionary Training Home.102 Although the Ewart Training Home initially provided a six-month training course that included both religious and practical training, by 1908, the training period had been extended to two years.103 After church union, the United Church established its own United Church Training School.104 The Presbyterian Church continued to operate Ewart College.105

The Oblates of Mary Immaculate

The Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) was the dominant Roman Catholic organization involved in the operation of residential schools. The OMI was not the only male Roman Catholic order in charge of residential schools in Canada. For example, priests from the local Catholic diocese founded the school at Kuper Island, which was later taken over by the Montfort Fathers.106 Similarly, the Christie school on the west side of Vancouver Island was founded by a chapter of the Order of St. Benedict in 1899.107 The Jesuits operated the residential school at Wikwemikong, Ontario, that was later transferred to Spanish, Ontario.108 However, the vast majority of the Roman Catholic schools were operated by Oblates, in large measure as a result of the work they had undertaken among Aboriginal peoples in the Canadian Northwest in the nineteenth century.

The general administrative headquarters for the Oblates was in France until 1905, when it relocated to Rome. The Oblate order was divided into geographical jurisdictions called “provinces” and missionary vicariates.109 An “apostolic vicariate” was a territory under evangelization by missionaries. The expectation was that, over time, it would be transformed into a regular church diocese.110 In western Canada, the OMI was designated as a vicariate of missions until 1926. As such, it was under the direct authority of the order’s superior general in either France or Rome.111 Several Oblates became bishops, and successfully used their position to lobby the federal government for support for their residential school policy. However, the Oblates, who tended to view the federal government as a hostile, Protestant-dominated institution, were slow to develop a national body to co-ordinate activities with the federal government. Father Joseph Guy was appointed as an informal representative of the order in Ottawa in 1920.112 In 1924, the Oblate school principals began to hold regular meetings.113 An Oblate province of St. Peter’s was created in 1926. It extended from the Québec border west to the Pacific Ocean, with headquarters in Ottawa. In January 1936, the first meeting of the Commission Oblate des Ouevres Indiennes was held in Lebret, Saskatchewan.114 Oblate Omer Plourde became the new association’s representative in Ottawa in 1930 (even though he lived and worked in Winnipeg until 1942).115 While this served to co-ordinate Oblate activities, it did not co-ordinate all Roman Catholic activities: the Jesuits in charge of the school in Spanish were unaware of Plourde’s role until 1943. They also discovered that the federal government had thought, mistakenly, that the Oblates had been representing the Jesuits at annual meetings between government and church officials.116

The centrality of female labour in the Roman Catholic schools

The Roman Catholics relied heavily on female religious orders to staff and operate the residential schools, orders such as the Sisters of Charity (the Grey Nuns), the Sisters of Providence, the Sisters of Saint Ann, the Missionary Oblate Sisters, the Sisters of Assumption, the Benedictine Sisters, the Daughters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, and the Sisters of Notre Dame in Québec.117 These orders not only supplied much of the workforce for the schools, but they also provided it at an extraordinarily low cost. Access to such a low-cost labour supply was one of the main reasons why the Roman Catholic Church was able to operate so many schools.

To take just one example from the 1890s, although the Oblate order was formally charged with the operation of the school at St. Boniface, Manitoba, all staff in 1894 were members of the Sisters of Charity (Grey Nuns) except for the chaplain, carpenter, shoemaker, blacksmith, and farmer.118 An Indian Affairs survey from the 1920s indicates that at five Roman Catholic schools in the West, members of female religious orders accounted for 56% of the school staff.119

Reports from the 1930s make it clear that members of female orders made up a large portion of the workforce at Roman Catholic schools, and also that they were poorly paid in comparison with other school employees. According to an Indian Affairs audit, in 1934, the Delmas, Saskatchewan, school employed one principal, fourteen sisters, one teacher, and one farmer. The principal was paid $1,200 a year; the sisters, $200 a year each; the teacher, $90; and the farmer, $720.120 In the following year at the Fort Alexander, Manitoba, school, the male principal, assistant principal, and engineer were all in religious orders. The principal was paid $1,800, the assistant principal was paid $1,200, and the engineer was paid $900. The school also employed five laymen: a night watchman, two farmers, and two labourers. Each of these employees was paid $240 a year. The rest of the work was done by ten Oblate Sisters, who were paid $120 each per year.121 A similar situation prevailed at the school at Lestock, Saskatchewan. There, the principal, vice-principal, shoemaker, and gardener were all members of male religious orders. They were paid annual salaries of $900, $480, $240, and $240, respectively. The school farmer and engineer were both laymen and were paid $720 a year, and the assistant farmer was paid $360 a year. There were also eleven sisters, each of whom was paid $120 a year.122 In 1936, the Kamloops school had eighteen employees. The salaries for the principal, the assistant principal, the boys’ attendant, and the gardener, all members of male religious orders, were $2,100, $1,200, $900, and $900, respectively. The eight members of the Sisters of Saint Ann at the school were paid $300 a year each.123

The discussion of wages at Roman Catholic residential schools is complicated by the fact that, in most cases, these wages were not paid to the individual member of the religious order who worked for a specific school. Instead, they were paid to the order to which the priest, nun, or brother belonged. Indian Affairs was aware of this practice, but it was not understood by all federal government employees. In 1929, H. B. Rayner, a federal government auditor, noted that the Sandy Bay, Manitoba, school was making quarterly payments to the Winnipeg-based treasurer of the Oblate order. When asked about this by Rayner, the school principal said that the payments were “an assessment or tax made by the order.” The funds were to be applied to deficits for schools in the Oblates’ jurisdiction. Rayner estimated that the tax worked out to 14% of the school’s annual grant.124 The following year, Rayner noted that cheques equal to the salary amounts of the Oblates working at the school were being sent to the Oblates in Winnipeg, and the salaries for the sisters were sent to the Sisters of Notre Dame in Québec.125 Indian Affairs officials told the auditor that the department was aware of the policy of some religious orders of paying a portion of the staff’s salary to their order. The superintendent of Indian Education, Russell T. Ferrier, said that paying the salaries directly to the workers would be a mistake, since “deficits would then occur more frequently than in the past.”126

Similarly, the Jesuit school at Spanish sent money from the government’s per capita grant to the Jesuit Province as compensation for each priest and brother at the school. The principal, Paul Méry, wrote in 1935 to Jesuit Provincial Henry Keane that “every year a large amount, sometimes very large, was sent to the province” (in this case, province refers to the Jesuit Province, not the Ontario government). The principal congratulated himself on the fact that, unlike many Catholic-run schools, the Spanish school was not “bleeding the children to feed the mother house,” but he said that, given the recent cuts in the per capita grant, it would no longer be possible to pay the requested levy.127 Méry’s charge that other schools—which were almost all Oblate-run—were “bleeding the children to feed the mother house” is very serious. He did not, however, provide any supporting evidence for the allegation. Although some Catholics may have used money from the per capita grant to fund other missionary activities, it is also the case that they provided staff at well below market rates.

Some observers, such as Indian Commissioner David Laird, believed the Oblate policies allowed the order to provide students with more supervision than was available at the Protestant schools. In 1907, he wrote that, since members of Roman Catholic religious orders received very little in exchange for their services, the Catholic schools could

afford to have a much larger staff than where ordinary salaries are paid, and there is consequently less work for each to do, without interfering with the quality of the work done. In the case of these schools the teachers have generally no technical qualifications, but this is compensated for by their having a long experience subsequent to the usual convent or college training.128

The history of the Sisters of Charity and the role it played in Catholic evangelization in the Northwest in the nineteenth century has already been outlined. Two other female orders also played a significant role in the residential schools: the Sisters of Saint Ann and the Oblate Sisters of Mary Immaculate.

The Sisters of Saint Ann

In the 1840s, a Montréal woman, Esther Blondin, drew together a group of women to teach in a rural parish west of Montréal. By 1850, she had gained the approval of Québec Bishop Ignace Bourget to establish a religious community, the Sisters of Saint Anne. Blondin became Mother Marie-Anne, the order’s first leader. The order opened its first boarding school for rural youth in 1853 in Vaudreuil, Québec. Most of the sisters were from rural francophone backgrounds, although there were also some Irish-Canadian sisters. Those who joined the order had to undergo a two-year training period. They were given new names, and undertook vows of poverty, chastity, obedience, and instruction. Eight years after its founding, the order sent nuns to assist Catholic missionaries working in British Columbia. There, the order was known as the “Sisters of Saint Ann” (spelling Ann without an ‘e’).129 Eventually, the Sisters of Saint Ann worked at the Mission, Williams Lake, Kamloops, and Kuper Island residential schools in British Columbia.130

The Oblate Sisters of Mary Immaculate

The Oblates of the Sacred Heart and Mary Immaculate (more commonly known as the “Oblate Sisters”) was founded in 1904 as a teaching order. It was created in the West at the instigation of St. Boniface Bishop Louis-Philippe Langevin, as a response to the Laurier-Greenway compromise of 1896. Under that agreement, between Manitoba Premier William Greenway and federal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, the Manitoba government loosened its ban on teaching in French. Bishop Langevin established the Oblate Sisters to provide a supply of French-speaking Catholic teachers.131

Although the Missionary Oblate Sisters were based in western Canada, more than half of the sisters recruited between 1904 and 1915 came from Québec. The world these young women entered was governed by rules and the need for obedience. New members had to give up their names, their clothing, and their personal belongings (as one sister recalled, even a little thimble given to her as a present had to be sacrificed). They were discouraged from developing close friendships (which could be divisive within a small organization) or discussing religious issues with other sisters (since they were supposed to take their religious direction from priests). Visits from family members were not encouraged, and the directoress read all incoming and outgoing letters. Meal servings were small, and asking for more food was frowned upon, but, at the same time, one was expected to eat everything put on one’s plate. Any fresh fruit, always a rare commodity, received as a gift was to be shared with other members of the community.132 After they completed their training, they took vows of chastity, obedience, and poverty.133 The sisters had little privacy. Most sisters slept in dormitories that were kept locked during the day.134

The Oblate Sisters’ 1931 constitution made it clear that their role was to assist the Oblate Fathers. Great emphasis was laid on the vow of chastity, which required constant vigilance, since the human body was said to have “instincts of wild beasts.” Because of this, any form of entertainment was to be viewed with suspicion.135 Some of the Oblate Sisters came to the order as qualified teachers, but many had completed only a few years of high school. Given the demand for teachers and the order’s lack of funds, sisters often had to postpone their own education and, instead, teach for considerable lengths of time before they finally received their normal school certificates.136

The Oblate Sisters worked in four Manitoba residential schools (Cross Lake, Norway House, Fort Alexander, and Pine Creek), one in Ontario (McIntosh), and one in Saskatchewan (Kamsack). The Oblates dictated the terms of their service. At Cross Lake, for example, four sisters were expected to teach, take care of the church and sacristy, keep house, and cook and care for the students.137

It was through these organizations that the Canadian churches—both Protestant and Roman Catholic—recruited and mobilized a workforce that was dispatched to residential schools across northern Canada. It is common to speak of the schools as being “remote,” although many were located close to Aboriginal communities. They were, however, generally very far from the home communities of the staff. In fact, many of the memoirs and collections of letters of former staff members devote considerable detail to the lengthy journey undertaken to reach the school.138 Once there, staff members were submerged in a world for which most of them were not prepared.139

The work and the workers

Residential schools were intended to be economically self-sufficient. Many resembled miniature societies, employing workers in a wide range of capacities. There was generally more work than there were workers, meaning workloads were heavy. Because the pay was often low and the working and living conditions were difficult, turnover was high. Poor housing and stressful working conditions could combine to undermine a staff member’s health. Those who stayed on the job often hung on until they were well into their old age, since, due to low pay, their savings were also low and pensions were minimal. Although schools had difficulty attracting qualified teachers, many skilled individuals did seek employment in the schools. As with many aspects of residential school life, there is still a great deal to be learned about the people who worked there and how they lived.

In 1887, the staff at the Shingwauk Home at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, included an assistant superintendent, a schoolmaster, a matron, a servant, a carpenter, a farmer, and a boot maker. The affiliated Wawanosh Home for girls had a superintendent, a gardener, a matron, and a laundress.140 Tables 31.2 and 31.3 list the staff at the Qu’Appelle school, in what is now Saskatchewan, in 1893 and 1918. In 1893, the school had twenty full-time staff (Dr. Seymour was not a school employee). Nine staff members were women of the Sisters of Charity (the Grey Nuns). By 1918, there were twenty-three staff members, twelve of whom were Sisters of Charity.

Table 31.2. Staff, Qu’Appelle Industrial School, 1893.

| Name |

Duties |

| Rev. Father Hugonnard |

Principal |

| Rev. Father Dorais |

Assistant Principal |

| Mr. E. D. Sworder |

Clerk |

| Mr. H. F. Denehy |

1st Teacher |

| Mr. J. A. Joyce |

2nd Teacher |

| T. Redmond |

Farming Instructor |

| R. Meehan |

Carpenter |

| D. McDonald |

Blacksmith |

| C. Miles |

Night Watchman, Stone Mason and Gardener |

| A. Goyer |

Shoemaker Instructor |

| E. G. F. Werer |

Baker |

| Rev. Sister Goulet |

Matron |

| Rev. Sister Bergeron |

Cook |

| Rev. Sister St. Alfred |

1st Teacher |

| Rev. Sister Vincent |

2nd Teacher |

| Rev. Sister Elizabeth |

Assistant Cook and Laundress |

| Rev. Sister St. Thomas |

Seamstress |

| Rev. Sister Lamothe |

In charge of boys’ infirmary, boys’ clothing and laundry. |

| Rev. Sister St. Adèle |

In charge of girls’ infirmary, dormitory, clothing and laundry. |

| Rev. Sister St. Armand |

Supervises the housemaids, their work in the dining-rooms, and the ironing of all linen. |

| Doctor Seymour |

Medical Superintendent |

Source: Canada, Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs, 1893, 172.

Table 31.3. Staff, Qu’Appelle Industrial School, 1918.

| Name |

Duties |

Hours Required |

| Rev. A. J. A. Dugas |

Principal |

Not limited |

| Rev. Kalmes |

In charge of boys |

Not limited |

| Rev. M. Mercure |

Farm instructor |

Not limited |

| Rev. E. Gauthier |

Engineer & Plumber |

Not limited |

| Geo. J. Harrison |

Accountant & Band Instructor |

Office 9 A.M. to 4 P.M. |

| H. Town |

Senior Teacher |

9 A.M. to 4 P.M. |

| A. McLennan |

Junior Teacher |

9 A.M. to 4 P.M. |

| J. Z. Lafleur |

Baker & Butcher |

Until work complete |

| M. Salamon |

Shoemaker |

7 A.M. to 6 P.M. |

| James Condon |

Assistant Shoemaker |

7 A.M. to 6 P.M. |

| Baptiste Blondeau |

Assistant Farmer |

7 A.M. to 6 P.M. |

| Reverend Sister Baulne |

Matron |

Not limited |

| Reverend Sister Cloutier |

Senior Teacher |

9 A.M. to 4 P.M. |

| Reverend Sister St. Alfred |

2nd Division |

9 A.M. to 4 P.M. |

| Reverend Sister Gregoire |

3rd Division |

9 A.M. to 4 P.M. |

| Reverend Sister Dauost |

Infirmarian |

Not limited |

| Reverend Sister Lamontagne |

In charge of senior girls |

Not limited |

| Reverend Sister Delormier |

In charge of junior girls |

Not limited |

| Reverend Sister Sauve |

In charge of junior girls |

Not limited |

| Reverend Sister Holy Name |

In charge of kitchen |

Not limited |

| Reverend Sister Ledwin |

In charge of dining room |

Not limited |

| Reverend Sister St. Amour |

Charge of boy’s sewing room |

Not limited |

| Reverend Sister Champagne |

Assistant boy’s sewing room |

Not limited |

Source: TRC, NRA, Library and Archives Canada, RG10, volume 6327, file 660-1, part 1, “Industrial School Qu’Appelle, List of Staff and Duties Assigned.” 1918. [PLD-007504-0001]

In addition to teachers and administrators, the Qu’Appelle school had farmers, carpenters, blacksmiths, shoemakers, bakers, matrons, laundresses, cooks, seamstresses, engineers, and band instructors. Table 31.3, which gives the names and duties of the staff members, also outlines their required hours of work. Teachers appear to have had the shortest working day, from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., but they would also be obliged to spend additional time making preparations for the next day. The tradesmen were expected to work eleven hours a day, and the butcher, who doubled as the baker, was to work “until work complete.” Work-shift limits applied only to those who were not members of religious orders. For those who were, with the exception of the members who taught, there was no limit to the length of the working day.

Heavy workloads were common in Protestant schools, as well. In 1889, John Ashby, the assistant principal at the Battleford school, wrote to complain about his wife’s situation. He gave the following description of her summer routine at the school:

To be in charge of girls every alternate week from 6:00 to 6:45 when they are transferred to the officer in charge of the dining room.

To be in charge of the girls doing housework such as from 8:30 to 9:45 a.m. and to inspect the work done by the girls between 7:30 and 8:30 under the charge of a monitor for the above supervision to be responsible.

From 9:45 to 12:15 to prepare girls for school and take classes and transfer them in proper order to the officer in charge of the dining room.

From 12:15 to 1:45 off duty.

From 1:45 to 2:00, preparation for school, and 2:00 to 4:00 to take classes.

From 4:00 to 5:00 p.m. in charge of girls recreation.

From 5:00 to 5:15 to prepare girls for tea and hand them over to the dining room officer.

From 5:15 to 5:45 to supervise girls laying table in Principal’s dining room.

From 5:45 to 6:30 off duty.

From 6:30 p.m. to 7:00. In charge of recreation.

From 7:00 to 8:00. To take class during study excepting on Fridays. Each alternate Friday to take charge of girls whilst bathing. [illegible] this duty does not fall to the teacher, she is to be off duty. Alternate weeks to take girls after prayers until after retiring.141

Four years after Ashby registered this complaint, the Indian Affairs annual report printed the following summaries of the workloads of two teachers at the Middlechurch school.

Mr. Williams, first teacher, besides teaching in the regular school hours, has these duties: Every morning he rises with the boys [at 6 a.m.] and goes to their dormitories; he sees that they wash and dress themselves properly, calls the roll, (reads prayers when the principal is not present). After school he has a general oversight of the boys, conducts evening prayers [at 8:15]. Saturday night he has a collect class [a “collect” is a form of prayer]; he has a half holiday every Wednesday and Saturday. On Thursday he attends the boys’ bathing; in summer time he teaches the boys cricket and other out-of-door sports.142

Miss Willith, teacher of the junior classes, rises with the children, attends the dressing of the girls, calls the roll, attends with them at prayers and marches them into breakfast. Her school closes at 3 p.m., then she has the girls for sewing, darning, mending, knitting, etc., until 4 o’clock; she then takes them for a walk till five, marches them into tea 5.45, after tea has a ‘King’s Daughters’ Class’ twice a week, takes them into prayers and attends the junior girls in their preparation and getting into bed. She takes alternate Sundays with Mrs. Burman [in] charge of the girls for the whole day. On Saturday she has general charge of all the girls and bathing of the junior girls.143

Winnipeg physician George Orton noted the impact that caring for a school of sick children could have on staff. In 1895, many students at the Middlechurch school suffered from pneumonia, bronchitis, and typhoid fever. By then, John Ashby was principal of the Middlechurch school, and his wife was the matron. In Orton’s opinion, the Ashbys were overworked: “Mrs. Ashby, as well as Mr. Ashby, was indefatigable in her efforts, as also the staff, in attention to nursing and caring for the sick. Poor Mrs. Ashby was terribly run down in health, as a consequence, and should even yet be given a short leave of absence to recruit her health before the winter.”144

The seven-day week was the norm for many employees. The policy at the Anglican schools into the 1920s was to allow “one full day off duty each month.”145

Indian Affairs did not produce detailed job descriptions for the various job positions at the schools. However, over time, the churches developed their own list of expectations and responsibilities.

In the Anglican schools, the school matron was “responsible for the management of all the domestic affairs of the Institution.” In this position, she was expected to:

•Take charge of all the food supplies.

•See that the school menu was adhered to.

•Take charge of the children’s clothing, and all linens at the school.

•Record the date of receipt of all clothing and food supplies as well as the date of their distribution.

•Provide the principal with copies of the records and a list of items that needed to be ordered.

•Supervise all the female staff and female students, seeing that “the work assigned to each is performed in accordance with instructions given.”

•“Report to the principal any inefficiency on the part of any member of the staff, or any disobedience or misconduct on the part of any of the pupils.”

•Assist the principal in selecting students to be given special instruction in different school departments.

•Arrange for the care of sick children in the absence of a nurse.

•Take on the duties of sick or absent staff or arrange to have other staff take on these duties.146

The Anglican farm instructor had responsibility for “all the outside work of the Institution, including the buildings, land, fences, live stock, machinery implements, vehicles, etc.” With the assistance of the students, he was expected to:

•Operate the farm “upon a paying basis.”

•Maintain a full list of needed supplies.

•Raise “a plentiful supply of vegetables” for the staff, students, and livestock.

•Sell surplus produce on the open market.

•Transport all needed provisions to the school.

•Secure a sufficient supply of hay, preferably from the school land.

•Maintain the grounds.

•Instruct students in the best methods of horticulture, agriculture, and the care of livestock.

•Maintain the water, heating, and lighting systems.

•Provide the principal with regular reports, including reports on sickness and misconduct.147

The cooks at the Anglican schools were expected to:

•Prepare all meals for the pupils and the staff.

•Give instructions in cooking, making bread, making butter, etc.

•Ensure the cleanliness of the kitchen, pantry, dining room, and cupboards.

•Bake all bread required.

•Be responsible for all milk brought in from the farm.

•“Exercise careful and judicious economy in the use of food.”

•Oversee students assigned to the kitchen.

•Insist that students under her charge speak English.

•Report any disobedience to the principal.

•Engage in the moral and spiritual education of the students.148

The list of teacher responsibilities the Anglican Church developed during the 1920s set out the following:

•Be punctual in attendance.

•Keep “an accurate record of the names of the pupils and the time spent by each under instruction.”

•Follow the Indian Affairs course of instruction along with “any additional subjects which may be suggested by the [Anglican] Indian and Eskimo Commission.”

•Pay “strict attention to the instruction of the pupils, in Biblical knowledge, Church History and Doctrine, devoting not less than fifteen minutes to this purpose daily, and using such Text-books as may be sanctioned by the Indian and Eskimo Commission.”

•Report cases of “gross misconduct” to the principal.

•Supervise the children’s play.

•Supervise the sweeping, ventilating, and cleaning of the classroom.

•Inform the principal of any equipment that had been destroyed or was lacking.

In keeping with the school’s religious mission, the overall direction was to ensure that the children

should be made to feel that the Schools do not exist so much for the purpose of teaching them how to make the most money, or how to get the most pleasure out of life, as to how they may be able to render the greatest assistance as spiritual and educational forces in the uplifting of their own race.149

As previously noted, one of the main reasons for the federal government’s decision to enter into partnership with church organizations to run the residential schools was the expectation that the churches would provide a low-cost labour force. Indian Commissioner Hayter Reed embraced the idea, writing in 1895 that

as the work is of a denominational, and therefore necessarily of a missionary or philanthropic character, and the churches have facilities for obtaining through various societies men and women to whom remuneration for such work is a minor consideration, it seems only reasonable that a lower, rather than a higher rate, as compared with other service, should obtain.150

In fact, as early as 1889, the federal government had ordered the church-managed industrial schools to cut staff wages. Qu’Appelle principal Joseph Hugonnard described those salary reductions as arbitrary and “odious.” He said that many of the staff had been at the school for several years and had legitimately expected a salary increase.151 When his salary was cut in 1889, Battleford school assistant principal John B. Ashby wrote to Hayter Reed to express his “disappointment that my services have been so little appreciated by the department.” After two years of “faithful and hard service,” he thought, his value to the department should be increased, not decreased.152

Alexander Sutherland of the Methodist Church was particularly outspoken about the link between low wages and the difficulties the schools had in recruiting staff. In 1887, he wrote to the minister of Indian Affairs about the “difficulty of obtaining efficient and properly qualified teachers, on account of the meagre salaries paid.”153 Six years later, he described the salaries as “insulting.” Those who accepted them would be deemed as “inferior or incompetent men.”154

In a strange boast made in 1894, Mount Elgin principal W. W. Shepherd argued that the fact that three former pupils, all of whom had teachers’ certificates, were working as farm labourers was a demonstration of the school’s success “in making the farm boys competent workmen.” In reality, the young men were all working as farm labourers because that work paid better than teaching in Indian schools.155

In 1903, Red Deer principal C. E. Somerset noted:

One of the great difficulties in connection with schools of this class is to obtain the services of persons whose interest is greater than the wage they receive; this difficulty increases as the years go. The nature of the duties is very trying and the better class of assistants cannot be obtained. This institute has suffered in the past very greatly because trained assistants were not to be obtained.156

Pay was not only low, but, in some cases, it was also uncertain. In his 1904 report, Metlakatla principal John Scott noted that Miss Davies, who was in charge of the girls’ division, had “given her services for more than two years without any salary or other reward.”157 In 1921, the staff at the Lytton school had not been paid for six months.158

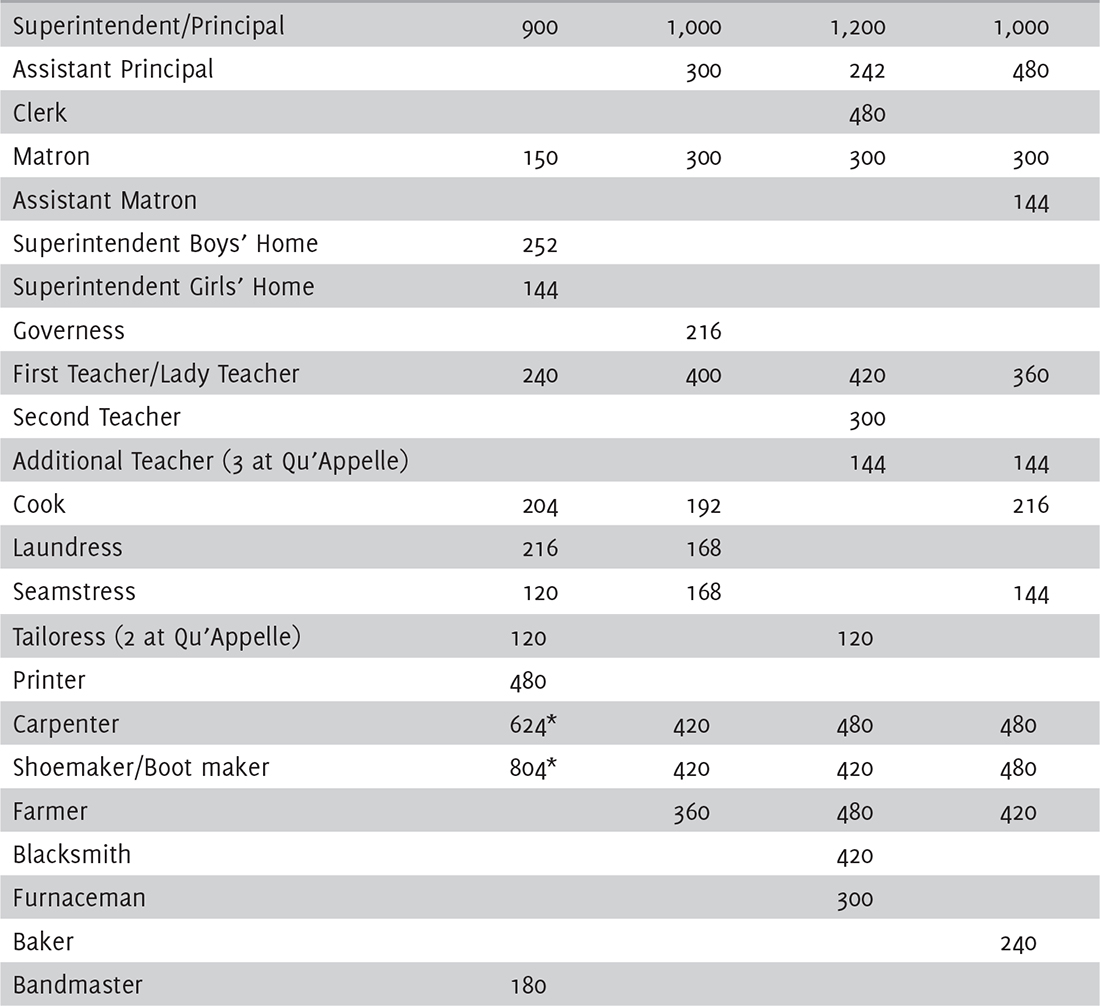

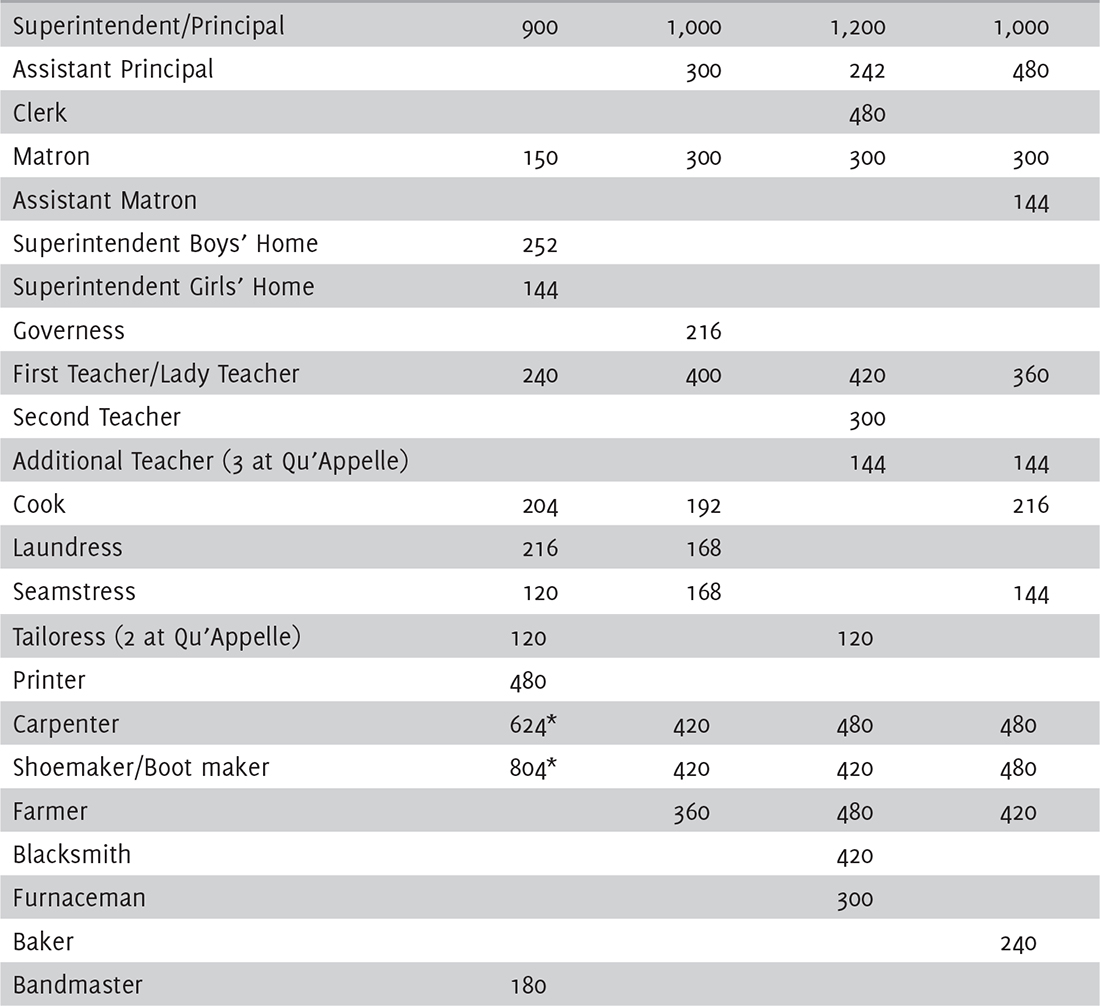

There was a considerable difference in salaries from one industrial school to the next. Table 31.4 sets out the staff positions and monthly salaries at four prairie industrial schools in 1894. The federal government imposed the salaries at these schools. The Elkhorn school was operated by the Anglican Church, the Regina school was operated by the Presbyterian Church, and the Qu’Appelle and High River schools were operated by the Roman Catholic Church.159

Table 31.4. Annual salaries for the Elkhorn, Regina, Qu’Appelle, and High River industrial schools, 1894.

Source: Library and Archives Canada, RG10, volume 3938, file 121/607, “List of Officers at following Industrial Schools showing salaries as proposed to be reduced by the Department.” [PLD-008587] (In the original table, the wages were presented as monthly figures.)

* No food rations were provided to the boot maker or the carpenter at the Elkhorn school.

The table shows considerable variation in the wages for certain jobs. For example, the matrons at the Regina, Qu’Appelle, and High River schools were all paid twice as much as the Elkhorn matron. Teachers’ wages could range from $144 to $420. Skilled trades workers generally were paid more than teachers. At only one school was the farmer paid less than the teacher, and the carpenters, printers, shoemakers, and blacksmiths always were paid at least as much as the teachers and, in most cases, considerably more than the teachers were paid. Cooks, seamstresses, tailoresses, and laundresses—positions held by women—were paid less than teachers. In general, the matron, who was charged with managing the domestic operations of the schools, was paid less than teachers, as were the staff members who supervised children when they were not in class.160 These general patterns were in keeping with those in the larger, general Canadian economy.161

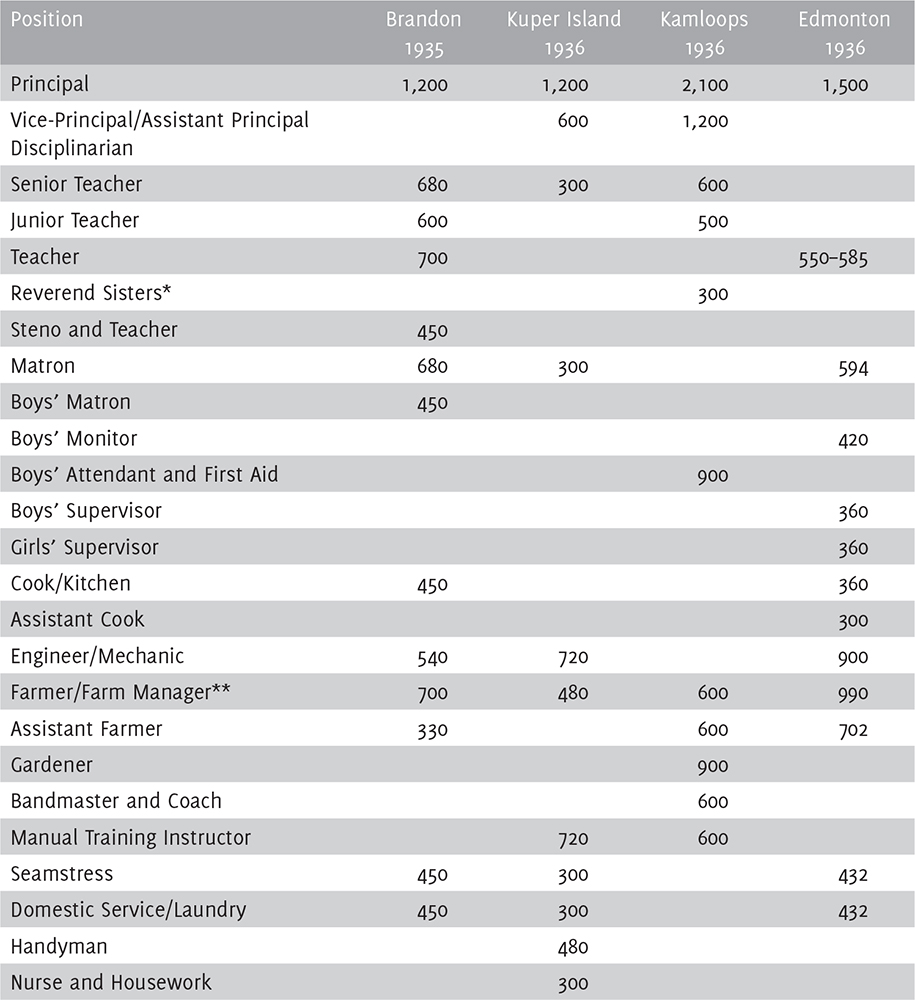

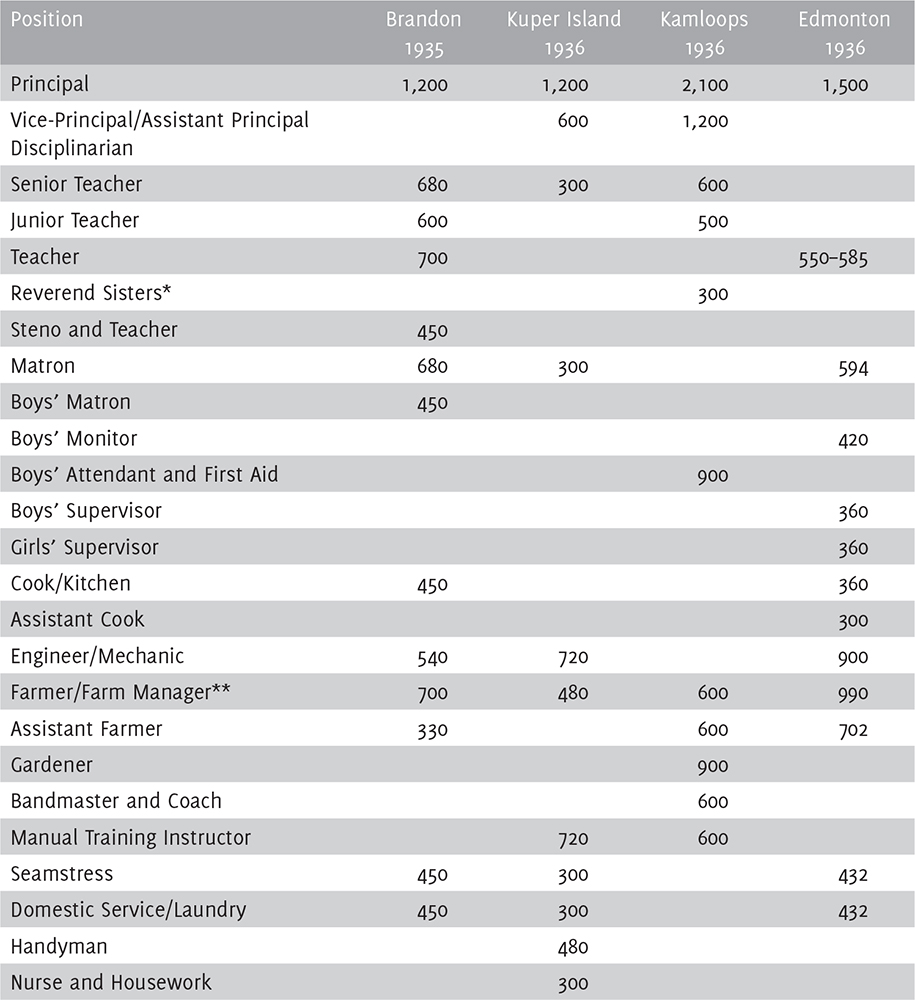

Table 31.5 shows staff salaries at the Brandon school in 1935, and at the Kuper Island, Kamloops, and Edmonton schools in 1936. The Kuper Island and Kamloops schools were operated by the Roman Catholic Church; the Brandon and Edmonton schools were operated by the United Church. (It is not possible to prepare a direct comparison with the figures in Table 31.5 because, by 1936, the Regina and High River schools were closed. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has been unable to locate audited statements for the Elkhorn and Qu’Appelle schools from this period.)

Table 31.5. Staff salaries at schools at Brandon, Manitoba (1935); and at Kuper Island, British Columbia; Kamloops, British Columbia; and Edmonton, Alberta (1936).

Source: TRC, NRA, Library and Archives Canada, RG10, volume 8845, file 961/16-2, part 1, Kuper Island Residential School, Roman Catholic, Kuper Island, Cost of Operations August 1, 1935 to July 31, 1936; [KUP-003365-0004] RG10, volume 8845, file 963/16-2, part 1, July 3, 1936, Re: Kamloops Residential School, Roman Catholic; [KAM-002000] RG10, volume 8840, file 511/16-2-015, Statement No. 2, Re: Brandon Residential School, Cost of Operations and Salaries, 1936; [BRS-001427-0003] RG10, volume 8843, file 709/16-2-001, part 1, Re: Edmonton Residential School, (United) Alberta (cover page torn) 20 March 1936. [EDM-000358]

*The Kamloops school had eight Sisters of Saint Ann on staff for a total cost of $2,400 a year.

** At Kamloops, the position is called “Farm Ass’t. & Boiler Eng’r.”

In comparing wages paid in the mid-1930s with those paid in the mid-1890s, it is apparent that the salaries paid to principals remained relatively static during this period. The one exception is the Kamloops principal, who was paid nearly double the wage of other principals. This may be explained by the fact that Kamloops was the largest school in the system. By the 1930s, teachers’ wages ranged between $300 and $700, with a higher rate prevailing at the Protestant schools. The only trades instructor left was the farmer: by the 1930s, none of these schools employed people to teach printing, carpentry, or boot- and shoemaking. Where, in the 1890s, the wage paid to the farm instructor ranged between $360 and $480, in the 1930s, it ranged from $480 to $990, again with the higher rates prevailing in the Protestant schools (although the lone gardener employed by the Catholic school in Kamloops was paid $900). At three schools, the farmer was paid more than the highest-paid teacher, while at Kamloops, the farmer received the same wage as the highest-paid teacher. At each school, the matron’s wage was equivalent to a teacher’s wage. The cooks and the staff charged with caring for the students were still at the bottom of the pay structure.162

Pay rates during this period varied considerably. In 1932, the boarding school at Morley, Alberta, employed eight people: a principal, a matron, two teachers, a seam-stress, a laundress, a cook, and a farmer. The principal’s annual pay was $1,500; the matron’s was $550; the two teachers were paid a combined total of $1,250; the seam-stress and laundress were each paid $500; the cook was paid $540; and the farmer was paid $480.163 A 1935 report from the small Crosby Girls’ Home in Port Simpson, British Columbia, showed a staff of only three. The principal was paid $850 a year, while the two teachers were each paid $743.75.164 In 1935, the Squamish school in British Columbia had eight employees: a principal, a vice-principal, a senior teacher, a junior teacher, a beginners’ teacher, a matron, a cook, and a gardener. Each of them was paid $360 a year, except for the gardener, whose annual salary was $340.165 Again, the wage rates at the two United Church schools (Morley and Port Simpson) were generally higher than those at the Roman Catholic school at Squamish.

Table 31.6 presents comparative information on salaries in public and religious schools in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia, the five provinces that operated residential schools extensively throughout this period. These figures, provided by Statistics Canada, are averages, except for Manitoba. The Manitoba figures are the median, which means that 50% of the salaries were below that level. The Northwest Territories and Yukon did not have a public school system during this period, so salary comparisons with religious schools there cannot be made.

Table 31.6. Average annual salaries of schoolteachers, by provinces, 1926, 1930, 1935. (Figures for Manitoba represent the median; all others represent the average.)

| |

1926 |

1930 |

1935 |

| Ontario |

|

|

|

| Public (elementary) schools |

1,248 |

1,270 |

1,128 |

| Separate (elementary) schools |

763 |

771 |

810 |

| Manitoba |

|

|

|