The document in Example

2-1 is composed of a single element

named person. The

element is delimited by the start-tag

<person> and the

end-tag </person>. Everything between the

start-tag and the end-tag of the element (exclusive) is called the

element's content . The content of this element is the text:

Alan Turing

The whitespace is part of the content, although many

applications will choose to ignore it. <person> and </person> are

markup . The string "Alan Turing" and its surrounding

whitespace are character data . The tag is the most common form of markup in an XML

document, but there are other kinds we'll discuss later.

Superficially, XML tags look like HTML tags. Start-tags begin with

< and end-tags begin with

</. Both of these are followed

by the name of the element and are closed by >. However, unlike HTML tags, you are

allowed to make up new XML tags as you go along. To describe a

person, use <person> and

</person> tags. To describe

a calendar, use <calendar>

and </calendar> tags. The

names of the tags generally reflect the type of content inside the

element, not how that content will be formatted.

There's also a special syntax for empty elements,

elements that have no content. Such an element can be represented

by a single empty-element tag that begins

with < but ends with

/>. For instance, in

XHTML, an XMLized reformulation of standard HTML,

the line-break and horizontal-rule elements are written as

<br /> and <hr /> instead of <br> and <hr>. These are exactly equivalent

to <br></br> and

<hr></hr>, however.

Which form you use for empty elements is completely up to you.

However, what you cannot do in XML and XHTML (unlike HTML) is use

only the start-tag—for instance <br> or <hr>—without using the matching

end-tag. That would be a well-formedness error.

Let's look at a slightly more complicated XML

document. Example 2-2 is a

person element that contains more

information suitably marked up to show its meaning.

Example 2-2. A more complex XML document describing a person

<person>

<name>

<first_name>Alan</first_name>

<last_name>Turing</last_name>

</name>

<profession>computer scientist</profession>

<profession>mathematician</profession>

<profession>cryptographer</profession>

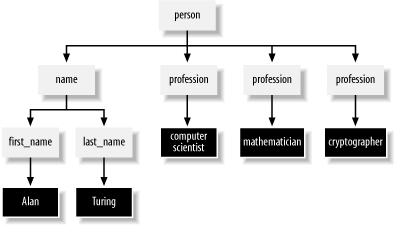

</person>The XML document in Example 2-2 is still composed

of one person element. However,

now this element doesn't merely contain undifferentiated character

data. It contains four child elements: a

name element and three profession elements. The name element contains two child elements

of its own, first_name and

last_name.

The person element

is called the parent of the name element and the three profession elements. The name element is the parent of the

first_name and last_name elements. The name element and the three profession elements are sometimes called

each other's siblings . The first_name

and last_name elements are also

siblings.

As in human society, any one parent may have multiple

children. However, unlike human society, XML gives each child

exactly one parent, not two or more. Each element (with one

exception we'll note shortly) has exactly one parent element. That

is, it is completely enclosed by another element. If an element's

start-tag is inside some element, then its end-tag must also be

inside that element. Overlapping tags, as in <strong><em>this common example from HTML</strong></em>, are

prohibited in XML. Since the em

element begins inside the strong element, it must also finish

inside the strong

element.

Every XML document has one element that does not have a

parent. This is the first element in the document and the element

that contains all other elements. In Examples Example 2-1 and Example 2-2, the person element filled this role. It is

called the root element of the

document . It is also sometimes called the document

element. Every well-formed XML document has exactly one

root element. Since elements may not overlap, and since all

elements except the root have exactly one parent, XML documents

form a data structure programmers call a

tree. Figure 2-1 diagrams this

relationship for Example

2-2. Each gray box represents an element. Each black box

represents character data. Each arrow represents a containment

relationship.

In Example 2-2, the

contents of the first_name, last_name, and profession elements were character data;

that is, text that does not contain any tags. The contents of the

person and name elements were child elements and some

whitespace that most applications will ignore. This dichotomy

between elements that contain only character data and elements that

contain only child elements (and possibly a little whitespace) is

common in record-like documents. However, XML can also be used for

more free-form, narrative documents, such as business reports,

magazine articles, student essays, short stories, web pages, and so

forth, as shown by Example

2-3.

Example 2-3. A narrative-organized XML document

<biography> <paragraph> <name><first_name>Alan</first_name> <last_name>Turing</last_name> </name> was one of the first people to truly deserve the name <emphasize>computer scientist</emphasize>. Although his contributions to the field are too numerous to list, his best-known are the eponymous <emphasize>Turing Test</emphasize> and <emphasize>Turing Machine</emphasize>. </paragraph> <definition>The <term>Turing Test</term> is to this day the standard test for determining whether a computer is truly intelligent. This test has yet to be passed. </definition> <definition>A <term>Turing Machine</term> is an abstract finite state automaton with infinite memory that can be proven equivalent to any any other finite state automaton with arbitrarily large memory. Thus what is true for one Turing machine is true for all Turing machines no matter how implemented. </definition> <paragraph> <name><last_name>Turing</last_name></name> was also an accomplished <profession>mathematician</profession> and <profession>cryptographer</profession>. His assistance was crucial in helping the Allies decode the German Enigma cipher. He committed suicide on <date><month>June</month> <day>7</day>, <year>1954</year></date> after being convicted of homosexuality and forced to take female hormone injections. </paragraph> </biography>

The root element of this document is biography. The biography contains paragraph and definition child elements. It also

contains some whitespace. The paragraph and definition elements contain still other

elements, including term,

emphasize, name, and profession. They also contain some

unmarked-up character data. Elements like paragraph and definition that contain child elements and

non-whitespace character data are said to have mixed

content. Mixed content is common in XML documents

containing articles, essays, stories, books, novels, reports, web

pages, and anything else that's organized as a written narrative.

Mixed content is less common and harder to work with in

computer-generated and processed XML documents used for purposes

such as database exchange, object serialization, persistent file

formats, and so on. One of the strengths of XML is the ease with

which it can be adapted to the very different requirements of

human-authored and computer-generated documents.