CHAPTER 14

Installing and Upgrading Windows

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Identify and implement preinstallation tasks

• Install and upgrade Windows XP, Windows Vista, and Windows 7

• Troubleshoot installation problems

• Identify and implement post-installation tasks

An operating system (OS) provides the fundamental link between the user and the hardware that makes up the PC. Without an operating system, all of the greatest, slickest PC hardware in the world is but so much copper, silicon, and gold wrapped up as a big, beige paperweight (or, if you’re a teenage boy, a big, gleaming, black paperweight with a window and glowing fluorescent lights, possibly shaped like a robot). The operating system creates the interface between human and machine, enabling you to unleash the astonishing power locked up in the sophisticated electronics of the PC to create amazing pictures, games, documents, business tools, medical miracles, and much more.

This chapter takes you through the processes for installing and upgrading Windows. It starts by analyzing the preinstallation tasks, steps not to be skipped by the wise tech. The bulk of the chapter comes in the second section, where you’ll learn about installing and upgrading Windows XP, Windows Vista, and Windows 7. Not all installations go smoothly, so section three looks at troubleshooting installation issues. The final section walks you through the typical post-installation tasks.

802

Preparing for Installation or Upgrade

Installing or upgrading an OS is like any good story: it has a beginning, a middle, and an end. In this case, the beginning is the several tasks you need to do before you actually do the installation or upgrade. If you do your homework here, the installation process is a breeze, and the post-installation tasks are minimal.

Don’t get discouraged at all of the preparation tasks. They usually go pretty fast, and skipping them can cause you gobs of grief later when you’re in the middle of installing and things blow up. Well, maybe there isn’t a real explosion, but the computer might lock up and refuse to boot into anything usable. With that in mind, look at the nine tasks you need to complete before you insert that CD or DVD. Here’s the list; a discussion of each follows:

1. Identify hardware requirements.

2. Verify hardware and software compatibility.

3. Decide what type of installation to perform.

4. Determine how to back up and restore existing data, if necessary.

5. Select an installation method.

6. Determine how to partition the hard drive and what file system to use.

7. Determine your computer’s network role.

8. Decide on your computer’s language and locale settings.

9. Plan for post-installation tasks.

NOTE This nine-step process was once part of the CompTIA A+ exam objectives. Starting with the 220-801 and 220-802 exams, CompTIA has dropped this process from the exams, but I’ve come to like it. The nine steps are practical, clear, and easy to remember. I use these as a mental checklist every time I install Windows.

NOTE This nine-step process was once part of the CompTIA A+ exam objectives. Starting with the 220-801 and 220-802 exams, CompTIA has dropped this process from the exams, but I’ve come to like it. The nine steps are practical, clear, and easy to remember. I use these as a mental checklist every time I install Windows.

Identify Hardware Requirements

Hardware requirements help you decide whether a computer system is a reasonable host for a particular operating system. Requirements include the CPU model, the amount of RAM, the amount of free hard disk space, the video adapter, the display, and the storage devices that may be required to install and run the operating system. They are stated as minimums or, more recently, as recommended minimums. Although you could install an operating system on a computer with the old minimums that Microsoft published, they were not realistic if you wanted to actually accomplish work. With the last few versions of Windows, Microsoft has published recommended minimums that are much more realistic. You will find the published minimums on the packaging and at Microsoft’s Web site (www.microsoft.com). Later in this chapter, I’ll also tell you what I recommend as minimums for Windows XP, Windows Vista, and Windows 7.

Verify Hardware and Software Compatibility

Assuming your system meets the requirements, you next need to find out how well Windows supports the hardware and software you intend to use under Windows. You have three sources for this information. First, the Setup Wizard that runs during the installation does a quick check of your hardware. Microsoft also provides a free utility, usually called Upgrade Advisor, which you can run on a system to see if your hardware and software will work with a newer version of Windows. Second, Microsoft provides Web sites where you can search by model number of hardware or by a software version to see if it plays well with Windows. Third, the manufacturer of the device or software will usually provide some form of information either on the product box or on their Web site to tell you about Windows compatibility. Let’s look at all three information sources.

Setup Wizard/Upgrade Advisor

When you install Windows, the Setup Wizard automatically checks your hardware and software and reports any potential conflicts. It’s not perfect, and if you have a critical issue (like a bad driver for your video card), Setup Wizard may simply fail. With any flavor of Windows, first do your homework. To help, Windows also provides a utility called Upgrade Advisor (see Figure 14-1) on the installation media (also downloadable) that you run before you attempt to install the software.

Figure 14-1 Upgrade Advisor

Web Sites and Lists

To ensure that your PC works well with Windows, Microsoft has put a lot of hardware and software through a series of certification programs to create a list of devices that work with Windows. The challenge is that Microsoft seems to change the name of the list with every version of Windows.

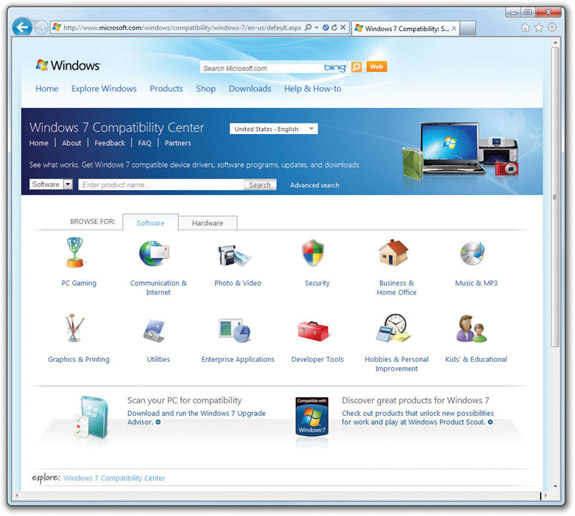

NOTE You’ll occasionally hear the HCL or Windows Logo’d Product List referred to as the Windows Catalog. The Windows Catalog was a list of supported hardware Microsoft would add to the Windows XP installation media. The Windows 7 Compatibility Center Web site is the modern tech’s best source, so use that rather than any printed resources.

NOTE You’ll occasionally hear the HCL or Windows Logo’d Product List referred to as the Windows Catalog. The Windows Catalog was a list of supported hardware Microsoft would add to the Windows XP installation media. The Windows 7 Compatibility Center Web site is the modern tech’s best source, so use that rather than any printed resources.

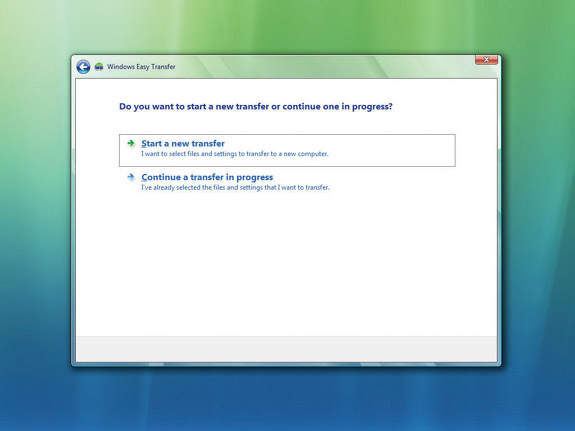

It all began back with Windows 95 when Microsoft produced a list of known hardware that would work with their OS, called the Hardware Compatibility List (HCL). Every version of Windows up to Windows Vista contained an HCL. This list was originally simply a text file found on the install disc or downloadable from Microsoft’s Web site. Over time, Microsoft created specialized Web sites where you could look up a piece of hardware or software to determine whether or not it worked with Windows. These Web sites have gone through a number of names. Microsoft’s current Web site acknowledging what hardware and software works with Windows is the Windows 7 Compatibility Center, formerly known as the Windows Logo’d Products List (for Windows Vista) and the Windows Catalog (for Windows XP). Now the magic words are Windows 7 Compatibility Center, as shown in Figure 14-2. Here you can find information on compatible components for Windows 7.

Figure 14-2 Windows Compatibility Center

NOTE If you go looking for the Windows Catalog or Windows Logo’d Products List, you won’t find them. You’ll be redirected to the Windows 7 Compatibility Center (or a Web page explaining why you should upgrade to Windows 7).

NOTE If you go looking for the Windows Catalog or Windows Logo’d Products List, you won’t find them. You’ll be redirected to the Windows 7 Compatibility Center (or a Web page explaining why you should upgrade to Windows 7).

When you install a device that hasn’t been tested by Microsoft, a rather scary screen appears (see Figure 14-3). This doesn’t mean the component won’t work, only that it hasn’t been tested. Not all component makers go through the rather painful process of getting the Microsoft approval that allows them to list their component in the Windows 7 Compatibility Center. As a general rule, unless the device is more than five years old, go ahead and install it. If it still doesn’t work, you can simply uninstall it later.

Figure 14-3 Untested device in Windows XP

EXAM TIP The CompTIA A+ 802 exam expects you to know the different compatibility tools available for each OS covered. Windows XP offered the Upgrade Advisor and the Hardware Compatibility List (HCL). Windows Vista added the online Windows Logo’d Product List. Every online tool (with the exception of ftp.microsoft.com where you can find old HCLs in text format) now just points to the Windows 7 Compatibility Center.

EXAM TIP The CompTIA A+ 802 exam expects you to know the different compatibility tools available for each OS covered. Windows XP offered the Upgrade Advisor and the Hardware Compatibility List (HCL). Windows Vista added the online Windows Logo’d Product List. Every online tool (with the exception of ftp.microsoft.com where you can find old HCLs in text format) now just points to the Windows 7 Compatibility Center.

Manufacturer Resources

Don’t panic if you don’t see your device on the official Microsoft list; many supported devices aren’t on it. Check the optical disc that came with your hardware for proper drivers. Better yet, check the manufacturer’s Web site for the most up-to-date drivers. Even when the Windows 7 Compatibility Center lists a piece of hardware, I still make a point of checking the manufacturer’s Web site for newer drivers.

When preparing to upgrade, check with the Web sites of the manufacturers of the applications already installed on the previous OS. If there are software compatibility problems with the versions you have, the manufacturer should provide upgrades or patches to fix the problem.

Decide What Type of Installation to Perform

You can install Windows in several ways. A clean installation of an OS involves installing it onto an empty hard drive or completely replacing an existing installation. An upgrade installation means installing an OS on top of an earlier installed version, thus inheriting all previous hardware and software settings. You can combine versions of Windows by creating a multiboot installation. Installing usually involves some sort of optical disc, but other methods also exist. Let’s look at all the options.

Clean Installation

A clean installation means your installation ignores a previous installation of Windows, wiping out the old version as the new version of Windows installs. A clean installation is also performed on a new system with a completely blank hard drive. The advantage of doing a clean installation is that you don’t carry problems from the old OS over to the new one. The disadvantage is that you need to reinstall all your applications and reconfigure the desktop and each application to the user’s preferences. You typically perform a clean installation by setting your CMOS to boot from the optical drive before your hard drive. You then boot off of a Windows installation disc, and Windows gives you the opportunity to partition and format the hard drive and then install Windows.

Upgrade Installation

In an upgrade installation, the new OS installs into the same folders as the old OS, or in tech speak, the new installs on top of the old. The new OS replaces the old OS, but retains your data and applications and also inherits all of the personal settings (such as font styles, desktop themes, and so on). The best part is that you don’t have to reinstall your favorite programs. Many tech writers refer to this upgrade process as an in-place upgrade. Upgrades aren’t always perfect, but the advantages make them worthwhile if your upgrade path allows it.

EXAM TIP Microsoft uses the term in-place upgrade to define an upgrade installation, so expect to see it on the 802 exam. On the other hand, Microsoft documentation also uses the term for a completely different process, called a repair installation, so read whatever question you get on the exam carefully for context. For repair installations, see Chapter 19.

EXAM TIP Microsoft uses the term in-place upgrade to define an upgrade installation, so expect to see it on the 802 exam. On the other hand, Microsoft documentation also uses the term for a completely different process, called a repair installation, so read whatever question you get on the exam carefully for context. For repair installations, see Chapter 19.

To begin the upgrade of Windows, you should run the appropriate program from the optical disc. This usually means inserting a Windows installation disc into your system while your old OS is running, which autostarts the installation program. The installation program will ask you whether you want to perform an upgrade or a new installation; if you select new installation, the program will remove the existing OS before installing the new one.

NOTE Before starting an OS upgrade, make sure you have shut down all other open applications!

NOTE Before starting an OS upgrade, make sure you have shut down all other open applications!

If you are performing an upgrade to Windows XP and for some reason the installation program doesn’t start automatically, go to My Computer, open the installation disc, and locate winnt32.exe. This program starts an upgrade to Windows XP. For a Windows Vista or Windows 7 upgrade, open the disc in Windows Explorer and run Setup.exe in the disc’s root directory, which starts the upgrade for those versions of Windows.

Multiboot Installation

A third option that you need to be aware of is the dual-boot or multiboot installation. This means your system has more than one Windows installation and you may choose which installation to use when you boot your computer. Every time your computer boots, you’ll get a menu asking you which version of Windows you wish to boot. Multiboot requires that you format your active partition with a file system that every operating system you install can use. This hasn’t been much of a problem since the Windows 9x family stopped being relevant, because there’s really no reason to use anything other than NTFS.

Windows XP can be installed in a separate folder from an existing older copy of Windows, enabling you to put two operating systems on the same partition. Neither Windows Vista nor Windows 7 allows you define the install folder, so multibooting using Windows Vista or 7 requires you to put each installation on a different partition.

You’ll recall from Chapter 12 that Windows Vista and Windows 7 enable you to shrink the C: partition, so if you want to dual boot but have only a single drive, you can make it happen even if Vista/7 is already installed and the C: partition takes up the full drive. Use Disk Management to shrink the volume and create another partition in the newly unallocated space. Then install another copy of Windows to the new partition.

NOTE When configuring a computer for multibooting, there are two basic rules: first, you must format the system partition in a file system that is common to all installed operating systems, and second, you must install the operating systems in order from oldest to newest.

NOTE When configuring a computer for multibooting, there are two basic rules: first, you must format the system partition in a file system that is common to all installed operating systems, and second, you must install the operating systems in order from oldest to newest.

The whole concept behind multiboot is to enable you to run multiple operating systems on a single computer. This is handy if you have an application that runs only on Windows XP, but you also want to run Windows Vista or Windows 7.

Other Installation Methods

In medium to large organizations, more advanced installation methods are often employed, especially when many computers need to be configured identically. A common method is to place the source files in a shared directory on a network server. Then, whenever a tech needs to install a new OS, he can boot up the computer, connect to the source location on the network, and start the installation from there. This is called generically a remote network installation. This method alone has many variations and can be automated with special scripts that automatically select the options and components needed. The scripts can even install extra applications at the end of the OS installation, all without user intervention once the installation has been started. This type of installation is called an unattended installation.

Another type of installation that is very popular for re-creating standard configurations is an image deployment. An image is a complete copy of a hard disk volume on which an operating system and, usually, all required application software programs have been preinstalled. Images can be stored on optical discs, in which case the tech runs special software on the computer that copies the image onto the local hard drive. Images can also be stored on special network servers, in which case the tech connects to the image server using special software that copies the image from the server to the local hard drive. A leader in this technology has been Norton Ghost, which is available from Symantec. Other similar programs are Clonezilla and Acronis’s True Image.

Beginning with Windows 2000 Server, Microsoft added Remote Installation Services (RIS), which can be used to initiate either a scripted installation or an installation of an image. With Windows Server 2008 and 2008 R2, Microsoft implemented Windows Deployment Services (WDS) to replace RIS. Though they are two different systems, they work very similarly from a tech’s viewpoint. These tools help with big rollouts of new systems and operating system upgrades.

TIP Scripting OS and application installations is a full-time job in many organizations. Many scripting tools and methods are available from both Microsoft and third-party sources.

TIP Scripting OS and application installations is a full-time job in many organizations. Many scripting tools and methods are available from both Microsoft and third-party sources.

Determine How to Back Up and Restore Existing Data, If Necessary

Whether you run a clean install or perform an upgrade, you may need to back up existing user data first, because things can go very wrong either way, and the data on the hard drive might be damaged. You’ll need to find out where the user is currently saving data files. If they are saving onto the local hard drive, it must be backed up before the installation or replacement takes place. However, if all data has been saved to a network location, you are in luck, because the data is safe from damage during installation.

If the user saves data locally, and the computer is connected to a network, save the data, at least temporarily, to a network location until after the upgrade or installation has taken place. If the computer is not connected to a network, you have a few options for backup. For one, you can put the data on USB thumb drives. A slower option would be to copy the data to DVDs. You can also use an external hard drive, which is a handy thing for any tech to have. Wherever you save the data, you will need to copy or restore the data back to the local hard disk after the installation.

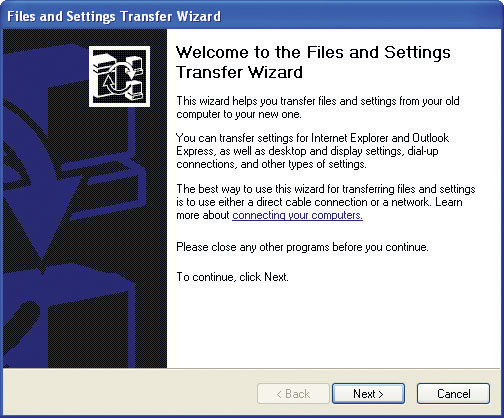

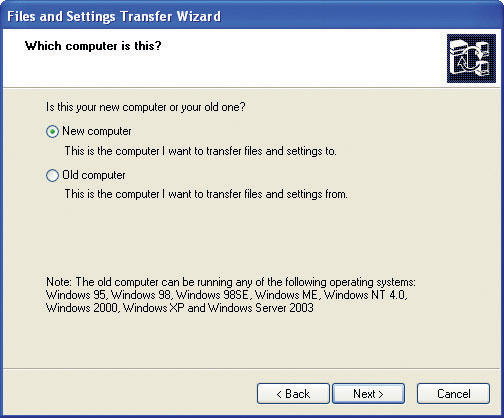

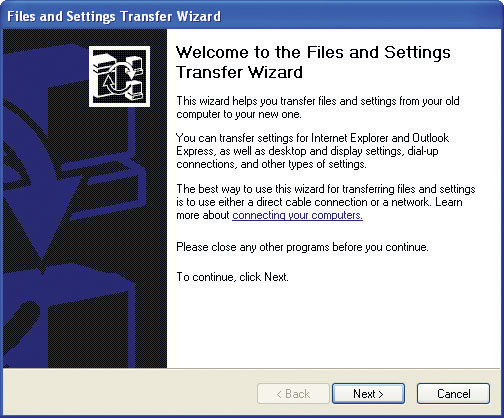

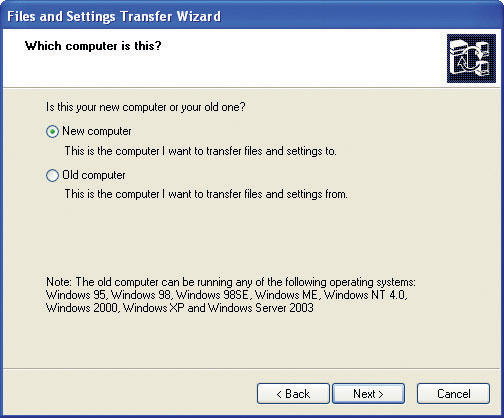

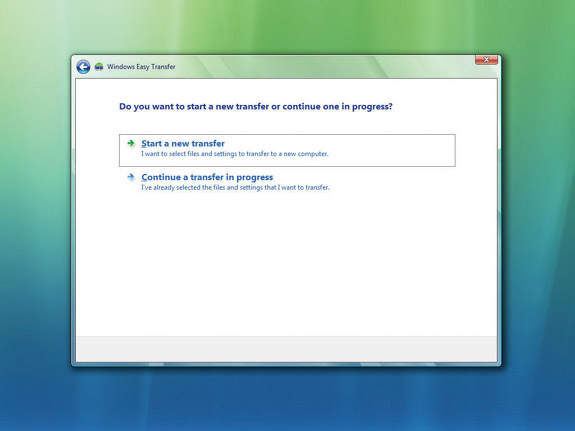

If you plan to migrate a user from one system to another, you might start the process by running the Files and Settings Transfer Wizard (Windows XP) or Windows Easy Transfer (Windows Vista and 7). You’ll complete that process after the Windows installation finishes. Rather than discuss the process twice, I’ll leave the full discussion on migration for the “Post-Installation Tasks” section later in this chapter.

Select an Installation Method

Once you’ve backed up everything important, you need to select an installation method. You have two basic choices: insert the installation disc into the drive and go, or install over a network.

Determine How to Partition the Hard Drive and What File System to Use

If you are performing a clean installation, you need to decide ahead of time how to partition the disk space on your hard disk drive, including the number and size of partitions and the file system (or systems) you will use. Actually, in the decision process, the file system comes first, and then the space issue follows, as you will see.

This was a much bigger issue back in the days when older operating systems couldn’t use newer file systems, but now that every Windows OS that you could reasonably want to install supports NTFS, there’s really no reason to use anything else. You still might have a reason to partition your drive, but as for choosing a file system, your work is done for you.

Determine Your Computer’s Network Role

The question of your computer’s network role comes up in one form or another during a Windows installation. A Windows computer can have one of several roles relative to a network (in Microsoft terms). One role, called standalone, is actually a non-network role, and it simply means that the computer does not participate on a network. You can install any version of Windows on a standalone computer. A standalone computer belongs to a workgroup by default, even though that workgroup contains only one member.

In a network environment, a computer must be a member of either a workgroup or a domain (if you’re using Windows 7 in a workgroup on a home network, it can also belong to a homegroup).

Decide on Your Computer’s Language and Locale Settings

These settings are especially important for Windows operating systems because they determine how date and time information is displayed and which math separators and currency symbols are used for various locations.

Plan for Post-Installation Tasks

After installing Windows, you may need to install the latest service pack or updates. You may also need to install updated drivers and reconfigure any settings, such as network settings, that were found not to work. You will also need to install and configure any applications (word processor, spreadsheet, database, e-mail, games, etc.) required by the user of the computer. Finally, don’t forget to restore any data backed up before the installation or upgrade.

The Installation and Upgrade Process

At the most basic level, installing any operating system follows a fairly standard set of steps. You turn on the computer, insert an operating system disc into the optical drive, and follow the installation wizard until you have everything completed. Along the way, you’ll accept the End User License Agreement (EULA) and enter the product key that says you’re not a pirate; the product key is invariably located on the installation disc’s case. At the same time, there are nuances between installing Windows XP or upgrading to Windows 7 that every CompTIA A+ certified tech must know, so this section goes through many installation processes in some detail.

EXAM TIP Although the typical installation of Windows involves a CD-ROM (for Windows XP) or DVD (for Windows Vista/7), there are other options. Microsoft provides a tool called Windows 7 USB DVD Download Tool for writing an ISO image to a USB thumb drive, for example, so you can download an operating system and install on a system that doesn’t have an optical drive. This is a cool option with Windows 7 and might be a very popular option with Windows 8.

EXAM TIP Although the typical installation of Windows involves a CD-ROM (for Windows XP) or DVD (for Windows Vista/7), there are other options. Microsoft provides a tool called Windows 7 USB DVD Download Tool for writing an ISO image to a USB thumb drive, for example, so you can download an operating system and install on a system that doesn’t have an optical drive. This is a cool option with Windows 7 and might be a very popular option with Windows 8.

Installing or Upgrading to Windows XP Professional

Windows XP has been around for a long time with a well-established upgrade and installation process. This is the one part of the CompTIA A+ exams where older versions of Windows may be mentioned, so be warned!

Upgrade Paths

You can upgrade to Windows XP Professional from all of the following versions of Windows:

• Windows 98 (all versions)

• Windows Me

• Windows NT 4.0 Workstation (Service Pack 5 and later)

• Windows 2000 Professional

• Windows XP Home Edition

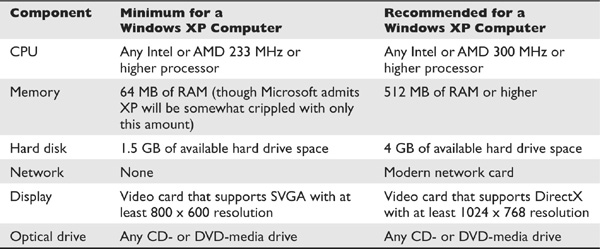

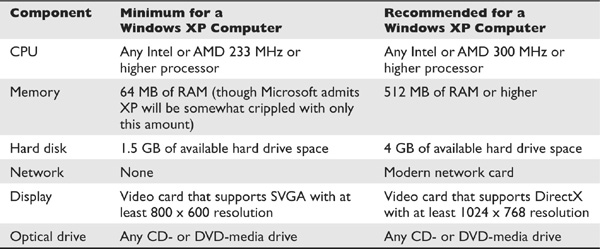

Hardware Requirements for Windows XP

Hardware requirements for Windows XP Professional are higher than for previous versions of Windows, but are still very low by modern hardware standards.

Windows XP runs on a wide range of computers, but you need to be sure that your computer meets the minimum hardware requirements, as shown in Table 14-1. Also shown is my recommended minimum for a system running a typical selection of business productivity software.

Table 14-1 Windows XP Hardware Requirements

Hardware and Software Compatibility

You’ll need to check hardware and software compatibility before installing Windows XP Professional—as either an upgrade or a new installation. Of course, if your computer already has Windows XP on it, you’re spared this task, but, you’re spared this task, but you’ll still need to verify that the applications you plan to add to the computer will be compatible. Luckily, Microsoft includes the Upgrade Advisor on the Windows XP disc.

Upgrade Advisor You would be hard-pressed these days to find a computer incapable of running Windows XP, but if you are ever uncertain about whether a computer you excavated at an archeological dig can run XP, fear not! The Upgrade Advisor is the first process that runs on the XP installation disc. It examines your hardware and installed software (in the case of an upgrade) and provides a list of devices and software that are known to have issues with XP. Be sure to follow the suggestions on this list.

You can also run the Upgrade Advisor separately from the Windows XP installation. You can run it from the Windows XP disc. Microsoft used to offer the XP Upgrade Advisor on its Web site, but searching for it now will just redirect you to the Windows 7 Upgrade Advisor, so running it from the disc is the way to go nowadays.

Booting into Windows XP Setup

The Windows XP discs are bootable, and Microsoft no longer includes a program to create a set of setup boot disks. This should not be an issue, because PCs manufactured in the past several years can boot from the optical drive. This system BIOS setting, usually described as boot order, is controlled through a PC’s BIOS-based Setup program.

In the unlikely event that your lab computer can’t be made to boot from its optical drive, you can create a set of six (yes, six!) Windows XP setup boot floppy disks by using a special program you can download from Microsoft’s Web site. Note that Microsoft provides separate boot disk programs for XP Home and XP Professional.

Registration Versus Activation

During setup, you will be prompted to register your product and activate it. Many people confuse activation with registration, but these are separate operations. Registration tells Microsoft who the official owner or user of the product is, providing contact information such as name, address, company, phone number, and e-mail address. Registration is still entirely optional. Activation is a way to combat software piracy, meaning that Microsoft wishes to ensure that each license for Windows XP is used solely on a single computer. It’s more formally called Microsoft Product Activation (MPA).

Mandatory Activation Within 30 Days of Installation Activation is mandatory, but you can skip this step during installation. You have 30 days in which to activate the product, during which time it works normally. If you don’t activate it within that time frame, it will be disabled. Don’t worry about forgetting, though, because once it’s installed, Windows XP frequently reminds you to activate it with a balloon message over the tray area of the taskbar. The messages even tell you how many days you have left.

Activation Mechanics Here’s how product activation works. When you choose to activate, either during setup or later when XP reminds you to do it, an installation ID code is created from the product ID code that you entered during installation and a 50-digit value that identifies your key hardware components. You must send this code to Microsoft, either automatically if you have an Internet connection or verbally via a phone call to Microsoft. Microsoft then returns a 42-digit product activation code. If you are activating online, you don’t have to enter the activation code; it happens automatically. If you are activating over the phone, you must read the installation ID to a representative and enter the resulting 42-digit activation code into the Activate Windows by Phone dialog box.

No personal information about you is sent as part of the activation process. Figure 14-4 shows the dialog box that opens when you start activation by clicking on the reminder message balloon.

Figure 14-4 Activation takes just seconds with an Internet connection.

Installing or Upgrading to Windows Vista

Preparing for a Windows Vista installation is not really different from preparing for a Windows XP installation. There are, of course, a few things to consider before installing or upgrading your system to Vista.

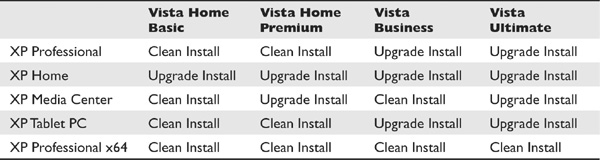

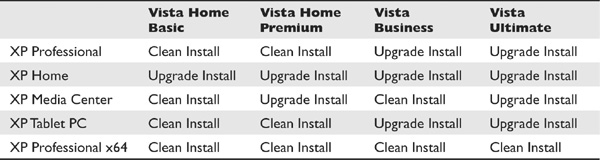

Upgrade Paths

Windows Vista is persnickety about doing upgrade installations with different editions; although you can upgrade to any edition of Vista from any edition of Windows XP, many upgrade paths will require you to do a clean installation of Vista. Vista’s upgrade paths are so complicated that the only way to explain them is to use a grid showing the OS you’re trying to upgrade from and the edition of Vista you’re upgrading to. Fortunately for you, Microsoft provides such a grid, which I’ve re-created in Table 14-2.

Table 14-2 Vista’s Labyrinthine Upgrade Paths

EXAM TIP You don’t really upgrade to Windows Vista Enterprise, although you can from Windows Vista Business. Because it’s only available to big corporate clients, the Enterprise edition is generally installed as the first and last OS on a corporate PC.

EXAM TIP You don’t really upgrade to Windows Vista Enterprise, although you can from Windows Vista Business. Because it’s only available to big corporate clients, the Enterprise edition is generally installed as the first and last OS on a corporate PC.

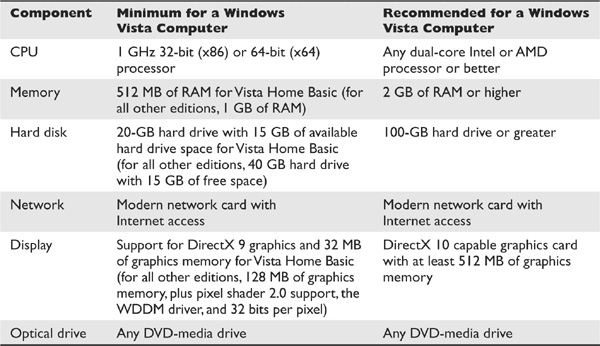

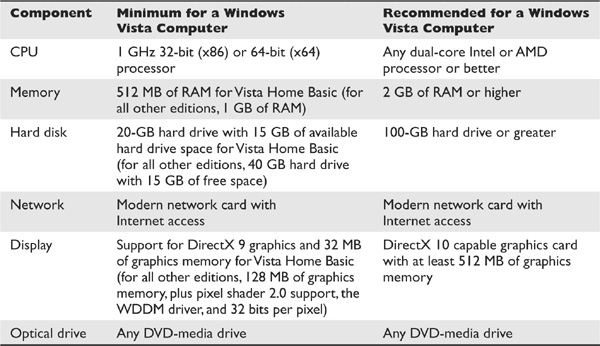

Hardware Requirements for Windows Vista

Windows Vista requires a substantially more powerful computer than XP does. Make sure your computer meets at least the minimum hardware requirements suggested by Microsoft and outlined in Table 14-3, though it would be far better to meet my recommended requirements.

Table 14-3 Windows Vista Hardware Requirements

EXAM TIP The CompTIA exams are likely to test your knowledge regarding the minimum installation requirements for Windows Vista Home Basic, Home Premium, Business, Ultimate, or Enterprise. Know them well!

EXAM TIP The CompTIA exams are likely to test your knowledge regarding the minimum installation requirements for Windows Vista Home Basic, Home Premium, Business, Ultimate, or Enterprise. Know them well!

Hardware and Software Compatibility

Windows Vista is markedly different from Windows XP in many very basic, fundamental ways, and this causes all sorts of difficulty with programs and device drivers designed for Windows XP. When Vista came out, you probably heard a lot of people grumbling about it, and likely they were grumbling about hardware and software incompatibility. Simply put, a lot of old programs and devices don’t work in Windows Vista, which is bad news for people who are still running Microsoft Word 97.

Most programs developed since Vista’s release in 2007 should work, but checking the compatibility of any programs you absolutely cannot do without is always a good idea. Because the various tools for checking compatibility with Vista have disappeared in favor of tools for Windows 7, you’ll need to check with the developers or manufacturers of your software and devices.

NOTE Software incompatibility in Vista was such a problem for many corporate customers and end users that Microsoft has included a Windows XP Mode in the higher-end editions of Windows 7, enabling most Windows XP programs to be run despite the different OS.

NOTE Software incompatibility in Vista was such a problem for many corporate customers and end users that Microsoft has included a Windows XP Mode in the higher-end editions of Windows 7, enabling most Windows XP programs to be run despite the different OS.

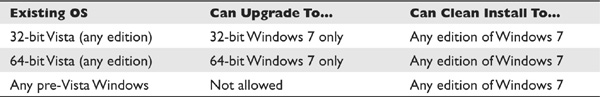

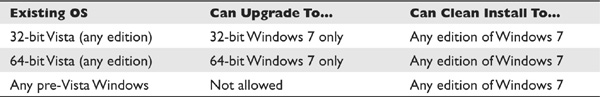

Installing or Upgrading to Windows 7

Windows 7 did not add anything new in terms of installation types. You still need to decide between a clean installation and an upgrade installation, but that’s easy to do because you can only upgrade to Windows 7 from Windows Vista—and that’s only if you have the same bit edition. In other words, you can upgrade 32-bit Vista to 32-bit Windows 7, but you can’t upgrade 32-bit Windows Vista to 64-bit Windows 7. All other Windows editions, including Windows XP Home and Professional, require a clean installation to get Windows 7. Table 14-4 outlines the upgrade paths.

Table 14-4 Installing or Upgrading to Windows 7

If you have Windows 7 and you want to upgrade to a higher edition with more features—from Windows 7 Home Premium to Windows 7 Ultimate, for example—you can use the built-in Windows Anytime Upgrade feature. You can find this option pinned to the Start menu. Don’t forget your credit card!

Hardware Requirements for Windows 7

With Windows 7, Microsoft released a single list of system requirements, broken down into 32-bit and 64-bit editions. Quoting directly from Microsoft’s Windows 7 Web site, the requirements are as follows:

• 1 gigahertz (GHz) or faster 32-bit (x86) or 64-bit (x64) processor

• 1 gigabyte (GB) RAM (32-bit) or 2 GB RAM (64-bit)

• 16 GB available hard disk space (32-bit) or 20 GB (64-bit)

• DirectX 9 graphics device with WDDM 1.0 or higher driver

NOTE Windows 7 has incredibly humble minimum requirements. Today, a low-end desktop computer will have 4 GB of RAM, a processor around 2 GHz, approximately a terabyte of hard drive space, and a DirectX 11 video card with 256 or even 512 MB of graphics memory.

NOTE Windows 7 has incredibly humble minimum requirements. Today, a low-end desktop computer will have 4 GB of RAM, a processor around 2 GHz, approximately a terabyte of hard drive space, and a DirectX 11 video card with 256 or even 512 MB of graphics memory.

Make sure you memorize the list of requirements. Microsoft also added a fairly extensive list of additional requirements that vary based on the edition of Windows 7 you use. From the same Web site, they include (author’s comments in brackets):

• Internet access (fees may apply). [You need Internet access to activate, register, and update the system easily.]

• Depending on resolution, video playback may require additional memory and advanced graphics hardware.

• Some games and programs might require a graphics card compatible with DirectX 10 or higher for optimal performance. [Video has improved dramatically over the years, and DirectX 9 dates back to 2004. Many games and high-definition videos need more than DirectX 9. Also, Windows Aero Desktop (aka Aero Glass) adds amazing beauty and functionality to your Desktop. You must have a video card with 128 MB of graphics memory for Aero to work.]

• For some Windows Media Center functionality a TV tuner and additional hardware may be required. [Windows Media Center works fine without a TV tuner. You can still use it to play Blu-ray Disc and DVD movies as well as video files and music. If you want to watch live TV, however, you’ll need a tuner.]

• HomeGroup requires a network and PCs running Windows 7.

• DVD/CD authoring requires a compatible optical drive. [If you want to burn something to an optical disc, you need a drive that can burn discs.]

• Windows XP Mode requires an additional 1 GB of RAM and an additional 15 GB of available hard disk space.

Windows 7 is also designed to handle multiple CPU cores and multiple CPUs. Many, if not most, modern computers use multicore processors. The 32-bit editions of Windows 7 can handle up to 32 processor cores, making it an easy fact to remember for the exams. The 64-bit editions of Windows 7 support up to 256 processor cores.

In terms of multiple physical processors (found on high-end PCs), Windows 7 Professional, Ultimate, and Enterprise can handle two CPUs, whereas Windows 7 Starter and Home Premium support only one CPU.

EXAM TIP In this chapter, you’ve learned some of the different installation procedures for Windows XP, Windows Vista, and Windows 7. Keeping them straight can be hard, but if you want to avoid being tricked on the CompTIA A+ exams, you must be able to. Review the procedures and then make sure you can identify the points of similarity and, more importantly, the differences among the three.

EXAM TIP In this chapter, you’ve learned some of the different installation procedures for Windows XP, Windows Vista, and Windows 7. Keeping them straight can be hard, but if you want to avoid being tricked on the CompTIA A+ exams, you must be able to. Review the procedures and then make sure you can identify the points of similarity and, more importantly, the differences among the three.

Upgrading Issues

A few extra steps before you pop in that installation disc are worth your time. If you plan to upgrade rather than perform a clean installation, follow these steps first:

1. Remember to check hardware and software compatibility as explained earlier in the chapter.

2. Have an up-to-date backup of your data and configuration files handy.

3. Perform a “spring cleaning” on your system by uninstalling unused or unnecessary applications and deleting old files.

4. Perform a disk scan (error-checking) and a disk defragmentation.

5. Uncompress all files, folders, and partitions.

6. Perform a virus scan, and then remove or disable all virus-checking software.

7. Disable virus checking in your system CMOS.

8. Keep in mind that if worse comes to worst, you may have to start over and do a clean installation anyway. This makes step 2 exceedingly important. Back up your data!

The Windows XP Clean Installation Process

A clean installation begins with your system set to boot to your optical drive and the Windows installation disc in the drive. You start your PC and the installation program loads (see Figure 14-5). Note at the bottom that it says to press F6 for a third-party SCSI or RAID driver. You only do this if you want to install Windows onto a strange drive and Windows does not already have the driver for that drive controller. Don’t worry about this; Windows has a huge assortment of drivers for just about every hard drive ever made, and in the rare situation where you need a third-party driver, the folks who sell you the SCSI or RAID array will tell you ahead of time.

Figure 14-5 Windows Setup text screen

NOTE When dealing with RAID (in any version of Windows), make sure you have the latest drivers on hand for the installation. Put them on a thumb drive just in case the Windows installer can’t detect your RAID setup.

NOTE When dealing with RAID (in any version of Windows), make sure you have the latest drivers on hand for the installation. Put them on a thumb drive just in case the Windows installer can’t detect your RAID setup.

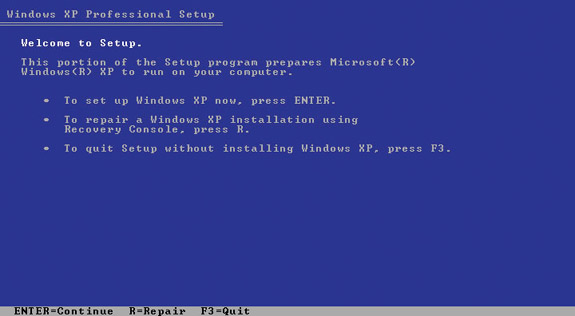

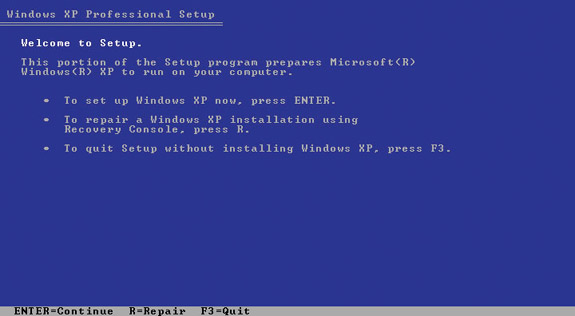

After the system copies a number of files, you’ll see the Welcome to Setup screen (see Figure 14-6). This is an important screen! As you’ll see in later chapters, techs often use the Windows installation disc as a repair tool, and this is the screen that lets you choose between installing Windows or repairing an existing installation. Because you’re making a new install, just press ENTER.

Figure 14-6 Welcome text screen

NOTE Not all screens in the installation process are shown!

NOTE Not all screens in the installation process are shown!

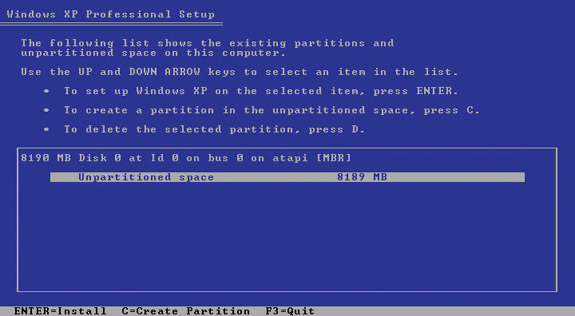

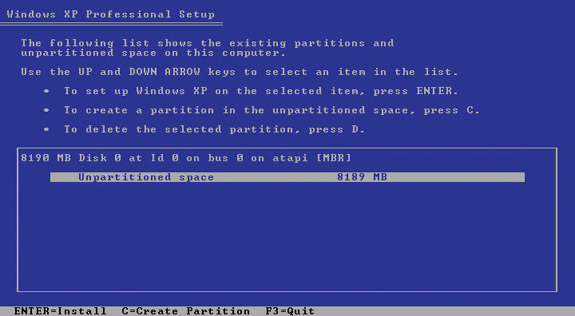

You’re now prompted to read and accept the EULA. Nobody ever reads this—it would give you a stomachache were you to see what you’re really agreeing to—so just press F8 and move to the next screen to start partitioning the drive (see Figure 14-7).

Figure 14-7 Partitioning text screen

If your hard disk is unpartitioned, you need to create a new partition when prompted. Follow the instructions. In most cases, you can make a single partition, although you can easily make as many partitions as you wish. You can also delete partitions if you’re using a hard drive that was partitioned in the past (or if you mess up your partitioning). Note that there is no option to make a primary or extended partition; this tool makes the first partition primary and the rest extended.

After you’ve made the partition(s), you must select the partition on which to install Windows XP (sort of trivial if you only have one partition), and then you need to decide which file system format to use for the new partition.

NOTE Many techie types, at least those with big (> 500 GB) hard drives, only partition half of their hard drive for Windows. This makes it easy for them to install an alternative OS (usually Linux) at a later date.

NOTE Many techie types, at least those with big (> 500 GB) hard drives, only partition half of their hard drive for Windows. This makes it easy for them to install an alternative OS (usually Linux) at a later date.

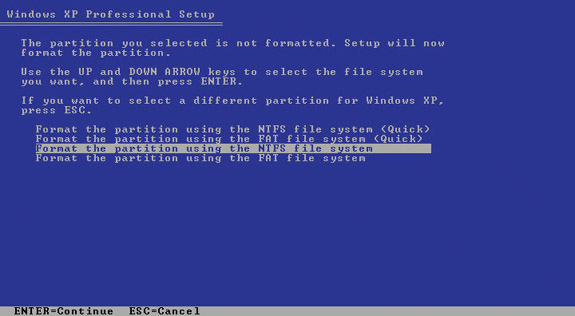

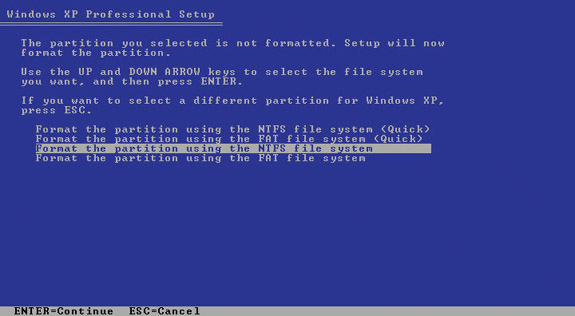

Unless you have some weird need to support FAT or FAT32, format the partition by using NTFS (see Figure 14-8).

Figure 14-8 Choosing NTFS

Setup now formats the drive and copies some basic installation files to the newly formatted partition, displaying another progress bar. Go get a book to read while you wait.

After it completes copying the base set of files to the hard drive, your computer reboots, and the graphical mode of Windows Setup begins.

You will see a generic screen during the installation that looks like Figure 14-9. On the left of the screen, uncompleted tasks have a white button, completed tasks have a green button, and the current task has a red button. You’ll get plenty of advertising to read as you install.

Figure 14-9 Beginning of graphical mode

The following screens ask questions about a number of things the computer needs to know. They include the desired region and language the computer will operate in, your name and organization for personalizing your computer, and a valid product key for Windows XP (see Figure 14-10). The product key helps reduce piracy of the software. Be sure to enter the product key exactly, or you will be unable to continue.

Figure 14-10 Product key

NOTE Losing your product key is a bad idea! Document it—at least write it on the installation disc.

NOTE Losing your product key is a bad idea! Document it—at least write it on the installation disc.

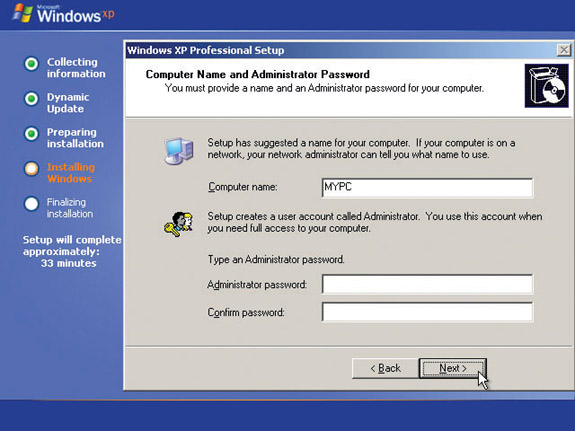

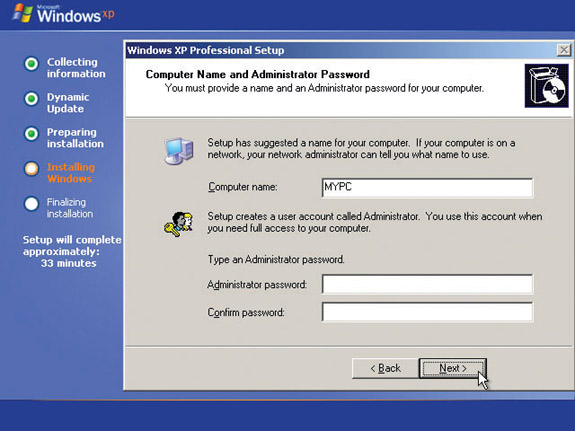

Next, you need to give your computer a name that will identify it on a network. Check with your system administrator for an appropriate name. If you don’t have a system administrator, just enter a simple name such as MYPC for now—you can change this at any time. You also need to create a password for the Administrator user account (see Figure 14-11). Every Windows system has an Administrator user account that can do anything on the computer. Techs will need this account to modify and fix the computer in the future.

Figure 14-11 Computer name and Administrator password

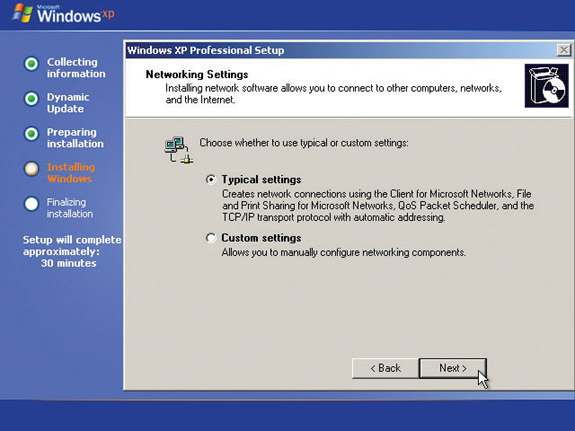

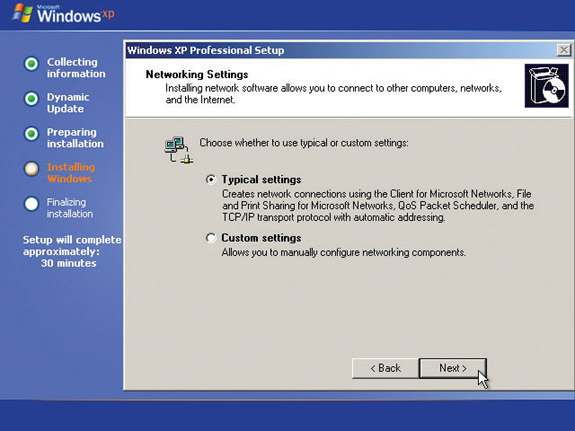

Last, you’re asked for the correct date, time, and time zone. Then Windows tries to detect a network card. If a network card is detected, the network components will be installed and you’ll have an opportunity to configure the network settings. Unless you know you need special settings for your network, just select the Typical Settings option (see Figure 14-12). Relax; XP will do most of the work for you. Plus you can easily change network settings after the installation.

Figure 14-12 Selecting typical network settings

NOTE Even experienced techs usually select the Typical Settings option. Installation is not the time to be messing with network details unless you need to.

NOTE Even experienced techs usually select the Typical Settings option. Installation is not the time to be messing with network details unless you need to.

The big copy of files now begins from the CD-ROM to your hard drive. This is a good time to pick your book up again, because watching the ads is boring (see Figure 14-13).

Figure 14-13 The Big Copy

After the files required for the final configuration are copied, XP reboots again. During this reboot, XP determines your screen size and applies the appropriate resolution. This reboot can take several minutes to complete, so be patient.

Once the reboot is complete, you can log on as the Administrator. Balloon messages may appear over the tray area of the taskbar—a common message concerns the display resolution. Click the balloon and allow Windows XP to automatically adjust the display settings.

The final message in the installation process reminds you that you have 30 days left for activation. Go ahead and activate now over the Internet or by telephone. It’s painless and quick. If you choose not to activate, simply click the Close button on the message balloon. That’s it! You have successfully installed Windows XP and should have a desktop with the default Bliss background, as shown in Figure 14-14.

Figure 14-14 Windows XP desktop with Bliss background

The Windows Vista/7 Clean Installation Process

With Windows Vista, Microsoft dramatically changed the installation process. No longer will you spend your time looking at a boring blue ASCII screen and entering commands by keyboard. The Vista installer—and the installer in Windows 7 as well—has a full graphical interface, making it easy to partition drives and install your operating system. You already saw some of this process back in Chapter 12, but this chapter will go into a bit more detail.

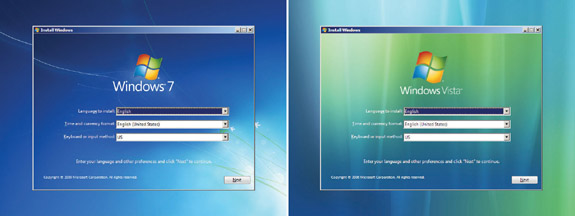

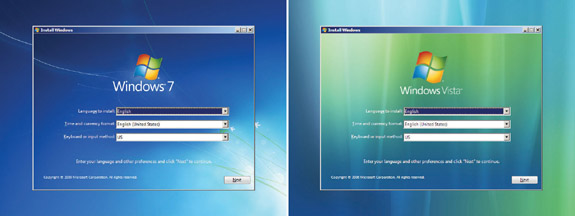

The installation methods for Windows Vista and Windows 7 are so close to identical that it would be silly to address them as separate entries in this book (see Figure 14-15). Only the splash screens and the product-key entry dialog box have changed between Windows Vista and Windows 7! Because of this trivial difference, showing the installation process for both operating systems would waste paper. This walkthrough uses the Windows Vista screenshots just because you might never see them anywhere else.

Figure 14-15 Windows 7 and Vista splash screens

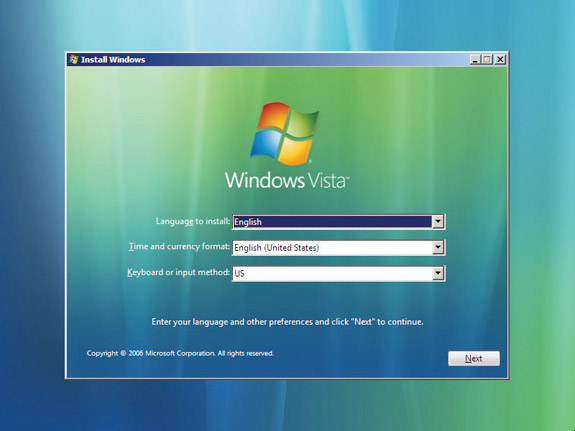

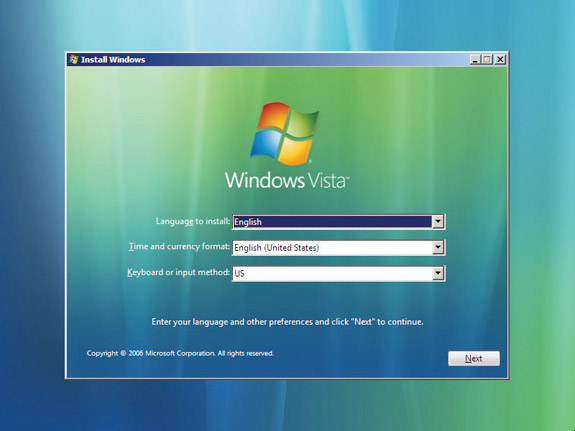

Just as when installing Windows XP, you need to boot your computer from some sort of Windows installation media. Usually, you’ll use a DVD disc, though you can also install Vista or 7 from a USB drive, over a network, or even off of several CD-ROMs that you have to specially order from Microsoft. When you’ve booted into the installer, the first screen you see asks you to set your language, time/currency, and keyboard settings, as in Figure 14-16.

Figure 14-16 Windows Vista language settings screen

The next screen in the installation process is somewhat akin to the XP Welcome to Setup text screen, in that it enables techs to start the installation disc’s repair tools (see Figure 14-17). Just like the completely revamped installer, the Vista and 7 repair tools are markedly different from the ones for Microsoft’s previous operating systems. You’ll learn more about those tools in Chapter 19, but for now all you need to know is that you click where it says Repair your computer to use the repair tools. Because you’re just installing Windows in this chapter, click Install now.

Figure 14-17 The Windows Vista setup Welcome screen

The next screen shows just how wildly different the Windows Vista and Windows 7 installation orders are. When installing Vista, you enter your product key before you do anything else, as you can see in Figure 14-18. With Windows XP (and Windows 7), this doesn’t come until much, much later in the process, and there’s a very interesting reason for this change.

Figure 14-18 The Windows Vista product key screen

Microsoft has dramatically altered the method they use to distribute different editions of their operating system; instead of having different discs for each edition of Windows Vista or Windows 7, every installation disc contains all of the available editions (except for Enterprise). In Windows XP, your product key did very little besides let the installation disc know that you had legitimately purchased the OS. In Windows Vista and Windows 7, your product key not only verifies the legitimacy of your purchase; it also tells the installer which edition you purchased, which, when you think about it, is a lot to ask of a randomly generated string of numbers and letters.

If you leave the product key blank and click the Next button, you will be taken to a screen asking you which version of Windows Vista you would like to install (see Figure 14-19). (Windows 7, however, disables this option—while every version is on the disc, you can only install the edition named on the box or disc label.) And lest you start to think that you’ve discovered a way to install Windows without paying for it, you should know that doing this simply installs a 30-day trial of the operating system. After 30 days, you will no longer be able to boot to the desktop without entering a valid product key that matches the edition of Windows Vista/7 you installed.

Figure 14-19 Choose the edition of Vista you want to install.

After the product key screen, you’ll find Microsoft’s new and improved EULA, shown in Figure 14-20, which you can skip unless you’re interested in seeing what’s changed in the world of obtuse legalese since the release of Windows XP.

Figure 14-20 The Vista EULA

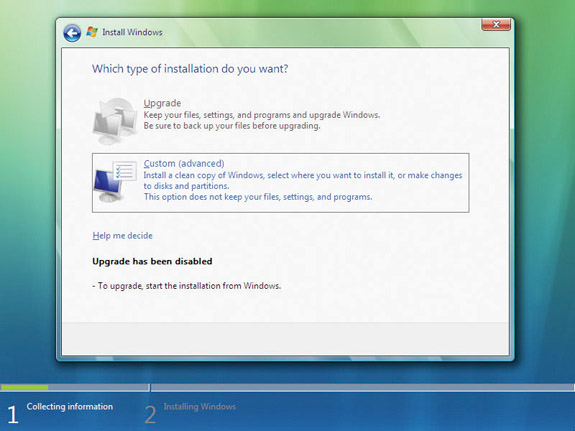

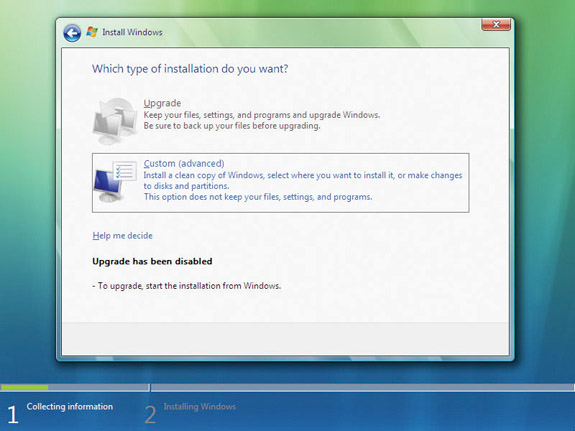

On the next page, you get to decide whether you’d like to do an upgrade installation or a clean installation (see Figure 14-21). As you learned earlier, you have to begin the Vista/7 installation process from within an older OS to use the Upgrade option, so this option will be dimmed for you if you’ve booted off of the installation disc. To do a clean installation of Vista/7, edit your partitions, and just generally install the OS like a pro, you choose the Custom (advanced) option.

Figure 14-21 Choose your installation type.

You may remember the next screen, shown in Figure 14-22, from Chapter 12. This is the screen where you can partition your hard drives and choose to which partition you’ll install Windows. From this screen, you can click the Drive options (advanced) link to display a variety of partitioning options, and you can click the Load Driver button to load alternative, third-party drivers. The process of loading drivers is much more intuitive than in Windows XP: you just browse to the location of the drivers you want by using Windows’ very familiar browsing window (see Figure 14-23).

Figure 14-22 The partitioning screen

Figure 14-23 Browse for drivers.

Of course, you will most likely never have to load drivers for a drive, and if it is ever necessary, your drive will almost certainly come with a driver disc and documentation telling you that you’ll have to load the drivers.

Once you’ve partitioned your drives and selected a partition on which to install Windows, the installation process takes over, copying files, expanding files, installing features, and just generally doing lots of computerish things. This can take a while, so if you need to get a snack or read War and Peace, do it during this part of the installation.

NOTE It doesn’t take that long to install Windows Vista. Windows 7 installation is even snappier.

NOTE It doesn’t take that long to install Windows Vista. Windows 7 installation is even snappier.

When Vista/7 has finished unpacking and installing itself, it asks you to choose a user name and picture (see Figure 14-24). This screen also asks you set up a password for your main user account, which is definitely a good idea if you’re going to have multiple people using the computer.

Figure 14-24 Choose a user picture.

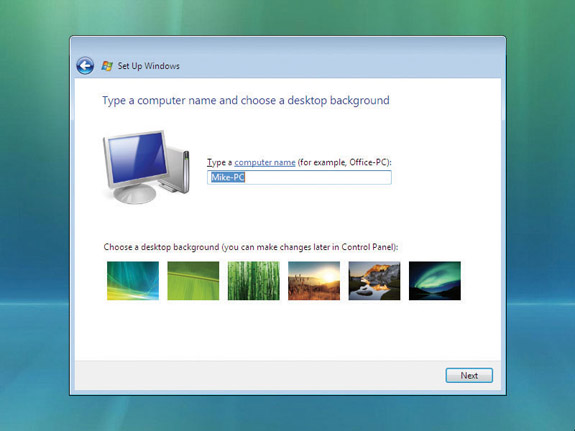

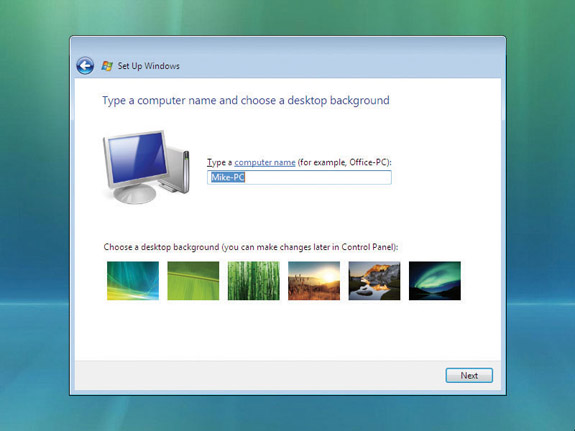

After picking your user name and password, and letting Windows know how much you like pictures of kitties, you’re taken to a screen where you can type in a computer name (see Figure 14-25). By default, Windows makes your computer name the same as your user name but with “-PC” appended to it, which in most cases is fine.

Figure 14-25 Choose your computer name.

This is also the screen where you can change the desktop background that Windows will start up with. You can change this easily later on, so pick whatever you like and click the Next button.

At this point, Windows 7 will ask for your product activation key. On Windows Vista, you did this at the beginning of the installation.

The next page asks you how you want to set up Windows Automatic Updates (see Figure 14-26). Most users want to choose the top option, Use recommended settings, as it provides the most hassle-free method for updating your computer. The middle option, Install important updates only, installs only the most critical security fixes and updates and leaves the rest of the updates up to you. This is useful when setting up computers for businesses, as many companies’ IT departments like to test out any updates before rolling them out to the employees. You should only select the last option, Ask me later, if you can dedicate yourself to checking weekly for updates, as it will not install any automatically.

Figure 14-26 The automatic updates screen

Next up is the time and date screen, where you can make sure your operating system knows what time it is, as in Figure 14-27. This screen should be pretty self-explanatory, so set the correct time zone, the correct date, and the correct time, and move to the next screen.

Figure 14-27 Vista pities the fool who doesn’t know what time it is.

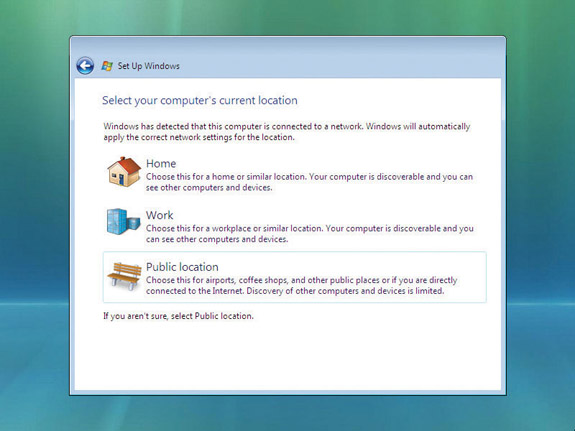

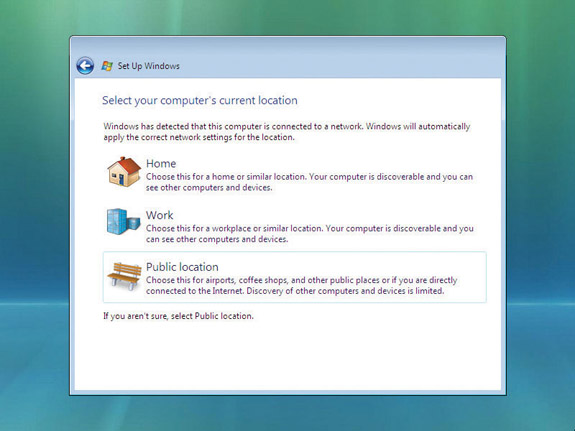

If you have your computer connected to a network while running the installer, the next screen will ask you about your current location (see Figure 14-28). If you’re on a trusted network, such as your home or office network, make the appropriate selection and your computer will be discoverable on the network. If you’re on, say, a Starbucks’ network, choose Public location so the caffeine addicts around you can’t see your computer and potentially do malicious things to it.

Figure 14-28 Tell Windows what kind of network you’re on.

Once you’re past that screen, Windows thanks you for installing it (see Figure 14-29), which is awfully polite for a piece of software, don’t you think?

Figure 14-29 Aw, shucks, Microsoft Windows Vista. Don’t mention it.

Lest you think you’re completely out of the woods, Windows will run some tests on your computer to give it a performance rating, which, in theory, will tell you how well programs will run on your computer. You’ll sometimes see minimum performance ratings on the sides of game boxes, but even then, you’re more likely to need plain, old-fashioned minimum system requirements. This process can take anywhere from 5 to 20 minutes, so this is another one of those coffee-break moments in the installation process.

Once the performance test finishes, Windows Vista or Windows 7 boots up and you have 30 days to activate your new operating system.

TIP When it comes right down to it, you don’t really need a performance rating on your computer. If you don’t want to waste your time, you can use the

TIP When it comes right down to it, you don’t really need a performance rating on your computer. If you don’t want to waste your time, you can use the ALT-F4 keyboard shortcut to skip this step.

Automating the Installation

As you can see, you may have to sit around for quite a while when installing Windows. Instead of sitting there answering questions and typing in product keys, wouldn’t it be nice just to boot up the machine and have the installation process finish without any intervention on your part—especially if you have 30 PCs that need to be ready to go tomorrow morning? Fortunately, Windows offers two good options for automating the installation process: scripted installations and disk cloning.

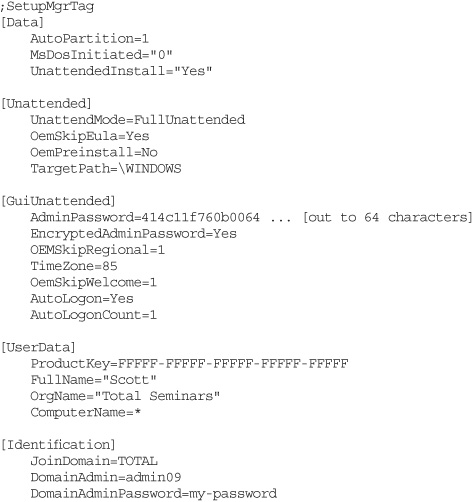

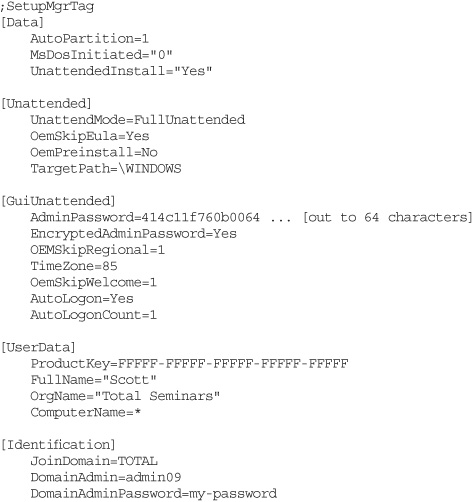

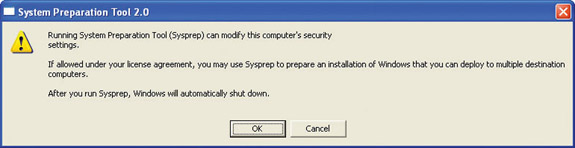

Scripting Windows XP Installations with Setup Manager

For automating a Windows XP install, Microsoft provides Setup Manager to help you create a text file—called an answer file—containing all of your answers to the installation questions. This enables you to do an unattended installation, which means you don’t have to sit in front of each computer throughout the installation process.

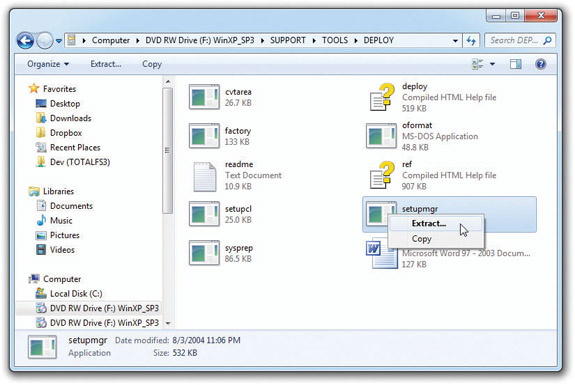

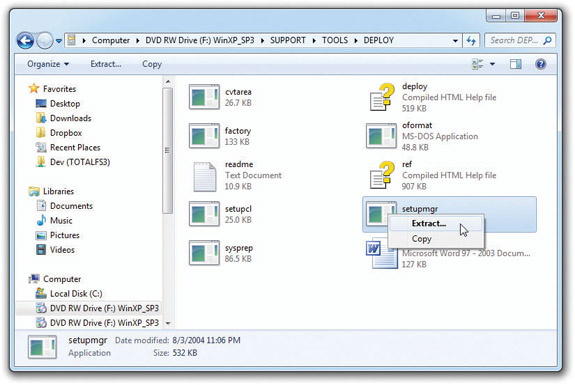

You can find Setup Manager on the Windows installation disc in the \Support\Tools folder. Double-click the DEPLOY cabinet file, and then right-click setupmgr.cab and select Extract (see Figure 14-30). Choose a location for the file.

Figure 14-30 Extracting Setup Manager from the DEPLOY cabinet file

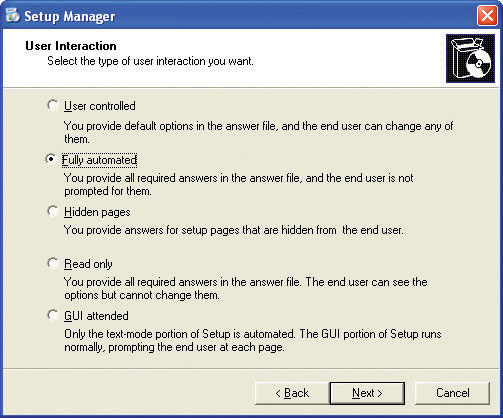

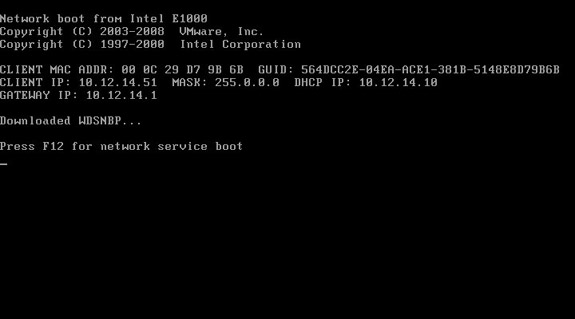

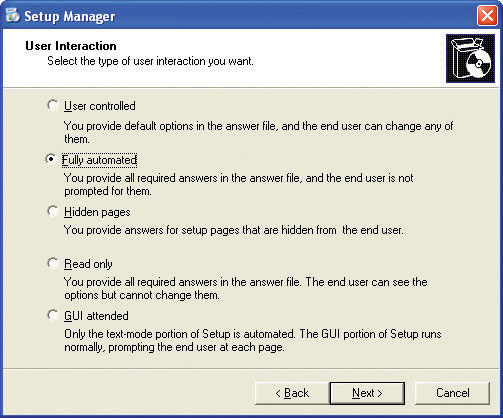

Setup Manager supports creating answer files for three types of setups: Unattended, Sysprep, and Remote Installation Services (see Figure 14-31). The latest version of the tool can create answer files for Windows XP Home Edition, Windows XP Professional, and Windows .NET (Standard, Enterprise, or Web Server); see Figure 14-32.

Figure 14-31 Setup Manager can create answer files for three types of setups.

Figure 14-32 Setup Manager can create answer files for five versions of Windows.

Setup Manager can create an answer file to completely automate the process, or you can use it to set default options. You’ll almost always want to create an answer file that automates the entire process (see Figure 14-33).

Figure 14-33 Setup Manager can create several kinds of answer files.

When running a scripted installation, you have to decide how to make the installation files themselves available to the PC. Although you can boot your new machine from an installation CD, you can save yourself a lot of CD swapping if you just put the installation files on a network share and install your OS over the network (see Figure 14-34).

Figure 14-34 Choose where to store the installation files.

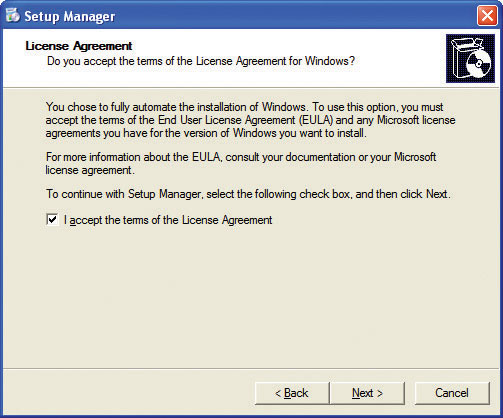

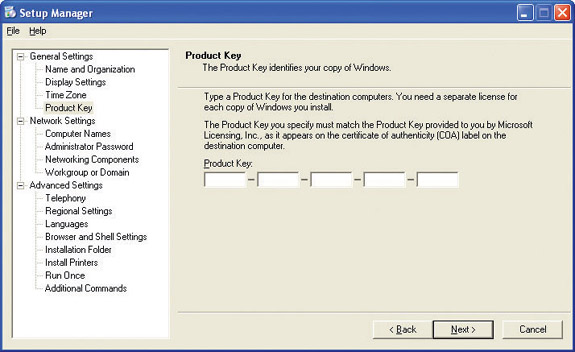

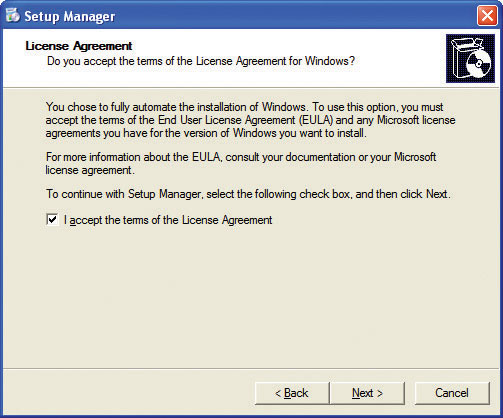

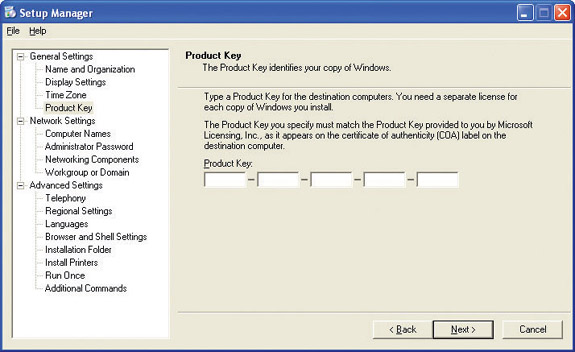

When you run Setup Manager, you get to answer all those pesky questions. As always, you will also have to “accept the terms of the License Agreement” (see Figure 14-35) and specify the product key (see Figure 14-36), but at least by scripting these steps you can do it once and get it over with.

Figure 14-35 Don’t forget to accept the license agreement.

Figure 14-36 Enter the product key.

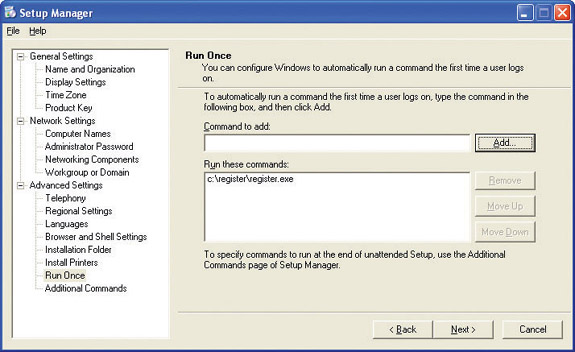

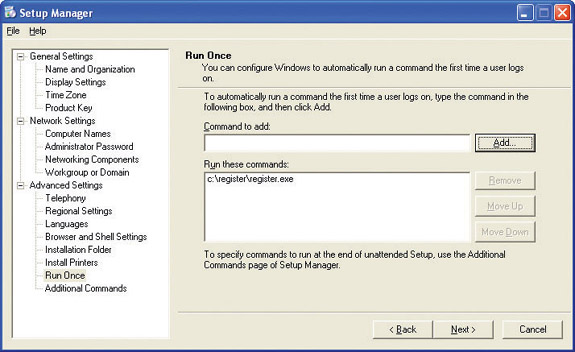

Now it’s time to get to the good stuff, customizing your installation. Using the graphical interface, decide what configuration options you want to use: screen resolutions, network options, browser settings, regional settings, and so on. You can even add finishing touches to the installation, installing additional programs such as Microsoft Office and Adobe Reader by automatically running additional commands after the Windows installation finishes (see Figure 14-37). You can also set programs to run once (see Figure 14-38).

Figure 14-37 Running additional commands

Figure 14-38 Running a program once

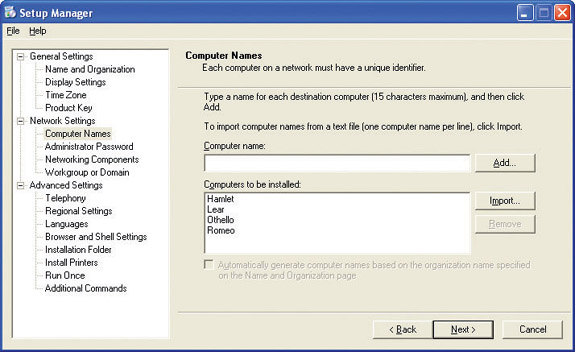

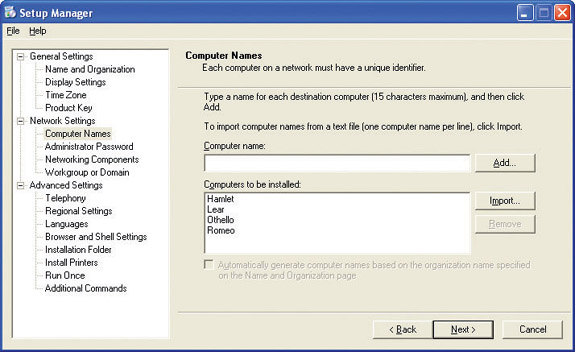

Remember that computer names must be unique on the network. If you’re going to use the same answer files for multiple machines on the same network, you need to make sure that each machine gets its own unique name. You can either provide a list of names to use, or have the Setup program randomly generate names (see Figure 14-39).

Figure 14-39 Pick your computer names.

When you’re finished, Setup Manager prompts you to save your answers as a text file. The contents of the file will look something like this:

The list goes on for another hundred lines or so, and this is a fairly simple answer file. One thing to note is that if you provide a domain administrator’s user name and password for the purpose of automatically adding new PCs to your domain, that user name and password will be in the text file in clear text:

In that case, you will want to be very careful about protecting your setup files. Once you have your answer file created, you can start your installation with this command, and go enjoy a nice cup of coffee while the installation runs:

For %SetupFiles%, substitute the location of your setup files—either a local path (D:\i386 if you are installing from a CD) or a network path. If you use a network path, don’t forget to create a network boot disk so that the installation program can access the files. For %AnswerFile%, substitute the name of the text file you created with Setup Manager (usually unattend.txt).

Of course, you don’t have to use Setup Manager to create your answer file. Feel free to pull out your favorite text editor and write one from scratch. Most techs, however, find it much easier to use the provided tool than to wrestle with the answer file’s sometimes arcane syntax.

Automating a Windows Vista or Windows 7 Installation with the Automated Installation Kit

As of Windows Vista and Windows 7, Setup Manager is history—as is any method of automating an installation that isn’t extremely complicated and intimidating. Microsoft has replaced Setup Manager with the Windows Automated Installation Kit (AIK), a set of tools that, although quite powerful, seems to have made something of a Faustian deal to obtain that power at the expense of usability (see Figure 14-40).

Figure 14-40 The Automated Installation Kit

Writing a step-by-step guide to creating an answer file in the AIK would almost warrant its own chapter, and as the CompTIA A+ exams don’t cover it at all, I’m not going to go into too much gory detail. I will, however, give a brief account of the process involved.

The basic idea behind the AIK is that a tech can create an answer file by using a tool called the Windows System Image Manager, and then use that answer file to build a Master Installation file that can be burned to DVD. Vista/7’s answer files are no longer simple text documents but .XML files, and the process of creating one is more complicated than it used to be. Gone are the days of simply running a wizard and modifying options as you see fit. Instead, you choose components (which represent the things you want your automated installation to do, such as create a partition, enter a certain product key, and much, much more) out of a huge, often baffling list and then modify their settings (see Figure 14-41).

Figure 14-41 The list of components in the Image Monitor

Once you’ve selected and modified all of the components you’re interested in, you have to save your answer file, copy it to a USB thumb drive, and plug that into a new computer on which you’re going to install Vista/7. When you boot a computer off of the installation disc, it automatically searches all removable media for an answer file, and, finding one, uses it to automatically install itself. If you’re only installing Vista/7 to this one computer, you’re finished, but if you want to install it to multiple computers, you’ll probably want to create a disc image based off of your Master Installation file.

To create such an image, you must use two more tools in the AIK—Windows PE and ImageX—to “capture” the installation and create a disc image from it. If the rest of the process seemed a bit complicated, this part is like solving a Rubik’s cube with your teeth while balancing on top of a flagpole and juggling. Suffice it to say that the AIK comes with documentation that tells you how to do this, so with a bit of patience, you can get through it.

Disk Cloning

Disk cloning simply takes an existing PC and makes a full copy of the drive, including all data, software, and configuration files. You can then transfer that copy to as many machines as you like, essentially creating clones of the original machine. In the old days, making a clone was pretty simple. You just hooked up two hard drives and copied the files from the original to the clone by using something like the venerable XCOPY program (as long as the hard drive was formatted with FAT or FAT32). Today, you’ll want to use a more sophisticated program, such as Norton Ghost, to make an image file that contains a copy of an entire hard drive and then lets you copy that image either locally or over a network.

NOTE Norton Ghost is not the only disk imaging software out there, but it is so widely used that techs often refer to disk cloning as “ghosting the drive.”

NOTE Norton Ghost is not the only disk imaging software out there, but it is so widely used that techs often refer to disk cloning as “ghosting the drive.”

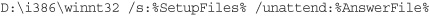

Sysprep

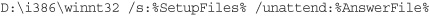

Cloning a Windows PC works great for some situations, but what if you need to send the same image out to machines that have slightly different hardware? What if you need the customer to go through the final steps of the Windows installation (creating a user account, accepting the license agreement, etc.)? That’s when you need to combine a scripted setup with cloning by using the System Preparation Tool, Sysprep, which can undo portions of the Windows installation process.

After installing Windows and adding any additional software (Microsoft Office, Adobe Acrobat, Yahoo Instant Messenger, etc.), run Sysprep (see Figure 14-42) and then create your disk image by using the cloning application of your choice. The first time a new system cloned from the image boots, an abbreviated version of setup, Mini-Setup, runs and completes the last few steps of the installation process: installing drivers for hardware, prompting the user to accept the license agreement and create user accounts, and so on. Optionally, you can use Setup Manager to create an answer file to customize Mini-Setup, just as you would with a standard scripted installation.

Figure 14-42 Sysprep, the System Preparation Tool

Installing Windows over a Network

Techs working for big corporations can end up installing Windows a lot. When you have a hundred PCs to take care of and Microsoft launches a new version of Windows, you don’t want to have to walk from cubicle to cubicle with an installation disc, running one install after the other. You already know about automated installations, but network installations take this one step further.

Imagine another scenario. You’re still a tech for a large company, but your boss has decided that every new PC will use an image with a predetermined set of applications and configurations. You need to put the image on every workstation, but most of them don’t have optical drives. Network installation saves the day again!

The phrase “network installation” can involve many different tools depending on which version of Windows you use. Most importantly, the machines that receive the installations (the clients) need to be connected to a server. That server might be another copy of Windows XP, Vista, or 7; or it might be a fully fledged server running Windows Server 2003, 2008, or 2008 R2. The serving PC needs to host an image, which can be either the default installation of Windows or a custom image, often created by the network administrator.

NOTE Windows Server 2003 uses Remote Installation Services to enable network installations, while Windows Server 2008 and 2008 R2 use Windows Deployment Services, as mentioned earlier in the chapter. Both services combine several powerful tools that enable you to customize and send installation files over the network to the client PC. These tools are aimed more at enterprise networks dealing in hundreds of PCs and are managed by network professionals.

NOTE Windows Server 2003 uses Remote Installation Services to enable network installations, while Windows Server 2008 and 2008 R2 use Windows Deployment Services, as mentioned earlier in the chapter. Both services combine several powerful tools that enable you to customize and send installation files over the network to the client PC. These tools are aimed more at enterprise networks dealing in hundreds of PCs and are managed by network professionals.

All of the server-side issues should be handled by a network administrator—setting up a server to deploy Windows installations and images goes beyond what the CompTIA A+ exams cover.

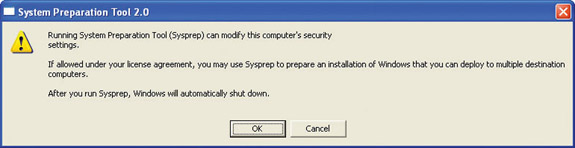

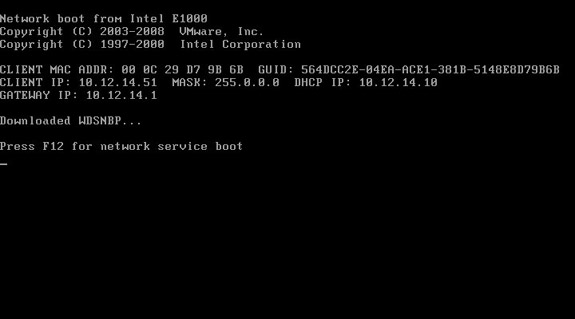

PXE

On the client side, you’ll need to use the Preboot Execution Environment (PXE). PXE uses multiple protocols such as IP, DHCP, and DNS to enable your computer to boot from a network location. That means the PC needs no installation disc or USB drive. Just plug your computer into the network and go! Okay, it’s a little more complicated than that.

Booting with PXE To enable PXE, you’ll need to enter your BIOS System Setup. Find the screen that configures your NIC (which changes depending on your particular BIOS). If there is a PXE setting there, enable it. You’ll also need to change the boot order so that the PC boots from a network location first.

NOTE Not every NIC supports PXE. To boot from a network location without PXE, you can create boot media that forces your PC to boot from a network location.

NOTE Not every NIC supports PXE. To boot from a network location without PXE, you can create boot media that forces your PC to boot from a network location.

When you reboot the PC, you’ll see the familiar first screens of the boot process. At some point, you should also see an instruction to “Press F12 for network boot.” (It’s almost always F12.) The PC will attempt to find a server on the network to which it can connect. When it does, you’ll be asked to press F12 again to continue booting from the network, as you can see in Figure 14-43.

Figure 14-43 Network boot

Depending on how many images are prepared on the server, you’ll either be taken directly to the Windows installation screen or be asked to pick from multiple images. Pick the option you need, and everything else should proceed as if you were installing Windows from the local optical drive.

Troubleshooting Installation Problems

The term “installation problem” is rather deceptive. The installation process itself almost never fails. Usually, something else fails during the process that is generally interpreted as an “install failure.” Let’s look at some typical installation problems and how to correct them.

Text Mode Errors

If you’re going to have a problem with a Windows XP installation, this is the place to get one. It’s always better to have the error right off the bat as opposed to when the installation is nearly complete. Text mode errors most often take place during clean installations and usually point to one of the following problems:

RAID Array Not Detected

If Windows fails to detect a RAID array during the text mode portion of the Windows XP installation, this could be caused by Windows not having the proper driver for the hard drive or RAID controller. If the hard drives show up properly in the RAID controller setup utility, then it’s almost certainly a driver issue. Get the driver disc from the manufacturer and run setup again. Press F6 when prompted very early in the Windows XP installation process. Nothing happens right away when you push F6, but later in the process you’ll be prompted to install.

No Boot Device Present When Booting Off the Windows Installation Disc

Either the startup disc is bad or the CMOS is not set to look at that optical drive first.

Windows Setup Requires XXXX Amount of Available Drive Space

There’s a bunch of stuff on the drive already.

Not Ready Error on Optical Drive

You probably just need to give the optical drive a moment to catch up. Press R for retry a few times. You may also have a damaged installation disc, or the optical drive may be too slow for the system.

A Stop Error (Blue Screen of Death) After the Reboot at the End of Text Mode

This may mean you didn’t do your homework in checking hardware compatibility, especially the BIOS. I’ll tell you more about stop errors in Chapter 19, but if you encounter one of these errors during installation, check out the Microsoft Knowledge Base.

Graphical Mode Errors

Graphical mode errors are found in all versions of Windows and can cause a whole new crop of problems to arise.

EXAM TIP Because partitioning and formatting occur during the graphical mode of Windows Vista and Windows 7 installation, failure to detect a RAID array points to drivers not loaded. The same driver issue applies, just like it did in Windows XP.

EXAM TIP Because partitioning and formatting occur during the graphical mode of Windows Vista and Windows 7 installation, failure to detect a RAID array points to drivers not loaded. The same driver issue applies, just like it did in Windows XP.

Hardware Detection Errors

Failure to detect hardware properly by any version of Windows Setup can be avoided by simply researching compatibility beforehand. Or, if you decided to skip that step, you might be lucky and only have a hardware detection error involving a noncritical hardware device. You can troubleshoot this problem at your leisure. In a sense, you are handing in your homework late, checking out compatibility and finding a proper driver after Windows is installed.

Every Windows installation depends on Windows Setup properly detecting the computer type (motherboard and BIOS stuff, in particular) and installing the correct hardware support. Microsoft designed Windows to run on several hardware platforms using a layer of software tailored specifically for the hardware, called the hardware abstraction layer (HAL).

Can’t Read CAB Files

This is probably the most common of all XP installation errors. CAB files (as in cabinet) are special compressed files, recognizable by their .cab file extension, that Microsoft uses to distribute copies of Windows. If your system can’t read them, first check the installation disc for scratches. Then try copying all of the files from the source directory on the disc (\i386) into a directory on your local hard drive. Then run Windows Setup from there, remembering to use the correct program (WINNT32.EXE). If you can’t read any of the files on the installation disc, you may have a defective drive.

Lockups During Installation

Lockups are one of the most challenging problems that can take place during installation, because they don’t give you a clue as to what’s causing the problem. Here are a few things to check if you get a lockup during installation.

Unplug It

Most system lockups occur when Windows Setup queries the hardware. If a system locks up once during setup, turn off the computer—literally. Unplug the system! Do not press CTRL-ALT-DEL. Do not press the Reset button. Unplug it! Then turn the system back on, boot into Setup, and rerun the Setup program. Windows will see the partial installation and restart the installation process automatically. Microsoft used to call this Smart Recovery, but the term has faded away over the years.

Optical Drive, Hard Drive

Bad optical discs, optical drives, or hard drives may cause lockups. Check the optical disc for scratches or dirt, and clean it up or replace it. Try a known good disc in the drive. If you get the same error, you may need to replace the drive.

Log Files

Windows generates a number of special text files called log files that track the progress of certain processes. Windows creates different log files for different purposes. In Windows XP, the two most important log files are

• Setuplog.txt tracks the complete installation process, logging the success or failure of file copying, Registry updates, reboots, and so on.

• Setupapi.log tracks each piece of hardware as it is installed. This is not an easy log file to read, as it uses plug and play code, but it will show you the last device installed before Windows locked up.

Windows Vista and Windows 7 create about 20 log files each, organized by the phase of the installation. Each phase, however, creates a setuperr.log file to track any errors during that phase of the installation.

Windows stores these log files in the Windows directory (the location in which the OS is installed). These operating systems have powerful recovery options, so the chances of your ever actually having to read a log file, understand it, and then get something fixed as a result of that understanding are pretty small. What makes log files handy is when you call Microsoft or a hardware manufacturer. They love to read these files, and they actually have people who understand them. Don’t worry about trying to understand log files for the CompTIA A+ exams; just make sure you know the names of the log files and their location. Leave the details to the übergeeks.

Post-Installation Tasks

You might think that’s enough work for one day, but your task list has a few more things. They include updating the OS with patches and service packs, upgrading drivers, restoring user data files, and migrating and retiring.

Patches, Service Packs, and Updates

Someone once described an airliner as consisting of millions of parts flying in close formation. I think that’s also a good description for an operating system. And we can even carry that analogy further by thinking about all of the maintenance required to keep an airliner safely flying. Like an airliner, the parts (programming code) of your OS were created by different people, and some parts may even have been contracted out. Although each component is tested as much as possible, and the assembled OS is also tested, it’s not possible to test for every possible combination of events. Sometimes a piece is simply found to be defective. The fix for such a problem is a corrective program called a patch.