CHAPTER 12

Implementing Hard Drives

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Explain the partitions available in Windows

• Discuss hard drive formatting options

• Partition and format hard drives

• Maintain and troubleshoot hard drives

From the standpoint of your PC, a freshly installed hard drive is nothing more than a huge pile of sectors. Sure, CMOS recognizes it as a drive—always a step in the right direction—but your operating system is clueless without more information. Your operating system must organize those sectors so you can use the drive to store data. This chapter covers that process.

NOTE This chapter uses the term “hard drive” as a generic term that covers all the drive types you learned about in Chapter 11. Once you get into Windows, the operating system doesn’t particularly care if the drive is a platter-based hard disk drive (HDD), a flash-based solid-state drive (SSD), or some hybrid combination of the two. The tools and steps for preparing the drives for data are the same.

NOTE This chapter uses the term “hard drive” as a generic term that covers all the drive types you learned about in Chapter 11. Once you get into Windows, the operating system doesn’t particularly care if the drive is a platter-based hard disk drive (HDD), a flash-based solid-state drive (SSD), or some hybrid combination of the two. The tools and steps for preparing the drives for data are the same.

Historical/Conceptual

After you’ve successfully installed a hard drive, you must perform two more steps to translate a drive’s geometry and circuits into something the system can use: partitioning and formatting. Partitioning is the process of electronically subdividing the physical hard drive into smaller units called partitions. A hard drive must have at least one partition, and you can create multiple partitions on a single hard drive if you wish. In Windows, each of these partitions typically is assigned a drive letter such as C: or D:. After partitioning, you must format the drive. Formatting installs a file system onto the drive that organizes each partition in such a way that the operating system can store files and folders on the drive. Several types of file systems are used by Windows. This chapter will go through them after covering partitioning.

Partitioning and formatting a drive is one of the few areas remaining on the software side of PC assembly that requires you to perform a series of fairly complex manual steps. The CompTIA A+ 220-802 exam tests your knowledge of what these processes do to make the drive work, as well as the steps needed to partition and format hard drives in Windows XP, Vista, and 7.

This chapter continues the exploration of hard drive installation by explaining partitioning and formatting and then going through the process of partitioning and formatting hard drives. The chapter wraps with a discussion on hard drive maintenance and troubleshooting issues.

Hard Drive Partitions

Partitions provide tremendous flexibility in hard drive organization. With partitions, you can organize a drive to suit your personal taste. For example, I partitioned my 1.5-terabyte (TB) hard drive into a 250-GB partition where I store Windows 7 and all my programs, a second 250-GB partition for Windows Vista, and a 1-TB partition where I store all my personal data. This is a matter of personal choice; in my case, backups are simpler because the data is stored in one partition, and I can back up that partition without including the applications.

You can partition a hard drive to store more than one operating system: store one OS in one partition and create a second partition for another OS. Granted, most people use only one OS, but if you want the option to boot to Windows or Linux, partitions are the key.

802

Windows supports three different partitioning methods: the older but more universal master boot record (MBR) partitioning scheme, Windows’ proprietary dynamic storage partitioning scheme, and the GUID partition table (GPT). Microsoft calls a hard drive that uses either the MBR partitioning scheme or the GPT partitioning scheme a basic disk and calls a drive that uses the dynamic storage partitioning scheme a dynamic disk. A single Windows system with three hard drives may have one of the drives partitioned with MBR, another with GPT, and the third set up as a dynamic disk, and the system will run perfectly well. The bottom line? You get to learn about three totally different types of partitioning! I’ll also cover a few other partition types, such as hidden partitions, tell you when you can and should make your partitions, and demystify some of Microsoft’s partition-naming confusion.

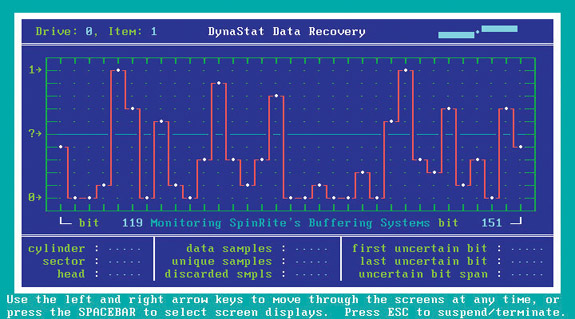

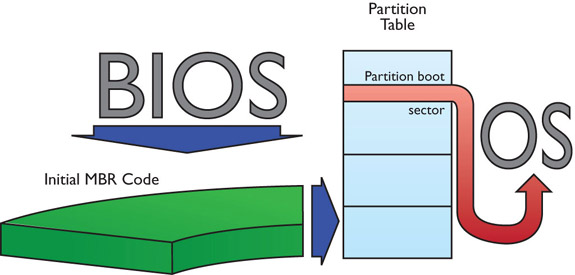

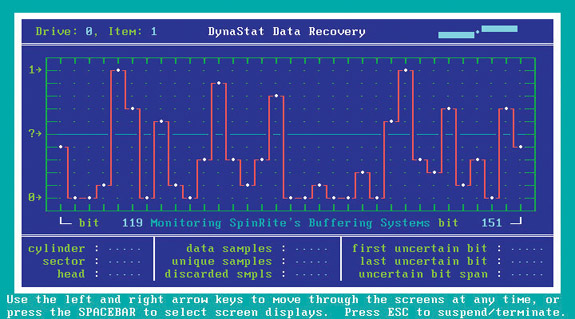

Master Boot Record

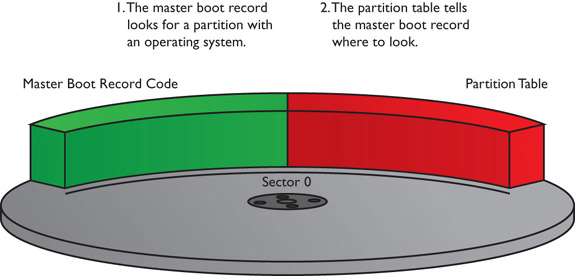

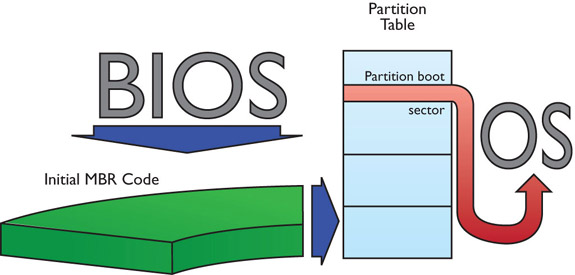

The first sector of an MBR hard drive contains the master boot record (MBR). To clarify, hard drives that use the MBR partitioning scheme have a tiny bit of data that is also called the “master boot record.” While your computer boots up, BIOS looks at the first sector of your hard drive for instructions. At this point, it doesn’t matter which OS you use or how many partitions you have. Without this bit of code, your OS will never load.

NOTE Techs often refer to MBR-partitioned drives as “MBR drives.” The same holds true for GPT-partitioned drives, which many techs refer to as “GPT drives.”

NOTE Techs often refer to MBR-partitioned drives as “MBR drives.” The same holds true for GPT-partitioned drives, which many techs refer to as “GPT drives.”

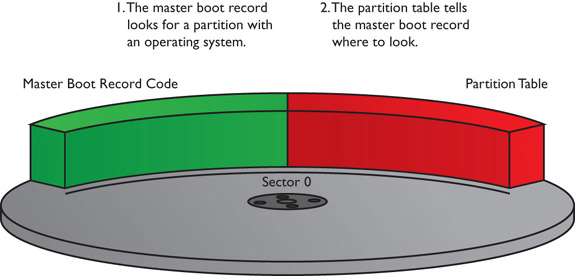

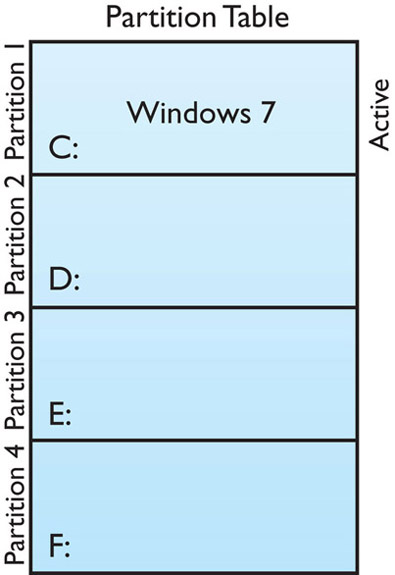

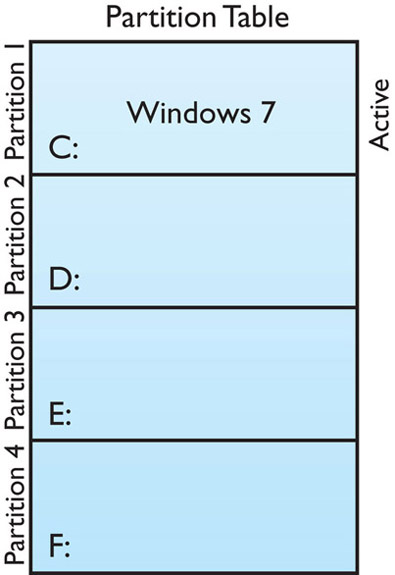

The master boot record also contains the partition table, which describes the number and size of partitions on the disk (see Figure 12-1). MBR partition tables support up to four partitions—the partition table is large enough to store entries for only four partitions. The instructions in the master boot record use this table to determine which partition contains the active operating system.

Figure 12-1 The master boot record

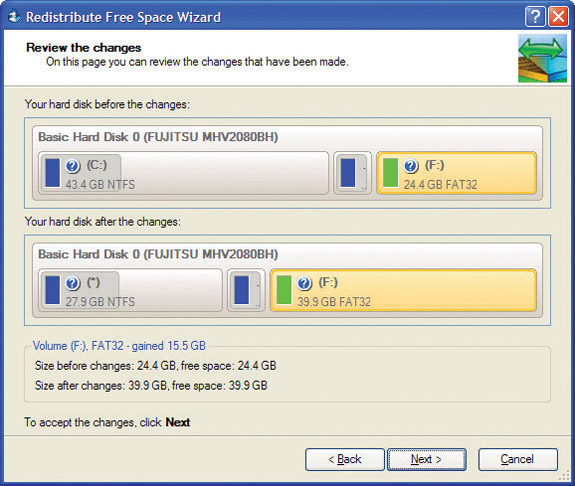

After the MBR locates the appropriate partition, the partition boot sector loads the OS on that partition. The partition boot sector stores information important to its partition, such as the location of the OS boot files (see Figure 12-2).

Figure 12-2 Using the master boot record to boot an OS

EXAM TIP Only one master boot record and one partition table within that master boot record exist per MBR disk. Each partition has a partition boot sector.

EXAM TIP Only one master boot record and one partition table within that master boot record exist per MBR disk. Each partition has a partition boot sector.

MBR partition tables support two types of partitions: primary partitions and extended partitions. Primary partitions are designed to support bootable operating systems. Extended partitions are not bootable. A single MBR disk may have up to four primary partitions or three primary partitions and one extended partition.

Primary Partitions and Multiple operating Systems

Primary partitions are usually assigned drive letters and appear in My Computer/Computer (once you format them). The first primary partition in Windows is always C:. After that, you can label the partitions D: through Z:.

NOTE Partitions don’t always get drive letters. See the section “Mounting Partitions as Folders” later in this chapter for details.

NOTE Partitions don’t always get drive letters. See the section “Mounting Partitions as Folders” later in this chapter for details.

Only primary partitions can boot operating systems. On an MBR disk, you can easily install four different operating systems, for example, each OS on its own primary partition, and boot to your choice each time you fire up the computer.

Every primary partition on a single drive has a special setting stored in the partition table called active that determines the active partition. The MBR finds the active partition and boots the operating system on that partition. Only one partition can be active at a time because you can run only one OS at a time (see Figure 12-3).

Figure 12-3 The active partition containing Windows

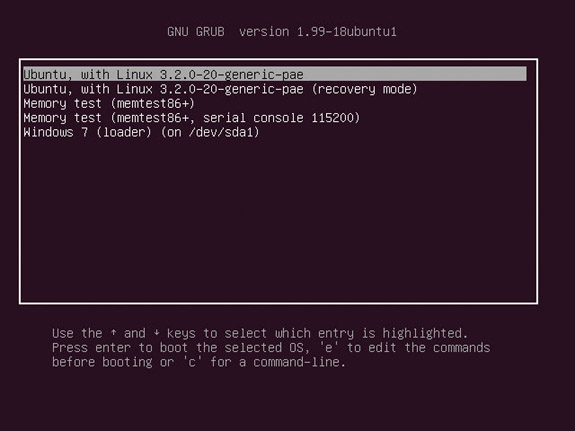

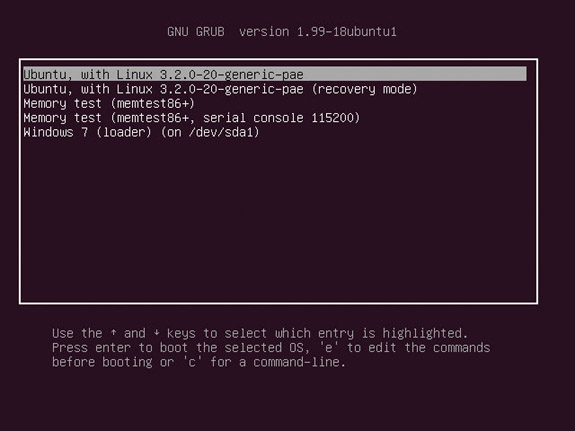

To control multiboot setups, many people use a free, Linux-based boot manager called Grand Unified Bootloader (GRUB), shown in Figure 12-4, although some people prefer Partition Commander by Avanquest Software to set up the partitions. When the computer boots, the boot manager software yanks control from the MBR and asks which OS you wish to boot. Once a partition is set as active, the partition boot sector loads the operating system.

Figure 12-4 GRUB in action

Extended Partitions

With a four-partition limit, an MBR disk would be limited to only four drive letters if using only primary partitions. An extended partition overcomes this limit. An extended partition can contain multiple logical drives, each of which can get a drive letter (see Figure 12-5).

Figure 12-5 An extended partition containing multiple logical drives

A logical drive works like a primary partition—it usually gets a drive letter such as D: or E:—but you can’t boot an OS from it. You format it just like you would a primary partition. The only difference is that each logical drive is actually in the same extended partition.

EXAM TIP Extended partitions do not receive drive letters, but the logical drives within an extended partition do.

EXAM TIP Extended partitions do not receive drive letters, but the logical drives within an extended partition do.

Dynamic Disks

With the introduction of Windows 2000, Microsoft defined an entirely new type of partitioning called dynamic storage partitioning, better known as dynamic disks. Microsoft calls a drive structure created with dynamic disk a volume. There is no dynamic disk equivalent to primary versus extended partitions. A dynamic disk volume is still technically a partition, but it can do things a regular partition cannot do.

NOTE The terms “volume” and “partition” refer to the same thing: a defined chunk of your hard drive.

NOTE The terms “volume” and “partition” refer to the same thing: a defined chunk of your hard drive.

First off, when you turn a hard drive into a dynamic disk, you can create as many volumes on it as you want. You’re not limited to four partitions.

Second, you can create—in software—new drive structures that you can’t do with MBR drives. Specifically, you can implement RAID, span volumes over multiple drives, and extend volumes on one or more drives. Table 12-1 shows you which version of Windows supports which volume type.

Table 12-1 Dynamic Disk Compatibility

EXAM TIP Only the high-end editions of each version of Windows support dynamic disks. This includes Windows XP Professional; Windows Vista Business, Ultimate, and Enterprise; and Windows 7 Professional, Ultimate, and Enterprise.

EXAM TIP Only the high-end editions of each version of Windows support dynamic disks. This includes Windows XP Professional; Windows Vista Business, Ultimate, and Enterprise; and Windows 7 Professional, Ultimate, and Enterprise.

Simple volumes work a lot like primary partitions. If you have a hard drive and you want to make half of it E: and the other half F:, for example, you create two volumes on a dynamic disk. That’s it.

Spanned volumes use unallocated space on multiple drives to create a single volume. Spanned volumes are a bit risky: if any of the spanned drives fails, the entire volume is lost.

Striped volumes are RAID 0 volumes. You may take any two unallocated spaces on two separate hard drives and stripe them. But again, if either drive fails, you lose all of your data.

Mirrored volumes are RAID 1 volumes. You may take any two unallocated spaces on two separate hard drives and mirror them. If one of the two mirrored drives fails, the other keeps running.

RAID 5 volumes, as the name implies, are for RAID 5 arrays. A RAID 5 volume requires three or more dynamic disks with equal-sized unallocated spaces.

GUID Partition Table

MBR partitioning came out a long time ago, in an age where 32-MB hard drives were more than you would ever need. While it’s lasted a long time as the partitioning standard for bootable drives, there’s a newer kid in town with the power to outshine the aging partitioning scheme and assume all the functions of the older partition style.

The globally unique identifier partition table (GPT) shares a lot with the MBR partitioning scheme, but most of the MBR scheme’s limitations have been fixed. Here are the big improvements:

• While MBR drives are limited to four partitions, a GPT drive can have an almost unlimited number of primary partitions. Microsoft has limited Windows to 128 partitions.

• MBR partitions can be no larger than 2.2 TB, but GPT partitions have no such restrictions. Well, there is a maximum size limit, but it’s so large, we measure it in zettabytes. A zettabyte, by the way, is a million terabytes.

• Remember all the lies that MBR drives had to tell BIOS so that the logical block addressing (LBA) looked like cylinder-head-sector (CHS) values? With GPT disks, the lies are over. GPT partitioning supports LBA right out of the box.

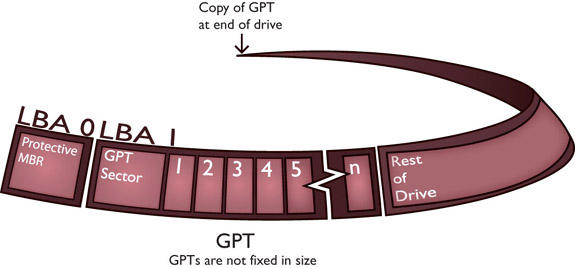

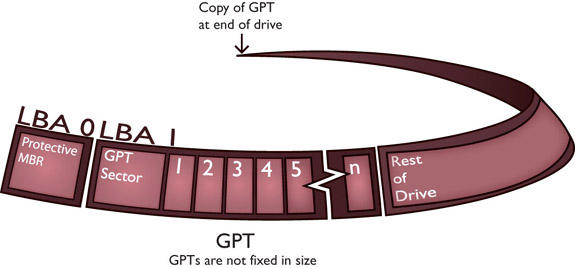

On paper, a GPT drive looks a lot like an MBR drive, except it’s arranged by LBA instead of sectors (see Figure 12-6). LBA 0, for instance, is the protective MBR. This is a re-creation of the master boot record from MBR drives so that disk utilities know it is a GPT drive and don’t mistakenly overwrite any partition data.

Figure 12-6 GUID partition table

Instead of the old master boot record and partition table, GPT drives use a GPT header and partition entry array. Both are located at the beginning and end of the drive so there is a protected backup copy. The partitions on a GPT drive go between the primary and backup headers and arrays, as shown in Figure 12-6.

You can configure only the 64-bit versions of Windows Vista and Windows 7 to boot from GPT if you use a UEFI motherboard. All other operating systems are out of luck when it comes to booting, but every current version of Windows can use GPT on additional, non-boot drives.

NOTE You first encountered UEFI back in Chapter 8 in the “Beyond A+” section. Even though UEFI is not currently on the exams, it’s important for modern techs to understand. So if you can’t recall the details, please revisit that chapter.

NOTE You first encountered UEFI back in Chapter 8 in the “Beyond A+” section. Even though UEFI is not currently on the exams, it’s important for modern techs to understand. So if you can’t recall the details, please revisit that chapter.

Other Partition Types

The partition types supported by Windows are not the only partition types you may encounter; other types exist. One of the most common is called the hidden partition. A hidden partition is really just a primary partition that is hidden from your operating system. Only special BIOS tools may access a hidden partition. Hidden partitions are used by some PC makers to hide a backup copy of an installed OS that you can use to restore your system if you accidentally trash it—by, for example, learning about partitions and using a partitioning program incorrectly.

EXAM TIP CompTIA refers to a hidden partition that contains a restorable copy of an installed OS as a factory recovery partition.

EXAM TIP CompTIA refers to a hidden partition that contains a restorable copy of an installed OS as a factory recovery partition.

A swap partition is another special type of partition, but swap partitions are found only on Linux and BSD systems. A swap partition’s only job is to act like RAM when your system needs more RAM than you have installed. Windows has a similar function with a page file that uses a special file instead of a partition, as you’ll recall from Chapter 7.

When to Partition

Partitioning is not a common task. The two most common situations likely to require partitioning are when you’re installing an OS on a new system, and when you are adding an additional drive to an existing system. When you install a new OS, the installation disc asks you how you would like to partition the drive. When you’re adding a new hard drive to an existing system, every OS has a built-in tool to help you partition it.

Each version of Windows offers a different tool for partitioning hard drives. For more than 20 years, through the days of DOS and early Windows (up to Windows Me), we used a command-line program called FDISK to partition drives. Figure 12-7 shows the FDISK program. Modern versions of Windows use a graphical partitioning program called Disk Management, shown in Figure 12-8.

Figure 12-7 FDISK

Figure 12-8 Windows 7 Disk Management tool in Computer Management

Linux uses a number of different tools for partitioning. The oldest is called FDISK—yes, the same name as the DOS/Windows version. That’s where the similarities end, however, as Linux FDISK has a totally different command set. Even though every copy of Linux comes with the Linux FDISK, it’s rarely used because so many better partitioning tools are available. One of the newer Linux partitioning tools is called GParted. See the “Beyond A+” section for more discussion on third-party partitioning tools.

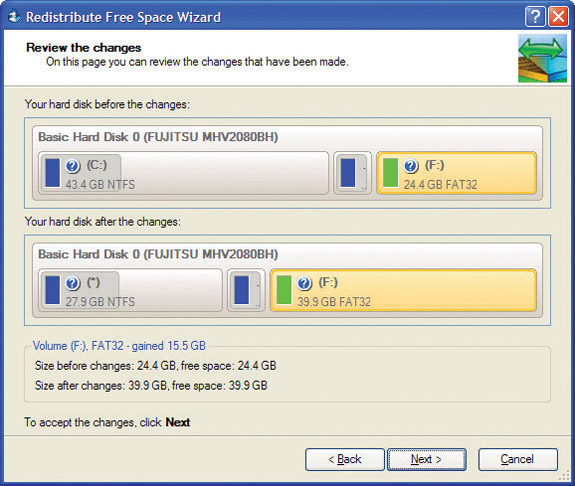

In the early days of PCs, you couldn’t change a partition’s size or type (other than by erasing it) once you’d made it with any Microsoft tools. A few third-party tools, led by PartitionMagic, gave techs the tools to resize partitions without losing the data they held.

Current Microsoft tools have more flexibility than the older tools that came with DOS and Windows. Windows XP can nondestructively resize a partition to be larger, but not smaller. In Windows Vista and Windows 7, you can nondestructively resize partitions by shrinking or expanding existing partitions with available free space.

Partition Naming Problems

So far, you’ve learned that MBR and GPT disks use partitions and dynamic disks use volumes. Unfortunately, Windows Vista and Windows 7 foul up this perfectly clear distinction when you use the Disk Management utility. Here’s the scoop.

When you create a drive structure on an MBR or GPT disk, you create a partition, regardless of which operating system you use. Figure 12-9 shows the partitioning tool in Windows XP with the properly named partitions—primary and extended—and the logical drives in the extended partition. They’re shaded gray so you can readily see the different structures.

Figure 12-9 Windows XP very clearly showing primary and extended partitions and logical drives in the extended partition

If you create a dynamic disk drive structure, Windows makes a volume. A dynamic disk volume is proprietary to Microsoft, so no other tool enables you to create them.

Both during installation and in Disk Management, the names of the partitions stay the same. It’s not that way in Windows Vista and Windows 7. During installation, everything is a partition, just like with Windows XP.

Here’s the really bad punch line. For some reason only fathomable to Microsoft marketing folks, Microsoft decided to describe the process of creating every drive structure in Windows Vista and Windows 7 in Disk Management as creating a volume (see Figure 12-10). As you’ll discover when we get to the partitioning process, you can create primary partitions, extended partitions, and logical drives in Disk Management, but you’ll create them as volumes.

Figure 12-10 New volume option

Hard Drive Formatting

Once you’ve partitioned a hard drive, you must perform one more step before your OS can use that drive: formatting. Formatting does two things: it creates a file system—like a library’s card catalog—and makes the root directory in that file system. You must format every partition and volume you create so it can hold data that you can easily retrieve. The various versions of Windows you’re likely to encounter today can use several different file systems, so we’ll look at those in detail next. The root directory provides the foundation upon which the OS builds files and folders.

NOTE If you’ve ever been to a library and walked past all of the computers connected to the Internet, down the stairs into a dark basement, you might have seen a dusty set of drawers full of cards with information about every book in the library. This is a “card catalog” system, invented over 2000 years ago. These days, you probably won’t encounter this phrase anywhere outside of explanations for formatting.

NOTE If you’ve ever been to a library and walked past all of the computers connected to the Internet, down the stairs into a dark basement, you might have seen a dusty set of drawers full of cards with information about every book in the library. This is a “card catalog” system, invented over 2000 years ago. These days, you probably won’t encounter this phrase anywhere outside of explanations for formatting.

File Systems in Windows

Every version of Windows comes with a built-in formatting utility with which to create one or more file systems on a partition or volume. The versions of Windows in current use support three separate Microsoft file systems: FAT16, FAT32, and NTFS.

The simplest hard drive file system, called FAT or FAT16, provides a good introduction to how file systems work. More complex file systems fix many of the problems inherent in FAT and add extra features as well.

FAT

The base storage area for hard drives is a sector; each sector stores up to 512 bytes of data. If an OS stores a file smaller than 512 bytes in a sector, the rest of the sector goes to waste. We accept this waste because most files are far larger than 512 bytes. So what happens when an OS stores a file larger than 512 bytes? The OS needs a method to fill one sector, find another that’s unused, and fill it, continuing to fill sectors until the file is completely stored. Once the OS stores a file, it must remember which sectors hold the file, so it can be retrieved later.

MS-DOS version 2.1 first supported hard drives using a special data structure to keep track of stored data on the hard drive, and Microsoft called this structure the file allocation table (FAT). Think of the FAT as nothing more than a card catalog that keeps track of which sectors store the various parts of a file. The official jargon term for a FAT is data structure, but it is more like a two-column spreadsheet.

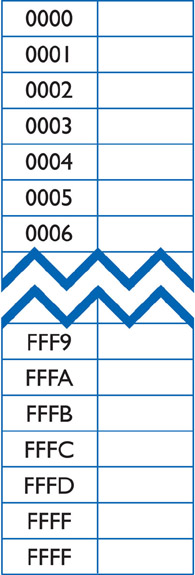

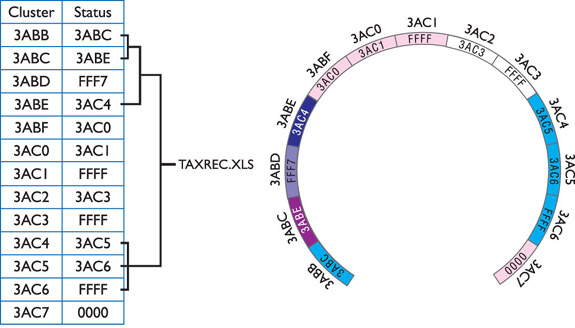

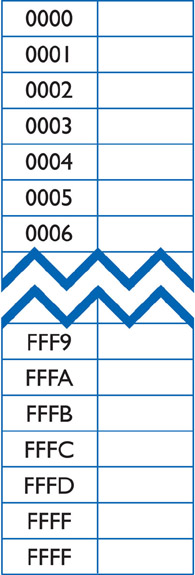

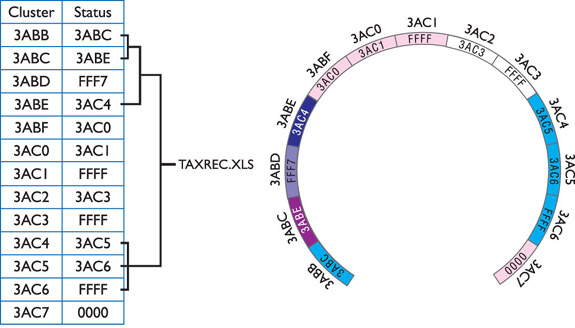

The left column (see Figure 12-11) gives each sector a hexadecimal number from 0000 to FFFF. You’ll recall from way back in Chapter 5 that each hexidecimal character represents four binary numbers or four bits. Four hex characters, therefore, represent 16 bits. If you do the math (216), you’ll find that there are 65,536 (64 K) sectors.

Figure 12-11 16-bit FAT

We call this type of FAT a 16-bit FAT or FAT16. Not just hard drives have FATs. Many USB thumb drives use FAT16. Floppy disks use FATs, but their FATs are only 12 bits because they store much less data.

The right column of the FAT contains information on the status of sectors. All hard drives, even brand-new drives fresh from the factory, contain faulty sectors that cannot store data because of imperfections in the construction of the drives. The OS must locate these bad sectors, mark them as unusable, and then prevent any files from being written to them. This mapping of bad sectors is one of the functions of high-level formatting.

After the format program creates the FAT, it proceeds through the entire partition, writing and attempting to read from each sector sequentially. If it finds a bad sector, it places a special status code (FFF7) in the sector’s FAT location, indicating that the sector is unavailable for use. Formatting also marks the good sectors as 0000.

NOTE There is such a thing as “low-level formatting,” but that’s generally done at the factory and doesn’t concern techs. This is especially true if you’re working with modern hard drives (post-2001).

NOTE There is such a thing as “low-level formatting,” but that’s generally done at the factory and doesn’t concern techs. This is especially true if you’re working with modern hard drives (post-2001).

Using the FAT to track sectors, however, creates a problem. The 16-bit FAT addresses a maximum of 64 K (216) locations. Therefore, the size of a hard drive partition should be limited to 64 K × 512 bytes per sector, or 32 MB. When Microsoft first unveiled FAT16, this 32-MB limit presented no problem because most hard drives were only 5 to 10 MB. As hard drives grew in size, you could use FDISK to break them up into multiple partitions. You could divide a 40-MB hard drive into two partitions, for example, making each partition smaller than 32 MB. But as hard drives started to become much larger, Microsoft realized that the 32-MB limit for drives was unacceptable. We needed an improvement to the 16-bit FAT, a new and improved FAT16 that would support larger drives while still maintaining backward compatibility with the old-style 16-bit FAT. This need led to the development of a dramatic improvement in FAT16, called clustering, that enabled you to format partitions larger than 32 MB (see Figure 12-12). This new FAT16 appeared way back in the DOS-4 days.

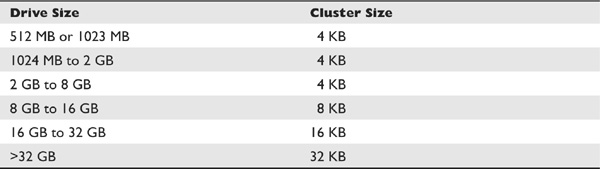

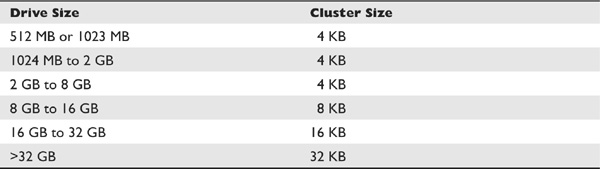

Figure 12-12 Cluster versus sector

Clustering simply refers to combining a set of contiguous sectors and treating them as a single unit in the FAT. These units are called file allocation units or clusters. Each row of the FAT addressed a cluster instead of a sector. Unlike sectors, the size of a cluster is not fixed. Clusters improved FAT16, but it still only supported a maximum of 64-K storage units, so the formatting program set the number of sectors in each cluster according to the size of the partition. The larger the partition, the more sectors per cluster. This method kept clustering completely compatible with the 64-K locations in the old 16-bit FAT. The new FAT16 could support partitions up to 2 GB. (The old 16-bit FAT is so old it doesn’t really even have a name—if someone says “FAT16,” they mean the newer FAT16 that supports clustering.) Table 12-2 shows the number of sectors per cluster for FAT16.

Table 12-2 FAT16 Cluster Sizes

FAT16 in Action

Assume you have a copy of Windows using FAT16. When an application such as Microsoft Word tells the OS to save a file, Windows starts at the beginning of the FAT, looking for the first space marked “open for use” (0000), and begins to write to that cluster. If the entire file fits within that one cluster, Windows places the code FFFF (last cluster) into the cluster’s status area in the FAT. That’s called the end-of-file marker. Windows then goes to the folder storing the file and adds the filename and the cluster’s number to the folder list. If the file requires more than one cluster, Windows searches for the next open cluster and places the number of the next cluster in the status area, filling and adding clusters until the entire file is saved. The last cluster then receives the end-of-file marker (FFFF).

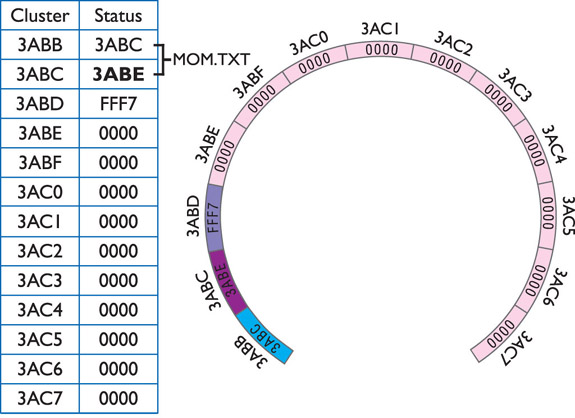

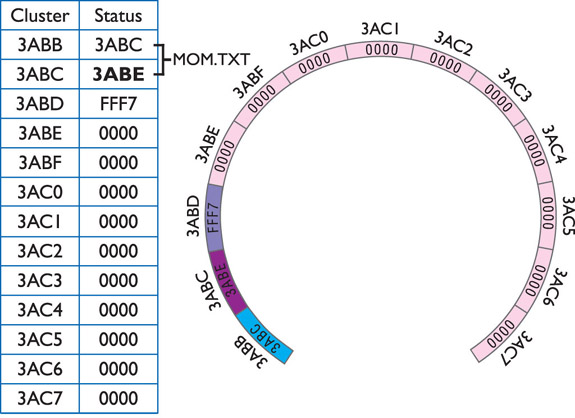

Let’s run through an example of this process, and start by selecting an arbitrary part of the FAT: from 3ABB to 3AC7. Assume you want to save a file called mom.txt. Before saving the file, the FAT looks like Figure 12-13.

Figure 12-13 The initial FAT

Windows finds the first open cluster, 3ABB, and fills it. But the entire mom.txt file won’t fit into that cluster. Needing more space, the OS goes through the FAT to find the next open cluster. It finds cluster 3ABC. Before filling 3ABC, the value 3ABC is placed in 3ABB’s status (see Figure 12-14).

Figure 12-14 The first cluster used

Even after filling two clusters, more of the mom.txt file remains, so Windows must find one more cluster. The 3ABD cluster has been marked FFF7 (bad cluster or bad-sector marker), so Windows skips over 3ABD, finding 3ABE (see Figure 12-15).

Figure 12-15 The second cluster used

Before filling 3ABE, Windows enters the value 3ABE in 3ABC’s status. Windows does not completely fill 3ABE, signifying that the entire mom.txt file has been stored. Windows enters the value FFFF in 3ABE’s status, indicating the end of file (see Figure 12-16).

Figure 12-16 End of file reached

After saving all of the clusters, Windows locates the file’s folder (yes, folders also are stored on clusters, but they get a different set of clusters, somewhere else on the disk) and records the filename, size, date/time, and starting cluster, like this:

mom.txt 19234 05-19-09 2:04p 3ABB

If a program requests that file, the process is reversed. Windows locates the folder containing the file to determine the starting cluster and then pulls a piece of the file from each cluster until it sees the end-of-file cluster. Windows then hands the reassembled file to the requesting application.

Clearly, without the FAT, Windows cannot locate files. FAT16 automatically makes two copies of the FAT. One FAT backs up the other to provide special utilities a way to recover a FAT that gets corrupted—a painfully common occurrence.

Even when FAT works perfectly, over time the files begin to separate in a process called fragmentation.

Fragmentation

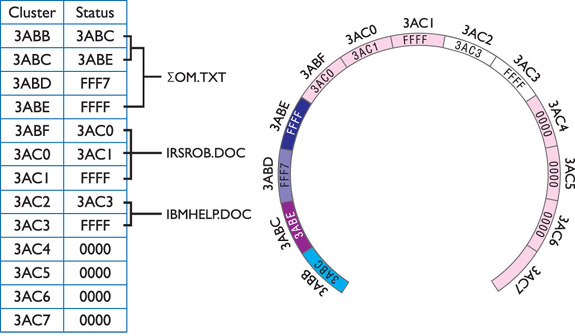

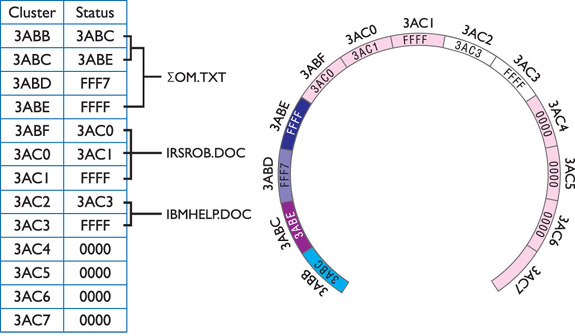

Continuing with the example, let’s use Microsoft Word to save two more files: a letter to the IRS (irsrob.doc) and a letter to IBM (ibmhelp.doc). The irsrob.doc file takes the next three clusters—3ABF, 3AC0, and 3AC1—and ibmhelp.doc takes two clusters—3AC2 and 3AC3 (see Figure 12-17).

Figure 12-17 Three files saved

Now suppose you erase mom.txt. Windows does not delete the cluster entries for mom.txt when it erases a file. Windows only alters the information in the folder, simply changing the first letter of mom.txt to the Greek letter Σ (sigma). This causes the file to “disappear” as far as the OS knows. It won’t show up, for example, in Windows Explorer, even though the data still resides on the hard drive for the moment (see Figure 12-18).

Figure 12-18 The mom.txt file erased

Note that under normal circumstances, Windows does not actually delete files when you press the DELETE key. Instead, Windows moves the files to a special hidden directory that you can access via the Recycle Bin. The files themselves are not actually deleted until you empty the Recycle Bin. (You can skip the Recycle Bin entirely if you wish, by highlighting a file and then holding down the SHIFT key when you press DELETE.)

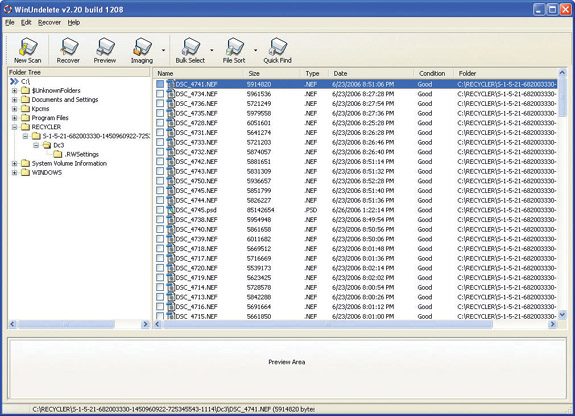

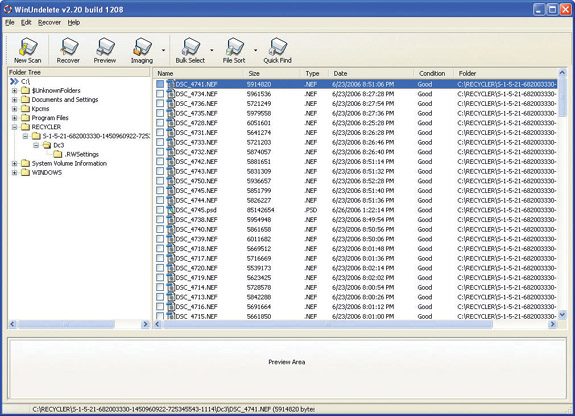

Because all of the data for mom.txt is intact, you could use some program to change the Σ back into another letter and thus get the document back. A number of third-party undelete tools are available. Figure 12-19 shows one such program at work. Just remember that if you want to use an undelete tool, you must use it quickly. The space allocated to your deleted file may soon be overwritten by a new file.

Figure 12-19 WinUndelete in action

Let’s say you just emptied your Recycle Bin. You now save one more file, taxrec.xls, a big spreadsheet that will take six clusters, into the same folder that once held mom. txt. As Windows writes the file to the drive, it overwrites the space that mom.txt used, but it needs three more clusters. The next three available clusters are 3AC4, 3AC5, and 3AC6 (see Figure 12-20).

Figure 12-20 The taxrec.xls file fragmented

Notice that taxrec.xls is in two pieces, thus fragmented. Fragmentation takes place all of the time on FAT16 systems. Although the system easily negotiates a tiny fragmented file split into only two parts, excess fragmentation slows down the system during hard drive reads and writes. This example is fragmented into two pieces; in the real world, a file might fragment into hundreds of pieces, forcing the read/write heads to travel all over the hard drive to retrieve a single file. You can dramatically improve the speed at which the hard drive reads and writes files by eliminating this fragmentation.

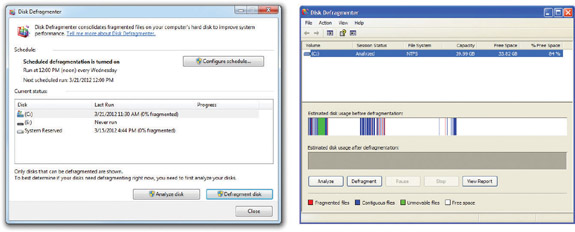

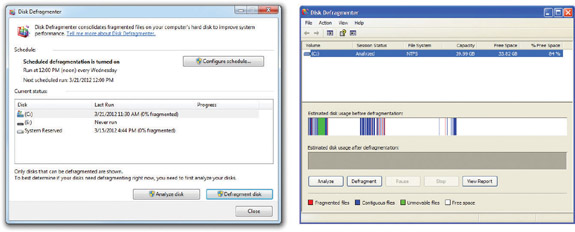

Windows comes with a program called Disk Defragmenter, which can rearrange the files into neat contiguous chunks (see Figure 12-21). Defragmentation is crucial for ensuring the top performance of a hard drive. The “Maintaining and Troubleshooting Hard Drives” section of this chapter gives the details on working with the various Disk Defragmenters in Windows.

Figure 12-21 Windows Disk Defragmenter

FAT32

When Microsoft introduced Windows 95 OSR2 (OEM Service Release 2), it also unveiled a totally new file format called FAT32 that brought a couple of dramatic improvements. First, FAT32 supports partitions up to 2 TB (more than 2 trillion bytes). Second, as its name implies, FAT32 uses 32 bits to describe each cluster, which means clusters can drop to more reasonable sizes. FAT32’s use of so many FAT entries gives it the power to use small clusters, making the old “keep your partitions small” rule obsolete. A 2-GB partition using FAT16 would use 32-KB clusters, while the same 2-GB partition using FAT32 would use 4-KB clusters. You get far more efficient use of disk space with FAT32, without the need to make multiple small partitions. FAT32 partitions still need defragmentation, however, just as often as FAT16 partitions.

Table 12-3 shows cluster sizes for FAT32 partitions.

Table 12-3 FAT32 Cluster Sizes

NTFS

The Windows format of choice these days is the New Technology File System (NTFS). NTFS came out a long time ago with the first version of Windows NT, thus the name. Over the years, NTFS has undergone a number of improvements. The version used in modern Windows is called NTFS 3.1, although you’ll see it referred to as NTFS 5.0/5.1. NTFS uses clusters and file allocation tables but in a much more complex and powerful way compared to FAT or FAT32. NTFS offers six major improvements and refinements: redundancy, security, compression, encryption, disk quotas, and cluster sizing.

NOTE If you have a geeky interest in what version of NTFS you are running, open a prompt and type this command: fsutil fsinfo ntfsinfo c:

NOTE If you have a geeky interest in what version of NTFS you are running, open a prompt and type this command: fsutil fsinfo ntfsinfo c:

NTFS Structure

NTFS utilizes an enhanced file allocation table called the master file table (MFT). An NTFS partition keeps a backup copy of the most critical parts of the MFT in the middle of the disk, reducing the chance that a serious drive error can wipe out both the MFT and the MFT copy. Whenever you defragment an NTFS partition, you’ll see a small, immovable chunk somewhere on the drive, often near the front; that’s the MFT (see Figure 12-22).

Figure 12-22 The NTFS MFT appears in a defragmenter program as the circled gray blocks.

Security

NTFS views individual files and folders as objects and provides security for those objects through a feature called the Access Control List (ACL). Future chapters go into this in much more detail.

NOTE Microsoft has never released the exact workings of NTFS to the public.

NOTE Microsoft has never released the exact workings of NTFS to the public.

Compression

NTFS enables you to compress individual files and folders to save space on a hard drive. Compression makes access time to the data slower because the OS has to uncompress files every time you use them, but in a space-limited environment, sometimes that’s what you have to do. Explorer displays filenames for compressed files in blue.

Encryption

One of the big draws with NTFS is file encryption, the black art of making files unreadable to anybody who doesn’t have the right key. You can encrypt a single file, a folder, or a folder full of files. Microsoft calls the encryption utility in NTFS the encrypting file system (EFS), but it’s simply an aspect of NTFS, not a standalone file system. You’ll learn more about encryption when you read Chapter 16.

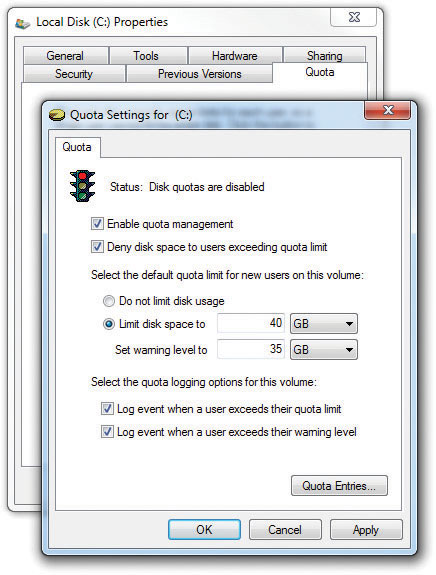

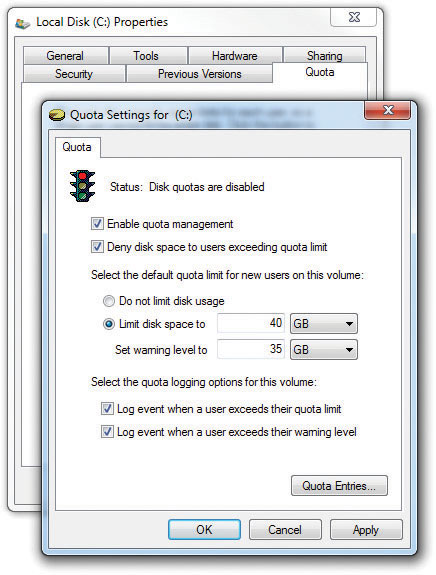

Disk Quotas

NTFS supports disk quotas, enabling administrators to set limits on drive space usage for users. To set quotas, you must log on as an Administrator, right-click the hard drive name, and select Properties. In the Drive Properties dialog box, select the Quota tab and make changes. Figure 12-23 shows configured quotas for a hard drive. Although rarely used on single-user systems, setting disk quotas on multi-user systems prevents any individual user from monopolizing your hard disk space.

Figure 12-23 Hard drive quotas in Windows 7

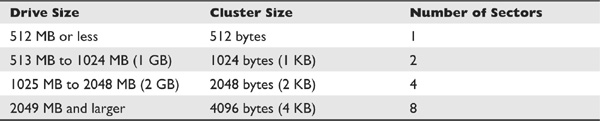

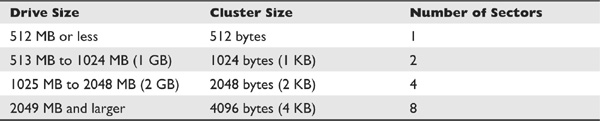

Cluster Sizes

Unlike FAT16 or FAT32, you can adjust the cluster sizes in NTFS, although you’ll probably rarely do so. Table 12-4 shows the default cluster sizes for NTFS.

Table 12-4 NTFS Cluster Sizes

By default, NTFS supports partitions up to ~16 TB on a dynamic disk (though only up to 2 TB on a basic disk). By tweaking the cluster sizes, you can get NTFS to support partitions up to 16 exabytes, or 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 bytes! That might support any and all upcoming hard drive capacities for the next 100 years or so.

EXAM TIP NTFS supports partitions up to 16 TB by default.

EXAM TIP NTFS supports partitions up to 16 TB by default.

With so many file systems, how do you know which one to use? In the case of internal hard drives, you should use the most feature-rich system your OS supports. For all modern versions of Windows, use NTFS. External hard drives still often use FAT32 because NTFS features such as the ACL and encryption can make access difficult when you move the drive between systems, but with that exception, NTFS is your best choice on a Windows-based system.

FAT64

Everyone loves USB thumb drives. Their ease of use and convenience make them indispensible for those of us who enjoy sharing a program, some photos, or a playlist. But people today want to share more than just a few small files, and they can do so with larger thumb drives. As thumb drives grow bigger in capacity, however, the file system becomes a problem.

The file system we have used for years on thumb drives, FAT32, does not work on drives larger than 2 TB. Worse, FAT32 limits file size to 4 GB. Now that you can find many thumb drives larger than 2 GB, Microsoft wisely developed a replacement for FAT32.

EXAM TIP FAT32 only supports drives up to 2 TB and only supports files up to 4 GB.

EXAM TIP FAT32 only supports drives up to 2 TB and only supports files up to 4 GB.

The newer file system, called exFAT or FAT64, breaks the 4-GB file-size barrier, supporting files up to 16 exabytes (EB) and a theoretical partition limit of 64 zettabytes (ZB). Microsoft recommends a partition size of up to 512 TB on today’s USB flash drives, which should be enough for a while. The exFAT file system extends FAT32 from 32-bit cluster entries to 64-bit cluster entries in the file table. Like FAT32, on the other hand, exFAT still lacks all of NTFS’s extra features such as permissions, compression, and encryption.

NOTE An exabyte is 260 bytes; a zettabyte is 270 bytes. For comparison, a terabyte is 240 bytes. Remember from your binary practice that each superscript number doubles the overall number, so 241 = 2 TB, 242 = 4 TB, and so on. That means a zettabyte is really, really big!

NOTE An exabyte is 260 bytes; a zettabyte is 270 bytes. For comparison, a terabyte is 240 bytes. Remember from your binary practice that each superscript number doubles the overall number, so 241 = 2 TB, 242 = 4 TB, and so on. That means a zettabyte is really, really big!

Now, if you’re like me, you might be thinking, “Why don’t we just use NTFS?” And I would say, “Good point!” Microsoft, however, sees NTFS as too powerful for what most of us need from flash drives. For example, flash drives don’t need NTFS permissions. But if for some reason you really want to format large USB thumb drives with NTFS, Windows 7 will gladly allow you to do so, as shown in Figure 12-24.

Figure 12-24 Formatting a thumb drive in Windows 7

NOTE Microsoft introduced exFAT in Windows 7, but Windows Vista with SPI also supports exFAT. Microsoft even enabled Windows XP support for exFAT with a special download (check Microsoft Knowledge Base article 955704).

NOTE Microsoft introduced exFAT in Windows 7, but Windows Vista with SPI also supports exFAT. Microsoft even enabled Windows XP support for exFAT with a special download (check Microsoft Knowledge Base article 955704).

The Partitioning and Formatting Process

Now that you understand the concepts of formatting and partitioning, let’s go through the process of setting up an installed hard drive by using different partitioning and formatting tools. If you have access to a system, try following along with these descriptions. Remember, don’t make any changes to a drive you want to keep, because both partitioning and formatting are destructive processes.

Bootable Media

Imagine you’ve built a brand-new PC. The hard drive has no OS, so you need to boot up something to set up that hard drive. Any software that can boot up a system is by definition an operating system. You need an optical disc or USB thumb drive with a bootable OS installed. Any removable media that has a bootable OS is generically called a boot device or boot disk. Your system boots off of the boot device, which then loads some kind of OS that enables you to partition, format, and install an OS on your new hard drive. Boot devices come from many sources. All Windows OS installation discs are boot devices, as are Linux installation discs.

Every boot disc or device has some kind of partitioning tool and a way to format a new partition. A hard drive has to have a partition and has to be formatted to support an OS installation.

Partitioning and Formatting with the Installation Disc

When you boot up a Windows installation disc and the installation program detects a hard drive that is not yet partitioned, it prompts you through a sequence of steps to partition (and format) the hard drive. Chapter 14 covers the entire installation process, but we’ll jump ahead and dive into the partitioning part of the installation here to see how this is done.

The partitioning and formatting tools differ between Windows XP and Windows Vista/7. Windows XP has a text-based installation tool. Windows Vista and Windows 7 use a graphical tool. But the process of setting up drives is nearly identical.

Partitioning During Windows XP Installation

The most common partitioning scenario involves turning a new blank drive into a single bootable C: drive. To accomplish this goal, you need to make the entire drive a primary partition and then make it active. Let’s go through the process of partitioning and formatting a single brand-new 1-TB hard drive.

The Windows XP installation begins by booting from a Windows installation CD-ROM like the one shown in Figure 12-25. The installation program starts automatically from the CD. The installation first loads some needed files but eventually prompts you with the screen shown in Figure 12-26. This is your clue that partitioning is about to start.

Figure 12-25 Windows installation CD

Figure 12-26 Welcome to Setup

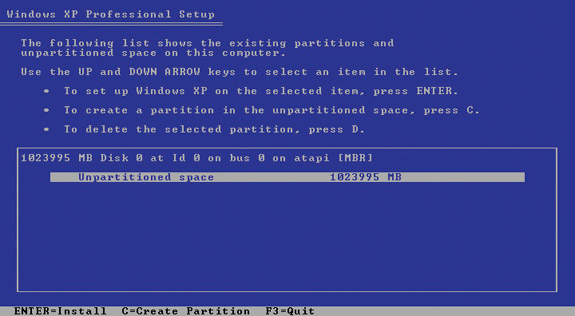

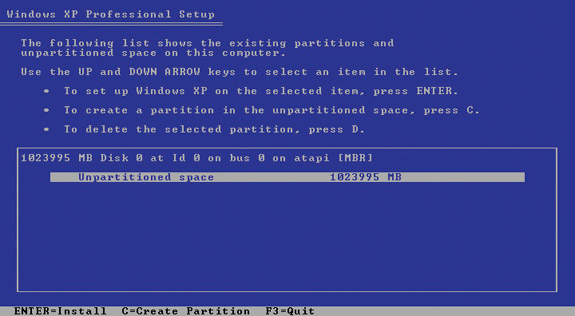

Press the ENTER key to start a new Windows installation and accept the license agreement to see the main partitioning screen (see Figure 12-27). The bar that says Unpartitioned space is the drive.

Figure 12-27 Partitioning screen

The Windows installer is pretty smart. If you press ENTER at this point, it partitions the hard drive as a single primary partition, makes it active, and installs Windows for you. That’s the type of partitioning you will do on the vast majority of installations.

As you can see on the screen, the partitioning tool also gives you the option to press c to create a partition on the drive. You can also press D to delete an existing partition.

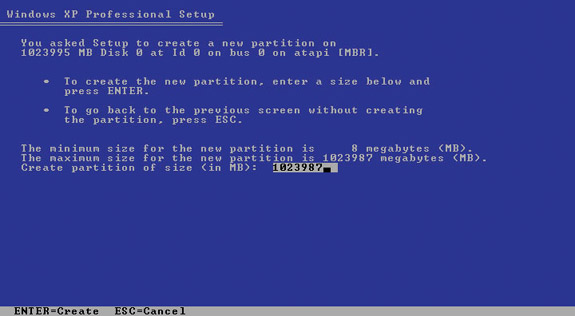

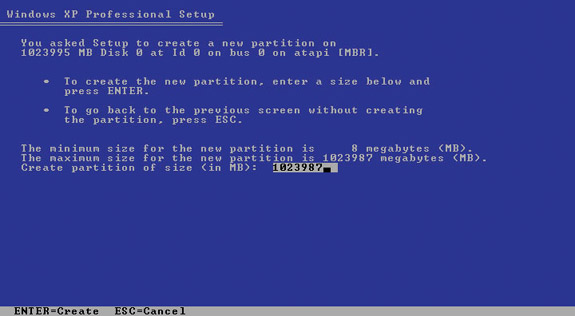

When you press c, the installer asks you how large a partition to make (see Figure 12-28). You may make the partition any size you want by erasing the current number (the whole unpartitioned space by default) and typing in a number, from a minimum of 8 MB up to the size of the entire drive. Once you have your number set, press ENTER to create the partition.

Figure 12-28 Setting partition size

If you select a size smaller than the maximum and press ENTER, you’ll see the newly created partition and the remaining drive as Unpartitioned space (see Figure 12-29). You can create more “partitions” by moving the selection bar onto the Unpartitioned space and pressing c to create a new partition. Repeat this for as many new “partitions” as you want to create.

The installer on the Windows XP disc calls all the drive structures you create at this time partitions, but what’s happening is a little different. The first partition you create will be a primary partition. The second partition you create will be automatically an extended partition. Every “partition” you create after the second will be a logical drive in the extended partition.

Figure 12-29 A newly created partition along with unpartitioned space

Once you finish partitioning, select the partition you want to use for the installation. Again, almost every time you should select C:. At that point Windows asks you how you want to format that drive (see Figure 12-30).

Figure 12-30 Format screen

So you might be asking, where’s the basic versus dynamic option? Where do you tell Windows to make the partition primary instead of extended? Where do you set it as active?

The Windows installer makes a number of assumptions for you, such as always making the first partition primary and setting it as active. The installer also makes all hard drives basic disks. You’ll have to convert a drive to dynamic later (if you even want to convert it at all).

Select NTFS for the format. Either option—quick or full—will do the job here. (Quick format is quicker, as the name would suggest, but the full option is more thorough and thus safer.) After Windows formats the drive, the installation continues, copying the new Windows installation to the C: drive.

The installation program can delete partitions just as easily as it makes them. If you use a hard drive that already has partitions, for example, you just select the partition you wish to delete and press D. This brings up a dialog box where Windows gives you one last chance to change your mind (see Figure 12-31). Press L to kill the partition.

Figure 12-31 Option to delete partition

Partitioning During Windows Vista/7 Installation

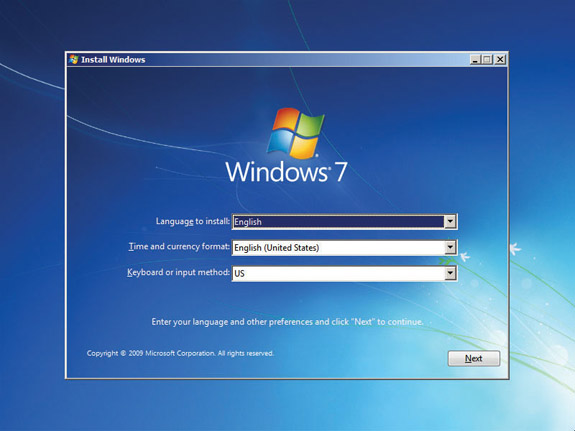

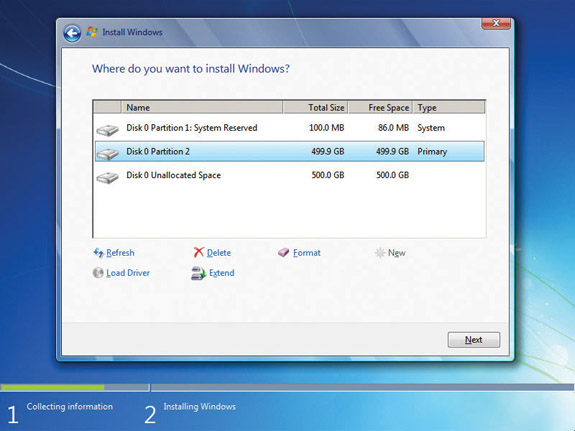

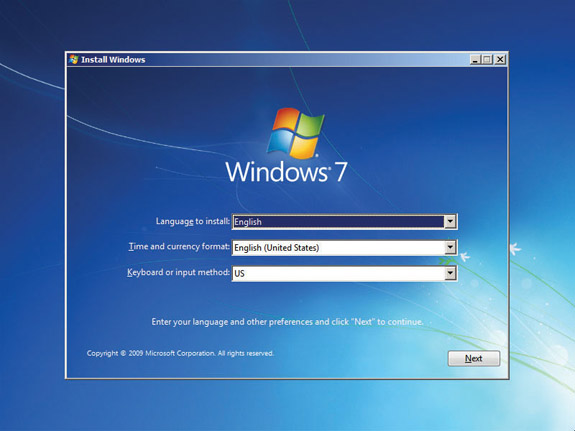

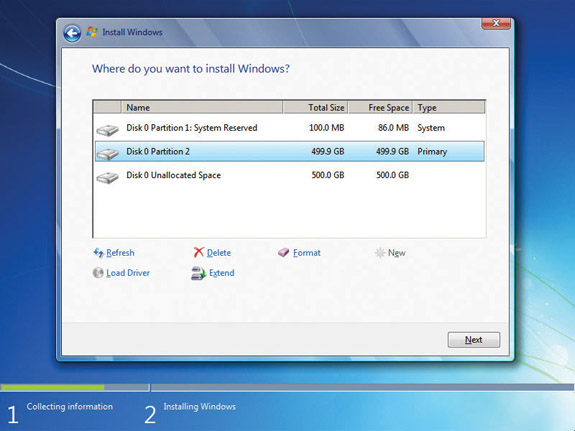

The process of partitioning and formatting with the Windows Vista or Windows 7 installation differs from the Windows XP process primarily in looks—it’s graphical—and not in function. You’ll go through a couple of installation screens (see Figure 12-32) where you select things such as language and get prompted for a product key and acceptance of the license agreement. Eventually you’ll get to the Where do you want to install Windows? dialog box (see Figure 12-33).

Figure 12-32 Starting the Windows 7 installation

Figure 12-33 Where do you want to install Windows?

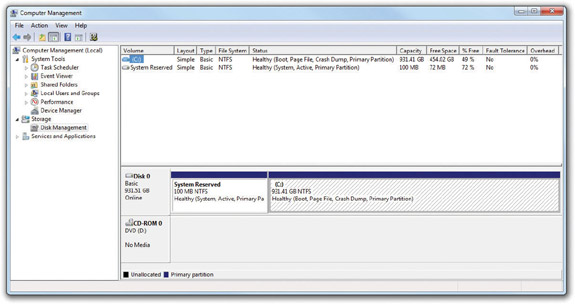

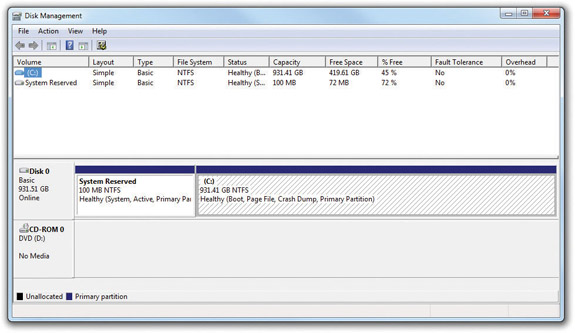

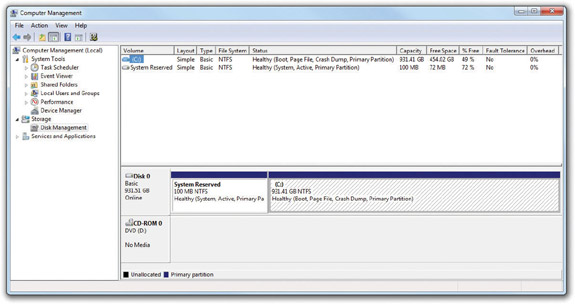

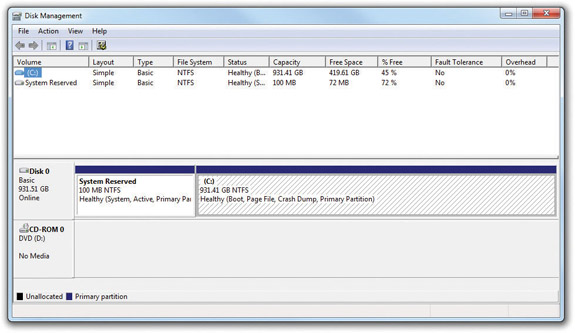

Click Next to do the most common partitioning and formatting action: creating a single C: partition, making it active, and formatting it as NTFS. Note that Windows 7 creates two partitions, a 100-MB System Reserved partition and the C: partition. This is normal, the way the system was designed to work. Figure 12-34 shows a typical Windows 7 installation in Disk Management.

Figure 12-34 Disk Management showing the default partitions in Windows 7

If you want to do any custom partitioning or delete existing partitions, you click on Drive options (advanced) in the Where do you want to install Windows? dialog box. To create a new partition, click the New button. Type in an amount in gigabytes that you want to use for a new partition, then click Apply. In Windows 7, you will get a notice that Windows might create additional partitions for system files. When you click OK, Windows will create the 100-MB System Reserved partition as well as the partition you specified (see Figure 12-35). Any leftover drive space will be listed as Unallocated Space.

Once you create a new partition, click the Format button. The installer won’t ask you what file system to use. Windows Vista and Windows 7 can read FAT and FAT32 drives, but they won’t install to such a partition by default.

The example here has a 1-TB drive with a 499-GB partition and 500 GB of unallocated space. If you’ve gone through this process and have changed your mind, wanting to make the partition use the full terabyte, what do you have to do? In Windows XP, you would have to delete the partition and start over, but not so in Windows Vista or Windows 7. You can simply click the Extend button and then apply the rest of the unallocated space to the currently formatted partition. The extend function enables you to tack unpartitioned space onto an already partitioned drive with the click of the mouse.

Figure 12-35 New 499-GB partition with 100-MB System Reserved partition and Unallocated Space

Disk Management

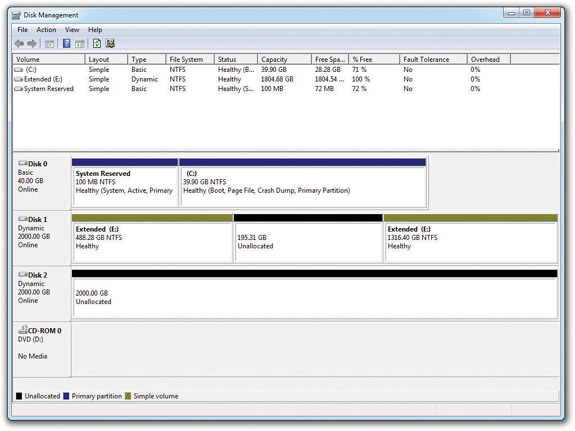

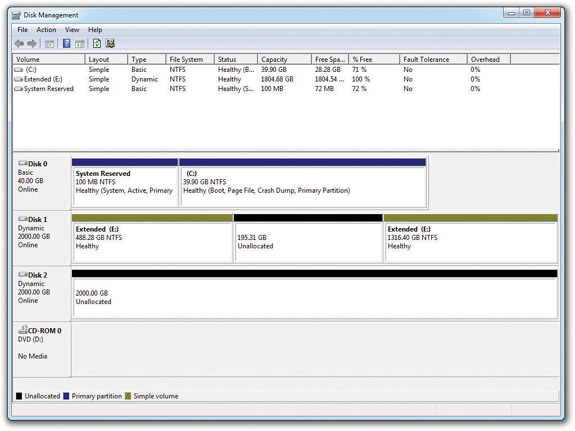

The primary tool for partitioning and formatting drives after installation is the Disk Management utility (see Figure 12-36). You can use Disk Management to do everything you want to do to a hard drive in one handy tool. You can access Disk Management by going to the Control Panel and opening the Computer Management applet. You can also click Start | Run in Windows XP and type diskmgmt.msc—or just type diskmgmt.msc in the Start menu Search bar in Windows Vista/7—and press ENTER.

EXAM TIP The CompTIA A+ 220-802 exam will test you on how to get into Disk Management. Know the ways.

EXAM TIP The CompTIA A+ 220-802 exam will test you on how to get into Disk Management. Know the ways.

Disk Initialization

Every hard drive in a Windows system has special information placed onto the drive through a process called disk initialization. This initialization information includes identifiers that say “this drive belongs in this system” and other information that defines what this hard drive does in the system. If the hard drive is part of a software RAID array, for example, its RAID information is stored in the initialization. If it’s part of a spanned volume, this is also stored there.

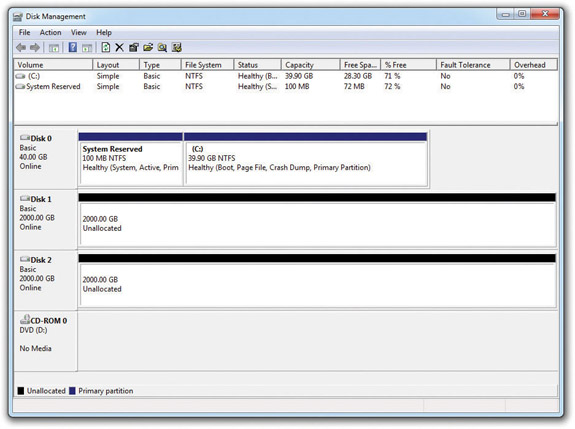

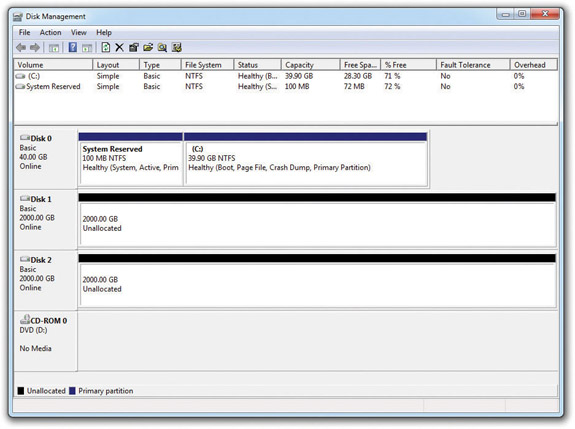

All new drives must be initialized before you can use them. When you install an extra hard drive into a Windows system and start Disk Management, it notices the new drive and starts the Hard Drive Initialization Wizard. If you don’t let the wizard run, the drive will be listed as unknown (see Figure 12-37).

Figure 12-36 Disk Management

Figure 12-37 Unknown drive in Disk Management

To initialize a disk, right-click the disk icon and select Initialize. In Windows 7 you will get the option to select MBR or GPT as a partition style. Once a disk is initialized, you can see the status of the drive—a handy tool for troubleshooting.

Disk Management enables you to view the status of every drive in your system. Hopefully, you’ll mostly see the drive listed as Healthy, meaning that nothing is happening to it and things are going along swimmingly. You’re also already familiar with the Unallocated and Active statuses, but here are a few more to be familiar with for the CompTIA A+ exams and real life as a tech:

• Foreign drive You see this when you move a dynamic disk from one computer to another.

• Formatting As you might have guessed, you see this when you’re formatting a drive.

• Failed Pray you never see this status, because it means that the disk is damaged or corrupt and you’ve probably lost some data.

• Online This is what you see if a disk is healthy and communicating properly with the computer.

• Offline The disk is either corrupted or having communication problems.

A newly installed drive is always set as a basic disk. There’s nothing wrong with using basic disks, other than that you miss out on some handy features.

Creating Partitions and Volumes in Disk Management

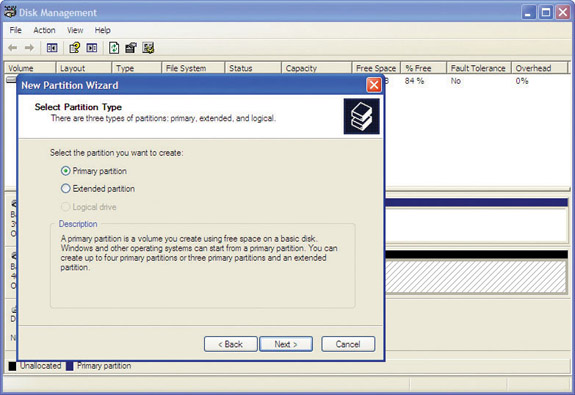

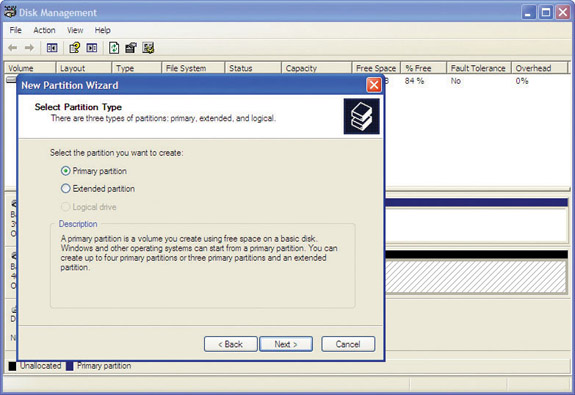

To create partitions or volumes, right-click the unallocated part of the drive and select New Partition in Windows XP or New Simple Volume in Windows Vista/7. Disk Management runs the New Partition Wizard or the New Simple Volume Wizard. In Windows XP, you’ll be asked to select a primary partition or an extended partition (see Figure 12-38). Once you do that, you’ll go to a screen where you specify the partition or volume size. Because Windows Vista and Windows 7 don’t give you the option to specify whether you want primary or extended partitions, you’ll go straight to the sizing screen (see Figure 12-39).

Figure 12-38 The New Partition Wizard in Windows XP at the Select Partition Type dialog box

Figure 12-39 Specifying the simple volume size in the New Simple Volume Wizard

Specify a partition or volume size and click Next. The wizard will ask if you want to assign a drive letter to the partition or volume, mount it as a folder to an existing partition or volume, or do neither (see Figure 12-40). In almost all cases, you’ll want to give primary partitions and simple volumes a drive letter.

Figure 12-40 Assigning a drive letter to a partition

It’s important to note here that Windows Vista and Windows 7 do not enable you to specify whether you want a primary or extended partition when you create a volume. The first three volumes you create will be primary partitions. Every volume thereafter will be a logical drive in an extended partition.

The last screen of the New Partition Wizard or New Simple Volume Wizard asks for the type of format you want to use for this partition (see Figure 12-41). If your partition is 4 GB or less, you may format it as FAT, FAT32, or NTFS. If your partition is greater than 4 GB but less than 32 GB, you can make the drive FAT32 or NTFS. Windows requires NTFS on any partition greater than 32 GB. Although FAT32 supports partitions up to 2 TB, Microsoft wants you to use NTFS on larger partitions and creates this limit. With today’s big hard drives, there’s no good reason to use anything other than NTFS.

Figure 12-41 Choosing a file system type

NOTE Windows reads and writes to FAT32 partitions larger than 32 GB; you simply can’t use Disk Management to make such partitions. If you ever stumble across a drive from a system that ran the old Windows 9x/Me that has a FAT32 partition larger than 32 GB, it will work just fine in a modern Windows system.

NOTE Windows reads and writes to FAT32 partitions larger than 32 GB; you simply can’t use Disk Management to make such partitions. If you ever stumble across a drive from a system that ran the old Windows 9x/Me that has a FAT32 partition larger than 32 GB, it will work just fine in a modern Windows system.

You have a few more tasks to complete at this screen. You can add a volume label if you want. You can also choose the size of your clusters (Allocation unit size). There’s no reason to change the default cluster size, so leave that alone—but you can sure speed up the format if you select the Perform a quick format checkbox. This will format your drive without checking every cluster. It’s fast and a bit risky, but new hard drives almost always come from the factory in perfect shape—so you must decide whether to use it or not.

Last, if you chose NTFS, you may enable file and folder compression. If you select this option, you’ll be able to right-click any file or folder on this partition and compress it. To compress a file or folder, choose the one you want to compress, right-click, and select Properties. Then click the Advanced button and turn compression on (see Figure 12-42). Compression is handy for opening up space on a hard drive that’s filling up, but it also slows down disk access, so use it only when you need it.

Figure 12-42 Turning on compression

Dynamic Disks

You create dynamic disks from basic disks in Disk Management. Once you convert a drive from a basic disk to a dynamic disk, primary and extended partitions no longer exist; dynamic disks are divided into volumes instead of partitions. This is obvious in Windows XP because the name changes. Because Window Vista and Windows 7 call partitions volumes, the change to dynamic disk isn’t obvious at all.

EXAM TIP When you move a dynamic disk from one computer to another, it shows up in Disk Management as a foreign drive. You can import a foreign drive into the new system by right-clicking the disk icon and selecting Import Foreign Disks.

EXAM TIP When you move a dynamic disk from one computer to another, it shows up in Disk Management as a foreign drive. You can import a foreign drive into the new system by right-clicking the disk icon and selecting Import Foreign Disks.

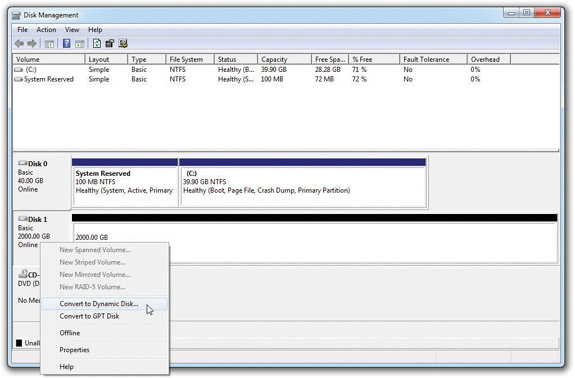

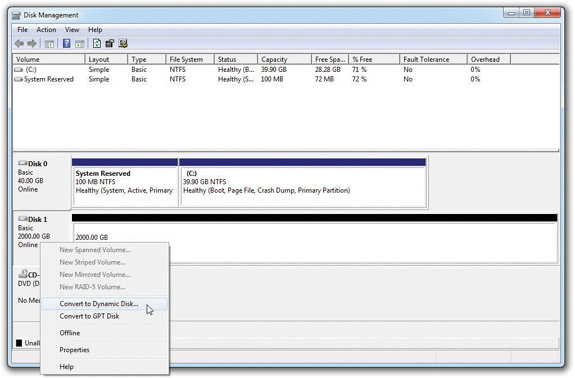

To convert a basic disk to dynamic, just right-click the drive icon and select Convert to Dynamic Disk (see Figure 12-43). The process is very quick and safe, although the reverse is not true. The conversion from dynamic disk to basic disk first requires you to delete all volumes off of the hard drive.

Figure 12-43 Converting to a dynamic disk

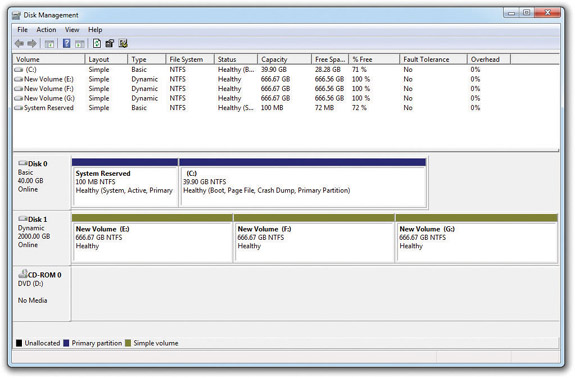

Once you’ve converted the disk, you can make one of the five types of volumes on a dynamic disk: simple, spanned, striped, mirrored, or RAID 5. You’ll next learn how to implement the three most common volume types. The final step involves assigning a drive letter or mounting the volume as a folder.

Simple Volumes A simple volume acts just like a primary partition. If you have only one dynamic disk in a system, it can have only a simple volume. It’s important to note here that a simple volume may act like a traditional primary partition, but it is very different because you cannot install an operating system on it.

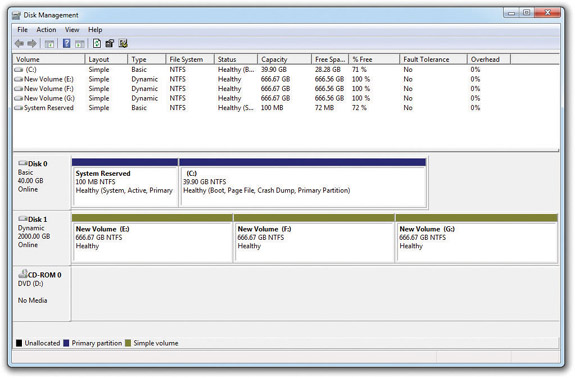

In Disk Management, right-click any unallocated space on the dynamic disk and choose New Simple Volume (see Figure 12-44) to run the New Simple Volume Wizard. You’ll see a series of screens that prompt you on size and file system, and then you’re finished. Figure 12-45 shows Disk Management with three simple volumes.

Figure 12-44 Selecting to open the New Simple Volume Wizard

Figure 12-45 Simple volumes

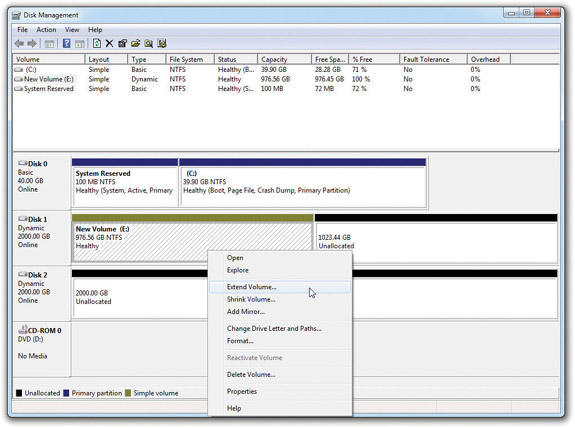

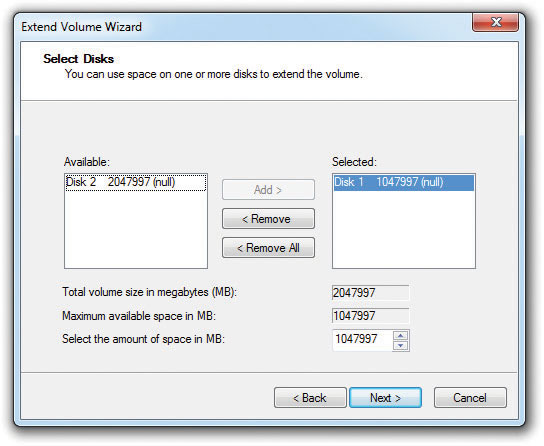

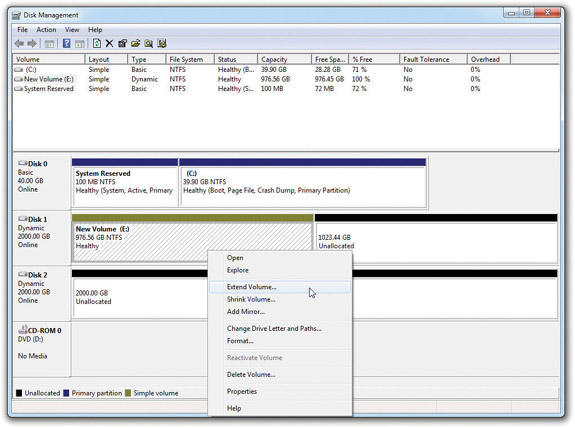

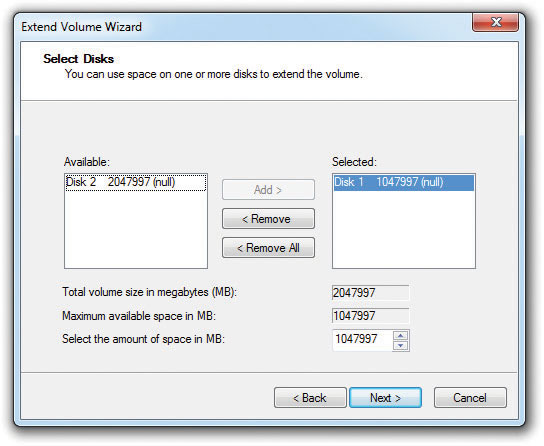

Spanning Volumes You can extend the size of a simple volume to any unallocated space on a dynamic disk. You can also extend the volume to grab extra space on completely different dynamic disks, creating a spanned volume. To extend or span, simply right-click the volume you want to make bigger, and choose Extend Volume from the options (see Figure 12-46). This opens the Extend Volume Wizard, which prompts you for the location of free space on a dynamic disk and the increased volume size you want to assign (see Figure 12-47). If you have multiple drives, you can span the volume just as easily to one of those drives.

Figure 12-46 Selecting the Extend Volume option

Figure 12-47 The Extend Volume Wizard

The capability to extend and span volumes makes dynamic disks worth their weight in gold. If you start running out of space on a volume, you can simply add another physical hard drive to the system and span the volume to the new drive. This keeps your drive letters consistent and unchanging so your programs don’t get confused, yet enables you to expand drive space when needed.

CAUTION Once you convert a drive to dynamic, you cannot revert it to a basic disk without losing all of the data on that drive. Be prepared to back up all data before you convert.

CAUTION Once you convert a drive to dynamic, you cannot revert it to a basic disk without losing all of the data on that drive. Be prepared to back up all data before you convert.

You can extend or span any simple volume on a dynamic disk, not just the “one on the end” in the Disk Management console. You simply select the volume to expand and the total volume increase you want. Figure 12-48 shows a simple 488.28-GB volume named Extended that has been enlarged an extra 1316.40 GB in a portion of the hard drive, skipping the 195.31-GB section of unallocated space contiguous to it. This created an 1804.68-GB volume. Windows has no problem skipping areas on a drive.

Figure 12-48 Extended volume

NOTE You can extend and shrink volumes in Vista and 7 without using dynamic disks. You can shrink any volume with available free space (though you can’t shrink the volume by the whole amount of free space, based on the location of unmovable sectors such as the MBR), and you can expand volumes with unallocated space on the drive.

NOTE You can extend and shrink volumes in Vista and 7 without using dynamic disks. You can shrink any volume with available free space (though you can’t shrink the volume by the whole amount of free space, based on the location of unmovable sectors such as the MBR), and you can expand volumes with unallocated space on the drive.

To shrink a volume, right-click it and select Shrink Volume. Disk Management will calculate how much you can shrink it, and then you can choose up to that amount. To extend, right-click and select Extend Volume. It’s a pretty straightforward process.

Striped Volumes If you have two or more dynamic disks in a PC, Disk Management enables you to combine them into a striped volume. Although Disk Management doesn’t use the term, you know this as a RAID 0 array. A striped volume spreads out blocks of each file across multiple disks. Using two or more drives in a group called a stripe set, striping writes data first to a certain number of clusters on one drive, then to a certain number of clusters on the next drive, and so on. It speeds up data throughput because the system has to wait a much shorter time for a drive to read or write data. The drawback of striping is that if any single drive in the stripe set fails, all the data in the stripe set is lost.

To create a striped volume, right-click any unused space on a drive, choose New Volume, and then choose Striped. The wizard asks for the other drive you want to add to the stripe, and you need to select unallocated space on another dynamic disk. Select another unallocated space and go through the remaining screens on sizing and formatting until you’ve created a new striped volume (see Figure 12-49). The two stripes in Figure 12-49 appear to have different sizes, but if you look closely you’ll see they are both 1000 GB. All stripes must be the same size on each drive.

Figure 12-49 Two striped drives

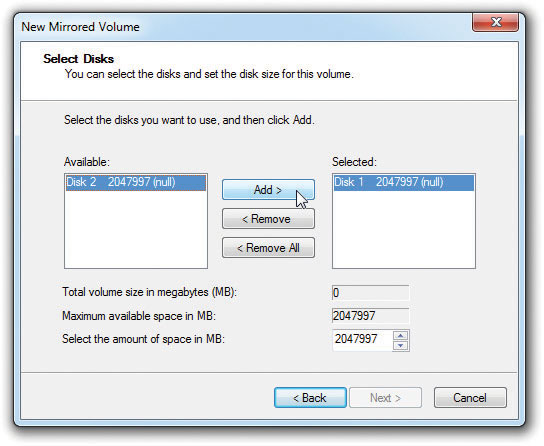

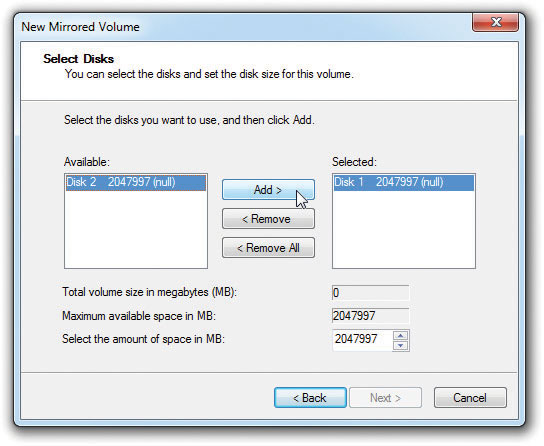

Mirrored Volumes Windows 7 Professional, Enterprise, and Ultimate editions can create a mirror set with two drives for data redundancy. You know mirrors from Chapter 11 as RAID 1. To create a mirror, right-click on unallocated space on a drive and select New Mirrored Volume (see Figure 12-50). This runs the New Mirrored Volume Wizard. Click Next to continue. Select an available disk in the Available box and click the Add button to move it to the Selected box (see Figure 12-51). Click Next to get to the by-now-familiar Assign Drive Letter or Path dialog box and select what is appropriate for the PC.

Figure 12-50 Selecting a new mirror

Figure 12-51 Selecting drives for the array

Other Levels of RAID Disk Management enables you to create a RAID 5 array that uses three or more disks to create a robust solution for storage. This applies to all the professional versions of Windows XP, Windows Vista, and Windows 7. Unfortunately for users of those operating systems, you can only make the array on a Windows Server machine that you access remotely across a network.

Disk Management cannot do any nested RAID arrays. So if you want RAID 0+1 or RAID 1+0 (RAID 10), you need to use third-party software (or go with hardware RAID).

Mounting Partitions as Folders

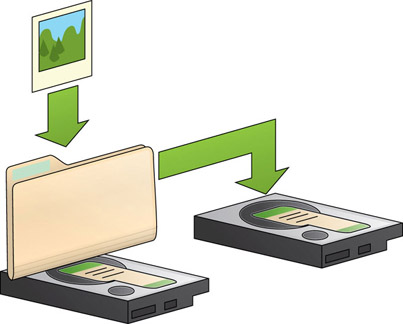

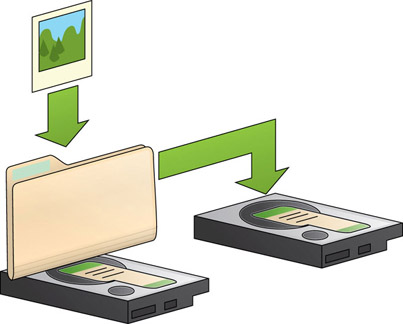

While partitions and volumes can be assigned a drive letter, D: through Z:, they can also be mounted as a folder on another drive, also known as a mount point. This enables you to use your existing folders to store more data than can fit on a single drive or partition/volume (see Figure 12-52).

Figure 12-52 Mounting a drive as a folder

Imagine you use your My Documents folder on a Windows XP machine to store your digital photos. As your collection grows, you realize your current 500-GB hard drive is running out of space. You’re willing to buy another hard drive, but you have a great organizational structure in your existing My Documents folder and you don’t want to lose that. You don’t have to move everything to the new hard drive, either.

After you install the new hard drive, you can mount the primary partition (or logical drive) as a folder within the existing My Documents folder on your C: drive (for example, C:\Users\Mike\My Photos). At this point the drive doesn’t have a letter (though you could add one later, if you wanted). To use the new drive, just drop your files into the My Photos folder. They’ll be stored on the second hard drive, not the original 500-GB drive (see Figure 12-53). Amazing!

Figure 12-53 Adding photos to the mounted folder stores them on the second hard drive.

NOTE Mounting a partition or volume as a folder in the scenario here only applies to Windows XP and Windows Vista. Although you can certainly mount them as folders in Windows 7, the use of Libraries makes them irrelevant. You would simply add a drive, give it a letter, and add a folder to the drive. Then add that folder to the appropriate Library and it will appear to be just like any other folder.

NOTE Mounting a partition or volume as a folder in the scenario here only applies to Windows XP and Windows Vista. Although you can certainly mount them as folders in Windows 7, the use of Libraries makes them irrelevant. You would simply add a drive, give it a letter, and add a folder to the drive. Then add that folder to the appropriate Library and it will appear to be just like any other folder.

To create a mount point, right-click an unallocated section of a disk and choose New Partition or New Simple Volume. This opens the appropriately named wizard. In the second screen, you can select a mount point rather than a drive letter (see Figure 12-54). Browse to a blank folder on an NTFS-formatted drive or create a new folder and you’re in business.

Figure 12-54 Choosing to create a mounted volume

EXAM TIP The CompTIA A+ 802 exam objectives mention “splitting” partitions. To be clear, you never actually split a partition. If you want to turn one partition into two, you need to remove the existing partition and create two new ones, or shrink the existing partition and add a new one to the unallocated space. If you see it on the exam, know that this is what CompTIA means.

EXAM TIP The CompTIA A+ 802 exam objectives mention “splitting” partitions. To be clear, you never actually split a partition. If you want to turn one partition into two, you need to remove the existing partition and create two new ones, or shrink the existing partition and add a new one to the unallocated space. If you see it on the exam, know that this is what CompTIA means.

Formatting a Partition

You can format any Windows partition/volume in My Computer/Computer. Just right-click the drive name and choose Format (see Figure 12-55). You’ll see a dialog box that asks for the type of file system you want to use, the cluster size, a place to put a volume label, and two other options. The Quick Format option tells Windows not to test the clusters and is a handy option when you’re in a hurry—and feeling lucky. The Enable Compression option tells Windows to give users the capability to compress folders or files. It works well but slows down your hard drive.

Figure 12-55 Choosing Format in Computer

Disk Management is today’s preferred formatting tool for Windows. When you create a new partition or volume, the wizard also asks you what type of format you want to use. Always use NTFS unless you’re that rare and strange person who wants to dual-boot some ancient version of Windows.

All OS installation discs partition and format as part of the OS installation. Windows simply prompts you to partition and then format the drive. Read the screens and you’ll do great.

Maintaining and Troubleshooting Hard Drives

Hard drives are complex mechanical and electrical devices. With platters spinning at thousands of rotations per minute, they also generate heat and vibration. All of these factors make hard drives susceptible to failure. In this section, you will learn some basic maintenance tasks that will keep your hard drives healthy, and for those inevitable instances when a hard drive fails, you will also learn what you can do to repair them.

Maintenance

Hard drive maintenance can be broken down into two distinct functions: checking the disk occasionally for failed clusters, and keeping data organized on the drive so it can be accessed quickly.

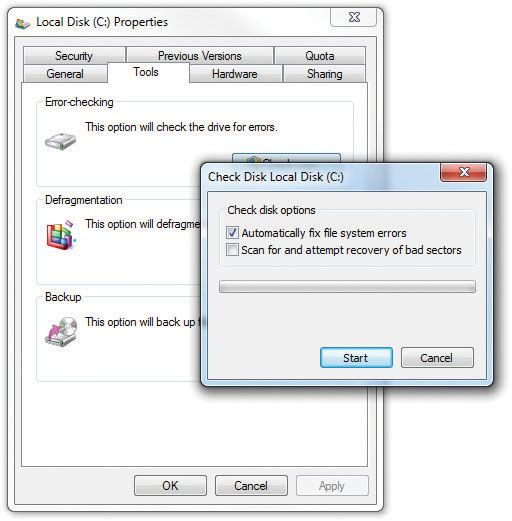

Error-Checking

Individual clusters on hard drives sometimes go bad. There’s nothing you can do to prevent this from happening, so it’s important that you check occasionally for bad clusters on drives. The tools used to perform this checking are generically called error-checking utilities, although the terms for two older Microsoft tools—ScanDisk and chkdsk (pronounced “checkdisk”)—are often used. Microsoft calls the tool Error-checking in Windows XP/Vista/7. Whatever the name of the utility, each does the same job: when the tool finds bad clusters, it puts the electronic equivalent of orange cones around them so the system won’t try to place data in those bad clusters.

EXAM TIP CompTIA A+ uses the terms CHKDSK and check disk rather than Error-checking.

EXAM TIP CompTIA A+ uses the terms CHKDSK and check disk rather than Error-checking.

Most error-checking tools do far more than just check for bad clusters. They go through all of the drive’s filenames, looking for invalid names and attempting to fix them. They look for clusters that have no filenames associated with them (we call these lost chains) and erase them. From time to time, the underlying links between parent and child folders are lost, so a good error-checking tool checks every parent and child folder. With a folder such as C:\Test\Data, for example, they make sure that the Data folder is properly associated with its parent folder, C:\Test, and that C:\Test is properly associated with its child folder, C:\Test\Data.

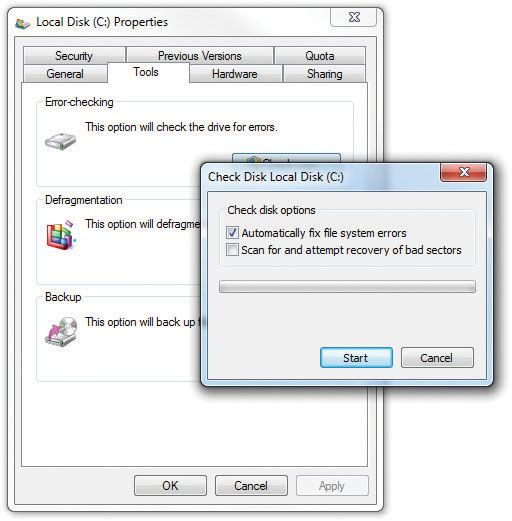

To access Error-checking on a Windows system, open My Computer/Computer, right-click the drive you want to check, and choose Properties to open the drive’s Properties dialog box. Select the Tools tab and click the Check now button (see Figure 12-56) to display the Check Disk dialog box, which has two options (see Figure 12-57). Check the box next to Automatically fix file system errors, but save the option to Scan for and attempt recovery of bad sectors for times when you actually suspect a problem, because it takes a while on bigger hard drives.

Figure 12-56 The Tools tab in the Properties dialog box

Figure 12-57 Check Disk options

Now that you know how to run Error-checking, your next question should be, “How often do I run it?” A reasonable maintenance plan would include running it about once a week. Error-checking is fast (unless you use the Scan for and attempt recovery option), and it’s a great tool for keeping your system in top shape.

Defragmentation

Fragmentation of clusters can increase your drive access times dramatically. It’s a good idea to defragment—or defrag—your drives as part of monthly maintenance. You access the defrag tool Disk Defragmenter the same way you access Error-checking—right-click a drive in My Computer/Computer and choose Properties—except you click the Defragment now button on the Tools tab to open Disk Defragmenter. In Windows Vista/7, Microsoft has given Disk Defragmenter a big visual makeover (see Figure 12-58), but both the old and new versions do the same job.

Figure 12-58 Disk Defragmenter in Windows 7 (left) and Windows XP

Defragmentation is interesting to watch—once. From then on, schedule Disk Defragmenter to run late at night. You should defragment your drives about once a month, although you could run Disk Defragmenter every week, and if you run it every night, it takes only a few minutes. The longer you go between defrags, the longer it takes. If you have Windows 7, Microsoft has made defragging even easier by automatically defragging disks once a week. You can adjust the schedule or even turn it off altogether, but remember that if you don’t run Disk Defragmenter, your system will run slower. If you don’t run Error-checking, you may lose data.

NOTE If you happen to have one of those blazingly fast solid-state drives (SSDs), you don’t have to defrag your drive. In fact, you should never defrag an SSD because it can shorten its lifetime. Windows 7 is even smart enough to disable scheduled defrag for SSDs.

NOTE If you happen to have one of those blazingly fast solid-state drives (SSDs), you don’t have to defrag your drive. In fact, you should never defrag an SSD because it can shorten its lifetime. Windows 7 is even smart enough to disable scheduled defrag for SSDs.

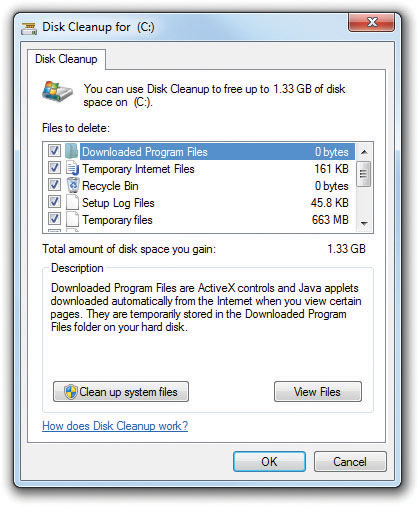

Disk Cleanup

Did you know that the average hard drive is full of trash? Not the junk you intentionally put in your hard drive such as the 23,000 e-mail messages that you refuse to delete from your e-mail program. This kind of trash is all of the files that you never see that Windows keeps for you. Here are a few examples:

• Files in the Recycle Bin When you delete a file, it isn’t really deleted. It’s placed in the Recycle Bin in case you decide you need the file later. I just checked my Recycle Bin and found around 3 GB worth of files (see Figure 12-59). That’s a lot of trash!

• Temporary Internet files When you go to a Web site, Windows keeps copies of the graphics and other items so the page will load more quickly the next time you access it. You can see these files by opening the Internet Options applet on the Control Panel. Click the Settings button under the Browsing history label and then click the View files button on the Temporary Internet Files and History Settings dialog box. Figure 12-60 shows temporary Internet files from Internet Explorer.

• Downloaded program files Your system always keeps a copy of any Java or ActiveX applets it downloads. You can see these in the Internet Options applet by clicking the Settings button under the Browsing history label. Click the View objects button on the Temporary Internet Files and History Settings dialog box. You’ll generally find only a few tiny files here.

• Temporary files Many applications create temporary files that are supposed to be deleted when the application is closed. For one reason or another, these temporary files sometimes aren’t deleted. The location of these files varies with the version of Windows, but they always reside in a folder called “Temp.”

Figure 12-59 Mike’s Recycle Bin

Figure 12-60 Lots of temporary Internet files

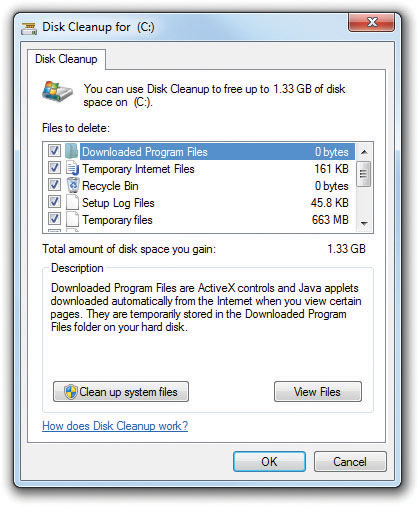

Every hard drive eventually becomes filled with lots of unnecessary trash. All versions of Windows tend to act erratically when the drives run out of unused space. Fortunately, all versions of Windows have a powerful tool called Disk Cleanup (see Figure 12-61). You can access Disk Cleanup in all versions of Windows by choosing Start | All Programs | Accessories | System Tools | Disk Cleanup.

Figure 12-61 Disk Cleanup

Disk Cleanup gets rid of the four types of files just described (and a few others). Run Disk Cleanup once a month or so to keep plenty of space available on your hard drive.

Troubleshooting Hard Drive Implementation

There’s no scarier computer problem than an error that points to trouble with a hard drive. This section looks at some of the more common problems that occur with hard drives and how to fix them. These issues fall into four broad categories: installation errors, data corruption, dying hard drives, and RAID issues.

Installation Errors

Installing a drive and getting to the point where it can hold data requires four distinct steps: connectivity, CMOS, partitioning, and formatting. If you make a mistake at any point on any of these steps, the drive won’t work. The beauty of this is that if you make an error, you can walk back through each step and check for problems. The “Troubleshooting Hard Drive Installation” section in Chapter 11 covered physical connections and CMOS, so this section concentrates on the latter two issues.

Partitioning Partitioning errors generally fall into two groups: failing to partition at all and making the wrong size or type of partition. You’ll recognize the former type of error the first time you open My Computer/Computer after installing a drive. If you forgot to partition it, the drive won’t even show up in My Computer/Computer, only in Disk Management. If you made the partition too small, that’ll become painfully obvious when you start filling it up with files.

The fix for partitioning errors is simply to open Disk Management and do the partitioning correctly. If you’ve added files to the wrongly sized drive, don’t forget to back them up before you repartition in Windows XP. Just right-click and select Extend Volume in Windows Vista/7 to correct the mistake.

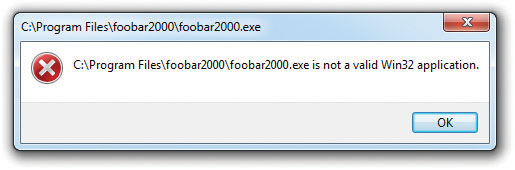

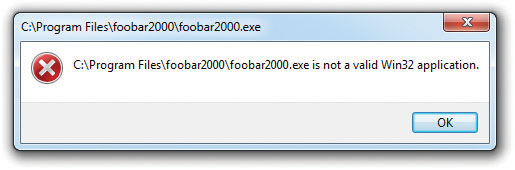

Formatting Failing to format a drive makes the drive unable to hold data. Accessing the drive in Windows results in a drive “is not accessible” error, and from a C:\ prompt, you’ll get the famous “Invalid media” type error. Format the drive unless you’re certain that the drive has a format already. Corrupted files can create the invalid media error. Check the upcoming “Data Corruption” section for the fix.

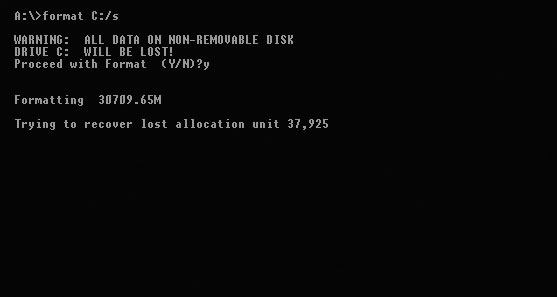

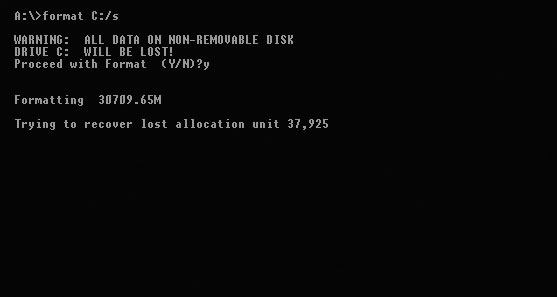

Most of the time, formatting is a slow, boring process. But sometimes the drive makes “bad sounds” and you start seeing errors like the one shown in Figure 12-62 at the top of the screen.

Figure 12-62 The “Trying to recover lost allocation unit” error

An allocation unit is another term for a cluster. The drive has run across a bad cluster and is trying to fix it. For years, I’ve told techs that seeing this error a few (610) times doesn’t mean anything; every drive comes with a few bad spots. This is no longer true. Modern drives actually hide a significant number of extra sectors that they use to replace bad sectors automatically. If a new drive gets a lot of “Trying to recover lost allocation unit” errors, you can bet that the drive is dying and needs to be replaced. Get the hard drive maker’s diagnostic tool to be sure. Bad clusters are reported by S.M.A.R.T.