CHAPTER 7

RAM

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Identify the different types of DRAM packaging

• Explain the varieties of RAM

• Select and install RAM

• Perform basic RAM troubleshooting

Whenever people come up to me and start professing their computer savvy, I ask them a few questions to see how much they really know. In case you and I ever meet and you decide you want to “talk tech” with me, I’ll tell you my first two questions now so you’ll be ready. Both involve random access memory (RAM), the working memory for the CPU.

1. “How much RAM is in your computer?”

2. “What is RAM and why is it so important that every PC has some?”

Can you answer either of these questions? Don’t fret if you can’t—you’ll know how to answer both of them before you finish this chapter. Let’s start by reviewing what you know about RAM thus far.

TIP The CompTIA A+ certification domains use the term memory to describe the short-term storage used by the PC to load the operating system and running applications. The more common term in the industry is RAM, for random access memory, the kind of short-term memory you’ll find in every computer. More specifically, the primary system RAM is dynamic random access memory (DRAM). For the most part, this book uses the terms RAM and DRAM.

TIP The CompTIA A+ certification domains use the term memory to describe the short-term storage used by the PC to load the operating system and running applications. The more common term in the industry is RAM, for random access memory, the kind of short-term memory you’ll find in every computer. More specifically, the primary system RAM is dynamic random access memory (DRAM). For the most part, this book uses the terms RAM and DRAM.

When not in use, programs and data are held in a mass storage device such as a hard drive, USB thumb drive, optical drive, or some other device that can hold data while the computer is off. When you load a program in Windows, your PC copies the program from the mass storage device to RAM and then runs it (see Figure 7-1).

Figure 7-1 Mass storage holds programs, but programs need to run in RAM.

You saw in Chapter 6 that the CPU uses dynamic random access memory (DRAM) as RAM for all PCs. Just like CPUs, DRAM has gone through a number of evolutionary changes over the years, resulting in improved DRAM technologies such as SDRAM, RDRAM, and DDR RAM. This chapter starts by explaining how DRAM works, and then discusses the types of DRAM used over the past several years and how they improve on the original DRAM. The third section, “Working with RAM,” goes into the details of finding and installing RAM. The chapter finishes with troubleshooting RAM problems.

Historical/Conceptual

Understanding DRAM

As discussed in Chapter 6, DRAM functions like an electronic spreadsheet, with numbered rows containing cells and each cell holding a one or a zero. Now let’s look at what’s physically happening. Each spreadsheet cell is a special type of semiconductor that can hold a single bit—one or zero—by using microscopic capacitors and transistors. DRAM makers put these semiconductors into chips that can hold a certain number of bits. The bits inside the chips are organized in a rectangular fashion, using rows and columns.

Each chip has a limit on the number of lines of code it can contain. Think of each line of code as one of the rows on the electronic spreadsheet; one chip might be able to store a million rows of code while another chip might be able to store over a billion lines. Each chip also has a limit on the width of the lines of code it can handle. One chip might handle 8-bit-wide data while another might handle 16-bit-wide data. Techs describe chips by bits rather than bytes, so they refer to x8 and x16, respectively. Just as you could describe a spreadsheet by the number of rows and columns—John’s accounting spreadsheet is huge, 48 rows × 12 columns—memory makers describe RAM chips the same way. An individual DRAM chip that holds 1,048,576 rows and 8 columns, for example, would be a 1Mx8 chip, with “M” as shorthand for “mega,” just like in megabytes (220 bytes). It is difficult if not impossible to tell the size of a DRAM chip just by looking at it—only the DRAM makers know the meaning of the tiny numbers on the chips (see Figure 7-2), although sometimes you can make a good guess.

Figure 7-2 What do these numbers mean?

Organizing DRAM

Because of its low cost, high speed, and capability to contain a lot of data in a relatively small package, DRAM has been the standard RAM used in all computers—not just PCs—since the mid-1970s. DRAM can be found in just about everything, from automobiles to automatic bread makers.

The PC has very specific requirements for DRAM. The original 8088 processor had an 8-bit frontside bus. Commands given to an 8088 processor were in discrete 8-bit chunks. You needed RAM that could store data in 8-bit (1-byte) chunks, so that each time the CPU asked for a line of code, the memory controller chip (MCC) could put an 8-bit chunk on the data bus. This optimized the flow of data into (and out from) the CPU. Although today’s DRAM chips may have widths greater than 1 bit, all DRAM chips back then were 1 bit wide, meaning only sizes such as 64 K × 1 or 256 K × 1 existed—always 1 bit wide. So how was 1-bit-wide DRAM turned into 8-bit-wide memory? The solution was quite simple: just take eight 1-bit-wide chips and use the MCC to organize them electronically to be eight wide (see Figure 7-3).

Figure 7-3 The MCC accessing data on RAM soldered onto the motherboard

Practical DRAM

Okay, before you learn more about DRAM, I need to clarify a critical point. When you first saw the 8088’s machine language in Chapter 6, all the examples in the “codebook” were exactly 1-byte commands. Figure 7-4 shows the codebook again—see how all the commands are 1 byte?

Figure 7-4 Codebook again

Well, the reality is slightly different. Most of the 8088 machine language commands are 1 byte, but more-complex commands need 2 bytes. For example, the following command tells the CPU to move 163 bytes “up the RAM spreadsheet” and run whatever command is there. Cool, eh?

1110100110100011

The problem here is that the command is 2 bytes wide, not 1 byte. So how did the 8088 handle this? Simple—it just took the command 1 byte at a time. It took twice as long to handle the command because the MCC had to go to RAM twice, but it worked.

So if some of the commands are more than 1 byte wide, why didn’t Intel make the 8088 with a 16-bit frontside bus? Wouldn’t that have been better? Well, Intel did. Intel invented a CPU called the 8086. The 8086 actually predates the 8088 and was absolutely identical to the 8088 except for one small detail: it had a 16-bit frontside bus. IBM could have used the 8086 instead of the 8088 and used 2-byte-wide RAM instead of 1-byte-wide RAM. Of course, they would have needed to invent an MMC that handled that kind of RAM (see Figure 7-5).

Figure 7-5 Pumped-up 8086 MCC at work

Why didn’t Intel sell IBM the 8086 instead of the 8088? There were two reasons. First, nobody had invented an affordable MCC or RAM that handled 2 bytes at a time. Sure, chips had been invented, but they were expensive and IBM didn’t think anyone would want to pay $12,000 for a personal computer. So IBM bought the Intel 8088, not the Intel 8086, and all our RAM came in bytes. But as you might imagine, it didn’t stay that way for long.

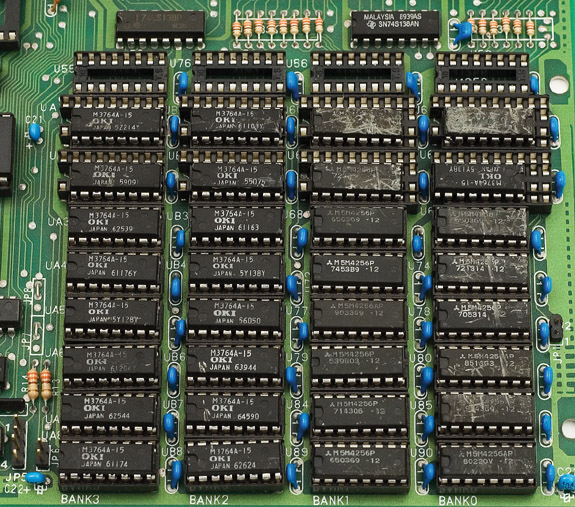

DRAM Sticks

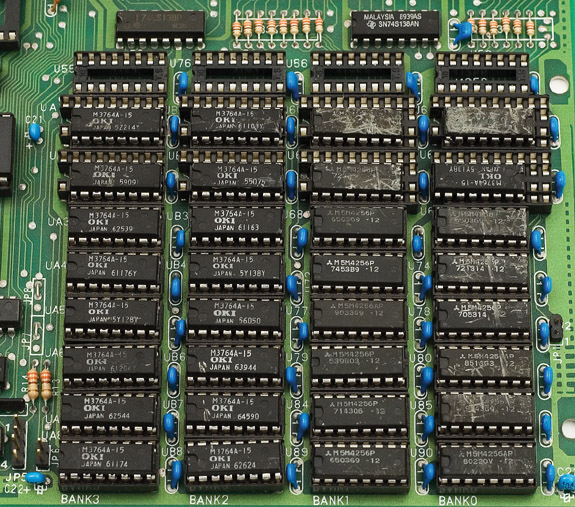

As CPU data bus sizes increased, so too did the need for RAM wide enough to fill the bus. The Intel 80386 CPU, for example, had a 32-bit data bus and thus the need for 32-bit-wide DRAM. Imagine having to line up 32 one-bit-wide DRAM chips on a motherboard. Talk about a waste of space! Figure 7-6 shows motherboard RAM run amuck.

Figure 7-6 That’s a lot of real estate used by RAM chips!

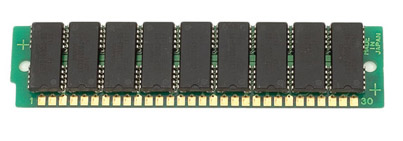

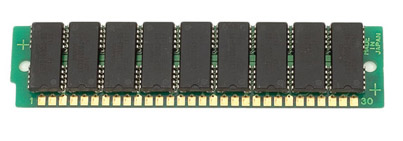

DRAM manufacturers responded by creating wider DRAM chips, such as x4, x8, and x16, and putting multiples of them on a small circuit board called a stick or module. Figure 7-7 shows an early stick, called a single inline memory module (SIMM), with eight DRAM chips. To add RAM to a modern machine, you need to get the right stick or sticks for the particular motherboard. Your motherboard manual tells you precisely what sort of module you need and how much RAM you can install.

Figure 7-7 A 72-pin SIMM

Modern CPUs are a lot smarter than the old Intel 8088. Their machine languages have some commands that are up to 64 bits (8 bytes) wide. They also have at least a 64-bit frontside bus that can handle more than just 8 bits. They don’t want RAM to give them a puny 8 bits at a time! To optimize the flow of data into and out of the CPU, the modern MCC provides at least 64 bits of data every time the CPU requests information from RAM.

NOTE Some MCCs are 128 bits wide.

NOTE Some MCCs are 128 bits wide.

Modern DRAM sticks come in 32-bit- and 64-bit-wide form factors with a varying number of chips. Many techs describe these memory modules by their width, so we call them x32 and x64. Note that this number does not describe the width of the individual DRAM chips on the module. When you read or hear about by whatever memory, you need to know whether that person is talking about the DRAM width or the module width. When the CPU needs certain bytes of data, it requests those bytes via the address bus. The CPU does not know the physical location of the RAM that stores that data, nor the physical makeup of the RAM—such as how many DRAM chips work together to provide the 64-bit-wide memory rows. The MCC keeps track of this and just gives the CPU whichever bytes it requests (see Figure 7-8).

Figure 7-8 The MCC knows the real location of the DRAM.

Consumer RAM

If modern DRAM modules come in sizes much wider than a byte, why do people still use the word “byte” to describe how much DRAM they have? Convention. Habit. Rather than using a label that describes the electronic structure of RAM, common usage describes the total capacity of RAM on a stick in bytes. John has a single 2-GB stick of RAM on his motherboard, for example, and Sally has two 1-GB sticks. Both systems have a total of 2 GB of system RAM. That’s what your clients care about. Having enough RAM makes their systems snappy and stable; not enough RAM means their systems run poorly. As a tech, you need to know more, of course, to pick the right RAM for many different types of computers.

801

Types of RAM

Development of newer, wider, and faster CPUs and MCCs motivate DRAM manufacturers to invent new DRAM technologies that deliver enough data at a single pop to optimize the flow of data into and out of the CPU.

SDRAM

Most modern systems use some form of synchronous DRAM (SDRAM). SDRAM is still DRAM, but it is synchronous—tied to the system clock, just like the CPU and MCC, so the MCC knows when data is ready to be grabbed from SDRAM. This results in little wasted time.

SDRAM made its debut in 1996 on a stick called a dual inline memory module (DIMM). The early SDRAM DIMMs came in a wide variety of pin sizes. The most common pin sizes found on desktops were the 168-pin variety. Laptop DIMMs came in 68-pin, 144-pin (see Figure 7-9), or 172-pin micro-DIMM packages; and the 72-pin, 144-pin, or 200-pin small-outline DIMM (SO-DIMM) form factors (see Figure 7-10). With the exception of the 32-bit 72-pin SO-DIMM, all these DIMM varieties delivered 64-bit-wide data to match the 64-bit data bus of every CPU since the Pentium.

Figure 7-9 144-pin micro-DIMM (photo courtesy of Micron Technology, Inc.)

Figure 7-10 A 168-pin DIMM above a 144-pin SO-DIMM

To take advantage of SDRAM, you needed a PC designed to use SDRAM. If you had a system with slots for 168-pin DIMMs, for example, your system used SDRAM. A DIMM in any one of the DIMM slots could fill the 64-bit bus, so each slot was called a bank. You could install one, two, or more sticks and the system would work. Note that on laptops that used the 72-pin SO-DIMM, you needed to install two sticks of RAM to make a full bank, because each stick only provided half the bus width.

SDRAM was tied to the system clock, so its clock speed matched the frontside bus. Five clock speeds were commonly used on the early SDRAM systems: 66, 75, 83, 100, and 133 MHz. The RAM speed had to match or exceed the system speed or the computer would be unstable or wouldn’t work at all. These speeds were prefixed with a “PC” in the front, based on a standard forwarded by Intel, so SDRAM speeds were PC66 through PC133. For a Pentium III computer with a 100-MHz frontside bus, you needed to buy SDRAM DIMMs rated to handle it, such as PC100 or PC133.

RDRAM

When Intel was developing the Pentium 4, they knew that regular SDRAM just wasn’t going to be fast enough to handle the quad-pumped 400-MHz frontside bus. Intel announced plans to replace SDRAM with a very fast, new type of RAM developed by Rambus, Inc., called Rambus DRAM, or simply RDRAM (see Figure 7-11). Hailed by Intel as the next great leap in DRAM technology, RDRAM could handle speeds up to 800 MHz, which gave Intel plenty of room to improve the Pentium 4.

Figure 7-11 RDRAM

RDRAM was greatly anticipated by the industry for years, but industry support for RDRAM proved less than enthusiastic due to significant delays in development and a price many times that of SDRAM. Despite this grudging support, almost all major PC makers sold systems that used RDRAM—for a while. From a tech’s standpoint, RDRAM shares almost all of the characteristics of SDRAM. A stick of RDRAM is called a RIMM. In this case, however, the letters don’t actually stand for anything; they just rhyme: SIMMs, DIMMs, and now RIMMs, get it?

NOTE The 400-MHz frontside bus speed wasn’t achieved by making the system clock faster—it was done by making CPUs and MCCs capable of sending 64 bits of data two or four times for every clock cycle, effectively doubling or quadrupling the system bus speed.

NOTE The 400-MHz frontside bus speed wasn’t achieved by making the system clock faster—it was done by making CPUs and MCCs capable of sending 64 bits of data two or four times for every clock cycle, effectively doubling or quadrupling the system bus speed.

RIMMs came in two sizes: a 184-pin for desktops and a 160-pin SO-RIMM for laptops. RIMMs were keyed differently from DIMMs to ensure that even though they are the same basic size, you couldn’t accidentally install a RIMM in a DIMM slot or vice versa. RDRAM also had a speed rating: 600 MHz, 700 MHz, 800 MHz, or 1066 MHz. RDRAM employed an interesting dual-channel architecture. Each RIMM was 64 bits wide, but the Rambus MCC alternated between two sticks to increase the speed of data retrieval. You were required to install RIMMs in pairs to use this dual-channel architecture.

RDRAM motherboards also required that all RIMM slots be populated. Unused pairs of slots needed a passive device called a continuity RIMM (CRIMM) installed in each slot to enable the RDRAM system to terminate properly. Figure 7-12 shows a CRIMM.

Figure 7-12 CRIMM

RDRAM offered dramatic possibilities for high-speed PCs but ran into three roadblocks that Betamaxed it. First, the technology was owned wholly by Rambus; if you wanted to make it, you had to pay the licensing fees they charged. That led directly to the second problem, expense. RDRAM cost substantially more than SDRAM. Third, Rambus and Intel made a completely closed deal for the technology. RDRAM worked only on Pentium 4 systems using Intel-made MCCs. AMD was out of luck. Clearly, the rest of the industry had to look for another high-speed RAM solution.

TIP On the CompTIA A+ exams, you’ll see RDRAM referred to as RAMBUS RAM. Don’t get thrown by the odd usage.

TIP On the CompTIA A+ exams, you’ll see RDRAM referred to as RAMBUS RAM. Don’t get thrown by the odd usage.

NOTE “Betamaxed” is slang for “made it obsolete because no one bought it, even though it was a superior technology to the winner in the marketplace.” It refers to the VHS versus Betamax wars in the old days of video cassette recorders.

NOTE “Betamaxed” is slang for “made it obsolete because no one bought it, even though it was a superior technology to the winner in the marketplace.” It refers to the VHS versus Betamax wars in the old days of video cassette recorders.

DDR SDRAM

AMD and many major system and memory makers threw their support behind double data rate SDRAM (DDR SDRAM). DDR SDRAM basically copied Rambus, doubling the throughput of SDRAM by making two processes for every clock cycle. This synchronized (pardon the pun) nicely with the Athlon and later AMD processors’ double-pumped frontside bus. DDR SDRAM could not run as fast as RDRAM—although relatively low frontside bus speeds made that a moot point—but cost only slightly more than regular SDRAM.

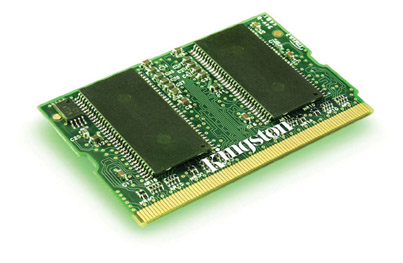

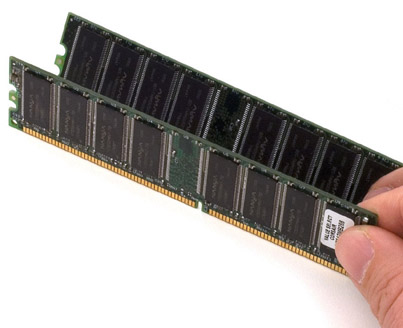

DDR SDRAM for desktops comes in 184-pin DIMMs. These DIMMs match 168-pin DIMMs in physical size but not in pin compatibility (see Figure 7-13). The slots for the two types of RAM appear similar as well but have different guide notches, so you can’t insert either type of RAM into the other’s slot. DDR SDRAM for laptops comes in either 200-pin SO-DIMMs or 172-pin micro-DIMMs (see Figure 7-14).

Figure 7-13 DDR SDRAM

Figure 7-14 172-pin DDR SDRAM micro-DIMM (photo courtesy of Kingston/Joint Harvest)

NOTE Most techs drop some or all of the SDRAM part of DDR SDRAM when engaged in normal geekspeak. You’ll hear the memory referred to as DDR, DDR RAM, and the weird hybrid, DDRAM. RAM makers use the term single data rate SDRAM (SDR SDRAM) for the original SDRAM to differentiate it from DDR SDRAM.

NOTE Most techs drop some or all of the SDRAM part of DDR SDRAM when engaged in normal geekspeak. You’ll hear the memory referred to as DDR, DDR RAM, and the weird hybrid, DDRAM. RAM makers use the term single data rate SDRAM (SDR SDRAM) for the original SDRAM to differentiate it from DDR SDRAM.

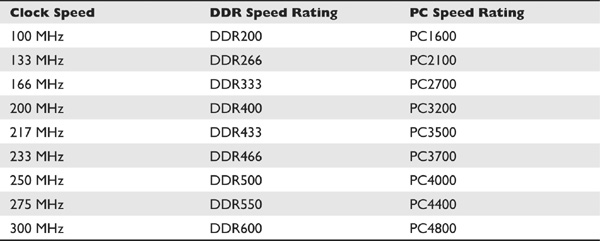

DDR sticks use a rather interesting naming convention—actually started by the Rambus folks—based on the number of bytes per second of data throughput the RAM can handle. To determine the bytes per second, take the MHz speed and multiply by 8 bytes (the width of all DDR SDRAM sticks). So 400 MHz multiplied by 8 is 3200 megabytes per second (MBps). Put the abbreviation “PC” in the front to make the new term: PC3200. Many techs also use the naming convention used for the individual DDR chips; for example, DDR400 refers to a 400-MHz DDR SDRAM chip running on a 200-MHz clock.

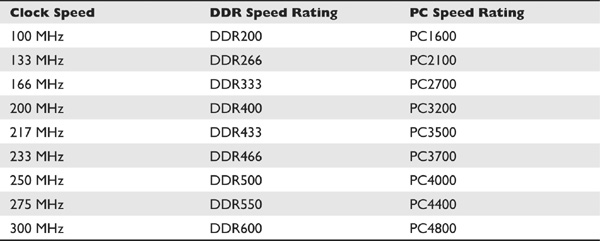

Even though the term DDRxxx is really just for individual DDR chips and the term PCxxxx is for DDR sticks, this tradition of two names for every speed of RAM is a bit of a challenge because you’ll often hear both terms used interchangeably. Table 7-1 shows all the speeds for DDR—not all of these are commonly used.

Table 7-1 DDR Speeds

Following the lead of AMD, VIA, and other manufacturers, the PC industry adopted DDR SDRAM as the standard system RAM. In the summer of 2003, Intel relented and stopped producing motherboards and memory controllers that required RDRAM.

One thing is sure about PC technologies: any good idea that can be copied will be copied. One of Rambus’ best concepts was the dual-channel architecture—using two sticks of RDRAM together to increase throughput. Manufacturers have released motherboards with MCCs that support dual-channel architecture using DDR SDRAM. Dual-channel DDR motherboards use regular DDR sticks, although manufacturers often sell RAM in matched pairs, branding them as dual-channel RAM.

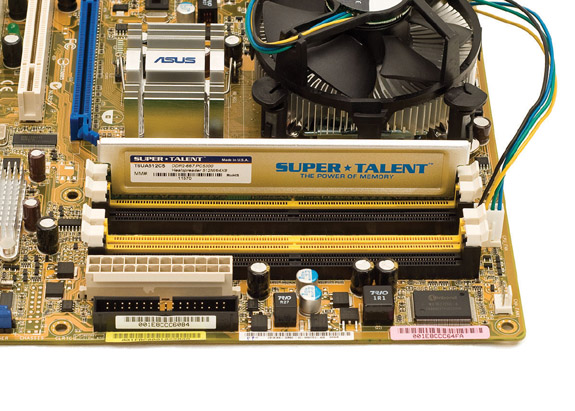

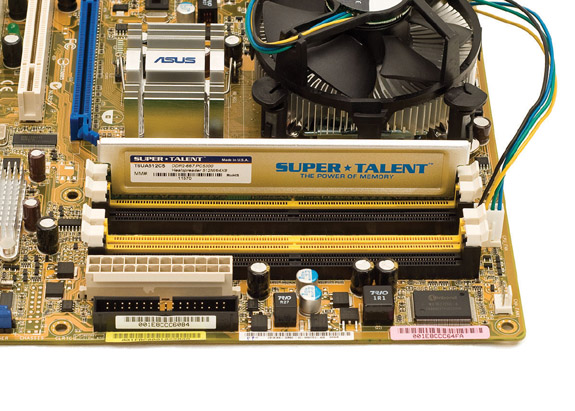

Dual-channel DDR works like RDRAM in that you must have two identical sticks of DDR and they must snap into two paired slots. Unlike RDRAM, dual-channel DDR doesn’t have anything like CRIMMs—you don’t need to put anything into unused slot pairs. Dual-channel DDR technology is very flexible but also has a few quirks that vary with each system. Some motherboards have three DDR SDRAM slots, but the dual-channel DDR works only if you install DDR SDRAM in two of the slots. Other boards have four slots and require that you install matching pairs in the same-colored slots to run in dual-channel mode (see Figure 7-15). If you populate a third slot, the system uses the full capacity of RAM installed but turns off the dual-channel feature.

Figure 7-15 A motherboard showing the four RAM slots. By populating the same-colored slots with identical RAM, you can run in dual-channel mode.

DDR2

The fastest versions of DDR RAM run at a blistering PC4800. That’s 4.8 gigabytes per second (GBps) of data throughput! You’d think that kind of speed would satisfy most users, and to be honest, DRAM running at approximately 5 GBps really is plenty fast—for yesterday. However, the ongoing speed increases ensure that even these speeds won’t be good enough in the future. Knowing this, the RAM industry came out with DDR2, the successor to DDR. DDR2 is DDR RAM with some improvements in its electrical characteristics, enabling it to run even faster than DDR while using less power. The big speed increase from DDR2 comes by clock doubling the input/output circuits on the chips. This does not speed up the core RAM—the part that holds the data—but speeding up the input/output and adding special buffers (sort of like a cache) makes DDR2 run much faster than regular DDR. DDR2 uses a 240-pin DIMM that’s not compatible with DDR (see Figure 7-16). Likewise, the DDR2 200-pin SO-DIMM is incompatible with the DDR SO-DIMM. You’ll find motherboards running both single-channel and dual-channel DDR2.

Figure 7-16 240-pin DDR2 DIMM

TIP DDR2 RAM sticks will not fit into DDR sockets, nor are they electronically compatible.

TIP DDR2 RAM sticks will not fit into DDR sockets, nor are they electronically compatible.

Table 7-2 shows some of the common DDR2 speeds.

Table 7-2 DDR2 Speeds

DDR3

DDR3 boasts higher speeds, more efficient architecture, and around 30 percent lower power consumption than DDR2 RAM, making it a compelling choice for system builders. Just like its predecessor, DDR3 uses a 240-pin DIMM, albeit one that is slotted differently to make it difficult for users to install the wrong RAM in their system without using a hammer (see Figure 7-17). DDR3 SODIMMs for portable computers have 204 pins. Neither fits into a DDR2 socket.

Figure 7-17 DDR2 DIMM on top of a DDR3 DIMM

NOTE Do not confuse DDR3 with GDDR3; the latter is a type of memory used solely in video cards. See Chapter 21 for the scoop on video-specific types of memory.

NOTE Do not confuse DDR3 with GDDR3; the latter is a type of memory used solely in video cards. See Chapter 21 for the scoop on video-specific types of memory.

DDR3 doubles the buffer of DDR2 from 4 bits to 8 bits, giving it a huge boost in bandwidth over older RAM. Not only that, but some DDR3 modules also include a feature called XMP, or extended memory profile, that enables power users to overclock their RAM easily, boosting their already fast memory to speeds that would make Chuck Yeager nervous. DDR3 modules also use higher-density memory chips, which means we may eventually see 16-GB DDR3 modules.

Some chipsets that support DDR3 also support a feature called triple-channel memory, which works a lot like dual-channel before it, but with three sticks of RAM instead of two. Intel’s LGA 1366 platform supports triple-channel memory; no AMD processors support a triple-channel feature. You’ll need three of the same type of memory modules and a motherboard that supports it, but triple-channel memory can greatly increase performance for those who can afford it.

NOTE Quad-channel memory also exists, but as of 2012, you’ll only find it in servers.

NOTE Quad-channel memory also exists, but as of 2012, you’ll only find it in servers.

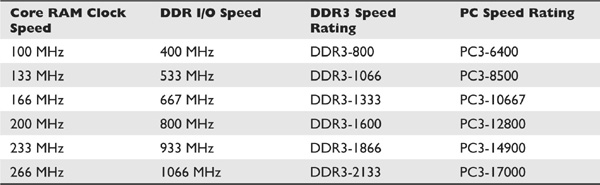

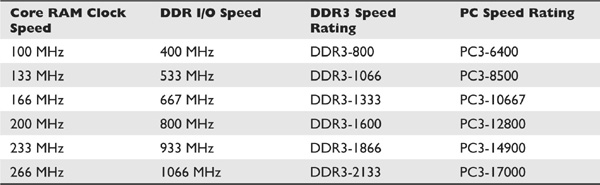

In keeping with established tradition, Table 7-3 is a chart of common DDR3 speeds. Note how DDR3 I/O speeds are quadruple the clock speeds, whereas DDR2 I/O speeds are only double the clock. This speed increase is due to the increased buffer size, which enables DDR3 to grab twice as much data every clock cycle as DDR2 can.

Table 7-3 DDR3 Speeds

RAM Variations

Within each class of RAM, you’ll find variations in packaging, speed, quality, and the capability to handle data with more or fewer errors. Higher-end systems often need higher-end RAM, so knowing these variations is of crucial importance to techs.

Double-Sided DIMMs

Every type of RAM stick, starting with the old FPM SIMMs and continuing through to 240-pin DDR3 SDRAM, comes in one of two types: single-sided RAM and double-sided RAM. As their name implies, single-sided sticks have chips on only one side of the stick. Double-sided sticks have chips on both sides (see Figure 7-18). The vast majority of RAM sticks are single-sided, but plenty of double-sided sticks are out there. Double-sided sticks are basically two sticks of RAM soldered onto one board. There’s nothing wrong with double-sided RAM sticks other than the fact that some motherboards either can’t use them or can only use them in certain ways—for example, only if you use a single stick and it goes into a certain slot.

Figure 7-18 Double-sided DDR SDRAM

Latency

If you’ve shopped for RAM lately, you may have noticed terms such as “CL2” or “low latency” as you tried to determine which RAM to purchase. You might find two otherwise identical RAM sticks with a 20 percent price difference and a salesperson pressuring you to buy the more expensive one because it’s “faster” even though both sticks say DDR 3200 (see Figure 7-19).

Figure 7-19 Why is one more expensive than the other?

RAM responds to electrical signals at varying rates. When the memory controller starts to grab a line of memory, for example, a slight delay occurs; think of it as the RAM getting off the couch. After the RAM sends out the requested line of memory, there’s another slight delay before the memory controller can ask for another line—the RAM sat back down. The delay in RAM’s response time is called its latency. RAM with a lower latency—such as CL2—is faster than RAM with a higher latency—such as CL3—because it responds more quickly. The CL refers to clock cycle delays. The 2 means that the memory delays two clock cycles before delivering the requested data; the 3 means a three-cycle delay.

NOTE CAS stands for column array strobe, one of the wires (along with the row array strobe) in the RAM that helps the memory controller find a particular bit of memory. Each of these wires requires electricity to charge up before it can do its job. This is one of the aspects of latency.

NOTE CAS stands for column array strobe, one of the wires (along with the row array strobe) in the RAM that helps the memory controller find a particular bit of memory. Each of these wires requires electricity to charge up before it can do its job. This is one of the aspects of latency.

Latency numbers reflect how many clicks of the system clock it takes before the RAM responds. If you speed up the system clock, say from 166 MHz to 200 MHz, the same stick of RAM might take an extra click before it can respond. When you take RAM out of an older system and put it into a newer one, you might get a seemingly dead PC, even though the RAM fits in the DIMM slot. Many motherboards enable you to adjust the RAM timings manually. If yours does so, try raising the latency to give the slower RAM time to respond. See Chapter 8 to learn how to make these adjustments (and how to recover if you make a mistake).

From a tech’s standpoint, you need to get the proper RAM for the system you’re working on. If you put a high-latency stick in a motherboard set up for a low-latency stick, you’ll get an unstable or completely dead PC. Check the motherboard manual and get the quickest RAM the motherboard can handle, and you should be fine.

Parity and ECC

Given the high speeds and phenomenal amount of data moved by the typical DRAM chip, a RAM chip might occasionally give bad data to the memory controller. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the RAM has gone bad. It could be a hiccup caused by some unknown event that makes a good DRAM chip say a bit is a zero when it’s really a one. In most cases you won’t even notice when such a rare event happens. In some environments, however, even these rare events are intolerable. A bank server handling thousands of online transactions per second, for example, can’t risk even the smallest error. These important computers need a more robust, fault-resistant RAM.

The first type of error-detecting RAM was known as parity RAM (see Figure 7-20). Parity RAM stored an extra bit of data (called the parity bit) that the MCC used to verify whether the data was correct. Parity wasn’t perfect. It wouldn’t always detect an error, and if the MCC did find an error, it couldn’t correct the error. For years, parity was the only available way to tell if the RAM made a mistake.

Figure 7-20 Ancient parity RAM stick

Today’s PCs that need to watch for RAM errors use a special type of RAM called error correction code RAM (ECC RAM). ECC is a major advance in error checking on DRAM. First, ECC detects any time a single bit is incorrect. Second, ECC fixes these errors on-the-fly. The checking and fixing come at a price, however, as ECC RAM is always slower than non-ECC RAM.

ECC DRAM comes in every DIMM package type and can lead to some odd-sounding numbers. You can find DDR2 or DDR3 RAM sticks, for example, that come in 240-pin, 72-bit versions. Similarly, you’ll see 200-pin, 72-bit SO-DIMM format. The extra 8 bits beyond the 64-bit data stream are for the ECC.

You might be tempted to say “Gee, maybe I want to try this ECC RAM.” Well, don’t! To take advantage of ECC RAM, you need a motherboard with an MCC designed to use ECC. Only expensive motherboards for high-end systems use ECC. The special-use-only nature of ECC makes it fairly rare. Plenty of techs with years of experience have never even seen ECC RAM.

NOTE Some memory manufacturers call the technology error checking and correction (ECC). Don’t be thrown off if you see the phrase—it’s the same thing, just a different marketing slant for error correction code.

NOTE Some memory manufacturers call the technology error checking and correction (ECC). Don’t be thrown off if you see the phrase—it’s the same thing, just a different marketing slant for error correction code.

Working with RAM

Whenever someone comes up to me and asks what single hardware upgrade they can do to improve their system performance, I always tell them the same thing—add more RAM. Adding more RAM can improve overall system performance, processing speed, and stability—if you get it right. Botching the job can cause dramatic system instability, such as frequent, random crashes and reboots. Every tech needs to know how to install and upgrade system RAM of all types.

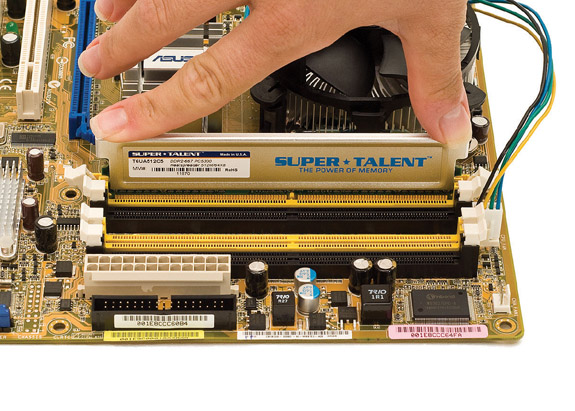

To get the desired results from a RAM upgrade, you must first determine if insufficient RAM is the cause of system problems. Second, you need to pick the proper RAM for the system. Finally, you must use good installation practices. Always store RAM sticks in anti-static packaging whenever they’re not in use, and use strict ESD handling procedures. Like many other pieces of the PC, RAM is very sensitive to ESD and other technician abuse (see Figure 7-21).

Figure 7-21 Don’t do this! Grabbing the contacts is a bad idea!

Do You Need More RAM?

Two symptoms point to the need for more RAM in a PC: general system sluggishness and excessive hard drive accessing. If programs take forever to load and running programs seem to stall and move more slowly than you would like, the problem could stem from insufficient RAM. A friend with a Windows Vista system complained that her PC seemed snappy when she first got it but now takes a long time to do the things she wants to do with it, such as photograph retouching in Adobe Photoshop and document layout for an online magazine she produces. Her system had only 1 GB of RAM, sufficient to run Windows Vista, but woefully insufficient for her tasks—she kept maxing out the RAM and thus the system slowed to a crawl. I replaced her stick with a pair of 2-GB sticks and suddenly she had the powerhouse workstation she desired.

Excessive hard drive activity when you move between programs points to a need for more RAM. Every Windows PC has the capability to make a portion of your hard drive look like RAM in case you run out of real RAM.

Page File

Windows uses a portion of the hard drive as an extension of system RAM, through what’s called a RAM cache. A RAM cache is a block of cylinders on a hard drive set aside as what’s called a page file, swap file, or virtual memory. When the PC starts running out of real RAM because you’ve loaded too many programs, the system swaps programs from RAM to the page file, opening more space for programs currently active. All versions of Windows use a page file, so here’s how one works.

EXAM TIP The default and recommended page-file size is 1.5 times the amount of installed RAM on your computer.

EXAM TIP The default and recommended page-file size is 1.5 times the amount of installed RAM on your computer.

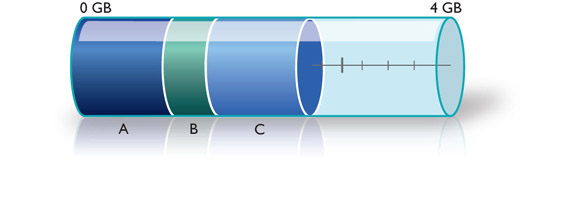

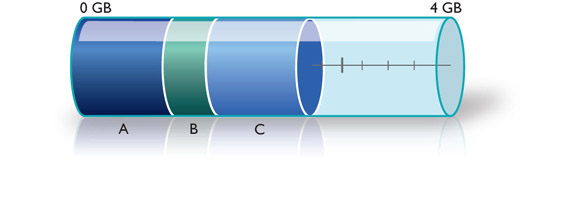

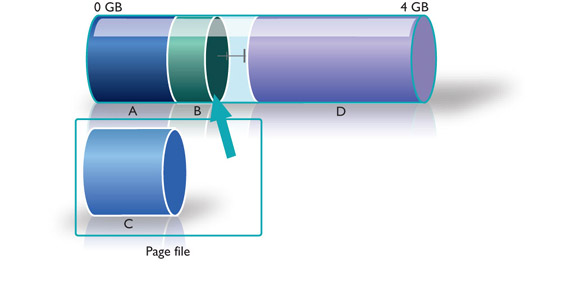

Let’s assume you have a PC with 4 GB of RAM. Figure 7-22 shows the system RAM as a thermometer with gradients from 0 to 4 GB. As programs load, they take up RAM, and as more and more programs are loaded (labeled A, B, and C in the figure), more RAM is used.

Figure 7-22 A RAM thermometer showing that more programs take more RAM

At a certain point, you won’t have enough RAM to run any more programs (see Figure 7-23). Sure, you could close one or more programs to make room for yet another one, but you can’t keep all of the programs running simultaneously. This is where virtual memory comes into play.

Figure 7-23 Not enough RAM to load program D

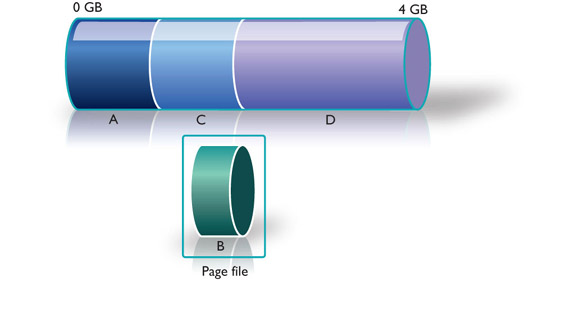

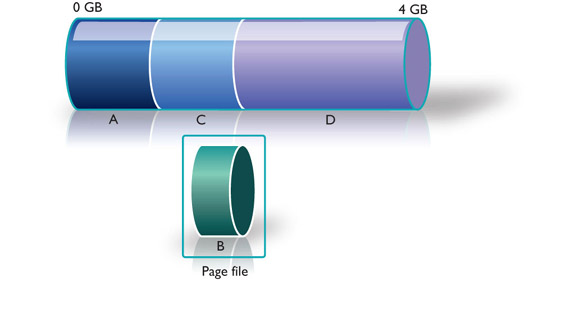

Windows’ virtual memory starts by creating a page file that resides somewhere on your hard drive. The page file works like a temporary storage box. Windows removes running programs temporarily from RAM into the page file so other programs can load and run. If you have enough RAM to run all your programs, Windows does not need to use the page file—Windows brings the page file into play only when insufficient RAM is available to run all open programs.

NOTE Virtual memory is a fully automated process and does not require any user intervention. Tech intervention is another story!

NOTE Virtual memory is a fully automated process and does not require any user intervention. Tech intervention is another story!

To load, Program D needs a certain amount of free RAM. Clearly, this requires unloading some other program (or programs) from RAM without actually closing any programs. Windows looks at all running programs—in this case A, B, and C—and decides which program is the least used. That program is then cut out of or swapped from RAM and copied into the page file. In this case, Windows has chosen Program B (see Figure 7-24). Unloading Program B from RAM provides enough RAM to load Program D (see Figure 7-25).

Figure 7-24 Program B being unloaded from memory

Figure 7-25 Program B stored in the page file, making room for Program D

It is important to understand that none of this activity is visible on the screen. Program B’s window is still visible, along with those of all the other running programs. Nothing tells the user that Program B is no longer in RAM (see Figure 7-26).

Figure 7-26 You can’t tell whether a program is swapped or not.

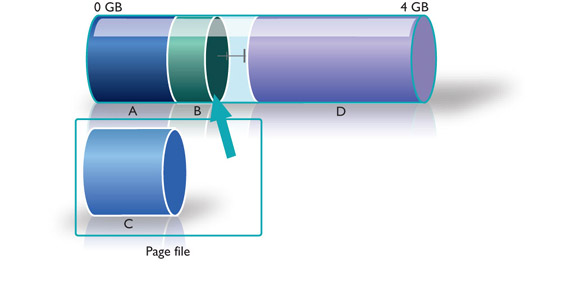

So what happens if you click on Program B’s window to bring it to the front? The program can’t actually run from the page file; it must be loaded back into RAM. First, Windows decides which program must be removed from RAM, and this time Windows chooses Program C (see Figure 7-27). Then it loads Program B into RAM (see Figure 7-28).

Figure 7-27 Program C is swapped to the page file.

Swapping programs to and from the page file and RAM takes time. Although no visual clues suggest that a swap is taking place, the machine slows down quite noticeably as Windows performs the swaps. Page files are a crucial aspect of Windows operation.

Windows handles page files automatically, but occasionally you’ll run into problems and need to change the size of the page file or delete it and let Windows re-create it automatically. The page file is PAGEFILE.SYS. You can often find it in the root directory of the C: drive, but again, that can be changed. Wherever it is, the page file is a hidden system file, which means in practice that you’ll have to play with your folder-viewing options to see it.

Figure 7-28 Program B is swapped back into RAM.

NOTE If you have a second hard drive installed in your PC, you can often get a nice performance boost by moving your page file from the C drive (the default) to the second drive. To move your page file in all versions of Windows, open the System Control Panel applet and select the Advanced tab in Windows XP or Advanced system settings menu in Windows Vista/7. This opens the System Properties dialog box. In the Performance section of the Advanced tab, click the Settings button to open the Performance Options dialog box. Select the Advanced tab, and then click the Change button in the Virtual memory section. In the Virtual Memory dialog box, select a drive from the list and give it a size or range, and you’re ready to go.

NOTE If you have a second hard drive installed in your PC, you can often get a nice performance boost by moving your page file from the C drive (the default) to the second drive. To move your page file in all versions of Windows, open the System Control Panel applet and select the Advanced tab in Windows XP or Advanced system settings menu in Windows Vista/7. This opens the System Properties dialog box. In the Performance section of the Advanced tab, click the Settings button to open the Performance Options dialog box. Select the Advanced tab, and then click the Change button in the Virtual memory section. In the Virtual Memory dialog box, select a drive from the list and give it a size or range, and you’re ready to go.

Just don’t turn virtual memory off completely. Although Windows can run without virtual memory, you will definitely take a performance hit.

If Windows needs to access the page file too frequently, you will notice the hard drive access LED going crazy as Windows rushes to move programs between RAM and the page file in a process called disk thrashing. Windows uses the page file all the time, but excessive disk thrashing suggests that you need more RAM.

You can diagnose excessive disk thrashing through simply observing the hard drive access LED flashing or through various third-party tools. I like FreeMeter (www.tiler.com/freemeter/). It’s been around for quite a while, runs on all versions of Windows, and is easy to use (see Figure 7-29). Notice on the FreeMeter screenshot that some amount of the page file is being used. That’s perfectly normal.

Figure 7-29 FreeMeter

System RAM Recommendations

Microsoft sets very low the minimum RAM requirements listed for the various Windows operating systems to get the maximum number of users to upgrade or convert, and that’s fine. A Windows XP Professional machine runs well enough on 128 MB of RAM. Just don’t ask it to do any serious computing, such as running Crysis 2! Windows Vista and Windows 7 raised the bar considerably, especially with the 64-bit versions of the operating system. Table 7-4 lists my recommendations for system RAM.

Table 7-4 Windows RAM Recommendations

Determining Current RAM Capacity

Before you go get RAM, you obviously need to know how much RAM you currently have in your PC. Windows displays this amount in the System Control Panel applet (see Figure 7-30). You can also access the screen with the WINDOWS-PAUSE/BREAK keystroke combination.

Figure 7-30 Mike has a lot of RAM!

Windows also includes the handy Performance tab in the Task Manager (as shown in Figure 7-31). The Performance tab includes a lot of information about the amount of RAM being used by your PC. Access the Task Manager by pressing CTRL-SHIFT-ESC and selecting the Performance tab.

Figure 7-31 Performance tab in Windows 7 Task Manager

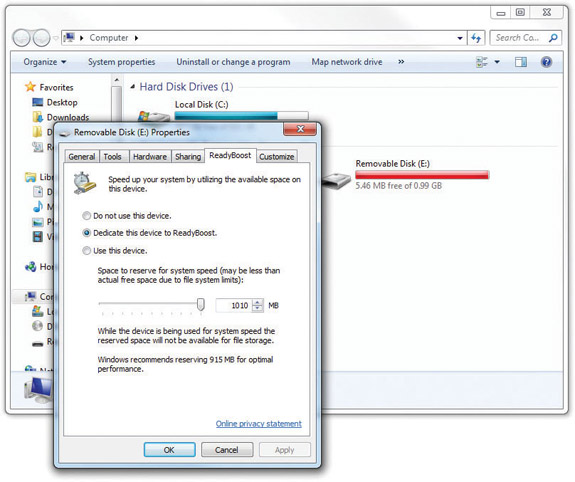

ReadyBoost

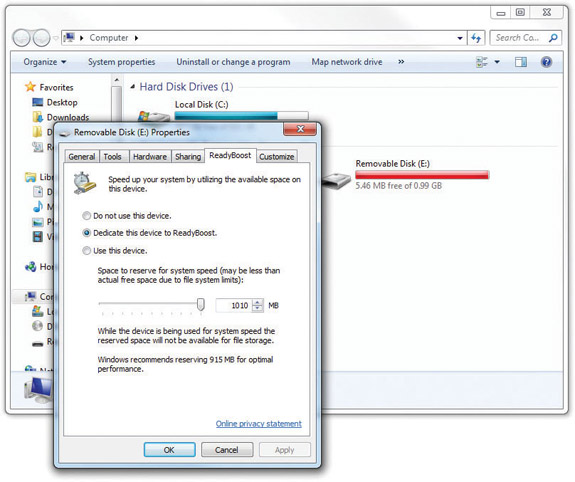

Windows Vista and Windows 7 offer a feature called ReadyBoost that enables you to use flash media devices—removable USB thumb drives or memory cards—as super fast, dedicated virtual memory. The performance gain over using only a typical hard drive for virtual memory can be significant with ReadyBoost because read/write speeds on flash memory blow hard drive read/write speeds away. Plus, the added ReadyBoost device or devices means Windows has multiple sources of virtual memory that it can use at the same time.

Windows 7 can handle up to eight flash devices, whereas Windows Vista can benefit from only one device. Devices can be between 1-32 GB in capacity. The flash device’s file system matters in terms of how much memory Windows can use. Typically, the most you’ll get out of a flash drive is 4 GB without manually changing the file system. Finally, Microsoft recommends using 1-3× the amount of system RAM for the Ready-Boost drives or devices to get optimal performance.

NOTE See Chapter 12 on file systems for the differences between FAT, FAT32, NTFS, and exFAT.

NOTE See Chapter 12 on file systems for the differences between FAT, FAT32, NTFS, and exFAT.

Plug a ReadyBoost-approved device into a USB port or built-in flash memory card reader slot. Right-click the device in Computer and select Properties. Click the Ready-Boost tab and select the radio button next to either Dedicate this device to ReadyBoost or Use this device (see Figure 7-32). Click Apply to enhance your system’s performance.

Figure 7-32 Dedicating a flash drive to Ready-Boost to enhance system performance

Getting the Right RAM

To do the perfect RAM upgrade, determine the optimum capacity of RAM to install and then get the right RAM for the motherboard. Your first two stops toward these goals are the inside of the case and your motherboard manual. Open the case to see how many sticks of RAM you have installed currently and how many free slots you have open.

Check the motherboard book to determine the total capacity of RAM the system can handle and what specific technology works with your system.

You can’t put DDR2 into a system that can only handle DDR SDRAM, after all, and it won’t do you much good to install a pair of 2-GB DIMMs when your system tops out at 1.5 GB. Figure 7-33 shows the RAM limits for my ASUS Crosshair motherboard.

Figure 7-33 The motherboard book shows how much RAM the motherboard will handle.

TIP The freeware CPU-Z program tells you the total number of slots on your motherboard, the number of slots used, and the exact type of RAM in each slot—very handy. CPU-Z not only determines the latency of your RAM but also lists the latency at a variety of motherboard speeds. The media accompanying this book has a copy of CPU-Z, so check it out.

TIP The freeware CPU-Z program tells you the total number of slots on your motherboard, the number of slots used, and the exact type of RAM in each slot—very handy. CPU-Z not only determines the latency of your RAM but also lists the latency at a variety of motherboard speeds. The media accompanying this book has a copy of CPU-Z, so check it out.

Mix and Match at Your Peril

All motherboards can handle different capacities of RAM. If you have three slots, you may put a 512-MB stick in one and a 1-GB stick in the other with a high chance of success. To ensure maximum stability in a system, however, shoot for as close as you can get to uniformity of RAM. Choose RAM sticks that match in technology, capacity, and speed.

Mixing Speeds

With so many different DRAM speeds available, you may often find yourself tempted to mix speeds of DRAM in the same system. Although you may get away with mixing speeds on a system, the safest, easiest rule to follow is to use the speed of DRAM specified in the motherboard book, and make sure that every piece of DRAM runs at that speed. In a worst-case scenario, mixing DRAM speeds can cause the system to lock up every few seconds or every few minutes. You might also get some data corruption. Mixing speeds sometimes works fine, but don’t do your tax return on a machine with mixed DRAM speeds until the system has proven to be stable for a few days. The important thing to note here is that you won’t break anything, other than possibly data, by experimenting.

Okay, I have mentioned enough disclaimers. Modern motherboards provide some flexibility regarding RAM speeds and mixing. First, you can use RAM that is faster than the motherboard specifies. For example, if the system needs PC3200 DDR2 SDRAM, you may put in PC4200 DDR2 SDRAM and it should work fine. Faster DRAM is not going to make the system run any faster, however, so don’t look for any system improvement.

Second, you can sometimes get away with putting one speed of DRAM in one bank and another speed in another bank, as long as all the speeds are as fast as or faster than the speed specified by the motherboard. Don’t bother trying to put different-speed DRAM sticks in the same bank with a motherboard that uses dual-channel DDR.

Installing DIMMs and RIMMs

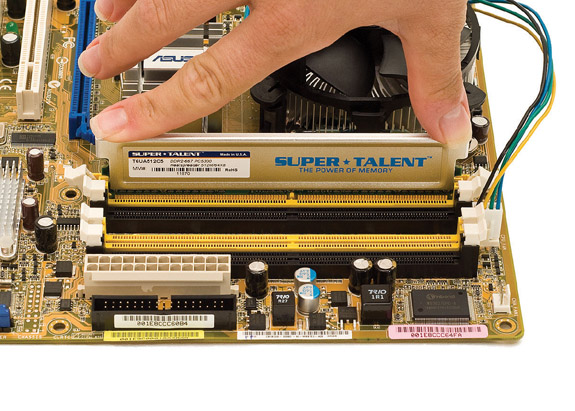

Installing DRAM is so easy that it’s one of the very few jobs I recommend to nontechie folks. First, attach an anti-static wrist strap or touch some bare metal on the power supply to ground yourself and avoid ESD. Then swing the side tabs on the RAM slots down from the upright position. Pick up a stick of RAM—don’t touch those contacts—and line up the notch or notches with the raised portion(s) of the DIMM socket (see Figure 7-34). A good hard push down is usually all you need to ensure a solid connection. Make sure that the DIMM snaps into position to show it is completely seated. Also, notice that the two side tabs move in to reflect a tight connection.

Figure 7-34 Inserting a DIMM

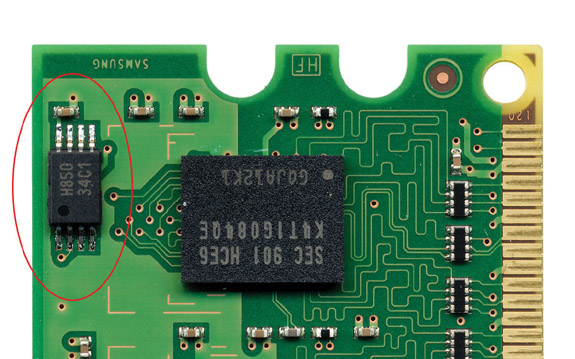

Serial Presence Detect (SPD)

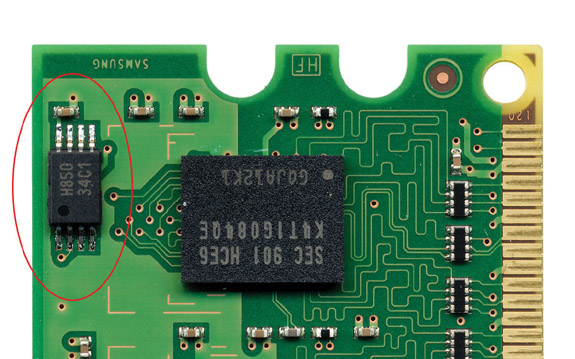

Your motherboard should detect and automatically set up any DIMM or RIMM you install, assuming you have the right RAM for the system, using a technology called serial presence detect (SPD). RAM makers add a handy chip to modern sticks called the SPD chip (see Figure 7-35). The SPD chip stores all the information about your DRAM, including size, speed, ECC or non-ECC, registered or unregistered, and a number of other more technical bits of information.

Figure 7-35 SPD chip on a stick

When a PC boots, it queries the SPD chip so that the MCC knows how much RAM is on the stick, how fast it runs, and other information. Any program can query the SPD chip. Take a look at Figure 7-36 with the results of the popular CPU-Z program showing RAM information from the SPD chip.

Figure 7-36 CPU-Z showing RAM information

All new systems count on SPD to set the RAM timings properly for your system when it boots. If you add a RAM stick with a bad SPD chip, you’ll get a POST error message and the system will not boot. You can’t fix a broken SPD chip; you just buy a new stick of RAM.

The RAM Count

After installing the new RAM, turn on the PC and watch the boot process closely. If you installed the RAM correctly, the RAM count on the PC reflects the new value (compare Figures 7.37 and 7.38). If the RAM value stays the same, you probably have installed the RAM in a slot the motherboard doesn’t want you to use (for example, you may need to use a particular slot first) or have not installed the RAM properly. If the computer does not boot and you’ve got a blank screen, you probably have not installed all the RAM sticks correctly. Usually, a good second look is all you need to determine the problem. Reseat or reinstall the RAM stick and try again. RAM counts are confusing because RAM uses megabytes and gigabytes as opposed to millions and billions. Here are some examples of how different systems would show 256 MB of RAM:

Figure 7-37 Hey, where’s the rest of my RAM?!

Figure 7-38 RAM count after proper insertion of DIMMs

268435456 (exactly 256 × 1MB)

256M (some PCs try to make it easy for you)

262,144 (number of KB)

You should know how much RAM you’re trying to install and use some common sense. If you have 512 MB and you add another 512-MB stick, you should end up with a gigabyte of RAM. If you still see a RAM count of 524582912 after you add the second stick, something went wrong!

Installing SO-DIMMs in Laptops

It wasn’t that long ago that adding RAM to a laptop was either impossible or required you to send the system back to the manufacturer. For years, every laptop maker had custom-made, proprietary RAM packages that were difficult to handle and staggeringly expensive. The wide acceptance of SO-DIMMs over the past few years has virtually erased these problems. All laptops now provide relatively convenient access to their SO-DIMMs, enabling easy replacement or addition of RAM.

Access to RAM usually requires removing a panel or lifting up the keyboard—the procedure varies among laptop manufacturers. Figure 7-39 shows a typical laptop RAM access panel. You can slide the panel off to reveal the SO-DIMMs. SO-DIMMs usually insert exactly like the old SIMMs; slide the pins into position and snap the SO-DIMM down into the retaining clips (see Figure 7-40).

Figure 7-39 A RAM access panel on a laptop

Figure 7-40 Snapping in a SO-DIMM

Before doing any work on a laptop, turn the system off, disconnect it from the AC wall socket, and remove all batteries. Use an anti-static wrist strap because laptops are far more susceptible to ESD than desktop PCs.

802

Troubleshooting RAM

“Memory” errors show up in a variety of ways on modern systems, including parity errors, ECC error messages, system lockups, page faults, and other error screens in Windows. These errors can indicate bad RAM but often point to something completely unrelated. This is especially true with intermittent problems. Techs need to recognize these errors and determine which part of the system caused the memory error.

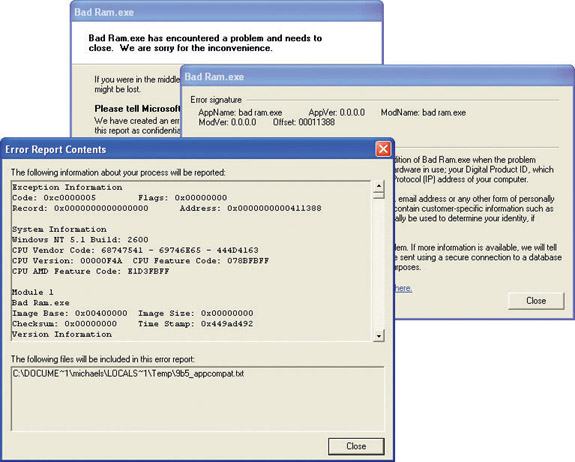

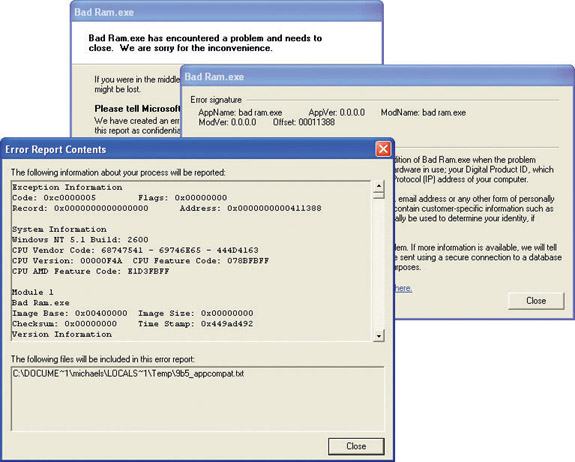

You can get two radically different types of parity errors: real and phantom. Real parity errors are simply errors that the MCC detects from the parity or ECC chips (if you have them). The operating system then reports the problem in an error message, such as “Parity error at xxxx:xxxxxxxx,” where xxxx:xxxxxxxx is a hexadecimal value (a string of numbers and letters, such as A5F2:004EEAB9). If you get an error like this, write down the value (see Figure 7-41). A real parity/ECC error shows up at the same place in memory each time and almost always indicates that you have a bad RAM stick.

Figure 7-41 Windows error message

Phantom parity errors show up on systems that don’t have parity or ECC memory. If Windows generates parity errors with different addresses, you most likely do not have a problem with RAM. These phantom errors can occur for a variety of reasons, including software problems, heat or dust, solar flares, fluctuations in the Force.. .you get the idea.

System lockups and page faults (they often go hand in hand) in Windows can indicate a problem with RAM. A system lockup is when the computer stops functioning. A page fault is a milder error that can be caused by memory issues but not necessarily system RAM problems. Certainly page faults look like RAM issues because Windows generates frightening error messages filled with long strings of hexadecimal digits, such as “KRNL386 caused a page fault at 03F2:25A003BC.” Just because the error message contains a memory address, however, does not mean that you have a problem with your RAM. Write down the address. If it repeats in later error messages, you probably have a bad RAM stick. If Windows displays different memory locations, you need to look elsewhere for the culprit.

Every once in a while, something potentially catastrophic happens within the PC, some little electron hits the big red panic button, and the operating system has to shut down certain functions before it can save data. This panic button inside the PC is called a nonmaskable interrupt (NMI), more simply defined as an interruption the CPU cannot ignore. An NMI manifests to the user as what techs lovingly call the Blue Screen of Death (BSoD)—a bright blue screen with a scary-sounding error message on it (see Figure 7-42).

Figure 7-42 Blue Screen of Death

Bad RAM sometimes triggers an NMI, although often the culprit lies with buggy programming or clashing code. The BSoD varies according to the operating system, and it would require a much lengthier tome than this one to cover all the variations. Suffice it to say that RAM could be the problem when that delightful blue screen appears.

Finally, intermittent memory errors can come from a variety of sources, including a dying power supply, electrical interference, buggy applications, buggy hardware, and so on. These errors show up as lockups, general protection faults, page faults, and parity errors, but they never have the same address or happen with the same applications. I always check the power supply first.

Testing RAM

Once you discover that you may have a RAM problem, you have a couple of options. First, several companies manufacture hardware RAM-testing devices, but unless you have a lot of disposable income, they’re probably priced way too high for the average tech ($1,500 and higher). Second, you can use the method I use—replace and pray. Open the system case and replace each stick, one at a time, with a known good replacement stick. (You have one of those lying around, don’t you?) This method, although potentially time-consuming, certainly works. With PC prices as low as they are now, you could simply replace the whole system for less than the price of a dedicated RAM tester.

Third, you could run a software-based tester on the RAM. Because you have to load a software tester into the memory it’s about to scan, there’s always a small chance that simply starting the software RAM tester might cause an error. Still, you can find some pretty good free ones out there. Windows 7 includes the Memory Diagnostics Tool, which can automatically scan your computer’s RAM when you encounter a problem. If you’re using another OS, my favorite tool is the venerable Memtest86 written by Mr. Chris Brady (www.memtest86.com). Memtest86 exhaustively checks your RAM and reports bad RAM when it finds it (see Figure 7-43).

Figure 7-43 Memtest86 in action

NOTE A general protection fault (GPF) is an error that can cause an application to crash. Often GPFs are caused by programs stepping on each other’s toes. Chapter 19 goes into more detail on GPFs and other Windows errors.

NOTE A general protection fault (GPF) is an error that can cause an application to crash. Often GPFs are caused by programs stepping on each other’s toes. Chapter 19 goes into more detail on GPFs and other Windows errors.

Chapter Review

Questions

1. Steve adds a second 1-GB 240-pin DIMM to his PC, which should bring the total RAM in the system up to 2 GB. The PC has an Intel Core 2 Duo 3-GHz processor and three 240-pin DIMM slots on the motherboard. When he turns on the PC, however, only 1 GB of RAM shows up during the RAM count. Which of the following is most likely to be the problem?

A. Steve failed to seat the RAM properly.

B. Steve put DDR SDRAM in a DDR 2 slot.

C. The CPU cannot handle 2 GB of RAM.

D. The motherboard can use only one RAM slot at a time.

2. Scott wants to add 512 MB of PC100 SDRAM to an aging but still useful desktop system. The system has a 100-MHz motherboard and currently has 256 MB of non-ECC SDRAM in the system. What else does he need to know before installing?

A. What speed of RAM he needs.

B. What type of RAM he needs.

C. How many pins the RAM has.

D. If the system can handle that much RAM.

3. What is the primary reason that DDR2 RAM is faster than DDR RAM?

A. The core speed of the DDR2 RAM chips is faster.

B. The input/output speed of the DDR2 RAM is faster.

C. DDR RAM is single-channel and DDR2 RAM is dual-channel.

D. DDR RAM uses 184-pin DIMMs and DDR2 uses 240-pin DIMMs.

4. What is the term for the delay in the RAM’s response to a request from the MCC?

A. Variance

B. MCC gap

C. Latency

D. Fetch interval

5. Rico has a motherboard with four RAM slots that doesn’t seem to work. He has two RDRAM RIMMs installed, for a total of 1 GB of memory, but the system won’t boot. What is likely to be the problem?

A. The motherboard requires SDRAM, not RDRAM.

B. The motherboard requires DDR SDRAM, not RDRAM.

C. The motherboard requires all four slots filled with RDRAM.

D. The motherboard requires the two empty slots to be filled with CRIMMs for termination.

6. Silas has an AMD-based motherboard with two sticks of DDR2 RAM installed in two of the three RAM slots, for a total of 2 GB of system memory. When he runs CPU-Z to test the system, he notices that the software claims he’s running single-channel memory. What could be the problem? (Select the best answer.)

A. His motherboard only supports single-channel memory.

B. His motherboard only supports dual-channel memory with DDR RAM, not DDR2.

C. He needs to install a third RAM stick to enable dual-channel memory.

D. He needs to move one of the installed sticks to a different slot to activate dual-channel memory.

7. Which of the following Control Panel applets will display the amount of RAM in your PC?

A. System

B. Devices and Printers

C. Device Manager

D. Action Center

8. What is the best way to determine the total capacity and specific type of RAM your system can handle?

A. Check the motherboard book.

B. Open the case and inspect the RAM.

C. Check the Device Manager.

D. Check the System utility in the Control Panel.

9. Gregor installed a third stick of known good RAM into his Core i7 system, bringing the total amount of RAM up to 3 GB. Within a few days, though, he started having random lockups and reboots, especially when doing memory-intensive tasks such as gaming. What is most likely the problem?

A. Gregor installed DDR RAM into a DDR2 system.

B. Gregor installed DDR2 RAM into a DDR3 system.

C. Gregor installed RAM that didn’t match the speed or quality of the RAM in the system.

D. Gregor installed RAM that exceeded the speed of the RAM in the system.

10. Cindy installs a second stick of DDR2 RAM into her Core 2 Duo system, bringing the total system memory up to 2 GB. Within a short period of time, though, she begins experiencing Blue Screens of Death. What could the problem be?

A. She installed faulty RAM.

B. The motherboard could only handle 1 GB of RAM.

C. The motherboard needed dual-channel RAM.

D. There is no problem. Windows always does this initially, but gets better after crashing a few times.

Answers

1. A. Steve failed to seat the RAM properly.

2. D. Scott needs to know if the system can handle that much RAM.

3. B. The input/output speed of DDR2 RAM is faster than that of DDR RAM (although the latency is higher).

4. C. Latency is the term for the delay in the RAM’s response to a request from the MCC.

5. D. RDRAM-based motherboards require empty slots to be filled with CRIMMs for termination.

6. D. Motherboards can be tricky and require you to install RAM in the proper slots to enable dual-channel memory access. In this case, Silas should move one of the installed sticks to a different slot to activate dual-channel memory. (And he should check the motherboard manual for the proper slots.)

7. A. You can use the System applet to see how much RAM is currently in your PC.

8. A. The best way to determine the total capacity and specific type of RAM your system can handle is to check the motherboard book.

9. C. Most likely, Gregor installed RAM that didn’t match the speed or quality of the RAM in the system.

10. A. If you have no problems with a system and then experience problems after installing something new, chances are the something new is at fault.

TIP The CompTIA A+ certification domains use the term memory to describe the short-term storage used by the PC to load the operating system and running applications. The more common term in the industry is RAM, for random access memory, the kind of short-term memory you’ll find in every computer. More specifically, the primary system RAM is dynamic random access memory (DRAM). For the most part, this book uses the terms RAM and DRAM.

TIP The CompTIA A+ certification domains use the term memory to describe the short-term storage used by the PC to load the operating system and running applications. The more common term in the industry is RAM, for random access memory, the kind of short-term memory you’ll find in every computer. More specifically, the primary system RAM is dynamic random access memory (DRAM). For the most part, this book uses the terms RAM and DRAM.

NOTE Some MCCs are 128 bits wide.

NOTE Some MCCs are 128 bits wide.

EXAM TIP The default and recommended page-file size is 1.5 times the amount of installed RAM on your computer.

EXAM TIP The default and recommended page-file size is 1.5 times the amount of installed RAM on your computer.