In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Explain how the Internet works

• Connect to the Internet

• Use Internet application protocols

• Troubleshoot an Internet connection

Imagine coming home from a long day at work building and fixing PCs, sitting down in front of your shiny new computer, double-clicking the single icon that sits dead center on your monitor…and suddenly you’re enveloped in an otherworldly scene, where 200-foot trees slope smoothly into snow-white beaches and rich blue ocean. Overhead, pterodactyls soar through the air while you talk to a small chap with pointy ears and a long robe about heading up the mountain in search of a giant monster.… A TV show from the Syfy channel? Spielberg’s latest film offering? How about an interactive game played by millions of people all over the planet on a daily basis by connecting to the Internet? If you guessed the last one, you’re right.

This chapter covers the skills you need as a PC tech to help people connect to the Internet. It starts with a brief section on how the Internet works, along with the concepts of connectivity, and then it goes into the specifics on hardware, protocols, and software that you use to make the Internet work for you (or for your client). Finally, you’ll learn how to troubleshoot a bad Internet connection. Let’s get started!

Thanks to the Internet, people can communicate with one another over vast distances, often in the blink of an eye. As a PC tech, you need to know how PCs communicate with the larger world for two reasons. First, knowing the process and pieces involved in the communication enables you to troubleshoot effectively when that communication goes away. Second, you need to be able to communicate knowledgeably with a network technician who comes in to solve a more complex issue.

You probably know that the Internet is millions and millions of computers all joined together to form the largest network on earth, but not many folks know much about how these computers are organized. To keep everything running smoothly, the Internet is broken down into groups called tiers. The main tier, called Tier 1, consists of nine companies called Tier 1 providers. The Tier 1 providers own long-distance, highspeed fiber-optic networks called backbones. These backbones span the major cities of the earth (not all Tier 1 backbones go to all cities) and interconnect at special locations called network access points (NAPs). Anyone wishing to connect to any of the Tier 1 providers must pay large sums of money. The Tier 1 providers do not charge each other to connect.

Tier 2 providers own smaller, regional networks and must pay the Tier 1 providers. Most of the famous companies that provide Internet access to the general public are Tier 2 providers. Tier 3 providers are even more regional and connect to Tier 2 providers.

The piece of equipment that makes this tiered Internet concept work is called a backbone router. Backbone routers connect to more than one other backbone router, creating a big, interwoven framework for communication. Figure 24-1 illustrates the decentralized and interwoven nature of the Internet. The key reason for interweaving the backbones of the Internet was to provide alternative pathways for data if one or more of the routers went down. If Jane in Houston sends a message to her friend Polly in New York City, for example, the shortest path between Jane and Polly in this hypothetical situation is this: Jane’s message originates at Rice University in Houston, bounces to Emory University in Atlanta, flits through Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, and then zips into SUNY in New York City (see Figure 24-2). Polly happily reads the message and life is great. The Internet functions as planned.

Figure 24-1 Internet Tier 1 connections

Figure 24-2 Message traveling from Houston to NYC

But what happens if the entire southeastern United States experiences a huge power outage and Internet backbones in every state from Virginia to Florida go down? Jane’s message would bounce back to Rice and the Rice computers. Being smart cookies, the routers would reroute the message to nodes that still functioned—say, Rice to University of Chicago, to University of Toronto, and then to SUNY (see Figure 24-3). It’s all in a day’s work for the highly redundant and adaptable Internet. At this point in the game, the Internet simply cannot go down fully—barring, of course, a catastrophe of Biblical proportions.

Figure 24-3 Rerouted message from Houston to NYC

As you know from all the earlier chapters in this book, hardware alone doesn’t cut it in the world of computing. You need software to make the machines run and create an interface for humans. The Internet is no exception. TCP/IP provides the basic software structure for communication on the Internet.

Because you spent a good deal of Chapter 22 working with TCP/IP, you should have an appreciation for its adaptability and, perhaps more importantly, its extendibility. TCP/IP provides the addressing scheme for computers that communicate on the Internet through IP addresses, such as 192.168.4.1 or 16.45.123.7. As a protocol, though, TCP/IP is much more than just an addressing system. TCP/IP provides the framework and common language for the Internet. And it offers a phenomenally wide-open structure for creative purposes. Programmers can write applications built to take advantage of the TCP/IP structure and features, creating what are called TCP/IP services. The cool thing about TCP/IP services is that they’re limited only by the imagination of the programmers.

At this point, you have an enormous, beautifully functioning network. All the backbone routers connect with fiber and thick copper cabling backbones, and TCP/IP enables communication and services for building applications for humans to interface across the distances. What’s left? Oh, that’s right: how do you tap into this great network and partake of its goodness?

Every Tier 1 and Tier 2 provider leases connections to the Internet to companies called Internet service providers (ISPs). ISPs essentially sit along the edges of the Tier 1 and Tier 2 Internet and tap into the flow. You can, in turn, lease some of the connections from the ISP and thus get on the Internet.

ISPs come in all sizes. Comcast, the cable television provider, has multiple, huge-capacity connections into the Internet, enabling its millions of customers to connect from their local machines and surf the Web. Contrast Comcast with Unisono, an ISP in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico (see Figure 24-4). Billed as the “the fastest Internet service” in San Miguel de Allende, it services only a small (but delightful) community and the busy tourist crowd.

Figure 24-4 Unisono homepage

Connecting to an ISP requires two things to work perfectly: hardware for connectivity, such as a modem and a working cable line; and software, such as protocols to govern the connections and the data flow (all configured in Windows) and applications to take advantage of the various TCP/IP services. Once you have a contract with an ISP to grant you access to the Internet, a technician will often install your Internet connection device and any software you need. With most ISPs, a DHCP server will provide your PC with the proper TCP/IP information. As you know, the router to which you connect at the ISP is often referred to as the default gateway. Once your PC is configured, you can connect to the ISP and get to the greater Internet. Figure 24-5 shows a standard PC-to-ISP-to-Internet connection. Note that various protocols and other software manage the connectivity between your PC and the default gateway.

Figure 24-5 Simplified Internet connectivity

PCs commonly connect to an ISP by using one of nine technologies that fit into four categories: dial-up, both analog and ISDN; dedicated, such as DSL, cable, fiber, and LAN; wireless, including cellular and WiMAX; and satellite. Analog dial-up is the slowest of the bunch and requires a telephone line and a special networking device called a modem. ISDN uses digital dial-up and has much greater speed. Dedicated connections (cable and DSL) most often use a box that connects to a regular Ethernet NIC like you played with in Chapter 22. Wireless connections are a mixed bag, depending on the device and service you have. Some are built-in, while others use a box you attach to your LAN. Satellite is the odd one out here; it may use either a modem or a NIC, depending on the particular configuration you have, although most folks will use a NIC. Let’s take a look at all these various connection options, and then finish this section by discussing basic router configuration and Internet Connection Sharing in Windows.

A dial-up connection to the Internet requires two pieces to work: hardware to dial the ISP, such as a modem or ISDN terminal adapter; and software to govern the connection, such as Microsoft’s Dial-up Networking (DUN). Let’s look at the hardware first, and then we’ll explore software configuration.

At some point in the early days of computing, some bright guy or gal noticed a colleague talking on a telephone, glanced down at a PC, and then put two and two together: why not use telephone lines for data communication? The basic problem with this idea is that traditional telephone lines use analog signals, while computers use digital signals (see Figure 24-6). Creating a dial-up network required equipment that could turn digital data into an analog signal to send it over the telephone line, and then turn it back into digital data when it reached the other end of the connection. A device called a modem solved this dilemma.

Figure 24-6 Analog signals used by a telephone line versus digital signals used by the computer

Modems enable computers to talk to each other via standard commercial telephone lines by converting analog signals to digital signals, and vice versa. The term modem is short for modulator/demodulator, a description of transforming the signals. Telephone wires transfer data via analog signals that continuously change voltages on a wire. Computers hate analog signals. Instead, they need digital signals, voltages that are either on or off, meaning the wire has voltage present or it does not. Computers, being binary by nature, use only two states of voltage: zero volts and positive volts. Modems take analog signals from telephone lines and turn them into digital signals that the PC can understand (see Figure 24-7). Modems also take digital signals from the PC and convert them into analog signals for the outgoing telephone line.

Figure 24-7 Modem converting analog signal to digital signal

A modem does what is called serial communication: It transmits data as a series of individual ones and zeros. The CPU can’t process data this way. It needs parallel communication, transmitting and receiving data in discrete 8-bit chunks (see Figure 24-8). The individual serial bits of data are converted into 8-bit parallel data that the PC can understand through the universal asynchronous receiver/transmitter (UART) chip (see Figure 24-9).

Figure 24-8 CPUs can’t read serial data.

Figure 24-9 The UART chip converts serial data to parallel data that the CPU can read.

There are many types of UARTs, each with different functions. All serial communication devices are really little more than UARTs. External modems can convert analog signals to digital ones and vice versa, but they must rely on the serial ports to which they’re connected for the job of converting between serial and parallel data (see Figure 24-10). Internal modems can handle both jobs because they have their own UART built in (see Figure 24-11).

Figure 24-10 An external modem uses the PC’s serial port.

Figure 24-11 An internal modem has UART built in.

Phone lines have a speed based on a unit called a baud, which is one cycle per second. The fastest rate that a phone line can achieve is 2400 baud. Modems can pack multiple bits of data into each baud; a 33.6 kilobits per second (Kbps) modem, for example, packs 14 bits into every baud: 2400 × 14 = 33.6 Kbps. Thus, it is technically incorrect to say, “I have a 56-K baud modem.” The correct statement is, “I have a 56-Kbps modem.” But don’t bother; people have used the term “baud” instead of bits per second (bps) so often for so long that the terms have become functionally synonymous.

Modem Connections Internal modems connect to the PC very differently from how external modems connect. Almost all internal modems connect to a PCI or PCI Express expansion bus slot inside the PC, although cost-conscious manufacturers may use smaller modems that fit in special expansion slots designed to support multiple communications features such as modems, NICs, and sound cards (see Figure 24-12). Older AMD motherboards used Audio/Modem Riser (AMR) or Advanced Communication Riser (ACR) slots, while Intel motherboards used Communication and Networking Riser (CNR) slots.

Figure 24-12 A CNR modem

NOTE AMR, ACR, and CNR slots have gone away, though you’ll still find them on older systems. Current systems use built-in components or PCIe × 1 slots for modems, sound, and NICs.

NOTE AMR, ACR, and CNR slots have gone away, though you’ll still find them on older systems. Current systems use built-in components or PCIe × 1 slots for modems, sound, and NICs.

External modems connect to the PC through an available serial port (the old way) or USB port (see Figure 24-13). USB offers simple plug and play and easy portability between machines, plus such modems require no external electrical source, getting all the power they need from the USB connection.

Figure 24-13 A USB modem

The software side of dial-up networks requires configuration within Windows to include information provided by your ISP. The ISP provides a dial-up telephone number or numbers, as well as your user name and initial password. In addition, the ISP will tell you about any special configuration options you need to specify in the software setup. The full configuration of dial-up networking is beyond the scope of this book, but you should at least know where to go to follow instructions from your ISP. Let’s take a look at the Network and Internet Connections applet in Windows XP.

Configuring Dial-up To start configuring a dial-up connection in Windows XP, open the Control Panel. Select Network and Internet Connections from the Pick a category menu and then choose Set up or change your Internet connection from the Pick a task menu. The Internet Properties dialog box opens with the Connections tab displayed (see Figure 24-14). All your work will proceed from here.

Figure 24-14 The Connections tab in the Internet Properties dialog box

Click the Setup button to run the New Connection Wizard (see Figure 24-15), and then work through the screens. At this point, you’re going to need information provided by your ISP to configure your connection properly. When you finish the configuration, you’ll see a new Connect To option on the Start menu if your system is set up that way. If not, open up Network Connections, and your new dial-up connection will be available. Figure 24-16 shows the option to connect to a fictitious ISP, Cool-Rides.com.

Figure 24-15 The New Connection Wizard

Figure 24-16 Connection options in Network Connections

Windows Vista and 7 handle dial-up connections in the same way. Open the Network and Sharing Center and click on Set up a new connection or network (see Figure 24-17).

Figure 24-17 Set up a connection or network in Windows 7

Select Set up a dial-up connection on the next screen and then enter your dial-up information, as shown in Figure 24-18.

Figure 24-18 Creating a dial-up connection in Windows 7

PPP Dial-up links to the Internet have their own special hardware protocol called Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP). PPP is a streaming protocol developed especially for dial-up Internet access. To Windows, a modem is nothing more than a special type of network adapter. You can configure a new dial-up connection in the Network and Sharing Center in Vista/7 or the Network Connections applet in XP.

Most dial-up “I can’t connect to the Internet”-type problems are user errors. Your first area of investigation is the modem itself. Use the modem’s properties to make sure the volume is turned up. Have the user listen to the connection. Does she hear a dial tone? If she doesn’t, make sure the modem’s line is plugged into a good phone jack. Does she hear the modem dial and then hear someone saying, “Hello? Hello?” If so, she probably dialed the wrong number! Wrong password error messages are fairly straightforward—remember that the password may be correct but the user name may be wrong. If she still fails to connect, it’s time to call the network folks to see what is not properly configured in her dial-up modem’s Properties dialog box.

A standard telephone connection comprises many pieces. First, the phone line runs from your phone out to a network interface box (the little box on the side of your house) and into a central switch belonging to the telephone company. (In some cases, intermediary steps are present.) Standard metropolitan areas have a large number of central offices, each with a central switch. Houston, Texas, for example, has nearly 100 offices in the general metro area. These central switches connect to each other through high-capacity trunk lines. Before 1970, the entire phone system was analog; over time, however, phone companies began to upgrade their trunk lines to digital systems. Today, the entire telephone system, with the exception of the line from your phone to the central office, and sometimes even that, is digital.

During this upgrade period, customers continued to demand higher throughput from their phone lines. The old telephone line was not expected to produce more than 28.8 Kbps (56-K modems, which were a big surprise to the phone companies, didn’t appear until 1995). Needless to say, the phone companies were very motivated to come up with a way to generate higher capacities. Their answer was actually fairly straightforward: make the entire phone system digital. By adding special equipment at the central office and the user’s location, phone companies can now achieve a throughput of up to 64 K per line (see the paragraphs following) over the same copper wires already used by telephone lines. This process of sending telephone transmission across fully digital lines end-to-end is called integrated services digital network (ISDN) service.

ISDN service consists of two types of channels: Bearer, or B, channels and Delta, or D, channels. B channels carry data and voice information at 64 Kbps. D channels carry setup and configuration information and carry data at 16 Kbps. Most providers of ISDN allow the user to choose either one or two B channels. The more common setup is two B/one D, usually called a basic rate interface (BRI) setup. A BRI setup uses only one physical line, but each B channel sends 64 Kbps, doubling the throughput total to 128 Kbps. ISDN also connects much faster than modems, eliminating that long, annoying, mating call you get with phone modems. The monthly cost per B channel is slightly more than a regular phone line, and usually a fairly steep initial fee is levied for the installation and equipment. The big limitation is that you usually need to be within about 18,000 feet of a central office to use ISDN.

The physical connections for ISDN bear some similarity to analog modems. An ISDN wall socket usually looks something like a standard RJ-45 network jack. The most common interface for your computer is a device called a terminal adapter (TA). TAs look much like regular modems, and like modems, they come in external and internal variants. You can even get TAs that connect directly to your LAN.

NOTE Another type of ISDN, called a primary rate interface (PRI), is composed of twenty-three 64-Kbps B channels and one 64-Kbps D channel, giving it a total throughput of 1.544 megabits per second. PRI ISDN lines are also known as TI lines.

NOTE Another type of ISDN, called a primary rate interface (PRI), is composed of twenty-three 64-Kbps B channels and one 64-Kbps D channel, giving it a total throughput of 1.544 megabits per second. PRI ISDN lines are also known as TI lines.

Digital subscriber line (DSL) connections to ISPs use a standard telephone line but special equipment on each end to create always-on Internet connections at blindingly fast speeds, especially when compared with analog dial-up connections. Service levels vary around the United States, but the typical upload speed is ~768 Kbps, while download speed comes in at ~3+ Mbps.

NOTE The two most common forms of DSL you’ll find are asynchronous (ADSL) and synchronous (SDSL). ADSL lines differ between slow upload speed (such as 384 Kbps, 768 Kbps, and 1 Mbps) and faster download speed (usually 3–15 Mbps). SDSL has the same upload and download speeds, but telecom companies charge a lot more for the privilege. DSL encompasses many such variations, so you’ll often see it referred to as xDSL.

NOTE The two most common forms of DSL you’ll find are asynchronous (ADSL) and synchronous (SDSL). ADSL lines differ between slow upload speed (such as 384 Kbps, 768 Kbps, and 1 Mbps) and faster download speed (usually 3–15 Mbps). SDSL has the same upload and download speeds, but telecom companies charge a lot more for the privilege. DSL encompasses many such variations, so you’ll often see it referred to as xDSL.

DSL requires little setup from a user standpoint. A tech comes to the house to install the DSL receiver, often called a DSL modem (see Figure 24-19), and possibly hook up a wireless router. The receiver connects to the telephone line and the PC (see Figure 24-20). The tech (or the user, if knowledgeable) then configures the DSL modem and router (if there is one) with the settings provided by the ISP, and that’s about it! Within moments, you’re surfing the Web. You don’t need a second telephone line. You don’t need to wear a special propeller hat or anything. The only kicker is that your house has to be within a fairly short distance from a main phone service switching center (central office), something like 18,000 feet.

Figure 24-19 A DSL receiver

Figure 24-20 DSL connections

Cable offers a different approach to high-speed Internet access, using regular cable TV cables to serve up lightning-fast speeds. It offers faster service than most DSL connections, with a 1–10 Mbps upload and 6–100+ Mbps download. Cable Internet connections are theoretically available anywhere you can get cable TV.

Cable Internet connections start with an RG-6 or RG-59 cable coming into your house. The cable connects to a cable modem that then connects to a small home router or your NIC via Ethernet. Figure 24-21 shows a typical cable setup using a router.

Figure 24-21 Cable connections

NOTE The term modem has been warped and changed beyond recognition in modern networking. Both DSL and cable—fully digital Internet connections—use the term modem to describe the box that takes the incoming signal from the Internet and translates it into something the PC can understand.

NOTE The term modem has been warped and changed beyond recognition in modern networking. Both DSL and cable—fully digital Internet connections—use the term modem to describe the box that takes the incoming signal from the Internet and translates it into something the PC can understand.

Most businesses connect their internal local area network (LAN) to an ISP-supplied Ethernet network. Figure 24-22 shows a typical small-business wiring closet with routers that connect the LAN to the ISP’s Ethernet. You learned all about wiring up a LAN in Chapter 22, so there’s no need to go through any basics here. To complete a LAN connection to the Internet, you need a router to connect the ISP’s network to your network. Most office buildings come with preinstalled Ethernet at varying speeds.

Figure 24-22 A wiring closet

802.11 Wireless is so prevalent that for many of us it’s the way we get to the Internet. Wireless access points (WAPs) designed to serve the public abound in coffee shops, airports, fast-food chains, and bars. Even some cities provide partial to full 802.11 coverage.

We covered 802.11 in detail in Chapter 23, so there’s no reason to repeat the process of connecting to a hotspot. However, do remember that most hotspots do not provide any level of encryption, meaning it’s a trivial task for a bad guy to monitor your connection and read everything you send or receive.

CAUTION Secure your public hotspot Web browsing using HTTPS-secured sites. It’s surprisingly easy to do. Instead of typing facebook.com, for example, type in https://facebook.com or use a service like the Electronic Freedom Federation’s HTTPS Everywhere.

CAUTION Secure your public hotspot Web browsing using HTTPS-secured sites. It’s surprisingly easy to do. Instead of typing facebook.com, for example, type in https://facebook.com or use a service like the Electronic Freedom Federation’s HTTPS Everywhere.

802.11 works well as an Internet access option for densely populated areas, but 802.11’s short range makes it impractical in areas where it’s not easy to place new access points.

NOTE An 802.11 network that covers a single city is an excellent example of a Metropolitan Area Network (MAN).

NOTE An 802.11 network that covers a single city is an excellent example of a Metropolitan Area Network (MAN).

Until recently, high costs meant that only those with money to burn could enjoy the super-fast speeds of a fiber connection. Now DSL providers have developed very popular fiber-to-the-node (FTTN) and fiber-to-the-premises (FTTP) services that provide Internet (and more), making them head-to-head competitors with the cable companies. With FTTN, the fiber connection runs from the provider to a box somewhere in your neighborhood. This box is connected to your home or office using normal coaxial or Ethernet cabling. FTTP runs from the provider straight to a home or office, using fiber the whole way. Once inside the home or office, you can use any standard cabling (or wireless) to connect your PCs to the Internet. One popular FTTN service is AT&T’s U-verse, which offers speeds up to 24 Mbps for downloads and 3 Mbps for uploads (see Figure 24-23). Verizon’s FiOS service is the most popular and widely available FTTP service in the United States, providing download speeds up to 150 Mbps and upload speeds up to 50 Mbps (if you can afford it, of course).

Figure 24-23 U-verse gateway

Who needs computers when you can get online with any number of mobile devices? Okay, there are plenty of things a smartphone or tablet can’t do, but with the latest advances in cellular data services, your mobile Internet experience will feel a lot more like your home Internet experience than it ever has before.

Cellular data services have gone through a number of names over the years, so many that trying to keep track of them and place them in any order is extremely challenging. In an attempt to make organization somewhat clearer, the cellular industry developed a string of marketing terms using the idea of generations: first generation devices are called 1G, second generation are 2G, followed by 3G and 4G. On top of that, many technologies use G-names such as 2.5G to show they’re not 2G but not quite 3G. You’ll see these terms all over the place, especially on your phones (see Figure 24-24). Marketing folks tend to bend and flex the definition of these terms in advertisements, so you should always read more about the device and not just its generation.

Figure 24-24 iPhone with 4G showing

NOTE The CompTIA A+ will not ask you to define a G-level for a particular cellular technology.

NOTE The CompTIA A+ will not ask you to define a G-level for a particular cellular technology.

The first generation (1G) of cell phone data services was analog and not at all designed to carry packetized data. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that two fully digital technologies called the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) and code division multiple access (CDMA) came into wide acceptance. GSM evolved into GPRS and EDGE, while CDMA introduced EV-DO. GPRS and EDGE were 2.5G technologies, while EV-DO was true 3G. Current standards, with names like UTMS, HSPA+, and HSDPA, have brought GSM-based networks into the world of 3G and 3.5G. Current mobile data services provide real-world download speeds around 3 or 4 Mbps.

The current cutting-edge set of cellular technologies use the term 4G. The two biggest 4G technologies currently available are called Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access (WiMAX) and 3GPP Long Term Evolution (LTE). With these networks, you’ll see download speeds closer to 10 Mbps, though WiMAX lags behind LTE in the speed department. In fact, while the CompTIA A+ 220-801 exam objectives specifically cover WiMAX, the wireless technology has already been replaced as the 4G frontrunner. The only major U.S. WiMAX carrier, Clearwire, Inc., has declared their intentions to adopt LTE, along with every other major mobile phone network in the United States. But since CompTIA asked, and there are plenty of WiMAX users (for now), I’m more than happy to tell you a little more about WiMAX.

EXAM TIP You can share your smartphone’s or tablet’s connection to a cellular network using a process called tethering. You’ll need to turn on the service on your device, then connect your phone to your computer, either wirelessly as a mobile hotspot or directly using a USB connection. Most carriers charge extra to enable tethering on your smartphone or tablet. Check with your carrier to see if your service plan supports tethering.

EXAM TIP You can share your smartphone’s or tablet’s connection to a cellular network using a process called tethering. You’ll need to turn on the service on your device, then connect your phone to your computer, either wirelessly as a mobile hotspot or directly using a USB connection. Most carriers charge extra to enable tethering on your smartphone or tablet. Check with your carrier to see if your service plan supports tethering.

WiMAX runs at (depending on distance from a tower) a maximum speed of around 10 Mbps. The maximum range is 30 miles. There are two versions of WiMAX. Line-of-sight (LoS) WiMAX uses fixed antennas that point directly at a WiMAX transceiver. Non-LoS WiMAX (currently far more popular) uses base stations that are not visible to the WiMAX tower. As you might imagine, LoS WiMAX is far faster than non-LoS WiMAX.

EXAM TIP Just like LANs and WANs, we also have WLANs and WWANs. A wireless wide area network (WWAN) works similar to a WLAN, except it connects multiple networks like a WAN. WiMAX is an excellent example of a WWAN.

EXAM TIP Just like LANs and WANs, we also have WLANs and WWANs. A wireless wide area network (WWAN) works similar to a WLAN, except it connects multiple networks like a WAN. WiMAX is an excellent example of a WWAN.

Satellite connections to the Internet get the data beamed to a satellite dish on your house or office; a receiver handles the flow of data, eventually sending it through an Ethernet cable to the NIC in your PC. I can already sense people’s eyebrows raising. “Yeah, that’s the download connection. But what about the upload connection?” Very astute, me hearties! The early days of satellite required you to connect via a modem. You would upload at the slow 26- to 48-Kbps modem speed, but then get super-fast downloads from the dish. It worked, so why complain? You really can move to that shack on the side of the Himalayas to write the great Tibetan novel and still have DSL-speed Internet connectivity. Sweet!

Satellite might be the most intriguing of all the technologies used to connect to the Internet today. As with satellite television, though, you need to have the satellite dish point at the satellites (toward the south if you live in the United States). The only significant issue to satellite is that the distance the signal must travel creates a small delay called the satellite latency. This latency is usually unnoticeable unless the signal degrades in foul weather such as rain and snow.

Satellite setup consists of a dish, professionally installed with line-of-sight to the satellite. A coax cable runs from the dish to your satellite modem. The satellite modem has an RJ-45 connection, which you may then connect directly to your computer or to a router.

So you went out and signed up for an Internet connection. Well, now it’s time to get connected. You basically have two choices:

1. Connect a single computer to your Internet connection

2. Connect a network of computers to your Internet connection

Connecting a single computer to the Internet is easy. If you’re using wireless, you connect to the wireless box using the provided information, although a good tech will always go through the proper steps described in Chapter 23 to protect the wireless network. If you choose to go wired, you run a cable from whatever type of box is provided to the PC.

If you want to connect a number of computers using wired connections, you’ll need to grab a router. Several manufacturers offer robust, easy-to-configure routers that enable multiple computers to connect to a single Internet connection. These boxes require very little configuration and provide firewall protection between the primary computer and the Internet, which you’ll learn more about in Chapter 29. All it takes to install one of these routers is simply to plug your computer into any of the LAN ports on the back, and then to plug the cable from your Internet connection into the port labeled Internet or WAN.

There are hundreds of perfectly fine choices for SOHO (small office/home office) routers, but the author’s current favorite is the Cisco E2500 (see Figure 24-25). This little router has four 10/100 Ethernet ports for the LAN computers, and a Wi-Fi radio for any wireless computers you may have. The Cisco E2500, like all home routers, uses a technology called Network Address Translation (NAT). NAT performs a little network subterfuge: It presents an entire LAN of computers to the Internet as a single machine. It effectively hides all of your computers and makes them appear invisible to other computers on the Internet. All anyone on the Internet sees is your public IP address. This is the address your ISP gives you, while all the computers in your LAN use private addresses that are invisible to the world. NAT therefore acts as a firewall, protecting your internal network from probing or malicious users from the outside.

Figure 24-25 Common home router with Wi-Fi

SOHO routers require very little in the way of configuration and in many cases will work perfectly (if incredibly unsafely) right out of the box. In some cases, though, you may have to deal with a more complex network that requires changing the router’s settings. The vast majority of these routers have built-in configuration Web pages that you access by typing the router’s IP address into a browser. The address varies by manufacturer, so check the router’s documentation. If you typed in the correct address, you should then receive a prompt for a user name and password, as in Figure 24-26. As with the IP address, the default user name and password change depending on the model/manufacturer. Once you enter the correct credentials, you will be greeted by the router’s configuration pages (see Figure 24-27). From these pages, you can change any of the router’s settings. Now look at a few of the basic settings that CompTIA wants you to be familiar with.

Figure 24-26 Router asking for user name and password

Figure 24-27 Configuration home page

Changing User Name and Password All routers have a user name and password that gives you access to the configuration screen. One of the first changes you should make to your router after you have it working is to change the user name and password to something other than the default. This is especially important if you have open wireless turned on, which you’ll recall from Chapter 23. If you leave the default user name and password, anyone who has access to your LAN can easily gain access to the router and change its settings. Fortunately, router manufacturers make it easy to change a router’s login credentials. On my E2500, for example, I just click on the Administration tab and fill in the appropriate boxes as shown in Figure 24-28.

Figure 24-28 Changing the password

Setting Static IP Addresses With the user name and password taken care of, let’s look at setting up the router to use a static IP address for the Internet or WAN connection. In most cases, when you plug in the router’s Internet connection, it receives an IP address using DHCP just like any other computer. Of course, this means that your Internet IP address will change from time to time, which can be a bit of a downside. This does not affect most people, but for some home users and businesses, it can present a problem. To solve this problem, most ISPs enable you to order a static IP (for an extra monthly charge). Once your ISP has allocated you a static IP address, you must manually enter it into your router. You do this the same way as the previous change you’ve just looked at. My router has an Internet Setup configuration section where I can enter all the settings that my ISP has provided me (see Figure 24-29). Remember, you must change your connection type from Automatic/DHCP to Static IP to enter the new addresses.

Figure 24-29 Entering a static IP address

Routers are just like any other computer in that they run software—and software has bugs, vulnerabilities, and other issues that sometimes require updating. The router manufacturers call these “firmware updates” and make them available on their Web sites for easy download. To update a modern router, download the latest firmware from the manufacturer’s Web site to your computer. Then you enter the router’s configuration Web page and find the firmware update screen. On my router, it looks like Figure 24-30. From here, just follow the directions and click Upgrade (or your router’s equivalent). A quick word of caution: Unlike a Windows update, a firmware update gone bad can brick your router. In other words, it can destroy the hardware and make it as useful as a brick sitting on your desk. This rarely happens, but you should keep it in mind when doing a firmware update.

Figure 24-30 Firmware update page

Internet Connection Sharing (ICS) enables one system to share its Internet connection with other systems on the network, just like your router at home. Figure 24-31 shows a typical setup for ICS. Note the terminology used here. The PC that connects to the Internet and then shares that connection via ICS with other machines on a LAN is called the ICS host computer. PCs that connect via a LAN to the ICS host computer are simply called client computers.

Figure 24-31 Typical ICS setup

To connect multiple computers to a single ICS host computer requires several things in place. First, the ICS host computer has to have a NIC dedicated to the internal connections. If you connect via dial-up, for example, the ICS host computer uses a modem to connect to the Internet. It also has a NIC that plugs into a switch. Other PCs on the LAN likewise connect to the switch. If you connect via some faster service, such as DSL that uses a NIC cabled to the DSL receiver, you’ll need a second NIC in the ICS host machine to connect to the LAN and the client computers.

Setting up ICS in Windows is very simple. If you are using Windows XP, right-click on My Network Places and select Properties. If you are using Windows Vista or 7, open the Network and Sharing Center and click on Manage network connections (Vista) or Change adapter settings (7) in the Task list. Then access the Properties dialog box of the connection you wish to share.

Click the the Advanced tab (Windows XP) or Sharing tab (Vista and 7) and select Allow other network users to connect through this computer’s Internet connection (see Figure 24-32). Clients don’t need any special configuration but should simply be set to DHCP for their IP address and other configurations.

Figure 24-32 Enabling Internet Connection Sharing in Windows Vista

EXAM TIP Windows XP provides a tool called the Network Setup Wizard that enables you to configure computers on a LAN to share folders and printers. This tool is especially useful on networks that use Internet Connection Sharing with a Windows XP machine as the default gateway.

EXAM TIP Windows XP provides a tool called the Network Setup Wizard that enables you to configure computers on a LAN to share folders and printers. This tool is especially useful on networks that use Internet Connection Sharing with a Windows XP machine as the default gateway.

To run the Wizard, go to Start | Control Panel | Network and Internet Connections | Network Connections. Under Common Tasks, click Network Setup Wizard. Follow the steps in the Wizard to create a floppy disk with a small setup program used to configure other computers to share resources (folders, printers, and so on).

Once you’ve established a connection to the Internet, you need applications to get anything done. If you want to surf the Web, you need an application called a Web browser, such as Mozilla Firefox or Google Chrome. If you want to make a VoIP phone call, you need an application like Skype or Google Voice. These applications in turn use very clearly designed application protocols. All Web browsers use the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). All e-mail clients use Post Office Protocol 3 (POP3) or Internet Message Access Protocol 4 (IMAP4) to receive e-mail. All e-mail applications use Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) to send their e-mails. Every Internet protocol has its own rules and its own port numbers. Though there are tens of thousands of application protocols in existence, lucky for you, CompTIA only wants you to understand the following commonly used application protocols:

• World Wide Web (HTTP and HTTPS)

• E-mail (POP3, IMAP4, and SMTP)

• Telnet

• SSH

• FTP/SFTP

• Remote Desktop (RDP)

• VoIP (SIP)

In addition to the application protocols we see and use daily, there are hundreds, maybe thousands, of application protocols that run behind the scenes, taking care of important jobs to ensure that the application protocols we do see run well. You’ve encountered a number of these hidden application protocols back in Chapter 22. Take DNS. Without DNS, you couldn’t type www.google.com in your Web browser. DHCP is another great example. You don’t see DHCP do its job, but without it, any computers relying on DHCP won’t receive IP addresses.

Here’s another one: People don’t like to send credit card information, home phone numbers, or other personal information over the Web for fear this information might be intercepted by hackers. Fortunately, there are methods for encrypting this information, the most common being Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS). Although HTTPS looks a lot like HTTP from the point of view of a Web browser, HTTPS uses port 443. It’s easy to tell if a Web site is using HTTPS because the Web address starts with https, as shown in Figure 24-33, instead of just http. But you don’t deal with HTTPS directly; it just works in your browser automatically.

Figure 24-33 A secure Web page

In order to differentiate the application protocols you see from the application protocols you don’t see, I’m going to coin the term “utility protocol” to define any of the hidden application protocols. So, using your author’s definition, HTTP is an application protocol and DNS is a utility protocol. All TCP/IP protocols use defined ports, require an application to run, and have special settings unique to that application. You’ll look at several of these services and learn how to configure them. As a quick reference, Table 24-1 lists the names, functions, and port numbers of the application protocols CompTIA would like you to know. Table 24-2 does the same for utility protocols.

Table 24-1 Application Protocol Port Numbers

Table 24-2 Utility Protocol Port Numbers

After you’ve read about these protocols, you’ll learn about Virtual Private Networks and the protocols they use. I’ll also tell you about a few more Internet support utilities that don’t quite fit anywhere else.

The Web provides a graphical face for the Internet. Web servers (servers running specialized software) provide Web sites that you access by using the HTTP protocol on port 80 and thus get more or less useful information. Using Web-browser software, such as Internet Explorer or Mozilla Firefox, you can click a link on a Web page and be instantly transported—not just to some Web server in your home town—to anywhere in the world. Figure 24-34 shows Firefox at the home page of my company’s Web site, www.totalsem.com. Where is the server located? Does it matter? It could be in a closet in my office or in a huge data center in Houston. The great part about the Web is that you can get from here to there and access the information you need with a click or two of the mouse.

Figure 24-34 Mozilla Firefox showing a Web page

Although the Web is the most popular part of the Internet, setting up a Web browser takes almost no effort. As long as the Internet connection is working, Web browsers work automatically. This is not to say you can’t make plenty of custom settings, but the default browser settings work almost every time. If you type in a Web address, such as that of the best search engine on the planet—www.google.com—and it doesn’t work, check the line and your network settings and you’ll figure out where the problem is.

Web browsers are highly configurable. On most Web browsers, you can set the default font size, choose whether to display graphics, and adjust several other settings. Although all Web browsers support these settings, where you go to make these changes varies dramatically. If you are using the popular Internet Explorer that comes with Windows, you will find configuration tools in the Internet Options Control Panel applet or under the Tools menu in Internet Explorer (see Figure 24-35). Note that the applet is called Internet Options, but the window it launches is labeled Internet Properties.

Figure 24-35 Internet Options applet

NOTE The Internet Options Control Panel applet is only for the Internet Explorer Web browser. If you use any other browser (Firefox, Chrome, and so on), Internet Options has no effect.

NOTE The Internet Options Control Panel applet is only for the Internet Explorer Web browser. If you use any other browser (Firefox, Chrome, and so on), Internet Options has no effect.

I find it bizarre that CompTIA specifically lists Internet Options as an objective on the CompTIA A+ 220-802 exam. It’s just so... Microsofty. There are obviously more browsers than just Internet Explorer, so I’ll begin by explaining the options available to you in Internet Explorer, and then show you some of the common options found in other browsers, too.

When you open the Internet Options applet, you’ll see seven tabs along the top. The first tab is the General tab. These settings control the most basic features of Internet Explorer: the home page, your browsing history, searching, and other appearance controls. If you want to delete or change how Internet Explorer stores the Web sites you’ve visited, use this tab.

The Security tab enables you to set how severely Internet Explorer safeguards your Web browsing (see Figure 24-36). Each setting can be adjusted for a particular zone, such as the Internet, your local intranet, trusted sites, and restricted sites. You can configure which Web sites fall into which zones. Once you’ve picked a zone to control, you can set Internet Explorer’s security level. The High security level blocks more Web sites and disables some plug-ins, while Medium-high and Medium allow less-secure Web sites and features to display and operate.

Figure 24-36 The Security tab in Internet Options

The Privacy tab works a lot like the Security tab, except it controls privacy matters, such as cookies and pop-ups. There is a slider that enables you to control what is blocked—everything is blocked on the highest setting; nothing is blocked on the lowest. Go here if you don’t like the idea of Web sites tracking your browsing history (though cookies do other things, too, like authenticate users).

The Content tab also controls what your browser will and will not display. This time, however, it filters content using certificates and a tool called the Content Advisor, which uses ratings that consider language, gambling, substance abuse, and more. The Content tab also enables you to adjust the AutoComplete feature that fills in Web addresses for you, as well as control settings for RSS feeds and Web Slices.

The Connections tab enables you to do a lot of things. You can set up your connection to the Internet, via broadband or dial-up, connect to a VPN, configure a proxy server connection, or adjust some LAN settings (which you probably won’t need to deal with). Because they’re a little complicated, and CompTIA wants you to know about them, let’s quickly talk about proxy servers.

Many corporations use a proxy server to filter employee Internet access, and when you’re on their corporate network, you need to set your proxy settings within the Web browser (and any other Internet software you want to use). A proxy server is software that enables multiple connections to the Internet to go through one protected PC. Applications that want to access Internet resources send requests to the proxy server instead of trying to access the Internet directly, which both protects the client PCs and enables the network administrator to monitor and restrict Internet access. Each application must therefore be configured to use the proxy server.

Moving on, the Programs tab in Internet Options contains settings for your default Web browser, any add-ons you use (like Java), and how other programs deal with HTML files and e-mail messages.

The Advanced tab does exactly what it sounds like: lists a bunch of advanced options that you can turn on and off with the check of a box (see Figure 24-37). The available options include accessibility, browsing, international, and, most importantly, security settings. From here, you can control how Internet Explorer checks Web site certificates, among many other settings.

Figure 24-37 The Advanced tab in Internet Options

I don’t want to stomp all over Internet Explorer and tell you how bad it is—okay, yes I do. You can download several other Web browsers that run faster and support more Web standards. Two of the big browser heavyweights that fit this description are Mozilla Firefox and Google Chrome.

You control their settings just like you do in Internet Explorer, though you won’t find an applet tucked away in Control Panel. In Google Chrome, you can click on the wrench icon in the upper-right corner of the browser and select Settings. In Mozilla Firefox, click on the Firefox button in the upper-left corner and click on Options.

In these menus, you’ll find a lot of settings very similar to the ones you find in Internet Options. In fact, Firefox’s controls are laid out almost exactly the same, though you won’t find everything in the same place (see Figure 24-38). Google Chrome’s controls look more like a Web page, but it still controls the same features: home page, security, font size, cookies, and all your old favorites (see Figure 24-39). Take some time to use these browsers and explore their settings. You’ll be surprised how your knowledge of one browser helps you set up another.

Figure 24-38 Mozilla Firefox options

Figure 24-39 Google Chrome settings

EXAMTIP The term Internet appliance enjoyed some popularity in the 1990s to describe the first wave of consumer devices accessible via TCP/IP. You could use a Web browser to check on the status of an Internet-connected refrigerator, for example, or check to see if you’d left the stove on (and if so, shut it off remotely). Although the term is no longer in use, it might show up on the 220-801 exam.

EXAMTIP The term Internet appliance enjoyed some popularity in the 1990s to describe the first wave of consumer devices accessible via TCP/IP. You could use a Web browser to check on the status of an Internet-connected refrigerator, for example, or check to see if you’d left the stove on (and if so, shut it off remotely). Although the term is no longer in use, it might show up on the 220-801 exam.

You can use a desktop program to access e-mail. The most popular client by far is Microsoft Outlook. E-mail clients need a little more setup. First, you must provide your e-mail address and password. All e-mail addresses come in the now-famous accountname@Internet domain format. Figure 24-40 shows e-mail information entered into the Windows Live Mail account setup wizard.

Figure 24-40 Adding an e-mail account to Windows Live Mail

NOTE Most people use Web-based e-mail, such as Yahoo! Mail or Gmail from Google, to handle all of their e-mail needs. Web-based mail offers the convenience of having access to your e-mail from any Internet-connected computer, smartphone, tablet, or other Internet-connected device. The benefit to using a standalone program is that most offer a lot more control over what you can do with your e-mail, such as flagging messages with different types of flags for later review. Web-based mail services, especially Gmail, are catching up, though, and might surpass traditional e-mail programs in features and popularity.

NOTE Most people use Web-based e-mail, such as Yahoo! Mail or Gmail from Google, to handle all of their e-mail needs. Web-based mail offers the convenience of having access to your e-mail from any Internet-connected computer, smartphone, tablet, or other Internet-connected device. The benefit to using a standalone program is that most offer a lot more control over what you can do with your e-mail, such as flagging messages with different types of flags for later review. Web-based mail services, especially Gmail, are catching up, though, and might surpass traditional e-mail programs in features and popularity.

Next you must add the names of the Post Office Protocol version 3 (POP3) or Internet Message Access Protocol version 4 (IMAP4) server and the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) server. The POP3 or IMAP4 server is the computer that handles incoming (to you) e-mail. POP3 is by far the most widely used standard, although IMAP4 supports some features POP3 doesn’t. For example, IMAP4 enables you to search through messages on the mail server to find specific keywords and select the messages you want to download onto your machine. Even with the advantages of IMAP4 over POP3, the vast majority of incoming mail servers use POP3.

EXAMTIP Make sure you know your port numbers for these e-mail protocols! POP3 uses port 110, IMAP4 uses port 143, and SMTP uses port 25.

EXAMTIP Make sure you know your port numbers for these e-mail protocols! POP3 uses port 110, IMAP4 uses port 143, and SMTP uses port 25.

The SMTP server handles your outgoing e-mail. These two systems may often have the same name, or close to the same name, as shown in Figure 24-41. Your ISP should provide you with all these settings. If not, you should be comfortable knowing what to ask for. If one of these names is incorrect, you will either not get your e-mail or not be able to send e-mail. If an e-mail setup that has been working well for a while suddenly gives you errors, it is likely that either the POP3 or SMTP server is down or that the DNS server has quit working.

Figure 24-41 Adding POP3 and SMTP information in Windows Live Mail

EXAMTIP Microsoft provides a special type of e-mail server called an Exchange server. This is used mainly in large businesses so that employees can access their e-mail, calendars, and instant messages from a variety of locations. To set up an Exchange e-mail client, go to the Control Panel and run the Mail applet. Then click E-mail Accounts and then New. After that, click Next and fill in your e-mail address and password.

EXAMTIP Microsoft provides a special type of e-mail server called an Exchange server. This is used mainly in large businesses so that employees can access their e-mail, calendars, and instant messages from a variety of locations. To set up an Exchange e-mail client, go to the Control Panel and run the Mail applet. Then click E-mail Accounts and then New. After that, click Next and fill in your e-mail address and password.

When I’m given the name of a POP3 or SMTP server, I use ping to determine the IP address for the device, as shown in Figure 24-42. I make a point to write this down. If I ever have a problem getting mail, I’ll go into my SMTP or POP3 settings and type in the IP address (see Figure 24-43). If my mail starts to work, I know the DNS server is not working.

Figure 24-42 Using ping to determine the IP address

Figure 24-43 Entering IP addresses into POP3 and SMTP settings

EXAMTIP Some e-mail servers use SSL encryption for extra security. Every major e-mail client will have a setting called Connection security, or Security, or something like that. If your e-mail server uses encryption, change this setting to SSL.

EXAMTIP Some e-mail servers use SSL encryption for extra security. Every major e-mail client will have a setting called Connection security, or Security, or something like that. If your e-mail server uses encryption, change this setting to SSL.

File transfer protocol (FTP), using ports 20 and 21, is a great way to share files between systems. FTP server software exists for most operating systems, so you can use FTP to transfer data between any two systems regardless of the operating system. To access an FTP site, you must use an FTP client such as FileZilla, although most Web browsers provide at least download support for FTP. Just type in the name of the FTP site. Figure 24-44 shows Firefox accessing ftp.kernel.org.

Figure 24-44 Accessing an FTP site in Firefox

Although you can use a Web browser, all FTP sites require you to log on. Your Web browser will assume that you want to log on as “anonymous.” If you want to log on as a specific user, you have to add your user name to the URL. (Instead of typing ftp://ftp.example.com, you would type ftp://mikem@ftp.example.com.) An anonymous logon works fine for most public FTP sites. Many techs prefer to use third-party programs such as FileZilla (see Figure 24-45) for FTP access because these third-party applications can store user name and password settings. This enables you to access the FTP site more easily later. Keep in mind that FTP was developed during a more trusting time, and that whatever user name and password you send over the network is sent in clear text. Don’t use the same password for an FTP site that you use for your domain logon at the office!

Figure 24-45 The FileZilla FTP program

Telnet is a terminal emulation program for TCP/IP networks that uses port 23 and enables you to connect to a server or fancy router and run commands on that machine as if you were sitting in front of it. This way, you can remotely administer a server and communicate with other servers on your network. As you can imagine, this is rather risky. If you can remotely control a computer, what’s to stop others from doing the same? Of course, Telnet does not allow just anyone to log on and wreak havoc with your network. You must enter a special user name and password to run Telnet. Unfortunately, Telnet shares FTP’s bad habit of sending passwords and user names as clear text, so you should generally use it only within your own LAN.

If you need a remote terminal that works securely across the Internet, you need Secure Shell (SSH). In fact, today SSH has replaced Telnet in almost all places Telnet used to be popular. To the user, SSH works just like Telnet. Behind the scenes, SSH uses port 22, and the entire connection is encrypted, preventing any eavesdroppers from reading your data. SSH has one other trick up its sleeve: it can move files or any type of TCP/IP network traffic through its secure connection. In networking parlance, this is called tunneling, and it is the core of most secure versions of Internet technologies such as SFTP (discussed next) and VPN, which I will discuss in more depth later in the chapter.

EXAMTIP The CompTIA A+ certification exams test your knowledge of a few networking tools, such as Telnet, but only enough to let you support a CompTIA Network+ tech or network administrator. If you need to run Telnet (or its more secure cousin, SSH), you will get the details from a network administrator. Implementation of Telnet falls well beyond CompTIA A+.

EXAMTIP The CompTIA A+ certification exams test your knowledge of a few networking tools, such as Telnet, but only enough to let you support a CompTIA Network+ tech or network administrator. If you need to run Telnet (or its more secure cousin, SSH), you will get the details from a network administrator. Implementation of Telnet falls well beyond CompTIA A+.

Secure FTP is nothing more than FTP running through an SSH tunnel. This can be done in a number of ways. You can, for example, start an SSH session between two computers. Then, through a moderately painful process, start an FTP server on one machine and an FTP client on the other and redirect the input and output of the FTP data to go through the tunnel. You can also get a dedicated SFTP server and client. Figure 24-46 shows OpenSSH, a popular SSH server with a built-in SFTP feature as well.

Figure 24-46 OpenSSH

You can use Voice over IP (VoIP) to make voice calls over your computer network. Why have two sets of wires, one for voice and one for data, going to every desk? Why not just use the extra capacity on the data network for your phone calls? That’s exactly what VoIP does for you. VoIP works with every type of high-speed Internet connection, from DSL to cable to satellite.

VoIP doesn’t refer to a single protocol but rather to a collection of protocols that make phone calls over the data network possible. The most common VoIP application protocol is Session Initiation Protocol (SIP), but some popular VoIP applications like Skype are completely proprietary.

Venders such as Skype, Cisco, Vonage, and Comcast offer popular VoIP solutions, and many corporations use VoIP for their internal phone networks. A key to remember when installing and troubleshooting VoIP is that low network latency is more important than high network speed. Latency is the amount of time a packet takes to get to its destination and is measured in milliseconds. The higher the latency, the more problems, such as noticeable delays during a VoIP call.

VoIP isn’t confined to your computer, either. It can completely replace your old copper phone line. Two popular ways to set up a VoIP system are to either use dedicated VoIP phones, like the ones that Cisco makes, or use a small VoIP phone adapter (see Figure 24-47) that can interface with your existing analog phones.

Figure 24-47 Vonage Box VoIP phone adapter

True VoIP phones have RJ-45 connections that plug directly into the network and offer advanced features such as HD-quality audio and video calling. Unfortunately, these phones require a complex and expensive network to function, which puts them out of reach of most home users.

For home users, it’s much more common to use a VoIP phone adapter to connect your old-school analog phones. These little boxes are very simple to set up: just connect it to your network, plug in a phone, and then check for a dial tone. With the VoIP service provided by cable companies, the adapter is often built right into the cable modem itself, making setup a breeze.

In Microsoft networking, we primarily share folders and printers. At times, it would be convenient to be “transported” to another computer—to feel as if your hands were actually on its keyboard. There are plenty of programs that do exactly this, generically called remote desktops.

Like so many other Windows applications, remote desktops originally came from third-party companies. Microsoft bought the companies and absorbed their code into the Windows operating system. Many third-party remote desktop applications are available. One of the most popular is TightVNC. TightVNC is totally cross-platform, enabling you to run and control a Windows system remotely from your Mac or vice versa, for example. Figure 24-48 shows TightVNC in action.

Figure 24-48 TightVNC in action

NOTE All terminal emulation programs require separate server and client programs.

NOTE All terminal emulation programs require separate server and client programs.

Windows offers an alternative to VNC: Remote Desktop. Remote Desktop provides control over a remote server with a fully graphical interface. Your desktop becomes the server desktop (see Figure 24-49).

Figure 24-49 Windows Remote Desktop Connection dialog box

NOTE The name of the Remote Desktop executable file is mstsc.exe. You can also open Remote Desktop from a command-line interface by typing mstsc and pressing ENTER.

NOTE The name of the Remote Desktop executable file is mstsc.exe. You can also open Remote Desktop from a command-line interface by typing mstsc and pressing ENTER.

Wouldn’t it be cool if, when called about a technical support issue, you could simply see what the client sees? (I’m not talking voyeur cam, here.) When the client says that something doesn’t work, it would be great if you could transfer yourself from your desk to your client’s desk to see precisely what the client sees. This would dramatically cut down on the miscommunication that can make a tech’s life so tedious. Windows Remote Assistance does just that. Remote Assistance enables you to give anyone control of your desktop. If a user has a problem, that user can request support directly from you. Upon receiving the support-request e-mail, you can then log on to the user’s system and, with permission, take the driver’s seat. Figure 24-50 shows Remote Assistance in action.

Figure 24-50 Remote Assistance in action

With Remote Assistance, you can do anything you would do from the actual computer. You can troubleshoot some hardware configuration or driver problem. You can install drivers, roll back drivers, download new ones, and so forth. You’re in command of the remote machine as long as the client allows you to be. The client sees everything you do, by the way, and can stop you cold if you get out of line or do something that makes the client nervous! Remote Assistance can help you teach someone how to use a particular application. You can log on to a user’s PC and fire up Outlook, for example, and then walk through the steps to configure it while the user watches. The user can then take over the machine and walk through the steps while you watch, chatting with one another the whole time. Sweet!

Remote desktop applications provide everything you need to access one system from another. They are common, especially now that Microsoft provides Remote Desktop for free. Whichever application you use, remember that you will always need both a server and a client program. The server goes on the system you want to access and the client goes on the system you use to access the server. On many solutions, the server and client software are integrated into a single product.

In Windows, you can turn Remote Assistance and Remote Desktop on and off and configure other settings. Go to the System Control Panel applet. In Windows XP, click on the Remote tab. In Windows Vista and Windows 7, click Remote settings. You will see checkboxes for both Remote Assistance and Remote Desktop, along with buttons to configure more detailed settings. (In Windows XP, you’ll only see Remote Desktop controls if you installed the Remote Desktop client, which is not installed by default.)

EXAM TIP Windows 7 (and Windows Vista with the appropriate update) is capable of running specific applications hosted on a Windows Server 2008/2008 R2 machine. Think of it as Remote Desktop without the desktop—a single application run on one machine (a server) and appearing on another desktop (a client). You can set up your connection to the Windows Server machine using the RemoteApp and Desktop Connections applet in Control Panel.

EXAM TIP Windows 7 (and Windows Vista with the appropriate update) is capable of running specific applications hosted on a Windows Server 2008/2008 R2 machine. Think of it as Remote Desktop without the desktop—a single application run on one machine (a server) and appearing on another desktop (a client). You can set up your connection to the Windows Server machine using the RemoteApp and Desktop Connections applet in Control Panel.

Remote connections have been around for a long time, long before the Internet existed. The biggest drawback about remote connections was the cost to connect. If you were on one side of the continent and had to connect to your LAN on the other side of the continent, the only connection option was a telephone. Or, if you needed to connect two LANs across the continent, you ended up paying outrageous monthly charges for a private connection. The introduction of the Internet gave people wishing to connect to their home networks a very cheap connection option, but with one problem: the whole Internet is open to the public. People wanted to stop using dial-up and expensive private connections and use the Internet instead, but they wanted to do it securely.

Those clever network engineers worked long and hard and came up with several solutions to this problem. Standards have been created that use encrypted tunnels between a computer (or a remote network) to create a private network through the Internet (see Figure 24-51), resulting in what is called a Virtual Private Network (VPN).

Figure 24-51 VPN connecting computers across the United States

An encrypted tunnel requires endpoints—the ends of the tunnel where the data is encrypted and decrypted. In the SSH tunnel you’ve seen thus far, the client for the application sits on one end and the server sits on the other. VPNs do the same thing. Either some software running on a computer or, in some cases, a dedicated box must act as an endpoint for a VPN (see Figure 24-52).

Figure 24-52 Typical tunnel

To make VPNs work requires a protocol that uses one of the many tunneling protocols available and adds the capability to ask for an IP address from a local DHCP server to give the tunnel an IP address that matches the subnet of the local LAN. The connection keeps the IP address to connect to the Internet, but the tunnel endpoints must act like NICs (see Figure 24-53). Let’s look at one of the protocols, PPTP.

Figure 24-53 Endpoints must have their own IP addresses.

So how do we make IP addresses appear out of thin air? Microsoft got the ball rolling with the Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP), an advanced version of a protocol used for dial-up Internet called PPP that handles all of this right out of the box. The only trick is the endpoints. In Microsoft’s view, a VPN is intended for individual clients (think employees on the road) to connect back to the office network, so Microsoft places the PPTP endpoints on the client and a special remote access server program called Routing and Remote Access Service (RRAS), available on Server versions of Windows, on the server (see Figure 24-54).

Figure 24-54 RRAS in action

On the Windows client side, you right-click on My Network Places and click on Create a New Connection (Windows XP) or type VPN into the Start Search bar (Windows Vista and 7) and press ENTER. This presents you with a dialog box where you can enter all your VPN server information. Your network administrator will most likely provide this to you. The result is a virtual network card that, like any other NIC, gets an IP address from the DHCP server back at the office (see Figure 24-55).

Figure 24-55 VPN connection in Windows

EXAM TIP A system connected to a VPN looks as though it’s on the local network but often performs much slower than if the system were connected directly back at the office.

EXAM TIP A system connected to a VPN looks as though it’s on the local network but often performs much slower than if the system were connected directly back at the office.

When your computer connects to the RRAS server on the private network, PPTP creates a secure tunnel through the Internet back to the private LAN. Your client takes on an IP address of that network, as if your computer were plugged into the LAN back at the office. Even your Internet traffic will go through your office first. If you open your Web browser, your client will go across the Internet to the office LAN and then use the LAN’s Internet connection! Because of this, Web browsing is very slow over a VPN.

The CompTIA A+ 220-801 objectives list three rather unique protocols. Personally, I doubt you’ll ever deal directly with two of them, and the other is more common to LANs, not the Internet, but you should know a little bit about all three anyway.

The Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) enables operating systems and applications to access directories. If you’ve got a Windows Server system running Active Directory, for example, Windows uses LDAP to do anything with Active Directory. If you’re sitting at a computer and add it to an Active Directory domain, Windows uses LDAP commands to update the Active Directory with the computer’s information. You don’t see LDAP, but it works hard to keep networks running smoothly.

The Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) enables remote query and remote configuration of just about anything on a network. Assuming all your computers, switches, routers, and so on are SNMP-capable, you can use programs to query the network for an unimaginable amount of data. SNMP is a popular tool to check on your network, but you’ll need to take the CompTIA Network+ exam to see SNMP in action.

The Server Message Block (SMB) protocol isn’t even an application but rather proof of the power of Microsoft. SMBs date back to the old NetBIOS naming service and were the tools that tossed a PC’s name around a network. NetBIOS names are gone, but SMBs are the reason that tools like Network can show you all the computers on your network. SMB is so powerful that other operating systems copy SMB using a popular program called SAMBA. SAMBA emulates SMB—it makes non-SMB operating systems on a network look like Windows.

There isn’t a person who’s spent more than a few hours on a computer connected to the Internet who hasn’t run into some form of connectivity problem. I love it when I get a call from someone saying “The Internet is down!” as I always respond the same way: “No, the Internet is fine. It’s the way you’re trying to get to it that’s down.” Okay, so I don’t make a lot of friends with that remark, but it’s actually a really good reminder of why we run into problems on the Internet. Let’s review the common symptoms CompTIA lists on their objectives for the CompTIA A+ 220-802 exam and see what we can do to fix these all-too-common problems.

The dominant Internet setup for a SOHO environment consists of some box from your ISP—a cable modem, a DSL modem, etc.—that connects via Ethernet cable to a home router. This router is usually 802.11 capable and includes four Ethernet ports. Some computers in the network connect through a wire and some connect wirelessly (see Figure 24-56). It’s a pretty safe assumption that CompTIA has a setup like this in mind when talking about Internet troubleshooting, and we’ll refer to this setup here as well.

Figure 24-56 Typical SOHO setup

One quick note before we dive in—most Internet connection problems are network connection problems. In other words, everything you learned in Chapter 22 still applies here. We’re not going to rehash those repair problems in this chapter. The following issues are Internet-only problems, so don’t let a bad cable fool you into thinking a bigger problem is taking place.

As you’ll remember from Chapter 22, “no connectivity” has two meanings: a disconnected NIC or an inability to connect to a resource. Since Chapter 22 already covers wired connectivity issues and Chapter 23 covers wireless issues, let’s look at lack of connectivity from a “you’re on the Internet but you can’t get to a Web site” point of view:

1. Can you get to other Web sites? If not, go back and triple-check your local connectivity.

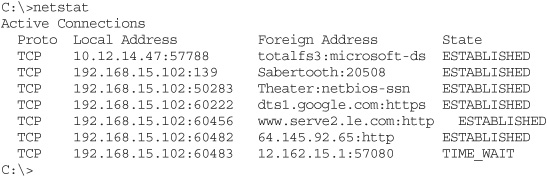

2. Can you ping the site? Go to a command prompt and try pinging the URL as shown here:

The ping is a failure, but we learn a lot from it. The ping shows that your computer can’t get an IP address for that Web site. This points to a DNS failure, a very common problem. To fix a failing DNS:

1. Go to a command prompt and type ipconfig /flushdns:

2. If you have Windows XP, go to the Network Connections applet in the Control Panel. Right-click on your network connection and select Repair. If you have Windows Vista/7, go to the Network and Sharing Center and click Change adapter settings. Right-click on your network connection and select Diagnose to run the troubleshooter (see Figure 24-57).

3. Try using another DNS server. There are lots of DNS servers out there that are open to the public. Try Google’s famous 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4.

If DNS is OK, make sure you’re using the right URL. This is especially true when you’re entering DNS names into applications like e-mail clients.

Figure 24-57 Diagnosing a network problem in Windows 7

Limited connectivity points to a DHCP problem, assuming you’re connected to a DHCP server. Run ipconfig and see if you have an APIPA address:

Uh-oh! No DHCP server! If your router is your DHCP server, try restarting the router. If you know the Network ID for your network and the IP address for your default gateway (something you should know—it’s your network!), try setting up your NIC statically.

Local connectivity means you can access network resources but not the Internet. First, this is a classic symptom of a downed DHCP server since all the systems in the local network will have APIPA addresses. However, you might also have a problem with your router. In Windows XP, you need to ping the default gateway; if that’s successful, ping the other port (the WAN port) on your router. The only way to determine the IP address of the other port on your router is to access the router’s configuration Web page and find it (see Figure 24-58). Every router is different—good luck!

Figure 24-58 Router’s WAN IP address