Level 1 Triangles

Atriangle is an unhealthy relationship among three people. Whenever the pain of a two-person relationship becomes unbearable, one or both of them may bring in and involve a third person, place or thing to help relieve their pain. This forms a triangle, as shown in Figure 5.1. Healthy boundaries help prevent involvement in unhealthy triangles and their painful consequences.

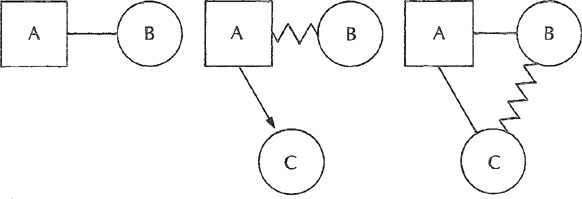

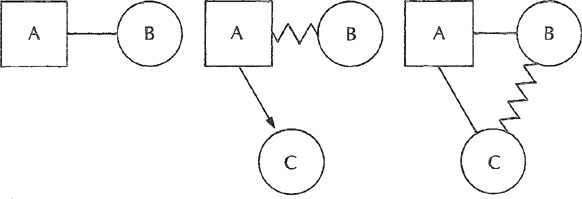

Figure 5.1 Common Dynamics in the Formation of a Triangle

Source: From Kerr and Bowen, 1988.

The left diagram in Figure 5.1 shows a calm relationship in which neither person is sufficiently uncomfortable to triangle-in a third person, place or thing. The center illustrates the occurrence of conflict and unbearable pain. The more uncomfortable person, A, who also may be the less recovered or self-actualized, triangles a third person, C, into the conflict. The right diagram shows that as a result a substantial amount of conflict and pain has transferred mostly out of the original twosome and into the relationship between B and C.

An example: Mother, father and child are relatively calm. If mother and father have a conflict they cannot resolve, one of them may involve the child in such a way that their conflict and pain is transferred to an interaction between the other two. (Involving the child in this way may also occur with the participation of both parents, usually through unconscious collusion.) Similar to what happens in projective identification,22 where one person avoids owning and dealing with their own inner life material, the formed triangle takes away the responsibility that the mother and father could take upon themselves to work through their conflict. This original conflict did not belong to the child. Yet by forming the triangle the parents are teaching their child unhealthy boundaries by modeling them. And they are wounding the child by forcing him or her to take on what is not the child’s.

Mary, a thirty-five-year-old stay-at-home mother with three young children saw me (CW) several times in individual therapy before asking her husband to join us. Her presenting complaints included low self-esteem, anxiety and an inability to get along with her children, especially the middle child who was a nine-year-old boy. They also had a daughter eleven and a son five.

Mary’s husband refused to come at first and then agreed when we decided to make this a family session and invited the children. He arrived with their eleven-year-old daughter, and Mary came with their two sons. The daughter and father shared a two-seat sofa while the others took individual chairs. During the session conflict arose between Mary and the nine-year-old son. This held our attention through most of the session, and when I tried to move us on, the attention always came back to Mary and this one son. A few moments before the session was over, her husband stood up (and the daughter stood immediately upon seeing her father stand) and announced that none of this had anything to do with him, and the two of them walked out. Mary had several more sessions with me before realizing that her main conflict was with her husband, who had triangled her children into their numerous and painful differences. He chose not to engage her in working through their conflicts with or without triangling in one or more of their children. As an individual, Mary learned through individual and group therapy to de-triangle—she learned to take the conflict away from her children, allowing them to be children—and to look more closely at her strained relationship with her husband. Nine years later with the two older children away at college, she observed her husband triangling in their youngest child. Unable to stop the toxic triangle and feeling stronger, she divorced her husband. She now reports a healthier relationship with all three children and herself, including now having a higher self-esteem and lessening of her anxiety. In retrospect, she chose to let go of her need to be right and opened to trusting God, both of which are key characteristics of humility.

By contrast, in a healthy family, mother and father resolve their own conflict between themselves, even though they each may have to tolerate for a while the emotional pain that goes with it. By doing so, they model and teach their child healthy boundaries and, when appropriate, explain what may be happening should the child appear concerned.

The concept of triangles is old: “Three is a crowd.” They exist in all families and in all human relationships. The only question is the number, intensity and composition of the triangles in one’s life.

In recovery, which includes learning to set healthy boundaries, we can gradually discover how to identify and disengage from—and sometimes even avoid getting involved in—triangles. And the more recovered, self-actualized or differentiated each of the three people in an old triangle may become, the greater the chance that they may even be able to change it into a healthier threesome and move up to the Level 2 triangle, which we will discuss in later chapters.

Let us begin to look at the characteristics of people who can begin to move away from conflict and up into the Level 2 triangle.

A “threesome” is the interaction of three healthy two-way relationships (see Table 5.1). Each member functions from their True Self, and thus with authenticity and spontaneity. While it is an open system with flexible movement among the three people, there is closeness or even intimacy experienced between each of the three pairs. The awareness of their own inner lives (Figure 5.2) by each member generally tends to be high, and boundaries are generally healthy. In fact, it is the healthy boundaries that assist in keeping the threesome intact, in part because they help keep the twosomes intact.

Table 5.1 Triangle and Threesome: Some Differentiating Characteristics

Characteristic |

Threesome |

Triangle |

Condition |

Healthy |

Unhealthy |

Definition |

Three healthy two-way relationships |

An unhealthy three-way relationship |

Awareness of Our Inner Life by Each Member |

High awareness |

Low to absent awareness |

Consciousness of Each Member |

Mostly True Self |

Mostly false self |

System |

Open |

Closed |

Spontaneity |

Mostly present |

Usually absent |

Movement |

Flexible |

Fixed, rigid or reciprocal |

Interaction |

Closeness |

Fusion |

Boundaries |

Healthy |

Unhealthy |

Most triangles cannot be transformed into a threesome because it is unusual for each of the three members of the triangle to work through a process of recovery to a sufficient degree at around the same time. In this book, we will share ways of doing this. If only one or two of the three are willing to do this work, the frequency of triangular interactions and their detrimental consequences may decrease remarkably.

A triangle is thus an unhealthy three-way relationship. Each member functions mostly from their false self, with little spontaneity. It tends to be a closed system with fixed, rigid or reciprocal movement. While there may superficially appear to be closeness among the members, there is actually usually only fusion, wherein one person overlaps another so that there is an indistinctness of self-identification or self-differentiation (see Figure 5.3). What overlaps are usually aspects of the two people’s inner life and behavior. It is difficult to tell what is self and what is the other person, and it is difficult to tell where self ends and the other begins. We usually learn fusion (also called enmeshment) experientially in our family of origin.23

Figure 5.3 The Parents Enmesh the Children

Source: Drawing from P. Morand, et al: The art of Romaine Brooks, 1967.

Seeking the impossible goal of completeness and fulfillment through another person, place or thing, any of the following can occur:

• One person may try to merge into the other, in an all-or-none fashion, to gain self-realization. (I am right and you are wrong, or you are right and I am wrong.)

• Two people may try to merge into one. (We always agree.)

• One person may lose themself in the other person. (I live for only you.)

• One person may usually pursue and the other usually distance, with little or no mutuality in their relationship.

When they get into conflict and the emotional tension gets too high for either to deal with, one or both of them may triangle-in a third person to lessen the tension. In a triangle the awareness of their own inner life by each member tends to be low to absent, and the unhealthy boundaries prevent the autonomy and individuation required to avoid the triangle, and they promote and maintain fusion. Each person doesn’t have a realized True Self from which to be aware and to act appropriately, in part because they have no healthy boundaries to maintain the integrity of their True Self when it emerges.

The purpose of a triangle is to stabilize the two-person system when it is in danger of disintegrating. If two people can get interested in or distracted by a third person, object, issue or fantasy, they can avoid facing the real, threatening or scary issues between them. Ultimately, the triangle helps us avoid changing ourselves and our part of the problem. By contrast, two people sharing in common interest or activity in a healthy way or working through a conflict can nourish and enrich their relationship.

Triangles are learned both inside and outside our family of origin. They are a product of how wounded and unrecovered or undifferentiated its members are. The more unrecovered the people are, the more important is the role of triangling for preserving emotional stability in a particular group of people. If there is relative calm, even in a family with very wounded and undifferentiated people, the three members of a triangle may function for a time as emotionally separate individuals. Because change and stress trigger fear and other painful feelings, an increase in these will tend to reactivate the dynamics of the triangle. In a well-differentiated system, such as a threesome, the members can maintain their emotional separateness and autonomy even when they are highly stressed. If people can maintain their emotional autonomy, functioning as their True Self with healthy boundaries, triangling is minimal, and the system’s stability does not depend on it.

Triangles are not simple mechanical events, but are often complex interactions that have both personal (intrapsychic) and relationship (systemic) origins, dynamics, experiences and meanings. For example, the stability of any twosome can vary just by adding or taking away a third person, depending upon whether the relationship is stable or unstable at the time (see Table 5.2). These examples illustrate the many potential guises by which triangles may present themselves in stable and unstable relationships. Note, however, that here “stable” does not necessarily mean healthy, nor does “unstable” always mean unhealthy. Note also that a fused or enmeshed relationship may destabilize at any time, because it is not usually made up of two recovered or individuated people having a healthy relationship.

Table 5.2 The Stability of a Relationship May Vary by Adding or Removing a Third Person

If the Twosome Is: |

It Can Be Destabilized By: |

Example: |

Stable |

Adding a third person |

Birth of a child in a harmonious marriage. |

|

Removing a third person |

No longer able to triangle their child, parents fight more after child leaves home. |

Unstable |

Adding a third person |

Birth of a child into a conflicted marriage. |

|

Removing a third person |

Two people avoid a person who takes sides on issues in their relationship, which foments conflict by emotionally polarizing the couple. |

Source: Compiled from Kerr and Bowen, 1988

Other ways that triangles may show their complexity are by their symptoms, which frequently are also their consequences. These may include:

1. The original, unresolved conflict and pain that wounds people and thus predisposes them to be involved in triangles. Without realizing and living from and as our True Self—with healthy boundaries to protect and maintain its integrity—it will be difficult to avoid being involved in triangles to such a degree. This woundedness usually comes from growing up in a dysfunctional family and society, where triangles are universal. Most people grow up learning triangles, not healthy twosomes and threesomes.

2. A lost, hurting self then results from that original wounding. This can be manifested by recurring illness in any one or more of the physical, mental, emotional24 and spiritual realms25 of our lives. Because our True Self is in hiding to survive, we come to rely upon our false self to run our lives. Not living from and as our True Self, we are left with the whims of our false self, which thrives on dysfunctional relationships, including regular involvement in triangles.

3. Unhealthy boundaries are both a basis for and a manifestation of being involved in triangles. Without boundaries and limits we cannot protect and maintain our True Self that keeps us in healthy relationships and out of unhealthy ones, including triangles.

4. Inner and outer confusion, pain and chaos, usually with some interim periods of numbness and sometimes calm. A reduction in the frequency and intensity of this chaos and pain, as well as improved functioning in relationships—all of which feels better—results from working through the long process of recovery.

5. Repetition compulsions may also be a symptom and consequence of being involved in triangles. In fact, regular involvement in triangles is itself a kind of repetition compulsion. Repetition compulsions are making the same mistake over and over.

6. Scapegoating is identifying one person, place or thing in the triangle as being the victim or the problem. Underneath we can see that all three members are at the same time victim, problem and potential solution. As family therapist Tom Fogarty describes, “Father and mother may avoid marital strife by focusing on their son. That is one part of a triangle. Son and mother avoid facing the difficulties in their over-closeness by having a common enemy—father. Father and son avoid dealing with their distance by relating to each other indirectly through mother. There is no victimizer or victim here. . . . All members of this triangle participate equally in perpetuating the triangle and no triangle can persist without the active cooperation of its members.”26

However, given two wounded and dysfunctional parents, the young child cannot inherently protect itself against their damage and come out unscathed. By triangling in their child, the parents invade its boundaries and damage its True Self, thereby wounding the child. In later life the child, now adult, can heal his or her wounds by taking responsibility for his or her own recovery, in part by knowing these dynamics and then experientially working through and grieving the pain that they produced.

7. Avoidance of closeness and intimacy in relationships where these would be appropriate is both a cause and a result of triangles. We can use healthy boundaries to help avoid triangles, so we can focus on our wants and needs from our own inner life as we interact with our partners. Doing so promotes closeness and intimacy.

8. Other symptoms and consequences, including the creating of interlocking triangles, which we describe after Bobbi’s story.

Bobbi became the sixth member of our women’s psychotherapy group that had been working together successfully for quite some time. This particular group was an example of empathy growing into unconditional love for one another and ourselves. After observing for two or three sessions, Bobbi shared with the group her inability to trust women. As a child she watched her mother and her mother’s two sisters argue all the time. Her mother than “pitted” her and her brother against each other. She remembers always being in the middle when her parents were together—usually they ignored each other, only tending to Bobbi’s needs. Now Bobbi says she can’t hold a job for very long because she winds up getting involved in the office politics. Because she is the last one to be hired, when the tension in the office “blows up,” she gets the blame, and feels like a victim.

Over time, we watched the group struggle with some negativity that Bobbi named and complained about first. The group couldn’t identify it until one member finally brought up the gossip and laughter going on in the parking lot before and after group. When the group explored these loud and sometimes insulting moments, they reminisced about how unconditionally loving and empathetic the group had been until lately. Over time one member after another gently confronted Bobbi with something hostile she had said either outside group in the parking lot or inside before group had begun. There was no malice during these gentle confrontations. As a persecutor, Bobbi tried to blame the group, saying that she “could never get along with women,” and this was a “perfect example of the persecution” she had endured. Her attitude was, “Either I’m right—or you’re right. And I trust myself, but not you!” After several weeks of this, Bobbi slumped in her chair upon hearing the same comments from the group and said, “I’m doing what my mother did. I’ve had a good teacher.” For a moment Bobbi let herself open to more possibilities than her controlling ego would have previously allowed. She worked on her need to control, which she said came from all the pain she absorbed in her childhood. She realized that learning more about herself (through humility) was her way out. We watched her take responsibility for some of the chaos in her life. And, as she struggled with her pain, she also explored more and more avenues for helping herself recover.

Interlocking triangles occur when the pain of one triangle, unable to be contained, overflows into one or more other triangles. In a calm family, one central triangle can for a while contain most of its emotional pain. But under stress, this pain spreads to other family triangles and to triangles outside the family in the person’s work and society. This process is illustrated in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4 Example of a Family Triangle

Diagram of a Family: with a father, mother, older daughter and younger son. A: all the triangles are fairly inactive. B: tension develops between mother and son. C: father becomes triangled into the tension between mother and son. D: tension shifts to the father and son relationship. E. mother withdraws and the original triangle becomes inactive. Meanwhile the daughter is triangled into the father-son tension. F: conflict erupts between the two siblings. So tension originally present in one triangle is acted out in another triangle.

Modified from Kerr and Bowen, 1988

In addition to the roles of scapegoat and victim already mentioned, members of a triangle often have rigid roles that create the triangle, maintain it and keep them locked into it. For example, some members may, by their behavior, tend to generate emotional pain in themselves and the others, and can be called pain generators. These generators, or persecutors, set the emotional tone of many of the members, may upset people and may be the first to get upset about potential problems, although they may not be the cause of that pain (see “Bobbi’s Story”).

A second role is that of pain amplifiers, who add to the problem through their inability to stay calm and stay out of the conflict if it doesn’t belong to them. A third role is that of the dampeners who use emotional distance to control their reactivity to the others’ behaviors. Under higher stress, people in this role become overly responsible for others in order to calm things down. While dampeners may on the surface reduce some of the symptoms and consequences, they reinforce the creation and maintenance of the triangle. We can also call this role the rescuer.

Other roles may also influence the dynamics of the triangle. These include the role of the abuser, which, like the pain generator, or persecutor, is one of the most intimidating and dysfunctional roles. Another is the enabler, who unconsciously—and sometimes consciously—facilitates the destructive behavior of a dysfunctional person. This facilitating may include repeated attempts to rescue or fix the dysfunctional person. Still other roles are those described by authors and clinicians Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse and Claudia Black: the family hero (responsible or successful one), the lost child (the adjuster or quiet one), and the family mascot or pet (little princess, Daddy’s little girl or Momma’s boy). Each of these roles may add their own dysfunctional aspects to the rigid and stereotypical behavior of any member of a triangle.

Because most people who are regularly involved in triangles tend to fit the description of being actively co-dependent, a member of a triangle may also play any of the roles that we described as guises of unhealthy dependence. In addition to some of the roles mentioned, these guises may include: people-pleaser, overachiever, inadequate one or failure, perfectionist, victim, martyr, addicted, compulsive, grandiose and selfish or narcissistic one.

Donna checked in every week at her psychotherapy group with short reports on a conflict she was having with a close girlfriend of hers. Finally, she asked for time to work on the growing pain she was feeling. Her friend Sally had a new boyfriend who seemed to be a model date. Sally had repeated “bad luck” with boyfriends who always wound up emotionally and psychologically abusing her. This man talked to her during the week with e-mails, and then they saw each other on weekends. Sally forwarded every e-mail to Donna to get her opinion of what he was writing that was wrong. When Donna told the group about this, they validated her opinion that the boyfriend wasn’t saying anything wrong in the e-mails and sounded like a nice man. Donna went back to Sally and told her that her friend was not doing anything to hurt her and that her emotional upheaval over his letters was unfounded. Donna reported at the next group that Sally then turned on her and told Donna in an angry and attacking tone that she was part of the problem. Donna worked on her past pain with women, especially her mother and several girlfriends who frequently triangled her into other conflicts they were having. She realized that she had taken on the tension that belonged with the other two people. Instead of Sally dealing directly with her conflict with her new boyfriend, she had transferred that painful conflict (from her past) onto Donna. Sally was seeing her new boyfriend free of tension because she had found a third person who would take it.

Donna told Sally she needed a few weeks to sort out what had happened between them. Doing so gave her more time to process her feelings, wants and needs regarding their conflict by setting a healthy boundary. Then she sat down with Sally with the hope of talking it all out. Donna told the group, “I realized an hour into the superficial banter that there was no way Sally could or would talk about it. So I have removed myself from this triangle by removing myself from the degree of investment that I previously had in the friendship.”

Each of the various roles, guises and traits can bring different aspects to the behavior of a member of a triangle. In recovery, a person may draw upon any of these less desirable traits as they transform them into healthier ones. For example, martyrs or victims can learn to be more sensitive to their inner life and take responsibility for making their life a success, which would include learning to set healthy boundaries. An example from Donna’s story is the boundary she set first by putting time and space between them and then by not pitying or feeling sorry for Sally, which would have kept both of them in conflict.

With any three people, one triangle is possible. Add but one more person, and now there are four potential triangles. Add another for a total of five people, and there are ten. By all of the above examples and dynamics in this chapter, we can begin to see how common, pervasive, contagious and destructive triangles may be. Is there a way out?