55 grams of carbohydrate

Now you’re in on the secret: Many of us are damaging our health by eating too many foods that send our blood sugar soaring. Besides contributing to diabetes and other serious illnesses over the long haul, meals loaded with these foods also leave you tired, grumpy, and hungry again in no time after you eat them. Other foods barely move the blood sugar needle or move it gradually, keeping you feeling full and energized.

Unfortunately, foods don’t come with labels explaining which is which. After reading this chapter, though, you’ll know how to tell the difference.

In the end, it’s as simple as choosing pasta over rice, baked beans instead of mashed potatoes, oil-and-vinegar dressing instead of Thousand Island, and other easy fixes. Read on to discover what makes these foods Magic.

The glycemic load —a powerful tool in your arsenal of weapons against high blood sugars.

First, we’ll talk about the three so-called macronutrients in food—carbohydrate, fat, and protein—from which we get almost all of our calories, and we’ll tell you how they affect your blood sugar. Then we’ll talk about two “magic” food components you can use for amazingly effective blood sugar control: soluble fiber and acetic acid, found in sour foods.

We’ll reveal the main plot twist right now: Carbohydrates are the foods that raise blood sugar. Plain and simple, right? The trouble is, not all carb foods are created equal.

Carbohydrates are actually found in most foods except fats and oils, meats, poultry, and fish. But of course, some foods contain more carbs than others. Beans are about one-fourth protein and three-fourths carbohydrate. Rice, on the other hand, is more than 90 percent carbohydrate. Whole milk contains all three macronutrients: fat, protein, and carbohydrate.

It’s the quantity of carbohydrate in foods (and of course, how much of the food you eat) that primarily affects blood sugar, but the type of carbohydrate also has an effect.

To figure out which carbs are best and worst for blood sugar, scientists had to do some serious detective work. First, they needed to come up with a way to measure a food’s effect on blood sugar.

Nutrition scientist David Jenkins, M.D., Ph.D., developed a system called the glycemic index (GI) back in 1981 (the prefix glyc- means “sugar”). He had volunteers eat different foods, all containing 50 grams of carbohydrate. Then he measured the volunteers’ blood sugar over the following 2 hours to see how high it went. As a control he used pure glucose, the form of sugar that’s identical to blood sugar—your body converts glucose very quickly to blood sugar—and assigned it the number 100 on his new index.

The glycemic index opened a lot of eyes. Almost everyone had assumed that table sugar would be the worst offender, much worse than the “complex carbohydrates” found in starchy staples such as rice and bread. But this didn’t always prove true. Some starchy foods, like potatoes and cornflakes, ranked very high on the index, raising blood sugar nearly as much as pure glucose. That’s why you won’t see these foods in our list of Magic foods.

The higher the glycemic load in the diet, the greater the incidence of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

Something was wrong, however. Some of the results pointed fingers at healthy foods, such as carrots and strawberries. Watermelon was just about off the top of the GI chart. But no one ever gained weight from eating carrots, nor do carrots, in the real world, raise blood sugar. What was the GI missing?

The GI measured the effects of a standard amount of carbohydrate: 50 grams, or about 1 1/2 ounces. But you’d be awfully hard-pressed to eat enough carrots—seven or eight large ones—to get 50 grams of carbohydrate. The same holds true for most other vegetables and fruits. They’re full of water, so there’s not much room in them for carbohydrate. Bread, on the other hand, is crammed with carbohydrate. You get 50 grams by eating just one slice.

To solve the problem, scientists came up with a different measurement: the glycemic load (GL). It takes into account not only the type of carbohydrate in the food but also the amount of carbohydrate you would eat in a standard serving. (To get a bit technical, a food’s GL is the GI multiplied by the amount of carbohydrate in one serving.)

This made more sense. By this criterion, carrots, strawberries, and other low-calorie foods are clearly good to eat—they all have low GL values, since the amount of carbohydrate they contain is low.

The GL has turned out to be a powerful way to think about not just individual foods but also whole meals and even entire diets. When scientists looked at the GL of typical diets in different populations, they found that the higher the GL, the greater the incidence of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. You may remember a study we mentioned in Chapter 1 in which men who ate the most sugar-boosting foods were 40 percent more likely to get diabetes. That’s GL we were talking about. We also talked about the Nurses’ Health Study finding that women were twice as likely to develop heart disease over 10 years if they ate more sugar-boosting foods. Again, the GL. The converse is also true: The lower the GL of your diet, the more likely you are to keep your weight under control and stay free of chronic disease.

When it comes to eating right, controlling weight, and preventing disease, the GL is a heavy hitter. It can be a more powerful factor in keeping you healthy than just the amount of carbohydrates you eat.

Why would one high-carb food have a different GL than another? Why does white rice, for instance, have a higher GL than, say, honey? It has to do with the way nature constructed them.

Carbohydrates consist of starches and sugars. Starch—think of starchy foods like beans and potatoes—is made up of sugar molecules bound together in long chains. When you eat a carbohydrate-rich food, your body converts those starches and sugars into glucose, or blood sugar. Some starches, like those in white rice, are extremely easy for the body to convert, and therefore blood sugar levels rise like a hot temper after you eat them. Others, like those in beans, take a lot more work to break down, so blood sugar levels simmer rather than explode.

Four factors determine how fast the body breaks down carbohydrate.

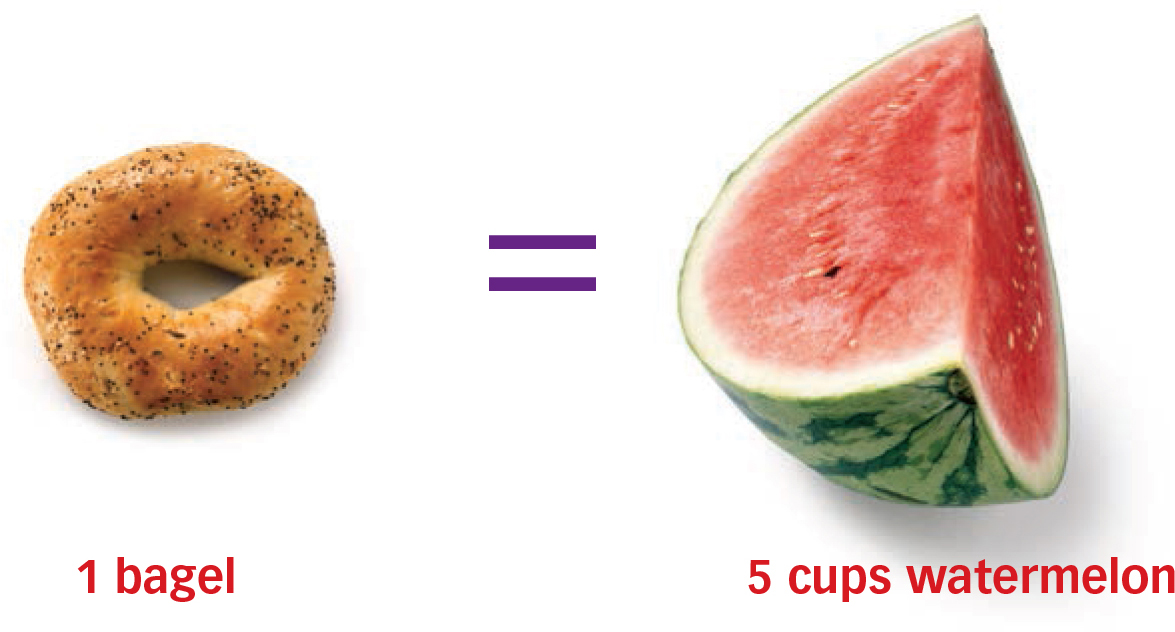

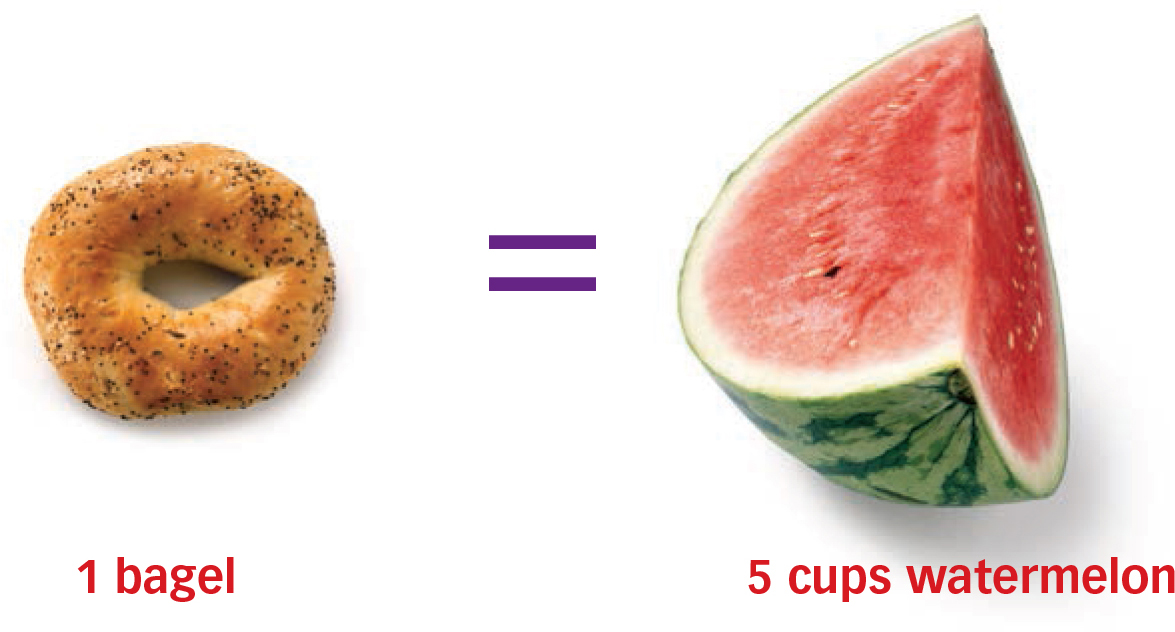

The glycemic load takes into account how much carbohydrate a serving of food contains. The amount in one bagel equals the amount in five helpings of watermelon.

55 grams of carbohydrate

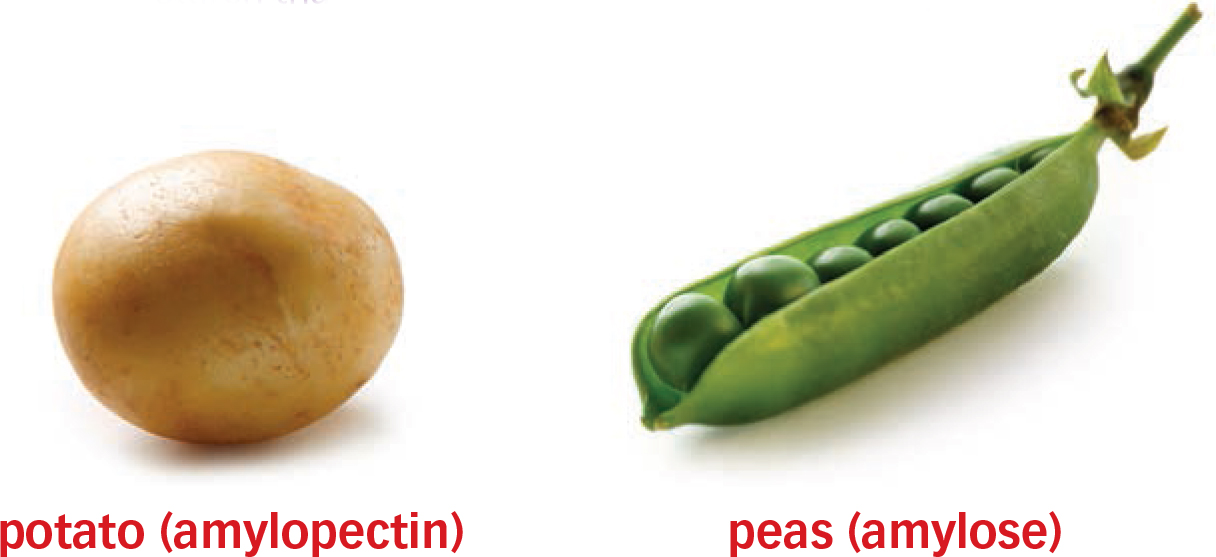

Remember, starches are made of sugar molecules chained together. Some chains have straight edges, while others are branched. The straightedged type, called amylose, is harder for your body to break down and turn into blood sugar. The branched type, called amylopectin, is much easier to break down because there are so many places for the enzymes that break down starch to get at it. Think of a tree with lots of branches—there are a lot more spots for birds to land on it compared to a simple post.

White potatoes are very high in amylopectin, the branched kind of sugar chain, which is why they raise your blood sugar in a jiffy. Peas and lentils are high in amylose, the straight kind, so they’re converted to blood sugar at a snail’s pace.

The more amylose a food contains, the slower it will be digested and converted into blood sugar. Take rice, for instance. Some types contain more amylose than others. In general, the softer and stickier the rice is after cooking, the lower its amylose content; this is why “sticky rice” is dastardly to your blood sugar. The firmer the rice, the higher the amylose and the harder it is for your body to turn into blood sugar quickly—making brown rice a better choice. Some genetic variants of rice—such as some sold in Australia, for example—are particularly high in amylose (as much as 25 percent), but unfortunately, most of the rice we eat is low in amylose and thus has a high GL.

Sugar is the molecule that makes up carbohydrates, but there is more than one kind. There’s table sugar (sucrose) as well as the kind found in fruits and grains (fructose), the kind in milk (lactose), and the kind in malted barley (maltose). The sugar in milk and fruit tends to be absorbed more slowly than other sugars which is why these foods are gentle to your blood sugar.

Ironically, table sugar, which is half fructose and half glucose, is turned into blood sugar more slowly than some starches, like bread or potatoes. That doesn’t make sugar good for you, of course. One reason is that fructose, especially in the amounts contained in packaged foods loaded with added sugar and high-fructose corn syrup, raise triglycerides, blood fats that increase the risk of heart attack. (Fruit, by contrast, contains a little fructose plus plenty of water, fiber, and nutrients.) The other reason is that sugar packs a lot of carbohydrate calories in a small package. That’s why one 32-ounce (1-liter) cola drink contains a whopping 400 calories—and will send your blood sugar soaring.

Potatoes raise blood sugar fast because the type of starch they contain is easily broken down. Peas contain a type of starch that’s broken down much more slowly.

All starch, whether it’s made of straight or branched chains, is composed of crystals, which don’t dissolve in cold water. Think of a grain of rice or a piece of raw potato—put it in water and it stays the same. But heat breaks down those crystals so the starch can dissolve in water—a little like a snowflake that comes in from the cold. When you cook a starchy food, it absorbs water and becomes easier to digest.

The more overcooked rice or pasta is, the faster it makes your blood sugar rise. When starch is heated and then cooled, it can return, in part, to its crystal form; that’s why hot potatoes have a high GL, while potato salad’s is slightly lower. Just make it with olive oil reduced-fat mayo to keep it healthier.

Have you ever noticed that some wheat breads are as smooth as white bread, while others have crunchy kernels in them? Those kernels take a long time for your body to break down. So do any whole, intact grains, such as wheatberries (small kernels of wheat, delicious in salads).

Modern commercial flour, on the other hand—especially white flour—is extremely easy for the body to turn into blood sugar, which is why we suggest throughout this book that you choose whole grains that are still intact and foods such as beans, lentils, and wheatberries instead of those made from white flour. (Unfortunately, we’re surrounded by white-flour foods. You’ll need to make a conscious effort to cut back.)

Until the 19th century, the main way to turn grain into flour was to grind it between stones, sometimes powered by a water wheel. Making very fine flour took a lot of work, and it was available only in small amounts to the rich. Then high-speed, high-heat steel rollers, which make very fine flour quickly and inexpensively, were invented, almost instantly transforming our diets into blood sugar nightmares.

In a study, folks who ate a high-protein diet consumed 25 percent FEWER calories than those in the high-carb group.

Modern manufacturing also allows grains to be turned into highly processed forms such as cornflakes or puffed corn snacks, which tend to have higher GLs than grains left intact, like popcorn, or those milled in an old-fashioned manner, like coarse, stone-ground whole wheat flour used in stone-ground wheat bread.

Unlike carbohydrate, protein doesn’t raise blood sugar. Your body breaks it down into amino acids, which it uses as building blocks for muscles as well as many compounds such as neurotransmitters, the brain’s chemical messengers. Unless you’re on a diet that severely limits carbs, your body won’t even try to convert protein into blood sugar.

That’s why you’ll find protein foods such as fish, chicken, beef, pork, soy, milk, eggs, and cheese on our list of Magic foods. If you substitute calories from one of these foods for some of your carbohydrate calories, your blood sugar will thank you. For instance, if you add shrimp to a rice dish, you’ll eat less rice, and the meal will have less impact on your blood sugar.

While we’re fans of protein, we’re not suggesting a diet of fatty bacon, greasy burgers, and the like. These are packed with saturated fat, and as you’ll read a bit later, saturated fat increases insulin resistance, which is bad for your blood sugar. Lean protein foods, like fat-free milk and chicken breast without the skin, are far better choices because they contain fewer calories and less saturated fat. Fish and shellfish are definitely on the menu because they’re not only low in saturated fat but also high in heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids. Beans, peas, and lentils, all high in protein, have the added plus of being rich in fiber.

We’re also not suggesting an extremely high protein, low carb diet. You’ll find out why in the next chapter.

There are also other benefits to protein. Some of the compounds our bodies make from protein’s amino acids help regulate blood sugar, so including protein in a meal means your body will handle the carbohydrates in that meal more efficiently. That’s one reason we want you to include a source of protein with every meal. Another reason: Your body takes a while to break down the protein in the foods you eat, and this slows the digestion of the whole meal, including the carbs it contains, making for a slower rise in blood sugar.

In one recent study, healthy volunteers ate a starchy breakfast (white bread) followed by a starchy lunch (mashed potatoes and meatballs). On some days, however, they got extra protein in the form of whey (dairy protein). On days when they ate more protein, their blood sugar levels were more than 50 percent lower in the following 2 hours than on days when they ate mostly carbs. Another study, of people with diabetes, found that adding whey reduced their blood sugar response by 21 percent over the following 2 hours.

Protein, especially the kind found in milk, also stimulates the pancreas to produce insulin. That may not sound like a good idea since having high levels of insulin over long periods of time is unhealthy. But the earlier your body makes insulin in response to a rise in blood sugar, the less insulin it may need to make—and the less likely you are to become insulin resistant.

Eating more protein-rich foods should even help you lose weight. Protein puts a damper on hunger, expanding the time between when you eat and when your stomach starts rumbling again. Research proves it. In a six-day study, one group of volunteers went on a low-GI, high protein diet. The other group followed a low-protein, high-carb diet. Both groups were allowed to eat as much as they wanted—and the folks who ate the high-protein diet consumed 25 percent fewer calories than those in the high-carb group. In a longer study, lasting six months, high-protein dieters lost more weight than high-carb dieters. They ate less because they felt fuller.

Getting enough protein can also help keep your metabolism running at full speed. Usually, when you really cut back on calories—especially if you go on a very low carb diet—your body resorts to breaking down muscle tissue for energy. But muscle tissue burns up a lot of calories even when you’re not flexing a thing, so breaking it down slows your metabolism. Eating plenty of protein helps your body keep its muscle tissue.

In diet studies, people on moderately high protein diets lost more body fat and less muscle. A moderately high protein diet might get as much as 30 percent of its calories from protein, rather than the 15 to 20 percent most people get. Twenty to 30 percent is the protein intake we recommend.

Fat has gotten a bad rap, to the point where most people think the less fat you eat, the better. Research is proving that this just isn’t true.

During the height of the low-fat craze, people loaded up on carbohydrates like fat-free chips and low-fat cookies—foods laden with fast acting carbohydrates—thinking they were doing themselves good. What a mistake! They were actually wreaking havoc on their blood sugar and eating just as many calories in the bargain.

The fact is, fat’s no demon. Some fats are positively good for you and your blood sugar, and they absolutely belong in your diet.

Like protein, fat doesn’t raise blood sugar, so swapping carb-rich foods such as pretzels for fatrich foods such as nuts can be an excellent trade.

Also like protein, fat takes a while to digest. Because it slows the rate at which food leaves your stomach, it can blunt the blood sugar effect of a whole meal, even if that meal includes carbs. Tossing your salad with olive oil or drizzling some on your pasta, adding some nuts to your rice, broiling fatty fish for dinner, or using slices of ripe avocado in your sandwich won’t magically keep your blood sugar lower, but it will help.

Adding protein to a carbohydrate dish lowers the glycemic load of the dish— assuming you eat the same amount—because you end up eating less carbohydrate. Protein itself also helps steady blood sugar.

Notice that we’ve talked about nuts, oils, and fish instead of other fat sources such as burgers or butter. It’s true that adding fat lowers the GL of a starchy food, but adding butter or sour cream to a heap of mashed potatoes doesn’t make it healthy. Quite the contrary.

Butter, which comes from cow’s milk, is an animal food, and as with many animal foods, most of the fat it contains is saturated. That’s the kind that clogs arteries. It’s also bad for blood sugar. In both animal and human studies, a diet high in saturated fat has been shown to trigger insulin resistance, which it does in many ways. Saturated fat increases inflammation, which is toxic to cells, including those that handle glucose. It also makes cell membranes less fluid, so the insulin receptors there are less responsive to insulin; the hormone bounces off them like water off a drum rather than sticking to them.

A moderate-fat diet can be every bit as effective as a low-fat diet in helping you LOSE weight.

It’s clear that people who eat the most saturated fat are at the highest risk of developing insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. And as you read in Chapter 1, these conditions increase your risk of heart disease and diabetes.

The trick, then, is to avoid the worst of the “bad” fat foods, like marbled steak, high-fat lunchmeats, butter, whole milk, full-fat cheeses, and ice cream, and choose instead lean cuts of meat and poultry, fat-free or 1% milk, lower fat cheese, and lean lunchmeats such as turkey, chicken, and lean roast beef.

Even better, embrace unsaturated fats, which can actually improve insulin sensitivity, thus benefiting your blood sugar. These fats come mainly from plants—think avocados, nuts and seeds, olives, and olive and canola oil—and fish and seafood. The Mediterranean diet, one of the healthiest diets in the world, gets a moderately high 30 to 35 percent of its calories from fat, mostly the unsaturated kind. This is the fat ceiling we recommend.

“Good” fats are also good for your heart. Swapping that cheeseburger for seafood or that butter for peanut butter (a good source of unsaturated fat) lowers your “bad” LDL cholesterol while leaving “good” HDL cholesterol alone. In fact, eating just a handful of nuts a few times a week can slash your risk of getting heart disease by 25 percent.

So can eating fish a few times a week. Seafood contains omega-3 fatty acids, which do a world of good for your heart by lowering triglycerides, helping prevent blood clots, reducing inflammation, and promoting normal heart rhythm. Eating just two servings of fish—especially fatty fish such as salmon or mackerel—a week can reduce your risk of heart disease by a third or more.

You’d think that if you want to lose weight, you should cut way back on fat, which is high in calories. Pretty obvious, right? Surprisingly, recent research has shown it’s not necessarily true. A moderate-fat diet can be every bit as effective as a low-fat diet in helping you lose weight—if you choose mostly beneficial fats.

A bit of fat also makes meals more satisfying, which can make it easier to stick to a healthy eating plan over the long haul. Try to go too low fat, and you’ll most likely throw in the towel at some point, probably sooner rather than later. In one study of overweight men and women, those on a moderate-fat diet lost about 9 pounds (4 kg) over 18 months, while those on a low-fat diet actually wound up gaining more than 6 pounds (3 kg). One key reason was dieting fatigue: Only 20 percent of those on the low-fat diet were still actively participating by the end of the study, while 54 percent of those on the moderate-fat diet were still at it.

Carbs, protein, and fat are all macronutrients—nutrients that provide the vast majority of our calories. Fiber doesn’t count because it isn’t digested by the body, so it provides not a single calorie. Nevertheless, it’s an extremely important element in a Magic diet.

There are two types of fiber: soluble and insoluble. Soluble fiber is the kind that dissolves in water. It’s found in oats, barley, beans, and some fruits and vegetables. Insoluble fiber is found mostly in whole wheat and some fruits and vegetables. Both types are very good for you, but only soluble fiber will help lower your blood sugar—in a big way.

How big? Researchers at a USDA Diet and Human Performance Laboratory tested oatmeal and barley (which is even richer in soluble fiber than oatmeal) on overweight middle-aged women. On days when the women ate oatmeal for breakfast, their blood sugar levels over the following 3 hours were about 30 percent lower than when they ate a sugar-laden pudding. On days when they ate barley cereal, it was about 60 percent lower.

How does soluble fiber work its magic? When it mixes with water, it forms a gum. Think of oatmeal; you can pick out the grains or flakes when it’s dry, but once you cook it, it’s one big mush. This gooey gum forms a barrier between the digestive enzymes in your stomach and the starch molecules in food—not just in the oatmeal but also in the toast you ate with it. Thus, it takes longer for your body to convert the whole meal into blood sugar.

Eating more foods rich in soluble fiber is a key strategy for lowering your blood sugar after meals. It will also improve your health in other ways. Oatmeal is famous by now for lowering cholesterol, but it may lower high levels of triglycerides and reduce blood pressure as well. There’s even a health claim allowed on oatmeal packaging: “Eating 3 grams of soluble fiber from oatmeal in a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of heart disease.” (About 1 1/2 cups of cooked oatmeal supplies 3 grams.) Lots of other foods are also rich in soluble fiber (see “Best Foods for Soluble Fiber”).

Eating more foods rich in soluble fiber is a key strategy for lowering your blood sugar after meals.

Nutrition experts tell us to aim for at least 25 grams of total fiber a day, both insoluble and soluble. A good goal for soluble fiber is 10 grams. Sound like a hard goal to reach? Here are some foods you might eat in a typical day that would add up to more than 10 grams.

Breakfast: A cup of cooked oatmeal with a chopped medium apple; soluble fiber: 3 grams.

Lunch: Add a side dish of black beans (1/2 cup); soluble fiber: 2 grams.

Dinner: Add a side dish of roasted Brussels sprouts (about 1 cup); soluble fiber: 6 grams.

In case you’re counting, that’s 11 grams. Not surprisingly, many of these fiber-rich foods also have low GLs, so they can help lower the GL of a meal if you use them to replace other carbs. For instance, if you ate a combination of 1/2 cup of rice and 1/2 cup of beans instead of 1 cup of rice, you’d drop the GL by almost half.

Wouldn’t it be terrific if there were a simple ingredient you could add to your meals that would act like an anchor, keeping blood sugar from rising too high? As it turns out, there is. It’s acetic acid, the sour-tasting compound that gives that characteristic tang to vinegar, pickles, and sourdough bread.

The effect can be quite dramatic. In one small study, people who ate a buttered 3-ounce (85-g) bagel and orange juice—a high-GL breakfast—saw their blood sugar shoot up in the next hour. But when they also drank about a tablespoon of apple cider vinegar (with artificial sweetener added to improve the taste), their blood sugar levels after the meal were 50 percent lower! A similar 50 percent reduction in blood sugar happened when they had the vinegar along with a chicken-and-rice meal.

How does acetic acid make it happen? Scientists aren’t sure, but they do know that it interferes with the enzymes that break apart the chemical bonds in starches and the kinds of sugars found in table sugar and milk. This means it takes your body longer to break down those foods into blood sugar. Other researchers believe acetic acid keeps foods in the stomach longer so they aren’t digested as quickly. Acetic acid may also speed up the rate at which glucose is moved out of the bloodstream and into muscle cells for storage.

No matter how it works, it does, and taking advantage of it is as easy as adding vinegar to salads and other foods and having a pickle with your sandwich at lunchtime. Lemon juice also has “pucker power” and seems to help control blood sugar. You’ll read more about vinegar, lemon juice, and sourdough bread in Part 2.

Now you understand why rice raises blood sugar fast while oatmeal raises it more slowly and chicken doesn’t raise it at all. And why the soluble fiber in beans and the acetic acid in vinegar help keep your blood sugar steady. If you don’t feel like remembering the details, don’t. You don’t need to. In Chapter 4, we’ll reveal the Seven Secrets of Magic Eating, and if you follow these rules, you’ll be eating for better blood sugar.

You don’t even need to bother with the exact GL numbers of the foods you eat (although we do supply them for some common foods on pages 55–58). In this book, we’ve simply classified foods according to very low, low, medium, high, and very high GL. The foods you’ll read about in Part 2 have very low, low, or medium GLs—part of what makes them Magic.

It’s important to note that you don’t always have to choose foods in the “low” category. Eating just one low-GL food in a meal in place of a high-GL food is enough to tame your blood sugar response to the whole meal. Also remember that a food’s GL is based on a moderate portion; if you eat twice as much, the effect on your blood sugar will be twice as great. Of course, the converse is also true: If you eat 50 percent less of a starchy food, your blood sugar response will be 50 percent lower. In each Magic food entry in Part 2, you’ll find out the size of an appropriate serving of that food. Keeping your portions under control is of course the best way to lose weight, whether or not you choose low-GL foods.

You’ll learn much more about how to focus on Magic foods later in the book. First, in case you’re tempted after reading this chapter to switch to a very low carb diet, let us explain why that’s a bad idea.