Long before there were roads in the modern sense, there were river roads. Look at any map of any country and be reminded that the older, more established cities—if not on a coastline—were founded on the banks of rivers, whose currents and near-frictionless surfaces made for quicker and more economical transportation than the available land-based modes of transport. Yet while rivers have been conducive to transportation and settlement along their lengths, they have at the same time presented barriers to movement where bridges have been few and far between. And so arises their age-old role as natural borders.

The Mississippi is just such a barrier-road, fostering settlement and commerce while at the same time creating a sort of natural pause in America’s relentless westward movement. As you cross the Mississippi River, you pass over one of the North American continent’s most vital arteries, one which served to nourish and sustain generations of mankind long before the invention of asphalt and the proliferation of the internal combustion engine. What is more, you leave behind the older and more established portion of the American experience, and you pass both physically and spiritually into one of America’s most important chapters: westward expansion.

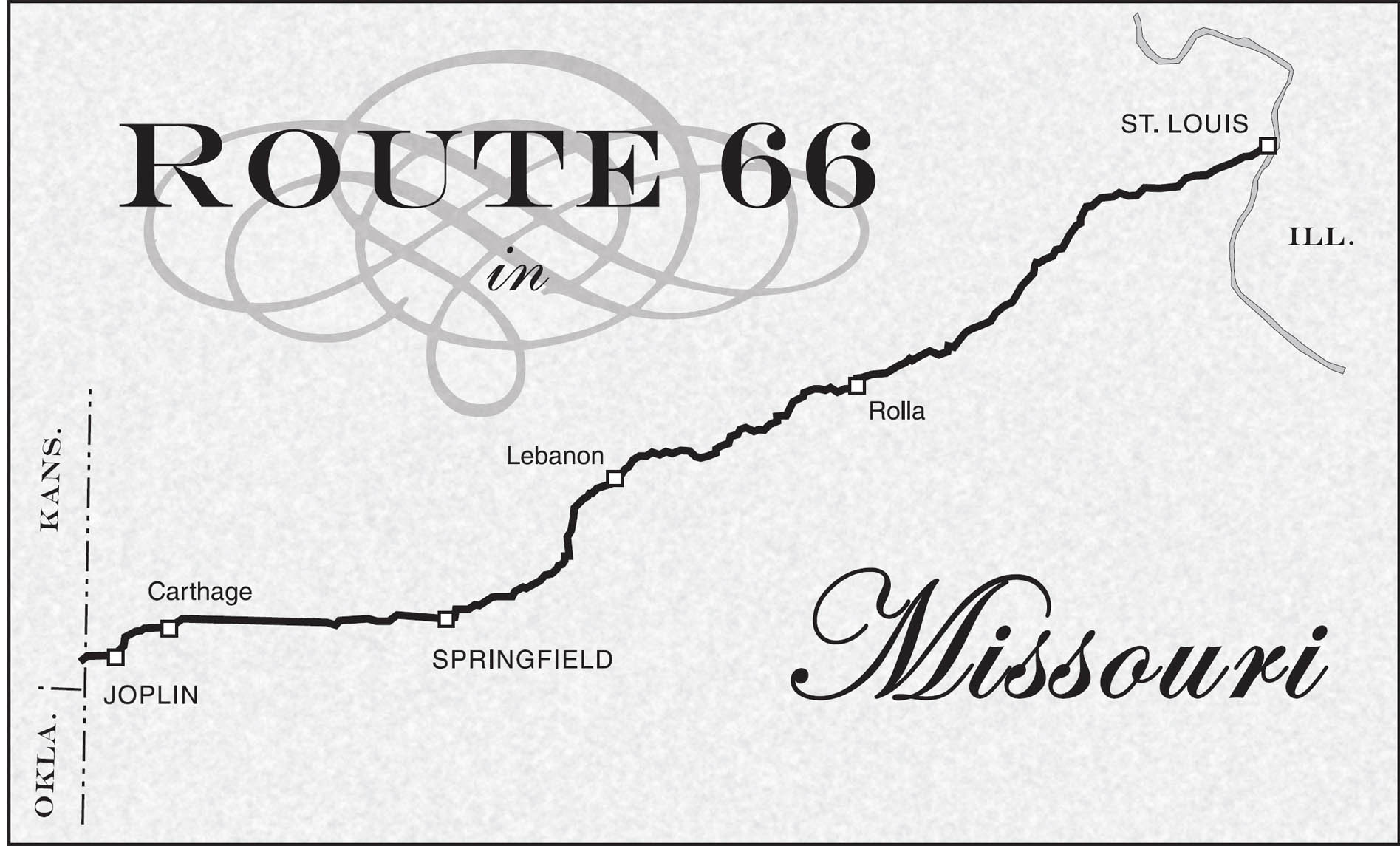

Missouri—first at St. Louis, then later at Independence—was long the staging ground for that westward impulse. Situated at the threshold of an enormous, uncharted wilderness, this was the last bastion of civilization and the last chance to prepare and outfit for the rigorous journeys that lay ahead. Just as Chicago is the starting point for Route 66, Missouri is the starting place for the famous migratory trails of history that made settlement of the West a reality: the Overland, Oregon, and Santa Fe trails all had their origins here on a Missouri riverbank. And, under the sponsorship of President Thomas Jefferson, a corps led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out from here on the Voyage of Discovery in 1804, eventually finding its way to the Oregon coast.

As for U.S. Highway 66, it crossed the Mississippi River into the Show Me State at several places over the years. Today, you may want to avoid the older alignments, which crossed the river directly into the central part of St. Louis.

Unfortunately, those alignments of the highway pass through sections of the city that are congested and do not always feel safe. For that reason, and also because urban alignments tend to fragment over time and become very hard to follow, you may prefer to approach St. Louis via the “bypass” route, which used to take the traveler across the Chain of Rocks Bridge.

Today, the Chain of Rocks Bridge is closed to auto traffic, but it has been turned into a recreational attraction open to pedestrians and is also the scene of frequent special events. The bridge is just south of Highway 270 and Riverview Boulevard, and is touted as “the world’s largest bicycle and pedestrian bridge.” Earlier in its history, a popular park named Riverview sat near the end of the Chain of Rocks Bridge on the Missouri side of the river. There, St. Louisans gathered for picnics, skating, swimming, and softball. Riverfront Trail now connects the bridge with the Gateway Arch to the south. Up on the bluff overlooking the bridge and the site of the old park, there used to be a fairly elaborate amusement park called Fun Fair Park. Fun Fair Park and its sundry attractions failed to survive the competition from Six Flags Over Mid-America, which opened just to the west, near Eureka, in the early 1970s.

Opened to traffic from 1929 until the late 1960s, the former toll bridge with the distinctive bend in the middle was used in the filming of 1981’s Escape from New York. It is here that Adrienne Barbeau’s character meets her demise, while Kurt Russell makes good his own escape.

![]() Today’s Mother-Roader usually crosses the Mississippi just a little north of the Chain of Rocks Bridge on Highway 270. This modern-day loop highway has replaced the old route for several miles along here. Exit Highway 270 at Highway 67 and go south to follow the course of 66 as it once skirted the city. Head due south on 67 until you meet up with the city alignment of 66 at Watson Road (now numbered 366) near the community of Kirkwood. Turn to the east here to take in some of what St. Louis has to offer before continuing your 66 odyssey west.

Today’s Mother-Roader usually crosses the Mississippi just a little north of the Chain of Rocks Bridge on Highway 270. This modern-day loop highway has replaced the old route for several miles along here. Exit Highway 270 at Highway 67 and go south to follow the course of 66 as it once skirted the city. Head due south on 67 until you meet up with the city alignment of 66 at Watson Road (now numbered 366) near the community of Kirkwood. Turn to the east here to take in some of what St. Louis has to offer before continuing your 66 odyssey west.

As an alternative, you can also drive from Illinois into Missouri via an older alignment of Route 66 that crossed over the McKinley Bridge. That route is described near the end of the Illinois chapter.

ST. LOUIS

![]()

![]()

Route 66 took several paths around and through St. Louis over the years. As with other urban areas, 66 originally passed through the downtown business district, but was later re-routed to avoid central-city congestion by creating beltline or bypass routes. For most of its life, U.S. 66 was marked to offer the driver two or more choices in traversing the area, depending on his or her objectives. There’s plenty to do and see in St. Louis, so today’s roadie will want to stray from the standard alignments anyway.

The city of St. Louis attained what many consider to be its high-water mark in the first decade of the twentieth century. In 1904, the city hosted the World’s Fair and summer Olympic Games. The fair was timed to coincide with the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. The following year, 1905, St. Louis had the dubious distinction of being the city with the first recorded auto theft. At the end of the twentieth century, St. Louis was the fastest-shrinking major city in the U.S., with its population declining by more than twelve percent during the 1990s.

The 1904 World’s Fair (or St. Louis Exposition) enjoyed a number of distinctions, having played a role in the evolution of ice cream, hamburgers, and iced tea. It was there that ice cream was first served in cones when a Syrian immigrant named Ernest Hamwi came to the rescue of an ice cream vendor who had run out of serving dishes. By the end of the fair, it was reported that several vendors were selling ice cream in folded waffles.

That same fair was also the scene of the mass introduction of the hamburger served on a bun, a development which had originated just a little earlier in New Haven, Connecticut. This fair was also where an English tea concessionaire named Richard Blechyden determined that the weather was simply too hot for his tea to sell well. His solution was to ice it down, thus creating the decidedly un-English iced tea.

The 1904 World’s Fair was held at Forest Park—then the nation’s largest urban park at over 1,300 acres—which is still very much a part of present-day St. Louis. Forest Park contains the St. Louis Zoo (1 Government Dr.), the St. Louis Art Museum (1 Fine Arts Dr.), and the Missouri History Museum (5700 Lindell Blvd.). There are also some giant turtle sculptures on the south side of the park.

St. Louis, Missouri. GPS: 38.59046,-90.25376

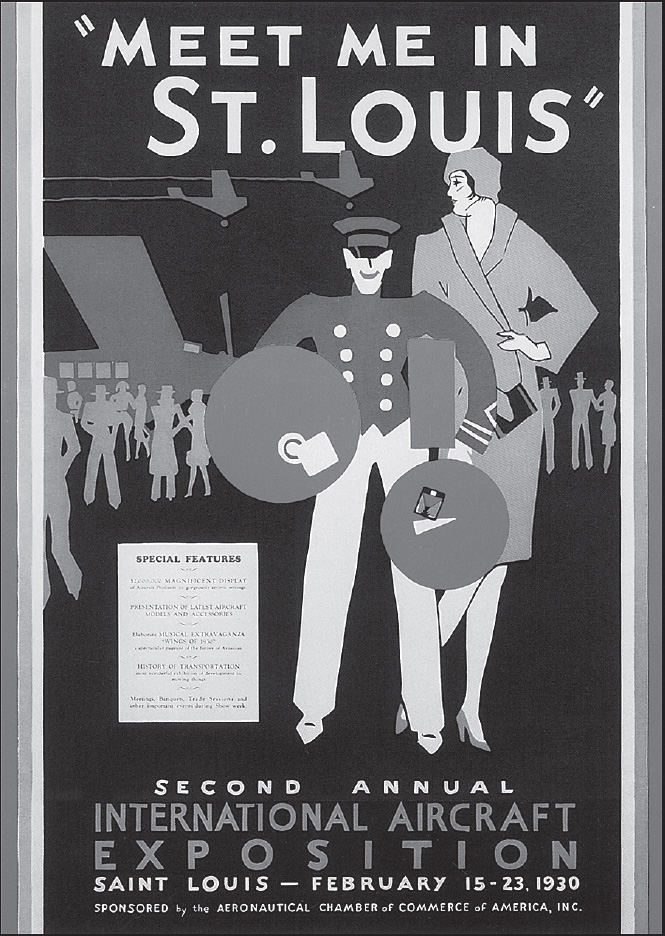

A replica of Charles Lindbergh’s famous airplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, is at the Missouri History Museum. The Spirit of St. Louis was so named because Lindbergh’s backers for the trans-oceanic flight consisted of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat newspaper and a group of local businessmen who wanted to promote their city as a center of aviation. Earlier, Lindbergh had approached the American Tobacco Company with the idea of naming the craft after their Lucky Strike cigarettes (Lindbergh had already been nicknamed “Lucky” Lindy by that time), but the company refused to back the venture. The replica at the Missouri History Museum was manufactured by the same firm that made the original, and it was used in the Jimmy Stewart movie.

In 1944, Judy Garland starred in a musical entitled Meet Me in St. Louis, which portrayed the year the world came to visit the city for the fair (the title song, “Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis” actually dates from the year of the Exposition). It was during the filming of that movie that Judy Garland became romantically involved with her future husband, Vicente Minelli.

Betty Grable, pin-up girl par excellence during World War II, was from St. Louis and lived at the Forest Park Hotel (4910 W. Pine Blvd.). Vincent Price graduated from St. Louis Country Day School (101 N. Warson Rd.). Miles Davis and Chuck Berry were both born here in St. Louis. Another St. Louis native, the moody T. S. Eliot, won the 1948 Nobel Prize in Literature; well after his death, one of his lighter works, Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, inspired the Broadway musical comedy Cats. You will be amazed at the number of St. Louisans who have made it big in the world and have been inducted into the city’s Walk of Fame on Delmar Avenue (see the Attractions section below).

Here in St. Louis, there’s a Route 66 institution still going strong that you simply must pay a visit to: Ted Drewes Frozen Custard (6726 Chippewa St.). The building itself is an important landmark, but the crucial thing is that this business still believes in the older values of a quality product and personal service. They’ve never “sold out” for a fast buck, and their adoring public appreciates it. Their list of mouthwatering toppings is printed right on the side of the building to stoke your anticipation. Stop by some morning before opening time and watch the people begin to flock in from all over. In no time at all, the place will be mobbed, and it happens virtually every day. And check to see if there’s still a mannequin peering out from one of the upstairs windows.

Before leaving St. Louis and hitting the road once again, consider heading down to the riverfront area that the Highway 270 alignment avoided on your way in. The Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (11 N. 4th St.) includes the Gateway Arch and the Museum of Western Expansion at its foot. Eero Saarinen’s famous 630-foot archway aptly symbolizes the area’s role as a gateway to the West. The arch contains a pair of elevator-trams that swivel as they ascend to the top, sort of like a Ferris-wheel car, constituting a feat of engineering in and of themselves. There is a terrific panoramic view from the top of the arch, and there is also a film, Monument to the Dream, which details its construction (the arch was completed in 1965). The adjacent museum, which is as large as a football field, presents information about the Louisiana Purchase and the Jefferson-sponsored Lewis and Clark Expedition. Also part of the memorial complex is the Old Courthouse. This building originates from 1839, and was the site of the early trials of the Dred Scott case, which was ultimately decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1857.

Ted Drewes Frozen Custard is still a popular stop for both roadies and St. Louisans, as it has been since the heyday of Route 66. GPS: 38.58960,-90.30767

Elsewhere downtown, the old Union Station railroad depot (1820 Market St.) has been nicely converted into a luxury hotel and eclectic shopping venue.

ST. LOUIS ATTRACTIONS

You can spend a considerable amount of time at the Blueberry Hill Restaurant (6504 Delmar Blvd.), just admiring the great memorabilia on display that includes posters, album covers, and vintage toys. However, a more “gut” reason to come in is the restaurant’s extraordinary burgers. The Blueberry Hill also plays host to the largest annual dart tournament in the United States, with approximately 500 entrants each year.

At Fitz’s Root Beer (6605 Delmar Blvd.), you can enjoy your meal and watch root beer being bottled at the same time. The equipment dates from the 1940s, and is visible from the main dining area.

In the 6100 through 6600 blocks of Delmar is the St. Louis Walk of Fame. Here there are stars embedded in the sidewalk on both sides of the street, honoring nearly a hundred men and women who are connected to St. Louis and have made an impact on the world at large. They run the gamut, from Yogi Berra and Josephine Baker to William Burroughs and Virginia Mayo. In 2009, this same stretch of Delmar became the home of the Delmar Loop Planet Walk, a walkable (2,880 feet) “model” of the solar system, where representations of the sun and planets are proportionally spaced according to their real-world relationships.

During Prohibition, the local Anheuser-Busch brewery sold non-alcoholic brews from the Bevo Mill (4749 Gravois Rd.), a replica of a Dutch-style windmill built in 1916. The mill still stands, and was recently refurbished for its new life as a special-events venue. Across the street is the Miniature Museum of Greater St. Louis (4746 Gravois Rd.).

St. Louis’s City Museum (750 N. 16th St.) is located in the heart of the loft and garment district, and is more offbeat than its name would imply. It is housed in the International Arts Complex, which was formerly the home of the International Shoe and Rand Shoe companies, two of the leading shoe manufacturing firms of yesteryear. Included among the exhibits is the Tiny Trailer of Tragedy, once owned by Elvis and Priscilla Presley, as well as the world’s largest pair of underpants. The museum has also added a rooftop water park.

Formerly on display at the City Museum, but relocated to the Brown Shoe Company headquarters, is the Shoe of Shoes (8300 Maryland Ave.). It consists of hundreds—perhaps thousands—of life-sized, cast-metal shoes welded together in the shape of one enormous woman’s pump. This city used to be so well-known for its shoes that at one time wags used to say of St. Louis: “First in shoes, first in booze, and last in the American League.” Of course, that was when the St. Louis Browns were still playing America’s pastime.

Not on the route, but well worth a look. St. Louis, Missouri. GPS: 38.58157,-90.26688

Faust Park (15185 Olive Blvd.) includes an 1820 estate home, historical village, and butterfly house, as well as a restored Dentzel carousel formerly owned by the second governor of Missouri.

The Anheuser-Busch Brewery (1127 Pestalozzi St.), the world’s largest brewery, offers tours, beer tastings, and brewing demonstrations. And don’t forget its world-famous Clydesdales.

Calvary Cemetery (5239 W. Florissant Ave.) covers more than 400 acres and includes the gravesites of such notables as playwright Tennessee Williams, General William Tecumseh Sherman, and Dred Scott. There is also a large crucifix marking the location of a mass grave; at the time of the cemetery’s establishment, earlier burials of American Indians were collected and reinterred at that spot. Adjacent to Calvary is Bellefontaine Cemetery (4947 W. Florissant Ave.), where explorer William Clark and other notables are buried.

The Ulysses S. Grant Historic Site (7400 Grant Rd.) was the Grant family residence from 1854 to 1858 and is known as White Haven. Adjacent to it is Grant’s Farm (10501 Gravois Rd.), a ranch that includes an 1856 log cabin, free-roaming animals, breeding Clydesdales, and a fence made from Civil War rifle barrels. The property was purchased by the Busch family in 1903.

The Campbell House Museum (1508 Locust St.), the first home built in the elegant Lucas Place neighborhood, has been restored to its 1880s prime and is open for tours Wednesday through Saturday. The home still has many of its original furnishings, including some of the family carriages.

Canine lovers won’t want to miss the American Kennel Club Museum of the Dog (1721 S. Mason Rd.). The permanent collection includes a great many oil paintings and other works of art devoted to man’s best friend, some by household names like William Wegman. Rotating exhibits have included matchbook cover art portraying dogs.

The Eugene Field House & St. Louis Toy Museum (634 S. Broadway) is the former home of the Field family and features a book collection spanning 250 years, as well as antique and collectible toys. The son of a prominent attorney, Mr. Field was known as the Children’s Poet, as well as Father of the Personal Newspaper Column.

The St. Louis Car Museum (1575 Woodson Rd.) has more than 150 legendary vehicles on display.

Take a tour of the Samuel Cupples House (3673 W. Pine Blvd.) on the grounds of St. Louis University. The forty-two-room mansion was built in 1888, and features gargoyles, ornate stonework, and twenty-two fireplaces. It also boasts Tiffany glasswork and other decorative arts dating from the fifteenth century onward. On the third floor is a special exhibit, the Turshin Fine Arts Glass Collection of American and European Art Glass.

Also open for tours is the Scott Joplin House State Historic Site (2658 Delmar Blvd.). Here, Joplin and his wife kept a modest flat that was built circa 1902. There is a music room with an operating player piano so visitors can experience first-hand the type of ragtime piano that Joplin used himself.

The Cherokee-Lemp Historic District is a south-side neighborhood with two nineteenth-century mansions (the Lemp and the DeMenil), as well as the Lemp Brewery, which was once the largest in the world. The Lemp Mansion (now an inn and restaurant) is said to be haunted by the spirits of four family members who committed suicide in the house, and a fifth who died there under the proverbial “mysterious circumstances.” The district is bounded by the streets of Cherokee Street, Lemp Avenue, Utah Street, and DeMenil Place.

Jasper’s Antique Radio Museum (2022 Cherokee St.) has over 10,000 radios in its collection, making it the largest in the world. The owner, Jasper Giardina, has a stated goal of repairing and restoring any radio that crosses his path. You’ll see everything from fully restored examples to basket cases fresh from the attic, and everything in-between. Many are for sale.

Open only on the first Saturday of the month, the Compton Hill Water Tower (S. Grand Blvd. and Russell Blvd.) was built in 1898, in a style described as French Romanesque. The observation deck offers a 360-degree view after a climb of 198 steps.

The Kemp Auto Museum (16955 Chesterfield Airport Rd.) specializes in Mercedes-Benz automobiles, with specimens from as early as 1886.

The Moto Museum (3441 Olive St.) is a collection of motorcycles representing more than a dozen countries of manufacture.

FURTHER AFIELD

Just northwest of St. Louis is the city of St. Charles. Be sure to check out the St. Charles Visitors Bureau (230 S. Main St.) while you’re here. The city’s central business district was named the “Williamsburg of the West” by a national magazine.

St. Charles is where Lewis and Clark began their long journey of discovery after camping here in the spring of 1804. You can see the departure point for Lewis and Clark’s expedition—Bishop’s Landing—at the Lewis & Clark Boat House and Nature Center (1050 S. Riverside Dr.). Replicas of the vessels used in the voyage can be seen on the lower “boathouse” level, while the museum level above has extensive exhibits of other kinds.

In the St. Charles historic district is the First Missouri State Capitol Historic Site (200 S. Main St.). This federal-style row house is where the territorial government met from 1821 to 1826 to reorganize into a state system of government. Sessions were held here until the new capitol building in Jefferson City was ready for use, in October of 1826. Included are legislative chambers, two residences, a dry goods store, and a carpentry shop, all of which have been restored to period appearance.

St. Charles is also home to the Missouri wing of the Commemorative Air Force (6360 Grafton Ferry Rd.). The CAF is dedicated to preserving WWII-era aircraft in flying condition as “a tribute to the men and women who built, serviced, and flew them in the defense of democracy.” This is the same organization formerly known as the Confederate Air Force; the name was changed for the sake of political correctness, but of course they never had anything to do with the War Between the States, anyway. Stop in and browse the collection of vintage warplanes on Thursdays and Saturdays.

If you’ve still got some time to spend in St. Charles, there’s the Shrine of St. Rose Phillippine Duchesne (619 N. 2nd Street), site of the first free school west of the Mississippi River. It was established in 1818 by Missouri’s only saint, who was canonized in 1988.

![]() When Route 66 was first born, it followed what is now Highway 100/Choteau Avenue out of downtown. That highway passes through such communities as Maplewood, Manchester, and Pond before meeting up with the more modern and well-traveled route at Gray Summit to the west. That alignment, however, has become quite urbanized over much of its length, and it forces you to skip several communities that you really shouldn’t miss. After exploring what St. Louis has to offer, I recommend that you take the later route, starting with . . .

When Route 66 was first born, it followed what is now Highway 100/Choteau Avenue out of downtown. That highway passes through such communities as Maplewood, Manchester, and Pond before meeting up with the more modern and well-traveled route at Gray Summit to the west. That alignment, however, has become quite urbanized over much of its length, and it forces you to skip several communities that you really shouldn’t miss. After exploring what St. Louis has to offer, I recommend that you take the later route, starting with . . .

An old roadhouse in Pond, Missouri. GPS: 38.58140,-90.66012

KIRKWOOD

Kirkwood, while once a distinct community, has been more or less absorbed by its sprawling neighbor, St. Louis. There is a very nicely restored railroad station (110 W. Argonne Dr.) in the old Kirkwood business district. The downtown business district in general has also undergone some nice work to make a pleasant, pedestrian-friendly area.

A few blocks south of the railroad depot is the Magic House (516 S. Kirkwood Rd.), a children’s museum that now occupies a former mansion built by George Lane Edwards, a director of the St. Louis Exposition, in 1901.

In the Sugar Creek area of Kirkwood, you’ll find a Frank Lloyd Wright residence (120 N. Ballas Rd.), one of only five Wright-designed structures in the entire state of Missouri. Built in the 1950s, the house is particularly notable in that it is virtually 100 percent authentic, right down to the original furnishings. Tours are available, but must be arranged in advance by calling (314) 822-8359.

Kirkwood, Missouri. GPS: 38.57900,-90.40645

Kirkwood is also home to the Museum of Transportation (3015 Barrett Station Rd.). The museum has an automobile pavilion, as well as several tracks of locomotives and other railroad stock for you to tour and enjoy. The autos include a 1963 Chrysler Turbine, and a custom-built aluminum car made in 1960 and used in the Bobby Darin movie Too Cool Blues. Among the railroad exhibits are the last steam locomotive to operate in Missouri, a wooden caboose, a complete passenger train, a tank car, and the “Big Boy,” the world’s largest-ever steam locomotive. Also on display are a tow boat and a C-47 military transport, which flew in the Second World War. But most important to Route 66 fans is the façade from one of the Coral Court Motel units, on exhibit inside. The Coral Court was a very special example of highway architecture from the heyday of postwar travel, and it stood not far from here until “redevelopment” took it in 1995. Thankfully, a small part of it has been preserved for your enjoyment. Built in 1941 of glazed hollow brick and glass block in the Streamline Moderne style, the Coral Court, even when new, was evocative of another time. Legend has it that bank robbers once stashed loot in the hollow walls of one or more units, of which the Coral Court once boasted more than seventy.

One of the many displays at the Museum of Transportation, Kirkwood, Missouri. GPS: 38.57303,-90.46295

TIMES BEACH

Times Beach was a planned community established about 1925, just on the eve of the birth of the federal highway system. Lots were sold or given away by the St. Louis Star-Times newspaper as part of a promotion, hence the name.

What happened at Times Beach, however, shouldn’t happen to anyone. Residents were forced to evacuate decades later when it was determined that the ground on which the community sat had been contaminated with dioxins, which had been present in the materials used to spray the roads for dust control. That evacuation occurred in 1982. Fortunately, the site was the object of cleanup efforts for years, and has since been turned into the Missouri Route 66 State Park (97 N. Outer Rd. E. #1), with trails, picnic areas, and river access. The visitor center includes Route 66 exhibits, and is housed in a vintage roadhouse building that dates to 1936.

![]()

![]()

After visiting the Missouri Route 66 State Park, leave the interstate again at exit #264 and cross to the south side. Follow Eureka’s W. Main Street out of town toward Allenton.

EUREKA

West of Eureka is Six Flags Over Mid-America, a large-scale theme park that adds immeasurably to the traffic in this area.

South of I-44 at exit #264 in Eureka is the Black Madonna Shrine and Grottos (100 St. Josephs Hill Rd.). Built entirely by hand by a Franciscan brother, the grottos are “dedicated to the Black Madonna, Our Lady of Czestochowa, Queen of Peace and Mercy.” These ornamental works of faith have become known far and wide.

Founded by Dr. Marlin Perkins of Wild Kingdom fame, the Endangered Wolf Center (6750 Tyson Valley Rd.) at the Washington University Tyson Research Center has sought to protect and preserve endangered wolf species through educational programs and captive breeding since 1971.

ALLENTON–PACIFIC

About a mile east of Pacific is the Red Cedar Inn, a café and former hotel that first started serving travelers on this stretch of road around 1934. It’s been closed for years, and although many citizens wanted to see it adapted for re-use, none of those ideas came to fruition. When I last visited, the Red Cedar had been leased out to a heating and air conditioning company using it for offices and equipment storage.

Pacific, Missouri. GPS: 38.48158,-90.71783

![]()

![]()

When it’s time to leave Allenton, cross to the north side of the railroad tracks to I-40 Business Loop/66.

One of the more distinctive features of Pacific is the presence of some prominent bluffs along the north side of the highway. These were considered interesting enough that they found their way onto many an early postcard of the area. There are several cave-like cavities here that resulted from silica mining.

GRAY SUMMIT

This town is best known for its association with Ralston-Purina. Just north of Gray Summit is Purina Farms (200 Checkerboard Dr.). This compound holds canine events through most of the year, which include agility trials, herding competitions, all-breed shows, and racing. One of my personal favorites is Jack Russell Fun Days, sponsored by the Missouri Earth Dog Club. These dogs are incredibly enthusiastic about racing around, rooting things out of holes in the ground, and just all-around cavorting. Aside from being fun for pets and owners alike, many of the events presented at Purina Farms are educational as well. There are workshops in dog obedience training, for example. You can also learn how to milk a cow or operate a simulated pet food manufacturing machine.

Gray Summit. GPS: 38.48298,-90.82262

West of Gray Summit, Missouri. GPS: 38.48093,-90.83157

South of the interstate and right on Historic 66 is the 2,500-acre Shaw Nature Reserve (Hwy 100 and I-44), an extension of the Missouri Botanical Garden, where prairie flora and fauna are preserved, and a visitor center, historic home, and several miles of hiking trails await.

VILLA RIDGE

Near Villa Ridge is the former Gardenway Motel, a colonial style motel that probably graced the front of many a postcard in its prime. Notice the glass-block detailing in the roadside sign. A little farther west is what remains of the Tri-County Truck Stop.

West of the Tri-County is the Sunset Motel (225–289 Historic Rte. 66), which has a unique neon sunburst-style sign that was restored and ceremonially re-lit in 2009.

Villa Ridge, Missouri. GPS: 38.46448,-90.86891

ST. CLAIR

This town was formerly known as Traveler’s Repose, but it’s said that the townsfolk grew tired of being thought of as a cemetery. For many years, St. Clair was the home of Ozark Rock Curios, a purveyor of interesting geological specimens to Route 66 tourists.

![]() Between St. Clair and Stanton, if you follow the road paralleling the railroad track (W. Springfield Road) on the south side of I-44, you’ll be taken on an old alignment of the highway through Anaconda. The town is about midway between St. Clair and Stanton, and was named Morrellton when my 1946 road map was printed. By the time my 1957 atlas was published, the town had been completely bypassed by the new alignment, and it bore the current name of Anaconda. Unfortunately, that road no longer continues to Stanton. Instead, use the later incarnation of Route 66, which today means the north I-44 service road.

Between St. Clair and Stanton, if you follow the road paralleling the railroad track (W. Springfield Road) on the south side of I-44, you’ll be taken on an old alignment of the highway through Anaconda. The town is about midway between St. Clair and Stanton, and was named Morrellton when my 1946 road map was printed. By the time my 1957 atlas was published, the town had been completely bypassed by the new alignment, and it bore the current name of Anaconda. Unfortunately, that road no longer continues to Stanton. Instead, use the later incarnation of Route 66, which today means the north I-44 service road.

STANTON

This community is best known as the gateway to the Meramec Caverns to the south (see the Further Afield section).

STANTON ATTRACTIONS

Here in Stanton you’ll find the Jesse James Wax Museum (I-44, exit #230), a true roadside attraction. The museum focuses on the theory that Jesse James didn’t really die of a gunshot wound in 1881, as the authorities have been telling us all these years—he actually lived to a ripe old age under another name and died in 1952! There are even wax figures of the conspirators featured in the retelling of this diabolical plot to mislead the public. The museum staff will enthusiastically heap evidence upon you of their version of Jesse’s life, such as a list of physical traits (scars, etc.) shared by the original Jesse and the mystery man who survived well into the Route 66 era.

Stanton, Missouri. GPS: 38.27270,-91.10760

East of Stanton is the Riverside Wildlife Center (275 Hwy W), where you can see a wide variety of native and non-native snakes and other reptilians, as well as big cats.

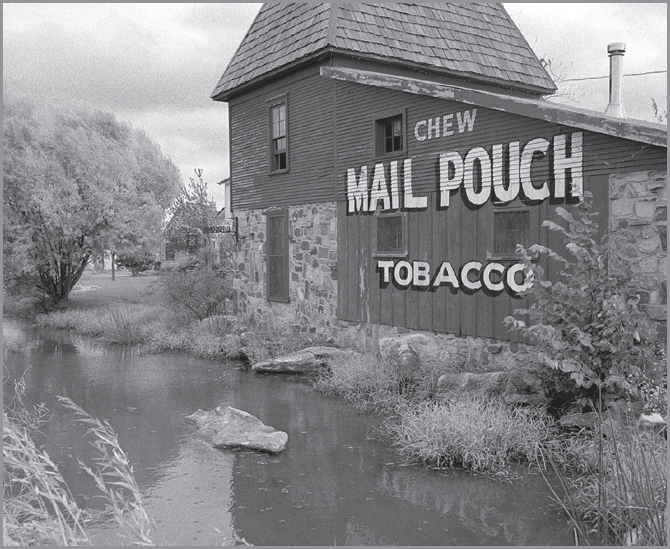

FURTHER AFIELD

Just a few miles southeast of Route 66 is one of the route’s most widely known attractions, Meramec Caverns (1135 Hwy W). In fact, a trip to Meramec Caverns is more a required pilgrimage than a side trip for anyone traveling the Mother Road. That’s largely because clever marketing made this cave a part of almost any trip down 66. First of all, when Lester Dill opened Meramec Caverns commercially in 1935, he successfully managed to portray his caverns as a former hideout of Jesse James, even though the evidence for this is fairly thin. Secondly, he paid to have the sides and roofs of barns all over the country painted with his “logo” so that motorists far and wide were made aware of Meramec Caverns. These barns dotted the countryside, not just along Route 66, but on roadsides all over the Midwest (some estimates place the number at around 350). Thirdly, each visitor to Meramec Caverns became an advertisement for the attraction. That’s because the Dill clan pioneered the bumper sticker. Youngsters were paid to ensure that each vehicle in their parking lot left with a Meramec Caverns tag tied to their rear bumper. The combination of these strategies made Meramec Caverns not just one of the best-known caves in the country, but one of the most-recognized attractions of any kind whatsoever.

Part of Meramec Caverns, a traditional tourist destination on Route 66, near Stanton, Missouri. GPS: 38.24765,-91.08852

Inside the caverns, in addition to the usual underground formations, there is a neon sign marking the “Jesse James Hideout.” Nearby is Loot Rock, where facsimiles of Jesse and his gang divide the spoils of their latest heist. Also included is a “moonshiners’ cave.” The tour climaxes with a light show projecting the Stars and Stripes onto a structure called the Stage Curtain—the largest such formation in the world—while a recording plays of Kate Smith belting out “God Bless America.”

Adjacent facilities include a motel, campground, gift shop, restaurant, and canoe rentals (with shuttle service).

Note on barn painting: Well-informed roadies will know of an attraction near Lookout Mountain, Georgia, which began painting barns back in 1936. Those barns, once numbering about 900, covered 19 states with the “See Rock City” message. Many of those barns remain, and Rock City itself is still going strong.

Very near Meramec Caverns as the crow flies is the much lesser-known Fisher’s Cave (2800 S. Highway 185), on the grounds of Meramec State Park. You’ll need to approach it via Highway 185 from a junction just east of Sullivan. Visitors use handheld lanterns to explore these caves during a ninety-minute tour on paved walkways. This cave is said to have been in use since the 1860s, when then-governor Thomas Fletcher organized a celebration there.

Meramec and Fisher are just the first of several caves that will be within striking distance of Route 66 as we sweep through Missouri. For cavers, Missouri is a paradise. At last count, there were more than 5,400 registered caves in the state.

![]() Leaving Stanton, use S. Outer Road (not Springfield Avenue). The road will hug the interstate all the way to Sullivan, eventually becoming Springfield Road.

Leaving Stanton, use S. Outer Road (not Springfield Avenue). The road will hug the interstate all the way to Sullivan, eventually becoming Springfield Road.

SULLIVAN

George Hearst, whose son, William Randolph, later made his name in the publishing business, was born on a farm near Sullivan. George made his fortune in mining. In the Odd Fellows Cemetery (N. Church Street) is the grave of Jim “Sunny” Bottomley, Hall of Fame baseball player for the St. Louis Cardinals.

![]() Leaving Sullivan, you should be on the south service road of I-44, which will take you through the community of St. Cloud and all the way to . . .

Leaving Sullivan, you should be on the south service road of I-44, which will take you through the community of St. Cloud and all the way to . . .

BOURBON

The town slogan? “Make Our Bourbon Your Bourbon.” The town’s water tower has become a popular photographic subject. Past Bourbon, keep your eye out for what remains of the Bourbon Lodge, a former tourist complex on the southwest edge of town.

A former roadside business, Bourbon, Missouri. GPS: 38.14101,-91.25898

![]() About two-thirds of the way from Bourbon to Cuba, right where the railroad track sidles up close to the south side of I-44 and just east of exit #210, is the site of a town called Hofflins. Although it was a full-fledged town in the 1940s, my 1957 atlas chose to omit it completely. That same atlas shows U.S. 66 in this vicinity, already as a four-lane divided highway. That highway growth, nearly on its doorstep—along with the concomitant traffic—likely made Hofflins unlivable for its residents. Today, little remains.

About two-thirds of the way from Bourbon to Cuba, right where the railroad track sidles up close to the south side of I-44 and just east of exit #210, is the site of a town called Hofflins. Although it was a full-fledged town in the 1940s, my 1957 atlas chose to omit it completely. That same atlas shows U.S. 66 in this vicinity, already as a four-lane divided highway. That highway growth, nearly on its doorstep—along with the concomitant traffic—likely made Hofflins unlivable for its residents. Today, little remains.

After Hofflins, old 66 wanders away from the interstate and towards the town of Cuba.

CUBA

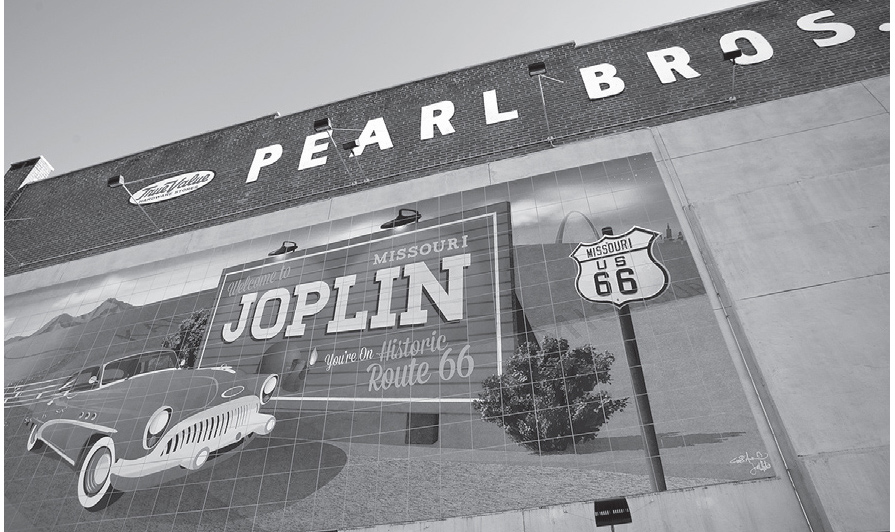

Cuba has adopted the nickname “Mural City,” thanks to more than a dozen outdoor artworks scattered throughout the town. One of those murals adorns the side of a restored Phillips 66 station at the corner of Washington and Franklin Streets. The station is at an intersection known locally as the “Four-Way.” Washington Boulevard is the former U.S. 66, while Franklin Street is Highway 19, the first designated “scenic route” in the state.

The most important feature of Cuba to a Route 66 traveler is the Wagon Wheel Motel (901 E. Washington Blvd.), which is still in operation and looks every bit as inviting as the day it opened for business. If you haven’t stayed in a good old-fashioned mom-and-pop motel yet on this trip, this is an excellent place to do so, since the current ownership has restored it to excellent condition. If you’ll be moving on, then just stay around long enough to snap a few photos and appreciate the one-of-a-kind sign, with its neon-trimmed wagon wheel suspended over the road.

The Wagon Wheel Motel is a truly successful restoration project. Cuba, Missouri. GPS: 38.06450,-91.39576

Downtown Cuba, Missouri. GPS: 38.06287,-91.40358

The Crawford County Historical Society Museum (308 N. Smith St.) occupies a two-story 1934 building across from the library. Just north of town on Highway 19 is the 19 Drive-In Theater, which has been showing films since 1954.

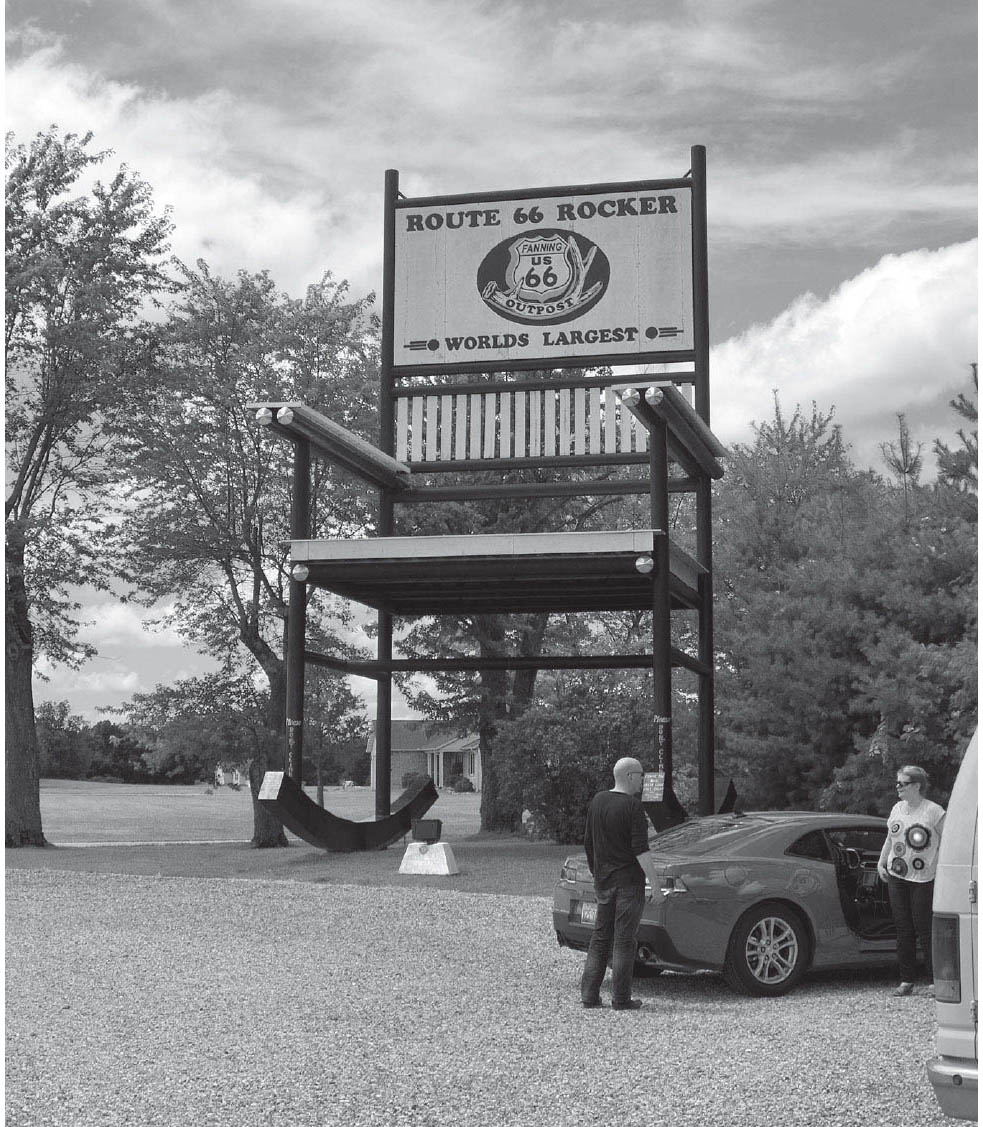

FANNING–ROSATI

West of Cuba, you’ll encounter the small community of Fanning. At the site of the former Fanning US 66 Outpost stands the Guinness-certified World’s Largest Rocker. Constructed in 2008, it is more than forty feet tall, making for an outstanding photo opportunity.

The area around Rosati is known for its grape vineyards. Years ago, the area was thick with vendors offering grapes from small roadside stands. Today, there are a number of operating wineries in the vicinity.

U.S. 66 Outpost & General Store, Fanning, Missouri. GPS: 38.03717,-91.46924

Wine district, near Rosati, Missouri. GPS: 38.02906,-91.53617

ST. JAMES

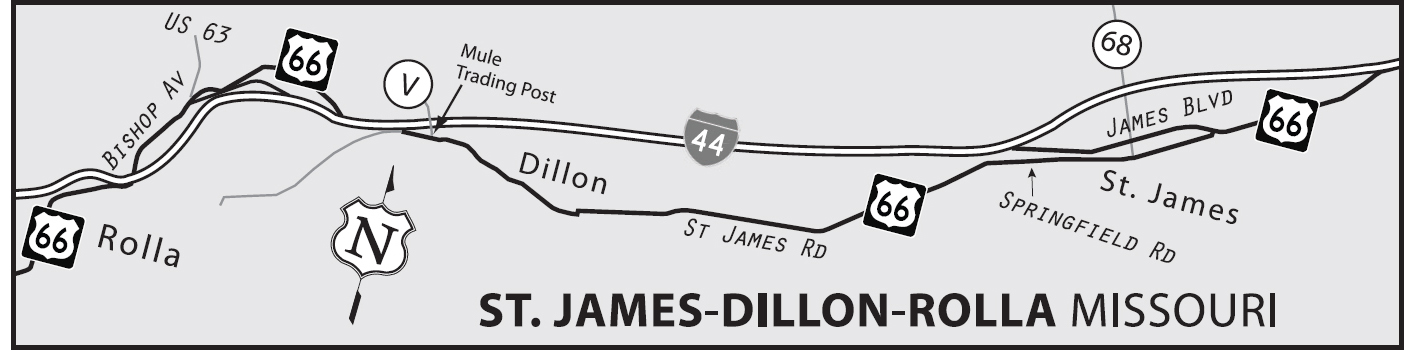

![]()

![]()

Route 66 becomes James Boulevard through town. After exploring St. James, drop down to Springfield Road—the old route toward Dillon and Rolla. Once you reach the Highway V junction, site of the Mule Trading Post, cross to the opposite side of I-44 and use N. Outer Road to continue.

Opened in 2009, the Vacuum Cleaner Museum and Factory Outlet (3 Industrial Dr.) is an offshoot of local vacuum maker Tacony Manufacturing. The museum exhibits models from as early as 1910, and the displays are organized by decade, with carpeting and furniture of each era adding to the atmosphere.

FURTHER AFIELD

About eight miles southeast of St. James, via Missouri State Highway 8, is Maramec Spring Park (21880 Maramec Spring Dr.). Maramec [sic] Spring proper is a National Natural Landmark, and it exudes some 96 million gallons of water each day from the base of a bluff. This spring used to provide the power for the Maramec Iron Works, established circa 1857, the ruins of which can still be seen within the park.

![]() Leave St. James on Springfield Road, which becomes St. James Road as you approach Dillon (see the reference map). As you leave the vicinity of St. James and continue your southwesterly trek across Missouri, you are leaving the Big Prairie section of the state and climbing atop the Ozark Plateau. You will begin to see a change in the topography as you encounter more and more exposed rock outcroppings. The hilly Ozark region, which extends into northwestern Arkansas, is well-known as moonshine territory and home of the Hatfields and the McCoys.

Leave St. James on Springfield Road, which becomes St. James Road as you approach Dillon (see the reference map). As you leave the vicinity of St. James and continue your southwesterly trek across Missouri, you are leaving the Big Prairie section of the state and climbing atop the Ozark Plateau. You will begin to see a change in the topography as you encounter more and more exposed rock outcroppings. The hilly Ozark region, which extends into northwestern Arkansas, is well-known as moonshine territory and home of the Hatfields and the McCoys.

DILLON

South of I-44, Dillon had already been bypassed by 1957 in favor of a faster, four-lane alignment in the corridor now occupied by the interstate. On the opposite (north) side of the interstate, on the frontage road, is Route 66 Motors (12661 Historic Rte. 66). At the time I visited, they had an impressive array of signs on display outside, making for an excellent photo op. Also on hand were gasoline pumps, a power boat, and sundry vehicles in various stages of neglect or restoration.

Route 66 Motors, Dillon, Missouri. GPS: 37.98341,-91.69359

The Mule Trading Post (11160 Dillon Outer Rd.) is still in business near I-44’s Highway V exit. The Mule moved here in 1957 from Pacific. In 2007, the Mule’s proprietors added a giant hillbilly sign with rotating arms.

NORTHWYE

This village did not appear on my 1946 map, but evidently the U.S. 63/66 junction location spurred growth. By 1957, it had been plotted by the cartographers.

ROLLA

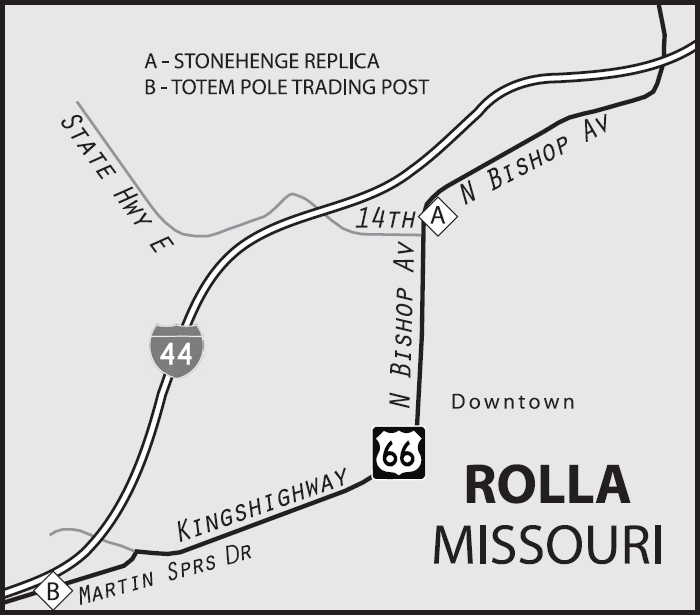

![]()

![]()

Route 66 enters Rolla from the north along U.S. 63/Bishop Avenue, and for most of its life skirted the west edge of downtown. As always, I recommend exploring downtown, which has plenty to offer, before rejoining Bishop Avenue for parts west.

Rolla was named after the North Carolina capital Raleigh, but spelled more phonetically with a Southern drawl. Rolla has a surprisingly active downtown, with the Lambiel Jewelry Store (218 W. 8th St.) and Alex’s Pizza Palace (122 W. 8th St.) keeping things going. It doesn’t hurt that it’s a college town.

Rolla, Missouri. GPS: 37.97807,-91.72170

The Missouri University of Science and Technology (300 W. 14th St.) is proud to be not-your-average university. They have their own mine rescue team and an extensive mineral collection, and they’ve created some works of art using high-pressure water-jet technology, including a scale model of Stonehenge and the Millennium Arch.

ROLLA ATTRACTIONS

The Dillon House (302 W. 3rd St.) is a log structure which served as the area’s first courthouse circa 1857. The logs used are eighteen feet in length. The 1860 Phelps County Jail (500 W. 2nd St.) is on the National Register.

The Totem Pole Trading Post (1413 Martin Springs Dr.) moved to the west side of Rolla more than thirty years ago from its original location near Clementine. The carved totem pole, which used to adorn the roof of the old trading post, is now on display indoors at the present location. The building really doesn’t look anything like what you think of as a “trading post,” with a huge modern overhang sheltering the gas pumps.

![]() Leaving Rolla, you are heading into the heart of Ozark country. Keep an eye out for some curbed sections of the highway as you leave town, heading west on Martin Springs Road (the south interstate service road).

Leaving Rolla, you are heading into the heart of Ozark country. Keep an eye out for some curbed sections of the highway as you leave town, heading west on Martin Springs Road (the south interstate service road).

The Mule Trading Post, on the eastern outskirts of Rolla, Missouri. GPS: 37.97807,-91.72170

Stonehenge replica, Rolla, Missouri. GPS: 37.95638,-91.77655

The Rolla-to-Springfield portion of Route 66 here in Missouri roughly follows the infamous Cherokee Trail of Tears. There were a number of variants on the route of the forced march from Georgia to Oklahoma, and the Northern Route went through this very corridor, circuitous as it may seem. It began in 1838, when a combination of congressional maneuvering, along with some wholesale trickery, led to the expulsion of the Cherokee people from their homes in Georgia. That year, U.S. troops under the command of General Winfield Scott began rounding up men, women, and children and herding them hundreds of miles across the country. As implied by the name, many perished along the way.

Inside the Totem Pole Trading Post, Rolla, Missouri. GPS: 37.94241,-91.79297

DOOLITTLE

Route 66 passes through the town of Doolittle under the name Eisenhower Street.

The town was named for air-racer and World War II hero Jimmy Doolittle of Alameda, California. Doolittle set a world speed record in 1932; ten years later, he led the famous attack on Tokyo and other cities via B-25s that were launched from the U.S.S. Hornet aircraft carrier. That raid, coming as it did only a few months after Pearl Harbor, was a tremendous boost to American morale, and was later dramatized in the film Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, starring Spencer Tracy. Doolittle also served in Italy, Germany, and North Africa during the war.

Doolittle, Missouri. GPS: 37.94028,-91.88171

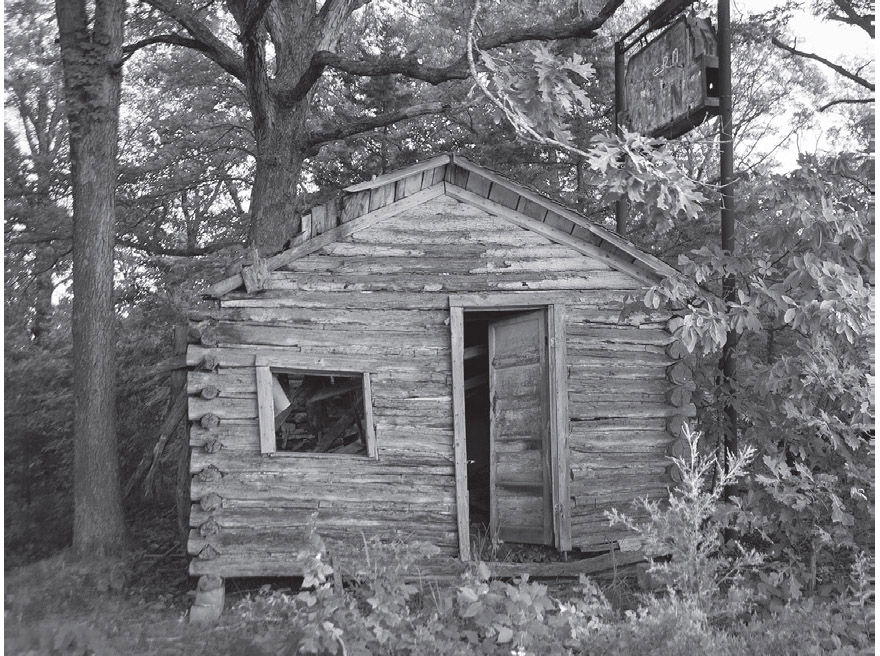

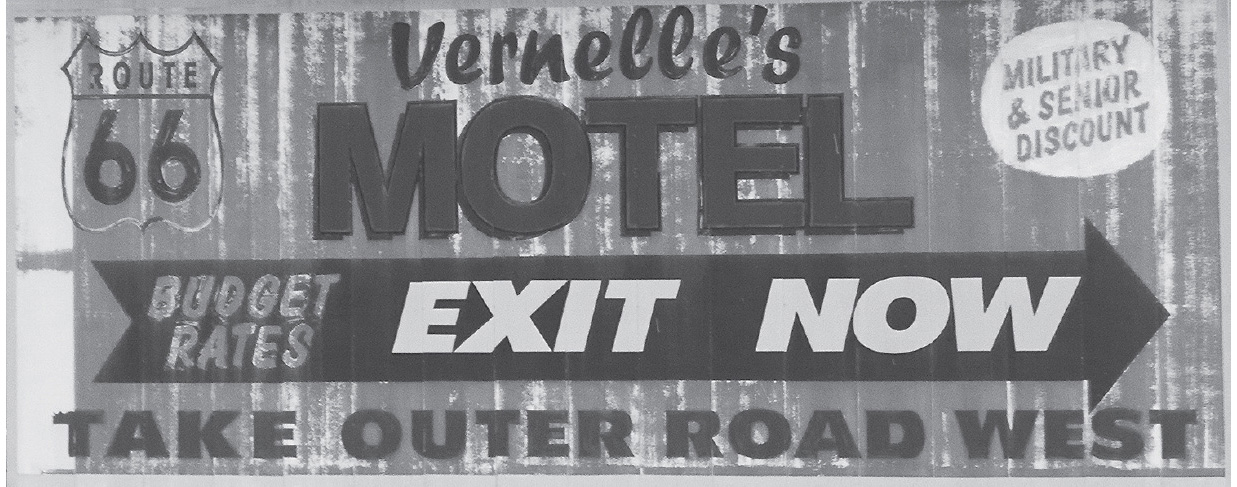

![]() Prior to joining I-44 at interchange #176, you can make a short side trip for something you really should stop and see (refer to Arlington map). John’s Modern Cabins was a tourist abode made up of a set of small wooden cabins. These were some rather primitive accommodations, as evidenced by the remains of an outhouse in the rear. Somewhat ironically, a neon “Welcome” sign glowed in the midst of this rather rustic encampment. A stone’s throw away from the cabins is Vernelle’s Motel (10891 Sugartree Outer Rd.). John’s and Vernelle’s were bypassed many years ago, but a more recent realignment of I-44 isolated them even further.

Prior to joining I-44 at interchange #176, you can make a short side trip for something you really should stop and see (refer to Arlington map). John’s Modern Cabins was a tourist abode made up of a set of small wooden cabins. These were some rather primitive accommodations, as evidenced by the remains of an outhouse in the rear. Somewhat ironically, a neon “Welcome” sign glowed in the midst of this rather rustic encampment. A stone’s throw away from the cabins is Vernelle’s Motel (10891 Sugartree Outer Rd.). John’s and Vernelle’s were bypassed many years ago, but a more recent realignment of I-44 isolated them even further.

Part of the remains of John’s Modern Cabins. These ruins get more dilapidated—and hazardous—with each passing day. GPS: 37.93789,-91.94293

West of Doolittle. GPS: 37.93912,-91.94280

ARLINGTON

On the bank of the Little Piney River, the town of Arlington has been pretty effectively cut off from highway traffic. You might assume that this was a result of the replacement of U.S. 66 by Interstate 44. However, if you read Jack Rittenhouse’s 1946 account of his passage through here, you’ll learn that Arlington had already been cut off by that time, due to earlier construction. Rittenhouse went on to report a rumor that the area had been earmarked for development of a resort, which was never built. Seventy years later, Arlington is a quiet place indeed.

Town center of Arlington, Missouri. GPS: 37.92042,-91.97132

CLEMENTINE

In his notes, Jack Rittenhouse stated that Clementine was “hardly a town,” and it does not appear on my 1946 or 1957 maps of the region (nor does Powellville). At one time, this area was characterized by its numerous basket vendors set up beside the highway. Today, there is little to nothing left of these communities, other than a small cemetery that can be reached by taking Clementine Outer Road east from exit #169.

![]() After Clementine/exit #169, you will need to take Highway Z (south side of the interstate) in order to pass through the village of Devil’s Elbow.

After Clementine/exit #169, you will need to take Highway Z (south side of the interstate) in order to pass through the village of Devil’s Elbow.

DEVIL’S ELBOW

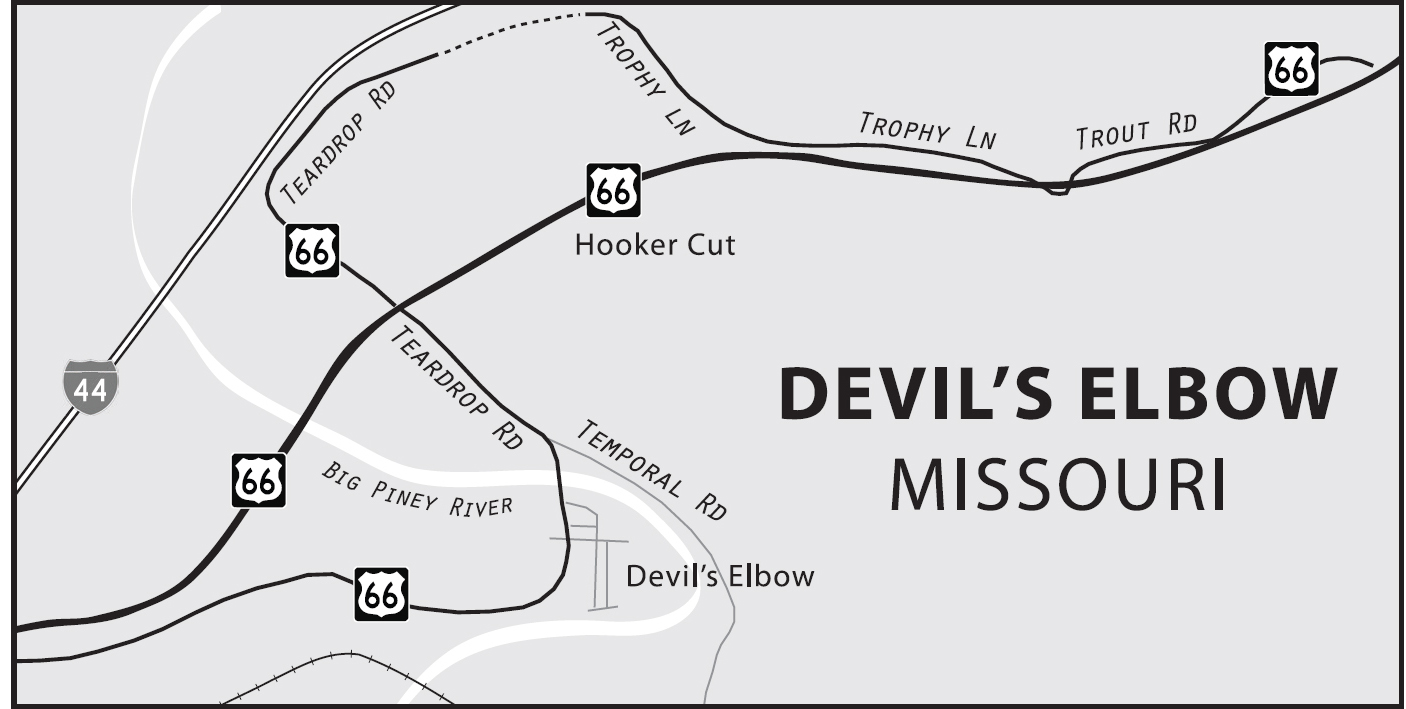

![]()

![]()

The early Route 66 alignment was extremely convoluted, not only at the river crossing itself, but also for much of its eastern approach to the town. Looking at it closely, it’s easy to see why the highway was straightened by construction of the Hooker Cut in order to facilitate the passage of trucks.

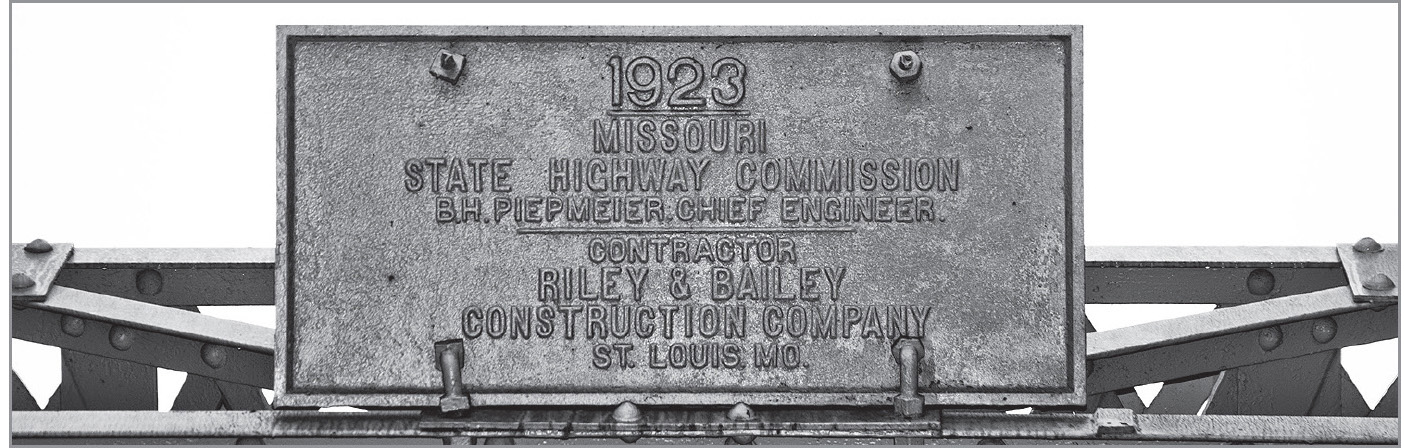

The ominous name of Devil’s Elbow comes not from any highway hazard, but rather from the fact that there is a severe bend in the Big Piney River here, which caused problems for those whose livelihoods depended on the transport of goods up and down the waterway. There is a 1920s-era bridge that crosses the river here, and carried Route 66 traffic in the highway’s early years. However, the narrow bridge and twisting roads in the vicinity were considered a real problem when military material was transported back and forth during the war years, so the highway was re-routed for a straighter course. You can see the wandering course 66 took prior to the war era by looking at the reference map: old 66 followed Trout Road, Trophy Lane, and Teardrop Road to the town of Devil’s Elbow. That had to have been some headache for truck drivers.

Devil’s Elbow, Missouri. GPS: 37.84947,-92.06313

The Munger Moss Sandwich Shop plied its trade here in the town of Devil’s Elbow in the structure that is currently the Elbow Inn (21050 Teardrop Rd.). However, during the highway’s re-alignment in the 1940s, both the town and the restaurant were unceremoniously cut off, and so the proprietors moved to Lebanon and eventually established the Munger Moss Motel there (see page 147).

Detail from the bridge over Big Piney River, Devil’s Elbow, Missouri. GPS: 37.84843,-92.06240

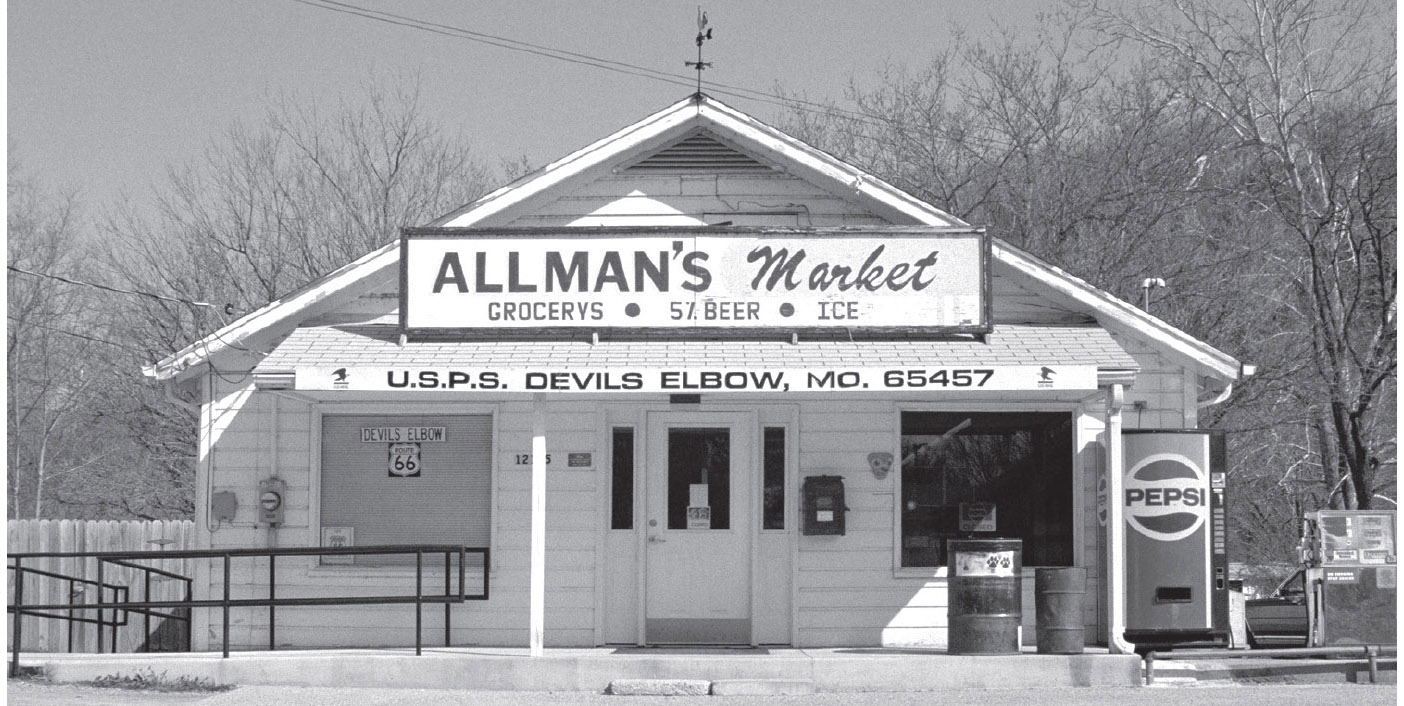

This store has for many years served as the post office for the small hamlet of Devil’s Elbow, Missouri. GPS: 37.84642,-92.06134

Devil’s Elbow has a combination post office and general store that has changed its name over the years from Miller’s, to Allman’s, to Shelden’s (12175 Timber Rd.), but otherwise it has looked very much the same for decades.

![]() Continue on Highway Z (south side of the freeway) to St. Robert.

Continue on Highway Z (south side of the freeway) to St. Robert.

ST. ROBERT

St. Robert is a young community by Route 66 standards, having been chartered in 1951. The town seems to have been engendered by the growth in local population, spurred by the establishment of Fort Leonard Wood during the Second World War. There is a small historical museum in the St. Robert Municipal Center (194 Eastlawn Ave., Suite A).

The Pulaski County Tourism Bureau (137 St. Robert Boulevard, Suite A) has brochures describing three self-guided local driving tours for Fort Leonard Wood, Frisco Railroad, and Route 66.

FURTHER AFIELD

There is a turnoff for Fort Leonard Wood at Spur 44/Missouri Avenue. General Leonard Wood was quite an accomplished officer, and well deserving of having an army post named after him. After the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, then-Colonel Wood and his friend Theodore Roosevelt recruited the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry—the famous Rough Riders—of which Wood was the commanding officer. Meritorious conduct at the battles of Las Guasimas and San Juan Hill gained Wood a promotion to brigadier general. After the war, Wood served as military governor of Cuba from 1899 to 1902. During this time, he oversaw improvements in sanitation, education, and policing. He also served as governor of the Philippines from 1921 to 1927. General Wood even ran for the Republican presidential nomination in 1920, narrowly losing that bid to Warren G. Harding.

East of St. Robert, Missouri, you’ll see this prehistoric creature standing guard at a retail complex. GPS: 37.82940,-92.10516

At Fort Leonard Wood you’ll find the John B. Mahaffey Museum Complex (495 South Dakota Ave.). Included are exhibits honoring the army’s Engineer Corps, Chemical Corps, and Military Police Corps. There is also information about General Wood’s life and career, as well as an area set up as a replica of Fort Leonard Wood as it appeared during the 1940s.

Former hotel and stagecoach stopover, downtown Waynesville, Missouri. GPS: 37.82894,-92.20056

WAYNESVILLE

This town is named after a revolutionary war hero, “Mad” Anthony Wayne. Located just northwest of Fort Leonard Wood, Waynesville was the chief recreational center for troops training there during the war years. During that time, the streets were lined with bars, cafés, and other businesses that young GIs tend to gravitate toward. This was very much in evidence immediately following the war, when our friend Jack Rittenhouse came through here.

During the Civil War, Union troops built a fort overlooking the city in order to protect the telegraph wires between St. Louis and Springfield. There is a historical marker at the fort’s location, on Fort Street between Benton and Dewitt.

At Roubidoux Creek, Route 66 is carried by a five-span concrete arch bridge that was constructed in 1923 (pre-66) and widened in 1939. A large open field near the bridge served as a campsite for the Cherokees during the Trail of Tears march.

WAYNESVILLE ATTRACTIONS

Be on the lookout for Frog Rock (a.k.a. W. H. Croaker) jutting out of a hillside on Route 66, on the eastern outskirts of town. Locals decided that the rock outcropping looked a lot like a frog, so it has been painted very nicely now to really look like a frog.

The Old Stagecoach Stop (105 N. Lynn St.), a two-story station that has also served as a wartime hospital and a hotel during its 140-year history, is on the National Register.

The Pulaski County Courthouse Museum (123 N. Benton St.) is located within the town’s 1903 courthouse. The museum’s themes include the Civil War, Trail of Tears, pioneer history, and Route 66. Open Saturdays in the town square.

The Talbot House (405 North St.) is one of the oldest in town. It now houses an antiques shop, so you don’t need to come away from your tour empty-handed.

![]() After Waynesville, the highway is now marked Highway 17. Stay with it all the way to Buckhorn.

After Waynesville, the highway is now marked Highway 17. Stay with it all the way to Buckhorn.

BUCKHORN–LAQUEY–HAZELGREEN

![]()

![]()

At Buckhorn, continue following Highway 17, which crosses here to the south side of I-44.

Here in Buckhorn, Historic 66 crosses I-44 (at exit #153) under the guise of Highway 17. Buckhorn was named after the Buckhorn Tavern, a former stage stop on the old Wire Road, which displayed a set of antlers. Between here and the Highway 133 junction is an area called Gascozark. That name was coined by a developer in the 1920s, and is a hybrid derived from Ozark and Gasconade (for the nearby river). The old Gascozark Trading Post still stands, neglected and overgrown, near where Highway 133 crosses I-44, including some former tourist cabins. West of Hazelgreen, Route 66 crosses the Gasconade River on a steel bridge constructed in 1922 (south of I-44).

Buckhorn, Missouri. GPS: 37.78607,-92.26871

IMPORTANT NOTE: Recently, Missouri highway authorities closed the Route 66 bridge crossing the Gasconade River west of Hazelgreen, perhaps permanently. Therefore, you’ll need to cross to the north side of the interstate at exit #145/Highway 133 to continue your journey west. You’ll miss some authentic Route 66 miles unless you do some backtracking. Your next opportunity to return to 66 will be crossing to the south side of I-44 at exit #140. Then you’ll need to cross again to the north side of the freeway at exit #135 for the run into Lebanon.

Bridge over the Gasconade River, east of Lebanon, Missouri. GPS: 37.75961,-92.45134

LEBANON

Lebanon is home to the Munger Moss Motel (1336 Historic Rte. 66), which has a huge, red, porcelain-and-neon sign out front that was manufactured just a little up the road by a firm named Springfield Neon. If you’ll be staying the night in the Lebanon area, I highly recommend you do so here at the Munger Moss. The owners really care about Route 66 and roadies like you and me. The lobby is also a combination gift shop and vintage toy display.

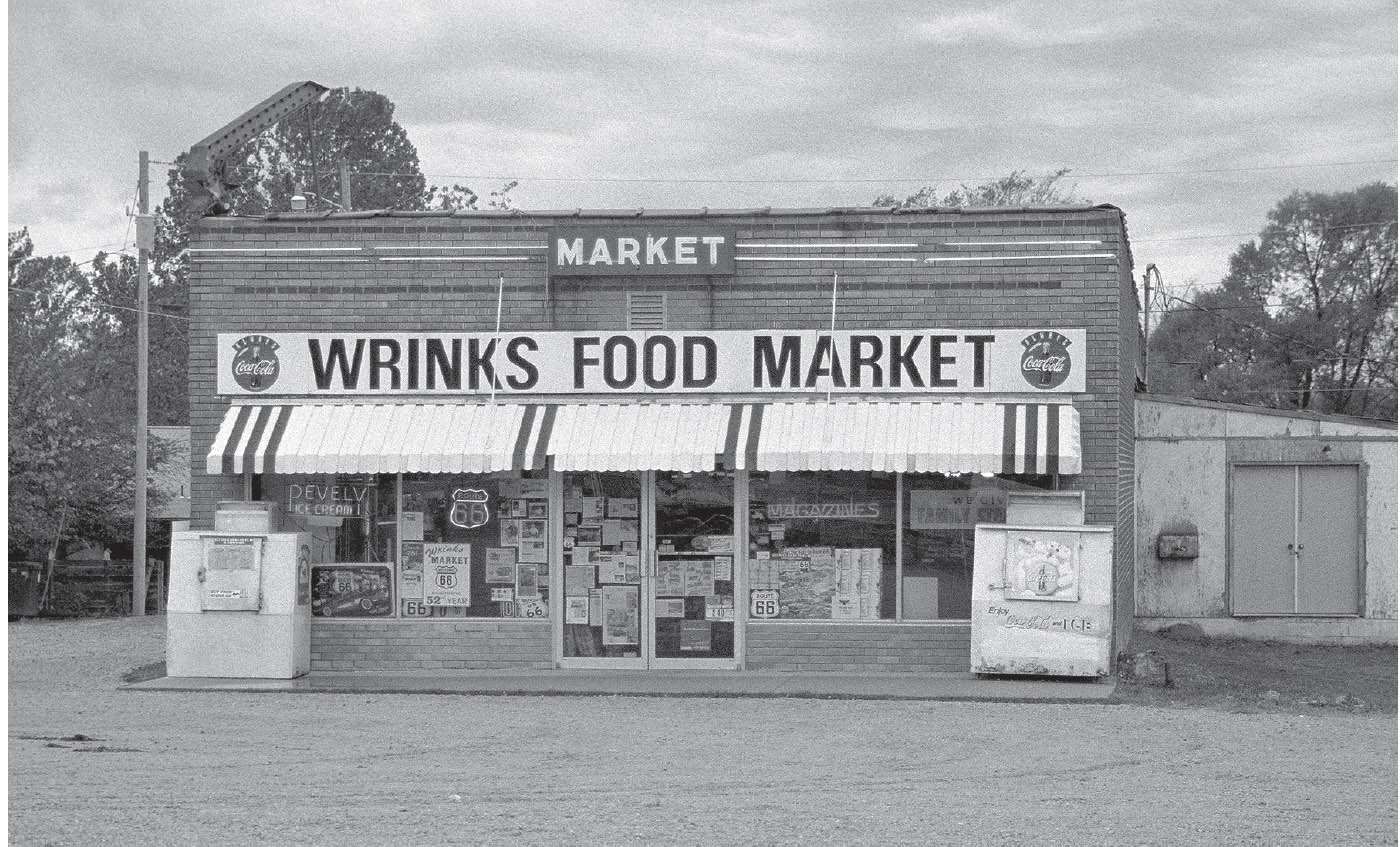

Not far from the Munger Moss is Wrink’s Market. Unfortunately, Glenn “Wrink” Wrinkle passed away in 2005. Wrink started operating the market in 1950, and kept it open until only a few weeks before his death fifty-five years later. After sitting idle for a time, the store was reopened by Glenn’s son Terry, but it has since closed again, likely indefinitely.

Opened in 2004, the LaClede County Library houses a great Route 66 Museum (915 S. Jefferson Ave.) run by the Lebanon/LaClede County Route 66 Society. The old LaClede County Jail (262 N. Adams Ave.) is on the National Register.

FURTHER AFIELD

North of Lebanon (about twenty-five miles) via Highway 5 is Camdenton. A nearby park, Ha Ha Tonka State Park (1491 State Rd. D), includes the remains of a 100-year-old European-style castle. In 1905, a Kansas City businessman named Robert Snyder began construction of a three-story stone castle on 2,500 acres of land that he had acquired for its natural beauty. He intended to create a retreat that would rival any in the world and spared no expense in its creation, hiring the most qualified artisans and obtaining the best materials available. Tragically, Snyder died suddenly in 1906, and the unfinished project was taken over by his sons. The property eventually included the castle, an eighty-foot water tower, stables, and several greenhouses. In later years, the family came upon hard times and was forced to lease the property to someone who operated it as a hotel for some years. In 1942, more tragedy struck when a spark from a fireplace spread rapidly and gutted both the main house and the stable. Those ruins now stand stark and haunting atop a 250-foot bluff overlooking the Lake of the Ozarks.

The Munger Moss Motel is a place every Mother Roader should plan to stay the night sometime. Lebanon, Missouri. GPS: 37.68652,-92.63994

The former Wrink’s Market in Lebanon. GPS: 37.68497,-92.64254

Lebanon, Missouri. GPS: 37.68389,-92.64865

The centerpiece of Ha Ha Tonka State Park is this stone ruin. Near Camdenton, Missouri. GPS: 37.97630,-92.76960

The state of Missouri purchased the estate in 1978 and opened it to the public as Ha Ha Tonka (“Laughing Water”) State Park. The park’s beautiful natural features confirm Mr. Snyder’s good taste in obtaining the property. Today, park visitors can enjoy sinkholes, caves, a natural bridge, springs, and, of course, the famous ruins via some fifteen miles of trails. The trails run the gamut from paved, “accessible” paths and boardwalks to strenuous, rocky climbs suitable for overnight backpacking. Some of the caves here—like many others throughout Missouri—are said to have been used as hideouts by criminals during the 1830s. The Ha Ha Tonka visitor center features a relief map of the area carved from a block of stone.

![]() Back on 66: From Lebanon, take Highway W (west side of I-44) to Phillipsburg.

Back on 66: From Lebanon, take Highway W (west side of I-44) to Phillipsburg.

PHILLIPSBURG–CONWAY–SAMPSON–NIANGUA

![]()

![]()

Cross to the south side of I-44 at Phillipsburg (exit #118) and join Highway CC (see the reference map).

According to a 1946 oil company road map of Missouri, Conway and Sampson were both Route 66 towns strung between Phillipsburg and Marshfield, with 66 just barely missing Niangua. Since the railroad tracks pass directly through the heart of Niangua, it seems likely that, originally—in the 1920s or ’30s, perhaps—the early Route 66 did take in Niangua. By 1957, however, a new four-lane alignment had been constructed that bypassed all of these towns by a few miles and occupied the present-day I-44 roadbed through the region. By then, the village of Sampson was no longer deemed worthy of any mention at all. All of these towns are still there, but you’ll have to make a greater effort if you intend to see them (see the reference map).

Alongside I-40, near Phillipsburg, Missouri. GPS: 37.56701,-92.77635

Phillipsburg, Missouri. GPS: 37.55545,-92.78909

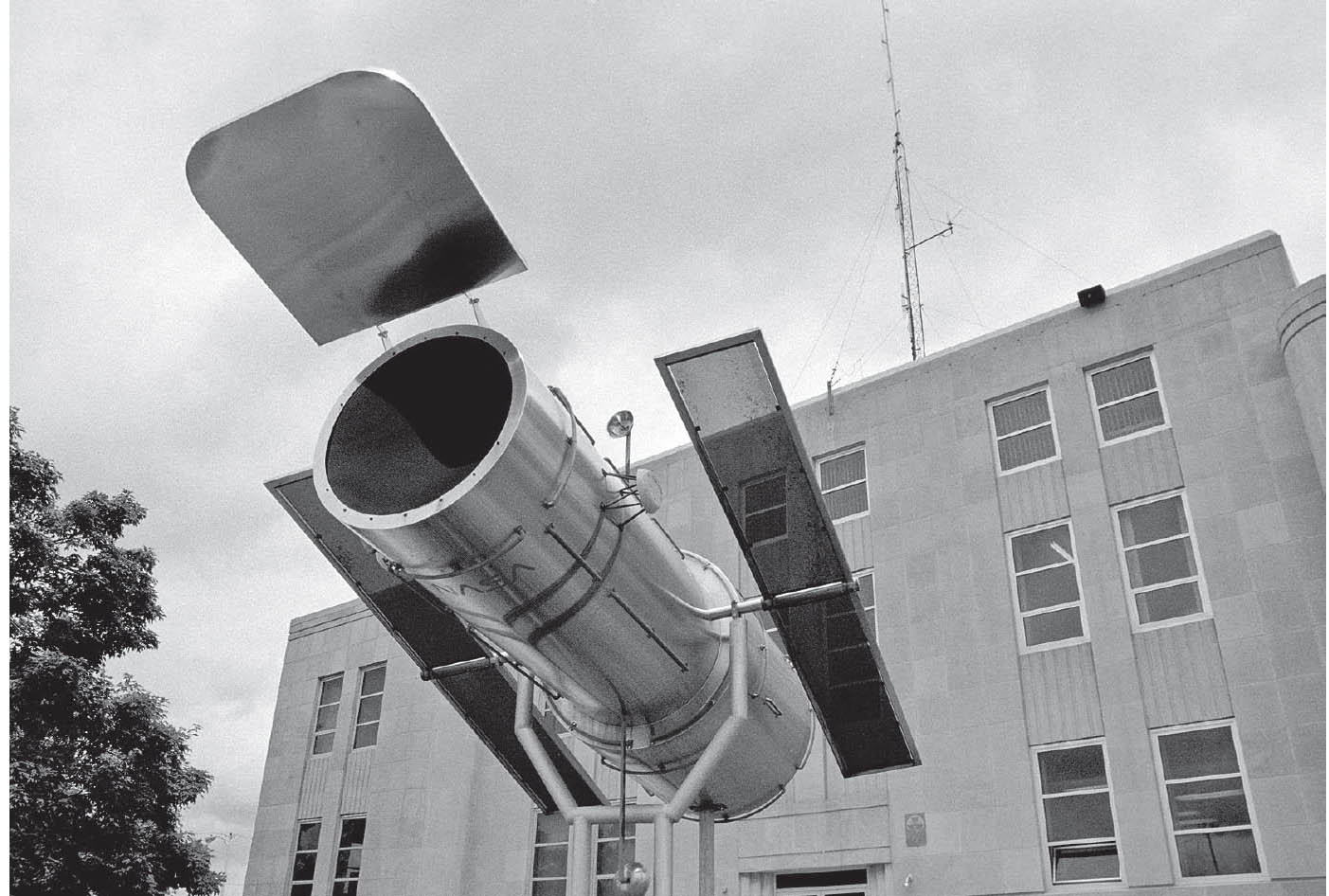

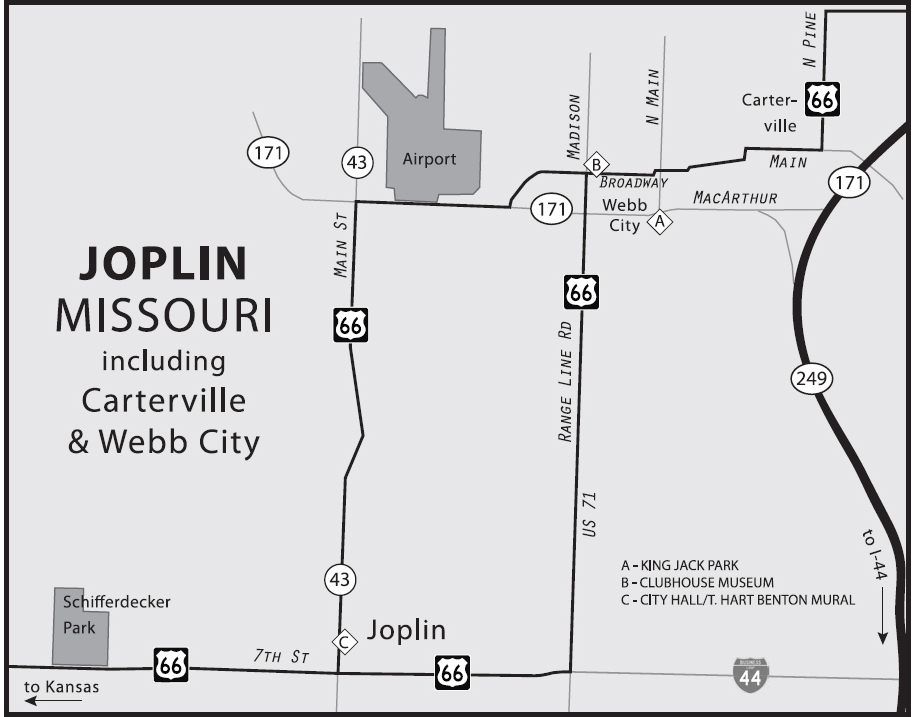

MARSHFIELD

Marshfield is the hometown of Edwin Hubble, creator of the Hubble Space Telescope. The town has a one-quarter-sized replica of the telescope occupying the west side of the lawn at the Marshfield Courthouse (140 S. Clay St.). Nearby is the Webster County Historical Museum (219 S. Clay St.), housed in the old community library that was funded by the Carnegie Foundation in 1911. Outside the museum is a “Walk of Fame” honoring prominent citizens of Missouri.

County courthouse, Marshfield, Missouri. GPS: 37.33846,-92.90717

Hidden Waters Nature Park (716 W. Hubble Dr.) includes springs that form the headwaters of the Niangua River and walking trails that pass other water features, as well as an assortment of gardens. In the park you’ll also find the Callaway Cabin, which dates from 1853 and was one of the few structures to survive the tornado that struck the area in 1880.

![]() Leave Marshfield on Highway OO toward Strafford.

Leave Marshfield on Highway OO toward Strafford.

HOLMAN–STRAFFORD

East of Strafford, near the small hamlet of Holman, is the Wild Animal Safari (124 Jungle Dr.), one of those zoological parks you can drive through in your car and view hundreds of animals in captivity—some of which may not even know that it is they, and not you, who are in the lockup. Denizens of this paradise include bison, llamas, and zedonks (zebra-donkey hybrid). Unlike most zoological parks of one kind or another, you are not forbidden to feed the animals here. In fact, there is animal feed for sale that you can toss out of your car to entice the animals to approach you. There are also paddle boats and a petting zoo.

![]() Leave Strafford on Highway 125, paralleling the railroad tracks.

Leave Strafford on Highway 125, paralleling the railroad tracks.

SPRINGFIELD

![]()

![]()

There are multiple Route 66 alignments, so exploration is strongly encouraged. The best-known versions enter Springfield on Kearney Street, turn south on Glenstone, and then head west again after turning onto either Chestnut or St. Louis. Both will take you through the heart of downtown. A later bypass routing continues further west on Kearney before turning south, thus avoiding downtown traffic. There are still a number of classic motels and other vintage businesses to excite your senses. Among the motels are the Rest Haven, Skyline, and Rail Haven, to name only a few.

Established in the 1820s when pioneer John Polk Campbell carved his initials in a tree near the confluence of four springs, and soon thereafter known as the Queen of the Ozarks, Springfield won’t disappoint the Route 66 traveler. Upon your arrival, be sure to stop by the Route 66 Visitor Center (815 E. St. Louis St.).

Springfield has a special distinction. It was here, in 1947, that Red Chaney opened the first hamburger stand with a drive-thru window: Red’s Giant Hamburg. In 1982, a song was written about the place called “Red’s” that was recorded by a Springfield band called the Morells. A photo of Red’s even appeared on the album cover. Red eventually retired, though, and his landmark was demolished in the 1990s, with more than a few nostalgic souls turning out for the occasion. Today, Birthplace of Route 66 Roadside Park (College St. and S. New Ave.) is the town’s tribute to Red’s.

The eastern outskirts of Springfield, Missouri. GPS: 37.23933,-93.23490

Another business originating here in Springfield was Campbell’s 66 Express, the trucking firm which used Snortin’ Norton, the “Humpin’ to Please” camel, as its trademark.

The Steak ’n Shake restaurant chain still has a sizable presence in Missouri, and in Springfield in particular, a number of the earlier restaurants still remain. The chain’s famous directive to “Take Home a Sack” (modified to “Takhomasak”) has been echoed many times over by famous burger chains nationwide: White Castle’s “Buy ’Em by the Sack,” White Tower’s “Buy a Bag Full,” and Krystal’s “Take Along a Sack Full” all encourage us to indulge the same impulse. The Steak ’n Shake flagship restaurant (1158 E. St. Louis St.) will make you think you’ve time-traveled to 1960.

As you pass through town on what is now College Street, be on the lookout for a small embankment beside the road adorned with a Route 66-themed mosaic. The artwork was created by local artist Christine Schilling with the help of some young students. In 2010, Schilling began restoration of an advertising mural in downtown Springfield that was partially exposed when a vehicle collided with the building. The ad touts Beeman’s Pepsin Gum (305 E. Commercial St.).

Springfield, Missouri. GPS: 37.20879,-93.32302

ED GALLOWAY

Nathan Ed Galloway was born in 1880 in Stone County, near Springfield, Missouri. From a very young age, he showed a talent and propensity for wood carving.

In 1898, Ed joined the U.S. Army and served in the Spanish-American War before being assigned to duty in the Philippines. While there, he came into contact with creatures such as crocodiles and other reptiles that would inspire some of his later art.

After leaving the army, Ed returned to Springfield and pursued his wood carving. He specialized in household objects such as hall trees and smoking stands, which he covered with intricate carvings of animals and other figures. He also fashioned many large-scale items from tree trunks; these, too, were often decorated with human and animal figures.

Ed planned to be an exhibitor at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, taking place in 1915. Tragically, a fire at his studio destroyed most of his work. Ed managed to salvage a few pieces, including his sculpture known as Lion in a Cage, and began making his way west toward California for the exposition. It is said that he had been temporarily waylaid in Tulsa, Oklahoma, when his work was seen and admired by Charles Page. Page was a businessman and philanthropist who had established a home for orphaned children in nearby Sand Springs. He offered Ed a job teaching woodworking to the boys at the Sand Springs home, and Ed remained in Sand Springs in that capacity for the next twenty-plus years.

From 1936 to 1937, Ed and his wife, Villie, bought several acres of land near Foyil, Oklahoma (Villie was from the Bushyhead area), and began the chapter of his life for which he is best known. He began building a stone residence on the property (completed in 1937), as well as a collection of large American Indian-inspired structures. The largest of these structures is a ninety-foot-tall totem pole bearing the date 1948, which took him eleven years to complete.

During this time, Ed also constructed his “Fiddle House,” an eleven-sided building created expressly to house the growing collection of fiddles he carved. That collection is said to have exceeded 300.

Ed seems to have been speaking to Mother Road lovers such as you and me when he said: “All my life, I did the best I knew. I built these things by the side of the road to be a friend to you.”

Ed died of cancer on November 11, 1962 (Veterans Day). His Foyil property was donated by his family in 1989 to the Rogers County Historical Society, which maintains the present-day Totem Pole Park (see page 202).

SPRINGFIELD ATTRACTIONS

Springfield is widely known as the home of Bass Pro Shops Outdoor World (1935 S. Campbell Ave.), a veritable theme park of a retail experience for the outdoor set. There’s a 140,000-gallon game fish aquarium and a four-story waterfall. If that’s not enough, check out the stuffed and mounted bears, antique fishing gear, and wildlife art gallery.

Next door to Bass Pro Shops is World of Wildlife (500 W. Sunshine St.), featuring a myriad of authentic wildlife habitats, such as aquariums, aviaries, and even a swamp area.

The Rest Haven Motel in Springfield, Missouri, sports a huge neon sign in excellent condition. GPS: 37.23984,-93.25612

The Typewriter Toss is held each April on Secretaries Day—just in case you thought that was a “holiday” you could live without. On this day, typewriters are thrown at a bullseye from a height of fifty feet.

If pioneer history interests you, check out the Gray-Campbell Farmstead (2400 S. Scenic Ave.) in Nathanael Greene Park. Centered around the oldest house in Springfield (circa 1856), the farmstead features a log kitchen, two-crib barn, family cemetery, and Civil War-era artifacts. There are costumed docents on hand to explain the history of the place. Also at Nathanael Greene Park is the Mizumoto Stroll Garden, with over seven acres of lakes, winding paths, and other traditional features of Japanese-style gardens.

At the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame (3861 E. Stan Musial Dr.), you’ll become acquainted with some of the great names that have called the Show-Me State home base: Stan Musial, Whitey Herzog, and Bob Gibson, to name only a few. There’s even a cage where visitors can stand behind home plate while 100-mph fastballs come blazing in from the mound.

Springfield, Missouri. GPS: 37.20885,-93.32372

The History of Hearing Museum (628 E. Commercial St.) will take you back to the days of handheld ear trumpets, and explains how the evolution of hearing-aid technology has improved lives.

The restored Jefferson Avenue Footbridge (Commercial St. and Jefferson Ave.) was built in 1902, and is a favorite train-watching spot, passing as it does over several sets of tracks. Locals consider the footbridge, which is more than 500 feet in length, to be their largest public sculpture. In fact, it’s the longest footbridge in the entire country.

The Railroad Historical Museum (1300 N. Grant Ave.) preserves railroading heritage with several different types of railcars on display. Opportunities for kids include exploring a locomotive cab and ringing the bell.

Pythian Castle (1451 E. Pythian St.) was originally constructed by the Knights of Pythias in 1913 as an orphanage. It was commandeered for use by the U.S. Army during World War II, and is said to be haunted. Tours are available of the 55-room, 40,000-square-foot castle, and special events are held there frequently. The Calaboose (409 W. McDaniel St.) was built in 1891 as a jail, but now serves as a police substation with a law enforcement museum on the first floor.

Askinosie Chocolate (514 E. Commercial St.) makes chocolate, white chocolate, and cocoa butter from scratch (cocoa beans!). The building itself dates from 1894, and previously saw action as a carriage factory. Tours of the factory are available for a small donation. Military memorabilia abounds at the Air and Military Museum of the Ozarks (2305 E. Kearney St.), including restored aircraft, a variety of military vehicles, dioramas, and flight simulators. You can even have your own personalized dog tags made.

Civil War buffs will want to visit General Sweeney’s Civil War Museum (5228 S. State Highway ZZ). An official site of the Civil War Trust, it’s the only museum to focus on the trans-Mississippi portion of the conflict, and houses more than 5,000 wartime artifacts.

FURTHER AFIELD

Just northwest of Springfield, you’ll find Fantastic Caverns (4872 N. Farm Rd. 125). Acclaimed as “America’s Only Drive-Thru Cave,” the tour takes visitors along the path of an underground river in Jeeps, while the guides extol the considerable virtues of protecting the environment by powering the tour vehicles with propane. Furthermore, the cave was once owned by the Ku Klux Klan, which held meetings in one of the caverns here.

In contrast to the above, due north of Springfield via Highway H is Crystal Cave (7225 N. Crystal Cave Ln.). Here, the operators have endeavored to provide a cave experience in a more natural state. There are no vehicles; instead, visitors clamber about on narrow paths and must negotiate tight spaces. Unusual features include Rainbow Falls, the Cathedral, fossil crinoids, and numerous American Indian symbols.

The town of Marionville, southwest of Springfield on U.S. 60, has a reputation for albino squirrels. Keep your camera ready.

To the south of Springfield, via U.S. 65, is the town of Branson. Though considered a tad overblown by many, Branson does have at least one redeeming feature: the Branson Scenic Railway (206 E. Main St.). The restored Ozark State Zephyr plies the area and hearkens to the passenger service glory days of the 1940s and ’50s.

To the northwest of Branson, via Highway 76, is a semi-Christian theme park called Silver Dollar City (399 Silver Dollar City Pkwy). The park sprang up due to the presence of nearby Marvel Cave, a subterranean attraction in the area since 1950. The theme park was officially established in 1960, and then received some additional notoriety when a few episodes of the Beverly Hillbillies television series were filmed there in 1967.

West of Springfield, Missouri. GPS: 32.21130,-93.48230

![]() Head west out of Springfield on the Chestnut Expressway (Highway 266), which is Historic 66.

Head west out of Springfield on the Chestnut Expressway (Highway 266), which is Historic 66.

PLANO

In this vicinity is a masonry building (S. Farm Rd. 45) just a few feet from the edge of the highway that has been taken over by vines and other vegetation. The interior is completely gutted and roofless. Inside, many small trees are growing, reaching for the windows and the sky.

Former casket-making shop, near Plano, Missouri. GPS: 37.19282,-93.55078

If you have a detailed map of this region, you can see that the later version of Route 66 (present-day Highway 266 from here to Paris Springs, and Highway 96 from Spencer to northeast of Carthage) were each plotted as nearly a straight line over the next forty miles or so.

HALLTOWN

Established in 1833 and later named after merchant George Hall, Halltown is known for its antique shops, the largest of which is Whitehall Mercantile (100 N. Park Dr.). Amazingly, back in 1946, Jack Rittenhouse characterized Halltown by making mention of its antique shops.

Halltown, Missouri. GPS: 37.19343,-93.62679

PARIS SPRINGS–SPENCER–HEATONVILLE–ALBATROSS–PHELPS

Don’t fail to stop at the Gay Parita station (21118 Historic Rte. 66) in Paris Springs; it’s pretty special.

Coming up is one of my favorite stretches of old Route 66. Ahead of you now is a string of very small towns stretching between Halltown and Carthage. Due to highway realignments, traffic was diverted south of here, pulling the lifelines from towns such as Albatross and Phelps. As a result, they became almost frozen in time.

Gay Parita station, Paris Springs, Missouri. GPS: 37.19430,-93.67919

As you pass through this section, I urge you to slow down considerably. Take your time exploring the communities of Paris Springs, Spencer, Heatonville, Albatross, and Phelps. You will see the ruins of convenience stores, tourist courts, and other structures, many of which look as though the owners left suddenly and never returned. You will also see some structures that have been assigned to new uses, such as a set of tourist cabins now being used as storage sheds.

Spencer, Missouri. GPS: 37.18444,-93.70272

This tiny station in Phelps, Missouri, has since been demolished. GPS: 37.19011,-93.90216

RESCUE–PLEW–AVILLA

Between Rescue and Plew is a turnoff (YY North) to Red Oak. This reference will be more meaningful a short time later, when you encounter the turnoff for Red Oak II just outside of Carthage. Avilla has a deteriorating business district, but also some unexpected Route 66 spirit.

Avilla, Missouri. GPS: 37.19553,-94.12869

Avilla, Missouri. GPS: 37.19555,-94.12978

FURTHER AFIELD

You won’t find this town on a road map, but here it is anyway, created by a local artist northeast of Carthage. Red Oak II (County Loop 122) is a village—partly the original Red Oak—that was brought over from its original location more than twenty miles away and installed here, presumably to attract nostalgia-minded travelers—and it keeps growing. It features a multitude of vintage structures, including a blacksmith shop, diner, general store, church, a couple of filling stations, and several residences, both occupied and otherwise. There’s even a mock cemetery.

Part of the art-inspired community of Red Oak II, Missouri. GPS: 37.21273,-94.27704

CARTHAGE

![]()

![]()

You can head into Carthage on current Highway 96 to Central Avenue, but there’s an older alignment to the left (see the reference map) that wanders to the eastern side of Kellogg Lake and includes some old tourist courts. For a time, that alignment then proceeded west on Java Street before joining Garrison north of town.

The famed Carthage marble is quarried in this town, and more than a few Carthaginians have made their living in the field. Stop at the Carthage Chamber of Commerce (402 S. Garrison Ave.) for information about a home tour that begins and ends at the Jasper County Courthouse in the square and takes you on a drive to see the homes of several of Carthage’s most prominent citizens. Constructed between 1870 and 1910, many of these residences were built by stone quarry and mine owners.

The Jasper County Courthouse (302 S. Main St.) itself was constructed in 1894–1895. There is a mural inside depicting the history of the area, painted by a local artist. In 2009, a Route 66 display was added that loosely resembles the former Boots Drive-In (see the reference map). The courthouse also features a wrought-iron, cage-style elevator that is still in operation. Take a stroll around the town square, which is lined with buildings dating from as early as the 1870s.

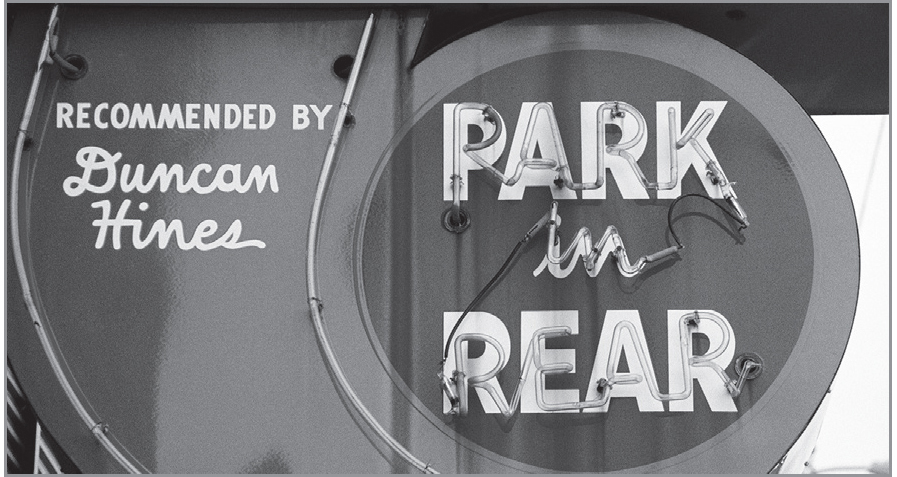

For a reminder of authentic Route 66, the Boots Court Motel (107 S. Garrison Ave.) is hard to beat. According to a local tourism brochure, Clark Gable once stayed at the Boots, in room 6. There used to be a Boots Drive-In & Gift Shop across the street in the streamlined building now housing a bank.

Boots Motel, Carthage, Missouri. GPS: 37.17844,-94.31403

CARTHAGE ATTRACTIONS