CHAPTER SIX

The Economic Revival

The history of the Mediterranean in the last three centuries BC is dominated by the rise of the Roman Empire. With the final defeat and destruction of Carthage, the way lay open for the piecemeal annexation of the remaining littoral parts of the west Mediterranean, until the circle was completed in 125–120 BC by the incorporation of southern France, linking Spain with northern Italy. But this process was not without its setbacks, one of which was administered from north of the Alps—the invasion of the Cimbri and Teutones into northern Italy at the end of the second century BC—which led directly to the reorganisation of the Roman army on more professional lines by Marius. But this invasion was unconnected with the earlier Gallic invasions. It emanated from the north European Plain, and rather marked a new phase of migration that was mainly to affect central Europe a century later.

The Italian political dominance was accompanied by industrial dominance as well, by Campania, and to a lesser extent Etruria. During the second century, wine amphorae produced in this area, the Dressel Ia form, gradually replaced those from the east Mediterranean from Cos and Rhodes. It was presumably Campanian and Tuscan wine that was transported in them, exported through ports such as Pompeii and Cosa. These amphorae, which first appear at Carthage in contexts predating 150 BC, by the beginning of the first century virtually held a monopoly in the trade with southern France.

Central Italy also was the main source of the fine wares traded in the west Mediterranean. The black slipped table wares, generally termed ‘Campanian’, may have been produced elsewhere as well, but Campania was certainly the main source. They were mass-produced in standardised forms, turned on the wheel, but employing moulds or templates. Ornamentation however is limited generally to simple stamped decoration such as palmettes, which means they are more difficult to date than their Corinthian and Attic predecessors. Production was certainly underway in the fourth century BC, and continued until about 20 BC, when the market was taken over by the red-gloss wares of Arrezzo in Etruria. These latter show a new level of enterprise with factories organised along capitalist lines, but it is unlikely that the Campanian production was at more than an artisan level.

In the first century this virtual monopoly was extended to bronze vessels as well, and a range of products appeared which achieved the same prestige and even more extensive distribution than the fifth-century Etruscan products. Most were associated with wine drinking: handled flagons, ladles and mixing pans and bowls, which commonly appear with amphorae in graves. Their chronology is difficult to sort out: production was certainly underway by the mid-first century, but may go back to the end of the previous century; and it continued until the decade 20–10 BC, when new types appeared.

In other respects, however, the development of economic institutions in Italy may have been somewhat backward, especially in the case of coinage. The Greek colonies were among the earliest producers of coins, and some issues still rank among the finest ever struck. But the western colonies generally did not follow Athens in the production of low-value coins in bronze; and for as long as only silver or gold was struck, the growth of market exchange must have been inhibited. Rome did not start low-value bronze production until the principate of Augustus in about 30 BC (it had earlier produced large bronzes), and even then it was Nîmes and Lyons in southern France that were the main mints. Gaul had been producing bronze coinage for at least a generation before this, and may well have been more advanced than Rome in its coin usage, but for some time to come much of the economy must still have been embedded in the social structure.

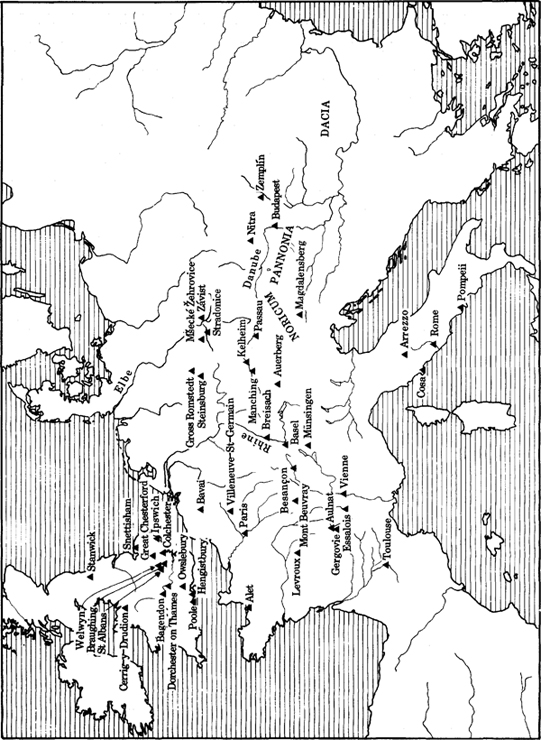

40 Sites mentioned in Chapters 6 and 7

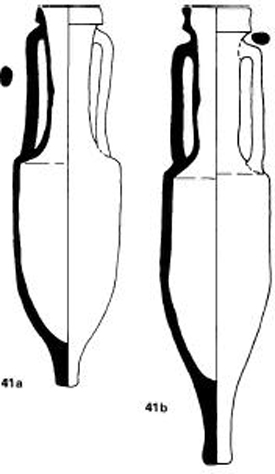

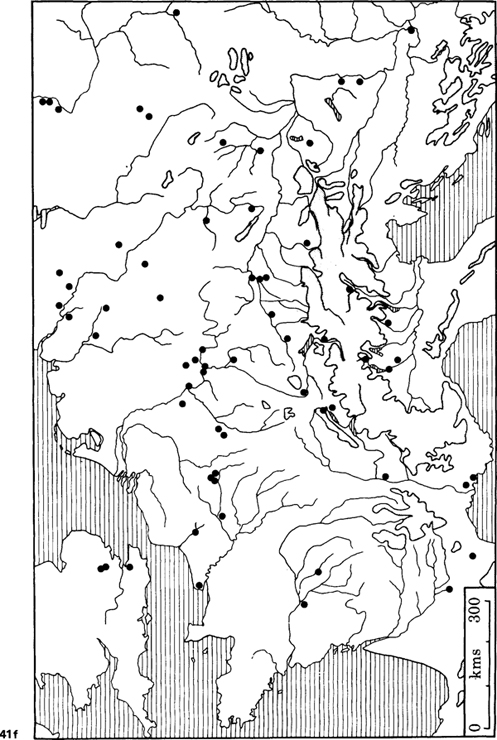

41 Italian traded goods, 2nd-1st century BC

The most common imports from the Mediterranean into western Europe in the late La Tène are wine amphorae from the west coast of Italy. Fabric analysis shows that they came from a variety of sources, mainly shipped through the ports of Cosa and Pompeii. Two principle forms can be distinguished: a smaller one with a triangular rim, Dressel Ia (a); and the taller Dressel Ib with elongated rim (b). The difference is chronological. Ia is found in deposits at Carthage at about 150 BC, and continues until about 50 BC when it is replaced by Ib, which is the typical form of the second half of the first century BC. Some are stamped with the producer’s or exporter’s mark, the most common being s or SES with an anchor (c), an abbreviation of Sestius, the name of one of the leading families of Cosa.

Accompanying the wine were sets of bronze drinking vessels, the most common being the jug (d) of which there is an early ‘Kelheim type’ belonging to the first half of the first century BC, and a later ‘Kaerumgaard type’. Equally common is a handled pan named after the burial at Aylesford (e). The amphorae are mainly known from site finds, and have a westerly distribution because of the ease of transport by sea and river; the bronze vessels were more easily transported over the Alps, and occur not uncommonly on oppida in central Europe, and in burials in France, England and on the North European Plain (f).

In addition to these imports there are fine black-slipped vessels, also probably from Campania. These did not reach such a wide area, but are common in central and southern France, and occasionally they reached the Rhine. The bowls (g) and plates (h) were quickly imitated in central France, and provided the antecedents for the red-slipped samian wares of Arrezzo and southern France which largely replaced them after 20 BC.

Scales: a, b—1:10; c—1:1; g, h—1:2; d, e—1:3

Image rights not available

42 Gallic coinage and its Greek prototypes

Coinage became widely used in Temperate Europe from Romania to France in the fourth and third centuries BC. All the early coins were based upon Greek types, starting with Philip I of Macedonia (359– 336 BC). In central Europe it was his silver tetradrachm which was chosen, in western Europe the gold stater with head of Apollo and two-horse chariot or biga (a).

The earliest imitations follow the originals closely, and are virtually indistinguishable, but gradually the coins were simplified, with only a single horse, and often other attributes added, in the case of the coin from Aulnat(b) a triskele on the reverse. The chariot is now only represented by a wheel. This dates early in the second century BC. In other cases the head and the biga became heavily stylized, as on the Gallo-Belgic E coin from Owslebury of the first century BC (c).

The Greek colonies in the west also provided prototypes. The coins of Rhode in northeast Spain have a rose on the back (d). The pattern between the petals became transfigured into a cross on the coins of southwestern France (monnaies à la croix), and symbols such as axes and crescent moons were placed in the angles (e). This coinage dating to the second and first centuries BC was the main type used by the tribe of Tectosages and their neighbours, and was imitated as far away as Austria and southern Germany.

Another popular prototype was the coinage of Marseilles, especially the type with a butting bull on the reverse (f). This was mainly used for cast bronze (g) and potin (high tin bronze) coinage which starts in the late second century BC, but mainly dates to the first century BC. In Britain the type is further simplified (h). The coins were cast in moulds by impressing papyrus into clay, and the designs were scratched in the clay using a stylus.

Economically and politically central Italy may have been dominant; culturally the Greek world still played the leading role. In the realms of literature, philosophy and science Rome still had little to compare, and many wealthy Romans completed their education if not in Athens or Alexandria, then in one of the western Greek colonies such as Marseilles. This influence seems to have extended north of the Alps. Caesar remarks that documents captured from the Helvetii were written in Greek characters, and until the conquest of Gaul all Celtic coins were inscribed in Greek, but changed to Latin script around 50 BC. All the prototypes for pre-conquest coins were likewise Greek; Roman coins are virtually unknown preconquest north of the Alps. The earliest copied were all eastern Greek, mainly Macedonian, but occasionally Greek colonies supplied the inspiration, such as Rhode whose rose was simplified into the ‘Tectosages cross’ found on coins in south-west France. But by the first century BC coins from Marseilles were circulating freely in Gaul, and provided the prototypes for many of the lower value issues.

With the exception of the influence of the Macedonian coin types, which belongs early in the period we shall be discussing, the Hellenistic world of the east Mediterranean had no visible influence on central and western Europe north of the Alps. Trade even with the Hungarian Plain was dominated by Italy, and the world of Alexander and his successors can be ignored for our purposes. With this brief and eclectic summary of a momentous period of Mediterranean history, we now turn to Temperate Europe.

La Tène C, second century BC

The picture previously drawn of La Tène B-C is largely true of the archaeological record. Trade had ceased with the Mediterranean, the settlement pattern was of small villages and farmsteads, and the burials indicate a simple, ranked, social organisation. But the changes which occurred at the end of La Tène C and especially in La Tène D, in the period 150–50 BC, imply that fundamental political, social and economic changes were taking place, for suddenly we are faced with tribal states who were capable of founding and maintaining large defended urban centres, the ‘oppida’. Hints of this change are found only in a small number of sites.

In Czechoslovakia industrial villages reemerge which are engaged in more than one or two ‘central place’ activities. The best known is Mšecké Zehrovice in Bohemia, find spot of the famous stone head of a Celt with curly moustache and wavy hair. It was found just outside a double Viereckschanze, the square enclosures which in Germany at least had a cult function. Surface finds from around the enclosures show that the settlement was engaged in metalworking, especially iron smelting, and also there is waste from producing bracelets of sapropelite, a type of schist. These bracelets were traded as far away as Switzerland.

Sapropelite bracelets were common in the earliest phase of the next site we must consider— Manching, on the south bank of the Danube in Bavaria. At the end of La Tène B the settlement seems to be merely a small farm or village, though only its ‘flat inhumation cemetery’ is known. However, the site had unique potential for trade passing east-west along the Danube. Not only could it control river traffic, and the crossing of the Paar, one of the Danube’s tributaries, but the land route along the gravel terrace is restricted by marshy ground to the south to a narrow strip, 400 metres across, which the later town was to straddle. Distributions of datable objects, such as the sapropelite bracelets and brooch types, show that this open settlement gradually expanded during La Tène C, and by the end of the period it justifies the adjective ‘urban’. Unfortunately we know little about the early industrial activity, as it is at present impossible to separate it from the later period of La Tène D; but it is likely to have covered a wide range. Manching however is a unique case, and it may be that it started life as a ‘port-of-trade’ between two tribal areas. The only site which might be comparable with Manching at this stage is Levroux on the western side of the central Massif in France. In area it is about 12ha, but the piecemeal rescue excavations have shown it had an industrial character, which included the manufacture of gold and silver coins; but its exact status requires further research.

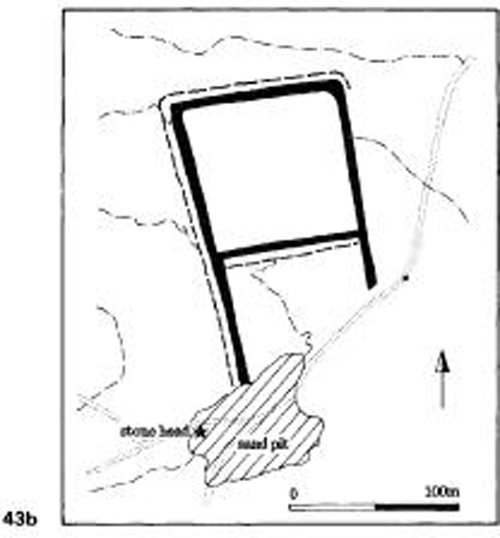

43 Mšecké Zehrovice

The majority of sites of the early second century in central and western Europe were small farming villages or hamlets. A few sites such as Aulnat in France and Mšecké Zehrovice in Bohemia seem to be somewhat more important, but even these can only be described as ‘industrial villages’. Mšecké Zehrovice has not been extensively excavated, but surface finds show that iron was being worked on a considerable scale, and also this was one of the sites producing bracelets of ‘sapropelite’, a kind of shale. The bracelets were made by hand from flat slabs of sapropelite, and the waste discs from the centre and unfinished bracelets are found in some quantities on the site (a). Bracelets of Bohemian sapropelite reached as far as Switzerland, and are not uncommon in the early phases of Manching (fig 44), but manufacture had ended by the time the Czech oppida were founded at the end of the second century BC.

The only visible features on the site (b) are two joined Viereckschanzen (square enclosures). Such enclosures have a wide distribution in late La Tène Europe, from Czechoslovakia to Britain. Two in southern Germany have been extensively excavated, Holzhausen and Tomerdingen. They were both cult sites, enclosing deep shafts which sometimes contained standing posts. Holzhausen had a wooden temple in one corner and a large number of hearths. Their function varies from one area to another. In Bavaria they are common, almost like parish churches, except they are found in areas of woodland away from areas of settlement. That at Gosbecks Farm, Colchester is more of a ‘cathedral’, the main cult site of the tribe of Trinovantes. The Czech sites fall somewhere in between—not all areas had them, and they are found inside settlements.

The famous stone head from Mšecké Zehrovice (‘Sir Mortimer Wheeler’) (c) is also often assumed to be from a cult figure, though outside Provence, stone figures are rare before the Roman conquest, and the funeral stele from Hirschlanden shows that not all figures are from religious sites. The head was discovered broken into fragments and thrown into a pit which contained no other finds. It comes from a sand pit just outside one of the Viereckschanzen.

Scale: a—1:2 Actual size: b—height 25cm

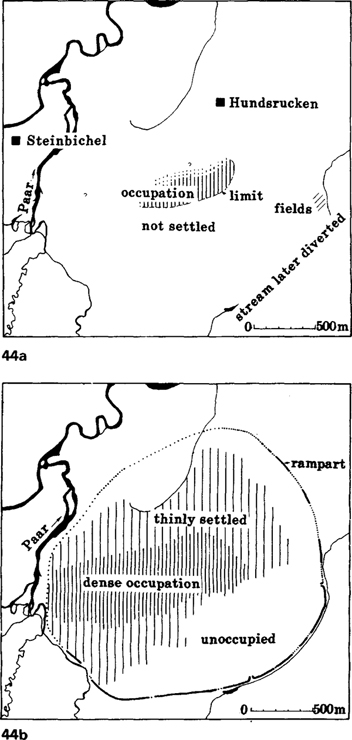

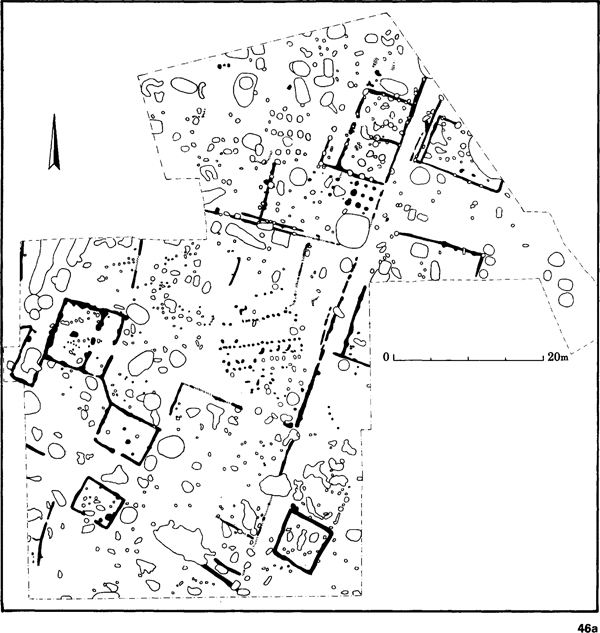

44 Manching, Bavaria

The earliest La Tène phase at Manching is represented by two typical flat inhumation cemeteries, Steinbichel and Hundsrucken, which start in La Tène B, and continue into La Tène C. The earliest settlement areas of La Tène B have not yet been located, but the La Tène CI occupation has been found in the northern part of the occupied area (defined by the distribution of La Tène CI brooches and sapropelite bracelets). By C2 it was expanding (a) to include most of the excavated area. The occupied zone shows a marked east-west orientation following the route along the Danube towards the ford/bridge over the river Paar.

By La Tène D occupation extended up to the limits of the ramparts. These were themselves only constructed in La Tène D, and up to this time the site had either been open, or at most defended by a palisade. The earliest defences were of murus gallicus construction, and huge quantities of timber and iron spikes were used. The rampart was twice repaired before the site was destroyed, apparently violently, around the middle of the first century BC. Both repairs were of Kelheim construction (see fig 45a). To build the defences a stream had to be diverted and an area of boggy ground enclosed (b).

Within the excavated area a pattern of mainly eastwest streets is clearly visible (c). Along the main road is a mass of small rectangular houses, perhaps workshops, and elsewhere there are long buildings (warehouses?), and palisade enclosures around large buildings, which may be the residences of the elite. These are especially found in the peripheral areas just inside the ramparts. The roads do not seem to have been surfaced, and a general lack of amenities (water supply, drainage, rubbish disposal) is a feature of the oppida.

The fourth site is Aulnat in central France, in the territory of the Arverni, the most powerful tribe in Gaul in the second century BC. This is another ‘industrial village’, only 300m in diameter, but it is one of a cluster of at least three villages about a kilometre apart, a situation reminiscent of the early phases of urban sites in the Mediterranean. It started in La Tène B when it already had a largely industrial character. During its occupation—it was abandoned in the midfirst century soon after the Roman conquest—it had been involved at one time or another in the working of gold, silver, bronze, coral, glass, bone, textiles and production of gold and silver coins, and perhaps pottery. Aulnat is also the only site in France to produce imported Mediterranean pottery dating to the end of La Tène C (a lone bronze jug from Slovakia is the only other object in Temperate Europe), though this is probably due to lack of adequate settlement excavation. The imports are ‘Campanian’ black-gloss wares, and white-ware sherds of unknown origin, but Dressel I amphorae had not yet appeared. In the same deposit was an early gold coin of local type, perhaps datable to the early second century, reminding us that gold coins had already been introduced, probably in the third century. A few original Macedonian gold coins are known in central Europe, but, like the earliest imitations, they are all stray finds without an archaeological context. All are high-value gold, though silver was quickly adopted as the standard in the east. They are widely scattered with no obvious concentrations, and such coins were rarely used for trade; so the mechanism for the adoption of coinage north of the Alps is still obscure. ‘Down the line’ trade is a possibility, or mercenaries returning from the Mediterranean have also been suggested. But the technology travelled too, as the earliest imitations are of high quality, scarcely distinguishable from the originals. This early coinage probably had little effect on the economy. Along with iron ‘currency bars’, it took its place as another form of standardised product, for use in only a limited sphere of prestige exchange.

The burial evidence is even less informative. In central Europe burials virtually disappear in the middle of La Tène C, and in the west by the end of La Tène C. At Münsingen the latest burials have few gravegoods, and little care is taken with the graves, and this seems to be the general pattern. Only in the Hünsruck-Eifel, where burials start to reappear after a 200–300 year gap can we see any differentiation appearing—one or two wagon graves with large numbers of local pots, but no trace of imported goods (though these are relatively common in the following century).

The documentary evidence, notably the Greek ethnographer Posidonius, also provides a few hints. He mentions Luernios, who became king of the Arverni around the middle of the second century BC, by scattering gold and silver to his followers from his chariot, and providing a great three-day feast. At this period the Arverni exerted some sort of influence over an area ‘from the Rhine to the Atlantic’. When the Romans invaded southern France they felt sufficiently threatened to send an expeditionary force under their king, Bituitos son of Luernios. All this evidence put together shows that trade contacts with the Mediterranean were being resumed, that in some areas social differentiation was becoming marked, and that locally early states were even being formed.

The oppida

At the end of La Tène C in Czechoslovakia and central Germany, the process of state formation in Temperate Europe achieved a tangible form, in the deliberate foundation of large urban centres, which seem to appear from almost nowhere. A generation or two later similar sites were established in southern Germany and France, where Caesar was to encounter them in his invasion of Gaul. Following his terminology, archaeologists call these sites oppida, the Latin word for towns. He spent the winter at one such site, Bibracte, capital of the Aedui, and he mentions meetings of the senate, and the election of the chief magistrate, the Vergobret. Bibracte has been identified with Mont Beuvray near Autun, a defended hill-top of 135ha. There can be little doubt that what Caesar is describing is an archaic state with a major urban centre.

Mont Beuvray was clearly chosen for its defensive qualities rather than any other reason such as relationship to trade routes, raw resources or agricultural land. This is true of many oppida—even those on trade routes tend to be on inaccessible hills. Only rarely is defensibility combined with accessibility, for instance islands in rivers (Paris, Breisach) or in river loops (Besançon), which tend to be the sites that still remain in use. The oppida are thus sites which have been deliberately implanted, established as an act of deliberate policy, and not as a process of natural accretion as in Greece and Tuscany.

In some cases we can identify undefended lowlying settlements which were abandoned in favour of the defended sites, and which were about the same size as their successors. Levroux we have already mentioned—the town was transferred to a hill-top only two kilometres away. The same happened at Basel and Breisach on the Rhine, but in both cases the earlier lowland sites had themselves only been in existence for a generation or two before their abandonment, and hardly started much before the beginning of La Tène D. These are relatively small sites, and the norm, especially for the larger oppida such as Mont Beuvray, was for a number of different settlements to combine in constructing the oppidum. So far, however, this has only been clearly identified in the Auvergne, where Aulnat was abandoned at the time of the foundation of the oppidum of Gergovie. Aulnat was a settlement of about 7ha, Gergovie 150ha.

Manching again provides the exception. The old settlement was not abandoned, either because it was now so large that the labour of reconstruction was too great, or more likely that there was no good defensible site near at hand. It thus represents the one defended oppidum in a not particularly defensive situation. The date of the defences (La Tène D) and their method of construction (murus gallicus) is however entirely in line with the western group of oppida such as Mont Beuvray.

At Manching all the buildings are of timber, and this is apparently true of pre-conquest sites in Gaul as well, though oppida that continued in occupation in the Roman period were given stone buildings within a generation or two. Unlike the earlier hillforts, which usually contained only a limited range of house types, the oppida show enormous variation in size and shape, suggesting economic and social complexity. Occasionally there is a rectilinear planned layout of streets, as at Villeneuve-St-Germain near Soissons in northern France. More usual is an irregular layout, with small houses constructed along terraces cut into the hillside. The overall pattern in principle resembles that of the classical cities, with small workshops densely packed along the major thoroughfares, and higher class residences in the more secluded fringes. One feature that is not obviously apparent is public buildings, though we know these must have existed as Caesar mentions ‘senates’ and ‘market-places’.

The ‘workshops’ are small rectangular buildings, usually no more than 4×6m in size, presumably used for both work and habitation. Large buildings also are found—some up to 30m long at Manching may be warehouses or barns—but it is difficult to work out functions of buildings as stratified deposits are usually absent, and several phases of activity may be jumbled together in the top soil. The upper-class dwellings are large wooden buildings, with a wooden palisade or fence forming a courtyard around them. Unlike their classical counterparts, these courtyard households engaged in industrial activities such as bronze and iron working, or coin manufacture, as though some industrial production was under direct upper-class control. Distributions of tools and industrial debris at Manching suggests specific industries may have had their own areas within the town. One street for instance has a high concentration of needles and other items associated with textiles, while the usually ubiquitous traces of metal working are absent. It is possible that some form of craftsmen’s guild system may have been operating.

With the foundation of the oppida most production became centralised, and there was a great upsurge quantitatively, though few technological innovations can be detected. Iron objects, especially mundane items such as nails and cleats, became common, whereas currency bars disappeared. Trade was now in finished objects rather than raw iron. A site like Manching may have been importing its raw materials from some distance: iron ore probably came from the oppidum of Kelheim 50km down river, and graphite clay for making cooking pots from Passau 200km down river. Over 75 per cent of the pottery wasnow made on the fast wheel, including 20 per cent fine red-and-white painted wares bearing elaborate geometric and curvilinear patterns. This pottery and some of the coins are the only objects which can claim any artistic quality; personal ornaments such as brooches and belt-hooks were now being mass-produced according to stereotyped patterns.

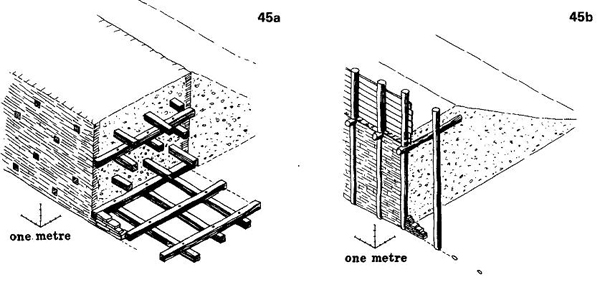

45 Rampart types of the late La Tène

The normal method of constructing defensive ramparts in Temperate Europe involved the use of both timber and an earth and rock infill, and occasionally drystone walling to revet the front and back. A vertical front wall was normal, while the ditch was little more than a quarry to provide material for the rampart. The main weapon for fighting was the spear, and for hand-to-hand fighting the sword, and for these defence relied on height.

From the late Bronze Age the front and back of the rampart was linked by cross-pieces in various ways. If enough timber was used, this could create an effect of a string of isolated chambers which could then be filled with earth and rock—the ‘box’ rampart found at the Heuneburg during Hallstatt D.More normally there were vertical posts back and front, and the ‘timber lacing’ just linked these posts, and the front was revetted by timbers (the Hollingbury type), or by vertical stone walling (the Preist-Altkönig type). This was especially typical of the fifth century, both on the Continent and also in Britain.

An alternative construction popular in the fifth century involved no vertical posts, only horizontal, both parallel to the line of the rampart and at right angles. The ends of the posts often protrude through the front and back of the drystone walling. It occurs on the continent but is especially common in Scotland. In Britain it dies out quickly, but it survived until the first century on the continent, when a more sophisticated form appeared in which the timber joints were nailed with large iron spikes up to 30–40cm long, and the rear wall revetted with an earthen bank (a). This is what Caesar termed the murus gallicus, and he remarks on its effectiveness against both fire and the battering ram. The Preist construction was also developed until it consisted of merely a front wall revetting an earthen bank (b the Kelheim construction). This is the standard construction on oppida in central Europe, while the murus gallicus has a more westerly distribution.

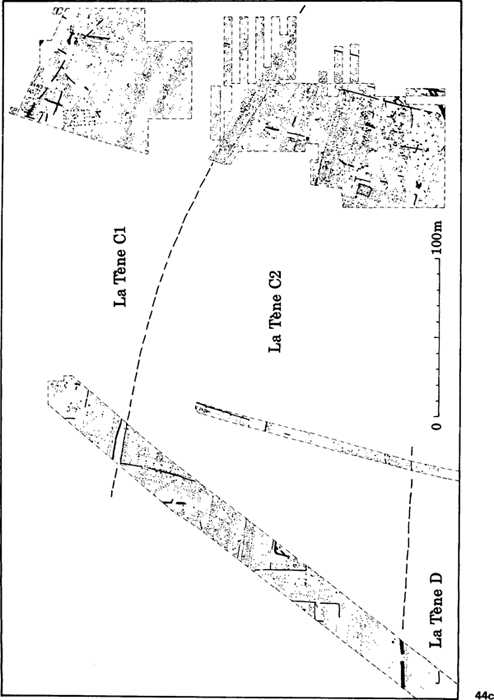

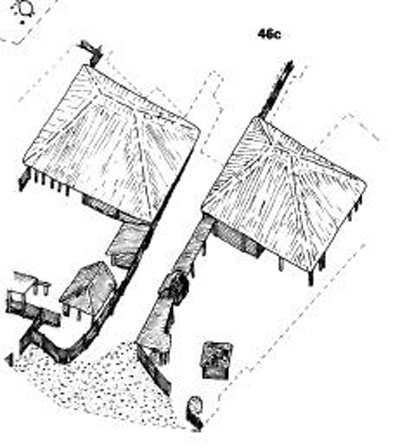

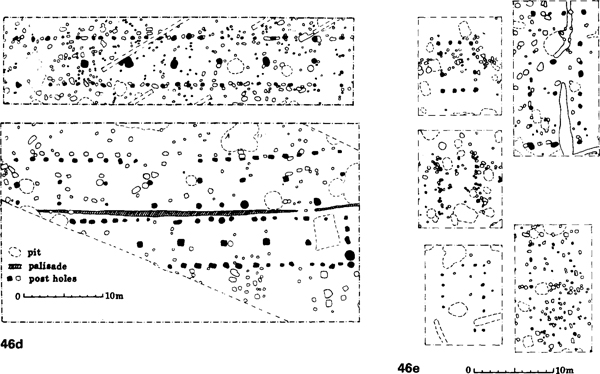

46 Buildings inside oppida

All the buildings in pre-Roman contexts in Temperate Europe are of timber. Those on the oppida are very varied in both size and shape, and indicate complex economic and social functions. Unfortunately it is often hard to reconstruct them as most are on hill-tops or ploughland where stratified deposits and floor levels have disappeared.

There was already a long tradition of settlement planning on hill-forts. Villeneuve-St Germain near Soissons in northern France (a) had a rectilinear system of streets bordered by large houses with fences around them. These palisade enclosures can be interpreted as high status dwellings, the equivalent of the courtyard house in Greek and Roman contexts.

Those at Hrazany in Czechoslovakia (b, c) lay at the centre of the oppidum in the most sheltered area. Unlike their Roman successors, industrial activities such as metalworking were carried out in the courtyard. Such enclosures are visible on the Manching plan (fig 44c).

Manching has also produced long buildings which may be warehouses (d), and small rectangular buildings (e) wich, from their siting along the main arterial highways, are likely to be craftsmen’s homes and workshops. The excavated area at Manching with small houses had a concentration of finds connected with weaving, hinting at the existence of specialist industrial quarters such as are found in medieval and other ‘pre-industrial’ towns. Public buildings are mentioned by Caesar, but have not been identified archaeologically.

To what extent the whole population was nucleated within the oppida is still unclear. Some courtyard buildings at Manching look like farms. The relative lack of diagnostic coins and painted pottery in the surrounding areas could either mean that there was no surrounding population, or that the finer objects were not reaching them— or, certainly in some areas, that the basic fieldwork has not yet been done. Small silver coins probably minted at Stradonice in Czechoslovakia generally are not found more than 30km from the site, whereas its painted wares seem to have reached virtually the whole of Bohemia. Though there were several major oppida in Bohemia all densely occupied, Stradonice seems to have held a special position in terms of the range of its industries and its external contacts. It is the only site to have produced coins in quantity, and it is clear that a fully monetised economy was certainly not operating at this period.

Inter-regional trade is as hard to detect as local trade. Individual objects such as coins could travel considerable distances—there are several western Gaulish coins from Czechoslovakia, and the Stradonice silver coins are based on those used by the Aedui at Mont Beuvray—but coinage was not used for inter-regional trade. Individual pots too were widely traded: there are graphite ware cooking pots at Aquileia on the Adriatic Coast, and at Aulnat several hundred kilometres from Manching, the nearest centre of manufacture. There are three main sources of graphite clays: at Passau on the German-Austrian border; in southern Bohemia near the oppidum of Trísov; and more scattered sources in Moravia. The clay was exported to several production sites—Hallstatt, Budapest, Trísov, Manching, and probably others—and the finished products not uncommonly reached Romania, southern Poland, central Germany and Switzerland. The fine red and white painted wares were probably also widely transported, but no detailed fabric studies are yet available. In the west, graphite slipped pottery from southern Normandy was reaching Hengistbury Head in southern England, in some quantities.

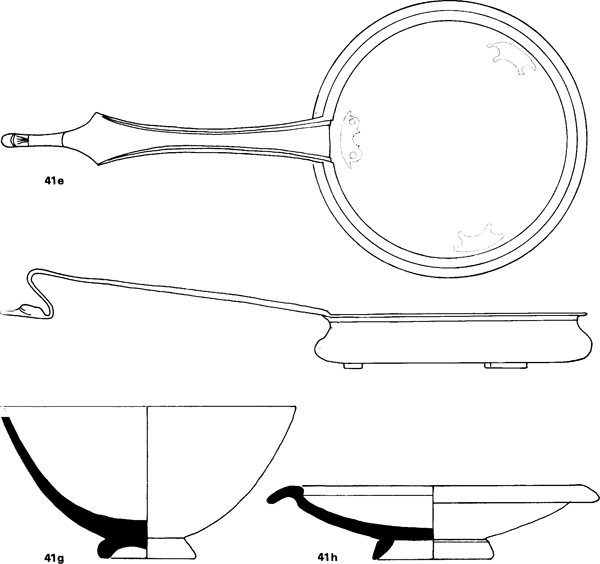

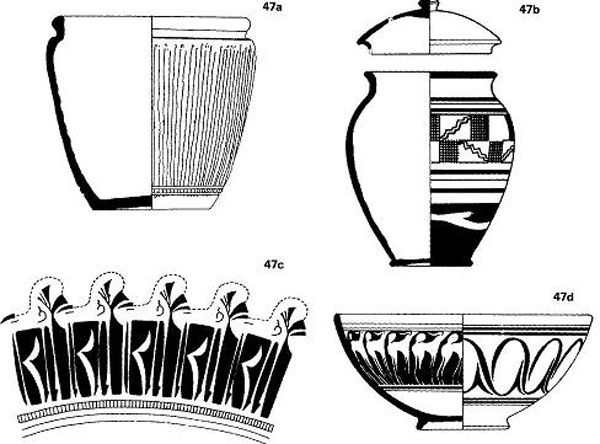

47 Late La Tène pottery

During La Tène C, the second century BC, pottery in Temperate Europe started to be mass produced. To a certain extent each urbanised oppidum such as Manching produced its own pottery, even importing the clay if necessary. But some more specialised centres appeared, such as Sissach in Switzerland, which were the antecedents of the mass production centres of the early Roman period like Lezoux.

About 25 per cent of the pottery was still produced by hand, but the everyday cooking and eating vessels tended to be wheel made. The Graphittonkeramik cooking pot (a), made of a clay containing graphite, was manufactured at a number of oppida such as Manching and TrČísov, and was widely traded, reaching Poland, Romania, Italy and France.

The finest products were the painted wares made in fine off-white fabrics. The production centres are widely distributed, from southern France to southern Poland, and certain centres specialised in its production, such as Zemplín in Slovakia, Budapest, Stradonice in Bohemia, Manching and Sissach. The normal product had painted red and white bands, like the example from Manching (b), sometimes painted over with simple geometric patterns in mauve paint. More rarely curvilinear patterns from La Tène Art appear. Roanne in central France produced especially elaborate designs, which might include stylised animals such as horses (c) or deer (d). The samian production centres of La Graufesenque and Lezoux started by producing these painted wares in the late first century BC.

Scale: 1:4

How this trade system functioned is far from clear, but certain individuals seem to have travelled considerable distances. It is easier to identify women in foreign contexts as their brooches and other trinkets can be distinctive. From Manching come two groups of three foreign objects found in close proximity to each other: three brooches of a central Alpine/north Italian type (possibly the Ticino valley), and brooches and a belt fitting of north-west German type. In a cremation cemetery at Vilanów near Warsaw were found two Nauheim brooches, typical female ornaments for Czechoslovakia/southern Germany, but rare in Poland. We have documentary evidence for longdistance marriage alliances, for instance between Arminius the German leader, and a daughter of the king of Noricum.

With the Roman capture of southern France in 125–121 BC, the floodgates were opened for Mediterranean trade through France, and the Alpine routes too flourished. Once again the graves of the Ticino Valley were rich in bronze vessels imported from Campania, but more important now were the more easterly passes in Austria. The kingdom of Noricum is mentioned on a number of occasions in Latin sources for the quality of its iron, Pliny stating that it was only rivalled by that of the Parthians and the Chinese. High-quality iron swords made of iron strips welded together were being produced in the Alps, especially Switzerland, from the second if not the third century BC, but the Noricum exports to Italy included tools such as anvils, rings, hooks, and iron vessels. This information comes from trading accounts scratched on the walls of cellars at the Magdalensberg, probably the ancient Noreia, capital of Noricum. Here there was an enclave of Italian traders, who mention their trading partners in various towns in Italy, and, in one case, Mauretania in north Africa.

Italian traders seem to have controlled the French river routes as well. Both Posidonius and Caesar mention their activities, but nowhere do they mention Gallic traders. Posidonius writes that in central France it was possible to acquire a slave for an amphora of wine—‘a servant for a drink’—though other goods and raw materials were coming back, like the hunting dogs from Britain that Strabo mentions. Three sites seem to have played a key role in this trade. Vienne on the Rhône was a border town on the edge of the Roman Provincia, controlling the river routes up the Saône and Rhône, and also the land route on to the upper Loire. Here, controlling the headwaters of the Loire was the small oppidum of the Palais d’Essalois, a site which is still littered with hundreds of fragments of Dressel I amphorae. Toulouse performed a similar function to Vienne on the upper Garonne, on the route to the Atlantic at Bordeaux. Through these sites goods reached the north in ever increasing quantities. The Campanian fine wares are not uncommon in central France, and reached the central Rhine. The wine amphorae are found on the Mosel, in northern France and southern England, the bronze vessels reached central England, Denmark, northern Germany and Poland. More rarely silver vessels and glass from Italy travelled similar distances. The amphorae are much more common in the west as it was easier to transport them up the rivers than over the Alps. The bronze and silver vessels, and occasionally the amphorae, are mainly found in burials, but they also occur in hoards, and in fragments on settlements. They were clearly reaching the north in considerable quantities.

The mechanisms for trade seem to have varied from region to region. At the Magdalensberg the Italian traders operated a monopoly, doubtless under royal control. The Aedui in central France were content to extract tolls from the passing trade, and the right to collect them was auctioned each year, the proceeds going to the state. Monopoly control of the trade was less feasible here, as all areas, excepting Vienne and Toulouse which were under Roman control, could be by-passed. None the less the Aeduan Dumnorix attempted to obtain a monopoly by packing the auction with his armed followers. In southern England, Hengistbury Head near Christchurch may have acted as a ‘port of trade’, controlling the tin trade, and acquiring wine via the Loire or Garonne. The impact of this trade even on minor farming sites can be gauged from the increasing size of grain storage pits at Owslebury, which was acquiring wine, silver coins and bronze belt fittings through Hengistbury Head.

This trade may have been the direct cause of the state formation, and the move to defended oppida in western Europe. Caesar says that hardly a year passed without one Gallic state making war on another. Victory in war could extend territorial limits, but it also provided tribute, booty and slaves. It could both extend control over trade routes and provide the goods with which to trade. In the west it is clearly the trade which comes first, and the oppida second. The Arverni, perhaps because of their military power, were one of the last tribes to construct an oppidum—Gergovie was not founded until the Roman conquest or even later. Urbanism was not necessarily a sign of civilisation and power, it was more a sign of weakness. It does not however explain the early move to defended sites in central Europe. Filip has suggested Germanic pressure from the north, which was certainly a reality by the end of the first century BC. There was also the expanding power of Burebista, king of the Dacians in Romania.

However, if we are to trust our historical sources, the formation of the state had already happened before the upsurge of trade in the first century, with the hegemony of the Arverni. They are mentioned in even earlier contexts at the time of Hannibal’s invasion of Italy. The initial phase of the formation of the tribal states may rather have been connected with renewed problems of over-population, coming after the period of migration, and the renewal of Mediterranean trade may be a secondary, almost irrelevant factor. The tribal states of the Celts were certainly very different in size and demography from the city states of the Mediterranean, but at present neither literary nor archaeological sources can tell us much of their development.