CHAPTER SEVEN

The Roman Empire and Beyond

Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, effectively completed by 51 BC, saw the establishment of the Roman frontier along the Rhine. In the succeeding decades the western Alps were gradually assimilated, and in central Europe the first moves were made into the Hungarian Plain. In 15 BC the king of Noricum died, bequeathing his kingdom to the Roman people, and opening up the rest of Pannonia and southern Germany for conquest. By 14 BC the Rhine-Danube frontier had been established, and, despite subsequent attempts by Drusus and then Germanicus to extend to the Elbe, this was to remain the boundary, excepting the addition of Britain under Claudius in the west, and of Dacia under Trajan in the east. Before we evaluate the immediate effect that incorporation into the Roman Empire had on the areas we have been considering, we must first discuss those areas which were not, or only later, conquered—Britain and Germany.

Britain

The southern parts of Britain had lain on the fringe of trade systems of the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods. At least some of the fashions in weaponry had reached the Thames area in both periods, and in personal ornaments especially brooches during La Tène A, which were disseminated throughout virtually all the British Isles. At the same time the more geometric version of the Early Style of La Tène Art was also adopted, and, more rarely, some of the orientalising motifs such as the palmettes on the hanging vessel from Cerrig-y-Drudion in North Wales. Had we located burials of this period in southern England, Greek and Etruscan vessels might well have been found also, as the skeomorphic Greek handle attachments incised on the pottery from Chinnor suggest such items were reaching the south-east.

Britain was one of the first areas to demonstrate the increasing regionalisation of the middle phases of the La Tène period. The Münsingen and Dux brooch styles, ubiquitous on the continent, are virtually unknown in Britain, though the British styles of brooches do show some cognisance of continental trends. Some influence of Waldalgesheim style is also found in the Insular styles, but our chronologies of British La Tène Art are so vague, that it is impossible to say how and when this influence was introduced. Pottery styles too no longer follow the continental, indeed in some areas such as Wessex and Yorkshire the tradition for producing fine pottery disappeared. This could relate to changes in the social structure, to the organisation of production and trade, and ultimately be due to the collapse of the La Tène A trade system centred on the Hunsrück-Eifel.

The fourth and third centuries were thus periods of relative isolation for Britain, though some general trends are visible which continued into the late Iron Age. One of these was the gradual abandonment of the hillfort. Hillforts were rare in eastern England at all periods, on the chalk wolds of Yorkshire all had been abandoned by the end of the Bronze Age. South-east England, like other areas of the continent, saw a spate of hillfort construction in Hallstatt D/La Tène A, but with certain exceptions most had been finally abandoned by the fourth century. During the second century Sussex and eastern Hampshire gave up the hillfort way of life. Precisely what this signifies is still unclear, but it could be a change to a more centralised political system which could effectively limit localised warfare—a change perhaps from a simple to a complex chiefdom if not state system of social organisation.

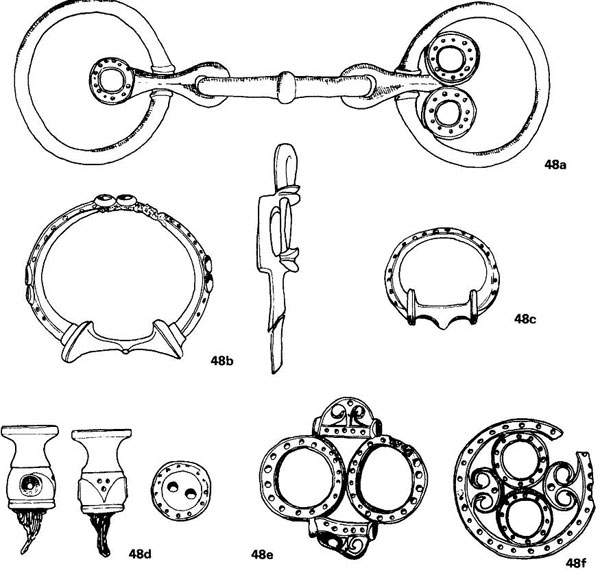

48 British La Tène Art

Though luxury items of classical origin were reaching Britain in the first centuries BC-AD, and industry was becoming centralised, local production of prestige goods by no means faltered, as it did over the rest of central and western Europe. In fact it was the period when it reached its zenith, and even the Roman conquest did not immediately destroy it. Partly this was due to the need for items unavailable from the classical world, such as chariot fittings, torcs, shields and mirrors, whereas bronze and silver vessels were available and show less artistic development.

The bronze industry was highly specialised—the smith at Gussage All Saints was only producing fittings for vehicles and harness, not personal ornaments such as brooches and bracelets, nor weapons, nor bronze vessels. None the less he had to produce a range of fittings, as the hoard found just outside the Yorkshire oppidum of Stanwick demonstrates. Each set of harness fittings required two bits (a), a large terret (b) and two small terrets (c) which were fitted to the yoke and through which the reins passed, and two linch pins to hold the wheel on to the axle (d is only the upper part of the pin). In addition a number of loops (e, f) and strap ends (g, h) were needed for the harness, and an optional range of further embellishments both for the harness and the chariot itself (i).

Each set was made with matching decoration, and the Gussage smith certainly had a range of different styles to offer. The Stanwick finds belong to four sets, and two harness mounts are illustrated to show other styles, one with moulded ‘trumpet shapes’ (j), and the other with decorated ‘lips’ protruding (k). The Stanwick sets need not be from one workshop as they were deposited as scrap.

Each class of object had its own style and tradition of decoration, though cross influences can be seen, for instance between torcs, mirrors, and helmets. Decoration on the mirrors demanded an engraved technique on the back of the mirror (they were apparently hung upsidedown on the wall with the polished bronze surface concealed until needed). The earliest mirrors had a restrained geometric ornament, but by the first century AD the finest, such as that from Holcombe in Devon (1), had a highly developed and florid abstract form, with reserved areas infilled with basket cross-hatching.

Basket cross-hatching also appears on the gold torc from Snettisham (m) filling in the curvilinear shapes on the terminals. The rest of the pattern was carried out in strong relief, a characteristic also found on the gold torcs from Ipswich (n). The Snettisham finds are from a hoard dated by coins to about the middle of the first century BC, and the finds consist mainly of scrap, whereas the Ipswich torcs include examples which were unfinished.

Scales: a—l—1:2

Not until the second century, or even as late as the early first century BC, was sustained contact with the continent renewed. In the south-east this was first detectable in the introduction of gold coins of types also found in northern France, and this contact was maintained for at least two or three generations, until the Roman conquest of Gaul. Secondly there was the adoption of the potter’s wheel, though, like the coinage, the social and economic context in which this was done is obscure. The cremation burial rite prevalent in northern France and western Germany also appears in Kent and Essex, though with regional idiosyncracies—for instance, swords and spears virtually never appear in these burials in Britain. In part we know there was immigration into Britain, but the continental names that are found—the Atrebates and Belgae—are on the fringe of the areas most influenced from the Belgic areas on the continent. Ideas also flowed the other way, as British styles of hillfort construction—complex entrances, ramparts of dumped soil with sloping ‘glacis’ front—were adopted on the Atlantic coast of France.

The second point of continental influence can be more sharply defined: the port of Hengistbury Head, which has already been mentioned as a direct recipient of Mediterranean goods—wine amphorae, and even Campanian black-gloss ware. This was also probably a second entry point for the potter’s wheel, as some of the earliest wheelturned pottery in Wessex imitates the Normandy-Breton fine wares. The wheel-turned styles of Cornwall, Dorset and Hampshire are very different from those of eastern England, and certainly have a separate origin. The Breton links are confirmed by the silver coinage assigned to the north Breton tribe of Coriosolites which are also found at Hengistbury, probably passing through the port site of Alet at St Malo, the sister port of Hengistbury. The hinterland of Hengistbury can be fairly well defined. The graphite slipped wares hardly passed beyond the port, but the amphorae reached central Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, southern Dorset, and western Cornwall; the imported coins penetrated even further inland to the Thames and Severn. These contacts are confirmed by the imported pottery from Hengistbury which includes decorated Glastonbury style pottery from Cornwall and Somerset.

According to Caesar the cross-channel trade was controlled by the Veneti of southern Britanny, but virtually no coins or other imports are known from that area. Caesar’s activities in the Atlantic, culminating in the destruction of the Venetic fleet, may have adversely affected the cross-channel trade. The later Dressel Ib amphorae, which appear about the middle of the first century BC, are virtually unknown at Hengistbury—but the trade did not completely collapse. Early Augustan amphorae from southern France (Pascual I) are known from Hengistbury, Poole Harbour and Owslebury, and central Gaulish fine wares are also known at Cleavel Point near Poole, which may have replaced Hengistbury as the major port. By the first century AD the trade had ended, and eastern England was the main recipient of imported goods.

The shift in emphasis to the east reflected the changes induced by the Roman conquest of Gaul. The major market, especially for food stuffs, was now the army of occupation in Gaul, though we are unsure where its bases were. The earlier phase of contact between about 50 and 15 BC is difficult to define, as there is no major centre through which goods passed, but there is evidence for increasing social differentiation from Kent to East Anglia. Firstly there is a number of rich burials which, in addition to large numbers of local pots, contain imported Mediterranean goods—bronze Campanian vessels, Italian silver cups, Dressel Ib wine amphorae, north Italian silver brooches. Of more local origin are large iron fire-dogs, wooden buckets with decorative bronze fittings, Kimmeridge shale vessels, and occasionally defensive weapons (shields, mail corselet) but never offensive weapons. These rich burials continue on until after the Roman conquest.

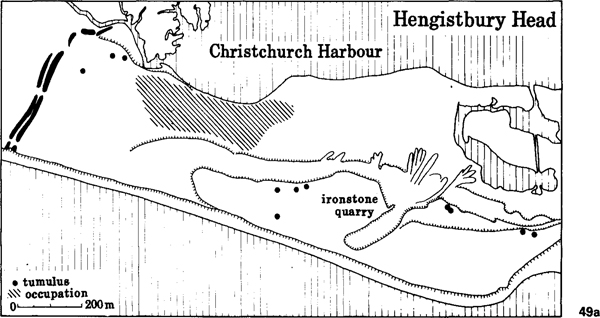

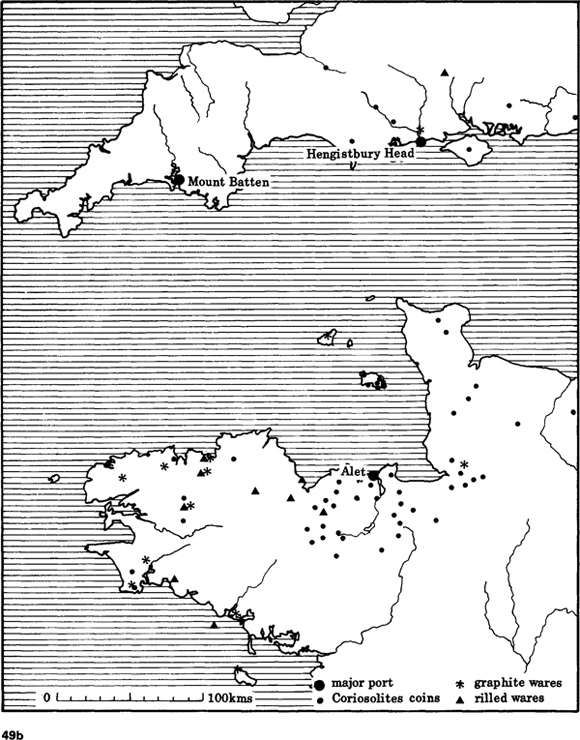

49 Hengistbury Head

Hengistbury Head is a peninsula which cuts off Christchurch Harbour from the open sea (a). It controls the river routes of the Avon and Stour into the chalk heartlands of Dorset and Wiltshire. It had been occupied in the late Hallstatt period and at various times during the La Tène period, and at some time the headland had been cut off by a massive defensive earthwork. It was at the end of the second century BC and during the first half of the first century that it rose to importance, possibly virtually controlling all the trade from the continent to the southern part of England.

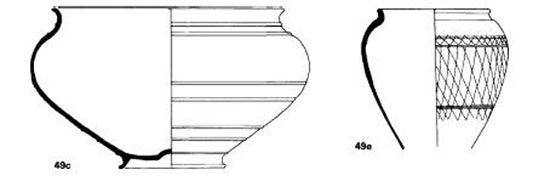

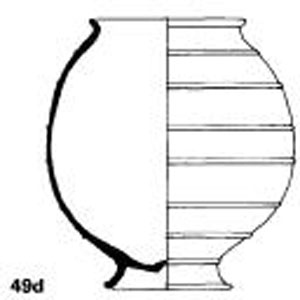

It is the most prolific site for Dressel Ia amphorae in. Britain, which perhaps reached here via the Carcassonne Gap route in southern France. It is the coarse pottery which shows its hinterland most clearly (b). From the nearest part of France (Brittany and Normandy) there is fine wheel-turned pottery with cordons (c, d) which may have come via the port of Alet at St Malo, and the pottery with graphite slip (e) comes from a similar area. Coins of the Breton tribe of Coriosolites also occur at Hengistbury, but none is known of the Veneti of southern Brittany, whom Caesar claimed had a monopoly of the cross-channel trade. Pottery is also known of clays found only on the Lizard in Cornwall, and sherds occur of Somerset and Dorset types as well. Wine amphorae, which presumably came through Hengistbury, occur in Cornwall, Dorset, the Isle of Wight and Hampshire.

Scales: c, d, e—1:4

In East Anglia where such burials are not known, the concentration of wealth is indicated by gold torcs, especially those from Snettisham and Ipswich. In both cases the context of the finds is unknown, though Snettisham consisted of two or three separate hoards, and included other items such as coins. The Ipswich torcs were unfinished, and the Snettisham finds may also have included scrap waiting to be melted down. How much earlier this social differentiation started is not clear— Snettisham should date to about the middle of the first century BC, and Caesar implies the existence of an elite chieftain class in the south-east. In about 20–15 BC this process reached its climax, with the establishment of a number of tribal kingdoms under individuals such as Tasciovanus and his son Cunobelin, who not only produced coins inscribed with their own names, but referred to themselves as ‘kings’. Independent historical sources confirm Cunobelin’s claim calling him ‘king of the Britons’. By the time of the Roman conquest kingship had been established over most of the east of England, among the Atrebates, Catuvellauni, Iceni, Brigantes and Dobunni.

The second phase of contact starting around 15–10 BC was brought about by both internal and external changes. The Roman army, now more obviously the main source of influence, was concentrated on the Rhine frontier. Much river trade doubtless passed through the Rhine mouth across the North Sea, but the newly established road network through Bavai in northern France to the middle Rhine provided an alternative connection. Imported goods from the Mediterranean now came up the Rhône-Rhine routes. The second change was the development of major centres of population in eastern England, some open settlements like Braughing, others, like Colchester, the British version of oppida.

50 The changing relationship between Britain and the Roman empire

The conquest of southern France in 125 BC gave Rome control of the two major trade routes through France. The eastern runs up the Rhône valley to Switzerland, southern Germany, the Paris Basin, and the Loire, and near the frontier, the town of Vienne developed rapidly, specifically controlling the route to the upper Loire. The western route is over the Carcassonne Gap to the upper Garonne at Toulouse. This latter was the easier route to Britain, and it was probably via here that wine travelled to St Malo and Hengistbury Head, though the Loire route may also have functioned.

After Caesar’s conquest of Gaul in 58–51 BC, trade contacts across the Channel were more diffuse, and a number of short crossings may have been functioning. We do not know the disposition of the legions in the generation after Caesar, but they seem to have been widely scattered. Caesar’s treaties after his invasion of Britain may have favoured links in eastern Britain as the distribution of Dressel Ib amphorae suggests, but the Atlantic route was still functioning, as Spanish Pascual I amphorae turn up in Hampshire and Dorset. Poole Harbour may have replaced Hengistbury Head as the major entrepôt. In eastern England there was no obvious port site operating, and goods reached a wide area around the Thames estuary, though Braughing in Hertfordshire, perhaps the capital of the developing Catuvellaunian state has an unusual concentration of imports.

Augustus’ decision to conquer Germany radically altered the situation in Gaul, with a concentration of troops on the Rhine frontier. The need to supply this new market caused the emphasis in trade to fall on the eastern Rhône-Saône-Mosel route, and all early imports from the Mediterranean may have reached Britain via this route. Within a decade or two, power had shifted from Braughing to Colchester, one of the closest British ports to the Rhine market, and Rhenish pottery (Gallo-Belgic wares) appears there in quantity. Eventually Colchester may have exercised a monopoly in the lucrative cross-Channel trade.

With the conquest of Britain the situation changes again, though it took a decade or two for Colchester to lose its supremacy. Partly the market had shifted— Britain had its own four legions to supply and three of these had come from the Rhine. But the new need was for an administrative centre as close as possible to the shortest Channel crossing, and so to the overland route to Rome, but sufficiently inland to maintain contact with the forward legions. Colchester was too far to the east, but London was ideally situated for both purposes, as well as providing a port with major river access to the centre of the new province.

Thus, if we accept there was likely to be a time-lag to adjust to changed circumstances, the relative importance of Hengistbury Head, Colchester and London in their relationship with Rome can be explained in simple geographical terms.

Colchester (Camulodunum) has many of the characteristics of a town. It was one of the residences of the royal dynasty of Cunobelin, and the royal graves are probably those in the large tumulus at Lexden which have produced amphorae, Italian bronzes, remains of a mail corselet and a silver coin of Augustus in a setting. The royal palace may have been at Gosbecks where there was also a shrine (a Viereckschanze) which after the Roman conquest acquired an amphitheatre as well. The industrial and trading area lay at Lexden commanding the highest tidal part of the river Colne. Unlike a Roman town the population was not nucleated, and the whole was enclosed by massive linear earthworks enclosing at least 20 square kilometres. The two major Catuvellaunian centres inland may have started a bit earlier. Coins of Cunobelin’s father Tasciovanus are much commoner at Braughing, and at St Albans (Verulamium), and, though he struck coins at Colchester (inscribed CAM), those inscribed VER (for Verulamium) are much more common. Braughing consists of a small defended enclosure surrounded by a large scattered open settlement, and may well have been the earlier royal residence. St Albans is again a scattered settlement, like Colchester, with linear dykes enclosing the whole complex which includes several cemeteries.

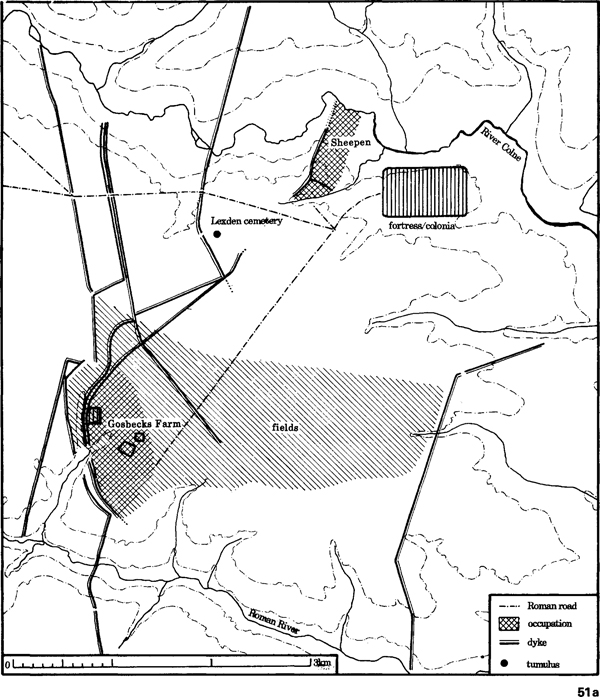

51 Colchester, Essex

The earliest evidence we have for the existence of Camulodunum (the fort of Camulos, god of war) is on inscribed coins of chieftains such as Tasciovanus, which should date to about 15 BC. The earliest occupation from the settlement dates to about AD 10, by which time it was the capital of Tasciovanus’ son Cunobelin. By the time of the Roman conquest in AD 42, massive linear earthworks had been built around the site, enclosing some 2000ha (a). Much of the area enclosed included farmland and also the cemeteries, such as the massive tumuli at Lexden perhaps the burial place of the royal family itself.

There were two centres of occupation. One lay around the religious sanctuary at Gosbecks Farm where a square enclosure has been found underlying the Roman temple. Adjacent is a sub-rectangular enclosure which looks like a native farming estate, and could be the royal residence, and around it the aerial photographs show an extensive system of fields. The second centre of activity is the Sheepen site where excavations have revealed evidence for trading and industrial activity, including the minting of coins.

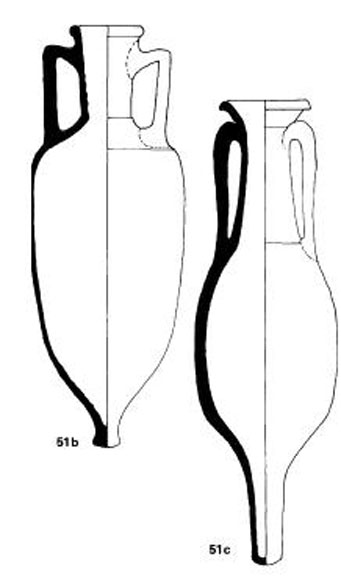

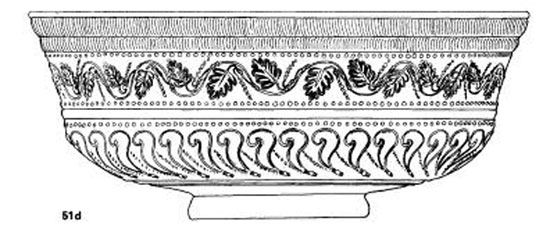

Colchester was in close contact with the Rhineland (see fig 50), and Gallo-Belgic pottery from that area is common. There are also numerous fragments of amphorae which were used to import wine, olive oil and fish paste. The Dressel 2–4 amphora (b) comes from Italy or southern France, and was probably for wine, the Dressel 7–11 (c) are Spanish and were for fish products. It is interesting to note that from a pit at Skeleton Green, Braughing, which contained fragments of Spanish amphora, there were also bones of the Spanish mackerel Scomber colias. Samian pottery was also imported both from Italy (Arrezzo) and southern France (d).

Such was the importance of this site that Claudius himself travelled to Britain to take part in its capture. A fortress and possibly a second small fort were established, and initially the road system for the new province was centred on Colchester, where a Roman colony and Imperial cult centre were also founded. Within a couple of decades it was superseded by London as the major city of the province.

Scales: b, c—1:8; d—1:2

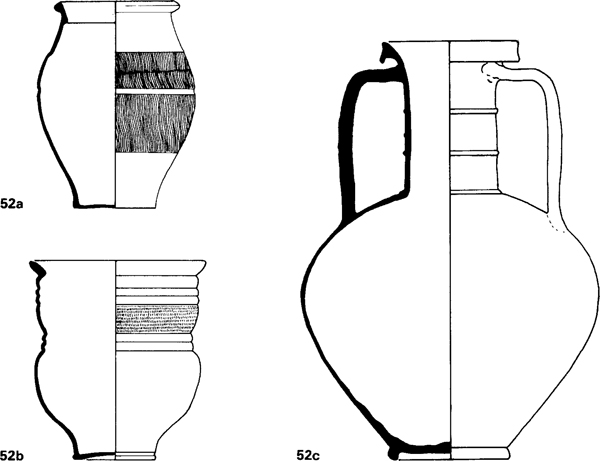

52 The Gallo-Belgic pottery industry

The Gallo-Belgic pottery industry appears around 15 BC, with centres of production on the lower and middle Rhine, the Mosel and northern France. The arrival of the Roman army on the Rhine frontier at this time is certainly closely connected. The precise origins of the industry are still unknown, but it arrived fully developed. It certainly did not originate from the local late La Tène pottery industry, and an origin somewhere in central France is most likely.

The potters produced a range of beakers and jars in fine slipped or plain wares, often decorated with fine rouletting, like the butt-beaker (a) and the girth-beaker (b). The latter certainly finds its origin in middle-late La Tène ceramics in central France. Other innovations were flagons and double-handled flasks (c), the latter in a distinctive white fabric. The most common products were plates and platters (d), either in a light grey ware with a black polished surface (terra nigra) or a fine red-slipped ware (terra rubra), often stamped with the maker’s name (e).

Platters were unknown in late La Tène contexts, except as imitations of Mediterranean types, and these Gallo-Belgic platters are mainly imitations of Campanian and Arretine samian forms.

The earliest occurrence of the Gallo-Belgic types is on the forts of the Rhineland such as Haltern or Oberaden, founded during the campaigns of Drusus and Tiberius, but they also occur in native contexts, such as the rich cremation burials from Goeblingen-Nospelt in Luxembourg. They were extensively traded along the Rhine, reaching Britain around the turn of the millennium. By about AD 10–20 workshops had been set up in England, mainly in the Colchester area, perhaps under royal patronage, though it is still difficult to distinguish imports from native production. Certainly of local production are the distinctive butt-beakers, Camulodunum 113 (a), which were extensively traded over southern and eastern England. The Gallo-Belgic industry continued until about AD 60–70.

Scales: a, b, c, d—1:4; e—1:1

The Rhineland influence is most clearly visible in the pottery, the unusual ‘Gallo-Belgic’ industry which produced plates imitating Campanian and Arretine wares (black slipped ‘terra nigra’ and red slipped ‘terra rubra’), fine rouletted beakers (butt beakers, girth beakers), and various flagons and flasks all in the Graeco-Roman tradition. The plates often bear the stamps of the potters, and show links with the Mosel, and especially Bavai, a major production centre. Colchester started producing its own versions made by potters doubtless brought in under royal patronage, and their wares reached as far as the Humber and central Hampshire. Amphorae too were imported in large quantities, containing not only wine, but olive oil, and fish paste from southern Spain. Arretine red-gloss wares, which had by now replaced the black Campanian vessels, are also not uncommon at Colchester, but, they were increasingly replaced by the developing samian industry of southern France. Colchester was the main, perhaps the only port for this trade in the later periods, and it may well have been ‘administered trade’ under direct royal control. Not surprisingly British exports on the Rhine are rare, but not unknown, and include enamelled harness equipment from Paillart (Oise), and a bronze mirror from a burial at Nijmegen.

The early rich burials are clustered around St Albans and Braughing, as might be expected from the ‘tribute’ distribution found in complex chiefdoms. The later ones are more widely scattered from Kent to Cambridgeshire, and are in fact almost on the periphery of the Catuvellaunian kingdom, a pattern which is also found in the early Danish state of the tenth century AD. Gold coins on the other hand show a fairly even distribution, though the bronze is more nucleated in the major centres. If market exchange utilising low value coinage was operating, it only involved the major centres, and had hardly penetrated the countryside. On the fringe of the coin distributions of Cunobelin a number of minor centres appeared— such as Dorchester-on-Thames and Great Chesterford, which could have operated as ‘gateway communities’ for trade beyond the Catuvellaunian state. Fine pottery certainly travelled beyond the coin distribution.

Around this central state there developed a number of secondary states under kings producing their own inscribed coinage. That of the Dobunni, based in Gloucestershire, was certainly in close contact with the Catuvellauni along the Thames valley, and its oppidum of Bagendon, north of Cirencester, was importing Gallo-Belgic pottery in quantity, and more rarely Arretine and south Gaulish samian. To the south the Atrebates, under their kings Commius, Tincommius and Verica, at times were able to rival the developing Catuvellaunian kingdom, though both the latter are mentioned in the historical sources as petitioning for help from the imperial court at Rome. At the time of the conquest, it was in their kingdom in west Sussex that the Romans found their staunchest allies. The Iceni to the north in East Anglia seem also to have been anti-Catuvellaunian, and later pro-Roman, and before the conquest were relatively isolated from the main trade system. The kingdom of the Brigantes may be a later development, when it formed a client kingdom on the northern fringe of the initial Roman province. Its main centre was at Stanwick, the finest surviving British oppidum enclosing about 330ha, which controlled the major land routes to the north and north-west, while maintaining sea links via the estuary of the Tees. Not only was it importing Gallo-Belgic wares and samian, but also Roman tiles to be used for buildings as yet undiscovered.

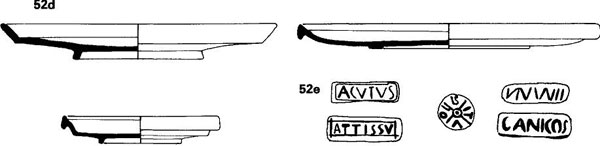

53 Welwyn Garden City

Burials are virtually unknown in the Iron Age in south-eastern England until the first century BC, when cremations similar to those in neighbouring areas of the continent appear. Normally there are between one and four pots in the grave, and the occasional brooch or other personal item. However, there is a group of richer burials which have many more pottery vessels, as well as local luxury items (shale vessels, mirrors, bronze bound buckets and firedogs), as well as imported luxuries (wine amphorae and bronze and silver vessels).

The burial at Welwyn Garden City is the most recently excavated of this rich class (a). It was part of a small cemetery of about a dozen burials, but none of the others had rich gravegoods, though not far away, at Welwyn, two rich graves were found last century. The Welwyn Garden City burial was in a rectangular pit with no trace of any surface mound. It was the cremation of a man of about 35 who had been wearing a bear skin—the bear’s burnt phalanges were found mixed with the human bones.

The imported items included five wine amphorae and a bronze Campanian pan (see fig 41 e), and a silver cup of Italian origin similar to one from Welwyn (b). A set of coloured glass gaming pieces may also be an Italian import. There was an iron object which may be the boss of a shield, and several of these rich burials have produced defensive weapons (shields and a corselet) but never offensive weapons.

The earliest of these burials are found in the area of Hertfordshire where the kingdom of the Catuvellauni was developing, but by the late first century BC and early first century AD they are found in a wide arc around the oppidum of Colchester, extending from north Kent to Northamptonshire and Cambridgeshire. They must represent the elite class of the kingdom of Cunobelin.

Scale: b—1:2

Unlike the continental wares in the late La Tène, the importation of foreign luxury goods did not cause the home industry in luxury items to collapse, rather the first century BC and first century AD see the culmination of Insular La Tène Art. Production of fine metalwork, though centred in the eastern kingdoms, is also found in western areas, such as the bronze smiths who produced the beautiful engraved mirrors from Birdlip and Holcombe. Wooden vessels, buckets and handled cups were ornamented with decorated bronze, and one bronze vessel of a type made in western Britain found its way to Poland. Various styles of harness and chariot fittings with simple but effective ornament are found throughout most of the British Isles. Display weapons, especially shields such as that from the Thames at Battersea, demonstrate craftsmanship of the highest order and production of these masterpieces was to continue even after the Roman conquest.

By the time of the Roman conquest, centralised tribal states under kings had become the norm in the east of England. Continental trade may well have been the basis of the power of the elite class, and imported goods and inscribed coinage are largely confined to these areas. Further west and north the hillfort tradition continued, judging from the quality of the native metalwork, under a chiefdom level of society. Though larger tribal entities were recognised, at the time of the Roman conquest these western tribes failed to act as cohesive entities, and among the Durotriges of Dorset, for instance, each hillfort defended itself and fell. Britain by the early first century AD thus presented a patchwork of different social structures, from the centralised state to the low-level chiefdom.

Germany

The highland area of the German Mittelgebirge, extending through Hesse, Thuringia, northern Bavaria and into Bohemia, had been one of the areas in which La Tène culture had developed in the fifth century. A number of hillforts, some of very large size, a hundred or more hectares in area, had been established, some extending back into Hallstatt D. Though not as rich as the Hunsrück-Eifel in La Tène A, occasional gold objects or imported bronze vessels turn up in the richer burials. The defended sites, such as the Steinsburg bei Römhild in Thuringia and Závist in Bohemia, were abandoned during La Tène B, and archaeologically they are virtually a blank for two centuries. This was however the earliest area, extending now further eastwards into Moravia, for the foundation of defended oppida at the end of La Tène C, about the middle of the second century BC. Earlier forts like the Steinsburg and Závist were reconstructed, but new sites were also established such as Stradonice. By the early first century BC many of those sites were thriving centres of trade and industry.

Further north, on the North European Plain, a very different settlement pattern and culture had come into existence. Fortified sites were virtually unknown, and those that did exist were small in size. Settlements above the size of villages were unknown, and compared to central Europe industrial organisation was at a low level. The potter’s wheel, for instance, was not introduced, though known in adjacent areas. Coinage was not adopted, and imported goods from the Mediterranean only rarely found their way this far north. Burials, where known, contain a minimum of gravegoods—usually no more than a rough urn to contain cremated remains. The economy was basically agricultural, the social level essentially tribal or low-level chiefdoms. By the first century BC these groups, from southern Poland to Jutland, had developed burial rites and a distinctive material culture which distinguishes them from their central European neighbours, and which is usually termed ‘Germanic’.

At about the same time this society began to expand. The first evidence is literary—the appearance of the Cimbri and Teutones in central Europe and northern Italy at the end of the second century. Archaeologically it is first detectable inthe mid-first century with the brief appearance of northern style burials and pottery in Hesse, and more permanently in northern Bohemia. The chronological details of the next half century are obscure. Some of the oppida in the German Mittelgebirge were abandoned not long after 50 BC, some survived well into the second half of the first century. One site which may have been an early victim was Manching, and its east gate shows evidence of hasty reinforcement. It has been suggested that it was destroyed in the Roman advance in 15–14 BC, but the brooch series ends too early, and elsewhere the Romans tended to support native urban settlements, even in hostile areas. Manching was probably a deserted waste when the Romans arrived. All we possess for the latest La Tène in Bavaria are a few graves with objects which are more Germanic than central European.

The fate of Bohemia is better documented as there is historical evidence to supplement the archaeology. All five oppida were abandoned at about the same time, in the last quarter of the first century BC. In two cases, Závist and Hrazany, the gates had been blocked by clay revetments which were subsequently destroyed by fire. The culture of the oppida was replaced by one of ‘Germanic’ type with open villages and cremation cemeteries, centred on the agricultural löss soils of northern Bohemia. In 14 BC a Roman-army on the upper Main in northern Bavaria had encountered the tribe of Marcomanni. A decade later they were established in Bohemia under their leader Maroboduus. The only discrepancy between the archaeological and historical sources relates to the origin of the Marcomanni—the material culture most closely resembles that of the middle Elbe rather than the Mittelgebirge. Maroboduus was eventually expelled, and spent the rest of his days in notorious debauchery in Aquileia on a pension from the Roman state.

Further east the situation was more complicated. In southern Poland, western Slovakia and northern Hungary, the material culture was essentially the same as central Europe—the same painted wares, graphite vessels, brooch types. Urbanisation, when it appeared, was different. A small defended hillfort acted as the nucleus around which large open industrial settlements developed, as at Budapest. These sites, such as Zemplín and Nitra, controlled the valley routes into the High Tatry of northern Slovakia, a major source of copper, where there had been a rich and flourishing culture in the late Bronze Age. After this nothing is known until the appearance in the first century BC of small hillforts, around which cluster small open settlements. These clusters include ritual sites, with cremated remains and burnt-offerings, such as fragments of central European brooches, and of the now ubiquitous Campanian bronze vessel. Southern Poland was eventually incorporated into the Germanic area, and individual groups spread as far east as Romania. The Zemplín-Budapest sites, however, remained in occupation for some decades after the Roman conquest of Pannonia, and Germanic metalwork penetrated only slowly into the valleys of the Tatry.

The area, however, was finally dominated by a Roman client kingdom under Vannius. The process of differentiation in the Germanic cultures was already underway in the second half of the first century BC, and the early types of Campanian vessels occur sporadically in graves in Poland and northern Germany. Italian traders are mentioned east of the Rhine, though certain tribes such as the Suebi deliberately excluded them, or only traded booty on a tribal basis. At first we seem to be dealing with individual lineages which were acquiring power rather than specific individuals. The cemetery of Gross Romstedt in Thuringia demonstrates this well. On the lower Elbe males and females were buried in separate cemeteries. Gross Romstedt is an all-male cemetery belonging to the end of the first century BC/early first century AD. The gravegoods seem to represent two different status hierarchies. One is military, and some of the objects are clearly symbolic (miniature spears, empty scabbards, fragment of shields), but the top of the hierarchy is represented by a complete setsword, spear, shield and spur. A second system is represented by more domestic goods, including Campanian bronze vessels. Often individuals have high or low status in both systems, but they do not correspond exactly, and graves rich in domestic goods can be poor in military terms. In Bohemia and Slovakia this took on a different form with certain cemeteries showing considerably greater wealth in imports than others. In Denmark on the other hand, rich imports turn up in a ritual context or in hoards—the silver cauldron from Gundestrup (from Romania), the bronze cauldron from Brå or the wagons from Dejbjerg, both of central European origin, and it is in such contexts that the Campanian bronzes make their appearance.

The move to the Danube frontier proved a major stimulus to this trade, and eventually, in the mid-first century AD, had led to the establishment of small scale chiefdoms in certain areas, not only along the frontier, but in northern Germany and Denmark. Bronze vessels, and especially Roman republican silver coins were the main items traded, but the elite class, characterised by the rich graves of Lübsow type, also contain silver vessels and glassware, as well as gold and silver objects of more local origin. But beyond this the process of centralisation did not go. Even by the end of the late Roman period, hillforts which might act as centres of production were virtually unknown, and urbanism in any form did not appear until the ninth or tenth century AD.

The impact of conquest

The effect of the imposition of Roman power varied both with time and place. The experiences of previous conquests, the increasing professionalisation of the army, and to a lesser extent the administration, meant that the invaders entered with a preconceived model of what was required. This was certainly so in Britain, where by this time the layout of the fort was becoming fairly stereotyped, though with subtle differences which might allow one to distinguish, for instance, a fort of Agricola from one of Severus. But when we turn to Gaul only a few of Caesar’s camps are recognisable, and in small scale excavations in urban contexts, buildings such as barrack blocks even on more permanent bases may not be so readily identifiable as on later British sites. The problems become greater with earlier conquests, as layout of forts, their distribution, even their existence become less predictable. Thus the conquest of Britain can be reconstructed in considerable detail from the archaeology; that of southern France not at all.

The Romans also imposed their ideas of civilisation upon the conquered. Not only did urbanism have to be introduced into areas where none had existed before, but even in areas of advanced culture the settlement pattern eventually had to conform to Roman administrative needs. Old towns were abandoned, new ones founded. This had no connection with previous enmity or assistance—in no case, to my knowledge, was a hostile population removed from a defended town. Witness how Alesia, scene of the final defeat of the Gallic rebellion in 52 BC developed as a major Roman town, whereas Bibracte, capital of Rome’s allies the Aedui, was abandoned within a couple of generations, for Autun (Augusto-dunum), a few miles away.

If we consider Roman priorities in newly conquered territory, the first would be to impose adequate military control. This would involve establishing a hierarchy of sites, with an administrative centre preferably as close to Rome as possible, but in touch with the major military bases. These legionary bases needed to be spread around at key points, but sufficiently close to each other for mutual support if necessary. Lines of communications needed to be secured by subsidiary forts, controlling ports and river crossings. In Britain it was this initial military requirement that virtually dictated the civilian settlement pattern in southeastern England. Settlements were established outside the forts, but when the military moved on the civilians often stayed.

This process was accelerated by the second need—a fast and efficient means of communication. For this roads were constructed from one nodal point to the next, deflected only by problems of terrain, such as river crossings. In this process native settlements were ignored, and even major centres of population by-passed. Southern Tuscany provides the most instructive example. The towns of Etruria possessed an antiquity and prestige equal to that of Rome herself, and had served as market and administrative centres each with their own radiating network of roads. In the third century BC the developing needs of the Roman Empire demanded a network of fast straight roads radiating from Rome. Many of the Etruscan towns were by-passed. Some were actually refounded at nodal points on the road system like Falerii Novi. The ancient town of Veii, on the other hand, continued to act as a market centre, but gradually faded away, and was finally abandoned in the late Roman period. Britain provides similar examples. The native settlements at Canterbury and Leicester developed into Roman towns as they lay at natural strategic points. St Albans merely changed its focus to the area around the ford over the Ver where the Roman fort had been established. Bagendon was abandoned for Cirencester, Maiden Castle for Dorchester, both new sites alongside Roman forts. This basic re-orientation of urban settlement pattern to the needs of Empire in Etruria took about 200 years, in central France about half a century, in south-eastern England it was achieved within a couple of decades.

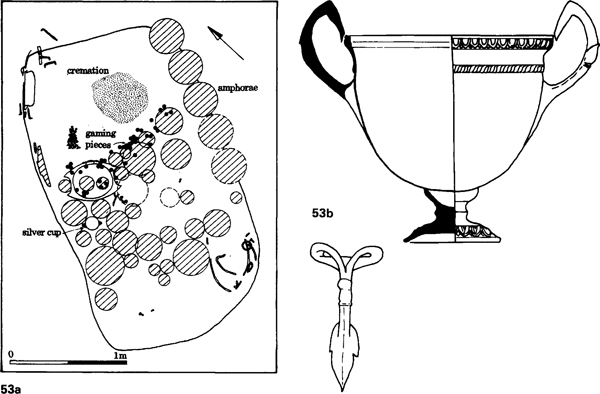

54 The Roman impact on southern Etruria

The effect of the administrative needs of the developing Roman Empire are clearly visible immediately north of Rome. In the seventh-sixth centuries (a) a number of defended settlements such as Veii, Falerii, Narce, and Rome itself were developing as service centres for their surrounding countryside. They were also interlinked with one another, but only by winding cross-country routes. During this period many of these service roads were improved by providing paved surfaces and by the construction of cuttings, and doubtless bridges.

As Rome gradually conquered Etruria in the fourth and third centuries, speed of communication between centres, and especially with Rome itself, became paramount. The earlier routes, the Amerina to Nepi and the Clodia, were mainly improved and straightened service roads, but by the end of the third century fast long-distance routes were being established. The Amerina was extended probably in 241 for access to Umbria, and Falerii Novi was founded on it, replacing the old less accessible centre.

In 220, with the conquest of the Faliscan area, the Via Flaminia was established, the main long-distance route to Rimini and the Adriatic, and probably in 154 BC the Via Cassia, which led to northern Italy via Arrezzo. The new roads chose the most direct routes, and Veii for instance was completely by-passed. By AD 100 (b) former centres such as Falerii and Narce had been abandoned as new centres developed on the main routes, while Veii, though still occupied, was declining, and was itself finally abandoned in the fourth century AD.

From a geographer’s point of view this imposition of the road system brought changes in the types of central place system operating. The oppida and early towns in Tuscany, in central France and south-east England, all equate more or less to the ‘solar central system’: large central places which held monopolies for their territories in providing services. In Tuscany this system had already started to change, and the appearance of secondary centres around the main sites provided a competitive system on Christaller’s ‘marketing principle’. With the imposition of the road pattern in southern England, this produced a competitive system based on the ‘transport principle’. The development of the lower-level central places was encouraged by military and administrative needs: an early network of minor forts replaced by posting stages for official travellers, often at cross-roads which could develop into minor towns.

The Romans also attempted to impose their concept of social organisation upon the conquered— a landowning ‘senatorial’ group, a rich merchant and industrial class of ‘equites’, a free class of artisans and retailers, peasant agricultural communities and a slave class. The landowning elite was the key to successful administration of the towns and it was encouraged to participate in urban life—a contrast with medieval towns which were run by the merchant classes. This elite was already in existence in societies which had already achieved some form of state organisation. At Mont Beuvray their stonebuilt courtyard houses are identifiable within a decade or two of the conquest, and these probably had timber predecessors. In chiefdom societies, the change from power based in lineage to one based on landownership probably represented no great difficulty, given official encouragement. Areas such as Wales, northern England or northern Gaul, where less potential existed for creating such a class, often remained under direct military control.

It was in the second and third classes, those of merchants and artisans, that the greatest adjustment had to be made. The artisan quarters at Mont Beuvray and Manching suggest generally that they suffered a lowly status, and some might even be under direct elite control. The houses are minute, with minimal storage facilities, and contrast strongly with the artisan and traders quarters at the Auerberg, a hill-top Roman trading centre founded in southern Germany at the beginning of the first century AD. It is possible that a merchant class did not even exist in Gallic society, as all the evidence suggests that the profitable foreign trade was in Italian hands even before the conquest. But the trading class was of necessity mobile, and this gap in society was generally filled by outsiders until native society was able to develop.

The extent to which the countryside became fully integrated with the imperial economy also varied considerably. At one end of the scale there is the rapid development of the estates with palatial country houses of the Somme valley, at the other, in a not dissimilar landscape, the peasant farms of the chalk wolds of eastern Yorkshire. This difference has often been simplified into native resistance or acceptance of Romanisation, but it is more likely to be connected with the social structure and rights of land tenure of the indigenous population. Roman archaeologists have tended to lump the natives into broad categories, without investigating the subtle differences in preexisting patterns which dictated subsequent development.

The outward trappings of Roman life, its material culture, were quickly adopted within the limits of each society to accept and afford them. Over much of Temperate Europe trade had already dulled the taste of the elite classes by supplying them with the generally boring mass-produced metalwork of the classical world. The products of late La Tène industry showed even greater poverty of innovation, and only Britain could offer something that was different, exciting and a challenge to Roman taste. But even the Insular Art of the mirrors and shields faltered within a generation before the onslaught of Roman provincial art. Technically the Italian bronze vessels were superior to anything available locally. In the realms of stone and bronze sculpture, increasingly used in religious and official contexts, there was virtually no Celtic tradition, and almost all the figures that grace books on ‘Celtic art’ are either not Celtic, or of Roman date.

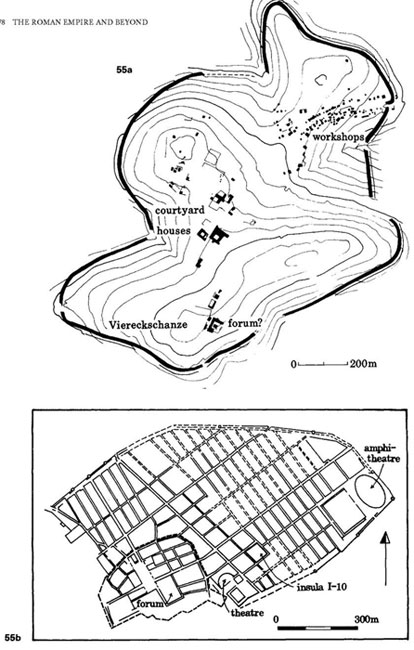

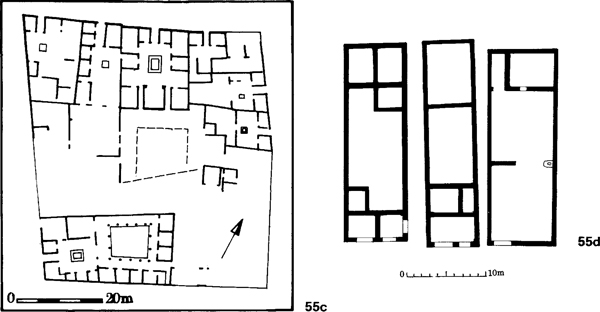

55 Iron Age and Roman towns

Pre-Roman oppida on the continent shared much in common with their Mediterranean counterparts, and at the time of the Roman conquest, the Romans had few problems in imposing their system on the native pattern. In some cases there was even a grid-system of streets, as at Villeneuve-St Germain (fig 46), which need only be provided with paved surfaces, as on the Titelberg in Luxembourg. In others there was no such regularity, as at Mont Beuvray, the ancient Bibracte (a). Here the stone built Roman houses are scattered with no regular system throughout the enclosed area. None the less there are similarities. The small workshops cluster along the main thoroughfare, the elite courtyard houses lie in more secluded areas, away from the hustle and bustle.

Generally the public buildings are at the furthest point from the entrance. In Roman towns with gates on all sides, this usually means the centre of the town, but at Mont Beuvray, with only one entrance, the public buildings are at one end of the site. At Pompeii (b) they are also displaced, but this is because of the complex history of a site which had expanded in size. The forum lay in the centre of the older area.

Similarity of outer form may, however, mask major differences in function. Iron Age oppida tend to be larger than their Roman counterparts. In Britain this is because the settlement is not strongly nucleated, for instance at Colchester (fig 51 a), but this is not true of the continental sites. Manching was much larger than for instance Roman London. Though the former may have had some open spaces, and the latter may have had suburbs, the density of Manching houses suggests it may have had a larger population than Londinium. This may be due to a less developed urban system, in which only major centres existed, and no secondary urban centres to compete with them as occurred in the Roman period.

In Roman towns courtyard houses (c) were occupied by the land-owning elite, and rich merchants, though at Pompeii in the first century AD the landowners start drifting towards their country estates, a trend that became marked in Britain in the fourth century AD. The equivalent structures on the oppida are palisaded enclosures (fig 46), though these show more industrial activity than the classical courtyard houses. This suggests a different organisation of trade and industry, and it may also be reflected in the size of artisan houses. On oppida they tend to be small (fig 46), in Roman towns they have spacious living and storage facilities (d). The status and wealth of the Roman artisan and trader seem to be very different from their Iron Age counterparts.

In pottery styles we can detect a distinctive change, as the Mediterranean range of vessels contrasted with those of Temperate Europe. Bowls and pedestal jar were replaced by plates, jugs and two-handled flasks which carry implications not only of eating habits but of cuisine as well. The Gallo-Belgic pottery industry, with its emphasis on platters, was not merely a revolution in standards and scale of production, but of domestic life as well. In central France, where imitation of Campanian plates started early, and in south-eastern England with its Gallo-Belgic wares, the Roman invasion merely reinforced a trend that had already started. In northern Gaul the change occurred a generation after the conquest, and the spread was by diffusion rather than invasion. The rise of the samian industry in Italy and Gaul brought this Mediterranean style to Wales and northern England, to the limits of the Empire, in areas where pottery had not been in regular use during the Iron Age.

The impact on industry is less easy to measure. Metal and stone extraction were Roman state monopolies, and in Britain, for instance, within a decade the army was involved in lead and silver extraction in the Mendips, and doubtless there was a similar take-over of the iron industry. Industrially the army was probably less influential—of necessity it was largely self-supporting for its metallurgical requirements and technologically the Romans had little to offer the native industries. It did, however, rely considerably on native pottery, where possible using established potteries, even where this meant longdistance transportation. As late as the second century Hadrian’s Wall relied on central France for its fine samian ware, and southern Britain, especially Dorset, for its cooking pots. The textile and leather industries must have received similar financial stimulus. But only in peripheral areas is production likely to have increased noticeably, with the centralisation and rationalisation of artisan production.

Almost universally, however, the imposition of Empire produced a rise in living standards. Peace was imposed, with access to a wider, international market. Standards of housing improved for all classes, not just the ostentatious elite with their hypocausts, mosaics and painted wall plaster. Social differentiation was encouraged and increased, but the artisan class saw a comparable rise in their status and opportunities, and in the long term, it was perhaps only the rural peasantry who suffered. Defeat has its compensations.