8

L2 semantics*

Roumyana Slabakova

Introduction

Few people start learning a second language because it has exotic sounds, or elegant sentence structure. Meaning is what we are after. We would like to understand and to be able to convey thoughts and feelings and observations in another language the way we do in our native language. Ever since Aristotle, linguists have considered language to be the pairing of form (sounds or signs or written strings) and meaning. In this chapter, I examine the road to meaning, that is, how we come to understand and convey meaning in a second language, and where the pitfalls to that goal may lie. I will begin by distinguishing between several types of meanings: lexical, grammatical, and semantic. Next, I will situate them in the language architecture.

When language learners think of semantics, they think almost exclusively of the meaning of words. Semantics, however, involves much more than word meaning. Lexical meanings are stored in our mental lexicon while sentential semantics is compositional, based on combining the meanings of all the words in a sentence and taking their order into account. Take for example the English sentence Someone criticized everyone. Depending on the context, it may mean that there is a certain person who criticized every other person in a situation; in other words, everyone was criticized by one individual. The sentence may also mean that everyone was criticized by some person or other. In the first reading we have one critic, in the second we have possibly many critics. Of these two readings, only the first is available for the equivalent Japanese sentence Dareka-ga daremo-o semeta (Hoji, 1985, p. 336), while the second is not. Although the quantifiers dareka and daremo may be equivalent in meaning to someone and everyone, when used in speech, they give rise to two sentence meanings in English, only one sentence meaning in Japanese. This difference is captured and explained by the rules for calculating sentence meaning in the two languages, and is the research focus of (phrasal) semantics. The Principle of Compositionality (Frege, 1884) ensures that the meaning of the whole sentence (the proposition) is a function of the meanings of the parts and of the way they are syntactically combined.

Grammatical meaning also comes into consideration in calculating sentence interpretation. Consider the two sentences Jane eats meat and Jane ate meat. They contain two identical lexical items (Jane, meat) and the third, the verbal form, encodes a grammatical difference in tense and aspect. We understand that a present characteristic or habitual (but not an ongoing) event is meant by the first utterance (e.g., Jane is not a vegetarian) while a past habitual event or a past completed event is a possible reading of the second.1 Grammatical meanings are mostly encoded in inflectional morphology (-ed for past simple, -s for third-person singular present simple, etc.), for more on their acquisition see Lardiere (Chapter 7, this volume).

When learning a second language, speakers are faced with different acquisition tasks regarding meaning: they have to learn the lexical items of the target language, that is, map linguistic form and lexical meaning one by one. This is certainly a laborious task but learners are facilitated in it by detecting semantic components, or primitives, that can combine to make up lexical meaning. Learning the functional morphology is not qualitatively different: abstracting away from irregular morphology, once learners learn that -ed in English encodes a past habit or a past completed event, they can apply this knowledge to all English regular verbs. As in lexical learning, primitives of grammatical meanings reflected singly or combined in various morphemes help learners in grammar acquisition. The aspectual meanings of habitual, ongoing and completed event constitute examples of such primitive grammatical meanings. Sentential meanings are calculated using universal mechanisms of human language.2 Once the lexical and grammatical meanings are learned, sentential meanings are calculated using a universal procedure and do not constitute a barrier for acquisition. I will explain these claims based on current assumptions of the language architecture.

Historical discussion

Within lexical semantics, one fruitful approach has been to view lexical meanings as made up of primitives, or semantic components. This kind of analysis is called componential analysis (Katz, 1972; Katz and Fodor, 1963). For example, the meaning of wife is viewed as containing the components [human], [female], [adult], [married] while spinster contains the components [human], [female], [adult], [unmarried]. Semantic relations between words such as synonymy, hyponymy, etc., are easily explained by comparing sets of component meanings. Katz and colleagues aimed at establishing a semantic metalanguage through identifying recurring semantic components in words across languages. This type of analysis also highlights the selectional restrictions that we see in combining words into sentences. For example, why is the sentence in (1) perfectly grammatical, but doesn't make any sense? Because the selectional restrictions of the verb and the object require what is spread on the bread to be spreadable, and socks are not.

(1) I spread my warm bread with socks.

Some linguists apply the component analysis of verb meanings to explain syntactic behavior, the intuition behind this approach being that employing semantic primitives in different combinations helps us describe grammatical processes correctly. The gist of this approach (Levin, 1993) is to set up verb classes with distinct syntactic behavior, for example, motion verbs, causative and inchoative verbs, etc. Furthermore, these linguists postulate different linking rules mapping grammatical functions (subject, object) with thematic roles (Agent, Theme, Goal, Location) (Levin and Rappaport Hovav, 1995, 2005). For example, in the locative alternation below, (2a) links the direct object to the Theme argument while (2b) links the object to the Goal argument, and these two linking rules apply to some verbs but not others (3a, b).

(2) a. She sprayed pesticide on the roses. AGENT—THEME—on GOAL

b. She sprayed the roses with pesticide. AGENT—GOAL—with THEME

(3) a. *She covered a blanket on the bed. AGENT—THEME—on GOAL

b. She covered the bed with a blanket. AGENT—GOAL—with THEME

A related research program is that of Talmy (e.g., Talmy, 1985) who studies how semantic components associated with verbs of motion (Figure, Ground, Path, Manner) are combined not only in single words but in phrases, and highlighted their different conflation patterns in different languages.3 Both of these theoretical approaches to lexical semantics have been utilized in L2 acquisition research, to be reviewed in the next section.

Let us consider briefly the essential philosophical divide between theories of semantics without being able to do it justice: the divide between representational and denotational approaches to meaning. Within representational approaches, semanticists like Jackendoff and Cognitive Grammar proponents view semantic analysis as discovering the conceptual structure that underlies language; the search for meaning is the search for mental representations in the human mind/ brain. Denotational, or formal semanticists, on the other hand, argue that understanding the meaning of an utterance is being able to match it with the situation it describes. In Portner's (2005, p. 9) example, one could think of the meaning of dog in terms of the concept DOG in the human mind (the representational approach), or in terms of the real-world animals represented by that word: Spot, Shelby, Ziggy, etc. (the denotational approach).

Formal semantics borrows from logic the notion of truth and the formalisms of propositional logic in order to calculate the truth value of sentences and to characterize semantic relations such as entailment, conjunction and disjunction. The meaning of the sentence is equivalent to its truth conditions. Thus, knowing the meaning of an English sentence such as (4) involves understanding what situation in the world this sentence would correspond to, or in what situation it would be true:

(4) It is sunny and warm in Iowa City.

Topics frequently discussed in formal semantics research and textbooks include the relationship between syntax and semantics (compositionality), types of predicates and modifiers, referring expressions, quantifiers, tense and aspect, modality, discourse representation structures, etc. Unlike cognitive semantics, which is more often than not concerned with lexical semantics (see below), formal semantics is predominately focused on the rules of computing meaning when words combine in sentences and discourse.

Cognitive semantics comes on the representational side of the philosophical debate of what is meaning.4 Thus, proponents of cognitive semantics reject the correspondence theory of truth of formal semanticists (the meaning of a sentence is equal to its truth conditions) and argue that linguistic truth or falsity must be relative to the way an observer construes a situation, based on her or his conceptual framework. In other words, meaning is the product of the human mind. Human beings have no access to a reality independent of human categorization, and the real focus of semantics should be the human conceptual frameworks and how language reflects them. Rooted in this fundamental understanding of meaning, cognitive linguists (Lakoff, Johnson, Fauconnier, Langacker, Talmy, among others) study the mental categories that people have formed in their experience of acting in the world. Important topics in this theoretical approach are metaphor and metonymy as essential elements in our categorization of the world (Lakoff, 1993), image schemas which provide a link between bodily experience and higher cognitive functions (Johnson, 1987), mental spaces that speakers set up to manipulate reference to entities (Fauconnier, 1994), conceptual processes such as viewpoint shifting, figure-ground shifting, scanning and profiling (Langacker, 1993, 1999, 2002). In sum, cognitive semanticists take meaning to be an experiential phenomenon and argue that the human experience of interacting in society motivates basic conceptual structures, which in turn make understanding language possible.

Next, we shall survey another view of semantics, that of Jackendoff's (2002) Parallel Language Architecture. I have chosen to represent this theoretical model in more detail for several reasons. Firstly, Jackendoff's views of semantics, although highly idiosyncratic, bridge formal and cognitive semantics and pay particular attention to where the language variation lies. Secondly, he articulates a coherent picture of the grammar that takes into account psycholinguistic and neurolinguistic views. Most importantly for our purposes in this chapter, his views of the language architecture are used by L2 researchers to inform their research questions.5

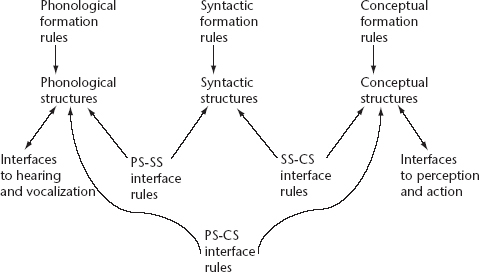

The answer to the question “What is the architecture of the language faculty?” is crucial for understanding the L2 acquisition process, because it bears directly on what has to be learned and what can come for free in acquiring a second language. While looking at Jackendoff's theoretical assumptions, particular attention will be paid to how the different types of meaning (lexical, phrasal) are accessed and computed compositionally (Figure 8.1).

In his 2002 book Foundations of Language, Jackendoff argues that linguistic structure should be viewed as a collection of independently functioning layers, or levels, of structure: phonological structure (PS), syntactic structure (SS), and conceptual structure (CS), see Figure 8.1. In order to make linguistic theory more compatible with findings from neurolinguistics and psycholinguistics, Jackendoff proposes that all three modules (autonomous levels) of the grammar build structure by compositionally combining the units of the particular level. He calls his model the Parallel Architecture.

At each level of the language architecture, a number of rules and constraints operate, allowing the formation of fully-specified structure at that level. These are called integrative processes. SS, for example, works with objects like syntactic trees, their constituents and relations: noun phrases, verb phrases, grammatical features, etc. CS operates with events and states, agents and patients, individuals and propositions. It has three tiers, each of which conveys a different aspect of sentence meaning: predicate logic, reference, topic and focus. Although independent, the three linguistic levels are linked by interfaces. At the interfaces, we have another kind of process, a process that takes as input one type of linguistic structure and outputs another. These are called interface processes. Note that the interface processes are qualitatively different from the integrative ones.

Figure 8.1 Tri-partite parallel architecture

Source: (Jackendoff (2002), Figure 5.4, p. 125)

In this chapter, we focus on the operations at the conceptual level and the syntax-semantics (SS-CS) interface.6 Syntactic structure needs to be correlated with semantic structure and that correlation is not always trivial. The syntactic processor works with objects like syntactic trees and their constituents: noun phrase, verb phrase, etc. In contrast, a semantic processor operates with events and states, agents and patients, individuals and truth of propositions. For example, in the sentence in (5), the teacher is a noun phrase in subject position in the syntax, but an Agent in the semantics.

(5) The teacher ate the apple.

The operations at the interface are limited precisely to those structures that need to be correlated and they do not see other structures and operations (like case-marking) that would have no relevance to the other module.

Core issues

When more than one language come into play, these different computations (lexical, syntactic, conceptual and interface) get even more complicated. Rooted in the language architecture, the core issue of the second language acquisition of meaning is how we come to possess the target meanings and to use them in comprehension and production. That is why it is crucial to identify the locus of language variation. The crucial question for L2 researchers of meaning then is: How much of semantic/conceptual structure is part of Universal Grammar and how much of it may be parameterized? Jackendoff argues that while the content of meaning is the same (concepts and relations between them), different linguistic forms map different natural groupings of meanings. (Jackendoff, 2002, p. 417). Let me illustrate a mismatch at the syntax-semantics interface with marking of politeness in languages like German, French, Bulgarian, and Russian, as opposed to English. German reserves the second-person plural pronoun Sie for situations when there is only one addressee, but the speaker wants to be polite, while using the singular du in all other cases. French, Bulgarian and Russian, among other languages, work similarly to German. English, however, does not reflect this distinction in the morphology of personal pronouns. This does not mean that English speakers have no concept of politeness; they express it differently.

Another example would be the grammaticalization of semantic concepts in inflectional morphology. Compare the marking of tense in English and Mandarin Chinese, Vietnamese and Thai. While English has a separate, productive piece of morphology (-ed) to indicate that an event or state obtained in the past, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Thai do not. This of course does not mean that these speakers have no concept of past; it is just expressed differently. The interpretation of a past event or state is based on the overt aspectual marking, time adverbials and monitoring of the discourse context.

Finally, let us take an example from lexical semantics. In English, verbs that express psychological states can appear with a Theme subject and an Experiencer object, as in (6) while in Chinese this usage is not possible, as (7) illustrates.

(6) The book disappointed Mary.

(7) *Nei ben shu shiwang le ZhangSan

that CL book disappoint PERF Zhang San

“That book disappointed Zhang San.”

Of course, Chinese can express a similar meaning, but with another construction (Juffs, 1996). However, this gap in argument structures presents difficulties for L2 acquisition: in learning English, Chinese speakers have to learn the availability of constructions such as (6); in learning Chinese, English speakers have to de-learn, or acquire the fact that (7) is unavailable.

To recapitulate, most of the language variation in meaning, then, is found at the lexicon-syntax and at the syntax-semantics interfaces. Linguistic semantics is the study of the interface between conceptual structures and linguistic form. The operations at the interface are non-trivial computations. When learning a second language, a speaker may be confronted with different mappings between units of meaning on the conceptual level and units of syntactic structure.

Data and common elicitation measures

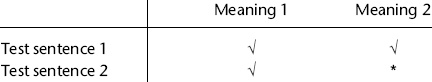

Before we look at concrete linguistic properties and their acquisition, a few remarks on the type of elicitation procedures used in this area of L2 acquisition are in order. How do we gain access to the linguistic interpretations learners attribute to input strings? The tasks for studying interpretive properties have evolved from the staple grammaticality judgment tasks assumed to be the main tool of the generative linguist. Most of the studies looking at L2 semantics use the Truth Value Judgment Task (TVJT) (Crain and McKee, 1985), especially versions adapted to the needs of adult L2 acquisition. In a TVJT, a story is supplied, sometimes in the native language of the learners to establish clear and unambiguous context.7 A test sentence in the target language appears below the story. Learners are asked to judge whether the test sentence is appropriate, or fits (describes) the story well. Participants answer with Yes or No, True or False. Some test sentences are ambiguous so a story supplies only one of their two available interpretations; in such a case, those sentences appear under another story as well, supporting their second interpretation. Typically, stories and test sentences are squared in a 2 × 2 design, giving a quadruple of story-test sentence combinations, as illustrated below (Figure 8.2):

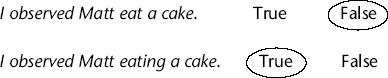

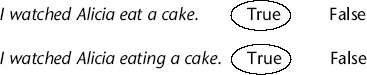

Below is a quadruple of story-test sentence combinations from Slabakova (2003). The experiment investigates whether speakers of English know that a bare infinitive such as eat must refer to a complete event (I saw him eat a cake), while the gerund eating only refers to the process and need not refer to a complete event (I saw him eating a cake, see more on this study later on in this chapter). For lack of space, each story is followed by the two sentences here, but in the actual test each story-sentence pairing is judged on its own.

(9) Matt had an enormous appetite. He was one of those people who could eat a whole cake at one sitting. But these days he is much more careful what he eats. For example, yesterday he bought a chocolate and vanilla ice cream cake, but ate only half of it after dinner. I know, because I was there with him.

Alicia is a thin person, but she has an astounding capacity for eating big quantities of food. Once when I was at her house, she took a whole ice cream cake out of the freezer and ate it all. I almost got sick, just watching her.

The first story in the quadruple in (9) presents an unfinished event (the cake was half-eaten); consequently, only the sentence with the gerund describes it correctly; the sentence with the bare infinitive should be rejected by a speaker who knows the two meanings. The second story in (9) represents a complete event, so both the test sentence with a bare infinitive and the one with a gerund are true. Note that all the test sentences are grammatical under some interpretation in the target language, so learners are not invited to think about the form of the sentences but just to consider their meaning. Nevertheless, this task reveals much about the learners’ grammars, and more specifically, about the interpretations they map onto linguistic expressions. Its main advantage is that learners do not access metalinguistic knowledge that may be due to language instruction but rather engage their true linguistic competence.

Another advantage of the TVJT is that it does away with judgment preference, since the expected answer is categorically True or False, and never both. In this respect, it is interesting to note that White et al. (1997), investigating the interpretation of reflexives in French-English and Japanese-English interlanguage, addressed the methodological question of which task, a TVJT or a picture selection task, better represented the interlanguage competence of the learners. Take the example in (10).

(10) Maryi showed Susanj a portrait of herselfi/j

If we have to find out whether learners interpret herself to refer to Mary or to Susan, or possibly to either one, we can test their interpretation with a picture selection task.8 Participants would be offered a picture in which Mary is showing Susan a prominent portrait of Susan, and a sentence underneath it like the one in (10) without the indexes. Participants have to indicate whether what is going on in the picture matches the sentence. If the learners allow Susan, the object of the sentence, and the reflexive to co-refer, they will answer positively. The same sentence will appear under another picture (not side by side but at another location in the test), this time of Mary showing Susan a portrait of Mary, to check whether learners allow binding to subject. It has been noticed (see White et al., 1997, p. 148 for discussion) that these picture-selection tests reflect, for the most part, the linguistic preferences of the learners. In the case of (10), for example, learners prefer to interpret the reflexive as co-referring with the subject and not the object. This does not mean that the other interpretation is missing from their grammar, but it does mean that experimental results capturing this preference actually underestimate the learners’ competence. White et al. (1997) used both a picture task and a TVJT. Results showed that both native speakers and L2 learners were significantly more consistent in accepting local objects as reflexive antecedents on the TVJT. Since the two tasks are arguably tapping the same linguistic competence, it is clear that the TVJT better deals with licit but dispreferred interpretations of ambiguous sentences, disposing of preferences to a larger degree. However, when we are not dealing with interpretive preferences, the picture selection task is appropriate and very useful for its clarity (see successful application of this task by Hirakawa, 1999; Inagaki, 2001; Montrul, 2000, and White et al., 1999).

A third type of task tapping interpretive judgments (pioneered in Slabakova, 2001, but see also Gabriele and Martohardjono, 2005; Gabriele et al., 2003; Montrul and Slabakova, 2002) is a sentence conjunction judgment task, in which the participants are asked to decide whether the two clauses in a complex sentence go well together or not. For example, take the sentences in (11).

(11) a. Allison worked in a bakery and made cakes.

b. Allison worked in a bakery and made a cake.

The first clause presents context and the felicity of combination of the first and the second clause is being judged. The two clauses in (11a) are a good fit because they represent two habitual activities, while the pairing in (11b) is less felicitous because a habitual and a one-time event are combined. This task could be used in learning situations where the TVJT is not appropriate, although the TVJT is superior to it because it establishes the context in a clearer way.

A fourth type of interpretation task (used in Gürel, 2006; Kanno, 1997; Slabakova, 2005) presents the learners with a test sentence and spells out the three (or more) interpretations, as the example in (12) from Kanno (1997, p. 269) illustrates. In this case, the instructions made clear that participants were allowed to choose both (a) and (b) as possible answers, if this seemed appropriate.

(12) Darei-ga [proi kuruma-o katta to] itta no?

who-NOM car-ACC bought that said Q

“Whoi said (hei) bought a car?”

(a) the same person as dare

(b) another person

This task is also less effective than the TVJT because learners may find it more difficult to externalize how they interpret a particular structure. In a way, this task expects them to think about the meaning of the test sentence and then choose from a couple of provided interpretations, while the TVJT allows them to focus on the story context and then judge the test sentence in a more natural way, abstracting away from its grammatical form. However, Gürel (2006) used this task in conjunction with the TVJT to find out whether her learners allowed pronominal elements to be ambiguous, and her findings on the two tasks were similar, suggesting that her learners were able to overcome the problems mentioned above.

In summary, versions of these four tasks are predominantly used in the L2 literature to probe semantic interpretations. I have argued that the best one is the written TVJT with answers of True and False. Whenever test sentences are not ambiguous, the picture selection task is useful, followed by the sentence conjunction judgment task, and the multiple choice of explicitly spelled-out interpretations task.

Acquisition of lexical meaning

In this section, we turn to explorations of lexical semantic acquisition, both from the point of view of generative grammar and of cognitive semantics. Generative studies of lexical semantics explore the relationship between argument structure, lexical meaning and overt syntax. The theoretical foundation for much of this work is the semantic decomposition of lexical items into primitives or conceptual categories such as Thing, Event, State, Path, Place, Property, Manner (Grimshaw, 1990; Jackendoff, 1990; Pinker, 1989) and linking rules between arguments and thematic roles (Levin and Rappaport Hovav, 1995).In the mapping from the lexicon to syntax, there is a logical problem of L2 acquisition (Juffs, 1996; Montrul, 2001a): L2 learners have to discover the possible mappings between meaning and form in the absence of abundant evidence. There is rarely one-to-one relationship between syntactic frames and available meanings. Though some mappings may be universal, there is a lot of cross-linguistic variation in this respect. To take an example from the English double-object and dative alternation, it may seem that the two syntactic frames that alternate are completely semantically equivalent, but it is not really so.

(13) a. Mary sent the package to John. (Dative syntactic frame)

b. Mary sent the package to Chicago.

c. Mary sent John the package. (Double Object syntactic frame)

d. *Mary sent Chicago the package.

In the double-object frame, it is necessary that at the end of the event, the Goal is actually in possession of the Theme, the package. While this is possible in the case of a Goal such as John, it is not possible for a Goal such as the city of Chicago. Furthermore, it is not the case that every verb that can take a dative argument alternates:

(14) *Sam pushed Molly the package.

For these reasons, it is very easy to overgeneralize lexical alternations and conflation patterns that appear in the native language, and it is not obvious how learners can retract from such overgeneralizations.

Such research questions inspired a lot of experimental studies in the 1980s and through the early 2000s. Mazurkewich (1984), White (1987), Bley-Vroman and Yoshinaga (1992), and Whong-Barr and Schwartz (2002) studied the dative-double object alternations. Findings of these studies are largely consistent with the claim that L2 learners initially adopt L1 argument structures. Cross-linguistic differences in conflation patterns (i.e., what primitives of meaning are conflated in a verb) as studied by Talmy and also illustrated by the Chinese and English examples in (6) and (7) were taken up by Juffs (1996) and Inagaki (2001). Juffs tested Chinese native speakers learning English in China on acceptance and production of psychological, causative, and locative verbs that do not have an equivalent in Chinese. He related these three types of verbs to a lexical conflation parameter. Results suggest that learners at low to advanced levels of proficiency are sensitive to the conflation pattern of English, having acquired structures unavailable in their native language. Inagaki (2001) is a bidirectional (English to Japanese and Japanese to English) study of motion verbs with Goal PPs. Using the same test in both learning directions, a picture followed by sentences to be judged for appropriateness, Inagaki found that there is evidence for directional differences in acquiring L2 conflation patters. English learners of Japanese overgeneralize their native pattern, which is unavailable in Japanese, but Japanese learners of English have no trouble learning the new pattern on the basis of positive evidence. While supporting L1 transfer in learning lexical form-meaning mappings, such results also highlight the issue of the availability of negative evidence in L2 acquisition.

Hirakawa (1999) tested knowledge of the unaccusative-unergative verb distinction9 in the interlanguage of Chinese and English native speakers learning Japanese, using a TVJT with pictures. One of the properties she investigated was whether learners are aware of the fact that combined with unaccusative verbs, the adverb takusan “a lot” modifies the Theme, or underlying object, while combined with unergative verbs, the adverb modifies the Agent, or underlying subject. Again as in Juffs’ and Inagaki's studies, the findings indicated successful acquisition. Finally, in a series of studies, Montrul (2000, 2001b) studied transitivity (the causative-inchoative) alternations as signaled by inflectional morphology in L2 Turkish, Spanish and English. The gist of her findings is that argument structure alternations are crucially dependent on argument-change signaling morphology. Learners who speak a language where alternations are overtly marked in the morphology (a suffix signaling the causative in Turkish, a clitic signaling the inchoative Spanish) are more sensitive to these alternations in a second language than learners whose native language has no overt morphological reflex of the alternation (English). These findings suggest that overt morphology facilitates the acquisition of argument structure alternations, highlighting the logical problem of lexical meaning acquisition in some languages that are poor in such morphology.

Within cognitive semantics, the influential work of Talmy (1991, 2000) has provided inspiration for much L2 acquisition research. Talmy (1991) suggests that languages can be divided into two typological groups depending on how Path of motion is lexicalized: in the verb (verb-framed) or outside the verb (satellite-framed).

(14) Tama-ga saka-o kudaru

Ball-Nom hill-Acc descend

“The ball descends the slope”

(15) The ball rolls down the hill.

In (14), a prototypical example from Japanese, Path is lexicalized in the verb kudaru “descend.” In (15), a corresponding prototypical example from English, Path is lexicalized in the so-called “satellite,” the verb particle down. The reader should be reminded of a very similar property tested by Inagaki (2001). It is important to note a significant difference: while generative studies on lexical meaning typically employ experimental methods for assessing comprehension, cognitive semantics studies typically scrutinize language production, either elicited or from corpora. In a series of studies, Cadierno and colleagues (Cadierno, 2004, 2008; Cadierno and Robinson, 2009; Cadierno and Ruiz, 2006) investigate this type of lexicalization pattern in L2 English and L2 Spanish by learners speaking typologically similar and typologically different languages. Findings indicate that even though intermediate and advanced L2 learners are generally able to develop the appropriate L2 lexicalization patterns, they still seem to exhibit some L1 transfer effects. In particular, in Cadierno and Robinson (2009), the two groups of learners (Danish-to English and Japanese-to-English) demonstrated possible successful acquisition, L1 effects, as well as some effects of task complexity. Brown and Gullberg (2010) argue that learning a second language affects the lexicalization pattern employed in the native language, so language transfer is not only unidirectional.

In a corpus-based study, Lemmens and Perez (2010) investigate the use of Dutch posture verbs (equivalents of stand, lie and sit) by French learners of Dutch. The authors come to the conclusion that the interlanguage system should be treated as a linguistic system in its own right, and that it shows both errors due to L1 transfer, in this case underuse of posture verbs, as well as errors due to overextension of the pattern that learners have acquired in the target language. Looking at the usage of similar verbs (put versus set/lay) in speech analysis as well as in gesture, Gullberg (2009) employed an elicited production task of describing placing events that English-native learners of Dutch have just seen on video. Their production was video-recorded. Gullberg also argues that her subjects show some sensitivity to the target semantic patterns of the L2.

In sum, research within cognitive linguistics more often scrutinizes production rather than measures comprehension as generative lexical semantic research does. Nevertheless, both research traditions come to very similar conclusions: lexical semantics presents significant difficulties to L2 learners when they have to restructure their lexical knowledge; however, these difficulties are not insurmountable and successful acquisition is attested.

Acquisition of sentence-level meaning

In their search of L2 (grammatical) meaning, learners can encounter complete overlap of L1 and L2 syntactic and conceptual structures. They can also encounter differences in interpretation which are due only to syntactic differences. I will illustrate with a property from French, which allows the interrogative combien “how many” to form either continuous or discontinuous constituents with its restriction de livres “of books” (Dekydtspotter, 2001; Dekydtspotter et al., 2001).

(16) Combien de livres est-ce que les étudiants achètent tous?

how many of books is it that the students buy all

“How many books are the students all buying?”

(17) Combien est-ce que les étudiants achètent tous de livres?

how many is it that the students buy all of books

“How many books are the students all buying?”

Although the questions in (16) and (17) look much alike, considering that French allows discontinuous constituents, their interpretive differences are reflected in the possible answers to them. Let us consider the following situation. There are two French students studying English literature, Jerome and Jacqueline, and they are buying a number of English books, with some overlapping titles. Jerome is buying Moby Dick, Little Women, and The Age of Innocence, while Jacqueline is buying Moby Dick, Little Women, and The Scarlet Letter. In this situation, one can truthfully answer both (16) and (17) with “three,” that is, Jerome is buying three books and Jacqueline is buying three books. This is known as the distributive (books per student) answer. However, (16) can also be answered with “two,” because there are two books that both Jerome and Jacqueline are buying in common, namely Moby Dick, and Little Women. This answer is known as the common answer. The discontinuous combien question in (17), however, cannot receive the common answer, only the distributive answer.

The explanation of these interpretive differences involves the interaction of the universal rules of semantic calculation and some language-specific syntactic properties of the French sentence. For example, French allows quantifiers such as combien “how many” to be displaced from its restriction de livres “of books.” Note that this property is not difficult to deduce, since it is reflected in the word order of French questions, and in particular, in the word order of the test sentences in the experiment.

In order to test knowledge of this extremely subtle contrast, Dekydtspotter (2001) followed the trade-mark experimental designs of these researchers, namely, stories in the L1 of the learners, followed by a question and an answer in French. The participants had to indicate whether the supplied answer was appropriate for the question and the story. The quadruple design was implemented, wherein continuous and discontinuous questions were paired with distributive and common answers. Results showed that distributive answers were overwhelmingly preferred by the native speakers (see Dekydtspotter, 2001 for an explanation of this fact in terms of parsing complexity measured by the number of reanalysis steps that each interpretation necessitates). However, even with the depressed acceptance of the common answers, the native speakers demonstrated a significant contrast between continuous and discontinuous constructions, and between the two meanings paired with the discontinuous questions. The same crucial contrast appeared in the performance of the advanced learners. Results for the intermediate learners revealed a thoroughly different pattern. First of all, they did not show the expected contrast between the two interpretations of discontinuous interrogative and their means were in the wrong direction: higher acceptance for common answers. Secondly, they clearly preferred continuous interrogatives, probably because discontinuous interrogatives were not yet part of their (productive) grammar. Thus the relevant interpretive asymmetry was not attested in the grammar of intermediate French learners but was attested in the grammar of native speakers and advanced learners.

In sum, the interpretive mismatch exemplified above and those used in other experiments are based on quite complex syntax, in the sense that sentences involve less frequent constructions (double genitives in Dekydtspotter et al., 1997; discontinuous constituents in Dekydtspotter and Sprouse, 2001; quantifiers at a distance in Dekydtspotter et al., 1999/2000, scrambling10 in Hopp, 2007; Song and Schwartz, 2009; Unsworth, 2005, etc.). Very often the native speakers in these experiments show far lower than the acceptance rates we are used to seeing in the L2 literature. In many cases, there are alternative ways of articulating the same message, making the tested constructions dispreferred. In most cases, the properties are not supported by positive evidence in the input; in other words, they present a poverty of the stimulus learning situations. However, at the syntax-semantics interface, these same properties do not present much difficulty, as there are no mismatches. Once learners have acquired the relevant functional lexicon item and have constructed the right sentence representation, the presence or absence of semantic interpretation follows straightforwardly without any more stipulations. In most studies11 investigating such learning situations, learners demonstrate that a contrast exists in their grammar between the allowed and disallowed interpretations.

In contrast, the other learning situation that arises in acquiring L2 meanings is not characterized by poverty of the stimulus. The syntactic structure presents less difficulty to the learners. Quite often, these studies deal with properties related to truth-conditional meanings of common morphological forms, like the preterite and imperfect tenses in Spanish-English interlanguage (Montrul and Slabakova, 2002, 2003; Slabakova and Montrul, 2003), progressive tenses in Japanese-English interlanguage (Gabriele, 2005), reflexive pronouns in Japanese/French-English interlanuaage (White et al., 1997), aspect-marking in Bulgarian-English (Slabakova, 2001) and English-Russian (Slabakova, 2005) interlanguage, article semantics in Korean/Russian-English interlanguage (Ionin et al., 2004). Not surprisingly, native speakers in these experiments show the regular range of accuracy in the study of L2 acquisition (80–90 percent). The learning challenges lie, however, at the syntax-semantics mapping. Learners have to figure out what morphological forms are mapped onto what meanings in the target language, since there is no one-to-one correspondence at the syntax-semantics interface. When we consider results at all levels of proficiency from beginner to near-native, what crystallizes is that knowledge of these properties emerges gradually but surely. I will illustrate this learning situation with an aspectual syntax-semantics mismatch between Bulgarian and English.

Slabakova (2003) investigates linguistic properties related to grammatical aspect. English differs from German, Romance, and Slavic with respect to the semantics of the present tense, which can denote a present habit but not an ongoing event, see examples in (18).

| (18) | a. *She eats an apple right now. | #Ongoing event |

| b. She is eating an apple right now. | Ongoing event | |

| c. She eats an apple (every day). | Habitual series of complete events |

Furthermore, the English bare infinitive denotes not only the processual part of an event but includes the completion of that event.

| (19) | a. I saw Mary cross the street. | (completion entailed) |

| b. I saw Mary crossing the street. | (no completion entailed) |

In trying to explain the facts illustrated in (18)–(19), many researchers have noticed that English verbal morphology is impoverished. For example, lexical roots such as dress or play can be verbs or nouns. The experimental study adopts Giorgi and Pianesi's (1997) proposal. English verbs, they argue, are “naked” forms that can express several verbal values, such as the bare infinitive, the first- and second-person singular, and the first- second- and third-person plural. Giorgi and Pianesi (1997) propose that verbs are categorially disambiguated in English by being marked in the lexicon with the aspectual feature [+perf], standing for “perfective.” In Romance, Slavic, and other Germanic languages, on the other hand, all verbal forms have to be inflected for person, number, and tense. Thus, nouns and verbs cannot have the same forms. Bulgarian verbs are associated with typical verbal features as [+V, person, number] and they are recognizable and learnable as verbs because of these features. Bulgarian verbs are therefore not associated with a [+perf] feature. Consequently, Bulgarian equivalents to bare infinitives do not entail completion of the event, as (20) illustrates.

(20) Ivan vidja Maria da presiča ulicata. (no completion entailed)

Ivan saw Maria to cross street-DET

“John saw Mary crossing the street.”

Thus, Bulgarian and English exhibit a contrast in grammatical aspect. In the acquisition of English by Bulgarian native speakers, then, the learning task is to notice the trigger of this property: the fact that English inflectional morphology is highly impoverished, lacking many person-number-tense verb endings. The property itself, if Giorgi and Pianesi are correct, is the [+perf] feature that is attached to English eventive verbs in the lexicon. Knowledge of this property will entail knowledge of four different interpretive facts: (1) bare verb forms denote a completed event; (2) present tense has only habitual interpretation; (3) the progressive affix is needed for ongoing interpretation of eventive verbs; (4) states in the progressive denote temporary states. This is a syntax-semantics mismatch that relates a minimal difference between languages—the presence or absence of a feature in the lexicon—to various and superficially not connected interpretive properties. Importantly, of the four semantic properties enumerated above, the second, third, and fourth are introduced, discussed, and drilled in language classrooms, but the first one is not explicitly taught.

A hundred and twelve Bulgarian learners of English took part in the experiment, as well as 24 native speaker controls. All participants completed a production task to ascertain knowledge of inflectional morphology and a Truth Value Judgment Task with a story in their native language and a test sentence in English. Example (9) above illustrates a test quadruple.

Results on the acquisition of all four semantic properties pattern in the same way: initial L1 transfer and subsequent successful acquisition are clearly attested in the data. Advanced learners are even more accurate than native speakers in their knowledge that an English bare verb denotes a complete event, knowledge that cannot be transferred from the L1, as example (20) indicates. Considering the impact of the instruction variable, analysis of variance indicated that all groups performed equally well on all conditions. The theoretical implication of this finding is that all semantic effects of learning the trigger (English verbs are morphologically impoverished) and the related property ([+perf] feature attached to verbs in the lexicon) appear to be engaged at the same time. Even untaught syntax-semantics mismatches are learnable to a native-like level.

In this section, illustrative studies of two types of learning situations were reviewed. These are representative of a range of recent studies on the L2 acquisition of the syntax-semantics interface (for an extensive review, see Slabakova, 2006, 2008). Importantly, both types of studies attest to the fact that acquisition of meaning is not problematic in the second language, once the inflectional morphology is learned (see the Bottleneck Hypothesis presented in the next section).

Applications

It is fairly common to assert that the generative approach to L2 acquisition does not really have any predictions to make about teaching a language. As a cognitive discipline within a theoretical perspective inherently not interested in the process of instructed learning, this approach has frequently turned its attention to the L2 acquisition of subtle phenomena that are never discussed in language classrooms and that, in some cases, language teachers have no explicit knowledge of. Generative studies of L2 acquisition rarely incorporate classroom instruction as part of their design, the studies by White and colleagues (White, 1991) are a notable exception. Thus, it is generally believed that the generative framework has nothing valuable to offer to language teachers. In a break with tradition, however, I argue that the recent generative L2 research does have a pedagogical implication.

In this chapter, it was argued that the meaning computation mechanism is universal and should come for free in second language acquisition, transferred from the native language or Universal Grammar. What is to be learned then, and what should our instructional effort focus on? In both learning situations outlined above, the road to meaning passes through grammatical (inflectional) morphology and its features. In the French combien questions (Dekydtspotter, 2001; Dekydtspotter et al., 2001), idiosyncratic properties of French inflectional morphology allow the possibility of discontinuous syntax, which in turn allows the different interpretations of the continuous and discontinuous combien questions. In the Bulgarian-English grammatical aspect contrast (Slabakova, 2003), the analysis argues for a [+perf] feature of English bare verbs, absent in the Bulgarian grammar, which brings forward the various interpretive differences between the two languages. Based on such considerations, Slabakova (2008) formulates the Bottleneck Hypothesis, which states that inflectional morphemes and their formal features present the most formidable challenge to learners while syntax and phrasal semantics pose less difficulty. The inflectional morphemes carry the features that are responsible for syntactic and semantic differences among languages of the world, so it is logical that once these morphemes and their features are acquired, the other linguistic properties (word order, interpretation, etc) would follow smoothly. The numerous empirical studies on the L2 acquisition of semantic properties, including the ones summarized in this chapter, indicate that there is no critical period for the acquisition of meaning (Slabakova, 2006). If inflectional morphology is the real bottleneck of L2 acquisition, what are the implications for teaching second languages?

In language classrooms, teaching techniques that emphasize communicative competence (Canale and Swain, 1980; Savignon, 1983) are very popular these days. Such techniques encourage learners to use context, world knowledge, argument structure templates, and other pragmatic strategies to comprehend the message, capitalizing on the fact that learners almost certainly use their expectations of what is said to choose between alternative parses of a sentence. In fact, Clahsen and Felser's (2006) Shallow Structure Hypothesis proposes that context, pragmatic knowledge, and argument structure are the only processing strategies available to adult learners. However, many second language researchers question the direct connection between comprehending the L2 message and figuring out how the L2 syntax works (Cook, 1996, p. 76; Gass and Selinker, 2008, p. 376). It is believed that some attention to, or focus on, grammatical form is beneficial and necessary for successful learning. In this respect, communicative competence approaches—with their exclusion of focus on form—may not be the best way to accomplish the ultimate goal of second language learning: building a mental grammar of the target language.

The Bottleneck Hypothesis supports such a conclusion and endorses increased emphasis on practicing grammar in the classroom, of course combined with other communication-based classroom activities. The functional morphology in a language has some visible and some hidden characteristics. It may have phonetic form, and if it does, its distribution is in evidence and learnable. Secondly, it carries syntactic features that are responsible for the behavior of other, possibly displaced elements and phrases in the sentence. Thirdly, it carries one or more universal units of meaning. While the first trait of functional morphology is observable from the linguistic input, the second and third characteristics may not be so easy to detect. The inflectional morphology presents considerable difficulty and leaves residual problems even in very advanced speakers, although there is a huge amount of evidence for it in the input to which the learners are exposed. On the other hand, semantic properties of the sort discussed in this chapter, that learners and teachers are not aware of and that are certainly obscure, are acquired without a problem. This discrepancy powers the Bottleneck Hypothesis. It is suggested here that practicing the inflectional morphology in language classrooms should happen in meaningful, plausible sentences where the syntactic effects and the semantic import of the morphology are absolutely transparent and non-ambiguous. Some controlled repetition of the inflectional morphology is inevitable if the form has to move from the declarative to the procedural memory12 of the learner and then get sufficiently automatic for easy lexical access. Practicing inflectional morphology in context should be very much like lexical learning (because it is lexical learning), and, as everybody who has tried to learn a second language as an adult (or even a teenager) knows, no pain—no gain. This claim is obviously not new. Although rooted in a different theoretical foundation, the Bottleneck Hypothesis is akin in its pedagogical implications to the Focus on Form approach (Doughty, 2001; papers in Doughty and Williams, 1998), the Input Processing theory of VanPatten (1996, 2007, Chapter 16, this volume) and the Skill Acquisition theory of DeKeyser (1997, 2007).

Furthermore, we have been discussing ambiguous and polysemous morphemes in this chapter (for more discussion of the syntax-morphology interface, see Lardiere, Chapter 7, this volume, and Lardiere, 2009). Some meanings encoded in a morpheme appear with less frequency in the input, or in a more complex combination with other morphemes and lexical items. For example the progressive form be + -ing has the common “ongoing” meaning, but it denotes a “temporary state” when combined with a stative verb, the latter meaning being rarer in the input. Hence, the second morpheme meaning needs a clear presentation in disambiguating context and subsequent practice in addition to the first meaning. It is also important for teachers to highlight the connection between the two or more meanings, both in presentation and in practice. For this reason, teachers must be appropriately trained to be aware of grammatical morpheme polysemy (see also Lardiere, Chapter 7, this volume). Importantly, in acquisition research as well as in language teaching, we should always think of a morpheme as having phonetic form, carrying syntactic features and denoting potentially more than one meaning.

Future directions

Depending on the theoretical model, information structure (a.k.a. new and old information, topic and focus, theme and rheme) falls within the provenance of semantics (as in Jackendoff, 2002) or is at the syntax-pragmatics interface (as in Reinhart, 2006). Acquisition of the way the target language marks topic and focus is one of the hottest topics in current generative SLA research. The concepts of topic and focus are universal but languages may use word order, clitic-doubling, intonation, or a combination of all these to mark them. The logical prediction is that successful acquisition will be possible, as with the acquisition of purely semantic properties. Very recent work by Valenzuela (2006), Ivanov (2009), and Fruit Bell (2009) suggests that this is indeed the case.

However, a recent version of the Interface Hypothesis (Tsimpli and Sorace, 2006) proposes a principled distinction between internal interfaces, those between narrow syntax and the other linguistic modules (phonology, morphology, semantics) and external interfaces, those between syntax and other cognitive modules. As a primary example of such an external interface, researchers have concentrated on the syntax-discourse/pragmatics interface. The claim is that this interface is the major source of difficulty, causing delays in L1 acquisition, failure in bilingual and L2 acquisition, as well as indeterminacy of judgments and residual optionality even at near-native levels of acquisition. Research has supported this claim mostly with data on syntactic and discourse constraints on the usage of null subjects (Belletti et al., 2007). It remains an open question, however, whether this theoretical proposal can be substantiated with data from other phenomena at the syntax-discourse interface and not just null subject use.

A fascinating research question at the syntax-semantics interface is to compare and contrast child L1, child L2, and adult L2 acquisition of semantic properties. A recent experimental study, Song and Schwartz (2009), investigates the development of Korean wh-constructions with negative polarity items (e.g., anyone) in these three populations and finds similar developmental paths. The authors argue that their findings militate against the Fundamental Difference Hypothesis (Bley-Vroman, 1990, see also Studies in Second Language Acquisition 2009 special issue). More generally speaking, whenever a specific property becomes part of the child grammar rather late (for example, scrambling is acquired at the age of 7 to 9), the question arises of whether this is due to some cognitive delay in child development or to difficulties in processing the specific construction. Comparing the ways children and adults acquire the same construction can tease these two explanations apart, because adults are already completely cognitively developed. If research finds a similar developmental pattern in children and adult L2 learners, then only processing remains as a viable explanation (Schwartz, 2003; Unsworth, 2005).

The final research question that I offer here concerns the relative difficulty of acquiring a meaning that is signaled by context versus the same meaning signaled by inflectional morphology. Let us take the example of tense marking in Mandarin Chinese, Vietnamese, or Thai introduced earlier. The meaning of past event or state has to be expressed in any language. While the English learner is exposed to (roughly) one meaning reflected in one morpheme (if we disregard irregular verbs), the Mandarin, Vietnamese, and Thai learner has to pay attention to context and the various lexical means of marking temporality. It is logical to predict that the English learner would arrive at a form-meaning mapping sooner and more easily than the Mandarin/Vietnamese/Thai learner. On the other hand, beginning learners of languages with tense morphology go through a stage where they use lexical means (such as adverbs and adverbial phrases) before they start utilizing the morphological means of tense marking (Dietrich et al., 1995). This fact suggests that lexical marking of tense may be easier. This remains one of the many intriguing puzzles at the interface between morphosyntax and semantics that awaits its researchers.

Notes

* I am grateful to Susan Gass and Alison Mackey for inviting me to contribute to this handbook and for editing suggestions. Thanks go to all my students at the University of Iowa for being interested in and enthusiastic about generative L2A, and for asking hard questions. I am especially grateful to Jacee Cho and Tania Leal Mendez for reading and commenting on this chapter.

1 The context or the rest of the sentence will disambiguate: Jane ate meat last night versus Jane ate meat when she was younger.

2 I am abstracting away from pragmatic meaning, which is arguably regulated by a different module of the language architecture (Reinhart, 2006). See Bardovi-Harlig's chapter on the L2 acquisition of pragmatics, Chapter 9, this volume.

3 Jackendoff ’s Conceptual Semantics (Jackendoff, 1972, 1983, 1990) is another decompositional theory of meaning. Since the meaning of the sentence is composed from word meanings, a good deal of attention is paid to lexical semantics in his approach. See his language architecture proposal later in this section. Other influential approaches in this vein include Pustejovsky's Generative Lexicon (Pustejovsky, 1995) and Role and Reference Grammar (Van Valin, 2005).

4 For a good introduction to cognitive semantics, see Chapter 11 in Saeed (2009).

5 For more discussion on this topic, see Slabakova (2008), Chapter 2.

6 Lexical items contain the same three structures, CS, SS, and PS, in miniature.

7 Dekydtspotter and Sprouse pioneered the presentation of the story in the native language, see also Borgonovo et al., 2006; Gürel, 2006; and Slabakova, 2003.

8 See a different version of this task in Belletti et al. (2007), where one test sentence appears above three pictures illustrating three different interpretations.

9 Unaccusative verbs are intransitive verbs whose only argument is a Theme, or underlying object (e.g., fall, arrive), while unergative verbs are intransitives with an Agent argument (e.g., laugh, sneeze).

10 “Scrambling” involves the displacement of constituents from their usual position in the sentence. It happens in languages without fixed word order and is determined mainly by pragmatic considerations such as topic and focus.

11 Hawkins and Hattori (2006) is an exception.

12 Declarative memory is the memory for repeatedly encountered facts and data such as who is president, what is the square root of 25, and where you were born. Procedural memory, by contrast, is memory for sequences of events, processes, and routines. Procedural memory is often not easily verbalized, but can be used without consciously thinking about it; procedural memory can reflect simple stimulus-response pairing or more extensive patterns learned over time. In contrast, declarative memory can generally be put into words.

References

Belletti, A., Bennati, E., and Sorace, A. (2007).Theoretical and developmental issues in the syntax of subjects: Evidence from near-native Italian. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 25, 657–689.

Bley-Vroman, R. (1990).The logical problem of foreign language learning. Linguistic Analysis, 20, 3–49.

Bley-Vroman, R. and Yoshinaga, N. (1992).Broad and narrow constraints on the English dative alternation: Some fundamental differences between native speakers and foreign language learners. University of Hawai'i Working Papers in ESL, 11, 157–199.

Borgonovo, C., Bruhn de Garavito, L., and Prévost, P. (2006). Is the semantics/syntax interface vulnerable in L2 acquisition? Focus on mood distinctions in relative clauses in L2 Spanish. In V. Torrens and L. Escobar (Eds.), The acquisition of syntax in romance languages (pp. 353–369). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Brown, A. and Gullberg, M. (2010). Changes in encoding of Path of motion in a first language during acquisition of a second language. Cognitive Linguistics, 21(2), 263–286.

Cadierno, T. (2004). Expressing motion events in a second language: A cognitive typological perspective. In M. Achard and S. Niemeier (Eds.), Cognitive linguistics, second language acquisition and foreign language teaching (pp. 13–49). Berlin: Mouton deGruyter.

Cadierno, T. (2008). Learning to talk about motion in a foreign language. In P. Robinson and N. C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition (pp. 239–274). London: Routledge.

Cadierno, T. and Robinson, P. (2009). Language typology, task complexity and the development of L2 lexicalization patterns for describing motion events. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 7, 245–276.

Cadierno, T. and Ruiz, L. (2006). Motion events in Spanish L2 acquisition. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 4, 183–216.

Canale, M. and Swain, M. (1980).Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1–47.

Clahsen, H. and Felser, C. (2006). Grammatical processing in language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 27, 3–42.

Cook, V. (1996). Second language learning and language teaching (Second Edition). London: Edward Arnold.

Crain, S. and McKee, C. (1985). The acquisition of structural restrictions on anaphora. In Proceedings of NELS 16, Amherst, MA: GLSA, University of Massachusetts.

DeKeyser, R. (1997). Beyond explicit rule learning: Automatizing second language morphosyntax. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, 195–221.

DeKeyser, R. (2007). Skill Acquisition Theory. In B. VanPatten and J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition (pp. 97–113). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dekydtspotter, L. (2001). Mental design and (second) language epistemology: Adjectival restrictions of wh-quantifiers and tense in English-French interlanguage. Second Language Research, 17, 1–35.

Dekydtspotter, L. and Sprouse, R. (2001). Mental design and (second) language epistemology: Adjectival restrictions of wh-quantifiers and tense in English-French interlanguage. Second Language Research, 17, 1–35.

Dekydtspotter, L., Sprouse, R., and Anderson, B. (1997). The Interpretive Interface in L2 Acquisition: The Process-Result Distinction in English-French Interlanguage Grammars. Language Acquisition, 6, 297–332.

Dekydtspotter, L., Sprouse, R., and Swanson, K. (2001). Reflexes of the mental architecture in Second Language Acquisition: The interpretation of discontinuous Combien extractions in English-French interlanguage. Language Acquisition, 9, 175–227.

Dekydtspotter, L., Sprouse, R., and Thyre, R. (1999/2000). The interpretation of quantification at a distance in English-French interlanguage: Domain-specificity and second language acquisition. Language Acquisition,, 8, 265–320.

Dietrich, R., Klein, W., and Noyau, C. (1995). The acquisition of temporality in a second language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Doughty, C. (2001). Cognitive underpinnings of focus on form. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language acquisition (pp. 206–257). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doughty, C. and Williams, J. (Eds.) (1998). Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fauconnier, G. (1994). Mental spaces: Aspects of meaning construction in natural language (Second Edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frege, G. (1884/1980). The foundations of arithmetic. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Fruit Bell, M. (2009). Divergence at the syntax-discourse interface: Evidence from the L2 acquisition of contrastive focus in European Portuguese. In A. Pires and J. Rothman (Eds.), Minimalist inquiries into child and adult language acquisition: Case studies across Portuguese (pp. 197–219). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Gabriele, A. (2005). The acquisition of aspect in a second language: a bidirectional study of learners of English and Japanese. Unpublished PhD thesis. The City University of New York.

Gabriele, A. and Martohardjono, G. (2005). Investigating the role of transfer in the L2 acquisition of aspect. In L. Dekydtspotter et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th generative approaches to second language acquisition conference (GASLA 2004) (pp. 96–110). Sommerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Gabriele, A., Martohardjono, G., and McClure, W. (2003). Why dying is just as difficult as swimming for Japanese learners of English. ZAS Papers in Linguistics, 29, 85–104.

Gass, S. and Selinker, L. (2008). Second language acquisition: An introductory course. New York and Abingdon: Routledge (Taylor and Francis).

Giorgi, A. and Pianesi, F. (1997). Tense and aspect: From semantics to morphosyntax. New York: Oxford University Press.

Grimshaw, J. (1990). Argument structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gullberg, M. (2009). Reconstructing verb meaning in a second language. How English speakers of L2 Dutch talk and gesture about placement. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 7, 221–244.

Gürel, A. (2006). L2 acquisition of pragmatic and syntactic constraints in the use of overt and null subject pronouns. In R. Slabakova, S. Montrul, and P. Prévost (Eds.), Inquiries in linguistic development: Studies in honor of Lydia White (pp. 259–282). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hawkins, R. and Hattori, H. (2006).Interpretation of English multiple wh-questions by Japanese speakers: A missing uninterpretable feature account. Second Language Research, 22, 269–301.

Hirakawa, M. (1999). L2 acquisition of Japanese unaccusative verbs by speakers of English and Chinese. In K. Kanno (Ed.), The acquisition of Japanese as a second language (pp. 89–113). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hoji, H. (1985). Logical form constraints and configurational structures in Japanese. Unpublished PhD dissertation. University of Washington.

Hopp, H. (2007). Ultimate attainment at the interfaces in second language acquisition: Grammar and processing. PhD dissertation. University of Groningen. Groningen Dissertations in Linguistics 65.

Inagaki, S. (2001). Motion verbs with goal PPs in the L2 acquisition of English and Japanese. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 23, 153–170.

Ionin, T., Ko, H., and Wexler, K. (2004). Article semantics in L2 acquisition: The role of specificity. Language Acquisition, 12, 3–69.

Ivanov, I. (2009). Second language acquisition of clitic doubling in L2 Bulgarian: A test case for the Interface Hypothesis. Unpublished PhD dissertation. University of Iowa.

Jackendoff, R. (1972). Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jackendoff, R. (1983). Semantics and cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jackendoff, R. (1990). Semantic structures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jackendoff, R. (2002). Foundations of language. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, M. (1987), The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination and reason. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Juffs, A. (1996). Learnability and the lexicon: Theories and second language acquisition research. John Benjamins: Amsterdam.

Kanno, K. (1997). The acquisition of null and overt pronominals in Japanese by English speakers. Second Language Research, 13, 299–321.

Katz, J. (1972). Semantic theory. New York: Harper and Row.

Katz, J. and Fodor, J. (1963). The structure of a semantic theory. Language, 39, 170–210.

Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (pp. 205–251). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Langacker, R. (1993). Reference-point constructions. Cognitive Linguistics, 4, 1–38.

Langacker, R. (1999). Grammar and conceptualization. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Langacker, R. (2002). Concept, image, symbol: The cognitive basis of grammar (Second Edition). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lardiere, D. (2009). Some thoughts on the contrastive analysis of features in second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 25, 173–227.

Lemmens, M. and Perez, J. (2010). On the use of posture verbs by French-speaking learners of Dutch: A corpus-based study. Cognitive Linguistics, 20(2), 315–347.

Levin, B. (1993). English verb classes and alternations. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Levin, B. and Rappaport Hovav, M. (1995). Unaccusativity: A the syntax-semantics interface. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Levin, B. and Rappaport Hovav, M. (2005). Argument realization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mazurkewich, I. (1984) The acquisition of the dative alternation by second language learners and linguistic theory. Language Learning, 34, 91–109.

Montrul, S. (2000). Transitivity alternations in L2 acquisition: Toward a modular view of transfer. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 22, 229–273.

Montrul, S. (2001a). Introduction. Special issue on the lexicon in SLA. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 23, 145–151.

Montrul, S. (2001b). Agentive verbs of manner of motion in Spanish and English as a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 23, 171–206.

Montrul, S. and Slabakova, R. (2002). Acquiring morphosyntactic and semantic properties of preterite and imperfect tenses in L2 Spanish. In A. -T. Perez-Leroux and J. Liceras (Eds.), The acquisition of Spanish morphosyntax: The L1–L2 connection (pp. 113–149). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Montrul, S. and Slabakova, R. (2003).Competence similarities between native and near-native speakers: An investigation of the preterite/imperfect contrast in Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 25, 351–398.

Pinker, S. (1989). Learnability and cognition: The acquisition of argument structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Portner, P. (2005). What is meaning: Fundamentals of formal semantics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Pustejovsky, J. (1995). The generative lexicon. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Reinhart, T. (2006). Interface strategies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Saeed, J. (2009). Semantics (Third Edition). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Savignon, S. (1983). Communicative competence: Theory and classroom practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Schwartz, B. (2003). Child language acquisition: Paving the way. In B. Beachley, A. Brown, and F. Conlin (Eds.), Proceedings of the 27th Boston University Conference on Language Development (Vol. 1, pp. 26–50). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Slabakova, R. (2001). Telicity in the second language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Slabakova, R. (2003). Semantic Evidence for Functional Categories in Interlanguage Grammars. Second Language Research, 19(1), 42–75.

Slabakova, R. (2005). What is so difficult about telicity marking in L2 Russian? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 8(1), 63–77.

Slabakova, R. (2006). Is there a critical period for the acquisition of semantics. Second Language Research, 22(3), 302–338.

Slabakova, R. (2008). Meaning in the second language. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Slabakova, R. and Montrul, S. (2003). Genericity and aspect in L2 acquisition. Language Acquisition, 11, 165–196.

Song, H. -S. and Schwartz, B. D. (2009).Testing the fundamental difference hypothesis: L2 adult, L2 child and L1 child comparisons in the acquisition of Korean wh-constructions with negative polarity items. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 31, 323–361.

Talmy, L. (1985). Lexicalization patterns: Semantic structure in lexical forms. In T. Shopen (Ed.), Language typology and syntactic description (Vol. 3, pp. 57–149). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Talmy, L. (1991) Path to realization: A typology of event conflation. In Proceedings of the 17th annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistic Society (pp. 480–519). Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistic Society.

Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a cognitive semantics (Vol. 2). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tsimpli, I. M. and Sorace, A. (2006). Differentiating interfaces: L2 performance in syntax-semantics and syntax-discourse phenomena. In D. Bamman, T. Magnitskaia, and C. Zaller (Eds.), Proceedings of the 30th annual Boston University Conference on Language Development 30 (pp. 653–664). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Unsworth, S. (2005). Child L2, adult L2, child L1: Differences and similarities. A study on the acquisition of direct object scrambling in Dutch. PhD dissertation. Utrecht University. Published by LOT, Trans 10, 3512 JK Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Valenzuela, E. (2006). L2 end state grammars and incomplete acquisition of Spanish CLLD constructions. In R. Slabakova, S. Montrul, and P. Prévost (Eds.), Inquiries in linguistic development (pp. 283–304). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Van Valin, R. (2005). Exploring the syntax-semantics interface. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

VanPatten, B. (1996). Input processing and grammar instruction: Theory and research. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

VanPatten, B. (2007). Input processing in adult second language acquisition. In B. VanPatten and J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition (pp. 115–135). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

White, L. (1987). Markedness and second language acquisition: The question of transfer. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 9, 261–286.

White, L. (1991). Adverb placement in second language acquisition: Some effects of positive and negative evidence in the classroom. Second Language Research, 7, 133–161.

White, L., Bruhn-Garavito, J., Kawasaki, T., Pater, J., and Prévost, P. (1997). The researcher gave the subject a test about himself: Problems of ambiguity and preference in the investigation of reflexive binding. Language Learning, 47, 145–172.

White, L., Brown, C., Bruhn de Graravito, J., Chen, D., Hirakawa, M. and Montrul, S. (1999). Psych verbs in second language acquisition. In G. Martohardjono and E. Klein (Eds.), The development of second language grammars: A generative approach (pp. 173–199). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Whong-Barr, M. and Schwartz, B. (2002). Morphological and syntactic transfer in child L2 acquisition of the English dative alternation. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24, 579–616.