For Muslims, Islam has been from the beginning much more than what is usually meant by the Western concept ‘religion’. Islam, meaning in Arabic ‘submission (to God)’, is at the same time a religious tradition, a civilization and, as Muslims are fond of saying, a ‘total way of life’. Islam proclaims a religious faith and sets forth certain rituals, but it also prescribes patterns of order for society in such matters as family life, civil and criminal law, business, etiquette, food, dress and even personal hygiene. Traditional Muslims view virtually all aspects of individual and group life as being regulated or guided by Islam, which is seen as a complete, complex religious and social system in which individuals, societies and governments should all reflect the will of God. The Western distinction between the sacred and the secular is thus foreign to traditional Islam, although some Muslim intellectuals now call for more attention to the sacred as a response to the world-wide spread of secularism.

Since Islam is such a rich religious and cultural tradition that has varied dramatically across time and place, the sources and methods for understanding it vary equally in breadth. Until recent decades the study and portrayal of Islam involved mainly the tasks of editing, translating and interpreting written sources. This emphasis on the analysis of written texts meant that historical and philological methods dominated the field of Islamic studies. During the last quarter of the twentieth century the methods of the social sciences, especially anthropology and sociology, have vastly enriched our understanding of Muslim societies, elevating our awareness of the importance of aspects of the Islamic tradition that previously had been largely neglected [e.g. 5; 7; 12; 19]. The history and functions of rituals in the daily lives of Muslims, the various roles of the mosque (social and political as well as religious), and the relationship of Islam to politics, national and international law, and the modern state are just a few examples. Continued sensitivity to the obvious fact that Islam is both a personal religious faith and a cumulative historical tradition (stressed for decades by Wilfred Cantwell Smith, beginning with his Meaning and End of Religion) has had several positive effects. One is that scholars are devoting more attention to the study of Muslim faith and piety – the essence of Islam, but in some ways the most difficult aspect of its study for outside observers. Another is that the search for knowledge of varieties of Muslim piety has increased our awareness of the importance of a number of fields that in the past had been neglected by Islamicists or treated as independent disciplines. Examples such as Islamic art and architecture [17], the many uses of Qur’an calligraphy, the rich tradition of Qur’an recitation, Islamic poetry, various ritual and literary expressions of devotion to the Prophet [42], and popular sermons – many of which are now widely available in printed and electronic forms – provide windows of insight into Muslim piety for those who know how to look and what questions to ask.

Primary written sources for the study of Islam are also vast in number and scope. In addition to writings on Islamic history, scripture, and theology, where students in religious studies would naturally seek knowledge about this tradition, an immense literature exists on a number of distinctively ‘Islamic sciences’, such as the study of the Sunna of the Prophet contained in hadiths (reports of his sayings and deeds); Islamic law (which governs virtually all aspects of Muslim life); the ‘sciences of the Qur’an’, including ways of reciting (tajwid); Arabic grammar (as it pertains to the sacred texts); biography (especially regarding authorities for hadiths and Islamic law); and the twin sciences of geography and astronomy (important in a practical way for determining the direction of Mecca for prayer and for the orientation of mosques). Until modern times the vast majority of major Islamic works were written in Arabic, regardless of the native tongue or ethnic background of the writer. Only a small percentage of the most important classical sources, although fortunately a growing number in recent years, have been translated into other languages. Thus, those who want to study Islam in depth must learn this so-called ‘language of the angels’. Persian, Turkish and Urdu gradually became important vehicles for conveying Islamic ideas, and their significance continues to grow. In modern times, with the widespread use of printing and the vast increase in literacy throughout the world, works essential to understanding the diversity of Islam came to be written in countless languages of Asia, Africa and Europe, so that knowledge of Arabic, while still necessary, is no longer sufficient, emphasizing the need for collaborative studies among scholars with a variety of language and disciplinary specialties.

Among the many works in classical Arabic the one that all consider to be the ‘first source’ for Islamic belief and practice is the Muslims’ scripture, the Qur’an (Arabic, al-qur’an, ‘the recitation’). It is divided into 114 independent units of widely varying length called suras (from the Arabic sura, ‘unit’). Each sura begins with, or is preceded by, the formula, ‘In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate’, often followed by a longer liturgical or formulaic statement. The suras thus stand as independent units – although varying considerably in form and content – unlike the chapters of the Bible. After the first sura, al-Fatiha (the Opening), a seven-verse prayer that serves as an introduction to the Qur’an (see p. 185 below), the suras are arranged generally in order of descending length, with many exceptions and with other criteria for keeping certain groups of suras together [54: 410]. Islamic orthodoxy and modern critical scholarship agree that the contents but not the final arrangement of the Qur’an go back to Muhammad. It is also virtually certain that Muhammad began but did not complete the task of compiling a written text of the Qur’an [54: 402–4]. About twenty years after his death an official recension of the consonantal text was issued by the third caliph, ‘Uthman, establishing the number, order and contents of the suras. At that time Arabic was mainly an oral language; written Arabic was largely an aid to memory, with no uniform system of vowel signs or diacritical marks (one, two or three dots written above or below consonantal forms) for distinguishing several sets of consonants that share the same form. A system of seven canonical ‘readings’ or vocalizations (that is, systems for adding vowels and diacritical marks) of ‘Uthman’s text was established in the tenth century, and gradually one of these came to be used in nearly all parts of the Islamic world. In 1923 or 1924 (1342 AH – see pp. 182, 232–4), a standard edition of the printed text, complete with signs for recitation (indicating pauses, elision, etc.), was issued in Cairo under the authority of the king of Egypt, Fu’ad I. This edition – variously designated ‘the royal Egyptian edition’, ‘the Egyptian standard edition’, etc. – has gained widespread acceptance by Muslims and Islamicists alike, although other texts and verse numbering systems are still used. No critical edition of the Qur’an exists, nor do standard translations of the Arabic text in the various ‘Islamic’ and European languages. Among the many English translations, those by Yusuf Ali (1934) and M. M. Pickthall (1930, 1976) are preferred by most English-speaking Muslims (neither follows the Egyptian standard verse-numbering precisely, except for the latter’s 1976 Arabic – English edition). The most popular English translation by a non-Muslim is that of the Cambridge Arabist, A. J. Arberry (1955). The two-volume translation by Richard Bell (1937, 1939) is the most useful for purposes of analysis of the history of the Arabic text of the Qur’an, an issue in which very few scholars have shown any interest since the middle of the twentieth century. These latter two translations follow an inferior nineteenth-century European Arabic text and verse-numbering system; because it is so widely used, in this chapter the verse numbers according to that system are given after the Egyptian verse numbers, separated by a virgule (see [53: 410–11] on the confusing issue of Qur’an verse divisions and the various numbering systems).

Next to the Qur’an stand the multi-volume collections of accounts called hadiths (from the Arabic hadith, ‘story, tradition’) that report or allege to report sayings and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad. The hadiths provide an authoritative guide for most aspects of Muslim daily life, for which Muhammad stands as exemplar par excellence. Six canonical collections of hadiths were compiled in the ninth and early tenth centuries (the third century AH), and other early collections such as Ahmad b. Hanbal’s Musnad also gained widespread respect. Among these the most highly regarded are the two called al-Sahih, ‘the sound (hadiths)’, compiled by al-Bukhari (d. 870) and Muslim (d. 875), both available in English translation [8; 37]. At least one of the other six, the Sunan by Abu Dawud (d. 889), as well as a later, popular compendium, the Mishkat al-Masabih, are also available in English [2; 43]. The traditional Muslim view is that at least the ‘sound’ hadiths compiled by al-Bukhari and Muslim are authentic statements going back to Muhammad’s contemporaries, and that genuine Islamic life and thought must be based on the Qur’an and these hadiths. Modern scholarship is divided on the question of the extent of the authenticity of the hadiths. It is clear that many of them, including some in the collections by al-Bukhari and Muslim, grew out of legal and theological debates that occurred long after the time of Muhammad, and that others reflect later stages in the development of Islamic rituals and other practices. Regardless of the question of their authenticity as precedents for Islamic law and as historical sources for the time of Muhammad, these collections are undoubtedly extremely valuable as primary sources for classical Islam. The focus of the debate among historians concerns the extent to which these accounts represent the Islam of the third rather than the first century of the Islamic era. Some Muslim reformers have rejected the hadith reports as representing a stage in the history of Islam generations after the time of Muhammad, while others reject them simply as representing an Islam of long ago that is no longer relevant and should not be normative for Muslims today. Those who hold these modernist views are, however, a small minority of the world population of Muslims.

In addition to the Qur’an, the hadith collections, and the vast literature on both of these (commentaries, dictionaries, etc.), primary written sources for the study of Islam include historical works on the development of Islam and its spread to various parts of the world, legal and theological treatises, biographical and devotional works on Muhammad, Islamic poetry and other religious literature, and a wide variety of devotional and pilgrimage manuals, as well as mystical, philosophical and sectarian works. Fortunately, more and more of these works are being translated into English and other European languages. Examples of classical Arabic sources that are fundamental to the study of Islam and are now available in English (in addition to the Qur’an and the hadith collections mentioned above) include Ibn Ishaq’s Sirat Rasul Allah (Life of the Messenger of God) [20]; al-Tabari’s Ta’rikh al-rusul wa-l-muluk (History of the messengers [of God] and the rulers) [46]; Ibn Sa‘d’s Kitab al-tabaqat al-kabir (Large book of the generations) [25]; and Malik ibn Anas’s Muwatta [32] on Islamic law. Much of al-Ghazali’s magisterial Ihya’ ‘ulum al-din (Revival of the religious sciences) has been translated in individual volumes by various scholars. Several very useful anthologies of English translations of a wide variety of classical and modern Arabic source materials are also available (see [5; 41; 56]; and, for selections from Qur’an commentaries, [4; 18]).

Islam dates from the last ten years of the life of the Prophet Muhammad (d. 632). Born probably around 570, Muhammad was orphaned at an early age and is said to have been reared by his grandfather and then an uncle, Abu Talib. At about the age of twenty-five Muhammad gained financial security when he married Khadija, a well-to-do widow. At about the age of forty he is said to have begun seeing visions, or according to other accounts receiving revelations, which at some point he proclaimed publicly in the streets of Mecca, his native city and also the centre for commerce and religious pilgrimage for western Arabia. Fearing the economic repercussions of Muhammad’s preaching against the deities worshipped by the pilgrims at Mecca’s central shrine, the Ka‘ba, the leading families of the city persecuted Muhammad and his followers, forcing many who did not have tribal or clan protection (usually said to have been a large majority of the Muslims at that time) to migrate to the Christian kingdom of Abyssinia, also called Ethiopia, across the Red Sea. The Meccan plutocrats are said to have imposed a social and economic boycott against Muhammad’s clan of Hashim, causing dissension within the clan. This resulted in the loss of Muhammad’s clan protection when his uncle and guardian Abu Talib died in about 620 and an enemy uncle, nicknamed Abu Lahab (Father of the Blaze) and immortalized in Sura 111 where he is condemned to the hellfire, became the clan chief and then withdrew his nephew’s protection. Muhammad’s life was no longer safe in Mecca, so he was forced to seek refuge elsewhere. After failing to find a new home for himself and his followers in nearby al-Ta’if, he reached an agreement with representatives of Yathrib, an agricultural settlement some 445 km north of Mecca, and in 622 he and his followers made the hijra (migration) to this settlement, which came to be called Medina, from madinat al-nabi, ‘the city of the Prophet’. There within the short period of ten years Muhammad, the religious leader of a small band of emigrants, rose to become the political leader of virtually all of central and western Arabia. A Muslim military defeat of a much larger force of Meccans and their confederates at a caravan watering site called Badr in 624 became a major turning-point in Muhammad’s rise to power. This awe-inspiring victory over the polytheists at Badr, along with several failed attempts by the Meccans and their allies to stop Muhammad by military force, eventually followed by what turned out to be an equally impressive diplomatic feat in the signing of the Treaty of al-Hudaybiya in 628, led to the peaceful surrender of Mecca to Muhammad in 630.

After Muhammad’s death in 632 the political and spiritual leadership of the Muslim community (called the Umma in Arabic) was assumed by a succession of caliphs or ‘deputies’ of the Prophet, who ruled Islam in his place in all aspects except as prophet. By the end of the reign of the second caliph, ‘Umar (d. 644), the Arabs had taken control of Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia and the heart of ancient Iran, capturing Damascus in 635, Jerusalem in 640, what was to become Cairo in 641, Alexandria in 642 and Isfahan in 643. During the reign of the third caliph, ‘Uthman (d. 656), the Arab empire expanded westwards to Tripoli, northwards to the Taurus and Caucasus mountains, and eastwards to what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan. After the death of the fourth caliph, ‘Ali (d. 661), Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, the Muslim community split, with the majority, who later came to be called Sunnis, following the Umayyad dynasty of caliphs (661–750) and then the ‘Abbasid dynasty (750–1258). In 711, about a century after Muhammad began preaching in Mecca and mid-way through the Umayyad period, the Arabs entered Spain from North Africa and also crossed the Indus river into the subcontinent of India. The Arabs’ furthest point of advance into western Europe is marked by their defeat at the hands of Charles Martel near Tours in 732, exactly a solar century after the Prophet’s death and ten years before the birth of Charlemagne. The Arabs were forced to withdraw from France, but they and their Muslim Berber successors continued to rule in Spain for seven and a half centuries. In the east the Arab-ruled Umayyad empire spread northwards to the Aral Sea and across the Oxus river (now called the Amu-Dar’ya) to Tashkent, and eastwards to include almost the whole of what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan. During the caliphate of the ‘Abbasids with their capital in Baghdad, the extent of the ‘Islamic territories’ in the west remained the same as under the Umayyads, while in the east Muslims gained control of northern India and the area down to the Bay of Bengal. But this vast region, from the Pyrenees to what is now Bangladesh, was soon divided into a number of independent territories, ruled for centuries by successions of Islamic dynasties, and ‘Abbasid rule was eventually reduced to just part of what is now Iraq [6].

While most areas that came under Muslim control remained so, this was not the case in Europe and the subcontinent of India. In Muslim Spain the Spanish Umayyads ruled from 756 to 1031, and then several Islamic dynasties, including the Almoravids and Almohads from North Africa, ruled an ever-shrinking Muslim Spain during the period of the Christian Reconquista that culminated in the fall of Granada in 1492, when most of the remaining Muslims (and also the Jews) were forced to leave Spain. The Ottoman Turks, whose leaders, called sultans, assumed the title of caliph, crossed into eastern Europe from Anatolia in the fourteenth century and rapidly took over most of the Balkan peninsula. During the next two centuries their empire gradually encircled the Black Sea and spread north-west almost to Vienna and north-east almost to Kiev, while to the south the Ottomans gained control of Egypt, North Africa and the Fertile Crescent. During the nineteenth century the Ottomans lost most of their holdings in Europe and across northern Africa, and by the beginning of the First World War Turkey in Europe was reduced to the small area called Eastern Thrace that surrounds Istanbul. When the last Ottoman sultan, Muhammad VI, was deposed by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the title of caliph went briefly to a cousin and then in 1924 the caliphate was abolished altogether. The Muslim Mughals by the end of the seventeenth century controlled virtually all of the subcontinent of India, in addition to what are now Pakistan, Afghanistan, Kashmir and Bangladesh. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, however, they gradually lost control of the outlying areas and eventually also of northern India. The last Mughal emperor was deposed by the British in 1858. So the Arabs and the Berbers were forced out of western Europe and the Turks out of virtually all of eastern Europe, while the Mughals lost control of India; but not before these groups had left a permanent Islamic imprint on these regions.

A distinction must be made between the rapid political and military expansion of empires ruled by Arabs and other Muslims and the spread of Islam or religious conversion, which proceeded at a much slower pace. Those areas where the rulers and the majority of the people became Muslims came to be called Dar al-Islam, the House of Islam (sometimes translated as ‘the House of Peace’, partly because of the root meaning of the term islam, which yields also the word salam, ‘peace’). Gradually, over a period of centuries, the overwhelming majority of the people living under Muslim rule in northern Africa, the Fertile Crescent and Anatolia, who had previously espoused various forms of Christianity, converted to Islam. In contrast, all but a small percentage of the people of Iran, who had previously followed the state-sponsored Zoroastrian faith, adopted Islam, the religion of their new rulers, within just a few generations. At the opposite extreme, the Jewish people, many of whom lived under Muslim rule for many centuries, with very few exceptions remained faithful to their tradition. Since the time of the ‘Abbasids, Islam has continued to spread, mostly by peaceful, missionary means, eastwards through Asia to parts of China and South-East Asia – notably Malaysia and Indonesia, where a large majority are now Muslim – and also across a wide area of Saharan Africa and sub-Saharan East and West Africa. Only on rare occasions in some parts of Africa and Asia, far fewer than in the case of Christianity, has Islam spread in accordance with the popular misconception ‘by the sword’, going against the clear teaching of the Qur’an that ‘There shall be no compulsion in religion.’

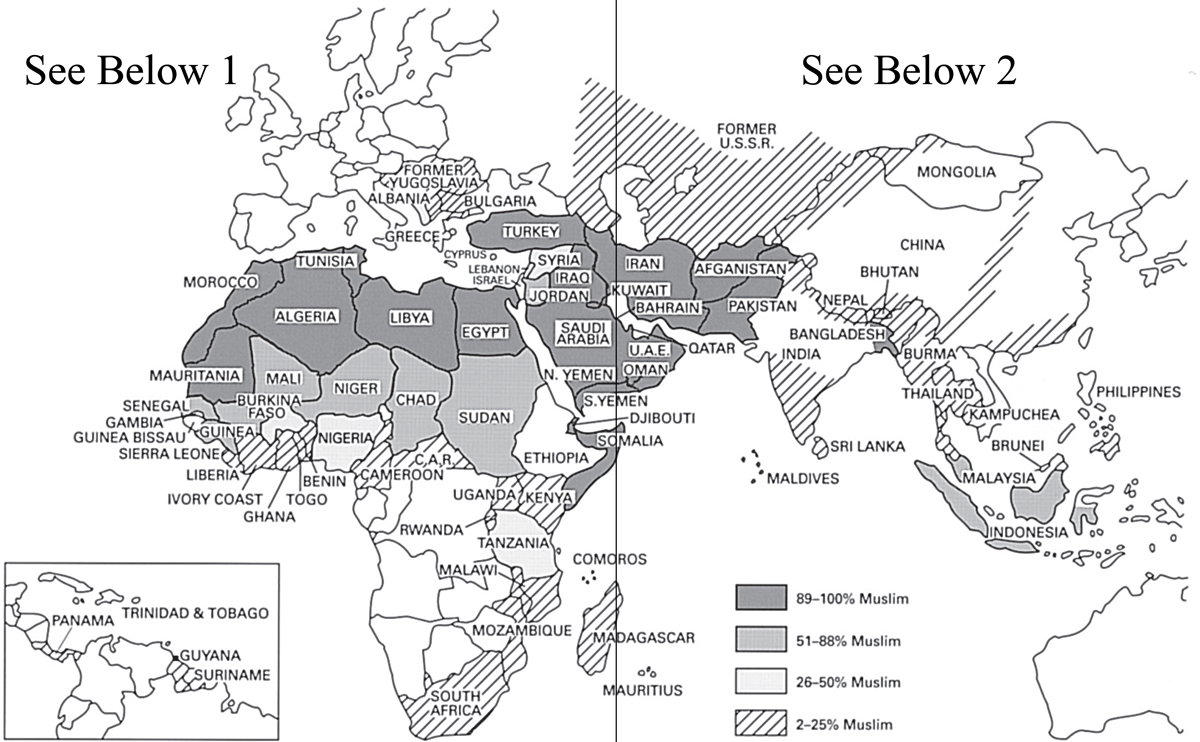

Perhaps the most persuasive evidence of the vitality of Islam today is that it continues to be a missionary force in various parts of Asia, Africa, Europe and North America. Remarkable successes can be seen, especially in sub-Saharan West and East Africa, where Islam has the advantage of not being identified with white, European colonialists. Even more perplexing to Christians is the fact that Islam is the fastest-growing religious community in Europe and North America, with many Caucasian converts. Today, Muslims are represented in all the major races and cultures; but the vast majority live in a nearly contiguous band around the globe from the Atlantic shores of North and West Africa eastward to Indonesia in the Pacific. The largest broad ethnic community of Muslims is that of South Asia (the Indian subcontinent, where the vast majority live in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh), numbering in 1990 over 300 million or almost 30 per cent of the Muslim world population. In 1990 almost 200 million Muslims lived in South-West Asia (the Middle East, not including Egypt), 250 million in the rest of Asia (with about 175 million of these in South-East Asia and Indonesia), 145 million in northern and Saharan Africa (most of whom are native Arabic-speakers), over 100 million in the rest of Africa, and nearly 20 million in Europe (excluding Istanbul and the rest of Turkey that lies in the Balkan peninsula) and North America. The United States of America now has the largest number of Muslims of any country in the West (that is, Europe and the Western Hemisphere). Altogether the world Muslim population in 1990 was over 1 billion, with the population centre being somewhere in northern India – possibly near the famous Taj Mahal in Agra or the grand Jami‘ Masjid (congregational mosque) in Delhi, both built in the time of the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan (see figure 3.3 below). Shi‘i Muslims (see pp. 208–9) make up about one-tenth of the world Muslim community, with their largest populations in Iran and Iraq, but with significant and long-established minorities in other countries, such as Lebanon, Kuwait and parts of India. For approximate 1990 Muslim population statistics and percentages and very general estimates for the year 2000, listed by country and arranged by geographical region, see appendix B (p. 229).

The expressions ‘the Middle East’, ‘the Arab world’ and ‘the Muslim world’ are often not precisely defined and, in any case, are frequently confused. The Middle East is usually taken to include the area from Egypt and Turkey to the western border of Pakistan (usually considered part of South Asia). Using this definition, about 240 million Muslims or less than 25 per cent of the world Muslim population lived in the Middle East in 1990. Of these, about 130 million lived in non-Arabic-speaking countries (Iran, Turkey and Afghanistan). The Arabic-speaking countries of South-West Asia and northern and Saharan Africa had about 190 million Muslims, or less than 20 per cent of the Muslim world population. These figures show that the popular identification of ‘the Middle East’ with ‘the Muslim world’, and of Arabs with Muslims, is far from correct. The country with the largest Muslim population is Indonesia, in East Asia. The country with the largest Arabic-speaking population is Egypt, in north-eastern Africa. (Egypt happens also to be the geographic and demographic centre of the Arab world, with about 35 per cent of all native Arabic-speakers living east of Egypt in South-West Asia, and 40 per cent living west and south of Egypt in Africa – indicating that about 65 per cent of native Arabic-speakers live on the continent of Africa.) It is also important to remember that millions of Arabs, that is, native Arabic-speakers, are Christians and some are Jews. Most of these live in the Middle East, thus disproving both of the false equations mentioned above.

Figure 3.1 The peoples of Islam

Source: J. L. Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path, New York/Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1995.

The primary Islamic beliefs and world-view are presented in the Qur’an. Numerous passages, dating from the years in Medina when Muhammad was forming a monotheistic community that was to be separate from the Christians and the Jews, require certain beliefs and practices. Several of what appear to be the earliest of these Qur’anic creedal and prescriptive passages require both some beliefs and some practices, the most common being belief in (One) God and the Last Day and the duties of worship and almsgiving. One of the most succinct statements of essential Islamic beliefs occurs in Sura 4. 136/135:

O believers, believe in God and His Messenger and the Book He has sent down on His Messenger and the Book He sent down before. Whoever disbelieves in God, His angels, His Books, His Messengers, and the Last Day has surely gone astray, far into error.

The Qur’an has much to say about each of these fundamental beliefs, but presents no systematic or extended explanations of any one doctrine. Also, apparent contradictions occur within the whole of what the Qur’an has to say on any one basic belief. Since it is customary for Muslims to deny the presence of the development of ideas in the sacred text, any apparent inconsistency must be resolved in some other way. Over the centuries Qur’an commentators, jurists and other interpreters have found a variety of ways of accomplishing this, mainly by interpreting the Qur’an synchronically and arguing that certain verses abrogated earlier ones that appear to be inconsistent with the later ones. The description of the major teachings of the Qur’an and thus the basic Islamic beliefs given below follows a different approach, interpreting the Qur’an diachronically, that is, attempting to trace the development of these teachings over the course of Muhammad’s prophetic career.

Early parts of the Qur’an are striking for their lack of statements about God, other deities and the various members of the world of spirits. The earliest passages – several short, rhythmic suras that are in the style of the pre-Islamic Arabian soothsayers – contain no references to God, nor any indication that they are messages from a deity. The earliest revelations that mention Muhammad’s God refer to him only as ‘Lord’ (rabb), as in the expressions ‘your Lord’, ‘his Lord’, etc. (see the beginning of Suras 74, 87 and 96). Some time later, Muhammad’s Lord began to be called ‘the Merciful’ (al-rahman). This name seems to have been preferred for a while (see, for instance, Suras 19 and 43, and the important statements in 13. 30/29, 25. 60/61 and 55. 1ff). At about the same time, the name ‘Allah’, known to the Meccan polytheists before Muhammad’s time, was introduced into the revelation. The well-known verse, Sura 17. 110, which begins, ‘Say: Call upon Allah or call upon the Merciful; whichever you call upon, to Him belong the most beautiful names’, had the effect of replacing the dominant usage of ‘the Merciful’ with that of ‘Allah’. Later parts of the Qur’an provide the ingredients of a rich theology in their frequent use of a wide variety of divine epithets, as for instance in the following liturgical passage at the end of Sura 59:

He is God – there is no god but He.

He is the Knower of the unseen and the visible.

He is the Merciful, the Compassionate.

He is God – there is no God but He.

He is the King, the Holy, the Peaceable, the Faithful, the Preserver, the Mighty, the Compeller, the Sublime.

Glory be to God, above what they associate [with Him].

He is God – the Creator, the Maker, the Shaper.

To Him belong the most beautiful names.

All that is in the heavens and the earth magnifies Him.

He is the Mighty, the Wise.

By collecting these divine epithets in the Qur’an and forming others from verbs and other terms that refer to God, later Muslims compiled slightly varying lists of the Ninety-Nine Names of God. These appear in calligraphy, sometimes on the inside covers of copies of the Qur’an, and most strikingly in devotional use, where some Muslims memorize them and recite them using strings of thirty-three or occasionally ninety-nine prayer beads.

Theologians were often concerned to express Islamic beliefs about God in more formal, even philosophical, language, and thus developed other themes, as seen in Article 2 of the document that came to be called Fiqh Akbar II:

God the exalted is one, not in the sense of number, but in the sense that He has no partner; He begetteth not and He is not begotten and there is none like unto Him. He resembles none of the created things, nor do any created things resemble Him. He has been from eternity and will be to eternity with His names and qualities, those which belong to His essence as well as those which belong to His action. Those which belong to His essence are: life, power, knowledge, speech, hearing, sight and will. Those which belong to His action are: creating, sustaining, producing, renewing, making, and so on. [55: 188]

The doctrine that ‘God is One’ is so prominent in later parts of the Qur’an that it is easy to overlook the fact that earlier parts of the Islamic scripture do not explicitly reject the existence of other deities. The three goddesses whose worship flourished in and around Mecca in Muhammad’s time, al-Lat, al-‘Uzza and Manat, are mentioned by name in Sura 53. 19–20. In a number of passages in the Qur’an, including what appear to be a series of revisions of Sura 53, these goddesses may at first have been accepted as intercessors with God, then are designated as angels, and finally are said to be merely names invented by the Meccans’ ancestors. In other Meccan parts of the Qur’an, that is, passages dating from before the Hijra in 622, deities other than Allah are demoted to the level of jinn before they are said not to exist at all (see Suras 6.100, 34. 40–2/39–41, 37. 158–66).

The existence of the jinn, those shadowy, invisible spirits of pre-Islamic Arabia that, like man, can be either good or evil, is also assumed in Meccan parts of the Qur’an, especially in the frequently occurring expression ‘jinn and men’, which seems to present jinn as the invisible counterpart of man. The jinn also appear in the Qur’an in mythic and legendary accounts, for instance as listeners at the gate of heaven seeking knowledge of the future (Sura 72. 8–9, one of the Qur’anic versions of an ancient Near Eastern myth explaining shooting stars), as slaves of Solomon working on the Temple (27. 39, 34. 1–14/1–13) and as the army of Iblis, the fallen angel (18. 50/48). Iblis is the Qur’anic and Islamic equivalent of the Christian archangel Lucifer, who was cast from heaven for revolting against God and became Satan, the Tempter. In some contexts, such as Sura 72, jinn become believers, while in others they are presented as evil or mischievous and are sometimes equated with ‘satans’, shayatin, the plural form of Shaytan, the Arabic equivalent of the Hebrew and English word Satan. It is significant that the jinn, demons and Iblis are not mentioned in parts of the Qur’an that date from after the establishment of distinctively Islamic beliefs and practices in Medina after the Hijra. In place of these ‘lower’ spirits, later parts of the Qur’an present a more exalted view of angels as invisible, abstract symbols of God’s power, and a more abstract view of Satan as a symbol for evil and disbelief. This process of polarization of spiritual powers for good and evil in the world is similar to the manner in which the Qur’an treats deities other than God. The theologians in their treatises and creeds expand very little on what the Qur’an says about these spirits, but popular Islam elaborated a vast, complex spirit world that touches virtually all aspects of life in this world and in the hereafter.

A second complex of ideas central to Islamic faith as it arose in the Qur’an and developed in later creeds and theological treatises involves the origin, nature and destiny of man. In the Qur’an the creation and judgement of man are frequently mentioned together, often with references to the resurrection. In some contexts the idea of creation is closely related to the conception and birth of each individual, as in Sura 80. 17–22/16–22:

Woe to man! How ungrateful they are.

From what did He create them?

From a sperm-drop has He formed them.

Then He makes his path easy for them.

Then He causes them to die and buries them.

Then, when He will, He raises them.

In other passages of the Qur’an the biblical idea of the creation of the First Man from dust or clay occurs a number of times, as in the following version of the Iblis story in 15. 28ff, which begins: ‘And when your Lord said to the angels: “See, I am about to create a human being from clay, formed from moulded mud. When I have shaped him [Adam] and breathed My spirit into him, fall down all of you and bow before him.” ’ This idea of creation occurs frequently in the context of concise statements on the human life-cycle, as in 71. 17–18/16–17: ‘God caused you to grow out of the earth, then He will return you into it, and bring you forth [from it again at the Resurrection].’ Then in a number of passages these two teachings regarding God’s creation of man are combined into more elaborate accounts, such as in 23. 12–16:

We created man [Adam] from an extract of clay;

Then [later] We placed [you] as a sperm-drop into a safe receptacle;

Then We fashioned the clot into a lump; then We fashioned the lump into bones; then We clothed the bones with flesh; then We made [you] into a new creation. So blessed be God the fairest of creators!

After this you will surely die,

And on the Day of Resurrection you will surely be raised up.

As for our basic nature, whether we are ‘born in sin’ as a result of the Original Sin of Adam and Eve (essentially a Christian belief) or are intrinsically good, the glory and crown of God’s creation (a theme that occurs in the Jewish scriptures), Islam adopts what appears to be a middle view, seen in Sura 91. 7–10:

By the soul and [Him who] formed it,

And implanted into it its wickedness and its piety!

Blessed is he who purifies it.

Ruined is he who corrupts it.

Thus the potential for both good and evil is breathed into each person by God at birth. Then throughout life people are tested by their Maker, as the Qur’an says in 21. 35/36: ‘And We try you with evil and good as a test; then unto Us you will be returned.’ The Qur’an says that some people will choose good and will be rewarded, while others will choose evil and will be punished. Eternal reward and punishment are to be meted out by God at the Last Judgement, around which a central doctrine of the Qur’an and later Islamic theology developed. In the early stages of the development of Qur’anic creedal statements, the most frequently occurring requirement was that one ‘believe in God and the Last Day’. This great eschatological event, also called the Day of Judgement, the Day of Resurrection, and sometimes simply ‘the Day’, is vividly described in the Qur’an, as are the pleasures of the Garden of Paradise and the torments of the hellfire, called Jahannam (cf. the Hebrew Gehenna), the Fire, etc. (22. 19–22/20–2, 56. 11–56, 69. 13–37, 76. 11–22, etc.).

The Islamic doctrine of the hereafter, with its stress on reward and punishment, seems to require the corollary belief in individual responsibility for one’s faith and actions. But the ancient Arabian belief in Fate also appears in the Qur’an, along with a number of statements that clearly support the later Islamic doctrine of predestination. According to the ancient view, four things are decided for each individual before birth: the sex of the child; whether it will have a happy or miserable life; what food it will have; and its ‘term of life’. This idea of a predetermined life-span occurs in the Qur’an, as in 6. 2: ‘It is He who created you from clay, then determined a term, and a term is stated with Him’ (cf. 3. 145/139). Man’s predestination is said to involve everything in life, as in 9. 51: ‘Nothing will befall us but what God has written down for us …’ It was left for later theologians to correlate this teaching with other Qur’anic statements saying that each person is responsible for his or her own actions.

The earliest parts of the Qur’an do not mention revelation or God’s prophets and their scriptures. When those who later came to be called prophets are mentioned in Meccan passages they are referred to simply as ‘messengers’ (rusul; sing. rasul), ‘ambassadors’ (mursalun), etc. The context in which these messengers appear most frequently are series of so-called ‘punishment-stories’, where Noah, Lot and several others bring God’s message to their people or tribes, are ridiculed and rejected by most of their people and then rescued by God along with their families and followers, while those who rejected them perish in a flood, fire or some other natural calamity (see Suras 7. 59ff/57ff, 11. 25ff/27ff, 26. 105–91, etc.). Details of Muhammad’s experience in Mecca, such as accusations made against him by his opponents, appear frequently in stories of earlier prophets, but it is only implied that Muhammad is also such a ‘messenger’ and that his city, Mecca, is being threatened with the same type of terrestrial destruction. The Qur’an does not, during this period, explicitly describe Muhammad as a ‘messenger of God’ (rasul Allah) to be classed with the great messengers or prophets of the past.

It is only after the Hijra in 622 and after the Muslims’ victory at the battle of Badr in 624 that the role of ‘prophet’ (nabi) became prominent in the Qur’an and Muhammad came to be included explicitly among the prophets. Prophets are said to descend from Abraham, the first monotheist and thus the first ‘Muslim’ (one fully surrendered to God alone), and each is said to have been given a Book or scripture (kitab). The Torah of Moses and the Gospel of Jesus receive special attention in the Qur’an and in later Islamic belief, but the Psalms of David and the ‘scrolls of Abraham’ are mentioned briefly. The teaching of the Qur’an appears to be that every prophet brought a copy of the heavenly Book, presumably in the language of his people. In Medinan parts of the Qur’an, that is, passages that date from after the Hijra in 622, Muhammad is frequently called ‘the Prophet’ or ‘the Messenger of God’, two expressions that came to be used synonymously in later revelations (see for instance their usage in Sura 33). Just what the expression ‘Seal of the Prophets’ (khatam al-nabiyyin), applied to Muhammad in 33. 40, meant to him and his followers is difficult to say. Most likely it meant that the revelations recited by Muhammad confirmed or put a seal of divine approval on certain teachings that were attributed to earlier prophets, such as Moses and Jesus, while declaring that other Jewish and Christian teachings did not come from these prophets but were invented later and surreptitiously inserted into the Torah and the Gospel. The Qur’an mentions certain later Jewish food laws and the Christian belief that Jesus is the Son of God as examples of teachings that do not derive from Moses and Jesus. Later Muslims came to interpret the expression ‘Seal of the Prophets’ in 33. 40 to mean that Muhammad was the ‘last of the prophets’, and some, against the teachings of orthodox theology, interpret it to mean ‘the last and greatest of the prophets’. According to the teachings of the Qur’an and later Islamic theology, all prophets are equal. Many passages throughout the Qur’an stress Muhammad’s complete humanity, his lack of supernatural knowledge or powers such as the ability to see the Unseen (al-ghayb), to foretell future events or the end of time, or to perform miracles. After his death Muhammad rapidly came to be elevated in popular belief. Many miracles are attributed to him and he is widely venerated and called upon for intercession with God. (On these later developments, see [43; 26: 309–36, 530–6].)

Five fundamental rituals, called the Pillars of Islam, are regarded as essential public signs of a Muslim’s submission to God (islam) and identity with the Muslim community (umma): (1) public profession of faith by recitation of the doctrinal formula called the shahada; (2) daily performance of a prayer ritual called the salat; (3) annual giving of obligatory alms called zakat; (4) fasting (sawm) during the month of Ramadan; and (5) performance of the rituals of the Great Pilgrimage, called the Hajj, in and near Mecca once in one’s lifetime if health and wealth are sufficient. The last four of these are specifically prescribed in the Qur’an, but none is described there fully. The Pillars of Islam and other rituals eventually came to be regulated in detail by Islamic law (fiqh). Thus a brief introduction to fiqh is necessary for understanding the basic religious practices of Muslims.

The person most responsible for establishing the theory and structure of classical Islamic law for the majority of Muslims (the Sunnis) was Muhammad ibn-Idris al-Shafi‘i (d. 819). His main contribution was in developing a system of four Sources of Islamic law (usul fiqh) that eventually came to be accepted by most Sunnis: (1) the Qur’an; (2) the Sunna (custom) of the Prophet as reported in the hadiths; (3) consensus (ijma’) of the classical jurists; and (4) ‘systematic original thinking’ (ijtihad) of the founders of the legal schools or rites (madhahib) described briefly below. Both the third and fourth Sources must involve ‘reasoning by analogy’ (qiyas) based on statements in the Qur’an and the hadiths. By the time of al-Shafi‘i the prominent jurists had already reached ‘consensus’ on many issues on which the Qur’an and the hadiths do not provide definitive answers to legal questions. Thus ijma‘ was well along in the process of being established as the third Source, independent of the need for emphasis on analogical reasoning (qiyas). For this reason some classical and modern writings list qiyas as the fourth Source or even equate it with ijtihad. (For an excellent summary of the early history of these technical terms see [39: 68–79].) The basic theory behind Islamic law and correct performance of the required rituals is that Muslims should first ask: What does God prescribe in the Qur’an? On practices about which the Qur’an is silent or ambiguous, they then ask: What did the Prophet Muhammad do or say? In most cases where the hadiths report conflicting views, the prominent jurists of the third century AH (ninth century CE), motivated by a strong desire for uniformity of Islamic practice, reached consensus (ijma‘). Where they could not, mainly regarding details of law and the precise way rituals were to be performed, they agreed to disagree, thus establishing a system of multi-orthopraxis. The Pillars of Islam, for instance, must be performed precisely according to Islamic law, but Muslims have a choice as to which legal rite (madh-hab) they follow. Once orthopraxis was established, the classical jurists declared that the ‘gate of independent reasoning’ (bab al-ijtihad), which allowed for differences among the schools and for new regulations, was closed. Thereafter, any new practice or any variation in an established one was termed an ‘innovation’ (bid‘a), which came to mean heresy. (See pp. 211 ff for the significance of these terms in modern debates within the Muslim community.)

Al-Shafi’i did not succeed in establishing a universal Sunni legal school or rite, partly because of the prestige of Abu Hanifa (d. 769), the champion of logical thought in Islamic law, and Malik ibn Anas (d. 795), author of the first major compendium of Islamic law, the Muwatta. Eventually, four Sunni legal schools or rites (madhahib; sing. madhhab) became firmly established: the Shafi‘is (dominant today in lower Egypt, Syria, southern India, Indonesia and Malaysia); the Hanafis (who flourished within the Ottoman empire and are dominant today in Turkey, northern India, Pakistan, Central Asia and China; the Malikis (dominant in Saharan Africa, upper Egypt and the countries of North Africa, i.e. Morocco to Libya); and the Hanbalis, named after Ahmad ibn Hanbal (d. 855), the smallest school today (dominant mainly in Saudi Arabia). The Malikis rely more on the Sunna of the Prophet, especially ‘the living tradition’ in Medina at the time of the founder of this school. The Hanafis place more emphasis on creating precedents by analogy (qiyas), often resulting in more lenient regulations and penalties. The Hanbalis are the most strict, tending towards puritanical characteristics. The major Shi‘i legal school is sometimes called Imami, sometimes Ja‘fari, after the Sixth Imam, Ja‘far al-Sadiq (p. 208 below). (See [39: 81–4] on the origins of the Sunni schools and p. 211 below on the influence of the Hanbalis today.)

The dates for observance of the annual practices, notably the fast during the month of Ramadan and the pilgrimage during the month of Dhu-1-Hijja, are determined by a purely lunar Islamic calendar, which was established by Muhammad during the last year of his life. Some knowledge of the Islamic calendar is thus necessary for understanding the annual rituals in particular. A lunar year of twelve revolutions of the moon around the earth lasts about 354 days, or eleven days less than a solar year. Thus the beginning of the Islamic year, and each of the annual festivals, moves back through the solar calendar one season approximately every eight years or through the entire solar year (and the four seasons) once in about thirty-two and a half years. Probably within a decade of Muhammad’s death – the decision is usually said to have been made during the caliphate of ‘Umar (634–44) – the year of the Hijra, 622 (see p. 169 above), was chosen as the year 1 of the Islamic era, often designated AH from the Latin anno Hegirae. Contrary to popular belief, and to statements in many writings on Islam, the first day of the first month of the Islamic calendar does not correspond with the date of Muhammad’s emigration from Mecca to Medina, nor with the fictional concept of a mass emigration of all the Meccan Muslims. After Muhammad’s final agreement with representatives from Yathrib (later called Medina), his followers began a gradual, intermittent move from Mecca and from Abyssinia throughout the spring and summer of 622, while he is said to have remained in his native city until late summer and did not arrive in Medina until September. The Islamic calendar was set to begin on the day when Muharram (the first Islamic month) was calculated to have begun during the year of the Hijra, usually believed to coincide with 16 July 622. (On the Islamic calendar, and its relation to the Christian calendars, see appendices C and D below, pp. 231–4.)

The beginning and essence of being a devout Muslim is to recite with sincere ‘intention’ (niyya) the simple Islamic creed called the Shahada (confession), consisting of two statements: ‘There is no god but God’ and ‘Muhammad is the Messenger of God’. Both occur in the Qur’an, but not together. This formula is pronounced by new converts as part of the ceremony of becoming a Muslim, and it is recited in each performance of the Salat (see below). The term in the Shahada translated above as ‘God’ is Allah, the Arabic proper name for God used by Christians as well as Muslims. This name probably comes from al-ilah, ‘the god’, the common Arabic noun for a deity, with the definite article. Since Christians, Jews and others agree with Muslims on the first statement of the Shahada, it is the second that distinguishes Muslims. Implying much more than casual assent that Muhammad is ‘a prophet’, it carries with it the conviction that Muhammad is at least the last, if not the greatest, of the prophets. His role in Islamic practice is pivotal since in theory he was the ideal Muslim and the exemplar of all proper religious life and ritual. As mentioned above (pp. 178–9), the expressions ‘the Messenger of God’ and ‘the Prophet’ occur in later parts of the Qur’an as synonymous titles for Muhammad. In later Islamic thought a distinction was made between the expressions ‘messengers’ (rusul) and ‘prophets’ (nabiyyun), which came to designate two categories of men, one being a smaller, elite group within the other. The theologians disagreed, however, as to which title designated which group.

The earliest Islamic practice to arise was the daily prayer ritual called the Salat. Passages of the Qur’an that appear to date from before Hijra in 622 explicitly require only Muhammad to perform this ritual, and God commands him to perform it twice each day, ‘in the morning and the evening’, or, according to Sura 11: 114/116, ‘at the two ends of the day’. This command, always addressed to Muhammad in the second person singular, is worded a variety of ways in Suras 17. 78/80, 20. 130, 40. 55/57, 50. 39/38, 52. 48–9, and in several other suras. Then in Medinan portions of the Qur’an, as rituals for the new religious community were being established, all Muslims are commanded to perform the Salat, and a third daily ritual, called simply ‘the middle Salat’ is mentioned in Sura 2. 238–9/239–10. Most modern historians are convinced that this third ritual was performed at midday and thus is equivalent to the present so-called noon Salat. Within a century of the Prophet’s death the number of required daily Salats was increased to five. They are usually called ‘morning’ (fajr), ‘noon’ (zuhr), ‘afternoon’ (‘asr), ‘sunset’ (maghrib), and ‘evening’ (‘isha’), names that are somewhat misleading since they sometimes indicate the beginning of the prayer time or a specific time of the day after which the prayer ritual can be performed. That is, the morning Salat is performed from the time it is light until the sun begins to appear on the horizon; the noon Salat, from after the sun has reached its zenith until it is half-way down; the afternoon Salat, from that point until the sun starts to set; the sunset Salat, after the sun has fully set until it is dark; and the evening Salat, after it is dark. Eventually a number of hadiths arose claiming that Muhammad’s followers performed the Salat five times daily during his lifetime [see 8: VIII; 37: IV], but these are contradicted by others that appear to reflect the historical development more accurately. The three daily Salats that are clearly mentioned in the Qur’an are not easily identified with the later five, partly because they did not yet have established or formal names. The expressions salat al-fajr and salat al-‘isha’ occur in Sura 24. 58, a fairly late Medinan verse. The context suggests that these are the Salats ‘at the two ends of the day’ mentioned frequently in the Qur’an, making the latter coincide with what later came to be called the maghrib, the fourth rather than the fifth daily Salat. The interpretation is further complicated by hadiths that say Muhammad sometimes led the congregational evening Salat while it was still light, keeping the men in the mosque until the women had time to return to their homes before dark, but that at other times he waited until after dark ‘after the women and children had gone to bed’ to call the men to the mosque for this Salat. These observations on the origins of the Salat are relevant to various arguments by modern Muslims calling for reforms or a return to the way rituals were performed during Muhammad’s lifetime (see pp. 211–12, 213–14 below).

To what extent the present complex ritual described below had developed during Muhammad’s lifetime is difficult to determine. Some essential parts of the present Salat are mentioned in the Qur’an, for instance, the bowing (ruku‘) in 2. 125/119, 22. 26/27, 48. 29, etc., and the prostration (sujud) in 2. 125/119, 4. 102/103, 25. 64/65, etc. Also, specific instructions for performing ablutions before prayer are given in 5. 6/8–9. For the first year or so after the Hijra the Muslims in Medina faced north towards Jerusalem while performing their daily prayer ritual, as was the Jewish practice. Then, at the time of the so-called ‘break with the Jews’ [52: 93–9], the qibla or ‘direction worshippers face during the prayer ritual’ was changed from Jerusalem to Mecca (see Sura 2. 142–50/136–45), as part of a larger process of developing Islam into an independent religious tradition, with indigenous Arabian features in some of its fundamental rituals [52: 98–9, 112–14]. The Meccan qibla has been an obligatory feature of the Salat ever since, whether performed in mosques, in homes or other buildings, or out in the open. This requirement in the performance of the Salat led to a unique feature of mosque architecture, a niche in the wall that indicates the direction of Mecca (see p. 189 and the mosque drawings in figure 3.3).

The beginning of the period for performing each of the five prescribed daily Salats and the time to go to the mosque on Fridays are announced by a public ‘call to prayer’ (adhan), given by the muezzin (mu’adhdhin). The call to prayer consists of seven short statements:

God is most great.

I testify that there is no god but God.

I testify that Muhammad is the Messenger of God.

Come to prayer.

Come to salvation.

God is most great.

There is no god but God.

The first statement is chanted four times, the last only once, and all the others twice. In the call to the morning prayer the statement ‘Prayer is better than sleep’ is inserted after the fifth statement, or, in one of the legal rites, at the end. The Shi‘is (see pp. 208–10) insert ‘Come to the best work’ after the fifth statement, and they recite the final statement twice. The worshipper must be in a state of ritual purity, accomplished by performing either the minor ablution called wudu’, for minor impurities, or the major one called ghusl, for major impurities. Some of the legal schools have ruled that one ablution ceremony in the morning serves for all five prayers of that day unless it has been invalidated by some impurity.

Proper observance of the Salat is a required duty of all Muslims, and its essential elements are prescribed by Islamic law and customary practice. The exact performance of the Salat varies among the various legal rites described briefly above, but a general uniformity of practice exists regarding thirteen essentials (arkan) – six utterances or recitations, six actions or positions, and the requirement that these twelve must proceed in the prescribed order. The description given below is based largely on the practice of the Shafi‘is, the classic definition of which is given in the Ihya’ of the great theologian al-Ghazali (see pp. 168, 207). The system used below for numbering the utterances and giving letters for the positions (see figure 3.2) makes the description of the essentials valid, however, for all the major legal rites. In addition to the thirteen essentials, there are also a large number of customary (sunna) elements that are recommended but not required. Considerable variation exists among the major rites on the sunna elements.

The Salat begins with the worshipper in (a) the ‘standing position’ (qiyam), facing the Ka‘ba in Mecca. In a congregational Salat, whether performed in a mosque or elsewhere, a second call to prayer, called the iqama, is recited, followed by the statement, ‘Worship has begun.’ Then comes (1) the statement of ‘intention’ (niyya), indicating which prayer is about to be performed, followed by (2) a takbira, the statement, ‘God is most great (Allahu Akbar).’ Remaining standing, the worshippers then begin the first rak‘a or liturgical cycle with (3) recitation of al-Fatiha (‘The Opener’), the first sura of the Qur’an:

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.

Praise belongs to God, the Lord of the worlds,

The Merciful, the Compassionate,

The Master of the Day of Judgement.

Thee only do we serve, and to Thee only do we pray for succour.

Guide us on the straight path,

The path of those whom Thou hast blessed, not of those against whom Thou art wrathful, nor of those who go astray.

This is followed by a second recitation from the Qur’an, spoken quietly or silently if in a congregation behind an imam, or recited aloud if the worshipper is alone or at home. Next comes (b) the ‘bowing’ (ruku‘), with the worshippers bending the upper part of the body to a horizontal position with their hands on their knees. In this position they say ‘Glory be to God’ or a longer statement of praise, varying in different rites. The worshippers then straighten up to the standing position (i‘tidal) and, with the hands raised to the sides of the face, say ‘May God hear those who praise Him’, or a longer formula. Then follows (d) the (first) ‘prostration’ (sujud), with the toes, knees, palms and forehead – seven points of the body, or some say ‘seven bones’ – all touching the floor or ground simultaneously. In this position the worshippers say, ‘Praise be to Thee, my Lord, the Most High.’ This is followed by (e) the sitting position called the julus–a half-sitting, half-kneeling position – sitting on the inside of the left foot but with the right foot in a vertical position, with the toes pressed against the floor or carpet (see figure 3.2). In this position another takbira is recited. Then follows a second ‘prostration’, which is required but not counted separately in the lists of essentials. During this prostration the worshippers say, ‘My Lord, forgive me, have mercy on me, grant my portion to me, and guide me.’ This completes the first rak‘a or cycle of the Salat. The second follows immediately as the worshippers stand and recite al-Fatiha again and then proceed through the same sequence of ritual actions and sayings. The morning Salat has two rak‘as, the sunset one has three, and the noon, afternoon and evening ones each have four. After the second prostration of the last rak‘a, the worshipper concludes the Salat by raising the upper part of the body, rolling back until the weight is balanced on the knees and feet (now ‘four points’ instead of seven) in (f) the ‘sitting position’, called qu‘ud. In this final position, worshippers recite the three remaining essential or required elements (arkan): (4) the Shahada (see p. 182 above); (5) a blessing on the Prophet and his family; and (6) the ‘salutation of peace’, called the salam or taslim, simply ‘Peace be upon you (salam ‘alay-kum)’, pronounced twice, once with the head turned to the right and then again with the head turned to the left. Originally this greeting seems to have been intended for one’s guardian or recording angels, but al-Ghazali said it should also be for one’s fellow worshippers, and this later interpretation has become widely accepted. The period of sacred time into which the worshippers enters is said to begin with the first takbira, the statement ‘Allahu Akbar’, and end with the greeting of peace, ‘Salam ‘alay-kum.’ In the Salat, which culminates in the prostration before God, faithful Muslims perform a daily ritual that symbolizes the essence of Islam, submission (islam) before God, the Almighty, and public participation in the rituals instituted by Muhammad. (See [8: VIII – XII; 37: IV] for al-Bukhari’s and Muslim’s hadiths on the Salat; [9: 63–84] for al-Ghazali’s description; and [25: 463–80] for the Shafi’i regulations.)

In the early afternoon on Fridays Muslims throughout the world gather in the central or ‘congregational mosque’ (masjid jami‘ or jami‘ masjid, as in Delhi, India, shown in figure 3.3) in each town, or in any of several in the larger cities, for a special worship service called ‘the assembly’ (al-jum‘a), which takes the place of the regular noon Salat for that day. The mosque (masjid in Arabic) is a unique, Islamic institution that is essentially different from the Jewish and Christian counterparts, the synagogue and the church, and most Muslims do not regard Friday as a holy day or sabbath. S. D. Goitein [20] presented compelling evidence to show that the Muslim practice of observing their weekly worship service at midday on Fridays arose not so much as an alternative to the Jewish and Christian Saturday and Sunday sabbaths as for the practical reason that Friday was the weekly market day in Medina in the time of Muhammad when people from the surrounding area came into the city and thus were available for congregational services and announcements in the mosque.

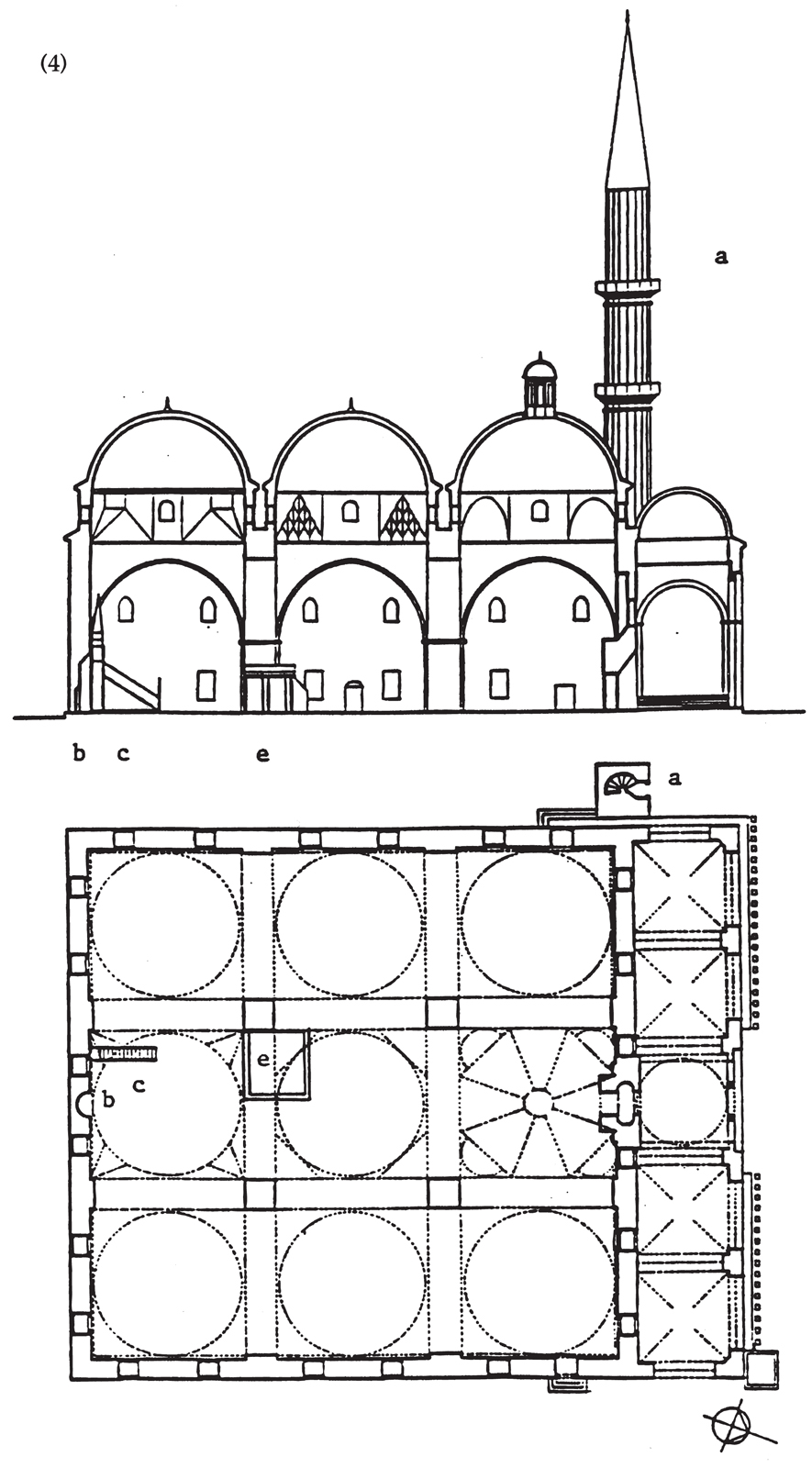

The most characteristic architectural features of the mosque are (a) one or more towers or minarets (Arabic sing., manar) from which the call to prayer is given five times daily, (b) a niche (mihrab) that indicates the direction of Mecca, towards which the worshippers face during the Friday service and for daily prayers performed in a mosque, (c) a pulpit (minbar), often an ornate enclosure with a staircase leading to a platform at the top, from which the Friday sermon is delivered, and (d) some type of fountain, pool or other source of water for ablutions. Some mosques, such as the elegant Eski Cami (Turkish for the Arabic, jami’, ‘congregational’, but sometimes meaning simply mosque) in Edirne, Turkey (shown in figure 3.3) and the historic, superb al-Hasan mosque–school–mausoleum complex in Cairo have (e) a raised, often ornate platform called a dakka or dikka located usually in front of the minbar against a wall or row of columns, but occasionally free-standing in the centre of the worship area in front of the mihrab (for photographs showing the relationships among the mihrab, the minbar and the dikka in Turkish mosques, see [21: 118, 153, 179, 186, 234, 260, and 263–5]). The primary purpose of the dikka is for expert, often professional, reciters (called qurra’) to sit on, with open copies of the Qur’an on stands in front of them, while they chant portions of the Qur’an on special occasions such as the evenings of Ramadan, the month of fasting. The dikka is also often used by the muezzin when chanting the second call to prayer (called the iqama) for the Friday service, indicating to the worshippers that the service is about to begin [21: 264].

Figure 3.3 (1) Jami ‘ Masjid, Delhi, the largest mosque in India, built between 1644 and 1658 by the Great Mughal Shah Jahan; (2) Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem, begun 691; (3) Mosque of al-Hakim, Cairo, built 990–1013; (4) Eski Cami in Edirne, Turkey, built 1403–14

Sources: (1) H. Stierlin (ed.), Islamic India, Architecture of the World no. 8, Lausanne, Compagnie du Livre d’Art, n.d.; (2) A. Choisy, Histoire de l’architecture (Paris, 1899); (3) K. A. C. Creswell and J. W. Allan, A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture, 2nd edn, Aldershot, Scolar, 1989 (prev. publ. London, Penguin 1958); (4) A. Kuran, The Mosque in Early Ottoman Architecture, Chicago/London, University of Chicago Press, 1968

The mosque drawings in figure 3.3 illustrate only three of the many styles of mosque architecture (the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem is not a mosque). (For drawings of seven basic types of mosque designs ranging from sub-Saharan West Africa to China see [17: 13].) The drawings of the Jami‘ Masjid in Delhi and the Eski Cami in Edirne illustrate respectively the distinctive styles of Mughal and Ottoman minarets (marked ‘a’ in the drawings). Probably the best-known examples of the tall, slender Ottoman minarets are those on the massive Muhammad Ali Mosque on the Citadel in Cairo, built in the nineteenth century during the period of Turkish rule of Egypt. The mihrab or niche indicating the direction of Mecca is usually located in the centre of the qibla wall. In figure 3.3 the mihrab (marked ‘b’) can be seen only in the two drawings of the Eski Cami. The reason it cannot be seen in the drawings of the Jami‘ Masjid in Delhi and the al-Hakim Mosque in Cairo is because the qibla wall is not visible (in the back of these two drawings). The high archway leading from the open courtyard to the enclosed area under the large, central dome of the Jami‘ Masjid in Delhi shows the direction towards Mecca and the location of the mihrab in the centre of the back wall. The minbar (marked ‘c’), usually located to the right of the mihrab (when facing towards Mecca), is also shown in figure 3.3 only in the two drawings of the mosque in Edirne. The upper illustration shows a side view of the minbar, while the lower one shows only the steps leading up to the platform from which the Friday sermon is delivered. Some larger mosques, such as the famous Muhammad Ali Mosque and the Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo, have an ornate, domed fountain for ablutions in the centre of the courtyard. The only source of water for ablutions shown in figure 3.3, however, is the large, square pool (marked ‘d’) in the courtyard of the Jami‘ Masjid in Delhi, again typical of the Mughal style of Indo-Pakistani mosques. Men and women enter some mosques through separate doorways that lead to washrooms provided for ablutions; families do not worship together since the men and women line up in separate rows. (See [17: I] and [21: V – VII] for descriptions and photographs of many styles of these five architectural features of mosques; [17: IV – XIII] for discussions of the history and features of mosques in each major geographical area; and [17: XIV – XVI] on the roles of the mosque in contemporary Islamic society.)

The most important mosque officials are the leader (imam) of the Salat; the preacher (khatib), who delivers the Friday sermon (khutba); and the ‘caller (to prayer)’ or muezzin (mu’adhdhin). In smaller mosques these offices are often combined in one or two persons, while in the larger ones several imams, muezzins and sometimes professional Qur’an reciters (qurra’) serve. The ‘essentials’ (arkan) of the Friday worship service are (1) a sermon, usually presented in two parts, followed by (2) a special Salat of two rak‘as called in Arabic the salat al-jum’a, led by the imam. It is recommended that a sunna or ‘customary’ Salat of two rak‘as be performed by the worshippers individually before the service begins. Performing ablutions before the service, wearing perfume, arriving early, and reciting suras from the Qur’an and blessings on the Prophet are also considered sunna and meritorious. (See [8: XI, 34: VII and 25: 537–49] for canonical hadiths on the Friday worship service; [9: 144–72] for al-Ghazali’s description; and [25: 480–1] for the regulations according to the Shafi‘i rite.)

The broad lines of the origin and early development of the Islamic institution of alms-giving during Muhammad’s lifetime are fairly clear. Before the Hijra the sharing of wealth with the poor was stressed in the Qur’an as a pious act, but neither the borrowed technical term zakat nor even the common Arabic noun sadaqa was used. After the Hijra, when the small Muslim community of Emigrants (muhajirun, those who made the Hijra from Mecca to Medina) found themselves in need of support from the new converts in Medina (called the Helpers), alms-giving acquired new significance as an Islamic welfare system in which those who had more income shared with those who did not have enough. But no set amount was stipulated. In response to the question posed by a group of believers, ‘How much do we pay?’ the Qur’an says simply (in 2. 219/217), ‘The surplus! (al-‘afw)’, meaning ‘whatever you do not need’. In the course of time this ‘surplus’ came to be interpreted differently, and a minimum assessable amount called the nisab was set for each type of property. The Zakat then became a tax of a certain percentage of one’s wealth or produce, or a specified ration of livestock. The Zakat was to be paid on food crops and fruit at the time of harvest, on livestock after a full year of grazing, and on precious metals and merchandise on hand at the end of the year. The Zakat system, which varied across different geographical areas and among different legal rites, came to be carefully regulated by the Muslim religious and political leaders. With the establishment of modern secular states throughout the Islamic world, the traditional Zakat was in most cases replaced by national taxation and welfare systems. Only a few countries, such as Saudi Arabia and Libya, have maintained official Zakat systems along traditional lines. In most parts of the Islamic world today alms-giving has become a voluntary practice carried out at the local level. Egypt and a few other countries have large national agencies that collect and distribute Zakat, but still on a completely voluntary basis [8: XXIV; 26: 486–91; 37: V].

During the first year after the Hijra Muhammad instituted a one-day, twenty-four-hour fast called the ‘ashura’ (‘tenth’). This was apparently the name used by the Jews of the Hijaz for the fast on the Day of Atonement, which falls on the tenth day of Tishri. The Qur’an does not mention the Ashura fast, but hadith accounts have much to say about it, acknowledging that it was borrowed from the Jews and that it was kept for a while as an Islamic fast before the Ramadan fast was instituted. The establishment of the thirty-day daytime-only fast of Ramadan seems to have been related to the Muslim victory at the battle of Badr in Ramadan, 624. From the beginning, recitation of the Qur’an had a special place in the Ramadan activities. Later, it became customary for Muslims to recite or read one-thirtieth of the Qur’an each night of the month. For this reason the text has been divided into thirty equal parts, marked with medallions in the margins of most oriental editions of the Qur’an.

The very basic requirements of the Ramadan fast are given in the Qur’an in a passage that appears to have been revised (that is, Muhammad recited it differently on earlier and later occasions); or, as the jurists say, later verses abrogated or cancelled the rulings of earlier ones. Sura 2. 185/181, which seems to have instituted this fast, states that it is to be kept throughout the month of Ramadan, and that anyone who is sick or on a journey may break the fast for those days but must make them up later. Sura 2. 187/183, which appears to have replaced and relaxed some earlier regulations – possibly involving verses that are no longer in the Qur’an – states in part: ‘You are permitted during the night of the fast to go in to your wives … and eat and drink until so much of the dawn appears that a white thread can be distinguished from a black one [at arm’s length away]. Then keep the fast completely until night and do not lie with them when you should remain in the mosques.’ According to later Islamic law the essentials of the fast are that it is to be kept from just before sunrise until just after sunset during the thirty days of Ramadan by all adult Muslims who are in the full possession of their senses; for women, it is to be kept only on those days when they are free from menstruation and the bleeding of childbirth. The fast is regarded as having been broken on any day on which certain violations occur, the exact lists of which vary among the different legal rites. Violations are usually listed in four categories: (1) allowing food, beverages, or anything else, to be swallowed intentionally (in modern times, inhaling tobacco smoke has also been prohibited); (2) intentional vomiting, even when this is done under a doctor’s orders; (3) sexual intercourse; and (4) the emission of semen when caused by any type of sexual activity or thoughts. Muslims are encouraged to break their fast as soon as possible after the sun has set and to eat in the morning as late as possible before sunrise. Indecent talk, gossip, slander and anything else that would cause anger or grief to anyone should also be avoided, along with any actions that might arouse passion in oneself or someone else. Any days during Ramadan on which the fast is broken should be made up as soon as possible during the following month, Shawwal, after the completion of the ‘Id al-Fitr, ‘the Feast of the Breaking [of the Fast]’, which usually lasts for the first three days of the month. Although carefully regulated by Islamic law and custom, fasting by its very nature becomes a voluntary act of piety on the part of the observant Muslim. (See [8: XXXI; 26: 88–123; 37: VI] for canonical hadiths on fasting; [25: 491–6] for regulations according to the Shafi‘i rite.)

The fifth pillar of Islam is the Great Pilgrimage or Hajj, which consists of a number of rituals performed at sacred monuments in and near Mecca. The Hajj is required of all Muslims at least once in a lifetime if they are physically able to make the trip and can afford it (see figure 3.4). From before the time of Muhammad these rituals have been divided into two groups, originally performed at different times of the year (during the great market days in the spring and in the fall), the ‘umra (visitation [to Mecca]) and the hajj (pilgrimage). The ‘umra rituals take place in and near the Sacred Mosque in Mecca and now can be performed at any time of the year as an independent ritual called the ‘Lesser Pilgrimage’ or simply the ‘Umra. The hajj rituals take place outside of Mecca, beginning in the nearby town of Mina and proceeding out to ‘Arafat and back. The Islamic Great Pilgrimage, also called the Hajj, combines the ancient ‘umra and hajj rituals. It can be performed only on certain days of Dhu-l-Hijja, the twelfth month of the Islamic calendar (see figure 3.5). Islamic law and custom stipulate three methods of performing these two groups of ceremonies: (1) ‘one by one’ (ifrad), the preferred method, completing the hajj ceremonies (that is, those that occur outside of Mecca) first, and then the ‘umra ones; (2) ‘enjoyment’ (tamattu‘), performing the ‘umra rituals first and then breaking the state of ritual purity or sanctification (ihram) to enjoy the pleasures of Mecca for a few days before resuming the ihram for the hajj rituals; and (3) ‘conjunction’ (qiran), beginning the ‘umra rituals and then the hajj ones, and then completing both at the same time.

For several days and even weeks before the Hajj begins, a steady stream of pilgrims, numbering nearly 2 million in recent years, flows into Mecca. Before crossing into the haram, the sacred territory that surrounds Mecca, the pilgrims enter a state of ritual purity (ihram) by performing a major ablution (ghusl) and a special Salat of two rak‘as, expressing their ‘intention’ (niyya) to perform one of the three types of pilgrimage mentioned above, and then donning a white, seamless garment, called also an ihram. On entering Mecca all pilgrims visit the Sacred Mosque as soon as possible and perform a sevenfold circumambulation (tawaf) of the Ka‘ba. Then they perform a Salat of two rak‘as and drink from the nearby sacred well called Zamzam. Those who intend to fulfil an ‘Umra, either as a ceremony separate from the Hajj proper – essentially a mark of respect paid to the city, especially for those entering it for the first time – or as the ‘umra portion of a tamattu‘ performance of the Hajj, then leave the courtyard of the Sacred Mosque and climb the stairs to the hill called al-Safa, the site of an ancient sanctuary. Here begins the second major ceremony of the ‘Umra, the ‘running’ (sa‘y) between al-Safa and al-Marwa, another hill about 385 metres away. First, the ‘intention’ to perform the ‘running’ ceremony is expressed and verses from the Qur’an and other pious sayings are recited. Then the pilgrims traverse ‘the running course’ (al-mas‘a), walking part of the way and running part of the way. On al-Marwa they face the Ka‘ba and recite more pious sayings, and then retrace their steps back to al-Safa. They go back and forth until they have traversed ‘the running course’ seven times, thus ending up at al-Marwa, where a ritual desacralization is performed by having their hair shaved off or simply trimmed or, for women, having a single lock of hair cut off. Those pilgrims who follow the other two methods (ifrad and qiran) are not required to perform the ‘running’ ceremony before the hajj rituals that take place outside of Mecca.

Figure 3.5 The Hajj: the route followed by the Hajji in and near Mecca (the distance from Mecca to ‘Arafat is about 24 km)

On the 7th of Dhu-1-Hijja the pilgrimage ceremonies are officially opened with a service at the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which includes a ritual purification of the inside of the Ka‘ba and a sermon or khutba delivered from the ornate stone pulpit (minbar) that stands nearby. According to the pilgrimage manuals the hajj portion of the rituals then begins on the 8th of Dhu-1-Hijja in Mina (a small uninhabited village about 8 km east of Mecca), where the pilgrims are supposed to assemble and spend the night. After the morning prayer on the 9th they are supposed to depart together for the great plain of ‘Arafat, about 15 km further east. In fact, in recent years the crowd has been so large that many leave Mina for ‘Arafat on the 8th, and others, especially the Shi‘is travelling in from Iran and Iraq, simply assemble at ‘Arafat on the evening of the 8th or the morning of the 9th. Just after noon on the 9th the pilgrims gather on or near the small knoll called the Mount of Mercy (Jabal al-Rahma), located at the eastern edge of the plain. Here they recite the noon and afternoon Salats together and then perform what has been called the central ritual of the entire pilgrimage, the ‘standing’ (wuquf) ceremony, which lasts until sunset. A sermon is delivered by one of the leading imams, commemorating Muhammad’s Farewell Sermon, given on this hill during the pilgrimage he led in the last year of his life. As soon as the sun has set, cannon-fire marks the end of the wuquf, and the throng of pilgrims leave ‘Arafat immediately and begin the ‘flight’ (ifada) back towards Mecca. They stop in the valley of Muzdalifa, about half-way back to Mina. Here they perform the sunset and evening Salats together, have a light meal and then gather a number of stones, usually in multiples of seven, for use later back in Mina. According to tradition and the Hajj manuals, the men are to spend the night in Muzdalifa, while it is customary for the women, children and elderly men to proceed on to Mina for the night.