5

Hinduism

Introduction

What is Hinduism?

The word Hinduism is used to refer to the complex religious tradition which has evolved organically in the Indian subcontinent over several thousand years and is today represented by the highly diverse beliefs and practices of more than 650 million Hindus. Apart from communities in neighbouring states, and those communities in such places as Bali, South-West Africa and the Caribbean that have been created by migration (together forming less than 10 per cent of the totality), the majority of Hindus live in India, where they constitute over four-fifths of the entire population. Hinduism is so diverse internally that the only way of defining it acceptably is externally, in terms of people and places; the term ‘Hindu’ is, in origin, simply the Persian word for Indian. The land of India is crucial to Hinduism; its sacred geography is honoured by pilgrimages and other ritual acts and has become deeply embedded in Hindu mythology and scriptures.

There are two principal reasons why it is preferable to regard Hinduism as an evolving religious tradition rather than as a single, separate ‘religion’ in the sense that the term is usually understood. The first reason is that Hinduism displays few of the characteristics that are generally expected of a religion. It has no founder, nor is it prophetic. It is not creedal, nor is any particular doctrine, dogma or practice held to be essential to it. It is not a system of theology, nor a single moral code, and the concept of god is not central to it. There is no specific scripture or work regarded as being uniquely authoritative. Finally, it is not sustained by an ecclesiastical organization. Thus it is difficult to categorize Hinduism as a ‘religion’ using normally accepted criteria.

The second reason for this preference is the extraordinary diversity of Hinduism, both historically and in the contemporary situation. Such diversity is scarcely surprising when it is remembered that Hinduism refers to the mainstream of religious development of a huge subcontinent over a period of several thousand years, during which time it has been subject to numerous incursions from alien races and cultures. The subcontinent is not only vast, but is also marked by considerable regional variation. Regions differ from one another geographically, in terms of terrain, climate, natural resources, communications etc., and also ethnographically, in terms of the many and varied ethnic, cultural and linguistic groupings that inhabit them. Diversity is, therefore, to be expected in almost every domain.

Hinduism evolved organically, with new initiatives and developments taking place within the tradition, as well as by interaction with and adjustment to other traditions and cults which were then assimilated into the Hindu fold. These two processes of evolution and assimilation have produced an enormous variety of religious systems, beliefs and practices. At one end of the scale are innumerable small, unsophisticated local cults known only to perhaps two or three villages. At the other end of the scale are major religious movements with millions of adherents across the entire subcontinent. Such movements have their own theologies, mythologies and codes of ritual and could, with justice, be regarded as religions in their own right.

It is, then, possible to find groups of Hindus whose respective faiths have almost nothing in common with one another, and it is also impossible to identify any universal belief or practice that is common to all Hindus. Confronted with such diversity, what is it that makes Hinduism a single religious tradition and not a loose confederation of many different traditions? The common Indian origin, the historical continuity, the sense of a shared heritage and a family relationship between the various parts: all these are certainly important factors. But these all equally apply to Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, each of which arose within the Hindu tradition but separated from it to become an independent religion. Crucial, however, is the fact that Hindus affirm it is one single religion. Every time a Hindu accepts someone as a fellow Hindu, in spite of what may be radical differences of faith and practice, he is making this affirmation. Whatever its seeds, Hindu self-awareness certainly developed in early confrontations with Buddhists and Jains, acquired greater potency as Hinduism was confronted by Islam and then Christianity, and finally was considerably strengthened in recent times by the growth of nationalism and political identity. It is Hindu self-awareness and self-identity that affirm Hinduism to be one single religious universe, no matter how richly varied its contents, and make it a significant and potent force alongside the other religions of the world.

Approaches to Hinduism

The first attested usage of the word ‘Hinduism’ in English was as late as 1829. This is not to say that the beliefs and practices of the Hindus, or ‘Gentoos’ as they were referred to in the eighteenth century, had not been previously studied. Indeed, serious work had already begun, spurred on by the exciting ‘discovery’ of Sanskrit and the realization that it was related to Latin and Greek [1: I]. Philological work, the editing and translation of texts, has been a continuing and major scholarly concern. Because the corpus of religious and philosophical works is so vast, however, there still remains much that awaits thorough investigation. Nevertheless the huge body of religious writings, sometimes referred to as Hindu scriptures, has helped to form a mistaken view of Hinduism. Certainly these works are of primary importance. But it must be remembered that they were written by a priestly elite, the Brahmans, and are, of necessity, unrepresentative of the beliefs and practices of the great majority of Hindus at any given time. They are, moreover, not a coherent corpus, but as diverse as the history of Hinduism itself. Some authors, through excessive reliance on texts, and through failing to place these texts in their overall contexts, have perpetuated an image of Hinduism as being concerned solely with the higher realms of metaphysical and theological teachings when, in fact, a very great deal more is entailed.

Early observers in contact with the everyday realities of Hinduism, understanding the writings, beliefs and practices of the Brahmans to represent the true ‘orthodoxy’, were thus obliged to relegate much of what they found to the status of folklore and superstition. More recently, ethnographic and anthropological research has gone a long way towards removing this misleading polarization and has partly succeeded in integrating both aspects into a single totality. This process has itself generated further dualities, however, such as ‘the great tradition’ and ‘the little tradition’, which may prove in the long run to be equally unhelpful.

The Christian missionaries were highly critical of most of what they encountered in India, although they welcomed monotheism wherever they found it as providing further evidence of the universality of this phenomenon. Subjected to the scorn of the missionaries, the more Westernized and educated Hindus took the opportunity that the new word ‘Hinduism’ offered to reinterpret and project Hinduism almost as they wished, since it was never clear precisely what the term referred to. As will be seen later, Hinduism came to be projected as ‘the most ancient and mother of all religions’, and through being, by implication, the best of all religions, it was naturally the most tolerant. This new mythology was coupled with the notion of the spiritual East and the materialistic West, as if there were no spirituality in the West and no materialism in the East. Such dubious popular images were supported by the equally false notion of the changelessness of India. In fact Hinduism and India are characterized by both continuity and change, and no single image can be appropriate either to so complex an agglomeration as Hinduism or to so vast a continent as India.

There is still a relativism in the use of the word Hinduism. To someone reading the literature it becomes clear that there are almost as many ‘Hinduisms’ as there are authors who write about it. Recently one scholar has commented trenchantly on the term Hinduism, describing it as ‘a particularly false conceptualization, one that is conspicuously incompatible with any adequate understanding of the religious outlook of Hindus’. While the arguments cannot be rehearsed here, there is much validity in them, although it is improbable that his wish to have the word dropped will ever be fulfilled. The word is here to stay. In this chapter it will be used as many now use it to embrace the totality of beliefs and practices of all Hindus, both as they are now, and as they have evolved over the centuries [1; 2; 3; 5; 15].

History and Sources of Hinduism

All that is known of the earliest stage of religious life in India – designated by some as protohistoric Hinduism – is derived from excavated seals and statuettes belonging to the Indus valley civilization (?4000–1750 BCE) [1: I] (see figure 5.1). These are usually interpreted as indicating that veneration was shown to a male god, seated in a yogic posture and displaying characteristics of the god known in later Hinduism as Shiva (see figures 5.4–5.6 below); also to female goddesses, phallic symbols and certain animals and trees. Ritual purification with water seems also to have been an important element. Fragmentary as these details are, however, all of these features reappear in classical Hinduism and are widespread in current belief and practice – testimony to the persistence of religious forms in India [1: II].

The second historical phase, that of Vedism or Vedic religion, is usually taken to extend from about the middle of the second millennium BCE to about 500 BCE. It was ushered in by the arrival of the semi-nomadic Aryan tribes who, by conquest and by settlement and assimilation, spread during these centuries across north India. The Aryans were that branch of the Indo-European peoples who moved down into Iran and Afghanistan and then into India. What is known of their religion when they were in India derives mainly from the Veda, a remarkable corpus of religious literature which displays a considerable evolution of religious attitudes throughout the period [1: 11].

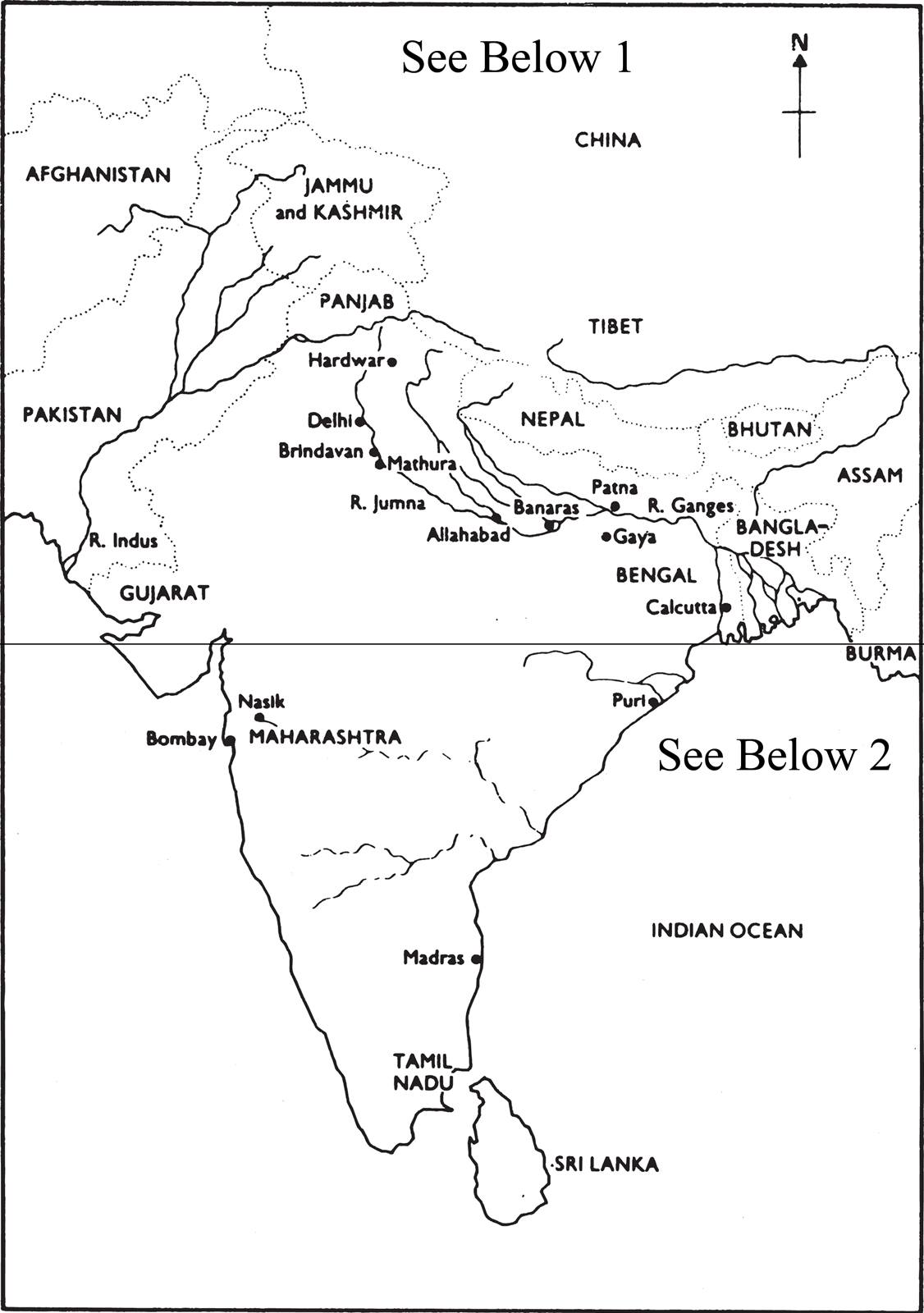

Figure 5.1 General map of India

The oldest of these works is the Rig-veda, a collection of hymns addressed to various gods or divine powers (devas) and used during the main official religious rites. These rites centred on fire sacrifices and the use of a sacred plant, Soma, from which a drink was made which was believed to heighten spiritual awareness [24]. The ceremonies were complex and required specialist priests, for whose use two further works, the Sama-veda and the Yajur-veda, were added to the corpus. Alongside the official religion there was a domestic cult requiring rites to be performed by the householder. The fourth and latest work, the Atharva-veda, presumably also intended for domestic use, contains magical spells and charms to cope with a wide range of natural and supernatural situations. This early acceptance of a very wide range of religious concern, from the cosmological to the magical, must have greatly facilitated the assimilation of indigenous cults and tribes into the Aryan fold [21; 23].

The next stage in Vedic development is found in the Brahmanas, prose commentaries containing practical and mythological details relating to the sacrifice. Here ritualism is pre-eminent. No longer was it the response of the devas to human praise and offerings that ensured the welfare of man and the order of the cosmos, but rather the correct performance of the sacrifice itself. This major change in the status of the sacrifice weakened the position of the devas, a position further undermined by the search for one single underlying cosmic power which was thought to be the source of the devas and their powers. This one great cosmic power was sometimes personalized – as Prajapati or Purusha, for example – but eventually was conceived of as the single impersonal absolute called brahman. Brahman’s seat was the sacrifice, and knowledge of brahman was the key to cosmic control. Another trend that becomes apparent about this time is that of asceticism and meditation, which were represented as being the internalization of the sacrifice within man, the microcosm [5; 21; 23].

The final stage of Vedic evolution is found in the last works of the Veda proper, the Upanishads [20; 21]. Here the emphasis is away from ritual towards the personal and mystical experiencing of the One. When the various worldly influences are reduced, the human self (atman) is able to experience itself as, or at one with, brahman. Here for the first time too the very important doctrine of samsara appears. Samsara is the endless cycle of birth and rebirth to which each soul is subject until it obtains liberation (mukti or moksha) in brahman. The conditions of each birth are determined by the acts (karma) performed during the previous life. Whereas the early hymns were little concerned with the afterlife, now the major preoccupation is how to escape from the cycle of birth and rebirth [1: VII; 5; 21; 23].

The ten centuries from about 500 BCE to 500 CE are the period of classical Hinduism. Because the chronology is problematic it will be better to review the main religious developments thematically. Certainly the period began in a time of great ferment. The Vedic cult was in decline. The Upanishads and the quest for moksha represented a turning away from the world. Meanwhile a new merchant class was flourishing whose members either supported their own non-Vedic cults or else followed the new sects that were then arising, of which Buddhism and Jainism were to become the most important. The Brahmans, as priests, could well have lost much influence in consequence, but they were also the educated elite, sole guardians of Sanskrit and the textual traditions. It is they who were the principal agents in creating a sufficiently flexible religious and social framework within which they were able to assimilate the new classes, peoples and cults. One of the main powers and functions of the Brahmans at this time was that of legitimation. Perhaps the first really significant exercise of that power, as well as the first affirmation of Hindu self-awareness, was to establish allegiance to the Veda, however contrived, as the criterion of orthodoxy. In consequence, some of the newly arisen sects, notably Buddhism and Jainism, were treated as heterodox and separated to go their own way, although cross-fertilization continued for many centuries [1: II, VII].

The change of emphasis to living-in-the-world was firmly established in the religious law books, dharma sutras and dharma shastras, which codified how Hindu society should be and how Hindus should live, at least according to Brahmanical prescription. The essential concept was varnashrama dharma, that is, the duties or right way of living of each of the four classes of society (varnas) in each of the four stages of life (ashramas). Although there is also a general dharma, righteousness or moral code, incumbent on all, this relativist code of behaviour was founded on the belief that people are not the same and that their duties or ethics vary according to who they are and where they are in life. The four varnas – Brahmans (priests and teachers), Kshatriyas (rulers and warriors), Vaishyas (merchants and cultivators) and Shudras (menials) – were ordered hierarchically on Vedic authority; the first three, the ‘twice-born’, had full religious rights, while those of the menials were much restricted. Unsubjugated tribes or groups with unacceptable practices were considered ‘untouchables’ and outside the Hindu pale. These prescriptive works, the dharma shastras, deal with domestic rituals, life-cycle rites, sin, expiation, ritual pollution, purification and many other matters fundamental to the Hindu way of life [13]. The three aims of life were dharma, the acquisition of religious merit through right living, artha, the lawful making of wealth, and kama, the satisfaction of desires, thus embracing the major aspects of human life. Only later was moksha, the quest for liberation, added as the fourth. Right living in this world, dharma, had displaced moksha, liberation from this world, at the very centre of Hinduism [1; 13; 28; 30; 32]. But moksha was never ignored. It was explored by schools of speculative philosophy, often with very sophisticated metaphysical systems, all purporting to be valid means of salvation. Six of these darshanas (doctrines) were accepted as orthodox, but only one of them, Vedanta, was to evolve and play an important part in the later development of Hinduism [5; 29].

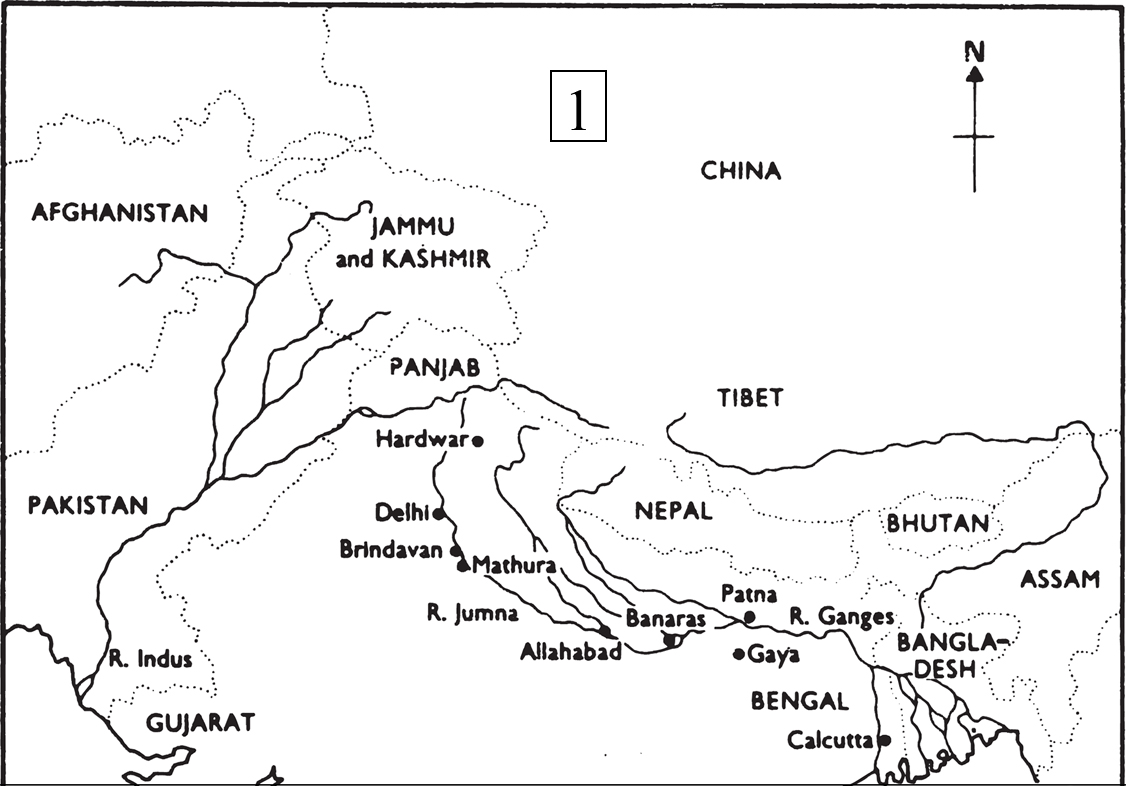

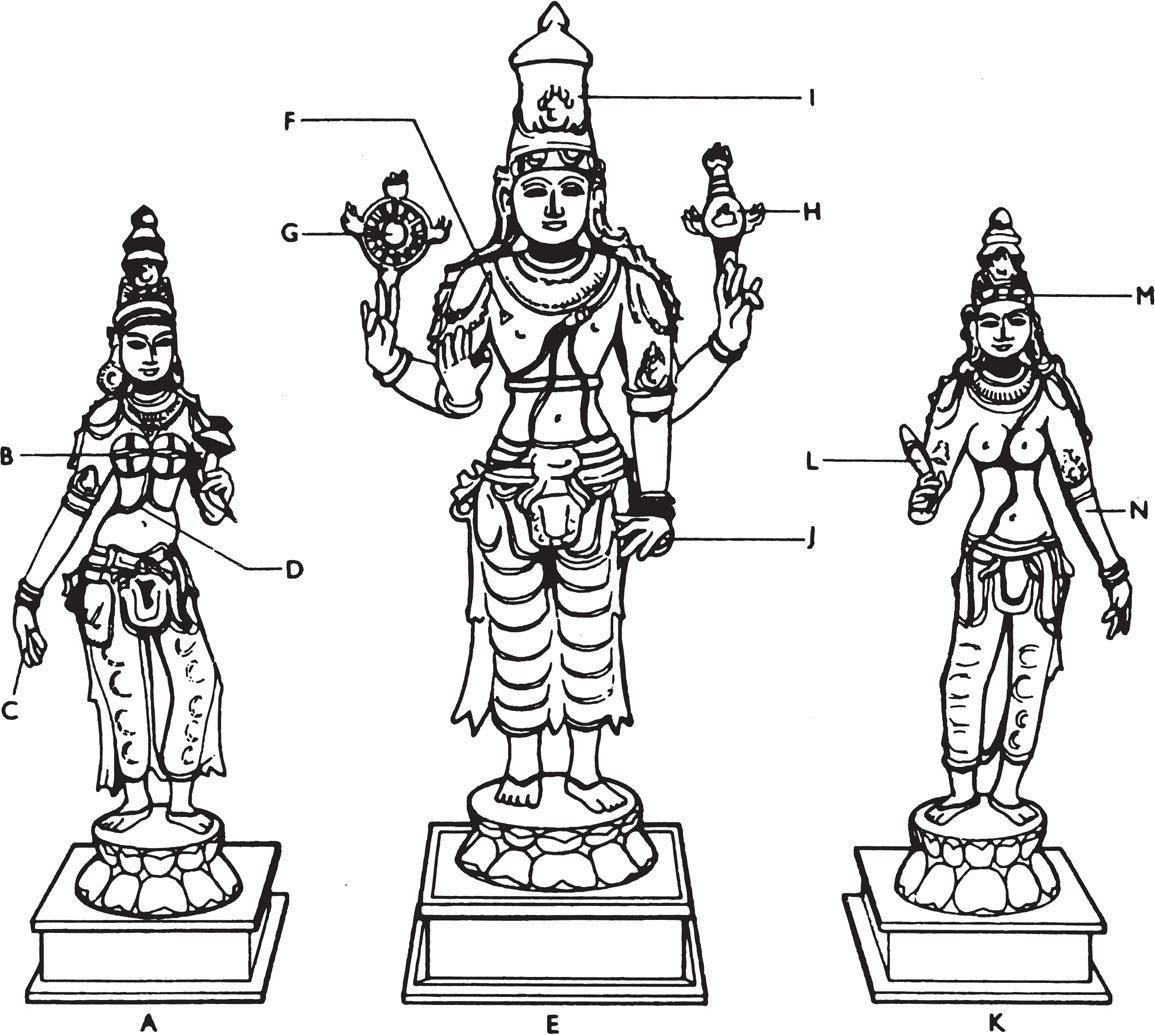

- A Cakra (discus), a weapon and a symbol of kingly power

- B Shankha (conch), used as a trumpet in both war and ritual

- C Vana-mala – a garland of forest flowers. Often worn by Vishnu and Krishna.

- D Sectarian mark, as worn by Vishnu’s devotees

- E Gada (mace)

- F Yajnopavita, the sacred thread

- G Padma (lotus), representing beauty and purity, often associated with Vishnu’s wife Lakshmi and other goddesses

A, B, E and G are the four most usual attributes by which Vishnu is identified

Figure 5.2 Vishnu and his attributes

There is ample evidence that non-Vedic theistic cults were widespread throughout the Vedic period. The process whereby these cults and divinities were brought within Hinduism and somehow connected to the Veda is both complex and little known. Suffice it to say that, for Hinduism, the rise, or re-emergence, of theism was one of the most profound developments of the period. Two gods, Vishnu and Shiva, both relatively unimportant in the Veda, became pre-eminent, although many other gods were also worshipped [4; 7; 16].

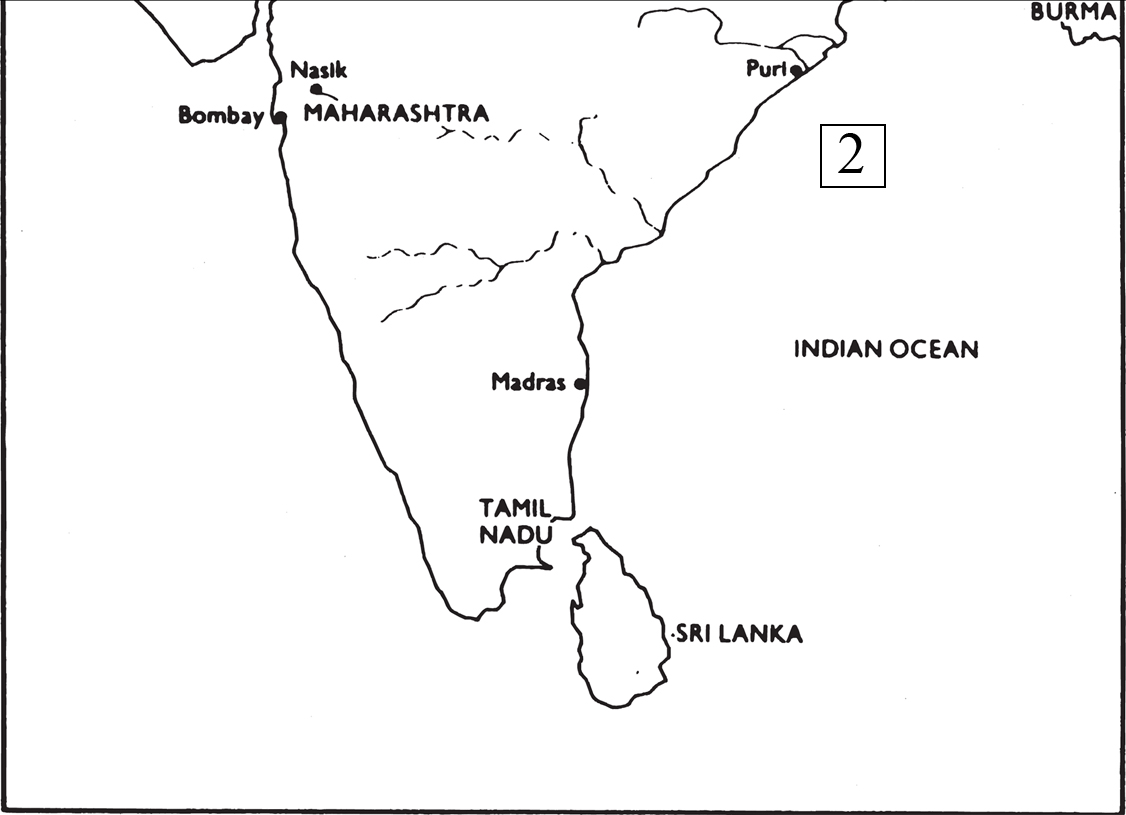

Vishnu (see figures 5.2 and 5.3) came to be identified with various existing deities, and this syncretism has given him the character of a benevolent god, concerned for the welfare of the world, who periodically, in times of moral decline, descends to the world in various forms and guises to restore righteousness. There are believed to be ten such descents (avataras) of Vishnu. Some of these are in the form of giant animals: the Fish, the Boar and the Tortoise. Then there is a Man-Lion and a Dwarf. But the most important in terms of devotion are Krishna and Rama, the seventh and eighth avataras. The mythology of these two is very elaborate. Krishna is worshipped in three forms: as a divine infant; as a mischievous youth who plays the flute and wins the hearts of the cowherd girls (gopis); and as a mighty hero. Rama, who like Krishna is a prince, restored righteousness to the earth by destroying the demon Ravana who had abducted his wife Sita. The word for a devotee of Vishnu, however he is worshipped, is Vaishnava (also an adjective meaning ‘relating to Vishnu’) and the entire cult of Vishnu is referred to as Vaishnavism [1: VII; 4; 7; 16; 31].

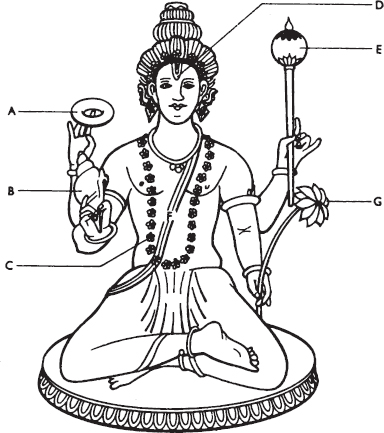

Shiva is also syncretic, but the various elements that go to form the mythology of Shiva are not represented as being separate avataras as in the case of Vishnu, but rather as different aspects of the god’s complex character. In fact, Shiva is not thought to descend to the earth and take on a form; rather, he intervenes to help those who worship him. Shiva’s character has various facets (see figures 5.4, 5.5 and 5.6). He is to some a loving god, full of grace towards his devotees. But there is also the dark side, Shiva the destroyer, who is fearsome and frequents cremation grounds and other frightening places. Shiva is also represented as the Lord of the dance (figure 5.6), as a great ascetic god meditating on the Himalayan Mount Kailash and, as the Lord of the beasts, also as a god of procreation. The word for a devotee of Shiva is Shaiva, which is also an adjective meaning relating to Shiva, and the cult of Shiva is referred to as Shaivism.

Vishnu’s wife is Lakshmi, goddess of prosperity (see figure 5.7). The wife of Shiva is Durga (figure 5.8) in her fierce aspect, and Parvati in her benevolent form (figure 5.5). It was around Durga–Parvati that, at the end of this period, the Mother Goddess cult re-emerged. Its followers were called Shaktas because they believed the goddess to be the immanent active energy (shakti) of the transcendent and remote Shiva who was otherwise inaccessible [1: VII; 4; 5; 7; 16; 17; 31].

- A Shridevi (Lakshmi), goddess of good fortune, standing as the first wife on the right

- B Breast band, sign of the senior wife

- C Hand in pose of relaxation

- D The elaborate arrangement of threads on the chest is characteristic of Lakshmi. Vishnu and Bhudevi both wear the simpler form of sacred thread (yajnopavita). Although mortal women do not wear the thread, goddesses can be so shown

- E Vishnu as ‘Abode of Shri’ (splendour, good fortune)

- F Shrivatsa (‘beloved of Shri’) mark on Vishnu’s chest

- G Cakra (discus or quoit), decorated with flames

- H Conch, decorated with flames

- I Kingly crown (kirita mukuta) and ornaments

- J Hand on thigh, symbolizing that for his worshippers the ocean of samsare is only thigh deep

- K Bhudevi (Prithvi), the Earth Goddess, the second wife

- L Water-lily bud (the Earth Goddess flower)

- M Queen’s crown (karanda-mukuta)

- N Pose of relaxation

Figure 5.3 Vishnu as Shrinivasa with consorts (south Indian bronzes from Srinivasanallur, Tiruchirapalli district, fifteenth/sixteenth century CE)

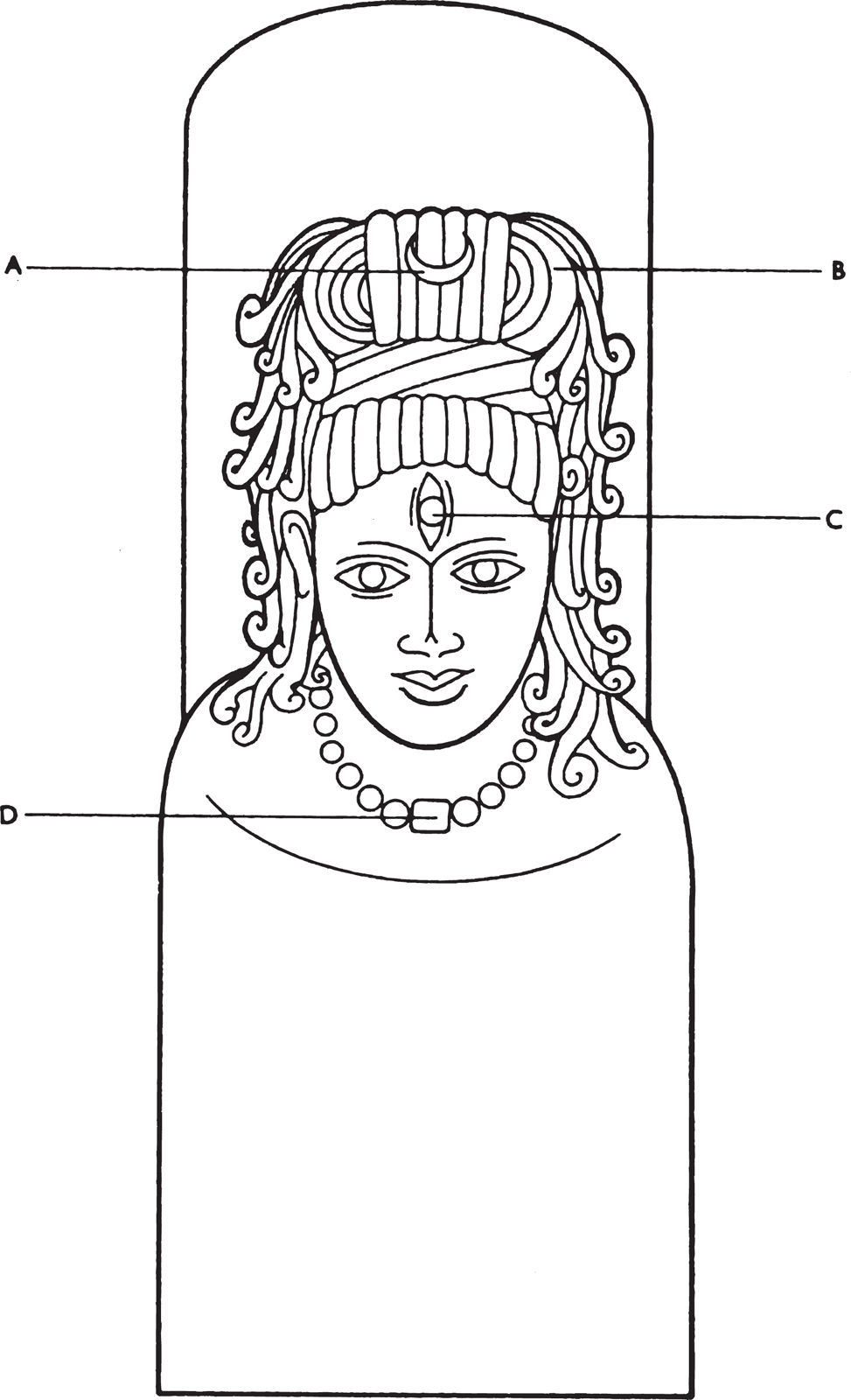

- A Crescent moon

- B Jata, the ascetic’s unkempt locks of hair

- C Third eye, representing Shiva’s wisdom but also his power of destruction – he can blast enemies with fire from it. It is a sign of yogic power

- D Rudraksha-mala, a rosary of Rudraksha (eye of Shiva) seeds, sacred to Shiva.

Only the upper part of the sculpture would have been visible: It was made to fit into a pedestal (possible representing the yoni)

Figure 5.4 Eka-mukha-linga (lingam with one face of Shiva)

- A Shiva, with third eye, snake necklace, the typical ear-rings and long unkempt hair of an ascetic. He wears only a kaupina (G-string)

- B Parvati serves him with bhang (cannabis in yoghurt). She is shown in the costume of a lady of the time and place when the drawing was made (note the nose ornament and ear-ring)

- C The Goddess’s lion

- D Ganesha, here shown as a four-armed child eating laddus with Shiva’s animal mount

- E Nandi, Shiva’s bull

- F Karttikeya, the six-headed, six-armed war god shown here as a child, feeding his peacock mount

Figure 5.5 The domestic life of Shiva and Parvati (from a late eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century Kangra drawing for a miniature in the British Museum)

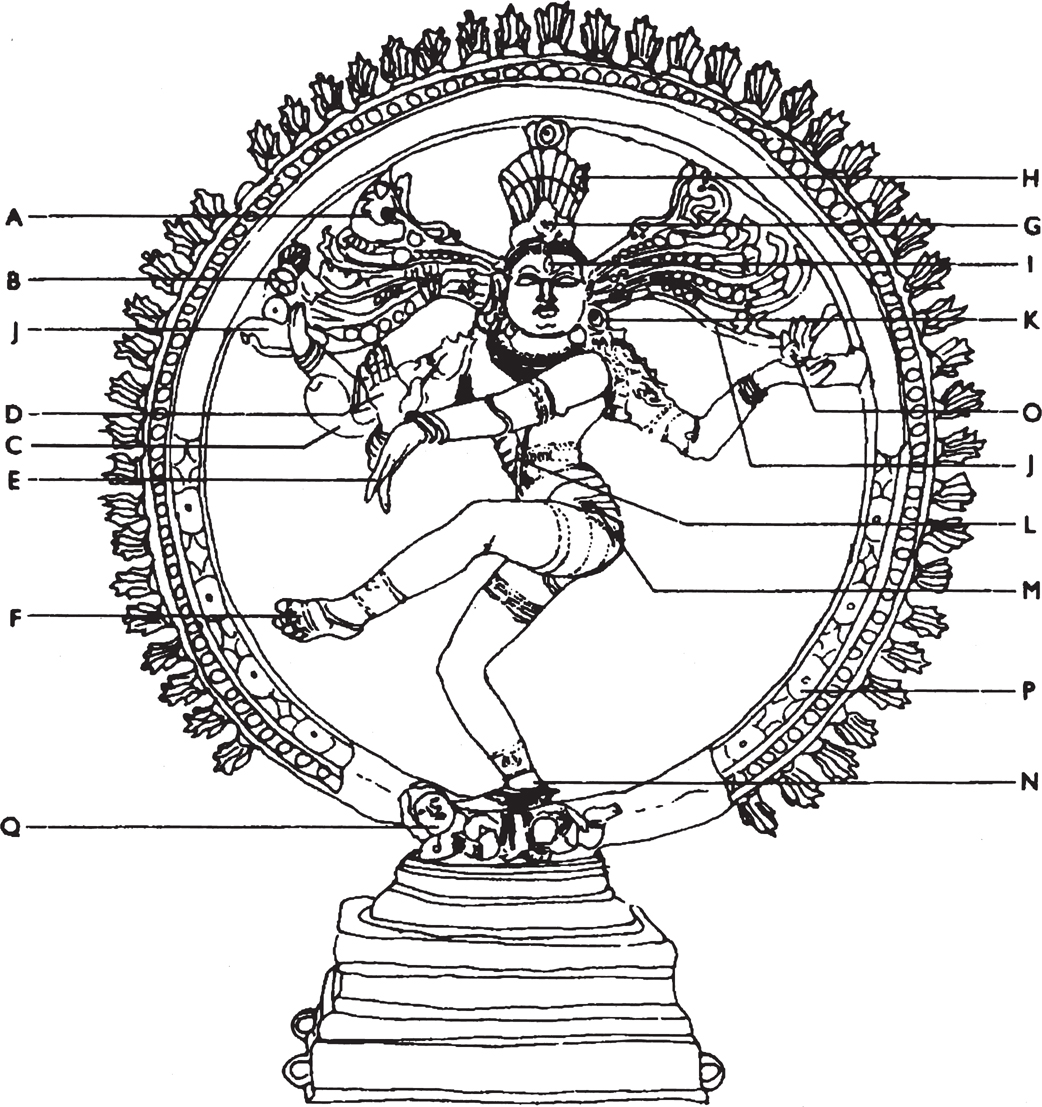

- A Goddess of River Ganga, which flows from Shiva’s hair. She is here shown as a snake-tailed woman in the gesture of namaskara (to honour Shiva)

- B Drum, giving the rhythm of the dance of creation

- C Cobra

- D Abhaya-mudra, the gesture granting freedom from fear

- E Hand pointing to the raised foot signifies salvation

- F The upraised foot, coming forward from the circle, represents salvation

- G Skull, symbol of the ascetic

- H Moon

- I Third eye

- J Long swirling locks full of flowers and snakes

- K One male, one female ear-ring because Shiva combines attributes of both sexes

- L Sacred thread

- M Short dhoti of the ascetic

- N The dance steps are the creation and destruction of universes. Shiva dances on one spot, at the centre of the universe/the human mind-heart

- O Fire, the periodic destruction and recreation of the universe

- P Ornamental prabha-mandala, the circle of glory, representing the universe/human heart

- Q Demon of Ignorance, who is glad to be trodden on by the God

Figure 5.6 Shiva as Nataraja, king of dancers

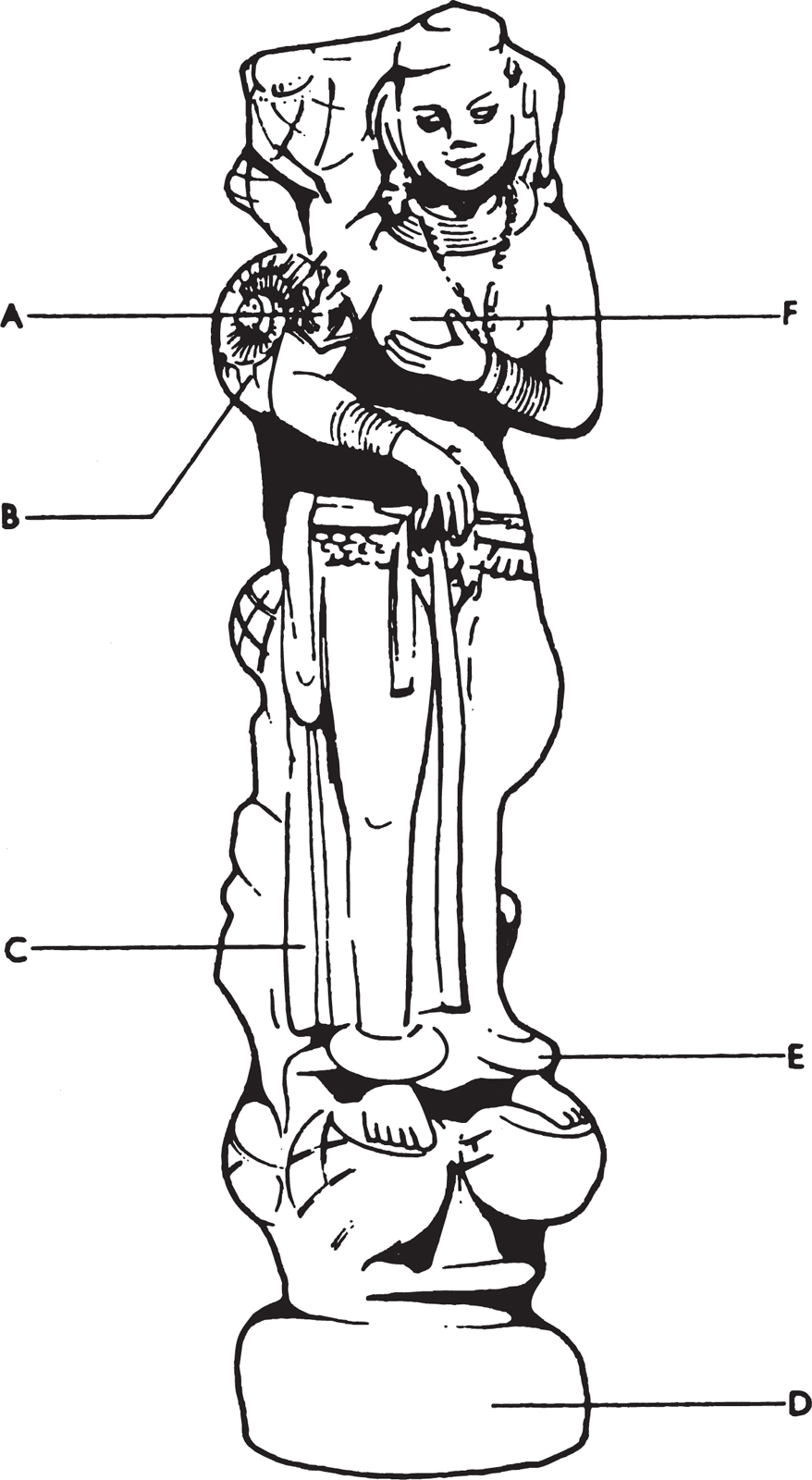

- A Armband in the shape of a peacock

- B The back of the image is carved with peacocks and lotuses. Peacocks are associated with the rainy season, hence fertility

- C Diaphanous skirt, characteristic of the style from Mathura

- D Pedestal, taking the form of the purnaghata (‘full vase’) of lotuses, which is still associated with Lakshmi

- E Heavy anklets – the goddess is shown richly adorned

- F She offers her breast and unfastens her garment, suggesting her power of fertility

Figure 5.7 Lakshmi, as goddess of prosperity (Kushana, second/fourth centuries CE). This early image represents Lakshmi (who is Kamala, the lotus goddess) in association with symbols of water, fertility and female beauty

- A halo (prabha-mandala)

- B Varada-mudra, the gesture of granting favours (the small round object in the palm is perhaps a wishing gem). This suggests her benevolence to her worshippers

- C The sword and the buckler (seen from the inner side) represent the goddess in her fierce aspect, in which she fights demons. The image combines fierce and gentle aspects

- D Conch shell, showing that Durga is a shakti of Vishnu as well as of Shiva (In mythology she is Vishnu’s sister, and Shiva’s wife)

- E Lion, the mount (vahana) of Durga

- F Lotus footstool and pedestal

Figure 5.8 Durga and her attributes (from a c. tenth-century relief from eastern India)

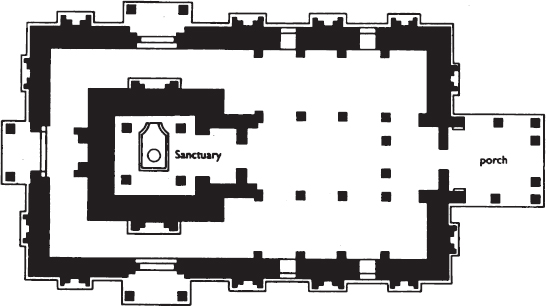

The two great epics, the Ramayana and, particularly, the Mahabharata, are rich encyclopedic sources for the religion of this period [19]. Included in the Mahabharata is the Bhagavadgita, a poem which has become one of the most influential Hindu scriptures [14]. In it Lord Krishna speaks of three ways to salvation: that of enlightenment; that of action, including religious rites; and, the most highly recommended, that of loving devotion to the Lord (bhakti). It is bhakti that has inspired and informed the greater part of Hinduism to the present day [5; 14]. Other consequent developments also took place. The Vedic sacrificial rites had to give ground to new forms of worship (puja), often performed in front of an image or a statue symbolizing or representing the deity in question. A rich mythological literature evolved in works called Puranas, and temple-building began, so that, by the end of this period of classical Hinduism, temples must have been a familiar feature of the landscape (see figure 5.9). The characteristic features of Hindu temples are: (1) a ‘sanctuary’ housing the image, referred to as the garbha-griha (or ‘womb-house’); (2) a spire (shikhara) over the sanctuary; and (3) a porch or canopy [4; 15].

The next period, that of middle or medieval Hinduism, from the sixth century to the nineteenth century of our era, is characterized by proliferation in almost every domain. It is also interesting that many of the major initiatives, especially in the earlier centuries, took place in the south of India where Buddhism and Jainism were in decline and new Hindu kingdoms arose fostering Hindu self-awareness [1: III, VII]. At a social level this period saw the proliferation of castes (jatis), but no theory as to their origin is, as yet, conclusive. It is not thought that they arose through the mixing of the four classes (varnas), from which they differ substantially, but clearly the varna model of hierarchy, specialization of functions and social separation provided an ideological backing. Whatever the defects of the system, and various sects attacked it vehemently, it served to provide social stability in times of political turbulence, to ensure the continuity of a richly diversified culture, and, above all, to give Hindus a social identity, even if it was not the identity that they themselves wished [1; 40].

Figure 5.9 Plan of the Svarga Brahma temple, Alampur (seventh century CE). In the appropriate niches of the outer walls are positioned the Dikpalas, the guardians of the eight directions of space

The major developments in religious philosophy, the darshanas, or schools of salvation, took place within Vedanta. Shankara (?788–850 CE), who advocated the way of knowledge (jnana), formulated his system of Advaita, non-duality, as an exposition of Upanishadic thought, and also founded a monastic order which was to be the forerunner of many others [9; 22]. The Advaita position is held by many Hindus to this day. Briefly, Shankara asserted that only brahman was real; all else, including the phenomenal world, the sense of individuality, even the devas, was unreal, only appearing to be real because of maya, brahman’s power of illusion. When the human spirit, through meditation and enlightenment, realizes that it is itself of the substance of brahman and has no separate identity, then it merges with brahman, as the drop is absorbed in the ocean. This non-dualistic position, that the soul and God are of the same substance, is unsatisfactory for theists, because it does not allow for there to be a relationship between the individual soul and God. Thus in the twelfth century Ramanuja produced a system called Vishishtadvaita, differentiated non-duality, which, while accepting that the soul and God were of the same essence, also taught that the individual soul retained its self-consciousness, and hence was able to exist in an eternal relationship with God [8; 9; 22]. This new system of Ramanuja opened the way for theism, especially Vaishnavism, within Vedanta, and provided the initial theological impetus for later schools such as those founded by Madhva (thirteenth century), Nimbarka (fourteenth century), Vallabha (sixteenth century) and Caitanya (sixteenth century), all of whom followed and advocated the way of bhakti, devotion [29].

As the three principal currents of theism evolved, so each diversified and produced its own literature. The main genres, the Vaishnava Samhitas, the Shaiva Agamas and the Shakta Tantras, are primarily handbooks dealing with doctrine, yoga and meditation, temple-building and the consecration of the image of the deity in the temple, worship and festivals and the conduct expected of the adherent. At a less institutional level, bhakti was transformed from a restrained respect into a passionate and ecstatic experience by the Tamil devotional poets, the Vaishnava Alvars and the Shaiva Nayanars. These saint-poets in the south of India expressed their impassioned spirituality in hymns to Vishnu and Shiva respectively, not in Sanskrit but in Tamil, from the eighth to the tenth century. It has been said that, with them, bhakti ceased to be a way to salvation, but became salvation itself [25].

Within Vaishnavism this new attitude was reflected in the Sanskrit Bhagavata Purana (c. ninth century), which became a powerful source of inspiration for Krishna bhakti (devotion to Krishna) in the north [6]. Numerous new sects arose and many fine devotional poets used the vernacular languages such as Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati and Bengali for their verses, thus enabling millions to come into direct contact with the scriptural traditions for the first time [26]. Devotion to the other important avatara of Vishnu, Rama, found powerful expression in the Ramacaritamanasa of Tulsidas (sixteenth century), which is one of the most loved works in north India [18].

Shaivism, too, developed strongly. A distinctive school of Shaivism arose in Kashmir, certainly before the ninth century, which was much influenced by Advaita [10]. The devotional outpourings of the Nayanars of the south were incorporated into a theological system called Shaiva-siddhanta which was formulated in the twelfth century [12]. Also in the twelfth century, a movement came into being called Vira-Shaivism whose followers were called Lingayats. Vira-Shaivism, which rejected both the caste system and temple worship, exists to this day in a somewhat modified form [11; 12].

Shaktism also developed and proliferated. One aspect of Shaktism that had a strong influence on both Shaivism and Buddhism was called Tantrism. The movement was of a highly esoteric nature and had its own form of yoga, a secret language, a psychophysiological theory and characteristic modes of worship and practice designed to lead to self-realization and liberation. Although some of its practices have been much criticized, Tantrism, whose boundaries are difficult to define, is now generally thought to have added a new vitality to much of medieval Hinduism [17].

There remains one movement of major significance: the Sant tradition. The sants, themselves mainly from the lower castes, rejected the caste system and all forms of external religion, both Muslim and Hindu. They preached a form of interior religion based on constant awareness of and love for a personal God who was without attrib utes. Kabir, Raidas and Dadu, all of whom lived in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, were three of a long line of preacher-poets in whose name sects were later formed. One such sect, whose ‘founder’ was Guru Nanak, later developed into Sikhism [9; 27; and see chapter 6 below].

Thus during the Muslim period in India, and especially from the fifteenth century, Hinduism was vital and alive. Bhakti sects flourished, the vernacular languages were used, most of the population was involved at some level, and caste, however much loathed by certain groups, provided social stability and identity. In the face of this, Islam made surprisingly little headway, except perhaps to strengthen Hindu self-awareness. But it is in the modern period, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which will be considered in the final section of this chapter, that Hinduism faced its greatest self-examination as it confronted Western culture and Christianity.

Hindu Presuppositions and Belief

It will be apparent from the above examination of the inherently diverse nature of Hinduism that any attempt to produce a concise exposition of ‘basic teachings’ or ‘fundamental beliefs’ could only be misleading and partial. Beliefs and teachings there are in abundance, but few command universal acceptance. Well-articulated systems of belief, theology and philosophy are found in specific sectarian traditions or philosophical schools, most of which have their own recommended sadhana (method of practical realization) for their adherents. But these are the particulars, not the universals, of Hinduism. At the most general level there are, however, certain underlying presuppositions which together constitute a kind of received understanding, although this understanding is modified for each individual by personal, family, caste, regional and, maybe, sectarian viewpoints. The most important of these presuppositions will now be examined, together with certain other areas of Hindu concern and belief.

One of the most important and potent concepts for all Hindus is that of dharma. Dharma has various levels of meaning, but no single English equivalent. The word ‘Hinduism’, though, is often rendered in Indian languages by the term Hindu dharma, the dharma of the Hindus. Here it signifies the religion or the right way of living for Hindus. At the cosmic level dharma is sanatana dharma, the eternal dharma, which is the unchanging universal law of order which decrees that every entity in the universe should behave in accordance with the laws that apply to its own particular nature. Coming to the world of man, dharma is the source of moral law. There is, on the one hand, sadharana dharma, the general code of ethics that applies to everyone. This includes injunctions to perform meritorious acts such as going on pilgrimages, honouring Brahmans and making charitable endowments, as well as prohibitions against causing injury, lying, etc. On the other hand there is the relativist varnashrama dharma, which has already been discussed above. In fact, today, varnashrama dharma is understood as accepting and following the customs and rules of one’s caste (jati). Thus dharma means, among other things, eternal order, righteousness, religion, law and duty. The central importance of dharma has led some to state that Hinduism is a way of life, a proposition that has much, but not total, validity [28; 30; 32].

A person is a Hindu because he is born to Hindu parents, and thereby into their caste. Caste is the principal factor that determines an individual’s social and religious status. Caste is too complex a subject to discuss in any detail here, but it is underpinned by, or expresses itself by means of, the religious notion of purity and pollution which is one of the most fundamental Hindu ritual concerns [40]. Nobody can escape from pollution, since the natural functioning of the body produces sources of pollution. All human emissions, for example, are polluting: saliva, urine, perspiration, faeces, semen, menstrual flow and the afterbirth. Menstruating women, and women for a period around childbirth, are considered impure and are subject to restrictions, which vary from caste to caste, to prevent them from polluting others, especially by means of food. But perhaps the most powerful source of pollution is death. Not only are those who handle corpses heavily polluted, but a dead person’s household and certain of his relatives are also polluted by the death and have to observe various types of prohibition for varying periods. There are many ways of coping with the different types of pollution, but a particularly common one is the use of running water. A pious Hindu’s morning bathing is not simply a wash, but a ritual purification to bring him to the state of purity considered necessary in Hinduism before approaching a deity [31].

A caste is a separate, hereditary group which is normally endogamous: that is, marriage takes place usually only within the caste. A caste protects its corporate purity by restricting various types of contact with other castes it considers to be polluting, and hence impure. Thus the attribution of ‘pure’ or ‘impure’ to castes is, to some extent, relative to the status of those making the judgement. The Brahman castes, though, are always at the top of the hierarchy, being the most pure, and hence the most vulnerable to pollution. At the bottom are those castes who, for example, handle dead animals or skins, or function as menials at funerals. The middle-ranging castes in any locality rank themselves hierarchically between these two extremes. Food is a major area subject to restrictions, because it readily carries pollution. The intercaste hierarchy in any locality is clearly demonstrated in food transactions, since it quickly becomes apparent which castes or group of castes will accept or reject water, cooked food and raw food from which other castes. Physical contact used to be another sensitive area, hence the ‘untouchable’ castes, now called Harijans, but this is much less of an issue nowadays, perhaps because of legislation making untouchability illegal. The Harijan castes, however, still remain at the very bottom of the hierarchy. In a close-knit community, for example in a multi-caste village, the system results in the most minute discriminations being made in the sphere of interpersonal relations, but in the looser society of a town there is much greater relaxation. If a member breaks his caste’s purity rules, the pollution he incurs can affect the whole caste group, so the social sanctions against the offender can be severe, and he can be required to perform various ritual acts of purification before he is entitled to resume full caste rights. An individual’s ritual status is determined by the status of the caste group into which he is born [32; 40].

But caste-linked dharma is not solely concerned with whom a person may marry and with purity rules that affect interpersonal behaviour. It can also determine, for example, what work a person may do, whether meat may be eaten or alcohol drunk, or whether widows may remarry. What one caste finds acceptable another does not, so that, at this level, dharma produces a relative morality, based on conformity to custom backed by social sanctions and scriptural authority. This by no means exhausts dharma. The most intimate group to which a Hindu belongs is the family. It is mainly within the family that dharma is transmitted from one generation to another, by custom and example in the normal process of growing up, by stories and myths which are usually highly moral and contain idealized relationships and situations, and finally by scripture and precept, although this is probably the least significant in practice. The handing down of dharma to the next generation is made easier by the extended nature of the Hindu family, which results in a greater exposure to adult moral and religious influences than is usually found in Western families. The Hindu family ethic is very strong, so the structure of authority and the roles and responsibilities of different relationships are usually strictly adhered to. The Hindu life-cycle rites as well as various lineage and caste cult observances take place within the family and form an important part of its religious life. Thus the Hindu is initiated into both the specific and the generalized dharma as a natural thing from his earliest years [40].

Dharma is more than an ethical system, but, in so far as it is viewed as such, it contrasts with the moral systems of those theistic religions which posit an ethical god. Dharma is ideologically supported by other important presuppositions, the already mentioned doctrine of samsara (the endless cycle of birth and rebirth to which the soul is subject), the allied doctrine of karma, that every action produces its inevitable result so that one’s status in this life is determined by one’s conduct in a former birth, and the notions of papa (sin) and punya (merit). Actions that deviate from dharma, whether by omission or commission, are papa, sin, and increase an individual’s store of demerit. To follow dharma is meritorious, and especially meritorious are such acts as pilgrimage, making gifts to Brahmans or sponsoring a religious recitation. The merit, punya, so attained adds to one’s own store, or can be transferred to, say, a departed ancestor. Certain expiatory rites, such as bathing in the Ganges, reduce papa and hence increase the merit balance. It is the balance between sin and merit that will eventually determine, through the law of karma, how a person is born in a future life, as an insect, animal or human, and, if human, with what status. The law of karma is used by most Hindus to explain people’s present status and situation, but thoughts of future lives do not, on the whole, act as a factor in determining immediate behaviour, since the acquisition of merit through following dharma is an end in itself, being one of the four Hindu aims of life [28; 30; 32].

If there are many restrictions for a Hindu in the domain of conduct, in belief there is almost total freedom. Provided that a Hindu observes the rites and cults inherent in his dharma, he may believe what he likes. There are, however, certain metaphysical presuppositions, like samsara and karma, to which Hindus are heir, reject them or modify them as they may. (For a broad study of Indian beliefs see [3; 28; 29].) Primary among these is the concept of brahman, the impersonal absolute or world soul that underlies the phenomenal diversity of the universe and is, at once, both immanent and transcendent. Questions about God can produce the answer brahman. Other answers represent brahman in a more personal form as bhagvan or ishvara, the Lord. Those who worship Vishnu or Shiva may replace bhagvan with their chosen deity. Broadly speaking, the Hindu position, in so far as there is a single position, can be described as a mixture of pantheism and monotheism, the blend being determined by the emphasis given to the concept of brahman as World Soul or to that of bhagvan as High God.

There are certain other aspects of the Hindu approach to the divine that need to be considered. One is the principle of the ishtadeva, the chosen deity, which accepts that individuals worship their preferred deity exclusively as the supreme god. Connected with this is the inclusiveness of the Hindu approach. Other deities and beliefs are not denied or opposed, but are accepted as valid for others, although not regarded as of the same order of excellence as one’s own. Thus a devotee of Vishnu, for example, will subordinate all the other major gods, seeing them as servants or manifestations of the one supreme Vishnu. A devotee of Shiva will do likewise. While, therefore, to enumerate all the various deities worshipped in India would produce a formidable list, and perhaps be suggestive of polytheism, to do so would be misleading without taking into account the position of the individual worshipper. For the individual there is one supreme God, however conceived or named, and various other devas, gods or spiritual powers. These merit respect and perhaps worship, but are conceived of as subordinate manifestations, often with specialized functions. One author has rightly pointed out that one could spend a lifetime in India and never find a ‘polytheist’ in Western terms, because even an unlettered peasant who has just made offerings at several shrines will affirm that ‘Bhagvan ek hai’, God is one. Finally, the divine is also seen in men of great sanctity, in animals such as the cow, in certain trees, rivers and mountains, and in countless sacred sites across the subcontinent (figure 5.10).

Another concept central and essential to Hinduism is moksha (liberation), which is also one of the four Hindu aims of life. That from which liberation is sought is samsara, the cycle of birth and rebirth. The part of the human individual which is immortal – variously described and designated by different schools of thought – passes at death to diverse heavens and hells where it works out its karmic debt and is then reborn in the form it has deserved. This cycle continues endlessly unless it merits, or is blessed with, a lifetime during which, through spiritual efforts, the intervention of a guru or the grace of God, moksha is attained, whereby it passes out of the cycle altogether. Samsara is generally described as unbearable and characterized by dukkha (grief). Moksha, and how to attain it, has been a major Hindu concern for over two and a half millennia. One of the oldest methods of achieving moksha is sannyasa, renunciation, whereby the renouncer (sannyasi) abandons home, society, the world and all its bondage. Through this renunciation, and usually by performing extreme austerities and practising some form of the spiritual exercises now generally known as yoga, the sannyasi seeks to become jivanmukta, liberated while still alive. In India today there must be hundreds of thousands of sannyasis, most belonging to one or other of the ascetic orders, each of which has its own code, organization, disciplines and traditions.

If the sannyasi is one ideal Hindu type, the other is the householder (grihastha), whose major concern is living in the world, and for whom sannyasa is the final ashrama or stage of life. As has been mentioned, the Bhagavadgita describes three ways to moksha: the way of works (karma); the way of enlightenment (jnana); and the way of loving devotion (bhakti). Since works (karma) constitute a form of bondage in themselves, the renunciation necessary on this path is of the fruits of actions. Dharma should be pursued and actions performed disinterestedly, without attachment to the outcome, and this renunciation is one way to liberation. The way of jnana, enlightenment, deals with another aspect of the problem. It is avidya, wrong knowledge or perception, or maya, illusion, that prevents man from knowing what is real and what is unreal, particularly with regard to that part of himself which is immortal. Through various yoga techniques and contemplation, man attains enlightenment whereby he perceives reality, renounces unreality, and, realizing his own immortal self, thus obtains liberation. The way of loving devotion, bhakti, is preferred by the theistic traditions. Here the renunciation is the total surrender of oneself to the Lord. The way also requires constant awareness of the Lord through devotions, meditation, prayer and the repetition of his name. The theistic traditions do not, of course, consider salvation to be solely a matter of human effort. Those who believe God to be loving and full of grace await God’s grace as the means to salvation, to lift off the burden of their sins and to carry them safely across the ocean of existence, since, in the view of some, God’s grace is able to override karma.

The state that obtains when moksha is achieved has been the subject of much speculation among the various sects and schools. At one end of the spectrum of opinion is the monist Advaita position of Shankara, which holds that the immortal self of man is identical with brahman and is absorbed into brahman as the drop of water into the ocean. At the other end of the spectrum are the theists, who hold that the immortal soul of man lives in an eternal relationship with God. Thus Vishnu, Shiva and Krishna each have their own abodes, heavens, in which selves retain their identity in various states of nearness to God. Between these two extremes there is a range of intermediate positions. For sinners, though, there is the certainty of hell, whose horrific tortures, matching the seriousness of different sins, are graphically described.

Just as humanity is subject to cycles of birth and rebirth, so the universe itself is thought to go through cycles of dissolution and recreation within immense time spans. The gods responsible for this cyclicity vary with the sectarian sources in which the myth is recorded. Within these cycles are lesser periods – yugas, or ages. The present age, the Kali-yuga, is thought to last 432,000 years and to have begun in the year 3102 BCE. The characteristics of this age are a decline in righteousness, piety and human prosperity. At the end of the age the world will be destroyed again by flood and fire, although there are alternative versions of what might happen [1; 28].

The presuppositions and concerns that have just been discussed form the central elements of the received Hindu religious understanding, at least at the most general level. There are, of course, other elements, of which astrology is one important example, but the essentials have been covered. At the level of the particular, one would need to examine the nature and the mythology of the various gods, and the theology and philosophy of the different schools and sects. It is, however, within the general conceptual framework just presented that the particular systems and beliefs are articulated, and the individual Hindu derives his or her personal faith.

Hindu Practice

The concept of dharma, and how it can affect almost every aspect of a Hindu’s life, has already been discussed. One author refers to this as the ‘ritualization of daily life’, while others consider Hinduism itself to be primarily a way of life. There is another view that sees Hinduism essentially as a sadhana, a way, or ways, to self-realization and the attainment of moksha. In considering Hindu practice, therefore, one should remember that it has a far broader application than simply the performance of rites and rituals, being concerned with the practical realization of religious values at every level. That said, however, few religions have devoted so much attention to ritual as has Hinduism. From the earliest times, the ritual manuals contain details of the most astonishing complexity and elaboration [34]. Many of these works were, of course, produced for officiating Brahman priests, and absolute accuracy in performance is considered essential, since the smallest mistake invalidates the entire rite and brings retribution. It is, however, clear that the domestic rituals that the twice-born householder, in particular the Brahman, is expected to perform daily are no less complex and demanding [3].

A Brahman should perform a sequence of devotional rituals called sandhya three times a day, at dawn, at midday and in the evening. He should also worship his ishtadeva; make offerings to the devas, the seers of old and his ancestors; perform an act of charity; pay reverence to his teacher; and read from the scriptures. Some of these rituals are very elaborate. The morning sandhya includes rituals on rising, answering the calls of nature and brushing the teeth. The sequence continues with the Brahman purifying himself by bathing, purifying his place of worship, practising breath control, invoking the deity by the ritual touching of his limbs, meditating on the sun, making offerings of water and constantly uttering various prayers that he may be pure, free from his sins and strong enough to remain holy. One of the most important prayers, which may be repeated as many as 108 times, sometimes with the aid of a rosary, is called the ‘Gayatri’, a Vedic verse addressed to the sun as the Inspirer and Vivifier, and now understood as referring to the supreme God. It has been estimated that, if the enjoined rituals were performed in full, they would take at least five hours a day. Certainly there are some pious Brahmans who do in fact perform such rituals every day, but for most the daily rituals are very much abbreviated, and observance decreases proportionately as one descends the socio-ritual scale [36].

Of great importance among domestic rituals are the samskaras, or sacraments, which are the life-cycle rites that mark the major transitions of a Hindu’s life. In the early texts there were as many as forty such rites, but now fewer than ten are generally performed. Their purpose is to sanctify each transition of an individual’s life, to protect such individuals from harmful influences and to ensure blessings for them. The pre-natal rites have nowadays fallen from use and the first observances are those attending birth. These are designed primarily to contain the pollution generated by the birth and to protect the mother and child, who are considered to be particularly vulnerable to harmful influences. The exact time of birth is noted so that a horoscope may be drawn up. On the sixth day, or sometimes on the twelfth, there is the namakarana, or name-giving ceremony; the house is purified and a number of the restrictions on the mother are lifted. Some castes and families observe rites on the child’s first sight of the sun, and the first taking of solid food. More widely observed is the rite of ritual tonsure, when the child’s head is shaved. This can take place in the child’s first year or later and is often done at a temple or religious fair, sometimes as the fulfilment of a vow made by the mother to a deva in return for the deva having kept the child healthy. Another rite, that of ear-piercing, is also fairly common, although there is wide variation as to when it is performed.

The next rite, the upanayana, initiation, has great traditional importance, because it is the rite by which the three highest varnas, or classes, become ‘twice-born’ through receiving initiation into the Hindu fold. Nowadays, however, the rite is not regarded with the same importance as previously, and it appears to have become mainly the concern of the Brahman castes. At this ceremony the young man is invested with the sacred thread, janeu, which must be worn at all times and kept free from impurity. He is also initiated into the ‘Gayatri’ prayer by the presiding Brahman priest, who thereby often becomes his guru, or spiritual preceptor. In some castes a different kind of initiation takes place when, for example, a Vaishnava ascetic acts as the guru and whispers a mantra, sacred formula, to those being initiated.

The rite that signals the ritual climax of the life-cycle is vivaha, marriage. Standing midway between the impurity produced at birth and death, it represents the point of maximum ritual purity, in token of which the couple are treated as gods. It is a Hindu’s religious duty to marry. Through marriage the religious debt to the ancestors is paid off by the production of progeny. Marriage is, therefore, a sacrament of the utmost social and religious significance in Hinduism, and usually the greatest expense a Hindu incurs is that arising from having his children married. The elaborate complex of marriage rituals can take a week or more. Because of this there is great variation in practice. The actual marriage is sealed by a rite called phera during which the couple walk seven times round the sacred fire, although this is only one small part of the extremely elaborate series of social and religious rituals that constitute Hindu marriage.

The antyeshti samskara, the funeral sacrament, is the last of the rites performed. Again there is variation in practice, but the observances have a twofold purpose. The first is to enable the departing spirit (preta) to leave this world and attain the status of an ancestor (pitri) so that it does not remain as a ghost (bhuta) to trouble the living but can pass to its next destination. The second is to deal with the massive pollution that is released at death, which automatically affects certain of the deceased’s relatives. The body is cremated on a pyre lit preferably by the eldest son of the departed. Then begins a period of ten or eleven days of ritual restrictions on the relatives, at the end of which offerings of milk and balls of rice or barley (pindas) are made. These offerings, which are made at ceremonies called shraddha, usually take place between the tenth and twelfth days and thereafter annually. Their purpose is to enable the departing spirit, the preta, to acquire a new spiritual body with which it can pass on. The funeral rites should properly by performed by a son so that the deceased may best be assured of a good rebirth. It is for this reason that Hindus long above all to have a son [3; 36].

One of the major differences in the style of domestic ceremonies is whether or not they are conducted by a Brahman priest. Not all Brahmans are priests – in fact, few are; nor are all religious practitioners Brahmans. The Brahman becomes a priest first because of his ritual purity, a necessary condition for acting as an intermediary between man and God, and second because of his specialized knowledge of ritual and sacred prayers and utterances. When a priest presides the rite will be more elaborate and in accord with scriptural prescription than when a head of household officiates. Rites without a priest are not invalid, but are less prestigious. An experienced priest can perform highly complex rituals and deliver a stream of sacred utterances and instructions at great speed, but many have to resort to handbooks to guide them through the ceremonies. A Brahman priest who serves a family is called a purohita. He will serve a number of families, usually by hereditary right, in return for an annual fee. After each ritual he will be paid a sum called dakshina, but this is not thought of as a fee, rather as a meritorious gift made to a Brahman. Brahmans will normally only serve as priests to twice-born castes.

Hindu worship (puja) falls into three categories: temple worship; domestic worship; and a form of congregational worship. This last type, kirtana, mainly consists of hymn-singing, and is the characteristic mode of bhakti devotion. It has to be said that the majority of temples in India are small, although there are a significant number of large ones, especially in the various sacred centres. A temple is the home of the enshrined deity, who will have been installed by a rite of consecration in the inner sanctuary. The god’s consort may also be present, and other associated deities are often represented in different parts of the temple. Vishnu and his avataras, mainly Rama and Krishna, are usually represented by images – statues, often of considerable complexity – portraying many of the god’s mythological attributes. This is also the case with the Goddess in her various forms. Shiva, however, is usually represented by the lingam, an object (usually a black stone) shaped like the male organ, and often set in the yoni, the shaped form of a female organ; these are the universal symbols of Shaivism [35].

Temple priests called pujaris serve the deity, treating him or her either as royalty or as an honoured guest, or both. They carry out, at set times of the day, a schedule of worship and attendance which begins before dawn. The deity is awakened, bathed and fed; holds court; rests; is anointed, decorated, and finally retired for the night. This schedule is accompanied by various ceremonies such as arati (the waving of lamps), the sounding of bells, the performance of music, hymns, prayers, the offering of flowers, fruit, grain, food and incense, together with other forms of worship and supplication. On festival days connected with the deity there are often spectacular ceremonies and processions which draw people from far around. There is no requirement for any Hindu to go to a temple, although many do, and worship is private. A Hindu goes to a temple in the hope of obtaining a darshana – a sight or experience – of the deity, to make offerings, to pray to or petition the deity, or perhaps to make or fulfil a vow. Often food which has first been offered to the deity and hence has become consecrated (prasada) is available for worshippers for whom it is a much desired blessing [35].

Domestic worship takes place in most households, but rarely with the elaboration of the temple routine. In most houses there is an area set aside for worship and maintained in a state of ritual purity. Here the ishtadeva of the household is represented by an image, by some symbol of the deity concerned, even by a poster. It is usually the women of the household who attend the deity and carry out the various rituals. These can comprise arati, offerings, prayers and acts of supplication. Geometrical designs called yantras and mandalas are sometimes used as symbols for worship. These range from fairly complex mystical symbols, used mainly in Tantric rites, to simpler designs made on the ground with different-coloured powders which can be used in the worship of any deity [3].

The devotees who gather together to worship by chanting bhajanas or hymns are usually, but not necessarily, affiliated to a sect. The chanting, the music, the rhythm and the atmosphere of fervent devotion can produce a deep effect and some enter a state of trance. At these gatherings there is also sometimes an arati ceremony and the distribution of prasada. Groups who gather together in this way to worship through hymn-singing occur all over India and at most levels of society. In those parts of Assam where bhakti has become institutionalized, bhajanas are the principal mode of worship.

A different kind of communal worship is the katha, or recitation of a work of scripture. It is meritorious to sponsor such a recitation, and priests are commissioned and an audience invited. Each text normally relates in specific terms exactly what benefits will accrue to those who hear the text and to those who sponsor its performance.

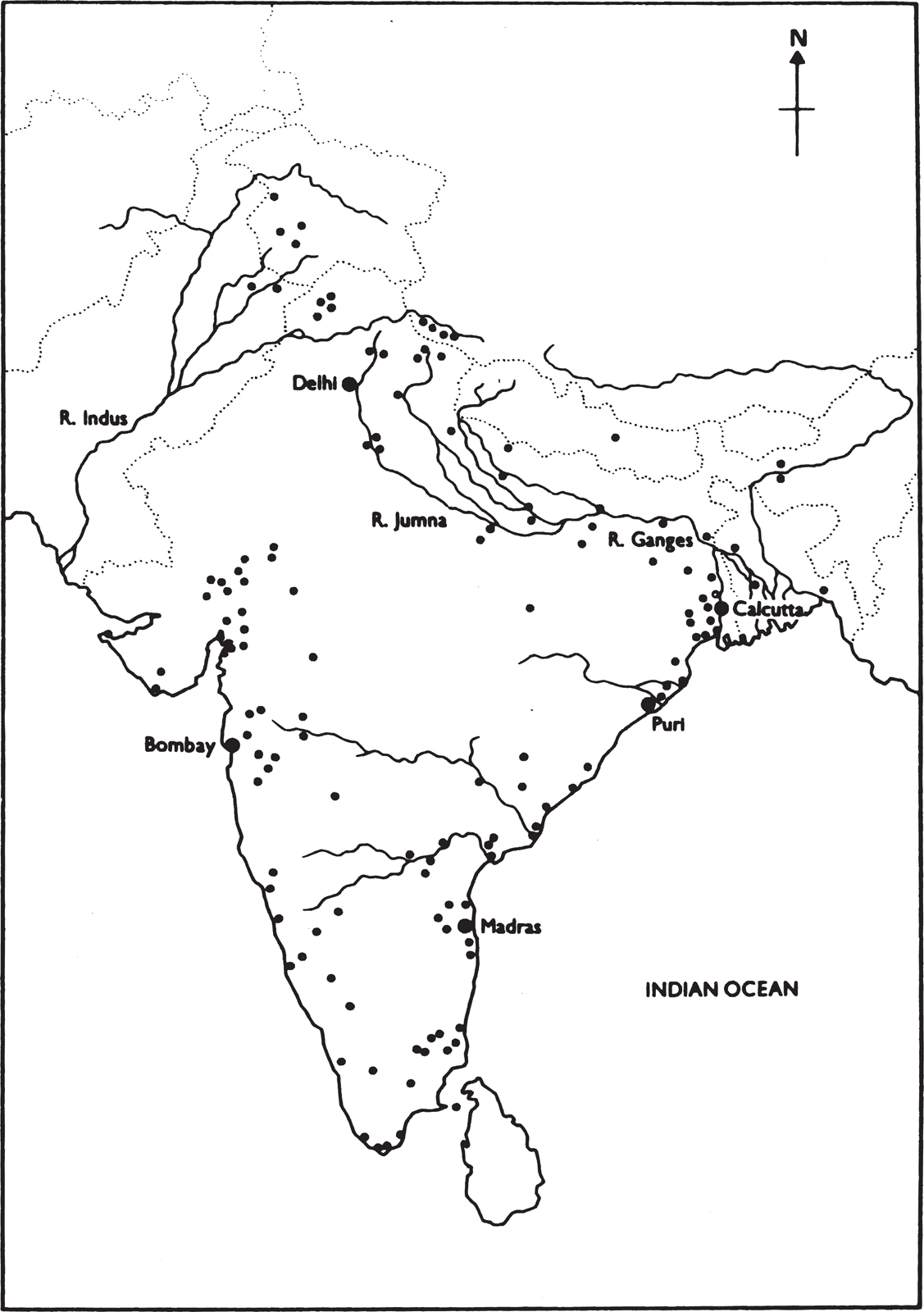

Another highly meritorious and widely practised religious act in Hinduism is pilgrimage [33]. All over India pilgrimages are taking place daily, on every scale and in every region (see figure 5.11). There are local and regional pilgrimage sites as well as all-India pilgrimage sites like Banaras and Conjeeveram. Each site has its own characteristics, its own benefits to offer the pilgrims. There are regional sites, for example, which offer help to the blind, to the childless or to those suffering from skin complaints. Banaras and Gaya are particularly concerned with salvation, the absolution of sin and the making of offerings for ancestors. Mathura and Brindavan are associated with Krishna, and hundreds of thousands of pilgrims go every year in the hope of obtaining darshana, an experience, of their Lord Krishna of whom they are devotees. Thus people undertake pilgrimages for a mixture of motives: for merit and salvation; for absolution of sins; to worship or experience the divine; to propitiate ancestors or to appease an angry deity; to obtain relief from illness or misfortune; or to ensure prosperity or some more specific blessing. The consequence of hundreds of thousands of Hindus mingling together away from their own localities is to reinforce the sanctity of the sacred geography of India to which Hinduism is so closely tied, and to continue to foster the sense of Hindu unity and self-awareness.

Pilgrimage sites are usually very well organized, with guides and priests who receive the pilgrims and then take them through the round of locations and ceremonies. There are booklets describing the various features and temples of each site, detailing their respective mythological associations, praising their merits and enumerating the benefits that accrue from each. Sometimes pilgrimages take place on particular days of the year when there is some great festival or religious ceremony at a certain site, such as the Jagannatha festival at Puri. By far the largest gatherings, which run into several million people, take place at the melas, religious fairs, which occur every twelve years at Allahabad, Hardwar, Ujjain and Nasik.

Figure 5.11 Important pilgrimage sites in India

Perhaps, however, the most colourful aspect of Hindu practice is the annual cycle of festivals [38]. Indeed, Hinduism has been described as a religion of fasts, feasts and festivals, since fasting, vigils and feasting are usually integral parts of the celebration of Hindu festivals [37]. As with pilgrimage, festivals are local, regional and all-Indian. When festival lists from villages in the same region are compared, often there are very few common to all. The number of festivals celebrated throughout India must run into thousands, but the number actually celebrated in any given locality will rarely exceed twenty, and is usually much smaller. It is not only, of course, a matter of location. Certain castes and seas have their own festivals, and devotees of a particular deity will be concerned in the main with the festivals associated with that deity.

No attempt can be made here to describe even the most notable all-India festivals in any detail, but they can be approximately located. The first month (lunar) of the Hindu religious year is Cait (April/May) which contains the New Year’s Day, the minor Navaratri, nine nights devoted to the Goddess, Ram Navami, the birthday of Ram, and Hanuman Jayanti, the birthday of Hanuman. The birthdays of two of Vishnu’s avataras, Parashuram and Narasinha, are celebrated in Besakh (April/May). Jeth (May/June) contains an important three-day fast observed by women to ensure conjugal happiness which culminates in worship to Savitri. Asarh (June/July) contains the Ratha Yatra, the chariot journey, which celebrates Krishna as Jagannath, of which the ceremonies at Puri in Orissa are renowned. The month also marks the beginning of Caturmasa, a period of four months of fasting and austerities variously celebrated. Nag Panchami, devoted to serpent deities, and Raksha Bandhan, the tying of amulets to secure brotherly protection, occur in Savan (July/August) which is particularly a month of fasting and vows. In Bhad (August/September) there is Krishna’s birthday, an important fast for women and ten days of worship for Ganesh. Kvar (September/October) contains pitri-paksha, the fortnight for the fathers, when offerings are made for three generations of the departed, as well as the major Navaratri, the nine nights of Durga-puja. In the North, Ram-lilas enact the struggles of Ram over Ravana throughout the period of Navaratri, so that both the conclusion of Durga-puja and the triumph of Ram are celebrated on the same day, Dassahra, which is a major festival. Katik (October/November) is marked by Divali, a four- or five-day festival of lights, of which the day of Divali itself is considered auspicious for all new beginnings and the start of the new financial year, and also by the end of the period of Caturmasa. Sometimes in the month of Pus (December/January) but always on 14 January, is Makara Sankranti, which marks the entry of the sun into Capricorn and is an important festival, especially in the south. The month of Magh (January/February) is important for ritual bathing and fairs. Phagun (February/March) contains two major festivals, Mahashivaratri, the Great Night of Shiva, and Holi, the boisterous spring festival.

Even with these major all-India festivals there is considerable regional variation in the manner of their celebration, in the mythology and sometimes even in the deity connected with a particular date. Although this treatment of Hindu festivals has been short and it has not been possible to include description, this should not be taken to imply that their significance is small. They bring vitality to Hindu life; they provide an annual renewal of religious values; and they are often occasions for great joy and celebration.

Many sweeping generalizations have been made about the position of women in Hinduism, but the diversity of sources and the contradictory nature of their pronouncements cannot sustain a single view. Apart from the omission of certain Sanskrit mantras from some of the life-cycle rites, and the fact that marriage is regarded as such a significant event in a woman’s life that initiation (upanayana) is not performed, there are almost no major areas of Hindu practice from which women are excluded. A woman is held to be an equal partner in dharma with her husband, and thought to share his destiny, which is why many Hindu women fast regularly for the welfare of their husbands. As the mistress of the household, ritual purity is in her charge, as are many of the household rituals. Women go on pilgrimages, sponsor kathas, visit temples, fast, and make vows and offerings. In fact, much of the living practice of Hinduism is dependent on the participation of women.

One of the ideals of Hindu womanhood is Sita, the wife of Rama, who is portrayed as ever obedient and subservient to her Lord’s wishes [4]. But although the Hindu woman is expected to show public deference to her husband, this in no way indicates the nature of their private relationship. As manager of the household, and as mother, the Hindu woman wields considerable authority. Child marriage is now illegal and the remarriage of widows lawful. The practice whereby a widow immolated herself on her husband’s funeral pyre (sati) – which was always the exception rather than the rule – has been forbidden in law for over a century. The battle to overcome prejudice against the education of girls was won in the nineteenth century. In short, there is little reason to think that the Hindu woman is at any greater disadvantage than women elsewhere in the world, as the presence of women in many leading positions in India conclusively demonstrates.

Hinduism in the Villages

Of the total Hindu population of India, over 80 per cent, that is over 500 million Hindus, live in villages. The number of villages is over 500,000. Thus the Hinduism of the villages must certainly be regarded as the religion’s most prevalent if not its most characteristic form. It is in the villages that one meets the full diversity of Hinduism. Some have regarded the religion of the villages as a ‘level’ of Hinduism, as folk or popular religion, but this is a mistake. There is no separate ‘village Hinduism’ any more than there is a separate ‘village Christianity’. The entire spectrum of Hinduism, from its most sophisticated to its most unsophisticated manifestations, can be found in the villages.

There is certainly a specific emphasis. The majority of villagers are simple, unlettered folk who struggle for their livelihood in the face of poverty, disease, climatic uncertainty and many other kinds of threats and difficulties. As is to be expected, such people are concerned not so much with the higher realms of metaphysical speculation, nor with elaborate ritualism, but rather with the practical, pragmatic side of religion. This latter aspect of religion, which seeks to attain ends in this world – a son, a good crop, recovery from illness, etc. – is as much a part of Hinduism as any other aspect, and has been since at least the time of the Atharva-veda. This is, however, only a matter of emphasis. Dispersed and localized in the villages of India, the continuing tradition of Hinduism flourishes and is still evolving in all its multiplicity and diversity [39, 41, 42].

There is no such thing as a typical Indian village. Almost every village is different from any other. This is not surprising given the great regional variations of the subcontinent, especially with regard to terrain, climate, ethnic and linguistic groupings and cultural traditions. The population of India, moreover, is not wholly Hindu. There are Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis and some Jews. Thus in religious terms, too, the population of the villages is not homogeneous. This lack of homogeneity is further increased by the segmentation of the Hindus into castes. There are single-caste and multi-caste villages. The nature and number of castes, and the strength of their representation, crucially affects the types of religious beliefs and practices found in a village, as well as determining its social structure. It is often the case in a multi-caste village that the pattern of residence reflects the caste composition, with, perhaps, each caste having its own quarter, and sometimes the Harijans occupying a separate hamlet.

The effect of having a number of different caste groups and also maybe households, sometimes hamlets, of adherents of other religions, is to produce considerable religious diversity within a single village. It may be that some of the castes are high, aspiring to Brahmanical norms in their behaviour and practices. Other castes, like the Harijans, who are denied the service of Brahman priests, have had to develop their own forms of religious expression. Not only are their customs quite different from those of the higher castes, but the deities they venerate are usually more local and tend to be more specific in their functions (like, for example, a smallpox goddess). Some castes have a traditional association with a particular deity, who functions rather like a patron saint, and in large castes which have a complex internal organization there are also clan and lineage deities. These caste cults add further diversity to the religious life of any particular village. It is because of this range and diversity that one must reject the notion of there being a special ‘village Hinduism’ [42].

The hierarchy into which the castes arrange themselves is determined at the village level. But, usually, unless there are some special factors, there will not be a marked difference between the ranking of a caste in one village and the way the same caste is ranked in the villages around, provided that the caste composition of the villages is more or less the same. The hierarchy is not, however, fixed, except that the Brahman is always at the top and the Harijan at the bottom. If a caste group does well economically and seeks to have its newly won material position ritually recognized in an enhanced position in the hierarchy, it will abandon those of its customs and religious practices which are considered ‘low’, adopting instead those of the castes above it in the hierarchy. In a generation or two it will have established itself higher up and become accepted in its new ritual status. Likewise a caste group might, for some reason, lose prestige or standing and slowly slip down in the hierarchy. Although at any one time the hierarchy seems fixed, in fact there is perceptible and constant movement when measured over decades. Low castes do not humbly accept their lowly status. There is generally much bitterness, and continual effort to improve their position [40; 42].

It used to be thought that villages were somehow self-contained units; but this is not the case and probably never has been. In the religious sphere, as in every other, villages are integrated into the locality and the region of which they form a part. There are considerable differences between the varieties of Hinduism found in the major regions of India: between, for example, Bengal, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu. Not only do these regional forms determine the religious outlook of the villagers, the location of a village within a region can also be influential. It could be situated near a major temple, the centre of a sect or an ascetic order, a place of regional pilgrimage, or some other sacred site with a long mythological pedigree. These can create sub-regional influences that again colour the beliefs and practices of the villagers in that locality. Some of the villagers might be drawn to join a sect whose centre was near by, or become disciples of a guru who had taken up residence in the vicinity. Local cults can develop around the tomb of a man who was considered to be of great holiness. Those elements of Hinduism that are considered to have an all-India spread, like certain festivals, in fact are mediated through regional and sub-regional traditions to the individual villagers. Although the names and dates may correspond, there are major differences in the rationale and significance of such festivals in different regions, and even greater differences in the significance they might hold within the total structure of each village’s sacred year [38].

It is often the case that there are several small temples in a village, perhaps Rama, Shiva or Hanuman temples, but by far the most numerous structures are the small shrines that house the grama devatas, the village deities. If the various divine beings of Hinduism were to be ranked in terms of importance or power, brahman or bhagvan, the Godhead or God, would come first, in second place would come the devas, the major gods of Hinduism, and lastly would come the grama devatas, the village deities. If the ranking is in terms of immediacy and the amount of attention received from the villagers, then the order is reversed. The reason for this is that, in the unsophisticated understanding of a substantial proportion of the village population, bhagvan, God, is too transcendent, too remote, too concerned with the cosmos to be interested in a villager’s problems. The devas too, who do bhagvan’s work at a universal level, are also thought to be too busy or too grand to be concerned with humble peasants. But the various devatas or local deities are believed to be the supernatural powers which not only affect a villager’s life and welfare, but which also demand his attention and can be extremely angry if they are not given it, with dire results for the villager.