6

Sikhism

Introduction

Name

The term ‘Sikh’ is derived from the Punjabi verb sikhna, to learn. The first Sikhs were the followers of Guru Nanak (1469–1539), who lived in the Punjab region of north-west India. At first ‘sikh’ had no more precise meaning than ‘disciple’ or ‘follower’, but with the passage of time the movement has developed into a distinct religion with its own scriptures, beliefs, practices and values. The term has now a more precise definition, though some Sikhs themselves dispute its appropriateness. The Rahit Maryada, the Sikh Code of Conduct (see below, p. 335), defines a Sikh as ‘any person who believes in God; in the ten Gurus; in the Guru Granth Sahib and other writings of the Gurus, and their teaching; in the Khalsa initiation ceremony; and who does not believe in the doctrinal system of any other religion’ [5: appendix 1]. What all Sikhs agree on is the belief that their religion is distinctive and divinely revealed; it is not a form of Hinduism.

Sources for the Study of Sikhism

The principal primary sources for the study of the Sikh religion during its formative period, the time of the Gurus from 1469 to 1708, are Sikh. In common with other religious movements which have become established independent religions it was not until later in its development that it attracted wider literary attention [27: II].

These Sikh documents fall into two categories. First, there are the scriptures, the Guru Granth Sahib and the Dasam Granth. Of these the former, also called the Adi Granth, is the better known. It consists of spiritual teachings expressed in metrical form composed by six of the ten Gurus, the first five and the ninth (see p. 317), as well as the verses of some Hindu and Muslim teachers who shared a similar religious outlook [5: III]. Though anthologies of the gurbani, as Sikhs describe the hymns, were made during the period of the second Guru and possibly in the time of the founder, Guru Nanak, the first definitive collection, the Adi Granth, was compiled only in 1603–4 under the supervision of Guru Arjan. The final recension was made in 1706 by the last Guru, Guru Gobind Singh. He included verses composed by his father, Guru Tegh Bahadur, at many places within the existing scripture, but none of his own. Two years later, on the eve of his death, he installed the Adi Granth as his successor, since which time the names Adi Granth and Guru Granth Sahib have been used synonymously and the book has become the authoritative guide and scripture of the Sikhs.

In theory the Dasam Granth, compiled some years after the death of Guru Gobind Singh by one of his disciples, Mani Singh [2: III; 22: 6–7] is also scripture, but it is rarely if ever installed as such in Sikh places of worship (gurdwaras) or studied or quoted as frequently as the Guru Granth Sahib. It is by no means certain that all its contents are authentic compositions of the Guru. Guru Gobind Singh was a scholar fluent in many languages. Persian, Sanskrit and Hindi are all employed in the Dasam Granth, although the script is gurmukhi, the one used in the Guru Granth Sahib. This makes it difficult for Sikh congregations to understand.

Some historical information is contained in the Dasam Granth but more is available in the Vars of the bard Bhai Gurdas (1551–1637). These are ballads or epic poems, epitomizing the work of the early Gurus and providing an insight into the Sikh way of life at an important stage of its development. Bhai Gurdas’s father was a cousin of the third Guru, Guru Amar Das. Guru Arjan respectfully called him ‘mamaji’, maternal uncle, and chose him to be his scribe when he was compiling the Adi Granth. His compositions, together with those of Bhai Nand Lal (1633–1713), a companion of the tenth Guru, may also be read and used as commentaries in gurdwaras [22: 7–8].

For information about the life of Guru Nanak (1469–1539) it is necessary to turn to the janam-sakhis [15; 18: II; 19]. These are hagiographic biographies, the main purpose of which may be gleaned from the following closing declaration by the compiler of the Adi Sakhis: ‘He who reads or hears this sakhi shall attain to the supreme rapture. He who hears, sings, or reads this sakhi shall find his highest desire fulfilled, for through it he shall meet Guru Baba Nanak. He who with love sings of the glory of Baba Nanak or gives ear to it shall obtain joy ineffable in all that he does in this life, and in the life to come salvation’ [17: 243]. Similar traditional accounts exist of the lives of the other Gurus.

Sikhism is a religion which possesses a strong sense of community. The Gurus frequently counselled their followers upon matters of social as well as spiritual conduct. In 1699 Guru Gobind Singh instituted the Khalsa, a Sikh order which has developed into a community within Sikhism and is entered through an initiation ceremony [5: VI]. Codes of Khalsa discipline issued during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries add to our knowledge of the concerns of the Sikh community during this period. (The Chaupa Singh Rahit-Nama, translated and edited by W. H. McLeod [16], is the most accessible.)

Short Introduction to the History of Sikhism

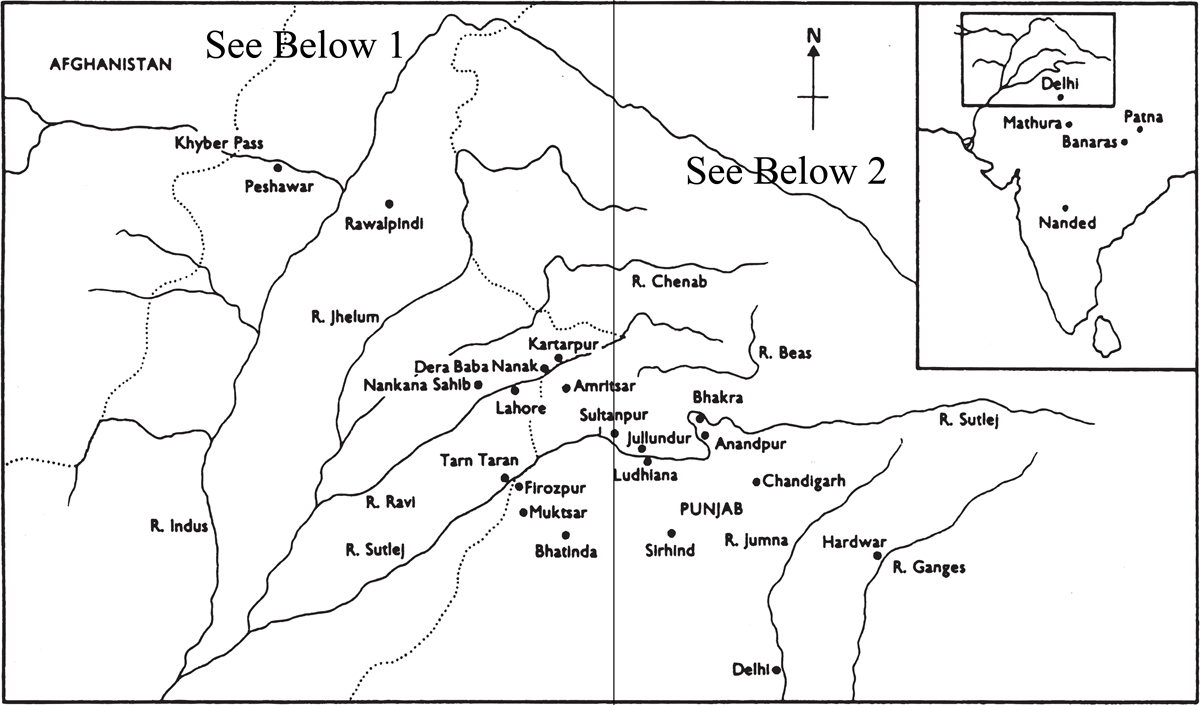

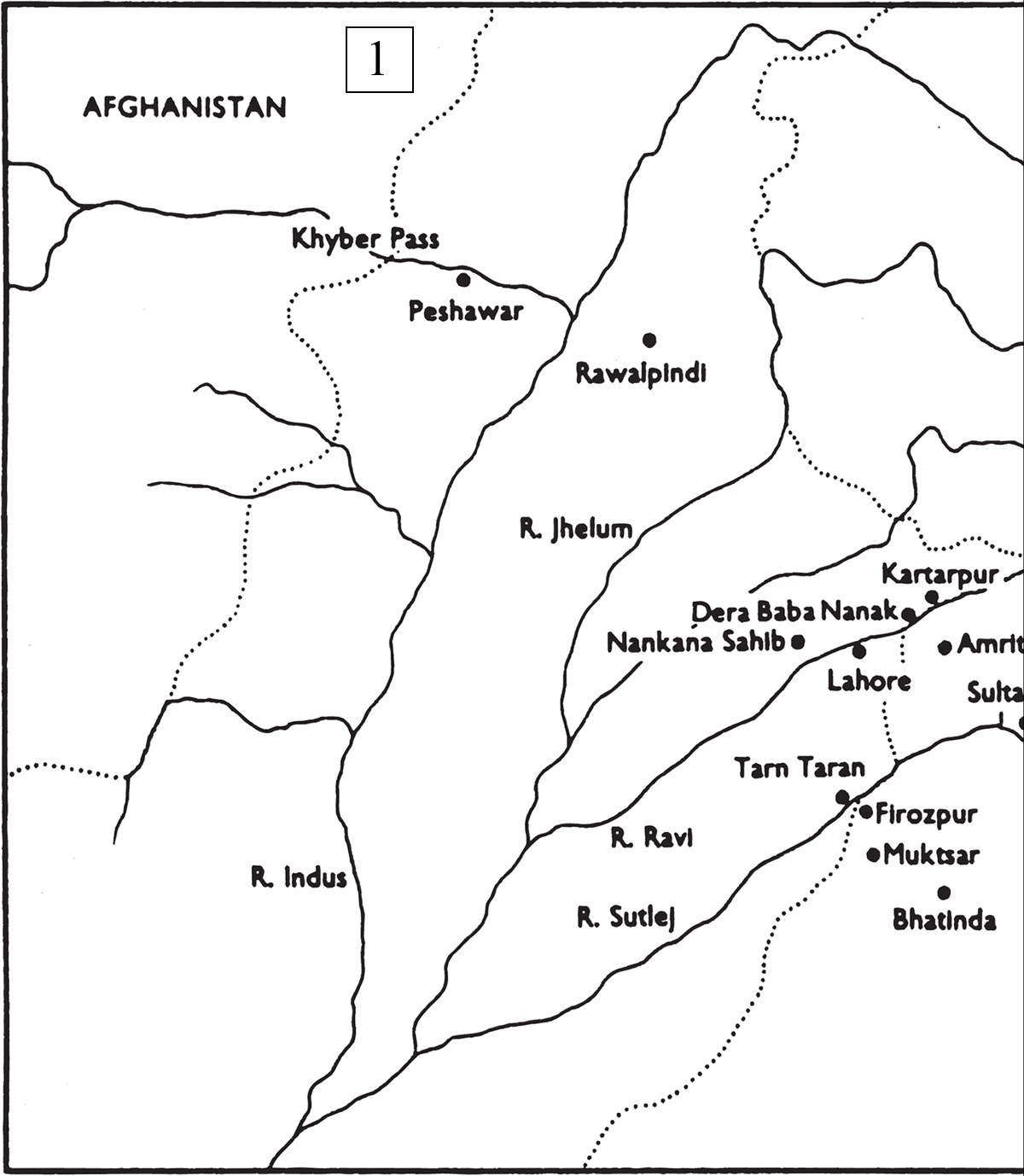

Sikhism owes its origins and early impetus to the sense of mission and dynamism of a man known reverentially as Guru Nanak. He was born on 15 April 1469 in Talwandi, now called Nanakana Sahib in his honour. This village is not far from Lahore in present day Pakistan (see figure 6.1). The janam-sakhis portray him as a precocious child who outstripped his teachers in knowledge while questioning the traditional standards and practices of piety which he encountered, both Hindu and Muslim [15: 4–9]. When he was thirty years old he underwent an experience which resulted in his becoming a religious teacher. This is described in the janam-sakhis [e.g. 15: 18–21], but the earliest account is his own, which is preserved in the Adi Granth:

I was a minstrel out of work.

I became attached to divine service.

The Almighty One commissioned me,

‘Night and day sing my praise’.

The master summoned the minstrel

To the High Court, and robed me with the clothes of honour, and singing God’s praises. Since then God’s Name has become the comfort of my life.

Those who at the Guru’s bidding feast and take their fill of the food which God gives, enjoy peace.

Your minstrel spreads your glory by singing your Word.

By praising God, Nanak has found the perfect One.

(Adi Granth, p. 150. Hereafter the abbreviation AG is used. All printed copies of the Adi Granth/Guru Granth Sahib are 1,430 pages long, so the provision of page numbers is an adequate and usual way of providing scriptural references.)

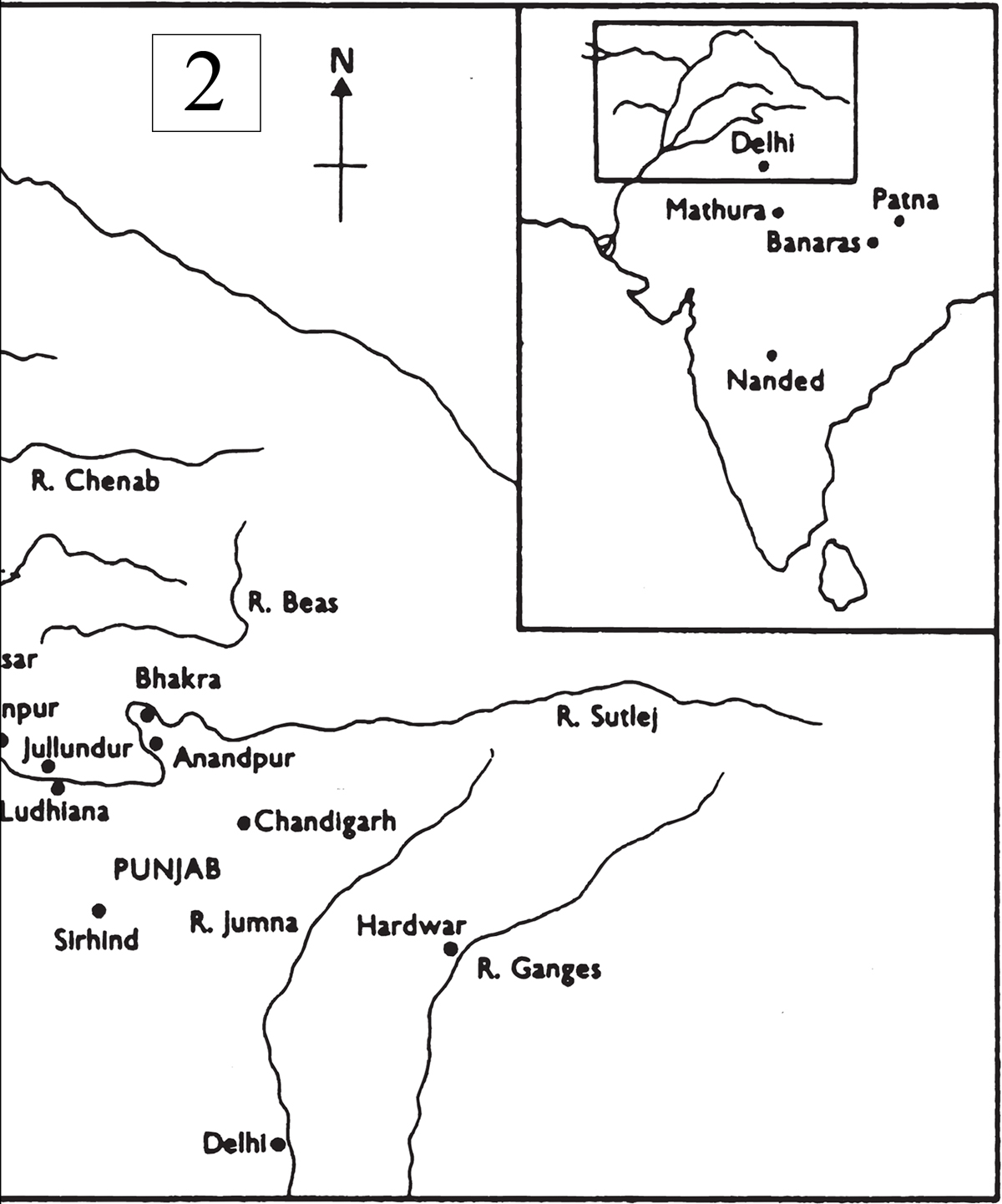

Figure 6.1 Sites in India relating to the Sikh religion

What form this experience took is not precisely known. One morning Guru Nanak took his customary bath in the river near his home in Sultanpur, where he was employed by the local Muslim governor, Daulat Khan; then he disappeared for three days, during which the river was dragged and the banks searched. When he returned to his family he remained silent for a day before making the enigmatic pronouncement: ‘There is neither Hindu nor Muslim, so whose path shall I follow? I shall follow God’s path. God is neither Hindu nor Muslim and the path I follow is God’s’ (Miharban Janam-Sakhi [19: 54]). A study of the life and teaching of Guru Nanak suggests that these words indicate that God lies beyond religious systems. Whether the Guru felt that God could also be found within them is a matter of debate. He was severely critical of the expressions of religion which he encountered, so much so that it must sometimes seem ironic that his own work eventually resulted in the development of yet another religion.

For over twenty years Guru Nanak travelled widely, encouraging women as well as men to follow ‘God’s path’. He felt inspired to establish sangats, communities of people who shared his beliefs. The janam-sakhis record visits to Tibet, Sri Lanka, Baghdad and even Makkah (Mecca) as well as to the most important religious centres of India. Then, in or shortly before 1520, he built the village of Kartarpur on the bank of the river Ravi. There he lived for the rest of his life, building his own home and also erecting a dharmsala (the early name for a gurdwara) and a hostel for visitors. His followers as householders worked tending their fields and meeting family obligations and other requirements. Bhai Gurdas described the spiritual aspect of life in Kartarpur thus:

He gave his message through his hymns to enlighten the minds of his disciples and to remove their ignorance. These were followed by religious discussions while the echoes of the mystic and blissful melodies were heard. In the evening Sodar and Arti were sung, at dawn Japji was recited. Thus the Guru’s word enabled the disciples to overthrow the burden of ancient traditions. (Var 1: 38)

The custom of using these banis daily and going to the gurdwara every morning and evening, and also the life of work and service, rather than practising renuciation, remains integral to the lifestyle of many Sikhs to this day. Guru Nanak made further journeys which were confined to India but gave most of his attention to establishing the Kartarpur community. He died on 22 September 1539.

The attractive personality and teaching of Guru Nanak, and probably his status as a Khatri, the most influential jati in Punjab, naturally won him many disciples. Their immediate needs were met by his own example, leadership and teaching. However, at some point in the development of the community Guru Nanak decided to make provision for its continuation after his death, for his work of preaching God’s message to the so-called Kal Yug was not complete.1 He groomed one of his disciples, Lehna, for leadership and eventually designated him his successor, renaming him Angad, which means ‘my limb’ [2, vol. II: 1–11]. The name was intended to convey continuity. Bhai Gurdas wrote:

During his own lifetime he [Guru Nanak] installed Bhai Lehna as his successor and confirmed his position as Guru. He passed on his light to his successor in such a manner, as if his spirit had moved from one body to another. None could understand his secret, for it was nothing short of a miracle. For Guru Nanak had spiritually transformed Guru Angad into the likeness of himself. (Var 1: 45)

This strategy ensured the safety of the message, the permanence of the Panth (the Sikh community) and, eventually, the emergence of Sikhism as a distinct religion.

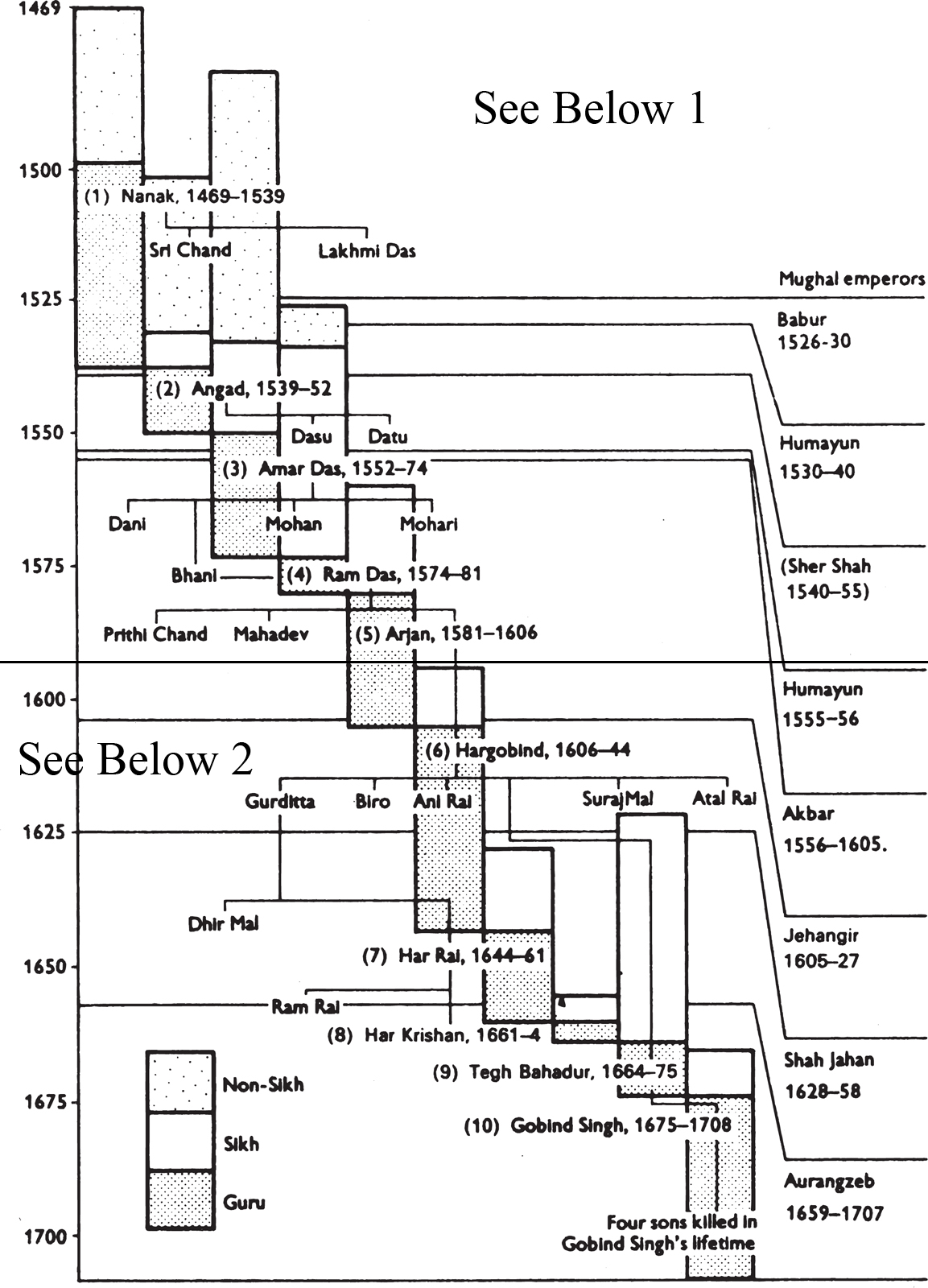

In all there were ten Gurus (see figure 6.2). They were:

- 1 Guru Nanak, who was born in 1469 and died in 1539;

- 2 Guru Angad, who was born in 1504 (Guru 1539–52);

- 3 Guru Amar Das, who was born in 1479 (Guru 1552–74);

- 4 Guru Ram Das, who was born in 1534 (Guru 1574–81);

- 5 Guru Arjan, who was born in 1563 (Guru 1581–1606);

- 6 Guru Hargobind, who was born in 1595 (Guru 1606–44);

- 7 Guru Har Rai, who was born in 1630 (Guru 1644–61);

- 8 Guru Har Krishan, who was born in 1656 (Guru 1661–4);

- 9 Guru Tegh Bahadur, who was born in 1621 (Guru 1664–75);

- 10 Guru Gobind Singh, who was born in 1666 (Guru 1675–1708).

The later Gurus All the Gurus came from the same important Khatri mercantile jati (Punjabi zat). With the fourth Guru the office came to the Sodhi family [18: V] with which it was to remain, though it was never automatically handed down from father to son. Sikhism considers each of the Gurus to be of equal standing with all the others. Two Sikh bards expressed this belief in the following words: ‘The divine light is the same, the life form is the same. The king has merely changed his body’ (AG 966). The concept is also expressed by the use of the word Mahala followed by the appropriate number instead of a personal name when assigning a passage in the Guru Granth Sahib to its author. The formula Mahala I denotes Guru Nanak; Mahala V is Guru Arjan. Sometimes this is abbreviated to MI or MV, or even simply I or V. One of the later Gurus as well as Guru Nanak may end a verse with the phrase ‘Nanak says’. Occasionally the same idea is conveyed by calling Guru Amar Das, for example, the third Nanak [15: 3].

Some Gurus played a more important part than others in the development of the Panth [5: II; 18: III]. Guru Angad’s task was to consolidate the Panth which he did by writing down Guru Nanak’s hymns in a script developed by himself or his predecessor. Now called gurmukhi, literally ‘from the mouth of the Guru’, it has become the script of written Punjabi. He may also have encouraged the compilation of the first janam-sakhi. This would provide scattered congregations, known as sangats, with an example to follow, instruction to study, and a collection of material for use in worship. Guru Amar Das established himself in the village of Goindwal on the river Beas. He summoned Sikhs to assemble in his presence three times a year, at Vaisakhi, Magha Shivatri and Divali [14: II, 79] in order to wean them away from Hindu practices associated with these festivals. He also divided the Sikhs into twenty-two districts known as manjis, each supervised by a masand, and used women missionaries especially for work among Muslim women. The fourth Guru began the building of Amritsar, then called Ramdaspur. It now lies on the Grand Trunk Road between Kabul and Calcutta but was then some miles to the north of it. His reason for choosing the site may have been related to its association with Guru Nanak, but he encouraged merchants and businessmen to establish themselves there, so it may be assumed that his motives combined commerce and piety. The brevity of his leadership, however, prevents scholars from adducing his purpose with certainty.

Guru Arjan, his younger son, built other towns in the region at Taran Taran, Sri Hargobindpur, named after his son, and Kartarpur (not to be confused with the village associated with Guru Nanak). He also made Amritsar into a religious centre, building a place of worship there called Harimandir Sahib, also known today as the Golden Temple, and authorizing the compilation of the Adi Granth which he formally installed in it, prostrating himself in front of it and thus acknowledging the message of the gurbani to be more important than the human messenger.

During the reign of the Emperor Akbar (1556–1605) the Sikh Panth prospered and enjoyed good relations with the state. Indeed, it may have been the interest that he showed in the movement (as well as other expressions of religious feeling) which encouraged the Sikhs to hope that they might be the reconciling agent between Islam and Hinduism for which Akbar seemed to be searching. In 1595, on the birth of his son, whom he named Hargobind (‘world lord’), Guru Arjan composed the following words, which may have a significance beyond the natural expression of pleasure in the birth of a first child after a long period of childlessness during which his elder brother had been conspiring to contest the succession:

The True Guru has sent the child. The long awaited child has been born by destiny. When he came and began to live in the womb his mother’s heart was filled with gladness. The son, the world-lord’s child, Gobind, is born. The one decreed by God has entered the world. Sorrow has departed, joy has replaced it. In their joy Sikhs sing God’s Word. (AG 396)

Within two years of the installation of the Adi Granth in the Harimandir Sahib, Akbar had been succeeded by Jehangir, and the Guru had been imprisoned on suspicion of being implicated in a move to support Khusrau, the emperor’s rival, and had died in captivity, providing the Sikhs with their first martyr. This dramatic change in fortune has affected the Panth to the present day. Guru Arjan’s martyrdom is never forgotten. No matter how prosperous and hopeful the times may be which Sikhs are currently enjoying, there is a belief that a renewal of persecution is inevitable.

Guru Hargobind armed himself in obedience to his dying father’s instructions. He lived and ruled as a temporal as well as spiritual leader, keeping court and enjoying hunting while remaining the Sikh Guru, though unlike his predecessors he did not compose religious verses. Doubtless there was some shift in focus from the living Guru to the Adi Granth during his lifetime. Hargobind’s relations with the Emperor Jehangir were somewhat ambivalent: they hunted together, yet Jehangir also imprisoned him in Gwalior fort. At Divali Sikhs celebrate the Guru’s release, along with that of fifty-two rajahs which he also secured, and his return to Amritsar. Sikhs associate with Hargobind the doctrine of miri and piri, that of wielding two swords, one of temporal justice, the other of spiritual authority.

The seventh and eighth Gurus did not make outstanding contributions to the Panth’s development. With the ninth Guru, respectively their uncle and grand-uncle, leadership seems to have reverted to a more traditional form in the person of Guru Hargobind’s surviving son, Guru Tegh Bahadur, now forty-three years old. A devout poet as well as a man of strong character, he succeeded to the gaddi, or seat of authority, at a time when Emperor Aurangzeb was introducing his policy of Islamization which included closing Hindu schools (1672) and demolishing temples, which were sometimes replaced by mosques. In 1679 the poll tax (jizya) imposed on non-Muslim subjects was reintroduced. Guru Tegh Bahadur was among the opponents of the emperor’s policy. In 1675 he was executed in Delhi and is revered by Sikhs as a martyr who died not only for the Sikh faith but also for the principles of religious liberty.

The tenth Guru, his son, also experienced fluctuating relationships with the Mughals. His importance for the development of Sikhism lies in two decisive acts. In 1699 at the Vaisakhi assembly at Anandpur he founded the Khalsa [5: VI; 18: I]. ‘Khalsa’ may be translated as ‘pure’, but the land which is the personal property of a sovereign is also called khalsa. The term therefore denotes a community of the Guru’s own people. The masands (see above, p. 319) had often set themselves up in rivalry to the Gurus; this was a way of renewing sole allegiance to the Guru after destroying their power. Those who responded to the Guru’s call for obedience received initiation through a ceremony known as Khande ka amrit or Amrit Pahul (sometimes the single word amrit is used). A mixture of sugar and water was stirred with a two-edged sword (a khanda) while a number of hymns were recited. Those initiated took certain vows and adopted five ‘Ks’ – five symbols which in Punjabi begin with the letter K. They are kes (unshorn hair), kangha (comb), kirpan (sword), kara (steel wristlet) and kachch (short trousers), often worn as an undergarment. To these male, and some female, members of the Khalsa add the turban worn by the Gurus. The result was the distinctive appearance which has marked the Sikh ever since. Male Khalsa replaced their sub-caste or family (got) name by Singh and women used the name Kaur. The theoretical significance of these names, meaning ‘lion’ and ‘princess’, is the elimination of caste identity which got names reveal, and the raising of everyone to the status of Kshatriya (warrior class). The Guru, formerly Guru Gobind Rai, now became known as Guru Gobind Singh. The creation of the Khalsa was a device for sanctioning the use of disciplined force under the Guru’s personal control. Guru Hargobind had kept a small standing army, and irregular forces had existed under the masands [19, vol. I: v]. Now allegiance was to the Guru alone, who would only call upon them to fight in a dharam yudh, a struggle on behalf of justice and in defence of religious liberty [3: 63]. Sikhs regard this restrained use of force as the final development in a policy against injustice which had begun with Guru Nanak [e.g. 19: 44], who is sometimes described as being a pacifist: there seems to be no evidence for this view.

The last Guru’s final act was to install the Adi Granth as his successor. Since then it has been called the Guru Granth Sahib, though the name Adi Granth is still used almost as a synonym. This decision was intended to prevent succession disputes, as his four sons had all predeceased him, but it also indicates that he considered that the mission begun by Guru Nanak was now ready to be developed in a different way. He had always taught that the Khalsa was his alter ego. Now he affirmed that belief by placing authority in the scripture and the community.

Later Sikh history The year 1708 marks the end of what might be called the canonical period of Sikhism. The scripture, the Khalsa and the tradition were now in place. Many Sikhs would deny that any further significant developments in these have taken place since. This is not completely correct. The stress upon the Khalsa form and ideal, of which students of the Sikh religion and uninitiated members of the Sikh Panth are very much aware today, belongs to the period of resurgence initiated by the Singh Sabha movement (see below).

The eighteenth century witnessed bitter struggles between Sikhs, Mughals and Afghans, which ended only when Maharaja Ranjit Singh [14, vol. I: X, XI] captured Lahore in 1799 and subsequently established an independent state; this lasted until 1849, when his son Maharaja Dalip Singh surrendered it and the Koh-i-noor diamond to the British.

Several other events in Sikh history must be mentioned if present-day Sikhism is to be understood fully. First, in the nineteenth century, the influential Singh Sabha movement emerged (2: 138–41; 22: 14–15), partly in response to successful Christian evangelism among young educated men in Punjab, but even more to the activities of the Arya Samaj (see p. 304). In 1877 Dayananda Saraswati came to Punjab and a branch of the Arya Samaj was opened in Lahore. His movement was well received by Sikhs until they realized that he held their Gurus in low esteem. Sikhs responded by increasing their support for a Singh Sabha (Sikh Society) which had been founded in Amritsar in 1873 to counter Christian missions, and to extend its work to Lahore and other cities. Its main function was to revive Sikhism through literary and educational activities, especially the founding of Khalsa colleges. This recovery also took the form of political agitation, leading to the Anand Marriage Act (1909), which gave legal recognition to the Sikh wedding ceremony, as well as emphasis upon Khalsa identity. With the Gurdwaras Act (1925) the protracted struggle to regain control of gurdwaras which had often passed into the ownership or custody of Hindus during the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh finally came to a successful conclusion.

Two other developments are of such magnitude as to deserve separate sections to themselves. They are the dispersion of Sikhs throughout the world, and the rise of the movement for an independent Sikh state.

Sikh Migration and the Diaspora

Sikhs never tire of saying that Neil Armstrong’s pride at being the first man on the moon was severely dented when a taxi drew up and its Sikh driver asked him, ‘Where to, sir?’

Migration is one of the most important aspects of Sikhism in the last 150 years and especially the latter half of the twentieth century. Only now is it really receiving the academic attention it deserves [1].

The movement of some Sikhs within India pre-dated overseas migration. This is fairly remarkable if we bear two things in mind. First, Sikhs were fighting for their survival during much of the eighteenth century until Maharaja Ranjit Singh established an independent Sikh state in 1801. There was nevertheless an established Khatri tradition of trading beyond Punjab. Secondly, cultural diversity might have been inhibiting. Among Hindus even a brahmin Sikh might have been suspected of being slack in observance of purity rules. Linguistic difficulties may have been slight. Even today many Sikhs speak Hindi and older ones have Urdu as well. The armies of Bombay and Madras did not recruit Sikhs before 1857, but that of the Calcutta Presidency did when the Anglo-Sikh wars ended in 1849 [39: 172]. The result of such recruitment would be the dispersal of some of the soldiers to a region at least 2,000 km from their homeland. Awareness of this migration might make the world-wide phenomenon of the Sikh diaspora more explicable.

An important date for Sikh migration beyond India was 1857, the year of the first independence struggle, known to British historians as the Mutiny. Sikhs stood aside from the uprising because they had no wish to reinstate the Mughals or any other Muslim rulers, and that seemed to them the likely consequence of its success. This won favour with the British, who began recruiting Sikhs into their army. By 1870 Sikh soldiers were serving overseas. There were also Sikh members of police forces in such British colonies as Hong Kong and Malaya. During the First World War they fought in Europe as well as Africa.

Sikh civilians were also migrating, perhaps individually but also in groups, by the end of the century. Kessinger notes that twenty men left Vilyatpur for Australia in the 1890s and that this had risen to about thirty-five by 1903, perhaps a third of the village’s menfolk [12: 90, 92; 1: 32–3]. Sikhs were especially prominent in the development of East Africa in the 1890s, helping to build the railways. They were Ramgarhias for the most part, a group mainly of tarkhans (carpenters), but including some smiths (lohars), masons and bricklayers (raj), who have become a distinct Sikh zat which takes its name from Jassa Singh, a Sikh army commander of the eighteenth century who built the Ramgarh fort in Amritsar.

In 1902 Sikh soldiers from Hong Kong went to Canada to take part in celebrations marking the coronation of Edward VII. They eventually returned as settlers working in British Columbia’s lumber mills. Sikhs were also to be found in California before the outbreak of the First World War. Most Sikhs migrated to America after the Second World War and claims are sometimes made that they now number more than a million there. The Canadian census of 1991 gives the country’s Sikh population as 147,000. It is said that in 1985 there were forty-seven gurdwaras in the US and eighty-five in Canada. The number of gurdwaras does not, of course, necessarily indicate the size of Sikh population; but it provides some guide to population distribution, for a Sikh community will establish a gurdwara as soon as it can, following the tradition established in Guru Nanak’s day and in keeping with its nature as a religion in which assembling together for worship is essential.

Migration to the United Kingdom The first known Sikh to arrive in Britain was Maharajah Dalip Singh, son of Ranjit Singh, the last ruler of the Sikh empire. When this was annexed by the British in 1849 its eleven-year-old ruler was placed in the custody of Sir John Login of the Bengal army, in whose care he converted to Christianity. Five years later he came to England, was received by Queen Victoria and bought an estate in Elvedon, Suffolk. As time passed he became increasingly dissatisfied with his treatment and attempted to return to India where he intended to be readmitted to the Sikh faith. He was stopped at Aden and returned to Europe, but not until he had taken amrit. In 1893 he died in Paris and was buried in the churchyard near his Suffolk estate. Dalip Singh and Ram Singh, builder of the Indian rooms in Queen Victoria’s Osborne House, were among a very few but, in their cases, notable nineteenth-century Sikh visitors to Britain.

In 1911 the first gurdwara in Britain was established in Putney with financial support from the Maharajah of Patiala; others appeared only after the Second World War. Until then, Britain was apparently too far away; also, it must be remembered, Britain was at this time still an exporter of labour and the first immigration legislation had just been passed to curb the influx of Jews fleeing east European pogroms. Sikhs have never willingly migrated into inhospitable areas. Sikh eyes were still on the Pacific region which had already been pioneered, to which travel may have been easier and where work prospects were good.

Sikh and other Indian traders did, however, come to Britain between the two world wars. Many of them were pedlars belonging to the Bhatra zat. They would arrive at a port, set up base in rented rooms, buy small domestic items and go from door to door with their immense cases. Women might buy some goods on credit and provide the salesman with a regular if hard-earned living. Other Sikhs might work in the open-air markets. These were not settlers. Their families remained in Punjab and the men returned to them when they had made enough money to go back to their villages with pride (izzat) and the financial means to give them some prosperity. Their success encouraged others to take their chance.

Real settlement in Britain began in the late 1950s with a largescale movement of economic migrants from Punjab, especially the Hoshiarpur district of the Jullundur doab, the area between the rivers Beas and Sutlej. They were augmented later by families from East African countries which, having gained their independence, pursued policies of Africanization. In the 1990s the British Sikh population stands at about 400,000, two-thirds of whom were born in Britain. (The UK does not include a religious question in censuses, so no accurate statistics exist. [See 13: 13.]) This is probably the largest Sikh population outside India. Britain’s Sikhs chose to go to the UK because they were British; they had British passports. Some were war veterans who had served in Europe, others learned that there was plenty of work to be had, sometimes through newspaper advertisements. They went to the traditional industrial areas and parts of London. Not many went to Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland, where there was still unemployment, or to the coal-mining areas of south Yorkshire or the north-east, where the industry was fully manned. In brief, in common with all economic migrants through the centuries, they went where they were needed, not where they would compete with the existing labour force. They had little intention of staying permanently in the UK, but legislation during the 1960s confronted them with the choice of either bringing their families to join them or eventually leaving Britain. The vast majority decided to stay and sent for their immediate relatives. They still maintain close ties with India, sending money to improve the family home or to build gurdwaras, dispensaries or schools. Their children, now grown up and themselves parents, may visit Punjab less frequently, and declare themselves to be British Sikhs, though experience of racial discrimination and harassment make them uneasy about their status and future, and events in India since 1984 have reminded them that Punjab is the Sikh homeland.

Migration to North America Sikhs who migrated to the US, Canada and Australia in the second half of the twentieth century differed from most of those who went to Britain in that they were often well qualified and quickly found their way into white-collar employment.

Sikhism is not a religion which looks for converts, but a feature of the American diaspora is the large number of ‘white’ (gora) Sikhs. In January 1969 an Indian sant, Harbhajan Singh Puri (Yogi Bhajan, to give him his popular name), began teaching kundalini yoga in the US. Some of his students were attracted by his lifestyle, which included vegetarianism as well as the usual amrit-dhari discipline of the initiated Khalsa Sikh, daily nam simran, the prohibition of alcohol, tobacco, drugs and sex outside marriage, as well as by his Sikh world-view stressing equality and service. In November 1969 the first converts took amrit. Some doubts were expressed by Punjabi Sikhs when they saw gora Sikhs for the first time, dressed from head to foot in white Punjabi clothes and wearing turbans, including children as well as men and women. They have, however, turned out to be not hippies in transit from one fad to another but serious Sikhs. Their children have been brought up in the Sikh way; some have even been educated at Sikh schools in India. The movement is sometimes known as 3HO, Healthy Happy Holy, and by the end of 1975 had 110 centres and 250,000 people involved in its activities [24]. Its preferred title is Sikh Dharma of the Western Hemisphere; it is also known as the Sikh Dharma Brotherhood. A declared aim of the sant and his followers is to revive Sikh commitment to Khalsa ideals in Western countries where they have often become neglected. These converts could have an important role to play, together with other diaspora Sikhs, in enabling the Panth to distinguish universal Sikh values from those which are Punjabi.

Cultural changes among Sikhs in the diaspora Distinction between religion and culture tends to be a Western division unfamiliar and incomprehensible to many people of the East. There are, however, second- and third-generation settlers in the West who are beginning to compartmentalize religious belief and practice and secular life, at least to the extent of separating their understanding of the essence of Sikhism from a Punjabi/Indian lifestyle in respect of diet, dress, arranged marriages and language. Their neglect of these latter elements cuts them off from their spiritual heritage in the form of worship in the sangat and ability to understand the Guru Granth Sahib, as well as from converse with family elders who are often custodians of the tradition at the popular level, transmitting it to their grandchildren. Some Sikhs who perceive this trend as a danger respond by reinforcing Punjabi culture, particularly in retaining Punjabi as the language of the gurdwara and continuing to encourage arranged marriages. Usually, these are now more assisted than arranged, with young people having some say in the choice of partner. The practice of bringing in a bride or groom from India is becoming less frequent not so much because of legal hurdles but because of an awareness of changes in lifestyle among Western Sikhs. The prospect of a partner from Punjab reinforcing parental values may be seen to pose a threat to the bride or groom who was born in the diaspora. This is not to say that arranged marriages in themselves are proving unacceptable. On the contrary, many young Sikhs appreciate the stability they can bring and recognize their advisability in a system where one is marrying into an extended family.

Changes in religious practice Sikhs possess a strong sense of community. The Gurus spoke frequently of the sangat, the fellowship of believers which was essential for spiritual and moral development. Guru Ram Das said: ‘Just as the castor oil plant imbibes the scent of the nearby sandal wood, so wrong doers become emancipated through the company of the faithful’ (AG 861). In Punjab, however, this does not necessarily mean regular congregational worship of the kind found every Sunday in countries where it is a holiday. Sikhs have no weekly holy day. They should go regularly to the gurdwara and remember God in paying their respects to the Guru Granth Sahib, but much of their daily prayer takes place in the home, meditating every morning and evening upon specified compositions found in the scripture. It is at gurpurbs (anniversaries of the birth or death of one of the Gurus) or at the festivals of Vaisakhi or Divali or more regular occasions such as sangrand, the first day of the month, when Sikhs are likely to gather as a religious community.

In the diaspora the gurdwara has become the focus of Sikh life. Rooms in private houses were used by the first settlers; now, warehouses, redundant churches or former schools have been converted into gurdwaras and many purpose-built ones have been constructed. Weddings, held in the open or under marquees in India, usually take place in gurdwaras at weekends. The formal educational role of the gurdwara exceeds even its importance as a social centre where the elderly gather often for much of the day. For the young, Punjabi classes, training in playing the musical instruments used in worship, formal education in religion, all things unnecessary in Punjab, are essential functions of many diaspora gurdwaras.

The establishment of caste gurdwaras has occurred in some countries. One can only speculate upon reasons for this. One may be the settlement of several groups in an area whereas in India a village might have only one zat. Affluence and numbers might provide further explanations. The existence of sufficient Ramgarhia or Jat Sikhs in a town makes the financing of separate gurdwaras feasible.

Sants, spiritual teachers, have an important role in Sikhism where, in the absence of a regular professional ministry, the only practical authority is the Guru Granth Sahib. They provide personal leadership and may become the focus of devotion, though they take care not to be seen as in any way rivalling the scripture’s authority or being regarded as gurus in the Hindu sense of the word. In India a Sikh will go to a sant’s dhera or encampment which is the equivalent of a Hindu ashram. In the diaspora, sant gurdwaras have taken root. Some sants now spend much of their time travelling the world ministering to the needs of their devotees. They often teach their own particular interpretation of Sikhism, perhaps the importance of taking amrit initiation, of holding regular continuous readings of the Guru Granth Sahib known as akhand paths, or of being vegetarian; or they may have a healing ministry.

Culture clashes in the diaspora All male Sikhs are expected to wear the turban. For those who have been initiated it is essential, as is the kirpan, the sword often worn as a sheath-knife about twelve centimetres long. Some migrant Sikhs made the error of cutting their hair and abandoning the turban when they arrived from India, being assured by Sikhs already there that they would not find employment otherwise. On the contrary, in fact, sometimes the turban-wearing Sikh had been highly respected by those alongside whom he had fought in Italy or Asia, and discarding this mark lost him the identity to which respect was attached. Colour, not race, was the real bar to employment and accommodation. Sikhs gradually became more confident and often, discovering that the initial advice had been unsound, readopted the turban and uncut hair. Some schools, transport authorities and other employers refused to recognize the right of Sikhs to wear the turban, but these disputes were normally resolved quickly. After all, Sikhs had worn turbans in the British army. The first clash with national authority in Britain occurred in 1972 when Parliament legislated that crash helmets should be worn by motor-cyclists. In 1976 Parliament passed the Motor-Cycle Crash Helmets (Religious Exemption) Act ‘to exempt turban-wearing followers of the Sikh religion from the requirement to wear a crash helmet when riding a motor-cycle’. Since then the right to wear the turban has been generally accepted in all areas of British life. It is worn instead of a wig, for example, by a High Court judge and, in accordance with an exemption granted in the Employment Act of 1989, instead of a hard-hat on construction sites. There have also been disputes in Canada and the US relating to the right of Sikhs to wear turbans.

The Sikh kirpan is recognized as having a ceremonial and defensive purpose and to be an essential part of Sikh dress. Sikh responsibility has ensured that few people have questioned the right of Sikhs to wear it. A few years ago the British government signalled its intention of bringing in legislation to ban the carrying of knives. The Home Office assured Sikhs and Scots that their right to wear, respectively, the kirpan and the skean dhu would be safeguarded. Less newsworthy has been a development relating to the use of Sikh names. It took some years for application forms to change ‘Christian name’ to ‘forename’ or ‘given name’ but even longer for some employers, especially the British Nursing Council, to accept that a Sikh woman’s surname should be ‘Kaur’ even though her father’s name ‘Singh’ appeared on her birth certificate.

Khalistan

This is the name of a concept and aspiration which some Sikhs hope will be realized in the establishment of an independent Sikh country based on the historical and geographical Punjab, not the present small north-west Indian state of that name. The idea goes back beyond the partition of India in 1947. In 1945 the Shromani Akali Dal, a Sikh political party, put forward the Azad Kashmir scheme when it became clear that the British government accepted the principle of partition. This province would remain within the India Union [32: 9, 10]. Negotiations with Jinnah for predominantly Sikh areas of Punjab to be incorporated in Pakistan came to nothing when Muslims attacked Sikhs [32: 33].

Sikhs now express their view of these events tersely in the sentence: ‘The Muslims got Pakistan, the Hindus got India, what did the Sikhs get?’ Faced with the choice of belonging to India or Pakistan, Sikhs say, they chose India because Nehru offered them virtual autonomy whereas Jinnah had offered a religious freedom which he could not guarantee. That promise, however, has never become a reality. The federal India which Nehru and Gandhi envisaged, as well as Ambedkhar who drafted its constitution, has never matched their ideal. It was to have been a secular nation in the Indian sense of one in which all religions enjoyed equal respect and none was privileged. To protect the secular ideal against his great fear of communalism, Nehru deferred granting Sikh demands for a Punjab state defined along linguistic lines, a quite proper request within the constitution. In 1966, as a reward to Sikhs for their loyalty during the 1965 Indo-Pakistani war, his daughter Indira Gandhi, by then prime minister, granted it in the form of the Punjabi Suba. This, however, did not satisfy the aspirations of those who wanted a Sikh state, albeit within the Union, so opposition continued.

Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale was the man the Congress Party hoped to use to embarrass the dominant Sikh Akali Dal. He proved to be beyond manipulation, however, and was eventually destroyed in June 1984 by an Indian army assault upon the Golden Temple complex which he had been openly fortifying for at least six months. On 31 October Mrs Gandhi was assassinated by Sikh members of her bodyguard, and in Delhi and elsewhere Sikhs were attacked; many were killed. Rajiv Gandhi, who replaced his mother as premier, attempted to solve the Punjab crisis by drawing up the Punjab Accord with a Sikh leader, Sant Harchand Singh Longawal, in July 1985; but he lacked the personal authority to implement the agreement.

The Punjab crisis remains unresolved. Most Sikhs recognize that their future lies within the Indian Union, but in a modified federation in which central authority is curbed and cannot be imposed upon the regions. A growing number of Sikhs, however, do not believe that an Indian government will ever have the will to relinquish central power and the patrimony which goes with it. At present the militants seem to have been checked in Punjab, though they are still active. Outside India, the Washington-based Council of Khalistan, under its President, Dr Gurmit Singh Aulakh, seeks to influence the US and other governments and draw attention through such organizations as Amnesty International and the United Nations to what they describe as the continued repression of the Sikh nation. In 1991 the Bharatiya Janata Party won many seats in India’s general election on the basis of a clear religious appeal to Hindus to make India a Hindu nation. Sikhs are fearful of the rise of Hindu militancy for two reasons. If the Hindus tell them that they are really Hindus, as the nationalist Vishnu Hindu Parishad, for example, claims, calling them ‘Keshadhari Hindus’, their distinctive identity, which involves far more than an attachment to uncut hair, is threatened. If churches and mosques are attacked, Sikhs fear that gurdwaras will be the next chosen targets. Some Sikhs have moved to Punjab from other parts of India anxious to avoid this danger. Occasional Sikh attacks on Hindus in Punjab should be seen in the context of creating a an exclusively Sikh state de facto, if the Hindu government, as they see it, will not grant them one de jure.

The solution to the Punjab problem may lie in a radical redrafting of the Indian constitution to produce a federation which gives more regional autonomy.

Teachings

The most distinctive concept of Sikhism is its doctrine of guru-ship. The Srimat Bhagavata (11.3.21) advises the spiritual seeker who wishes to achieve liberation to ‘find proper instruction at the feet of a guru who is well versed in the Vedas that lead to a knowledge of God’.2 The first known gurus, or spiritual preceptors, in the Indian tradition were imparters of Vedic knowledge and many of them were Brahmans. There is, however, another parallel tradition in India, that of spiritual teachers whose authority lay not in their membership of the brahman varna or in the Vedas but in a personal awareness of enlightenment and belief that they had been commissioned directly by God. Often they saw their responsibilities as being to guide to liberation anyone, man or woman, regardless of caste, who approached them. Such a teacher was Guru Nanak; but the Sikh concept of guru-ship is far richer than that of merely believing in an enlightened teacher. God, Akal Purakh, the Timeless Being, is beyond human comprehension and can only be known by gracious self-revelation. The form of that revelation is as Adi Guru, or Primal Guru, often named as ‘Sat Guru’ (True Preceptor) which becomes the Word (shabad) or gurshabad, the message of enlightenment. The ten human Gurus of Sikhism were emphatic that God was the Guru and that any importance they might have had was as faithful messengers through whom the Word was revealed. Here they were taking hold of an ancient Indian idea of shabad as sound, the sound associated with brahman. What they believed was that this sound was the manifestation of brahman which became articulate and coherent in the words which they uttered. Thus the terms which are used for the verses in which the teaching is enshrined, shabad or bani, are often prefixed by the syllable gur to give expression to this view (gurbani, gurshabad). When the tenth Guru installed the Adi Granth as Guru (whence its alternative name Guru Granth Sahib), he was doing no more than reaffirming the original doctrine that guru-ship belonged to the divine author and that the message was received from God rather than from the person conveying it. Sikhs attempt to make this point firmly in gurdwaras, where pictures of the human Gurus should never be located in such a position that Sikhs bowing in front of the Guru Granth Sahib may be perceived to be sharing that honour with them. No Sikh should ever bow towards the portrait of one of the Gurus.

This is not the end of the story of guru-ship. When Guru Gobind Singh created the Khalsa in 1699 he was initiated as its sixth member and recognized its guru-ship. During the eighteenth century guru-ship seems to have been shared between the community and the scripture, being complete when the Khalsa gathered in the presence of the Guru Granth Sahib. Such assemblies were eventually terminated, and awareness of the guru-ship of the Khalsa became more a memory than a present, practical reality. In the late twentieth century, at a popular level, guru-ship is sited in the ten Gurus and the scripture. Though that of God is acknowledged and explored by theologians, that of the community has been neglected, though some scholars are now beginning once more to turn their attention to it, and attempts have been made to revive the Sarbat Khalsa, a decision-making assembly of the Panth.

Western scholars frequently associate Guru Nanak with the north Indian Sant tradition [19: 151–8; 23: IV, s. 3]. The unifying core of Sant belief was, first, that God is nirguna (unconditioned, without qualities) rather than saguna (manifested, possessing qualities and form, usually as a divine incarnation (avatara, see p. 271)). God is therefore beyond the categories of male and female, though personal in the sense that all the sants were aware of entering into a personal relationship with the divine based upon grace. Secondly, Sant belief stressed that God is one without a second, the only ultimate reality. The Sant tradition was uncompromisingly monotheistic and was often critical of the polytheism which it saw in many aspects of Hinduism. From these ideas, realized through personal experience, other teachings were derived. Avataras were rejected; so was the efficacy of ritual acts, pilgrimages and asceticism, as well as the concept of ritual purity and pollution. The ministrations of Brahmans were considered unnecessary and the authority of the Vedas was implicitly denied. Varna and jati were thought to be illusory distinctions as, ultimately, were sexual differentiations. Sant teachings were open to Brahmans and untouchables, women as well as men, so spiritual liberation was open to everyone.

‘Sant tradition’ is, however, a convenient way of referring to a group of teachers and mystics united by a similarity of ideas, though not by any proven historical connection. Some of those who are assigned to the Sant group, such as Namdev (1270–1350), Ravidas (fifteenth century) and Kabir (d. 1518), are often described as disciples of Ramanand (c. 1360–1470), but this must be seen as no more than an attempt to provide them all with a Brahman guru, to offset smarta criticisms of unorthodoxy in the seventeenth century. A so-called sixteenth-century smarta reaction to the many bhakti teachers of north India was led by brahmins who emphasized traditional authority based upon the the Vedas (shruti) and smirti (the Bhagavadgita, the Laws of Manu and other texts). The smartas seem to have had no influence upon the Sikh Panth, though some heterodox groups responded to them. Guru Nanak explicitly rejected the authority of the Vedas and their Brahman interpreters. His successors endorsed this view. Many Sant views are to be found within Sikhism, but more coherently expressed and more fully developed in the life of the Panth than by members of the Sant tradition.

The relationship between Guru Nanak and Kabir has often excited the interest of Western scholars. One janam-sakhi, the Hindaliya, asserted that Guru Nanak was Kabir’s disciple, but this was written by a disaffected former Sikh and is clearly an attempt to discredit the Sikh tradition and establish his own leadership [19: 23 n. 2]. The relation of Guru Nanak to Kabir, as of Kabir to the sants, is to be explained by an affinity of ideas. Guru Nanak was not Kabir’s disciple [5: 41].

There has been no brahmanizing of the Sikh tradition. The principles and precepts taught by Guru Nanak remain intact. God, Akal Purakh, is beyond the categories of male and female, though scholars are fond of using male personal pronouns when writing about the divine being. God is saguna as well as nirguna [5: 75], a personal God, the divine Guru and inner teacher. Whoever, through grace, becomes aware of the inner activity of the immanent God as Guru, and responds to that voice by living in obedience to God’s command (hukam), attains spiritual liberation while in the body. The effects of karma must still be worked out but no more will be accumulated (see p. 284). At death the soul (atman or jot) will live in the divine presence, never to be reincarnated. Effort cannot induce this revelation of God as immanent – it is a sovereign act of God’s will; but Sikhs do believe that effort demonstrates earnestness of intention. Without it there would be no basis for the moral conduct which Sikhs consider important. However, there is a popular saying, ‘Take one step towards God and God will take a hundred towards you.’

Once having received grace, truthful living, making an effort to serve humanity, becomes an imperative. Inner spiritual experience is developed by meditation until a person’s whole being is God-permeated. The name given to the discipline which brings this about is nam simran [5: V], calling to mind God’s name and thereby becoming so immersed in the divine unity that the illusion of duality is overcome.

Corporate worship as well as individual meditation is a means of achieving God-realization. The bard Bhai Gurdas wrote: ‘One is a Sikh, two is a sangat [community or congregation], where five are God is present’ (Var 13, 19). This line accurately reflects the teaching of Sikhism about the importance of the congregation. Guru Nanak himself said: ‘The company of those who cherish the True One within them turns mortals into holy people’ (AG 228). The emphasis which is placed upon becoming God-oriented (gurmukh) instead of self-centred and self-reliant (manmukh), which is a person’s natural state, does not require the Sikh to turn to asceticism; on the contrary, domestic life, engagement in commerce, farming and industry, in fact any work which is honest and especially that which is beneficial to society, is to be pursued. In serving one’s fellow human beings one serves God. At the same time the Sikh should live uncontaminated by the five evils of lust, covetousness, attachment, wrath and pride, like a lotus in a pond. The duties of a Sikh have been summed up in three phrases: nam japna, kirt karna, vand chakna – keeping God continually in mind, earning a living by honest means and giving to charity. Seva, service, not only to fellow Sikhs but to anyone, is not only a highly praised virtue, it might be said to be as essential a part of spiritual development as nam simran.

The ideals and teachings of Sikhism are such that it may be said that the varnashrama dharma of Hinduism (see p. 269) is reduced to one lifestyle in an ethical monotheism fully open to women and men alike, living as a householder (grihastha).

These words of Bhai Gurdas may sum up the Sikh ideal better than any others:

At dawn a Sikh wakes up and practises meditation, charity and purity.

A Sikh is soft-spoken, humble, benevolent, and grateful to anyone who asks for help.

A Sikh sleeps little, eats little, and speaks little, and adopts the Guru’s teachings.

A Sikh makes a living through honest work, and gives in charity; though respected a Sikh should remain humble.

Joining the congregation morning and evening to participate in singing hymns, the mind should be linked to the gurbani and the Sikh should feel grateful to the Guru.

A Sikh’s spontaneous devotion should be self-less for it is inspired by the sheer love of the Guru. (Var 28, 15)

Guru Nanak sanctified the way of life to which most peasants had no alternative, and at the same time provided the villagers of north India and beyond with an alternative to Islam. The egalitarian monotheism of Islam must have been attractive to those classes of Hindu society which, according to Brahmanical teaching, had no hope of attaining moksha (see p. 285) in this present round of existence. In a Punjab under Muslim rule, Islam may also have offered the hope of social improvement. Not surprisingly, there were many conversions to Islam in that region. If the development of bhakti, devotion, may be seen as the response of Hinduism to this threat, so the work of Guru Nanak might be regarded as a carefully conceived, broadly based movement providing an indigenous alternative to Islam. The Guru Granth Sahib contains not only the bani of the Sikh Gurus, but also many compositions by Muslims such as Sheikh Farid, Hindus such as the Brahmans Ramanand and Jai Dev, Pipa, the Rajput prince, low-caste men, for example Namdev, a tailor or calico printer, and outcastes, Ravidas, the cobbler, and Sadhna, a butcher, as well as Kabir the weaver, whose family had become Muslim, perhaps to improve their status, but who refused to class himself as either Hindu or Muslim. Their inclusion is seen by Sikhs as making the important theological statement that truth knows no sectarian limits. As Guru Nanak said, God is neither Hindu nor Muslim. It would be wrong, therefore, to describe Sikhism as theologically syncretistic, a pick-and-mix combining the best of Hinduism and Islam, a view which neglects to address the question of what criteria should be used to determine the ‘best’, fails to comprehend the uncompromising nature of Islam, and ignores many of the tenets of Sikh teaching outlined above.

Religious Practices

Although Sikhs may claim that the practices described below may be traced to the Gurus, in fact many became neglected or corrupted by Hindu influence between the period 1708 and the emergence of the Singh Sabha movement in the late nineteenth century which, among other achievements, did much to purify Sikh practices. Their response was eventually codified in the form of the Rahit Maryada (sometimes the spelling Rehat Maryada is used). [It can be found in 5: appendix 1; 22: 79–86].

The focal point of religious life and worship is the Guru Granth Sahib. Sikh worship is essentially congregational and takes place in its presence. Selections from the compositions which it contains should be sung by the sangat led by musicians (ragis). Readings and talks (kathas) are also the responsibility of the congregation. There are no priests; Sikhism rejects the whole of Vedic sacrificial practice. Its ministers (granthis) may be trained and paid, but in theory anyone may be one. The term really means one who is competent to read the Guru Granth Sahib.

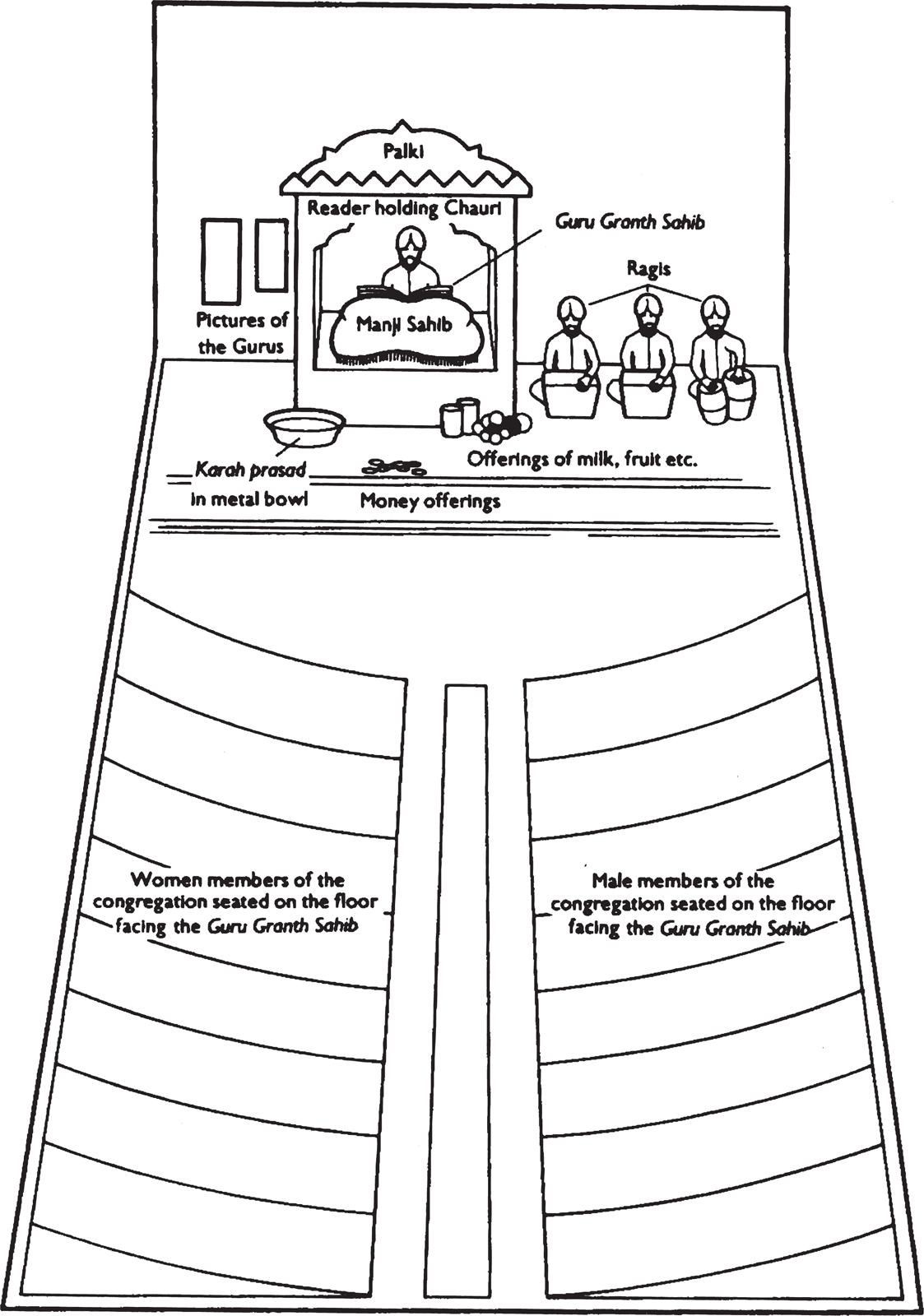

The place where these acts of worship are held is called a gurdwara – literally the door (dwara) or abode of the Guru (see figure 6.3). In fact this name may be applied to a room in a private house as well as a place of public worship owned by the community, providing it contains a copy of the scripture. A family possessing a Guru Granth Sahib should consult, it, that is read from it, every day, and will probably do so in the evening. A feeling of not being able to care for it adequately may be one of the reasons why not all families have their own copy. On special domestic occasions they will borrow one from the gurdwara; meanwhile, for regular use, they will read from and meditate upon selected passages in a gutka or nitnem. Various names are used for such anthologies.

Public worship (diwan) may take place on any day. As already noted, Sikhs observe no weekly holy day, but as ekadeshi, the eleventh day of a lunar month, is important to Vaishnavite Hindus (see p. 271), and sangrand too (the day when the sun moves from one sign of the zodiac to another) is a day of customary significance in northern India, special gurdwara services are often held on these days. Puran-mashi, the evening of the full moon, is also kept in the same way by some Sikhs. According to one widely accepted tradition, Guru Nanak was born at that time.

Sikhs may visit the gurdwara at any time convenient to them to make an offering, listen to the words of the Guru Granth Sahib, receive karah prasad (sacramental food) and take langar (common food and drink) in the community kitchen. At the Golden Temple, daily worship begins before dawn and continues well into the night, and many major gurdwaras conduct worship from five or six in the morning until about eight in the evening. Overseas, some gurdwaras open only at the weekend when people can be present to attend the scripture and conduct services. The aim, however, is to make the gurdwara available every day and all day.

Figure 6.3 Plan of a typical gurdwara

There are times when the Adi Granth is read from beginning to end without a break (akhand paths). These occasions include gurpurbs, anniversaries of the birth or death of one of the Gurus, when the reading is held as a public, communal activity. These are Sikhism’s only distinctive festivals: its others – Vaisakhi, Divali, and Hola Mohalla – can be traced to Hindu roots, though each has a distinctive meaning for Sikhs. Sometimes families will organize such continuous readings as an act of piety before a wedding or at the opening of new business premises. Akhand paths are carefully timed to last about forty-eight hours and normally to end in the early morning. As the Guru Granth Sahib is 1,430 pages long in the printed form now universally used, families cannot always organize akhand paths; instead, a normal reading (sidharan path) may be arranged. This will take place over a period of one or two weeks, family and friends assembling daily, usually after work, to participate in the spiritual exercise.

The scripture is also used when a child is named and at a wedding [37: 106–9; 2: 53–6, 59–64]. At the naming of a child someone should open the Guru Granth Sahib at random and read out the first word of the first hymn on the left-hand page. The first letter of the word should provide the initial letter of the name. When a couple have agreed to marry one another the marriage ceremony consists of circumambulating the scripture in a clockwise direction four times while the four verses of the wedding hymn (lavan), composed by Guru Ram Das, are sung. Consent and marriage in the presence of the Guru Granth Sahib is all that is required to legitimize a marriage in Sikh eyes. Funerals consist of readings from the scripture [37: 109–10; 2: 66–9], but bodies should not be taken into the presence of the holy book. In Indian villages, of course, cremations usually take place in the open, though large towns now have crematoria.

At some point in most services two features will occur which conclude the act of worship. The first is the saying of a formal prayer (ardas) [5, appendix 2; 22: 103–5] spoken by a member of the congregation facing the Guru Granth Sahib; the second is the sharing of karah prasad. This is a warm pudding of gram flour (semolina), water, sugar and ghee (melted butter), which is distributed to everyone who is present. It symbolizes equality and the rejection of caste restrictions, frequent bars to commensality in Hindu society.

The distinctive Sikh rite of initiation [5: VI; 37: 112–17], amritpahul or khande ka amrit, is also centred upon the Guru Granth Sahib, in the presence of which it must take place. It is the reenactment of the ceremony which was held in 1699 when the Khalsa was founded. Five Khalsa members, wearing the distinctive insignia of the Five Ks (kes, uncut hair; kangha, comb; kara, wristlet; kirpan, sword; and kachch, shorts [5: V; 2: 31–6]) and, in the case of men, the turban, dissolve sugar crystals in water with a khanda, a short double-edged sword, while they chant prescribed hymns from the Adi Granth and some verses composed by the tenth Guru. The nectar (amrit) is then administered to the eyes and hair of the male or female initiate, who is then given some of it to drink. They then take certain vows, including the promise to practice nam simran, meditation on the Gurus’ hymns, daily, and to wear the Five Ks, and then repeat the words of the Mul Mantra, a terse statement of faith composed by Guru Nanak. A paraphrase of it reads: ‘There is One Supreme eternal reality; the true one; immanent in all beings; sustainer of all things; creator of all things; immanent in creation; without fear or enmity; not subject to time; beyond birth and death; self-manifesting; known by the Guru’s grace.’ In the Mul Mantra the Guru is God-manifest.

Sikhism has never succeeded in separating itself completely from its Hindu milieu. In fact, most Hindus would regard Sikhs as heterodox Hindus. As a minority faith existing in the midst of such a great tradition, not to mention the strong presence of Islam, it may seem remarkable that the Sikhism has survived at all. That it has done so must be in no small part due to the centrality of the Guru Granth Sahib as a basis of belief and focus of practice, and to the development of a fierce pride in the Sikh heritage. In practice, however, Sikhs have never entirely freed themselves from the influence of caste [18: V], especially, for example, in marriages. The theoretical equality of women is no more a complete reality than in other societies boasting the same egalitarian ideology. The Hindu concept of pollution has not yet been fully eradicated from Sikh life, despite the teachings of the Gurus. This can be seen from the use of akhand paths to purify a building and the reasons which some Sikhs give for being vegetarian. The experience of the eighteenth century, the martyrdom of two Gurus, and the recent memory of Muslim–Sikh tensions before and during the partition of India at the end of the Raj still affect relations between the two religions, although the emphasis of Sikhism is upon tolerance and coexistence based upon mutual respect and its attitude to other faiths is pluralist. It has no difficulty in accepting that all ethical monotheistic religions come from God [4: XII].

Notes

1 Kal Yug is the fourth Hindu kalpa or age, characterized by spiritual and moral decline. It encompasses the present time.

2 The Srimat Bhagavata is one of the Puranas, a Hindu text of perhaps the tenth century CE. It is divided into twelve books, with a total of 18,000 stanzas; the quotation is from book 11, chapter 3, verse 21.

Bibliography

1 BARRIER, N. G., and DUSENBERY, V. A. (eds), The Sikh Diaspora, New Delhi, Chanakya Publications, 1988 (the first detailed study of Sikhs world-wide)

2 COLE, W. O., Teach Yourself Sikhism, London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1994

3 COLE, W. O., and SAMBHI, P. S., A Popular Dictionary of Sikhism, London, Curzon Press; Glenn Dale, Riverdale, 1990

4 COLE, W. O., and SAMBHI, P. S., Sikhism and Christianity, London, Macmillan, 1993

5 COLE, W. O., and SAMBHI, P. S., The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, 2nd edn, Brighton, Sussex Academic Press, 1995

6 GREWAL, J. S., Guru Nanak in History, Chandigarh, Punjab University, 1969

7 GREWAL, J. S., The Sikhs of the Punjab, New Cambridge History of India, vol II. 3, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990

8 HAWLEY, J. S., and MANN, G. S. (eds), Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America, Albany, State University of New York Press, 1993 (examines some of the issues raised by studying Sikhism in a Western university)

9 KAPUR, R. A., Sikh Separatism, Delhi, Vikas, 1987

10 KAUR, M., The Golden Temple, Past and Present, Amritsar, Guru Nanak Dev University, 1983

11 KAUR SINGH, N-G., The Feminine Principle in the Sikh Vision of the Transcendent, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993

12 KESSINGER, T., Viliyatpur, 1848–1968, Berkeley/Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1974

13 KNOTT, K, Sikh Bulletin, no. 4, 1987 (available from West Sussex Institute of Higher Education, College Lane, Chichester PO19 4PE)

14 MACAULIFFE, M. A., The Sikh Religion, 6 vols, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1909; repr. Delhi, Chand, 1970 (a faithful and comprehensive account of the Sikh tradition covering the period of the Gurus, 1469–1708)

15 MCLEOD, W. H., The B40 Janam-sakhi, Amritsar, Guru Nanak Dev University, 1980

16 MCLEOD, W. H. (tr. and ed), Chaupa Singh Rahit-Nama, University of Otago Press, 1987

17 MCLEOD, W. H. The Early Sikh Tradition, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1980

18 MCLEOD, W. H., The Evolution of the Sikh Community, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1976; Indian edn Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1975

19 MCLEOD, W. H., Guru Nanak and the Sikh Religion, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1968; Indian edn Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1976

20 MCLEOD, W. H., Popular Sikh Art, Delhi, Oxford University Press (India), 1991

21 MCLEOD, W. H., The Sikhs: History, Religion and Society, New York, Columbia University Press, 1989

22 MCLEOD, W. H., Sources for the Study of Sikhism, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1984; Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1990

23 MCLEOD, W. H., Who is a Sikh?, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1989

24 MANSUKHANI, Spokesman, Baisakhi number, no. 4, 1976

25 O’CONNELL, J. T., ISRAEL, M., and OXTOBY, W. (eds), Sikh History and Religion in the Twentieth Century, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1988

26 SHERGILL, N. S., International Directory of Gurdwaras and Sikh Organisations, privately published, 1985; available from Virdee Brothers, 102 The Green, Southall, Middlesex, UB2 4BQ, UK

27 SINGH, DARSHAN, Western Perspective on the Sikh Religion, New Delhi, Sehgal, 1991

28 SINGH, GOPAL, A History of the Sikh People, 1489–1988, New Delhi, World Book Centre, 1979; rev edn 1988

29 SINGH, H. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Patiala, Punjabi University; vol. 1, 1992; vols 2–5 forthcoming

30 SINGH, SIR JOGINDRA, Sikh Ceremonies, Chandigarh, Religious Book Society, 1968; first publ. Bombay, International Book House, 1941

31 SINGH, KHUSHWANT, A History of the Sikhs, 2 vols, 1963; rev edn Delhi, Oxford University Press (India), 1991

32 SINGH, KIRPAL, The Partition of the Punjab, Patiala, Punjabi University, 1972

33 SINGH, N., The Sikh Moral Tradition, New Delhi, Manohar, 1990

34 SINGH, P. Gurdwaras, New Delhi, Himalayan Books, 1992

35 SINGH, SHER, Philosophy of Sikhism, Lahore, Sikh University Press, 1944

36 SINGH, TARAN (ed.), Guru Nanak and Indian Religious Thought, Patiala, Punjabi University, 1970

37 SINGH, TEJA, Sikhism: Its Ideals and Institutions, London/New York, Orient Longmans, 1938; new edn Bombay, 1951; repr. several times

38 TATLA, D. S., and NESBITT, E., Sikhs in Britain: Annotated Bibliography, rev. edn, Ethnic Relations Unit, University of Warwick, 1994 (an essential publication for anyone studying Sikhs in the UK)

39 YADAV, Punjab History Conference, 1966

Translations of the Guru Granth Sahib

These tend to be written in sixteenth-century English or metrical poetry, apart from passages included in [14] above, an incomplete but substantial anthology still widely used which has the additional value of including considerable extracts from the Dasam Granth not easily available elsewhere.

Complete translations of the Adi Granth are:

Sri Guru Granth Sahib, ed. Gopal Singh: New Delhi, World Book Centre, 1962

Sri Guru Granth Sahib, ed. Manmohan Singh: Amritsar, Shromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1969

Sri Guru Granth Sahib, ed. Gurbachan Singh Talib: Patiala, Punjabi University, 1990

Other Sikh texts

A compendium of many of the most frequently used and important Sikh texts is [22] above.

Kaur Singh, Nikky-Guninder, The Name of my Beloved, Verses of the Sikh Gurus, London, HarperCollins, Sacred Literature Series, 1996 is a modern English translation of important banis from the scriptures, published as part of the Sacred Literature Series sponsored by the International Sacred Literature Trust.

Dr Jarnail Singh of Canada has completed a French translation of the Guru Granth Sahib, privately published, 1996; available from 70, Cairnside Crescent, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 3M8, Canada.