16

Baha’ism

Introduction

Among the new religious movements clamouring for attention in the modern West, Baha’ism (the Baha’i faith) stands out as something of an anomaly in being both sufficiently independent to be regarded as a religion in its own right and yet small enough to be treated as a sect or church in the sociological sense.

The movement originated in the 1860s as a faction within Babism (founder: the Bab, 1819–50), a messianic sect of Shi’a Islam (see p. 208 above) that began in Iraq and Iran in 1844. The founder of Baha’ism, Baha’ Allah (1817–92), claimed to be a new prophet and expounded his religion as the latest in a long line of divine revelations. Had it remained confined to the Middle East, it is likely that Baha’ism would have joined the ranks of the numerous heterodox Islamic sects there, with most of which it shares common features. But in 1894 the movement became one of the first missionizing Eastern religions to reach the West, arriving in the United States while still in a state of flux after its emergence from Shi’a Islam.

Unlike the Ahmadiyya and some recent Sufi groups that have sought converts in Europe and America, the Baha’is had consciously broken their connection with Islam and were in search of a means of defining their identity as a community based on a separate revelation, something which had proved difficult in Islamic countries but which they found possible in more pluralist societies. The original move to North America was the initiative of a single individual, but the moment was perfect, and early successes among fringe-group adherents encouraged the Baha’i leadership to divert considerable energies to the promulgation of Baha’ism in the West as a ‘new world faith’ destined to supersede all established religions.

This development was given considerable impetus by the Western preaching journeys of ‘Abd al-Baha’ (1844–1921), Baha’ Allah’s son and successor. The head of the movement from 1921, Shoghi Effendi (1897–1957), accelerated this process of Westernization, and by the time of his death in 1957 the religion had changed its character enormously.

Although the Baha’i conversion rate in Europe and North America has been severely limited and is likely to remain so, since the 1960s the movement has had remarkable success in establishing itself as a vigorous contender in the mission fields of Africa, India, parts of South America and the Pacific, thus outstripping other new religions in the extent of diffusion, if not in numbers. With a worldwide membership of perhaps 4 million and an international spread recently described as second only to that of Christianity, the place of Baha’ism among world religions now seems assured.

The most important Baha’i community is probably still that of Iran, where adherents constitute the largest religious minority. The history of Baha’ism in Iran has been chequered, however, with periodic bouts of persecution and a continuing pattern of discrimination. The community has never succeeded in winning official recognition, and since 1979 Iranian Baha’is have been under threat from the Islamic regime: over 200 have been killed, many have been imprisoned and property has been confiscated [27].

The outsider seeking a relatively unbiased approach to Baha’ism is faced with ambiguity. In terms of numbers, influence, social position, voluntariness of membership and so on, it is most usefully treated as a sect or denomination (with major regional fluctuations), rather than as a wholly independent tradition. But Baha’is themselves emphasize other criteria, such as the lives of the movement’s founders and saints, the richness of its scriptural literature, the breadth and rapidity of its geographical expansion, and the ontological assumption of a divine revelation subsequent to and abrogatory of Islam.

The informed observer must try as far as possible to shift between these and other approaches. Perhaps the central focus of interest lies in the conscious promulgation of an alternative religion, not primarily as an outgrowth of an existing major tradition, but as a new tradition in potentia and, increasingly, in reality. In its earliest phases, Baha’ism experienced the normal processes of small-scale religious development and, ìn terms of internal routinization, high participation, and zeal to convert and to confirm new adherents, it has continued to do so. But the use of aggressive, centrally planned missionary tactics since the late 1930s has made it possible increasingly to transform theological assumptions about status into empirical realities or (which may be as significant) into assumptions in the minds of the public, moulded by careful presentation of data. What we are witnessing, in other words, is the planned construction of a ‘world religion’ according to objectives derived from external theories about what actually constitutes such a phenomenon.

Sources

The question of sources for Baha’i history and doctrine is a vexed and complicated one, in spite of the comparative modernity of the movement. In the case of historical materials in particular there has been sharp controversy since the late nineteenth century, and, if anything, this seems to be increasing. There are several reasons for this. The first is that, almost from the inception of the religion, Baha’is themselves have been deeply concerned with historical issues, and numerous general ‘official’ histories have been written, including some either penned or vetted by leaders of the movement [e.g. 3; 23; 32; 42]. Valuable as they are, these and other works by adherents are normally tendentious. Independent scholars since E. G. Browne (d. 1926), have criticized this central tradition of Baha’i historiography, but until recently limited access to primary source materials and lack of scholarly interest have restricted the production of alternative versions.

A second problem is that Baha’i history is characterized from the very beginning by factionalism, some of it severe. With the exception of the Azali Babis in Iran and the small grouping of Orthodox Baha’is in the United States, alternative or sectarian groupings have tended to fade out. At the same time, idealizing tendencies in what is now the mainstream of the movement have played down or concealed the historical significance of earlier disputes and the personalities associated with them. Useful factional literature is scarce, while many crucial documents remain in private hands or are kept in official archives to which the researcher has little or no access.

Nevertheless, ample primary materials do exist and, in recent years, many of these have been used as the basis for radical reinterpretations of Baha’i and, in particular, Babi history. Many important manuscripts were obtained by European scholars in the late nineteenth century, the main collections being in Cambridge, London and Paris. Unfortunately, the largest manuscript collections are those of the National Baha’i Archives in Iran and the International Baha’i Archives at the Baha’i World Centre in Haifa, Israel, neither of which is accessible to the public. In general, more primary materials are available for the earlier than for the later period. The introduction of a rationalized administrative system from the 1920s onwards has meant that crucial materials have gone straight into official archives, while printed materials have tended to become blander and less inclined to reveal the full range of developments or events behind the scenes. This is noticeably true of recent volumes of the official yearbook, The Baha’i World [6].

In the case of scriptural writings, the problems are fewer and less critical. Strictly speaking, Baha’i scripture consists of the Arabic and Persian writings of the Bab, Baha’ Allah and ‘Abd al-Baha’, the first two representing ‘revealed’ scripture (in the Qur’anic sense of direct verbal inspiration), the third infallible commentary on and extension of the former two. The writings of the Bab fall into an ambiguous position, in that they are technically regarded as abrogated by those of Baha’ Allah. Although not regarded as scripture, the writings in Persian and English of Shoghi Effendi are deemed infallible interpretations of the sacred text and occupy a high position in the religion (especially in Iran, where prayers written by him are used in devotions). Taken together, these materials constitute one of the largest canons in any religion, the full extent of which is difficult to gauge because so much remains in manuscript form. The main collection of original manuscripts is at Haifa, but reliable copies may be found elsewhere.

The works of the Bab [see 25] were composed over only six years, but they fall, nevertheless, into at least two distinct periods, with major shifts in his thought between the two. These works are couched in highly ungrammatical Arabic and idiosyncratic Persian, and are at times almost unreadable, leading to serious problems of interpretation. Modem Baha’is, even Iranians, are almost wholly ignorant of these works, except in the form of selective quotations in later books. There are French translations by Nicolas of works from the later period [33–35]. A recent Baha’i publication [50] provides interpretative translations of carefully selected and not very representative passages from major works.

The writings of Baha’ Allah also fall into two main periods: works between about 1852 and 1867 (up to his break with Babism), and those from 1867 to 1892. Works from the first period [e.g. 4; 40; 41] are largely concerned with ethical issues, mysticism and scriptural interpretation; those from the second [e.g. 17; 38] increasingly with apologetics for his new religion, and with the formulation of laws, rituals and so on. Compilation volumes including early and late writings have been published [e.g. 39].

'Abd al-Baha’s works consist principally of collected letters and lectures, many of which have been translated into English [e.g. 2; 11; 19]. Shoghi Effendi wrote in both Persian and English, but his best-known works are in the latter language [e.g. 42; 44; 45]. His rhetorical and exaggerated English style has become a model for later Baha’i writing, particularly that produced by official bodies. Three collections of English letters from the Universal House of Justice have been published [51–53].

Two problems concerning scriptural materials deserve mention. The first is that no critical editions of any original-language texts have been published. The second relates to translations. Baha’i sources state that translations exist in about 700 languages, but this is misleading in that these often consist of no more than a tiny prayer-book or less. Significantly, however, all current translations are made, not from original Arabic or Persian texts, but from the English translations of Shoghi Effendi. These latter are written in fluent if somewhat archaic English, highly interpretative and wholly lacking in critical apparatuses. For the majority of Baha’is, therefore, access to scriptural authority is possible only in mediated form.

Recent translations made at Haifa adopt both the style and the technique of Shoghi Effendi. Apologetic and polemical literature is extensive and easily obtained in most languages. Material in English has been comprehensively summarized in a recent bibliography [15]. A straightforward example of contemporary Baha’i apologetics, which presents historical and doctrinal material uncritically, is [22]. There is a large body of anti-Baha’i polemic in Persian and Arabic. Early materials emphasize the movement’s heterodoxy, while more modern works attempt to place Baha’ism alongside Zionism and Freemasonry as part of a wide, Western-backed conspiracy against Islam. There is a much smaller corpus of anti-Baha’i writing from a Christian perspective, a recent example of which is [29]. Sectarian writing within the movement is limited; most current titles are published by the New Mexico-based Orthodox Baha’is: see [15: 294–302; 36].

History

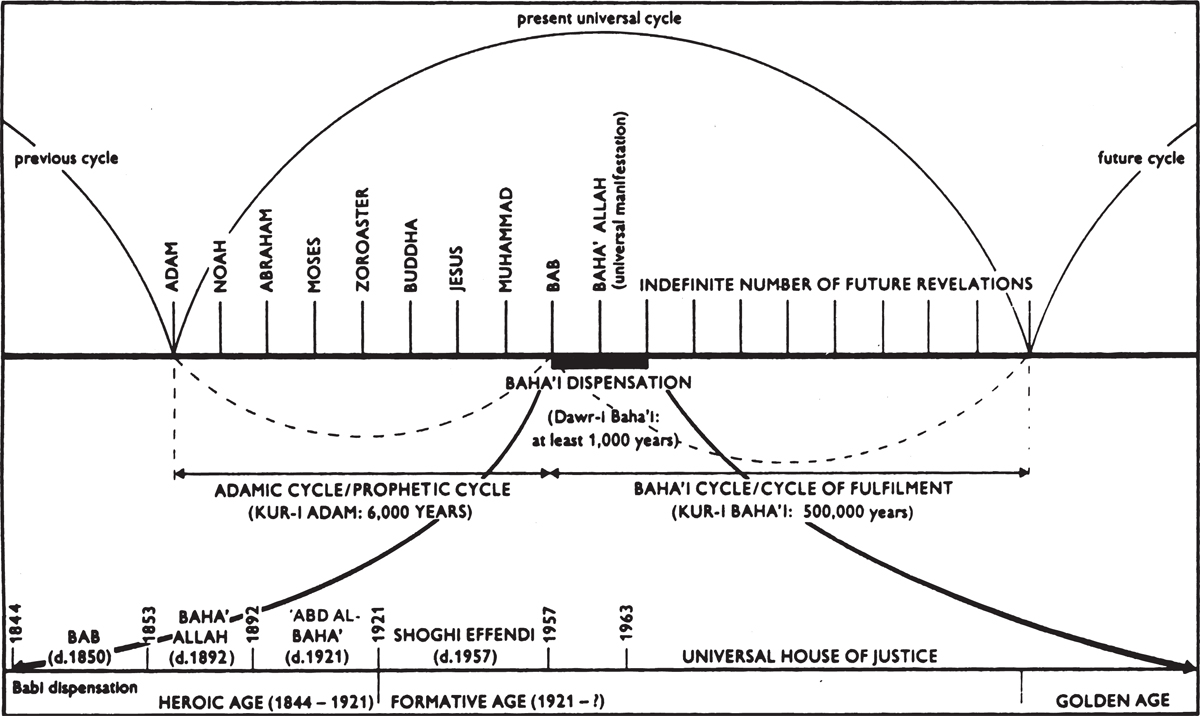

Baha’is have inherited from Islam a view of history as a linear process directed by the divine will and marked by the periodic appearance of major and minor prophets, some of whom bring books and laws and found religious communities. Whereas Muslims see Muhammad as the ‘Seal of the Prophets’ and Islam as the final religion, for Baha’is this is only true in the sense that Islam completes a series of revelations that together comprise a 6,000-year ‘prophetic cycle’, the first part of a much longer ‘universal cycle’ (see figure 16.1). According to modern Baha’i theory, the second part of the ‘universal cycle’, the ‘cycle of fulfilment’ (i.e. of prophecy) or ‘Baha’i cycle’, was initiated on 22 May 1844 by the declaration of a young Iranian, the Bab (1819–50), to be the ‘promised one’ of Islam. Although regarded as an independent prophet by Baha’is, the Bab’s central function is that of a herald for the advent of Mirza Husayn ‘Ali Baha’ Allah (1817–92), who announced his mission in Baghdad in 1863.

Baha’ Allah is regarded as the promised saviour of all ages and religions, the ‘universal manifestation’ of the divinity, who presides over the present universal cycle. His dispensation will last at least 1,000 years, and the Baha’i cycle about 500,000. It is anticipated that, before the end of this dispensation, the Baha’i religion will become the dominant faith of the planet, uniting the nations in a single theocratic system based on the religious and political teaching of Baha’ Allah and his successors. In retrospect, the lives of the Bab, Baha’ Allah, and his son ‘Abbas ('Abd al-Baha’) (1844–1921) are deemed by Baha’is to be the ‘sacred time’ par excellence, within which divine activity can be seen at work in temporal affairs. The historicity of events connected with this period is, therefore, crucial to Baha’is in much the same way that the life of the Prophet is crucial to Muslims. In reality, however, empirical historical processes have inevitably been much overlaid by preconceived schematic representations of events and personalities [see esp. 42]. The following account attempts to present a relatively neutral picture of the main phases of Babi and Baha’i history.

In the 1840s, Iranian Shi’ism was undergoing important changes, particularly with respect to the question of religious authority. During the 1820s and 1830s, an important heterodox but religiously conservative movement known as Shaykhism emerged in Iraq and Iran, emphasizing the need for continuing inspiration from the Prophet and his successors, the Imams. By the 1840s later developments in Shaykhism were concerned with the theme of an age of inner truth succeeding tat of external law in Islam. At the beginning of 1844, the leader of the Shaykhi sect died in Iraq and the movement rapidly split over the question of succession.

The most radical faction was that formed by a group of mostly Iranian clerics (‘ulema), initially in Shiraz, Iran, ten at the Shi'ite shrine centres of Iraq. This group focused on the claims of an Iranian Shaykhi merchant, Sayyid ‘Ali Muhammad Shirazi [3; 9], to be the bab or gate between men and the hidden twelfth Imam. The Bab directed his earliest followers to proclaim the imminent advent of the Imam, for which he himself had been sent to prepare the way. It was widely expected that this event would occur in Iraq in 1845, when the Bab would appear to lead the final holy war. This he failed to do, however, and the movement lost much of its original momentum, particularly after the Bab’s seclusion and repeated recantation of his claims in Shiraz in 1845 and the fission of the central group in Iraq.

Renewed impetus was given by the preaching work of several members of the original Babi hierarchy, pre-eminently a female scholar called Qurrat al-‘Ayn, who radicalized the Iraqi group. The Bab resumed his activities in secret from 1846; in 1847 he was arrested and subsequently transferred to prison in Adharbayjan province, where he continued to write prolifically. Effective control of the movement was, however, by then in the hands of several provincial leaders. In late 1847, the Bab claimed to be the hidden Imam in his persona as the Mandi (see p. 209), and in 1848 a conclave of his followers met in Mazandaran to abrogate the outward laws of Islam and inaugurate the age of inner truth. These activities were soon followed by outbreaks of mass violence between militant Babis and state troops in Mazandaran (1848–9), Nayriz (1850) and Zanjan (1850–1), in the course of which some 3,000–4,000 Babis were killed, including most of the leadership. (Modern Baha’i sources increase this figure to 20,000, but all the contemporary evidence speaks of lower numbers.) The Bab himself was executed by firing squad in Tabriz on 8 or 9 July 1850.

Following a Babi attempt on the life of the king of Iran, Nasir al-Din Shah, in August 1852 and the execution of several remaining leaders, a largely non-clerical group chose voluntary exile in Baghdad from early 1853. Leadership of this group initially fell to the son of an Iranian state official, Mirza Yahya Nuri Subh-i Azal (c.1830–1912), regarded by many as the Bab’s appointed successor. Even during the Bab’s lifetime, however, there had been problems in the movement concerning authority, and later theories of theophany had encouraged a veritable rash: of conflicting claims to some form of divinity.

The question of authority was concentrated by the early 1860s in a growing power struggle between Yahya and his half-brother, Mirza Husayn ‘Ali Baha’ Allah [10], who had by then become the de facto leader of a large section of the Baghdad community. Whereas the Azali faction was essentially conservative, seeking to preserve the late doctrines and laws of the Bab, the Baha’i sew sought radical modifications in doctrine and practice. Ire his early writings, Baha’ Allah effectively restrumsured the Bab’s highly complex system, simplifying it and preaching tolerance and love in place of the legalism and severity of the later Babi books. In this, he seems to have been much influenced by close contact with Sufi circles. Perhaps the most crucial change, however, was the explicit repudiation of Babi militancy in favour of political quietism and obedience to the state.

In 1863, most of the Baghdad community was exiled via Istanbul to Edirne in European Turkey. Whether or not he had actually made his claims semi-public before leaving Baghdad, Baha’ Allah now proclaimed himself a divine manifestation and set about the task of dismantling the Babi system and remaking it as the Baha’i faith.

The last twenty-four years of Baha’ Allah’s life were spent in exile in Palestine, first in Acre, then in its vicinity, where he died at Bahji on 29 May 1892. Curiously and significantly, remarkably little is known of his life there, in spite of the considerable freedom he possessed after leaving Acre. He continued to write extensively, dewing up laws and ordinances for his community, and incorporating into his teachings various European ideas which had gained some currency in educated circles through the Ottoman empire. Though not a recluse, he had little contact with the outside world, living a somewhat remote existence surrounded by numerous Iranian followers, by whom he was regarded with extreme deference.

Before his death, he followed the Shi'ite system of directly appointing his eldest son ‘Abbas [8] as the head of the community and inspired interpreter of the sacred text. A split nevertheless occurred between the followers of ‘Abbas and those of his younger half-brother, Mirza Muhammad ‘Ali, the effects of which lasted for some time. Both sides used excommunication as a weapon, but in the end the largely progressive faction of ‘Abbas succeeded in gaining control, largely through the superior charismatic appeal of ‘Abd al-Baha’ himself and his greater openness to a move beyond the Near East.

The first Western converts came into the movement in 1894, and during the early years of the twentieth century small groups were established in the United States, Britain, France and Germany. These were, for the most part, down from the cultic milieu of the period, often combining membership with continued affiliation to churches or cult movements such as Theosophy. But following ‘Abd al-Baha’s Western travels (1911, 1912–13) and the dispatch of orthodox teachers to America, Western Baha’ism became increasingly exclusive, while methods of routinized administration began to take precedence over earlier metaphysical and occult concerns. Several factional disputes led to the eventual predominance within the movement of those concerned mainly with social and moral issues and committed to organizational restructuring.

The appointment of Shoghi Effendi Rabbani (1897–1957) [37] as first Guardian of the Cause of God (wali-ye amr Allah, originally a Shi'i term for the Imam) proved singularly important for the later development of the movement. In his first years as Guardian, Shoghi made strenuous efforts to demystify and organize the communities under his centralized leadership. Between 1921 and 1937, he concentrated on the establishment of local and national administrative bodies throughout the Baha’i world, had by-laws drawn up for their operation, instituted the regularization of publications, and began to create an image of Baha’ism as a dynamic new world religion. Having consolidated his own authority and firmly established the principles of Baha’i organization, he turned his attention to missionary enterprise, which he directed through a series of ‘plans’ designed to introduce Baha’ism into all parts of the globe.

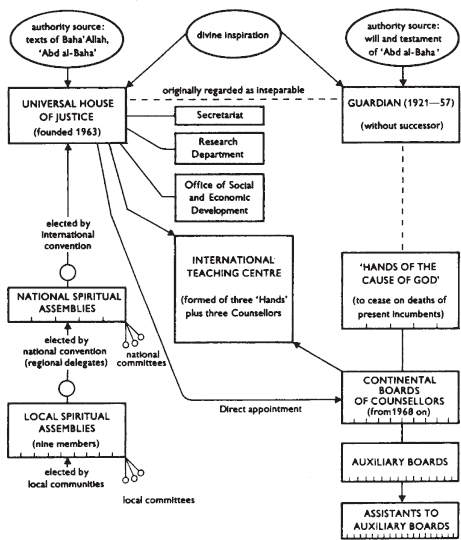

Shoghi Effendi’s death in 1957 provoked a serious crisis in the movement, the details of which remain unclear. He had been appointed first of a line of Guardians intended to lead the Baha’i community in parallel with the then unestablished legislative body, the Universal House of Justice, but had died without issue and without leaving any instructions as to the future leadership of the religion. He had, moreover, by then excommunicated all his living male relatives, so that there did not seem to be any way of perpetuating the Guardianship through a collateral line. ‘Abd al-Baha’ had been explicit about future Guardians in his will and testament, and Shoghi himself had stressed that, without the Guardianship, the Baha’i system would be ‘mutilated and permanently deprived of [the] hereditary principle’ [45: 148]. The effective termination of a hereditary Guardianship thus called into question certain basic assumptions about the workings of the system and left open the possibility of future factionalism, an eventuality which the present Baha’i leadership has come to regard as particularly threatening. It is, however, a measure of Shoghi Effendi’s success in creating a functional religious bureaucracy that, in 1963, the National Assemblies elected the first Universal House of Justice with virtually no opposition. The centralizing authority of this institution, combined with others since created at the Baha’i World Centre in Israel, has so far proved an effective means of preserving the unity of the Baha’i community in the face of occasional factionalism (see figure 16.2).

Developments in Scholarship

Popular and academic interest in Babism was sparked off by the extensive account given of the sect by Gobineau in 1865 [20], but the first serious research on the subject was carried out after 1889 by the Cambridge orientalist, E. G. Browne, who met Baha ‘Allah, Subh-i Azal and ‘Abd al-Baha’, corresponded with numerous Baha’is and Azalis, and built up an impressive collection of manuscripts. Although now dated, Browne’s work [e.g. 14; 16; 31; 32; and see 30: 29–36] is still immensely useful for its detailed examination of selected historical and scriptural materials.

It was Browne and his French. contemporary A. L. M. Nicolas [see 30: 36–10] who first drew attention to the controversial character of much Baha’i historical writing, a point which continues to be a focus of scholarly interest. Inevitably, such early studies approached the subject from an ‘orientalist’ perspective, seeing it purely in its Iranian and Islamic contexts; but, with significant changes in the nature and distribution of Baha’ism, such an approach became increasingly less satisfactory. At the same time, there was little scholarly interest in the contemporary cultic milieu, and techniques for the study of small-scale movements were still undeveloped, so it is not altogether surprising that after Browne’s death in 1926 there was a significant hiatus in academic work on the subject. Orientalists lost interest in a movement that had in most ways passed out of their field, and the apologetic nature of contemporary Baha’i writing did little to inspire fresh interest elsewhere.

Figure 16.2 Baha’i organization

Beginning with Peter Berger’s doctoral dissertation on Baha’ism in 1954 [13], a number of broadly sociological studies of the movement as a whole have been produced in the West [21; 24; 47]. At the same time, several recent studies have revived serious research on Babism and Shaykhism [5; 6; 12; 26], incorporating a wide body of previously unused primary sources and analysing the material within the contest of modern scholarship on Islam, Shi’ism and Iranian history. For the most part, such studies present an interpretation of the origins of Baha’ism radically different from that provided within the movement itself, and it seems likely that future research will continue to emphasize this disparity.

Whereas official Baha’i doctrine conflates the two movements of Babism and Baha’ism (and makes Shaykhism a prophetic movement preparing for the Bab), academics are increasingly stressing the significance of Babism as an extremist movement within nineteenth-century Shi’ism, with only tenuous links to what developed outside Iran as Baha’ism. It seems, therefore, that, although studies of the overall Babi to Baha’i development are both possible and desirable, the main thrust of future research is likely to be in two directions, one towards Babism and its Shi'i roots, the other towards Baha’ism and its move away from Islam, particularly in the West.

A tradition of Baha’i scholarship was built up in Iran throughout the twentieth century, notably by Gulpaygani, Mazandarani and Ishraq-Khavari. This adopted the standard methodology of contemporary Islamic scholarship, with little or no room for radical historical or textual criticism, and it continues to dominate Baha’i writing, not only in Iran but in the West as well, where a knowledge of sources rather than an ability to analyse them is the main scholarly criterion. This problem has been exacerbated by the priority given in the movement to works of propagation, so that writing is either openly apologetic or produced with apologetic criteria in mind, and by the mandatory vetting by special committees of all materials to be published by Baha’is. Recent years, however, have seen the beginnings of moderately serious scholarship within the movement, with a shift of focus away from history towards doctrine, administration and scriptural exegesis. This process has been encouraged by official bodies like the Association for Baha’i Studies, the ‘Studies in Babi and Baha’i History’ series of publications, a number of periodicals and the imminent publication of a Baha’i encyclopaedia.

Internal scholarship of this kind is strictly controlled, mainly by panels for the review of publications, and attempts to introduce more radical approaches have met with criticism and led to the closure of some journals and a publishing house. Nevertheless, there are still signs that some younger Baha’i academics are willing to question official assumptions and that a crisis of some son will in time develop between them and representatives of the orthodox camp. The outcome of such a debate is likely to be crucial to the future shape of a religion which makes the harmony of faith and reason one of the central bases for its appeal.

Teachings

The characteristic doctrines of Baha’ism have been succinctly described by Shoghi Effendi as follows:

The Baha’i Faith upholds the unity of God, recognizes the unity of His Prophets, and inculcates the principle of the oneness and wholeness of the entire human race. It proclaims the necessity and inevitability of the unification of mankind … enjoins upon its followers the primary duty of an unfettered search after truth, condemns all manner of prejudice and superstition, declares the purpose of religion to be the promotion of amity and concord, proclaims its essential harmony with science, and recognizes it as the foremost agency for the pacification and the orderly progress of human society. It unequivocally maintains the principle of equal rights, opportunities, and privileges for men and women, insists on compulsory education, eliminates extremes of poverty and wealth, abolishes the institution of priesthood, prohibits slavery, asceticism, mendicancy, and monasticism, prescribes monogamy, discourages divorce, emphasizes the necessity of strict obedience to one’s government, exalts any work performed in the spirit of service to the level of worship, urges either the creation or the selection of an auxiliary international language, and delineates the outlines of those institutions that must establish and perpetuate the general peace of mankind. [43: 3–4]

It is vital to the faith of Baha’is that these and other doctrines contained in their scriptures be regarded as wholly original, not merely in the sense of being largely ‘new’, but as emanating directly from God. This view owes much to the Islamic theory of divine revelation as a unidirectional process whereby the untreated Word is conveyed to men unaltered through the inert medium of the prophet. The Bab and Baha’ Allah are regarded as ‘manifestations of God’, a term borrowed from Shi’ism and theosophical Sufism. They are, in other words, incarnations of the eternal Logos, which has appeared in all previous major prophets, and as such possess the dual conditions of humanity and divinity. In the later writings of Baha’ Allah, however, this comes close to a doctrine of incarnationism (e.g. ‘the essence of the pre-existent has appeared’). The knowledge of God can be obtained only through recognition of his manifestations, a recognition which in turn entails absolute obedience to their laws [39: 49–50, 329–30].

Divine revelation is progressive (though sporadic rather than continuous), in accordance with the exigencies of changing human circumstances. At the same time, all developments in the human sphere are ultimately generated by the creative power of the divine word in each age [39: 141–7]. This doctrine entails the more problematic corollary that the teachings of a prophet must be chronologically prior to expressions of the same ideas in the world at large (in itself evidence that the prophet has not been influenced by the thoughts of others). Such a view, while clearly important as a means of establishing the credentials of Baha’ism for its followers, is equally clearly difficult to sustain empirically and has the disadvantage of obscuring the actual process through which the Baha’i teachings developed. The following remarks may help to clarify that process.

The majority of Baha’is today are converts from non-Islamic backgrounds and, as a result, there is widespread ignorance within the community of the extent to which the basic doctrines of the religion are Islamic (and, in particular, Shi'ite) in origin. Leaving aside for the moment the question of individual doctrines, it is incontrovertible that the context within which these operate differs in no radical sense from the central presuppositions of Islam. History is a process directed by periodic divine intervention, the purpose of which is to reveal the will of God in the form of a shari'a, a comprehensive ethical, legal and social system designed to fashion and regulate the affairs of society at all levels. Western distinctions between church and state, religion and politics, do not strictly apply here, for the sacred law embraces all areas of human experience. The Baha’i shari'a is derived from two primary sources: the sacred text and the legislation of the Universal House of justice. In practice, only a small portion of Baha’i law is either known or acted on outside Islamic countries, though the recent publication of an English translation of the Kitab al-aqdas [7] suggests that the authorities now consider it appropriate to start introducing legislation more widely.

Yet another central theme developed from Shi’ism is the notion of the ‘covenant’, through which the authority of ‘Abd al-Baha’, Shoghi Effendi and the present leadership is guaranteed and the unity of the religion in theory assured. Thus Baha’ Allah appointed ‘Abd al-Baha’, who in turn appointed Shoghi Effendi; the Universal House of Justice is similarly elected on the authority of a statement by Baha’ Allah to the effect that such a body would be divinely guided. As in Shi’ism, this concept involves the corollary of the expulsion from the community and the subsequent shunning of those who have rebelled against the authority of the appointed head of the faith.

Even several apparently modernist teachings, such as the harmony of religion and science, the oneness of humankind or the unity of revealed religion are, in essence, typically Islamic. This primary Islamic stratum in Baha’ism was modified in two ways: first, in Baha’ Allah’s reaction against Babism; and second, in his response to external influences, particularly modernist and Western ideas. Although Baha’ Allah retained and simplified most of the religious and metaphysical teachings of the Bab, he reacted strongly against many of his laws and ordinances, especially those which underpinned the fanaticism and exclusivism that characterized the Babi movement. Many of Baha’ Allah’s earliest writings speak of the reforms he had instituted among the Babis, notably in the abrogation of laws directed against non-believers, above all the waging of holy war. ‘Abd al-Baha’ was later to characterize Baha’ism as, in a sense, the diametrical opposite of Babism. Whereas the latter emphasized ‘the striking of necks, the burning of books and papers, the destruction of shrines, and the universal slaughter of all save those who believed and were faithful’, the former stressed compassion, mercy, association with all peoples, trustworthiness towards others and the unification of humankind [1]. Later, however, Shoghi Effendi’s wholesale conflation of Babism and Baha’ism served to obscure this important distinction, and modern Baha’i writing often describes as ‘the teachings of the Bab and Baha’u'llah’ what are, in fact, mainly doctrines of the latter [e.g. 30: XXIII – XXV].

Baha’ Allah may have been influenced in this direction by Sufi and Christian doctrines. His early writings contain quotations from Sufi writers and the New Testament, and he himself was for a time a Sufi dervish. In his later exile in Turkey and Palestine, he came into contact with Europeans and Islamic modernists, as did ‘Abd al-Baha’, and seems to have been extremely receptive to the Western ideas then gaining currency in the Middle East. As a result, his writings in Acre incorporated notions such as collective security, world government, the use of an international auxiliary language and script, universal compulsory education and so on. ‘Abd al-Baha’ seems to have been particularly interested in these and related matters, as is obvious from an early work [18], and in his later talks and letters he addressed himself increasingly to topics of interest to Western converts. He spoke at length concerning the equality of the sees, the need for an independent search after truth, the harmony of science and religion, and the solution of economic problems, and frequently refereed to issues such as evolution, social and scientific progress, labour relations, socialism and education.

Having been an essentially progressivist movement in the early years of the twentieth century, Baha’ism is still portrayed as such in contemporary literature, and Baha’is continue to identify themselves with what are seen as ‘progressive’ causes, such as world government or religious and racial harmony. The Baha’is possess non-governmental observer status with the UN and are regular participants at international conferences on human rights, women, and environmental and Third World issues. However, until the 1980s direct Baha’i participation in movements for social change was severely limited by a long-standing prohibition on involvement in politics. This was reinforced by Shoghi Effendi’s conviction that believers should leave the outside world to collapse, while building a new Baha’i order to take its place.

Although this remains the underlying position, in 1983 the Universal House of Justice announced that social action was now to be incorporated into Baha’i community life and set up an Office of Social and Economic Development in Haifa to coordinate such activities. This shift towards a more activist policy is a direct response to the growth of the religion in the Third World, and projects are now being undertaken in several spheres, including literacy, social development, agriculture and medicine. As with similar programmes sponsored by other religious groups, Baha’i development projects are closely linked to the movement’s broader missionary enterprise.

Development issues apart, the Baha’is seem to be experiencing problems similar to those faced by Catholics and other conservative churches in responding to broader social change, particularly in the West. While Baha’i doctrine emphasizes the need for periodic adjustments of religious law and practice to accommodate change in other spheres, such adjustment can only be made through the appearance of a new prophet. The Universal House of Justice can legislate on matters not already dealt with in Scripture, but it is powerless to abrogate existing rulings. This leaves the Baha’is upholding illiberal attitudes on numerous issues of modem social concern, such as homosexuality, cohabitation, abortion, the use of alcohol and drugs, euthanasia and capital punishment. In the Third World, the most likely area of conflict between Baha’i progressivism and conservatism lies in the movement’s commitment to the principle of absolute obedience to established authority.

At a deeper level, there is a marked strain of authoritarianism within the movement itself, something which has caused tensions and even division in the past. Preservation of Baha’i unity remains an overriding concern, with unquestioning loyalty to the institutions of the faith seen as the best means to secure and maintain it. Further crises over this issue are, therefore, almost inevitable as the movement grows and diversifies.

Practices

The question of contemporary religious practice in Baha’ism is complicated by the existence of a gap between prescriptive regulations (which are extensive) and actual practices (which are limited), particularly outside Iran, although as time goes on more and more ritual and other prescribed practices are being introduced [see 28]. The basic pattern is again Islamic, the main religious obligations being those of ritual prayer (salat), annual fasting (sawm) and pilgrimage (hajj and ziyara) (see pp. 183–99). Many customary rites in Islam (such as the rites of passage) tend to be prescriptive in Baha’ism, although the forms tend to follow Islamic practice quite closely.

Salat is private, with three alternative versions to be performed (once in twenty-four hours, once at noon, or thrice daily), with ritual ablutions. The prayer-direction (qibla) is the tomb of Baha’ Allah near Acre. Fasting takes place during the last month of the solar Baha’i year (2–20 March) on the Islamic pattern. As in Islam, there are exemptions for certain categories, such as the sick and pregnant women. Pilgrimage is less well defined. Strictly speaking, the Islamic hajj to Mecca has been replaced by two pilgrimages, both of which are restricted to men. These are to the house of the Bab in Shiraz and to that of Baha’ Allah in Baghdad, and both involve elaborate ritual ceremonies. In practice, it has never been possible for Baha’is to perform these hajj rites, and the destruction of the house of the Bab in 1979 following the Iranian revolution has introduced a fresh complication. ‘Abd al-Baha’ made obligatory what may be termed ‘lesser pilgrimage’ (ziyara) to the tombs of Baha’ Allah and the Bab (now in Haifa), this being the form of visitation made by Shi'is to the tombs of Imams and their relatives or by Sunnis to the shrines of saints. Visitation to the shrines in Israel has become the standard Baha’i pilgrimage; indeed, most non-Iranian Baha’is are unaware that other forms exist, and even imagine the ziyara to be the ritual equivalent of the Islamic hajj, which it is not. Ziyaras can also be made to numerous other Baha’i holy sites, particularly in Iran, and special prayers exist for recitation at these. The grave of Shoghi Effendi in London has become an important pilgrimage site in recent years.

Devotional and ceremonial practices are generally informal. At the local level, communal activities are organized by local assemblies, which are elected annually. As in Islam, there is no priesthood, but recent years have seen the emergence of a semi-professional appointed hierarchy responsible for the propagation of the faith and protection from external attacks and internal dissent. In Arabic, these individuals (who include women) are known as 'ulema, although their functions are not currently comparable to those of the Islamic clergy. They perform no ceremonial or intercessory functions. The principal communal gatherings are those held for the Nineteen-day Feast on the first day of each Baha’i month (of which there are nineteen, each of nineteen days) and for the nine principal holy days during the year (on which work has to be suspended) (see appendix to this chapter). Feasts, which are preferably held in the homes of individuals, consist of three portions: the reading of prayers and sacred texts; administrative consultation; and the sharing of food and drink. Holy-day meetings generally consist of readings of prayers and devotional texts designated for the occasion, sometimes with sermons or historical readings relevant to commemorative festivals.

Most Baha’i communities meet in private homes or halls rented or purchased for the purpose. There are in existence only a handful of houses of worship (Mashriq al-adhkar), which are show-pieces built on a continental basis and at present used largely for public gatherings. They follow a common pattern of circular design incorporating nine entrances and a dome, but are otherwise architecturally diverse and, in several cases, represent fine examples of modern religious architecture. The seven temples now in use are located in the United States (Wilmette, Illinois), Germany, Panama, Australia, India, Uganda and Samoa.

Rites of passage are limited to naming ceremonies for babies (circumcision is not mandatory), marriage and funeral rites. Marriage is conditional on the consent of both parties and all living parents; arranged marriages are permitted and are common in Iran and elsewhere. The ceremony is flexible, the minimum requirement being the recitation by the bride and groom in the presence of witnesses of two verses adapted from the Persian Bayan. Simplicity is preferred, but ceremonies are usually expanded with music and readings from sacred texts and tend to follow cultural norms. The preparation and burial of the dead are carried out according to complex regulations. Cremation is not prohibited but is regarded as undesirable. The place of burial is to be no more than one hour’s journey from the place of death and the plot is to be arranged so that the feet of the dead face the Baha’i qibla. The ritual salat for the dead (used only for adults) is the only occasion on which communal recitation of prayer is permitted.

Babism followed popular Shi’ism in being particularly rich in thaumaturgical and magical practices, such as the use of talismans, engraved stones and incantatory prayers. There are fewer such practices in Baha’ism, but they have not been wholly eradicated. There are numerous thaumaturgical, protective and supererogatory prayers, most of them as yet little known outside Iran. A calligraphic representation of the ‘greatest name of God’ in Arabic is found in most Baha’i homes:

Ya baha’ al-abha – O splendour of the most splendid

Equally common is the much stylized representation of the name Baha’, designed to be engraved on ringstones, which owes much of its form to magical symbols found in popular Islam:

Strictly speaking, the symbol of the Baha’i religion is a five-pointed star, but it is much more common to find a nine-pointed star on jewellery and publications, as well as on gravestones.

Distribution

The key element in the growth of Baha’ism since the 1930s has been careful planning – a theme developed by Hampson [21] in the only full-length study of the subject. Since 1937, a series of national, regional and global missionary ‘plans’ have been conceived to coordinate the expansion and consolidation of the religion. Growth has been assessed in terms of ethnic groups, territories and localities represented, administrative bodies founded, assemblies legally incorporated, property purchased or construed, literature translated or published, and so on. The result has been an impressive overall increase in all these areas, laying the base for future expansion. Significant gains have been made since the 1960s in several Third World countries, with expansion currently most rapid in India, South Vietnam, South America, the Pacific and parts of sub-Saharan Africa, to the extent that Baha’ism is now ‘overwhelmingly a “Third World” religion’ [48]. Although Iranians, Americans and Europeans remain the most active in missionary and administrative work, they now form a very low percentage of the Baha’i population world-wide: Westerner form 3 per cent of the total, while Iranians (94 per cent in 1954) now account for only 6 per cent. Conversion to Baha’ism is extremely rare in Muslim countries, where restrictions are often severe, and there is no reason to think this situation will improve in the foreseeable future.

There is no question that Baha’ism is very widely distributed, to the extent that the Britannica Book of the Year for 1988 described it as the second most widely spread religion after Christianity. Until recently, however, it has been difficult to interpret this spread in more precise terms, since available statistics have been restricted to ‘assemblies’ or ‘localities’ rather than individuals. In the past few years, however, figures for individual adherents have been made public. Although these are still open to question on several counts, they do provide researchers for the first time with a solid basis on which to make calculations (for a detailed analysis, see [48: 69–74]). The most recent estimate of Baha’i populations was carried out for 1988. According to these rounded figures, the total number of Baha’is in the world was then 4,490,000 [48: 72].

| Table 16.1 Statistics on Baha’ism | ||||

| Year | Total countries opened | Total national assemblies | Total local assemblies | Total localities (with or without assemblies) |

| 1921 | 35 | |||

| 1954 | 128 | 12 | 708 | 3,117 |

| 1964 | 240 | 56 | 4,566 | 15,186 |

| 1973 | 335 | 113 | 17,037 | 69,541 |

| 1979 | 343 | 125 | 23,624 | 102,704 |

| 1992 | 218a | 165 | 20,435a | 120,046 |

| a Reduction owing to administrative changes. | ||||

These statistics are, however, distorted in a number of ways, most importantly by the lack of accurate figures for disaffiliated and inactive believers. The Baha’i administration sets low requirements fog membership but insists on formal withdrawal. Understandably, this latter is seldom forthcoming and, as a result, large numbers of individuals and even localities may be officially registered long after informal disaffiliation. That figures for disaffection may be high is suggested by Hampson’s finding that, in 1976, mall was returned unopened from the addresses of 31 per cent of US adherents [21: 230]. It is also difficult to estimate how successful post-registration consolidation has been in mass-conversion areas in the Third World. In some places, there appear to be problems of multiple affiliation.

Another factor that should be taken into account when comparing current figures with those for earlier periods is the 1979 decision of the Universal House of justice that all newly born children of Baha’is be automatically registered as Baha’is.

Conclusion

The development of Baha’ism may prove to be an important exemplum for future trends in the religious sphere. In the past, religious traditions have developed self-consciousness as distinct, reified systems only after lengthy periods of growth. With the partial exception of Islam, no major tradition has been founded or initially developed as a self-defined entity separate from others. The notion of ‘world religions’ is itself relatively recent. (On these and related points, see [49].)

In the modern period, however, it does not seem possible for unselfconscious development of this kind to take place. New movements emerge into a universe of already reified and competing systems. In order to compete, they are obliged to define themselves within terms of the prevailing norms. Baha’ism would seem to be the first of the new religious movements that shows signs of developing as an independent tradition. In origin, it belongs wholly to the pre-modern world of nineteenth-century Iran, but the significant phases of its development are marked by various responses to Western ideas and methods. Since the 1920s, its leaders have planned, systematized and organized in order to make it conceptually and actually a ‘new world faith’. It has, in Hampson’s words, ‘managed its own development’ [24: 2]. The future progress of Baha’ism must remain matter for speculation, but without doubt a firm basis has been laid for continued expansion in some regions. It will be surprising if the movement succeeds in resisting tendencies towards fission, heterodoxy and popularization if it moves much beyond its present sectarian dimensions. But there is already much to learn from its progress so far. Conscious planning, rational organization and long-term strategies have, it seems, become keys to religious growth in the modern age.

Appendix: The Baha’i Calendar

The Baha’i calendar is known as the Badi' Calendar and was devised by the Bab. It is based on a solar year of nineteen months, each of nineteen days, plus four intercalary days (five in leap years). There are also cycles (vahids) of nineteen years, nineteen of which constitute a Kullu shay'. Baha’is date the commencement of the Badi' era from the New Year’s Day (21 March) preceding the announcement of the Bab’s mission in May 1844.

| Days of the week | |||

| Day | Arabic name | English name | Translation |

| 1st | Jalal | Saturday | Glory |

| 2nd | Jamal | Sunday | Beauty |

| 3rd | Kamal | Monday | Perfection |

| 4th | Fidal | Tuesday | Grace |

| 5th | Idal | Wednesday | Justice |

| 6th | Istijlal | Thursday | Majesty |

| 7th | Istiglal | Friday | Independence |

| Name of the month | |||

| Month | Arabic name | Translation | First day |

| 1st | Baha’ | Splendour | 1 March |

| 2nd | Jalal | Glory | 9 April |

| 3rd | Jamal | Beauty | 28 April |

| 4th | ‘Azamat | Grandeur | 17 May |

| 5th | Nur | Light | 5 June |

| 6th | Rahmat | Mercy | 24 June |

| 7th | Kalimat | Words | 13 July |

| 8th | Kamal | Perfection | 1 August |

| 9th | Asma’ | Names | 20 August |

| 10th | ‘Izzat | Might | 8 September |

| 11th | Mashiyyat | will | 27 September |

| 12th | ‘Ilm | Knowledge | 16 October |

| 13th | Qudrat | Power | 4 November |

| 14th | Qawl | Speech | 23 November |

| 15th | Masa’il | Questions | 12 December |

| 16th | Sharaf | Honour | 31 December |

| 17th | Sultan | Sovereignty | 19 January |

| 18th | Mulk | Dominion | 7 February |

| 19th | Ala’ | Loftiness | 27 March |

Ayyam-i-Ha’ (intercalary days): 26 February to 1 March inclusive.

Feasts, anniversaries and days of fasting

Feast of Ridvan (Declaration of Baha’ Allah), 21 April to 2 May 1863

Feast of Naw-Ruz (New Year), 21 March

Declaration of the Bab, 23 May 1844

The Day of the Covenant, 26 November

Birth of Baha’ Allah, 12 November 1817

Birth of the Bab, 20 October 1819

Birth of ‘Abd al-Baha’, 23 May 1844

Ascension of Baha’ Allah, 29 May 1892

Martyrdom of the Bab, 9 July 1850

Ascension of ‘Abd al-Baha’, 28 November 1921

Fasting season lasts nineteen days beginning with the first day of the month of ‘Ala’, 2 March – the Feast of Naw-Ruz follows immediately thereafter.

Holy days on which work should be suspended

The first day of Ridvan

The ninth day of Ridvan

The twelfth day of Ridvan

The anniversary of the declaration of the Bab

The anniversary of the birth of Baha’ Allah

The anniversary of the birth of the Bab

The anniversary of the ascension of Baha’ Allah

The anniversary of the martyrdom of the Bab

The feast of Naw-Ruz

Bibliography

1 ‘ABD AL-BAHA, Makatib-i ‘Abd al-Baha’, vol. 2, Cairo, 1912, p. 266

2 ‘ABD AL-BAHA, Talks by Abdul Baha Given in Paris, London, Baha’i Publishing Society/East Sheen, Unity Press, 1912; 4th edn London, G. Bell, 1920; US edn as The Wisdom of Abdu'l-Baha, New York, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1924; also publ. as Paris Talks, London, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1961

3 ‘ABD AL-BAHA, A Traveller’s Narrative Written to Illustrate the Episode of the Bab (ed. and tr. E. G. Browne), 2 vols, London, Cambridge University Press, 1891; repr. Amsterdam, Philo Press, 1975; new edn Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1980

4 ALI-KULI KHAN (tr.), Baha’u'llah, The Seven Valleys and the Four Valleys, Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1945 (New York, 1936); 3rd rev. edn London, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1978

5 AMANAT, ABBAS, Resurrection and Renewal: The Making of the Babi Movement in Iran, 1844–1850

6 The Baha’i Yearbook, 1925–1926, New York, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1926; subsequently publ. as The Baha’i World, vols 1–7, New York, 1928–39; vol. 8, Wilmette, IL, 1942; vol. 9, New York, 1945; vols 10–12, Wilmette, IL, 1949–56; vols. 13–18, Haifa, 1971–82

7 BAHA’U'LLAH, The Kitáb-i-Aqdas, The Most Holy Book, London, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1993

8 BALYUZI, H. M., ‘Abdu'l-Baha, London, George Ronald, 1971; Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust

9 BALYUZI, H. M., The Bab, Oxford, George Ronald, 1973

10 BALYUZI, H. M., Baha’u'llah, Oxford, George Ronald, 1980

11 BARNEY, L. C., (tr.), ‘Abd al-Baha, Some Answered Questions, London, Trübner/Philadelphia, Lippincott, 1908; London, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1961; Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1981

12 BAYAT, M., Mysticism and Dissent: Socioreligious Thought in Qajar Iran, Syracuse, NY, Syracuse University Press, 1982

13 BERGER, P., ‘From Sect to Church: A Sociological Interpretation of the Baha’i Movement’, PhD dissertation, New School for Social Research, New York, 1954

14 BROWNE, E. G., (ed.), Materials for the Study of the Babi Religion, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1918

15 COLLINS W. P., Bibliography of English-Language Works on the Bábi and Bahá'í Faiths 1844–1985, Oxford, George Ronald, 1990

16 COOPER, R., The Baha’is of Iran, London, Benjamin Franklin House, 1987 (Minority Rights Group Report no. 51); 4th edn with revisions by the Minority Rights Group, 1991

17 ELDER, E. E., and MILLER, W. MCE. (trs), Baha’u'llah, Al-Kitab al-Aqdas, or, The Most Holy Book, London, Royal Asiatic Society, 1961 (= 1962)

18 GAIL, M. (tr.), ‘Abd al-Baha, The Secret of Divine Civilization, Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1957; 2nd edn 1970

19 GAIL, M. (tr.), ‘Abd al-Baha, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu'l-Baha … (tr. by a committee at the Baha’i World Centre and by Marzieh Gail), Haifa, Baha’i World Centre/Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1978

20 GOBINEAU, J. A. DE, Les Religious et philosophies dans l'Asie centrale, Paris, Didier, 1865; 10th edn Paris, Gallimard, 1957

21 HAMPSON, A., ‘The Growrh and Spread of the Baha’i Faith’, PhD dissertation, Honolulu, University of Hawaii, 1980 (University Microfilms 80–22, 655)

22 HATCHER, W. S., and MARTIN, J. D., ‘The Bahá'í Faith’: The Emerging Global Religion, San Francisco, Harper & Row, 1984

23 HUSAIN HAMADANI M., The New History (Tarikh-i-Jadid) of Mirza ‘Ali Muhammed the Bab by Mirza Huseyn of Hamadan (tr. and ed. E. G. Browne), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1893; repr. Amsterdam, Philo Press, 1975

24 JOHNSON, V., ‘An Historical Analysis of Critical Transformations in the Evolution of the Baha’i World Faith’, PhD dissertation, Waco, TX, Baylor University, 1974 (University Microfilms 75–20, 564)

25 MACEOIN D. M., Early Babi Doctrine and History: A Survey of Source Materials, Leiden, Brill, 1992

26 MACEOIN, D. M., ‘From Shaykhism to Babism: A Study in Charismatic Renewal in Shi'i Islam’, PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge, 1979 (University Microfilms 81–70, 043)

27 MACEOIN, D. M., A People Apart: The Baha’i Community of Iran in the Twentieth Century, London, School of Oriental and African Studies, Occasional Papers, 1989

28 MACEOIN, D. M., Ritual in Babism and Baha’ism, London, I. B. Tauris, 1994

29 MILLER, W. MCE., The Baha’i Faith: Its History and Teachings, South Pasadena, William Carey Library, 1974

30 MOMEN, M. (ed.), The Babi and Baha’i Religions, 1844–1944: Some Contemporary Western Accounts, Oxford, George Ronald, 1981

31 MOMEN, M. (ed.), Selections from the Writings of E. G. Browne on the Bábi and Bahá'í Religions, Oxford, George Ronald, 1987

32 NABIL-I-A ‘ZAM (Mulla Muhammad Zarandi), The Dawn Breakers: Nabil’s Narrative of the Early Days of the Baha’i Revelation (tr. and ed. Shoghi Effendi), New York, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1932; British edn (abr.) London, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1953

33 NICOLAS, A. L. M. (tr.), Le Béyân arabe (by ‘Ali Muhammad Shirazi, called the Bab), Paris, Leroux, 1905

34 NICOLAS, A. L. M. (tr.), Le Béyân persan (by ‘Ali Muhammad Shirazi, called the Bab), 4 vols, Paris, 1911–14

35 NICOLAS, A. L. M.. (tr.), Le Livre des sept preuves de la mission du Bab (by ‘Ali Muhammad Shirazi, called the Bab), Paris, Maisonneuve, 1902

36 The Orthodox Baha’i Faith: The Cause for Universal Religion, Brotherhood and Peace: A Sketch of Its History and Teachings, Roswell, NM, Mother Baha’i Council of the United States, 1981

37 RUHIYYIH RABBANI, The Priceless Pearl, London/Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1969

38 SHOGHI EFFENDI (tr.), Baha’u'llah, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1941; rev. edn Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1976

39 SHOGHI EFFENDI (tr.), Baha’u'llah, Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u'lah, Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1948; New York, 1935; London, 1949; 2nd rev. edn Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1976

40 SHOGHI EFFENDI (tr.), Baha’u'llah, The Hidden Words, London, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1932, 1944; Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1939; rev. edn 1954

41 SHOGHI EFFENDI (tr.), Baha’u'llah, The Kitab-i-Iqan. The Book of Certitude, 1931, New York, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1937; 2nd edn London, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1961; rev. edn Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1974

42 SHOGHI EFFENDI, God Passes By, Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1944; rev. edn 1974

43 SHOGHI EFFENDI, Guidance for Today and Tomorrow, London/Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1953

44 SHOGHI EFFENDI, The Promised Day is Come, Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1941, rev. edn Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1980; Bombay, Baha’i Assembly of Bombay, 1942

45 SHOGHI EFFENDI, The World Order of Baha’u'llah, New York, Baha’i Publishing Committee, 1938; rev. edn Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1965, copyr. 1955

46 SMITH, P., The Babi and Baha’i Religions: From Messianic Shi’ism to a World Religion, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987

47 SMITH, P., ‘A Sociological Study of the Babi and Baha’i Religions’, PhD dissertation, University of Lancaster, 1982

48 SMITH, P., and MOMEN, M., ‘The Baha’i Faith 1957–1988: A Survey of Contemporary Developments’, Religion, vol. 19, 1989, pp. 63–91

49 SMITH, W. CANTWELL, The Meaning and End of Religion, New York, Macmillan, 1962, 1963; London, New English Library, 1965; London, SPCK, 1978

50 TAHERZADEH, M. (tr.), Selections from she Writings of the Báb (by ‘Ali Muhammad Shirazi, called the Bab), Haifa, Baha’i World Centre, 1976

51 UNIVERSAL HOUSE OF JUSTICE, Messages, 1968–1973, Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1976

52 UNIVERSAL HOUSE OF JUSTICE, Wellspring of Guidance: Messages, 1963–1968, Wilmette, IL, Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1969; rev. edn 1976

53 UNIVERSAL HOUSE OF JUSTICE, A Wider Horizon: Selected Messages of the UHJ 1983–1992, Riviera Beach, FL, Palabra Publications, 1992