The scientific study of biological criminology started on a cold, gray November morning in 1871 on the east coast of Italy. Cesare Lombroso, a former Italian army medic, was working as a psychiatrist and prison doctor at an asylum for the criminally insane in the town of Pesaro.1 During a routine autopsy he peered into the skull of an infamous Calabrian brigand named Giuseppe Villella. At that moment he experienced an epiphany that was to radically alter both his life and the course of criminology. He described this pivotal experience in the following way:

I seemed to see all at once, standing out clearly illuminated as in a vast plain under a flaming sky, the problem of the nature of the criminal, who reproduces in civilized times characteristics, not only of primitive savages, but of still lower types as far back as the carnivores.2

What did Lombroso see as he gazed deep into Villella’s skull? He detected an unusual indentation at its base, which he interpreted as reflecting a smaller cerebellum—or “little brain”—seated under the two larger hemispheres of the brain. From this singular and almost ghoulish observation, Lombroso went on to become the founding father of criminology, producing an extraordinarily controversial theory that was to quickly have significant cross-continental influence.

Lombroso’s theory had two pivotal points: that there was a basis to crime originating in the brain, and that criminals were an evolutionary throwback to more primitive species. Criminals, Lombroso believed, could be identified on the basis of “atavistic stigmata”—physical characteristics from more primitive stages of human evolution, such as a large jaw, a sloping forehead, and a single palmar crease. Based on his measurements of such traits, Lombroso created an evolutionary hierarchy that placed Jews and Northern Italians at the top and Southern Italians (including Villella), along with Bolivians and Peruvians, at the bottom. Perhaps not coincidentally, at the time there was much higher crime in the poorer, more agricultural south of Italy, one of the many symptoms of the “southern problem” besetting the recently unified nation.

These beliefs, which were based partly on Franz Gall’s phrenological theories, flourished throughout Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They were discussed in parliaments and throughout public administrations as well as in universities. Contrary to appearances, Lombroso was a famous, well-meaning intellectual, as well as a staunch supporter of the Italian Socialist Party. He wished to employ his research to serve the public good. He abhorred retribution and instead placed the emphasis of punishment on the protection of society.3 He strongly advocated rehabilitation of offenders. Yet at the same time he felt that the “born criminal” was, to paraphrase Shakespeare’s Prospero, “a devil, a born devil, upon whose nature nurture can never stick,”4 and consequently favored the death penalty for such offenders.

Perhaps because of these views, Lombroso has become infamous in the annals of criminological history. The theory he spawned turned out to be socially disastrous, feeding the eugenics movement in the early twentieth century and directly influencing the persecution of the Jewish people. The thinking and vocabulary of Mussolini’s racial laws of 1938, which excluded Jews from public schools and ownership, owes a rhetorical debt to Lombroso’s writings and theories, as well as those of the students who followed him into the early twentieth century.5 The major difference in Mussolini’s laws was that Aryans replaced Jews at the top of the racial hierarchy, and Jews were relegated to the bottom alongside Africans and below Southern Italians. The dreadful irony in this—a fact carefully avoided in almost all references to Lombroso in contemporary criminological texts—is that Lombroso himself was Jewish.

Understandably, Lombrosian thinking fell into disrepute in the twentieth century and was replaced by a sociological perspective on human behavior—including crime—which still holds sway today. It is not too difficult to see how this biological-to-social pendulum swing came about. Crime, after all, is a social construction. It is defined by the law, and socio-legal processes hold sway over conviction and punishment. Laws change across time and space, and acts such as prostitution that are illegal in one country are both legal and condoned in others. So how can there possibly be a biological and genetic contribution to a social construction? Surely social causation must be central to crime? This simple argument has made a compelling case for an almost exclusive sociological and social-psychological perspective on crime, a seemingly sound bedrock on which to build workable principles for social control and treatment.

What do I make of Lombroso’s claims? Of course I reject Lombroso’s evolutionary scale that placed Northern Italians at the top and Southern Italians at the bottom. Not least because I am half Italian, through my mother, who was from Arpino in the southern half of Italy—I’m not an evolutionary throwback to a more primitive species. And yet, unlike other criminologists, I do believe that Lombroso, stumbling as he did amid his offensive racial stereotyping and fumbling with the hundreds of macabre prisoner skulls he had collected, was on the path toward a sublime truth.

We’ll now see how modern-day sociobiologists have made a far more coherent and compelling argument than Lombroso ever could have that there is, in part, an evolutionary basis to crime that provides the foundations for a genetic and brain basis to crime—the anatomy of violence. We’ll explore violence in its many shapes and forms, from homicide to infanticide to rape, and suggest from an anthropological perspective how different ecological niches may have given rise to the ultimate in selfish, cheating behavior—psychopathy.

So why are people more than a hundred times more likely to be murdered on the day they are born than to be murdered on an average day in their life? Why are they fifty times more likely to be murdered by their stepfather than by their natural father? Why do some men, not content to rape only strangers, also want to rape their wives? And why on earth do some parents kill their kids?

These are among a host of questions that baffle society and that seem impenetrable from a social perspective. But there is an answer: the dark forces of our evolutionary past. Despite what we may think of our good-naturedness, we are, it could be argued, little more than selfish gene machines that will, when the time and place is ripe, readily use violence and rape to ensure that our genes will be reproduced in the next generation.

In evolutionary terms, the human capacity for antisocial and violent behavior wasn’t a random occurrence. Even as early hominids developed the ability to reason, communicate, and cooperate, brute violence remained a successful “cheating” strategy. Most criminal acts can be seen, directly or indirectly, as a way to take resources away from others. The more resources or status a man has, the better able he is to attract young, fertile females. These women in turn are on the lookout for men who can give them the protection and the resources they need to raise their future children.

Many violent crimes may sound mindless, but they are informed by a primitive evolutionary logic. The mugger who kills for $1.79 is not getting much for his efforts, yet the general strategy of theft can pay off in the long run in terms of acquiring goods. Drive-by shootings may seem senseless, but they help establish dominance and status in the neighborhood. And while a barroom brawl over who’s next at the pool table may sound to you like fighting over nothing, the real game being played has nothing to do with pool.

From rape to robbery and even to theft, evolution has made violence and antisocial behavior a profitable way of life for a small minority of the population. The ultimate capacity for our antisocial misdeeds can be understood with reference to evolutionary biology. And it is from fundamental evolutionary mechanisms that genetic differences among us have come into play and shaped the anatomy of violence.

We think of aggression today as maladaptive and aberrant. We give heavy legal sentences to violent offenders to deter them and others from committing such crimes, so surely it cannot be viewed as adaptive. But evolutionary psychologists think differently. Aggression is used to grab resources from others, and resources are the name of the evolutionary game. Resources are needed to live, reproduce, and care for offspring. There is an evolutionary root to actions that run the gamut from bullies threatening other kids for candy to men robbing banks for money. And aggression—more specifically defensive aggression—is also important in warding off others who may wish to steal our precious resources. Bar fights help establish a pecking order of dominance and power, helping to put down rivals in the eyes of desirable women and other potential competitors. The mating game for males is about developing desirable status in society. Gaining a reputation for aggression not only increases status in one’s social group and allows more access to resources but also deters aggression from others. And that is true whether we are talking about a child in a playground or an inmate in a prison.

From a chubby-faced baby to a crooked-faced criminal, there is a development and unfolding of antisocial behavior predicated on biology and a cheating strategy to living out life. As a tiny kid, you took what you wanted without a care. All that mattered in the world was you and your selfish desires. You may have forgotten those days, but in that untamed, uncivilized period of your life, you were standing on the threshold of a life of crime.

Of course culture quickly took care of that. You were taught by parents, and maybe your older siblings, the rules of social behavior—“Don’t hit your sister,” “Don’t take your brother’s toys”—and your evolving brain began to slowly learn not just that there were others in the world, but that selfishness was not always a wise guiding principle on life’s long, arduous journey. You never exactly gave up on looking out for yourself and what was good for you, but at least you began to take into account others’ feelings and to express appropriate concern for others at appropriate moments—at times genuinely, and perhaps at other times disingenuously. But is there more to explaining antisocial behavior than the presence or absence of familial socializing forces?

There is. The thesis that really challenges our perspective on ourselves and our evolutionary history first appeared in 1976, in a radical book called The Selfish Gene, by Richard Dawkins.6 I’ll not forget this book, or Richard Dawkins, for that matter. As an undergraduate I had one-on-one tutorials with him on evolutionary theory. They were thrilling lessons on the all-embracing influence of evolution on behavior, and they led me to start thinking of violence and crime in evolutionary terms.

The central thesis in his landmark book was that “successful” genes are ruthlessly selfish in their struggle for survival, giving rise to selfish individual behavior. In this context, human and animal bodies are little more than containers, or “survival machines,” for armies of ruthless renegade genes. These machines plot a merciless campaign of success in the world, where success is defined solely in terms of survival and achieving greater representation in the next gene pool. However, the gene is the basic unit of “selfishness” rather than the individual. The individual eventually dies, but selfish genes are passed on from body to body, from generation to generation, and potentially from millennium to millennium.

It all boils down to how “fit” you are. Not so much whether you can run a marathon or how much you can lift, but how many children you can produce that are yours. The more kids you have that are genetically yours, the more copies of your genes there will be in the following gene pool. That, and only that, is success in the gene’s-eye view of the world. If more lofty perspectives come to mind when you contemplate the meaning of “success”—like doing well in school, having a great job, or writing a book—then consider this: your gene machine has been built to generate these fanciful ideas to maliciously motivate you into gaining status and resources that will translate into reproductive success. It’s a genetic con.

As a male you can maximize your genetic fitness in one of two ways. One, you can invest a lot of parental effort and resources into just a few offspring. You put all your eggs into a small basket, nurturing and protecting a couple of kids, ensuring their survival into full maturity, and even helping them look after their own children. Alternatively, you can put all your eggs, or rather sperm, into a lot of baskets. Here you maximize the number of your offspring without really doing very much to support them, spreading your parental effort more thinly.

A male can much more easily adopt this latter reproductive strategy of high offspring–low effort if he “cheats” on his many female partners by misrepresenting his ability to acquire resources and his long-term parenting intentions. Mate support and resources are critical for women. Once fertilized, females are largely lumbered with their progeny. They make the bigger investment in raising the child, so they are on the lookout for men who can come up with the goods, and will commit to long-term support.

So fitness—an organism’s ability to pass on its genetic material—is central to the evolution of all behavior and the driving force behind selfishness. Certainly in the animal world, it is easy to see how antisocial and aggressive behaviors have evolved. Animals fight for food and they fight for mates. And whether we like it or not, it’s not too much of a stretch from the animal kingdom to us humans. The temptation to “cheat”—whether it is not sharing resources after having accepted them from others or manipulation of others to selfishly acquire resources—is always there.

But surely we humans are different from animals. We have a strong capacity for social cooperation, altruism, and selflessness. Reciprocal altruism has indeed evolved because in the long run it benefits the performer. It ultimately pays you to help save a stranger if that stranger will reciprocate your help in the future, and save your life.7 Today, by and large, we live in a world populated by reciprocal altruists. And yet, at the same time, reciprocal altruism can itself give rise to “cheating.” If you accept acts of altruism from others, but fail to reciprocate in the future, you’re cheating. There is room for a bit of cheating—truth be told, we all do it from time to time. But a small number of us cheat a lot—and in this group we find the psychopath. The trouble for psychopaths, however, is that sooner or later they get a bad reputation. People stop helping them out, and potential mates pass them over. In this scenario the psychopathic cheat is on a downward spiral.

Fortunately for the psychopath there is a slippery way out. After he’s been spotted by reciprocal altruists he leaves this social network and migrates to a new population, where he can begin to fleece a different set of unsuspecting victims. It’s easy to see in this analysis, therefore, how a small minority of antisocial cheats could survive in a world largely populated by reciprocal altruists. The proportion of cheats within any population would have to stay relatively small—cheats lose out when they meet one another—but otherwise cheats can survive, as long as they are prepared to tough it out and take a few hits before moving on.

Such a scenario would lead to the prediction that these hard-core antisocials drift from population to population. Consistent with this prediction, the modern-day psychopath has been characterized as an impulsive, sensation-seeking individual who fails to follow any life plan, aimlessly drifting from person to person, job to job, and town to town.8 Probably the best assessment tool for psychopathy—the Psychopathy Checklist—makes reference to the psychopath’s short-term plans and goals, nomadic existence, frequent breaking off of relationships, poor parenting, moving from one place to another, frequent changes of jobs and addresses, and parasitic lifestyle.9 The “pure” cheat strategy is therefore entirely consistent with present-day psychopaths who manifest a nomadic lifestyle.

In any game there is more than one winning strategy, and that holds true in the game of reproductive fitness. Reciprocal altruism can pay for most, and for a few the psychopathic cheating strategy wins out. We’ll now turn to how certain environmental conditions could nudge some whole societies to become altruistic or selfish, and how psychopathic behaviors could have evolved. Given certain environmental circumstances, whole populations of cheats could evolve, and studies of primitive societies provide some interesting clues on the evolution of psychopathic behavior.

Environmental conditions vary greatly across the world, and throughout prehistory behaviors have evolved in an adaptive response to changing environmental circumstances. Building on this notion, some anthropological studies lend support to the idea that whole populations can develop an antisocial trait. The main method of these studies has been to compare cultures differing in antisocial conduct on ecological and environmental factors that give rise to different reproductive strategies and social behaviors. If certain ecological niches are associated with certain types of behavior, this could support the notion that what we call antisocial traits could be advantageous in cultures found in certain environments. Such cultures could have jump-started the evolution of antisocial, psychopathic-like lifestyles.

When comparing, for instance, the cultures of the !Kung Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert in Southern Africa and the Mundurucú villagers in the Amazon Basin, anthropologists have found that the strikingly different environments they inhabit correlate with altruistic and antisocial behavior, respectively.10 The !Kung Bushmen live in a relatively inhospitable desert environment. Due to the extremely difficult living conditions, cooperation is prized. Men need to hunt together in search of food, and game is shared in the camp.11 There is also a high degree of parental investment in children, who are highly supervised and weaned gradually. Because of that high parental investment, fertility is relatively low. A disruption of a pair bond by either partner could have fatal consequences for the offspring, who are highly dependent on parental care. The personal characteristics adapted to the !Kung’s environment are good hunting skills, reliable reciprocation of altruistic acts, the careful choosing of mates, and high parental investment in offspring. This personality profile is clearly more aligned to altruism than to cheating, a trait that is argued to be in part an adaptation to an inhospitable environment.

In contrast, the Mundurucú are low-intensity tropical gardeners living in a relatively rich ecological niche along the Tapajós and Trombetas Rivers in the Amazon basin. Everything grows there, and life is relatively easy. In an interesting role-reversal, women carry out most of the food production.12 This environment makes for a very different way of life and a different male personality profile. The relatively greater availability of food frees males to engage in male-male competitive interactions centered around politics, planning raids and warfare, gossiping, fighting, and elaborate ritual ceremonies. Occasionally they engage in hunting game that they trade for sex with the village women. Men sleep together in a house separate from the women, whom they hold in disdain. Indeed, females are viewed as sources of pollution and danger. Males in the Gainj tribe, low-intensity gardeners in the highlands of New Guinea, also view sexual contact with women as dangerous, especially during menstruation.

In contrast to the !Kung, Mundurucú mothers provide little care to their infants once they are weaned, and these children must quickly learn to fend for themselves. Mundurucú men play a minimal role in caring for their offspring. Personal characteristics of the successful Mundurucú male in this competitive society consist of good verbal skills for political oratory, fearlessness, skill at fighting and carrying out raids, bluff and bravado to avoid the risk of battle, and the ability to manipulate and deceive prospective mates on what resources he can offer to maximize offspring. Furthermore, he should not be gullible, since belief in the folklore regarding the dangers of sex and women as a source of pollution would not foster the passing on of one’s genes.13

Similarly, for females living in a social context of low parental investment, those who can manipulate their menfolk by deception over an offspring’s paternity, exaggeration of requirements, and resistance to the development of monogamous bonds are the most successful. The Mundurucú’s way of life is then more associated with a cheating, antisocial strategy than with reciprocal altruism. Figure 1.1 summarizes the key features of these two societies and how they stand in sharp contrast.

Figure 1.1 Contrasting environmental features of two societies that shape different personality traits

The nature of the Mundurucú’s social environment clearly favors the expression of aggressive, psychopathic-like behavior. Certainly when one considers the fact that the Mundurucú were in the past fiercely aggressive headhunters, this parallel to psychopathy becomes clearer. Intriguingly, many of the features of the Mundurucú have parallels with features of psychopathic behavior in modern industrialized societies.14 For example, psychopaths show lack of conscience, superficial charm, high verbal skills, promiscuity, and lack of long-term interpersonal bonds.15 While these traits are advantageous in the Mundurucú environment, they are clearly disadvantageous in the milieu of the !Kung Bushmen, which demands high male parental effort, reciprocal altruism, and monogamous relationships.

The Yanomamo Indians in the tropical rain forests of northern Brazil and southern Venezuela provide another parallel culture to the Mundurucú. With a total population of about 20,000, they live in villages that can range in size from 90 people to about 300. As with the Mundurucú, they subsist on plants and vegetables and only need to do about three hours of work a day. They too live in a rich ecological niche.

Napoleon Chagnon, in his intensive anthropological studies on the Yanomamo, has documented a number of striking features of this culture.16 They’ll break rules when it’s in their interest. They participate in the forcible appropriation of women. They call themselves waiteri—meaning “fierce.” And they are indeed both fearless and highly aggressive. Boys are socialized into acts of aggression from a surprisingly young age, with their “play” consisting of throwing spears and shooting arrows at other boys. Initially they are scared by this initiation into violence, but soon they come to revel in the adrenaline rush that the mock battles provide.

To give you a perspective on their level of aggression, 30 percent of all male deaths among the Yanomamo are due to violence, an astonishing level. If you think the United States is a violent society, consider that 44 percent of all Yanomamo men over the age of twenty-five have killed someone, thus achieving the status of being a unokai. Some kill more than once, and one unokai had killed sixteen times. The source of the killing in the majority of cases is sexual jealousy—exactly what you’d expect from an evolutionary perspective and a species whose females make the greater parental investment. They also conduct raids on other villages for revenge killings that can take up to four days to execute, involving from ten to twenty men in the raiding party.

From our perspective on the evolution of violence, however, the most interesting element of the Yanomamo is what happens to unokais, the men who kill. They have an average of 1.63 wives compared with 0.63 wives of men who do not kill. The unokais have an average of 4.91 children compared with an average of 1.59 children for non-killers. In terms of reproductive fitness, serious violence pays handsomely in two critical resources. First, lots of kids. Second, lots of wives to look after them. We can see how planned violence and the lack of remorse over killing others have been rewarded in the unokais’ society. These are precisely the features of Western psychopaths,17 who also commit more aggressive acts than non-psychopaths, and are more likely to commit homicide for gain.18

Inevitably, Western society does not condone such violence. We hardly applaud and reward people who kill others. Or do we? With significant pomp and ceremony we decorate and reward soldiers who have taken significant risks to kill others in warfare. Crowds cheer wildly as boxers punch each other senseless in a sport that we know results in brain damage. We certainly revel in kung fu movies or other film genres when the good guy beats the living daylights out of the bad guy.

Whatever our cultivated minds may publicly say about the senselessness of warfare, do not our primitive hearts still thrill to the drums of combat? Is this why we enjoy sports competitions, to watch the dominant winner end up on top? Is that what gives us the vicarious thrill and excitement of seeing someone win a gold medal at the Olympics? Or when a violent tackle occurs in a football game? Our present-day cultured minds weave an alternative story to explain the feeling—we just love sports, that’s all. But why? Isn’t it because selection pressures have built into us a mechanism to carefully observe who ranks where, empathic skills to imagine ourselves as a winner, basking in that reflected glory, giving us that “feel-good” mood and a desire to emulate such achievements?

Mundurucú women are clearly attracted to men around them who kill. Have you ever wondered why seemingly sensible, peaceful women want to marry serial killers in prison? Their primitive heartstrings are being plucked by the siren’s call of the serial-killer status. They yearn to be with a strong male, even when their modern minds might logically object. At a milder level we have a morbid fascination with true crime. Something attracts us to violence. That evolutionary pull may even have explained why you bought this book.

Part of the attraction we have to violence is that when executed in the right place and the right time, it’s adaptive—even today. The vestiges of our evolutionary backgrounds persist, far more than we care to imagine. Let’s take this a step further into the here and the now to examine in what specific situations aggression is adaptive, and what aspects of crime can be explained from an evolutionary perspective.

I mentioned earlier that people in general are a hundred times more likely to be killed on the day they are born than on any other day.19 Murders of children and adolescents are most likely to occur in the first year of life.20 And within that year, eighteen times more children are murdered on the day they were born than on any other day.21 In 95 percent of these cases, the babies were not born in a hospital. They are mostly the product of undesired, unplanned pregnancies. They are battered to death (32.9 percent), physically assaulted (28.1 percent), drowned (4.3 percent), burned (2.3 percent), stabbed (2.1 percent), or shot (3.0 percent).22 It all flies in the face of the exhilaration that most couples experience on the day of their child’s birth. But an explanation for this seeming contradiction can be found within the layers of evolutionary psychology theory.

Indeed, once we step across the threshold of the home, there are facts that seem to fly in the face of an evolutionary perspective on violence. For example, people are more likely to be killed in their home by a family member than by a stranger. How can that make sense from an evolutionary standpoint? Don’t we expect solid protection of everyone at home to ensure that the family’s genes are passed on to future generations? Martin Daly and Margo Wilson are two Canadian evolutionary psychologists who have done more than anyone else to resolve enigmas like this and to further demonstrate the power of an evolutionary psychological perspective on violence.

What they demonstrated was an inverse relationship between the degree of genetic relatedness and being a victim of homicide. So the less genetically related two individuals are, the more likely it is that a homicide will take place. For example, in Miami, 10 percent of all homicides were the killings of a spouse—a family killing—but of course, spouses are almost always genetically unrelated. In fact, Daly and Wilson found that the offender and the victim are genetically related in only 1.8 percent of all homicides of all forms.23 So 98 percent of all homicides are killings of people who do not share their killer’s genes.

Selfish genes in their strivings for immortality wish to increase—not decrease—their representation in the next gene pool. Hence this inverse relationship between genetic relatedness and homicide. On the other hand, if you are living with someone not genetically related to you, you are eleven times more likely to be killed by that unrelated person than by someone genetically related to you.

Stepparents are a particularly pernicious case in hand, a fact captured in countless myths and fairy tales. Remember the grim story of Hansel and Gretel, whose wicked stepmother badgered their natural father into leaving his children deep in the woods to die of starvation? Or Sleeping Beauty’s evil and vain stepmother, who ordered a hunter to take her into the woods and slaughter her? Recall Cinderella’s cruel stepmother? Actually, the reality is so potent that our childhood lives are full of images of mean stepmothers—real or imaginary—almost as an eerie warning call for us to be on our guard.

Did you grow up as a child with a stepparent? If you did and you survived unscathed, you’ve done pretty well. In England, only 1 percent of babies live with a stepparent,24 and yet 53 percent of all baby killings are perpetrated by a stepparent.25 Data from the United States show a similar pattern—a child is a hundred times more likely to be killed as a result of abuse by a stepparent than by a genetically related parent. If we look at child abuse, we see the same thing. Stepparents are six times more likely to abuse their genetically unrelated child under the age of two than genetic parents.

It’s a finding that makes you wonder if in cases of death from abuse by someone thought to be the biological parent, that person may not be the genetic parent after all. In cases where the children and the father believe that they are genetically related, it is estimated that in about 10 percent of cases the father is not the genetic father. Could at some subconscious, evolutionary level the father sense genetic unrelatedness and pick on the unrelated child? Such abuse would be a paternal strategy to push that child out, to minimize the resources given to him, and instead maximize resources for other, genetically related children. We know that stepparents sometimes selectively abuse their stepchildren, sparing the children in the family who are genetically related to them.26

Such actions of some stepparents can thus be comprehensible from an evolutionary perspective. But more perplexing are parents who kill children they are genetically related to. How can evolutionary theory come to grips with these killings?

The basic concept to remember here, if you think back to your own parents when you were growing up, is that they likely worked hard to raise you—and don’t they just let you know it sometimes! They worked their fingers to the bone and sacrificed much for your future betterment. Okay, so that’s par for the course when it comes to looking after your own genes. But also bear in mind that the longer a child lives, the more her parents invest in her. But suppose someone’s genetic parents change their minds about their investment? If they do, they ought to do it early on before they waste more energy. And that’s exactly what we see.

Take a look at the top graph in Figure 1.2, showing the age at which a child will be killed by its mother if she is indeed going to kill it. It shows homicides per million children per year averaged over a period from 1974 to 1983 in Canada. You’ll see that the peak age for killing is in the very first few months of that little baby’s life.27 After that time, the homicide rate drops dramatically and keeps on declining right throughout adolescence. Soon after birth the mother bails out on her own baby. Maybe she wants to move on. Maybe her mate has moved out and she knows she’s better off without this baggage, better able to attract a new mate. Whatever the reason, there is a strong age effect to be explained.

Figure 1.2 Age at which Canadian children are murdered by their mother, father, and others

I think I know what you’re thinking. Some mothers just after birth have puerperal psychosis. They sink into a very deep depression with psychotic features, and amid their despair and madness they may kill their kid. Fair point, because this condition does affect about one in a thousand mothers after birth. But the response lies in data shown in the middle graph of Figure 1.2. You can see exactly the same infanticide age curve for fathers.28 If they are going to kill, it’s again in the very first year of life, when their investment is minimal. Fathers don’t give birth and so they don’t suffer from puerperal psychosis. Consequently, this form of psychosis cannot explain the maternal data in Figure 1.2.

Maybe it’s all that screaming and sleeplessness that comes in the first year that drives the parents to kill their offspring. It’s not a bad explanation. But tell me, if you have ever had a child, what was the worst year—that first year when they were innocently crying, or the teenage years, when they were yelling in your face? Or, if you haven’t had kids, at what age do you think you were hardest on your mother and father? I’d go for the teenage years any day, and yet look at the rate at which parents kill their teenagers—that’s strangely when children are least likely to get killed by them. But if you are a teenager don’t push your luck with your parents, as a few do get killed.

Don’t push your luck with anyone else either. You’ll see from the bottom chart in Figure 1.2 that when we look at the killings of kids by nonparents, rates are low early on but shoot up in the teenage years. Why? Because that’s the age when renegade youths are cruising the streets looking for fun and meeting up with strangers. It’s also when children are less closely supervised by their parents and when risk-taking is highest.

There are other environmental triggers that from an evolutionary perspective help explain why parents might kill their young offspring. A baby may be born with a congenital abnormality that reduces the odds of survival or reproduction, or it may have a chronic illness that saps parental resources. Even with normal offspring, if food is short it may pay the parents in terms of genetic investment to spend scarce resources on the survival of an older sibling closer to the age of maturity and independence, rather than spreading the butter too thinly, trying to support both the newborn and the older sib.

Even if there is no older sibling, killing the baby could make evolutionary sense. In some bird species where both parents forage for their offspring, the death of one parent can result in the other parent abandoning the offspring. The load is just too hard to bear, and it’s better for the remaining parent to look after number one and try again in the reproductive success game. Don’t we sometimes get a sense of that in stories of young mothers abandoning their babies? We tend to interpret their actions as due to social processes like immaturity, shame, or teenage impulsivity. Shame may be the superficial explanation, but at a deeper level the underlying cause may be cold-blooded maximization of reproductive success. The negative emotions and behaviors that we attribute to the mother in trying to explain the homicide may not be the whole story. The selfish genes inside the teenage killer mom may be the ultimate source of such callous, cold-blooded behavior.

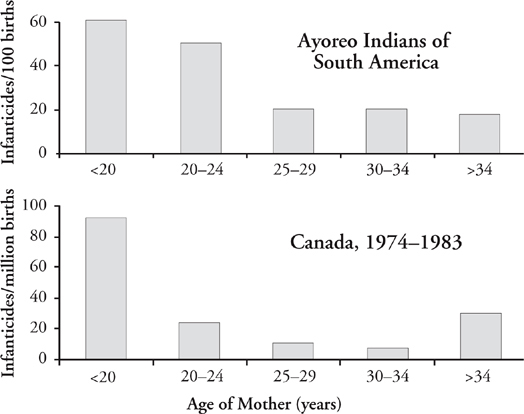

Figure 1.3 Age of mother when she kills her own child

There’s one more point to make about parents killing their children: how old the mother is when she kills her own child. The upper graph of Figure 1.3 shows the rate of child homicides as a function of the mother’s age among the Ayoreo Indians of South America. It’s highest when the mother is under the age of twenty, and it goes down after that. Why would that be? The mother is more fertile when she’s younger—and more attractive in drawing a desirable mate to her. The older she is, the more it makes sense to hold on to her long-term genetic investment because it’s harder to make up the loss at this later point in her reproductive life.

And it’s not just the Ayoreo Indian mothers who kill at an early age. If you look at Canadians in the lower half of Figure 1.3, you’ll see the same age-to-murder curve.29 Your mother is much more likely to kill you when she is still young. Being young, her reproductive years lie ahead of her and she has more options. Perhaps the current biological father has abandoned her. Perhaps she has a new suitor who can promise her more. Either way, the selfish gene ticking away inside her signals that it’s time to dump her baggage and go on vacation looking for a new mate.

Put all of this together, and what comes across is that genetic relatedness, fitness, and parental investment are intriguing reasons for why adults kill their kids. Patterns of homicide can indeed be clarified by the application of sociobiological principles. Of course there are other processes that help explain why a parent kills his or her child—it’s not just the selfish gene at work. Yet whether we are aware of it or not in the twenty-first century, the machinations of deep evolutionary forces are laboring away down in the depths of our humanity, forging devious tools to maximize our genetic potential. And behind those closed doors in the family home, those forces don’t end with killing your kids.

Is rape an act of hate? A malicious and derisory act against women condoned by a patriarchal society where men attempt to control and regulate their womenfolk? Or can this act of violence be partly explained by evolutionary psychology?

We can view the rape of a nonrelative as the ultimate genetic cheating strategy. Rather than striving to accrue resources to attract a female and investing years in the upbringing of their offspring, a male can cut through this tedious process in the twinkling of an eye. He just needs to rape a woman. Men have hundreds of millions of sperm that are always at the ready to inseminate a woman. The sex act is quick. And the male can immediately walk away, never to see that woman again. He knows that if pregnancy does occur, there is a decent chance that the female will care for their joint progeny. His selfish genes have reproduced.

How often will a rape result in a pregnancy? This was estimated in one study of 405 women aged twelve to forty-five who had suffered penile-vaginal rape. The total base rate was 6.42 percent, which was twice as high as the 3.1 percent base rate for unprotected penile-vaginal intercourse in consensual couples. After correction for the use of contraceptives, the pregnancy base rate from rapes was estimated at 7.98 percent.30 The rates of pregnancies from rape can only be estimates because paternity is not investigated with definitive DNA evidence. Some women could “invent” a rape as a cover-up for an unwanted pregnancy. However, other studies have also reported higher rape-pregnancy rates than consensual-sex-pregnancy rates. It is nevertheless surprising. If we accept the findings, why would rape be more likely to result in a pregnancy?

One conceivable hypothesis is that rapists are more likely to inseminate fertile women. Rapists select their victims, and we certainly know that they are far more likely to select women at their peak reproductive age than other women.31 Furthermore, putting age aside, the possibility that a rapist may be more visibly drawn to women who are the most fertile is not impossible. Females with a smaller waist relative to their hips are viewed as more attractive in many cultures throughout the world. This smaller waist-to-hip ratio is also associated with increased fertility as well as better health.32 Consequently, male rapists could in theory select a more fertile female, consciously or subconsciously, based on how she looks.

Not all rapists choose victims they find attractive. It can even be the other way around. When I worked with prisoners in England, one rapist told me that he specifically picked out unattractive women to rape. Why would he do this? His argument was that an unattractive woman does not get enough sex, so it’s okay to give her the sex that she really wants. This is just one example of a number of cognitive distortions that some rapists have.33 Their perverted belief is that women actually enjoy the act of rape and interpret it as the experience of a lifetime—their ultimate sexual fantasy coming true.

Ideas like this may be inadvertently fueled by the fact that some women when raped actually achieve orgasm, even though they may strongly resist and are traumatized by the attack.34 True prevalence data are hard to come by because rape victims understandably are embarrassed to admit that they achieved orgasm during such a disgraceful violation. Clinical reports place the rate of the victim experiencing orgasm at about 5 to 6 percent, but clinicians also report that they suspect the true rate to be higher. This may well be the case, because research reports document that physiological arousal and lubrication occurs in 21 percent of all cases. Why would that happen? Because in half the cases, the date-raped woman was actually attracted to the perpetrator before the act. Orgasm and the associated contractions are thought to facilitate conception by contracting the cervix and rhythmically dipping it into the sperm pool. This admittedly has a modest effect, as sperm retention is increased by only approximately 5 percent with orgasm.

Clearly, conception does not require orgasm,35 so we cannot place too much weight on the physiological arousal of some women during rape as a prelude to pregnancy. Nevertheless, the fact remains that rapists generally select their victims and appear to consciously or subconsciously select more fertile women. This selection strategy would explain the purported increased pregnancy rate in rape victims and can be viewed in an evolutionary context. If a man is going to take risks raping a woman, the strategy would be to pick the fertile one and enhance one’s inclusive fitness.

There are, of course, risks associated with this particular cheating strategy. The male could suffer physical injury. Worse, he could be detected and beaten. Throughout much of human history rapists have been alienated or killed. In modern times he would be thrown into prison alongside psychopaths and murderers, where as a sex offender he is at high risk for being beaten and raped himself. So evolutionary theory argues that there is a subconscious cost-benefit analysis at work—weighing the potential costs resulting from detection against the benefits of producing a child. Dominant men with resources can already attract mates, so one might expect that the cost-benefit analysis might tip the scales in favor of rape when the perpetrator has relatively fewer resources. In support of this prediction, rapists are indeed more likely than non-rapists to have lower socioeconomic status, to leave school at an earlier age, and to have unstable job histories in unskilled occupations.36

We can question evolutionary theory because it can be too all-encompassing; we cannot take it too far in explaining violence. Drug cartels in Colombia and the availability of handguns in the United States contribute significantly to explaining why these countries today have high homicide rates, and yet these influences lie outside the domain of evolutionary theory. I think you would admit that an evolutionary perspective can help explain facts about rape in quite a compelling way. While women of any age can be raped, we’ve noted that men are much more likely to rape women of reproductive age.37 Interestingly, women of reproductive age who are raped experience more extreme psychological pain than younger or older women. This has been interpreted as an evolutionary learning mechanism that focuses these women’s attention on avoiding contexts where they could be raped and have their overall reproductive success reduced.38 At another level, we know that men find it far easier than women to have sex without concomitant emotional involvement. Why? Because they do not need to hang around after the sex act is over. In contrast, from an evolutionary perspective, women need a long-term commitment from their male mate to help rear any child that might result from their union, and so they have more need of an emotional, personal relationship. Finally, men very rarely kill the women they rape; although they have the potential to kill, they want their offspring to survive.

But what about rapes that occur between partners in a marriage or other long-term relationship? Between 10 percent and 26 percent of women report being raped during their marriage.39 How can this be viewed through evolutionary lenses?

A great deal of research has documented that both physical and sexual violence perpetrated by men in a relationship is fueled by sexual jealousy.40 Infidelity is very distressing for both males and females, but men and women differ in terms of what causes these distressing feelings. Jealousy is the primary motive for a husband to kill his wife in 24 percent of cases, compared with only 7.7 percent of cases in which the wife kills her husband.41

Think about this yourself in your own life. Imagine that you are deeply involved in a serious romantic relationship. Now you discover that your partner has become very interested in somebody else. Now imagine two different scenarios. In the first, your partner has a deep emotional—but not sexual—relationship with the other person. In the second scenario imagine that your partner has enjoyed a sexual—but not emotional—relationship with the other person. Which one of these scenarios would upset you most?

David Buss, of the University of Texas at Austin, who conducted research into this question, found that men were twice as likely to find the second scenario the most upsetting—it’s the sexual relationship that bothers them, not the emotional relationship. While men find the sexual infidelity most distressing, women in contrast find the emotional infidelity most distressing. These sex differences were still true for scenarios where both forms of infidelity occurred. These findings on Americans also hold true in South Korea, Japan, Germany, and the Netherlands.42 Men and women in different cultures differ in just the same way. Relatedly, men have been reported to be better than women in their ability to detect infidelity43 and are more likely to simply suspect infidelity in their female spouses.44

What can explain the replicable sex difference in the green-eyed monster of jealousy? The explanation is that men are more distressed about infidelity because they could end up wasting resources and energy in raising a child genetically unrelated to them. Women, on the other hand, are concerned about infidelity because it means they may lose the protection, emotional support, and tangible resources provided by their partner. In both cases, resources are again the driving force behind our intense emotional feelings, but in subtly different ways.

These findings on jealousy now render for us a perspective on why male sexual jealousy can fuel so much physical and sexual aggression in partner relationships. Men who force sex on their spouses are found to have higher levels of sexual jealousy than men who do not.45 Men may use violence as a mechanism to deter future defection by their female partner.46 A woman will think twice about having another dangerous liaison if it results in her being battered nearly to death.

Yet this gives us even more food for thought at the evolutionary dining table, where resources and reproduction are the vittles. Why would a male partner rape his female partner in response to an infidelity? You might say it’s simply an act of revenge. But lurking under the surface of this social argument may be a deep-rooted evolutionary battle that influences violence and crime—sperm wars.

If a woman did have sex with another man, from an evolutionary standpoint her partner will want to inseminate her as quickly as possible. His sperm will then compete with sperm from the unknown rival in a battle to access the woman’s egg. Furthermore, by getting his sperm into her reproductive tract at regular intervals during a potentially prolonged period of suspected sexual infidelity, he puts off the chance that any foreign sperm will be successful in getting to that prized egg. At regular intervals he can top off his sperm in her cervix by injecting 300 million warriors. Half of these will end up in a flow-back that comes out of the vagina and onto the bed sheets, while the rest have further work to do, beginning their arduous journey for the next few days toward the egg in competition with someone else’s sperm.47

In the genetic cheating game there’s no stopping men. Women certainly have a hard time of it. They get raped by strangers. They get raped by friends. They get raped by their partners. Yet women are not always the victims. We’ll see that they have their own subtle and conniving ways of waging war to promote their selfish genetic interests.

Let’s start with men as warriors. We all know that men are more violent than women. It’s true across all our human cultures, in every part of the world. The Yanomamo are not the only group whose men gather together to conduct killings in other villages. There has never in the history of humankind been one example of women banding together to wage war on another society to gain territory, resources, or power.48 Think about it. It is always men. There are about nine male murderers for every one female murderer. When it comes to same-sex homicides, data from twenty studies show that 97 percent of the perpetrators are male.49 Men are murderers.

The simple evolutionary explanation is that women are worth fighting for. They are the valuable resource that men want to get their hands on. Women bear the children, worry about their health, and make up the bulk of the parental investment. This is also true throughout the animal kingdom. Where one sex provides the greater parental investment, the other sex will fight to access that resource. Evolutionary theory argues that poorer people kill because they are lacking resources, an argument shared in common with sociological perspectives. And the reason men are overwhelmingly the victims of homicide is because men are in competition with other men over those resources. Men who murder are also about twice as likely to be unmarried as non-murdering men of the same age.50 They have a greater need to get in on the reproductive act, and are willing to take warrior risks. For men one of the underlying causal currents for violence is competition for resources and difficulties in attracting females into a long-term relationship.

Let’s also not forget warrior men in the home context. Violence can be used to dominate, control, and deter a potentially unfaithful spouse. Just as lions who take over a female from another male will kill the young and inseminate the lioness, aggression toward stepchildren is a strategic way of motivating the unwanted brood to move on and not take up resources needed for the next generation bred by the stepfather.51

Consider also that sex differences in aggression are in place as early as seventeen months of age.52 Boys are toddler warriors. This might be expected from an evolutionary perspective that says males need to be more innately wired for physical aggression than females, to prepare them for later combat for resources. Seventeen months is a bit too young for sex differences to be explained in terms of socialization differences. Social-learning theories of why males are more aggressive run into trouble with the fact that the gender difference in aggression, which is in place very early on, does not change throughout childhood and adolescence.53 Socialization theory would instead expect sex differences to increase throughout childhood, with increased exposure to aggressive role models, the media, and parenting influences, but they do not. Consider also that violence increases throughout the teenage years to peak at age nineteen. This is consistent with the notion that aggression and violence are tied to sexual selection and competition for mates, processes that peak at approximately this age.54

While male warriors perpetrate most violent offending, females can be aggressive too, in a surreptitious sort of way. On balance, however, women tend to be worriers rather than warriors for reasons that evolutionary psychology can explain.

Women have to be very careful in their use of aggression and sensitive in their perception of it because personal survival is more critical to women than to men. That’s because they bear the brunt of child care and their survival is critical to the survival of their offspring. In unison with this standpoint, laboratory studies show that women consistently rate the dangerousness of an aggressive, provocative encounter higher than men do.55 Women are also more fearful than men of situations and contexts that can involve bodily injury.56 They are more likely to develop phobias of animals and medical and dental procedures. While they are more averse to physically risky forms of sensation-seeking, they are not averse to seeking forms of stimulation that do not involve physical risk—things like novel experiences through music, art, and travel.57 Women also have a much greater concern over health issues than men. They rate health as more important and also go to the doctor more often.58

Fearfulness of bodily and health injury is therefore the psychological mechanism that evolution has built into women to protect them from death, helping to ensure the survival of their young. Thus, the fact that women are far less physically aggressive than males, in almost all arenas in life and in all cultures across the world, can be explained by an evolutionary principle.59 Women are more averse to physical aggression than men because of its reproductive impact. Yet what would happen if we lowered the risk of bodily injury from aggression?

In this case a different scenario gets played out. John Archer, of the University of Central Lancashire, has documented that the sex difference in aggression is highest at the most severe levels of physical aggression, is much lower when it comes to verbal aggression, and is negligible with “indirect aggression.”60 Essentially, females are much more likely to engage in aggression when the cost to them in terms of physical injury is minimal. Indeed, Nicki Crick, at the University of Minnesota, has argued that females are more likely than males to engage in this “indirect” or “relational aggression,” which takes the form of excluding others from social relationships and group activities and damaging their reputation in their peer groups—gossiping, spreading rumors, humiliating the individual. Ladies, do you recall this from your teenage days or experience it now in your current working life?

So rather than being physically violent, women take a more passive-aggressive strategy. They compete in terms of physical attractiveness—the quality most desired by men, who use it as a guide to fertility—and allow access to the man with the most resources. David Buss argues that women are much more likely to call their competitors ugly, make fun of their appearance, and comment on their fat thighs.61 Women attempt to ruin their rivals’ reputation by saying they have a lot of boyfriends, sleep around a lot, and are sexually promiscuous.62 Men don’t like hearing that from an evolutionary standpoint because if they get together with such a woman, they may end up rearing some other man’s offspring. Consequently, such slanderous gossiping is an effective verbal-aggression strategy for women to use that does not run a high risk of physical harm.

We’ve seen here how violence and aggression is based partly on primeval evolutionary forces from the past. While reciprocal altruism can rule the day, antisocial cheating can also be a successful reproductive strategy, especially when psychopathic cheats migrate from one population to another. I’ve tried to illustrate how stealing, rape, homicide, infanticide, spousal abuse, and spouse killing can all be viewed from an evolutionary perspective. We’ve also seen anthropological examples of how different ecological settings could have given rise to either cheating or reciprocal altruist reproductive strategies. Males have evolved to use physical aggression to increase genetic fitness, while women have evolved to be concerned over their own health and that of their progeny, resorting to a safer form of relational aggression to protect their genetic interests. While evolutionary theory cannot, by any means, explain all violence, it at least provides us with a broad conceptual base with some degree of explanatory power.

The seeds of sin are rooted in our evolutionary past, the time when hominids formed social groups that shaped norms for helping behaviors—norms that a minority could break. Genes are the name of the evolutionary game, and therein lies an important implication for us. Talk about evolution, and by necessity we invoke genes. I’ve argued that antisocial, psychopathic behavior has evolved in some of us as a stable evolutionary strategy. In this ruthless, selfish context, rape is viewed not simply as a mechanism by which men exert power and control over women, as many feminists would argue. It is also the ultimate evolutionary cheating strategy—“love” them and leave them. Inseminate as many women as you can, then leave them to get on with the hard work of raising Cain and reproducing your bad genes. So the next step we will take in tracing the anatomy of violence is to understand the genetic basis to brutishness, and which individual genes stand out as our “usual” suspects.