11

“Manufactured News” and Michael Davitt’s Journalism in South Africa and Russia for William Randolph Hearst

Colum Kenny

In 1900 and again between 1903 and 1905 Michael Davitt, radical Irish nationalist and journalist, was commissioned as a foreign correspondent for the “yellow-journalism” US newspapers of William Randolph Hearst. Davitt (1846–1906) was a prolific writer.1 In addition to books, political tracts, and essays he wrote very many articles for newspapers in Ireland and elsewhere. He even launched and edited briefly his own labor weekly in England.2

But what of his style and purpose as a journalist? Davitt’s passionate reporting from the Russian empire for Hearst won him the gratitude of Jews internationally. His pieces on a pogrom in Kishineff (also Kishinev, today Chişinauŭ, Moldova) are said to have had a lasting impact on international perceptions of Jewish history. Yet, Davitt’s own position on anti-Semitism was somewhat ambivalent, and his journalism did not always reveal either this or other of his contradictions and conflicts of interest. This chapter explores Davitt’s assignments as a foreign correspondent in the context of his personal attitudes and motivations and with reference to journalism’s professional standards.

A Working Journalist and Politician

Many who know of Davitt see him as a Fenian and founder of the Land League, an association that promoted the interests of Irish tenant farmers. However, from the 1880s, he was also a correspondent for papers that included the New York Daily News, the Melbourne Advocate, London’s Pall Mall Gazette, and Dublin’s Evening Telegraph.3 His ambition to succeed Edmund Dwyer Gray as editor of the Irish Freeman’s Journal when the latter died in 1888 was dashed after Charles Stewart Parnell intervened in favor of a less radical choice, and so Davitt turned, for a while, to politics.4

In 1893, upon his election to the United Kingdom Parliament for Cork North-East, the standard parliamentary reference book described Davitt as “a journalist and political lecturer.”5 He had first trained as a printer. Although he had lost his right arm working in a Lancashire cotton mill at the age of eleven, Davitt managed somehow to become a skilled apprentice, deftly typesetting, as his astonished English employer attested publicly in 1863.6 As was often the case in the nineteenth century, Davitt used his training in printing to move over to the editorial side of journalism.

Davitt had particular expectations of professionalism. When he sailed to cover the Boer War in 1900, Davitt took a dim view of one drunken English correspondent on his ship. Davitt wrote that, “This war will tend to extinguish genuine war correspondents. The amateurs now in South Africa . . . will cover this branch of the journalistic profession with ridicule.”7 Later, in Russia, he condemned the English press for its “carnival of falsehoods.”8 As regards his own professional standards, one recent biographer has claimed that “there is no evidence to suggest that in his various journalistic commissions, Davitt was ever guilty of self-censorship, or of having tailored his reports to conform to the line taken by a particular paper.”9 But does he, in fact, merit quite such lavish praise?

Davitt seems to have been relatively well remunerated for some articles, but in general his journalism did not provide him with a substantial income. Moody refers to him “earning a modest and precarious livelihood by his exertions as a journalist and a public speaker.”10 His socialist friend Henry Hyndman wrote that “Davitt was always struggling against poverty and was very badly paid for the journalistic and lecturing work which he did, [but] he rarely or never complained of his lot.”11 Still, Davitt’s journalism was in demand and W. T. Stead, editor of the renowned British Review of Reviews, praised his dispatches from South Africa. Davitt’s pieces from Russia would win him international acclaim.

Nevertheless, Davitt’s articles for newspapers were generally excluded from that collection of his writings published in eight volumes in 2001. They were excluded because “Davitt was a working journalist. . . . The sheer volume of his journalism could not have been encompassed in this collection. Moreover, some of his journalism dealt with ephemeral issues, and other themes he reworked in his books.”12 Yet, journalism is not necessarily less accurate or less significant politically and intellectually than are other forms of observation, or less valuable as a source for historians. Memory or ideology may even render later “reworked” accounts of events less accurate or reliable than the proverbial “first draft of history” that is written for an imminent deadline.

South Africa 1900

In 1899 Davitt resigned his seat in Parliament in protest over the Anglo-Boer War. Like most Irish Catholic nationalists, he supported the Boers, notwithstanding their Protestant faith and the plight of native African populations in areas where the Boers settled. Irish nationalists regarded England’s continuing expansion into Boer South Africa, which was due in part to the discovery of valuable diamond mines there, as somehow analogous to its conquest of Ireland many centuries before.

Davitt wanted to see for himself how the Boers were faring and persuaded the Freeman’s Journal in Dublin to commission him to write some articles on the war. Boarding a ship at Marseilles, he received a cable from W. T. Stead telling him that William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal (soon to be retitled the New York American) would also take pieces from him.13 Stead was already a correspondent for Hearst, and he and Davitt were old friends. They were among the first to demand that Charles Stewart Parnell resign once the O’Shea scandal broke. In 1900 each would urge the other to stand for Parliament.14

One of Davitt’s greatest challenges in reporting on the Boer War was British censorship. The British effectively insisted on licensing any journalists within their sphere of influence, embedding them with British forces and censoring their copy.15 More recently, Potter has acknowledged that, during the war, Reuters “suppressed items of news . . . [that it] deemed would damage British interests if released.”16 Further, McCracken has documented that the British military intelligence service used journalists in its campaign to spread pro-British propaganda then. He has also given a brief account of Irish journalists who between 1827 and 1922 went to South Africa, writing that more than seventy journals employed more than 260 foreign journalists during the Boer War. Davitt, he noted, “the most famous Irish war correspondent was very different from the hacks who followed the [British commander, Frederick] Roberts’ media circus up through the Orange Free State into the Transvaal. . . . He . . . sent home strongly worded pro-Boer reports.”17

Davitt worried about being arrested later in London.18 He had, after all, actively attempted to raise military support in Europe for the Boer cause. His stories now were calculated to further the Boer struggle in accordance with the anti-British disposition of his readers. He showed little interest in how the Boers treated indigenous people, or “kaffirs” and “savages,” as he called them, but claimed that they did so better than the English did.

Davitt approved of censorship for military reasons. In his diary, he records a sleepy Sunday in Pretoria (April 8, 1900), where the Boer’s post office was only open for one hour despite the fact that a war was being waged. He gave his copy for the Freeman’s Journal to the postmaster, a “genial fellow” and “a good storyteller.” Davitt wrote, “Handed my letters to the Postmaster general today to be censored. . . . All letters going from here to British territories are read and rightly so. Otherwise men could send information and plans to the enemy of this state.”19 For its news from the Boer War more generally the Freeman’s Journal had little choice but to depend largely on the Press Association, Reuters, and English papers such as the Times and Daily Mail.

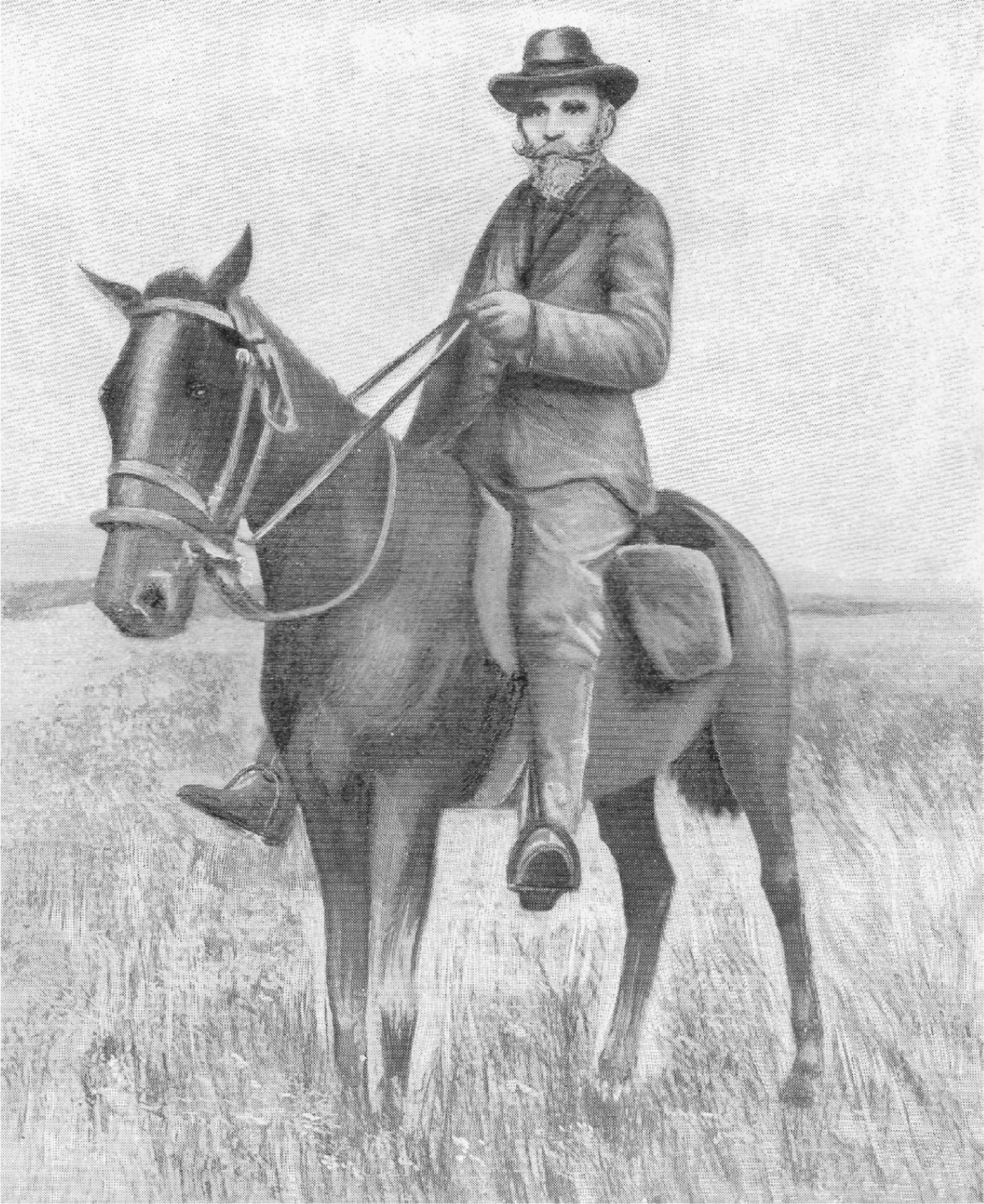

11.1. Michael Davitt in the Orange Free State, 1900. Frontispiece of his Boer Fight for Freedom (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1902).

The Freeman’s Journal was in decline by 1900.20 It did not usually engage its own correspondents abroad, so Davitt’s arrangement is striking. However, due to delays perhaps caused by British authorities, pieces that Davitt wrote in South Africa from the end of March 1900 onward did not begin to appear in the paper in Dublin until more than two months later, and Hearst’s New York newspaper did not prominently display pieces by him from Africa as it later did his dispatches from Russia. His dozen substantial pieces in the Freeman’s Journal, each about three columns long on average, usually appeared on page five or six, but were repeated on the front page of successive editions of the Weekly Freeman’s Journal during June, July, and August 1900, with some of the articles also repeated along with added images in the Irish Evening Telegraph.21

On July 9, 1900, the Freeman’s Journal boasted that, after Davitt had written about events at Magersfontein, some of the English correspondents going over the same ground as him “are forced to substantiate the details.” The editor added, “It is most amusing, if not at times nauseating, to go back six or seven months on the files of the Jingo papers and compare the news supplied then with the facts which now stand revealed.”

Davitt described the pieces he wrote for the Freeman’s Journal as a “series of sketches of Boer camps, battles, officers, men and matters.” In a standard refrain of his, he claimed that the Boer people had been “foully calumniated by the Jingo Press of Cape Town and London in order to manufacture some justification for the deliberate robbery and wilful murder of a small nation for the possession of great mineral wealth.”22

Davitt himself was accused of censorship by Arthur Griffith, a leader of advanced nationalist opinion in Ireland. Griffith was an enthusiastic admirer of Parnell, whom Davitt had quickly abandoned when the O’Shea scandal broke. After Davitt resigned his seat in Parliament, Griffith and others nominated John MacBride as an independent candidate for the South Mayo vacancy in early 1900. MacBride was then fighting on the Boer side, with an Irish Transvaal brigade of up to three hundred men that he had organized against the British. Davitt declined to back MacBride, and a more conservative nationalist won the seat. Griffith’s United Irishman later claimed that Davitt, “a man of warped mind rather than of bad heart,” failed to give MacBride the credit due for his contribution to some Boer victories.23

Davitt used the interview technique to bolster his reports, this being a popular feature of the “new journalism” that had been pioneered in Britain by his friend W. T. Stead among others. Marley writes that, “Given his reputation as a Boer sympathiser, Davitt had no difficulty in securing interviews with the Boer leaders.”24 Stead thought that Davitt’s letters for the Freeman’s Journal were “the first really serious attempts that have been made to describe the Burghers’ War of Independence from the Boers’ point of view.”25 Such reports no doubt appealed to William Randolph Hearst who is said to have had a “monumental anti-British bias,” going back to 1899 when British bankers obstructed his family’s mining ambitions in Peru. Indeed, Hearst publicly supported the liberation of Ireland.26 As his media and political ambitions grew, he also had commercial reasons to cultivate Irish American readers who lived in large numbers in New York and other cities in which he sold papers: “A patchwork of supporters gathered around him, including Irish, German, and liberalistic reformers duped by blarney about municipal ownership.” He even stands accused of fixing a race around the world that he sponsored for high school boys, so that the winner would be not only Irish but also from Chicago—where his paper’s circulation was in need of a boost.27 Hearst also poached a cartoon character, “Mickey Dugan,” from the New York newspaper of his chief competitor, Joseph Pulitzer. This young character, depicted among Irish immigrants in the New York slums, wore a distinctive cut-off, yellow nightdress and so was nicknamed “The Yellow Kid.”28

Because much information about the Boer conflict was filtered through a British lens, Hearst would clearly welcome the opportunity to have a famous Irish patriot write from the other side of the conflict. Hearst’s policy was “to engage brains as well as to get the news,”29 and he was inclined to employ public figures to write about current affairs. Hearst angered his regular foreign correspondent, Julian Ralph, when he gave greater prominence to The Red Badge of Courage author Stephen Crane’s accounts of the Greco-Turkish War and sent Mark Twain to cover Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.30

Davitt was already known to some extent in the United States, not merely because of press reports of his role in Irish and British politics, but more specifically because he made a number of visits to America and had written articles for papers there. He might be expected to have an informed idea of what appealed to American readers, and not least to Irish Americans who also imbibed pro-Boer sentiments from the New York weekly Irish World.31 Later in 1900, Hearst also commissioned Davitt to go to Marseilles and Paris to write about the reception of Boer president Paul Kruger there. Davitt understood that Hearst was pleased with his work then.32

Cables and the Correspondent

The evolution of cables as a communications medium complicated Davitt’s relationship with editors. Telegraph technology permitted journalists to get news back to their newspaper offices quickly, in marked contrast to the earlier methods of overland and overseas mailing. However, long cables were costly and cumbersome to send, and so this new technology encouraged a more staccato style of writing as well as crisp judgments. Wire services such as Reuters and Associated Press took advantage of the telegraph to offer relatively neutral news swiftly from around the world.33 While the agencies might have their own ideological or business biases,34 the speed with which their stories moved could quickly render dispatches from individual correspondents in the field out of date, even when the latter eschewed the mail and sent back long cables.35 The cable thus presented Davitt with a problem. He was conscious of its value to newspapers, noting inside the cover of his South African travel diary in 1900 that there were “170 telegraph offices in two republics [Orange Free State and Transvaal].”36 However, short factual cables did not suit Davitt’s style or purpose, for he was accustomed to mixing facts with both speculation and opinion in pieces that he wrote.

While Davitt was still in South Africa, he had written to John Dillion, “Tell T. P. not to put too much of his earnings in Rand mines. Thiggin thu [Irish for ‘you understand’].” Davitt in the 1890s had acted as an investment agent for mining ventures in Australia, South Africa, and the United States. This “T. P.” was presumably “T. P. O’Connor,” the journalist and politician who now put work Davitt’s way on the latter’s return from South Africa. O’Connor had been asked to write an occasional “Irish letter” for syndication in the United States, letters that Julius Chambers, commissioning editor of Cosmographic, wanted to be “aggressive and saucy” and “hot.” O’Connor replied that he was too busy but arranged for Davitt to do it, at a rate of five guineas for twelve hundred words twice a month. Davitt supplied about eight letters, but the Americans felt that his pieces on Irish-British developments were not “hot” enough to have avoided being “anticipated by the cable.” Cosmographic ended the arrangement early in 1901.37 About this time Davitt also wrote to a Mr. Bryan offering to serve as a correspondent in Ireland “for the paper which he is to edit.”38 This was presumably the anti-imperialist Democrat William Jennings Bryan, who had lost the US presidential election of 1900 and who thereupon founded a progressive weekly magazine in Nebraska entitled the Commoner. Davitt is known to have met Bryan. If Davitt did write for the Commoner then, his words were not deemed to merit inclusion in a volume condensing its first year.39

In January 1903 the famous editor of the Manchester Guardian, C. P. Scott, quite curtly rebuffed Davitt’s offer to be its Irish correspondent, writing that “we have already made arrangements which will suffice for the present for Irish correspondence.”40 However, that same year, Hearst’s manager in London, “the well-known journalist” E. F. Flynn, commissioned Davitt to supply copy on the national convention in Dublin convened by the United Irish League to consider the Irish (“Wyndham”) Land Bill.41 Redmond chaired that convention on April 16 and 17, 1903. Davitt, a critic of the bill, also participated from the platform. E. F. Flynn told Davitt that he should provide analysis and not news: “News agencies will report the routine happenings. . . . Deal with the spirit of the sessions, and the meanings and results of the action taken.” Flynn described Davitt’s work on this occasion as “excellent” and “very illuminating,” and held out the prospect of further commissions.42 Due to events in the Russian empire the following weekend, a new commission soon came.

Russia 1903

At the Easter holidays in 1903, from April 19 to April 21, residents of Kishineff assaulted and murdered local Jews. Kishineff (also Kishinev, today Chişinau? in Moldova) was then in Bessarabia, part of the Russian empire. The world soon learned of this violence, reminiscent of notorious atrocities committed against Jews in Russia between 1880 and 1881 that had resulted in a great exodus to North America. On April 24, 1903, the Cork Examiner and the New York Times were among newspapers that ran a brief first report from Reuters stating that twenty-five Jews had been killed and many injured. It soon became clear that the violence was worse than that.43 In the United States, where many Jews from eastern Europe now lived and where inspectors at Ellis Island were processing an unprecedented number of immigrants, meetings and sermons and resolutions about the pogrom quickly helped to mobilize public opinion.44

On May 10, 1903, Flynn cabled Davitt at home in Dalkey, County Dublin, with a request: “Can you go Russia for us to investigate recent massacres Kishineff [in] Besarabia [sic] and recrudence [of] anti-Semitism Russia. Reply prepaid. Like answer early.” He sent another cable the next day: “We would pay £20 week and all expenses, interpreter’s as of course yours. I think mission is easily finished within month. Answer quick reply.”45 The payment promised to Davitt for the month (about £90 in total) was no less than what British correspondents retained abroad by a newspaper during wartime might then expect.46 Davitt’s socialist friend Henry Mayers Hyndman thought him “none too well paid, considering the arduous and distressing character of the work to be done” for Hearst in Russia.47 On his way to Odessa from Paris, through Budapest, Davitt would bump into Hyndman. The latter recalled later, “He was in very good spirits, but assured me it was quite a mistake to imagine, as some took it for granted, that he had married an heiress, and was now well off.” Davitt told him, “It is all we can do to keep a comfortable roof over our heads, and give our children a decent education. That is why I am off on this trip.” Davitt’s wife, Mary Yore of St. Joseph, Michigan, would eventually come into a substantial inheritance of £80,000. The fact that his wife was American and his parents were buried there after emigrating reportedly made him feel closely tied to the United States.48

Having dedicated very little space to breaking news from Kishineff before May 8, Hearst’s New York American suddenly began to give it prominent coverage. On May 12 the paper splashed across its front page that it was sending an agent to Kishineff “for facts.” The next day, in another banner headline, the paper named that “agent” and “special commissioner” as Michael Davitt. “No man is better fitted than this famous liberty-loving Irishman to give to the world a true story of the butchery” proclaimed the editor, who also told readers that49

Mr. Davitt is a trained newspaper man . . . by his long journalistic training and extensive knowledge acquired by years of travel, admirably fitted for the task at hand. . . . His graphic descriptions of conditions in the Transvaal, printed in the American during the Boer War, are a sufficient guarantee of his ability to deal graphically with the Russian situation. . . . Starting as a printer’s devil in one of the London newspaper printing offices, he learned to be a compositor, and then branched out as a reporter. He worked on several of the London dailies, and gained a thorough insight into human nature.50

Davitt was to serve in Russia not only as a correspondent but also as an agent for the relief fund that Hearst promoted through his papers.51 Davitt had hoped to keep his involvement quiet until he got to Russia, the better to facilitate arrangements, he believed. Hearst’s papers were not inclined, however, to hide a light under a bushel. One of Hearst’s New York City lieutenants, the heavy-drinking Sam Chamberlain, claimed that there had been a misunderstanding and instructed Flynn to apologize to Davitt for the prompt announcement of the Hearst correspondent’s identity.

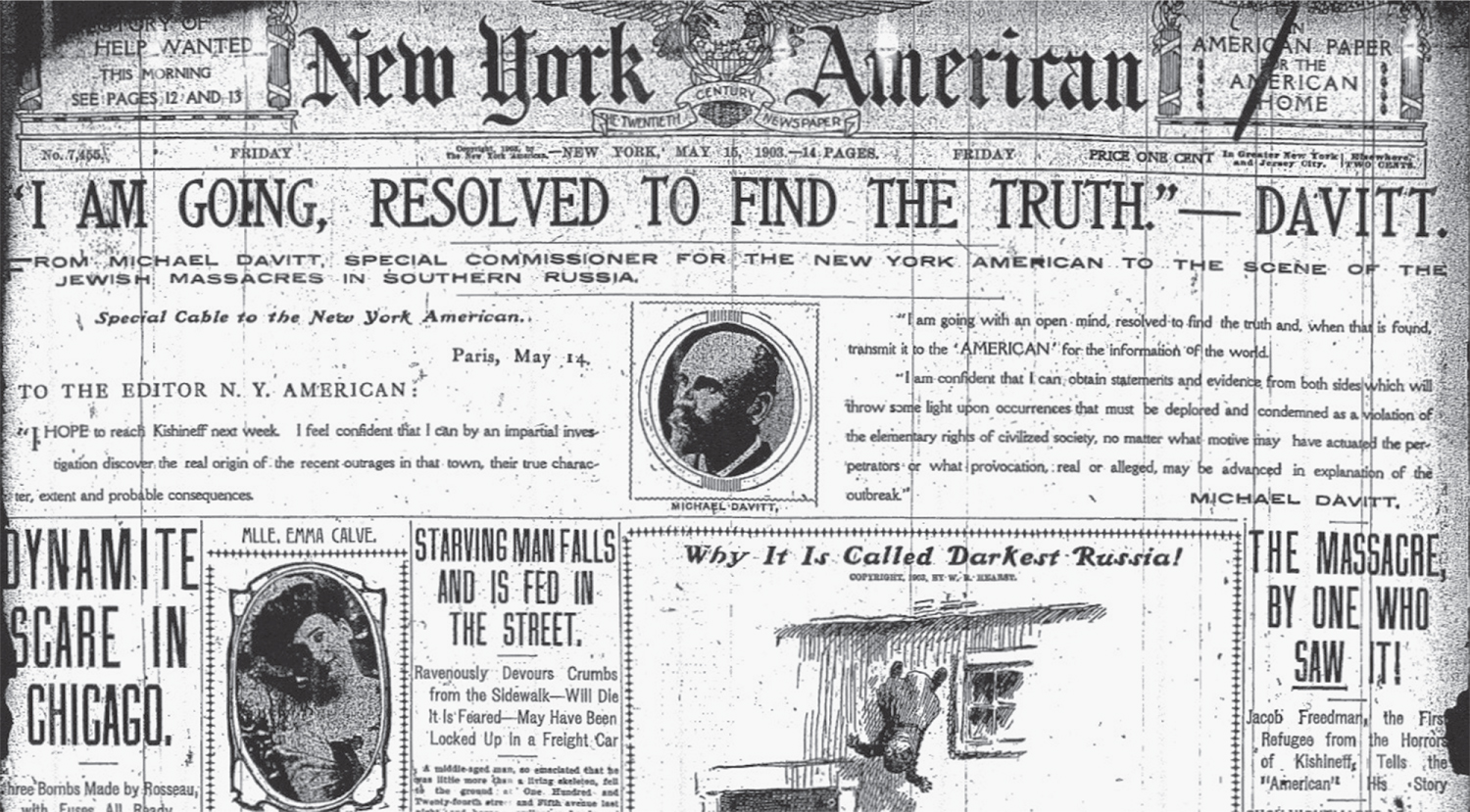

11.2. “I am going, resolved to find the truth,” proclaimed Davitt on the front page of the New York American on May 15, 1903.

Davitt made the long journey by way of Odessa only to find himself dealing with Russian censorship. Readers had to wait before any substantial article by him actually appeared in the paper. Flynn seems to have grown uneasy, cabling Davitt on May 15 that, “If Kishineff doesn’t ‘pan out’ a ripping good interview with Tolstoy on obligations of wealth, progress of socialism, religion, etc.—a peculiarly Tolstoyesque talk would be fine.” He also warned Davitt that the New York World’s correspondent had arrived ahead of him and urged him to “try to get story out quick.”52

In response, Davitt filed some discursive copy and indicated that he could not be rushed (“impossible [to] send anything Sunday”). Hearst’s man in London made his feelings clear in a cable sent on May 31:

11.3. New York American, May 22, 1903.

New York first wants facts [about] real conditions Kishineff, afterward explanations presenting Russian explanations; please telegraph Monday graphic summary [of the] facts [of the] massacre and present conditions placing responsibility massacres where they belong. Having this then we can publish explanations. Please telegraph good story Monday. Your second letter not available for cabling because filled [with] generalities. Kindly give us good story Monday. Tolstoy [and] Gorki’s letters published Berlin [and] London long ago. Notify me early Monday what you will send.53

In the meantime, some short cables from him had been given great prominence (see illustrations 11.2 and 11.3), theatrically sustaining the ostensible significance of his mission.54

On June 4, 1903, the New York American published on its front page the report by Davitt that was to win him international acclaim. It was headed “Davitt Reveals Inside Facts of Kishineff Massacre.” Just this one long and graphic piece, which due to censorship was cabled not from Kishineff but from Berlin after he left Russia, and two more sent later from London, appear to have been the sum of substantial investigative articles Davitt returned on Hearst’s investment.55 However, these longer pieces, together with Davitt’s earlier short cables, solidly underpinned what by then had been prominently alleged and reported from other sources in Hearst’s papers. By the time that Davitt managed to make his way overland to Kishineff and subsequently file copy, Hearst’s papers had published pieces from the Associated Press as well as cabled eyewitness reports and photographs and some commentary from Russia.

To describe Hearst’s commissioning of Davitt as a showy publicity stunt would not be entirely fair, nor is it true to say that Hearst simply accepted Davitt’s judgment. Where the New York American made clear editorially that it blamed Russia for the pogrom, a position that was consistent with its hostility to Russia’s government,56 Davitt blamed events in Kishineff on local Russian officials in Bessarabia and only mildly scolded senior authorities in St. Petersburg for not intervening promptly or well. Indeed, that the pogrom was not concocted by the tsar’s highest officials is also the judgment of history.57 That also seems to have been the view of US ambassador to Russia Robert S. McCormick, whom Davitt met a number of times in St. Petersburg in 1903. McCormick even went further, being chided by the New York American for reportedly declaring that the condition of Russian Jews had been “never better.”58 Davitt may not have entirely agreed with McCormick, but his friend Hyndman noted the former’s hostility toward Jews engaged in economic activities of which the Irishman disapproved, a hostility that I have discussed elsewhere.59 Hyndman remarked that, “Undoubtedly, Davitt in private, while not excusing the Russian authorities, felt that Russia would be much better off if she had no Jews at all within her boundaries. . . . Perhaps the Irish feeling against the gombeen-man [a local trader who loaned money] made Davitt less bitter than he would otherwise have been against the slaughterers of Jews.”60

11.4. New York American, June 4, 1903.

Davitt’s presence in Russia helped to galvanize public opinion in America. He cabled that in his travels across “almost [the] whole territory [of the] Jewish Pale settlement from Odessa [to] Warsaw,” he found “violently anti-Semitic” attitudes among community leaders. He wrote that the Moldovan editor of a Kishineff paper had “systematically inflamed popular feeling against Jews,” and that the local police chief had told him that it “would serve Jews right if driven from [the] city.” Both the editor and police chief claimed that Jews preached socialism. Davitt thought that Moldovans were a “most ignorant, brutal populace.”61 Davitt was quoted at meetings in America protesting the pogrom.62

Davitt recommended “sending an eminent American to see the czar to state the case and secure an amelioration of the Jews’ condition.” This idea “made a hit in New York,” Flynn told him, but Davitt’s suggestion that the former US president Grover Cleveland be that American did not. Flynn told him, “We didn’t fancy Cleveland as an emissary.” Instead, a trip by Hearst was contemplated.63 There was precedent for such an intervention. Hearst had, after all, sailed his yacht down to Cuba in 1898 during the Spanish-American War and had even taken some shipwrecked Spanish sailors prisoner. However, Hearst did not go to Russia then.

On June 5, Hearst’s American publicly commended to President Theodore Roosevelt and to the US secretary of state Davitt’s reports from Russia. The Irishman was, wrote its editor, “an impartial witness, whose standing is such as to compel respect and credence. He shows that official Russia was deeply concerned in this outbreak of anti-Semitism which has so shocked and stirred civilized mankind.”64 However, it is a stretch to read Davitt’s report as “deeply” involving Russian officials outside Kishineff in the pogrom. He had, in fact, cabled that there was “no evidence produced for me [that] implicated [the] government [in] St. Petersburg [in] any way [as having had] responsibility [for the] outbreak which has covered [the] name Russia [in] shame.” He merely conceded that its interior minister “must have known that [an] outbreak was contemplated,” albeit not imagining that the affair would “culminate in massacres.”65

As Russian authorities struggled to respond to criticism, Davitt had difficulty filing his stories. For example, his story about a Russian claim that a Jewish proprietor of a carousel machine had sparked riots by striking a Christian woman had to be “cabled from Berlin because he found it impossible on account of the Russian censorship to send the truth from Kishineff.” In his piece he rejected the Russian version of the carousel incident. He had investigated it thoroughly, and wrote, “There is no truth in the story. I found the owner of the merry-go-round. He is a German named Reinhold Mergert, and is a Christian. He assured me that no woman was insulted or hurt on that occasion.”66

Hayyim Nahman Bialik, who wrote an influential poem about the pogrom (“In the City of Slaughter”) and who is regarded today as Israel’s national poet, was in Kishineff at the same time as Davitt and used the same translator. Both men, no doubt with the best of intentions, appear to have repressed details of Jewish reaction to the pogrom that did not suit their purposes. Zipperstein observes that Davitt “chose for reasons never explained to sequester his criticisms” of Jewish passivity in the face of mob violence and argues that this “raises intriguing questions, not only with regard to Davitt’s motivations, but also about how it is that complex, unsettling stories tend to be narrated, reproduced, and also, at times, obliterated.”67

Among Davitt’s photographs from Kishineff, the New York American published one of the Irishman standing in the Jewish cemetery next to two inscribed headstones and forty-four mounds that the editor described as “the newly made graves of the massacre.”68 Some of his writings on that pogrom are said to have made Davitt “a folk hero among Jews.”69

By the end of 1903, Davitt had finished a book on the Kishineff pogrom in which he explained that Hearst had not published all of his dispatches from Russia, “for reasons which govern the exigencies of journals that are concerned much more with a record of daily events in the United States than with history.”70 This was, perhaps, Davitt’s way of acknowledging that while Hearst was happy with his reporting “facts,” the publisher was less interested in Davitt’s interpretations where these did not align with Hearst’s editorial position on Russia.

In the same book Davitt explained the newsgathering methodology that he had used in Russia—and his process reflects well on him. However, he also excused the Russian government, to some extent, for what happened; and remarkably, given that an American Jewish society published the book, he took the opportunity to justify selective anti-Semitism.71

Hearst’s satisfaction with Davitt’s Russian service is reflected in the publisher’s efforts to get him to go to Bulgaria and Macedonia in September of that same year. “Thank you, could name your own terms,” wrote E. F. Flynn to him. He told Davitt that Hearst believed he would “be the best man for the job” and asked, “Can’t [your] break wait?”72 By December 1903 Flynn was also urging Davitt to return to Kishineff.73

11.5. New York American, June 14, 1903.

Russia 1904–1905

On February 9, 1904, Japan and Russia went to war, each jostling for control in Manchuria. Davitt tried to persuade Hearst to send him to the front, but Hearst rejected this idea, perhaps because of the possible dangers involved.74 However, Davitt did return to Russia in May and June 1904, interviewing Leo Tolstoy at his country home for the Freeman’s Journal.75 Davitt also then met Howard Thompson of the Associated Press, and the two discussed what the Irishman termed “manufactured news.” Davitt dismissed the London Standard’s report of mass executions by Russian forces in Warsaw as “absolutely without foundation.”76 In his Sherbourne Reporter’s Note Book, Davitt recorded what he considered to be the “aristignorance” and bias of English correspondents in St. Petersburg. He thought that the Reuters man there was “a pretentious prig.”77 Davitt also met again the highly respected US ambassador Robert S. McCormick who, as Davitt wrote, “regrets [the] attitude [of the] American press over [the] war.”78

Davitt went to Russia with letters of introduction from prominent men such as William Stead and Charles R. Crane, a wealthy businessman and friend of Hearst.79 Crane, who fostered Russian studies in America but who was no admirer of Jews, personally penned notes in which he commended Davitt as “going to Russia to make a study of,” variously, “the working people” or “the industrial classes” or “the working classes.”80

The Russo-Japanese War was not to end until September 1905. In the meantime, social unrest grew in western Russia. On January 22, 1905, Russian soldiers opened fire on workers outside the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, an event that came to be known as Bloody Sunday or Red Sunday. On January 23 Flynn cabled Davitt that Hearst desired him to start at once for Moscow, which he did. Passing through London, Davitt learnt from Flynn that Hearst wanted him to “interview Tolstoy. Then ‘exploit’ any and all sources for copy.” He was off again (Davitt himself proudly noted) on a “special mission for Hearst’s papers . . . in New York, Boston, Chicago, Indianapolis, San Francisco and Los Angeles, California.”81

Arriving in St. Petersburg, Davitt quickly “gathered up [a] pretty accurate account of how things stand” and cabled his 153-word account to New York.82 His notes suggest a conclusion earlier reached. Referring to “official sources,” he reported claims that the Japanese and their financial allies in London and Paris had funded revolutionaries “to create disturbances and to embarrass Russia.” Davitt declared this was likely true and “corresponds with my own belief.”83 He played down the events of January 22 at the Winter Palace, reporting that workers “wanted better conditions . . . not revolution” and blaming their leader, Father Georgy Gapon, for leading an unarmed mob into “almost certain” conflict with soldiers.84 He noted that Ambassador McCormick considered London papers to be exaggerating the situation “beyond belief” and had hinted to Davitt that Gapon was a scoundrel who had “ruined girls, and possibly an agent provocateur.”85 Davitt appears to have justified soldiers indiscriminately shooting into crowds when necessary to restore order.86

Davitt underestimated the extent of growing discontent, writing scornfully that revolution was more likely in Germany or Colorado than in Russia.87 He likewise cabled that the movement to dethrone the tsar was as unpopular with the Russian people as removing the pope would be with Catholics. He added, “Actual revolution out of question.”88 The London correspondent for the Freeman’s Journal predicted quite differently that, “It seems to be deemed as certain as if sentence of death were passed on him by a regularly constituted tribunal that the Tsar’s fate personally is sealed.”89

Six days after Red Sunday, on behalf of “several leading American newspapers,” Davitt requested an interview with Tsar Nicholas II, “in the confident belief that a brief statement from your majesty on the present situation in Russia would have a most beneficial effect upon public opinion in the United States.” He described himself as being “in a humble way, a supporter of Russia in the press of the United States, England and Ireland since Japan declared war” and noted his belief that, “the real origin of the recent troubles in St. Petersburg can be traced to foreign influences operating through the press of London and Paris, against the financial credit of Your Majesty’s government in the hope of injuring the prospects of the next Russian loan. In this way the financial friends of Japan are trying to force Your Majesty’s hand in the direction of peace with England’s ally in the Far East.”90 Davitt declared, “May I live until I am accorded this interview anyhow!”91 He was not accorded it. Russian regulations required foreigners to go through their embassies to obtain an audience with the tsar. For Davitt, that would have required his availing of the services of the United Kingdom’s ambassador, and he allowed politics to prevail over journalism. He exclaimed that he “would see fifty New York Journals in [flames?] before [I] would seek a favour from a British ambassador here or elsewhere.”92 In a further display of principle, he risked letting Pulitzer’s New York World scoop Hearst’s Journal when he again interviewed Tolstoy in the country,93 for he took with him Stephen McKenna (Paris bureau chief of Pulitzer’s paper and a friend of the Irish playwright John Millington Synge) because it was clear that McKenna could not otherwise get there and back in time to meet his deadline. Davitt wondered how the Journal editors would react if they knew he had aided a competitor. Fortunately, McKenna delayed sending copy and so did not scoop Davitt.94

From St. Petersburg, Davitt went to what were then the Russian provinces of Finland and Poland. In Warsaw on February 12, 1905, he noted “not alone a gross but a deliberate exaggeration” of strike troubles and casualties in those provinces by English, French, and German correspondents. He claimed that the European press, particularly those papers “owned and controlled by stock-exchange influences, and especially by Jews,” were responsible for “the wildest exaggerations of Russia’s internal troubles. . . . This is not fair journalism.”95 He wrote to Ernest Judet, director of L’Éclair, condemning “the atrocious campaign of falsehood against Russia . . . by the London press assisted by a few Paris journals.” He added that never “as a public man and as a journalist have I had experience of such a carnival of falsehoods as that in which the London Times and all the other English papers have wallowed during the last three weeks over Russian internal troubles.”96

Davitt’s efforts to provide “balance” within the international media’s coverage of Russia were not going unnoticed. On February 7, 1905, in Oakland, California, (where Davitt had met his future wife in 1880), the editor of a local newspaper penned a fierce editorial about him, headed “How the Mighty Are Fallen.” The editor accused Davitt of smoothing matters over “for the court circle in St. Petersburg,” and he noted that the Irishman’s letters from Russia were not nearly as indignant as his “denunciation of British oppression in Ireland, India and elsewhere. His reports put a pleasant complexion on the policy and conduct of the despotic government of the tsar.”97

Conclusion

Michael Davitt was an experienced and prolific journalist, writing for English-language papers in Ireland, Britain, the United States, and elsewhere. He mixed facts with opinions as was common for correspondents in his day. He intended his reports from South Africa and Russia to balance what he regarded as inaccurate, hostile, and jingoistic accounts in British and other newspapers that published what he called then not “fake news” but “manufactured news.” His reports were sometimes both graphic and gripping as he sought to engage readers by providing alternative facts as a form of balance rather than always attempting to present both sides of a story.

Davitt did not neatly tailor his reports from Russia to conform to the editorial line taken by Hearst that was very critical of the Russian government, but moderated criticism at a time when Irish nationalists sympathized with Russia as England’s foe in international affairs. His reports from Kishineff helped to shape international opinion and won him respect among Jews abroad, notwithstanding Davitt’s hostility toward some rich and pro-British Jews internationally and his reservations about the behavior of some Jews in Kishineff.

Because of the political bias of what he wrote, as well as the fact that he understated the plight both of indigenous peoples in South Africa and of the workers in Russia who fought its government for radical reforms, one cannot with confidence claim that Davitt was never guilty of self-censorship.