CHAPTER 9

Quotations and direct speech

9.1 General principles

A direct quotation presents the exact words spoken on a particular occasion or written in a particular place. It can be of any length, but there are legal restrictions on how much of another’s work one may repeat; for more on copyright see Chapter 20.

A direct quotation or passage of direct speech should be clearly indicated and, unlike a paraphrase, should exactly reproduce the words of the original. Although the wording of the quoted text should be faithfully reproduced, the extent to which the precise form of the original source is replicated will vary with context and editorial preference.

Quotations from early manuscripts may call for more or less complex and specialist conventions that are not discussed here.

9.2 Layout of quoted text

9.2.1 Displayed and run-on quotations

Quotations can be run on in text or broken off from it. A prose quotation of fewer than, say, fifty words is normally run on (or embedded) and enclosed in quotation marks, while longer quotations are broken off without quotation marks. But there is no firm rule, and the treatment of particular quotations or groups of quotations will depend on editorial preference, context, and the overall look of the displayed text. A passage that contains multiple quotations, for example, may be easier to read if all are displayed, even if some or all of them contain fewer than fifty words. Or it may be thought helpful to display a single, short quotation that is central to the following argument.

Quotations that are broken off from text (called displayed or block quotations, or extracts) begin on a new line, and can appear in various formats: they may be set in smaller type (usually one size down from text size), or in text-size type with less leading (vertical space between the lines); set to the full measure, or to a narrower measure; set with all lines indented from the left, or block centred (indented left and right); or set justified or unjustified. A commonly encountered style is shown below; the text is indented one em left and right:

Most of those who came in now had joined the Army unwillingly, and there was no reason why they should find military service tolerable. The War had become undisguisedly mechanical and inhuman. What in earlier days had been drafts of volunteers were now droves of victims. I was just beginning to be aware of this.

Displayed quotations should not be set entirely in italic type even if they appeared thus in the original publication (although individual words may of course be italicized). If two or more quotations that are not continuous in the original are displayed to follow one another with none of the author’s own text intervening, the discontinuity is shown by extra leading.

More than one line of quoted verse is normally displayed, line by line. Some other material, for example lists, whether or not numbered, and quoted dialogue, is suitable for line-by-line display. For verse quotations see 9.4 below; for extracts from plays see 9.5.

Because displayed quotations are not enclosed by quotation marks, any quoted material within them is enclosed (in British style) by single quotation marks, not double. A quotation within a run-on quotation is placed within double quotation marks:

These visits in after life were frequently repeated, and whenever he found himself relapsing into a depressed state of health and spirits, ‘Well’, he would say, ‘I must come into hospital’, and would repair for another week to ‘Campbell’s ward’, a room so named by the poet in the doctor’s house.

Chancellor was ‘convinced that the entire Balfour Declaration policy had been “a colossal blunder”, unjust to the Arabs and impossible of fulfillment in its own terms’.

If a section consisting of two or more paragraphs from the same source is quoted, quotation marks are used at the beginning of each paragraph and the end of the last one, but not at the end of the first and intermediate paragraphs.

9.2.2 Introducing quotations and direct speech

When quoted speech is introduced, interrupted, or followed by an interpolation such as he said, the interpolation is usually separated from the speech by commas:

‘I wasn’t born yesterday,’ she said.

‘No,’ said Mr Stephens, ‘certainly not.’

A voice behind me says, ‘Someone stolen your teddy bear, Sebastian?’

A colon may also be used before the quoted speech. A colon is typically used to introduce more formal speech or speeches of more than one sentence, to give emphasis to the quoted matter, or to clarify the sentence structure after a clause in parentheses:

Rather than mince words she told them: ‘You have forced this move upon me.’

Philips said: ‘I’m embarrassed. Who wouldn’t be embarrassed?’

Peter Smith, general secretary of the Association of Teachers and Lecturers, said: ‘Countries which outperform the UK in education do not achieve success by working teachers to death.’

Very short speeches do not need any introductory punctuation: and neither does a quotation that is fitted into the syntax of the surrounding sentence:

He called ‘Good morning!’

He is alleged to have replied that ‘our old college no longer exists’.

The words yes and no and question words such as where and why are enclosed in quotation marks where they represent direct speech, but not when they represent reported speech or tacit paraphrasing:

She asked, ‘Really? Where?’

He said ‘Yes!’, but she retorted ‘No!’

The governors said no to our proposal.

When I asked to marry her, she said yes.

9.2.3 Quotation marks

Modern British practice is normally to enclose quoted matter between single quotation marks, and to use double quotation marks for a quotation within a quotation:

‘Have you any idea’, he said, ‘what “red mercury” is?’

The order is often reversed in newspapers, and uniformly in US practice:

“Have you any idea,” he said, “what ‘red mercury’ is?”

If another quotation is nested within the second quotation, revert to the original mark, either single-double-single or double-single-double.

Quotation marks with other punctuation

When quoted speech is broken off and then resumed after words such as he said, a comma is used within the quotation marks to represent any punctuation that would naturally have been found in the original passage. Three quoted extracts—with and without internal punctuation—might be:

Go home to your father.

Go home, and never come back.

Yes, we will. It’s a good idea.

When presented as direct speech these would be punctuated as follows:

‘Go home’, he said, ‘to your father.’

‘Go home,’ he said, ‘and never come back.’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘we will. It’s a good idea.’

The last example above may equally be quoted in the following ways:

He said, ‘Yes, we will. It’s a good idea.’

‘Yes, we will,’ he said. ‘It’s a good idea.’

‘Yes, we will. It’s a good idea,’ he said.

In US practice, commas and full points are set inside the closing quotation mark regardless of whether they are part of the quoted material (note in the US example the double quotation marks):

No one should ‘follow a multitude to do evil’, as the Scripture says.

US style: No one should “follow a multitude to do evil,” as the Scripture says.

This style is also followed in much modern British fiction and journalism. In the following extract from a British novel the comma after ‘suggest’ is enclosed within the quotation marks even though the original spoken sentence would have had no punctuation:

‘May I suggest,’ she said, ‘that you have a bath before supper?’

Traditional British style would have given:

‘May I suggest’, she said, ‘that you have a bath before supper?’

When a grammatically complete sentence is quoted, the full point is placed within the closing quotation mark. The original might read:

It cannot be done. We must give up the task.

It might then be quoted as

He concluded, ‘We must give up the task.’

‘It cannot be done,’ he concluded. ‘We must give up the task.’

When the quoted sentence ends with a question mark or exclamation mark, this should be placed within the closing quotation mark, with no other mark outside the quotation mark—only one mark of terminal punctuation is needed:

He sniffed the air and exclaimed, ‘I smell a horse!’

When the punctuation mark is not part of the quoted material, as in the case of single words and phrases, place it outside the closing quotation mark:

Why does he use the word ‘poison’?

When a quoted sentence is a short one with no introductory punctuation, the full point is generally placed outside the closing quotation mark:

Cogito, ergo sum means ‘I think, therefore I am’.

He believed in the proverb ‘Dead men tell no tales’.

He asserted that ‘Americans don’t understand history’, and that ‘intervention would be a disaster’.

9.2.4 Dialogue

Dialogue is usually set within quotation marks, with each new speaker’s words on a new line, indented at the beginning:

‘What’s going on?’ he asked.

‘I’m prematurely ageing,’ I muttered.

In some styles of writing—particularly fiction—opening quotation marks are replaced with em rules and closing quotation marks are omitted:

— We’d better get goin’, I suppose, said Bimbo.

— Fair enough, said Jimmy Sr.

In other styles, marks of quotation are dispensed with altogether, the change in syntax being presumed sufficient to indicate the shift between direct speech and interpolations:

Who’s that? asked Russell, affecting not to have heard.

Why, Henry, chirped Lytton.

Dialogue in fiction is often not introduced with ‘say’ or any other speech verb:

I decide it’s Spencer’s fault, and sit up grumpily.

‘Who let you in?’

Thought and imagined dialogue may be placed in quotation marks or not, so long as similar instances are treated consistently within a single work.

9.2.5 Sources

The source of a quotation, whether run on or displayed, is normally given in a note if the work uses that form of referencing, or it may be presented in an author-date reference. The source of a displayed prose quotation may be given in the text. It may, for example, follow the end of the quotation in parentheses after an em space, or be ranged right on the measure of the quotation, either on the line on which the quotation ends, if there is room, or on the following line:

Troops who have fought a few battles and won, and followed up their victories, improve on what they were before to an extent that can hardly be counted by percentage. The difference in result is often decisive victory instead of inglorious defeat (Personal Memoirs, 355).

He brought an almost scholarly detachment to public policy—a respect for the primacy of evidence over prejudice; and in retirement, this made him a valued and respected member of the scholarly community. Those of us privileged to know him will always remember him as an exemplar of standards and qualities in public life.

The Times, 8 Nov. 1999

9.3 Styling of quoted text

9.3.1 Spelling, capitalization, and punctuation

In quotations from printed sources the spelling, capitalization, and punctuation should normally follow the original. However:

Preserve if possible the Old and Middle English letters ash (æ), eth (ð), thorn (Þ), yogh (ȝ), and wyn (ƿ) in quotations from printed sources (see 12.13.1). Ligatured œ and æ in quoted text may be retained or printed as two separate letters according to editorial policy.

9.3.2 Interpolation and correction

Place in square brackets any words interpolated into a verbatim quotation that are not part of the original. Use such interpolations sparingly. Editorial interpolations may be helpful in preserving the grammatical structure of a quotation while suppressing irrelevant phrasing, or in explaining the significance of something mentioned that is not evident from the quotation itself. The Latin words recte (meaning ‘properly’ or ‘correctly’) and rectius (‘more properly’) are rare but acceptable in such places:

he must have left [Oxford] and his studies

as though they [the nobility and gentry] didn’t waste enough of your soil already on their coverts and game-preserves

the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester [recte Cumberland] are often going to a famous painters in Pall Mall; and ’tis reported that he [Gainsborough] is now doing both their pictures

The Latin word sic (meaning ‘thus’) is used to confirm an incorrect or otherwise unexpected form in a quotation; it is printed in italics within square brackets. Do not use sic simply to flag erratic spelling, but only to remove real doubt as to the accuracy of the quoted text. Do not use [!] as a form of editorial comment:

Bulmer established his Shakspeare [sic] Press in London at Cleveland Row

In some contexts editorial policy may allow the silent correction of trivial errors in the original, judging it more important to transmit the content of the quoted matter than to reproduce its exact form.

9.3.3 Omissions

Mark the omission of text within a quotation by an ellipsis (...). Do not place an ellipsis at the start or end of a quotation, even if this is not the beginning or end of a sentence; the reader must accept that the source may continue before and after the text quoted. See 4.7 for a full discussion of ellipses.

Punctuation immediately before or after an ellipsis can generally be suppressed unless it is helpful to the sense, as might be the case with a question or exclamation mark; style in similar contexts should be consistent within a work. It may, however, be retained in some contexts—for purposes of textual analysis, for example, or where the author has some other particular reason for preserving it. If the preceding sentence ends with a full point it is Oxford practice to retain the point before the ellipsis, closed up to the preceding text:

Writing was a way of understanding … world events.

Where is Godfrey? … They say he is murdered by the papists.

Presently a misty moon came up, and a nightingale began to sing.… It was strange to stand there and listen, for the song seemed to come all the more sweetly and clearly in the quiet intervals between the bursts of firing.

Do not delete an ellipsis that is part of the original text if the words on either side of it are retained in the quotation. In a quotation that contains such an original ellipsis any editorial ellipsis should be distinguished by being placed within square brackets:

The fact is, Lady Bracknell […] my parents seem to have lost me … I don’t actually know who I am […] I was … well, I was found.

An ellipsis can mark an omission of any length. In a displayed quotation broken into paragraphs mark the omission of intervening paragraphs by inserting an ellipsis at the end of the paragraph before the omission. For omissions in verse extracts see 9.4.3 below.

9.3.4 Typography

A quotation is not a facsimile, and in most contexts it is not necessary to reproduce the exact typography of the original. Such features as change of font, bold type, underscoring, ornaments, and the exact layout of the text may generally be ignored. Italicization may be reproduced if helpful, or suppressed if excessive.

9.4 Poetry

9.4.1 Run-on verse quotations

More than one line of quoted verse is normally displayed line by line, but verse quotations may also be run on in the text. In run-on quotations it is Oxford style to indicate the division between each line by a vertical bar (|) with a space either side, although a solidus (/) is also widely used:

‘Gone, the merry morris din, | Gone the song of Gamelyn’, wrote Keats in ‘Robin Hood’

When set, the vertical or solidus must not start a new line. See also 4.13.

9.4.2 Displayed verse

In general, poetry (including blank verse) should be centred on the longest line on each page; if this is disproportionately long the text should be centred optically. Within the verse the lines will generally range on the left, but where a poem’s indentation clearly varies the copy should be followed: this is particularly true for some modern poetry, where correct spacing in reproduction forms part of the copyright. In such instances it is useful to provide the typesetter with a PDF or photocopy of the original to work from. It is helpful to indent turnovers 1 em beyond the poem’s maximum indentation:

Pond-chestnuts poke through floating chickweed on the green

brocade pool:

A thousand summer orioles sing as they play among the roses.

I watch the fine rain, alone all day,

While side by side the ducks and drakes bathe in their crimson

coats.

Do not automatically impose capitals at the beginnings of lines. Modern verse, for example, sometimes has none, and the conventions commonly applied to Greek and Latin verse allow an initial capital to only a few lines (see 12.8.5, 12.12.3).

9.4.3 Omissions

Omissions in verse quotations run into text are indicated like those in prose. Within displayed poetry the omission of one or more whole lines may be marked by a line of points, separated by 2-em spaces; the first and last points should fall approximately 2 ems inside the measure of the longest line:

Laboreres Þat haue no lande, to lyue on but her handes,

Deyned nouȝt to dyne a-day, nyȝt-olde wortes.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Ac whiles hunger was her maister, Þere wolde none of hem chyde,

Ne stryve aȝeines his statut, so sterneliche he loked.

Use an ellipsis when the end of a line of displayed verse is omitted; indicate the omission of the start of the first line of displayed verse by ranging (usually right with the next line):

a great beau,

that here makes a show,

and thinks all about him are fools

9.4.4 Sources

If there is sufficient room a short source—such as a book, canto, or line number, or a short title—can be placed in parentheses on the same line as the last line of verse. Oxford practice is to begin the reference 1 em to the right of the end of the quotation’s longest line:

The world was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and providence their guide:

They hand in hand with wandering steps and slow

Through Eden took their solitary way

(xii. 648–9)

If the source is longer place it on the next line down, ranged to the right with the end of the quotation’s longest line:

They hand in hand with wandering steps and slow

Through Eden took their solitary way

Paradise Lost, xii. 648–9

9.5 Plays

Publishers have their own conventions for the presentation of plays, quotations from which may be treated as run-on quotations, or as prose or poetry extracts, with no strict regard to the original layout, spacing, or styling of characters’ names. Any sensible pattern is acceptable if consistently applied. If a speaker’s name is included in the quotation it is best printed as a displayed extract.

To follow Oxford’s preferred format in extracts from plays, set speakers’ names in small capitals, ranged full left. In verse plays run the speaker’s name into the first line of dialogue; the verse follows the speaker’s name after an em space and is not centred; indent subsequent lines by the same speaker 1 em from the left. Indent turnovers 2 ems in verse plays, 1 em in prose plays:

Her reply prompts Oedipus to bemoan his sons’ passivity:

OEDIPUS But those young men your brothers, where are they?

ISMENE Just where they are—in the thick of trouble.

OEDIPUS O what miserable and perfect copies have they grown to be of Egyptian ways!

For there the men sit at home and weave while their wives go out to win the daily bread.

This is apparent in the following exchange between them:

WIPER We’ve had ballistics research on this. No conceivable injury could from this angle cause even the most temporary failure of the faculties.

BUTTERTHWAITE You can’t catch me. I’ve read me Sexton Blake. I was turned the other way.

WIPER Are you in the habit, Alderman, of entering your garden backwards?

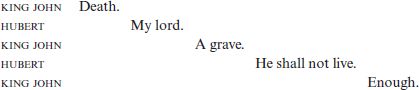

Particularly in verse plays a single line is sometimes made up of the speeches of more than one character and is set as more than one line of type. The parts are progressively indented, with an interword space clear to the right of the previous part’s end, repeating as necessary. Ideally this layout should be preserved in the quoted extract, as in the following extreme example:

Do not include stage directions in extracts from plays unless they are relevant to the matter under discussion (in which case their styling in the original may be preserved or adapted). Similarly, line numbers should not normally be included.

9.6 Epigraphs

In publishing, an epigraph is a short quotation or saying at the beginning of a book or chapter. Publishers will have their own preferences for the layout of epigraphs. In Oxford’s academic books they are set in small type, verse epigraphs being treated much like displayed verse quotations and optically centred. A source may be placed on the line after the epigraph, ranged right on the epigraph’s measure:

To understand history the reader must always remember how small is the proportion of what is recorded to what actually took place.

Churchill, Marlborough

An epigraph’s source does not usually include full bibliographic details, or even a location within the work cited (though such information can be given in a note if it seems helpful). The date or circumstances of the epigraph, or the author’s dates, may be given if they are thought to be germane:

You will find it a very good practice always to verify your references, sir!

Martin Joseph Routh (1755–1854)

9.7 Non-English quotations

Quotations from languages other than English are commonly given in English translation, but they are sometimes reproduced in their original language, for example when their sense is thought to be evident, in specialist contexts where a knowledge of the language in question is assumed, or where a short quotation is better known in the original language than it is in English:

L’État c’est moi (‘I am the State’)

Après nous le déluge (‘After us the deluge’)

Arbeit macht frei (‘Work liberates’)

Quotations in other languages follow the same rules as those in English. The wording, spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and layout of non-English quotations should be treated like those in English, and omissions, interpolations, and sources presented in the same way:

Asked about the role of the new Spanish government in his release, Raúl Rivero replied:

Tengo un sentimiento de gratitud con el Gobierno de [José María] Aznar por lo que hizo cuando caí preso. Pero, efectivamente, me parece que la nueva politica española ha sido más efectiva. La confrontación nunca en política resuelve nada. Creo que el cambio sí ha favorecido … que en Cuba hubiera más receptividad en las autoridades cubanas.

El País, 1 Dec. 2004, 33e

Le Monde reported that ‘Raúl Rivero a exprimé sa “gratitude éternelle” envers le gouvernement espagnol’.

In the second example the original wording, including the French rendering of a Spanish name, has been reproduced exactly, but French quotation marks and italicization of quotations (« gratitude éternelle ») have been adapted to British conventions.

Sometimes it seems desirable both to retain the original—perhaps because its exact sense or flavour cannot be captured by a translation— and to provide an English version for readers unfamiliar with the language in question. It is always worth asking in such cases whether the original is genuinely helpful to the reader. The English equivalent may take the form of an explanation or paraphrase, but if it too is presented as a direct quotation, whether loose or literal, it should be enclosed in quotation marks and will normally be placed within parentheses after the original. Alternatively the translation may be given first, followed by the original in quotation marks within parentheses. If sources of quotations are given in parentheses, a source may follow a translation within a single set of parentheses, separated from it by a comma, semicolon, or colon, according to house style:

It provided accommodation for ‘candidates às magistraturas superiores das Faculdades’, those eligible for senior posts in the university.

The cyclist Jean Bégué was ‘de ces Jean qu’on n’ose pas appeler Jeannot’ (‘one of those men named John one dare not call Johnny’).

He poses the question ‘Wie ist das Verhältnis des Ausschnitts zur Gesamtheit?’ (‘What is the relationship of the sample to the whole group?’: Bulst, ‘Gegenstand und Methode’, 9).

Inter needed to develop ‘a winning attitude and an attractive style of play’ (‘un’identità vincente e un bel gioco’).

Where a displayed translation is followed by a displayed original—or vice versa—place the second of the two quotations in parentheses. Where the second of the two displayed quotations is the original, some authors prefer to have it set in italics. A displayed verse original may be followed either by a verse translation set in lines or by a displayed prose translation:

Rufus naturaliter et veste dealbatus

Omnibus impatiens et nimis elatus

(Ruddy in looks and white in his vesture,

Impatient with all and too proud in gesture) (Wright, i. 261)

Gochel gwnsel a gwensaeth

a gwin Sais, gwenwyn sy waeth

(Beware the counsel, fawning smile and wine of the Englishman—it is worse than poison)

In most contexts quotations from other languages should be given in translation unless there is a particular reason for retaining the original. On occasion it is helpful to include within a translation, in italics within parentheses, the untranslated form of problematic or specially significant words or phrases:

Huntington, ‘obsessed with the idea of purity, does not recognize the cardinal virtue of … Spanish: the virtue of coexistence and intermixing (mestizaje)’.

Isolated non-English words or phrases generally look best italicized rather than placed in quotation marks (see 7.2.2), especially if they are discussed as set terms rather than quotations from a particular source. For inflected languages this has the advantage of allowing the nominative form of a word to be given even when another case is used in the passage cited. The non-English term may be used untranslated or with an English equivalent (perhaps on its first occurrence only if it is used frequently):

This right of common access (Allemansrätten) is in an old tradition

As early as 1979 the status of denominação de origem controlada was accorded to Bairrada

In this document he is styled magister scolarum

Montella was capocannoniere (top scorer), with eleven goals

In some works appropriate conventions will be needed for quotations transliterated from non-roman alphabets and for the rendering of German Fraktur type. The German Eszett (ß) can normally be regularized as double s (ss). For advice on transliteration see Chapter 12.