CHAPTER 4

Punctuation

4.1 Introduction

This chapter deals with particular situations where punctuation can be problematic or may be treated in different ways. It does not attempt to give a full account of the ways that punctuation is used in English. Some sections—such as those on the comma splice and on the use of apostrophes to form plurals—give guidance on correct usage, and explain styles that must be followed in order to write good English. Other sections, for example that on the serial comma, describe situations where a number of styles are possible but where a particular one should be adopted in order to produce a consistent text or adhere to a particular house style. See 21.2 for more details of US English usage.

4.2 Apostrophe

4.2.1 Possession

Use ’s to indicate possession after singular nouns and indefinite pronouns (for example everything, anyone):

| the boy’s job | the box’s contents | anyone’s guess |

and after plural nouns that do not end in s:

| people’s opinions | women’s rights |

With singular nouns that end in an s sound, the extra s can be omitted if it makes the phrase difficult to pronounce (the catharsis’ effects), but it is often preferable to transpose the words and insert of (the effects of the catharsis).

Use an apostrophe alone after plural nouns ending in s:

| our neighbours’ children | other countries’ air forces |

An apostrophe is used in a similar way when the length of a period of time is specified:

| a few days’ holiday | three weeks’ time |

but notice that an apostrophe is not used in adjectival constructions such as three months pregnant.

Use an apostrophe alone after singular nouns ending in an s or z sound and combined with sake:

for goodness’ sake

Note that for old times’ sake is a plural and so has the apostrophe after the s.

Do not use an apostrophe in the possessive pronouns hers, its, ours, yours, theirs:

| a friend of yours | theirs is the kingdom of heaven |

Distinguish its (a possessive meaning ‘belonging to it’) from it’s (a contraction for ‘it is’ or ‘it has’):

| give the cat its dinner | it’s been raining |

In compounds and of phrases, use ’s after the last noun when it is singular:

| my sister-in-law’s car | the King of Spain’s daughter |

but use the apostrophe alone after the last noun when it is plural:

| the King of the Netherlands’ appeal | Tranmere Rovers’ best season |

A double possessive, making use of both of and an apostrophe, may be used with nouns and pronouns relating to people or with personal names:

| a speech of Churchill’s | that necklace of her’s |

In certain contexts the double possessive clarifies the meaning of the of: compare a photo of Mary with a photo of Mary’s. The double possessive is not used with nouns referring to an organization or institution:

| a friend of the Tate Gallery | a window of the hotel |

Use’s after the last of a set of linked nouns where the nouns are acting together:

Liddell and Scott’s Greek–English Lexicon

Beaumont and Fletcher’s comedies

but repeat ’s after each noun in the set where the nouns are acting separately:

Johnson’s and Webster’s lexicography

Shakespeare’s and Jonson’s comedies

An ’s indicates residences and places of business:

| at Jane’s | going to the doctor’s |

In the names of large businesses, endings that were originally possessive are now often acceptably written with no apostrophe, as if they were plurals: Harrods, Currys. This is the case even when the name of the company or institution is a compound, for example Barclays Bank, Citizens Advice Bureau. Other institutions retain the apostrophe, however, for example Levi’s and Macy’s, and editors should not alter a consistently applied style without checking with the author.

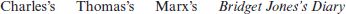

An apostrophe and s are generally used with personal names ending in an s, x, or z sound:

but an apostrophe alone may be used in cases where an additional s would cause difficulty in pronunciation, typically after longer names that are not accented on the last or penultimate syllable:

| Nicholas’ or Nicholas’s | Lord Williams’s School |

Jesus’s is the usual non-liturgical use; Jesus’ is an accepted archaism.

It is traditional to use an apostrophe alone after classical names ending in s or es:

This style should be followed for longer names; with short names the alternative Zeus’s, for instance, is permissible. When classical names are used in scientific or other contexts their possessives generally require the additional s:

Mars’ spear

but

Mars’s gravitational force

Use ’s after French names ending in silent s, x, or z, when used possessively in English:

| Dumas’s | Descartes’s |

When a singular or plural name or term is italicized, set the possessive ’s in roman:

Do not use an apostrophe in the names of wars known by their length:

Hundred Years War

It is impossible to predict with certainty whether a place or organizational name ending in s requires an apostrophe. For example:

| Land’s End | Lord’s Cricket Ground |

| Offa’s Dyke | St James’s Palace |

| St Thomas’ Hospital (not ’s) | |

but

| All Souls College | Earls Court |

| Johns Hopkins University | St Andrews |

Check doubtful instances in the New Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors, or on the institution’s own website (other websites may be unreliable), or in a gazetteer or encyclopedic dictionary.

4.2.2 Plurals

Do not use the so-called ‘greengrocer’s apostrophe’, for example lettuce’s for ‘lettuces’ or video’s for ‘videos’: this is incorrect. The apostrophe is not necessary in forming the plural of names, abbreviations, numbers, and words not usually used as nouns:

| the Joneses | several Hail Marys | three Johns |

| CDs | the three Rs | the 1990s |

| whys and wherefores | dos and don’ts | the Rule of 9s |

However, the apostrophe may be used when clarity calls for it, for example when letters or symbols are referred to as objects:

| dot the i’s and cross the t’s | she can’t tell her M’s from her N’s |

| find all the number 7’s |

Such items may also be italicized or set in quotes, with the s set in roman outside any closing quote:

subtract all the xs from the ys

subtract all the ‘x’s from the ‘y’s

4.2.3 Contraction

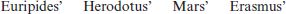

Use an apostrophe in place of missing letters in contractions, which are printed without spaces:

Except when copying older spellings, do not use an apostrophe before contractions accepted as words in their own right, such as cello, phone, plane, and flu.

When an apostrophe marks the elision of an initial or final letter or letters, such as o’, ’n’, or th’, it is not set closed up to the next character, but rather followed or preceded by a full space:

rock ’n’ roll

R ’n’ B

it’s in th’ Bible

how tender ’tis to love the babe that milks me

In contractions of the type rock ’n’ roll an ampersand may also be used: see 10.2.2.

There is no space when the apostrophe is used in place of a medial letter within a word:

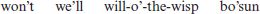

Formerly ’d was added in place of -ed to nouns and verbs ending in a pronounced vowel sound:

but a conventional ed ending is now usual in such words:

| subpoenaed | shanghaied |

The ’d construction is still found, usually in poetry and older typography, especially to indicate that an -ed is unstressed—belov’d, bless’d, curs’d, legg’d—rather than separately pronounced—belovèd, blessèd, cursèd, leggèd.

An apostrophe is still used before the suffix when an abbreviation functions as a verb:

| KO’s | OK’ing | OD’d |

4.3 Comma

4.3.1 Restrictive and non-restrictive uses

There are two kinds of relative clause, which are distinguished by their use of the comma. A defining or restrictive relative clause cannot be omitted without affecting the sentence’s meaning. It is not enclosed with commas:

Identical twins who share tight emotional ties may live longer

The people who live there are really frightened

A clause that adds information of the form and he/she is, and it was, or otherwise known as (a non-restrictive or non-defining clause) needs to be enclosed with commas. If such a clause is removed the sentence retains its meaning:

Identical twins, who are always of the same sex, arise in a different way

The valley’s people, who are Buddhist, speak Ladakhi

Note that in restrictive relative clauses either which or that may be used in British English, but in non-restrictive clauses only which may be used. Restrictive:

They did their work with a quietness and dignity which he found impressive

They did their work with a quietness and dignity that he found impressive

Non-restrictive:

This book, which is set in the last century, is very popular with teenagers

In US English which is not used for restrictive clauses, unlike British usage of which or that.

Similar principles apply to phrases in parenthesis or apposition. A comma is not required where the item in apposition is restrictive or defining—in other words, when it defines which of more than one people or things is meant:

The ancient poet Homer is credited with two great epics

My friend Julie is absolutely gorgeous

Note, however, that when the name and noun are transposed commas are then required:

Homer, the ancient poet, is credited with two great epics

Julie, my friend, is absolutely gorgeous

Use a comma or commas to mark off a non-defining or non-restrictive word, phrase, or clause which comments on the main clause or supplies additional information about it. Use a pair of commas when the apposition falls in the middle of a sentence; they function like a pair of parentheses or dashes, though they imply a closer relationship with the surrounding text:

I met my wife, Dorothy, at a dance

Their only son, David, was killed on the Somme

Ensure that a parenthetical phrase is enclosed in a pair of commas; do not use one unmatched comma:

Poppy, the baker’s wife, makes wonderful spinach and feta pies

not

Poppy, the baker’s wife makes wonderful spinach and feta pies

Do not use a comma when what follows has become part of a name:

Dave, the builder from down the road, said …

but

Bob the Builder

4.3.2 Comma splice

A comma alone should not be used to join two main clauses, or those linked by adverbs or adverbial phrases such as nevertheless, therefore, and as a result. This error is called a comma splice. Examples of this incorrect use are:

I like swimming very much, I go to the pool every week

or

He was still tired, nevertheless he went to work as usual

This error can be corrected by adding a coordinating conjunction (such as and, but, or so) or by replacing the comma with a semicolon or colon:

I like swimming very much, and go to the pool every week

He was still tired; nevertheless he went to work as usual

or by splitting it into two full sentences.

4.3.3 After an introductory clause or adverb

When a sentence is introduced by an adverb, adverbial phrase, or subordinate clause, this is often separated from the main clause with a comma:

Despite being married with five children, he revelled in his reputation as a rake

Surprisingly, Richard liked the idea

This is not essential, however, if the introductory clause or phrase is a short one specifying time or location:

In 2000 the hospital took part in a trial involving alternative therapy for babies

Before his retirement he had been a mathematician and inventor

Indeed, the comma is best avoided here so as to prevent the text from appearing cluttered.

Use a comma when a preposition is used as an adverb:

In the valley below, the villages looked very small

If commas are omitted, be vigilant for ambiguities:

In 2000 deaths involving MRSA in males increased by 66 per cent

Prefer In 2000, … or recast the sentence.

A comma should never be used after the subject of a sentence except to introduce a parenthetical clause:

The coastal city of Bordeaux is a city of stone

The primary reason that utilities are expanding their non-regulated activities is the potential of higher returns

not

The coastal city of Bordeaux, is a city of stone

The primary reason that utilities are expanding their non-regulated activities, is the potential of higher returns

When an adverb such as however, moreover, therefore, or already begins a sentence it is usually followed by a comma:

However, they may not need a bus much longer

Moreover, agriculture led to excessive reliance on starchy monocultures such as maize

When used in the middle of a sentence, however and moreover are enclosed between commas:

There was, however, one important difference

However is, of course, not followed by a comma when it modifies an adjective or other adverb:

However fast Achilles runs he will never reach the tortoise

4.3.4 Commas separating adjectives

Nouns can be modified by multiple adjectives. Whether or not such adjectives before a noun need to be separated with a comma depends on what type of adjective they are. Gradable or qualitative adjectives, for example happy, stupid, and large, can be used in the comparative and superlative and be modified by a word such as very, whereas classifying adjectives such as annual, mortal, and American cannot.

No comma is needed to separate adjectives of different types. In the following examples large and small are qualitative adjectives and black and edible are classifying adjectives:

a large black gibbon native to Sumatra

a small edible fish

A comma is needed to separate two or more qualitative adjectives:

a long, thin piece of wood

a soft, wet mixture

No comma is needed to separate two or more classifying adjectives where the adjectives relate to different classifying systems:

French medieval lyric poets

annual economic growth

randomized controlled trial

Writers may depart from these general principles in order to give a particular effect, for example to give pace to a narrative or to follow a style, especially in technical contexts, that uses few commas.

4.3.5 Serial comma

The presence or lack of a comma before and or or in a list of three or more items is the subject of much debate. Such a comma is known as a serial comma. For a century it has been part of Oxford University Press style to retain or impose this last comma consistently, to the extent that the convention has also come to be called the Oxford comma. However, the style is also used by many other publishers, both in the UK and elsewhere. Examples of the serial comma are:

mad, bad, and dangerous to know

a thief, a liar, and a murderer

a government of, by, and for the people

The general rule is that one style or the other should be used consistently. However, the last comma can serve to resolve ambiguity, particularly when any of the items are compound terms joined by a conjunction, and it is sometimes helpful to the reader to use an isolated serial comma for clarification even when the convention has not been adopted in the rest of the text. In

cider, real ales, meat and vegetable pies, and sandwiches

the absence of a comma after pies would imply something unintended about the sandwiches. In the next example, it is obvious from the grouping afforded by the commas that the Bishop of Bath and Wells is one person, and the bishops of Bristol, Salisbury, and Winchester are three people:

the bishops of Bath and Wells, Bristol, Salisbury, and Winchester

If the order is reversed to become

the bishops of Winchester, Salisbury, Bristol, and Bath and Wells

then the absence of the comma after Bristol would generate ambiguity: is the link between Bristol and Bath rather than Bath and Wells?

In a list of three or more items, use a comma before a final extension phrase such as etc., and so forth, and the like:

potatoes, swede, carrots, turnips, etc.

candles, incense, vestments, and the like

It is important to note that only elements that share a relationship with the introductory material should be linked in this way. In:

the text should be lively, readable, and have touches of humour

only the first two elements fit syntactically with the text should be; the sentence should rather be written:

the text should be lively and readable, and have touches of humour

4.3.6 Figures

In general text most styles use commas to separate large numbers into units of three, starting from the right:

£2,200

2,016,523,354

but it will depend on the nature of the material; for example technical texts use a thin or non-breaking space as a thousands separator; for more about numbers see Chapter 11 and 14.1.3.

4.3.7 Use in letters

In formal contexts commas are used after some salutations in letters and before the signature:

Dear Sir, …

Yours sincerely, …

US business letters use a colon after the greeting. On both sides of the Atlantic, however, punctuation is now sometimes omitted, particularly after email salutations (if any) and in informal writing. For more on addresses see 6.2.4.

4.3.8 Other uses

A comma is often used to introduce direct speech: see 9.2.2.

A comma is placed after namely and for example when part of a parenthetical phrase:

We categorized them into three groups—namely, urban, rural, or mixed

Take, for example, the shutting of a small girl in a locker by three older girls

but no comma is needed when introducing an item or list:

The theoretical owners of the firm, namely the shareholders …

If they are off the road, for example on a grass verge, the district council then has to be notified

A comma is generally required after that is. Oxford style does not use a comma after i.e. and e.g. to avoid double punctuation, but US usage does (see 21.2.1).

4.4 Semicolon

The semicolon marks a separation that is stronger than a comma but less strong than a full point. It divides two or more main clauses that are closely related and complement or parallel each other, and that could stand as sentences in their own right. When one clause explains another a colon is more suitable (see 4.5).

Truth ennobles man; learning adorns him

The road runs through a beautiful wooded valley; the railway line follows it closely

In a sentence that is already subdivided by commas, a semicolon can be used instead of a comma to indicate a stronger division:

He came out of the house, which lay back from the road, and saw her at the end of the path; but instead of continuing towards her, he hid till she had gone

In a list where any of the elements themselves contain commas, use a semicolon to clarify the relationship of the components:

They pointed out, in support of their claim, that they had used the materials stipulated in the contract; that they had taken every reasonable precaution, including some not mentioned in the code; and that they had employed only qualified workers, all of whom were very experienced

This is common in lists with internal commas, where semicolons structure the internal hierarchy of its components:

I should like to thank the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford; the staff of the Bodleian Library, Oxford; and the staff of the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Since it can be confusing and unattractive to begin a sentence with a symbol, especially one that is not a capital letter, the semicolon can replace a full point:

Let us assume that a is the crude death rate and b life expectancy at birth; a will signal a rise in …

4.5 Colon

The colon points forward: from a premise to a conclusion, from a cause to an effect, from an introduction to a main point, from a general statement to an example. It fulfils the same function as words such as namely, that is, as, for example, for instance, because, as follows, and therefore. Material following a colon need not contain a verb or be able to stand alone as a sentence:

That is the secret of my extraordinary life: always do the unexpected

It is available in two colours: pink and blue

Use the colon to introduce a list; formerly a colon followed by a dash : — was common practice, but now this style should be avoided unless you are reproducing antique or foreign-language typography:

We are going to need the following: flashlight, glass cutter, skeleton key, …

She outlined the lives of three composers: Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert

The word following a colon is not capitalized in British English (unless it is a proper name, of course), but in US English it is often capitalized if it introduces a grammatically complete sentence:

Mr Smith had committed two sins: First, his publication consisted principally of articles reprinted from the London Review …

A colon should not precede linking words or phrases in the introduction to a list, and should follow them only where they are introduced by a main clause:

She outlined the lives of three composers, namely, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert

She gave this example: Mozart was chronically short of money

Do not use a colon to introduce a statement or a list that completes the sentence formed by the introduction:

Other Victorian authors worth studying include Thackeray, Trollope, and Dickens

A dash can also be used in a similar way to a colon, but they are not interchangeable: a dash tends to be more informal, and to imply an afterthought or aside (see 4.11.2).

A colon is used after the title of a work to introduce the subtitle. It may be followed by a capital or a lower-case letter (Oxford style uses a capital):

Finding Moonshine: A Mathematician’s Journey through Symmetry

Monster: The Autobiography of an L.A. Gang Member

A colon may introduce direct speech: see 9.2.2.

4.6 Full point

The full point is also called full stop or, particularly in US use, period. Full points are used to mark the end of sentences, and in some classes of abbreviation. Do not use a full point in headings, addresses, or titles of works, even where these take the form of a full sentence:

All’s Well that Ends Well

Mourning Becomes Electra

If the full point of an abbreviation closes the sentence, there is no second point:

a generic term for all polished metal—brass, copper, steel, etc.

I came back at 3 a.m.

For more on abbreviations see Chapter 10. See 9.2.3 for a discussion of the relative placing of full p11oints and closing quotation marks.

4.7 Ellipses

An ellipsis (plural ellipses) is a series of points (…) signalling that words have been omitted from quoted matter, or that part of a text is missing or illegible. Omitted words are marked by three full points (not asterisks) printed on the line. They can be set as a single character (Unicode code point U+2026 HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS), and many word processors will autocorrect three dots into a single glyph. Some publishers prefer either normal word spaces or fixed (narrower) spaces between the points (… or …). A normal word space is set either side in running text:

I will not … sulk about having no boyfriend

Political language … is designed to make lies sound truthful

An ellipsis at the end of an incomplete sentence is not followed by a fourth full point. When an incomplete sentence is an embedded quotation within a larger complete sentence, the normal sentence full point is added after the final quotation mark:

I only said, ‘If we could …’.

A comma immediately before or after an ellipsis can generally be suppressed, unless it is helpful to the sense. If the sentence before an ellipsis ends with a full point it is Oxford practice to retain the point before the ellipsis, closed up to the preceding text. Every sequence of words before or after four points should be functionally complete. This indicates that at least one sentence has been omitted between the two sentences. If what follows an ellipsis begins with a complete sentence in the original, it should begin with a capital letter:

I never agreed to it. … It would be ridiculous.

For more details on the use of ellipses in presenting quoted material see 9.3.3.

Sentences ending with a question mark or exclamation mark retain these marks before or after the ellipsis:

Could we …?

Could we do it? … It might just be possible …!

An ellipsis can be used to show a trailing off on the part of a speaker, or to create a dramatic or ironic effect:

The door opened slowly …

I don’t … er … understand

It is also used, like etc., to show the continuation of a sequence that the reader is expected to infer:

in 1997, 1999, 2001 …

the gavotte, the minuet, the courante, the cotillion, the allemande, …

Note that other languages use ellipses in different ways: Chinese and Japanese, for example, use six dots in two groups of three. For ellipses in mathematical notation see 14.6.2.

4.8 Question mark

4.8.1 Typical uses

Question marks are used to indicate a direct question. Do not use a question mark when a question is implied by indirect speech:

He wants to know whether you are coming

She asked why the coffee hadn’t materialized

Requests framed as questions out of idiom or politeness do not normally take question marks:

May I take this opportunity to wish you all a safe journey

Will everyone please stand to toast the bride and groom

although a question mark can seem more polite than a full point:

Would you kindly let us know whether to expect you?

I wonder if I might ask you to open the window?

Matter following a question mark begins with a capital letter:

You will be back before lunch, right? About noon? Good.

although short questions that are embedded in another sentence are not followed by a capital:

Where now? they wonder

Embedded questions that are not in quotation marks are often not capitalized. The question mark follows the question at whatever point it falls in a sentence:

The question is, what are the benefits for this country? What about the energy?

When the question is presented as direct speech (whether voiced or formulated in someone’s mind), it should be capitalized and set in quotation marks:

‘Why not?’ she wondered

She wondered, ‘Why not?’

Note that a question mark at the end of a sentence functions like a full point, and that double punctuation should not be used. For a full account of the use of punctuation with quotation marks see 9.2.3.

4.8.2 Use to express uncertainty

Use a question mark immediately before or after a word, phrase, or figure to express doubt, placing it in parentheses where it would otherwise appear to punctuate or interrupt a sentence. Strictly, a parenthetical question mark should be set closed up to a single word to which it refers, but with a normal interword space separating the doubtful element from the opening parenthesis if more of the sentence is contentious:

The White Horse of Uffington (? sixth century BC) was carved …

Homer was born on Chios(?)

However, this distinction is probably too subtle for all but specialized contexts, and explicit rewording may well be preferable. The device does not always make clear what aspect of the text referred to is contentious: in the latter example it is Homer’s birthplace that is in question, but a reader might mistakenly think it is the English spelling (Chios) of what is Khios in Greek.

A question mark is sometimes used to indicate that a date is uncertain; in this context it may precede or follow the date. It is important to ensure that the questionable element is clearly identified, and this may necessitate the use of more than one question mark. In some styles the exact spacing of the question mark is supposed to clarify its meaning, but the significance of the space may well be lost on the reader, who will not grasp the difference between the following forms:

| ? 1275–1333 | ?1275–1333 |

or

| 1275–1333 ? | 1275–1333? |

It would be clearer to present the first form with two question marks and the second with one only; and in general the question mark is better placed in the after position:

| 1275?–1333? | 1275?–1333 |

Similarly, care must be taken not to elide numbers qualified by a question mark if the elision may introduce a false implication: in a context where number ranges are elided, 1883–1888? makes clear that the first date is certain but the second in question; 1883–8? suggests that the entire range is questionable.

More refined use of the question mark, with days and months as well as years, is possible but tricky. While 10? January 1731 quite clearly throws only the day into question, 10 January? 1731 could, in theory, mean that the day and year are known but the month is only probable. In such circumstances it is almost always preferable to replace or supplement the form with some explanation:

He made his will in 1731 on the 10th of the month, probably January (the record is unclear)

or

He made his will on 10 January? 1731 (the document is damaged and the month cannot be clearly read)

A distinction is usually understood between the use of a question mark and c. (circa) with dates: the former means that the date so qualified is probable, the latter that the event referred to happened at an unknown time, before, on, or after the date so qualified. (Note that the period implied by c. is not standard: c.1650 probably implies a broader range of possible dates than does c.1653.)

A question mark in parentheses is sometimes used to underline sarcasm or for other humorous effect:

With friends (?) like that, you don’t need enemies

4.9 Exclamation mark

The exclamation mark—also called an exclamation point in the US—follows emphatic statements, commands, and interjections expressing emotion. In mathematics, an exclamation mark is the factorial sign: 4! = 4 × 3 × 2 × 1 = 24; 4! is pronounced ‘four factorial’. In computing it is a delimiter symbol, sometimes called a ‘bang’. See Chapter 14.

Avoid overusing the exclamation mark for emphasis. Although often employed humorously or to convey character or manner in fiction, in serious texts it should be used only minimally.

As with a question mark, an exclamation mark at the end of a sentence functions like a full point, and double punctuation should not be used. For a full account of the use of punctuation with quotation marks see 9.2.3.

4.10 Hyphen

For the use of hyphens in compound words and in word division see Chapter 3.

4.11 Dashes

4.11.1 En rule

The en rule (US en dash) (–) (Unicode code point U+2013 EN DASH) is longer than a hyphen and half the length of an em rule. (See 4.11.2 for a definition of an em). Many British publishers use an en rule with space either side as a parenthetical dash, but Oxford and most US publishers use an em rule.

Use the en rule closed up in elements that form a range:

In specifying a range use either the formula from … to … or xxxx–xxxx, never a combination of the two (the war from 1939 to 1945 or the 1939–45 war, but not the war from 1939–45). For more on ranges see Chapter 11.

The en rule is used closed up to express connection or relation between words; it means roughly to or and:

| Dover–Calais crossing | Ali–Foreman match |

| editor–author relationship | Permian–Carboniferous boundary |

It is sometimes used like a solidus to express an alternative, as in an on–off relationship (see 4.13.1).

Use an en rule between names of joint authors or creators to show that it is not the hyphenated name of one person. Thus the Lloyd–Jones theory involves two people (en rule), the Lloyd-Jones theory one person (hyphen), and the Lloyd-Jones–Scargill talks two people (hyphen and en rule).

In compound nouns and adjectives derived from two names an en rule is usual:

Marxism–Leninism (Marxist theory as developed by Lenin)

Marxist–Leninist theory

although for adjectives of this sort a hyphen is sometimes used. Note the difference between Greek–American negotiations (between the Greeks and the Americans, en rule) and his Greek-American wife (American by birth but Greek by descent, hyphen). Elements, such as combining forms, that cannot stand alone take a hyphen, not an en rule: Sino-Soviet, Franco-German but Chinese–Soviet, French–German.

Spaced en rules may be used to indicate individual missing letters:

the Earl of H – – w – – d

‘F – – – off!’ he screamed

The asterisk is also used for this purpose (see 4.15).

4.11.2 Em rule

The em rule (US em dash) (—) (Unicode code point U+2014 EM DASH) is twice the length of an en rule. (An em is a unit for measuring the width of printed matter, originally reckoned as the width of a capital roman M, but in digital fonts equal to the current typesize, so an em in 10 point text is 10 points wide.) Oxford and most US publishers use a closed-up em rule as a parenthetical dash; other British publishers use the en rule with space either side.

No punctuation should precede a single dash or the opening one of a pair. A closing dash may be preceded by an exclamation or question mark, but not by a comma, semicolon, colon, or full point. Do not capitalize a word, other than a proper noun, after a dash, even if it begins a sentence.

A pair of dashes expresses a more pronounced break in sentence structure than commas, and draws more attention to the enclosed phrase than brackets:

The party lasted—we knew it would!—far longer than planned

There is nothing—absolutely nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats

Avoid overuse of the dash in this context and the next; certainly, no more than one pair of dashes should be used in one sentence.

A single parenthetical dash may be used to introduce a phrase at the end of a sentence or replace an introductory colon. It has a less formal, more casual feel than a colon, and often implies an afterthought or aside:

I didn’t have an educated background—dad was a farm labourer

Everyone understands what is serious—and what is not

They solicit investments from friends, associates—basically, anyone with a wallet

Do not use it after a colon except in reproducing antique or foreign-language typography.

Use an em rule spaced to indicate the omission of a word, and closed up to indicate the omission of part of a word:

We were approaching — when the Earl of C— disappeared

Asterisks or two or more en rules are also employed for this purpose (see 4.11.1, 4.15).

An em rule closed up can be used in written dialogue to indicate an interruption, much like an ellipsis indicates trailing off:

‘Does the moon actually—?’

‘They couldn’t hit an elephant at this dist—’

A spaced em rule is used in indexes to indicate a repeated word (see Chapter 19). Two spaced em rules (—) are used in some styles (including Oxford’s) for a repeated author’s name in successive bibliographic entries (see Chapter 18).

4.12 Brackets

The symbols (), [ ], {}, and < > are all brackets. Round brackets () are also called parentheses; [ ] are square brackets to the British, though often simply called brackets in US use; { } are braces or curly brackets; and < and > are angle brackets. For the use of brackets in mathematics see 14.6.5.

4.12.1 Parentheses

Parentheses or round brackets are used for digressions and explanations, as an alternative to paired commas or dashes. They are also used for glosses and translations, to give or expand abbreviations, and to enclose ancillary information, references, and variants:

He hopes (as we all do) that the project will be successful

Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia)

They talked about power politics (Machtpolitik)

TLS (Times Literary Supplement)

£2 billion ($3.1 billion)

Geoffrey Chaucer (1340–1400)

Parentheses are also used in enumerating items in a list (see Chapter 15).

4.12.2 Square brackets

Square brackets [ ] are used chiefly for comments, corrections, or translations made by a subsequent author or editor:

They [the Lilliputians] rose like one man

Daisy Ashford wrote The Young Visiters [sic]

For more on the use of brackets in quotations see Chapter 9.

4.12.3 Braces

Braces or curly brackets { } are used chiefly in mathematics, computing, prosody, music, and textual notation; their usage varies within each of these fields. A single brace may be used set vertically to link two or more lines of material together:

4.12.4 Angle brackets

Angle brackets < >, the less-than or greater-than signs (Unicode code points U+003C and U+003E respectively), sometimes known as wide angle brackets, are used in pairs to enclose computer code or tags. They are used singly in computing, economics, mathematics, and scientific work to show the relative size of entities, the logical direction of an argument, etc. In etymology they are used singly to mean ‘from, derived from’ (<) and ‘gives’ or ‘has given’ (>):

< Urdu murġῑ hen > murġ bird, fowl

In mathematics and science narrow angle brackets 〈 〉 are used (U+27E8 and U+27E9 MATHEMATICAL LEFT and RIGHT ANGLE BRACKET respectively); in these fields < >, respectively, signify ‘less than’ and ‘greater than’. See 14.6.5.

Narrow angle brackets are also used to enclose conjecturally supplied words where a source is defective or illegible:

He came from Oxon: to be 〈pedagogue〉 to a neighbour of mine

Avoid angle brackets around URLs (see 18.8.3).

4.12.5 Punctuation with brackets

Rules governing punctuation are the same regardless of the type of bracket used. A complete sentence within brackets is capitalized and ends in a full point unless the writer has chosen to place it within another sentence:

The discussion continued after dinner. (This was inevitable.)

The discussion continued after dinner (this was inevitable).

No punctuation precedes the opening parenthesis except in the case of terminal punctuation before a full sentence within parentheses, or where parentheses mark divisions in the text:

We must decide (a) where to go, (b) whom to invite, and (c) what to take with us

4.12.6 Nested brackets

In normal running text, avoid using brackets within brackets. This is sometimes inevitable, as when matter mentioned parenthetically already contains parentheses. In such cases Oxford prefers double parentheses to square brackets within parentheses (the usual US convention). Double parentheses are closed up, without spaces:

the Chrysler Building (1928–30, architect William van Alen (not Allen))

the album’s original title ((I) Got My Mojo Working (But It Just Won’t Work on You)) is seldom found in its entirety

References to, say, law reports and statutes vary between parentheses and square brackets; the prescribed conventions should be followed (see also Chapter 13).

4.13 Solidi and verticals

4.13.1 Solidus

The solidus (/, plural solidi) is known by many terms, such as the slash or forward slash, stroke, oblique, virgule, diagonal, and shilling mark. It is in general used to express a relationship between two or more things. The most common use of the solidus is as a shorthand to denote alternatives, as in either/or, his/her, on/off, s/he (she or he). The solidus is generally closed up, both when separating two complete words (and/or) and between parts of a word (s/he).

The symbol is sometimes misused to mean and rather than or, and so it is normally best in text to spell out the alternatives explicitly in cases which could be misread (his or her; on or off ). An en rule can sometimes substitute for a solidus, as in an on–off relationship. In addition to indicating alternatives, the solidus is used in other ways:

In scientific and technical work the solidus is used to indicate ratios, as in miles/day, metres/second. In computing it is called a forward slash, to differentiate it from a backward slash, backslash, or reverse solidus (\): each of these is used in different contexts as a separator (see 14.5.3,14.6.3).

4.13.2 Vertical

The vertical rule, line, or bar (|), also called the upright rule or simply the vertical, has specific uses as a technical symbol in the sciences (see 14.5.3, 14.6.5) and in specialist subjects such as prosody. More commonly, it may be used, with a space either side, to indicate the separation of lines where text is run on rather than displayed, for instance for poems, plays, correspondence, libretti, or inscriptions:

The English winter—ending in July | To recommence in August

A solidus may also be used for this purpose. When written lines do not coincide with verse lines it may be necessary to indicate each differently: in such cases use a vertical for written lines and a solidus for verse.

When more than one speaker or singer is indicated in a run-together extract, the break between different characters’ lines is indicated by two verticals (set closed up to each other).

In websites, spaced vertical lines are sometimes used to separate elements in a menu:

News | History | Gallery | Music | Links | Contact

The vertical line is used in the syntax of some computing languages and scripts, and is sometimes referred to as a pipe.

4.14 Quotation marks

Quotation marks, also called inverted commas, are of two types: single (‘’) and double (“ ”). Upright quotation marks (' or ") are also sometimes used. People writing for the Internet should note that single quotation marks are regarded as easier to read on a screen than double ones. British practice is normally to enclose quoted matter between single quotation marks, and to use double quotation marks for a quotation within a quotation:

‘Have you any idea’, he said, ‘what “red mercury” is?’

The order is often reversed in newspapers, and uniformly in US practice:

“Have you any idea,” he said, “what ‘red mercury’ is?”

If another quotation is nested within the second quotation, revert to the original mark, either single–double–single or double–single–double.

Displayed quotations of poetry and prose take no quotation marks. In reporting extended passages of speech, use an opening quotation mark at the beginning of each new paragraph, but a closing one only at the end of the last. For more on quotations see Chapter 9, which also covers direct speech and the relative placing of quotation marks with other punctuation.

Use quotation marks and roman (not italic) type for titles of short poems, short stories, and songs (see Chapter 8):

‘Raindrops Keep Falling on my Head’

‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’

Use quotation marks for titles of chapters in books, articles in periodicals, and the like:

Mr Brock read a paper entitled ‘Description in Poetry’

But omit quotation marks when the subject of the paper is paraphrased:

Mr Brock read a paper on description in poetry

not

Mr Brock read a paper on ‘Description in Poetry’

Quotation marks may be used to enclose an unfamiliar or newly coined word or phrase, or one to be used in a technical sense:

‘hermeneutics’ is the usual term for such interpretation

the birth or ‘calving’ of an iceberg

the weird and wonderful world of fan fiction, or ‘fanfic’

They are often used as a way of distancing oneself from a view or claim, or of apologizing for a colloquial or vulgar expression:

Authorities claim to have organized ‘voluntary’ transfers of population

I must resort to a ‘seat of the pants’ approach

Kelvin and Danny are ‘dead chuffed’ with its success

Such quotation marks should be used only at the first occurrence of the word or phrase in a work. Note that quotation marks should not be used to emphasize material.

Quotation marks are not used around the names of houses or public buildings:

| Chequers | the Barley Mow |

4.15 Asterisk

A superscript asterisk * is used in text as a pointer to an annotation or footnote, especially in books that have occasional footnotes rather than a formal system of notes (see also 14.1.6). It can also indicate a cross-reference in a reference work:

Thea *Porter and Caroline *Charles created dresses and two-piece outfits based on gypsy costume

Asterisks may be used to indicate individual missing letters, with each asterisk substituting for a missing letter and closed up to the next asterisk: that b******! En rules are also used for this purpose (see 4.11.1).

On websites and in emails asterisks are sometimes used to indicate emphasis, in place of quotation marks, or to show where italicization would normally be used, for example in the titles of books or other works that are mentioned:

The engagement, the debate, the willingness to engage—*that’s* what’s important

Maybe some people can handle these little romances as *harmless fun*, but I can’t

Asterisks should not be used in place of dots for ellipsis.