CHAPTER 11

Numbers and dates

11.1 Numbers: general principles

11.1.1 Introduction

This chapter mainly covers general texts and the humanities; more detailed information about dealing with numbers in scientific contexts can be found in Chapter 14, particularly 14.1, and 14.6.1 discusses typography in mathematical notation.

11.1.2 Figures or words?

The main stylistic choice to be made when dealing with numbers is whether to express them in figures or in words. It is normal to determine a threshold below which numbers are expressed in words and above which figures are used; depending on the context, the threshold may vary. In non-technical contexts, Oxford style is to use words for numbers below 100; in technical contexts numbers up to and including ten are spelled out. In specialist contexts the threshold may, with good reason, be different: in some books about music, for example, numbers up to and including twelve are spelled out (there being twelve notes in the diatonic scale). The threshold provides only a general rule: there are many exceptions to it, as described below. On websites different rules may apply: figures tend to be used more than words.

Large round numbers may be expressed in a mixture of numerals and words (6 million; 1.5 million) or entirely in words (six million; one and a half million). In some contexts it makes better sense to use a rounded number than an exact one, such as a population of 60,000 rather than of 60,011. This is particularly true if the idea of approximation or estimation is expressed in the sentence by such words as some, estimated, or about. Rounded approximations may be better expressed in words if the use of figures will confer a false sense of exactitude:

about a thousand not about 1000

some four hundred not some 400

Particularly where quantities are converted from imperial to metric (or vice versa), beware of qualifying a precise number with about, approximately, etc.: about three kilometres should not be converted to about 1⅞ miles.

In expressing approximate figures some styles traditionally preferred more than to over. Modern usage tends to treat them as synonyms:

She was born in Oxford and has lived in Ireland for over twenty-five years

She was born in Oxford and has lived in Ireland for more than twenty-five years

although there are certain contexts in which one or the other is syntactically correct:

We spent a lot of time together, well over two months, and so we really got to know each other

There’s more than one way of tackling this problem

or sounds more natural, e.g. in reference to age:

Applicants must be over 25 and have had a clean driving licence for more than five years

Use words in informal phrases that do not refer to exact numbers:

talking nineteen to the dozen

I have said so a hundred times

she’s a great woman—one in a million

a thousand and one odds and ends

When a sentence contains one or more figures of 100 or above, a more consistent look may be achieved by using Arabic numerals throughout that sentence: for example, 90 to 100 (not ninety to 100) and 30, 76, and 105 (not thirty, seventy-six, and 105). This convention holds only for the sentence where this combination of numbers occurs: it does not influence usage elsewhere in the text unless a similar situation exists.

In some contexts a different approach is necessary. For example, it is sometimes clearer when two sets of figures are mixed to use words for one and figures for the other, as in thirty 10-page pamphlets or nine 6-room flats. This is especially useful when the two sets run throughout a sustained expanse of text (as in comparing quantities): Anything more complicated, or involving more than two sets of quantities, will probably be clearer if presented in a table.

the manuscript comprises thirty-five folios with 22 lines of writing, twenty with 21 lines, and twenty-two with 20 lines

Spell out ordinal numbers—first, second, third, fourth—except when quoting from another source. In the interests of saving space they may also be expressed in numerals in notes and references (see also 11.6.2 below). Use words for ordinal numbers in names, and for numerical street names (apart from avenue names in Manhattan—see 6.2.4):

| the Third Reich | the Fourth Estate | a fifth columnist |

| Sixth Avenue | a Seventh-Day Adventist |

It is customary to use words for numbers that fall at the beginnings of sentences:

Eighty-four different kinds of birds breed in the Pine Barrens

‘How much?’ ‘Fifty cents’

In such contexts, to avoid spelling out cumbersome numbers, recast the sentence, writing for example The year 1849 … instead of Eighteen forty-nine …

Use figures for ages expressed in cardinal numbers, and words for ages expressed as ordinal numbers or decades:

| a girl of 15 | a 33-year-old man |

| between her teens and twenties | in his thirty-third year |

| in the twenty-first century |

In less formal or more discursive contexts (especially in fiction), ages may instead be spelled out, as may physical attributes:

| a two-year-old | a nine-inch nail |

Words can supplement or supersede figures in legal or official documents, where absolute clarity is required:

the sum of nine hundred and forty-three pounds sterling (£943)

a distance of no less than two hundred (200) yards from the plaintiff

Figures are used for:

11.1.3 Punctuation

When written in words, compound numbers are hyphenated (see 11.1.6 for fractions):

| ninety-nine | one hundred and forty-three |

| in her hundred-and-first year |

In non-technical contexts commas are generally used in numbers of four figures or more:

| 1,863 | 12,456 | 1,461,523 |

In technical and foreign-language work use a thin space (see 14.1.3):

| 14 785 652 | 1 000 000 | 3.141 592 |

In tabular matter, numbers of only four figures have no thin space, except where necessary to help alignment with numbers of five or more figures.

There are no commas in years (with the exception of long dates such as 10,000 BC), page numbers, column or line numbers in poetry, mathematical workings, house or hotel-room numbers, or in library call or shelf numbers:

| 1979 | 1342 Madison Avenue |

| Bodl. MS Rawl. D1054 | BL, Add. MS 33746 |

11.1.4 Number ranges

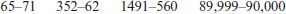

Numbers at either end of a range are linked with an en rule. A span of numbers is often elided to the fewest figures possible:

but retain as many digits as necessary where they change across the range:

In any event, do not elide digits in (or ending with) the group 10 to 19 because of the way they are read or spoken:

However, some editorial styles vary greatly in their treatment: for example some require no elision, some elide to the final two digits, and some don’t elide multiples of 10 or 100 (30–32; 100–101).

Even in elided styles all digits may be preserved in more formal contexts, such as titles and headings, and in expressing people’s vital dates:

Charles Dickens (1812–1870)

The National Service of British Seamen, 1914–1918

Turbulent years, 1763–1770

Dates that cross the boundary of a century should not be elided: write 1798–1810, 1992–2001. Spans in BC always appear in full, because an elided second date could be misread as a complete year: 185–22 BC is a century longer than 185–122 BC, and dates for, say, Horace (65–8 BC) might appear to the unwary to express a period of three rather than fifty-seven years.

When referring to events known to have occurred between two dates, historians often employ a multiplication symbol: 1225 × 1232 (or in some styles 1225 × 32) means ‘no earlier than 1225 and no later than 1232’. The multiplication sign is also useful where one element in a range is itself a range: 1225 × 32–1278.

In specifying a range use either the formula from xxxx to xxxx or xxxx–xxxx; take care to avoid the mistake of combining the two. It is the war from 1939 to 1945 or the 1939–45 war, never the war from 1939–45. The same applies to the construction ‘between … and …’: the period between 1998 and 2001 or the period 1998–2001, but not the period between 1998–2001. For ranges that include a negative value, it is best to use words to avoid confusion between a negative number and a dash, or to prevent an en rule clashing with a minus sign: 95% confidence interval = -743.23 to -557.28 not 95% CI = -743.23 – -557.28.

When describing a range in figures, repeat the quantity as necessary to avoid ambiguity:

| 1000–2000 litres | 1 billion to 2 billion light years away |

The elision 1–2000 litres means that the amount starts at only 1 litre, and 1 to 2 billion light years away means that the distance begins only 1 light year away.

For ranges that include a unit, the unit symbol does not need to be repeated (45.6–50.2 kg) unless the symbol is normally closed up (14°–18° [of angle])

A solidus replaces the en rule for a period of one year reckoned in a format other than the normal calendar extent: 49/8 BC, the tax year 1934/5. A span of years in this style is joined by an en rule as normal: 1992/3–2001/2.

Use a comma to separate successive references to individual page numbers: 6, 7, 8; use an en rule to connect the numbers if the subject is continuous from one page to another: 6–8.

11.1.5 Singular or plural?

Whether they are written as words or figures, numbers are pluralized without an apostrophe (see also 4.2.2):

| the 1960s | the temperature was in the 20s |

| they arrived in twos and threes | she died in her nineties |

Plural phrases take plural verbs where the elements enumerated are considered severally:

Ten miles of path are being repaved

Around 5,000 people are expected to attend

Plural numbers considered as single units take singular verbs:

Ten miles of path is a lot to repave

More than 5,000 people is a large attendance

When used as the subject of a quantity, words like number, percentage, and proportion are singular with a definite article and plural with an indefinite:

The percentage of people owning a mobile phone is higher in Europe

A proportion of pupils are inevitably deemed to have done badly

None in the sense no one person takes the singular:

Later, 26 children and one teacher went to hospital, but none was seriously injured

but in the sense of not any takes the plural verb:

He had hoped to receive parking permits for residents but none were forthcoming

The numerals hundred, thousand, million, billion, trillion, etc. are singular unless they refer to indefinite quantities:

| two dozen | about three hundred |

| some four thousand | more than five million |

but

| dozens of friends | hundreds of times |

| thousands of petals | millions of stars |

Note that a billion is a thousand million (1,000,000,000 or 109), and a trillion is a million million (1012). In Britain a billion was formerly a million million (1012) and a trillion a million million million (1018); in France, Germany, and elsewhere these values are still used.

11.1.6 Fractions and decimals

Fractions in mathematical contexts are discussed in 14.6.6. In other material, spell out simple fractions in running text. When fractions are spelled out they are traditionally hyphenated:

| two-thirds of the country | one and three-quarters |

| one and a half |

Hyphenate compounded numerals in compound fractions such as nine thirty-seconds of an inch; the numerator and denominator are hyphenated unless either already contains a hyphen. Do not use a hyphen between a whole number and a fraction: one and seven-eighths rather than one-and-seven-eighths. Combinations such as half a mile and half a dozen should not be hyphenated, but write a half-mile and a half-dozen.

In statistical matter use specially designed fractions where available (½, ¾, etc.), which have a diagonal bar—the Unicode block ‘Number Forms’ has a range of single-character fractions. The form of fraction with a horizontal bar (e.g.  ) is satisfactory—even in running text—if presented in TeX, which subtly adjusts interline spacing and character size and spacing, but if not set in TeX, seldom looks elegant. In non-technical running text, set complex fractions in text-size numerals with a solidus between (19/100).

) is satisfactory—even in running text—if presented in TeX, which subtly adjusts interline spacing and character size and spacing, but if not set in TeX, seldom looks elegant. In non-technical running text, set complex fractions in text-size numerals with a solidus between (19/100).

Decimal fractions may also be used: 12.66 rather than 12⅔, 99.9 rather than 99 and 9/10. Decimal fractions are always printed in figures. They cannot be plural, or take a plural verb. For values below one the decimal is preceded by a zero: 0.76 rather than .76. Exceptions are quantities (such as probabilities) that never exceed one, although authorities differ on this; if house style does not specify, it is best to follow the author’s notation.

Decimals are punctuated with the full point on the line. In the UK decimal currency was formerly treated differently, with the decimal point set in medial position (£24·72), but this style has long been out of favour.

Note that European languages, and International Standards Organization (ISO) publications in English, use a comma to denote a decimal sign, so that 2.3 becomes 2,3.

For the use of decimals in tables see Chapter 15.

11.2 Numbers with units of measure

11.2.1 General principles

Generally speaking, figures should be used with units of measurement, percentages, and expressions of quantity, proportion, etc.:

a 70–30 split

6 parts gin to 1 part dry vermouth

the structure is 83 feet long and weighs 63 tons

10 per cent of all cars sold

Note that per cent rather than % is used in running text in non-technical work, and that US English has percent, closed up.

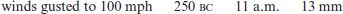

Use figures, followed by a space, with abbreviated forms of units, including units of time, and with symbols:

although % is commonly closed up, contrary to SI guidelines.

11.2.2 Singular and plural units with numbers

Note that units of measurement retain their singular form when part of hyphenated compounds before other nouns:

| a five-pound note | a two-mile walk |

| a six-foot wall | a 100-metre race |

Elsewhere, units are pluralized as necessary, but not if the quantity or number is less than one:

| two kilos or 2 kilos | three miles or 3 miles |

| 0.568 litre | half a pint |

For a fuller discussion of scientific units see Chapter 14. Do not add ‘s’ to unit symbols (cm, ml) in scientific work; see 14.1.3 and 14.1.4.

11.2.3 Currencies

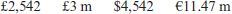

Amounts of money may be spelled out in words with the unit of currency, but are more often printed in numerals with the symbols or abbreviations:

| twenty-five pounds | thirteen dollars | seventy euros |

| £25 | $13 | €70 |

Round numbers lend themselves to words better than do precise amounts, though even these may need to be spelled out where absolute clarity is vital, as in legal documents. For amounts of millions and above, and for thousands in financial contexts, it is permissible to combine symbols, numerals, words, and abbreviations, according to the conventions of the context in which they appear: £5 million, US$15 billion.

Where symbols or abbreviations are used, such as £ (pounds), $ (dollars), € (euros), ₹ (rupees), they precede the figures. As several countries use the dollar, if there is any ambiguity use the accepted prefix (A$, US$). There is no space after symbols, but some styles use a space after abbreviations; this is acceptable if imposed consistently within a work:

Use 00 after the decimal point only if a sum appears in context with other fractional amounts:

They bought at £8.00 and sold at £11.50

Amounts in pence, cents, or other smaller units are set with the numeral close up to the abbreviation, which has no full point: 56p or 56¢ rather than £0.56 or $0.56. Mixed amounts do not include the pence/cent abbreviation: £15.30 rather than £15.30p.

Amounts in pre-decimal British currency (before February 1971) are expressed in pounds, shillings, and pence—£.s.d. In Oxford style these are italic with a normal space separating the elements:

Income tax stood at 8s. 3d. in the £

The tenth edition cost £1 10s. 6d. in 1956

Other styles render them closed up, in roman with full points:

The statue was sold at auction for £76.10s.9d. in Manchester

The international standard three-letter currency code (ISO 4217:2008) is used in trade, commerce, and banking, and the commonest currencies are well known enough to be used without explanation even in lay texts; the amount is prefixed by the code and a normal space: GBP 500; EUR 40,000; USD 1 million. Less familiar currencies will need explanation at first mention: Macanese pataca (MOP) 1600.

11.3 Times of day

The formulation of times of day is a matter of editorial style, and different forms are more or less appropriate to particular contexts. It is customary to use words, and no hyphens, with reference to whole hours and to fractions of an hour:

| four (o’clock) | half past four | a quarter to four |

Use o’clock only with the exact hour, and with time expressed in words: four o’clock, not half past four o’clock or 4 o’clock. Do not use o’clock with a.m. or p.m., but rather write, for example, eight o’clock in the morning. Use figures with a.m. or p.m.: 4 p.m. Correctly, 12 a.m. is midnight and 12 p.m. is noon; but since this is not always understood, it may be necessary to use the explicit 12 midnight and 12 noon. The twenty-four-hour clock avoids the use of a.m. and p.m.: 12.00 is noon, 24.00 is midnight. In British English either a colon or a full point as a separator is acceptable if applied consistently.

In the twelve-hour clock, use figures when minutes are to be included: 4.30 p.m. For a round hour it is not necessary to include a decimal point and two zeros: prefer 4 p.m. to 4.00 p.m. In North America, Scandinavia, and elsewhere the full point is replaced by a colon: 4:30 p.m. This is often seen in British usage too. Some styles omit the punctuation in a.m. and p.m.

11.4 Roman numerals

The base numerals are I (1), V (5), X (10), L (50), C (100), D (500), and M (1,000). The principle behind their formation is that identical numbers are added (II = 2), smaller numbers after a larger one are added (VII = 7), and smaller numbers before a larger one are subtracted (IX = 9). The I, X, and C can be added up to four times:

I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X (10)

XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX, XX (20)

MCCCCVIII (1408)

If possible, avoid eliding Roman numerals. To save space in certain circumstances two consecutive numerals may be indicated by f. for ‘following’: pp. lxxxvii–lxxxviii becomes pp. lxxxvii f.

Roman numerals can be difficult to interpret and may cause design problems because of the variable number of characters needed to express them. For example, they may be best avoided in tabulated lists, such as contents pages, because the alignment of the numerals and the following matter can produce excessive white space on the page:

| I | … |

| II | … |

| III | … |

| IV | … |

| V | … |

| VI | … |

| VII | … |

| VIII | … |

| IX | … |

| X | … |

Oxford’s use of Roman numerals is described below:

| Act I of The Tempest | Book V |

| Chapters III–VIII | Volume XVI Soot–Styx |

| pp. iii–x | Hamlet, Act I, sc. ii |

11.5 Date forms

Figures are used for days and years in dates. Use cardinal numbers not ordinal numbers for dates:

| 12 August 1960 | 2 November 2003 |

Do not use the endings -st, -rd, or -th in conjunction with a figure, as in 12th August 1960, unless copying another source: dates in letters or other documents quoted verbatim must be as in the original. Where less than the full date is given, write 10 January (in notes 10 Jan.), but the 10th. If only the month is given it should be spelled out, even in notes. An incomplete reference may be given in ordinal form:

They set off on 12 August 1960 and arrived on the 18th

In British English style dates should be shown in the order day, month, year, without internal punctuation: 2 November 2003. In US style the order is month, day, year: November 2, 2003.

A named day preceding a date is separated by a comma: Tuesday, 2 November 1993; note that when this style is adopted a terminal second comma is required if the date is worked into a sentence:

On Tuesday, 2 November 1993, the day dawned frosty

There is no comma between month and year: in June 1831. Four-figure dates have no comma—2001—although longer dates do: 10,000 BC.

Abbreviated all-figure forms are not appropriate in running text, although they may be used in notes and references. The British all-figure form is 2/11/03 or 2.11.03 (or the year may be given in full). In US style the all-figure form for a date, which is always separated by slashes rather than full points, can create confusion in transatlantic communication, since 11/2/03 is 2 November to an American reader and 11 February to a British one. Note that the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 are known by the shorthand September 11 or 9/11 not only in the US but also in Britain and around the world.

The dating system promoted by the ISO is year, month, day, with the elements separated by hyphens: 2003-11-02. This style is preferred in Japan and increasingly popular in technical, computing, and financial contexts. Another alternative, common on the Continent and elsewhere, is to use (normally lower-case) Roman numerals for the months (2. xi. 03). This system serves to clarify which number is the day and which the month in all contexts—a useful expedient when translating truncated dates into British or US English.

For precise dates in astronomical work, use days (d), hours (h), minutes (m), and seconds (s) (2001 January 1d 2h 34m 4.8s) or fractions of days (2001 January 1.107). See also 14.7.2.

For abbreviations of days and months see 10.2.6.

11.6 Decades, centuries, and eras

11.6.1 Decades

References to decades may be made in either words or figures:

Write either the sixties or the 1960s, not the ’60s. Similarly, when referring to two decades use the 1970s and 1980s, even though the 1970s and ’80s transcribes how such dates may be read out loud.

When the name of a decade is used to define a social or cultural period it should be written as a word (some styles use an initial capital). The difference between labelling a decade the twenties and calling it the 1920s is that the word form connotes all the social, cultural, and political conditions unique to or significant in that decade, while the numerical form is simply the label for the time span. So, the frivolous, fun-loving flappers of the twenties, but the oyster blight of the 1920s.

11.6.2 Centuries

Depending on the editorial style of the work, refer to centuries in words or figures; Oxford style is to use words:

| the nineteenth century | the first century BC |

Centuries may be abbreviated in notes, references, and tabular matter; the abbreviation may be either c. or cent.: 14th c., 21st cent. Both spelled-out and abbreviated forms require a hyphen when used adjectivally:

an eighth-century (or 8th-c.) poem

the early seventeenth-century (or 17th-c.) dramatists

In dating medieval manuscripts, the abbreviation s. (for saeculum, pl. ss.) is often used instead: s. viii.

Centuries BC run backwards, so that the fifth century BC spanned 500–401 BC. The year 280 BC was in the third century BC.

Conventions for numbering centuries in other languages vary, though for the most part capital Roman numerals are used, with two common exceptions: French uses small capitals in roman, full capitals in italic. In either case the figures are followed by a superior e or ème to indicate the suffix: le XVIIe siècle, le XVIIème siècle. German uses Arabic numerals followed by a full point: das 18. Jahrhundert. Occasionally capital Roman numerals are used; these too must be followed by a full point.

11.6.3 Eras

The two abbreviations most commonly used for eras are BC and AD. Both are written in small capitals. The abbreviation BC (before Christ) is placed after the numerals, as in 72 BC, not BC 72; AD (anno domini, ‘in the year of our Lord’) should be placed before the numerals, as in AD 375 (not 375 AD). However, when the date is spelled out it is normal to write the third century AD rather than AD the third century.

Some writers prefer to use AD for any date before the first millennium. While this is not strictly necessary, it can be handy as a clarifying label: This was true from 37 may not instantly be recognized as referring to a year. Any contentious date, or any year span ranging on either side of the birth of Christ, should be clarified by BC or AD: this was true from 43 BC to AD 18. Conversely, a date span wholly in BC or AD technically needs no clarification, since 407–346 is manifestly different from 346–409, though it is customary to identify all BC dates explicitly.

The following eras should be indicated by the appropriate abbreviation before the year:

The following eras should be indicated by the appropriate abbreviation after the year:

For all era abbreviations other than a.Abr., use unspaced small capitals, even in italic.

11.7 Regnal years

Regnal years are marked by the successive anniversaries of a sovereign’s accession to the throne. Consequently they do not coincide with calendar years, which up to 1751 in England and America—though not in Scotland—began legally on 25 March. All Acts of Parliament before 1963 were numbered serially within each parliamentary session, which itself was described by the regnal year or years of the sovereign during which it was held. Regnal years were also used to date other official edicts, such as those of universities.

Regnal years are expressed as an abbreviated form of the monarch’s name followed by a numeral. The abbreviations of monarchs’ names in regnal-year references are as follows:

Car. or Chas. (Charles)

Hen. (Henry)

Steph. (Stephen)

Edw. (Edward)

Jac. (James)

Will. (William)

Eliz. (Elizabeth)

P. & M. (Philip and Mary)

Wm. & Mar. (William and Mary)

Geo. (George)

Ric. (Richard)

Vic. or Vict. (Victoria)

The names of John, Anne, Jane, and Mary are not abbreviated. See 13.5.1 for details of citing statutes including regnal years.

11.8 Calendars

11.8.1 Introduction

The following section offers brief guidance for those working with some less familiar calendars; fuller explanation may be found in Bonnie Blackburn and Leofranc Holford-Strevens, The Oxford Companion to the Year (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Dates in non-Western calendars should be given in the order day, month, year, with no internal punctuation: 25 Tishri AM 5757, 13 Jumada I AH 1417. Do not abbreviate months even in notes.

11.8.2 Old and New Style

The terms Old Style and New Style are applied to dates from two different historical periods. In 1582 Pope Gregory XIII decreed that, in order to correct the calendar then used—the Julian calendar—the days 5–14 October of that year should be omitted and no future centennial year (e.g. 1700, 1800, 1900) should be a leap year unless it was divisible by 400 (for example 1600, 2000). This reformed Gregorian calendar was quickly adopted in Roman Catholic countries, more slowly elsewhere: in Britain not till 1752 (when the days 3–13 September were omitted), in Russia not till 1918 (when the days 16–28 February were omitted). Dates in the Julian calendar are known as Old Style, while those in the Gregorian are New Style.

Until the middle of the eighteenth century not all states reckoned the new year from the same day: whereas France adopted 1 January from 1563, and Scotland from 1600, England counted from 25 March in official usage as late as 1751. Thus the execution of Charles I was officially dated 30 January 1648 in England, but 30 January 1649 in Scotland. Furthermore, although both Shakespeare and Cervantes died on 23 April 1616 according to their respective calendars, 23 April in Spain (and other Roman Catholic countries) was only 13 April in England, and 23 April in England was 3 May in Spain.

Confusion is caused on account of the adoption, in England, Ireland, and the American colonies, of two reforms in quick succession: the adoption of the Gregorian calendar and the change in the way the beginning of the year was dated. The year 1751 began on 1 January in Scotland and on 25 March in England, but ended throughout Great Britain and its colonies on 31 December, so that 1752 began on 1 January. So, whereas 1 January 1752 corresponded to 12 January in most Continental countries, from 14 September onwards there was no discrepancy. Many writers treat the two reforms as one, using Old Style and New Style indiscriminately for the start of the new year and the form of calendar. In the interests of clarity Old Style should be reserved for the Julian calendar and New Style for the Gregorian; the 1 January reckoning should be called ‘modern style’, that from 25 March ‘Annunciation’ or ‘Lady Day’ style.

It is customary to give dates in Old or New Style according to the system in force at the time in the country chiefly discussed. Any dates in the other style should be given in parentheses with an equals sign preceding the date and the abbreviation of the style following it: 23 August 1637 NS (= 13 August OS) in a history of England, or 13 August 1637 OS (= 23 August NS) in one of France. In either case, 13/23 August 1637 may be used for short. On the other hand, it is normal to treat the year as beginning on 1 January: modern histories of England date the execution of Charles I to 30 January 1649. When it is necessary to keep both styles in mind, it is normal to write 30 January 1648/9; otherwise the date should be given as 30 January 1648 (= modern 1649).

11.8.3 Greek calendars

In the classical period years were designated by the name of a magistrate or other office-holder, which meant nothing outside the city concerned. In the third century BC a common framework for historians was found in the Olympiad, or cycle of the Olympic Games, held in the summer every four years from 776 BC onwards. Thus 776/5 was designated the first year of the first Olympiad; 775/4 the second year; and 772/1 the first year of the second Olympiad. When modern scholars need to cite these datings, they are written Ol. 1, 1, Ol. 1, 2, and Ol. 2, 1 respectively.

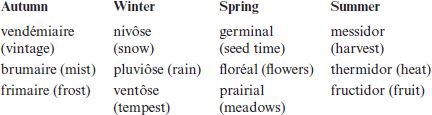

11.8.4 French Republican calendar

The Republican calendar was introduced on 5 October 1793, and was discontinued with effect from 1 January 1806. On its introduction it was antedated to begin from the foundation of the Republic (22 September 1792). The months of the new calendar were named according to their seasonal significance. Though difficult to translate, approximations are included in parentheses:

The months are not now capitalized in French, though they were at the time and may still be so in English. Years of the Republican calendar are printed in capital Roman numerals: 9 thermidor An II; 13 vendémiaire An IV; in English Year II, Year IV.

11.8.5 Jewish calendar

The Jewish year consists in principle of twelve months of alternately 30 and 29 days; in seven years out of nineteen an extra month of 30 days is inserted, and in some years either the second month is extended to 30 days or the third month shortened to 29 days. The era is reckoned from a notional time of Creation at 11.11 and 20 seconds p.m. on Sunday, 6 October 3761 BC.

11.8.6 Muslim calendar

The Muslim year consists of twelve lunar months, so that thirty-three Muslim years roughly correspond to thirty-two Christian ones. Years are counted from the first day of the year in which the Prophet made his departure, or Hegira, from Mecca to Medina, namely Friday, 16 July AD 622.