CHAPTER 13

Law and legal references

13.1 Introduction

Often the standards adopted in the legal discipline are at variance with those of other subjects. Additionally, practices common in one aspect of the law may be unfamiliar in another. However, there is no reason why the following general guidelines cannot be applied across a broad range of legal studies. Given the variety of legal citations in use, this section cannot purport to be wholly definitive, nor to resolve every stylistic point that may occur. Options are given for those aspects of citation on which there is no widespread consensus.

13.2 Typography

13.2.1 Italics

Law uses more foreign—particularly Latin—words than many other subjects. For that reason law publishers may deviate from the usage of general reference works when determining which words and phrases to italicize. Only a handful of foreign-language law terms have become so common in English that they are set as roman in general use. Some publishers use this as a basis for determining styles: the well-known ‘inter alia’ and ‘prima facie’ are in roman, for example, but de jure and stare decisis are in italic. Others prefer to set all Latin words and phrases in italic, rather than appear inconsistent to readers immersed in the subject, for whom all the terms are familiar. Regardless of which policy is followed, words to be printed in roman rather than italic include the accepted abbreviations of ratio decidendi and obiter dictum/dicta: ‘ratio’, ‘obiter’, ‘dictum’, and ‘dicta’.

Traditionally, the names of the parties in case names are cited in italics, separated by an italic or roman ‘v.’ (for ‘versus’): Smith v. Jones. The ‘v.’ may have a full point: any style is acceptable if consistently applied.

13.2.2 Abbreviations

There are four possibilities regarding the use of full points in abbreviations:

References, especially familiar ones, and common legal terms (paragraph, section), may be abbreviated in the text as well as in notes, but all other matter should be set out in full. Where a term is repeated frequently and is unwieldy when spelled out, such as ‘International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights’, then refer to it at first mention in full, with ‘(ICCPR)’ following it, and thereafter simply as ‘ICCPR’. Be careful that the abbreviations chosen do not confuse institutions with conventions (for example, use ‘ECHR’ for ‘European Convention on Human Rights’ and ‘ECtHR’ for ‘European Court of Human Rights’). Both the Court of Justice of the European Union and the European Court of Human Rights are frequently referred to as ‘the European Court’: the European Court of Human Rights should always be referred to in full, unless the text in question is specifically about human rights and there is no possibility of confusion.

In cases, use ‘Re’ rather than ‘In re’, ‘In the matter of’, etc. Abbreviate ex parte to ex p, with the letter e capitalized when it appears at the beginning of a case name but in lower case elsewhere:

R v. Acton Magistrates, ex p. McMullen

When citing a law report, generally do not include expressions such as ‘and another’ or ‘and others’ that may appear in the title, but use ‘and anor’, or ‘and ors’ in cases such as ‘Re P and ors (minors)’ to avoid the appearance of error. To avoid unnecessary repetition, shorten citations in the text following an initial use of the full name: ‘in Glebe Motors plc v Dixon-Greene’ could subsequently be shortened to ‘in the Glebe Motors case’. In criminal cases it is acceptable to abbreviate ‘in R v Caldwell’ to ‘in Caldwell’. Where a principle is known by the case from which it emerged, the name may no longer be italicized: for example, ‘the Wednesbury principle’.

Law notes tend to be fairly lengthy, so anything that can be abbreviated should be. Thus ‘HL’, ‘CA’, etc. are perfectly permissible, as are ‘s’, ‘Art’, ‘Reg’, ‘Dir’, %, all figures, ‘High Ct’, ‘Sup Ct’, ‘PC’, ‘Fam Div’, etc., even in narrative notes.

13.2.3 Capitalization

Capitalize ‘Act’, even in a non-specific reference; ‘bill’ is lower case except in the name of a specific bill. Unless it is beginning a sentence, ‘section’ always has a lower-case initial. ‘Article’ should be capitalized when it refers to supranational legislation (conventions, treaties, etc.) and lower case when it refers to national legislation.

‘Court’ with a capital should be used only when referring to international courts such as the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and the International Court of Justice, or for relating information specific to a single court. For instance, in a book about the Court of Appeal, Criminal Division, that court may be referred to as ‘the Court’ throughout. It is a common shorthand convention in US law to refer to the Supreme Court as ‘the Court’ and to a lesser court as ‘the court’.

A capital may also be used in transcripts where a court is talking about itself, but not necessarily where it refers to itself in a different composition. Thus members of a Court of Appeal would refer to ‘a judgment of the Court’ when citing a previous judgment by themselves, but to ‘that court’ when referring to a Court of Appeal composed of others. Where, however, the reference is to a court in general, the c should always be lower case. For spelling of ‘judgment’ in legal contexts, see 13.8.

The word ‘judge’ should always begin with a lower-case letter, unless it is referring to a specific person’s title or the author has contrasted the Single Judge with the Full Court (as in criminal appeals and judicial review proceedings), where they both have specific parts to play and almost constitute separate courts in themselves.

13.3 References

The names of books and non-law journals and reports should be in italic, following the standard format (see Chapter 8). Abbreviated references to reports and reviews should be in roman—in text, references, and lists of abbreviations. Full names of law journals and reports are in roman in Oxford style (e.g. Solicitors Journal), the reference following the date. Some publishers style the full name in italics but even here the abbreviated form is always roman: All England Reports but All ER.

References to journals, reports, or reviews should be cited with the date and volume number first, followed by the abbreviation of the report or review name, and then—without a comma in between—the page number. Where a specific page within an article is referred to, the initial page number should be followed by a comma plus the specific page number, or no comma and ‘at’ followed by the specific page number (choose one style or the other and use it consistently).

P Birks, ‘The English Recognition of Unjust Enrichment’ [1991] LMCLQ 473, 490–2

SC Manon, ‘Rights of Water Abstraction in the Common Law’ (1965) 83 LQR 47 at 49–51

Some legal writers cite others’ works without a place of publication, or without first names or initials, for example ‘Smith & Hogan Criminal Law (13th edn, 2011)’. This is an established convention in at least parts of the discipline, the expectation being that the work will be read by those who are already immersed in the relevant texts. However, editors should not impose it, and if the expected readership is more general or more elementary (as in an undergraduate or introductory text), full references must be given.

Certain textbooks have been accorded such eminence that in references the name of the original author appears in italics as part of the title, for example Chitty on Contracts and Dicey and Morris on Conflict of Laws. In full references it is not necessary to give the name of the current editor, although the edition number and the date of that edition must be stated.

Abbreviate only titles of well-known books, journals, or reports (for example Smith & Hogan, the NLJ); all others should appear in full. Variations exist in the way that many periodicals are abbreviated or punctuated. Providing authors are consistent, such variations are acceptable; in works for non-specialists, readers may benefit from expanded versions of very terse abbreviations.

Setting all abbreviated titles in roman does leave some pitfalls, of which one must be wary: ‘CMLR’, for instance, refers to Common Market Law Reports (which publishes only reports and never articles), while ‘CMLRev’ refers to Common Market Law Review. Unfortunately, where authors cite the latter as the former the only indication of the error is that the reference is to an article.

If a book, journal, report, or series is referred to very frequently in a particular work, certain common abbreviations (such as ‘Crim’, ‘Eur’, ‘Intl’, ‘J’, ‘L’, ‘Q’, ‘R’, ‘Rev’, ‘U’, ‘Ybk’) may be used; give them in full at their first occurrence but abbreviated thereafter, and include in the List of Abbreviations.

13.4 Citing cases

13.4.1 General principles

Where a specific page within a report is referred to, the initial page number should be followed by a comma plus the specific page number, or no comma and ‘at’ followed by the specific page number: the decision is a matter of personal choice but should be applied consistently throughout a particular work:

Ridge v Baldwin [1964] AC 40, 78–9

or

… [1964] AC 40 at 78–9

In reports a date is in square brackets if it is essential for finding the report, and in parentheses where there are cumulative volume numbers, the date merely illustrating when a case was included in the reports:

R v Lambert [2001] 2 WLR 211 (QBD)

Badische v Soda-Fabrics (1897) 14 RPC 919 (HL)

No brackets are used in cases from the Scottish Series of Session Cases from 1907 onwards, and Justiciary Cases from 1917 onwards, but instead the case name is followed by a comma:

Hughes v Stewart, 1907 SC 791

Corcoran v HM Advocate, 1932 JC 42

It is usual to refer to Justiciary Cases (criminal cases before the High Court of Justiciary) simply by the name of the panel (or accused).

In US, South African, and some Canadian cases the date falls at the end of the reference:

Michael v Johnson, 426 US 346 (1976)

Quote extracts from cases exactly. Do not amend to improve the sense, and clearly indicate if you correct obvious errors. Omitted text should be indicated by ellipses.

Neutral citations

Since 2001 most UK cases have been given a neutral citation, which is the official number attributed to the judgment by the court. Give the neutral citation first, followed by a citation of the best report (see 13.4.3):

R v G [2003] UKHL 50, [2004] 1 AC 1034

To cite a specific paragraph of a judgment, enclose the paragraph number in square brackets:

R v G [2003] UKHL 50 at [13]

13.4.2 Unreported

Cite a newspaper report if there is no other published report. The reference should not be abbreviated or italicized:

Powick v Malvern Wells Water Co., The Times, 28 September 1993

When a case has not (yet) been reported and there is no neutral citation, cite just the name of the court and the date of the judgment. The word ‘unreported’ should not be used:

R v Marianishi, ex p London Borough of Camden (CA, 13 April 1965)

Unreported EU cases are handled differently (see 13.4.4 below).

13.4.3 Courts of decision

Unless the case has a neutral citation, was heard in the High Court or was reported in a series that covers the decisions of only one court, the court of decision should be indicated by initials at the end of the reference:

Blay v Pollard [1930] 1 AC 628, HL

Bowman v Fussy [1978] RPC 545, HL

Re Bourne [1978] 2 Ch 43

References to unreported cases, however, should be made in parentheses to the court of decision first (even if it is an inferior court), followed by the date. Reference is not normally made to the deciding judge (for example ‘per Ferris J’), except when wishing to specify him or her when quoting from a Court of Appeal or House of Lords decision.

Where a case has been included in a report long after it was heard, both the report and hearing dates may be included in the citation so the reader knows there has been no error:

Smith v Jones [2001] (1948) 2 All ER 431

A single ‘best’ reference should be given for each case cited. For UK cases, the reference should be to the official Law Reports; if the case has not been reported there, the Weekly Law Reports (WLR) are preferred, and failing that the All England Reports (All ER). In certain specialist areas it will be necessary to refer to the relevant specialist series, for example Family Law Reports and Industrial Cases Reports.

13.4.4 European Union

Where it is available, cite a reference to the official reports of the EU, the European Court Reports (ECR), in preference to other reports. If an ECR reference is not available, the second-best reference will usually be to the Common Market Law Reports (CMLR). However, where a case is reported by the (UK) official Law Reports, the WLR, or the All ER, that may be cited in preference to CMLR, particularly if readers may not have ready access to CMLR. If the case is not yet reported it should be cited with a reference to the relevant notice in the Official Journal.

The case number should always be given before the name of a case in the Court of Justice of the European Union (which consists of the Court of Justice, the General Court (formerly the Court of First Instance), and the Civil Service Tribunal):

Case C-118/07 Commission of the European Communities v Finland [2009] ECR I-10889

Treat Commission Decisions—but not Council Decisions—as cases.

Judgments of the courts are uniformly translated into English from French, sometimes inexactly. If the meanings of such judgments are not clear, refer to the original French for clarification.

13.4.5 European Human Rights

For decisions of the European Court of Human Rights cite official reports or the European Human Rights Reports (EHRR), providing one in preference to the other throughout. Until 1 November 1998 the official reports were known as Series A and numbered consecutively. The official reports were then renamed as Reports of Judgments and Decisions and they are cited as ECHR. The EHRR series is consecutively numbered, but from 2001 case numbers replaced page numbers:

Young, James and Webster v UK (App no 7601/76) (1982) 4 EHRR 38

Plattform ‘Artze für das Leben’ v Austria (App no 10126/82) (1988) Series A no 139

Osman v UK (App no 23452/94) ECHR 1998-VIII 3124

Decisions and reports of the European Commission of Human Rights (now defunct) should cite the relevant application number, a reference to the Decisions and Reports of the Commission series (or earlier to the Yearbook of the ECHR), and—if available—a reference to the EHRR:

Zamir v UK (App no 9174/80), (1985) 40 DR 42

13.4.6 Other cases

The citation of laws in other jurisdictions is too big a subject to cover in any great detail here. Authors and editors unsure of the relevant conventions should consult The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (19th edn, 2010). This is a useful guide to citing legal sources from a wide range of jurisdictions.

13.5 Legislation

13.5.1 UK legislation

A statute’s title should always be in roman, even where a foreign statute is in italics in the original. Older statutes, without a short title, will require the appropriate regnal year (see 11.7) and chapter number. Use Arabic numerals for chapter numbers in Public (General) and Private Acts:

3 & 4 Geo V, c 12, ss 18, 19

Use lower-case Roman numerals in Public (Local) Acts:

3 & 4 Geo V, c xii, ss 18, 19

Scots Acts before the Union of 1707 are cited by year and chapter: 1532, c 40. All Acts passed after 1962 are cited by the calendar year and chapter number of the Act; commas before the date were abolished retroactively in 1963. There is no need for the word ‘of’—except perhaps when discussing a number of Acts with the same title (for example, to distinguish the Criminal Appeals Act of 1907 from that of 1904). Provided the meaning is clear, it is permissible even in text to refer to ‘the 1904 Act’.

Some UK statutes are almost invariably abbreviated, for example PACE (Police and Criminal Evidence Act) and MCAs (Matrimonial Causes Acts). Where such abbreviations will be familiar to readers they may be used, even in text, although it is best to spell a statute out at first mention with the abbreviation in parentheses before relying thereafter simply on the abbreviation. Use an abbreviation where one particular statute is referred to many times throughout the text.

Except at the start of a sentence or when the reference is non-specific, use the following abbreviations: ‘s’, ‘ss’, ‘Pt’, ‘Sch’. For example, paragraph (k) of subsection (4) of section 14 of the Lunacy Act 1934 would be expressed as ‘Lunacy Act 1934, s 14(4)(k)’. There is no space between the bracketed items. In general, prefer ‘section 14(4)’ to ‘subsection (4)’ or ‘paragraph (k)’; if the latter are used, however, they can be abbreviated to ‘subs (3)’ or ‘para (k)’ in notes.

Statutory instruments should be referred to by their name, date, and serial number:

Local Authority Precepts Order 1897, SR & O 1897/208

Community Charge Support Grant (Abolition) Order 1987, SI 1987/466

No reference should be made to any subsidiary numbering system in the case of Scots instruments, those of a local nature, or those making commencement provisions.

Quote extracts from statutes exactly. Do not amend to improve the sense, and clearly indicate if you correct obvious errors. Omitted text should be indicated by ellipses.

13.5.2 European Union legislation

For primary legislation, include both the formal and informal names in the first reference to a particular treaty:

EC Treaty (Treaty of Rome, as amended), Art 3b

Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty), Art G5c

Cite articles of the treaties without reference to the titles, chapters, or subsections. As part of a reference, abbreviate ‘Article’ to ‘Art’, in roman. Cite protocols to the treaties by their names, preceded by the names of the treaties to which they are appended:

Act of Accession 1985 (Spain and Portugal), Protocol 34

EC Treaty, Protocol on the Statute of the Court of Justice

References to secondary legislation (decisions, directives, opinions, recommendations, and regulations) should be to the texts in the Official Journal of the European Union. The title of the legislation precedes the reference to the source:

Council Directive (EC) 97/1 on banking practice [1997] OJ L234/3

Council Regulation (EEC) 1017/68 applying rules of competition to transport [1968] OJ Spec Ed 302

While it is always important to state the subject matter of EU secondary legislation, the long official title may be abbreviated provided that the meaning is clear. For example, the full title may be abbreviated to

Commission Notice on agreements of minor importance which do not fall under Article 85(1) of the Treaty establishing the EEC [1986] OJ C231/2, as amended [1994] OJ C368/20

Commission Notice on agreements of minor importance [1986] OJ C231/2, as amended [1994] OJ C368/20

13.6 International treaties, conventions, etc.

Apart from EU treaties, where the short name usually suffices (see above), set out the full name of the treaty or convention with the following information in parentheses:

For example, a reference to the Refugee Convention should be expressed as follows:

Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (adopted 28 July 1951, entered into force 22 April 1954) 189 UNTS 137 (Refugee Convention)

A short title will suffice for subsequent references in the same chapter.

References to the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) and US Restatements should be set in roman, for example ‘UCC ss 2–203’.

13.7 Other materials

13.7.1 Reports of Parliamentary select committees

Refer to such papers by name and number:

Defence Select Committee, ‘Iraq: An Initial Assessment of Post-Conflict Operations’ HC (2004–05) 65-I

13.7.2 Law Commission

Cite Law Commission reports by name and Commission number, with the year of publication and any Command Paper number:

Law Commission, Intoxication and Criminal Liability (Law Com No 314, Cm 7526, 2009) para 1.15

13.7.3 Hansard

Hansard (not italic) is the daily and weekly verbatim record of debates in the British Parliament (its formal name being The Official Report of Parliamentary Debates). There have been five series of Hansard: first, 1803–20 (41 vols); second, 1820–30 (25 vols); third, 1830–91 (356 vols); fourth, 1892–1908 (199 vols); fifth, 1909– . It was only from 1909 that Hansard became a strictly verbatim report; prior to that time the reports’ precision and fullness varied considerably, particularly before the third series.

Since 1909 reports from the House of Lords and the House of Commons have been bound separately, rather than within the same volume. References up to and including 1908 are ‘Parl. Deb.’ Hansard is numbered by column rather than page. Full references are made up of HC or HL, volume number, column number, and date (in parentheses):

Hansard, HC vol 357, cols 234–45 (13 April 1965)

For pre-1909 citations, use the following form:

Parl. Deb. (series 4) vol. 24, col. 234 (24 March 1895)

13.7.4 Command Papers

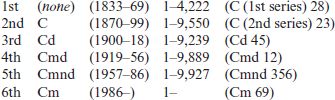

In references, the abbreviations given before the numbers of Command Papers vary according to the time period into which the paper falls. Consequently they should not be made uniform or changed unless they are clearly incorrect. The series, abbreviations, years, and number extents are as follows, with an example for each:

The references themselves are set in parentheses:

Secretary of State for Health, ‘Government Response to the House of Commons Health Committee Report on the Provision of Allergy Services’ (Cm 6433, 2005)

13.8 Judges’ designations and judgments

In text it is correct either to spell out the judge’s title (Mr Justice Kennedy) or to abbreviate it (Kennedy J). It is best to follow the author’s preference, providing it is consistently applied in similar contexts. It is a matter of house style whether or not the abbreviation takes a full point. The following table shows various titles and their abbreviated forms, where they exist:

| Mr Justice | J |

| Lord Justice | LJ |

| Lords Justice | LJJ |

| Lord Chief Justice Parker | Parker LCJ, Lord Parker CJ |

| The Master of the Rolls, Sir F. R. Evershed | Evershed MR |

| His Honour Judge (County Court) | HH Judge |

| Attorney General | Att. Gen. |

| Solicitor General | Sol. Gen. |

| Lord … , Lord Chancellor … | LC |

| Baron (historical, but still quoted) | B |

| Chief Baron Blackwood | Blackwood CB |

| The President (Family Division) | Sir Stephen Brown, P |

| Advocate General (of the CJEU) | Slynn AG |

| Judge (of the CJEU) | no abbreviation |

Law Lords are the Justices of the Supreme Court; their names are not abbreviated. Do not confuse them with Lords Justice. ‘Their Lordships’ can be a reference to either rank. There is in legal terms no such rank as ‘member of the Privy Council’: the Judicial Committee of Privy Council is staffed by members of the Supreme Court.

‘Judgment’ spelled with only one e is correct in the legal sense of a judge’s or court’s formal ruling, as distinct from a moral or practical deduction. A judge’s judgment is always spelled thus, as judges cannot (in their official capacity) express a personal judgement separate from their role. In US style ‘judgment’ is the spelling used in all contexts.