CHAPTER 8

Work titles in text

8.1 General principles

The text of one work often contains references to others. They may be discussed at length or mentioned fleetingly in passing, with extended bibliographic information or none at all. Work titles mentioned in the text should be styled according to consistent conventions, which will normally match those used in the notes or bibliography, if these are present. It should be noted that newspapers and magazines often follow their own style, which differs from other non-fiction works.

‘Work titles’ is a category of convenience, the boundaries of which may be indistinct. The works considered here are often in written form, but also include broadcast works, film, digital works (including games, apps, and podcasts), musical works, and works of art. The definition of a title is by no means unproblematic, especially outside the area of printed works, not least because the distinction between a formal title and a description is to some extent a matter of convention and arbitrary decision.

8.2 Titles of written works

8.2.1 Introduction

The typography and capitalization of the title of a written work depend on whether or not it was published and on the form in which it was published. Publication is not synonymous with printing: works were widely disseminated before the invention of printing and, in the modern era, many ebooks do not exist in hard copy form. Conversely, material that is printed is not necessarily published.

For capitalization of titles see 8.2.3; for use of ‘the’ see 8.2.7.

8.2.2 Typography

Free-standing publications

The title of a free-standing publication is set in italic type. This category comprises works whose identity does not depend on their being part of a larger whole. Such works may be substantial but they may also be short and ephemeral, if published in their own right. They thus include not only books of various kinds (for example novels, monographs, collections of essays, editions of texts, or separately published plays or poems) but also periodicals, pamphlets, titled broadsheets, and published sale and exhibition catalogues:

For Whom the Bell Tolls

Gone with the Wind

The Importance of Being Earnest: A Trivial Comedy for Serious People

Sylvie and Bruno

A Tale of Two Cities

The Merchant of Venice

the third canto of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage

The Economist

Farmer and Stockbreeder

a pamphlet, The Douglas System of Economics, which found a wide sale

Essay toward Settlement, a broadsheet petition published by 19 September 1659

The names of albums, CDs, and collections of songs are given in italic, whereas those of individual songs are in roman with quotation marks: see 8.6.

Digital resources (ebooks, apps, video games, podcasts etc.) should also be in italic: see 8.5.1.

Branded board and card games (Scrabble, Magic: The Gathering) are capitalized and usually roman with no quotation marks; generic names (chess, bridge) are roman lower case.

The names of sacred texts (see 8.3) are set in roman; the titles of ancient epic poems are usually set in italic (the Iliad, Ovid’s Metamorphoses). The Mahābhārata is both a sacred text and an epic poem—roman can be used when reference is made in general terms and italic for a particular published text.

The titles of works published in manuscript before the advent of printing are italicized. They may be consistently styled like those published in print (it is pointless to ask whether, for example, a medieval work that survives in a unique copy was widely distributed, and irrelevant to inquire whether it has been printed in a modern edition):

the document we now call Rectitudines singularum personarum, which originated perhaps in the mid-tenth century

Items within publications

The title of an item within a publication is set in roman type within single quotation marks. This includes titles of short stories, chapters or essays within books, individual poems in collections, articles in periodicals, newspaper columns, individual texts within larger editions, sections within websites, and individual blog articles (see 8.5.1):

‘The Monkey’s Paw’

‘The Old Vicarage, Grantchester’

‘Sailing to Byzantium’

‘Tam o’ Shanter’

‘Three Lectures on Memory’, published in his first volume of essays, Knowledge and Certainty

she began writing a weekly column, ‘Marginal Comments’, for The Spectator

today’s recommendation is ‘Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year’ from OUPblog

There is room for flexibility here. For example, the titles of longer poems—such as Byron’s Don Juan or Tennyson’s In Memoriam—are usually italicized, as are individual Canterbury tales:

the first true editor of the Canterbury Tales

the aristocratic noble love of The Knight’s Tale gives way to the more earthy passions of The Miller’s Tale and The Reeve’s Tale

Series titles

A series of books is not itself a work, and its title is not given the same styling as its component works. The overall title of a series is not normally needed when a book is mentioned, but if given should be set in roman type with the first and principal words capitalized:

the Rough Guides

Studies in Biblical Theology

The Social Structure of Medieval East Anglia, volume 9 of Oxford Studies in Social and Legal History

Descriptions of an edition should not be considered series titles and should not be capitalized, but a publisher’s named edition of the works of a single author may be treated as a series title:

the variorum edition of her Complete Poetry

Dent published the Temple Edition of the Waverley Novels in forty-eight volumes

Titles of series of works of fiction may either be italicized like book titles or set in quotation marks, but loose descriptions of fictional series should not be treated as titles:

| The Forsyte Saga | the ‘His Dark Materials’ trilogy, or the His Dark Materials trilogy |

| the Barsetshire novels |

Style the titles of series of works of art like those of series of books (with the exception of series of published prints, which are given italic work titles):

a series of paintings entitled Guyana Myths

a series of prints, in issues of six, Studies from Nature of British Character

Unpublished works

The title of an unpublished work is set in roman type within single quotation marks. This category includes titles of such unpublished works as dissertations and conference papers, and longer unpublished monographs. (However, don’t assume that all doctoral dissertations, for example, remain unpublished: in some universities, publication accompanies the awarding of the degree, or dissertations may be available online only.) The same styling is applied to internal reports, provisional titles used for works before their publication, and titles of works intended for publication but never published, or planned but never written:

his undergraduate dissertation, ‘Leeds as a Regional Capital’

‘Work in Progress’ (published as Finnegans Wake)

Forster later planned to publish an ‘Essay on Punctuation’

an unpublished short play, ‘The Blue Lizard’

This treatment is accorded to unpublished works that are essentially literary compositions. Do not style descriptions of archival items as work titles. References to such material as unpublished personal documents, including diaries and letters, and legal, estate, and administrative records should be given in descriptive form with minimal capitalization:

Dyve’s letter-book is valuable evidence

the diary of Robert Hooke for 3 April

the cartulary of the hospital of St John

the great register of Bury Abbey

the stewards’ accounts in the bursars’ book for 1504–5

Capitalized names are sometimes given to certain manuscripts. It is best to follow the author’s usage (provided it is consistent on its own terms).

the marginal illustrations in the Luttrell Psalter

poems contained in the Book of Taliesin (a thirteenth-century manuscript then preserved at Peniarth)

8.2.3 Capitalization

The capitalization of work titles is a matter for editorial convention; there is no need to follow the style of title pages (many of which present titles in full capitals).

The initial word of a title is always capitalized. The traditional style is to give maximal capitalization to the titles of works published in English, capitalizing the first letter of the first word and of all other important words (for works in other languages see Chapter 12 and 8.8 below). Nouns, adjectives (other than possessives), and verbs are usually given capitals; pronouns and adverbs may or may not be capitalized; articles, conjunctions, and prepositions are usually left uncapitalized. Exactly which words should be capitalized in a particular title is a matter for individual judgement, which may take account of the sense, emphasis, structure, and length of the title. Thus a short title may look best with capitals on words that might be left lower case in a longer title:

An Actor and his Time

All About Eve

Six Men Out of the Ordinary

Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There

What a Carve Up!

Will you Love me Always?

The first word of a subtitle is traditionally capitalized, whatever its part of speech (this is the Oxford style):

Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered

Film Theory: An Introduction

Alternatively, full capitalization may be applied to the main title while the subtitle has simply the capitalization of normal prose:

Rebirth, Reform and Resilience: universities in transition 1300–1700

In titles containing a hyphenated compound capitalize all parts (Through the Looking-Glass, A Behind-the-Scenes Account of the War in Cuba).

It is possible to give minimal capitalization to very long titles (usually from older sources) while applying full capitalization to most titles:

Comfort for an afflicted conscience, wherein is contained both consolation and instruction for the sicke, against the fearfull apprehension of their sinnes, of death and the devill, of the curse of the law, and of the anger and just judgement of God

And it is usual to apply minimal capitalization to the titles of works, most especially poems or traditional songs, that are in fact their opening words:

‘Wish me luck as you wave me goodbye’

If the traditional style is to capitalize the principal words within a work title, a more modern practice—in line with a general tendency to eliminate redundant capitalization—is to capitalize the first word of a title and then to apply the capitalization of normal prose. This style of minimal capitalization, which has long been standard in bibliography, has been adopted more quickly in academic and technical publishing than in general contexts. Even in academic contexts it is applied more frequently to items in roman (such as the titles of articles) than it is to italic titles, and maximal capitalization may be retained for the titles of periodicals after it has been abandoned for the titles of books:

Sheep, their breeds, management and diseases

When champagne became French: wine and the making of a national identity

‘Inequality among world citizens’ in the American Economic Review

8.2.4 Spelling

The original spelling of a title in any language should generally be preserved. US spellings should not be replaced by British ones, or vice versa. However, as with direct quotations from text (see 9.3.1), a limited degree of editorial standardization may be acceptable where the exact original orthography is of no particular relevance. Thus in the titles of early modern works:

However, before implementing any of these changes, it is important to consult with the author, and to accede to their wishes if they prefer the original forms to be reproduced.

8.2.5 Punctuation

The original punctuation of work titles should generally be retained. However, some punctuation may be inserted to articulate a title in a way that is achieved on a title page by means of line breaks. In addition, title page forms may be made to run more smoothly by amending archaic semicolons and colons to commas; similarly, full points within a title may be changed to commas, semicolons, or colons:

The Great Arch

English State Formation as Cultural Revolution

on a title page may be rendered in text as

The Great Arch: English State Formation as Cultural Revolution

and

The mathematicall divine; shewing the present miseries of Germany, England and Ireland: being the effects portended by the last comet

may be rendered as

The mathematicall divine, shewing the present miseries of Germany, England and Ireland, being the effects portended by the last comet

Similarly,

A treatise of the bulk and selvedge of the world. Wherein the greatness, littleness, and lastingness of bodies are freely handled

may be rendered as

A treatise of the bulk and selvedge of the world, wherein the greatness, littleness, and lastingness of bodies are freely handled

Again, particularly with archaic titles, it is important to explain your proposed practice to the author.

Two other changes should be made systematically:

The Construction of Nationhood: Ethnicity, Religion and Nationalism

Parkinson’s law, or, The pursuit of progress

Senarius, sive, De legibus et licencia veterum poetarum

8.2.6 Truncation

A long title may be silently truncated, with no closing ellipsis, provided the given part is grammatically and logically complete (use a trailing ellipsis if the shortened title is grammatically or logically incomplete). Do not insert the abbreviation etc. or a variant to shorten a title (but retain it if it is printed in the original). Use an ellipsis to indicate the omission of material from the middle of a title.

Opening definite or indefinite articles may be omitted from a title to make the surrounding text read more easily. More severely shortened forms are acceptable if they are accurately extracted from the full title and allow the work to be identified; this is particularly helpful if a work is mentioned frequently and a full title given at its first occurrence.

8.2.7 Use of the

It is a common convention in referring to periodicals to include an initial capitalized and italicized The in titles which consist only of the definite article and one other word, but to exclude the definite article from longer titles. Even when this convention is adopted, the definite article must be omitted from constructions where the article does not properly modify the title (see also 8.9):

The Economist

the New Yorker

he wrote for The Times and the Sunday Times

he was the Times correspondent in Beirut

in the next day’s Times

In the name of the Bible, other sacred texts, and ancient epic poems the definite article is lower case roman, and may be dropped if syntactically expedient:

he spent tuppence on a secondhand Iliad, and was dazzled

8.2.8 Titles within titles

When the title of one work includes that of another this should be indicated with a minimum of intervention in the styling of the main title. The subsidiary title is sometimes placed within single quotation marks:

The History of ‘The Times’

Or, if the main title is italic, the subsidiary title may be set in reverse (roman) font:

Hardy’s Tragic Genius and Tess of the D’Urbervilles

Of course, whichever system is used, practice should be consistent throughout the work.

Underlining text to distinguish it is not recommended: see 7.6.

When one Latin title is incorporated in another the subsidiary title will be fully integrated grammatically into the main title, and there should be neither additional capitalization nor quotation marks:

In quartum librum meteorologicorum Aristotelis commentaria

8.2.9 Italics in titles

Within italic titles containing a reference that would itself be italic in open text (for example ships’ names), do not revert to roman in Oxford style (see 7.1.2):

The Voyage of the Meteor (not The Voyage of the Meteor)

8.2.10 Editorial insertions in titles

See 4.12.2 for a discussion of square brackets. Use square-bracketed insertions in titles very sparingly. The editorial sic should be used only if it removes a real doubt; sic is always italic, while the brackets adopt the surrounding typography:

his Collection of [Latin] nouns and verbs … together with an English syntax

one of them, ‘A borgens [bargain’s] a borgen’, setting a text written in a west-country dialect

The seven cartons [sic] of Raphael Urbino

8.2.11 Bibliographic information and locations

A work mentioned in text may or may not be given a full citation in a note; in either case bibliographic detail additional to its title may be included in the text. Broadly speaking, the elements that are given in the text should be styled according to the conventions that govern citations in the notes or bibliography, but some minor variation may be appropriate (an author’s full forename, for example, may be used rather than initials). Dates of publication are sometimes useful in text, and may be given in open text or in parentheses. Do not include place of publication routinely, but only if relevant to the discussion. Likewise STC (short-title catalogue) numbers may be given in specialist contexts or if helpful in the identification of a rare early work.

Bibliographic abbreviations and contractions used in the notes (e.g. edn, vol., bk, pt, ch.) are generally acceptable in parenthetical citations in text but should be given in full in open text (edition, volume, book, part, chapter). Do not capitalize words representing divisions within works (chapter, canto, section, and so on). Abbreviations used for libraries or archival repositories in notes may be retained in parenthetical citations but should be extended to full forms in open text.

Locations within works can be described in a variety of ways in open text (‘in the third chapter of the second book’; ‘in chapter 3 of book 2’; ‘in book 2, chapter 3’). Parenthetical references may employ the more abbreviated styles used in notes. In some contexts, for example where a text is discussed at length, short citations (for example 2.3.17 to represent book 2, chapter 3, line 17) may be acceptable even in open text. In such forms the numbers should be consistently either closed up to the preceding points or spaced off from them. The text should follow the conventions of the notes as to the use of Arabic or Roman numerals for the components of locations, for example acts, scenes, and lines of plays, or the divisions of classical or medieval texts. In the absence of parallel citations in the notes it is best to use Arabic numerals for all elements.

8.3 Sacred texts

8.3.1 The Bible

General considerations

It is the normal convention to set the title of the Bible and its constituent books in roman rather than italic type, with initial capitals. Terms for parts or versions of the Bible are usually styled in the same way (the Old Testament, the Pentateuch, the Authorized Version). Specific modern editions of the Bible (for example the New English Bible) should be given italic titles. Terms such as scripture or gospel should not be capitalized when used generically, but may be either upper or lower case when applied to a particular book of the Bible. It is not necessary to capitalize the adjective biblical, or the word bibles used of multiple copies of the Bible:

| the Acts of the Apostles | the Gospel of St Luke |

| a commentary on one of the gospels |

Formerly, biblical references to chapters and verses used lower-case Roman numerals for chapter, followed by a full point, space, and verse number in Arabic (ii. 34). Modern practice is to use Arabic numerals for both, separated by a colon and no space (Luke 2:34). Fuller forms (the second epistle of Paul to the Corinthians) are generally more appropriate to open text, and more or less abbreviated citations (2 Cor. or 2 Corinthians) to notes and parenthetical references in text, but the degree of abbreviation acceptable in running text will vary with context.

Versions of the Bible

The Bible traditionally used in Anglican worship, called the Authorized Version (AV), is an English translation of the Bible made in 1611. The Vulgate, prepared mainly by St Jerome in the late fourth century, was the standard Latin version of both the Old Testament (OT) and New Testament (NT). Two modern English versions are the English Standard Version (ESV ), an update of the 1971 Revised Standard Version, most recently revised in 2011, and the New International Version (NIV ), first published in 1973–8, and revised in 1985 and 2011. The Roman Catholic Bible was translated from the Latin Vulgate and revised in 1592 (NT) and 1609 (OT); the New Jerusalem Bible is a modern English translation (1985). Many versions are available in digital format.

The Septuagint (LXX) is the standard Greek version of the Old Testament, originally made by the Jews of Alexandria but now used (in Greek or in translation) by the Orthodox Churches. Neither Septuagint nor Vulgate recognizes the distinction between ‘Old Testament’ and ‘Apocrypha’ made by Protestants.

Books of the Bible

Names of books of the Bible are conventionally abbreviated as follows:

| Old Testament | |

| Genesis | Gen. |

| Exodus | Exod. |

| Leviticus | Lev. |

| Numbers | Num. |

| Deuteronomy | Deut. |

| Joshua | Josh. |

| Judges | Judg. |

| Ruth | Ruth |

| 1 Samuel | 1 Sam. |

| 2 Samuel | 2 Sam. |

| 1 Kings | 1 Kgs |

| 2 Kings | 2 Kgs |

| 1 Chronicles | 1 Chr. |

| 2 Chronicles | 2 Chr. |

| Ezra | Ezra |

| Nehemiah | Neh. |

| Esther | Esther |

| Job | Job |

| Psalms | Ps. (pl. Pss.) |

| Proverbs | Prov. |

| Ecclesiastes | Eccles. |

| Song of Songs (or Song of Solomon) | S. of S. |

| Isaiah | Isa. |

| Jeremiah | Jer. |

| Lamentations | Lam. |

| Ezekiel | Ezek. |

| Daniel | Dan. |

| Hosea | Hos. |

| Joel | Joel |

| Amos | Amos |

| Obadiah | Obad. |

| Jonah | Jonah |

| Micah | Mic. |

| Nahum | Nahum |

| Habakkuk | Hab. |

| Zephaniah | Zeph. |

| Haggai | Hag. |

| Zechariah | Zech. |

| Malachi | Mal. |

The first five books are collectively known as the Pentateuch (Five Volumes), or the books of Moses. Joshua to Esther are the Historical books; Job and Psalms are the Didactic books. The remainder of the Old Testament contains the Prophetical books. The major prophets are Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel; the minor prophets are Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi.

| New Testament | |

| Matthew | Matt. |

| Mark | Mark |

| Luke | Luke |

| John | John |

| Acts of the Apostles | Acts |

| Romans | Rom. |

| 1 Corinthians | 1 Cor. |

| 2 Corinthians | 2 Cor. |

| Galatians | Gal. |

| Ephesians | Eph. |

| Philippians | Phil. |

| Colossians | Col. |

| 1 Thessalonians | 1 Thess. |

| 2 Thessalonians | 2 Thess. |

| 1 Timothy | 1 Tim. |

| 2 Timothy | 2 Tim. |

| Titus | Titus |

| Philemon | Philem. |

| Hebrews | Heb. |

| James | Jas. |

| 1 Peter | 1 Pet. |

| 2 Peter | 2 Pet. |

| 1 John | 1 John |

| 2 John | 2 John |

| 3 John | 3 John |

| Jude | Jude |

| Revelation | Rev. |

| Apocrypha | |

| 1 Esdras | 1 Esdras |

| 2 Esdras | 2 Esdras |

| Tobit | Tobit |

| Judith | Judith |

| Rest of Esther | Rest of Esth. |

| Wisdom | Wisd. |

| Ecclesiasticus | Ecclus. |

| Baruch | Baruch |

| Song of the Three Children | S. of III Ch. |

| Susanna | Sus. |

| Bel and the Dragon | Bel & Dr. |

| Prayer of Manasses | Pr. of Man. |

| 1 Maccabees | 1 Macc. |

| 2 Maccabees | 2 Macc. |

8.3.2 Other sacred texts

As with the Bible, the names of Jewish and Islamic scriptures, and of other non-Christian sacred texts, are cited in roman rather than italic.

In references to the texts of Judaism and Islam, as with the Bible, there are alternative conventions for naming, abbreviating, and numbering the various elements. The forms adopted will depend on the nature of the work and on authorial and editorial preference.

Jewish scriptures

The Hebrew Bible contains the same books as the Old Testament, but in a different arrangement. The Torah or Law has Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy; Prophets has Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, the Twelve; Writings or Hagiographa has Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles. Although nowadays divided as in Christian bibles, Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles were (and still may be) each traditionally counted as one book; similarly Ezra-Nehemiah.

The Talmud is the body of Jewish civil and ceremonial law and legend, comprising the Mishnah and the Gemara. The Talmud exists in two versions: the Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud. In most non-specialist works only the former is cited.

Islamic scriptures

The Islamic sacred book is the Koran, or Qu’ran/Quran. The Koran is divided into 114 unequal units called ‘suras’ or ‘surahs’; each sura is divided into verses. Every sura is known by an Arabic name; this is sometimes reproduced in English, sometimes translated, for example ‘the Cave’ for the eighteenth. The more normal form of reference is by number, especially if the verse follows: ‘Sura 18, v. 45’, or simply ‘18. 45’. References to suras have Arabic numbers with a full point and space before the verse number, though the older style of a Roman numeral or colon is also found.

The Sunna or Sunnah is a collection of the sayings and deeds of the Prophet; the tradition of these sayings and deeds is called Hadith.

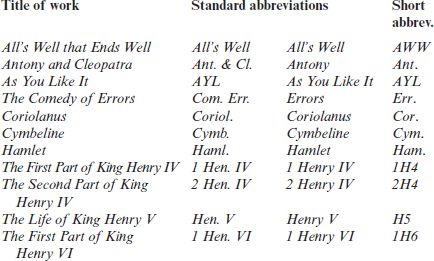

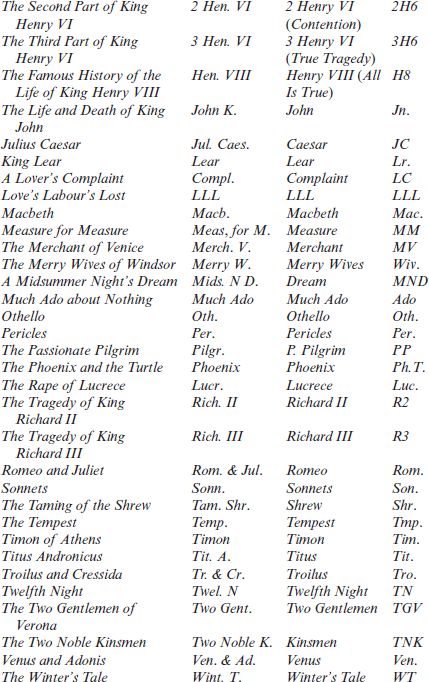

8.4 References to Shakespeare

The standard Oxford edition of Shakespeare is The Complete Works, edited by Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor (Oxford University Press, 1986, compact edn 1988). No single accepted model exists for abbreviating the titles of Shakespeare’s plays and poems, although in many cases the standard modern form by which the work is commonly known may be thought to be abbreviated already, since the complete original titles are often much longer. For example, The First Part of the Contention of the Two Famous Houses of York and Lancaster is best known as The Second Part of King Henry VI, and The Comical History of the Merchant of Venice, or Otherwise Called the Jew of Venice as The Merchant of Venice. The table below shows the more commonly found forms used by scholars. Column two gives the forms used in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary; column three gives those specified for the Oxford editions series. Column four lists still shorter forms, which are useful where space is at a premium and in the references of specialist texts where familiarity with the conventions is assumed.

‘F1 and ‘F2’ are sometimes used to mean the First Folio and Second Folio respectively, and ‘Q’ to mean the Quarto edition.

8.5 Films, broadcast works, and digital media

Content may be experienced by the user in many ways other than through print. Electronic games, ebooks, audio books, websites, and apps are a few examples. The treatment of titles is generally similar to that of printed works.

8.5.1 Films and broadcast works

The titles of films and broadcast works (both individual programmes and series) are set in italic. The titles of episodes in series are set in roman in quotation marks. They are commonly given full capitalization, though minimal capitalization is acceptable if applied consistently. If necessary further information about the recording may be included in open text or within parentheses:

Look Back in Anger

West Side Story

the film A Bridge Too Far (1977)

his first radio play, Fools Rush In, was broadcast in 1949

the Granada TV series Nearest and Dearest

the American television series The Defenders (‘The Hidden Fury’, 1964)

the video Stones in the Park (1969)

8.5.2 Digital media

The titles of apps and podcasts should be treated like free-standing publications, set in italics with important capitals. Titles of ebooks and audio books should follow the same style as a print edition.

Discover great days out with the new Trust Trails app for iPhone and iPad

From altruism to Wittgenstein, philosophers, theories and key themes, download the In Our Time philosophy podcast

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes is available in a variety of ebook formats from Project Gutenberg

Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native, in a new reading by Nicholas Rowe

Website titles are set roman, without quotation marks, although websites that also have a print version are treated in the same way as their hard-copy cousins; weblog (blog) titles may be roman or italic but should be treated consistently.

Please join me on Facebook, and follow me on Twitter.

Hans Rosling’s Gapminder blog

The British National Formulary is available as a book, a website and a mobile app.

Titles of web pages (within a website) and individual blog posts or podcast items are roman with quotation marks:

the ‘Morris Dance’ page of Wikipedia

in the Language blog post ‘Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg Address’

Titles of periodicals such as Slate and the Huffington Post, which are published online only, are treated like print titles, in italics with essential capitals; sites that feature their domain names as part of their title are usually treated similarly with important capitals even if the URL is rendered in lower case: Politics.co.uk, NYTimes.com.

Electronic games include video games, arcade games, and console games. Their titles are set in italic and given maximal capitalization:

Team Fortress 2

the Pikmin series

The Sims 3: University Life is the ninth expansion pack

Database names are set roman with essential capitals, e.g. the British Armorial Bindings database. Computer filenames, when referenced in running text, should be set roman and should include the file extension (filename.docx).

8.6 Musical works

8.6.1 General principles

The styling of musical work titles is peculiarly difficult because of the diversity of forms in which some titles may be cited, issues related to language, and longstanding special conventions. The most comprehensive source for the correct titles of musical works is The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London, 2001), available as part of Oxford Music Online.

8.6.2 Popular music and traditional songs

Song titles in English are set in roman type with quotation marks, capitalized according to the style adopted for titles in general:

| ‘Three Blind Mice’ | ‘Brown-Eyed Girl’ |

This is irrespective of whether the title forms a sentence with a finite verb:

‘A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square’

‘Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag’

In contrast, traditional ballads and songs, which draw their titles directly from the first line, may follow the rules for poetry. Here, only the first and proper nouns are capitalized:

| ‘Come away, death’ | ‘What shall we do with the drunken sailor?’ |

The names of albums, CDs, and collections are given in italic, with no quotation marks:

| A Love Supreme | Forever Changes |

| Younger Than Yesterday | In the Land of Grey and Pink |

This results in the combination of, for example, ‘Born to Run’, from Born to Run (roman in quotation marks for song, italic for album).

8.6.3 True titles

A distinction is usually made between works with ‘true’ titles and those with generic names. The boundary between the two types of title is not always clear, but, as with all other difficult style decisions, sense and context provide guidance, and consistency of treatment within any one publication is more important than adherence to a particular code of rules.

True titles are set in italic type with maximal or minimal capital initials according to the prevailing style of the publication:

| Britten’s The Burning Fiery Furnace | Elgar’s The Apostles |

| Tippett’s A Child of our Time |

Foreign-language titles are usually retained (and styled according to the practice outlined in 8.8 below). By convention, however, English publications always refer to some well-known works by English titles, especially when the original title is in a lesser-known language:

| Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique | Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin |

| Liszt’s Années de pelerinage |

but

Berg’s Lyric Suite

Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring

Operas and other dramatic works may be named in the original language or in English according to any sensible and consistent system—for example, in the original language if the reference is to a performance in that language, in English if the reference is to a performance in translation. A translated title may be given if the reader may not otherwise recognize the work:

Mozart’s The Magic Flute

Janáček’s Z mrtvého domu (‘From the house of the dead’)

Some works, however, are by convention always named in the original language:

| Puccini’s La Bohème | Weber’s Der Freischütz |

The titles of individual songs, arias, anthems, and movements are styled in roman in quotation marks, as are nicknames (that is, those not provided by the composer):

‘Skye Boat Song’

‘Dove sono’ from The Marriage of Figaro

the sacred madrigal ‘When David heard that Absalom was dead’

the ‘Rigaudon’ from Le Tombeau de Couperin

the ‘Jupiter’ Symphony

the ‘Enigma Variations’

It is customary to use minimal capital initials for titles derived from the words of a song (see 8.6.2).

8.6.4 Generic names

Titles derived from the names of musical forms are set in roman type with initial capitals. Identifying numbers in a series of works of the same form, opus numbers, and catalogue numbers are all given in Arabic numerals; the abbreviations ‘op.’ and ‘no.’ may be capitalized or not, while the capital abbreviations that preface catalogue numbers are often set in small capitals without a full point and closed up to the numeral (though Oxford style is to use full capitals and a full point and to space off the numeral). The names of keys may use musical symbols # and ♭ or the words ‘sharp’ and ‘flat’. Note the capitalization, punctuation, and spacing in the examples below:

Bach’s Mass in B minor or B Minor Mass

Brahms’s Symphony no. 4/Fourth Symphony

Handel’s Concerto Grosso in G major, op. 3, no. 3

Mozart’s Piano Trio, K496

Beethoven’s String Quartet in C sharp minor, op. 131 or … C# minor, op. 131

Tempo marks used as the titles of movements are also set in roman type with initial capitals, as are the sections of the mass and other services:

the Adagio from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony

the Credo from the Missa solemnis

the Te Deum from Purcell’s Morning Service in D

8.6.5 Hybrid names

Certain titles are conventionally styled in a mixture of roman and italic type. They include works that are named by genre and title such as certain overtures and masses:

| the Overture Portsmouth Point | the Mass L’Homme armé |

Note, however, that in other styles the generic word is treated as a descriptor:

| the march Pomp and Circumstance, no. 1 | the Firebird suite |

Instrumentation that follows the title of a work may be given descriptively in roman with lower-case initials, or as part of the title. A number of twentieth-century works, however, include their instrumentation as an inseparable part of the title.

Three Pieces for cello and piano

but

| Serenade for Strings | Concerto for Orchestra |

8.7 Works of art

8.7.1 General principles

The formal titles of works of visual art, including paintings, sculptures, drawings, posters, and prints, are set in italic. Full capitalization is still usual, though with longer titles there may be difficulties in deciding which words should be capitalized:

Joseph Stella, Brooklyn Bridge

The Mirror of Venus

the etching Adolescence (1932) and the painting Dorette (1933)

the huge chalk and ink drawing St Bride’s and the City after the Fire, 29th December 1940

the wartime poster Your Talk may Kill your Comrades (1942)

Consistently minimal capitalization is also possible for works of art:

Petrus Christus’s Portrait of a young man

Works may be referred to either by a formal title or by a more descriptive form:

he painted a portrait entitled James Butler, 2nd duke of Ormonde, when Lord Ossory

he painted a portrait of James Butler (later second duke of Ormonde) when the subject was Lord Ossory

Titles bestowed by someone other than the artist or sculptor are usually given in roman with no quotation marks:

| La Gioconda | the Venus de Milo |

Works that discuss numerous works of art need consistent conventions and abbreviations for the parenthetical presentation of such information as the medium, dimensions, date of creation or date and place of first exhibition, and the current ownership or location of the works mentioned:

Andromeda (bronze, c.1851; Royal Collection, Osborne House, Isle of Wight)

The Spartan Isadas (exh. RA, 1827; priv. coll.)

8.7.2 Series of works of art

Place the titles of series of unique works of art in roman type with maximal capitalization and without quotation marks. Series of published prints may be given italic titles:

a series of paintings of children, Sensitive Plants, with such names as Sweet William and Mary Gold

his finest series of prints, Gulliver’s Travels and Pilgrim’s Progress

8.8 Non-English work titles

For general guidance on works in languages other than English see Chapter 12. The rules governing the capitalization of titles in some languages, such as French, are complex, and in less formal contexts it is acceptable to treat foreign-language titles in the same way as English ones.

Take care to distinguish the title, date of publication, and author of the original from the title, date, and translator of an English version. Ideally the title of the translation should not be used as if it were the title of the original work, but this rule may be relaxed in some contexts.

English titles may be used for works performed in English translation. The common English titles of classical works may be used in place of the Greek or Latin originals, and common English or Latin titles may be used for ancient or medieval works originally written in Greek, Arabic, or Persian:

Virgil’s Eclogues

Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine

Aristotle’s De caelo et mundo

The title in the original language may be accompanied by an English translation, especially if its sense is not implied by the surrounding text. Place such translations in quotation marks within parentheses (square brackets are sometimes used), in roman type with an initial capital on the first word. The true titles of published translations are set in italics, like those of other publications.

Auraicept na n-éces (‘The primer of the poets’)

the lament ‘O, Ailein duinn shiùbhlainn leat’ (‘Oh, brown-haired Allan, I would go with you’)

a translation of Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique (as A Dictionary of Philosophy, 1824)

Except in specialist contexts the titles of works in non-Roman alphabets are not reproduced in their original characters but are transliterated according to standard systems (with minimal capitalization) or replaced by English translations. Words actually printed in transliteration in a title are rendered as printed, not brought into line with a more modern style of transliteration:

Ibn Sīnā’s Kitāb shifā’ al-nafs

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard

his translation of the Bhagavadgita was published in London (as The Bhagvat-geeta) in 1785

8.9 Integration of titles into text

Integrate the title of a work syntactically into the sentence in which it is mentioned.

Do not separate an author’s name from a work title simply by a comma; where appropriate employ a possessive form. An initial definite or indefinite article may be omitted from a title if this helps the sentence to read more smoothly:

the arguments in Darwin’s Origin of Species

Always treat the title of a work as singular, regardless of its wording:

his Experiences of a Lifetime ranges widely

Phrasing that places the title of a work as the object of the prepositions on or about (as in the third of the following examples) should be avoided. The style should be:

a paper on the origins of the manor in England

a paper, ‘The origins of the manor in England’

not

a paper on ‘The origins of the manor in England’

When part or all of a book’s title or subtitle, or any other matter from the title page, is quoted it should be styled as a quotation, not as a work title, that is in roman not italic type and with the original punctuation and capitalization (unless full capitals) preserved:

The Enimie of ldlenesse, printed in 1568, was presented as a manual ‘Teaching the maner and stile how to endite, compose, and write all sorts of Epistles and Letters’