CHAPTER 3

Spelling and hyphenation

3.1 Spelling

3.1.1 General principles

A good dictionary such as the Concise Oxford English Dictionary or the Oxford Dictionary of English should be consulted on matters of spelling and inflection; for US English texts a dictionary such as the New Oxford American Dictionary is indispensable. The dictionary will give guidance on recommended spellings and acceptable variants, and cover irregular or potentially problematic inflections. The main rules of spelling and inflection are outlined below.

English has an exceptional tolerance for different spellings of the same word. Some, such as bannister and banister, are largely interchangeable, although a dictionary will always indicate which is the preferred or dominant version. Other words tend to be spelled differently in different contexts: for instance, judgement is spelled thus in general British contexts, but is spelled judgment in legal contexts and US English. On the other hand, accomodation and millenium are commonly encountered in print but are not regarded as correct or acceptable spellings of accommodation and millennium.

Unless specifically instructed to follow the preferred spellings of a particular dictionary, an editor does not generally need to alter instances where a writer has consistently used acceptable variants, such as co-operate or caviare, rather than the preferred spellings, which in current Oxford dictionaries are cooperate and caviar. However, comparable or related words should be treated similarly: for instance, if bureaus rather than bureaux is used then prefer chateaus to chateaux, and standardize on -ae- spellings in words such as mediaeval if the author has consistently written encyclopaedia. For more on house style and editorial style see 2.3.1 and 2.3.2.

3.1.2 British and US spelling

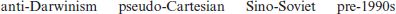

Certain general tendencies can be noted in US spelling:

In British spelling fetus is used in technical texts but foetus in general readership; US usage is always fetus.

For sulfur/sulphur see 21.4.1.

Further details are given in sections 3.1.3 to 3.1.9 and in Chapter 21.

3.1.3 Verbs ending in -ise or -ize

For most verbs that end with -ize or -ise, either termination is acceptable in British English. The ending -ize has been in use in English since the 16th century, and is not an Americanism, although it is the usual form in US English today. The alternative form -ise is far more common in British than it is in US English. Whichever form is chosen, ensure that it is applied consistently throughout the text.

Oxford University Press has traditionally used -ize spellings. These were adopted in the first editions of the Oxford English Dictionary, Hart’s Rules, and the Authors’ and Printers’ Dictionary (the predecessor of the Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors). They were favoured on both phonetic and etymological grounds: -ize corresponds more closely to the Greek root of most -ize verbs, -izo.

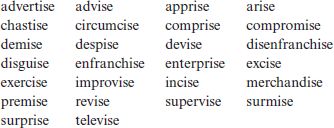

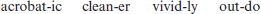

For some words, however, -ise is obligatory: first, when it forms part of a larger word element such as -cise (= cutting), -mise (= sending), -prise (= taking), or -vise (= seeing); and second, when it corresponds to nouns with -s- in the stem, such as advertise and televise. Here is a list of the commoner words in which an -ise ending must be used in both British and US English:

In British English, words ending -yse (analyse, paralyse) cannot also be spelled -yze. In US English, however, the -yze ending is usual (analyze, paralyze).

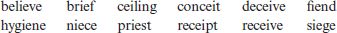

3.1.4 -ie- and -ei-

The well-known spelling rule ‘i before e except after c’ is generally valid when the combination is pronounced -ee-:

There are exceptions, notably seize. Caffeine, codeine, and protein are all formed from elements ending in -e followed by -in or -ine, and plebeian is from the Latin plebeius.

The rule is not valid when the syllable is pronounced in other ways, as in beige, freight, neighbour, sleigh, veil, vein, and weigh (all pronounced with the vowel as in lake); in eider, feisty, height, heist, kaleidoscope, and sleight (all pronounced with the vowel as in like); and in words in which the i and e are pronounced as separate vowels, such as holier and occupier.

3.1.5 -able and -ible

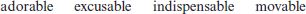

The rules governing adjectives that end in -able or -ible relate to etymology: adjectives ending in -able generally owe their form to the Latin ending -abilis or the Old French -able, and words in -ible to the Latin -ibilis. When new adjectives are formed from English roots they take -able, as in conceivable and movable. New words are not generally formed with the -ible suffix.

With some exceptions, words ending in a silent -e lose the e when -able is added:

However, in British English some words of one syllable keep the final e when its loss could lead to ambiguity:

In words ending -ce or -ge the e is retained to preserve the soft c or g:

| bridgeable | changeable | knowledgeable |

| manageable | noticeable | serviceable |

whereas if the word ends with a hard c or g the ending is always -able:

| amicable | navigable |

In US usage, before a suffix beginning with a vowel the final -e is often omitted where in British usage it is retained, as in blamable, likable, and sizable. But it is always retained after a soft c and g, as in British usage.

3.1.6 Nouns ending in -ment

When -ment is added to a verb which ends in -dge, the final e is retained in British English:

abridgement

acknowledgement

judgement (but note that judgment is the usual form in legal contexts)

In US English the form without the e is more usual (abridgment, acknowledgment, judgment).

3.1.7 Nouns ending in -logue

Some—but not all—nouns that end in -logue in British English are often spelled -log in US English. Analogue and catalogue usually end in -log in America, and a few other words, such as dialogue and homologue, have the -log form as an accepted variant.

3.1.8 -ce and -se endings

Practice is the spelling of the noun in both British and US English, and it is also the spelling of the verb in the US. However, in British English the verb is spelled practise. Licence is the spelling of the noun and license of the verb in British English, whereas in US English both the noun and the verb are license.

US spellings of defence and pretence are defense and pretense.

3.1.9 -ae- in the middle of words

The -ae- spellings of encyclopaedia and mediaeval are being superseded by the forms encyclopedia and medieval, although they are still acceptable variants. The dated ligature -æ- should be avoided, although note that the title of the Encyclopædia Britannica is styled thus. Archaean, haematology and similar, largely technical words retain the -ae- in British English, but in US English are spelled Archean, hematology, etc. The -e- spelling is predominant in technical writing, whether British or US in origin.

3.2 Inflection

The chief rules whereby words change form to express a grammatical function are described below. In some cases there are acceptable variant forms in addition to those forms shown.

3.2.1 Verbs

Verbs of one syllable ending in a single consonant double the consonant when adding -ing or -ed:

beg, begging, begged

rub, rubbing, rubbed

When the final consonant is w, x, or y this is not doubled:

tow, towing, towed

vex, vexing, vexed

When the final consonant is preceded by more than one vowel (other than u in qu), or by a diphthong that represents a long vowel, the consonant is not normally doubled:

appeal, appealing, appealed

boil, boiling, boiled

clean, cleaning, cleaned

conceal, concealing, concealed

reveal, revealing, revealed

Verbs of more than one syllable ending in a single consonant double the consonant when the stress is placed on the final syllable:

allot, allotting, allotted

occur, occurring, occurred

Verbs that do not have stress on the final syllable do not double the consonant:

benefit, benefiting, benefited

budget, budgeting, budgeted

gallop, galloping, galloped

offer, offering, offered

profit, profiting, profited

target, targeting, targeted

Exceptions are:

input, inputting, inputted

output, outputting, outputted

kidnap, kidnapping, kidnapped

worship, worshipping, worshipped

Another exception is focus, focusing, focused, which can double the s as an acceptable alternative: focussing, focused.

Verbs ending in -l normally double the l in British English regardless of where the stress occurs in the word:

annul, annulling, annulled

enrol, enrolling, enrolled

grovel, grovelling, grovelled

travel, travelling, travelled

Exceptions in British English are:

parallel, paralleling, paralleled

In US English the final l generally doubles only when the stress is on the final syllable. So words such as annul and enrol inflect the same way in America as they do in Britain, but these verbs are different:

grovel, groveling, groveled

travel, traveling, traveled

tunnel, tunneling, tunneled

In some cases US English spells the basic form of the verb with -ll as well (enroll, fulfill).

Note that install has a double l in both British and US English, but instalment has a single l in British spelling and doubles it in US English.

Verbs generally drop a final silent e when the suffix begins with a vowel:

argue, arguing, argued

continue, continuing, continued

But a final e is usually retained to preserve the soft sound of the g in ageing, twingeing, whingeing (but not in US English). Singeing (from singe) and swingeing (from swinge) are thus distinguished from the corresponding forms singing (from sing) and swinging (from swing). Raging is an exception. An e is added to dyeing (from dye) to distinguish it from dying (from die).

A group of verbs—burn, learn, spell—have an orthodox past tense and past participle ending in -ed, but in British English also have an alternative form ending in -t (burnt, learnt, spelt). Note that the past of earn is always earned, never earnt, and that of deal is dealt, not dealed, in both British and US English.

3.2.2 Plurals of nouns

Nouns ending in -y form plurals with -ies (policy, policies), unless the ending is -ey, in which case the plural form is normally -eys (valley, valleys).

Proper names ending in -y retain it when pluralized, and do not need an apostrophe:

the Carys

the three Marys

Nouns ending in -f and -fe form plurals sometimes with -fs or -fes:

handkerchief, handkerchiefs

proof, proofs

roof, roofs

safe, safes

sometimes -ves:

calf, calves

half, halves

knife, knives

shelf, shelves

and occasionally both -fs and -ves:

dwarf, dwarfs or dwarves

hoof, hoofs or hooves

For nouns ending in -o there is no fixed system. As a guideline, the following typically form plurals with -os:

Names of animals and plants normally form plurals with -oes (buffaloes, tomatoes). In other cases practice varies quite unpredictably: kilos and pianos, dominoes and vetoes are all correct. With some words a variant is well established; for example, both mementoes and mementos are used.

Compound nouns

Compound words formed by a noun and a following adjective, or by two nouns connected by a preposition, generally form their plurals by a change in the key word:

| Singular | Plural |

| Attorney General | Attorneys General |

| brother-in-law | brothers-in-law |

| commander-in-chief | commanders-in-chief |

| court martial | courts martial or court martials |

| cul-de-sac | cul-de-sacs or culs-de-sac |

| father-in-law | fathers-in-law |

| fleur-de-lis | fleurs-de-lis |

| Governor General | Governors General |

| Lord Chancellor | Lord Chancellors |

| man-of-war | men-of-war |

| mother-in-law | mothers-in-law |

| passer-by | passers-by |

| Poet Laureate | Poets Laureate or Poet Laureates |

| point-to-point | point-to-points |

| sister-in-law | sisters-in-law |

| son-in-law | sons-in-law |

Plurals of animal names

The plurals of some animal names are the same as the singular forms, for example deer, grouse, salmon, sheep. This rule applies particularly to larger species and especially to those that are hunted or kept by humans. In some contexts the -s is optional: the usual plural of lion is lions, but a big-game hunter might use lion as a plural. For this reason the style is sometimes known as the ‘hunting plural’: it is never applied to small animals such as mice or rats.

The normal plural of fish is fish:

| a shoal of fish | he caught two huge fish |

The older form fishes may still be used in reference to different kinds of fish:

freshwater fishes of the British Isles

Foreign plurals

Plurals of foreign (typically Latin, Greek, or French) words used in English are formed according to the rules either of the original language:

alumnus, alumni

genus, genera

nucleus, nuclei

stratum, strata

or of English:

arena, arenas

suffix, suffixes

Often more than one form is in use:

bureau, bureaus or bureaux

chateau, chateaus or chateaux

crematorium, crematoriums or crematoria

referendum, referendums or referenda

The plural of formula is now more commonly formulas than formulae in British and US English, even in mathematical or chemical contexts. In general the English form is preferred: for example, use stadiums rather than stadia, and forums rather than fora, unless dealing with the ancient world. Incidentally, index generally has the plural indexes in reference to books, with indices being reserved for statistical or mathematical contexts; conversely, appendices tends to be used for subsidiary tables and appendixes in relation to the body part. Always check such words in a dictionary if in any doubt.

Words ending in -is usually follow the original Latin form:

basis, bases

crisis, crises

3.2.3 Adjectives

Adjectives that form comparatives and superlatives through the addition of the suffixes -er and -est are:

Words of one syllable ending in a single consonant double the consonant when it is preceded by a single vowel

glad, gladder, gladdest

hot, hotter, hottest

but not when it is preceded by more than one vowel or by a long vowel indicated by a diphthong

clean, cleaner, cleanest

loud, louder, loudest

Words of two syllables ending in -l double the l in British English:

cruel, crueller, cruellest

Adjectives of three or more syllables use forms with more and most (more beautiful, most interesting, etc.).

3.2.4 Adverbs

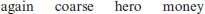

Adverbs ending in -ly formed from adjectives (e.g. richly, softly, wisely) generally do not have -er and -est forms but appear as more softly, most wisely, etc. Adverbs that form comparatives and superlatives with -er and -est are:

3.3 Hyphenation

3.3.1 General principles

Since hyphenation often depends on the word’s or phrase’s role and its position in a sentence, and because it is to an extent dependent on adopted style or personal taste, it cannot be covered fully in a dictionary. This section sets out the basic principles and current thinking on hyphens.

3.3.2 Soft and hard hyphens

There are two types of hyphen. The hard hyphen joins words or parts of words together to form compounds (e.g. anti-nuclear, glow-worm, second-rate). Use of the hard hyphen is described in the rest of this section. The soft hyphen indicates word division when a word is broken at the end of a line; for the soft hyphen and word division see 3.4.

3.3.3 Compound words

A compound term may be open (spaced as separate words), hyphenated, or closed (written as one word). However, there is an increasing tendency to avoid hyphenation for noun compounds: Oxford Dictionaries Online specifies airstream rather than air-stream and air raid rather than air-raid, for example.

It is, of course, vital to make sure that individual forms are used consistently within a single text or range of texts. If an author has consistently applied a scheme of hyphenation, an editor need not alter it, although a text littered with hyphens can look fussy and dated. Editors can find the dominant form of a particular compound in a suitable current dictionary such as the New Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors.

Some compounds are hyphenated where there is an awkward collision of vowels or consonants:

| drip-proof | take-off | part-time |

but even here some are now typically written as one word:

| breaststroke | earring | hitchhiker |

Formerly in British English, a rule was followed whereby a combination of present participle and noun was spaced if the noun was providing the action (the walking wounded) but hyphenated if the compound itself was acted upon (a walking-stick—that is, the stick itself was not walking). The so-called ‘walking-stick rule’ is no longer borne out in common use: walking stick and many other such combinations (clearing house, colouring book, dining room) are now written as two words.

Compound modifiers that follow a noun do not need hyphens:

| the story is well known | the records are not up to date |

| an agreement of long standing | poetry from the nineteenth century |

but a compound expression preceding the noun is generally hyphenated when it forms a unit modifying the noun:

| a well-known story | up-to-date records |

| a long-standing agreement | nineteenth-century poetry |

A distinction may be made between compounds containing an adjective, such as first class or low level, and compound nouns, such as labour market: when compounds of the first sort are used before a noun they should be hyphenated (first-class seats, low-level radioactive waste), but the second sort need not be (labour market liberalization).

Compound adjectives formed from an adjective and a verb participle should be hyphenated whether or not they precede the noun:

| double-breasted suits | Darren was quite good-looking |

Where a compound noun is two words (e.g. a machine gun), any verb derived from it is normally hyphenated (to machine-gun). Similarly, compounds containing a noun or adjective that is derived from a verb (glass-making, nation-builder) are more often hyphenated than non-verbal noun or adjective compounds (science fiction, wildfire).

House styles vary greatly in their treatment of compound nouns and it is worth choosing a good dictionary such as the Oxford Dictionary of English or Oxford Dictionaries Online for guidance, but if a specific preference is not stated, it is as well to decide on your own choices for, e.g., decision maker/decision-making, and apply them consistently. Most styles seem to agree on policymaker but not on which to use out of policymaking, policy-making, or policy making for example. Much depends on the familiarity of the readership with a particular usage, for example the compound noun climate change would be unacceptable if hyphenated and jobseeker would jar as two words, at least in the UK, where Jobseeker’s Allowance is an accepted term. Agreement on the hyphenation of compound adjectives is more common:

| decision-making process | cake-making equipment |

but again there is a drift towards using one or two words

| an international peacekeeping force | high quality teaching |

unless ambiguous

cross-training of staff rather than cross training of staff

When a phrasal verb such as to hold up or to back up is made into a noun a hyphen is added or it is made into a one-word form (a hold-up, some backup). Note, however, that normal phrasal verbs should not be hyphenated:

| continue to build up your pension | time to top up your mobile phone |

not

| continue to build-up your pension | time to top-up your mobile phone |

Do not hyphenate adjectival compounds where the first element is an adverb ending in -ly:

| a happily married couple | a newly discovered compound |

Adverbs that do not end in -ly should be hyphenated when used in adjectival compounds before a noun, but not after a noun:

a tribute to the much-loved broadcaster

Dr Gray was very well known

Do not hyphenate italic foreign phrases unless they are hyphenated in the original language:

an ex post facto decision

an ad hominem argument

the collected romans-fleuves

a sense of savoir-vivre

Once foreign phrases have become part of the language and are no longer italicized, they are treated like any other English words, and hyphenated (or not) accordingly:

a laissez-faire policy

a bit of savoir faire

In general do not hyphenate capitalized compounds (although see 4.11.1):

British Museum staff

New Testament Greek

Latin American studies

Compound scientific terms are generally not hyphenated—they are either spaced or closed:

herpesvirus

radioisotope

liquid crystal display

sodium chloride solution

Capitalizing hyphenated compounds

When a title or heading is given initial capitals, a decision needs to be made as to how to treat hyphenated compounds. The traditional rule is to capitalize only the first element unless the second element is a proper noun or other word that would normally be capitalized:

First-class and Club Passengers

Anti-aircraft Artillery

In many modern styles, however, both elements are capitalized:

First-Class and Club Passengers

Anti-Aircraft Artillery

3.3.4 Prefixes and combining forms

Words with prefixes are often written as one word (predetermine, antistatic, subculture, postmodern), especially in US English, but use a hyphen to avoid confusion or mispronunciation, particularly where there is a collision of vowels or consonants:

but predate (existing before a certain date) despite potential confusion with the meaning to catch prey.

Note that cooperate, coordinate, and microorganism are generally written thus, despite the collision of os, and preoperative is used to accord with postoperative.

A hyphen is used to avoid confusion where a prefix is repeated (re-release, sub-subcategory) or to avoid confusion with another word (re-form/reform, re-cover/recover).

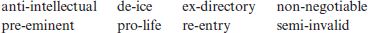

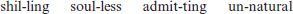

Hyphenate prefixes and combining forms before a capitalized name, a numeral, or a date:

When it denotes a previous state, ex- is usually followed by a hyphen, as in ex-husband, ex-convict. There is no satisfactory way of dealing with the type ex-Prime Minister, in which the second element is itself a compound. A second hyphen, e.g. ex-Prime-Minister, is not recommended, and rewording is the best option. The use of former instead of ex- avoids such problems, and is more elegant. Note that in US style an en rule is used to connect a prefix and a compound (the post–World War I period).

The prefix mid- is now often considered to be an adjective in its own right in such combinations as the mid nineteenth century; before a noun, of course, all compounds with mid should be hyphenated:

| a mid-grey tone | a mid-range saloon car |

Email and website are commonly one word (but web page); ebook is gaining ground over e-book but less familiar terms such as e-learning are currently hyphenated.

3.3.5 Suffixes

Suffixes are always written hyphenated or closed, never spaced.

The suffixes -less and -like need a hyphen if there are already two ls in the preceding word:

| bell-less | shell-like |

Use a hyphen in newly coined or rare combinations with -like, and with names, but more established forms, particularly if short, are set solid:

| tortoise-like | Paris-like | ladylike |

| catlike | deathless | husbandless |

The suffixes -proof, -scape, and -wide usually need no hyphen:

| childproof | moonscape | nationwide |

When a complete word is used like a suffix after a noun, adjective, or adverb it is particularly important to use a hyphen, unless the word follows an adverb ending with -ly:

military-style ‘boot camps’

some banks have become excessively risk-averse

GPS-enabled tracking

an environmentally friendly policy

There can be a real risk of ambiguity with such constructions: compare

a cycling-friendly chief executive

rent-free accommodation in one of the pokey little labourer’s cottages

with

a cycling friendly chief executive

rent free accommodation in one of the pokey little labourer’s cottages

3.3.6 Numbers

Use hyphens in spelled-out numbers from 21 to 99:

| twenty-three | thirty-fourth |

For a full discussion of numbers see Chapter 11.

3.3.7 Compass points

Compass points are hyphenated:

| south-east | south-by-east | south-south-east |

but the compound names of winds are closed:

| southeaster | northwesterly |

In US usage individual compass points are compound words:

| southeast | south-southeast |

Capitalized compounds are not usually hyphenated: note that, for example, South East Asia is the prevailing form in British English and Southeast Asia in US English.

3.3.8 Other uses

Use hyphens to indicate stammering, paused, or intermittent speech:

‘P-p-perhaps not,’ she whispered.

‘Uh-oh,’ he groaned.

Use hyphens to indicate an omitted common element in a series:

| three- and six-cylinder models | two-, three-, or fourfold |

| upper-, middle-, and lower-class accents | countrymen and -women |

When the common element may be unfamiliar to the reader, it is better to spell out each word:

ectomorphs, endomorphs, and mesomorphs

Hyphens are used in double-barrelled names:

Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis (Krafft-Ebing is one man’s surname)

In compound nouns and adjectives derived from two names an en rule is usual (Marxism–Leninism), although for adjectives of this sort a hyphen is sometimes used (Marxist-Leninist). A hyphen, rather than an en rule, is always used where the first element of a compound cannot stand alone as an independent word, as in Sino-Soviet relations. See 4.11.1.

3.4 Word division

3.4.1 General principles

Words can be divided between lines of printing to avoid unacceptably wide spaces between words (in justified setting) or at the end of a line (in unjustified setting). The narrower the column, the more necessary this becomes. Some divisions are better than others, and some are unacceptable because they may mislead or confuse the reader. Rules governing division are based on a combination of a word’s construction (i.e. the parts from which it is formed) and its pronunciation, since exclusive reliance on either can yield unfortunate results. The following offers general guidance only; for individual cases, consult the New Oxford Spelling Dictionary. See also 2.5.2 for a discussion of the general principles of page layout and proofreading. For word division in foreign languages, see Chapter 12, under the languages concerned.

A hyphen is added where a word is divided at the end of a line. This is known as a soft hyphen or discretionary hyphen:

con-

trary

If a word with a hard hyphen is divided after its permanent (keyed) hyphen, no further hyphen is added:

well-

developed

In most texts the hyphens in the examples above (con-trary and well-developed) will use the same symbol (-). Sometimes, as in dictionaries or other reference works in which it is important for the reader to know whether an end-of-line hyphen is a permanent one or not, a different symbol, such as -, is used when words are divided:

con-

trary

A tilde (~) is also occasionally used:

con~

trary

In copy to be keyed, add a ‘close up’ mark (see Appendix Proofreading marks) to any permanent (hard) hyphen that falls at the end of a line, to indicate that it must be typed and set close to the next word. A stet mark (from Latin, ‘let it stand’) was formerly used, marked as three dots under the character.

3.4.2 Principles of word division

The main principle governing the guidelines that follow is that the word division should be as unobtrusive as possible, so that the reader continues reading without faltering or momentary confusion. All word divisions should correspond as closely as possible to a syllable division:

| con-tact | jar-gon |

However, syllable division will not be satisfactory if the result is that the first part is misleading on its own and the second part is not a complete recognizable suffix. For example, do not divide abases, as neither aba-ses nor abas-es are acceptable.

An acceptable division between two parts of one word may be unacceptable when applied to the same form with a suffix or prefix: help-ful is perfectly acceptable, but unhelp-ful is not as good as un-helpful.

The New Oxford Spelling Dictionary therefore uses two levels of word division—‘preferred’ divisions (marked |), which are acceptable under almost any circumstances, and ‘permitted’ divisions (marked ¦), which are not as good, given a choice. Thus unhelpful is shown as un|help¦ful.

The acceptability of a division depends to a considerable extent on the appearance of each part of the word, balanced against the appearance of the spacing in the text. For instance, even a division that is neither obtrusive nor misleading, such as con-tact, may be possible but quite unnecessary at the end of a long line of type, whereas a poorer division, such as musc-ling, may be necessary in order to avoid excessively wide word spaces in a narrow line. In justified setting, word spaces should not be so wide that they appear larger than the space between lines of type.

Whether the best word division follows the construction or the pronunciation depends partly on how familiar the word is and how clearly it is thought of in terms of its constituent parts. For instance, atmosphere is so familiar that its construction is subordinated to its pronunciation, and so it is divided atmos-phere, but the less familiar hydrosphere is divided between its two word-formation elements: hydro-sphere.

3.4.3 Special rules

Do not divide words of one syllable:

| though | prayer | helped |

Do not leave only one letter at the end of a line:

aground (not a-ground)

Avoid dividing in such a way that fewer than three letters are left at the start of a line:

Briton (not Brit-on)

rubbishy (not rubbish-y)

However, two letters are acceptable at the start of a line if they form a complete, recognizable suffix or other element:

Nearly all words with fewer than six letters should therefore never be divided:

Divide words according to their construction where it is obvious, for example:

| table-spoon | railway-man |

| un-prepared | wash-able |

except where such a division would be severely at odds with the pronunciation:

| dem-ocracy (not demo-cracy) | chil-dren (not child-ren) |

| archaeo-logical but archae-ologist | psycho-metric but psych-ometry |

| human-ism but criti-cism | neo-classical but neolo-gism |

When the construction of a word is no help, divide it after a vowel, preferably an unstressed one:

| preju-dice | mili-tate | insti-gate |

or between two consonants or two vowels that are pronounced separately:

| splen-dour | Egyp-tian | appreci-ate |

Divide after double consonants if they form the end of a recognizable element of a word:

| chill-ing | watt-age |

but otherwise divide between them:

Words ending in -le, and their inflections, are best not divided, but the last four letters can be carried over if necessary:

| brin-dled | rat-tled |

With the present participles of these verbs, divide the word after the consonant preceding the l:

| chuck-ling | trick-ling |

or between two identical preceding consonants:

puz-zling

Divide most gerunds and present participles at -ing:

| carry-ing | divid-ing | tell-ing |

Avoid divisions that might affect the sound, confuse the meaning, or merely look odd:

| exact-ing (not ex-acting) | co-alesce (not coal-esce) |

| le-gend (not leg-end) | lun-ging (not lung-ing) |

| re-appear (not reap-pear) | re-adjust (not read-just) |

Words that cannot be divided at all without an odd effect should be left undivided:

Hyphenated words are best divided only at an existing hard hyphen but can, if necessary, be divided a minimum of six letters after it:

counter-revolution~

ary

Even where no hyphen is involved, certain constraints must be observed on line breaks:

UNESCO

AFL-|CIO

1914–|18

| 15 kg | 300 BC |

| Louis XIV | Samuel Browne, Jr. |