CHAPTER 12

Languages

12.1 General principles

This chapter provides guidelines on the editing and presentation of material in foreign languages and Old and Middle English. Languages are listed alphabetically, either separately or, for clarity and convenience, with related languages: for instance, there is one section for Slavonic languages rather than separate sections for Belarusian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, etc.

The sections stress common pitfalls and conundrums in spelling, punctuation, accents, syntax, and typography, and are intended to offer guidance to users across a broad spectrum of familiarity with the languages. A full account of each language is not the aim; rather, it seeks to aid authors and editors who are dealing with foreign-language material within English-language contexts. Overall, those languages most often met with in English-language publishing are covered in greatest depth, though not all languages of equal frequency are—or can usefully be—addressed equally: with editorial concerns foremost, distinctions between related languages have been highlighted. Help is given on setting non-Roman alphabets in English-language texts, as well as on transliteration and romanization.

Typescripts containing extensive non-roman characters should be created with a Unicode-compliant font (see 2.5) to facilitate typesetting. Authors should consult their publisher about any font requirements specific to non-roman alphabets.

For information on foreign personal names and place names see Chapter 6.

12.2 Arabic

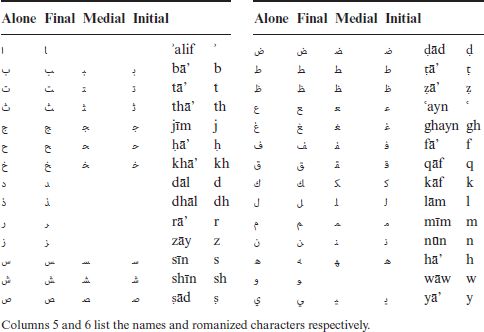

12.2.1 Alphabet

Arabic is written from right to left in a cursive script consisting of twenty-eight letters, all representing consonants; their form varies according to position within the word, and several are distinguished only by dots. Some letters cannot be joined to the next even within a word; the space between them should be smaller than that between words, and unbreakable. A horizontal extender on the baseline is often added to a letter that would otherwise seem too close to the next. In verse it is conventional to give all lines the same visual length, so that the rhyming letter is aligned on the left throughout.

The same script, with additional letters, is or has been employed for other languages spoken by Muslims, such as Persian, Pashto, Urdu, Turkish, and Malay; these last two are now written in the Roman alphabet.

There is no standard system of transliterating Arabic.

12.2.2 Accents and punctuation

Vowel marks and other guides to pronunciation are used in editions of the Koran, in schoolbooks, and usually in editions of classical poetry; otherwise they are omitted except where a writer thinks they are needed to resolve ambiguity. Strict philological usage requires the underline in ḏ, ṯ; the under-dot in ḥ, ṣ, ḍ, ṭ, ẓ; the over-dot in ġ; the inferior semicircle in (ḫ); the háček in ǧ (often written j) and š, and the macron in ā, ī, ū (do not use the acute or circumflex instead). Less learned systems will dispense with some or all of these diacritics. There are also two independent characters, ʿayn (ʿ) and hamza (ء) (corresponding to Hebrew ʿayin and aleph) which should be used if available; if not, substitute Greek asper (‘) and lenis (’) respectively. These should be distinguished from the apostrophe, mainly found before l-, e.g. in ʿAbdu ’l-Malik; insert a hair space (see 2.5.1) between them and quotation marks.

The definite article al or ’l- (or regional variants such as el- and ul-) is joined to the noun with a hyphen: al-Islām, al-kitāb. Do not capitalize the a except at the beginning of a sentence; it should not be capitalized at the start of a quoted title.

Table 12.1 Arabic alphabet

12.2.3 Word division

In Arabic script words should not be divided even at internal spaces; if the spacing of the line would otherwise be too loose, use extenders within words. In transliteration, avoid dividing except at the hyphen following the article; if absolutely necessary, take over no more than one consonant. In loose transcription, note that dh kh sh th may represent either the single consonants strictly transliterated ḏ, ḫ, š, and ṯ respectively, or combinations of d k s t plus h. When in doubt, do not divide.

12.3 Chinese

12.3.1 Introduction

The forms of Chinese spoken in areas occupied by those of Chinese origin differ so widely from one another that many may be deemed to constitute languages in their own right. The principal dialects are Northern Chinese (Mandarin), Cantonese, Hakka, the Wu dialect of Suzhou, and the dialect of Min (Fukien). All of these, however, share a common written language consisting of thousands of separate ideographs or ‘characters’. The language traditionally used for the compilation of official documents is totally unlike the spoken language, as is the language in which the classic texts of Chinese literature are expressed. For these, also, the same script is used.

12.3.2 Scripts

The structure of individual ideographs can sometimes be very complicated in script, involving the use of as many as twenty-eight separate strokes of the brush or pen. A code of simplified characters is in use on the mainland, but more traditional forms are found in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and areas beyond Chinese jurisdiction.

The language is monosyllabic, one ideograph representing a syllable. Each ideograph is pronounced in a particular inflection of voice, or ‘tone’. The National Language (the standard spoken form of modern Chinese) uses four separate tones, Cantonese, nine. The National Language is derived from the pronunciation of northern China (notably that of the Beijing area), which has traditionally been adopted for the transaction of official business—hence the term ‘Mandarin’, which is sometimes used to categorize it. Alternative names for it are putonghua (‘speech in common use’) or Kuo-yü (otherwise Guoyu, ‘National Language’).

The many thousand Chinese characters are traditionally written from top to bottom in vertical columns running right to left across the page, but nowadays, especially in mainland China, are printed in left-to-right lines like the Western alphabet. This has always been the practice when Chinese phrases are set within a Roman text.

12.3.3 Transliteration

Although the pronunciation of characters varies markedly from dialect to dialect (the surname pronounced Wu in Mandarin is Ng in Cantonese), romanization is normally based on Beijing (‘Mandarin’) usage. There are two main systems: Wade–Giles, formerly the norm in English-language publications, and Pinyin, the official transliteration in the People’s Republic. The name, in Wade–Giles, would be spelled P‘in-in. Wade–Giles gives forms such as T‘ien-tsin and Mao Tse-tung, whereas Pinyin gives Tianjin and Mao Zedong.

Wade–Giles separates the syllables of compounds with hyphens; Pinyin runs them together, with an apostrophe where the break would not be obvious (Xi’an = Wade–Giles Hsi-an, since Xian would be read as Wade–Giles Hsien). Wade–Giles distinguishes aspirated from unaspirated consonants with a Greek asper (‘), which is sometimes replaced by an opening quote or an apostrophe, and is often omitted in popular writing; Pinyin uses different letters. Wade–Giles uses ü more often than Pinyin, which requires it only in the syllables lü and nü; only Wade–Giles uses ê (e.g. jên = Pinyin ren) and ŭ (ssŭ = Pinyin si). Neither consistently indicates the syllabic tone, despite its importance; when they do so, Wade–Giles writes a superior figure after the syllable (i1 i2 i3 i4), Pinyin an accent on the vowel (yī yí yǐ yì; note the need to combine these with the umlaut).

12.4 Dutch and Afrikaans

12.4.1 Introduction

Dutch is the language of the Netherlands. The Dutch spoken in northern Belgium, formerly called Flemish, is now officially called Dutch (Nederlands in Dutch). Afrikaans is one of the official languages of South Africa, and was derived from the Dutch brought to the Cape by settlers in the seventeenth century.

12.4.2 Dutch

Alphabet

The alphabet is the same as English, but q and x are used only in foreign loanwords. In dictionaries ij precedes ik; in directories and encyclopedias it is sometimes treated as equivalent to y. The apostrophe occurs in such plurals as pagina’s (‘pages’), but not before s in the genitive.

Accents

The acute is used to distinguish één (‘one’) from een (‘a’), and vóór (‘before’) from voor (‘for’). The only other accent required—except in foreign loanwords—is the diaeresis:

| knieën ‘knees’ | provinciën ‘provinces’ | zeeën ‘seas’ |

Punctuation and capitalization

Punctuation is less strict than in, for example, German. Capitals are used for the pronouns U ‘you’ and Uw ‘your’, for terms indicating nationality (Engelsman ‘Englishman’, Engels ‘English’), and for adjectives derived from proper nouns, but not for days or months; in institutional names capitalize all words except prepositions and articles.

The abbreviated forms of des and het (’s and ’t respectively) take a space on either side except in the case of towns and cities, where a hyphen follows: ’s-Gravenhage. When a word beginning with an apostrophe starts a sentence, it is the following word that takes the capital: ’t Is.

Word division

Do not divide the suffixes -aard, -aardig, -achtig, and any beginning with a consonant. This applies to the diminutive suffix -je, but note that a preceding t may itself be part of the suffix: kaart-je (‘ticket’), but paar-tje (‘couple’).

Take over single consonants; the combinations ch, sj, tj (which represent single sounds) and sch; and consonant + l or r in loanwords. Take over the second of two consonants (including the g of ng and the t of st); when more than three come together take over those combinations that may begin a word. Do not divide double vowels or ei, eu, ie, oe, ui, aai, eei, ieu, oei, ooi.

12.4.3 Afrikaans

Alphabet, accents, and spelling

There is no ij in Afrikaans, у being used as in older Dutch; s is used at the start of words where Dutch has z, and w between vowels often where Dutch has v.

The circumflex is quite frequent; the grave is used on paired conjunctions (òf … òf, ‘either … or’) and a few other words. The acute is found in the demonstrative dié to distinguish it from the article die, and in certain proper nouns and French loan-words. There is no diaeresis with ae (dae ‘days’).

Capitalization

As in Dutch, when a word beginning with an apostrophe starts a sentence in Afrikaans, the following word is capitalized. This rule is important, since the indefinite article is written ’n:’n Man het gekom, ‘A man has come’

12.5 French

12.5.1 Accents

The acute (΄), the most common accent in French, is used only over e; when two e’s come together the first always has an acute accent, as in née. The grave (`) is used mainly over e, but also on final a, as in voilà, and on u in où (‘where’), but not ou (‘or’). The circumflex (ˆ) may be used over a, e, i, o, and u. The cedilla c (ç) is used only before a, o, and u. The diaeresis (¨) is found on i, e, and y.

Although they are recommended by the Académie française, accents on capital letters are often omitted in everyday French, except when they are needed to avoid confusion:

POLICIER TUÉ ‘Policeman killed’

POLICIER TUE ‘Policeman kills’

12.5.2 Orthographic reform

Les Rectifications de l’orthographie, drafted by the Conseil Supérieure de la Langue Française, was published in 1990. It is a controversial document and ignored by many. From an editor’s point of view the main changes are those affecting circumflex accents and hyphens. Since the document recommends the removal of the circumflex on і and u, except in verb endings and a few words where it distinguishes meaning, the lack of this accent may indicate the author’s support for the reform, and it would be wise to ascertain whether or not this is the case; if this is not possible, assume that the reforms are not being followed.

12.5.3 Abbreviations

As in English, place a full point after an abbreviation (chap., ex.) but not after a contraction (St, Mlle). Retain the hyphen when a hyphenated form is abbreviated:

J.-J. Rousseau (Jean-Jacques Rousseau)

P.-S. (post-scriptum)

Some common examples of abbreviations in French:

| abrév. | abréviation |

| apr. | après |

| av. | avant |

| c.-à-d. | c’est-à-dire |

| chap. | chapitre |

| Cie, Cie | compagnie |

| conf. | confer (Lat.) |

| d° | dito |

| Dr | docteur |

| éd. | édition |

| etc. | et cætera |

| ex. | exemple |

| f° | folio |

| Ier, Ier | premier |

| IIe, 2e, II ème, 2ème | deuxième |

| ill. | illustration |

| in-4° | in-quarto |

| in-8° | in-octavo |

| inéd. | inédit |

| in-f° | in-folio |

| in pl. | in plano (Lat.) |

| l.c. | loc. cit. (Lat.) |

| liv. | livre |

| M. | monsieur |

| Me, Me | maître |

| Mlle, Mlle | mademoiselle |

| MM. | messieurs |

| Mme, Mme | madame |

| ms. | manuscrit |

| mss. | manuscrits |

| n° | numéro |

| Ρ· | page |

| p., pp. | pages |

| P.-S. | post-scriptum |

| qqch | quelque chose |

| qqn | quelqu’un |

| s., ss., suiv. | suivant |

| s.d. | sans date |

| s.l. | sans lieu |

| t. | tome |

| TVA | taxe à la valeur ajoutée |

| v. | voyez, voir |

| Vve | veuve |

12.5.4 Capitalization

Capitalize only the first element (or first element after the article) in compound proper names. If the first element has a following adjective linked by a hyphen, capitalize the adjective also:

| l’Académie française | la Comédie-Française |

| le Palais-Royal | la Légion d’honneur |

| le Conservatoire de musique | Bibliothèque nationale |

Note that a following adjective is lower case, while an adjective preceding the noun is capitalized:

| Le Nouveau Testament | les Saintes écritures |

| l’Écriture sainte |

Use lower-case letters for: days of the week; names of months; the cardinal points (le nord, le sud, etc.); languages; adjectives derived from proper nouns (la langue française); ranks, titles, regimes, religions, adherents of movements, and their derivative adjectives (calvinisme, chrétien(ne), le christianisme, humaniste, les sans-culottes, le socialisme, les socialistes).

Use capitals for nationalities when used as nouns: le Français (‘the Frenchman’), la Française (‘the Frenchwoman’), as opposed to le français (‘French’) (the language). Note that when referring to an adherent of Judaism un juif should be lower-case like un chrétien and un musulman, but capitalized as a member of a people: un Juif like un Turc and un Arabe. In practice, the capital seems to be used more widely.

In names for geographical features common nouns such as mer (‘sea’) are lower case, but there are traditional exceptions:

| le Bassin parisien | le Massif central | le Massif armoricain |

| la Montagne Noire | le Quartier latin |

12.5.5 Punctuation

Hyphen

Use hyphens to connect cardinal and ordinal numbers in words under 100:

| vingt-quatre | trois cent quatre-vingt-dix |

but when et joins two numbers no hyphen is used:

| vingt et un | cinquante et un | vingt et unième |

Quotation marks

Texts set wholly in French should use quotation marks called guillemets (« »); these need not be used for French text in English-language books. A space is inserted inside the guillemets, separating the marks from the matter they contain; prefer a thin or no-break space (see 2.5.1) to avoid awkward line breaks but a normal word space is acceptable.

A guillemet is repeated at the head of every subsequent paragraph belonging to the quotation. In conversational matter guillemets are sometimes put at the beginning and end of the remarks, and the individual utterances are denoted by a spaced dash:

« — Nous allons lui écrire, dis-je, et lui demander pardon.

— C’est une idée de génie. »

Many modern authors dispense with guillemets altogether, and denote the speakers by a dash only, although this is officially frowned upon.

English-style inverted commas are often used to mark a quotation within a quotation.

Where guillemets are used, only one » appears at the end of two quotations concluding simultaneously.

12.5.6 Work titles

Capitalize the initial letter of the first word of a title and of a following noun, if the first word is a definite article:

| Les Femmes savantes | Au revoir les enfants |

Where the title occurs within a sentence, a lower-case l for the definite article (le, la, les) beginning a title may be used; the article is construed with the surrounding sentence:

La mise en scène de la Bohème ‘The production of La Bohème’

If a noun following an initial definite article is itself preceded by an adjective, capitalize this also:

| Le Petit Prince | Les Mille et Une Nuits (two adjectives) |

but downcase any following adjective:

Les Mains sales

If the title begins with any word other than le, la, les, or if the title forms a complete sentence, downcase the words following, unless they are proper nouns:

Une vie

A la recherche du temps perdu

La guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu

Les dieux ont soif

A parallel title is treated as a title in its own right for the purposes of capitalization:

Emile, ou, De l’éducation

As these rules are complex, some English styles merely capitalize the first word and any proper nouns.

12.5.7 Word division

Divide words according to spoken syllables, and in only a few cases according to etymology. A single consonant always goes with the following vowel (amou-reux, cama-rade); ch, dh, gn, ph, th, and groups consisting of consonant + r or + l count as single consonants for this purpose.

Other groups of consonants are divided irrespective of etymology (circons-tance, tran-saction, obs-curité) but divide a prefix from a following h (dés-habille). Always divide ll, even if sounded y: travaillons, mouil-lé. Do not divide between vowels except in a compound: anti-aérien, extra-ordinaire (but Moa-bite). In particular, vowels forming a single syllable (monsieur) are indivisible. Do not divide after a single letter (émettre) or before or after an intervocalic x or y (soixante, moyen, Alexandre), but divide after x or y if followed by a consonant: dex-térité, pay-san. Do not divide abbreviated words (Mlle), within initials (la CRS), or after an abbreviated forename (J.-Ph. Rameau) or personal title (le Dr Suchet).

Do not divide after an apostrophe within compound words (presqu’île, aujour-d’hui). Divide interrogative verb forms before -t-: Viendra-|t-il?

12.5.8 Numerals

Use words for times of day if they are expressed in hours and fractions of hour:

| six heures ‘six o’clock’ | trois heures et quart ‘a quarter past three’ |

but use figures for time expressed in minutes: 6 h 15, 10 h 8 min 30 s.

Set Roman numerals indicating centuries in small capitals:

| le XIème siècle | XIe siècle |

but they should be in full capitals when in italic.

Use upper-case Roman numerals for numbers belonging to proper nouns (Louis XIV), but Arabic numerals for the numbers of the arrondissements of Paris: le 16e arrondissement.

In figures use thin spaces to divide thousands (20 250), but do not space dates, or numbers in general contexts (ľan 1466, page 1250).

Times of day written as figures should be spaced as 10 h 15 min 10 s (10 hrs 15 min. 10 sec.); formerly this was also printed 10h 15m 10s.

12.6 Gaelic

12.6.1 Alphabet and accents

Both Irish and Scots Gaelic are written in an eighteen-letter alphabet with no j, k, q, v, w, x, y, z (except in some modern loanwords); in Irish the lower-case і is sometimes left undotted. Until the middle of the twentieth century Irish (but not Scots Gaelic) was often written and printed in insular script, a medieval form of Latin handwriting, in which a dot was marked over aspirated consonants. In Roman script aspirated consonants are indicated by the addition of h after the letter, in both Irish and Scots Gaelic (Irish an chos ‘the foot’, Scots Gaelic a’ chas). Irish marks vowel length with an acute accent (á, é, í, ó, ú), Scots Gaelic with the grave (à, è, ì, ò, ù). Apostrophes are frequent in Scots Gaelic, less so in Irish.

12.6.2 Mutations

In Irish Gaelic, as in Scots Gaelic and Welsh, initial consonants are replaced by others in certain grammatical contexts, in a process called mutation. In Irish the mutation known as eclipsis is indicated by writing the sound actually pronounced before the consonant modified: mb, gc, nd, bhf, ng, bp, dt. If the noun is a proper name, it retains its capital, the prefixed letter(s) being lower case:

i mBaile Átha Cliath ‘in Dublin’ (Baile Átha Cliath = Dublin)

na bhFrancach ‘of the French’

The same combination of initial lower-case letter followed by a capital occurs when h or n is prefixed to a name beginning with a vowel— go hÉirinn ‘to Ireland’, Tír na nÓg ‘the Land of the Young’—or t is prefixed to a vowel or S: an tAigéan Atlantach ‘the Atlantic Ocean’, an tSionnain ‘Shannon’. Before lower-case vowels, h is prefixed directly (na hoíche ‘of the night’), as is t before s (an tsráid ‘the street’), but n and t take a hyphen before a vowel (in-áit ‘in a place’, an t-uisce ‘the water’). Except in dialects, eclipsis is not found with consonants in Scots Gaelic.

Prefixed h-, n-, and t- always take a hyphen:

| an t-sràid ‘the street’ | Ar n-Athair ‘Our Father’ |

| na h-oidhche ‘of the night’ | na h-Eileanan an Iar ‘the Western Isles’ |

12.7 German

12.7.1 Accents and special sorts

German uses the diacritics Ä, Ö, Ü, ä, ö, ü, and the special sort Eszett (ß) (see 12.7.2): Eszett differs from a Greek beta (β), which should not be substituted for it.

12.7.2 Orthographic reform

A new orthography agreed by the German-speaking countries came into force on 1 August 1998. The seven-year transitional period, during which both systems were official, ended on 31 July 2005, and the older orthographic forms are now considered incorrect, although they are still widely used. The reform’s main tendency is to eliminate irregularities that caused difficulty for the native speaker. At the same time, more variations are permitted than under the old rules, though these options are restricted: it is not acceptable to mix and match old and new spellings at will.

Under the new orthography, certain words were adjusted to resemble related words, so that, for instance, the verbs numerieren and plazieren become nummerieren and platzieren to coincide with the related nouns Nummer (‘number’) and Platz (‘place’).

In verbal compounds, nouns and adjectives regarded as retaining their normal functions are written separately:

irreführen (‘to mislead’) and wahrsagen (‘to predict’)

but

radfahren → Rad fahren ‘to ride a bicycle’

Long-established loanwords have been Germanized (Tip → Tipp, ‘tip’), and ее substituted for é in such words as Varietee for Varieté (‘music hall’).

The optional use of f for ph is extended: Delfin (‘dolphin’), Orthografie (‘orthography’), but not to words deemed more learned: Philosophie (‘philosophy’), Physik (‘physics’).

The Eszett was traditionally used in place of a double s at the end of a syllable, before a consonant (whatever the vowel), and after long vowels and diphthongs. The new rules allow the ß only after a long vowel (including ie) or diphthong:

Fuß, Füße ‘foot, feet’

after a short vowel ss is to be used:

Kuss, Küsse ‘kiss, kisses’

but:

ihr esst, ihr aßt ‘you [pl.] eat, ate’

wir essen, wir aßen ‘we eat, ate’

The Eszett is considered an archaism in Swiss German, ss being preferred in all circumstances. No corresponding capital and small capital letters exist for ß, and SS and ss are used instead; in alphabetical order ß counts as ss and not sz.

In the absence of specific instructions to the contrary, or of evidence from the nature of the text itself, the new rules should be applied in all matter not by native speakers of German. Quotations from matter published in the old spelling should follow the old style (except in respect of word division), but new editions will normally modernize.

The new orthography’s effects in other areas are mentioned under the headings below.

12.7.3 Abbreviations

Use a full point:

d. h. (das heißt, ‘that is’)

Dr. (Doktor, ‘Dr’)

Prof. (Professor, ‘Prof.’)

usw. (und so weiter, ‘and so on’)

z. В. (zum Beispiel, ‘for example’)

Montag, den 12. August ‘Monday, 12 August’

der 2. Weltkrieg (der Zweite Weltkrieg, ‘the Second World War’)

Do not use points in abbreviations that are pronounced as such:

DM (die Deutsche Mark, ‘the German mark’)

KG (Kommanditgesellschaft, ‘limited partnership’)

Some common examples of abbreviations in German:

| a. a. O. | am angeführten Ort |

| Abb. | Abbildung |

| Abt. | Abteilung |

| Anm. | Anmerkung |

| Aufl. | Auflage |

| Ausg. | Ausgabe |

| Bd., Bde. | Band, Bände |

| bes. | besonders |

| bzw. | beziehungsweise |

| d. h. | das heißt |

| d. i. | das ist |

| ebd. | ebenda, ebendaselbst |

| Erg. Bd. | Ergänzungsband |

| etw. | etwas |

| Hft. | Heft |

| hrsg. | herausgegeben |

| Hs., Hss. | Handschrift, Handschriften |

| Lfg. | Lieferung |

| m. E. | meines Erachtens |

| m. W. | meines Wissens |

| Nr. | Nummer |

| o. | oben |

| o. Ä. | oder Ähnliche(s) |

| o. O. | ohne Ort |

| R. | Reihe |

| s. | siehe |

| S. | Seite |

| s. a. | siehe auch |

| s. o. | siehe oben |

| sog. | sogenannt |

| s. u. | siehe unten |

| u. a. | unter anderem |

| u. ä. | und ähnliches |

| usf., u. s. f. | und so fort |

| usw., u. s. w. | und so weiter |

| verb. | verbessert |

| Verf., Vf. | Verfasser |

| vgl. | vergleiche |

| z. B. | zum Beispiel |

| z. T. | zum Teil |

12.7.4 Capitalization

All nouns in German are written with initial capital letters, as are other words (adjectives, numerals, and infinitives) that are used as nouns:

Gutes und Böses ‘good and evil’

Die Drei ist eine heilige Zahl ‘Three is a sacred number’

The basic rule of capitalizing nouns remains untouched by the orthographic reform, but whereas all nouns used as adverbs were previously lower case, some changes have been implemented: for example, heute abend (‘tonight’) is now heute Abend, morgen abend (‘tomorrow evening’) becomes morgen Abend, and gestern morgen (‘yesterday morning’) becomes gestern Morgen.

Adjectives used as nouns are capitalized with fewer exceptions than before: alles übrige becomes alles Übrige (‘everything else’).

In the new rules the familiar forms of the second person pronouns du, dich, dir, dein, ihr, euch, euer are not (as they formerly were) capitalized in letters and the like. The old rule remains that pronouns given a special sense in polite address are capitalized to distinguish them from their normal value: these are (in medieval and Swiss contexts) Ihr addressed to a single person; (in early modern contexts) Er and Sie (feminine singular); and (nowadays) Sie (plural). In all of the above the capital is used also in the oblique cases and in the possessive, but not in the reflexive sich.

Capitalize adjectives that form part of a geographical name (or are formed from a place name), the names of historic events or eras, monuments, institutions, titles, special days and feast days. Otherwise do not capitalize adjectives denoting nationality:

das deutsche Volk ‘the German nation’

or the names of languages in expressions where their use is considered adverbial:

italienisch sprechen ‘to speak Italian’

Traditionally, adjectives derived from personal names were capitalized in certain contexts, but according to the new rules all adjectives derived from personal names are to be lower case, except when the name is marked off with an apostrophe:

das ohmsche Gesetz or das Ohm’sche Gesetz ‘Ohm’s Law’

In work titles the first word and all nouns are capitalized, with all other words having a lower-case initial.

12.7.5 Punctuation

There are very specific rules about the placing of commas in German. Do not interfere in the punctuation of quoted matter without reference to the author or the source.

Sentences containing an imperative normally end in an exclamation mark. The traditional practice of ending the salutation in a letter with an exclamation mark—Sehr geehrter Herr Schmidt! (‘Dear Herr Schmidt’)—has largely given way to the use of a comma, after which the letter proper does not begin with a capital unless one is otherwise required.

German rarely employs the en rule in compounds in the way that it is used in English, preferring a hyphen between words:

die Berlin-Bagdad-Eisenbahn ‘the Berlin–Baghdad railway’

The en rule is used for page and date ranges (S.348–349, 1749–1832): do not elide such ranges. It is also used, with a word space on each side, as a dash.

Quotation marks

German quotation marks (Anführungszeichen) take the form of two commas at the beginning of the quotation, and two opening quotation marks (turned commas) at the end („“), or reversed guillemets are used (»…«). Mark quotations within quotations by a single comma at the beginning and a single opening quotation mark at the end (, ‘). No space separates the quotation marks from the quotation.

Expect a colon to introduce direct speech. Commas following a quotation fall after the closing quotation mark, but full points go inside if they belong to the quotation.

Apostrophe

The apostrophe is used to mark the elision of e to render colloquial usage:

Wie geht’s? ‘How are things?’/‘How are you?’

When the apostrophe occurs at the beginning of a sentence, the following letter does not become a capital:

’s brennt! ‘Fire!’ (not ’S brennt)

The apostrophe is also used to mark the suppression of the possessive s (for reasons of euphony) after names ending in s, ß, x, z:

| Aristoteles’ Werke | Horaz’ Oden |

Hyphen

Traditionally, a noun after a hyphen begins with an initial capital:

das Schiller-Museum ‘the Schiller Museum’

but the new orthography allows words to be run together:

das Schillermuseum

The hyphen was used to avoid the double repetition of a vowel (Kaffee-Ersatz, ‘coffee substitute’) but not to avoid the similar repetition of a consonant (stickstofffrei, ‘nitrogen-free’). The new rules no longer require a hyphen—groups of three identical consonants are written out even before a vowel and when sss results from the abolition of β after a short vowel:

| Brennnessel | Schifffahrt |

| Schlußsatz → Schlusssatz | |

It is permissible to make such compounds clearer by using a hyphen:

| Brenn-Nessel | Schiff-Fahrt | Schluss-Satz |

12.7.6 Word division

For the purpose of division, distinguish between simple and compound words.

Simple words

Do not divide words of one syllable. Divide other simple words by syllables, either between consonants or after a vowel followed by a single consonant. This applies even to x and mute h: Bo-xer, verge-hen.

Do not separate ch, ph, sch, ß, and th (representing single sounds). Correct examples are spre-chen, wa-schen, So-phie, ka-tholisch, wech-seln, Wechs-ler. Traditionally st was included in this group, but under the new rules it is no longer, and should be divided: Las-ten, Meis-ter, Fens-ter.

At the ends of lines, take over ß: hei-ßen, genie-ßen.

Take over as an entity ss if used instead of ß, but divide ss when it is not standing for ß: las-sen.

Traditionally, if a word was broken at the combination ck it was represented as though spelled with kk: Zucker but Zuk-ker, Glocken but Glok-ken. According to the new orthography, the combination ck is taken over whole, as it was traditionally after a consonant in proper nouns or their derivatives: Zu-cker, Glo-cken, Fran-cke, bismar-ckisch.

Treat words with suffixes as simple words and divide in accordance with the rules above: Bäcke-rei, le-bend, Liefe-rung.

Compound words

Divide a compound word by its etymological constituents (Bildungs-roman, Kriminal-polizei, strom-auf) or within one of its elements: Bundes-tag or Bun-destag. Divide prefixes from the root word: be-klagen, emp-fehlen, er-obern, aus-trinken.

12.7.7 Numerals

Separate numbers of more than four figures with thin spaces by thousands: 6 580 340.

A full point after a numeral shows that it represents an ordinal number:

14. Auflage (14th edition)

Mittwoch, den 19. Juli 1995 (Wednesday, 19 July 1995)

The full point also marks the separation of hours from minutes: 14.30 Uhr or 1430 Uhr.

Germans use Roman numerals rarely: even when citing Roman page numbers, they often convert them into Arabic and add an asterisk: S. 78* (p. lxxviii). Distinguish this from 1*, denoting the first page of an article that is in fact (say) the third or fifth page of a pamphlet.

12.7.8 Historical and specialist setting

The traditional black-letter German types such as Fraktur and Schwabacher were replaced by the Roman Antiqua in 1941. They are now found only to a limited extent in German-speaking countries, mostly in decorative or historical contexts, or in approximating earlier typography. Any matter to be set in them should be deemed a quotation. Word division should follow the pre-1998 rules, not the new; in particular the st ligature should be taken over. The long s ( ) in Fraktur type is used at the beginnings of words, and within them except at the ends of syllables. The short final s (

) in Fraktur type is used at the beginnings of words, and within them except at the ends of syllables. The short final s ( ) is generally put at the ends of syllables and words, except before p (Knospe).

) is generally put at the ends of syllables and words, except before p (Knospe).

Table 12.2 German Fraktur alphabet

12.8 Greek

12.8.1 Introduction

Ancient and modern Greek show a remarkable similarity, and much of what follows covers both. Modern Greek may be divided into two forms, katharevousa (literally ‘purified’), a heavily archaized form used in technical and Church contexts, written in polytonic script, and demotic, the form which is spoken and used in everyday contexts. Demotic, which uses monotonic orthography, has been the official form since 1976, and is employed in official documents.

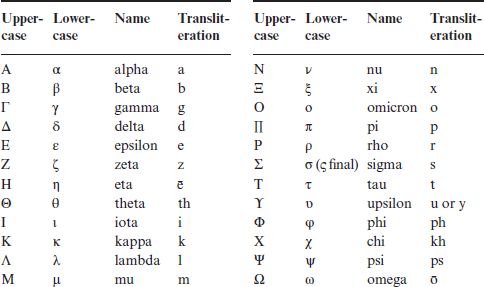

12.8.2 Alphabet

Ancient and modern Greek are written in an alphabet that consists of twenty-four letters: seventeen consonants and seven vowels (α, ε, η, ι, ο, υ, ω). Modern Greek is written from left to right, as was ancient Greek from the classical period onwards.

In ancient Greek the ‘final’ sigma (i.e. the form used at the end of words) must be distinguished from ϛ stigma [sic], which was used for the numeral 6 and in late manuscripts and early printed books for στ. Stigma is also used in scholarly work (especially on Latin authors) to denote ‘late manuscripts’. In papyri and inscriptions sigma is normally printed Ϲ ϲ (‘lunate sigma’), with no separate final form; this is also sometimes used in other ancient contexts, but never in modern Greek.

Table 12.3 Greek alphabet

Texts of early inscriptions may require Latin h (to be italic with a sloping fount), and the letters Ϝ (wau or digamma) and ϙ (koppa).

In ancient Greek an iota forming a ‘long diphthong’ with a preceding α, η, or ω is traditionally inserted underneath the vowel: ᾳ ῃ ῳ (‘iota subscript’). Some modern scholars prefer to write αι, ηι, ωι (‘adscript iota’), in which case accents and breathings should be set on the first vowel; in the case of αι this means that the accent may fall on either letter depending on the pronunciation. When a word is set in capitals, iota is always adscript (i.e. written on the line rather than beneath it); when the word has an initial capital but is otherwise lower case, an initial long diphthong will have the main vowel as capital, the iota adscript lower case; hence ᾧ will become ΩΙ in capitals (for the absence of accent and breathing see below), but  at the start of a paragraph. In modern Greek the iota is omitted even in phrases taken bodily from the ancient language.

at the start of a paragraph. In modern Greek the iota is omitted even in phrases taken bodily from the ancient language.

12.8.3 Transliteration

Whether or not to transliterate ancient or modern Greek must of course depend on the context. In general contexts any use of Greek script will be very off-putting to the majority of people, but readers who know Greek will find it far harder to understand more than a few words in transliteration than in the Greek alphabet. If the work is intended only for specialists, all Greek should be in the Greek alphabet; in works aimed more at ordinary readers, individual words or short phrases should be transliterated:

history comes from the Greek word historiē

although longer extracts should remain in Greek script, with a translation. Table 12.3 shows how Greek letters are usually transliterated.

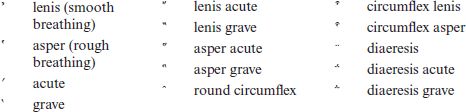

12.8.4 Accents

The accents in ancient and modern Greek are acute ´, used on any of the last three syllables of a word; grave ` used only on final syllables; circumflex ˆ, used on either of the last two syllables of a word. The diaeresis ¨ is also used, to show that two vowels occurring together do not form a diphthong.

All words of three or more syllables, and most others, carry an accent. Most unaccented words cause the majority of preceding words to take an acute on their final syllable; they are known as enclitics, the others (all monosyllables) as proclitics. An acute accent on a final syllable or a monosyllable will be found before an enclitic, before punctuation, and in the two words τίϛ and τί when they mean ‘who?’ and ‘what?’; otherwise it is replaced by a grave, although in modern Greek it is sometimes retained.

Greek uses marks known as breathings to indicate the presence or absence of an aspirate at the beginning of a word: they are ‘ (asper or rough breathing) and ’ (lenis or smooth breathing). Breathings are used on all words beginning with a vowel or diphthong and also with ρ; in this case, and that of υ and υι, the breathing will nearly always be the asper.

Table 12.4 Greek accents

Each of the accents may be combined with either breathing or with the diaeresis; but breathing and diaeresis never stand on the same letter. The accent always stands over the diaeresis; the breathing stands to the left of the acute or grave, but underneath the circumflex. Except in the case of long diphthongs (see above), accents are placed over the second vowel of a diphthong (which is always ι or υ).

Accents and breathings are regularly used when words are set in capital and lower-case style; they precede capitals and are set over lower-case letters. They are omitted when words are set wholly in capitals.

In modern Greek many printers now dispense with breathings and use only a single accent, either a small downward-pointing filled-in triangle or simply the acute; as before, the accent is omitted in capitals, but otherwise precedes capitals and stands over lower-case letters. Monosyllables, even if stressed, do not have an accent, save that ὴ ‘or’ is distinguished from η ‘the’ (nominative singular feminine), in traditional spelling ἤ and ἡ respectively. The diaeresis remains in use; however, it is used to show that ᾳ ï and οï are diphthongs, as opposed to the digraphs αι (pronounced ε) and οι (pronounced ι).

In both ancient and modern Greek a final vowel or diphthong may be replaced at the end of a word by an apostrophe when the next word begins with a vowel or diphthong; occasionally it is the latter that is replaced. Traditionally setters have represented the apostrophe by a lenis; but if the font has a dedicated apostrophe that should be used. Do not set an elided word close up with the word following. It may be set at the end of a line even if it contains only one consonant and the apostrophe or lenis.

12.8.5 Capitalization and punctuation

In printing ancient Greek, the first word of a sentence or a line of verse is capitalized only at the beginning of a paragraph. In modern Greek, capitals are used for new sentences, though not always for new lines of verse.

For titles of works in ancient Greek, it is best to capitalize only the first word and proper nouns, or else proper nouns only. In modern Greek the first and main words tend to be capitalized; first word and proper nouns only is the rule in bibliographies.

In ancient Greek, it is conventional to capitalize adjectives and adverbs derived from proper nouns, but not verbs:

Ἕλλην ‘a Greek’

Ἑλληνιστί ‘in Greek’

but

ἑλληνίfω ‘I speak Greek/behave like a Greek’

In modern Greek, lower case is the rule:

ελληνικὸϛ ‘Greek (adj.)’

ελληνικὰ ‘in Greek’

The comma, the full point, and the exclamation mark (in modern Greek) are the same as in English; but the question mark (;) is the English semicolon (italic where necessary to match a sloping Greek font), and the colon is a raised full point (·). Use double quotation marks, or in modern Greek guillemets.

12.8.6 Word division

In ancient Greek the overriding precept should be that of breaking after prefixes and before suffixes and between the elements of compound words. This requires knowledge of the language, however, since many prefixes cannot be distinguished at sight: ἔν-αυε ‘lit’ contains a prefix, ἔναιε ‘dwelt’ does not.

A vowel may be divided from another (λʿ-ων) unless they form a diphthong (αι, αυ, ει, ευ, ηυ, οι, ου, υι). Take over any combination of ‘mute’ (β, γ, δ, θ, κ, π, τ, ϕ, χ) followed by ‘liquid’ (λ, μ, ν, ρ), also β δ, γ δ, κτ, πτ, ϕθ, χθ, or any of these followed by ρ; μν; and σ followed by a consonant other than σ or by one of the above groups: ἑλι-κτός, γι-γνά-σκω, μι-μνή-σκω, κα-πνός, βα-πτί-fω.

Any doubled consonants maybe divided; λ, μ, ν, and ρ maybe divided from a following consonant, except in μν. Divide γ from a following κ or χ; take over ξ and ψ between vowels (δεί-ξειν, ἀνε-ψιός).

Modern Greek word division follows ancient principles, but the consonant groups taken over are those that can begin a modern word. Therefore θμ is divided, but γκ, μπ, ντ, τf, τσ are not.

12.8.7 Numerals

Two systems of numerals were in use in ancient Greek. In the older system (the ‘acrophonic’ system, used only for cardinal numbers), certain numbers were indicated by their initial letters. This was eventually replaced by the alphabetic system, shown in Table 12.5, which could be used of either cardinals or ordinals. The Greek numeral sign (ʹ) is used to denotes numbers; the Greek lower numeral sign (͵) signifies thousands. The symbols ϛ and 03E1, are known as ‘stigma’ and ‘sampi’ respectively.

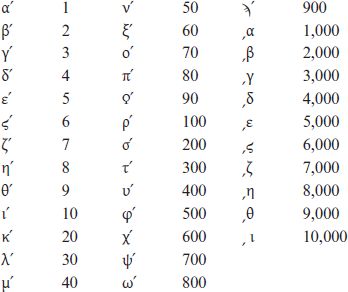

Table 12.5 Alphabetic Greek numbers.

Modern Greek uses Arabic numerals: if a sloping font is being used they should be set in italic, but with upright fonts they should be set in roman, in both cases ranging. Alphabetic numerals are still employed, however, in much the same way as Roman numerals are in Western languages; vi is commonly written στ ́.

12.9 Hebrew

12.9.1 Alphabet

The Hebrew alphabet consists exclusively of consonantal letters. Vowels may be indicated by dots or small strokes (‘points’) above, below, or inside them, but Hebrew is generally written and printed without vowels. Hebrew written without vowels is described in English as ‘unpointed’ or ‘unvocalized’.

Each letter has a numerical value. Letters are therefore often used in Hebrew books—especially in liturgical texts and older works—to indicate the numbers of volumes, parts, chapters, and pages. Letters are also used to indicate the day of the week, the date in the month, and the year according to the Jewish calendar.

The consonantal letters are principally found in two different forms: a cursive script, and the block (‘square’) letters used in printing.

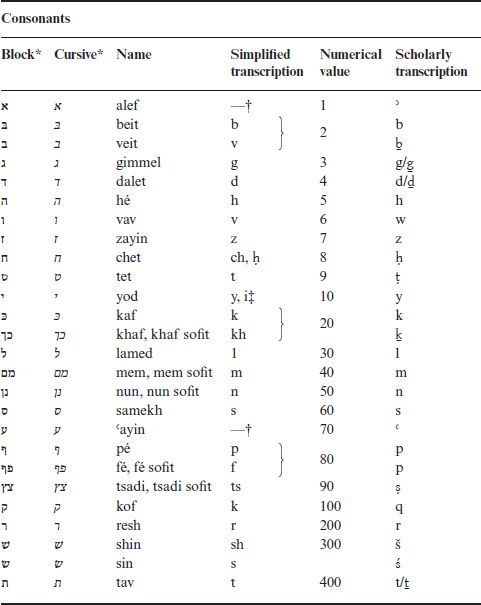

Table 12.6 Hebrew alphabet

| Vowels | |

|---|---|

| Form | Name |

| ָ | kamats |

| ַ | patah |

| ֶ | segol |

| ֵ | tseré |

| ִ | hirik |

| ְ | sheva |

| ֻ | kubutz |

| ֲ | hataf patah |

| ֱ | hataf segol |

| וֹ | holam |

| וּ | shuruk |

* Where two forms are given, the second is that used in final position.

† The letters alef and ʿayin are not transliterated in the simplified system. Where they occur in intervocalic position an apostrophe is used to indicate that the vowels are to be pronounced separately.

‡ Transliterated ‘y’ as a consonant, ‘i’ as a vowel.

12.9.2 Transliteration

Different systems of transliterated Hebrew may require the following diacritics: ś (and sometimes the acute is also used on vowels to indicate stress); ā, ē, ī, ō, ū; ê, î, ô, û; ă, ĕ, ŏ (in some systems represented by superiors, a e o); ḥ, ṣ, ṭ, ẓ (in older system also ḳ for q); š; ḇ, ḏ, ʿ, ḵ, ʿ, ṯ (less strictly bh, dh, gh, kh, ph, th). Special characters are schwa ə, aleph ʾ, ʿayin ʿ; in loose transliteration from modern Hebrew the latter two may be replaced by an apostrophe or omitted altogether.

12.9.3 Word division

In Hebrew script, words are short enough not to need dividing; transliterated words should be so divided that the new line begins with a single consonant. In loose transliteration, ts and combinations with h may or may not represent single consonants; when in doubt avoid dividing.

12.10 Italian

12.10.1 Accents

The use of accents in the Italian language is not entirely consistent; editors should as a general rule follow the author’s typescript. There are two accents, acute and grave. The acute accent is used on a ‘closed’ e and very rarely on a closed o: perché, ‘because’, né… né… ‘neither…nor…’. The grave accent is used on the ‘open’ e and o: è, ‘is’, cioè, ‘that is’, però, but’, ‘however’. The grave is also used to indicate stress on a final syllable. An alternative convention does exist for і and u, whereby they are marked with an acute accent: così and cosí (‘so’), più and piú (‘more’). However, in normal, standard Italian it is considered good practice to use the grave accent on all vowels except the closed e and, very rarely, o.

The appearance in a single text of Italian extracts with several different systems of accentuation may indicate not ignorance or carelessness in the author, but rather scrupulous fidelity to sources. Any discretional accents should be left alone unless the copy-editor is expert in the language and the author is not. There are other respects in which Italian spelling is even now less regulated than, say, French, and zeal for consistency must be tempered by either knowledge or discretion.

Leave capital letters unaccented as a general rule, unless an accent is needed to avoid confusion. The grave accent on an upper-case E is marked as an apostrophe:

E’ oggi il suo compleanno ‘It is his birthday today’

12.10.2 Abbreviation

Italian abbreviations are usually set with an initial capital only rather than in full capitals, with no full point following: An (Alleanza Nazionale), Rai (Radiotelevisione Italiana). When the expansion does not begin with a capital, neither does the abbreviation: tv (televisione).

12.10.3 Capitalization

Italian uses capital letters much less frequently than English. Capitalize names of people, places, and institutions, and some dates and festivals. Use lower-case for ίο (Ι), unless it begins a sentence. Lei, Loro, and Voi (polite forms of ‘you’) and related pronouns and adjectives, La, Le, Suo, Vi, Vostro, are often capitalized, especially in commercial correspondence:

La ringraziamo per la Sua lettera ‘Thank you for your letter’

Note that polite La and Le may be capitalized even when suffixed to a verb: ringraziarLa ‘thank you’.

When citing titles of works capitalize only the first word and proper nouns:

| Il gattopardo | La vita è bella |

Roman numerals indicating centuries are generally put in full capitals in both italic and roman:

l’XI secolo ‘the eleventh century’

Parlo inglese e francese ‘I speak English and French’

Gli italiani ‘the Italians’

un paese africano ‘an African country’

12.10.4 Punctuation

Italian makes a distinction between points of omission (which are spaced) and points of suspension (which are unspaced). The latter equate with the French points de suspension, three points being used where preceded by other punctuation, four in the absence of other punctuation.

Put the ordinary interword space after an apostrophe following a vowel: a’ miei, ne’ righi, po’ duro, de’ Medici. Insert no space after an apostrophe following a consonant: l’onda, s’allontana, senz’altro. When an apostrophe replaces a vowel at the beginning of a word a space always precedes it: e ’l, su ’l, te ’l, che ’l. Note, however, that in older printing these rules may be reversed: a’miei, l’ onda, e’l.

Single and double quotation marks, and guillemets, are all used in varying combinations. A final full point is placed after the closing quotation marks even if a question mark or exclamation mark closes the matter quoted:

«Buon giorno, molto reverendo zio!». ‘Good day, most reverend Uncle!’

12.10.5 Word division

Do not divide the following compound consonants:

Divide between vowels only if neither is і or u. When a vowel is followed by a doubled consonant, including cq, the first of these goes with the vowel, and the second is joined to the next syllable: lab-bro, mag-gio, ac-qua. Apply the same rule if an apostrophe occurs in the middle of the word: Sen-z’altro, quaran-t’anni. In general an apostrophe may end a line if necessary, but in this case it may not, although it may be taken over along with the letter preceding it.

In the middle of a word, if the first consonant of a group is a liquid (l, m, n, or r) it remains with the preceding vowel, and the other consonant, or combination of consonants, goes with the succeeding vowel: al-tero, ar-tigiano, tem-pra.

12.11 Japanese

Japanese is expressed and printed in ideographs of Chinese origin (kanji), interspersed with an alphabet-based script (kana), of which there are two versions: the hiragana (the cursive form) is used for inflectional endings and words with grammatical significance, and the katakana (the ‘squared’ form) is used for foreign loanwords and in Western names. Both vertical columns running right to left and horizontal left-to-right layout are used.

The most frequently used system of romanization uses the macron − to indicate long vowels; syllable-final n is followed by an apostrophe before e or y. The inclusion of macrons is optional in non-specialist works, and maybe omitted in well-established forms of place names, such as Hokkaido, Honshu, Kobe, Kyoto, Kyushu, Osaka, Tokyo.

12.12 Latin

12.12.1 Alphabet

The standard Latin alphabet consists of twenty-one letters, A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X, plus two imports from Greek, Y and Z. A, E, O, Y are vowels. I, V may be either vowels or consonants.

Early modern printers invented a distinction between vocalic i, u and consonantal j, v; many scholars, especially when writing for general readers, still retain it with u/v, distinguishing solvit with two syllables from coluit with three (also volvit ‘rolls/rolled’ from voluit ‘willed’), but others prefer to use V for the capital and u for the lower case irrespective of value. (However, the numeral must be v regardless of case.) By contrast, the use of j is virtually obsolete except in legal and other stock phrases used in an English context, such as de jure.

In classical Latin the ligatures œ, œ are found only as space-saving devices in inscriptions. They are found in post-classical manuscripts and in printed books down to the nineteenth century and occasionally beyond. They should not now be used unless a source containing them is to be reproduced exactly.

12.12.2 Accents

In modern usage Latin is normally written without accents. In classical Latin the apex, resembling an acute, was sometimes used on long vowels other than I, and until recently ë was used to show that ae and oe did not form a diphthong: aëris ‘of air’ (as opposed to aeris ‘of bronze/money’), poëta ‘poet’. Older practice used the circumflex on long vowels to resolve ambiguity: mensâ ablative of mensa ‘table’; one may also find the grave accent on the final syllables of adverbs. In grammars and dictionaries vowels may be marked with the macron or the breve: mēnsă nominative, mēnsā ablative.

12.12.3 Capitalization

Classical Latin made no distinction between capital and lower case. In modern usage proper names and their derivatives are capitalized (Roma ‘Rome’, Romanus, ‘Roman’, Graece ‘in Greek’) except in verbs (graecissare ‘speak Greek/live it up’); the first letter in a sentence may or may not be capitalized, that in a line of verse no longer so.

In titles of works, one may find (proper names apart) only the first word capitalized (De rerum natura, De imperio Cn. Pompei—Oxford’s preference), first and main words (De Rerum Natura, De Imperio Cn. Pompei), or main words only (de Rerum Natura, de Imperio Cn. Pompei), even proper nouns only (de rerum natura, de imperio Cn. Pompei). For the treatment of Latin titles within titles see 8.2.7.

12.12.4 Word division

A vowel may be divided from another (be-atus) unless they form a diphthong, as do most instances of ae, oe, ei, au, and eu. When v is not used, the correct divisions with consonantal u are ama-uit, dele-uit. Likewise, a consonantal і is taken over (in-iustus).

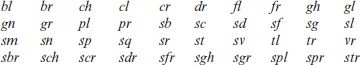

Take over x between vowels (pro-ximus). Any doubled consonants may be divided; except in mn, the letters l, m, n, and r may be divided from a following consonant. Traditionally, any group capable of beginning a word in either Latin or Greek was not divided: for example bl, br, ch, cl, cr, ct, dl, dr, gn, gu, mn, ph, pl, pr, ps, pt, qu, th, tl, and tr (many of these are found in such English words as ctenoid, gnomon, mnemonic, pneumonia, psychology, and ptomaine).

However, as in Greek, these rules should be subject to the overriding precept that prefixes and suffixes are separated and compounds divided into their parts. This requires knowledge of the language, as some common prefixes may have different forms in different contexts.

12.12.5 Numerals

Latin, of course, uses Roman numerals, which are described at 11.5. They should generally be set in small capitals. The letter C was sometimes used in reversed form in numerals: 1Ɔ 500 (normally written as D), CIƆ 1,000 (otherwise written M) or ī, which unlike M was already used in antiquity.

12.13 Old and Middle English

12.13.1 Alphabet

Old English is the name given to the earliest stage of English, in use until around 1150. Middle English is the name given to the English of the period between Old and modern English, roughly 1150 to 1500.

Several special characters are (or have been) employed in the printing of both Old and Middle English texts:

In printing Old and Middle English no attempt should be made to regularize the use of eth and thorn even in the same word; scribes used both letters at random. Whereas eth had died out by the end of the thirteenth century, thorn continued in use into the fifteenth century, and even later as the у for th of early Scots printing and in ye or ye used for the and yt, yt, yat, for that; hence Ye Olde was originally read The Old.

12.13.2 Punctuation

Except in specialized texts, normal modern English punctuation conventions should be applied to Old and Middle English. In manuscripts, editors should not attempt to regularize or correct individual punctuation marks, especially as these marks do not necessarily perform functions equivalent to those of their modern counterparts: in the Old English of the late tenth and eleventh centuries a semicolon was the strongest stop and a full point the weakest.

12.14 Portuguese

12.14.1 Introduction

Brazilian Portuguese differs considerably in spelling, pronunciation, and syntax from that of Portugal, far more so than US English differs from British English. Attempts to achieve agreement on spelling have not been very successful, and important differences in practice have been indicated below. In contrast to the case in English, differences of spelling and pronunciation generally go hand in hand.

12.14.2 Alphabet and spelling

The letters k, w, and y are used only in loanwords. Apart from rr and ss, double consonants are confined to European Portuguese: acção ‘action, share’, accionista ‘shareholder’, comummente ‘commonly’, in Brazilian Portuguese ação, acionista, comumente. Several other consonant groups have been simplified in Brazilian Portuguese: acto, amnistía, excepção, óptico, súbdito (= subject of a king), subtil are ato, anistia, exceção, ótico, súdito, sutil.

In Brazilian Portuguese the numbers 16, 17, and 19 are spelled dezesseis, dezessete, dezenove in contrast to European Portuguese deza-; 14 may be quatorze beside catorze.

There are also many differences of vocabulary and idiom, such as frequent omission of the definite article after todo ‘every’ and before possessives.

12.14.3 Accents

European Portuguese uses four written accents on vowels: acute, grave, circumflex, and tilde (til in Portuguese); Brazilian Portuguese also uses the diaeresis. The acute may be used on any vowel; the grave only on a; the circumflex on a, e, and o; the tilde on a and o. The diaeresis is used on u between q/g and e/i to show that the vowel is pronounced separately.

Normal stress is unaccented; abnormal stress is accented. The rules of accentuation are complex, and cannot be fully described in a work of this type. Normal stress falls on the penultimate syllable in words ending in -a, -am, -as, -e, -em, -ens, -es, -o, -os; in all other cases (including words in -ã) the stress falls on the final syllable.

Note the use of the circumflex in words like circunstância, paciência, and cômputo, where m or n with a consonant follows the accented vowel. In Brazilian Portuguese the circumflex is also used when m or n is followed by a vowel: Nêmesis, helênico, cômodo, sônico. European Portuguese generally has an acute accent, so Némesis, helénico, cómodo, sónico. Thus we have António in European Portuguese but Antônio in Brazilian Portuguese; editors should ensure that any such names are correctly spelled according to their bearers’ nationality.

12.14.4 Punctuation

The inverted question marks and exclamation marks which are characteristic of Spanish are not normally used in Portuguese.

12.14.5 Word division

Take over ch, lh, nh, and b, c, d, f, g, p, t, v followed by l or r; divide rr, ss, also sc, sç. Otherwise divide at obvious prefixes such as auto-, extra-, supra-, etc. When a word is divided at a pre-existing hyphen, repeat the hyphen at the beginning of the next line: dar-lho is divided dar- -lho.

12.15 Russian

12.15.1 Alphabet and transliteration

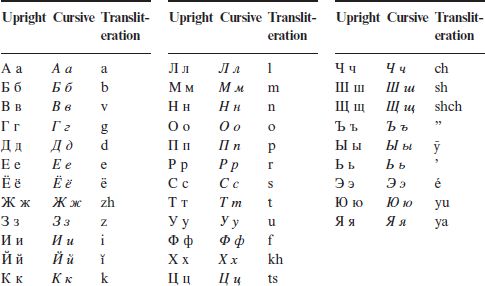

Russian is one of the six Slavonic languages written in Cyrillic script (see Slavonic languages at 12.17 for a list of the others). Table 12.7 includes ‘upright’ (pryamoĭ) and ‘cursivǐ’ (kursiv) forms and also a transliteration in accordance with the ‘British System’ as given in British Standard 2979 (1958). For a brief discussion of the problems of transliteration see 12.17.1.

12.15.2 Abbreviations

One of the distinctive aspects of non-literary texts of the Soviet period was the extensive use of abbreviations, used to a far lesser extent in the post-Soviet language.

In lower-case abbreviations with full points, any spaces in the original should be kept, for example и т. д., и пр., but с.-д. Abbreviations by contraction, such as д-р, have no points. Abbreviations with a solidus are typically used in abbreviations of unhyphenated compound words.

Table 12.7 Russian alphabet

Abbreviations consisting of capital initial letters, such as OOO (‘Ltd’), are set close without internal or final points. Commonly used lowercase abbreviations that are pronounced syllabically and declined, for example вуз, are not set with points.

Abbreviations for metric and other units are usually set in cursive and are not followed by a full point; abbreviated qualifying adjectives do have the full point, however (5 кB. кM etc.).

12.15.3 Capitalization

Capital initial letters are in general rarer in Russian than in English. Capitalize personal names, but use lower-case initial letters for nouns and adjectives formed from them:

| тротскист ‘Trotskyite’ | марксизм ‘Marxism’ |

and for nationalities, names of nationals, and inhabitants of towns:

| татарин ‘Tartar’ | англичанин Englishman’ |

Ranks, titles, etc. are also lower case:

святой Николай ‘Saint Nicholas’

князь Оболенский ‘Prince Obolensky’

Each word in names of countries takes a capital:

Соединённые Штаты Америки ‘United States of America’

Adjectives formed from geographical names are lower case except when they form part of a proper noun or the name of an institution:

европейские государства ‘European states’

but

Архангельские воздушные линии ‘Archangel Airlines’

Geographical terms forming part of the name of an area or place are lower case:

| остров Рудольфа ‘Rudolph Island’ | Северный полюс ‘the North Pole’ |

Capitalize only the first word and proper nouns in titles of organizations and institutions, and of literary and musical works, newspapers, and journals.

Days of the week and names of the months are lower case, but note Первое мая and 1-е Мая for the May Day holiday.

The pronoun of the first-person singular, я = I, is lower case (except, of course, when used at the beginning of a sentence).

12.15.4 Punctuation

Hyphen

The hyphen is used in nouns consisting of two elements:

интернет-сайт ‘website’

вице-спикер Думы ‘The Deputy Speaker of the Duma’

It is also used in compound place names, Russian or foreign, consisting of separable words.

Dash

En rules are not used in Russian typography; em rules set close up take their place. Spaced em rules are much used in Russian texts; they may indicate that a word needs to be understood, or represent the rarely used present tense of быть ‘to be’.

линия Москва — Киев ‘the Moscow–Kiev line’

Иван играет на рояле, а Людмила — на скрипке ‘Ivan plays the piano, Lyudmila the violin’:

Волга — самая большая река в Европе ‘the Volga is the longest European river’

Dashes are also used to introduce direct speech.

Quotation marks

Guillemets, set close, are used to indicate direct speech and special word usage and with titles of literary works, journals, etc.

12.15.5 Word division

Russian syllables end in a vowel, and word division is basically syllabic. However, there are many exceptions to this generalization, most of which are connected with Russian word formation. Consonant groups may be taken over entire or divided where convenient (provided at least one consonant is taken over), subject to the following rules.

12.15.6 Numerals

Arabic numerals are used. Numbers from 10,000 upwards are divided off into thousands by thin spaces, and not by commas (26 453); below 10,000 they are set closed up (9999). The decimal comma is used in place of the decimal point (0,36578). Ordinal numbers are followed by a contracted adjectival termination except when they are used in dates (5-й год but 7 ноября 1917 г.).

12.16 Scandinavian languages

12.16.1 Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish

Forms of Norwegian

Norway, which until the middle of the nineteenth century used Danish as its literary language, now has two written languages: bokmål (also called riksmål), a modified form of Danish, and nynorsk (also called landsmål), a reconstruction of what Norwegian might have been but for the imposition of Danish. Each of these has several variants, and the only safe rule for the non-expert is to assume that all inconsistencies are correct.

Alphabets and accents

Modern Danish and Norwegian have identical alphabets, the twenty-six letters of the English alphabet being followed by æ, ø, å; in their place Swedish has å, ä, ö. The letter å, found in Swedish since the sixteenth century, was adopted in Norway in 1907, and in Denmark in 1948; previously these languages used aa (cap. Aa).

Acute accents are found in loanwords and numerous Swedish surnames, and occasionally for clarity, for example Danish én ‘one’, neuter ét (also een, eet) as against indefinite article en, et. The grave accent is sometimes used in Norwegian to distinguish emphatic forms.

Capitalization

Until 1948 Danish nouns were capitalized as in German, a practice also found in nineteenth-century Norwegian. All the languages now tend to favour lower-case forms, for example for days, months, festivals, and historical events. This also applies to book titles; but periodical and series titles are legally deposited names, complete with any capitals they may have.

Institutional names are often given capitals for only the first word and the last; but in Danish and Norwegian some names begin with the independent definite article, which then must always be included and capitalized, Den, Det, De (= Dei in Nynorsk).

Capitalize the polite form of the second person in Danish and Norwegian: De, Dem, Deres (Nynorsk: De, Dykk, Dykkar). In Danish capitalize also the familiar second person plural, I, to distinguish it from і (‘in’).

Word division

Compounds are divided into their constituent parts, including prefixes and suffixes. In Danish take over sk, sp, st, and combinations of three or more consonants that may begin a word (including skj, spj). In Norwegian or Swedish take over only the last letter; ng representing a single sound is kept back, and in Swedish x; other groups that represent a single sound are taken over (Norwegian gj, kj, sj, skj, Swedish sk before e, i, y, ä, ö). In Swedish compounds three identical consonants are reduced to two, but the third is restored when the word is broken: rättrogen (‘orthodox’), divided rätt|trogen.

12.16.2 Icelandic and Faeroese

Alphabets and accents

In both languages the letter d is followed by ð. Icelandic alphabetization has þ, æ, ö after z; Faeroese has œ, ø. The vowels a, e, i, o, u, y may all take an acute accent. Icelandic uses x, Faeroese ks; the Icelandic þ corresponds to the Faeroese t.

Capitalization

Icelandic capitalization is minimal, for proper nouns only. In institutional names only the initial article (masculine Hinn, feminine Hin, neuter Hið) should be capitalized. Faeroese follows Danish practice, though polite pronouns are not capitalized.

12.17 Slavonic languages

12.17.1 Scripts and transliteration

Of the Slavonic languages Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, and Macedonian are written in the Cyrillic alphabet, Polish, Czech, Slovak, Sorbían, Croatian, Bosnian, and Slovene in the Latin. At the time of writing Serbian is written in either.

See 12.15.1 and Table 12.7 for details of the Cyrillic alphabet. The extra sorts called for by the languages other than Russian that use Cyrillic are Belarusian і (= і) and y̆ (= w); Macedonian ѓ (= ǵ), s (= dz), j (= j), Љ (= lj), Њ, (= nj), Ќ (= ḱ), and џ (= dž); Serbian Ђ, ђ (= đ), j (=j), Љ (= lj), Њ, (= nj), Ћ, ћ (= ć), and џ (= dž); and Ukrainian ґ (= g), є (= ye), i (= i), and ï (= yi). In some Macedonian and Serbian fonts cursive г, n, and m are in the form of superior-barred cursive ī, ū, and ɯ̄ respectively.

Transliteration systems are largely similar for those languages written in Cyrillic, but at the time of writing there is still no internationally agreed, unitary system. Of the three currently most favoured systems, the ALA-Library of Congress, International Scholarly, and British, the ALA-LC system seems to be gaining ground because of its increasing use in national and academic libraries, spurred on by developments in information technology and standardized, machine-readable cataloguing systems.

Wherever possible, adhere to a single transliteration system throughout a single work. In texts using transliterated Russian, as well as Belarusian, Bulgarian, and Ukrainian, authors and editors should avoid mixing, for example, the usual British ya, yo, yu, the Library of Congress ia, io, iu, and the philological ja, jo, ju. (Note that the transliteration of Serbian and Macedonian operates according to different rules.)

12.17.2 Belarusian

In standard transliteration of Belarusian (also called Belorussian), the diacritics ǐ, й, è (or ė, é), and ʹ (soft sign) are used. In specialist texts, the philological system requires č, ë, š, ž. The Library of Congress system requires ligatured i͡a, i͡o, i͡u, z͡h In practice the ligature is often omitted, as many non-specialist typesetters have difficulty reproducing it; this is the case for all languages that employ this system.

12.17.3 Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian

Linguistic nomenclature in the former Yugoslavia is still very contentious. Serbo-Croat was the main official language of Yugoslavia: although the term Serbo-Croat is still used by some linguists in Serbia and Bosnia–Herzegovina, the ISO has assigned codes to Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian. Oversimplifying, Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) in Bosnia–Herzegovina use Bosnian, Croats in Croatia and Bosnia–Herzegovina use Croat, while Serbs in Serbia and Montenegro and in Bosnia–Herzegovina use Serbian.

The Roman alphabet used for Bosnian and Croatian is the standard latinica that is to be used for transliterating Serbian even for lay readers: thus четници will be četnici not chetnitsi.

The Cyrillic alphabet is ordered а б в г д ђ е ж з и ј к л љ м н њ о п р с т ħ у ф х ц ч џ ш; both in transliterated Serbian and in Croatian, the latinica order is a b c č ć d dž đ e f g h i j k l lj m n nj o p r s š t u v z ž.

Diacritics for transliterated Serbian are ć, č, š, ž; special characters are Đ đ.

12.17.4 Bulgarian

The ALA-LC system of transliteration uses the diacritics ǐ, й, and the letter combinations zh, kh, eh, sh, sht. It also requires the ligatures i͡a, i͡u, t͡s The philological system requires č, š, ž.

12.17.5 Czech and Slovak

Czech and Slovak are written using the Roman alphabet, which in Czech is a á b c č d ď e é ě f g h ch i í j k l m n ň o ó p r ř s š t ť u ú ů v y ý z ž; in alphabetizing, ignore accents on vowels and on d, n, and t. The Slovak alphabet is a á ä b c č d ď e é f g h ch i í j k l ĺ ľ m n ň o ó ôp r ŕ s š t ť u ú v y ý z ž; in alphabetizing, ignore acute, circumflex, and accents on d, l, n, r, and t.

The diacritics used in Czech are á, é, í, ó, ú, ý, ů, č, ď, ě, ň, ř, š, ť, ž. The palatalization of d, t is always indicated by a háček in upper case (Ď, Ť) and in lower case either by a háček (ď, ť) or—preferably—a high comma right (d’, t’). Slovak uses the diacritics ä, á, é, í, ĺ, ó, ŕ, ú, ý, ô, č, d’, l’, ň, š, t’, ž. The palatalization of d and t is the same as for Czech; that for the Slovak l can be either a háček or high comma right in upper case (Ľ, L’) and a high comma right in lower case (l’).

12.17.6 Macedonian

Macedonian is written in the Cyrillic alphabet, with a transliteration system similar to that used for Serbian. The diacritics used are ǵ, ḱ, č, š, ž, and the apostrophe; the letter combinations lj, nj, dž should not be broken in word division.

12.17.7 Old Church Slavonic

Also called Old Bulgarian, Old Church Slavonic was written in the Cyrillic alphabet as well as the older Glagolitic alphabet. The regional variants that developed from it are known collectively as Church Slavonic.

The diacritics and ligatures used in the Library of Congress’s transliteration of Church Slavonic are ǵ, ḟ, v, ẏ, ż, ě,  (with ogonek or right-facing hook on e, o), o͡t, ē, ī, ō, ū, ȳ, ǐ, ę, ǫ (ogonek). In Russian Church Slavonic, ja/ya/ia may correspond to ę and i͡ę, u to ǫ, and ju/yu/iu to i͡ǫ. The philological system uses č, š, ž. Special characters are ′ (soft sign), ″ (hard sign).

(with ogonek or right-facing hook on e, o), o͡t, ē, ī, ō, ū, ȳ, ǐ, ę, ǫ (ogonek). In Russian Church Slavonic, ja/ya/ia may correspond to ę and i͡ę, u to ǫ, and ju/yu/iu to i͡ǫ. The philological system uses č, š, ž. Special characters are ′ (soft sign), ″ (hard sign).

12.17.8 Polish

Polish is written in the Roman alphabet, as in English without q, v, and x. It employs the diacritics ć, ń, ó, ś, ź, ż, and Ą, ą, Ę, ę (ogonek, hook right); in addition there is one special character, the crossed (or Polish) l (Ł ł).

Alphabetical order is: a ą b c ć d e ę f g h i j k l ł m n ń o ó p r s ś t u w y z ź ż. The digraphs ch, cz, dz, dź, dż, rz, and sz are not considered single letters of the alphabet for ordering purposes; however, these letter combinations should not be separated in dividing words.

12.17.9 Slovene

Slovene (also called Slovenian) is written in the Roman alphabet and uses the háček on č, š, ž; the digraph dž is not considered a single letter.

12.17.10 Ukrainian

The philological system requires č, š, ž, ĭ, ï, ′ (soft sign), and the letter combinations je, šč, ju, ja. The Library of Congress system requires ligatured i͡a, i͡e, i͡u, z͡h as with Belarusian, the ligature is often omitted. The Ukrainian и is transliterated as y, not і (which represents Ukrainian і).

12.18 Spanish

12.18.1 Introduction

The Spanish used in Spain and the Spanish spoken in Latin America are mutually intelligible in much the same way that American and British English are. However, there are important differences in vocabulary and usage both between Spain and Latin America and among the Latin American countries—it is a mistake to think that Latin American Spanish is a uniform variant of the language.

12.18.2 Alphabet and spelling

In older works ch and ll were treated as separate letters for alphabetical purposes, but this is now very dated. The letter Ñ, ñ is treated as a separate letter. The letters k and w are used only in loanwords from other languages and their derivatives.

The only doubled consonants in Spanish are cc before e or i, rr, ll, and nn in compounds. They can be remembered as the consonants appearing in CaRoLiNe. Where an English speaker might expect a double consonant, Spanish normally simply has one, as in posible ‘possible’.

12.18.3 Accents

Normal stress in Spanish falls on either the penultimate or the last syllable, according to complex rules. Normal stress is not indicated by an accent; an acute accent is used when the rules for normal stress are broken. The only other diacritical marks used are the tilde on the ñ, and the diaeresis on ü, following g before e or i, where u forms a diphthong with e or i. Accents are normally used on capitals.

The accent is used to show interrogative and exclamatory use in the following words:

| cuál ‘what’, ‘which’ | cómo ‘how’ | cuándo ‘when’ |

| cuánto ‘how many/much’ | dónde ‘when’ | qué ‘what’ |

| quién ‘who’ |

The accented forms are used in indirect questions. In 1959 the Real Academia decreed that, except in ambiguous cases, the accent is not needed on demonstrative pronouns este (‘this one’), ese (‘that one’), aquel (‘that one, further away’) with their feminine equivalents, esta, esa, aquella, and plurals estos/estas, esos/esas, aquellos, laquellas. This ruling is not universally accepted, however, and both conventions will be found. The neuter forms esto, eso, aquello are never accented.

12.18.4 Capitalization

Capitals are used in much the same way as in English in proper names. Practice differs in titles of books, poems, plays, and articles, where normally the first word and proper nouns are capitalized:

Cien años de soledad

La deshumanización del arte

Doña Rosita la soltera, o El lenguaje de las flores

El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha.

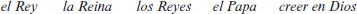

Capitalize names of high political or religious authorities—when not followed by their first name—and references to God:

butRoman numerals indicating centuries are generally given in full capitals: el sigh XI.

| el rey Carlos III | el papa Juan XXIII |

Lower case is usually used for names of posts and titles:

This may include non-Spanish titles such as sir or lord: el embajador británico sir Derek Plumbly.

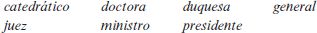

Also written in lower case are:

Traditionally names of the days of the week, months, and seasons take a lower-case initial letter, but the use of capitals for these words is now very common and cannot be assumed to be a mistake.

12.18.5 Punctuation

The most obvious differences from other European languages are the inverted exclamation mark and question mark inserted at the place where the exclamation or question begins:

| ¡Mire! ‘Look!’ | ¿Dónde vas? | ‘Where are you going?’ |

This need not be the start of the sentence:

Si ganases el Gordo, ¿qué harías? ‘If you won the jackpot what would you do?’

Quotation marks take the form of guillemets (called comillas), set closed up (e.g. «¡Hola!»). However, it is more common—especially in fiction—to dispense with comillas altogether and indicate speakers by a dash.

Colons are used before quotations (Dijo el alcalde: «Que comience la fiesta.»), in letters (Querido Pablo:), and before an enumeration (Trajeron de todo: cuchillos, cucharas, sartenes, etc.). Points of suspension are set closed up with space following but not preceding them.

12.18.6 Word division

The general rule is that a consonant between two vowels and the second of two consonants must be taken over to the next line. The combinations ch, ll, and rr are indivisible and must be taken over: mu-chacho, arti-llería, pe-rro.

The consonants b, c, f, g, p followed by l or r must be taken over as a pair: ha-blar ‘to speak’, ju-glar ‘minstrel’; so must dr and tr, as in ma-drugada ‘dawn’, pa-tria ‘fatherland’.

The letter s must be divided from any following consonant: Is-lam, hués-ped ‘guest, host’, Is-rael, cris-tiano; similarly Es-teban ‘Stephen’, es-trella ‘star’, even in a compound (ins-tar ‘to urge’, ins-piractión).