CHAPTER 10

Abbreviations and symbols

10.1 General principles

Abbreviations fall into three categories. Strictly speaking, only the first of these is technically an abbreviation, though the term loosely covers them all, and guidelines for their use overlap. There is a further category, that of symbols, which are more abstract representations.

In work for a general audience do not use abbreviations or symbols in open text (that is, in the main text but not including material in parentheses) unless they are very familiar indeed (US, BBC, UN), or would be unfamiliar if spelt out (DNA, SIM card), or space is scarce, or terms are repeated so often that abbreviations are easier to absorb. Abbreviations are more appropriate in parentheses and in ancillary matter such as appendices, bibliographies, captions, figures, notes, references, and tables, and rules differ for these.

It is helpful to spell out abbreviations at first mention, adding the abbreviation in parentheses after it:

the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)

It is generally better to avoid an abbreviation in a chapter title or heading but, if unavoidable, spell it out at the first mention in the text proper. Some house styles for specialist works make exception for abbreviations that are so familiar to a technical readership they do not need to be defined, such as RAM (random-access memory) in an academic computer book. It is helpful to authors and editors if the house style lists these exceptions. (See 14.3.1.)

It is not necessary to define an abbreviation at first mention in each chapter unless the book is likely to be read out of sequence, as in a multi-author work or a textbook. If this is the case, or simply if many abbreviations are used, including a list of abbreviations or a glossary is a good way to avoid repeatedly expanding abbreviations (see 1.2.14). Titles of qualifications and honours placed after personal names are an exception to the general rule that initialisms should be spelled out; many forms not familiar to most people are customarily cited:

Alasdair Andrews, Bt, CBE, MVO, MFH

For more on titles see 6.1.4.

It is possible to refer to a recently mentioned full name by a more readable shortened form, rather than—or in addition to—a set of initials: the Institute rather than IHGS for the Institute of Heraldic and Genealogical Studies. (See also 5.3.2.)

As a general rule, avoid mixing abbreviations and full words of similar terms, although specialist or even common usage may militate against this, as in Newark, JFK, and LaGuardia airports.

For lists of abbreviations see 1.2.14; for legal abbreviations see 13.2.2; for abbreviations in or with names see 6.1.1. For Latin bibliographic abbreviations such as ‘ibid.’ see 17.2.5.

10.2 Punctuation and typography

10.2.1 Full points?

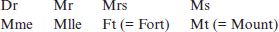

Traditionally, abbreviations end in full points while contractions do not, so that we have Jun. and Jr for Junior, and Rev. and Revd for Reverend. This rule is handy and in general is borne out, although there are some exceptions: for example St. (= Street) is often written with a point to avoid confusion with St for Saint, and no. (= numero, Latin for number). Note that everyday titles such as Mr, Mrs, and Dr, being contractions, are written without a point, as is Ltd; editors need not attempt to establish how a particular company styles Ltd in its name. US style uses more points than British style does, even with contractions, thus giving Jr. instead of Jr (no point). (See 6.1.3.)

A problem can arise with plural forms of abbreviations such as vol. (volume) or ch. (chapter): these would strictly be vols and chs, which are contractions and should not end with a point. However, this can lead to the inconsistent-looking juxtaposition of vol. and vols or ch. and chs, and so in some styles full points are retained for all such short forms. Similarly, Bros, the plural form of Bro. ‘brother’, is often written with a point.

Technical and scientific writing uses less punctuation than non-technical English. Metric abbreviations such as m (metre), km (kilometre), and g (gram) do not usually have a full point, and never do in scientific or technical writing. Purely scientific abbreviations (bps = bits per second; mRNA = messenger ribonucleic acid) are presented without full points.

There are other exceptions to the principle that abbreviations have full points. For example, abbreviations for eras, such as AD and BC (traditionally written in small capitals), have no points. Arabic and Roman ordinal numbers take no points (1st, 2nd, 3rd); similarly, monetary amounts (£6 m, 50p) and book sizes (4to, 8vo, 12mo) do not have points. Note also that there are no points in colloquial abbreviations that have become established words in their own right, such as demo (demonstration) or trad (traditional).

If an abbreviation ends with a full point but does not end the sentence, other punctuation follows naturally: Gill & Co., Oxford. If the full point of the abbreviation ends the sentence, however, there is no second full point: Oxford’s Gill & Co.

10.2.2 Ampersands

Avoid ampersands except in established combinations (e.g. R & B, T & C) and in names of firms that use them (M&S, Mills & Boon). There should be spaces around the ampersand except in company names such as M&S that are so styled; in journalism ordinary combinations such as R&B are frequently written with no spaces.

10.2.3 Apostrophes

Place the apostrophe in the position corresponding to the missing letter or letters (fo’c’s’le, ha’p’orth, sou’wester, t’other), but note that shan’t has only one apostrophe. Informal contractions such as I’m, can’t, it’s, mustn’t, and he’ll are perfectly acceptable in less formal writing, especially fiction and reported speech, and are sometimes found even in academic works. However, editors should not impose them except to maintain consistency within a varying text.

There are no apostrophes in colloquial abbreviations that have become standard words in the language, such as cello, flu, phone, or plane. Retain the original apostrophe only when archaism is intentional, or when it is necessary to reproduce older copy precisely. Old-fashioned or literary abbreviated forms such as ’tis, ’twas, and ’twixt do need an opening apostrophe, however: make sure that it is set the right way round, and not as an opening quotation mark.

10.2.4 All-capital abbreviations

Abbreviations of a single capital letter normally take full points (G. Lane, Oxford U.) except when used as symbols (see 10.3 below); abbreviated single-letter compass directions have no points, however: N, S, E, W.

Acronyms or initialisms of more than one capital letter take no full points in British and technical usage, and are closed up:

In some US styles certain initialisms may have full points (US/U.S.). In some house styles any all-capital proper-name acronym that may be pronounced as a word is written with a single initial capital, giving Basic, Unesco, Unicef, etc.; some styles dictate that an acronym is written thus if it exceeds a certain number of letters (often four). Editors should avoid this rule, useful though it is, where the result runs against the common practice of a discipline or where similar terms would be treated dissimilarly based on length alone.

Where a text is rife with full-capital abbreviations, they can be set all in small capitals to avoid the jarring look of having too many capitals on the printed page. Some abbreviations (e.g. BC, AD) are always set in small capitals (see 7.5.2).

For treatment of personal initials see 6.1.1; for postcodes and zip codes see 6.2.4.

10.2.5 Lower-case abbreviations

Lower-case abbreviations are usually written with no points (mph, plc), especially in scientific contexts.

In running text lower-case abbreviations cannot begin a sentence in their abbreviated form. In notes, however, a group of exceptions may be allowed: c., e.g., i.e., l., ll., p., pp. are lower case even at the beginning of a note.

Write a.m. and p.m. in lower case, with two points; use them only with figures, and never with o’clock. see 11.3 for more on times of day.

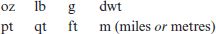

Short forms of weights and measures are generally not written with a point, with the exception of forms such as gal. (gallon) and in. (inch) that are not in technical use:

Note that min., and sec. have a point in general contexts but are not used in scientific work.

When an abbreviated unit is used with a number there is usually a space between them (see 14.1.4):

a unit of weight equal to 2,240 lb avoirdupois (1016.05 kg)

10.2.6 Upper- and lower-case abbreviations

Contracted titles and components of names do not require a full point:

St. meaning ‘street’ is traditionally written with a point to distinguish it from St meaning ‘saint’.

Shortened forms of academic degree are usually written without punctuation (PhD, MLitt). For plurals, see 10.5.

British counties with abbreviated forms take a full point (Berks., Yorks.), with the traditional exceptions Hants, Northants, and Oxon, whose abbreviations were derived originally from older spellings or Latin forms.

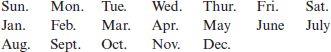

Names of days and months should generally be shown in full, but where necessary, as in notes and to save space, they are abbreviated thus:

10.2.7 Work titles

Italic text (e.g. titles of books, plays, and journals) usually produces italic abbreviations:

DNB (Dictionary of National Biography)

Arist. Metaph. (Aristotle’s Metaphysics)

Follow the forms familiar in a given discipline; even then permutations can exist, often depending on the space available or on whether the abbreviation is destined for running text or a note.

For legal references see Chapter 13.

10.3 Symbols

Symbols or signs are a shorthand notation signifying a word or concept. They may be special typographical sorts, or letters of the alphabet. Symbols are a frequent feature of scientific and technical writing, but many are also used in everyday contexts, for example to denote copyright (©), currencies (£, $, €), degrees (°), feet and inches (′, ″), and percentages (%).

Do not start a sentence with a symbol: spell out the word or recast the sentence to avoid it:

| Sixteen dollars was the price | The price was $16 |

| Section 11 states … | As §11 states, … |

Symbols formed from words are normally set close up before or after the things they modify (GeV, Σ+), or set with space either side if standing alone for words or concepts (a W chromosome). Symbols consisting of or including letters of the alphabet never take points. Abstract, purely typographical symbols follow similar rules, being either closed up (° # ¿ » %) or spaced. In coordinates, the symbols of measurement (degrees, seconds, etc.) are set close up to the figure, not the compass point (see 14.1.8):

52° N 15° 7′ 5″ W

Authors should use Unicode-compliant fonts (such as Times New Roman) when creating special sorts in their typescripts (see also 2.5). If there are many special sorts present, authors should create a PDF showing the special sorts correctly and provide it to the publisher.

As an alternative to superior numbers the symbols *, †, ‡, §, ¶, || may be used as reference marks or note cues, in that order. This system is based on print-page conventions and does not translate well into ebooks or online publishing.

The signs + (plus), − (minus), = (equal to), > (‘larger than’, in etymology signifying ‘gives’ or ‘has given’), < (‘smaller than’, in etymology signifying ‘derived from’) are often used in biological and philological works, and not only in those that are scientific or arithmetical in nature. In such instances +, –, =, >, < should not be printed close up, but rather separated by the normal space of the line or a thin space (be consistent). (See also 4.12.4 and 14.6.3.)

The use of symbols can differ between disciplines. For example, in philological works an asterisk (*) prefixed to a word signifies a reconstructed form; in grammatical works it signifies an incorrect or non-standard form. A dagger (†) may signify an obsolete word, or ‘deceased’ when placed before a person’s name.

The distinction between abbreviation and symbol may sometimes be blurred in technical contexts: some forms which are derived directly from a word or words are classed as symbols. Examples are chemical elements such as Ag (silver) from argentum and U from uranium, and forms such as E from energy and m from mass which are used in equations rather than running text. For the use of symbols in science, mathematics, and computing see Chapter 14.

10.4 The indefinite article with abbreviations

The choice between a and an before an abbreviation depends on pronunciation, not spelling. Use a before abbreviations beginning with a consonant sound, including an aspirated h and a vowel pronounced with the sound of w or y:

| a BA degree | a KLM flight | a BBC announcer |

| a YMCA bed | a U-boat captain | a UNICEF card |

Use an before abbreviations beginning with a vowel sound, including unaspirated h:

| an MCC ruling | an FA cup match | an HDTV |

| an IOU | an MP | an RAC badge |

| an SOS signal | an NHS hospital |

This distinction assumes the reader will pronounce the sounds of the letters, rather than the words they stand for (a Football Association cup match, a high-definition television). MS for manuscript is normally pronounced as the full word, manuscript, and so takes a; MS for multiple sclerosis is often pronounced em-ess, and so takes an. ‘R.’ for rabbi is pronounced as rabbi (‘a R. Shimon wrote’).

The difference between sounding and spelling letters is equally important when choosing the article for abbreviations that are acronyms and for those that are not: a NASA launch but an MC’s toast.

10.5 Possessives and plurals

Abbreviations form the possessive in the ordinary way, with an apostrophe and s:

| a CEO’s salary | MPs’ assistants |

Most abbreviations form the plural by adding s; an apostrophe is not needed:

In plural forms of a single letter an apostrophe can sometimes be clearer:

A’s and S’s

the U’s

minding your p’s and q’s

When an abbreviation contains more than one full point, put the s after the final one (Ph.D.s, the d.t.s).

For abbreviations with one full point, such as ed., no., and Adm., see 10.2.1.

A few abbreviations have irregular plurals (e.g. Messrs for Mr). In some cases this stems from the Latin convention of doubling the letter to create plurals:

| ff. (folios or following pages) | pp. (pages) |

| ll. (lines) | MSS (manuscripts) |

| opp. cit. |

10.6 e.g., i.e., etc., et al.

Do not confuse ‘e.g.’ (from Latin exempli gratia), meaning ‘for example’, with ‘i.e.’ (Latin id est), meaning ‘that is’.

Compare

hand tools, e.g. hammer and screwdriver

with

hand tools, i.e. those able to be held in the user’s hands

Although many people employ ‘e.g.’ and ‘i.e.’ quite naturally in speech as well as writing, prefer ‘for example’, ‘such as’ (or, more informally, ‘like’), and ‘that is’ in running text. Conversely, adopt ‘e.g.’ and ‘i.e.’ within parentheses or notes, since abbreviations are preferred there.

A sentence in text cannot begin with ‘e.g.’ or ‘i.e.’; however, a note can, in which case they remain lower case.

Take care to distinguish ‘i.e.’ from the rarer ‘viz.’ (Latin videlicet, ‘namely’). Formerly some writers used ‘i.e.’ to supply a definition or paraphrase, and ‘viz.’ to introduce a list of items. However, it is Oxford’s preference either to replace ‘viz.’ with ‘namely’ or to prefer ‘i.e.’ in every case.

Write ‘e.g.’ and ‘i.e.’ in lower-case roman, with two points and no spaces. In Oxford’s style they are not followed by commas, to avoid double punctuation; commas are often used in US practice. A comma, colon, or dash should precede ‘e.g.’ and ‘i.e.’ A comma is generally used when there is no verb in the following phrase:

different fruits, e.g. apples, oranges, bananas, and cherries

part of a printed document, e.g. a book cover

Use a colon or dash before a clause or a long list:

digital cameras have the advantage of being solid-state devices— i.e. they don’t have moving parts

In full ‘etc.’ is et cetera, a Latin phrase meaning ‘and other things’. ‘Et al.’ is short for Latin et alii, ‘and others’. In general contexts both are lower-case roman, with a full point, though ‘et al.’ is sometimes italicized in bibliographic use. Do not use ‘&c.’ for ‘etc.’ except when duplicating historical typography. ‘Etc.’ is preceded by a comma if it follows more than one listed item: robins, sparrows, etc.; it is best to avoid using ‘etc.’ after only one item (robins etc.), as at least two examples are necessary to establish the relationship between the elements and show how the list might go on. The full point can be followed by a comma or whatever other punctuation would be required after an equivalent phrase such as and the like— but not by a second full point, to avoid double punctuation.

Use ‘etc.’ in technical or scholarly contexts such as notes and works of reference. Elsewhere, prefer such as, like, or for example before a list, or and so on, and the like after it; none of these can be used in combination with ‘etc.’ It is considered rude to use ‘etc.’ when listing individual people; use ‘and others’ instead; use ‘etc.’ when listing types of people, however. In a technical context, such as a bibliography, use ‘et al.’:

Daisy, Katie, Alexander, and others

duke, marquess, earl, etc.

Smith, Jones, Brown, et al.

Do not write ‘and etc.’: ‘etc.’ includes the meaning of ‘and’. Do not end a list with ‘etc.’ if it begins with ‘e.g.’, ‘including’, ‘for example’, or ‘such as’, since these indicate that the list is to be incomplete. Choose one or the other, not both.

10.7 Abbreviations with dates

In reference works and other contexts where space is limited the abbreviations ‘b.’ (born) and ‘d.’ (died) may be used. Both are usually roman, followed by a point, and printed close up to the following figures:

Amis, Martin (Louis) (b.1949), English novelist …

An en rule may also be used when a terminal date is in the future:

| The Times (1785–) | Jenny Benson (1960–) |

A fixed interword space after the date may give a better appearance in conjunction with the closing parenthesis that generally follows it:

| The Times (1785– ) | Jenny Benson (1960– ) |

For people the abbreviation b. is often preferred, as the bare en rule may be seen to connote undue anticipation.

The Latin circa, set roman or italic, meaning ‘about’, is used in English mainly with dates and quantities. Set the abbreviation, c. or ca, in roman or italic close up to any figures following (c.1020, c.£10,400), but spaced from words and letters (c. AD 44). In discursive prose it is usually preferable to use about or some when describing quantities, although approximately is better in scientific text:

| about eleven pints | some 14 acres | approximately 50 kg |

With a span of dates the abbreviation must be repeated before each date if both are approximate, as a single abbreviation is not understood to modify both dates:

Philo Judaeus (c.15 BC–c. AD 50)

Distinguish between c. and ?: the former is used where a particular year cannot be fixed upon, but only a period or range of several years; the latter where there are reasonable grounds for believing that a particular year is correct. It follows therefore that c. will more often be used with round numbers, such as the start and midpoint of a decade, than with numbers that fall between. See 4.8.2.

A form such as ‘c.1773’ might be used legitimately to mean ‘between 1772 and 1774’ or ‘between 1770 and 1775’. As such, it is best in discursive prose to indicate the earliest and latest dates by some other means. Historians employ a multiplication symbol for this purpose: 1996 × 1997 means ‘in 1996 or 1997, but we cannot tell which’; similarly, 1996 × 2004 means ‘no earlier than 1996 and no later than 2004’. Figures are not generally contracted in this context:

the architect Robert Smith (b.1772 × 1774, d.1855)

The Latin floruit, meaning ‘flourished’, is used in English where only an approximate date of activity for a person can be provided. Set the italicized abbreviation fl. or flor. before the year, years, or—where no concrete date(s) can be fixed—century, separated by a space:

| William of Coventry (fl. 1360) | Edward Fisher (fl. 1627–56) |

| Ralph Acton (flor. 14th c.) |