CHAPTER 5

Capitalization

5.1 General principles

Capital letters in English are used to punctuate sentences, to distinguish proper nouns from other words, for emphasis, and in headings and work titles. It is impossible to lay down absolute rules for all aspects of capitalization; as with hyphenation, the capitalization of a particular word will depend upon its role in the sentence, and also to some extent on a writer’s personal taste or on the house style being followed. Also, certain disciplines, especially history, have their own particular styles of capitalization. However, some broad principles are outlined below. Editors should respect the views of authors, except in cases of internal discrepancies. Both authors and editors should strive for consistency: before writing or editing too much of a work, consider the principles that should govern capitalization, and while working through the material create a style sheet showing capitalization choices, and stick to it.

Excessive use of capitals in emails and on online forums is frowned upon (it is regarded as ‘shouting’); on websites, words in capitals can be difficult to read, and it is better to use colour for emphasis.

For the use of capitals in work titles see 8.2.2 and 8.8. For capitalization in lists and tables see Chapter 15, in quotations and verse Chapter 9, in legal references 13.2.3, and in bibliographies 18.2.5. Small capitals are discussed at 7.5.2. For capitalization in languages other than English see Chapter 12 under the language concerned.

5.2 Sentence capitals

Capitalize the first letter of a word that begins a sentence, or the first of a set of words used as a sentence:

This had the makings of a disaster. Never mind.

Come on. Tell me!

Capitalize the first letter of a syntactically complete quoted sentence. If, as occasionally happens in fiction or journalism, quotation marks are not used, the first word is generally not capitalized:

Sylvie replied, ‘She’s a good girl.’

I thought, ‘There goes my theory.’

The question is, does anyone have an antidote?

Quoted single words or phrases that do not constitute a sentence are not capitalized:

He’d say ‘bye’ and run down the wide school steps

Certain young wines do not ‘travel well’

For a full discussion of quotation marks and the punctuation that accompanies them see 9.2.

In British English, matter following a colon begins with a lower-case initial, unless it is a displayed quotation or extract, but in US style a capital letter may be used after a colon if it introduces a complete sentence.

5.3 Use to indicate specific references

5.3.1 Use to create proper names

Initial capitals mark out the status of words so that the reader interprets them correctly. Ordinary proper names are usually recognizable even when they are set (through error or because of the preference of the person named) with lower-case initials. However, where a proper name consists of common nouns and qualifiers, initial capitals are needed to distinguish the specific usage from a general descriptive usage. Consider the difference in meaning, conferred by the application of initial capitals, between the following usages:

Tate Britain is the national gallery of British art

the National Gallery contains incomparable examples of British art

the city of London attracts millions of visitors every year

the City (London’s financial district)

the sun sets in the west

nationalist movements that posed a threat to the interests of the West

Some words are capitalized to distinguish their use in an abstract or specific sense. In the names of religious denominations the word church is capitalized, as in the Baptist Church, but church has a lower-case initial in general references to buildings, as in a Baptist church. (Note, however, that it would be usual to capitalize the full name of a specific building, as in Pond Street Baptist Church.)

Similarly, State is capitalized when it is used in an abstract or legal sense, as in the separation of Church and State, and in specific names of US states (New York State), but a reference to states in general will have a lower-case initial: seven Brazilian states. There is no need to capitalize the word government, whether it refers to a particular body of persons or to a general concept or body.

Historians commonly impose minimal capitalization on institutional references; this may sometimes appear unconventional and should not be permitted if it will obscure genuine differences in meaning (as, for example, between the catholic church and the Catholic Church), although readers will seldom misunderstand lower-case forms in context. The style is common in, and appropriate to, much historical work, but editors should not introduce it without consulting with the author and/or publisher.

It is as well, generally, to minimize the use of initial capitals where there is no detectable difference in meaning between capitalized and lower-case forms. Left and right are generally capitalized when they refer to political affiliations, but no reader would be likely to misinterpret the following in a book about British political life:

He is generally considered to be on the left in these debates

simply because it was not capitalized as

He is generally considered to be on the Left in these debates

Overuse of initial capitals is obtrusive, and can even confuse by suggesting false distinctions.

Capitals are sometimes used for humorous effect in fiction to convey a self-important or childish manner:

Poor Jessica. She has Absolutely No Idea.

Am irresistible Sex Goddess. Hurrah!

5.3.2 Formal and informal references

When one is referring back, after the first mention, to a capitalized compound relating to a proper name, the usual practice is to revert to lower case:

| Cambridge University | their university |

| the Ritz Hotel | that hotel |

| Lake Tanganyika | the lake |

| National Union of Mineworkers | the union |

| the Royal Air Force | the air force |

Capitals are sometimes used for a short-form mention of the title of a specified person, organization, or institution previously referred to in full:

the Ministry

the University statute

the College silver

the Centre’s policy

the Navy’s provisions

This style is found particularly in formal documents. Over the course of a book it is important to keep the practice within bounds and maintain strict consistency of treatment; it is easier to apply the rule that full formal titles are capitalized and subsequent informal references downcased.

Plural forms using one generic term to serve multiple names should be lower case:

Lake Erie and Lake Huron

lakes Erie and Huron

the Royal Geographical Society and Royal Historical Society

the Royal Geographical and Royal Historical societies

Oxford University and Cambridge University

Oxford and Cambridge universities

The rationale for this practice is that the plural form of the generic term is not part of the proper name but is merely a common description and thus ought not be capitalized.

5.4 Institutions, organizations, and movements

Capitalize the names of institutions, organizations, societies, movements, and groups:

| the World Bank | the British Museum |

| the State Department | the House of Lords |

| Ford Motor Company | the United Nations |

| the Crown | War On Want |

| the Beatles |

Generic terms are capitalized in the names of cultural movements and schools derived from proper names:

| the Oxford Movement | the Ashcan School |

Notice that the word the is not capitalized.

The tendency otherwise is to use lower case unless it is important to distinguish a specific from a general meaning. Compare, for example:

the Confederacy (the secessionist side in the American Civil War)

confederacy (as in ‘a federation of states’)

Romantic (nineteenth-century movement in the arts)

romantic (as in ‘given to romance’)

Certain disciplines and specialist contexts may require different treatment. Classicists, for example, will often capitalize Classical to define, say, sculpture in the fifth century BC as opposed to that of the Hellenistic era; editors should not institute this independently if an author has chosen not to do so.

5.5 Geographical locations and buildings

Capitalize names of geographical regions and areas, named astronomical and topographical features, buildings, and other constructions:

the Milky Way (but the earth, the sun, the moon, except in astronomical contexts (see 14.7.1) and personification)

New Englandthe Big Applethe Eternal City

Mexico City (but the city of Birmingham)

London Road (if so named, but the London road for one merely leading to London)

the Strait of Gibraltarthe Black Forest

the Thames Estuary (but the estuary of the Thames)

the Eiffel TowerTrafalgar Square

the Bridge of SighsTimes Square

River, sea, and ocean are generally capitalized when they follow the specific name:

| the East River | the Yellow River |

| the Aral Sea | the Atlantic Ocean |

However, where river is not part of the true name but is used only as an identifier it is downcased:

the Danube river

the River Tamar or the river Tamar

Capitalize compass directions only when they denote a recognized political or cultural entity:

| North Carolina | Northern Ireland (but northern England) |

| the mysterious East | the West End |

Usage in this area is very fluid, and terms may be capitalized or downcased depending on context and emphasis. For example, a book dealing in detail with particular aspects of London life might capitalize North London, South London, etc., while one mentioning the city merely in passing would be more likely to use north London and south London. Adjectives ending in -ern are sometimes used to distinguish purely geographical areas from regions seen in political or cultural terms: so

Kiswahili is the most important language of East Africa

but

Prickly acacia is found throughout eastern Africa

For treatment of foreign place names see 6.2.

5.6 Dates and periods

Capitalize the names of days, months, festivals, and holidays:

| Tuesday | March | Easter |

| Good Friday | Ramadan | Passover |

| Thanksgiving | Christmas Eve | the Fifth of November |

| New Year’s Day |

Names of the seasons are lower case, except where personified:

William went to Italy in the summer

O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being

Capitalize historical periods and geological time scales:

| the Devonian period | Early Minoan |

| the Upper Palaeozoic era | |

| the Bronze Age | |

| the Middle Ages (but the medieval period) | the Renaissance |

| the Dark Ages |

Modern periods are more likely to be lower case; check such instances with the New Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors:

the space age

the age of steam

the jazz age

the belle époque

Use lower case for millennia, centuries, and decades (see also 11.6):

| the first millennium | the sixteenth century | the sixties |

5.7 Events

Initial capitals are generally used for the formal names of wars, treaties, councils, assemblies, exhibitions, conferences, and competitions.

The following examples are indicative:

| the Crucifixion | the Inquisition |

| the Reformation | the Grand Tour |

| the Great Famine | the Boston Tea Party |

| the Gunpowder Plot | the Great Fire of London |

| the First World War | the Siege of Stalingrad |

| the Battle of Agincourt | the French Revolution |

| the Treaty of Versailles | the Triple Alliance |

| the Lateran Council | the Congress of Cambrai |

| the Indian and Colonial Exhibition | the One Thousand Guineas |

the Peninsular campaign

the Korean conflict

5.8 Legislation and official documents

The names of laws and official documents are generally capitalized:

| the Declaration of Independence | the Corn Laws |

Act is traditionally capitalized even in a non-specific reference; bill is lower case if it is not part of a name:

a bill banning unlicensed puppy farms

the Bill of Rights

the requirements of the Act

the Factory and Workshop Act 1911

For legal citations see Chapter 13.

5.9 Honours and awards

The full formal names of orders of chivalry, state awards, medals, degrees, prizes, and the like are usually capitalized, as are (in most styles) the ranks and grades of award:

the George Cross

Companion of the Order of the Bath

Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire

Bachelor of Music

Licentiate of the Royal Academy of Dancing

Fellow of the Royal Society

Nobel Prize for Physics

the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture

but

an Olympic gold medal

Honours relating to a non-English-speaking country usually appear with an initial capital but with all other words in lower case; ranks may be translated or given in the original language, but in either case are best set lower case:

grand officer/grand officier of the Légion dʼhonneur

5.10 Titles of office, rank, and relationship

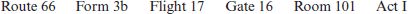

Words for titles and ranks are generally lower case unless they are used before a name, as a name, or in forms of address:

| Winston Churchill, the prime minister | Prime Minister Winston Churchill |

| he was elected prime minister | Yes, Prime Minister |

| the US president | President Obama |

| the king of England | King Henry |

| the queen of Castile | Queen Elizabeth |

| an assembly of cardinals | Cardinal Richelieu |

| the rank of a duke | the Duke of Wellington |

| a feudal lord | Lord Byron |

| a professor of physics | Professor Higgins |

| Miss Dunn, the head teacher | Head Teacher Alison Dunn |

| a Roman general | Good evening, General! |

Exceptions to this principle are some unique compound titles that have no non-specific meaning, which in many styles are capitalized in all contexts. Examples are:

| Advocate General | Attorney General |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | Chief Justice |

| Dalai Lama | Foreign Secretary |

| Governor General | Holy Roman Emperor |

| Home Secretary | Lord Chancellor |

| Prince of Wales | Princess Royal |

Regardless of their syntactic role, references to specific holders of a rank or title are often capitalized:

a letter from the Prime Minister

the Archbishop of Canterbury

Use of this style can lead to difficulties in contexts where titles of office appear frequently: in such cases it is generally clearer and more consistent to stick to the rule that the title of office is capitalized only when used before the office-holder’s name.

It is usual to capitalize the Pope and the reigning monarch (the King/Queen) but not all styles do. When it refers to Muhammad, the Prophet is capitalized (but note an Old Testament prophet). See also 5.11 for religious names.

Historians often impose minimal capitalization, particularly in contexts where the subjects of their writing bear titles: the duke of Somerset. This style can be distracting in works for a general readership.

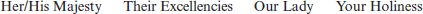

Capitalize possessive pronouns only when they form part of the titles of a holy person, or of a sovereign or other dignitary:

Personal pronouns referring to the sovereign are capitalized only in proclamations: We, Us, Our, Ours, Ourself, etc.

Words indicating family relationships are lower case unless used as part of a name or in an address:

| he did not look like his dad | Hello, Dad! |

| she has to help her mother | Maya tried to argue with Mother |

| ask your uncle | Uncle Brian |

5.11 Religious names and terms

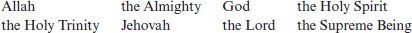

Use capitals for all references to the monotheistic deity:

Use lower case for pronouns referring to God where the reference is clear, unless the author specifies otherwise. In any event, write who, whom, whose in lower case. Capitalize God-awful and God-fearing but downcase godforsaken.

Use lower case for the gods and goddesses of polytheistic religions:

| the Aztec god of war | the goddess of the dawn |

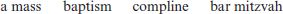

Capitalization of religious sacraments or rites in different religions (and contexts) is not uniform. Note, for example:

but

| the Mass | the Eucharist | Anointing of the Sick |

5.12 Personification

Personified entities and concepts are capitalized:

O Freedom, what liberties are taken in thy name!

If the Sun and Moon should doubt, they’d immediately go out

Ships and other craft are traditionally female Formerly, it was also conventional to use she of nations and cities in prose contexts, but this is old-fashioned, and the impersonal pronoun is now used:

he left the Titanic before she foundered on her maiden voyage

Britain decimalized its (not her) currency in 1971

The device is still found in poetic and literary writing:

And that sweet City with her dreaming spires

She needs not June for beauty’s heightening

The names of characters in a play who are identified by their occupation are capitalized in stage directions and references to the text (in the text their names would generally be in small capitals):

[First Murderer appears at the door]

5.13 People and languages

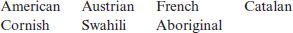

Adjectives and nouns denoting place, language, or indigenous people are capitalized:

Related verbs tend to retain the capital (Americanize, Frenchify, Hellenize), but note that anglicize and westernize are usually lower case.

As a very general rule, adjectives based on nationality tend to be capitalized where they are closely linked with the nationality or proper noun, and lower case where the association is remote or merely allusive. For example:

| Brussels sprouts | German measles | Irish setter |

| Turkish delight | Shetland pony | Michaelmas daisy |

| Afghan hound | Venetian red | Portuguese man-of-war |

but

| venetian blinds | morocco leather | italic script |

However, there are many exceptions, such as Arabic numbers, Chinese whispers, Dutch auction, French kissing, and Roman numerals, and any doubtful instances need to be checked in a dictionary. Caesarean (section) can take either an initial capital or (more commonly in medical texts) lower case.

Note that in many European languages adjectives of nationality are lower case: the English word ‘French’ translates as français in French and französisch in German. See Chapter 12.

5.14 Words derived from proper nouns

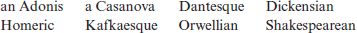

Capitals are used for a word derived from a personal name or other proper noun in contexts where the link with the noun is still felt to be alive:

Lower case is used in contexts where the association is remote, merely allusive, or a matter of convention:

| gargantuan | pasteurize | protean |

| quixotic | titanic | wellington boots |

Some words of this type can have both capitals and lower case in different contexts:

Bohemian (of central Europe) but bohemian (unconventional)

Philistine (of biblical people) but philistine (tastes)

Platonic (of philosophy) but platonic (love)

Stoic (of ancient philosophy) but stoic (impassive)

Retain the capital letter after a prefix and hyphen:

| pro-Nazi | anti-British | non-Catholic |

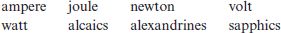

Use lower case for scientific units (see also 14.1.4) and poetic metres derived from names:

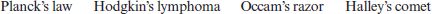

In compound terms for concepts such as scientific laws the personal name only is capitalized:

In medical texts, eponymic derivations may be downcased: Parkinson’s disease, parkinsonism, parkinsonian. See 14.3.6.

5.15 Trade names

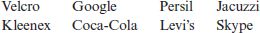

In general proprietary terms should be capitalized:

but write related verbs, for example to skype and to google, with a lower-case initial, although it is preferable to use generic verbs and nouns if possible (use a VoIP service, do an online search).

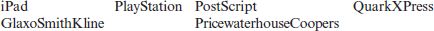

Some company and proprietary names use unusual configurations of upper- and lower-case letters; these should be followed:

5.16 Ships, aircraft, and vehicles

Capitalize names of ships and vehicles, using italics for individual names but not for types, models, or marques:

the Cutty Sark

HMS Hood

The Spirit of St Louis

a Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet

the Supermarine Spitfire Mk Ia

a Mini Cooper S

the International Space Station

the Curiosity Mars rover

It is worth noting that people serve in not on ships and the definite article is omitted when using the ship prefix (HMS, RRS, SS, etc.):

He went aboard HMS Victory not He went aboard the HMS Victory

5.17 Names including a number or letter

It is usual to capitalize names that include a number or letter: