CHAPTER 18

Bibliography

18.1 General principles

18.1.1 Introduction

Bibliography, specifically enumerative bibliography, is the discipline of citing reference matter in a consistent and accurate manner, so as to provide enough key material for readers to be able to identify the work and locate it in a library or a citation index (bibliographic database). Bibliographies occur in all types of publication, and are found in most non-fiction works (though depending on the type of publishing they may not be headed Bibliography—see 1.4.4).

The structure of bibliographic citations is determined by the referencing system in use in the publication concerned. In general publishing and academic publishing in the humanities, bibliographic citations are ordered (very broadly speaking):

author, title, place of publication, date of publication

This form supports the use of footnotes or endnotes for referencing (see 17.2). In these types of publishing the bibliographic list is likely to include works that are not referred to in the text.

Academic publishing in the sciences and social sciences uses author–date references in the text to source quotations and references to other authorities (see 17.3); this form requires bibliographic citations ordered:

author, date, title, place of publication

In these types of publishing the bibliographic list often includes only those works that are referred to in the text; the correct heading for such a list is not Bibliography but References.

A variation on the author–date system is the author–number system (see 17.4).

18.1.2 Placement within a publication

Citations are conventionally found in two different parts of an academic work:

In the interests of simplicity it is best to keep stylistic differences between note citations and bibliography citations to a minimum. The following distinctions are useful, however:

note citation

Joe Bailey, Pessimism (London, 1988), 35.

bibliography citation

Bailey, Joe, Pessimism (London, 1988).

Except when it is necessary to clarify a difference between the two types of citations, examples in this chapter follow bibliography style.

18.1.3 Arrangement and ordering of a bibliography

A bibliography is normally ordered alphabetically by the surname of the main author or editor of the cited work. It is sometimes advantageous to subdivide longer lists, for example by subject or type of work. A typical division is that of primary and secondary sources; also, a separate list of manuscripts and documents may be made. A bibliography of primary sources is sometimes more historically interesting if ordered chronologically, or more practical if arranged by repository. For ordering in the author–date system see 18.5.

Alphabetization follows the same principles as in indexing (see Chapter 19); ignore all accents (index Müller as Muller, not Mueller) and treat Mc as Mac and St as Saint. See 6.1.8 for the indexing of names with prefixes.

Single author

Entries by the same author may be ordered alphabetically by title, ignoring definite and indefinite articles, or chronologically by year, the earliest first, and alphabetically within a single year. Alphabetical order is advisable when many works by one author are cited, but chronological order may be preferred if it is important to show the sequence of works. In second and subsequent works by the same author do not replace the name with an em rule or rules: although this has been traditional print practice, it is not suitable for many types of electronic publication, so it is preferable to spell out the name in full for each entry.

Rogers, C. D., The Family Tree Detective (Manchester, 1983).

Rogers, C. D., Tracing Missing Persons (Manchester, 1986).

Works edited by an author are listed in a separate sequence following all works written by him or her, singly or with co-authors; works edited in collaboration are arranged according to the same rules as for multiple authors. Alternatively, it is possible to list all publications associated with a single person in a single sequence, ignoring the distinction between author and editor.

More than one author

It is usual to alphabetize works by more than one author under the first author’s name.

When there is more than one citation of the same author, group references within these two categories (see 18.5 for a more detailed discussion of bibliographic order):

Hornsby-Smith, Michael P., Roman Catholics in England: Studies in Social Structure since the Second World War (Cambridge, 1987).

Hornsby-Smith, Michael P., Roman Catholic Beliefs in England (Cambridge, 1991).

Hornsby-Smith, Michael P., and Dale, A., ‘Assimilation of Irish Immigrants’, British Journal of Sociology, xxxix/4 (1988), 519–44.

Hornsby-Smith, Michael P., and Lee, R. M., Roman Catholic Opinion (Guildford, 1979).

Hornsby-Smith, Michael P., Lee, R. M., and Turcan, K. A., ‘A Typology of English Catholics’, Sociological Review, xxx/3 (1982), 433–59.

18.1.4 Bibliographic elements

As a general rule, it is important for citations in a bibliography to be consistent in the level of detail provided. Inconsistency is a form of error and will not only reduce the overall integrity of an academic publication but may also prevent successful linking with citation indexes. Moreover, readers should be able to infer reliably that an absence of information from one citation but not another reflects the bibliographic detail available from the texts being cited.

For published matter, the key elements required for a ‘complete’ citation are:

Some citations require further details: these are covered in the various sections in this chapter. A decision to include other information (for example number of volumes, series title, publisher, or access dates) should be applied consistently to all citations where relevant.

All bibliographic information must be taken from the cited work itself, and not from a secondary source such as a library catalogue or other bibliography. Additional information not supplied by the work should generally appear within square brackets.

The means by which a reader distinguishes one element from the other is by its order within the citation, its typography, and its surrounding punctuation. It is therefore important to ensure that each part of the citation is presented correctly, and in the appropriate place.

For non-published material (so-called ‘grey’ literature), such as manuscripts, company reports, and some electronic sources, there are fewer established conventions, but efforts should be made to follow the style consistently using the general pattern applied to published matter (see also 18.6).

This is particularly important for automated XML tagging (see 2.1.1) because the process relies on the recognition of patterns in formatting and order of the elements. This can break down if the ‘rules’ for a particular citation system are not followed.

18.2 Books

18.2.1 Introduction

A complete book citation must include author or editor details, title, edition information (if an edition other than the first edition is cited), and date and place of publication:

Demaus, Robert, William Tyndale: A Contribution to the Early History of the English Bible, new edn, rev. Richard Lovett (London, 1886).

Watt, R. W., Three Steps to Victory (London, 1957).

Bagnold, Enid, A Diary Without Dates (2nd edn, London, 1978).

See 18.8 for ebook citations.

18.2.2 Author’s name

Some publishers, especially in the humanities, prefer to cite the author’s name as it appears on the title page (the same applies to all personal names, whether of authors or others); this is because some authors insist on being known by their initials while others object to their forenames being cut down. Applying this practice requires the author to exercise the discipline of noting the form as it appears in the book, and not relying on secondary sources, such as library catalogues and other bibliographies. A more pragmatic approach (often adopted in scientific publication ) is to systematically reduce forenames to initials, especially for multi-author works where different contributors may have adopted different practices.

The author’s name should appear at the start of the citation. In bibliography citations the surname is given first, followed by a comma and the given names or initials:

| Bailey, Joe | Eliot, T. S. |

In scientific works, initials and minimal punctuation are more usual in the reference list:

| Feynman R | Nurse PM |

See 17.3 for more details of punctuation of authors’ names.

Names that are best left unabbreviated and in natural order in bibliography citations include:

| Hereward the Wake | Aelred of Rievaulx |

| Dotted Crotchet | Afferbeck Lauder |

BBC

EA Games

IBM

In a list, such examples would all be ordered by their first element.

If works of one author are cited under different names, use the correct form for each work, and in humanities texts, supply a former name after a later one in parentheses, adding a cross-reference if necessary:

Joukovsky, F., Orphée et ses disciples dans la poésie française et néolatine du XVIe siècle (Geneva, 1970).

Joukovsky, F. (= Joukovsky-Micha, F.), ‘La Guerre des dieux et des géants chezles poètes français du XVIe siècle (1500–1585)’, Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance, xxix (1967), 55–92.

Unless the author’s preference is known to be otherwise, when citing naturalized names that include particles keep the particle with the surname only if it is capitalized. For foreign names follow the correct usage for the language or person in question:

| De Long, George Washington | Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von |

| Musset, Alfred de |

Titular prefixes (Sir, Revd, Dr, Captain, etc.) are not needed unless their removal would mislead:

Wood, Mrs Henry, East Lynne, 3 vols (London, 1861).

Two or more authors

With two or three authors (or editors), cite in the order that appears on the title page. Either the first cited name only, or all names before the title, may be inverted so that the surname appears first. Whichever style is chosen must be applied consistently:

King, Roy D., and Morgan, Rodney, A Taste of Prison (London, 1976).

King, Roy D., and Rodney Morgan, A Taste of Prison (London, 1976).

When there are four or more authors, works in the humanities usually cite the first name followed by ‘and others’ or ‘et al.’ (from Latin et alii ‘and others’; note that, depending on style, ‘et al.’ can appear in roman or italic type—consistency is important):

Stewart, Rosemary, and others, eds, Managing in Britain (London, 1994).

In some scientific journals, where it is not unusual for several names to be identified with an article or paper, the policy can be to cite up to six authors before reducing the list to a single name and ‘et al.’, either in roman or italic and sometimes dropping the full point.

Pseudonyms

Cite works published under a pseudonym that is an author’s literary name under that pseudonym:

Eliot, George, Middlemarch (New York, 1977).

Twain, Mark, A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court (Harmondsworth, 1971).

In some contexts it may be useful to add a writer’s pseudonym for clarification when a writer publishes under his or her real name:

Dodgson, C. L. [Lewis Carroll], Symbolic Logic (Oxford, 1896).

Conversely, an author known by his or her real name may need to be identified when he or she occasionally publishes under a pseudonym:

Afferbeck Lauder [Alistair Morrison], Let Stalk Strine (Sydney, 1965).

If the bibliography contains works under the author’s true name as well as a pseudonym, the alternative names may be included in both cases to expose the identification:

Coulange, P. [J. Turmel], The Life of the Devil, tr. S. H. Guest (London, 1929).

Turmel, J. [P. Coulange], ‘Histoire de l’angélologie du temps apostolique à la fin du Ve siècle’, Revue d’Histoire et de Littérature Religieuse, iii (1898), 299–308, 407–34, 533–52.

Anonymous

For texts where the author is not known, in bibliography citations Anon. or Anonymous may be used, with like works alphabetized accordingly:Anon., Stories after Nature (London, 1822).

Stories after Nature (London, 1822).

If the author’s name is not supplied by the book but is known from other sources, the name may be cited in square brackets:

[Balfour, James], Philosophical Essays (Edinburgh, 1768).

[Gibbon, John], Day-Fatality, or, Some Observations on Days Lucky and Unlucky (London, 1678; rev. edn 1686).

18.2.3 Editors, translators, and revisers

Special XML tagging elements are created for editors, translators, and compilers so it is important that they are identified as such.

In books comprising the edited works of a number of authors, or a collection of documents, essays, congress reports, etc., the editor’s name appears first followed by ed. (standing for ‘editor’; plural eds or eds.) before the book title:

Dibdin, Michael, ed., The Picador Book of Crime Writing (London, 1993).

Ashworth, A., ‘Belief, Intent, and Criminal Liability’, in J. Eekelaar and J. Bell, eds., Oxford Essays in Jurisprudence, 3rd ser. (1987), 6–25.

Bucknell, Katherine, and Nicholas Jenkins, eds, W. H. Auden, ‘The Map of All My Youth’: Early Works, Friends, and Influences (Oxford, 1990).

Some styles, including Oxford, insert ‘ed.’ and ‘eds’ within parentheses:

SAMPSON, RODNEY (ed.), Early Romance Texts: An Anthology (Cambridge, 1980).

Editors of literary texts (or of another author’s papers) are cited after the title; in this case ed. (standing for ‘edited by’) remains unchanged even if there is more than one editor:

Hume, David, A Treatise of Human Nature, ed. David Fate Norton and Mary J. Norton (Oxford, 2000).

For note citations, when an author is responsible for the content of the work but not the title (for example letters collected together posthumously), and the author’s name appears as part of that title, there is no need to repeat the author’s name at the start of the citation:

The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, ed. F. L. Jones (Oxford, 1964).

rather than

Shelley, Percy Bysshe, The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, ed. F. L. Jones (Oxford, 1964).

As with editors, translators and revisers are named after the title and are introduced respectively by tr. or trans. (‘translated by’), rev. (‘revised by’):

Albert Schweitzer, The Quest of the Historical Jesus, tr. William Montgomery (n.p., 1910).

Translators or revisers whose contribution is sufficiently substantial for them to count as joint authors are named after the original author.

18.2.4 Organization as author

In the absence of an author or editor, an organization acting in the role of author can be treated as such. Do not use ed. or tr. in these instances:

Amnesty International, Prisoners Without a Voice: Asylum Seekers in the United Kingdom (London, 1995).

18.2.5 Titles and subtitles

In general the treatment of titles in bibliography matches that of work titles mentioned in text (see Chapter 8). Always take the title from the title page of the work being cited, not the dust jacket or the cover of a paperback edition, and never alter spelling in order to conform to house style. Punctuation in long titles may be lightly edited for the sake of clarity.

Consider truncating long and superfluous subtitles, but not if that would significantly narrow the implied scope of a work. Subtitles are often identified as such on the title page by a line break or a change in font or font size; in a bibliography a subtitle is always divided from the title by a colon.

Capitalization

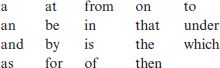

In most bibliographic styles traditional capitalization rules are applied to titles (see 8.2.3). In practice the choice between upper and lower case is usually instinctive, but will at least downcase the following:

Unless the exact form is of bibliographic or semantic relevance your primary guide should be to style a title sensibly and consistently throughout a work.

The Importance of Being Earnest: A Trivial Comedy for Serious People

Twenty Years After

Moby-Dick, or, The Whale

Capitalization of foreign titles follows the rules of the language (see Chapter 12); however, the treatment of the first word of a title, subtitle, or parallel title conforms to the style used for English-language titles.

Titles within titles

Titles within titles may be identified by quotation marks. Always capitalize the first word of the nested title; this capitalized word is regarded in some styles as sufficient to identify the subsidiary work:

Grigg, John, The History of ‘The Times’, vi (1993).

O’Conor, Roderick, A Sentimental Journey through ‘Finnegans Wake’, with a Map of the Liffey (Dublin, 1977).

Grigg, John, The History of The Times, vi (1993).

The convention of using roman instead of italic to identify nested titles is established but not recommended; see 7.6. For a further discussion of titles within titles see 8.2.8.

Foreign-language titles

Works should be cited in the form in which they were consulted by the author of the publication that cites them. If the work was consulted in the original foreign-language form, that should be cited as the primary reference; a published English translation may be added to the citation if that is deemed likely to be helpful to the reader:

J. Tschichold: Typographische Gestaltung (Basle, 1955); Eng. trans. as Asymmetric Typography (London, 1967).

Conversely, if a work was consulted in translation, that form should be cited; the original publication may also be included in the citation if that would be helpful (as it will be if the two forms of the title differ significantly):

R. Metz, A Hundred Years of British Philosophy, ed. J. H. Muirhead, trans. J. W. Harvey (1938) [Ger. orig., Die philosophischen Strömungen der Gegenwart in Grossbritannien (1935)]

When it is helpful to include a translation of a foreign-language title for information, the translation follows immediately after the title in roman, within square brackets; quotation marks are not necessary:

Nissan Motor Corporation, Nissan Jidosha 30nen shi [A 30-year history of Nissan Motors] (1965).

Care should be taken with consistency in capitalization in translations of this kind—some styles use essential capitals, others do not.

18.2.6 Chapters and essays in books

The chapter or essay title, which is generally enclosed in quotation marks and conforms to the surrounding capitalization style, is followed by a comma, the word in, and the details of the book. When citing a chapter from a single-author work there is no need to repeat the author’s details:

Ashton, John, ‘Dualism’, in Understanding the Fourth Gospel (Oxford, 1991), 205–37.

The placement of the editor’s name remains unaffected:

Shearman, John, ‘The Vatican Stanze: Functions and Decoration’, in George Holmes, ed., Art and Politics in Renaissance Italy: British Academy Lectures (Oxford, 1993), 185–240.

Quotation marks within chapter titles and essay titles become double quotation marks:

Malcolm, Noel, ‘The Austrian Invasion and the “Great Migration” of the Serbs, 1689–1690’, in Kosovo: A Short History (London, 1990), 139–62.

See 9.2 for more on quotation marks.

If an introduction or foreword has a specific title it can be styled as a chapter in a book; otherwise use introduction or foreword as a descriptor, without quotation marks:

Gill, Roma, introduction in The Complete Works of Christopher Marlow, 1 (Oxford, 1987; repr. 2001).

18.2.7 Volumes

A multi-volume book is a single work with a set structure. Informing readers of the number of volumes being cited is a useful convention that, if followed, must be applied consistently. The number of volumes is provided before the publication information, using an Arabic numeral. In references to a specific volume in a set, however, the number is usually styled in lower-case Roman numerals, although this style may vary: capital or small capital Roman numerals, or Arabic figures, may also be used.

There are two ways of citing a particular location in a multi-volume work: the entire work may be cited and the volume and page location given after the date(s) of publication; or the single relevant volume may be cited with its own date of publication, followed by the relevant page reference. Note in the examples below the use of Arabic and Roman numerals for different purposes:

Vander Straeten, Edmond, La Musique aux Pays-Bas avant le XIXe siècle, 8 vols (Brussels, 1867–88), ii, 367–8.

Vander Straeten, Edmond, La Musique aux Pays-Bas avant le XIXe sièclè, ii (Brussels, 1872), 367–8.

When the volumes of a multi-volume work have different titles, the form is:

Glorieux, P., Aux origines de la Sorbonne, i: Robert de Sorbon (Paris, 1966).

Ward, A. W. and A. E. Waller, eds, The Cambridge History of English Literature, xii: The Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, 1932), 43–56.

If only the volume title appears on the title page the overall title should still be included, either as directed above or within square brackets after the volume title:

David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America [vol. i of America: A Cultural History] (New York, 1989).

18.2.8 Series title

A series is a (possibly open-ended) collection of individual works. In book citations, a series title is optional but useful information. It always appears in roman type, fully capitalized, and before or within the parentheses that hold publication information. Most, but not all, series are numbered; the volume numbers in the series should follow the series title:

Stones, E. L. G., ed. and tr., Anglo-Scottish Relations, 1174–1328: Some Selected Documents, Oxford Medieval Texts (Oxford, 1970).

Dodgdon, J. McN., The Place-Names of Gloucestershire, 4 vols, English Place-Name Society, 38–41 (1964–5).

18.2.9 Place of publication

Publication details, including the place of publication, are usually inserted within parentheses. The place of publication should normally be given in its modern form, using the English form where one exists:

| The Hague (not Den Haag) | Munich (not München) |

| Turin (not Torino) |

Marchetto of Padua, Pomerium, ed. Giuseppe Vecchi (n.p., 1961).

18.2.10 Publisher

The publisher’s name is not generally regarded as essential information, but it may be included if desired; in the interests of consistency give names of all publishers or none at all. The preferred order is place of publication, publisher, and date, presented in parentheses thus:

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005)

Publishers’ names may be reduced to the shortest intelligible unit without shortening words (for example, Teubner instead of Druck und Verlag von B. G. Teubner), and terms such as Ltd, & Co., and plc can be omitted. University presses whose names derive from their location can be abbreviated (Oxford: OUP; Cambridge: CUP; etc.), providing this is done consistently. See 18.2.9 for guidance on place of publication.

18.2.11 Date

The use of parentheses around a date in a bibliographic citation implies publication. See 18.4 and 18.6 for dates of unpublished works. Always cite the date of the edition that has been consulted. This date is usually found on the title page or the copyright page; for older books it may appear only in the colophon, a publishing device added to the last page of the book. Dates given in Roman numerals should be rendered into Arabic numerals.

When no date of publication is listed, use the latest copyright date. When multiple dates are given ignore the dates of later printings and impressions, but when using a new or revised edition use that date. If no date can be found at all, use n.d. (‘no date’) instead. Alternatively, if the date is known from other sources, it can be supplied in square brackets:

C. F. Schreiber, A Note on Faust Translations (n.d. [c.1930])

Works published over a period of time require a date range:

Asloan, John, The Asloan Manuscript, ed. William A. Craigie, 2 vols (Edinburgh, 1923–5).

When the book or edition is still in progress, an open-ended date is indicated by an en rule:

W. Schneemelcher, Bibliographia Patristica (Berlin, 1959–).

Cite a book that is to be published in the future as ‘forthcoming’ or ‘in press’. Do not guess, or supply a projected publication date as these often prove inaccurate.

18.2.12 Editions

When citing an edition later than the first it is necessary to include some extra publication information, which is usually found either on the title page or in the colophon. This may be an edition number, such as 2nd edn, or something more descriptive (rev. edn, rev. and enl. edn).

Placement

It is not necessary to identify first editions as such but subsequent editions should be numbered in ordinal form: 2nd, 23rd. As a general rule, edition details should appear within parentheses, in front of any other publication information:

Baker, J. H., An Introduction to English Legal History (3rd edn, 1990).

Denniston, J. D., The Greek Particles (2nd edn, Oxford, 1954).

When the edition being cited is singularly identified with a named editor, translator, or reviser the editor’s name appears at the head of the citation; the edition number directly follows the title and is not placed inside the parentheses that contain the publication details. This establishes that earlier editions are not associated with that editor:

Knowles, Elizabeth, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, 5th edn (Oxford, 1999).

Citing more than one edition

Sometimes it is useful to include details of more than one edition. When this information is limited to publication details (edition, date and place of publication, and publisher) the information can remain within a single set of parentheses. When more information is needed (e.g. when a later edition has a different title and editor) it is clearer to close off the parentheses, insert a semi-colon, and continue:

Denniston, J. D., The Greek Particles (1934; 2nd edn, Oxford, 1954).

Denniston, J. D., The Greek Particles (Oxford, 1934; citations from 2nd edn, 1954).

Berkenhout, John, Outlines of the Natural History of Great Britain, 3 vols (London, 1769–72); rev. edn, as A Synopsis of the Natural History of Great Britain, 2 vols (London, 1789).

18.2.13 Reprints, reprint editions, and facsimiles

Reprint and facsimile editions are generally unchanged reproductions of the original book, perhaps with an added preface or index. It is always good practice to include the publication details of the original, especially the publication date if a significant period of time has elapsed between the edition and its reprint.

If the reprint has the same place of publication and publisher details as the original, these need not (though they may) be repeated. Best practice is to arrange the citation so that a reading from left to right follows the chronology of the work:

Gibbon, Edward, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, with introduction by Christopher Dawson, 6 vols (London, 1910; repr. 1974).

Allen, E., A Knack to Know a Knave (London, 1594; facs. edn, Oxford: Malone Society Reprints, 1963).

Joachim of Fiore, Psalterium decem cordarum (Venice, 1527; facs. edn, Frankfurt am Main, 1965).

Smith, Eliza, The Compleat Housewife, or, Accomplished Gentlewoman’s Companion (16th edn, London, 1758; facs. edn, London, 1994).

Reprints that include revisions can be described as such:

Southern, R. W., Saint Anselm: A Portrait in a Landscape (rev. repr., Cambridge, 1991).

Title change

A changed title should be included: the parentheses that hold details of the original publication are closed off and the reprint is described after a semicolon in the same fashion as for a later edition with an altered title (see above):

Hare, Cyril, When the Wind Blows (London, 1949); repr. as The Wind Blows Death (London, 1987).

Lower, Richard, Diatribæ Thomæ Willisii Doct. Med. & Profess. Oxon. De febribus Vindicatio adversus Edmundum De Meara Ormoniensem Hibernum M.D. (London, 1665); facs. edn with introduction, ed. and tr. Kenneth Dewhurst, as Richard Lower’s ‘Vindicatio’: A Defence of the Experimental Method (Oxford, 1983).

18.2.14 Translations

In a citation of a work in translation, the original author’s name comes first and the translator’s name after the title, prefixed by ‘tr.’ or ‘trans.’:

Bischoff, Bernhard, Latin Palaeography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages, tr. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín and David Ganz (Cambridge, 1990).

Martorell, Joanat, Tirant lo Blanc, tr. with foreword by David H. Rosenthal (London, 1984).

Details of the original edition may also be cited:

José Sarrau, Tapas y aperitivos (Madrid, 1975); tr. Francesca Piemonte Slesinger as Tapas and Appetizers (New York, 1987).

18.3 Articles in periodicals

18.3.1 Introduction

A complete periodical citation requires author or editor details that relate to the article being cited, the article title, the journal title, volume information, date, and page range:

Schutte, Anne Jacobson, ‘Irene di Spilimbergo: The Image of a Creative Woman in Late Renaissance Italy’, Renaissance Quarterly, 44 (1991), 42–61.

Authors’ and editors’ names in periodical citations are treated the same as those for books.

If a paper has been submitted for publication but has not yet been accepted, it should not be listed in the bibliography, as it may be rejected. Refer to the paper in the running text as unpublished, in submission, or submitted for publication. Personal communications should be referred to as such in the running text, and omitted from the bibliography. If a paper has been accepted for publication it can be cited in the end list as in press; do not guess the publication date. It is worth checking an online citation index to find out if works cited as in press have been published in the interim (particularly if not one of the author’s own sources); if so, complete the publication details.

18.3.2 Article titles

Titles of articles—whether English or foreign—may be given in roman within single quotation marks; in some academic works quotation marks are omitted altogether. Quotation marks within quoted matter become double quotation marks:

Halil Inalcik, ‘Comments on “Sultanism”: Max Weber’s Typification of the Ottoman Polity’, Princeton Papers in Near Eastern Studies, 1 (1992), 49–72.

Pollard, A. F. ‘The Authenticity of the “Lords’ Journals” in the Sixteenth Century’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 3rd ser., 8 (1914), 17–39.

Titles of journals, magazines, and newspapers appear in italic with maximal capitalization, regardless of language. If the title starts with a definite article this can be omitted, except when the title consists of the word The and only one other word:

Downing, Taylor and Andrew Johnston, ‘The Spitfire Legend’, History Today, 50/9 (2000), 19–25.

Drucker, Peter, ‘Really Reinventing Government’, Atlantic Monthly, 275/2 (1995), 49–61.

Greeley, A. W., ‘Will They Reach the Pole?’, McClure’s Magazine, 3/1 (1894), 39–44.

Henry James, ‘Miss Braddon’, The Nation (9 Nov. 1865).

See also 8.2.7.

18.3.3 Periodical volume numbers

Volume numbers are usually styled as Arabic numerals, but whatever you choose must be applied consistently: do not follow what is used by the journal itself.

Volumes usually span one academic or calendar year, but may occasionally cover a longer period of time. When a volume is published in issues or parts, some journals will separately paginate each issue, so that each new issue starts at page 1. Other publications paginate continuously through each volume, so that the first page number of a new issue continues from where the preceding issue left off. It is important to include issue numbers when citing separately paginated journals, because volume number and page number alone will not adequately guide a researcher to the appropriate location within the journal run. Although issue numbers are superfluous with continuously paginated journals, best practice is to include issue numbers nevertheless: the information is not in error, the citation remains consistent with neighbouring journal citations, and in formulating the citation there is no need for you to determine which pagination system the journal follows at any given time (some journals switch from one system to another over the history of their publication).

Part or issue numbers follow the volume number after a solidus:

Neale, Steve, ‘Masculinity as Spectacle’, Screen, 24/6 (1983), 2–12.

Garvin, David A., ‘Japanese Quality Management’, Columbia Journal of World Business, 19/3 (1984), 3–12.

Magazines and newspapers are often identified (and catalogued) by their date, rather than a volume number:

Lee, Alan, ‘England Haunted by Familiar Failings’, The Times (23 June 1995).

Putterman, Seth J., ‘Sonoluminescence: Sound into Light’, Scientific American (Feb. 1995), 32–7.

Some publishing houses prefer to distinguish magazine and newspaper publications from academic journals by not inserting the date between parentheses:

Blackburn, Roderic H., ‘Historic Towns: Restorations in the Dutch Settlement of Kinderhook’, Antiques, Dec. 1972, 1068–72.

Always follow the form used on the periodical itself: if the issue is designated Fall, do not change this to Autumn, nor attempt to adjust the season for the benefit of readers in another hemisphere, as the season forms part of the work’s description and is not an ad hoc designation.

Series

Where there are several series of a journal the series information should appear before the volume number:

Moody, T. W., ‘Michael Davitt and the British Labour Movement, 1882–1906’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th ser., 3 (1953), 53–76.

New series can be abbreviated either to ‘new ser.’ or NS in small capitals. Avoid OS, which can mean either ‘original’ or ‘old’ series:

Barnes, J., ‘Homonymy in Aristotle and Speusippus’, Classical Quarterly, new ser., 21 (1971), 65–80.

Barnes, J., ‘Homonymy in Aristotle and Speusippus’, Classical

Quarterly, NS 21 (1971), 65–80.

18.3.4 Page numbers

As with chapters and essays in books, it is customary to end the citation with a page range showing the extent of a periodical article. This is particularly important when a through-paginated journal is cited without issue numbers, as it aids the reader in finding the article in a volume that has no single contents page. The page extent is also useful as an indicator of the scale and importance of the article. Whether or not to elide page ranges is a matter of house style; see 11.1.4 for guidance.

18.3.5 Reviews

Reviews are listed under the name of the reviewer; the place of publication and date of the book reviewed are helpful but not mandatory:

Ames-Lewis, F., review of Ronald Lightbown, Mantegna (Oxford, 1986), in Renaissance Studies, 1 (1987), 273–9.

If the review has a different title, cite that, followed by the name of the author and title of the book reviewed:

Porter, Roy, ‘Lion of the Laboratory’, review of Gerald L. Geison, The Private Science of Louis Pasteur (Princeton, 1995), in TLS (16 June 1995), 3–4.

18.4 Theses and dissertations

Citations of theses and dissertations should include the degree for which they were submitted, and the full name of the institution as indicated on the title page. Titles should be printed in roman within single quotation marks. The terms dissertation and thesis, as well as DPhil and PhD, are not interchangeable; use whichever appears on the title page of the work itself. The date should be that of submission; it should preferably not be placed within parentheses:

Hill, Daniel, ‘Divinity and Maximal Greatness’, PhD thesis, King’s College, London, 2001.

Universities and institutions must always be cited using their full, official form, so as to avoid potential confusion between similar-sounding names (for example Washington University and University of Washington).

18.5 Citations to support author–date referencing

As explained in 18.1.1 and in Chapter 17, where the author–date referencing method is in use, bibliographic citations are reconfigured so that the publication date appears at the head after the author’s name (this is the formula that the reader, trying to trace a work referenced in the text, will seek):

Lakoff, R. (1975). Language and Women’s Place. New York: Harper and Row.

A reference list in this system is ordered:

Author–date references in the text must be able to identify each work uniquely by means of the author’s surname and date of publication alone. Where more than one work by a particular author or authors is published in a single year, it follows that some further identifier is needed to distinguish them. In this case the dates of publication are supplemented by lower-case letters, which are used in the in-text references:

Lyons, J. (1981a), Language and Linguistics: An Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Lyons, J. (1981b), Language, Meaning and Context (London: Fontana Paperbacks).

The letters are allocated according to the order in the reference list.

18.6 Manuscript and other documentary sources

18.6.1 Introduction

For non-published documentary sources that have been digitized, see 18.6.6 and 18.8.

Conventions for citing physical manuscripts and archival material are less well established than those for published works, partly because it is often necessary to formulate citations in a way that addresses the qualities and subject matter of the particular material at hand. When establishing how best to order and describe manuscript sources ensure that each citation:

The different elements that constitute a manuscript citation will normally fall into one of two categories:

Treat author details as for book details (see 18.2.2).

18.6.2 Titles and descriptors

When a manuscript has a distinct title it should be cited in roman, in single quotes. General descriptors appear in roman only, and usually take a lower-case initial:

Chaundler, Thomas, ‘Collocutiones’, Balliol College, Oxford, MS 288.

exchequer accounts, Dec. 1798, Cheshire Record Office, E311.

Depending on the readership and function of the bibliography, descriptors are not always necessary; sometimes a shelf mark is enough for an informed reader to comprehend the general nature of what is being cited. For example, in a specialist historical text it may be sufficient to provide piece numbers for documents in the National Archives without naming the collection to which they belong:

| PRO, FO 363 | PRO, SP 16/173, fo. 48 |

18.6.3 Dates

Dates follow description details and are not enclosed in parentheses:

Smith, Francis, travel diaries, 1912–17, British Library, Add. MS 23116.

Bearsden Ladies’ Club minutes, 12 June 1949, Bearsden and Milngavie District Libraries, box 19/d.

18.6.4 Repository information

The level of information required to identify the place accurately will depend upon the stylistic conventions of the work in which the citation occurs, the anticipated readership of the publication, and the size and general accessibility of the repository being cited. Repositories of national collections and archives may not require a country or city as part of the address. Some repositories include enough information within their name to render further address details otiose. If one particular repository is to be cited many times, consider creating an abbreviation that can be used in its place, with a key at the top of the bibliography, or group like citations together as a subdivision within the list.

In English-language publications names of repositories are always roman with upper-case initials, regardless of the conventions applied in the language of the country of origin:

Bibliothèque Municipale, Valenciennes, MS 393

Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, cod. II.II.289

18.6.5 Location details

Any peculiarities of foliation or cataloguing must be faithfully rendered: a unique source is permitted a unique reference, if that is how the archive stores and retrieves it. For archives in non-English-speaking countries, retain in the original language everything—however unfamiliar—except the name of the city. Multiple shelf-mark numbers or other numerical identifiers should not be elided:

Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Rawlinson D. 520, fol. 7

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS fonds français 146

Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague, handschriften 34C18, 72D32/4

18.6.6 Grey literature

Grey literature is defined as ‘manifold document types produced on all levels of government, academics, business and industry in print and electronic formats that are protected by intellectual property rights, of sufficient quality to be collected and preserved by library holdings or institutional repositories, but not controlled by commercial publishers i.e., where publishing is not the primary activity of the producing body’.

Such non-published material includes reports by companies, ministries, or research teams, theses (see 18.4), newsletters, technical notes, product catalogues, presentations, personal communications, working papers, academic courseware, and much more. Although there are fewer established conventions, efforts should be made to follow the style consistently using the general pattern applied to published matter, so that valid XML tagging can ensure that citation indexes will successfully acquire, analyse, and disseminate the information correctly.

18.7 Audio and audiovisual materials

18.7.1 Introduction

For broadcasts and recordings the ordering of elements within a citation may differ according to the content of the recording or the purpose for which it is cited: sound recordings, for example, might be best listed under the name of the conductor, the name of the composer, or even the name of the ensemble. As with all citations, sufficient information should be given to enable the reader to understand what type of work it is, and how to find it.

18.7.2 Audio recordings

Essential elements to include are title (see 8.5 for typographical treatment of titles), recording company and catalogue number, and, if available, date of issue or copyright. Other useful information includes details of performers and composers, specific track information, recording date (especially if significantly different from date of issue), authorship and title of any sleeve notes that accompany the recording, and the exact type of recording (e.g. wax cylinder, 78 rpm, compact disc, audio file format), and a Uniform Resource Indicator (URI) if accessed online. The following examples show an appropriate style for presenting such information:

Carter, Elliott, The Four String Quartets, Juilliard String Quartet (Sony S2K 47229, 1991).

Davis, Miles, and others, ‘So What’, in Kind of Blue, rec. 1959 (Columbia CK 64935, 1997) [CD].

Vitry, Philippe de, Philippe de Vitry and the Ars Nova, Orlando Consort (Amon Ra CD-SAR 49, 1991) [incl. sleeve notes by Daniel Leech-Wilkinson, ‘Philippe de Vitry and the 14th-Century Motet’].

Audio recordings that combine different works without a clear single title may require more than one title:

Dutilleux, Henri, L’Arbre des songes, and Peter Maxwell Davies, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, André Previn, cond., Isaac Stern, violin, and Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (CBS MK 42449, 1987).

In recording numbers a hyphen rather than an en rule is the norm. Where a range of such numbers is given they should never be elided:

Lightnin’ Hopkins, The Complete Aladdin Recordings (EMI Blues Series CDP-7-96843-2, n.d.) [2-vol. CD set].

18.7.3 Films, videos, and broadcasts

See also 18.3. When citing audiovisual, video, and broadcast media, the three key elements that need to be included are:

| The Empire Strikes Back | ‘How to Play Women’s Lacrosse’ |

| interview with Albert Einstein |

If the citation is of a digital version of a pre-digital film or broadcast, include details of the original work, the source type (video etc.), date of post, and URI.

‘Tony Hancock Face to Face interview 01’ with John Freeman [video], YouTube (televised by the BBC 7 February 1960, uploaded 17 March 2009), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lnkovGeASzE

Podcasts can be treated similarly:

Fay Weldon, interview with Kirsty Young, Desert Island Discs Archive [podcast], BBC Radio 4 (9 May 2010), http://www.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/series/dida05/all.

18.8 Websites and other digital media

18.8.1 General principles

The basic template for citing digital references might include some, or all, of the following classes of information (not always necessarily in this order):

Examples of specific digital citations are presented in 18.8.5.

Electronic books, journals, magazines, newspapers, and reviews should be treated as much as possible like their print counterparts, with the same style adopted for capitalization, italics, and quotation marks. It is sometimes less straightforward to fit the pertinent information into the categories normally associated with print publications, such as author, title, place and date of publication, and publisher. Aspects such as pagination and publication date may differ between hard-copy and digital versions, so the reference must make clear which is meant.

Where print versions exist they can—but need not—be cited; similarly, citing digital versions of printed media is not mandatory. To provide the reader with both does, however, offer all possible options for following up a reference. When making citations for references with more than one online source, choose the one that is most likely to be stable and durable.

18.8.2 Media

Where the context or content of a citation does not make obvious the format or platform in which the data are held, give additional clarification (typically in square brackets):

| [DVD] | [blog] | [abstract] |

There is no need to add online or available from to the citation, since this will be apparent from the inclusion of an address.

18.8.3 Resource locators

URLs are unreliable as a medium- to long-term source locator for various reasons and some house styles preclude them from references. However, even if a web page no longer exists, the URL still constitutes a historical source if it is provided with a date of access (presumably, it existed at a point in the past, when the author accessed it), and there may not be an alternative source for the information.

If citing the whole of a document that consists of a series of linked pages, give the highest-level URL; this is most often the contents or home page. Give enough information to allow the reader to navigate to the exact reference. Many sites provide a search facility and regularly archive material; the search function will provide the surest method of reaching the destination if the document is relocated.

The protocol http is commonly omitted for websites that include www in the domain name as the browser will automatically insert it, and it is becoming more common to omit www as well; however, other protocols exist, such as ftp and the encrypted variant https, so if there is any risk of confusion, include the protocols for all.

It is also good practice to include the trailing forward slash (which points to a resource on the website) after the domain name (http://www.royal.gov.uk/).

It is not advisable to enclose a URL in angle brackets because it can interfere with XML tagging. Do not add underline formatting to URLs in word processor files. Normal punctuation can be used after a URL:

The British Armorial Bindings database, begun by John Morris and continued by Philip Oldfield, is now available on the Web at http://armorial.library.utoronto.ca/.

If citing a long URL is unavoidable, never hyphenate the address at a line break, or at hyphens. Divide URLs only after a solidus or a %; where this is impossible, break the URL before a punctuation mark, carrying it over to the following line. Where space allows, setting a URL on a separate line can prevent those of moderate length from being broken.

18.8.4 Access information

Up to four dates can be significant in providing a complete citation for an electronic source:

It is rarely necessary to include more than two of the above dates, and usually the access date, and maybe the last updated date, will suffice.

18.8.5 Types of digital citation

Depending on their importance, some Internet material (e.g. a passing reference to a tweet, a Facebook update, or an image) may simply be referred to in passing in the text or in notes, rather than included as a reference in the bibliography. Full details should be provided in a footnote or endnote. The principles remain the same as for a reference, except that the first name of the author/originator is not reversed as it is in a bibliographical reference.

Print publication available online

UNESCO, The United Nations World Water Development Report 4, vol. 1: Managing Water under Uncertainty and Risk (Paris: UNESCO, 2012), http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002156/215644e.pdf, accessed 9 Nov. 2013.

Online journal article

Druin, A., ‘The Role of Children in the Design of New Technology’, Behaviour & Information Technology, 21/1 (2002), 1–25. doi: 10.1080/01449290110108659

Liu, Ya-Ming, Yea-Huei Kao Yang, and Chee-Ruey Hsieh, ‘Regulation and Competition in the Taiwanese Pharmaceutical Market under National Health Insurance’, Journal of Health Economics, 31 (2012), 471–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.03.003

Article in a database

Li, Shu, Chungkun Shih, Chen Wang, Hong Pang, and Dong Ren, ‘Forever Love: The Hitherto Earliest Record of Copulating Insects from the Middle Jurassic of China’, PLoS ONE, 8/11 (2013), e78188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078188

News report

BBC News, ‘Colchester General Hospital: Police Probe Cancer Treatment’ (5 Nov. 2013), http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-essex-24819973, accessed 5 Nov. 2013.

BBC News, ‘Inside India’s Mars Mission HQ’ [video] (5 Nov. 2013), http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-24826253, accessed 5 Nov. 2013.

Hooper, Richard, ‘Lebanon’s Forgotten Space Programme’, BBC News Magazine (14 Nov. 2013), http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-24735423, accessed 14 Nov. 2013.

Interview

McEwen, Stephen, ‘Tan Twan Eng Interview: “I Have No Alternative but to Write in English”’, The Spectator (20 May 2013), http://blogs.spectator.co.uk/books/2013/05/tan-twan-eng-interview-i-have-no-alternative-but-to-write-in-english/, accessed 9 Nov. 2013.

Online book

Beckford, William, Vathek, 4th edn (London, 1823) [online facsimile], http://beckford.c18.net/wbvathek1823.html, accessed 5 Nov. 2013.

Online article

Allaby, Michael, ‘Feathers and Lava Lamps’, Oxford Reference (2013), http://www.oxfordreference.com/page/featherslavalamps, accessed 9 Nov. 2013.

Online reference

‘Gunpowder Plot’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/249505/Gunpowder-Plot, accessed 5 Nov. 2013.

Wikipedia article

‘Oxford University Press’, Wikipedia (last modified 5 Nov. 2013), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxford_University_Press, accessed 5 Nov. 2013.

Blog

Tan, Siu-Lan, ‘Why does this Baby Cry when her Mother Sings?’ [including video], OUPblog (5 Nov. 2013), http://blog.oup.com/2013/11/why-does-this-baby-cry-when-her-mother-sings-viral-video/, accessed 9 Nov. 2013.

Television programme

Berger, John, Episode 1, Ways of Seeing, BBC (1972), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pDE4VX_9Kk, accessed 9 Nov. 2013.

Online video

Nicholson, Christie, ‘A Quirk of Speech May Become a New Vocal Style’ [video], Scientific American, 17 Dec. 2011, http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode.cfm?id=a-quirk-of-speech-may-become-a-new-11-12-17, accessed 4 Nov. 2013.

Webcast

Yousafzai, Malala, ‘Making a Wish for Action on Global Education: Malala Yousafzai addresses Youth Assembly at UN on her 16th Birthday, 12 July 2013’ [webcast], UN Web TV, 12 Jul 2013, http://webtv.un.org/search/malala-yousafzai-un-youth-assembly/2542094251001?term=malala, accessed 15 Feb. 2015.

YouTube video

Arthur Rubinstein, ‘Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 18, I Moderato. Allegro (Fritz Reiner)’ [video], YouTube (recorded 9 Jan. 1956, uploaded 8 Nov. 2011), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Vv0Sy9FJrc&list=PLDB11C4F39E09047F, accessed 9 Nov. 2013.

Online image

M. Clarke, ‘Exports of Coal to the IFS’ [poster], Manchester Art Gallery, http://www.manchestergalleries.org/the-collections/search-the-collection/display.php?EMUSESSID=70bd7f1a388d79a82f52ea9aae713ef2&irn=4128, accessed 5 Nov. 2013.

‘Christ the God Shepherd’, stained glass window, Church of St Erfyl, Llanerfyl, Powys, Imaging the Bible in Wales Database, http://imagingthebible.llgc.org.uk//object/1884, accessed 10 Nov. 2013.

Podcast

Grayson Perry, ‘I Found Myself in the Art World’ [podcast], Reith Lecture (5 Nov. 2013), BBC Radio 4, http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/radio4/reith/reith_20131105-0940b.mp3, accessed 5 Nov. 2013.

The speaker’s name may be replaced with that of a writer or producer, depending on the podcast.

Facebook post/update

Barack Obama, ‘Tomorrow is Veterans Day’ [Facebook post] (10 Nov. 2013), https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10151936988101749&set=a.53081056748.66806.6815841748&type=1&theatre, accessed 13 Nov. 2013.

John Harvey, ‘ “These are a Few of My Favourite Things”, No. 28’ [Facebook post] (13 Nov. 2013), https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=229786530530896&set=a.108896335953250.15125.100004986510149&type=1&theatre, accessed 13 Nov. 2013.

If there is no obvious ‘heading’ that can be used in place of a title for the post, it can simply be described as a ‘[Facebook post]’.

Twitter post/tweet

Shakespeare’s Globe, ‘On this day in 1611 first production of The Tempest was performed by King’s Men at Whitehall Palace before James I’ [Twitter post], 5.48 a.m., 1 Nov. 2013, https://twitter.com/The_Globe/status/396257422928400385, accessed 5 Nov. 2013.

The date and time of messages are always those of the reader’s time zone, as it may not be possible to determine the exact date and time a tweet was posted. The tweet itself may be omitted and replaced with the description ‘Twitter feed’, ‘Twitter post’, or ‘tweet’. If the tweeter is a named or known individual, the tweet can also be listed under his/her real name followed by the username in parentheses, or vice versa.

Ebook

Rankin, Ian, Saints of the Shadow Bible [Kindle edn] (London: Orion, 2013).

or

Rankin, Ian, Saints of the Shadow Bible (Kindle edn, London: Orion, 2013).

Austen, Jane, Persuasion, ed. Gillian Beer (London: Penguin, 2003; Kindle edn, 2006).

The pagination of an ebook is not always fixed; hence reference is best made to a chapter or section rather than a page number. Some ebook editions provide print page numbers to facilitate referencing. Avoid device-specific indicators such as Kindle location numbers. As with any resource that is relatively new, citation styles vary and will probably change fairly quickly, as the technology continues to evolve. The last example above includes the publication details of the print as well as the ebook version. Some styles (not Oxford) suggest including the device on which it is read, the database from which it has been downloaded, and the date of the download.

Mobile app

Simogo, Device 6 (version 1.1) [mobile application for iPhone and iPad], downloaded 9 Nov. 2013.

Eliot, T. S., The Waste Land (version 1.1.1) [mobile application for iPad] (London: Touch Press, 2013), downloaded 9 Nov. 2013.

Some styles also include the web address of the download site.

CD-ROM/DVD

United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision [CD-ROM] (New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2011).