Islamic and Persian Gardens

In the 7th and 8th centuries Arab Muslims from southern Arabia spread the Islamic faith over large swathes of Christian Byzantium and the resurgent Persian Empire in the East (that had been ruled by the Sassanian Dynasty). The Sassanid Persian Empire was replaced with the Islamic Umayyad caliphate. The Islamic Empire soon extended from central Asia to the Atlantic. Therefore evidence for early Islamic gardens is stretched over several countries in the West as well as in the East.

Early Islamic gardens in the East

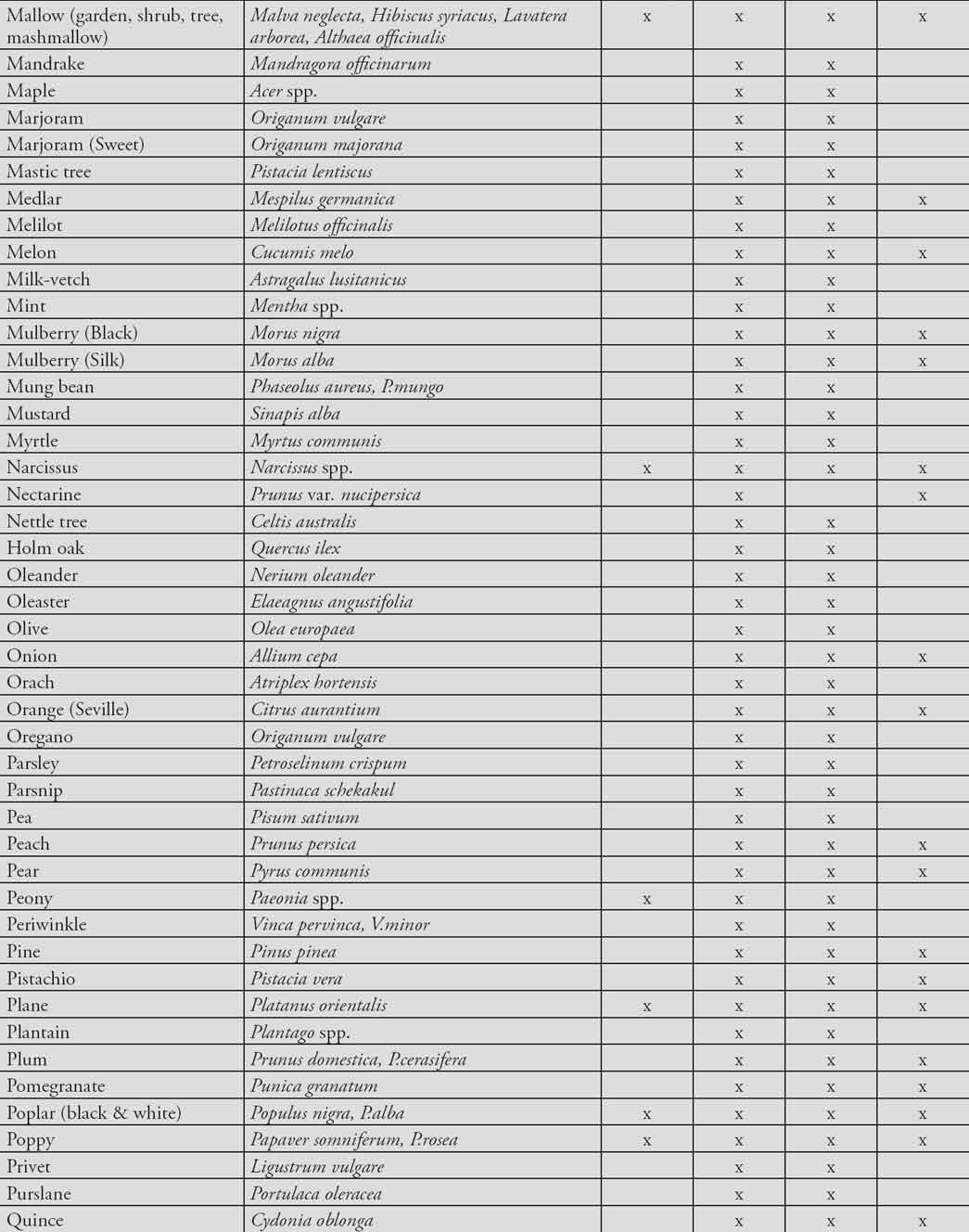

Damascus, in Syria, was made the first Islamic political capital; it was a city surrounded by desert but its springs irrigated palm groves and gardens that were much admired. These gardens may be the inspiration for the beautiful paradise mosaics adorning the walls of the large forecourt of the Umayyad mosque (dated to 705–715). The mosaics depict a wonderful idealised landscape with buildings, pavilions, bridges over streams, fountains and an abundance of trees (including a citron). These mosaics are often thought to have similarities with those of Byzantium, and the new Islamic rulers would have made use of whatever skilled craftsmen they could find, whether Christian or Muslim. These mosaics are one of the earliest depictions of an idealised Islamic garden.

The mosaics at the unfinished Umayyad palace built c.724–743 at Khirbet al-Mafjar, 2 km north of Jericho, are also of interest because, although most of its mosaics were of geometric designs, an apse of one room was decorated with a skilful composition comprising a lion and deer under the canopy of a large tree, recalling a paradeisos hunting park. The depiction of images (in human form) were officially banned in 721, but an alternative was to have the geometric patterns or to depict nature, often in the form of trees and flowers. Interestingly though, near life-size human figures in plaster were recovered from the entrance passage to this palace. Although the palace has been excavated not much is known about its gardens, beyond that one courtyard was constructed in the form of a Roman peristyle. A possible garden nearby contained a large elaborate square fountain pool with an octagonal pavilion in the centre.1 With water all around, it would have provided a refreshingly cool resting place in high summer. Gardens were seen as a welcoming area of retreat.

FIGURE 129. Paradise as a garden, in mosaics around the courtyard of the Umayyad mosque Damascus, AD 705–715.

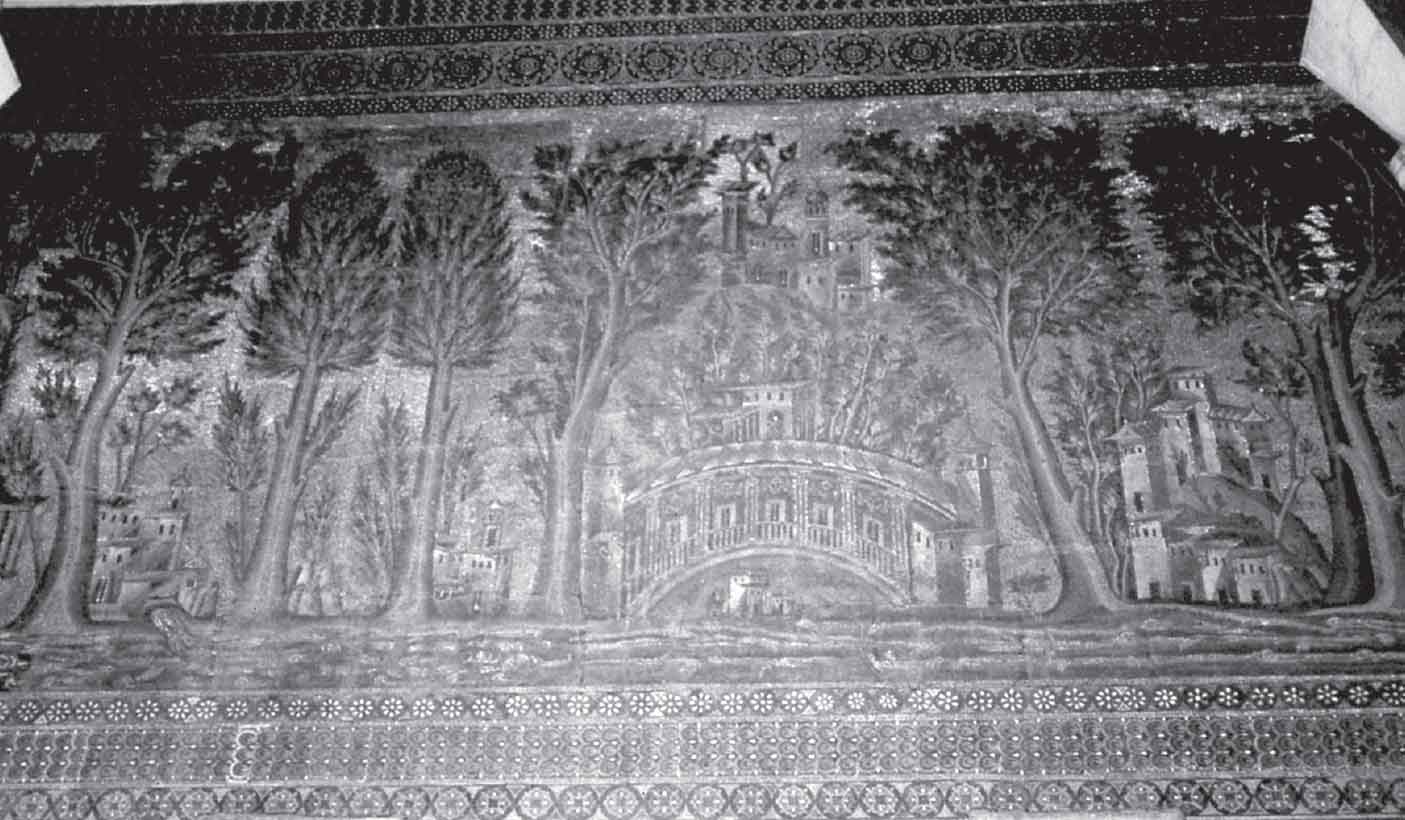

The Umayyads were succeeded by the Abbasids, a dynasty based in Baghdad. In 849 they built a new palace at Samarra (Iraq) close to the Tigris River. The Bulkawara Palace is one of the earliest known Islamic palaces and the largest ever constructed, it covered 1.33 km2. Its plan has survived almost unaltered because it was abandoned during another dynastic squabble about 50 years after it was built. The plan reveals numerous garden areas and the proximity of this great river ensured that they could be well irrigated. Arab sources mention that plants for these gardens were imported from all corners of their territories. The main gardens of the palace were designed as a series of three large rectangular intercommunicating areas. The archaeologist who excavated this site interpreted the areas as gardens with pathways in each section that had been laid out in a cross pattern which effectively divided each garden into four compartments.2 This was to become a standard plan of the Islamic Persian style of garden, called a chahār bāgh (which means four gardens).

The Chahār Bāgh and other names for gardens

Bāgh is the Persian word for garden, and a garden plant bed was called a bāghca. The chahār denotes that it was divided into four parts, usually by pathways, one running down the centre of the garden and the other bisecting it half way down, thus creating the four elements of the iconic Islamic garden. However, as we have seen, its origin goes back further in time. The classic four-part garden had been used at times by the Romans, but the design dates back even further for it was noted at the ancient Persian Palace of Cyrus at Pasargadae in 546 BC. Later this simple garden layout was further enhanced with water features. There were several different forms of bāgh. We hear of a Chenār Bāgh, the chenār is the oriental plane so these large shade trees in this type of garden would be ideal for a picnic under their wide canopy. Another form of garden was the Gul Bāgh which means a rose garden, in this period roses retain their position as the most favoured of all flowers. The first rose was said to have formed from the beads of perspiration from the prophet’s brow.

In the Islamic holy book, the Koran, the Arabic word used for a garden was janna (pl. jinān); and this word was also used to imply ‘Paradise’ which everyone aspired to reach. Their paradise was like the earlier Paradeisos, it was effectively a garden. They envisaged the garden containing two fountains and date palms, pomegranates and other fruit trees, as well as beautiful maidens. The Koranic Paradise garden had rivers flowing through them, four rivers were named,3 the number four could be linked to the idea of a four-part garden, and the chahār bāgh would be perhaps a realisation of this concept. There are similarities between the Jewish and Christian concepts of Eden and Heaven, as both have the four rivers of Paradise flowing out of Eden. Islam absorbed many ideas from civilisations current at that time, and this is an example of the continuity of imagery. A quotation from the Koran also includes more decorative elements within their Paradise garden:

It is He who grew the gardens, trellised and bowered, and palm trees and land sown with corn and many other seeds, and olives, and pomegranates, alike and yet unalike. So eat of their fruit when they are in fruit, and give on the day of harvesting …4

Besides the four gardens of Paradise, Muslims have ‘Seven Heavens’ (seven levels of paradise). The Persian word for paradise is bihesht, and interestingly some Persians decided to name their own garden ‘Hasht Bihesht’, which means ‘the eighth paradise’. Scholars and poets liked to make comparisons between earthly gardens and the heavenly paradise promised by the Koran, so these garden owners were likening their own garden to a paradise on earth, making it an eighth paradise. As the supreme model the poets took the Garden of Eram (or Iram). This legendary garden was built in Yemen by Shaddad to rival paradise in splendour, but it brought divine retribution on the patron for being too presumptuous. The moral in this tale was that it was alright to compare your garden with that of paradise, but take care because anything made by man cannot equal, or excel, that created by God.

Most of the terminology for Islamic gardens is either Arabic or derived from Persian, so we also hear of a bustan (an Arabic term) which was an orchard or grove, this replaced both the old Persian pairidaeza and Greek word paradeisos but was still in effect a verdant walled enclosure. The bustan would contain not only a variety of fruit trees, but also shade trees to allow plants to grow below in dappled light rather than be burnt by the fierce relentless sun of summer. Some of these trees were also selected because they were known to be good for timber, as mentioned by Islamic agriculturalists.

FIGURE 130. Abbasid Palace beside the River Tigris, Samarra (Iraq). A series of interconnecting gardens was designed so that paths formed four garden compartments, a chahar bagh, AD 849.

Agriculturalists, gardeners and botanists

A gardener in the Islamic world was called a bāghbān. Several rose to become well regarded in their profession. In Spain, Abū’l-Khayr was noted as ‘the tree planter’ who worked in the royal gardens of al-Mu’tamid at Seville (c.1085–1100). While based in Seville Abū’l-Khayr wrote a book on agriculture that included sections on horticulture.

Six other agricultural treatises were produced in Moorish Spain these were by: Ibn Wāfid, Ahmed Ibn Hajjaj in Seville (c.1074); Ibn Bassāl in Toledo (c.1074–1085); Al-Tighnarī in Granada (c.1107–1110); Ibn al-Awwām wrote the celebrated Book of Agriculture in Seville (c.1180); and c.1348 Ibn Luyūn from Almeria wrote a treatise that was later dubbed ‘the Andalusian Georgics’ when it was recently translated from the Arabic into Spanish. In these great works we notice that the number of plant species mentioned increases over the centuries, and by 1348 we learn that there were around 160 species growing in the gardens of Moorish Spain. The agriculturalists elevated the study of plants to a science, they were given a special name shajjar, and we hear that botanists (nabati) were employed with a shajjar in princely entourages.

Famous Islamic botanists working in Spain were: Ali Ibn Farah, also known as Al-Shafran (12th century) working in Guadix, Abu Ja’far Al-Ghafiqi (d. 1165); Al-Rumiyya (d. 1240) and Ibn Al-Baytar of Malaga (d. 1248).5 These botanists were also concerned with pharmacology, and Baytar went on to write a book on herbs and introduced many new drugs. Apparently as early as c. 756–788 a botanical garden was created in Al-Andalus for Al-Rahman the first, in the grounds of his palace of Al-Rusafa. He wanted this garden to be stocked with plants that were familiar to him from his eastern homeland, so he sent two gardeners as ambassadors to Syria, Yazid and Safar, to bring back seeds and precious seedlings.6 Safar was known for developing pomegranates in Islamic Spain. We even hear that a 9th-century emissary from Cordoba was sent to Byzantine Constantinople to smuggle out a special variety of fig that they wanted.7 Botanical gardens and nursery beds were created to try to acclimatise and naturalise a range of plant species new to Spain (plants and seeds were sought from Syria, Persia and north Africa). After time these were propagated and disseminated throughout the western Islamic world, and ultimately to medieval Europe.

In Persia Rashīd al-Dīn who worked in Yazd and Tabriz was noted for his advice on arboriculture which was included in his agricultural manual the Āthar wa ahyā’ (c.1310). Chapters 8–11 are of particular interest because they concern gardens and horticultural practises. He also included information on plants and practises from distant countries: within central Asia, India, and even the different climatic regions of northern and southern China.8 In his book he informs that:

If anyone … plants trees or brings different kinds of trees and seeds to a province where they had not been found before, plants and sows them and teaches people how to do so and encourages them to cultivate such trees and seeds, many people will benefit from his efforts and guidance for years to come and reward will accrue to him in the next world.9

Rashīd al-Dīn comments on the skill of gardeners in Isfahan who were adept at tending and pruning fruit trees, especially noted was their care of quince trees. A later Persian agriculturalist was Qasim B. Yusef Abu Nasri who wrote his Ishad al-zira-a in 1515 in Herat.10 Although of a slightly later date it imparts relevant information compiled under the Timurid dynasty. Chapters 5–8 cover horticulture and arboriculture, this work includes advice on vegetables, herbs, aromatics, fruit trees, ornamental trees bushes and flowers (chapter 8, which gives details of an ideal garden’s layout and its suggested plantings, will be discussed later).

Of the Persian gardeners we hear of Al-Zardakāsh who worked for Timur at Samarqand, then (c.1490) Maulānā Hājji Qāsim is mentioned in connection with cultivating different varieties of grapes, also at Samarqand.11 However the most highly respected gardeners of this period were the family of at least three generations working for Sultan Husain in Herat. The elder was known as Sayyid Ghiyās al-Dīn Muhammad Bāghbān (d. c.1499). His son Sayyid Nizām al-Dīn Amīr Sultān-Mahmūd, usually referred to as Mirak-I-Sayyid Ghiyas (c.1476–c.1559) became famous as a great landscape architect, gardener and agriculturalist. His speciality was in the construction and overseeing of the chahār bāgh form of garden and pavilions.12 Mirak’s son Muhammad continued the family tradition of being a master gardener and later worked for Babur and the Mughal court in India, his greatest work was building Humāyūn’s tomb (in 1562) where the garden was an integral part of the funerary complex.13

Occasionally a gardener is portrayed in Persian manuscripts, he is often shown in the background working in the garden area. He is usually depicted with his foot on a spade, several of these spades appear to have a bar just above the cutting blade of the spade. The spades all have long shafts with no cross handle, and apparently the shaft was made from wood of the white poplar tree.

FIGURE 131. Detail of a Persian gardener using a long handled spade with foot rest. Shahnama, c.AD 1420.

Islamic gardens in Spain discovered by archaeology

Evidence of further early Islamic gardens now shifts to Spain because, in the 13th century, the lands of the Middle East were devastated by Mongol Invasions. Sites became ruined and later built over obscuring evidence for the earlier gardens, this catastrophe caused a great gap in time when searching for evidence of Islamic gardens.

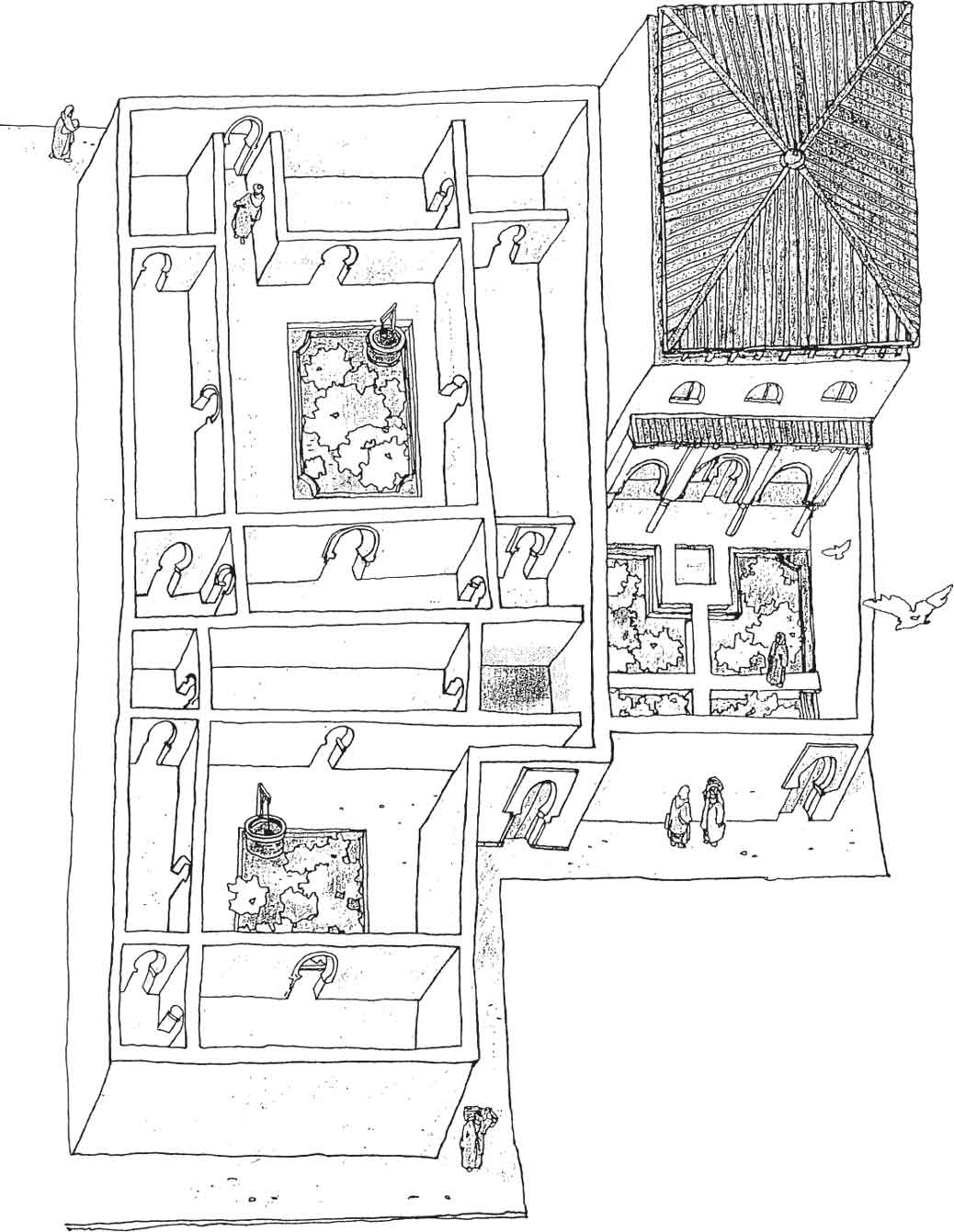

In Spain, however, after the initial Islamic conquests, conditions were more settled, and by chance there are some interesting surviving gardens from the 10th–14th centuries. There is also some evidence of continuity in Spain for the Moors took over a region that had been occupied by the Romans and Visigoths. Some cities such as Cordoba (the former Roman capital of Baetica province in southern Spain) had many gardens that had been commented on by Roman writers. Eleventh century sources indicate that the Muslims had appropriated the Visigothic/former Roman Palace, which now became their Alcazar,14 new buildings were added later. In cities like Valencia archaeologists have recently discovered a house of the Islamic period that directly overlies a Roman dwelling.15 They discovered that the Islamic house preserved much of the earlier Roman one. Each had internal light-well garden courts, and a larger garden because the Roman garden peristyle had been replaced by only one portico. This short colonnade had three Islamic arches. Archaeologists discovered that two distinct levels of garden survived at Valencia, and the Islamic one is believed to have had a design with cross paths to reflect the chahar bagh. In Islamic Spain, though, one Moorish/Spanish name for a garden was huerta, which basically derived from the Latin hortus.

FIGURE 132. Plan of an Islamic house with courtyard gardens at Valencia (after S. C. Gimeno and E. D. Cusi in Garcia, I. L. et al. 1994, fig. 161).

FIGURE 133. Umayyad palace at Madinat al-Zahra, near Cordoba. The large gardens have traces of cross paths, pools and pavilions which would have made refreshing places to relax surrounded by lush vegetation, AD 936–1010.

Cordoba became the capital of Islamic Spain under the Umayyad dynasty that had fled the dynastic infighting within Syria. In 936 the first Caliph of Al-Andalus, Al-Rahman III, built the Moorish palace of Madinat al-Zahra (also known as Medina Azahara) just outside Cordoba. However, the palace was sacked by Berber rebels in 1010 after only 74 years of use. So this site, like Samarra, was destroyed and never rebuilt, thereby preserving details of a richly decorated building and its well furnished extensive gardens. When excavated archaeologists found that the palace was provided with pleasant internal courtyard gardens, and two large terraced gardens with pools and pavilions. The pair of large gardens measured approx. 163 ×144 m.16 These two gardens (called the upper and lower gardens) had both been constructed using the four part design. Each dividing path was bordered by narrow irrigation channels. In the upper garden a pavilion was constructed on a raised platform, this was sited off centre in the garden and had paths and four rectangular pools surrounding it, making this location a veritable garden room, a cool space to relax amidst lush vegetation. How this garden was originally planted is not known, but we can infer from poetry and later manuscripts that it would have been well stocked with seasonal flowers, roses, trellised vines, shrubs, fruit trees and cypress trees. The renowned poet and gardener Ibn Luyün actually said that an ideal garden should have a pool and evergreens.17 These would provide a framework throughout the year that could be enlivened with flowering plants in their season.

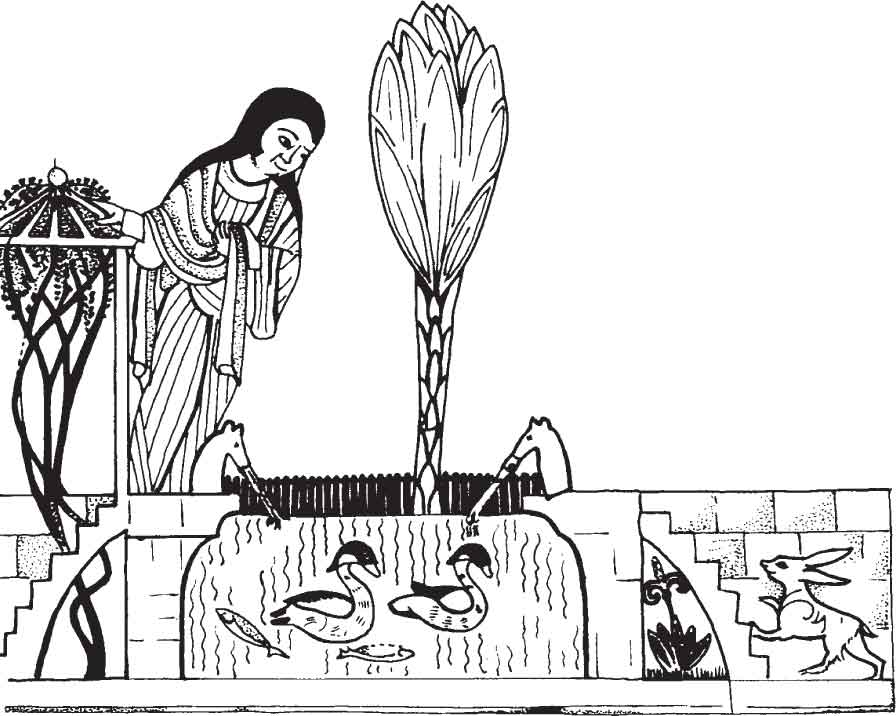

FIGURE 134. A woman looks out over her garden, represented by a pool with horse head fountains, a tall cypress tree and vine arbour, manuscript painting from the Bayad was Riyad Cordoba, now in the Vatican.

Garden pools were often fitted with a fountain to circulate and aerate the water; archaeologists have found a number of zoomorphic garden fountain outlets in Spain. A bronze deer was actually discovered at Madinat al-Zahra, and we can speculate if this was one of the animal figures spouting water on each side of a faceted basin mentioned in a text by Al-Maqqart; sadly he didn’t actually say which species of animals were present.18 A rather sweet stone elephant was found near Cordoba, its trunk functioned as the fountain spout, the elephant hunches his back and lowers his head and trunk, so he appears to reach down and drink the water from a pool. However, the most popular form was that of a lion – either seated or standing. A roaring lion was recorded at Madinat al-Zahra, whereas the lion fountain at the Munyat al-Naūra gardens in Cordoba was said to have had jewelled eyes.19

Contemporary illustrations of gardens from Al-Andalus (Andalucia)

Simple illustrations of Hispanic Islamic gardens survive in the Bayad was Riyad (now in the Vatican) an illuminated manuscript retelling a love story set in the East but was written in Cordoba. The lively scenes portrayed could reflect the gardens of Cordoba and give some indication of life in these gardens. In one scene we see a musician and court ladies singing in a garden. Another shows a duck pond with a slender tree (perhaps a cypress) standing in the middle of a lawned area behind the pool.20 On one side a vine climbs up a trellised arbour, and on the other two women look out over their garden. In the bottom right hand corner an iris plant grows in a niche; and a hare, or perhaps what is more appropriate – a rabbit, is shown about to climb up some stairs. The rabbit was endemic to Spain and was particularly noted by the Romans who used it as one of their symbols for their province of Hispania, the new Muslim overlords were continuing this idea. The pool in this garden was ornamented with paired fountains in the form of a horse’s head, the water spouting from their mouths.

A poem commemorating a garden in Spain

We can picture in our minds another garden, called Al-Amiriya, that lay alongside the river in Cordoba. This garden was mentioned in an evocative poem composed by Sa’id (c.978) a poet sent from Baghdad to commemorate al-Mansur’s new gardens that had been given as a wedding gift by his father:

Behold the river nearby, gliding like a snake,

While the birds sing praises, in the shelter of the trees’ limbs.

And the branches drunkenly embrace in the swaying of their boughs.

And the gardens reveal the splendour of the daisy’s smile.

And the tender narcissus gazes at the anemone’s cheek,

While the gentle wind bears the scent of sweet basil.

May you pass an eternal lifetime here in happiness and peace!21

Surviving Islamic gardens of Al-Andalus

Fortunately there are comparable Islamic palaces in Spain that are less ruinous, although these have later additions. Three gardens within the Alcazar of Seville, the palace of the Almohad caliphs retain elements of their original 12th century design. The garden now called the Patio del Crucero (which was a large courtyard of 47.40 × 34.40 m)22 and that of the Casa de Contratación both featured the familiar cross-axial plan. This basic design was however modified to create two levels, the raised pathways created four sunken garden areas. This development would help to retain moisture for bushes and/or trees planted there. Any deluge of rain would immediately wash away and keep the paths dry. In the Patio del Crucero garden, a circular fountain basin had been placed at the centre of the cross-axial paths, water would pour over its sides into its surrounding circular water basin from which water flowed through intercommunicating water channels along the four paths radiating outwards, making the whole garden visually appealing. Small trees, such as the oranges that are flourishing there at present, would have their canopy at a lower level and at a glance would resemble bushes. You would be able to pick the fruits more easily at this level and the beautifully scented flowers of these trees would more easily be appreciated when strolling in the garden. The third courtyard garden was the Patio del Yeso, which consisted of a rectangular pool presently flanked by narrow beds planted with orange trees under planted with sweet violets.

A palace had been constructed in Granada in the 11th century by the vizier, but with the rise of the Nasrid dynasty a great building program was began at the Alhambra palace by sultan Muhammad I (1232–1272). His descendents added numerous features, but the lions in the Fountain Court are survivors from the earlier days of these gardens.23 The garden in the Court of the Lions was divided into four quadrants by paths which had a rill, a narrow shallow water channel, running down the centre of each path. The water of the fountain poured from the mouths of twelve lions facing outwards, down into a shallow circular basin beneath them, then along each of the four rills. The 12 lions spouting water in the Court of the Lions were arranged to appear as if they were shouldering the weight of a huge water bowl. The text inscribed on the rim of this fountain bowl is engaging: ‘Truly, what else is this fountain but a beneficent cloud pouring out its abundant supplies over the lions underneath?’ Water was always an important feature in Islamic gardens, as they were in Byzantine gardens. The sound of water playing in a fountain is very soothing and peaceful, it also helps to muffle conversations you did not want other people to overhear, so in certain places a fountain could also create a semblance of privacy.

It seems that at the end of the 13th century (in the Nasrid period) the layout of Islamic gardens in Spain changes; the familiar quadripartite design seems to be replaced by gardens with large or elongated pools.24 A good example of this new form is seen in the Court of the Myrtles at the Alhambra constructed by Yusuf I (1333–1354). Myrtle bushes have been planted in a strip on either side of the central large rectangular pool, and as far as we know this has always been the case because myrtles (and oranges) were noted in this garden just after the Christian conquest of Granada in 1492.25 The pool of this beautiful garden provided a sheet of still water which has the effect of a mirror by reflecting the architecture around it on its surface; this is an excellent example of what is termed a reflection pool. It gives a wonderfully calm atmosphere to the area. Two circular fountains were placed at either end of the long length of the glistening pool, they serve to break the otherwise severe straight lines of this garden’s design and they add life to the otherwise placid environment.

In the early 14th century Muhammad III built a sumptuous summer palace, the Generalife, to catch the breezes higher up on the hill above the Alhambra at Granada. The most celebrated garden here was the Acequia Court (or Canal Court) which because of its terraced location was designed as a long narrow garden. It has an elongated narrow water channel along the centre of the garden that is divided into two parts by a cross path. Circular water basins have been placed at the beginning, middle and end of its course. The break in the middle of the two pools allows for a four part garden design although here four elongated octagonal plant beds were created. Excavations in this area found details of the original garden design 70 cm below the present pavements. Deep plant pits were discovered suitable for planting shrubs and small trees. We can envisage the scene because contemporary sources noted myrtles and orange trees growing there.26 Sadly the series of water jets that line the two halves of the long water feature in this garden were not part of the original design, and are later additions.

The Islamic architects often incorporated prospect balconies called a manẓar, in Spanish a mirador (meaning a place for looking), so you could gaze down and enjoy the view over a garden below. The walls of the mirador overlooking the Lindaraja Gardens of the Alhambra were covered with poetic inscriptions in stucco. In one of these, the poet Ibn Zamrak says: ‘In this garden I am an eye filled with delight and the pupil of this eye is, truly, our lord.’ He therefore informs us that the mirador could be likened to an eye allowing a view of the garden.27

Mosque gardens

Gardens were sometimes constructed in the forecourt of mosques, like earlier atrium gardens, but these were predominantly filled with trees not flowers. The earliest is attached to Cordoba’s Great Mosque (the Mezquita). The altered courtyard garden (measuring c.120 × 60 m) was laid out under al-Mansur in 987–988. The former great mosque of Seville was similarly provided with a tree planted forecourt. These gardens were basically a bustan, a grove of trees to shade believers as they congregated for prayers. Today they are both planted with orange trees and are known as the Patio de los Naranjos, the trees are neatly aligned in rows. Originally the ground was of beaten earth but it is now paved, except for a reserved section for each tree.28 A regular network of stone-lined narrow irrigation channels supply water to each individual tree. These gardens also contain a water basin where worshippers could perform their ablutions.

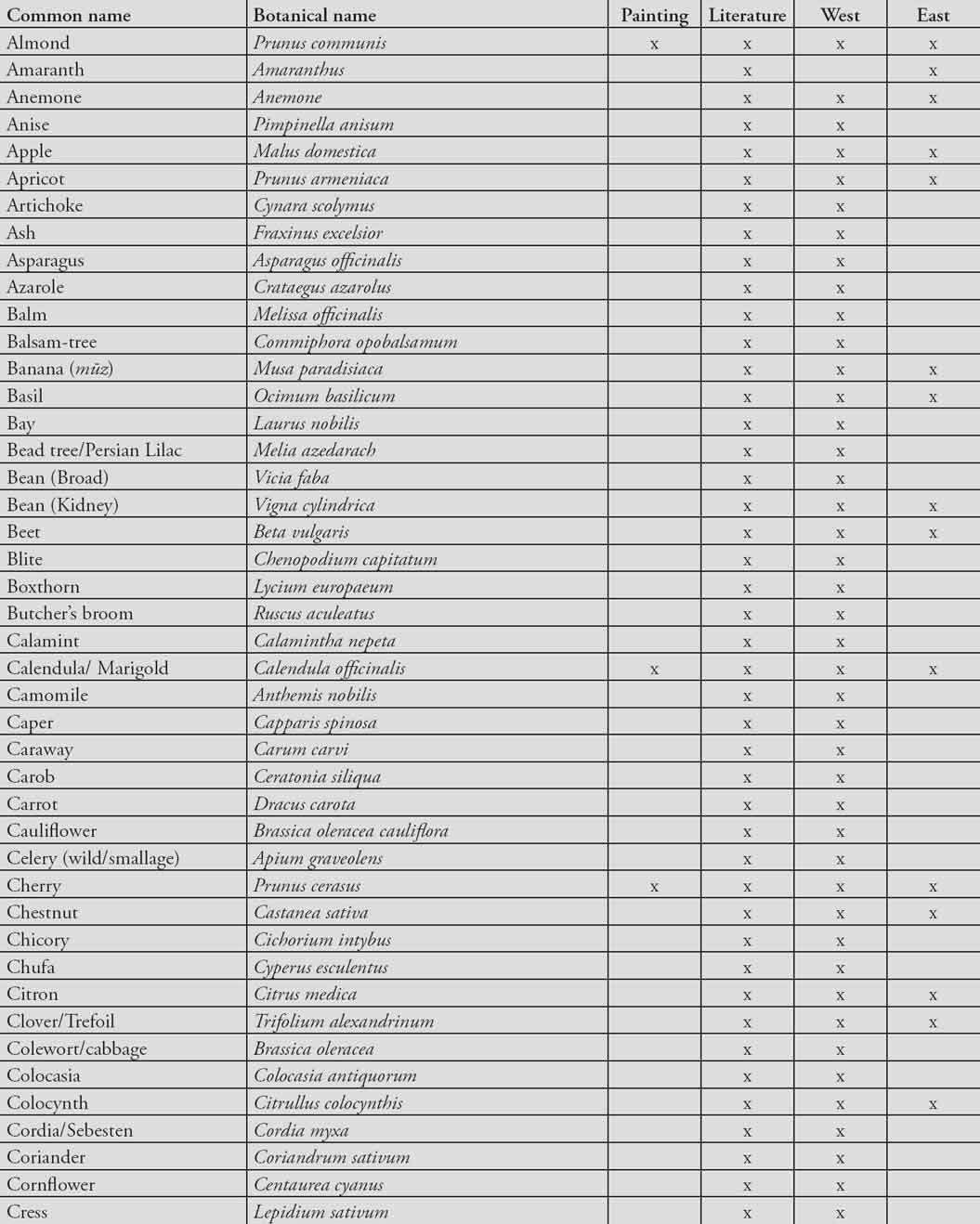

Plants grown in Islamic Spain

Several Islamic manuscripts from Spain mention garden plants, and together with surviving treatises on agriculture/horticulture they can give an indication of what was grown in the gardens there. The earliest is Le Calendrier de Cordoue by Arīb b. Sa’īd, which dates from 961–976. This lists about 100 plants, mostly fruit trees and crops that were growing in Cordoba; it also gives the dates for sowing, planting and harvesting. Later works such as The Book of Agriculture by Ibn al-Awwām writing in Seville c.1085 and Ibn Luyün from Granada in 1348 (mentioned earlier) give a larger number of plants, and the rising number of garden-worthy plants reaches 160.29 Some of the plants and trees are species that would be classed as tender in more northerly climes, and are therefore less familiar to us. Also several cannot be fully identified in translations from the Arabic originals into Spanish. A large proportion of the plants were already known from Roman times, but there were notable introductions to the country such as the banana (Musa paradisiacal) then known as mūz, and the Seville orange (Citrus aurantium) in Arabic it was called nāranj. The latter was first recorded in Spain by Ibn Bassāl c.1080. The grapefruit (zanbū) is mentioned at a later date. We also hear for the first time about the Judas tree which was much admired for its coloured flowers, and the bead tree (Melia azederach) with its panicles of attractive lilac flowers followed by yellow berries.

In the work by Ibn Luyūn he specified that ‘numerous plants are cultivated for the delight of sight and smell, or to be used as ornamentation.’30 These plants, he says, were planted in the bustan; in this case he uses the Arabic term used for an enclosed orchard or grove, but these were clearly also treated as a domestic garden. He shows that at least one part of the bustan would have been reserved for leisure purposes. What is clear is that colourful flowers were sought for and that aromatic plants were highly favoured. In many cases the texts mention digging up wild plants to transplant into the garden/orchard. Some of the comments made by Ibn Luyūn and others are informative on plant usage in the garden. The lily they say ‘is planted in those areas of the orchards where no labour is made, and next to the ponds. It is planted in gardens and houses because of its beauty.’31 The colocasia was used for its beautiful foliage effect, it was apparently ‘planted next to water flows’; this plant seems to have taken over the role played by the acanthus mollis (favoured by the Romans) which is not mentioned at all. Other flowers planted in gardens/orchards are water lilies (especially the white ones), yellow narcissus, violets, wallflowers, stocks, vinca, camomile (or similar daisy-like species), anemones, mallow, rose, red flowered hibiscus, butcher’s broom, oleander, strawberry tree, lavender, rosemary, basil and aromatic herb species simply identified as ‘incenses’. Of the trees mentioned the spiny azarole was used in making hedges around vineyards and gardens. Several trees were useful giving much needed shade, such as the elegant nettle tree (Celtis australis) which was planted by garden walls. The stonepine and the cypress were noted as suitable for planting around the bustan walls ‘in order to beautify them’. The texts also say that if the stonepine ‘is planted in the middle of a pool or pond, it causes delight with its beauty and shade.’32 This must mean that it was planted on an island. The cypress was also used for lining pathways in gardens. Myrtle was used ‘surrounding the pavilions in gardens’. Oleaster and service trees were referred to as beautiful trees and together with pomegranates were planted near wells and pools. The citron, lemon, orange and grapefruit were planted where they would be sheltered by garden walls, especially from cold north winds. Ivy was apparently allowed to grow on reed lattices to create shade for other plants, and could provide an architectural element within gardens.

FIGURE 135. Walkways surround an elongated pool flanked by sunken garden beds. Patio del Yeso, Seville Alcázar, 12th–13th century.

FIGURE 136. Reflecting pool, Court of the Myrtles, Alhambra, Granada, 13th century (photo: © 2010 G. Farrar).

Ibn Luyūn also provides a useful summary in verse explaining how large decorative gardens should be laid out and makes suggestions as to how it should be planted:

Then next to the reservoir plant shrubs whose leaves do not fall and which rejoice the sight; and, somewhat further off, arrange flowers of different kinds, and further off still, evergreen trees. And around the perimeter climbing vines, and in the centre of the whole enclosure a sufficiency of vines; and under climbing vines let there be paths which surround the garden to serve as a margin. And amongst the fruit trees include the grapevine… [also] arrange the virgin soil for planting whatever you wish should prosper. In the background let there be trees like the fig or any other which does no harm; and any fruit tree which grows big, plant it in a confining basin so that its mature growth may serve as a protection against the north wind without preventing the sun from reaching [the plants]. In the centre of the garden let there be a pavilion in which to sit, and with vistas on all sides, but of such a form that no one approaching could overhear the conversation within and whereunto none could approach undetected. Clinging to it let there be [rambler] roses and myrtle, likewise all manner of plants with which a garden is adorned.33

Surviving Islamic gardens in Morocco and Sicily

In Morocco large gardens were constructed in association with the sultan’s palaces. In Marrakech there are two gardens of note: the Agdal and the Menara (both date to c.1157). The former gave its name to a special type of garden seen in this country. The Berber name agdal, like its namesake, was applied to large walled gardens predominantly stocked with trees planted in regimented rows. These gardens contained one or more rectangular huge water basins that were used as reservoirs to irrigate the gardens. To make this easier there was an extensive network of water channels and several enclosures within these vast gardens. The Islamic agriculturalists of the west were well known for their ground breaking knowledge and application of hydraulics. Sources suggest that the Agdal and Menara gardens were stocked with numerous trees, among which the following were named: apricots, grape vines, olive trees, oranges, and aromatic plants.34 Today many varieties of fruit trees are planted there, and the pathways between enclosures are even shaded by trellises of jasmine and roses. These historic gardens are thought to have been created by Al-Hāj Yaʿīsh, an outstanding landscape architect working for the Almohad rulers.

In Norman Sicily there was a palace and gardens in Palermo that were greatly influenced by Islamic stylistic ideals (built c.1155 by Arab-Normans), it is now called La Zisa, which derives from the Arabic aziz meaning precious). An inscription in Kufic script above an archway says: ‘This is the earthly paradise which opens to the regard; this is the Must’azis and this is the Aziz.’ The gardens were greatly admired by later visitors to Palermo (inc. Alberti), they mentioned a pavilion beside a pool, fountains and groves of oranges and lemons. A French count, Robert II of Artois was so impressed by what he had seen (in 1270) that on his return he tried to recreate the water features in his own garden.35

Garden poetry and literature in the Eastern Islamic/Persian world

In the 10th century Baghdad was considered the wealthiest city in the eastern Islamic world, it was the setting of the fabulous Tale of Arabian Nights. Visitors to the city describe palm filled gardens with pools and pavilions, perhaps like those of Spain mentioned above. Early writers in Spain often compared their homes and gardens to those in their eastern homeland.

The name of this city is descriptive for bagh means gardens; it was once literally a city of gardens. Several Persian poets praised gardens and the beauty of nature, the first was Firdausi, the great epic poet of Iran who wrote his Shahnama (History of Kings) c.1010. In this verse he recalls the garden of the daughter of Afrasiyab.

It is a spot beyond imagination

Delightful to the heart, where roses bloom,

And sparkling fountains murmur – where the earth

Is rich with many-coloured flowers; and musk

Floats on the gentle breezes

And lilies add their perfume – golden fruits

Weigh down the branches of the lofty trees.36

In the 12th–13th centuries the greatest poets were Hafiz and Sa’di from Shiraz. They are often quoted today because of the timeless quality of their work. Hafiz often included a line or two on flowers, as well as incorporating the joys of life, women, and merry making. Here is an example:

Let’s go to the garden and have some fun,

Let’s sing like the birds and sit in the sun

let’s look at the colours, red, blue, and pink

by the beds of flowers let’s sit and drink.37

Another verse from Hafiz is understandably a favourite one; it has a resonance to today for who wouldn’t like to do the same:

Oh! Bring thy couch where countless roses

The garden’s gay retreat discloses;

There in the shade of the waving boughs recline

Breathing rich odours, quaffing ruby wine!38

Sa’di wrote two books of poems, the Bustan and the Gulistan the Rose Garden. In these he writes moralistic stories and poems that are compared to a collection of flowers in a garden, hence the title. Here is a telling verse:

What use to thee that flower-vase of thine?

Thou would’st have rose-leaves; take then, rather, mine.

Those roses but five days or six will bloom;

This garden ne’er will yield to winter’s gloom.39

The roses in Sa’di’s Gulistan garden would, metaphorically, continue to bloom because they were written words and the written word lives long. Sa’di loved his garden so much that he chose to be buried in his own at Shiraz. His next poem shows that Islamic gardens could be colourful with many hued flowers:

A garden where the murmuring rill was heard;

While from the trees sang each melodious bird;

That, with the many-coloured tulip bright,

These, with their various fruits the eye delight.

The whispering breeze beneath the branches’ shade,

Of bending flowers a motley carpet made.40

Omar Khayam (c.1048–1125) is famous for his Rubáiyát which is full of emotion and has a haunting quality. In verse five he reminds people of the fabled gardens of Iram (mentioned earlier):

Iram indeed is gone with all its rose

And Jamshyd’s Seven-ringed Cup where no one knows;

But still the Vine her ancient Ruby yields,

And still a Garden by the Water blows.41

The rose is often mentioned and in verse eighteen it is used to dramatic effect:

I sometimes think that never blows so red

The Rose as where some buried Caesar bled

That every Hyacinth the Garden wears

Dropt in its lap from some once lovely Head.42

Omar Khayam’s tomb is at Nishapur in Iran in a region where a distinctive rose blooms. As a mark of respect to his translator a specimen of one of these roses was collected and planted on the tomb of Fitzgerald in 1893. This rose is now cultivated under the name Rosa ‘Omar Khayam’. It is a light pink rose with a semi-double quartered head, and greyish foliage.

Persian poetry shows there was a special attachment to the rose, above any other flower, its scent is often mentioned with nostalgia. Roses grow well there, and their damask rose (Rosa damascena), also known as the Muhammadan rose, was also used for making rose water and attar rose oil. Apparently the mythical king Jamshid was attributed with discovering the use of aromatic plants and the distillation of their prized rose oil. The particular form of rose used is so quintessentially associated with Iran that it was generally referred to as the ‘Persian rose’. As mentioned earlier the rose was called gul, but this word was also used for flowers in general. Often a flowering plant would have a gul prefix e.g. gul-i-narges which can be translated as ‘narcissus flower’. There were names for different species of rose. They had a hundred-petalled rose which was known as gul-i-sad barg, and a musk rose that was called mushkīn.43 Beside pink and red roses there was also a yellow Persian rose, known as gul-i-zard. There was even a name for people who so admired roses, or flowers, they would call themselves a gulbaz.44

Nizami wrote his Khamseh (a book of five poems) c.1209, this extract provides more information on gardens during his period, and an indication of some of the flowers and plants that these eastern gardens could contain. The poet rejoices that the garden is reawakening in Spring:

Come, gardener! Make gladsome preparation,

The rose is come back, throw wide open the gate of the garden.

Nizami hath left the walls of the city for his pleasure ground;

Array the garden like the figured damask of China.

Dress up its beauty with the ringlets of the violet;

Awaken from its sleep the tipsy narcissus.

Let the lip of the rosebud inhale a milky odour;

Let the tall cypress spread wide its branches,

Tell the news to the turtle dove, that its bough is again green…

The lip of the pomegranate stain with red wine;

Gild the ground with the safflower.

Give to the lily a salutation from the Judas tree;

Direct the running streamlet towards the rose-bush.

Behold again the newly-risen plants of the meadow!

Draw no line over that delicate drawing!

Others like me are inspired with the love of the verdant;

Bear my salutation to every green thing.

How the mild air of the garden is attractive to the soul!…

The trees are blossoming by the edge of the garden.45

Islamic scholars studied Graeco-Roman texts and were particularly interested in medicine and the use of herbs grown in gardens. Many surviving manuscripts have Arabic notations alongside the Greek or Latin, and of course copies in Arabic were made. It is perhaps rather surprising that one of the earliest surviving copies of the Herbal of Dioscorides is in fact an Arabic one. In some versions, illustrations of Dioscorides now show him wearing Islamic dress rather than his Roman toga! Roman manuscripts written by Galen were also studied, and his Book of Antidotes was popular. One of the remedies was for snakebite and as with others an illustration accompanied the text. In this case a man is depicted with the offending snake, but a doctor arrives on horseback to provide a timely antidote, this involved drinking a concoction of crushed leaves and flowers of oleander. Therefore an oleander plant was shown in flower nearby, other trees are in the background. Oleander is poisonous so the dose needed to be mixed carefully, apparently it was more affective if some rue was added. Oleander was often included into gardens despite its toxicity, it is nevertheless a decorative plant and as we have seen it has its uses.

Funerary gardens

The great poets Sa’di and Hafiz were both honoured by the construction of a memorial at the site of their tomb in Shiraz. The city of Shiraz has long been known as a garden city because of its regular water supply. In the 15th century the area around each tomb was beautified by the creation of gardens. The Sa‘diyya (or Arāmgāh-e Sa’dī), the funerary garden of the celebrated poet Sa‘di is located in a narrow valley with a spring flowing through, it is shaded with cypress and pine trees. Sa‘di’s tomb is about a mile north-east of the Hafiziyya which commemorates the much loved Hafiz; both were buried in their native city. Hafiz’s tomb garden has two pools and the pleasant park-like surroundings are shaded by trees, and adorned with numerous plant pots filled with flowers. These gardens have been enhanced in recent years and there are now pavilions where people can read the verses of these great poets.

Descriptions of gardens in the Eastern Islamic World

As a consequence of the invasions of nomadic Mongols in the 13th century, cites throughout Persia and the Middle East were pillaged and plundered, there was widespread destruction in town and country. Irrigation canals were severed and this led to large areas reverting to desert. When the land became more settled the new Mongol overlords made use of the remaining chahar bagh gardens but in a different way. Early Islamic gardens were mainly designed to be looked at, but now the grassed areas were seen as ideal places to erect tents or to create a kiosk (an open pavilion) where they could rule and be entertained in fresh air. One of the most fearsome rulers was the mighty Timur (who we know as Tamerlane) who became lord of Samarqand in 1369. A series of military campaigns enabled him to establish a vast territory under his control, from the Mediterranean to the Himalayas and from northern India to Russia. Fortunately three writers documented this period, one of them being a Spanish ambassador called Clavijo who provides valuable descriptions of audiences and festivals held in the ruler’s gardens:

We were come to a great orchard … [various members of the court were seated on a dais under an awning] Then coming to the presence beyond we found Timur and he was seated under what might be called a portal … He was sitting not on the ground, but upon a raised dais before which there was a fountain that threw up a column of water into the air backwards, and in the basin of the fountain there were floating red apples.46

Timur brought in architects from far and wide to construct new garden areas, and was justifiably proud of them. We hear of six different garden zones, one of these was the Dilgusha garden (which means Heart’s Ease) this was the first garden Clavijo entered. Then there was the Bagh-i-Maidan (garden of the square), Bagh-i-Shimal (northern garden), the Bagh-i-Naw (new garden), a Gul Bagh (a rose garden), and a Chenar Bagh (a garden with plane trees); the oriental plane provides ample shade and would make ideal places for al fresco dining under its wide canopy. These elements are seen in some of the Persian miniature paintings. Clavijo gives another description of one of these Timurid gardens at Samarqand:

We found it to be enclosed by a high wall which in its circuit may measure a full league around, and within it is full of fruit trees of all kinds save only limes and citron-trees which we noted to be lacking. Further, there are here six great tanks, for throughout the orchard is conducted a great system of water, passing from end to end: while leading from one tank to the next they have planted 5 avenues of trees, very lofty and shady, which appear as streets, for they are paved to be like platforms. These quarter the orchard in every direction, and off the five main avenues other smaller roads are led to variegate the plan.47

The paved ‘platforms’ mentioned here could well be raised walkways. The lack of citrus trees in this unnamed garden could be due to cooler winters in the region of Samarqand.

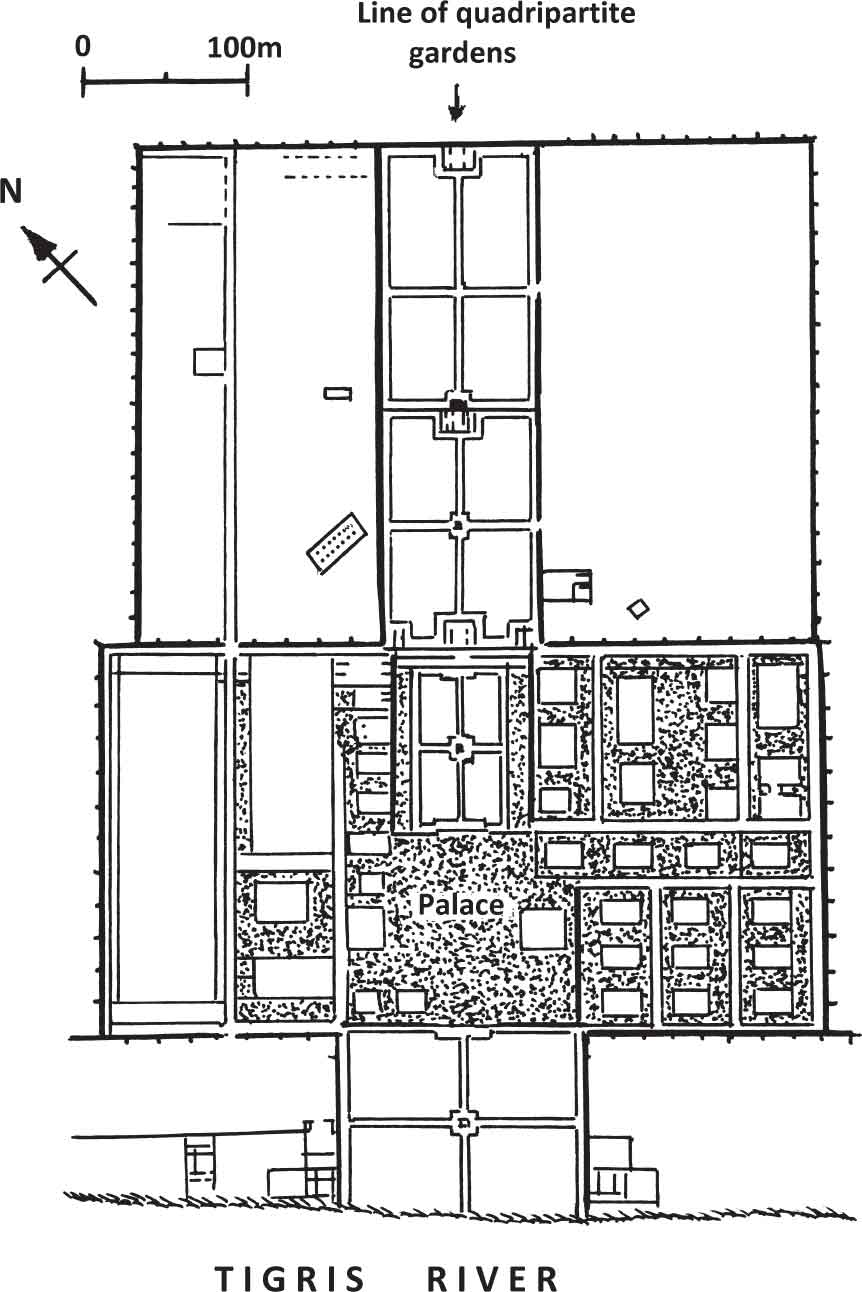

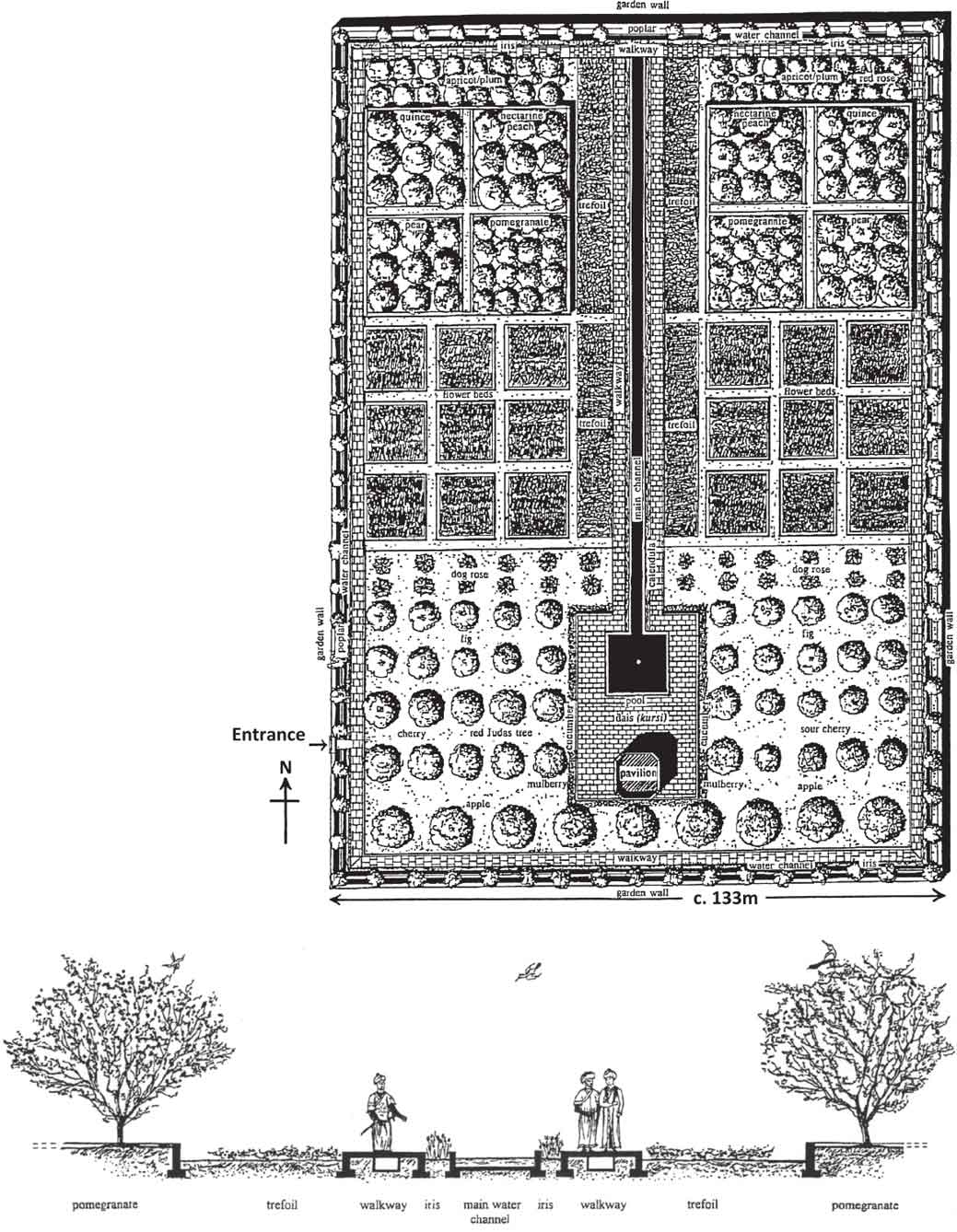

Fortunately a detailed description of the layout of a Timurid garden is preserved in the Ishād al-zirā-a an agricultural manual written by Qasim B. Yusef Abu Nasri. In this book the eighth chapter deals with the laying out and planting of a garden.48 This great work was written in 1515 for the new Safavid rulers, but it relates the expertise of the preceding Timurid dynasty. Nasri had consulted Mirak-I Sayyid Ghiyas of Herat (born c.1476), who was the most knowledgeable horticulturalist at that time and was one of three generations of notable gardeners.

When the measurements given are translated we find that this Timurid garden was c.133 m wide, and the whole rectangular walled garden would be about 2.4 ha. Nasri suggests that there should be a raised walkway on either side of a water channel running through the length of the garden leading to a raised platform, a dais, with a pavilion and a pool. These elements effectively cut the garden into two halves. Poplar trees were planted around the perimeter garden wall with irises below, next to a path that follows the circuit of the walls. The interior of the garden is divided into three areas reserved for rows or squares of one or two species; these were aligned symmetrically in the garden on both sides of the central path. The first part comprised fruit trees; you would encounter rows of apricots and plums, but there was a space for red roses in the upper corner. Next came eight paired squares, two for quince, two for nectarine and peach, two for pomegranate and two for pear. The middle section comprised 18 square flower beds and four elongated plant beds with trefoil (clover) and a narrow strip of calendula that were sited alongside the central path. The remaining third that was closer to the dais was planted in rows, there were dog roses, figs, cherry, flowering Judas tree, sour cherry, mulberry, apple and surrounding the dais they planted cucumber.

The 18 paired flower beds contained the following plus some unidentified flowers:

1. blue violet, iris, ‘hundred-petaled’ rose and wild saffron.

2. Saffron crocus, narcissus and ‘six-petaled’ rose.

3. Tulip, iris, and common anemone.

4. ‘Blue’ jasmine, ‘yellow’ Judas tree, yellow violet, ‘two-tiered’ tulip and stocks.

5. Red rose, yellow rose, jonquil.

6. Rose interspersed with red poppy.

7. Yellow jasmine, ‘six-month’ rose, waterlily, pinks, lemon-yellow iris and hollyhock.

8. Hollyhock, white jasmine.

9. Oriental tulip and amaranths. And by the pool there were dog roses or eglantine.

Nasri makes this comment: ‘Be sure to take good care of your trees and flowers, In short, don’t be idle for a moment!’49

Depictions of Islamic Persian gardens

A collection of manuscripts was assembled by Timur’s son Shah Rukh and others in Herat (the new Persian capital, 1408–1447), and fortunately a few from this period survive. The famous epic by Firdausi, the Shahnama, was copied and the greatest painters of the day were commissioned to make illustrations to accompany this much revered text. A later version was given 258 miniature paintings. Other famous books were treated similarly with several illustrations to match key points in the text, of these Nizami’s Khamsa was also well illustrated. Some scenes show events taking place in a garden and these can be helpful when trying to visualize gardens of the period.

FIGURE 137. Reconstruction (plan and cross-section) of the layout of a Timurid garden of the 15th century, based on descriptions in a Persian agricultural manual written by Qasim B. Yusef Abu Nasri, the Irshad al-zira.

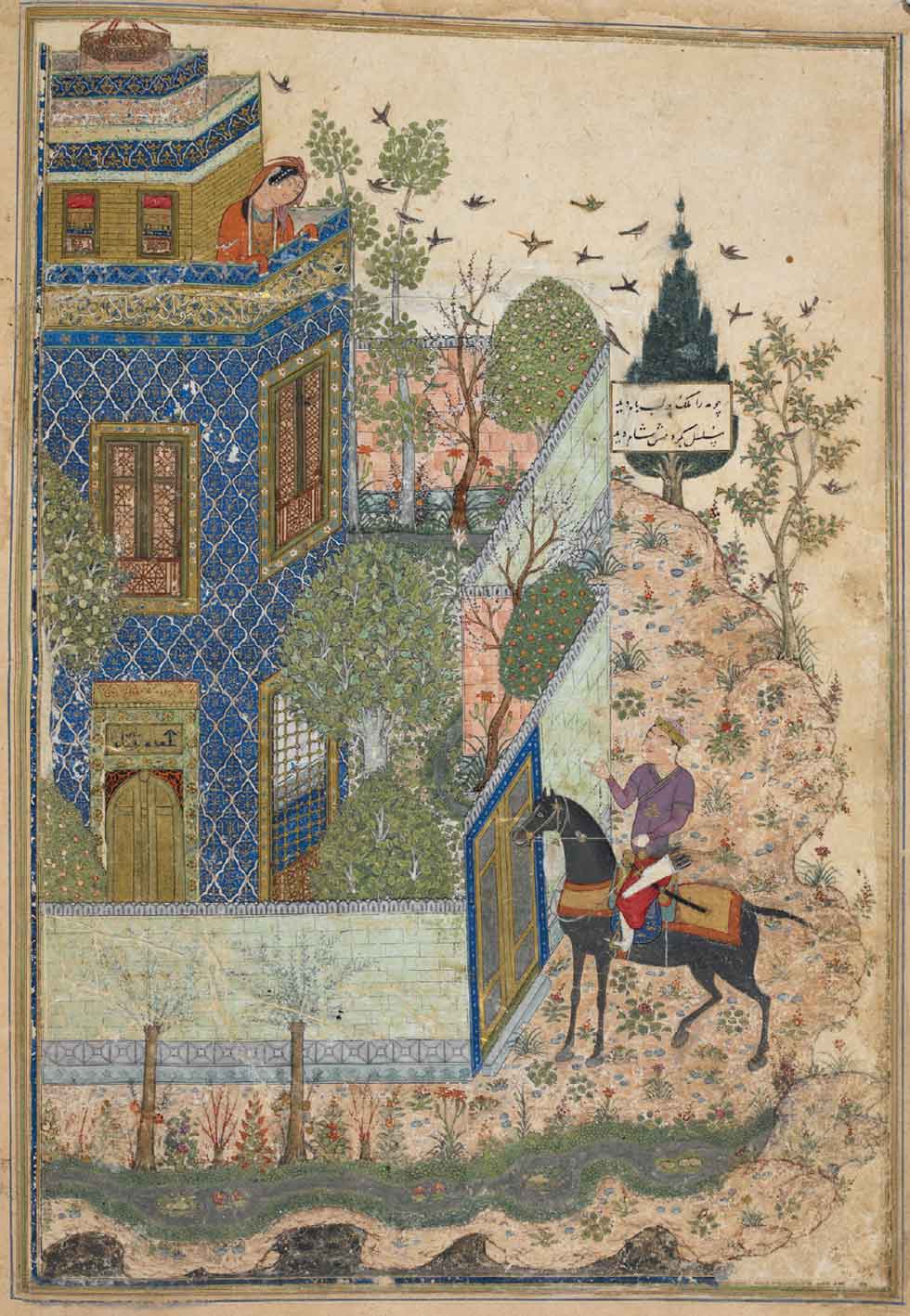

One of the earliest Persian miniatures painted by Jonayd (c.1396) that depicts a garden rather than a landscape is found in the romance story of Humay va Humayun in the Divan of Khvaju Kirmani of Baghdad. This retells the tale of the Persian prince Humay meeting the beautiful Humayun, the daughter of the Mongol Emperor of China. This story highlights the links Persia had with other cultures mainly via the Silk Road (another miniature featured a delegation from the ruler of Hind in northern India). The tale was retold many times over the centuries. In the version illustrated here Humayan watches from an upper floor of the palace as Humay approaches on his horse. The palace and its garden resemble that of a modest Persian house, and we see the typical high walls that protect the property and its garden from the elements and marauders. Tall trees border the garden with flowers at their base. We can make out a white lily, red carnations, mallows/hollyhock and a pale pink rose bush within this delightful garden. Another scene from this romantic story shows the two lovers seated on a dais taking tea in the middle of what appears to be a large garden bordered by flowering trees, that include cherry blossom, hibiscus and roses. Servants pick rose buds from a tall bush. A multitude of low growing flowers covered the ground. Each flower had been painted with care, but we note that there was a predominance of red and pink flowered species depicted here for effect.

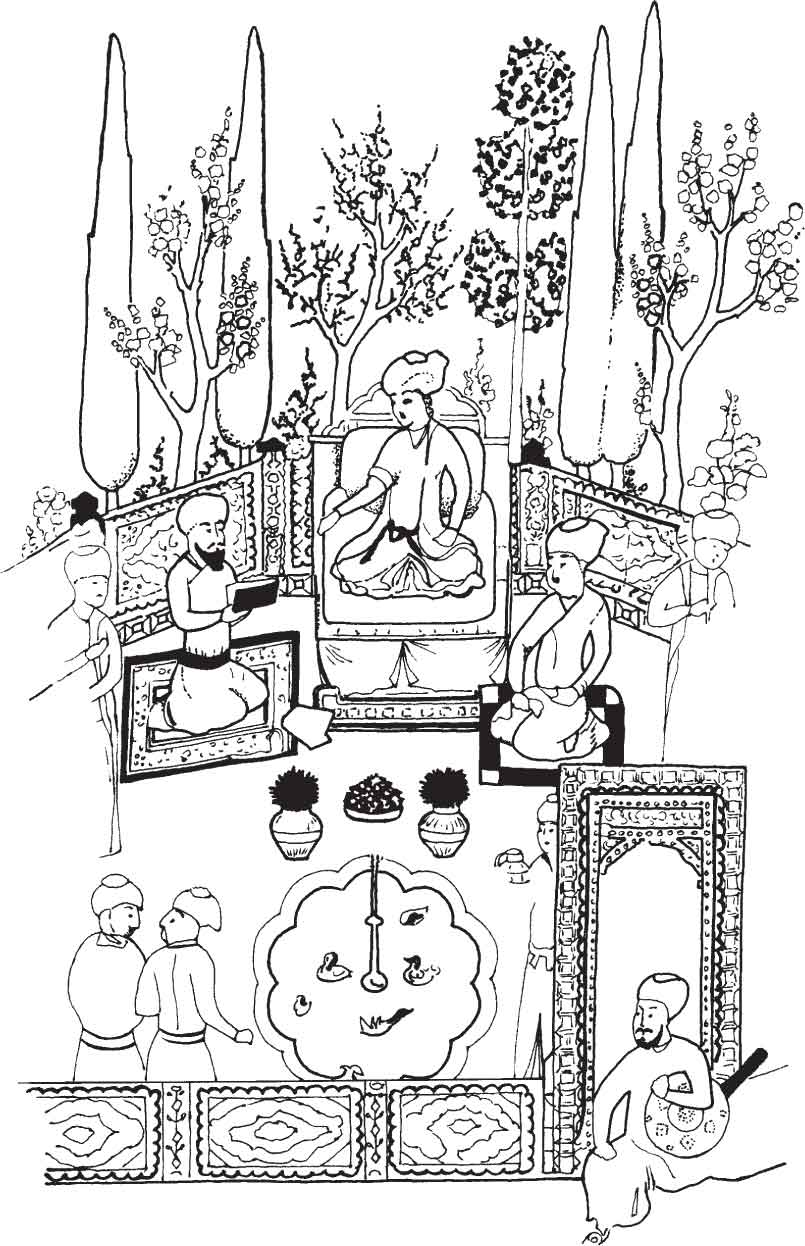

The Teheran copy of the fables of Kalila and Dimna (1420–1425) has a frontispiece illustrating the presentation of the manuscript to its patron seated on a dais in his garden. The dais was set on what appears to have been an octagonal platform surrounded by a decorative low wall. One of the court officials is shown walking through its arched entrance. In front of the throne on the dais there is a fountain set in the centre of an ornamental pool, its outline mimicking that of a ten- petalled flower. Ducks swim in the pool, the water is now grey because the original silver has tarnished.50 In the background there are flowering bushes and flowers; with fruit trees shown in full blossom, one pink and two with white flowers. In between are four tall slender cypresses standing in pairs, the cypress was much admired for its elegant form. There were also two tall white stemmed poplar trees that had been carefully clipped into tiers. The most popular trees depicted in Persian miniatures are: the ubiquitous cypress, cherry blossom trees or blossom trees in general, plane trees, poplar and willow.

Scenes from the Khamseh written by Nizami were painted by numerous artists over the years, but Aga Mirak from Herat was an artist who was working for the Timurid dynasty. One of his miniatures (of c.1494) illustrates the tale of Shirin and Khusraw, another famous Persian love story that relates to a much earlier date. Mirak painted Shirin seated on a carpet, on a plant filled green sward, in what could be a Chenar Bagh. Three tall trees and a willow hint at what could be a shady picnic spot. Music and refreshments were at hand. Shirin who was a beautiful Armenian princess is shown contemplating a portrait of her intended, Khusraw. Khusraw was a much earlier great Sassanian Persian king, who led a fearsome army up to the gates of Istanbul in 608 (the Byzantines called him Chosroes II). To the Persians he was a hero and often featured in their legends.

FIGURE 138. A prince seated in his garden, from the frontispiece of the Fables of Kalila and Dimna, Teheran, c.AD 1420–1425.

Another memory that has survived and was passed through succeeding generations is the special paradise garden depicted on Persian carpets. They preserve the story of a very famous carpet owned by the Sassanian King Khusraw I. The original carpet was said to have graced the floor of the king’s audience hall so everyone of rank would have been familiar with it. This carpet was known as the ‘Winter Carpet’, it had been specially designed to depict the king’s fabulous garden as it would have appeared in Spring. He had regarded this garden as his own paradise, and therefore this carpet would be a reminder to Khusraw and his courtiers of their beautiful verdant garden until Spring returned. The later paradise carpets show what is basically a chahār bāgh (a four part garden) divided by four broad water channels, although some carpets have more garden areas and water channels. Water is usually indicated by wavy lines and fish swim along the watercourse, sometimes ducks swim alongside them. The number and width of these channels emphasis how water is all important in these arid lands. The centre of the composition has a shaped pool or a decorative device to simulate the position of a central dais and pavilion. There is usually a border of specimen plants/trees and the remainder is filled with square or rectangular plant beds. In some versions the flowers and trees are depicted schematically, in others the plants are more defined, the most accomplished also include garden fauna, a variety of birds and even rabbits, foxes and deer. There is a conspicuous profusion and the aim was to show an imagined paradise.

FIGURE 139. A Timurid walled garden, trees border the garden with flowers at their base, Humay va Humayum, by Khvaju Kirmani, Baghdad, c.AD 1396 (© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved. Add 18113 f.18v).

Surviving Eastern Islamic/Persian gardens

Although several named gardens are known, these have not survived the vicissitudes of time. In 1941 archaeologists working in Samarqand discovered a garden built for Ulugh Beg, Timur’s grandson. They unearthed a number of ceramic pipes and evidence for irrigation channels within and around the garden, and brick and marble paving.51 Sadly at that time no record was made of any botanical evidence.

Near Herat, a city once famed for its gardens, only two Timurid period gardens survive. One of these is the funerary garden of Gazar Gar, an 11th-century saint favoured by Shah Rukh who ordered the garden to be made in 1428.52 The second garden is now ruinous, but was noted in Soviet aerial photography in 1946. The garden was defined by a walled rectangular enclosure and a familiar quadripartite designed garden plan. It may have been part of the Bāgh-i Jahān-ārā of Sultan Husain that was recorded as being approximately 132 acres (c.53.4 ha).53 In 1933 Robert Byron wrote that the ruined garden he saw here was on terraces, there had once been a pavilion and water features, and ‘from the empty tank at the top, a line of pools and watercourses descends from terrace to terrace.’54 This region has been a war-zone for a number of years and therefore no garden archaeology was possible.

The majority of surviving Islamic gardens in the East belong to the next dynasty, the Safavid, who rose to power in 1502 and are therefore out of the scope of this book, as are many of the beautiful Persian miniature paintings of this era. The earliest of the Safavid gardens, the Bagh-i Fin, dates to 1590, but the walls of the enclosure are earlier as they are mentioned in sources in 1504,55 so there may have been a pre-existing garden there. The Bagh-i Fin is believed to preserve the spirit of Timurid gardens. It is predominantly a plantation of cypress trees and comprises a series of square and rectangular planting areas divided by a network of paths and water channels or rills. A pavilion and water basins were sited off centre inside this enchanting chahār bāgh style of garden. Water was provided by a qanat, a tunnel dug into the hillside until it intersects with a water bearing strata. The water sourced from this spring would then flow continually. Qanats were used throughout Persia and the Middle East and also have been discovered in Morocco to supply the gardens of Marrakech with water.

Babur and the birth of Mughal gardens

Babur was the grandson of Timur (b. 1483–1530), he was 12 years old when he inherited on the death of his father. However, there was great upheaval at this time and the Safavid rulers gained control. Babur lost his base in Samarkand, so he travelled south over the Hindu Kush mountains and made Kabul his new capital. He made glorious gardens there. Fortunately his memoirs are preserved in the book called the Babur-Nama. In his youth Babur had either stayed or visited some of the Timurid palaces and gardens, and had been entranced by the gardens of his homeland in Samarkand as well as in Herat. In many ways he wanted to recreate them and the familiar chahār bāgh design in his new gardens. His journeys and conquests in Afghanistan and India are well documented, and he reveals in the memoires that wherever he went he preferred to rest in a garden. If there was not one nearby then he would have one made! Fortunately some of Babur’s gardens are described in this outstanding documentary book. For instance in 1504 he created a garden at Istalif where he realigned the stream and built a platform so that he could look over the plane trees, holm oaks and Judas trees growing on the slopes below. He was so overwhelmed by its beauty that he said ‘if, the world over, there is a place to match it when the Judas trees are in bloom, I do not know it.’56

His most celebrated garden was the Bagh-i-Wafa believed to be near Jalalabad, he says:

I laid out the Four-gardens, known as the Bagh-i-Wafa (Garden of Fidelity), on a rising ground, facing south … There oranges, citrons and pomegranates grow in abundance … I had plantains [bananas] brought and planted there; they did very well … The garden lies high, has running-water close at hand, and a mild winter climate. In the middle of it, a one-mill stream flows constantly past the little hill on which are the four garden plots. In the south-west part of it there is a reservoir, ten by ten, round which are orange-trees and a few pomegranates, the whole enriched by a trefoil-meadow. This is the best part of the garden, a most beautiful sight when the oranges take colour. Truly that garden is admirably situated!57

Babur founded a new dynasty in India, the Mughal, a name derived from their Mongol background. His descendants continued to create gardens, their gardens in India formed an integral part of the design of buildings, of palace or funerary monument. Babur had requested that he should be buried in Kabul, in the grounds of one of his beloved gardens. His wish was honoured and the gardens surrounding the tomb are now called the Bagh-e-Babur (the original name of these gardens is not known). Babur’s tomb and remnants of these gardens have survived.58 The walled gardens covered about 11.5 ha, and were designed on 15 terraces. It retained the geometric Timurid layout with a central axis, water channels and pools. It originally had a pavilion, but there were alternations over the years by later Mughal princes who came to honour their founder’s memory, this ensured that the tomb continued to be a place of veneration.

In the Islamic period (in the east and west) gardens were essentially walled enclosures which could include shady groves laid out in a symmetrical way. Planting included aromatic species and those that would please the eye. Pavilions were erected within to make the most of refreshing breezes and to enable the soul to relax amid the calming effect of surrounding flora. Above all, the Islamic garden is epitomized by the use of water, in pools or water channels and where possible with fountains playing. These elements, in hot climates were all the more admired and appreciated.

Notes

1. Hamilton, R. W. ‘Al-Mafjar, Khirbet,’ in Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land 3, Oxford, 1977, 754–765; Grabar, O. ‘Mafjar, Khirbat Al-’, in Meyers, E. M. (ed.) The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, Oxford, 1997, 3, 397–399.

2. This site was excavated by Herzfeld (published 1912) and some doubts have been raised about his interpretations.

3. These were: Al Cawthar, a River of Life, Salsabil and Tasnim (Ch. 75).

4. Koran 6: 141.

5. El Faïz, M. ‘Horticultural changes and political upheavals in middle-age Andalusia,’ in Conan, M. and Kress, J. (eds) Botanical Progress, Horticultural Innovations and Cultural Changes,’ Dumbarton Oaks, 2007, 120; Ruggles 2000, 18.

6. Al-Maqqari, Analectes I, 304, cited by Ruggles 2000, 17.

7. El Faïz, M. ‘Horticultural changes and political upheavals in middle-age Andalusia,’ in Conan. M. and Kress, J. (eds) Botanical Progress, Horticultural Innovations and Cultural Changes,’ Dumbarton Oaks, 2007, 120; Sanchez, E. G. and Lopez, A. ‘The botanic gardens in Muslim Spain,’ in Tzon Sie, L. and deJong, E. (eds) The Authentic Garden: A symposium on gardens, Leiden, 1991, 79.

8. Lambton, A. K. S. ‘The Athār wa Ahyā of Rashīd al-Dīn Fadl Allāh Hamadāni and his contribution as an agronomist, arboriculturist and horticulturalist,’ in Amitai-Preiss, R. and Morgan, D. O. (eds) The Mongol Empire and its Legacy, Leiden, c. 2004, 134.

9. Waqf-nāma-i Rabʿ-i Rashīdī, 15, cited by Lambton c. 2004, 135.

10. Subtelny, M. E. ‘Agriculture and the Timurid Chaharbagh: the evidence from a medieval Persian agricultural manual,’ in Petruccioli 1997, 110–111.

11. Subtelny, M. E. ‘Mīrak-I Sayyid Ghiyās and the Timurid Tradition of Landscape Architecture,’ Studia Iranica 24, 1995, 20, n.4.

12. Subtelny M. E. ‘Agriculture and the Timurid Chaharbagh: the evidence from a medieval Persian agricultural manual,’ in Petruccioli 1997, 112.

13. Subtelny, M. E. ‘Mīrak-I Sayyid Ghiyās and the Timurid Tradition of Landscape Architecture,’ Studia Iranica 24, 31.

14. Akhbar majmua (Ruggles 2000, 40).

15. Garcia, I. L. et al. Hallazgos Arqueológicos en el Palau de les Corts, Corts Valencianes, 1994, plan 10, figs 160–161.

16. Ruggles 2000, 81; Ruggles, D. F. ‘Madinat al-Zahra’, in Shoemaker, C. A. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Gardens: History and Design, Vol. 3, London, 2001, 839.

17. Ruggles 2000, 183.

18. Al-Maqqari, Analectes I: 371, 374. cited by Ruggles 2000, 210.

19. Al-Maqqari, Analectes I: 371, 374. cited by Ruggles 2000, 210.

20. Ruggles 2000, 196–197.

21. Al-Maqqari, Analectes I: 384, trans. D. F.Ruggles, in Ruggles 2000, 113–114.

22. Almagro, A. ‘An approach to the visual analysis of the gardens of Al-Andalus’, in Conan 2007, 65.

23. Acedo, A. C. The Alhambra and Generalife In Focus, trans. J. Trout, Granada, 2000, 106.

24. Almagro, A. ‘An approach to the visual analysis of the gardens of Al-Andalus’, in Conan 2007, 69.

25. Navagero, Viaje 46, cited by Ruggles 2000, 183.

26. Navagero, Viaje 47, cited by Ruggles 2000, 170.

27. Ruggles 2000, 203.

28. Ruggles 2008, 91.

29. 176 are listed by Harvey (1992, 78–82); this included several herbs and crop plants. His list features plants from six individual manuscripts. Ornamental species are listed by Sánchez and Bermejo (in Conan 2007, 75–93) taken from eight Andalusian agronomists and botanists.

30. Sánchez, E. G. and Bermejo, E. H. ‘Ornamental Plants in Agricultural and Botanical Treatises from Al-Andalus’, in Conan 2007, 77.

31. Mentioned by Abu’l-Khayr and Ibn al-Awwäm; Ibn Luyūn said that it was for decoration (Sánchez, E. G. and Bermejo, E. H. ‘Ornamental Plants in Agricultural and Botanical Treatises from Al-Andalus’, in Conan 2007, 79).

32. Sánchez, E. G. and Bermejo, E. H. ‘Ornamental Plants in Agricultural and Botanical Treatises from Al-Andalus’, in Conan 2007, 78.

33. Grabar, O. The Alhambra, London, 1978, 123.

34. El Faïz, M. ‘The garden strategy of the Almohad Sultans and their successors (1157–1900),’ in Conan 2007, 96.

35. Rawls, W. (ed.) Gardens Through History, Nature Perfected, New York, 1991, 73.

36. Firdausi, Shahnama, trans. D. N. Wiber; in Wilber 1979, 17.

37. Hafiz, 191, trans. K. H. Shaida, Charlestown, 2010.

38. Hafiz, trans. D. N. Wiber; in Wilber 1979, 17.

39. Sa’di, The Rose-Garden of Shekh Muslihu’d-Din Sadi of Shiraz, trans. E. B. Eastwick, 1979, 14.

40. Sa’di, The Rose-Garden of Shekh Muslihu’d-Din Sadi of Shiraz, trans. E. B. Eastwick, 1979, 13.

41. Omar Khayam, Rubáiyát 5, trans. E. Fitzgerald, London, 1995.

42. Omar Khayam, Rubáiyát 18, trans. E. Fitzgerald, London, 1995.

43. Subtelny, M. E. ‘Visionary rose: metaphorical interpretation of horticultural practise in medieval Persian mysticism,’ in Conan. M. and Kress, J. (eds) Botanical Progress, Horticultural Innovations and Cultural Changes,’ Dumbarton Oaks, 2007, 14–15.

44. Wilber 1979, 6.

45. Nizami, Khamseh, Iqbalnama, trans. H. Wilberforce-Clarke. Cited in N. M. Titley, London, 1979, 6.

46. Wilber 1979, 26.

47. Wilber 1979, 28.

48. Subtelny, M. E. ‘Agriculture and the Timurid Chaharbagh: the evidence from a medieval Persian agricultural manual,’ in Petruccioli 1997, 117; Subtelny, M. E. ‘Mīrak-I Sayyid Ghiyās and the Timurid Tradition of Landscape Architecture,’ Studia Iranica 24, 39–45.

49. Subtelny, M. E. ‘Agriculture and the Timurid Chaharbagh: the evidence from a medieval Persian agricultural manual,’ in Petruccioli 1997, 118.

50. Ruggles, private communication.

51. Moynihan 1979, 75.

52. Moynihan 1979, 52.

53. Subtelny, M. E. ‘Mīrak-I Sayyid Ghiyās and the Timurid Tradition of Landscape Architecture,’ Studia Iranica 2, 39–40; c.f. Ball. W. ‘The remains of a monumental Timurid garden outside Herat,’ East and West 31(1–4), 1981, 79–82.

54. Moynihan 1979, 52.

55. Hobhouse, P. Gardens of Persia, London, 2003, 94.

56. Titley 1979, 24.

57. Trans. A. S. Beveridge, The Babur-Nama in English, London, 1969, 208–209.

58. It is now a UNESCO site; cf. UNESCO website, World Heritage Centre.