3 |

Vicious versus virtuous cycles |

I often think of the song by Queen, ‘I want to break free’. I do want to break free but I don’t know how.

Aryan, 30

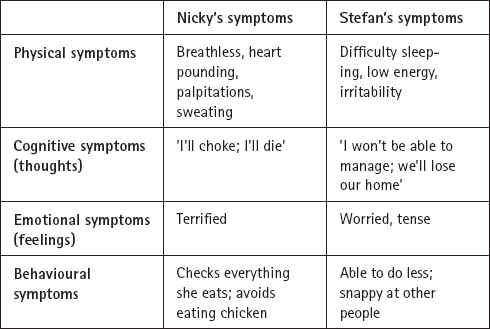

We have mentioned different symptoms of anxiety. When we look at them we can see that they fit into four different groups, or categories. CBT often starts by looking at all the different symptoms of anxiety you are experiencing and placing them into these four categories. The categories are:

• physical symptoms (what your body does when you get anxious);

• cognitive symptoms (how you think);

• emotional symptoms (how you feel); and

• behavioural symptoms (what you actually do).

Remember Nicky and Stefan from Chapter 2? Their symptoms can be summarized using these categories.

We will talk a lot more about thoughts in the next section, but for now will just say that thoughts are a crucial part of anxiety – even if you are barely aware of them. In anxiety, thoughts are often the result of a rapid weighing-up of a situation and coming to the conclusion that there is a danger. If you think there is danger, you will feel anxious. Thoughts will also trigger a reaction in your body, which means that you will start to experience strong physical symptoms, too – your heart may race; you might start to sweat and get butterflies in your stomach. If you feel this way, it makes sense that you would want to do something to make yourself safe. That may mean leaving a situation (or avoiding it in the first place may be even more appealing); making sure there is no danger, for example by repeatedly checking the doors are locked, or that you are not in danger of having a heart attack; or if you feel you need to stay in a situation, doing things that make you feel safer, for example, slowing down if you feel anxious when you are driving. However, the things that you do, your behaviour, will also influence your thoughts, feelings and physical symptoms, making the anxiety worse and worse.

Let’s look at Nicky’s story to see how this works.

As we saw, Nicky was sitting down to a meal with friends when she realized that she was being served chicken. Her immediate thought was, ‘Oh no, I might choke again’ (cognitive symptoms). As a result – and understandably – she started to feel extremely frightened (emotional symptoms). Her body started to react: her heart started racing, and she started hyperventilating – breathing very fast but feeling like she couldn’t get enough air in (physical symptoms). Unsurprisingly, her thoughts got even worse – she thought, ‘It is happening. I’m going to suffocate, I’m going to die’ (cognitive symptoms). As result she felt even more terrified (emotional symptoms) and her body started to react even more strongly; she found it more and more difficult to breathe (physical symptoms). She was in the grip of a full-blown panic attack. She rushed out of the room into the garden to try to get more air into her lungs (behavioural symptoms). Eventually she started to calm down, but she was absolutely clear that she would never go out to eat again unless she knew exactly what she was going to get, and that she would never go anywhere where there might be a chance she might be given chicken (behavioural symptoms).

Figure 3.1: The vicious cycle of anxiety applied to Nicky

We can see how Nicky’s thoughts about the dangers of eating out had become so frightening that the next time this arose she was bound to feel even more worried from the outset, and much more likely to make catastrophic misinterpretations. She started to avoid eating out, and checked all her food very thoroughly; she never had the opportunity to learn that eating out could be safe and enjoyable.

There are two important aspects to notice that come into all of the cognitive behavioural treatments for anxiety disorders.

Firstly, it is important to understand the specific cycles and connections that are operating for you. This is the reason why every evidence-based cognitive behavioural treatment for anxiety disorders described in this book starts with trying to understand your own specific cycles and connections. It uses the framework typical for that type of problem, but puts your own symptoms of anxiety into the framework. You will find that the cycles for the different anxiety disorders often overlap and are likely to include the following:

• Interpreting situations as dangerous when they’re really perfectly safe (see p. 35 above).

• Being hypervigilant to threat and danger (see p. 38).

• Avoidance of difficult situations and difficult emotions (see p. 67).

• Adopting counter-productive strategies: short-term solutions that may seem to help you in the immediate moment, but actually make the problems worse in the long term.

The second area of importance to understand is that the strong connections between your thoughts, feelings and behaviour mean that if you make a change in one area, it will influence the others. If you can change your way of thinking, that will change your feelings and your behaviour. If you can change your behaviour, it will change your feelings and your thoughts. Instead of getting caught in a vicious cycle, you can start to turn the links between symptoms into a virtuous cycle, so that the problem diminishes.

In Nicky’s case, for example, as her therapy progressed she learned how to recognize when she was catastrophizing and misinterpreting. She learned how to think in a more realistic way, and could say to herself, ‘Don’t be daft. You’re not choking, you’re just breathing too hard.’ As a result she started to feel much more in control of her anxiety, and could start to eat a bit more confidently and check the food in front of her less frequently.

Tips for supporters

• In general, feelings can be described in one or more simple terms, such as ‘scared’ or ‘upset’, whereas thoughts tend to be longer and more complicated: ‘If I go to the supermarket I’m going to lose control and have a panic attack and make an idiot of myself.’

• Try not to get too hung up on whether something is a thought or feeling – it is important to understand that all four categories are linked, and that it’s the connections between them that can make anxiety worse or better.

• Help the person you are supporting to spot the connections and see if you can get an example from their own experience that shows how the vicious cycle works.