5 |

Making changes |

It’s so frustrating. I know what I do is irrational but I can’t help the way I think.

George, 27

As we have seen, it is the vicious cycles that keep anxiety going. What this means is that in order to help change these into virtuous cycles we need to make changes. Unfortunately, although it may feel that this is easier said than done, it is a necessary step in recovering from all anxiety disorders.

Once you have worked out what factors are keeping your problem going, you need to work out how to change them. There are a number of ways to do this and they can be broken down into five separate steps. What these steps have in common is that they are all based on the idea that the reason you feel anxious is the way that you are interpreting events or situations. All the different ways of trying to make changes are just ways of helping you to get the information you need to test your interpretations of events, and learn to interpret them in a different way. In the different treatments described in Part 2 of the book, you will find that Steps 1 and 2 come first but Steps 3, 4 and 5 can be done in any order and are often carried out at the same time as each other.

You will see in the self-help programmes in Part 2 that they almost all involve you keeping records and monitoring some aspects of your anxiety. While it may at first seem strange to spend time ‘analysing’ your anxiety, there are three important reasons for you to monitor it:

1. Self-monitoring in real-time as you go about your daily life will give you an understanding of what is keeping your anxiety going.

2. Self-monitoring is an important first step to change. It helps you gain some distance from your thoughts, step back and view them objectively, and then take some time to think about them and evaluate them rather than automatically assuming that whatever you are thinking is ‘the truth’. Being able to view your thoughts objectively rather than assuming that they are reflecting the truth is important because it helps change your behaviour.

3. Getting your thoughts down helps stop them go round and round in your head. People with anxiety disorders spend a lot of time thinking, thinking, thinking, thinking (this is often called ‘ruminating’). Being able to interrupt that incessant thinking, by getting some of it down, can be really helpful.

It may seem obvious, but you need paper to monitor. Some people buy a ‘therapy’ notebook so they can keep everything together. You will also need a pen, and a ruler will be useful, too. Or you could use an iPad or other tablet. Whichever you use, you should be able to carry it around with you so that you can write things down as you go, in real time.

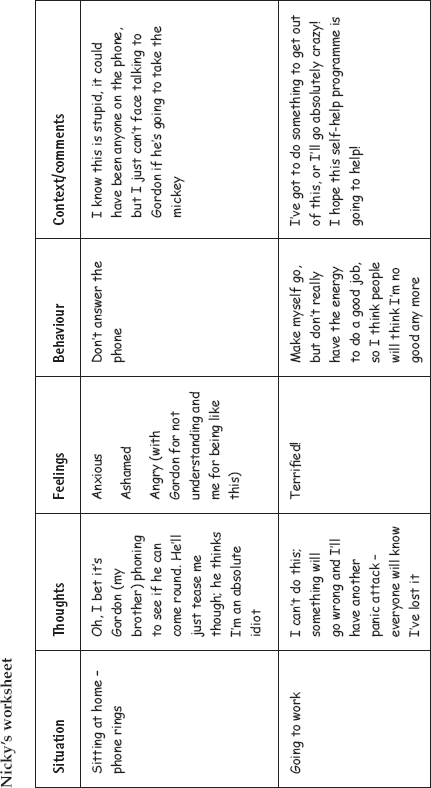

Worksheet 5.1 is an example of a typical record sheet that you are likely to use when working on a particular anxiety problem, and you will see variations on this in the different chapters in Part 2. Nicky’s completed record sheet shows what kind of information to insert.

If you have learning difficulties such as dyslexia, you may be put off self-monitoring. Please don’t be. There is more than one way to self-monitor. For example, you can draw pictures, use Dictaphones, or you can invent something that you think will have the same effect – it doesn’t matter. It is not important if you make spelling mistakes, or only write one word. What is important is that you get down what is going through your mind so that you can view your thoughts objectively.

It is true that writing things down initially makes some people feel worse. This can happen for a variety of reasons. Sometimes, writing things down makes people feel bad because they realize the extent to which their anxious thought is dominating their life. Sometimes it makes people feel foolish because rationally they know that their fear is excessive, but they still remain fearful. Sometimes people feel ashamed. For every person who feels this way, there is another who finds writing things down a real relief, and the beginning of change. They feel less confused. Even if it does make you feel worse, bear in mind that the feeling is likely to pass. Remember how bad your anxiety makes you feel – monitoring is a necessary first step to change.

Some people think that writing things down will make bad outcomes more likely. Even when people without anxiety disorders are asked to write down that something bad will happen to their loved ones, the majority refuse to do so because of the fear that it could somehow cause the bad thing to happen. If you hold this belief very strongly, then you can do some behavioural experiments to address the belief before you start self-monitoring (see p. 62.) In the meantime, try writing down what you can, and perhaps use symbols or make up a code if you don’t want to write something in particular.

It is important to keep your monitoring sheets in a safe place. If those around you are curious, especially those close to you, make an agreement that you will tell them about what is going on when you are ready, but make it clear that you would like them to give you the space at the start. Some people complete their monitoring sheets in the bathroom or somewhere else private so they can monitor in real-time without anyone asking difficult questions.

In reality, it can sometimes be too difficult to monitor in real-time without anyone noticing and there will be times when it has to be done a bit later, and occasionally at the end of the day. This is not a problem, as long as you follow the principle that what you are trying to do is work out your thoughts, feelings and behaviour at the time of feeling anxious. If there is too long a gap between the situation that made you feel anxious and your recording it, you will forget the immediate thoughts and intensity of emotions that characterized it. Your thoughts in retrospect are interesting, but writing things down too long after the event will also prevent you from having the opportunity to change when the anxious situation is actually taking place.

It is no surprise that re-reading what you have written will at times be difficult and emotional. After all, anxiety disorders are emotional problems. However, it is important to do this at the start of your next session either alone, if you are using this self-book without any support, or with your supporter or therapist. Reviewing your monitoring sheets will provide you with important information about what is keeping your problem going and how to make changes.

CBT involves you receiving correct factual information. Fact-finding or ‘psychoeducation’ can be enormously helpful (and we hope that this book is a good start) because it provides a more balanced, unbiased perspective on what you are feeling, and helps to make sense of your problems. It should give you information about the facts rather than the feelings of the situation. It will help most if the information feels personally relevant to you.

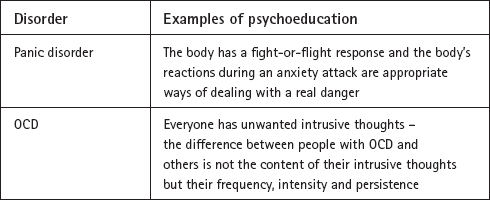

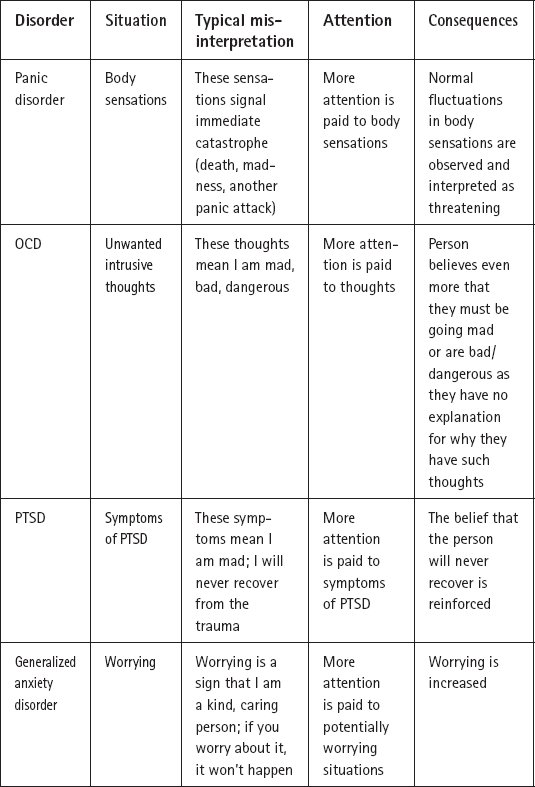

Many of the self-help programmes in Part 2 contain some psychoeducation or factual information. Typical examples of psychoeducation for each of the anxiety disorders is given in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Psychoeducation for anxiety disorders

Across the anxiety disorders, behavioural experiments are used to try to gather personally relevant information to help change misinterpretations into more realistic interpretations.

A behavioural experiment is a way of gathering information to help you test out which is true – your anxious interpretation of events, or a more balanced one. It is also a way in which you can see how the way that you behave affects your anxiety. Importantly, it provides information that is relevant to you, and it helps what you rationally know to be true in your head to also reach your heart. When cognitive therapy was first developed, behavioural experiments were emphasized as an important way to obtain new evidence to help people change their way of thinking. Nearly forty years later, their importance is still undiminished and all the treatments for anxiety use such experiments.

There are different types of behavioural experiments, and the chapters on specific disorders will set out those that are relevant for that particular problem. We will just give a couple of examples here for illustrative purposes.

For example, one form of behavioural experiment is to carry out a survey. In OCD people may think they are bad because they have unpleasant ‘intrusive’ thoughts, for instance about harming people (see Chapter 11). Almost everyone has such thoughts, but the best way for someone with OCD to believe this is to find out for themselves. So the person with OCD may be asked to do a survey – to ask other people, particularly people they like and respect, whether they have unwanted intrusive thoughts about harming people. They will find out that a lot of people do have such thoughts – even good people. So the behavioural experiment – the survey – has shown them that it is normal to have such thoughts, and having them does not mean that they are ‘bad’.

For another example, in panic disorder a person may fear that changes in their breathing mean that they are going to have a heart attack and die. This thought is so frightening that it makes their physical sensations worse, and the belief gets even stronger. It’s hard to believe that it’s your thoughts that are causing such drastic sensations! In a behavioural experiment, a therapist might try to produce a panic-like state by asking someone to breathe very heavily. This will produce normal physical changes in breathing, but the person who panics will start to interpret them by thinking they’re having a heart attack and become terrified. The therapist can help the person to see that it’s their interpretation of the symptoms which causes the anxiety – after all, it’s unbelievably unlikely that you’d suffer a heart attack just at the moment the therapist asked you to breathe a bit more heavily. See Chapter 7, p. 173 for a detailed description of this process.

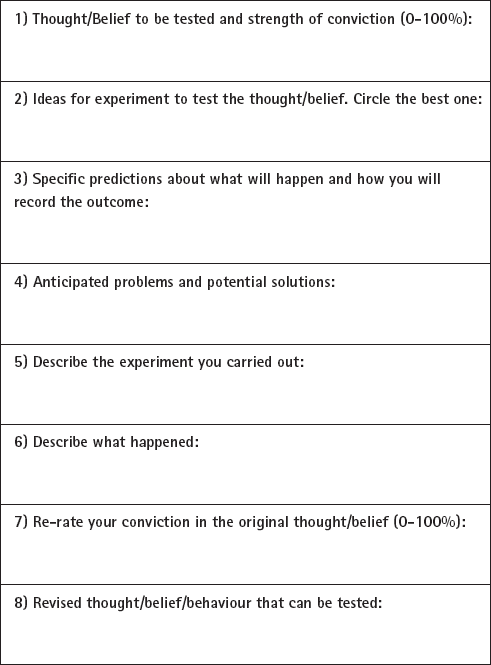

You can use Worksheet 5.2 to work out how to carry out a behavioural experiment. It is included here because some of the chapters in Part 2 refer to experiments and it may be useful to have such a worksheet to help you. The same worksheet can be used whether you are testing a belief related to panic disorder, OCD or any other type of anxiety problem. If you want to modify the worksheet to fit your individual problems better, you can do so.

Before looking at the worksheet however, let’s talk a bit about ‘predictions’. In anxiety, when we have an anxious thought we are essentially predicting what is going to happen. If you are worried that your children might have an accident while they are away you are in some sense predicting that they will have one. If you are socially anxious and worry about going to a social event, you are predicting that people won’t talk to you, or that they’ll laugh at you. Whenever we worry there is a hidden prediction, which it can be very helpful to identify. Worksheet 5.2 asks you not just to say what your belief or worry is, but what the prediction that follows from it is. In this sense the behavioural experiment is very useful – you are going to see if your prediction comes true or not, just like a scientist testing a theory.

Worksheet 5.2. Behavioural experiment sheet

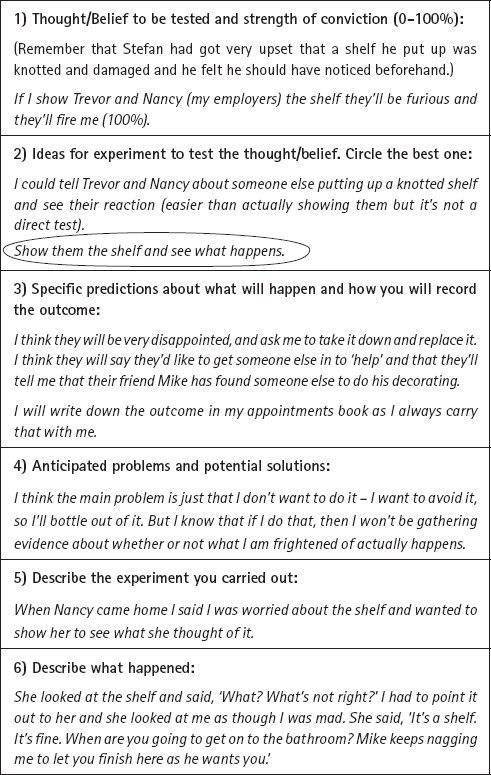

Example: Stefan’s behavioural experiment worksheet

Experiments can also be used to help people reduce their avoidance behaviour, since avoidance in many cases keeps the anxiety disorder going. Reducing avoidance is an important part of therapy for a number of reasons. Firstly, we know that although when you avoid things you might get an immediate sense of relief, your anxiety usually gets worse in the long term. It is as if by choosing to avoid a situation you are giving yourself the message: ‘You were right to avoid that, it would have been awful.’ Avoidance means that you never get the chance to check whether the bad things you are afraid of might happen – or not. Avoidance also means that your life becomes restricted – you avoid more and more and don’t live your life in the way that you’d like to. At some point you might also start to avoid your own emotions (for example by getting drunk). One of the reasons that avoidance keeps anxiety going is that it can prevent you from obtaining the information that might change how you interpret events. In many cases, avoidance is a real problem in its own right because it is so restrictive. Many people with anxiety disorders are unable to have friends round to their houses, cannot walk freely about town, cannot shop to buy objects that they wish to buy and essentially become prisoners. Why? Because they’re avoiding situations that make them anxious. Reducing avoidance is part of treatment and so behavioural experiments that help the person with anxiety to find out what happens if they stop avoiding certain situations are used in the treatment of all anxiety problems. For some anxiety problems, such as specific phobias, ‘exposure’ is used; this exposes the anxious person to a feared situation so that they can get used to it; ‘hierarchies’ are built in which they start by getting used to a situation that provokes some anxiety, but is manageable, and they slowly build up towards putting themself in situations that at the start of treatment would have been unthinkable for them to endure.

There are some other behaviours that might also be considered unhelpful or counter-productive if you are anxious. For example, if you have social phobia, avoiding eye contact is highly likely to be counter-productive as someone who doesn’t make eye contact is often perceived as odd or unfriendly. A behavioural experiment targeting this counterproductive behaviour would set out to discover what happened (in terms of emotions, behaviour and the situation) when eye-contact was not avoided.

One of the most common fears among those with an anxiety problem is the fear that the anxiety problem is so severe that it will make the person ‘go mad’. This commonly links to beliefs about losing control, or that having the anxiety disorder is a sign of madness. To challenge such beliefs, a common behavioural experiment would be to plan for the person to become very anxious, as anxious as humanly possible, and see if they become ‘mad’. A discussion would immediately follow as to what ‘madness’ might look like – babbling, incoherence, loss of movement might all be part of the person’s idea of going mad. In reality, what happens when a person becomes very anxious is that . . . they become very anxious! They do not babble, lose movement or become incoherent. So, doing a behavioural experiment like this provides the anxious person with important and valuable information that high levels of anxiety do not cause madness. Such an experiment would then be repeated in a range of situations so that more and more evidence is gathered that anxiety does not cause madness, which helps to reassure the person that the results of the first behavioural experiment were not a one-off. As you are reading this, you may be feeling more reassured, having been given the information that anxiety does not cause madness but you might still be a bit afraid that you may be an exception to this rule. Many of the chapters that follow include information on behavioural experiments and you will need to conduct such experiments in order to gather personally relevant information about your beliefs and interpretations of events.

We briefly discussed the importance of cognitive biases earlier (p. 38). If something is important to you, you are more likely to pay close attention to it. This is natural and usually helpful. It is why our loved ones absorb so much of our attention, and why we notice (sometimes) if our friends appear sad or disheartened. It is because people with anxiety disorders are so preoccupied with the possibility of something bad happening, they pay much closer attention to possible threats than other people. Sadly, this has an unfortunate consequence, since paying attention to threat means that you see more and more potential threats and become more and more anxious.

The nature of a specific threat and the type of object or situation that capture attention will vary depending on the anxiety problem. Some examples of specific threats are shown in Table 5.2. This table is the same as Table 2.1 but with additional columns showing how paying attention to the perceived threat can make things worse.

Table 5.2: Examples of specific threats

When you have an anxiety problem, your attention to specific threats becomes part of the problem and traps you in a vicious cycle, and your belief that threat and danger is all around you is reinforced.

Almost all the different CBT approaches to anxiety include ways of helping people to stop paying attention to threat. In panic disorder, for example, another behavioural experiment might be conducted that asks someone with panic disorder to focus on their bodily sensations and to then switch to focusing their attention on something interesting in the external environment. What tends to happen is that the anxious person will notice their bodily sensations more when they focus their attention on them than when they do not. This helps the person come to understand that their problem is not that there is something wrong with their body and that they are vulnerable to something terrible happening but rather that their focus of attention is the problem.

In some cases, psychoeducation is also used to help people understand that part of the problem is their increased attention to threat. To use an analogy, if you buy a particular car, you are likely to suddenly notice that lots of other people have the same car. You might even think that the number of cars has increased but accept that it is more likely that in fact you are just noticing the cars more. There are a number of specific exercises that can be done to help shift the focus of attention away from a perceived threat. The kind of exercise that you do will depend on the nature of the anxiety problem, and many of the chapters on the specific disorders will give examples.

Do you remember that Nicky’s brothers had started to tease her, and that she was worried that people would think she was pathetic? In social anxiety, it is common to focus our attention on ourselves. Every time Nicky saw her brothers she would be very aware of how she was coming across. She would notice that her voice was trembly, and that she felt flushed. The more she paid attention to these signs, the more anxious she got, and the more pathetic she felt she was being. With help from her supporter, Nicky realized that this was making the situation worse. Together they decided that what Nicky should do was to concentrate her attention on other people, not herself. So when she met other people she made herself think about what they were saying and doing. Although her attention automatically went to how she was feeling, she decided that she would say ‘switch’ (short for switch attention) and try to go back to thinking about them. With her brothers she made this easier by getting herself to count how many spots they had, or whether they needed a shave!

We have talked about how people pay attention to threat. What people are doing is scanning the environment to see if there is anything threatening in it. Then if there is anything that is at all uncertain, the sufferer interprets it as dangerous rather than as neutral. This means that the combination of increased attention and the interpretation leads them to think of a great many things as scary. A fundamental lesson of cognitive therapy is that thoughts are not facts. This cannot be overstated. All the techniques we talk about below show that our thoughts are just that: they are thoughts about the situation, not facts about it.

In thinking about anxiety, we often talk about the probability of danger – is this situation threatening or not, and if so, how bad a threat is it? There is an ‘anxiety formula’ that helps to show these and other relevant factors that determine how anxious you might get. The tendency to misinterpret things in an anxious way is relevant to all these four factors.

This formula described by Salkovskis (1996) suggests that the amount of anxiety we feel will depend on two things:

• How likely you think it is that something bad will happen (probability of harm); multiplied by

• How bad it will be (seriousness of harm).

If we think that something is very likely to happen, and that it will be very bad, we are likely to feel very anxious indeed. Even if this is so, then there are situations, people or coping mechanisms that can make it better:

• Is there anyone around who would help us, and prevent the harm (rescue)? and

• Are there things that we ourselves can do to cope (coping)?

When we are anxious, we tend to overestimate the probability of harm (i.e. think it is very likely something bad will happen), overestimate the seriousness of harm (i.e. think it will be very bad) and underestimate our ability to cope or be rescued (i.e. there’s nothing that will help). As a result our anxiety levels get very high.

For example, it may be that we are overestimating the risk of going mad by having a panic attack (the risk is zero), or catching AIDS from a cashpoint (the risk is zero) or a traumatic event occurring again (in this case, the risk may not be zero but is unlikely to be as high as we are estimating).

It is therefore important to make realistic estimates of the probability of harm, and the seriousness of harm (or danger) and of our ability to cope with such challenges. A common goal of the treatments for anxiety problems is to help people make more realistic estimates in each of these areas through fact-finding, experiments and by helping people step back and examine how realistic their thoughts and estimates are when looked at objectively.

Nicky’s ‘anxiety formula’

When Nicky was worrying about eating chicken, her ‘anxiety formula’ was as follows:

• Probability of harm: I’ll eat some chicken and I’ll choke – at the moment I think this is 100% likely.

• Seriousness of harm: If I do choke, then I’ll suffocate and die – I think I believe this almost 100%, too, even though I didn’t last time.

• Rescue: No one will be able to help me – I know it’s stupid to believe this, since lots of people were there to help me last time, but I still do!

• Coping: I won’t be able to cope – I think I believe this pretty strongly, too – I’ve been such a wimp in the past.

• Overall anxiety: Very high.

As a result of looking at each of the parts of the anxiety formula separately, Nicky could understand why she was feeling so anxious. She could also see that there were at least two items that she could think about differently. She knew that she hadn’t suffocated and died when she had eaten chicken in the past, and she also knew that other people were willing to help her if needed. As a result, she was able to see that maybe the situation was not quite as bad as she had been thinking.

It is also important to emphasise the factors that refer to our ability to cope, and the help that is around us. When we are anxious we not only overestimate the probability and seriousness of threat; we also underestimate our ability to cope, and the possibility that other people will be around to help and support us. This book intends to give you ways to help you cope better, but it is also possible that you are already coping much better than you think. It might help you to think about times when you have coped with difficult situations, and remind yourself of the ways in which you did it. If you are working with a supporter who knows you well, ask them if they can remember times when you have coped. Make a note of these times and the qualities you displayed so that you can look at them and remind yourself of them when you feel you cannot cope.

It might also be worth keeping a record of what happens in your daily life – many of us do cope with difficult and complicated situations without even realizing that we’re doing it. Try to tune in to your positive coping qualities and make them feel like a real part of you.

Some people with anxiety might rely too much on other people because they doubt their ability to cope alone. If you identify as someone who tends to do this, then it would be better for you to work on your faith in your own abilities. Others ignore that other people are willing to help. If this is you, then think about who is around who could help or ‘rescue’ you in difficult times. This might be friends or family, but it could also be more official sources of help, like the Citizens Advice Bureau (CAB), or self-help organizations such as those listed in the Appendices at the end of the book.

In Chapter 3 we talked about how we make a number of ‘cognitive errors’ in our thinking when we are anxious. A particularly important one is ‘catastrophizing’. An example of catastrophizing might involve being afraid that we will be struck by lightning if there is a thunderstorm while we are out walking. (In fact, the chances of being struck by lightning are one in 500,000, and the chance of being killed by lightning is one in 10 million.)

You probably know all too well about ‘catastrophizing’. If we are catastrophizing, we have a tendency to interpret situations as disastrous, and to expect the worst outcome rather than the most likely one.

If you find that you are catastrophizing, one way to tackle it is by using the anxiety formula on p. 73. When we catastrophize, we are saying that something bad will definitely happen, and it will be awful; that no one will help and that we can’t cope by ourselves; that what happens will be disastrous.

By looking at each element of the formula separately, you can scrutinize each step of this prediction and arrive at a more balanced prediction of what is likely to happen.

Sometimes working out the probability this way is helpful to put our fears into perspective and therefore reduce our anxiety. Sometimes though, people respond by saying, ‘I can’t take the risk of the catastrophe occurring, even if it is 1 in 50 million and there is more chance of winning the lottery’ (which is 1 in 14 million in the UK).

The problem of aversion to risk taking needs to be addressed. By ‘aversion to risk taking’ we mean that you might find it so frightening to take risks that you just cannot face it. Even though you might realize that it would be better in the long run to do something, you cannot bring yourself to do it. So you need to learn to take risks!

There are different ways of addressing the aversion to taking risks. The best is to do a ‘risk taking’ behavioural experiment that involves a small risk to see if this turns out as bad as predicted.

Think about risks that you take every day. There is a 1 in 43,500 chance of dying in a workplace accident, a 1 in 2,300,000 chance of dying falling off a ladder, a 1 in 2,000,000 chance of dying after falling out of bed, and a 1 in 8,000 chance of being killed in a road accident. Nevertheless, we do still go to work, climb a ladder to change a lightbulb, go to bed, and travel in cars. Why? The reason is that the quality of our life if we avoided all risks would be extremely poor. We decide to take the risks because otherwise we would become housebound (and anyway, there are dangers in the home, too).

It is impossible to guarantee 100 per cent that you and your loved ones will always be safe. However, it is easy to guarantee that you will continue to have a problem with anxiety if you live your entire life trying to reduce all risks in order to protect yourself and loved ones from harm. You may want to consider that the best way to protect your children is to overcome your anxiety problem so that you and they together can make informed decisions about risk and harm, in order to protect yourselves properly as you all go about your daily lives.

Remember that we said earlier that thoughts are not facts. They are our interpretations of events, not the only way to see things. One way we can learn to tackle anxious interpretations is to subject them to a process of looking for evidence for and against them. Do you remember the idea of a scientist looking for evidence? When you are trying to think whether your anxious interpretations are real or not, try to work through the following questions:

• What exactly is my negative thought?

• What is the evidence in favour of this interpretation?

• What is the evidence against it?

• What would I say to a friend who said they were thinking something like that? Would I agree or would I be able to put a different view forward?

• What would a friend say to me if I asked them how they saw it?

• What is the alternative view?

• If I were a scientist, which theory would convince me more? The theory that it is true or the theory I am worried it is true?

• If I were in a court of law, would I have convinced the jury that the anxious view is the right one?

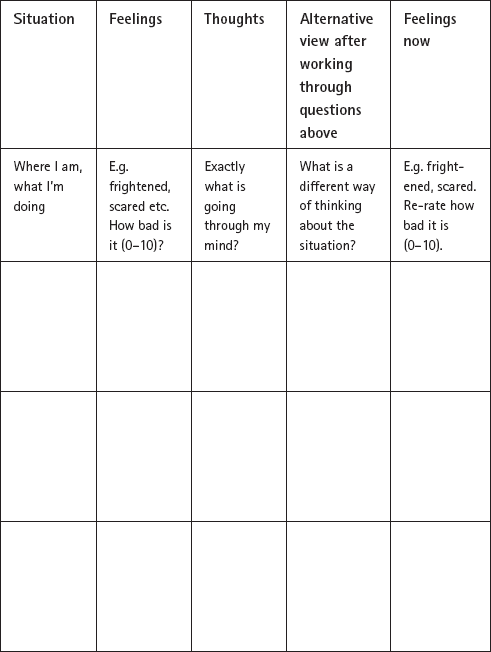

Using these questions, use worksheet 5.3 to write out your thoughts, and an alternative view when you have questioned them.

Worksheet 5.3. Taking a new perspective

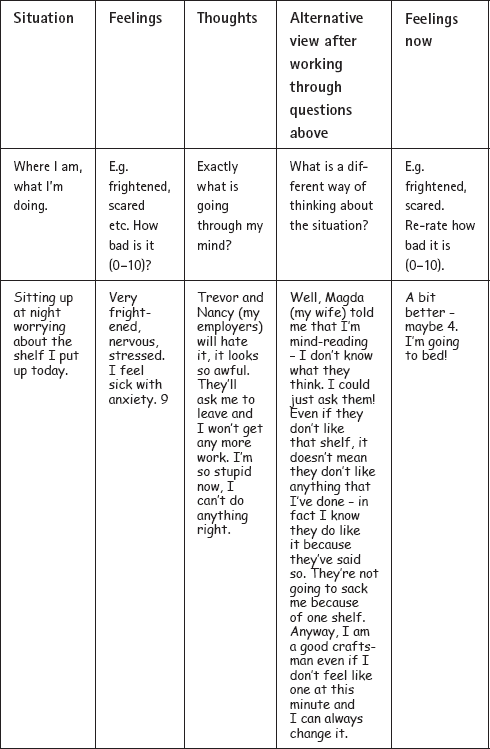

Remember in Chapter 3 we described Stefan’s worry about the shelf that he’d put up in his client’s house? Here is how Stefan filled in the form.

Stefan’s new perspective worksheet

Sometimes the way that we think is not in words, but in pictures or images. It might be that you are worried that your partner or child will be involved in a terrible accident on the way home. You might not say to yourself, ‘They’ll have a crash’ – you might just see a picture in your mind of a smashed car and a shattered body. These images can cause us terrible distress and anxiety, and can be even more distressing than words or thoughts.

For instance, when Stefan was worrying about losing his job and his home he had a very strong picture of himself and his wife walking through the rain carrying their crying children – a truly upsetting image. When Nicky was worrying about choking she had an image of herself lying on the ground gasping for breath with her face turning from red to blue.

Some of the treatments described in the second half of this book involve trying to reduce these troublesome images. The most well developed of these treatments involving changing images are for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and social anxiety, but they also have a role to play in many of the other disorders.

The first step is to be aware of what the image means to you. For instance, one of the authors was talking to a friend about their marriage difficulties. The friend said that when she thought she and her husband might split up she had an image of herself sitting alone in a dressing gown in a dark room, with the curtains still pulled, and mess and dirt everywhere. She realized that the meaning of the image was that she would go to pieces if they split up, and would have no friends and be completely alone and unable to function. As soon as she realized this, then she was able to say to herself, ‘OK, even if the worst comes to the worst I will be able to cope. I’ll be sad, but my life will carry on, and I’ll still go to work and have friends and interests. I won’t look like this.’ It is therefore important to be aware of your own images, and the meaning you place on them, so you don’t go along with the meaning without realizing you are doing it. Once you have put the meaning into words, you can use the questions on p. 78 to help you to think differently.

• Make sure that you understand the difference between thoughts and interpretations and facts.

• Encourage the person you’re supporting to work through techniques in a detailed and thorough way.

• Let them know that at first it is very difficult to think of different ways to view the situation – this is where you come in! As time goes on the process will become easier, and they should be able to think of more and more for themselves.

We have now reached the end of Part 1.

We have outlined the key principles of CBT, which have guided all the specific interventions that will be discussed in Part 2. We introduced some case studies to demonstrate how some of these common principles work in practice and discussed some common treatment techniques. You should now have more of an idea of the type of anxiety problem you’ve been experiencing and which chapter(s) will be the most helpful to work through Part 2.

In Part 3 we will come back to common issues in anxiety. We talk about some of the other things, such as your mood and your relationships that play an important part in anxiety. We show what happened to Nicky and Stefan, and how they managed to overcome their anxiety and plan for the future.