11 |

Obsessive compulsive disorder |

On p. 10 of Part 1, you read a brief description of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD); the flow chart on pp. 14–15 helped you see whether it might be relevant to you. If you think you might have OCD or you know that you definitely have this problem, then working your way through this chapter should help you to better understand why you have OCD, what might be keeping it going, and how you can recover. Change is not easy but it is possible and the changes and strategies we will set out in this chapter have been shown to work; many people with OCD who have this kind of cognitive behavioural therapy are able to recover fully and lead happy lives.

Many people with obsessive compulsive problems suffer in silence and it takes an average of seven years before they seek help. Many, possibly including you, will read books about OCD, gather information on the internet and try to help themselves without going to their GP. If that sounds like you, then we hope the self-help programme set out in this chapter will help but we would also like you to know that you are not alone. Many people have these type of problems and, most importantly, with the right type of help you can completely recover. The type of problems people with OCD have is varied – many have the classic ‘washing’ and ‘checking’ forms, but it can take other forms as well. It is impossible to cover all of the forms of OCD in a single chapter but we will introduce you to the idea of obsessions and compulsions, the treatment that has been shown to work, and recommendations for further reading.

Most of us have thoughts that come into our heads which we think are strange and unpleasant. For some people, though, these thoughts completely take over and cause great distress. At this point we talk about people having ‘obsessions’. Obsessions are thoughts that come into our heads and will not go away, even though we don’t want them there and find them unacceptable or even repulsive. It’s not just thoughts – obsessions can also take the form of images – pictures in your mind, or impulses – a strong urge to do something, usually something horrible. If we have obsessions we might feel tortured and terrified by our thoughts, images or impulses. Often they are about our very worst fears, and are completely at odds with our values and our views of how we should be as a person. As a result, obsessions tend to be around three main themes, which are all completely unacceptable to the person having them. These are aggressive, sexual or blasphemous thoughts. Let’s look at Mo, Etay and Fiona’s stories below.

Mo had aggressive obsessions, and had lots of images of himself causing harm to other people – including old people, children or relatives. He hated himself for having these thoughts, and was desperately worried by them. He was particularly frightened that he might go mad and strangle his elderly mother, who lived with him and his family.

Etay was a happily married man, but he kept having images of himself having sex with inappropriate partners, including elderly people, his mother-in-law and children. These thoughts were absolutely horrible for him.

Fiona was a quiet and gentle person who was raised as a Catholic. For the past ten years she had been unable to pray in church because whenever she said a prayer, she would have the thought ‘you’re a fake; you don’t mean it; you don’t believe in God’. She could not abide having such thoughts in such a holy place, and had to stop going to church or meeting any of her church friends.

Obsessions can also take many different and more complex forms. Some people may fear taking on the characteristics of others, for example becoming stupid, homeless or ugly. Others may have a preoccupation with whether they have done the right thing, for example the ‘wrongness’ of stealing paper towels. Some need to make sure that everything is done with symmetry, order and exactness. Others may be worried about becoming contaminated through contact with repulsive or germ-laden situations like dog mess; some people may feel contaminated without even having physical contact, for example by a person who has betrayed or humiliated them. No two people are exactly alike, but there are general ideas that help us to understand the nature of all obsessions and how they should be treated. We will describe these throughout this chapter.

It’s not just the obsessions themselves that cause the distress; there is another part to the story. The thoughts are usually so unacceptable, and you are likely to feel so bad that you feel an overwhelming need to do something to try to make things ‘all right’. We call what you need to do ‘compulsions’ or ‘neutralizing’. Compulsions typically have three purposes: firstly to reduce the chance that the things you are thinking about will happen, secondly to calm your anxiety down, and thirdly to make sure that if something bad does happen you have at least done everything in your power to prevent it. Compulsions are often repetitive and tend to be done in a very particular way (e.g. always doing things in threes, twos or nines, or repeating particular phrases to yourself), and they can take over your life. They are often unconnected in any real way to the feared event that you are trying to prevent – for instance, someone may need to make sure the hangers in the wardrobe all face the same way, in order to prevent their wife having an accident.

The most common compulsions are:

• repeated checking, or washing and cleaning things;

• doing things in the ‘right’ order and the ‘right’ way;

• hoarding objects;

• carrying out elaborate rituals that involve tapping, touching or staring;

• seeking reassurance and asking the same question over and over again, for example: Did I lock the door? Is Joe OK? OCD has often been called the ‘doubters’ disease’ for this reason;

• repeating phrases in your head or not physically moving while you’re having a ‘bad’ thought.

Sofia’s story

Sofia is a 25-year-old architect who lives with her partner. She is terrified of germs and becoming seriously ill and she worries a lot that she will get a serious illness such as HIV from accidentally sitting on a dirty syringe or stepping on one in the street. She is always on the lookout for used needles and avoids walking through the rough areas of town where she might come across them. She refuses to take the London Underground to work, but instead takes the bus and walks, even though it adds an extra twenty minutes on her journey. She is very close to her grandmother but worries that she will accidentally cause her harm, e.g. by giving her food poisoning if she bakes a cake. She repeatedly checks what she has put into any food she is cooking and doesn’t trust her own memory. She has avoided seeing her grandmother recently as she worries that she could be unwell and might pass that on to her, which could prove fatal. She washes her hands a lot, and showers in hot water for a long time as she feels she needs to scrub all over at night to get rid of the germs that she has accumulated during the day. She is managing to go to work, do her job and keep her relationship with her partner going, but feels very tired and stressed all the time because she’s so worried. She realizes that her worries about germs are excessive, but she cannot stop having them.

In Part 1, we talked about how cognitive behavioural therapy focuses on what is keeping the problem going. We can help give you a head-start on trying to understand what keeps your problem going by telling you about the understanding that therapists have that is supported by research. The understanding about what keeps OCD going in general is that everyone has odd thoughts and images from time to time. However, if you have OCD you almost certainly see these thoughts as being personally significant so, unsurprisingly, they are upsetting and frightening to you. The meaning you place on the thoughts leads you to feel the need to try to do something to stop them, or the anxiety that they make you feel, or to prevent harm. Some of what you do to stop the thoughts, reduce anxiety or prevent harm is likely to be backfiring and may actually be keeping the problem going. For example, if you are repeatedly checking the stove to stop your worry, reduce anxiety and prevent a fire, then you will be experiencing more doubt and worry than if you only check once (see p. 379).

The importance of the personal significance people with OCD place on their thoughts is illustrated by Aaron.

Aaron, 21, had thoughts about raping children. He was repelled by such thoughts as he had younger sisters and he thought that it meant he was a wicked, evil person who was not safe to be around children. He tried to block out these thoughts. He started staying away from his sisters and even felt unable to go to work. Staying away from work in fact meant he had more time to focus on his thoughts. Even pictures of children would trigger the thoughts. He had so many of them he could only conclude that he was indeed a wicked person who subconsciously wanted to do these dreadful things. Aaron had OCD.

Ben, 21, had the occasional thought about raping children. He didn’t much like having these thoughts, but he didn’t really pay too much attention to them – he knew they were just random thoughts that popped into his mind and he was busy trying to find a job. When he had the thoughts, he just distracted himself – he knew he was a good person who would never harm children and he didn’t react at all when he had the thoughts – he didn’t feel the need. The thoughts faded of their own accord.

The two examples above show how it is not having the thoughts about raping children that made Aaron have OCD since Ben also had them – it was the interpretation of the thoughts and the associated behaviour that meant that Aaron had OCD while Ben did not.

Below are some typical examples of the personal significance/misinterpretations people place on thoughts/images:

1. Having an image of harming your child means that you are a dangerous person.

2. Having a thought about a sexually inappropriate repugnant act means that you are going crazy (mad).

3. Having an impulse to blurt out a swear word in church means that you are bad and evil.

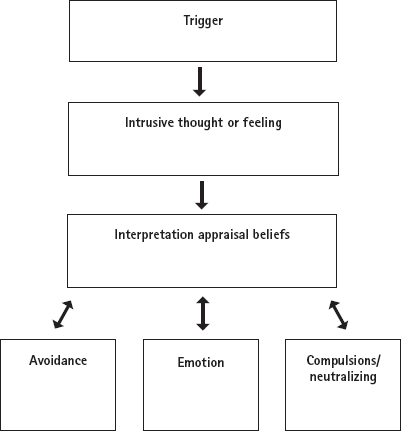

The way we interpret our thoughts can make a huge difference to how we feel and how we react or respond to them. If we interpret unpleasant or disturbing thoughts as being true or meaning something, unsurprisingly, we will feel highly anxious, probably guilty and want to act to reduce our anxiety or prevent harm. For example, if we interpret having a fleeting thought of pushing someone in front of a train while we’re standing on the platform as meaning that we are a potential murderer, firstly, it’s not hard to imagine that we would feel terrible, frightened and repelled and, secondly, as we would naturally want to stop feeling that way, we’ll want to stop these thoughts, or if we can’t do that, to cancel (or ‘neutralize’) them in some way. Responding to intrusive thoughts by avoiding situations, carrying out compulsions or other behaviours, such as ‘rewinding’ thoughts to ‘cancel’ them out, is what is likely to be interfering with your life and stopping you from enjoying it to the full; it is also likely to make your thoughts very important to you so you become trapped in a vicious cycle (as described earlier). This is shown in the diagram opposite.

Figure 11.1: The maintenance of OCD

The CBT approach to OCD can be applied to all forms of OCD. To help you to apply it to your own personal situation, let’s look back at Sofia’s story on pp. 349–50. Let’s look at how her OCD symptoms fit into the framework above:

Figure 11.2: The maintenance of Sophia’s OCD

If Sofia knew that instead of being careless, she was in fact extra careful, that instead of dangerous, she was actually a very safe person to be around, that instead of having a weak memory, she only believed herself to have a weak memory, and that instead of needing to be more responsible, she realized that she is already too responsible, then she would be able to recover from her OCD.

If you have OCD, you are likely to believe that there is something significant – and possibly sinister – about your completely natural but unwanted intrusive thoughts. You may fear that the thoughts mean you are going mad, or that you are bad or dangerous.

The starting point to overcoming your OCD is understanding that the significance you place on your intrusive thoughts is the problem. Sadly, understanding is not all that’s needed! What you need is some strong evidence that your own thoughts do not mean you are mad, bad or dangerous so that you can stop reacting to them and hence break the cycle. Unfortunately, simply telling you this will not be enough – you need to find out for yourself and the next section suggests ways that you can gather the personally relevant evidence you need to discover this for yourself. When we say ‘personally relevant evidence’ we mean that you are unlikely to be able to change the obsessions and compulsions unless you have demonstrated to yourself, in your own life and with your own problems, that there is another way of seeing the situation. You will need to find evidence that will convince you that your thoughts and behaviour do not mean what you fear they do, and that they are not significant, and not sinister.

Tip for supporters

Help the person you are supporting think of times when they obtained personally relevant information about something that led them to view a person or situation differently, e.g. when they thought a friend ignored them but later found out the friend had his/her headphones on and so didn’t hear when their name was called.

Figure 11.1 illustrated that behaviour such as avoidance and compulsions can help reinforce the problem. It follows that by reducing the compulsions, this will also have a beneficial effect on reducing the intrusive thoughts you have and may help you test beliefs that help you change your interpretation of their meaning.

As we have seen, a number of factors contribute to keeping you thinking that intrusive thoughts are significant. Some of these relate to thinking style and cognitive biases (see p. 38); some of them relate to the emotional distress that the thoughts cause you; others relate to the role of avoidance and compulsive behaviour such as repeated checking and washing. Treatment involves gathering personally relevant evidence to (i) identify and (ii) change the thinking styles and behaviours that are keeping everything going. It also involves showing you how to cope with emotional distress, even if it is just learning how to accept that it is there. In essence, treatment involves you finding out for yourself that if you change the way that you think and behave nothing bad will happen, and you will be free to live your life as you would like.

As described in Part 1, CBT involves ‘sessions’ that have a structure and are ideally held twice weekly at the beginning for the first month or so, followed by once a week with 12–20 sessions in total. We hope you will have planned ‘sessions’ with yourself or with a supporter so that you can get the most out of this programme. OCD varies, so this structure may sometimes need to be modified to fit the problem and your own situation. If you have a supporter helping you with this book, then it is best to discuss together how to change the structure, if necessary, to suit your personal needs.

In Part 1, we discussed the structure and style of CBT so we won’t repeat it here. We suggest you (and your supporter if you have one) follow this style and structure when using this self-help programme. First, start with setting a flexible agenda at the beginning of each session. It is a good idea to use the assessment measures in the OCD Inventory in the Appendices regularly throughout your self-help programme to see the progress you are making. You will need at least 12 ‘sessions’ as you work through the self-help programme set out in this chapter, and you should start to see improvements by at least session 6. If you can’t see any improvement at all, you may want to consider going to your doctor for some further help.

What is unique about the treatment for OCD is that it aims to change the meaning you place on your intrusive thoughts. The approach is based entirely on gathering useful and significant information about your thoughts and images that is personally relevant, and that leads to different reactions to those thoughts and images. As you’ll read throughout this chapter, the information of most value will be that you get from doing the experiments, rather than simply reading about them. The main goal is to test out new ways of thinking about your intrusive thoughts, leading to changes in how you view and react in the real world. This CBT-based approach can be challenging, but it can also be fun! We encourage you to be creative in your approach – and to know that there is another way of understanding your difficulties that can be dramatically different than how you’ve been experiencing the problem up until now.

As you begin this self-help programme, it’s a good idea to try to work out how severe your OCD is at the moment, as this will help you to understand it and, importantly, to measure your progress as you start to make changes. There are some self-report measures that are freely available for this purpose, which you can obtain from the internet. One of these is the Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Inventory – Revised, which is included in the Appendices (p. 484).

Working out the range of your thoughts and behaviours that are keeping your OCD going is important to help you to start to overcome it. It can be hard to work out exactly what is keeping it going, so it is a good idea to set some time aside and find a quiet place to sit down and do this. As well as measuring the severity of your OCD, scales can help you to work out the different interpretations you are placing on your intrusive thoughts. The Personal Significance Scale in the Appendices (pp. 489–91) can help you do this. The scale can be used at the beginning and end of treatment, and also every week to help focus treatment. It is important to do this because the focus of this treatment is on changing the personal significance you give your intrusive thoughts and you want to be able to monitor your progress.

After you have filled in the Personal Significance Scale, you should be able to answer the important question: How am I interpreting my intrusive thoughts? You can answer this question broadly by considering if you are interpreting the thoughts as meaning you are mad, bad, or dangerous, or you can be more specific in your response.

Having answered this question, ask yourself the following questions (these relate to the boxes in Figure 11.1 on p. 352). First, think back to a time when your OCD was very bad, or to a recent episode.

1. What triggers my OCD? What thoughts/images do I have that worry me?

2. Based on the personal significance scale and my own thinking, how am I interpreting my thoughts and/or images? What significance am I placing on them?

3. After I come up with these interpretations, how do I feel?

4. What am I avoiding doing because of how I’m interpreting my thoughts and/or images?

5. What do I do in response to my interpretations? How does how I react (what I avoid or do in response) to my interpretations help to keep my OCD going? Clue: the answer may be that you do not get a chance to disconfirm your fears, that you never discover your anxiety will not make you crazy, or it may be that you are creating doubt because you are repeatedly checking.

6. What beliefs or biases might I have that are contributing to my OCD? Beliefs broadly fall into six different areas:

Having an inflated sense of responsibility (believing that you need to take on more responsibility than you actually do to prevent harm).

Overestimating threat (believing that threat and/or danger are more common than they actually are).

Being perfectionist (believing that you need to think or do something perfectly in order to properly complete a task).

Being intolerant of uncertainty (believing that unless you are completely certain, bad things can happen) – see page 199.

Giving too much importance to your thoughts (believing that your thoughts are much more important than they actually are).

Desiring full control over your thoughts (believing that your thoughts must be controlled to prevent harm).

When you ask yourself these questions, use the diagram in Figure 11.1 and fill in the boxes to get a picture of what is keeping the problem going. If you find this difficult, re-read Sofia’s story (see pp. 349–50) and compare it to how she’s filled in the diagram. You may find the interpretation/appraisal/belief section to be the most difficult, but remember that the common themes in OCD are beliefs that one might be mad, bad or dangerous.

Figure 11.3: Maintenance of your OCD

Once you’ve filled the boxes in, how do you feel seeing your problems written down in a diagram like this? Some people can feel overwhelmed; others can feel that it provides a first step in beginning to understand where to make changes. Perhaps you feel both of these. Ideally, one thing is clear – change is possible. You have taken the first, and perhaps most important, step to successfully overcoming OCD and arrived at an understanding of what is keeping your problem going.

Effective treatment comes in two stages. You have already started the first stage, which involves understanding what is keeping your problem going. The rest of the first stage involves keeping track of the factors you identified and finding out some facts (‘psychoeducation’). This corresponds to the first two steps of treatment described in Chapter 5, pp. 54–60. The second stage is about gathering personally relevant ‘evidence’ by carrying out behavioural experiments (Steps 3, 4 and 5 described in Chapter 5, pp. 62–81) to help change the personal significance that you are currently placing on your unwanted intrusive thoughts.

You should now be starting to gain an understanding of how the different parts of your problem are connected and keeping it going. Well done! It’s a great start but it can be relatively easy to do this in the comfort of your front room when you’re feeling calm and objective. In reality, in times of stress and worry, the situation may be quite different. It is therefore important to understand what happens in ‘real time’, in real situations, as and when they are actually happening.

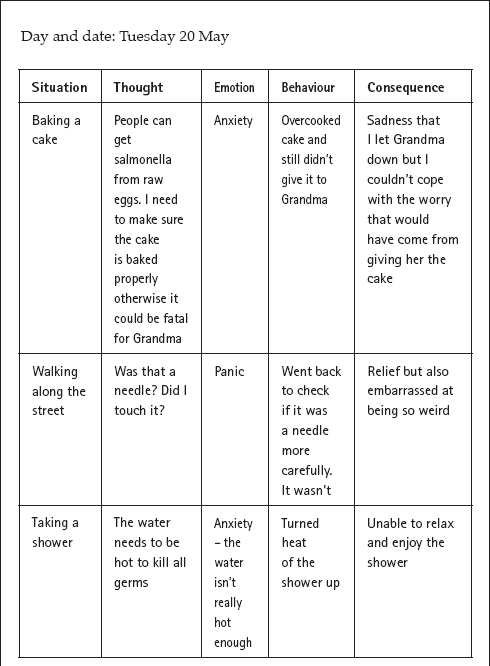

Sofia used Table 11.1 (see p. 352) to understand what was keeping her problem going. She found that she was doing a lot of things because of her fears (that she could be responsible for harming someone vulnerable like her grandmother) and she also realized that she had a range of fears and beliefs related to harming others that kept her OCD going. She also came to understand that stress and tiredness were important factors. For her homework before her next session, Sofia designed a record that kept track of both her thoughts and her behaviours, and also her stress levels in general. Table 11.1 is the completed record. She used one for each day. Importantly, she was not monitoring the personal significance of her beliefs at this stage, in other words how much she believes her thoughts or what she believes her thoughts mean. The aim of the ‘real-time’ record is just to get some information about how OCD manifests itself in your daily life. For that reason, you don’t need to rate your thoughts or the strength of your emotions at this point (although you can if you’d like to). At this point the main purpose of this record sheet is to understand how OCD operates in your everyday life and to make sure that the diagram has captured the most important parts. A blank sheet is given on p. 364 for you to fill in to help you work out what is keeping your problem going.

Table 11.1: Sophia’s thought and behaviour record

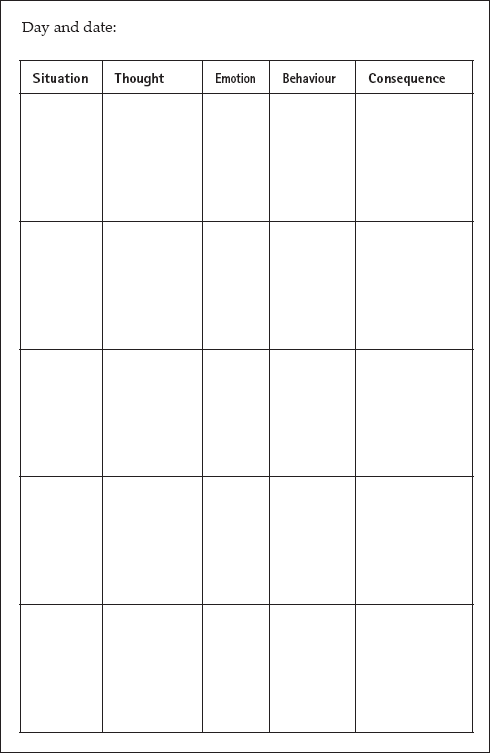

Homework: Copy the blank form into a notebook or photocopy this blank form to complete your own record for two to three days until your next session.

Worksheet 11.1: Blank thought and behaviour record

Once you have completed your record for 2–3 days, go back to the boxes you filled in on p. 364 and see if you now have a better understanding of what is keeping your problem going. Is there anything you left out when you were filling it in initially that you’ve included in your record? Was there any misinformation or misunderstanding about something important? If so, feel free to go back and change your diagram.

Tip for supporters

This is a hard exercise. Do it yourself to help understand and trouble-shoot any problems.

It is important to understand the difference between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal obsessions’. Hard though it can be for people with OCD to believe, we know that almost everyone has unwanted intrusive thoughts.> Even ‘normal’ people who are not at all troubled by OCD can have very strange thoughts coming into their heads! What is more, the content of these thoughts is almost identical to the thoughts that people with OCD have. What is different in people with OCD and without OCD is not the content of the intrusive thought, but the frequency of the thoughts, the distress they cause, and their persistence. This is so important that we’re going to write it here again – it’s not a misprint!

So now you know> that everyone has these unwanted intrusive thoughts. Right? Well, you may have read it, but do you really know it? Does your head know it but your heart not? Do you respond to the information with a ‘yes, but . . .’? What you will need in order to believe it is information that is personally relevant and meaningful to you. Everyone knows that smoking is bad for you but for some people it is only when they get ill that they really believe it. Similarly we all know we should exercise, but it is only when one reaps the personal benefits of doing exercise that it becomes a real change in lifestyle. We can tell you that everyone has unwanted intrusive thoughts, but there is nothing like finding it out for yourself.

How can you find out for yourself? If you have a supporter, you can ask him/her about the more unusual thoughts and images they may have experienced about harming people, bad things happening, losing control, swearing in a holy place, being immoral or whatever is most relevant to you.> It may be that you prefer to do a survey. Surveys are particularly important in the treatment of OCD. You could conduct a survey amongst your friends in which you list a range of intrusive thoughts and ask them if they have ever experienced them. If you prefer, you could say that you are doing research as part of a project. Alternatively, you might want to use a social networking website to help do the survey and to emphasize the survey’s serious purpose.

Sofia’s survey

Sofia was surprised to find out that everyone had thoughts that they might accidentally poison someone and she realized that she wasn’t mad for thinking such thoughts and that she wasn’t a bad person. However, she wanted to do her own survey to see if people she knew and respected, and thought were good, kind, responsible people also had such thoughts. She decided to ask her sister to help her in the survey. Her sister was a teacher and Sofia said that she had to do this survey as part of a work project. She asked her sister to help by asking some of her colleagues about their thoughts and images. Her sister agreed, and four colleagues and her sister returned the form. One person said that they never had any of the thoughts, but the other four all said that they had thoughts about accidentally harming people; for the teachers it was more commonly children than elderly people they were afraid of harming. Sofia ended her survey with an open-ended question: what do you do when you have the thoughts? Of the four colleagues who had them, three said that they busied themselves by doing something else, and the fourth said ‘nothing; they go away’. This information was vitally important in helping Sofia to understand that it was her reaction> to the intrusive thoughts – her interpretation of them as being personally significant and the way that she behaved as a result – which explained why she was having so many of them, and why they persisted. This was a real change from her previous assumption that having the thoughts meant she was a bad person.

You may have found that your OCD has changed over time, and that you had thoughts and symptoms in the past which don’t seem to trouble you so much now. Understanding your past obsessions – what provoked them and what led to their decline – can be of considerable importance. Can you think of a past obsession that has gone away? Can you see the connection between the personal importance you attached to the intrusive thought you had and the fate of the thoughts? Asking yourself the questions below may help. Sofia’s answers are shown below to illustrate how this exercise helped her:

Table 11.2: Analysing the fate of past obsessions

1. Have any of your obsessions become less frequent/intense or even completely gone? Which ones?

Sofia: Yes, when I was a little girl I used to worry that if I didn’t do a bedtime ritual then my parents would die.

When?

Sofia: I had it for years, but I grew out of it I guess when I was about 12 or 13.

2. Explain why they decreased.

Sofia: Well, I wanted to go for sleepovers with friends and I couldn’t do the rituals there and I got back and my parents were OK so I knew I didn’t really have to do them. They faded over time.

3. What do you conclude from their disappearance?

That they will gradually disappear and I don’t need to do the rituals I am doing.

4. Why did they weaken/go and others persist?

I guess I found out I didn’t need to do those rituals to keep my parents safe.

5. Were any of your past obsessions followed by unacceptable, catastrophic behaviour?

Sofia: No, nothing bad ever happened to my parents. They are still around nagging me!

6. What can you conclude from this?

Sofia: That I guess if I change how I respond to my obsessions, the problem may go away.

Tip for supporters

Help conduct the survey by asking your friends/family to take part as well as the friends and family of the person you are supporting. Help the person you are supporting to discuss what happened to their past obsessions and, at the end, help them to see what the discussion tells them about what their problem may be – are they a bad person or are they placing too much significance on what are normal intrusive thoughts and images?

In common with other anxiety disorders, you may well fear that you will lose control and go crazy when you have your intrusive thoughts if you do not engage in your compulsions; you may also be afraid that you will carry out some horrible act. As a result, you probably generally try to have complete control over your thoughts and behaviour every day, to guard against any slip-up. If this sounds familiar, it is important to ask yourself if you have ever carried out any of the horrible acts that you have imagined happening? Undoubtedly the answer will be ‘no’. In all our years of treating patients with OCD, we have never known anyone act on their obsessions. If you have ‘evidence’ from newspaper articles of it happening, you should know that it is likely that the person did not have OCD. People with OCD are in fact the least likely of anyone to act on their thoughts.

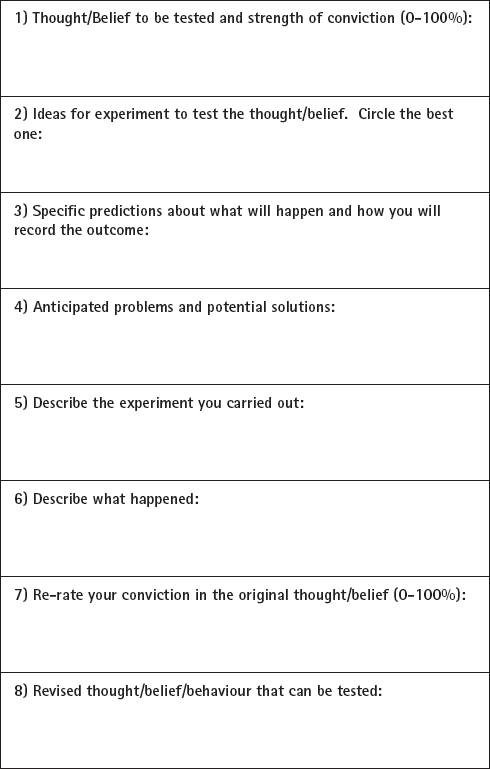

You have this information but now you need it so that it is personally relevant to you. That is where behavioural experiments> come in. If you are worried that anxiety will make you go mad and lose control, the best thing to do is to do an experiment whereby you try to go mad and lose control! What would going mad look like? Screaming? Shouting? Collapsing? Firstly, predict how likely it is that you would go mad and lose control if your anxiety reached 90 per cent. Now let’s try it. Try to make yourself very anxious (not pleasant, but essential). This part should be straightforward: you could think of something happening to your loved ones or you could recall a past experience when you became very anxious. Now, when your anxiety is REALLY high (90%), what happens? Do you scream? Do you shout? Collapse? No? What can you conclude from this? Now re-rate how likely you now think you are to go mad if your anxiety reaches this point again. You can use the behavioural experiment sheet, Worksheet 5.2 on page 65 and in the appendices. A blank sheet is given below.

Worksheet 11.2: Behavioural experiment sheet

You can repeat this experiment as homework before your next session so that you gather a large amount of evidence that the likelihood of your going mad when you’re feeling very anxious reflects the reality – zero.

The other chapters on specific anxieties also address the fear of control, so it may be worth also reading the relevant sections.

If we were betting folk, we would bet that although you read the paragraph above you have very little intention of actually carrying the experiment out. Sound about right? If so, we’re not surprised. We’re asking you to take a risk – the very great risk of going mad and losing control. We know this is a risk for you but we also know that it is one worth taking. With all behavioural experiments you need courage to try things a different way so that you can gather the information you need to make real changes in your life. We would like to encourage you to have such courage – we know what dramatic changes are possible if you can do some of the experiments. We also know that if you do not take some of these ‘chances’ and don’t take risks, the unfortunate reality is that your OCD will persist. To encourage you to take the risk and to carry out the experiment, remember that courage is the overcoming> of fear and not the absence of fear. Also keep in the front of your mind that nobody has ever gone mad or crazy or lost control from feeling anxious. We hope you can try all of the experiments we describe in this self-help programme and make progress in overcoming your OCD; it’s difficult but worth it.

A young mother had terrible fears that she would harm her young daughter. She could not let herself bath her in case she pushed her under the water, and she could not go into her bedroom at night in case she smothered her with a pillow. She could not be alone in the house with her daughter, and her husband or mother had to be with her all the time. She was asked to carry out an experiment that involved taking a risk – the risk that she could bath her baby on her own (with her therapist in the room next door). With a great deal of anxiety, and a great deal of persuading, she carried out the experiment and realized that she could be in the bathroom with her daughter, and that nothing bad happened.> Afterwards it was much easier for her to believe that she would NOT act on her thoughts, and she started to be able to do much more with her daughter – but she needed the experience of it to be sure. This was very, very difficult for her to do – but she managed and we hope that you can, too.

Tips for supporters

Help make sure the risks are manageable and neither too demanding for the person to complete nor so easy that they don’t provide useful information. You can take the risk as well and do the experiments together.

Your thoughts are so unacceptable to you that you are probably trying to suppress them but it is likely that your attempts to control your thoughts are backfiring. Here’s another (much easier) experiment: try not to think about a white bear. What comes into your mind? A white bear? What does this show you? It is a universal finding that when you try not to think about something, it pops into your mind. For some people, it might be that the very attempt to suppress the thought is causing the thoughts to ‘rebound’ and you have more of them. What is certainly true for almost everyone is that we do not have perfect control over our thoughts – and you are not an exception to the rule. Your attempts to suppress your thoughts are either (i) going to make you feel bad that you can’t control them and you are likely to have more of these thoughts when your mood is low or (ii) may actually be causing you to have more of them. Don’t believe us? Put it to the test. Think of a troubling thought that you usually try to suppress and try not> suppressing it for one hour. What happens? Do you have it more frequently or less frequently than when you try to suppress it? What happens to your mood? You should find that you have the thought less frequently and that your mood improves.

Sofia spent a very great deal of time scanning the ground for used needles – that is, she was paying a great deal of attention to the threat that there might be needles there. She explained this by saying that she has to be on guard all the time, because if she was not then she could accidentally step on a needle.

You may find that you are constantly scanning the world around you in a similar way to Sofia. It is very common for people with OCD to spend a lot of time scanning their thoughts. So the next experiment is to try not to do this and see what happens.

Experiment

Step One: Make a prediction – what will happen if you refrain from scanning your thoughts or the environment?

Step Two: Stop scanning for danger the next time you are out for a walk. If it would help, you can tell yourself that you are ‘off-duty’ for this period and you can try to notice something else instead (e.g. billboard advertisements).

Step Three: What happens? Did your prediction come true?

You can also do another experiment in which you make a deliberate effort to pay a lot of attention to threat and notice all your thoughts and all possible sources of danger in the environment.

Sofia found that when she was paying a large amount of attention to potential threats she was more preoccupied with needles and HIV, and felt more anxious and more contaminated than when she was ‘off-duty’. Importantly, she also found out that she did not step on any used needles when she was not scanning for them, and that she worried less and felt happier. She came to the conclusion that she need not pay so much attention to where she was walking, and that paying all this attention might give an explanation for why she had been having so many intrusive thoughts and images.

In Part 1, we described a range of thinking errors and biases such as catastrophizing. There are lots of cognitive biases in OCD that can be tested using behavioural experiments:

• Do you increase your estimates of the chance of harm when you are anxious (although the actual chance of harm does not change, of course)?

• Do you feel you are being more responsible when you are anxious?

• Do you feel more responsible as a result of checking, although the goal of checking is to reduce responsibility for harm?

• Do you feel that when you are responsible, the chance of harm is higher than for others?

If you said ‘yes’ to any of the questions above, then you have biases in your thinking. Spend some time stepping back and testing such biases by carrying out experiments in which you increase or decrease your anxiety and then see the effects on how you estimate the chance of harm. It is also useful to do the same kind of experiment in which you increase/ decrease responsibility by handing over responsibility to someone else and seeing the effect. Try doing this as homework before your next session and see what conclusions you draw.

Identifying your thinking biases is important and stepping back and noticing when they are happening can help change them. In OCD, one common thinking bias is called ‘thought–action fusion’. A key aspect of this is the belief that thinking about harm coming to someone else makes it more likely to happen. People with this kind of belief unsurprisingly feel responsible for potential harm being caused to others. If you find yourself often thinking this way, then the following experiment may be helpful, although you might find it difficult. If you have a supporter, encourage them to do it as well!

Test your beliefs about thought–action fusion

Write down the following sentence in your notebook:

I hope ______ (someone you like) has a minor car accident in the next twenty-four hours.

How do you feel? Guilty? Anxious? People with and without OCD tend to feel highly anxious when doing this experiment. Many people feel it is immoral to wish harm on others even if it is part of a self-help programme. They may also feel concerned that someone will find their piece of paper and think badly of them when they read what they’ve written. Do you fear ‘bad karma’? Are you afraid about the accident happening and how you would feel if it really does happen?

All of these concerns are understandable, of course, but if you truly believe that your thoughts can cause harm to others, there is only one way to change this belief – try it and see what happens.

Tip for supporters

Be willing to offer your name for the person to write the sentence about.

We’ll assume you have done the above exercise and nothing bad has happened to the person you liked. This isn’t just wishful thinking; this is based on years of doing such experiments. If you have managed to do this and you are reading this next part twenty-four hours later then congratulations! Did writing the sentence down make it come true? What conclusion can you draw from this experiment? Can you now re-write the sentence replacing ‘minor’ with ‘serious’? Can you now change it from someone you ‘like’ to someone you ‘love’. What happens?

Of course, there is always a chance that something bad may happen to someone we care about, but if it does it would be a coincidence. Thinking through the way that bad thoughts could cause harm (there is no logical mechanism) can encourage you to see that the main effect of this experiment will be on your feelings and fear of harm rather than actually causing harm. If you have a supporter, discussing the unfairness of your way of thinking (i.e. that you focus on the negative) can be helpful. You are unlikely to think the power of your thoughts can cause you to win the lottery – why does it work only for bad events? If you do not have a supporter, then do your best to think these issues through alone – writing them down in your notebook may help you to understand your thinking better and help you to realize that thoughts are just thoughts.

People with OCD often think their thoughts mean that they are responsible for harm or its prevention. Sofia felt responsible for potentially harming her grandmother. Responsibility is an important feature in OCD, particularly in checking behaviour. One way in which it can be tackled is (i) to assess how responsible you would be if a feared event occurred, (ii) to brainstorm all the other people who might also be responsible and allocate percentage responsibility to them in a pie-chart and (iii) to reassess your responsibility level.

For example, Sofia said that she would feel 100 per cent responsible if she baked a cake that gave her grandmother food poisoning. After some consideration, she thought that other people might have some responsibility too – the farmers whose eggs were sent to the manufacturers were considered to have 20 per cent responsibility, the supermarkets that stocked the eggs were given 30 per cent responsibility and her grandmother was given 10 per cent responsibility for not noticing that the cake was not baked all the way through. This left Sofia with 40 per cent responsibility rather than her original 100 per cent.

Tip for supporters

Help the person see who else might be responsible for harm.

There is a great deal of research showing that the more you check, the less sure you become. This sounds bizarre because people normally check because they want to be sure about something. A number of separate experiments conducted across the world show that when you check a stove repeatedly, you are likely to have dramatically less confidence in your memory (as well as a less detailed, less vivid memory) than if you check just once or twice. This has even been demonstrated in studies of mental checking, where participants were asked to check situations over and over again in their minds. A separate large amount of research shows that people with OCD have excellent memories, even though you may doubt this applies to you. Like the other experiments discussed here, reading about it probably isn’t nearly enough. If you have recurring doubts about your ability to trust your memory in your life, try the experiment below.

Choose a situation in which you find yourself repeating or re-checking something. On one day, check it a lot. Do it for a set period of time (e.g. 20–30 minutes), or until you start to feel frustrated with the amount of checking you’re doing. Twenty minutes or so later, jot down how clear your memory is for the checking you completed earlier, perhaps on a scale of 0 to 100. Another day, check the same thing just once. Later on, write down information about the clarity of your memory as you did on the day when you checked a lot. Did you notice any difference between the two occasions? Sofia carried out this experiment focusing on her repeated checking for syringes while walking in the street and found that when she checked a lot, she began to question whether or not she had actually seen any on the street. She felt that she hadn’t seen them, but she also didn’t really trust this feeling and couldn’t say for sure that she hadn’t. However, when Sofia checked just once for syringes during her walk, she was markedly more confident in her memory and knew that there had been no needles on the street. Sofia came to the realization that checking actually causes doubt.

Tip for supporters

You can do this experiment easily together by checking just once if you have switched your phone on to ‘silent’ mode and by checking it multiple times.

Behavioural experiments can be used to establish the helpful or unhelpful effects of avoidance. Typically, avoidance helps us in the short term by providing relief from our anxiety but it can also play an important role in keeping the problem going as we don’t discover that what we fear does not in fact occur. Sofia conducted an experiment in which she gave a cake to her grandmother that had been cooked according to the instructions on the packet rather than burned to ensure all traces of salmonella had been eradicated. She predicted she would worry about it for at least forty-eight hours after her grandmother had eaten the cake. She shared some cake with her grandmother so that she would see if she also got symptoms of salmonella. She discovered three important things from this experiment. First, her grandmother did not contract salmonella (nor did she). Secondly, she worried about it considerably less than she predicted she would and was able to throw herself into a project at work rather than finding that she couldn’t concentrate because she was so preoccupied by her grandmother. Thirdly, she could make a really great cake! Can you think of any experiments you could do to help you work out the role of avoidance in your OCD and to see how reducing your avoidance could change some of your beliefs (as well as giving you more freedom)?

Tip for supporters

Ensure that any experiments carried out are neither too demanding nor too easy.

People with OCD take an average of seven years to seek treatment. If you have never sought treatment, part of the reason may be a fear of having to reveal the content of your thoughts to someone. Many people with OCD are ashamed of their thoughts and worry what others would think of them if they knew the content of their thoughts. Knowing that everyone has these thoughts is particularly important information and it is also important to realize that keeping your thoughts a secret prevents you from ever learning that your fears are not likely to be realistic. Keeping your thoughts a secret will also stop you from finding out that other people do not place the same significance on your thoughts as you do. Keeping these thoughts to yourself is in fact likely to contribute to your believing that your thoughts (‘obsessions’) reveal your very worst qualities. An important step in overcoming OCD can involve sharing your thoughts with a trusted friend, relative or your therapist in a planned way, or anyone who is sympathetic to the problem. It takes courage and we know it is not easy but it is worthwhile. When Sofia finally told her partner the full details of her obsessions, he was far more supportive than she predicted and said he had experienced occasional thoughts of that nature also. He asked what he could do to support her when she was trying to overcome her anxiety. He also said she had been so distant and preoccupied at times that he had worried she might be having an affair. Sofia was shocked by this and they agreed to be more open with each other in future.

Tip for supporters

If the person you are supporting does not want to tell you their thoughts, that’s OK. Be encouraging and patient.

It is likely that you have some evidence that supports your original interpretation of your intrusive thoughts and is the reason why you decided they were significant in the first place. What are they? Can you write them down in your notebook? Many people feel that their thoughts and images are so strong and persistent that they think they might really want them and that they might go crazy. Understanding how your responses to your intrusive thoughts might actually be contributing to their persistence might help you re-think the view that you must really want them. After you have written down the list of evidence that led you to interpret your intrusive thoughts in this way, can you step back and re-examine it? Is the evidence really that strong? Is the evidence based on facts or feelings? Can you think of it a different way? For example, Peter had OCD centred around the fear that he would go mad and commit a terrorist atrocity. He provided evidence that people who committed major acts of terrorism must have been preoccupied with such thoughts beforehand and that they were clearly mad. He discussed the difference between the terrorists’ thoughts and his own thoughts with his therapist and found it very helpful. It became clear to him that the terrorists’ thoughts were welcome and consistent with their religious values, whereas his own thoughts were unwanted and unacceptable to him.

What information do you need to help you re-think what a intrusive thought may mean? How can you get it? What might get in your way? How can you overcome those obstacles? Set yourself the task of gathering any information required to help you re-think the personal significance you place on your intrusive thoughts.

Tip for supporters

Help the person you are supporting see the difference between their old way of thinking and their new way of thinking (i.e. that their thoughts are not personally significant).

Regular eating and sleeping is vital to good mental health in general and that includes those with OCD. Thinking rationally and helping your heart and head act consistently with each other depends on a reasonable amount of sleep and a nutritious diet. Low mood worsens OCD and having OCD puts you in a bad mood so it is important that you have some activities in your daily life which give you pleasure and that you make sure you eat and sleep properly.

By now you will have gathered some reasonable evidence about the nature of your OCD through the education, surveys, experiments and re-thinking the amount of significance you give your intrusive thoughts. You should understand that it was your interpretation of your thoughts and your response to them that made them personally significant and meant that your OCD persisted. Sometimes though you may reach a stage where you’re not quite sure what to think. On the one hand, there is increasing evidence that the significance you’ve given your thoughts is the problem and that they may not be so meaningful while, on the other hand, it’s likely you have been thinking this way for many years and changing can be difficult. In such circumstances, we suggest you act as if you believe your thoughts are not personally significant. You can do this as an experiment to test a specific belief, but you can also do it simply to have the experience of acting and behaving according to a new belief system. You may find that acting in such a way provides further evidence that changing one’s way of thinking and behaviour really helps in your recovery from OCD.

We hope you have made good progress using this chapter. You can measure the progress you have made by using the scales that you used at the start so you can see the difference. The scales are in the appendices. Alternatively, you can try more detailed self-help books listed in the recommended reading. It is important to maintain the gains you’ve made using the advice on preventing relapse covered in Chapter 14 of this book (p. 416).

If you feel you have not benefited from working through this chapter, then contact your GP and try to get further support, or refer yourself to a local service (if you are in the UK you can find the details of such services on the NHS Choices website – www.nhs.uk).

In Sofia’s case, she was planning to start a family within the next few years so her relapse prevention plan included a section on how she would deal with fears of contamination when she was pregnant, giving birth and having a newborn baby at home. Her plan was successful and she managed times of anxiety well by re-reading her notes from these sessions and other relevant chapters of this book.