8 |

Generalized anxiety disorder and worry |

Richard’s story

Richard could not relax. He felt tense and anxious the whole time, so much so that he started to worry about his health. He enjoyed his job, but he found it stressful and from time to time felt that he just couldn’t cope with it. He headed up a small but talented team. Despite this he found it hard to delegate and so did too much of the work himself, so adding to his stress. It was not that he doubted the quality of his colleagues’ work but he knew that even good people might make mistakes. He checked his own work repeatedly and never sent emails without reading them several times first. He always phoned his girlfriend to check that she was on her way home, and he worried if she was late. Often he imagined horror stories as his worries took hold, such as terrible car accidents, train wrecks or abductions – checking the internet for any news of these imagined events while at the same time imagining how he would manage work while caring for his girlfriend as she recovered from serious injuries. His girlfriend found his constant checking very difficult, sometimes ignoring his calls. His family and friends loved him but they also got annoyed because he was overprotective and often needed reassuring that they were OK. He started to suffer with tension headaches and began to drink a little too much. His worry was so much part of his life that he hardly noticed it, but he did notice feeling tense, exhausted and deflated.

We all experience bouts of severe worry from time to time. Some people, like Richard, however, experience excessive and distressing levels of persistent worry. In this case it is likely that they are suffering from a disorder called ‘generalized anxiety disorder’ or GAD. The most important feature of GAD is that people experience quite severe anxiety and worry about a wide range of things over long periods of time. Other symptoms of GAD include:

• Finding it difficult to control the worry.

• Restlessness or a feeling of being keyed up.

• Getting easily tired.

• Difficulty concentrating, or feeling that your mind has gone blank.

• Irritability.

• Tension in the muscles.

• Sleep disturbance, so that we have difficulty falling or staying asleep, or wake up feeling unrefreshed by our sleep.

• Finding it difficult to function normally at home, at work, or elsewhere, because of the extent of the worry.

Because of the importance of worry to GAD, we are going to spend the rest of this chapter talking about worry, and how you can understand and learn to overcome it.

Some people may feel that there is nothing that can be done about worry, or that it’s just ‘them’ – part of their personality that can’t be changed. But even though you may always have had a tendency to worry – maybe your parents did, too – you can still learn to understand it and get on top of it in a different way. Excessive worry is not a part of your personality, and it’s not something that you should accept as inevitable. The other thing to note is that it is normal to feel anxious and worried at times, so we are not saying that you will never feel like this, but you can definitely learn to keep it in proportion, and to deal with it differently.

The ideas found in this chapter are the product of several different groups of researchers from around the world who have studied worry, some of them for nearly thirty years. Their work has contributed to the development of a better psychological understanding of worry and to a specific and effective cognitive behavioural therapy. Currently this treatment is one of the most effective and widely tested treatments for worry, and we describe its techniques in this chapter.

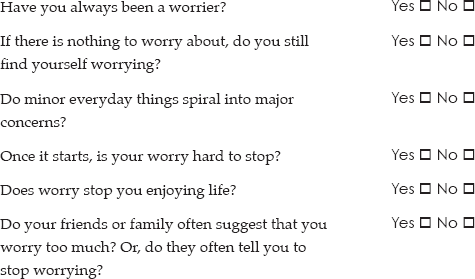

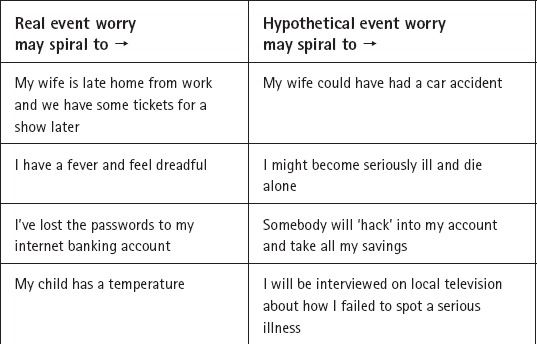

To help you to see if this chapter is for you here are some simple questions:

If you answer ‘yes’ to at least two of these questions, and if the worry is making it difficult for you to function properly at work, at home or in social situations, then it is likely that this chapter is for you.

In the explanations below we have added questions to help you to think about your experiences, and how the explanations apply to you.

You might find it helpful to make notes as you go along, so that you can collect your thoughts about the different aspects.

There are three important aspects to understanding worry, which we will describe in turn:

• Understanding uncertainty.

• Distinguishing between real and hypothetical worries.

• The importance of ideas about worry.

Uncertainty is a state almost all of us find unbearable at some point. Imagine a family waiting in an A&E department for news of a loved one involved in an accident, and not knowing whether they will survive or not; sometimes the uncertainty, or not knowing, is the hardest thing to bear. But this is a major and terrible situation. For most of us, even without realizing it, uncertainty is a constant feature of our lives, and we tolerate it without even noticing. We cannot know for certain whether there will be an accident on the road or the train; we cannot know for certain that our children aren’t getting into trouble when they are out of our sight, but usually we are able to go about our business without much more than a passing thought about these possibilities. We have learned to tolerate this uncertainty. For people who worry excessively, though, even small daily events can produce a level of anxiety and worry on a par with the A&E situation.

So worry and uncertainty are intimately linked. For people who are worried, it is the feeling that you get when you are faced with uncertainty and start to think about what might happen. You worry because you don’t know what is going to happen, and you start to imagine or fear the worst. You start to ask yourself ‘what if?’ questions. Typical examples include: ‘What if my partner has an accident on the way home?’; ‘What if my report is useless and my boss decides I should get the sack?’ This ‘what if?’ question then triggers a whirlwind of worry. For instance, someone who worries might notice a headache, and start to think, ‘What if I get sick and I can’t look after my kids?’ Then the questions get worse: ‘What if my kids get put into care?’, ‘What if they start to take drugs and become criminals?’ These worries might then lead to worrying about something completely different. So the person may move on to worry about their finances, and then to worry about how they will be able to pay the legal fees for their ‘criminal’ children, even though their children are still under five years old and have not done anything wrong yet!

People who worry tend to get caught up with these overwhelming thoughts about bad things that might happen. Like the example above, the worries that come into people’s minds are usually highly unlikely but seem very real at the time. Consequently, worriers tend to be concerned by the unpleasant events they imagine in the future, rather than what is actually happening in the present.

‘What if?’ questions can be triggered by events that anyone would find scary, such as being referred to a specialist doctor, or hearing about redundancies at work, but for people who worry excessively they are also triggered by everyday situations, such as a minor disagreement or having a routine appointment with the doctor, visiting friends or shopping.

Do you have lots of ‘what if?’ type questions that go through your mind? How do you feel about or react to uncertain situations?

Figure 8.1: Worry and uncertainty

Worriers tend to run on safe and familiar tracks to try to avoid uncertainty, but this can also place real limits on them by taking away new opportunities, new beginnings, new relationships, or by keeping people stuck within unhelpful situations, roles or relationships. Another possible consequence of this limited lifestyle is low mood and depression, especially when people are stuck in familiar but unrewarding situations, roles or relationships.

There are two types of worry. There are some problems that we worry about which really exist; these problems could be called ‘real event worry’. For example, if I worry about the size of my credit card bill, then this problem exists and my worry is based on a real and present problem. So rather than just worrying, it would make sense to try to do something about my spending – to put it another way, to engage in problem-solving. We will come back to problem-solving later in this chapter.

There are also worries about problems that haven’t happened yet, but which might. These kinds of worries are known as ‘hypothetical event worry’. For example, while many of us would dream about winning the lottery, worriers would also worry about winning it. They might worry about what to buy, how to deal with all the requests for money, even what to do when all the money had gone! In this hypothetical event worry, they may have not even bought a ticket yet, let alone won the life-changing jackpot.

Because it is about something that only exists in our imagination, we cannot ‘problem solve’ this kind of worry. Despite the worry being based on an imagined event, it still produces severe anxiety and fears. We need to learn that the things we imagine in our hypothetical event worry are only thoughts and nothing else, and approach them in a different way.

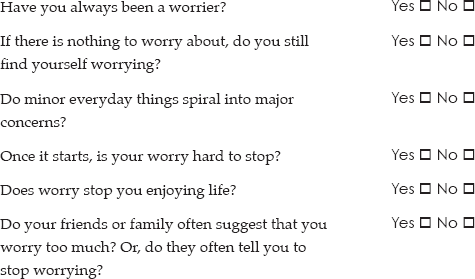

Real event worry can sometimes spiral and evolve into hypothetical event worry. So from a real concern that is here and now, the worrier may end up worrying about something completely different but set in the future. In Richard’s example at the beginning of the chapter, notice how if his girlfriend was late (a real event) this led him to worrying about her having an accident (hypothetical event) and how he would cope with her serious injuries while managing work (hypothetical event).

Sometimes it can be hard to tell the difference between real and hypothetical worries, so Table 8.1 gives some more examples.

Table 8.1 More examples of real event vs. hypothetical event worries

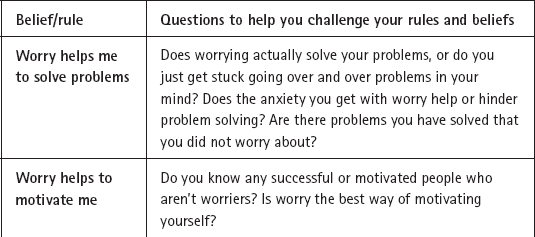

Without being consciously aware of it, we have ideas about worry at the back of our minds that can help to keep worry going. There are two broad groups of ideas or beliefs that both tend to make us worry more. The first group could be called ‘positive beliefs’ about worry. Examples of positive beliefs would be ‘worrying shows that I care’ or ‘worrying motivates me’. These ideas ‘set us up to worry’. The second kind of thought could be called ‘negative beliefs’ about worry. These ideas appear once we have started to worry and add an intense element of anxiety to the whirlwind of worry. A typical thought might be ‘worrying so much means I am losing my mind’. When these thoughts appear, they feel very real and are so believable that they bring with them severe levels of anxiety or panic, which stoke up worry all the more. We could describe these beliefs as ‘turbo charging’ anxiety.

Exercise: Look at the list below, and see if you recognize any of these ideas.

Positive beliefs about worry

1. Worry helps me to find solutions to problems: This belief is based on the idea that worry is a useful strategy that helps to find solutions to problems. The belief suggests that worry enables us to look ahead and prepare for what might go wrong, or that worrying can help us to decide what we should do if our fears happen.

2. Worry motivates: This is one of the most common beliefs in people with excessive worry. In a recent tutorial a student said, ‘My worry motivates me to work; if I didn’t worry then I wouldn’t work.’ This belief is only helpful if it does just enough to get us working; it then needs to ‘leave us alone’ to let us get on with the job in hand.

3. Worry protects: This idea means that the person who worries believes that if they worry before a difficult event, then they will be prepared for the worst, so that if something bad does happen they will be able to cope with it better.

4. Worry prevents: In this kind of belief, there is a strange kind of logic. The idea is that if you don’t worry you are somehow tempting the fates, who will get back at you by making bad things happen.

5. Worry shows I care: This belief is very common. Here the beliefs centre around the idea that worrying means that the worrier is a thoughtful, caring or loving person; and, by implication, if they didn’t worry this could mean that they were inconsiderate, careless or unfeeling.

The problem with these positive beliefs is that, although on the face of it they look sensible, in fact they make things worse. We will show you how to tackle these beliefs in the Treatment section.

Spotting your positive worry beliefs

Instructions: Think about something you worry about and try to answer the following questions. In the blank spaces below insert a description of what your worry is about. It might be the name of a loved one, a child, a family member, a colleague or a friend. It could be an event like an exam or a meeting. It could be a general concern like work, or money or health.

Supposing I didn’t worry about _______________, then what would that say about me?

Supposing I worried less about ________, then what would that say about me?

How does it help to worry about ___________?

Supposing I stopped worrying completely about _________, would I be bothered by this? If so why?

If I worried less about ____________, would anything happen?

Does worrying about ___________ help in any way? If so how?

I should worry about ____________ because__________________________________

Does it help you to understand why you worry in certain situations? Does it help you to understand what makes you more inclined to worry? Have you discovered any of your worry beliefs?

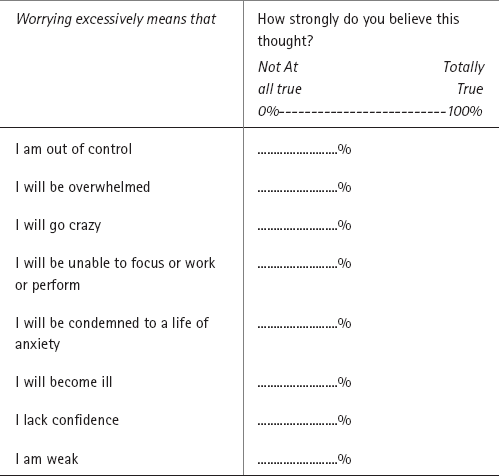

People tend to believe that once they have started worrying, their excessive worry will lead to a number of unpleasant and distressing outcomes, like losing their mind or losing control. These thoughts ‘turbo charge’ worry – they could be called ‘worry about worry’. We have listed some common ones in Exercise 8.1.

Exercise 8.1: Worry about worry

Consider each belief in the table below and ask yourself which of these beliefs applies to you?

We have talked about uncertainty, types of worry, and beliefs about worry. Although these three ideas are key to understanding worry, there are also a number of other aspects to it that are important.

When people are caught in the spiral of worry, they often feel tense, nervous or panicky, and experience a variety of other signs of anxiety, such as the symptoms described at the beginning of this chapter, or in the first part of this book. It might help to make a note of how you are feeling, so that you can use these symptoms to help catch yourself starting to worry.

What kinds of feelings and physical sensations do you experience when you worry?

If you are a worrier, you may also have an overriding sense that you cannot cope with the everyday problems or situations you face. You may feel overwhelmed by them, or think that you lack the confidence to solve life’s problems. This can result in avoiding or putting off dealing with problems, leaving them unsolved, which in turn triggers more worry.

Do you worry about your ability to cope with life’s problems?

Trying to distract your mind away from your worries might work for a short time but it can be difficult, particularly when the unpleasant sensations mentioned above are there to remind you of them. Also, trying not to think about worries means that you think of them all the more (see the white bear experiment on p. 373 in the OCD chapter). Despite using distraction and trying to avoid thinking about your worries, they have a tendency to continually return to the front of your mind.

Are your worries so upsetting that you try to avoid thinking about them? How do you distract your mind from your worries? Do you try hard to keep busy or overwork to keep your mind off your worries?

Our thoughts race when we worry and the speed of thought can sometimes give the impression that our thoughts are chaotic and lack any pattern or order. This sense of chaos further adds to the idea that our thoughts are out of control, causing us to worry all the more.

Do you have difficulty controlling your worries? When you start worrying about something do you have difficulty stopping? When your worry is racing do you ever feel like you are losing control of your mind?

Worry is a private experience. Even our close friends may be unaware of our worry – we try to hide how bad it gets in case people think we are crazy, or pathetic. Often we worry in the early hours of the morning or at other times when we are ‘alone with our thoughts’. These hidden and private worries can have a profound impact on our actions and on how we relate to others. For example, our worry may motivate us to be overprotective, or we may continually check on our loved ones, which may be experienced by others as intrusive or nagging, as was the case with Richard (see p. 197). Sometimes our worry drives us to seek reassurance from those around us, ‘checking out’ our fears with others in subtle or more obvious ways. If we do share our worries, we may be dismissed or told, ‘Don’t worry about it’, but we still feel someone has to do the worrying.

How does your worry influence how you relate to others? How does your worry influence how you act? How does your worry interfere with your life?

Worriers also tend to focus on what may happen and so ‘live’ in the future. This prevents them from enjoying life in the here and now. For example, at a football match, rather than enjoying the game, the worrier may think about whether they will be able to get their bus home and what may then happen if they can’t. Living in this way has a profound effect on an individual’s capacity to simply live and enjoy life. If this goes on for a long time it can lead to depression.

Do you find it hard to enjoy the moment? Do you spend a lot of time in an imagined and anxiety-provoking future?

In the middle of all these worries, the overriding feeling is anxiety, but even when the storm eases off you might not feel much better. You might find that you feel demoralized and exhausted. You might ‘beat yourself up’ mentally after the whirlwind has passed, or you might feel useless and low if your worry has got in the way of solving a problem or stopped you from doing something important.

How do you feel once a bout of worry has passed?

We can try to show how some of these things fit together by using the diagram below:

The situation in Figure 8.2 now finds Richard getting ready for work. The uncertainty found within a news bulletin about the weather is turned into a what if? type question by Richard. This then triggers a whirlwind of worry that produces anxiety that manifests in strong negative feelings, distressing bodily sensations and unhelpful actions. Once the worry has passed Richard feels exhausted and demoralized.

Figure 8.2: Richard’s worry spiral

To worry is to be human – we all worry, some more than others. Research in many different countries has suggested that somewhere between 2 and 4 per cent of a population have enough symptoms to get a diagnosis of GAD in one year. Playing it safe, that’s roughly about one person in every twenty-five. Next time you are sitting in a café watching the world go by (or sitting worrying . . .), think about this: one in every twenty-five.

Worry can occur at any time, and this is also true for the onset of GAD. We tend to be more likely to start worrying at times of change and stress. If our lives have changed in a major way, or if we have more responsibilities, we will become more susceptible to worry.

Often people start to have problems with worry relatively early on – between the ages of eleven and the early twenties. These early phases of our lives are important as we lay the foundations for the years to come and try to establish a sense of who we are. It is a time of heightened uncertainty coupled with changes in responsibilities and independence. At this time, worry can appear owing to many subtle influences. It doesn’t need a major life event or trauma to trigger it.

The other time that worry tends to appear is much later in the lifespan, during middle age. This is the time of life that is often typified by stability in a number of areas of our lives. We may be more certain of who we are, and where we fit in the world. We may have an established career and home life. When worry appears later on, it is usually linked to some significant change, such as children growing up, a breakdown of a relationship, bereavement, an accident or illness, or a major shift in the way we live our lives, such as retirement. This might challenge the status quo and generate doubt and uncertainty.

It is important to remember that excessive worry can appear at any point in a person’s life, but is often linked to heightened levels of uncertainty.

When did your worry become problematic? Was life more uncertain than usual at this point?

A precise cause of GAD is not known and there may be several factors involved in its development. In our clinical experience, there are many pathways to worry. Some people might be more likely to experience anxiety because of their genetic or physiological make-up, or because they have had a lot of insecurity in their lives. These experiences are likely to make it harder for people to tolerate uncertainty, and to start the chains of thinking that keep worry going.

What was your experience of uncertainty growing up? Did anyone or anything make life overly certain or overly uncertain at some stage of your life?

People with GAD tend to worry about the same kinds of things as people without GAD – only they fall into worrying more easily and tend to spend more time worrying. Regardless of whether you worry a little or a lot, research suggests that our worry tends to cluster around particular themes. These include our health, finances, relationships, family, work or study, and finally worrying about worrying. Because they are worrying so much, worriers tend to start to worry about what their worry may be doing to them. So, although worry feels like a whirlwind with an unpredictable course, there are patterns and it tends to swirl around a number of themes that reflect the things that are important to us. These worry themes typically mirror the stage of life we find ourselves in.

What are the things that you worry about most? Which worry themes are most common for you?

Worriers tend to worry more often and for longer periods of time and believe that their worry is more out of control than people with everyday worry. However, and as we have said, it would appear that a worrier’s relationship with uncertainty helps explain most about why they worry so much.

Does a little bit of uncertainty start you worrying?

A large number of people with GAD will have more than one psychological problem. The most common problems that co-exist with worry are depression and the other anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety, panic attacks or health anxiety. About 70 per cent of people with GAD report depressive problems at some point in their lives.

What else might be going on for you? Are there other key chapters in this book that might be helpful to read?

Tips for supporters

• Go through this chapter together to help the person you are supporting – and you – understand how they are worrying and how it affects them.

• When we have asked a question in this chapter, encourage the person you are supporting to think about how it applies to them.

• If you have seen them do any of the things we ask about, use these examples to help them understand what is going on.

• Talk to them about how you might be able to help them as they go through the book. Can you meet once a week to discuss their progress? Help them to make a plan of what to do? Can you offer a thoughtful, compassionate perspective on their worry?

• Ask them if they want you to remind them to complete their diary.

• Ask if they need help separating the types of worry outlined in this section.

• Help them to figure out what might be an early warning sign of their worry.

Now that you have read the first section of this chapter you understand more about worry, and you will have had the chance to make notes of how the ideas we have discussed apply to you. If you have not done so, then it might be an idea to go back over the section now. If you have a supporter, then ask them to help you think about how the questions apply to you.

Some people find the diagram that we showed of Richard’s worry spiral helpful in understanding what happens to them (see Figure 8.2). Look at the exercise below and see if you can create your own diagram (there is a blank version underneath the completed version below).

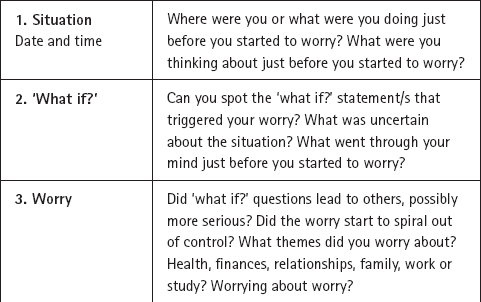

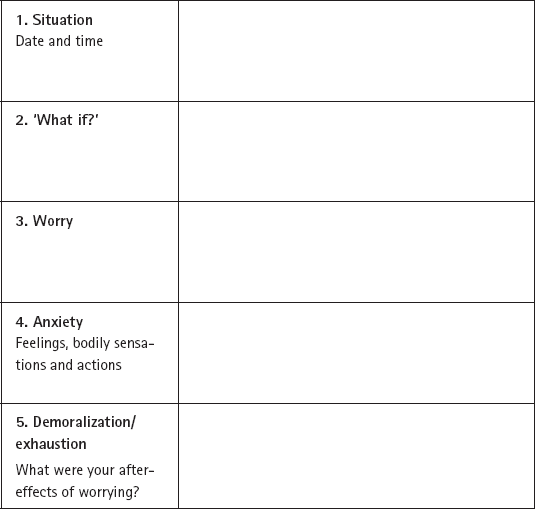

Exercise 8.2: Questions to help develop your worry diagram

Thinking about a recent bout of worry, can you use Figure 8.2 to help track how your worry develops? Use the following questions to help you to complete this.

You could use the blank sheet below to help you complete the questions.

Worksheet 8.1: Questions to help develop your worry diagram

Some people find it helpful to keep a diary of their worries. If you would like to do this, then it is most helpful if you write things down as soon as you can. So when you start to worry, get out your notebook, your phone or your tablet, and make a note of what is going on in your mind. This can have a lot of different purposes. For one thing, if you make up your mind that every time you start to worry you will write it down then it might help to break into the spiral of worry. And for another, it might help you to see that as you progress through the stages of treatment in this chapter, things start to improve and you make fewer entries!

Try to keep a diary of your worry over the next week or two. You can use the information you gather for other exercises later in this chapter. If it’s possible to write things down as soon as you notice you have started to worry then that would be good. But sometimes it’s not practical to do so, so work out two or three times a day when you can sit down undisturbed and think back over the past few hours. It might help to ask yourself the questions from Worksheet 8.1 when you realize that you are worrying.

When you have recorded your worry for a week or so, you could ask yourself the following questions:

• When and where do you worry the most? Are there particular situations that tend to trigger your worry?

• What are the things that you worry about most often? Are there recurring themes in what you worry most about? Using your worry themes, now go back to the questions on p. 205: ‘Spotting your positive worry beliefs’. Does this help you to understand why you worry so much about these things?

• Do your worries represent real events or are they hypothetical worries?

When you are trying to make changes, it can help to try to be clear about what you would like to achieve, or what your goals are. We talked in Part 1 of the book about how to frame your goals (p. 24). Just a quick reminder – goals should be SMART:

Specific

Measurable

Achievable

Realistic

Time limited

So don’t make your goal ‘I want to be free of anxiety for evermore!’ Think about how worrying is affecting you at the moment. Does worry stop you doing things that you’d like to be able to do?

For instance, you might worry so much that you won’t let your children go on school trips. So, a goal might be: ‘I will let my children go on the school trip and find a way to cope with my worry while they’re away.’ Richard’s goal might be: ‘I will delegate more to my colleagues’; ‘I will not ring to check where my girlfriend is.’

You could also make goals about how you will carry out changes: for instance, a realistic goal might be: ‘I will catch myself asking “what if?” questions and make sure I stop.’

You could look at the questions below to help you to formulate your goals:

• How does worrying make you feel?

• How would your relationships/friendships/work life/social life/ school, etc., be improved if you worried less?

• What would you notice if you worried less?

• What things could you do with your time if you worried less?

Use these questions to help you think about what you would like to change if you worried less, and how these changes could become your goals.

By now you will know if worry is a significant problem for you. We have used a diagram to help you to track how your worries develop and have described how important the intolerance of uncertainty is when you worry. We started you thinking about whether your worry is based on real or hypothetical events, and whether you have ideas about worry that keep it going.

Based on these ideas, we will introduce four treatment approaches:

1. Helping you to tolerate uncertainty.

2. Solving life’s problems: dealing with real event worry.

3. Overcoming avoidance: dealing with hypothetical event worry.

4. Dealing with beliefs about worry.

Remember one size does not fit all and some things we describe may not be relevant to you. Read through and see which of these ideas will help you most.

Before we start, think about how worry or uncertainty has limited the way you live your life. What could be the advantages of accepting a little more uncertainty into your life? Could there be any disadvantages? What are the advantages of letting go of certainty and having new experiences?

We have seen that uncertainty plays an important part in worry, and that people who worry find it extremely difficult to tolerate this. So we need to find a way to help people to get used to the idea of uncertainty, and to stop asking the ‘what if?’ questions that fuel worry. This is done by gradually increasing their exposure to uncertainty, and by introducing more flexibility into how people live their lives.

But this can be difficult, and you may need to think about preparing yourself to change. One way to do this is to recognize that there is almost always a cost associated with the strategies that you use to manage uncertainty.

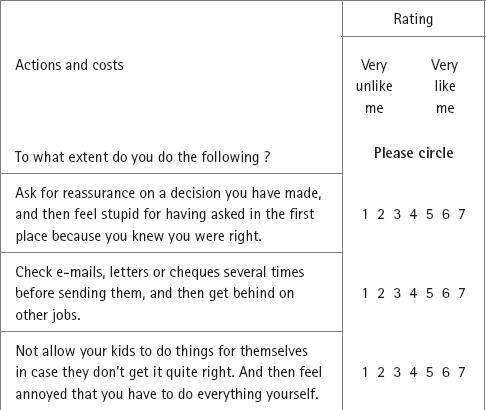

Exercise 8.3: How the intolerance of uncertainty influences our actions

The table below highlights the costs associated with how worriers manage uncertainty. Complete the questionnaire, and then choose one or two items and think about the gains or benefits you would get if you could tolerate the uncertainty and do things in a different way. Maybe completing this questionnaire will give you some ideas about what needs to change in your life.

Having reviewed the exercise above – are you now ready to learn how to tolerate uncertainty better? Changing your behaviour is about finding out something new, by doing something differently. This means rather than avoiding uncertain situations, you will need to begin to seek out increasingly uncertain situations on purpose to see what happens. We do not expect you to dive into the deep end of uncertainty. To begin with, it is much better to think about small, manageable and realistic steps. Expect to feel anxious and underconfident, and expect to worry more when trying new things out. We all do! But also, look for the hidden benefits, such as greater variety or better relationships.

Take a moment to think practically about what you could do to introduce a little uncertainty into your life on purpose so that you can learn to tolerate it a bit better.

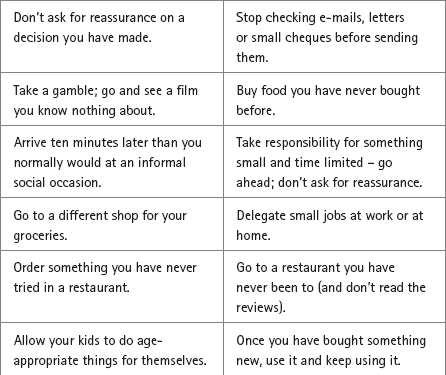

Exercise 8.4: Some ideas about what you could do to help yourself experience a bit more uncertainty

See the table below for some ideas about what you could try. Highlight those that are relevant to you and then decide to take a risk and try something new. Or make your own list from things that you know you would like to try in your own life if you could.

To help you decide where to start, give each ‘new’ thing a rating of 0 to 10 about how much worry it would cause you (0 is none at all; 10 is the most worried you can be). Then choose something that you have given a rating of 3–4, and start there. When you have managed that new activity, you will ideally feel more confident to try items with a higher rating.

When you start to make these changes you are likely to feel quite nervous and worried. Try not to let the worry stop you from doing what you have decided to do – we know that anxiety does wear off if people can just sit tight and expose themselves to the things that frighten them. We have talked about this in other sections of this book, including Part 1 and Chapter 6 on specific phobias. Make up your mind what you are going to do, and then do it!

And, as a popular contemporary writer (Susan Kennedy, aka SARK) suggests, ‘make friends with freedom and uncertainty’.

Tips for supporters

• Don’t expect big changes to start with.

• If someone is intolerant of uncertainty, even small changes will take them out of their comfort zone.

• Encourage them, but let them set the pace.

• You can model trying new things, but they have to do it for themselves.

Go back and have a look at Table 8.1 on pp. 203–4 about the difference between real and hypothetical worries. Do your own ‘real event’ worries escalate into much more catastrophic fears about what might happen in the future?

To overcome your worry it is important to become much more aware of when your worry starts to spiral from real to hypothetical.

For now let us consider how we can separate out the two types of worry. The questions below should help you to recognize when your worry has become much more hypothetical.

Exercise 8.5: Using your worry diary, or thinking about the last thing you worried about, try to answer the following questions:

• Is the thing that I am worrying about something that actually exists now? Can I describe the issue that I am worrying about in concrete terms with a time, date and a place? Would someone else be able to ‘see’ the issue, e.g. the credit card bill, the disgruntled partner, the pile of work to do, the kids being difficult, and so on?

• How far into the future has my worry taken me? A day, a week, a month, three months, a year, five years, fifteen years?

• Could something be done about it? Could someone else solve this? (In theory, is this issue solvable?)

• If yes, then could I do something about it (even though I may worry that I may not be able to do it right)?

If this bout of worry is about a real current problem, then the next step is to think about how to solve it – the pages below give tips on how.

If not, then this must be a hypothetical worry, and you can try to manage this differently (see pp. 202–4).

Worriers tend to see problems as threatening, doubt their ability to cope with problems, and tend to be pessimistic about the outcome even if they engage in problem solving. Is this true for you? These beliefs then set up vicious cycles since failing to engage in solving problems tends to reinforce these ideas. There is no evidence to suggest that worriers are worse at problem solving than non-worriers; it is only their beliefs about their problem solving that are different, not their skills.

Sometimes, worriers can confuse worrying with solving problems. While it sometimes feels like we are doing something about our problems by worrying about them, in reality, we are usually not. Problem solving requires a very different style of thinking from worrying. For instance, problem solving is characterized more by questions that begin ‘how’, ‘when’, ‘where’, whereas worry questions tend to begin with ‘why’ or ‘what if’. Another way to check the difference is to ask yourself, ‘Have I come up with a solution, or am I just going over the same problems again and again?’

Problems are a normal part of life: we encounter them all the time and we successfully solve many of them without realizing this. But sometimes we approach problems in an unhelpful way. Have a look at the list below and see if any of these relate to you. Each item in the list is followed by a question or suggestion to help you think about how you might approach problems differently.

1. Do you avoid or delay solving the problem? Worriers tend to avoid or delay solving problems. As a result of this, what could be a minor problem to start with gets progressively worse, leading to more severe problems and stimulating even more worry (for example, avoiding paying credit card bills, leading to charges and increasing debt).

Can you start to face the problems before they escalate?

2. Do you try not to think about problems, or put them to the back of your mind? As long as a problem is still a problem, it will butt in until we deal with it.

Starting with the easiest, can you make a list of problems that need to be solved and start to solve them?

3. Do you ask others to solve problems for you? If we continually ask others to solve problems for us, then this means we deny ourselves the opportunity of finding out that we could manage the problem for ourselves.

Can you start to solve problems for yourself?

4. Do you solve problems impulsively? Another way of dealing with problems is to respond impulsively to them, without thinking things through. Often, attempting to solve problems in this way leads to hurried or incomplete solutions, or solutions that make the problem worse.

Can you slow your problem solving down and think things through?

5. Do you try to solve too many problems at once? Worry has the tendency to multiply and expand, and this pattern echoes in problem solving. Often worriers will partially engage in trying to solve one problem, and then flip-flop between this and other problems. As their attention is divided, this can mean that nothing gets done and all of the problems remain in a semi-solved state.

Having made a list of problems, start with one – solve this before moving on to the next.

6. Do you flip-flop between approaching a problem and then avoiding it? This is another common kind of pattern that worriers unwittingly fall into: they approach a problem and then flit between trying to solve the problem by doing something purposeful and then avoiding the problem.

Can you keep engaged with a problem until it is solved?

7. Do you pre-judge the outcome of your problem-solving efforts? Often worriers will think that whatever they do, the problem will turn out badly; they are, in essence, negatively pre-judging themselves.

Remind yourself of all the problems you have solved; how is this problem different?

8. Do you over-analyse things? A worrier might think of all the possible ways that the problem could be solved and the outcomes of each solution, with each solution generating more problems, which require more solutions, and so on. This results in the worrier getting lost within the labyrinth of alternatives, getting overwhelmed, and never solving the problems.

Can you limit the time you need to solve a problem?

Use your worry diary to help you think about the types of problems that triggered your worry. How did you respond to the problem? Having read the above list, has it suggested how you might do things differently now?

Research tells us that people who worry excessively do possess problem-solving skills: their skills are as good as anyone else’s. In case you are not confident about your skills, here is a quick refresher based on what works well in most circumstances. It may be beneficial to spend time focusing on developing your problem-solving skills.

Exercise 8.6: Quick problem solving

Use the guide in the table below to help you solve a minor problem first and see how you go. Then, try another one, and then work up to starting to solve the more major ones.

• What’s the problem? Choose a problem that is

° not life changing

(i.e. relatively simple and small);

° not involving or depending on others;

° one where you can see the result quickly.

• Describe the problem in practical terms.

• Break it down into mini-steps – can you separate out a series of things that would need to be done to tackle the problem?

• What is the first step in the sequence? What is the first thing you need to do?

• At this point, what are the options? Think of all the possible things you could do to tackle the problem, even if some of them seem a bit unrealistic. Just let yourself ‘brainstorm’ everything that might change things.

• Spend a bit of time thinking about each of these solutions or options.

• Choose the one that seems slightly better than the others. Slightly better in this case means real, the simplest, most likely to succeed, with minimum cost (time, effort, money, etc.) and with a good result.

• Review what happened. Was the outcome at least ‘OK’?

• If not, then try another option. If it did work, then go on to the next step.

• Think about what happened to your worry about this problem. Ideally, as you engaged in more active problem solving your worry became a bit more manageable.

Tips for supporters

• Help the person you are supporting to notice the (many) problems they are probably solving successfully – despite the worry – and to realize that they do have problem-solving skills.

• Help the worrier notice whether they are approaching problems in an unhelpful way, as outlined in the list above.

• Help them choose the right (in other words, small) problems to start with, not necessarily the one that is bugging you the most!

• Provide support and encouragement, but not advice; worriers need to do it by themselves.

Now, we turn our attention to the type of worry for which we cannot use problem solving: hypothetical event worry. In this type of worry, we tend to imagine scenarios that would be catastrophic if they happened. Then we react emotionally as if these imagined, or hypothetical, scenarios are real. We feel as terrible as if the things had really happened, even though they haven’t.

Hypothetical worries typically involve themes of loss of loved ones, rejection by others, breakdown of important relationships, loss of financial security, illness and suffering, and the inability to face or cope with any of these. At the heart of these worries lie our dreams and aspirations, like wanting to be a good parent, or to be in good health, or to have financial security. All of us are afraid when the things we value are threatened. Can you return to the themes of worry that you discovered in Exercise 8.2 question 3? What are your aspirations? What does your worry threaten?

For worriers, the things that threaten these aspirations are hypothetical event worries – things that could happen, haven’t happened yet, and in all probability will never happen – but if they did, it would be terrible.

As you have learned, real event worry about everyday problems can soon turn into hypothetical event worry. If we are able to track a hypothetical worry back to a real event then we can use problem solving to help. If, on the other hand, the worry is more hypothetical, we cannot solve a problem that only exists in our imagination; in this case we need to learn to face our fears. Working on hypothetical event worry is about learning to face the real thoughts and images within the worry itself.

When we were children, we believed that there were monsters under the bed. You may have done as well. If so, what did you do to keep yourself safe from the monster? What went through your mind as you lay in bed? Did pictures flash into your mind, which then triggered worry? For instance, ‘what if it gets me’, ‘what if no one hears’? Does this sound familiar? How did these imaginings affect your behaviour? Did you run and jump into bed for example, or pull up the bedclothes, keep the light on, and keep your arms and legs inside the covers?

Exercise 8.7: Identifying your avoidance technique

To solve the problem of the monster under the bed we have to overcome the natural avoidance of the monster. There are different types of avoidance; some are more subtle than others. Review the following list – which ones do you use when faced with your worries?

1. Suppression: This is a way that worriers try to avoid worrying thoughts and images by pushing them to the back of their mind or by trying not to think about them. Unfortunately, this rarely works for long, as trying not to think about something will tend to make us think about it all the more.

Can you see how this might apply to your worry? What happens when you try to push worrying thoughts or images out of your mind?

2. Distraction: This is when we give ourselves mental or physical tasks so we don’t have the ‘space’ to worry. For example, cleaning the house or putting things in order, like grocery cupboards or toolboxes. Once the distracting activity stops, the worry creeps back in as it is more than likely linked to some unfinished business that will keep demanding our attention until we deal with it.

Do you distract yourself from your worries?

3. Avoidance of mental pictures in worry: We mostly worry in words not pictures. When images do appear in worry, they tend to ‘pop up’ in our minds, appearing and disappearing very quickly. We want to escape the images because of what they show, namely raw, awful and horrible things that no one would want to dwell on. The images provoke strong feelings, physical sensations, and other streams of worry. To help you understand this, consider the following: hearing someone recount the storyline of a horror film will never be as scary as watching it – the bare facts of the story you listen to don’t have the atmospherics that a skilful director creates with images.

If you have images that pop up, do you try to move away from them in your mind?

4. Mental gymnastics; changing the detail of our worry: Many people try to twist and turn away from the images or thoughts in their hypothetical worry. For example, we may try to dilute the awful worry by thinking about something else, or replacing negative images or thoughts with positive ones. The overall impact of all these mental gymnastics is that the worrier fails to face their fear, which maintains their worry.

Do you try to take the sting out of the scary parts of your worry by getting caught up in minor details like watching a horror film, concentrating on what the villain is wearing rather than the weapon he is carrying?

5. Avoidance of situations: The worrier tries to avoid situations or events that match closely with what they imagine in their hypothetical event worry. For instance if you imagined that your partner might have a car accident, you may pressure them into taking the train or using the bus, not based on anything other than what you have ‘seen’ in your hypothetical worry.

Do you avoid situations or events (or ask others to) that match or could trigger what you see in your worry?

In the ‘monsters’ metaphor on pp. 232–3, in order to overcome the fear, the bottom line is that the child needs to face the fear to learn that there is nothing under the bed. With hypothetical event worry this would mean facing the content of our worry while also dropping our efforts at avoidance: namely, suppression, distraction, pushing images away and mental gymnastics.

You may feel daunted by this, which is entirely understandable. You may say to yourself, ‘This will make my worry much worse!’ Remember that you probably experience these nightmarish daydreams at least every day and often for prolonged periods of time, and that trying to avoid them or not thinking about them has made no difference.

It is normal to feel upset when you start to face your fears because the ideas in our worry can be really terrible. It is precisely because you really care about the things you worry about that it is so upsetting. Being able to tolerate upsetting thoughts and images will not make you insensitive or uncaring. It will mean that you can, in fact, start to tell the difference between thoughts and reality. Imagine not being terrified by your worry, but being able to participate and enjoy the moment, living, not worrying.

In general, to help someone overcome their fear we would get them to confront it, or expose themselves to it. In order for this exposure to work they have to stay with the thing they are frightened of until their anxiety comes down naturally – which it will. You will probably be concerned that the anxiety will not reduce and that it will spiral out of control, but this just isn’t the case. Our anxiety does come down, even without us doing anything to make it come down. We have to learn to allow the wave of fear to wash over us, letting go of all our attempts to avoid or control it, in order to find out that nothing bad will happen.

To work with your hypothetical event worry, it is important to sit with the feelings without doing anything to make the situation or your feelings better. Learn that hypothetical event worry is a stream of thoughts. These thoughts do not describe real events. They are not facts. They are not premonitions. They are just thoughts. They are the by-products of your imagination, revolving around things that are important to you.

Exercise 8.8: Writing down your hypothetical event worry

Choose a quiet moment, a time when you know that you will not be disturbed – it’s probably better not to do this late at night, when worries can get magnified and can be harder than usual to switch off. Choose a hypothetical event worry from your worry diary. Imagine that you had to help someone to make a movie of your worry and think of all the details they would need to know. Think about when the worry is happening – next week, next year, or at some indeterminate time. Describe what is happening, what you think, feel, do, see, hear, etc. Do not censor yourself; everything needs to go down on the page.

Sometimes it might feel like the worry has no ending. Keep writing until you have passed what might be the worst moment, or if you notice that you are going around in a circle. We are also trying to help you to learn to ‘sit’ with uncertainty, in other words, to learn to tolerate it better, and so it is not about finding a good ending; actually it is better if the ending is left hanging, with a question such as ‘when will this ever end?’ or ‘who knows where this will lead?’ Endings like these are designed to trigger uncertainty and so maximize your exposure to it.

Review what you have written. Have you avoided including anything?

Take the final and detailed version of your hypothetical event worry and read and re-read it for up to thirty minutes a day. It can help to make an audio recording of it on an MP3 player or a CD and listen to it. Use the form below to record the experience of reading through it. Note that the form asks you to rate your anxiety before, during, and afterwards, using the scale provided. You should find that once you have let yourself concentrate on the worry in this way, your anxiety will start to wear off, and you will find it much easier to think about the worry. Once you have done this with one worry, choose another, until your worries will feel much more manageable.

When you have done this you should find that your relationship to your hypothetical event worries has changed, and that you recognize them for what they are. Can you recognize them sooner now? Are you able to interrupt them, or have you found things that you can say to help you to ‘put the brakes on’?

Fill out this worksheet each time you face your hypothetical event worry. Use the scale below to rate your anxiety or discomfort. Remember you need to work with your worry for long enough for the feelings to reduce.

Worksheet 8.2: Rate your anxiety/discomfort

Anxiety/discomfort scale

Session No._________

Day or date _______________ Start time ___:___ Finish time ___:___

Place _______________________ Worry _______________________

Anxiety/discomfort Before ____ During (max) ____ After ____ (please use scale)

Did you use any avoidance strategies? No ____ A little ____ A lot ____

How did you avoid?________________________________________

Tip for supporters

This may be hard for you, too. The horrible things they may imagine are because they care so much. If you are supporting a close friend or relative, then sometimes the hypothetical worry will be about you or someone you care about. If you share some of the concerns that the person you are supporting has it may be harder to help them to see that the worry is just a thought. Just remind yourself of the ideas in the section above, and make sure that you know the difference too!

Go back to the description of the beliefs about worry on pp. 205–7. The basic idea is to begin to see that the rules about worry actually make you worry more. The two kinds of beliefs – positive and negative – require slightly different approaches.

We have seen that positive beliefs about worry make you think that worry is useful. The beliefs make you feel that worry helps your motivation, show that you are a decent person, help you to prepare for bad things that might happen. So, one way to try to reduce the amount of time you spend worrying in this way is to think about other ways in which you can achieve the goals.

Are there better ways than worrying to show that you care?

How else could you motivate yourself to work hard?

You could also try talking to other people to see what they say. Would they agree that worrying beforehand prepares them for the worst? Or might they think that worrying in this way makes them feel so bad that they actually feel too stressed out to cope with anything?

It could also be helpful to work out exactly how worrying might have an impact on events. For example, how does worrying about the kids keep them safe?

Below are some examples of worry rules to help you think about how you can learn to work with them and learn to bend and break them.

We talked about some of the negative beliefs about worry. These would be things like ‘worry will drive me insane’ or ‘I will lose control’. These beliefs actually make you feel more anxious and drive the worry on and so it is a good idea to try to tackle these ideas. One way to do this is to think about what has happened in the past. You have worried a lot. But have you ever gone insane or lost control?

How did you stop yourself from going insane or losing control (e.g. counting, making sure you can still read, doing sums in your head, etc.)? Do you feel able to drop this and find out what happens? Focus on a smaller worry to start with and see if you can actually drive yourself insane or lose control (we wouldn’t be suggesting this if we thought it might work!). Then pick a larger worry and do the same. And so on.

It might help to go back to Part 1 to remind yourself how to tackle anxious thoughts.

Tips for supporters

• Often people don’t realize that they have these beliefs, so helping someone to look at the lists and recognize the beliefs can be a really important first step.

• Try to help the person you are supporting to find different ways of achieving the positive results they think worry brings.

• Try to help the person to challenge the negative beliefs about worry by looking for evidence and using other techniques used in the thought-challenging section of Part 1.

Reading this chapter is only the start. These ideas and techniques now need to become part of the way you live your life: welcoming uncertainty into your life and taking small risks, solving life’s problems rather than simply worrying excessively, and recognizing that your worry is only just that – worry.

• Although it is difficult, adopting an understanding and supportive stance that encourages trying new things is likely to be the most successful in the longer term.

• Remember that the worrier needs to learn to do things for themselves.

• Remind the worrier that doing new things is likely to make them feel anxious and frightened, but the anxiety will wear off once they start doing things differently.

• Although the upheaval may be uncomfortable, there will be rewards. Not only will the worrier be less caught up in worry, but also more open to new experiences as they learn to first tolerate and then embrace uncertainty.

• Remember that change takes time, particularly if people have been worrying for a long time. For most of us, change takes place in very small steps, not in one dramatic quick episode. So help the person you are supporting to notice small changes, and to feel proud that they are trying so hard!