Kissing Cousins: The Gut and the Mouth

“The oral cavity serves as a window into the intestinal tract.”

—M. J. Docktor et al.97

If you have been waiting to read about the magnificent microbiome of the gut, here is your opportunity! The gut microbiome is a heavyweight compared to the oral microbiome. But the mouth and the gut have so many similarities, there is no way to talk about them except as intimately interrelated—as kissing cousins. In Chapters 3, 4, and 5 we talked about the mucosal membrane, the immune system, and the complex communities of microbes that live in our mouths, respectively. In this chapter we can see how the prime location of the mouth can directly influence the gut microbiome. We may be able to trace the origins of diseases in the gut back to the mouth. In this way, the oral cavity is linked not only with the entire GI tract but also with the rest of the body.

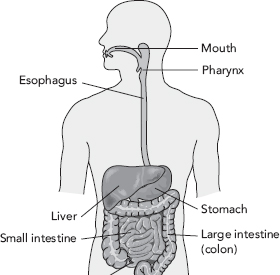

The gastrointestinal tract has been in the spotlight for centuries. Even Hippocrates thought the gut was vital to health when he said, “All disease begins in the gut.” Indeed, many clinicians who treat the root causes of disease, not just the symptoms, often restore health to the gut first because it can influence health of the immune system, liver, joints, skin, brain, and more. The gastrointestinal tract is a series of hollow organs joined together in a long twisting tube that is nearly 30 feet long from mouth to anus, and whose surface area covers the space of a studio apartment. It includes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestines, large intestines, and rectum. The GI tract is the machinery that helps us eat, drink, digest food, absorb nutrients, and get rid of waste. It does all of those things while still acting as a physical barrier against outside invaders and policing the forefront of the immune battlefield to keep bad stuff out of the systemic circulation (the bloodstream), where it doesn’t belong.

Seventy percent of your immune system lives in your gut. It monitors all of the foreign molecules passing through and will launch a fierce attack at the first hint of a malicious invader. The gut walks a tightrope between inflammation and peaceful harmony. But generally, the gut tries to keep things calm, harmonious, and in good working order. The immune system, which is so important in the gut, permeates the mouth in just the same way.

Hearkening back to earlier chapters, the landmark collaboration to characterize the human microbiome, the Human Microbiome Project funded by the National Institutes of Health, taught us that the human gut harbors 100 trillion bacteria that influence nutrition, immune function, metabolism, obesity, mood, cancer initiation, and susceptibility to infection. The gut also has its own nervous system, the enteric nervous system, which has been called the “second brain.” There are 200 to 600 million neurons in the gut, which use more than 30 neurotransmitters (brain chemicals). Additionally, 95 percent of the body’s good mood chemical, serotonin, is found in the gut.98

Compared to the gut’s 100 trillion bacteria, its kissing cousin, the mouth, is estimated to have only 20 billion microbes. The vast majority of our microbial inhabitants live in the gastrointestinal tract and that is why there has been, with good reason, a flurry of scientific research and consumer books about the gut microbiome. As discussed in Chapter 3, dysbiosis of the gut microbiome seems to be involved in a range of intestinal illnesses such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, and much more. Because the gut is so critical to overall health, evaluating and restoring gut function is a foundational clinical strategy in integrative and functional medicine. If you are looking for superior medical help with chronic illness, see Chapter 9, to find a functional medical practitioner in your area.

Gut dysbiosis symptoms and conditions include:

• Abdominal pain

• Asthma

• Autoimmune disease

• Bloating

• Constipation

• Diarrhea

• Eczema

• Gas

• Heartburn

• Inflammatory bowel disease

• Intestinal permeability (leaky gut)

• Irritable bowel syndrome

• Joint pain due to an infection in the joint

• Overweight or obesity

• Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

• Ulcer

• Vomiting

Similarities Between the Gut and the Mouth

Just by virtue of anatomy, the mouth is unavoidably hitched to the gut. The mouth and the gut share an epithelial lining that acts as a permeable physical barrier, responsible for keeping bad stuff out and letting good stuff in (discussed in Chapter 3). The mucosal membranes in the mouth and the gut are populated with a formidable immune defense, including cells that guard and police, those that fingerprint and book enemies at the headquarters, and “soldier” cells that replicate themselves, hunt down, and destroy enemies (covered in Chapter 4).

The mouth and the gut are loaded with microbes that mostly contribute to healthy metabolism, physiology, and immunology, but at times contribute to disease. In both the gut and the mouth, a healthy person carries around pathogens that give them no problem, as long as they have a strong, diverse microbiome. But dysbiosis of the oral or gut microbiome can open the window for a bad bug rising to power. Dysbiosis, together with immune reactions, can cause disease in the mouth and the gut. The foods we eat dramatically influence the microbes in our mouths and in our guts. And as mentioned in Chapter 5, how we are born (vaginal or C-section) and how we are nursed can either give us a healthy, diverse microbiome or a weak, puny microbiome in both places.

The mouth and gut are just two stops on the same bus line. Of course they are connected in terms of their microbes, their immune responses, and their diseases! And I hesitate to say problems in the mouth that are mirrored in the gut are “systemic diseases,” meaning diseases that affect the entire body, because the mouth is simply upstream of the gut. It’s the same tube, just farther down.

So many things you learn in this book about the oral microbiome can also be used to understand the gut microbiome (and the gut). And since these kissing cousins are so similar, after reading this book you can consider yourself knowledgeable not only about the mouth, but about the gut as well.

You’ve heard me say it before and you’ll hear me say it again. The mouth is at the headwaters of the gastrointestinal tract, and the mouth is where the immune system first encounters the outside world. In its infinite wisdom, it tags suspicious outsiders with the help of the immune protein called sIgA (page 28) and sends communications to the gut immune system to beware of and prepare for them. The microbial communities living in the mouth flow downstream by way of saliva to the tune of 140 billion bacteria per day!99, 100, 101 The mouth is therefore “seeding” the rest of the gastrointestinal tract with microbes on a daily basis.

It is no surprise, then, that human microbiome scientists have found a whopping 45 percent overlap between the oral and colonic microbiota. Nearly 50 percent of the microbiomes in the oral cavity and the gut are the same. Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla bacteria are dominant in both the oral and gut microbiomes. As I mentioned previously, one reason I have come to love the oral microbiome is that it strongly influences the composition of the gut microbiome.102

Figure 7.1: The human digestive tract includes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. Since the mouth is at the headwaters of the gastrointestinal tract, it has an influence on everything downstream.

The constant flowing of saliva, chewing of food, and brushing of teeth removes bacteria from the oral cavity and pushes them downstream, toward the GI tract.103 This is great if there is a healthy, rich oral microbial ecology in the mouth. But if there is dysbiosis or pathogenic bacteria in the mouth, it can provide a continual source of problematic microbes to the gut. This could result in chronic, recurrent dysbiosis in the stomach, small intestine, or colon that are resistant to the usual treatments.

There are two things in life that a sage must preserve at every sacrifice, the coats of his stomach and the enamel of his teeth. Some evils admit of consolations, but there are no comforters for dyspepsia and the toothache.

—Henry Lytton Bulwer, British politician, diplomat, and writer

Helicobacter pylori may be a perfect example of an unwelcome guest. H. pylori is a type of bacteria that can burrow into the epithelial lining of the stomach and damage the cells there. This exposes the underlying stomach tissues to very high acid levels, which makes matters worse and can even create sores called ulcers. Robin Warren and Barry Marshall were awarded the Nobel prize in 2005 for discovering that H. pylori could cause stomach ulcers, gastritis (inflammation of the stomach lining causing pain, nausea, vomiting, or a sense of fullness), and gastric cancer.

Helicobacter pylori has been evolving with us for well over 50,000 years.104 In recent years, some researchers have suggested that H. pylori may not be a bad guy all the time. Many people have H. pylori and don’t have any symptoms and never will. Since 50 percent of people have H. pylori and most have no symptoms, they say it may be a commensal organism and that it might even protect against developing certain allergies, esophageal cancer, heartburn, and obesity.105, 106 This is often the confusion around microbes. They can be bad in certain situations and good in others. Labeling a microbe as “good” or “bad” is not cut and dry. It often depends on the other microbes in the mix and the person’s immune system and environment.

I was surprised and fascinated to find out that H. pylori lives in dental plaques in the mouth! Researchers have discovered that when someone has a stomach infection with H. pylori, there’s a good chance that it’s living on their teeth as well. It seems that H. pylori living on the teeth can be a continuous source of H. pylori to the stomach, making it hard to get rid of even with all the appropriate treatments. In one study of people with stomach ulcers, those who had regular dental cleanings were able to get rid of H. pylori infection more effectively. For their counterparts who didn’t get a dental cleaning to remove plaque, nearly 85 percent had a relapse of the H. pylori infection.107, 108

The moral of the story here is that if you have chronic upper GI symptoms, you and your doctor might want to review your oral health. Bacteria living on our teeth can take the “waterslide” down the esophagus and dive right into the stomach, small intestine, or large intestine.

There is some interesting overlap between bowel diseases and oral diseases, too. Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis affect approximately 250 out of every 100,000 Americans.109, 110 These conditions are characterized by rampant, uncontrolled inflammation that leads to gastrointestinal tissue injury. People with IBD may have abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, fever, weight loss, and even malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies. The causes are yet unknown, but an over-the-top immune response to gut microbiota and damage to the intestinal barrier are central features of these diseases.111. 112 Sound familiar?

Patients with IBD often have inflammation of the oral mucosa, too. Up to 80 percent of patients with Crohn’s disease have symptoms of oral disease. In children who were newly diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, 42 percent had oral symptoms. Inflammation in the mouth may be mild or severe, and it may begin years before any sign of inflammatory bowel disease begins.113 This makes you wonder if the signs of illness show up first in the mouth.

People with inflammatory bowel disease often have lost some of the healthy diversity and richness of their intestinal microbiome. One study found that in Crohn’s disease, changes to the oral microbiota paralleled the changes in the intestinal microbiota. Both microbiomes were decreased and less diverse. They were both missing bacteria from the Fusobacteria and Firmicutes phyla.114

The First Time I Realized You Could Fix the Gut by Fixing the Mouth

When I worked at Metametrix Clinical Laboratory, I often reviewed lab results with a nutrition practitioner who grew to be a friend. In addition to running tests on her patients, “Jan” also ran tests on herself because she was trying to resolve some stubborn gut symptoms. Jan had indigestion, stomach pain, bloating, and loose stools even though she had an extraordinarily healthy diet for many years and took supplements to keep her gut healthy and improve digestion. Jan ran a urinary organic acids test, which measures by-products of bacteria that live in the small intestine. Jan’s test showed very high levels of these bacterial metabolites, so we knew that she had high amounts of bacterial overgrowth in her small intestine. Her test results matched her chronic gut symptoms. Jan treated herself with antimicrobial herbs, digestive enzymes, and made changes to her diet to try to cure herself of bacterial dysbiosis, but to no avail. She ran a few tests on herself over the course of two years and every time, her gut showed rampant bacterial overgrowth, resistant to any and all treatments. Since her mother had not breastfed her, we wondered if her stubborn dysbiosis had begun when she was a baby and perhaps was unchangeable. Finally, one day Jan called in to discuss another set of her test results, like we had every other time. But this time the results looked completely normal. Jan had resolved her bacterial dysbiosis for the first time in years! I was stunned and of course asked her, “What did you do?!” Jan told me that she had been to the periodontist to resolve some mouth issues she was having. Ever since, her gut symptoms seemed to be getting better, and eventually subsided. By improving her oral health, Jan had resolved her chronic GI symptoms and normalized her test results. Jan’s case stuck with me forever because it showed me that the mouth plays an important role in gut health.

Patients with IBD are more likely to have periodontal disease and inflamed, loose, bleeding gums. They are also more likely to have worse dysbiosis under the gumline than people who only have periodontal disease without bowel disease.115

It is hard to determine which one comes first: inflammatory bowel disease or periodontal disease. We don’t know, and it may be a long time before we do, but there are striking similarities between the two conditions, including dysbiosis of the microbiota, damage to the mucosal membranes, and altered immune responses. In the meantime, experts suggest simultaneously treating the inflammation in the mouth and in the gut as a way to battle the combined challenge of oral disease and gastrointestinal disease.116 See Oral Microbiome Solutions (Chapter 9) for ideas on how to lower inflammation in the mouth, improve the oral microbiome, and eat foods that promote a healthier mouth and gut. If you struggle with IBD and periodontal disease, I strongly encourage you to find a functional medicine practitioner or a licensed naturopathic doctor to help you get a handle on both of these conditions and get your health back on track. Recommendations for finding a qualified practitioner are also located in Chapter 9.

My Journey to the Mouth Began with Poop

With an interest in natural medicine and a history studying medicinal plants in the rainforests of Panama, I started my career in natural product drug discovery at a start-up company at the University of Georgia. Shortly thereafter, my friend and labmate, Dr. Eve Bralley, suggested I apply for a job at her family company, Metametrix Clinical Laboratory. They sold lab tests to integrative doctors that helped figure out if a patient had healthy levels of vitamins, minerals, and hormones; whether they had food allergies; and more.

Not long after I started the job, Metametrix launched a test that had never been done by any other clinical laboratory up to that point. It was a stool test that used DNA technology to detect bacteria and fungi in the gut. There were many stool tests on the market, but none that used this state-of-the-art technology. We were applying something brand new and it took the market by storm. My job was to research, write, and teach about microbes in the gut and help doctors use our stool tests to get their patients well again.

Years later, I started my own medical communications business, and I was commissioned by Klaire Labs to write an article on the oral microbiome with Dr. Stephen Olmstead. You can imagine my delight! The topic of microbiology was near and dear to my heart after reviewing thousands of poop tests. The article was right up my alley and I loved writing it.

My dear friend and teacher Dr. Kara Fitzgerald, whom I knew from Metametrix, asked me to be a guest on her functional medicine podcast to discuss what I had learned about the oral microbiome while writing the paper. Our interview was a huge hit and she had a record number of viewers! For some reason, doctors and dentists loved the topic as much as we did.

A number of people sought me out after the podcast interview, including Dr. Mark Burhenne, a prominent dentist with a large online following. I did an interview with him and I continued to write blogs and articles on the topic. Finally, Ulysses Press contacted me. They felt that the market was ready for an oral microbiome book and the online articles and interviews led them straight to me. I was thrilled to be offered the opportunity.

Takeaways

• The gut microbiome is of major interest because gut health powerfully affects whole-body health.

• The gut and the mouth have so many similarities and are in close proximity; they are like “kissing cousins.”

• The vast majority of your microbes live in your large intestine.

• Ulcer-causing bacteria can live on dental plaque and can interfere with successful treatments.

• Inflammatory bowel disease is often accompanied by changes to the gut microbiome, the oral microbiome, and immune system responses.

• For stubborn illnesses of the gastrointestinal tract, oral dysbiosis could be a possible hidden cause.