A Tour of the Mouth

“The first thing I do in the morning is brush my teeth and sharpen my tongue.”

—Dorothy Parker, American writer

In this chapter, we will learn why the mouth is ideally suited for its microbial residents and how it influences the rest of the body. The mouth’s strategic location has immediate impacts on the immune system and on the gut microbiome. But aside from its prime location, the mouth has special qualities that appeal to the oral microbiome. One of those qualities is a constant flow of saliva, which washes away bacteria, carries food, and helps good bugs latch on to teeth. And you might think your gums, cheeks, tongue, and teeth have a lot in common, but your bacteria would beg to differ. In fact, each of these areas in the mouth caters to a different group of bacteria. Overall, the mouth is uniquely located at the headwaters of the GI tract, has a number of specialized habitats for bacteria, and is dependent on saliva. These are only some of the reasons that 20 billion bugs have taken up residence in our mouths!

One of the most important things about the mouth is its location. The mouth is uniquely situated at the front entrance of the body and the beginning of the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. That makes it the first point of entry for anything from the outside world. Indeed, there is a constant stream of foreign organisms into the mouth. Therefore, the immune system in the mouth has to be fierce and vigilant. It has to carefully and effectively differentiate good guys from bad. It has to attack and destroy harmful outsiders but welcome friendly outsiders. We are talking about identifying foods, water, minerals, vitamins, bacteria, fungi, parasites, toxins, and more. This is not a job for the faint of heart. It’s tough work. In Chapter 4, we will explore the incredible immune system that keeps us safe and in a state of harmony.

The mouth shares its immune system and its general architecture with the whole digestive tract. The digestive tract includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestines, and rectum. The mouth and the gut are essentially just two different stops on the same bus line, so they have a lot in common. Seventy percent of your immune system lives in your gut, specifically in the gut mucosa.23 Both the mouth and the gut are lined with a mucous membrane. This membrane acts as a physical barrier—a wall—to keep bad stuff out of the bloodstream. Later in this chapter, we will find out what the mucous membrane is made of, and in Chapters 7 and 8, we will discuss why it is crucial to a smart immune system, a healthy body, and low levels of inflammation.

Let’s take a quick tour of the mouth since it’s the home of the oral microbiome. Trust me, it’s pretty cool. There is so much more going on in there than you ever realized!

The mouth has two types of surfaces. You can feel them with your tongue right now. We have the oral mucosa, also known as the epithelial lining of the mouth, which is soft. Feel the inside of your cheek, your gums, the roof of your mouth, and the floor of your mouth. Those are mucous membranes. These cells turn over regularly, meaning old cells die and new ones grow constantly. Then we have the teeth, which are hard surfaces that are durable and unchanging (or so it seems to the naked eye).

The Barrier

The mucosal barrier is our defensive line. It is incredibly critical to our health and defense. This applies to the mucosal barrier not just in the mouth but throughout the gastrointestinal tract and beyond. Imagine if you didn’t have your skin as a barrier between your body and the outside world—you would be wide open to attack and infection. In the same way, your mouth lining is the barrier between the bloodstream and the constant stream of bacteria, food, and chemicals that comes into your mouth. Therefore, a strong and healthy barrier is an excellent way to keep your mouth healthy.

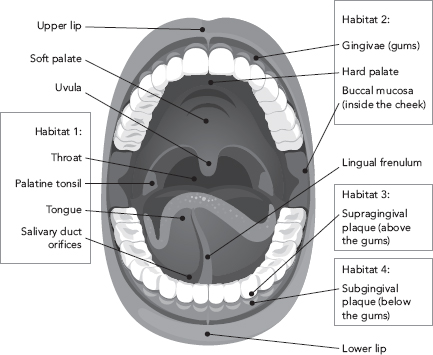

Figure 3.1: Anatomy of the mouth and different habitats for oral microbiota.

Mucous membranes line cavities or cover the surface of organs. They are made of one or more layers of a special type of cells called epithelial cells. Epithelial cells form a flexible, soft, and firm sheet of tissue that wraps around the framework of our organs and cavities. Underneath the sheet of epithelial cells is a type of connective tissue called the lamina propria, which is like cartilage, as well as blood and lymph vessels.

Our gums are essentially a layer of cartilage topped by a layer of epithelial tissue, which together cover the jawbone and surround our teeth snugly. This may sound complicated, but it’s really just like your skin, only it’s on the inside, and it’s slimy. Other mucous membranes line the lungs, nose, vagina, esophagus, and of course, the entire gastrointestinal tract. Cool design!

The oral mucosa lining the gums is actually thicker and denser than the gastrointestinal mucosa. It is also more porous and is exposed to a wide range of microbes and their products.24 The tissue in the mouth is officially described as stratified, squamous (scaly) epithelial tissue because it is flattened and has many layers. Just like your skin, the oral mucosa can handle lots of use because the thick layers of cells on top will slough off and be replaced by new layers that are constantly being produced deep below the surface. Mucin, also known as mucus, or snot (not so pretty, but now you know exactly what we’re talking about), covers the oral mucosa.

Another unique thing about the barrier in the mouth, as opposed to that in the gut, is that teeth penetrate the barrier. The mucous membrane on the gums surrounds teeth, forming an attachment and a seal. However, each tooth that extends through the oral mucosa represents a weak point in the barrier. As we’ll talk about later, microbiota colonize the teeth above the gumline and below the gumline, which mean that bacteria in our mouths are privy to the bloodstream.

That’s right. Despite this formidable barrier, bacteria from our mouths regularly get into our bloodstream. The oral mucosa is a “selectively permeable” barrier at best. While it does block many bad things from entry, it also lets a lot of things through, and sometimes it lets in too much. It has been shown that simply brushing your teeth or eating can lead to a surge of bacteria in your bloodstream, called “bacteremia.” This process may explain why oral health is intimately tied to the health of the heart, joints, and metabolism. We will discuss this further in Chapter 8.

Your Pearly Whites

Teeth are the hardest tissue in the body and are uniquely able to handle lots of wear, tear, and harsh conditions, such as high acid. There’s more than meets the eye when it comes to your sparkling whites. Your teeth are made of enamel, cementum, and pulp-dentine complex. Enamel is that ultra-hard, pretty, white surface on the crowns of your teeth. It is resistant to the acids we eat and the microbiota living in our mouths. Cementum is like enamel because it also coats the tooth, except it coats the roots of the tooth.

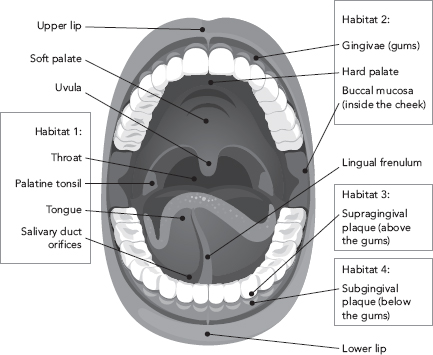

Figure 3.2: The pulp chamber at the center of the tooth contains nerves and a blood supply. Every tooth has a direct line into the bloodstream, which could explain why problems in the mouth can show up in the heart or joints.

As you can see in Figure 3.2, underneath the layer of enamel and cementum is dentin, which makes up most of the tooth. Dentin is composed of 10 percent water, 20 percent type 1 collagen, and 70 percent minerals. Specifically, dentin is mostly a blend of calcium, phosphorus, oxygen, and hydrogen called hydroxyapatite, which is the fundamental hard ingredient in teeth and bones. It’s like cement. Additionally, small percentages of magnesium, potassium, and sodium can be found in teeth. Fluorine is also found in teeth, primarily through water fluoridation, fluoride treatments, and toothpaste.25

One of the cool things about teeth and bones is that they are always under construction. Inside the dentin, teeth are constantly being broken down and rebuilt by “construction worker” cells, called osteoclasts and osteoblasts. This goes for bone as well. If you needed a super-strong bridge, wouldn’t you always have to maintain it? The result is a very strong and resilient hard tissue to chomp your food with. However, when teeth are broken down at a faster rate than they are getting rebuilt, this leaves an opening for microbes to damage the tooth further.26 We will talk about this more when we discuss cavities and the oral microbiome in Chapter 6.

At the very center of each tooth is pulp, where you can find blood vessels and nerves. Do you remember when you lost a baby tooth? Remember that hole on the underside/inside of the tooth? That’s where pulp would normally be. If you’ve ever had tooth pain or sensitivity, that’s because the pulp of the tooth was involved. Pulp acts like an alarm system for the tooth. It will tell you when there is a problem. Pulp contains blood vessels and nerves and osteoblasts, which make dentin. Each tooth has a line into the bloodstream via the pulp, meaning that the teeth are well connected to the whole body. It’s called the pulp-dentine complex because these two neighboring tissues work together closely to create the hard structure of teeth and keep them healthy.

Teeth are the hardest tissues in the body and are uniquely able to handle lots of wear, tear, and harsh conditions such as high acid.

I wouldn’t bore you with all of these details except that each of these areas in the mouth harbors different microbiota. Those little buggers are picky. Some live best in and on the throat, tonsils, saliva, and tongue. Other microbes live on the inside of the cheeks, the roof of the mouth (the hard palate), and gums (also known as the gingivae). There are whole communities of bugs that live on the teeth above the gumline, which are quite different from the bugs that live on the teeth below the gumline. The microbiota living in our mouths colonize all of these areas.

The reason we need to know a little about the anatomy of the mouth is because the bugs in our mouths like each of these areas for specific reasons. For example, the teeth don’t shed cells, so they are easier for microbes to hang on to. And the bugs that live under the gumline die if they get too much oxygen; they prefer to be buried, so that air can’t reach them.

A study of the oral microbiome showed that each of these areas is a distinct ecological niche. Despite being so close in proximity, very different bacterial communities colonize these sites:

• Throat, tonsils, saliva, and tongue

• Gums, cheeks, and roof of the mouth

• Supragingival plaque on teeth (microbes above the gumline)

• Subgingival plaque on teeth (microbes below the gumline)

Each of these areas in our mouths represents an ecological niche that, because of its unique characteristics, attracts and fosters the growth of particular communities of bacteria. An ecological niche is a fundamental concept in ecology and describes a relationship between a species and its environment. In an ecological niche, a species both shapes and is shaped by its environment. This hearkens back to Chapter 1, where we compared the microbiome to a biodiverse rainforest. Some plants like the sun, some like the shade, and some are in between. A rainforest has ecological niches that can support all of them. So does the mouth provide ecological niches to different types of bacteria that can then set up shop and call them home.

Amidst all of these different “ecological niches,” which I’m sure you never knew were in your mouth, is a sea of saliva. That, I’m sure, you did know about! Saliva is your best friend, believe it or not. It is absolutely vital for your mouth to stay healthy. Saliva controls the pH, or the acid-base balance, in your mouth by constantly keeping the calcium and phosphate levels high. Too much acid can damage teeth. Calcium and phosphate make the pH more basic, which helps build and repair healthy teeth (a process called mineralization) and wards off tooth damage and break-down.27 When the pH is just right, nutrient minerals like calcium and phosphorus can be formed into bones and teeth.

Saliva is packed with substances that protect you from unfriendly microbes and help to balance your microbiome. Saliva contains an enzyme called lysozyme, which defends you from bacteria by breaking down their cell walls. Enzymes are worker proteins that catalyze reactions, or change molecules in the body by acting on them. Saliva contains another enzyme called lactoperoxidase, which is antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and antiparasitic. It just so happens to help prevent cavities, gingivitis, and periodontal disease. Lactoferrin is a protein found in saliva, as well as breastmilk, that steals nutrients from bacteria as a way of starving them out. And saliva contains immune system proteins called immunoglobulins that bind up and eliminate bad stuff like pathogens or foreign food molecules that might be harmful. The immune defenses in the saliva are immunoglobulins A, G and M (IgA, IgG, and IgM for short).

Saliva supplies nutrition to the microbes in your mouth. It contains proline-rich glycoproteins (sugar-protein molecules) that help bacteria anchor to teeth. On the other hand, saliva cleans your mouth and washes bacteria off of your teeth. You might think of this as a continuous “trimming of the hedges.” While saliva makes it possible for bacteria to attach and live on teeth, it also continually washes over bacteria, freeing up some to be swallowed. Because bacteria are constantly shed from surfaces in the mouth, the saliva carries a lot of bacteria and is even a good specimen for measuring a person’s oral microbiome.28, 29

Each milliliter of saliva (roughly ¼ teaspoon) contains 140 million bacterial cells! The average person makes around a liter of saliva each day, which would come to 140 billion bacterial cells in saliva each day.

The mouth is a unique place and that’s why microbes love it. There’s plenty of food, a steady flow of saliva, and specialized habitats that appeal to their needs. There is a soft, flexible sheet of tissue called the epithelium that forms the mucous membranes in the mouth, which also serves as a physical barrier and immune system launching pad, making it critically important to our health. So, given what we learned about the layout and topography of the oral cavity in this chapter, we can move on to talk about the audacious immune system that walks a tightrope between attack and tolerance and how our good bugs help it do just that.

Takeaways

• The mouth is positioned at the entrance to the GI tract and is the first meeting place between your immune system and the outside world.

• The oral cavity has at least four different ecological niches that host different microbiota.

• A soft, flexible membrane of epithelial cells, called the oral mucosa, lines the oral cavity.

• The oral mucosa creates a physical barrier between the bloodstream and a constant stream of microorganisms in the mouth.

• Saliva fosters your oral microbiome by supplying nutrients, helping microbes attach to surfaces, and destroying enemy microbes.