Dysbiosis of the Oral Microbiome

“Every tooth in a man’s head is more valuable than a diamond.”

—Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote

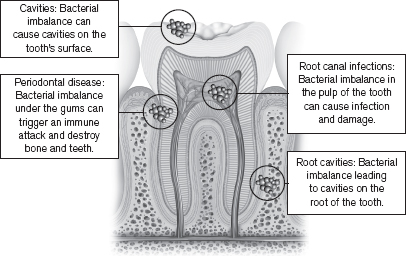

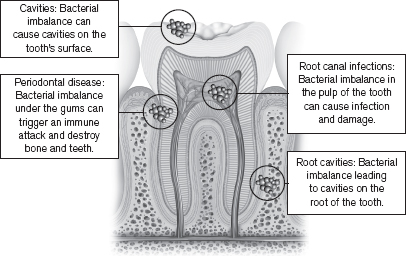

What do cavities, gingivitis, periodontal disease, root canals, and bad breath all have in common? They are all examples of dysbiosis of the microbiota in our mouths. It appears that our oral microbiome packs a punch! So, let’s not underestimate the bugs that live in and on us. An unhappy oral microbiome can make us unhappy on an everyday basis. In this chapter, we will talk about how imbalanced oral bugs can lead to problems right there in the mouth. In later chapters, we will see how that dysbiosis can spiral out of control and even harm our joints, gut, and cardiovascular systems.

Figure 6.1: Dysbiosis of the oral microbiota can cause cavities, root canal infections, and periodontal disease. Dysbiotic microbiota affect the crowns of the teeth (cavities), the pulp of the tooth (root canal infections), the roots of the teeth (root cavities), and the gums, periodontal ligament, and bone (periodontal disease).

In Chapter 1 we compared the microbiome to a rich, healthy rainforest. We spelled out what that environment looks like in Chapter 3. And in the previous chapter, we learned that the microbes living in our mouths live in sophisticated colonies (or biofilms) that help them survive harsh conditions and sequester resources. Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are two dominant phyla in the healthy mouth. And Streptococcus species are a major player in the oral microbiome. All of our oral microbes co-exist within us peacefully, often helping us.

But what happens if this harmonious microbial balance in the mouth is disturbed? The result is dysbiosis. As you learned in Chapter 2, dysbiosis is an imbalance in the normal microbial make-up. Each person has a unique microbial pattern, so there is no definitive “normal” microbial balance. Likewise, there is no definitive dysbiosis pattern. However, researchers have discovered that when the microbiota fall out of balance, it can throw off the whole system and cause unwanted symptoms.

Imbalance in the microbiome can happen in a lot of scenarios. Good bacteria can overgrow and cause problems. “Shady” bacteria, who often hang out in the background, can take their opportunity to overgrow. You can get a true infection, which throws all of your microbiota out of whack. Or your good bacteria might be weak, either due to antibiotics or a poor diet, and they leave you open to infection or overgrowth of bugs who don’t belong there. Oral dysbiosis can cause cavities, bad breath, gingivitis, and periodontal disease. Common causes of dysbiosis include:71, 72

• Antibiotics

• Infection

• Low levels of good bacteria

• Low fiber/poor diet

• Medications

• Poor saliva flow (dry mouth)

• Sugar

• Weakened immune system

The Microbial Ecology of Cavities

Cavities are the break-down of teeth due to acids made by bacteria. Cavities are little holes in the hard surface of the tooth and can affect the crown or the root. When cavities reach the pulp of the teeth, which houses nerves and blood supply, a root canal may be needed.

One in three Americans has untreated tooth decay and the vast majority have some form of gum disease.73 Cavities cause toothache, tooth sensitivity, holes or pits in teeth, pain when eating or drinking, and stains on the surface of the tooth.

Periodontal disease and cavities are the most common oral diseases of humankind.74

Until recently, a single bacterium was thought to cause cavities: the infamous Streptococcus mutans (or S. mutans, for short). However, scientific discoveries have taught us that it is not one single bug causing the problem, but instead an overall shift in the oral microecology that sets the stage for cavities.

In a healthy mouth, Streptococcus and Lactobacilli bacteria are the major players. These normal, harmless forms of Streptococcus make up 95 percent of dental plaque: Streptococcus sanguinis, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus mitis. (Remember, dental plaque is bacteria on the teeth.) Meanwhile, the “bad bug” S. mutans is only found in 2 percent of the bacterial biofilms in a healthy mouth.75 In this scenario, notice that the good bugs are keeping the bad bug at bay. S. mutans is present, but harmless.

A disruption of the bacteria that live on your teeth can lead to dental cavities.

However, if you aren’t keeping up with your dental hygiene, if you’re eating sugar, and if your saliva isn’t flowing well, it increases acid in your mouth, which sets off a chain of events that disrupts the bacteria that live on your teeth and causes cavities. As the acid in the mouth increases, it primes the environment for making cavities. The good bugs start to die off. S. mutans starts to feel more comfortable and spreads its wings. It can then take over and bring some friends. Streptococcus sobrinus, Bifidobacteria, Candida (yeast), Actinomyces, and Lactobacillus start to move in and take over, too, crowding out the healthy bacteria of the past.76 Candida is high in cavity dysbiosis, and S. mutans and Candida seem to cooperate and help each other to create cavities.77 As these new bugs take over, they promote a whole new microbiotic regime that allows only a few certain bugs to thrive and kills off the masses of good bugs that were protective. Over time, the community of microbes changes and matures, and does more damage to the tooth. Cavities get worse. The bacteria that live in the cavity are very different from the bacteria living elsewhere in the healthy mouth; this community is even under study by scientists because cavities have a microbiome of their own.78 See the chart on page 86 for a list of microbes involved in cavities, gingivitis, periodontal disease, and more.

This is a very important concept and one that I hope you will remember when you walk away from this book. It is not a single, solitary bug that is wreaking total havoc. It is usually the microecology that has been disturbed and is therefore leaving you (the host) vulnerable to disease. Some healthcare practitioners call the microecology the “terrain”: If the host’s terrain is unhealthy or damaged, then a single pathogen can cause major trouble. But if the terrain is healthy, has lots of diverse microbiota who are living in harmony with you, and has a strong barrier, then you are unlikely to have any trouble—even though bad bugs may be hanging around. They just can’t get their foot in the door to cause any real problems because the good bugs never give them an opportunity.

Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus are usually detected in the oral microbiome when someone has cavities. However, in one research study of teenagers who had cavities, 15 to 30 percent had no S. mutans. That’s because other acid-producing oral bacteria can also cause cavities, not just S. mutans. These include Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, and non-mutans Streptococci and Actinomyces species.79 For this reason, dietary changes like cutting out sugar and reducing acid can be among the most powerful ways to control your oral microbiome (check out Chapter 9 for more details).

A three-year-old boy, Grayson, had terrible cavities. His mother took him to Dr. Donna Ruiz, desperately seeking alternatives. Grayson’s dentist was recommending that he have a “pulpectomy” under general anesthesia. A pulpectomy is a root canal therapy that removes all of the tissue inside the tooth. It’s usually recommended when infection has worked its way throughout the pulp and into the root canal system.

At age two, Grayson already had many cavities. Almost every tooth on the top half of his mouth had extensive tooth decay. His parents had food sensitivities so Grayson was already on a gluten-free, sugar-free, dairy-free, and nut-free diet. His mother also said Grayson had some behavioral issues and threw tantrums easily, even with normal challenges. Grayson had nutritional issues since birth and had colic, thrush, and diaper rash while a baby.

Dr. Ruiz did testing and designed a comprehensive treatment to heal Grayson’s mouth. She tried to shift Grayson’s oral microbiome using a probiotic toothpaste (PerioBiotic, by Designs for Health), the oral bacteria Streptococcus salivarius (ProbioMax DDS from Xymogen), and a children’s chewable probiotic (UltraFlora Chew by Metagenics). She had him do a tea tree solution oral rinse to lower bacteria in the mouth. Dr. Ruiz tested and restored some of his nutrients like vitamin D and B vitamins. She built up his immune system and gave him homeopathic medications to help strengthen his teeth and bones. She recommended that Grayson use xylitol as a sweetener and eat more plums since those could inhibit S. mutans, the bacteria commonly present in cavities.

The treatment totally arrested Grayson’s tooth decay. It fixed his bad teeth. He didn’t have to get the pulpectomy. Even his behavioral issues improved. Grayson was doing so much better that he no longer needed treatment. When he came back for treatment one year later, it wasn’t for cavities. It was because his behavioral issues were cropping up again.

If you are like me, you’ve been told that sugar is bad for your teeth a million times. But do you know why? When you eat sugar, you are feeding bacteria in your mouth. Bacteria break down sugar and carbohydrates and produce acids. Acid helps set the stage for cavities. As things get more acidic in the mouth, it encourages even more acid-loving bacteria to climb on board.80 What do they do? Make more acid!

In Chapter 3, we discussed how incredibly hard and tough teeth are, but they are no match for a high-acid environment and a bunch of acid-producing bacteria. When high levels of acid damage the enamel (the protective, hard layer on the teeth), the tooth breaks down and is vulnerable to further attack from bacteria. Sugary and acidic soft drinks are also an archnemesis of healthy teeth.81 Sugar destroys teeth, but with the help of oral bacteria.

The oral microbiota is stable and in harmony with the host, unless disturbed by medication, disease, low pH, or significant changes in diet.82

Gingivitis and Periodontal Disease

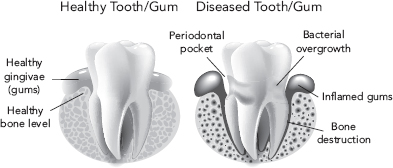

One out of two people in the United States has a history of gingivitis. Its more advanced form, periodontitis, affects nearly 50 percent of people over the age of 30.83 Periodontal disease, which includes gingivitis and periodontitis, is caused by dysbiosis of the oral microbiome and the immune system’s reaction to it. However, if bacterial biofilms (a.k.a. plaque) under the gumline grow out of control, the immune system launches chemical and biological warfare against the microbes that have gotten out of control. It is similar to lighting a fire in the gums. It’s all well and good if this chemical and biological fire effectively kills the unwanted bacteria. But if it doesn’t work, what do you think is the result? Periodontitis. Sadly, the unchecked inflammation destroys gums, eats away at bone, strips the ligaments that hold the teeth in place, and eventually the tooth loosens and falls out. As the bone and gums that used to surround and hold the tooth snugly break down, something called a “periodontal pocket” opens up next to the tooth, which fills with even more bacterial biofilms. Bad news.

Periodontal disease doesn’t just harm the mouth—it can affect the whole body. Having periodontitis increases your risk of whole-body diseases such as atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), diabetes (blood sugar dysregulation), and cancer. We will talk more about the mind-blowing associations between periodontal disease and a long list of other systemic diseases in Chapter 8.

Periodontal disease is an umbrella term that includes gingivitis and mild, moderate, and severe periodontitis.84 The term comes from the word “periodontium” which refers to the gums (or gingivae), ligaments, and bone that hug and hold each tooth securely in the mouth. If your gums are red, irritated, or bleeding, that is a sign of gingivitis, an early form of periodontal disease that causes swollen, puffy, receding, sometimes tender gums. It means that your immune system is not happy and is trying to attack your oral microbiota. If gingivitis goes untreated, it can worsen to periodontitis, which damages the gums, bone, and even causes tooth loss, as described previously.

Figure 6.2: Periodontal disease compared to healthy gums. The body launches an immune attack on overgrown bacterial communities, which destroys gum and bone tissue. The resulting “pocket” fills with more bacteria, worsening the inflammation and further damaging the gums and bone, and can eventually lead to tooth loss.

In the 1600s, “teeth” was listed as a leading cause of death by the London (England) Bills of Mortality. Dental abscess was still a leading cause of death even 200 years ago.85

The great news about gingivitis: It is easy to treat! Regular flossing and brushing and dental cleanings can help reduce the bacterial overgrowth on the teeth, turn off the immune system attack, and heal and soothe the gums. If you have periodontal disease, see a dentist and a periodontist you trust for further treatment. Cavities, gingivitis, and periodontal disease can all be traced back to disturbances in your oral microbiome, so treatments to rebalance the microbiome can turn around these conditions. Avoid sugar and packaged foods (a.k.a. refined carbohydrates) like the plague, eat more vegetables and fiber, use chewable probiotics or probiotic toothpaste, take high doses of oral probiotics (50 million CFU/day or more), and review the additional Oral Microbiome Solutions in Chapter 9 to put a cap on bacterial overgrowth in the mouth.

Everyone complains of bad breath once in a while. But persistent bad breath is a whole other issue. Although it isn’t dangerous, it is a sign of oral disease or imbalance. Bad breath is commonly caused by oral bacterial action on food particles. When a person slacks off on brushing and flossing and visiting the dentist, microbes build up on the teeth and tongue. These bacteria are thrilled to inhabit the mouth, where there is a constant stream of yummy food. But when our oral microbes eat, they make waste products, including gases. Certain bacterial species make characteristic by-products that stink. If those bugs overgrow in the mouth, it can cause bad breath. Gingivitis and periodontal disease are characterized by microbial overgrowth and inflammation and can also cause varying degrees of bad breath.86

Remember in Chapter 3 when we talked about how a regular flow of saliva keeps the mouth healthy? Saliva cleanses the mouth and keeps the microbiota in check. If you have a dry mouth, it can lead to dysbiosis in the mouth and bad breath. Revisit your dental hygiene (brushing, flossing, and dental cleanings) to get a handle on microbial dysbiosis and bad breath. Remember to brush your tongue, which can hold leftover food particles and lots of microbiota.

The most obvious cause of bad breath is right there in the mouth. However, if you have good oral health, then bad breath might be coming from dysbiosis or disease in the sinuses, throat, lungs, or even the gastrointestinal tract. Bad breath is occasionally a symptom of a systemic disease that might be more serious.87

Toxic By-products of Bad Bacteria

Just like us, bacteria eat and make waste products. As we mentioned earlier in this chapter, bacteria can make harmful levels of acid in the mouth, causing cavities. Plaque bacteria can make chemicals like hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, enzymes, and proteins that trigger the inflammatory response. In moderation, the inflammatory response to these toxic by-products is effective. If the inflammatory response spirals out of control, it is dangerous and can cause periodontal disease or worse.88

Some bacterial by-products are extremely poisonous for us. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a particularly toxic component of a gram-negative bacteria’s cell wall. It is infamous for triggering serious inflammation in the host and can even cause life-threatening conditions from bacterial infections. When it binds to immune cells, they get vicious, unleashing biological warfare to eliminate the threat. LPS gets such a huge rise from the immune system that researchers even use LPS in experimental models of inflammation.

Take Control of Your Oral Microbiome

Dysbiosis of the mouth is a serious affair, but it can be treated. Regular, long-term dental care can change your oral microbiota and your chances of cavities, gum disease, and bad breath.89 Your diet, when low in sugar and refined carbohydrates, can encourage a healthier microbiome. Probiotics can reduce S. mutans and reduce cavities.90 You can review these and other oral microbiome solutions that will help you get in the driver’s seat, take control of your oral microbiome, and reduce the risk of oral diseases in Chapter 9.

If you are swallowing 140 billion bacterial cells every day, what would this mean for the mouth’s downstream counterpart, the gastrointestinal tract? Dysbiosis in the mouth could take a ride on the waterslide and dive into the stomach, small intestine, or large intestine.

The mouth and the gut are kissing cousins with a shared architecture, immune network, and mucosal barrier. Every time you swallow, you are seeding your gastrointestinal tract with the bacteria, fungi, and viruses from your mouth—140 billion per day, to be exact. This means that in terms of the gut microbiome alone, the mouth is a major contributor to what is happening in the gut. In fact, researchers have shown that there is a 45 percent overlap in the microbes from the mouth and the gut, proving how closely related these two microbiomes are. There is more bacterial diversity in the gut and oral microbiomes than anywhere else in the body. Disease in the mouth can therefore be mirrored in the gut, and I would venture to say that you must have a healthy oral microbiome in order to have a healthy gut microbiome.

But that isn’t all. Bacterial dysbiosis in the mouth can end up outside of the GI tract, too. Remember that you will find blood vessels and nerves at the center of each tooth, called the pulp. Suffice it to say that each and every tooth has access to the bloodstream. So, if there is dysbiosis of bacteria on the teeth, under the gums, inside the teeth, or anywhere in the mouth, it can effectively reach the bloodstream and use it to travel to far-off sites in the body. In the case of a root canal infection, which is an infection or dysbiosis of the pulp of the tooth, those bacteria could hitch a ride on the blood superhighway and eventually land in a knee joint or even in the heart. Likewise, the inflammation from gingivitis and periodontal disease can slide right into the bloodstream, delivering toxic chemicals to other parts of the body.

Some tortures are physical

And some are mental,

But the one that is both Is dental.

—Ogden Nash, American humorist

The oral cavity is intimately linked to systemic circulation. This is a fascinating topic called the oral-systemic connection that thrills experts and consumers alike and is the topic of the next chapters. So, read on for something that will blow your mind: how the mouth can influence total-body health.

Commensal Bacteria or Pathogen?

Certain periodontal pathogens are uniquely able to create disease, evade the immune system defenses, penetrate the tissues, and activate inflammation and tissue destruction.91 Three species of bacteria, referred to as the red complex, are believed to be involved in gum disease: Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, and Treponema denticola. Porphyromonas gingivalis in particular has been historically believed to be the cause of periodontal disease because it activates inflammation and bone loss.92 We will be talking about P. gingivalis a lot in Chapter 8, especially when we talk about periodontal pathogens that have been found in heart disease plaques and rheumatoid arthritis joints. Candida and oral viruses have also been implicated in periodontal dysbiosis.93

There is a fine line between commensal organisms and pathogens in the oral microbiome. Healthy individuals from the Human Microbiome Project were found to commonly carry oral pathogens, albeit at low levels. In the mouths of many of the study subjects, scientists found pathogenic organisms that can cause periodontal and root canal infections, cavities, periodontitis, pneumonia, strep throat, scarlet fever, meningitis, blood infections, and ear and sinus infections. Yet all of these people were completely healthy. The high prevalence of these microbes in healthy people led scientists to conclude that they were actually commensal organisms and would be involved in disease only when there was oral dysbiosis.94

For a full list of microbes, see “Oral Microbes Involved in Disease” on page 86.

Porphyromonas gingivalis and Streptococcus mutans are present when there is dysbiosis and disease in the mouth. But P. gingivalis can also be a normal, commensal bacteria because it is present in the oral microbiomes of people who are perfectly healthy.95 Likewise, S. mutans, the infamous microbial cause of cavities, isn’t always present in people with cavities.96 Even in populations who have excellent oral hygiene care, still 1 in 5 people gets cavities.

Obviously, S. mutans isn’t always the single cause of cavities and P. gingivalis isn’t the single cause of gum disease. There is a variety of bacteria involved in periodontal disease and cavities. Periodontal disease is suggestive of a bigger problem: a dysbiosis of the oral microbiota and an aberrant immune response to them. It is an overall shift in the microbial ecology in the mouth that allows certain microbes to rise to power and do damage. A healthy oral microbiome prevents this from happening.

An interview with functional dentist Dr. Mary Ellen Chalmers taught me that doing everything “right” to prevent cavities doesn’t work for everyone. There are people who do everything they should do, like eating a healthy diet, brushing, flossing, and seeing the dentist regularly, but they still get cavities. There are people who eat a lot of sugar and simple carbs, don’t brush regularly, and don’t floss, and they don’t get cavities! Dentists can’t always explain this. Oral disease doesn’t just depend on your oral hygiene and your oral microbiome. An interplay of genetics, environment, microbes, immune system, and maybe even blind luck determine whether you are prone to cavities or not (see more about this in Chapter 10).

Takeaways

• Cavities, gingivitis, periodontal disease, and bad breath are examples of oral dysbiosis.

• Sugar and packaged foods (those containing refined carbohydrates) promote dysbiosis of the oral microbiome and oral diseases.

• It is no longer believed that one microbe single-handedly causes disease; instead, a shift in the microbial ecology allows harmful bacteria to rise to power.

• Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by microbial imbalance and excessive immune reactions.

• Oral dysbiosis may arise when various interrelated factors are not kept in balance: diet, salivary flow, pH environment, immune defenses, and microbial balance.