The Tectia server can use external programs, known as plugins , for flexible handling of tasks like changing passwords [5.4.2.3], driving the process for keyboard-interactive authentication [5.4.5.2], or performing arbitrary checks for access control. [5.5.6] We'll demonstrate how to use plugins with several examples:

Handling expired passwords

Extending keyboard-interactive authentication

Authorization

Remember our discussion of expired passwords in Chapter 5? [5.4.2.3] We showed how Tectia's SSH server can detect an expired password at authentication time, and prompt the user to change it:

$ ssh server.example.com

rebecca's password: < ... old, expired password ... >< ... old, expired password, again ... >< ... new password ... >< ... new password, again ... >The SSH server accomplishes this by calling either the system

password-change program (e.g., passwd) or an

alternative program specified by the PasswdPath configuration keyword. This

technique, which is the default, uses a forced command to change the

password. This method is conceptually simple but has several

drawbacks:

No explicit indication is given that the password is expired, or that a forced command is being used. Of course, the prompts from the password-change program are a clue, but a user might be (understandably!) suspicious about prompts that demand passwords for no apparent reason. Furthermore, if the user intends to run some other command with similar prompts for unrelated passwords, she might be confused by unexpected interactions with the password-change program.

While it makes sense to ask the user to type his new password twice, to avoid mistakes, it's annoying and unnecessary to require entering the old password twice. This happens because the first old password is sent to the SSH server while the second is demanded by the password-change program, and the server doesn't forward the password.

The connection is closed after the forced command finishes, whether the password change was successful or not, and the user must then repeat the authentication with a separate ssh command, which in turn requires entering the new password yet again.

The username isn't passed from the SSH server to the password-change program, since most programs only allow non-root users to change their own passwords, and some allow only root to specify a username on the command line. If several usernames use the same numerical user ID (a bad practice, but it does occur), then only the first user's password is changed.

Fortunately, the SSH-2 protocol provides a better mechanism for

changing passwords during authentication, and Tectia allows a separate

program, known as a password-change plugin, to

manage the process. This mode of operation is enabled by the AuthPassword.ChangePlugin keyword:

# Tectia

AuthPassword.ChangePlugin /usr/local/libexec/ssh-passwd-pluginHere's an example of a password change using the plugin:

$ ssh server.example.com

rebecca's password: < ... old, expired password ... >< ... new password ... >< ... new password, again ... >As before, the client collects the user's password and sends it to the server, which verifies it. When the server discovers that the password is expired, it sends an expiration message back to the client, which informs the user about what's happening. The client then prompts for the new password and sends it to the server, which passes all of the necessary information (the username, plus the old and new passwords) to the plugin program to change the password. If the plugin tells the server that the change was successful, then the server considers authentication complete, and continues. Otherwise (if the change failed), the server tells the client, which can prompt the user to try again, without starting a new session or using a separate ssh command. Much better!

The plugin program runs with the privileges of the user, not those of the server. If the plugin program isn't found or can't be run for some other reason, then password changes always fail.

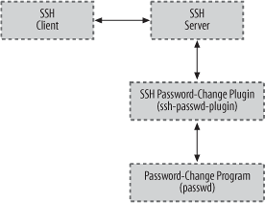

Tectia includes a generic plugin program, ssh-passwd-plugin, in most binary distributions.[161] ssh-passwd-plugin runs the system's password-change program within a pseudo-terminal, effectively acting as an intermediary between the SSH server and the program that actually performs the password change, as shown in Figure 11-14.

The actions of ssh-passwd-plugin are controlled by the configuration file /etc/ssh2/plugin/passwd_config, which uses the same syntax as other server configuration files.[162] [5.2.1] The configuration file is read every time the plugin runs.

The ssh-passwd-plugin configuration

consists of a series of Request

and Response (or FinalResponse) keywords, which should

occur in pairs:

# Tectia: /etc/ssh2/plugin/passwd_config with egrep regex syntax

Request "\(current\) UNIX password:"

Response $old_password$\n

Request "New password:"

Response $new_password$\n

Request "Retype new password:"

FinalResponse $new_password$\nThis example describes the behavior of the password-change program used for the preceding forced-command example.

Request values are regular

expressions that match output from the password-change

program.

Warning

Quotes are required if the Request pattern ends with a colon

(:) character, to prevent

misinterpretation as a section pattern line [5.2.1], or if the pattern

ends in whitespace, which is normally discarded. It's a good idea

always to quote Request

values.

Response values are strings

that are sent to the password-change program when the preceding

Request value matches. These strings can contain the following

special tokens:

$user_name$$old_password$$new_password$

which are replaced by the values supplied by the client and

forwarded via the server. Use $$

in the string to send a single $

character, or \n to send a

newline.[163]

The last expected response is indicated by the FinalResponse keyword; its value uses the

same format as Response.

Response strings can also

be one of the following special result values:

- $ERROR_DISPLAY

Send the match for the preceding

Requestvalue back to the client via the server and terminate, indicating that the password change failed.- $ERROR_LOG

The same, but only send the match to the server for logging, not to the client.

- $SUCCESS

Indicate that the password change was completed successfully whenever the preceding

Requestvalue matches.

Tip

The special result values for the response strings have a

$ character at the beginning

only, not at the end, unlike the tokens for the username and

passwords.

The result values are case-insensitive, but it's best to use uppercase to distinguish them from the tokens, which must be lowercase.

Unrecognized output from the password-change program is ignored, so expected error messages should be matched and sent to the user:

# Tectia: /etc/ssh2/plugin/passwd_config

Request "BAD PASSWORD: it's WAY too short"

Response $ERROR_DISPLAYIf error messages contain sensitive information, or aren't interesting for users, then they can be logged instead:

# Tectia: /etc/ssh2/plugin/passwd_config

Request "internal error: database corruption"

Response $ERROR_LOGSimilarly, if the password-change program prints a success message, ssh-passwd-plugin can use it to determine that the operation went well:

# Tectia: /etc/ssh2/plugin/passwd_config

Request "all authentication tokens updated successfully"

Response $SUCCESSSome password-change programs succeed silently, however. In

this case, ssh-passwd-plugin can examine the

exit status returned by the password-change program to detect

success, using the GetSuccessFromExit keyword:

# Tectia: /etc/ssh2/plugin/passwd_config

GetSuccessFromExit yesA zero exit status indicates success. The default value for

GetSuccessFromExit is no, meaning that the exit status is

ignored. Unless you are using a broken program that returns random

exit status values, we recommend configuring

ssh-passwd-plugin to enable GetSuccessFromExit.

By default, ssh-passwd-plugin waits up to

four seconds for output from the password-change program. This can

be changed using the DataTimeout

keyword:

# Tectia: /etc/ssh2/plugin/passwd_config

DataTimeout 10The value is a number of seconds; time units are not recognized.

An alternate password-change program can be specified using

the PasswdPath keyword:

# Tectia: /etc/ssh2/plugin/passwd_config

PasswdPath /usr/local/bin/goodpasswd $user_name$This differs from the PasswdPath keyword in the server

configuration file in that ssh-passwd-plugin

expands tokens, as shown for the username.

Warning

The server is supposed to supply the value for its PasswdPath keyword to the plugin as a

default; the PasswdPath keyword

in ssh-passwd-plugin's own configuration file

would then override the server's value. However, this isn't

actually done (as of Tectia Version 4.1), so it's necessary for

ssh-passwd-plugin to always specify the

PasswdPath if the value needs

to be changed.

Debugging the interactions between ssh-passwd-plugin and the password-change program can be challenging. Because unrecognized output is simply discarded, the usual symptom of mismatches in the configuration file is the error:

Timeout when waiting for exit status.

ssh-passwd-plugin recognizes the

-d or --debug command-line

options, but these are not passed automatically from the

sshd command line to the

ssh-passwd-plugin command line, so it's

necessary to specify the option in the value for the AuthPassword.ChangePlugin keyword. Use the

GenPasswdPlugin module and a high

debug level to see all of the data exchanged between the

programs:

# Tectia

AuthPassword.ChangePlugin /usr/local/libexec/ssh-passwd-plugin -d GenPasswdPlugin=9 2>> /tmp/plugin.dbgAlternately, ssh-passwd-plugin uses the

value of the environment variable SSH_DEBUG_LEVEL, which can be set before

starting the server. If both the environment variable and the

command-line option are used, the option wins.

Debug output is written to the standard error stream, but the

server runs the plugin using the (Bourne) shell, so we append the

output to a file with the 2>> redirection. This is needed when

the SSH server runs in the background as a daemon, because stderr is

discarded. If the server is also running in debug mode, so stderr is

already being sent to some convenient location, then the 2>> redirection can be omitted, and

ssh-passwd-plugin will send its debug output to

the same place as the server.

All Tectia plugins use a simple, line-oriented

protocol designed to facilitate scripting. Here we discuss some of

the common elements of the protocol, and illustrate them by writing

a Perl package, Net::SSH::Tectia::Plugin, containing handy

functions that we'll use in our example plugin scripts. We chose the

Net::SSH prefix to correspond

with other Perl packages for SSH available on CPAN.

As we discuss each type of plugin, we'll provide examples written in Perl, but any language can be used; in fact, the Tectia source distribution includes some sample plugins written as Bourne shell scripts.

The package starts with the usual preliminaries, identifying the names of the exported functions, and a version number for the package:

package Net::SSH::Tectia::Plugin;

use strict;

BEGIN {

use Exporter;

use vars qw(@ISA @EXPORT $VERSION);

@ISA = qw(Exporter);

@EXPORT = qw(

&ssh_plugin_recv

&ssh_plugin_params

&ssh_plugin_send

&ssh_plugin_success

&ssh_plugin_failure

);

$VERSION = 1.01;

}

1; # return true for importThe server sends lists of (key,value) pairs to the plugin, which reads them on its standard input. Each pair is formatted as "key:value" on a separate line, and the end of the list is marked by a line of the form "end_of_words" where "words" describes the kind of information in the list.

Keys and the end marker are case-insensitive. The plugin is supposed to ignore keys that it does not understand, to allow for future extensions to the protocol. If the end marker is not seen, the plugin must fail, as described shortly.

The ssh_plugin_recv

function conveniently reads information lists from the

server:

# Read a list of "key:value\n" pairs from the server.

# Usage: &ssh_plugin_recv($words), where "end_of_$words\n" (case-insensitive)

# marks the end of the list.

# Returns ("end_of_$words", key1, value1, key2, value2, ...) on success,

# or an empty list on failure.

sub ssh_plugin_recv

{

my $words = shift;

my @pairs; # accumulated list of (key, value) pairs

# read each line from the server

while (<>) {

chomp; # discard newlines

# return the end marker and list of pairs if the end marker is seen

return ($_, @pairs) if /^end_of_$words$/i; # case-insensitive

my ($key, $value) = split(':', $_, 2);

$key = lc($key); # keys are case-insensitive: translate to lowercase

push(@pairs, $key, $value);

}

return undef; # return an empty list if no end marker was seen

}All plugins start by reading a list of parameters from the server, so we provide a shorthand function for that:

# Read a list of parameters from the server.

sub ssh_plugin_params { &ssh_plugin_recv("params"); }The plugin sends messages back to the server by writing single-word tokens or "key:value" pairs, each on a separate line, to the plugin's standard output stream:

# Send a message to the server.

# Usage: &ssh_plugin_send($token) to send "$token\n"

# or &ssh_plugin_send($key, $value) to send "$key:$value\n".

sub ssh_plugin_send

{

local $| = 1; # flush data to pipe after every write, to avoid buffering

print join(':', @_), "\n";

}Special messages are used to indicate success or failure of the operation performed by the plugin:

# Send success or failure messages to the server.

sub ssh_plugin_success { &ssh_plugin_send("success"); }

sub ssh_plugin_failure { &ssh_plugin_send("failure"); }The server doesn't examine the exit status values returned by the plugin; it only notices success or failure messages. Nevertheless, it's good form to return a zero or nonzero exit status value for success or failure, respectively.

Now that we've created the Net::SSH::Tectia::Plugin package, let's

write our own password-change plugin script with it. This might be

useful if passwords are stored in some kind of nonstandard external

database, and are changed by a mechanism other than a traditional

passwd program, so that

ssh-passwd-plugin can't be used.

The plugin starts by reading parameters from the server, which include the username as well as old and new passwords supplied by the client:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

use strict;

use Net::SSH::Tectia::Plugin;

my ($end, %params) = &ssh_plugin_params();The keys and values for the parameters are stored in the

%params hash for easy

retrieval.

The plugin sends error messages back to the server using

error_msg and error_log keys, which correspond to the

$ERROR_DISPLAY and $ERROR_LOG special response values used by

ssh-passwd-plugin:

sub ssh_plugin_error_msg { &ssh_plugin_send("error_msg", @_); }

sub ssh_plugin_error_log { &ssh_plugin_send("error_log", @_); }It's a good idea for the plugin to check for and log protocol violations:

sub ssh_plugin_die

{

&ssh_plugin_error_log(@_);

&ssh_plugin_failure();

exit(2);

}

&ssh_plugin_die("missing end marker for params") unless defined($end);

&ssh_plugin_die("missing user_name") unless exists($params{"user_name"});

&ssh_plugin_die("missing old_password") unless exists($params{"old_password"});

&ssh_plugin_die("missing new_password") unless exists($params{"new_password"});Finally, the plugin changes the password, in our example using

a change_password function that

updates the database, and indicates the result of the operation to

the server, which forwards it back to the client:

my $result = &change_password($params{"user_name"},

$params{"old_password"},

$params{"new_password"});

if ($result eq "success") {

&ssh_plugin_success();

exit(0);

} else {

&ssh_plugin_error_msg($result); # tell the client why it failed

&ssh_plugin_failure();

exit(1);

}The complete code for our plugin is shown in Example 11-1.

Example 11-1. Our password-change plugin

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

use strict;

use Net::SSH::Tectia::Plugin;

my ($end, %params) = &ssh_plugin_params();

sub ssh_plugin_error_msg { &ssh_plugin_send("error_msg", @_); }

sub ssh_plugin_error_log { &ssh_plugin_send("error_log", @_); }

sub ssh_plugin_die

{

&ssh_plugin_die("missing end marker for params") unless defined($end);

&ssh_plugin_die("missing user_name") unless exists($params{"user_name"});

&ssh_plugin_die("missing old_password") unless exists($params{"old_password"});

&ssh_plugin_die("missing new_password") unless exists($params{"new_password"});

my $result = &change_password($params{"user_name"},

$params{"old_password"},

$params{"new_password"});

if ($result eq "success") {

&ssh_plugin_success();

exit(0);

} else {

&ssh_plugin_error_msg($result); # tell the client why it failed

&ssh_plugin_failure();

exit(1);

}The server is supposed to pass the value for its PasswdPath keyword to the plugin using the

SSH2_PASSWD_PATH environment

variable, which could be accessed as:

my $passwd = $ENV{"SSH2_PASSWD_PATH"};However, the server doesn't currently do this (as of Tectia Version 4.1).

Keyboard-interactive authentication, including one-time

passwords and challenge-response authentication, was covered in Chapter 5. [5.4.5] Here we'll show how to

construct a plugin with our Net::SSH::Tectia::Plugin package to hook

into keyboard-interactive authentication. It will prompt the user for

some personal information, which is recorded (perhaps at account

creation time) in a database.[164]

The plugin starts by reading parameters from the server:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

use strict;

use Net::SSH::Tectia::Plugin;

sub ssh_plugin_die

{

&ssh_plugin_failure();

exit(2);

}

my ($end_params, %params) = &ssh_plugin_params();

&ssh_plugin_die() unless defined($end_params);The plugin checks for protocol violations, such as a missing end

marker for the parameters, and indicates failure using the ssh_plugin_die function.

The parameters are stored in the %params hash for easy retrieval. Keys

supplied by the server include:

- user_name

The username requested by the client (to be used on the server).

- host_ip

The local (server) host address.

- host_name

The local (server) hostname.

- remote_user_name

The remote (client) username. This is sent only if it is known by the server from an earlier hostbased authentication.

- remote_host_ip

The remote (client) host address.

- remote_host_name

The remote (client) hostname.

Warning

The RFC.kbdint_plugin_protocol file in the

source distribution only defines the parameter's user_name, remote_host_ip, and remote_host_name. The Tectia plugin

protocol requires plugins to ignore unrecognized parameters.

The keyboard-interactive plugin next sends a list of prompts to be displayed by the client:

&ssh_plugin_send("instruction", "Please provide some personal information.");

&ssh_plugin_send("req", "Favorite color: ");

&ssh_plugin_send("req", "Pet's name: ");

&ssh_plugin_send("req_echo", "Do you like chocolate? ");

&ssh_plugin_send("end_of_requests");The optional "instruction" message is used to display introductory information.

Warning

Although the SSH-2 protocol (as described in the IETF SECSH draft) supports newlines in the instruction string, there is no way to send them using the Tectia plugin protocol, which uses newlines as delimiters. If multiple instruction strings are sent, only the last one is used by the server.

Responses collected by the client are not echoed for prompts

specified by req messages. If the

response should be echoed, then the req_echo message can be used instead.

The list of prompts ends with the end_of_requests marker. When the server

reads the marker, it sends the list of requests to the client.

After the client collects the replies and sends them back to the server, the server forwards them to the plugin using the same kind of list:

my ($end_replies, @replies) = &ssh_plugin_recv("replies");

&ssh_plugin_die() unless defined($end_replies);The replies are stored in the @replies list as a series of (key,value)

pairs; each reply pair corresponds to a request prompt. We use a list

rather than a hash because the server uses a reply message for each response value, but

the plugin can step through the list to set up a %replies hash for easy retrieval, checking

for and rejecting protocol violations as it does so:

my %replies;

foreach my $reply qw(color petname chocolate) {

my ($key, $value) = splice(@replies, 0, 2);

&ssh_plugin_die() unless defined($key) && $key eq "reply" &&

defined($value);

$replies{$reply} = $value;

}

&ssh_plugin_die() if @replies; # too many repliesFinally, the plugin uses any subset of the parameters and the

replies collected from the user for authentication, in our example

using a verify_personal_info

function, and indicates the result of the operation to the server,

which forwards it back to the client:

my $result = &verify_personal_info($params{"user_name"},

# ... and other params, if relevant ...

$replies{"color"},

$replies{"petname"},

$replies{"chocolate"});

if ($result eq "success") {

&ssh_plugin_success();

exit(0);

} else {

&ssh_plugin_failure();

exit(1);

}Here's an example of keyboard-interactive authentication in action, shown from the client's perspective:

$ ssh server.example.com

Keyboard-interactive:

Plugin authentication

Please provide some personal information.

Favorite color: green < ... not echoed ... >

Pet's name: Elvis < ... not echoed ... >

Do you like chocolate? yes < ... echoed ... >

Authentication successful.

< ... login session begins ... >Of course, a GUI-based SSH client could display the information in a different format.

The plugin can perform additional rounds of request/reply interactions if needed.

For example, if some of the responses were malformed, the plugin

can ask again; in this case, an instruction message is often used to provide

guidance about allowable values:

unless ($replies{"chocolate"} eq "yes" ||

$replies{"chocolate"} eq "no") {

&ssh_plugin_send("instruction", "Please answer \"yes\" or \"no\".");

&ssh_plugin_send("req_echo", "Do you like chocolate? ");

&ssh_plugin_send("end_of_requests");

}Subsequent interactions are sometimes needed to collect follow-up information whose relevance is based on previous responses:

if ($replies{"chocolate"} eq "yes") {

&ssh_plugin_send("instruction", "Tell us more about how you like chocolate!");

&ssh_plugin_send("req", "Light or dark? ");

&ssh_plugin_send("req", "With nuts? ");

&ssh_plugin_send("end_of_requests");

}More realistic examples of additional queries would be prompting to update expired passwords, multistage challenge-response protocols, etc.

Only a single plugin can be specified by the AuthKbdInt.Plugin keyword. If multiple

keyboard-interactive authentication techniques must be supported by

the plugin, then it should ask the user to pick a technique during an

initial round of interactions, and pose follow-up queries for specific

techniques during subsequent rounds.

Tip

To use Tectia's SecurID plugins along with other techniques that are supported by a custom plugin, the custom plugin can be written to forward information between the server and the SecurID plugins, according to the Tectia plugin protocol. An alternative is to recompile the server with built-in support for SecurID, eliminating the need for separate SecurID plugins.

The plugin should not implement its own

retry logic for failed authentications. Instead, it should simply

indicate failure and let the server manage retry attempts, according

to the value for the AuthKbdInt.Retries keyword.

The plugin program must be written carefully, since it runs with all of the privileges of the SSH server (typically root). For example, it's important to treat all data supplied by the user as potentially hostile: consider buffer overruns, special characters used to construct filenames, etc. Perl's "taint mode" is useful for detecting possible security problems.

A more subtle danger is information leakage. For example, it might seem reasonable for a plugin to fail immediately after the initial parameters have been received from the server, if (say) the username is found to be invalid. After all, why ask for more information if the authentication will fail anyway? The problem with this approach is that it allows remote attackers to determine which usernames are valid, without authenticating. A system administrator might notice large numbers of failed authentications in the system logs [5.9], but by then, the damage has already been done.

A better approach is to always collect all information from the user, and make authentication decisions only after this has been done. The design of the prompts can be tricky when later interactions depend on the validity of previous responses. In some cases, it's necessary to use "fake" information so that all of the interactions will seem plausible when early replies are incorrect.

Even timing can be a concern. If authentication is computationally expensive, or requires a measurable amount of time to complete for other reasons, it may be necessary for the plugin to sleep for an equivalent interval when those costly authentication steps are skipped, so an attacker can't tell what's happening.

Next we'll write a plugin, once again using our Net::SSH::Tectia::Plugin package, to perform

external access control. Our plugin will allow guest accounts to log

in from untrusted systems, but only at certain times.[165] We covered external access control in Chapter 5. [5.5.6]

The plugin starts by reading parameters from the server:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

use strict;

use Net::SSH::Tectia::Plugin;

my ($end, %params) = &ssh_plugin_params();

unless (defined($end)) {

&ssh_plugin_failure();

exit(2);

}The plugin checks for protocol violations, such as a missing end marker for the parameters, and indicates failure (causing access to be denied) if any are detected.

The parameters are stored in the %params hash for easy retrieval. The server

supplies the same keys as for keyboard-interactive plugins. [11.7.2]

The program then uses any of the parameters and other information at its disposal to determine if access should be allowed or denied:

my $restrict =

&account_type($params{"user_name"}) eq "guest" &&

&host_trust_level($params{"remote_host_ip"},

$params{"remote_host_name"}) eq "outside" &&

&schedule(time) eq "prime";Our example uses an &account_type function to categorize

usernames, perhaps based on the username itself (like AllowUsers or DenyUsers [5.5.1]) or by looking up

group memberships (like AllowGroups

or DenyGroups [5.5.2]). Similarly, an

&host_trust_level function

classifies remote hosts, based on the address or hostname (like

AllowHosts or DenyHosts [5.5.3]).

External authorization programs are especially useful when

access control decisions must be based on complicated logic or

information that is not understood directly by the Tectia server. For

example, netgroups or other databases could be used by the &account_type or &host_trust_level functions to evaluate

users or hosts, respectively, and other factors such as the time can

be incorporated, in our example by a &schedule function.

Finally, the program indicates success or failure to the server to allow or deny access:

if (! $restrict) {

&ssh_plugin_success();

exit(0);

} else {

&ssh_plugin_failure();

&ssh_plugin_send("error_code", "generic_error");

&ssh_plugin_send("error_msg", "Remote guest logins are not allowed during prime time.");

exit(1);

}The program can send an error code and message to the server to describe failures. The protocol defines only two error codes:

- password_too_old

The user's password has expired.

- generic_error

Some other error occurred.

If the program informs the server about password expiration,

then the server runs the system password-change program (either the

default, or the value for the PasswdPath keyword) as a forced command.

[8.2.3] It does not,

however, run a password-change plugin, because the plugin applies only

to the authentication phase, which has already been completed when the

external authorization program runs.

Warning

In practice, password expiration isn't very useful for

external authorization programs, since the programs don't interact

(even indirectly) with clients, and passwords are really associated

with separate authentication techniques that are performed earlier.

Instead of using the password_too_old error code with an

external authorization program, use a keyboard-interactive plugin

[11.7.2] to flexibly

handle password expiration.

Because that leaves only the generic_error code, the error_code message is itself not very

useful. Perhaps someday the protocol will be extended to define

other, more meaningful error codes, if they are needed to modify

server operation.

The error message is an arbitrary string that explains why access has been denied.

Warning

Unfortunately, the server doesn't currently (as of Tectia V476 Version 4.1) use the error message string for any purpose whatsoever. It isn't forwarded to the client, so it can be displayed by the user, and it isn't even recorded in the system log or mentioned in debug output. [5.9]

It's still a good idea for external authorization programs to send an error message back to the server, however, so that future versions of the server might be able to use it.

The external authorization program should be written carefully, since it runs with all of the privileges of the SSH server (typically root). Perl's "taint mode" is useful for detecting possible security problems.

[161] Alternatively, the ssh-passwd-plugin program can be built from the source distribution.

[162] Including metaconfiguration information.

[163] Newlines are not supplied automatically, so most response

strings will need at least one explicit \n, usually at the end.

[164] See the file RFC.kbdint_plugin_protocol in the Tectia distribution for details, and kbdint_plugin_example.sh for another example implemented as a shell script.

[165] See the file RFC.authorization_program_protocol.