Title of the Book and Role of the Judges

The English title for the book of Judges derives from the Latin (Liber Judicum) titles. The English term implies the notion of persons who adjudicate legal disputes or decide criminal cases. But the Hebrew title of the book (šōpĕṭîm) implies something different. Judg 2:16–17a states, “Then the LORD raised up judges [Hebrew šōpĕṭîm], who saved them out of the hands of these raiders. Yet they would not listen to their judges but prostituted themselves to other gods and worshiped them.”

Thus the judges were to be both “deliverers” or “saviors” of their people from their enemies and “catalysts” or “stimuli” for godly living. Their purpose was not judicial; they were saviors. The first two judges, Othniel (3:9) and Ehud (3:15), are specifically called “deliverers.” Others are described through the use of the verb “save” or “deliver” (Shamgar, 3:31; Gideon, 6:15; 8:22; Tola, 10:1; Jephthah, 12:3; Samson, 13:5). But 2:17 implies that they were also to be spiritual and moral leaders. Therefore, the success of each judge is related to his success in delivering the people and his success in spurring the Israelites to live proper lives before God.

There are two types of judges, usually designated as “major” and “minor” judges. The functional distinctions between the two types should not be too sharply drawn since the differences seem to be due to the author’s choice of whether or not to include and develop the “cycle” in the story.

Author and Date

The author of the book of Judges is unknown. The date of composition is also unknown, but it was probably written during the monarchy (although the precise time is impossible to determine). Some of the stories may have existed in oral or written form at an early stage before the monarchy, but none is attributed to any particular source. The reference in 18:30 to “the time of the captivity of the land” seems to refer to the exile of the northern kingdom (722 BC) and suggests that the final edition of the book, at the earliest, came from this period. However, some scholars understand this to refer to the taking of the ark (see note on 18:30).

Chronology

The period of the judges extends from the death of Joshua to the coronation of Saul, so the book does not cover the entire period of the judges. It leaves out two judges whose stories are found in the book of Samuel: Eli and Samuel (cf. 1 Sam 1–7). Simply adding the lengths of rule of each judge with its preceding oppression gives a total that cannot fit into the time between Joshua and Saul. Therefore, some oppressions and judgeships overlapped. This is to be expected since many (if not all) of the judges were local tribal leaders operating in geographically limited portions of Israel. Since there is no link in the book to the external chronology of the ancient Near East, the degree of overlap is difficult to discern. Thus the precise chronology of the period of the judges is unknown (cf. 1 Sam 12:9–11). This chronology is also dependent on the date of the exodus and conquest; early dates would be 1380–1050 BC; late dates would be ca. 1235–1050 BC (see Introduction to the Old Testament: Chronology/Dating).

In addition, the book’s use of numbers is not always clear. For example, the book may use the number 40 as a round number or figuratively to denote a generation. The first four major judges (Othniel, Ehud, Deborah, Gideon) are credited with 40 years of rest for the land (in the case of Ehud double 40, i.e., 80 [3:30]). The Philistine oppression (13:1) is 40 years. Samson’s judgeship is 20 years (half 40), but mentioned twice (15:20; 16:31). The Canaanite oppression (4:3) is also 20 years.

The book does not include a complete historical presentation of any of the judges. In the case of the so-called minor judges, the writer chooses to give very limited information. For example, “Tola . . . rose to save Israel” (10:1). But from whom? Had Israel done evil in the eyes of the Lord as in other cases? How did Tola “save” Israel? The information is not forthcoming. In addition, there is not a narration about every oppression during the judges’ era. For example, in 10:11–14, the Lord refers to the oppressions of the Israelites by the Egyptians, Amorites, Sidonians, and Maonites. None of these is connected with a story of a judge who delivered the Israelites. The book’s selective presentation is the way the author works his literary artistry and communicates with great clarity his theological message.

Literary Aspects and Message

The book of Judges has three main parts: a double introduction (1:1—3:6), a double conclusion (17:1—21:25), and a main section commonly called the “cycles” section (3:7—16:31). See Outline.

The book has a coherent message concerning the consequences of disobedience to God with the resultant moral degeneration that characterized the history of Israel during this period. In a sense, it describes the degeneracy of Israel, its “Canaanization.” The book is clearly designed to instruct the reader on the consequences of covenantal unfaithfulness to God and his law. Although Israel’s degeneracy directly challenges God’s rule, it cannot undo the Lord’s sovereign kingship.

The book develops Israel’s degeneracy from different perspectives: a historical/military perspective (1:1—2:5) and a religious perspective (2:6—3:6). The cycles section (3:7—16:31) uses the religious perspective traced in the individual lives of the judges themselves. The book’s final section (17:1—21:25) represents both perspectives in which Israel as a nation expresses its fullest point of degeneracy by its corporate actions. While Samson is the climax and moral nadir of the cycles section, the full scope of degeneration is seen in chs. 17–21, which document Israel’s deterioration into idolatry, civil war, and rape sanctioned by the leaders of Israel.

The Double Introduction and Double Conclusion

The double introduction is symmetrical to the double conclusion, framing the “cycles”:

a Foreign wars with failure to apply the law of Deut 7 (ḥērem) (1:1—2:5)

b Difficulties with foreign idols (2:6—3:6)

b´ Difficulties with domestic idols (17:1—18:31)

a´ Domestic wars with misapplication of the law of Deut 7 (ḥērem) (19:1—21:25)

The first introduction (a) is balanced by the second conclusion (a´), and the second introduction (b) is balanced by the first conclusion (b´). On the law of the ban (Hebrew ḥērem), see Introduction to Deuteronomy: Themes and Theology (Holy War); Deut 7 and notes; Deut 20 and notes; Introduction to Joshua: Theological Themes (Genocide?); Josh 6 and notes; see also Theology below.

The double introduction (1:1—3:6) initiates two patterns that create literary expectations for the main “cycles” section. Judg 1:1—2:5 introduces the reader to the pattern of Israel’s increasing failure to drive out the Canaanites—a pattern that will be mirrored in the degeneration of the “cycles” section. It also reveals the geographic sequence pattern of Judah to Dan reflected in the cycles (Othniel to Samson). Judg 2:6—3:6 introduces the reader to a second pattern, the all-important “cycles” pattern, the very framework of each of the six major cycles (see The Cycles Section).

The double conclusion (17:1—21:25) is not only linked with the double introduction (1:1—3:6), but it is itself unified by the four-time repetition of a distinctive refrain: “In those days Israel had no king; everyone did as they saw fit.” The refrain occurs twice in full (at the beginning and end of the double conclusion: 17:6; 21:25) and twice with an ellipsis of the refrain’s second line (in the middle of the double conclusion: 18:1; 19:1). This forms a concentric (chiastic) pattern—a (17:6)—b (18:1) / b´ (19:1)—a´ 21:25—that reinforces the theological significance of the refrain (see Theology).

The Cycles Section

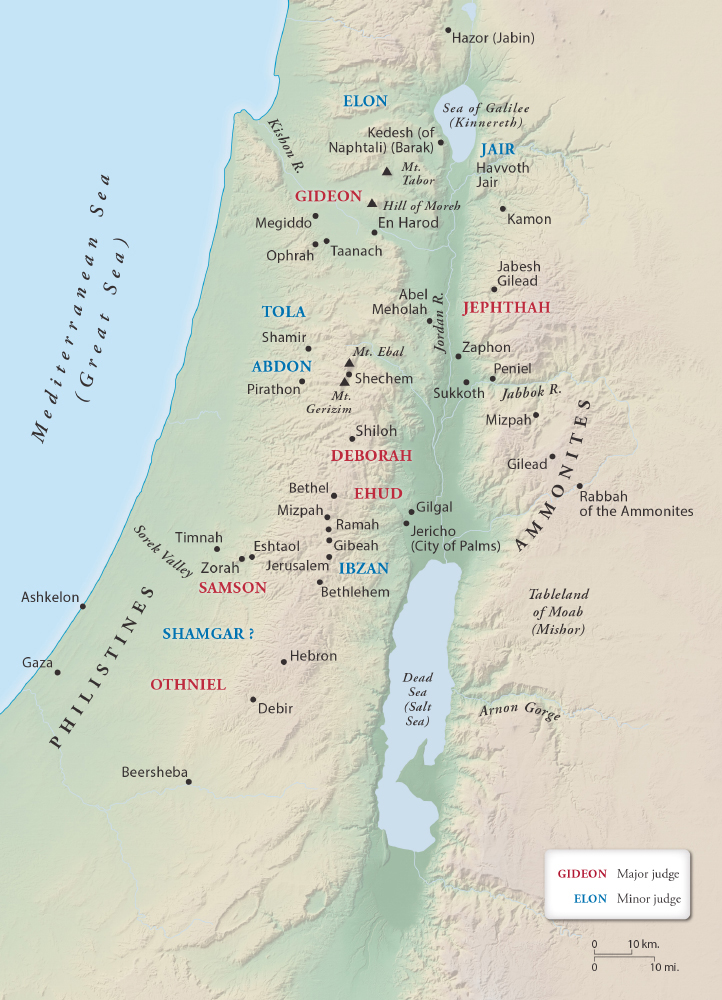

The “cycles” section (3:7—16:31) contains six major judge cycles: Othniel (3:7–11), Ehud (3:12–30), Deborah and Barak (4:1—5:31), Gideon and Abimelek (6:1—9:57), Jephthah (10:6—12:7), and Samson (13:1—16:31). In the two center cycles there is a pairing of the judge with another person: Deborah (the prophetess, see note on 4:4) and Barak (the judge); Gideon (the judge) and Abimelek (the “king”) (see notes on 6:1—9:57; 8:33—9:57). There are also six minor judge mini-narratives: Shamgar (3:31), Tola (10:1–2), Jair (10:3–5), Ibzan (12:8–10), Elon (12:11–12), and Abdon (12:13–15). These are interspersed among the major judge stories, occurring in a 1–2–3 sequence: (1) Shamgar, (2) Tola and Jair, (3) Ibzan, Elon, and Abdon.

The six major judge cycles are built around the following components (see generally ch. 2):

1. Israel does evil in the eyes of the Lord.

2. The Lord gives/sells them into the hands of oppressors.

3. Israel serves the oppressor for x years.

4. Israel cries out to the Lord.

5. The Lord raises up a deliverer (i.e., a judge).

6. The Spirit of the Lord is upon the deliverer.

7. The oppressor is subdued.

8. The land has peace (“rest”) for x years.

It is very important to read the six major judge cycles (3:7–11; 3:12–30; 4:1—5:31; 6:1—9:57; 10:6—12:7; 13:1—16:31) within the larger narrative complex of 3:7—16:31 and to take into account the double introduction’s paradigms that initiate the patterns of Israel’s moral degeneration.

The cycle components vary in such a way as to contribute to the book’s message. With each major judge, the cycle unravels. In turn, this unraveling reinforces the message of moral deterioration. The initial cycle (3:7–11), where all the components are present, portrays Othniel, who captured Debir by trusting in God (1:11–13), as the ideal judge: the text mentions no character flaws and calls him “a deliverer” (3:9). Ehud is also a “deliverer” (3:15) whom God raised up (3:12–30). But the Deborah-Barak cycle does not explicitly identify the “deliverer,” and Barak’s initial refusal to go reveals a problem. The people do not remain faithful to Yahweh during Gideon’s lifetime; rather, Gideon’s own construction of a golden ephod (that is worshiped as an idol) becomes a snare both to him and to his family. By the time of Jephthah, the list of Israel’s apostasies is considerably expanded (10:6), and when the people first cry out, Yahweh (“the LORD”) refuses to deliver them (10:14). Ironically Jephthah will offer his daughter as a burnt offering. Neither the Jephthah story nor the Samson story depicts the land as regaining peace (“rest”). By the time of Samson, the cycle has almost disappeared: the people of Samson’s time do not even bother to cry to Yahweh, and Samson himself dies in captivity to the oppressor, only beginning the deliverance from the Philistines (see note on 13:5). Samson, who is more interested in loving foreign women than saving Israel, is a man motivated by self-gratification and personal revenge. Thus this unraveling of the cycle climaxes in the degeneracy of the last judge. This does not mean these individuals did not have faith; rather, it means God used these increasingly flawed men to accomplish his deliverances of the nation. With each cycle, God’s grace is truly more amazing (see Theology).

The cycles section also divides into two parts: the in-group judges and the out-group judges. The in-group judges (Othniel, Ehud, Barak) come from outstanding or acceptable backgrounds. This in-group judge part ends with the Song of Deborah (5:1–31), the only positive celebration of Yahweh’s victory in the book! In certain respects, it is the theological hub of the book (see Theology). While two of these in-group judge cycles (Ehud and Barak) manifest less than perfect characters, the out-group judges exhibit disturbing weaknesses, if not serious faults. The out-group judges (Gideon, Jephthah, and Samson) come from less than acceptable backgrounds: Gideon’s father made a Baal altar and an Asherah pole in Gideon’s hometown; Jephthah is the son of a prostitute and becomes a leader of a gang of criminals; and Samson is from the renegade tribe of Dan, and his parents reveal their spiritual dullness in the two theophanies prophesying his birth and mission.

Thus the Gideon cycle is pivotal as the beginning of the out-group judge cycles. In this out-group judge part, there is a notable religious deterioration: from Gideon-Abimelek (idolatry and the worship of Baal Berith) to Jephthah (human sacrifice) to Samson (doing what was right in his own eyes [see note on 14:3] and violating all of his Nazirite vows). Revenge is a major motif among the out-group judges: in the Gideon-Abimelek cycle it is severe revenge on the two towns of Sukkoth and Peniel, Jotham’s prophetic allegory, Abimelek’s retribution on the people of Shechem; in the Jephthah cycle it is vengeance on the Ephraimites; and in the Samson cycle it is revenge again and again on the Philistines, who are also motivated by revenge. This motif climaxes in the Samson cycle. Beginning with the out-group judges, there is a movement toward civil war that eventually becomes a reality at the end of the book. From Gideon on, Israelite society seems to become more and more fractured and chaotic.

The Gideon narrative is also pivotal because it is the first time that Yahweh meets Israel’s appeal with a stern rebuke rather than immediate assistance. Yahweh’s response in the Jephthah cycle is even more severe: Yahweh is straightforwardly sarcastic in his response to Israel’s continuing apostasy. In the Samson cycle, Israel does not appeal to Yahweh at all. From Gideon on, the major/cyclical judges show significant character flaws.

In the cycles about the in-group judges, things return basically to the status quo that was in effect at the beginning of the cycle. But in the cycles of the out-group judges, things are much worse in Israel at the end of each cycle than they were before the beginning of that cycle. By the end of the Gideon-Abimelek cycle, Israel has returned to worshiping the Baals and has begun to unravel internally. Jephthah reintroduces a situation of instability into Israel with the over-the-top slaughter of 42,000 Ephraimites (similar to Gideon’s and Abimelek’s actions). Finally, Samson has not delivered Israel (though he has killed a number of Philistines in his quests for personal revenge); he really only agitates the Philistines into making their oppression on Israel worse.

The motifs of fire and burning play an important role in the out-group judges. In the case of Gideon, there is the incineration of the sacrifice, the use of 300 torches, etc. Jephthah burns his daughter, and the Ephraimites threaten to burn Jephthah’s house over him. In the Samson cycle, the Philistines threaten to burn Samson’s wife and father-in-law if she doesn’t get the answer to Samson’s riddle; 300 foxes, released by Samson, burn the shocks, standing grain, vineyards, and olive groves; the Philistines burn Samson’s wife and father-in-law; the ropes with which the Judahites tied Samson up became as “charred flax” in the presence of the Philistines (15:14); and the fresh bowstrings used in Delilah’s first attempt to subdue Samson “snapped . . . as easily as a piece of string snaps when it comes close to a flame” (16:9b).

The spiritual decline in the relationship between Israel and Yahweh can also be seen in the characterization of the women of the book. Aksah (Othniel’s wife) is noted for her practical shrewdness and resourcefulness in seizing the blessings of God in the land (1:14–15). This is followed by other women noted for their commitments to the Lord (Deborah [4:1—5:31] and Jael [4:17–22]) or their use by God (9:53–54). Then follows the tragic story of the unnamed daughter of Jephthah (11:34–40), deteriorating to Delilah, who is willing to take the initiative to bring down her man (16:4–22), and culminating with the tragically silent women of chs. 19–21.

Another important observation is that the center cycles (Deborah-Barak and Gideon-Abimelek) manifest a propensity for pairs. Deborah and Barak are paired against Jabin and Sisera. The cycle of Gideon and Abimelek has many pairs. A few are: Gideon faces the pairs of Oreb and Zeeb (killed on the west side of the Jordan) and Zebah and Zalmunna (killed later on the east side of the Jordan); two altar and offering scenes; two names for the hero (Gideon and Jerub-Baal); two different reductions in the size of Gideon’s military force; two battles with surprise attacks; two tests of God by fleece and dew; and two towns on which extreme reprisals are executed.

The Gideon-Abimelek cycle also has two climaxes (although nonparallel): the accounts of Gideon (6:1—8:35) and Abimelek (9:1–57). The Abimelek account prolongs the Gideon account, resolving a number of complications that the Gideon narrative spawns. While both narratives address the issue of the danger of kingship, neither condemns kingship as an institution. But they both demonstrate the significant dangers of the wrong kind of kingship: one that is not patterned according to God’s law (Hebrew tōrâ), one that is Canaanite in its essence. They accomplish this from two different directions: the Gideon narrative is subtle and implicit; the Abimelek story is blunt and explicit. Even though Gideon attacked Baal worship and declared Yahweh’s kingship, he subverted God’s kingship with his own. Abimelek blatantly sets himself up as a king of a Canaanite city with the help of Baal/El.

Both accounts address the issue of infidelity: the Gideon narrative addresses infidelity to Yahweh (8:34), while the Abimelek narrative addresses infidelity to Gideon’s family (8:35). Finally, in many ways, Jotham’s act of challenging the people of Shechem concerning their allegiance to Abimelek is analogous to Gideon’s act of destroying the Baal altar and challenging the people of Ophrah concerning their allegiance to Baal.

There are other clear links between the two center cycles. The Deborah-Barak cycle begins with a prophetess (Deborah) ministering to Israel and ends with a woman performing a mighty deed as an agent of Yahweh (Jael drives a tent peg into Sisera’s skull). The Gideon-Abimelek cycle begins with an unnamed prophet challenging Israel (6:7–10) and ends with a woman performing a mighty deed as the agent of Yahweh (a woman smashes Abimelek’s skull with an upper millstone). Both cycles demonstrate Yahweh’s sovereign control over circumstances in order to bring about victory (over Sisera or Abimelek) and poetic justice (vis-à-vis Barak or Abimelek).

Besides this propensity for pairing in the two middle cyclical judge narratives, it is also clear that there is a set of three pairings among the major judges themselves. Othniel and Ehud form an initial pair. They exhibit the two most successful judges. They are also, by far, the two shortest narratives of the six major judges. They are the only two cycles that designate the judge by the term “savior” or “deliverer” (Hebrew môšîa ʿ ), and they do their delivering in the southern part of the country. The Deborah-Barak and Gideon-Abimelek cycles form the second pairing. They are the pivotal cycles, with Deborah-Barak being the last of the in-group judges and Gideon-Abimelek being the first of the out-group judges. They do their delivering in the northern part of the country. The third pairing is Jephthah and Samson. They demonstrate the most serious character flaws of the six major judges, and the oppressions they address are introduced together (10:6–8). They both feature agreements with leaders and vows to God, and each is undone by a female. In particular, this can be seen in the matter of vows. Jephthah ignorantly fulfills the manipulative, rash vow, but Samson callously breaks the God-ordained Nazirite vow.

Finally, the three pairings of the cyclical judges can be seen in the type of oppressors or opponents they are associated with:

Judge Cycle | Type of Oppressor(s) | Name(s) |

1. Othniel | single, named | Cushan-Rishathaim (king) |

2. Ehud | single, named | Eglon (king) |

3. Deborah-Barak | pair, named | Jabin (king) / Sisera (commander/chief) |

4. Gideon-Abimelek | pairs, named | Oreb and Zeeb (commanders/chiefs); Zebah and Zalmunna (kings); Jotham and Gaal |

5. Jephthah | single, unnamed | — |

6. Samson | multiple, unnamed | — |

While each pairing has its own internal links, there are also strong links between the pairs themselves. For example, the Ehud and Deborah-Barak cycles witness a number of links, the most obvious of which is how each portrays the death scene of the oppressor (Eglon or Sisera). Ehud and Jael are painted in very similar colors as they execute the enemy leader. And there is great similarity between the discovery of Eglon by his Moabite guards and the discovery of Sisera by the pursuing Barak.

There are also very strong links between the Gideon-Abimelek cycle and the Jephthah cycle. Both open with a confrontation between Yahweh and Israel (6:7–10; 10:6–10). Both Gideon and Jephthah begin as nobodies, become heroes (both are characterized as gibbôr ḥāyîl, “mighty warrior”), and end as despots. Both are empowered by the Spirit of Yahweh, which results in the immediate mobilization of troops (6:34–35; 11:29). Both follow up the divine empowerment with expressions of doubt (6:36–40; 11:30–31). Both win great victories over the enemy (7:19–25; 11:32–33). Both must deal with confrontations with the jealous Ephraimites after the battle has been won (8:1–3; 12:1–3). Both brutalize their own countrymen (8:4–17; 12:4–6).

In addition, there are strong bonds between the Abimelek account and the Jephthah cycle. Both men are children of secondary women: a concubine and a prostitute (8:31; 11:1). Both are disinherited by their half brothers. Both recruit morally empty and reckless men to make up their armed gang (9:4; 11:3). Both are opportunists who negotiate their way into powerful leadership positions (9:1–6; 11:4–11). Both seal the agreement with their subjects in a formal ceremony at a sacred site (9:6; 11:11). Both turn out to be brutal rulers, slaughtering their own relatives (9:5; 11:34–40) and engaging their own countrymen in battle (9:26–57; 12:1–6). Both end up as tragic figures without descendants (9:50–57; 11:34–35). Jephthah is in many ways a composite of Gideon and Abimelek.

The short notices about the minor judges are integral to the message. The moral degeneration of the major cyclical judges is also perceptible in the minor noncyclical judges, especially in the concern for building power. The minor judges are presented in a 1–2–3 sequence: (1) Shamgar (3:31a), (2) Tola (10:1a), and Jair (10:3a); (3) Ibzan (12:8a), Elon (12:11a), and Abdon (12:13a). This 1–2–3 pattern is a purposeful way of moving the narrative to the climax in the Samson cycle.

Thus, in every way the cycles section of the book reflects a progressive degeneration. By the end of the story of Samson, the reader is left questioning the value of judgeship altogether. This is precisely what the narrator planned so that his double conclusion to the book (17:1—21:25) would be exactly the proper ending in which to highlight the issue of kingship.

Theology

The book of Judges is a literary masterpiece. However, all the literary structuring and thematic developments are in the service of communicating important theological teachings. The book of Judges portrays a sovereign God of incredible faithfulness to his covenant, who abounds in grace in spite of the great sinfulness of the Israelites and the individual judges.

The downward spiral is heightened by a focus on the covenantal disloyalty of both the people and their leaders, the judges. The depth of this depravity can only be truly perceived through the reader’s familiarity with the law (the Torah), especially the book of Deuteronomy. The author assumes that his readers have some knowledge of the law.

An important example of this is the law of Deut 7 (the law concerning the ḥērem). Although the Hebrew word ḥērem (“totally destroy”) only occurs in 1:17 (see NIV text note) and 21:11 (NIV “kill”), it is clearly the main issue in these passages. Deut 7 explains the law of the ḥērem: the Israelites are to “destroy totally” the inhabitants of Canaan (see Deut 7:2 and NIV text note there) and “set [material objects] apart for destruction” (Deut 7:26), i.e., “devote” the material objects to the Lord; they are not to make a covenant (treaty) with them; they are to show them no mercy; there should be no intermarriage between the Israelites and the Canaanites; and all Canaanite altars and idols are to be destroyed. The purpose of this ḥērem law was to “drive out” the Canaanites (Deut 7:22). Deut 7 stresses that love of Yahweh is demonstrated in the implementation of the ḥērem. Not implementing the law of Deut 7 in all of its aspects is considered covenantal disobedience and disloyalty to the Lord. In Judg 1:27, the Israelites “did not drive out” the Canaanites; instead, the Canaanites “live” among the Israelites, or worse, the Israelites live among the Canaanites (cf. Deut 12:29). In 2:1–5, the Lord condemns them specifically for not carrying out the law of Deut 7; they have made covenants (treaties) with the Canaanites and have not torn down the Canaanite altars. In chs. 20–21, the Israelites misapply the ḥērem law of Deut 7 for their own purposes! A reading of Deut 7 makes very clear that Israel did not obey this law (see Introduction to Deuteronomy: Themes and Theology [Holy War]). This is the beginning of Israel’s spiritual and moral decline. That this is a predominant issue of covenantal unfaithfulness on the part of Israel is seen throughout the book. For example, at the beginning of the Gideon story, an altar to Baal and an Asherah pole have been set up by Gideon’s father!

At the beginning of all six major judge cycles, the text states, “The Israelites did evil in the eyes of the LORD” (3:7; 3:12; 4:1; 6:1; 10:6; 13:1; introduced first in 2:11). The details of this evil are developed as the reader progresses through the book. A contrast is developed between God’s righteousness and the Israelites’ lack thereof (both in perception and deed). Not only do the Israelites do evil as the Lord sees it; they do what is right in their own eyes. The righteous deeds of Yahweh (“the victories of the LORD” [5:11]) are juxtaposed with the “evil” of the people and their leaders. In short, all the deliverances of Israel in the book are testimonies to the Lord’s righteousness.

God chastens Israel for this disobedience (“evil”) by giving them into the hands of oppressors. Israel cannot break the covenant without consequences. God disciplines his people.

Yet God graciously saves Israel, even though the character of the judges becomes increasingly flawed, and disobedience abounds. Thus by illustrating human sin in each successive story, the writer highlights the great lengths to which God goes in order to save his people. No matter how flawed or sinful the judge, God saves (or in the case of Samson, “begins to save” [see note on 13:5]). God demonstrates that he is gracious and long-suffering. Through each cycle, the writer emphasizes that God is sovereign; the disobedience of his people cannot thwart his plan. This absolute divine sovereignty comes together in Yahweh’s roles as judge, divine warrior, and king. His righteousness and sovereignty in these roles make his graciousness and long-suffering very potent and effectual.

At this point, it is important to discuss the listing of some of the judges in the book of Hebrews. Heb 11:32, 39 states: “And what more shall I say? I do not have time to tell about Gideon, Barak, Samson and Jephthah, about David and Samuel and the prophets . . . These were all commended for their faith.” The ordering is in pairs with the first in each pair in reverse chronological order to the second: so Gideon is listed first even though he followed Barak; so too with Samson and Jephthah and David and Samuel (Samuel, in fact, anointed David). The writer of Hebrews is doing this for rhetorical reasons, namely, in order to help the reader get his point: all these individuals were commended for their faith; therefore let believers lay aside everything that keeps them from living a godly life for the Lord (Heb 11:39—12:2). Clearly, the writer does not intend for his readers to conclude that all these individuals had the same spirituality, the same level of faith and maturity. By far the most developed in Hebrews 11 are Abraham (Heb 11:8–10, 17–19) and Moses (Heb 11:24–28), and the writer hardly intends to equate Samson with them in spirituality issues. It is a mistake to read into the Judges passages redeeming features that the writer of the book of Judges is not stating or to interpret the character flaws as not being as serious as they are. So while all had faith, some had significant character flaws, while others had deeper walks with God (e.g., Othniel). Not all of these were the same sort of heroes of the faith. The point is not that all these individuals attained a “hall of fame” level of faith but that all, even to the smallest degree, demonstrated faith. Therefore, these judges really do have the character flaws and sins that the text of Judges attributes to them. But God’s grace is greater than all these character flaws and sins (whether one speaks of the individual judges or the nation of Israel). God uses sinful humans—sometimes very sinful and spiritually immature humans—to accomplish his will.

Another important theological theme is woven into this: the attempt to manipulate God. God saves, but not because he has been manipulated. Attempts to manipulate God can be as simple as Barak’s words, “If you [Deborah] go with me, I will go” (4:8), trying to guarantee God’s presence. Or it can be as rash as Jephthah’s vow (11:30–31). Israel’s attempts to manipulate God through their crying out to him fail (the second element of the cycle). This crying out to God in the midst of the oppression is not due to repentance (as a study of the wording in the original Hebrew demonstrates). Obviously, true repentance is accepted by God. But in the book of Judges, Israel’s cries are increasingly met with prophetic indictments and sarcastic ridicule of their worship of other gods (10:11–13). In every case, God demonstrates that he will not be manipulated by humans. The true and living God cannot be manipulated by finite creatures.

However, idols can be manipulated. The Israelites succumb first to the Canaanite deities (idols, 2:13) and then to those of their own making (8:27–28; 17:1—18:31). Instead of succeeding in manipulating God, the Israelites become ensnared by these idols, whether made by the Canaanites or by their own hands (2:3; 8:27; 17:4). In every attempt, God frustrates the Israelites when they do this by giving them into the hands of their enemies. So why is Israel saved from its oppressors? Not because of manipulation but because of God’s faithfulness to his covenant. God has a plan for the redemption of the world; his will cannot be thwarted by his people’s disobedience or attempted manipulations.

The issue of the covenant (treaty) permeates the book. For God, it is the primary issue (2:1–5), and the writer stresses that Israel’s disobedience to the law is covenantal infidelity, spiritual prostitution (2:17; 8:27). Ironically, it is the judges themselves in the last three cycles who lead Israel down the path of covenantal unfaithfulness: Gideon makes a golden ephod to which all Israel prostitutes itself; Jephthah makes a foolish and manipulative vow that leads to child sacrifice just like those who worship Molek, and he engages in intertribal warfare; Samson does what is right in his own eyes (one of the strongest and most common forms of idolatry). This is true not only of his desire for women but also in his attitude in dealing with the Philistines (which is motivated by personal revenge).

Throughout the book, the issue of the covenant is linked to the issue of kingship. Israel’s disobedience to the covenant is a constant attempt to undermine God’s kingship. This issue becomes particularly acute with the Gideon-Abimelek cycle, but it dominates in the double conclusion, where there is no king in Israel—physically or spiritually. The refrain in the double conclusion is: “In those days Israel had no king; everyone did as they saw fit” (17:6; 21:25; cf. 18:1; 19:1). This is not simply a political statement expressing the desire for a king (in other words, a pro-monarchic and pro-Davidic wish). Rather, based on the second part of the refrain, “everyone did as they saw fit” (an alternate translation is: “each man did what was right in his own eyes”) connects the refrain with the covenant. Thus the refrain is not as much about physical kingship as it is about spiritual kingship. It is not saying, “If we only had a king, things would be different.” It is God’s kingship that is being broken in all that Israel does! Physical kingship will not make a difference in this. Israel will still break the covenant, rebelling against God’s kingship. Later, the whole intention of Israel in wanting a king is deemed by God himself to be rebellion (1 Sam 8:7b: “It is not you they have rejected, but they have rejected me as their king”). Gideon rightly told the Israelites that he would not rule over them, saying, “The LORD will rule over you” (8:23). Thus, the statement that “everyone did as they saw fit” highlights the fact that it is themselves they are serving and not the Lord. When the Israelites rebel against the Lord as their covenantal king, they have no king as envisioned by the covenant; and so everyone acts as their own king. In a real sense, the book of Judges is a prophetic call to acknowledge the kingship of the Lord, the true King and Judge of Israel.

The only song in the book, the Song of Deborah (5:1–31), is one of the most beautiful and emotive victory songs in the Bible: praising God for his deliverance, celebrating his use of nature and storm, his sovereign timing, and his justice over evil men and women (Sisera and his mother). Yet it also emphasizes the participation of the people of God in his kingdom, praising the non-Israelite Jael for her willingness to do what needed to be done for God’s justice and rule. It is not by chance that the Song of Deborah comes at the end of the in-group judge cycles: God’s covenantal kingship will be progressively more undermined from this point to the end of the book, when “everyone did as they saw fit” (21:25b). In many ways, the Song of Deborah is the theological hub of the book: here God is worshiped and praised with a wonderful focus on God’s intervention on behalf of his people.

Outline

I. The Double Introduction (1:1—3:6)

A. Foreign Wars of Subjugation With Failure to Apply the Law of Deut 7 (ḥērem)—the Pre-Judge Political/Military Background—the Incomplete Conquest (1:1—2:5)

B. Difficulties With Foreign Idols—the Thematic Summarizing Outline of the Spiritual Background—the Incomplete Faith (2:6—3:6)

II. Cycles of the Judges (3:7—16:31)

A. Major Judge Cycle: Othniel (3:7–11)

B. Major Judge Cycle: Ehud (3:12–30)

C. Minor Judge: Shamgar (3:31)

D. Major Judge Cycle: Deborah and Barak (4:1—5:31)

1. The Narrative (4:1–24)

2. The Poem: Song of Deborah (5:1–31c)

a. Introduction to the Poem (5:1)

b. Act A: Initial Call to Praise and Report of Need (5:2–8)

c. Act B: Renewal of the Call to Praise Because of the Volunteers (5:9–13)

d. Act C: Recognition of the Tribes That Did or Did Not Participate (5:14–18)

e. Act D: The Battle and the Curse of Meroz (5:19–23)

f. Act E: Jael’s Deed and Sisera’s Mother (5:24–31c)

3. Concluding Framework Statement (5:31d)

E. Major Judge Cycle: Gideon and Abimelek (6:1—9:57)

1. The Gideon Narrative (6:1—8:32)

a. The Setting Before Gideon’s Call (6:1–10)

b. The Call of Gideon (6:11–32)

c. Gideon’s Struggle With Belief in God’s Promise (6:33—7:18)

d. God Delivers Israel From the Midianites (7:19—8:21)

(1) Battle West of the Jordan (7:19—8:3)

(2) Pursuit and Battle East of the Jordan (8:4–21)

e. Conclusion to Gideon’s Life After the Victory (8:22–32)

2. The Abimelek Narrative (8:33—9:57)

a. The Prologue to the Story (8:33–35)

b. Abimelek’s Rise (9:1–24)

(1) Elimination of Rivals (9:1–6)

(2) Jotham’s Fable and Curse (9:7–21)

(a) The Fable (9:7–15)

(b) The Fable Applied (9:16–21)

(3) The Narrator’s Assessment of God’s Involvement (9:22–24)

c. Abimelek’s Decline (9:25–57)

F. Minor Judge: Tola (10:1–2)

G. Minor Judge: Jair (10:3–5)

H. Major Judge Cycle: Jephthah (10:6—12:7)

1. Introduction: Israel Versus the Lord (10:6–16)

2. The Ammonite Threat: The Elders’ Choice of Jephthah (10:17—11:11)

3. Jephthah Versus the Ammonite King (11:12–28)

4. The Ammonite Defeat: Jephthah’s Vow (11:29–40)

5. The Conclusion: Jephthah Versus the Ephraimites (12:1–7)

I. Minor Judge: Ibzan (12:8–10)

J. Minor Judge: Elon (12:11–12)

K. Minor Judge: Abdon (12:13–15)

L. Major Judge Cycle: Samson (13:1—16:31)

1. Samson’s Birth (13:1–25)

2. Samson’s Wedding (14:1–20)

3. Samson’s Revenge (15:1–20)

4. Samson’s Death (16:1–31)

a. The Incident With the Prostitute of Gaza (16:1–3)

b. The Delilah Incident (16:4–22)

c. Samson’s Final Act of Vengeance (16:23–31)

III. The Double Conclusion: Specific Conditions During These Times (17:1—21:25)

A. Difficulties With Domestic Idols—the Origin of the Pre-Monarchic Sanctuary of Dan (17:1—18:31)

1. The Idolatry of Micah the Ephraimite (17:1–13)

a. The Shrine of Micah (17:1–6)

b. Micah’s Priest (17:7–13)

2. The Migration of the Danites (18:1–31)

B. Domestic Wars With Misapplication of the Law of Deut 7 (ḥērem) Being Applied—the Benjamite Atrocity and the War (Chiastically Arranged) (19:1—21:25)

a The Rape of the Concubine (19:1–30)

b The Misapplication of the Law of Deut 7 (ḥērem) on Benjamin (20:1–48)

c The Oaths: Benjamin Threatened With Extinction (21:1–5)

b´ The Misapplication of the Law of Deut 7 (ḥērem) on Jabesh Gilead (21:6–14)

a´ The Rape of the Daughters of Shiloh (21:15–25)

![]()

![]()

![]()