The Time Between the Testaments

Douglas J. Moo

Introduction

A gap exists in our biblical canon between the Old and New Testaments. The OT historical record ends about 430 BC with the return of a small number of exiles to their own land (see Introductions to Ezra and Nehemiah). The latest prophetic book (probably Malachi) was written at about this time. Over 400 years therefore separate the OT and the NT. Because no canonical book was written during these years, they are sometimes called “the silent years.”

But from other perspectives these four centuries were far from silent. They were filled with significant historical, social, and religious developments that help us understand the NT much more accurately. The Gospels bring to the stage a host of characters whom the OT never mentions: Pharisees, Sadducees, teachers of the law, and officials from the Roman Empire (e.g., Caesar Augustus and Pontius Pilate). Who are these people? How can we understand their roles in the gospel story? Even more vital to accurately understanding the NT, however, are the religious developments. The Judaism that Jesus and the NT writers related to stands in continuity with the OT on many basic points, but it also developed beyond the OT in a bewildering variety of ways. Appreciating these developments helps explain the nature of the NT interface with early Judaism and therefore sheds light on key NT teachings that relate to Jewish perspectives.

History

Our sources for the history of Israel during these centuries are varied. The Jewish historian Josephus (AD 37–ca. 100) wrote several long histories that, while not without bias, are invaluable. Some Apocryphal and pseudepigraphical books (especially 1 and 2 Maccabees) cover selected periods of time in considerable detail (see Literature). Other writings touch on events or indirectly suggest perspectives on them. Apart from several allusions in Heb 11:33–38, the NT does not refer to this period.

The history of Israel during these years may be usefully organized according to the world powers that successively dominated the ancient Near East.

The Persian Period

As the OT ends, the nation of Israel exists as a small “temple state” within the Persian Empire. Ezra and Nehemiah, along with the prophets Zechariah, Haggai, and Malachi, shed some light on this early period (as does Esther from a very different perspective). But we know little about the life of Israel during the century from about 430 to 330 BC.

The Greek Period

The conquests by Alexander the Great in 334–331 BC brought Israel under the influence of the Greeks. No single Greek empire emerged from Alexander’s conquests. His death at age 32 in 323 led to a scramble for power among his generals. Two of them managed to establish kingdoms that affected Israel.

Ptolemy consolidated power in Egypt, and the Ptolemies ruled Israel for over a century (323–198 BC). Little is known about life in Israel during this century, but one development proved especially significant. Although Alexander failed to establish Greek political dominance, his conquest did have two consequences that were important for Jewish history and the NT. First, a simplified version of the Greek language, called koine (“common”) Greek, became the dominant lingua franca. Most Jews living in Palestine would have learned this koine Greek as their second language. In God’s providence, then, the NT missionaries and the writers of the NT could use koine Greek to communicate to most people in the world of their day. Second, the armies of Alexander exported to the ancient Near East the Greek worldview and way of life—in a word, “Hellenism.” Hellenism, in contrast to Eastern thought, greatly emphasized human beings and their rational abilities. Its view of life was enshrined in certain institutions, such as the gymnasium, where naked (gymnos) men enjoyed athletic contests and community. Hellenism proved attractive to many people, especially the elite, in the territories that Alexander conquered.

The Maccabees and Jewish Independence

The influence of Hellenism within Israel became a key issue in the tumultuous years 200–160 BC. In 198, Israel became part of the empire that Seleucus, another of Alexander’s generals, founded. The Seleucid Empire, headquartered in Babylonia, was more fragile than the stable Ptolemaic Empire. The Seleucid rulers were accordingly less tolerant of deviant religions and pursued a policy of Hellenization in order to consolidate their diverse territories—including Israel. Matters came to a head under the rule of the tyrannical Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 BC), who in 167–164 attempted to eradicate the Jewish faith. Possessing a copy of the Torah or circumcising one’s son became punishable by death. He demanded offerings to the Greek god Zeus and went so far as to sacrifice a pig in the Jerusalem temple. Antiochus’s persecution led to the famous Maccabean revolt. An elderly Jew named Mattathias sparked the revolt, which was led by a succession of his sons, especially Judas “Maccabeus” (probably meaning “the hammer”). Under Judas’s leadership, Jewish partisans won battle after battle against the Seleucid forces, eventually retaking and rededicating the temple in 165 (an event that Jews celebrate during the festival of Hanukkah). Two brothers of Judas, Jonathan and Simon, successively led the revolt, which succeeded in gaining Israel’s independence from the Seleucids in 166 BC. The Maccabean revolt preserved the Jewish faith in the face of Antiochus’s persecution. But perhaps just as important was the battle for the faith within Israel. Hellenism had penetrated Judaism to the degree that some Jews were, in effect, turning from their ancestral faith. The “faithful ones” (hasidim) who successfully fought the Seleucids just as successfully fought off the creeping Hellenism that would have eviscerated the Jewish faith. For all their success, however, the hasidim did not fulfill OT promises of restoration, leaving the Jewish people still hoping for much more to come.

The Roman Period

A series of rulers in the Hasmonean dynasty, which Jonathan and Simon established, tried to consolidate Israel’s position in the succeeding decades. However, a new world power was taking its place on the historical scene: Rome. Greece had become a Roman province in 146 BC and Pergamum (in Asia Minor) in 136 BC. In 63 BC, Israel, considered part of the larger province of Syria, came under Roman rule. Herod the Great (in power 37–4 BC) was a “client king” of Rome, answerable to Roman authority. All of NT history takes place in the larger context of the Roman Empire. It was the Romans who invaded Israel in the years AD 66–73 to put down a Jewish revolt, destroying the temple in AD 70 and winning the final victory at the fortress of Masada in AD 73.

Literature

While no canonical books emerged during these four centuries, the Jewish people produced a sizable body of other kinds of literature—particularly in the tumultuous years from 170 BC on. This literature falls into five basic categories.

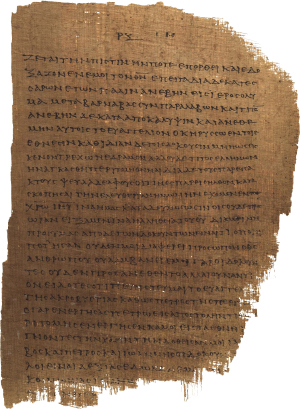

Scripture Translations

As generations of Jewish people lived outside the land of Israel, their ability to understand Hebrew was lost. They needed translations. Greek, which had become the common language of much of the eastern Mediterranean area, was a natural choice for a translation. Jewish legend (see the Letter of Aristeas), probably written more than a century after the event, claimed that 72 translators assembled at the command of the Ptolemaic ruler around 250 BC to produce a translation of the Torah (the Pentateuch). The alleged number of translators has given this translation its name: “Septuagint,” Latin for “70” (a rounding of “72”). This tradition is probably right to locate the origins of the translation in Alexandria, with its large Greek-speaking population, but the tradition is otherwise unreliable. The translation was probably generated by the needs of the Jewish population, with the five books of Moses being translated as early as the third century BC and the other parts of the OT (the Prophets and the Writings) being translated over the next two centuries. Moreover, other Greek translations of at least parts of the OT were probably circulating as well.

Another language that was widespread in and around Israel was Aramaic. Parts of Daniel and Ezra were written in Aramaic, and Aramaic was likely the language Jesus most often used. Jewish teachers probably began translating the Hebrew Scriptures into Aramaic, and from those initial translation attempts arose the “targums,” Aramaic paraphrases of parts of the OT.

The Apocrypha

The Apocrypha (which means “hidden”) is a collection of books the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches recognize as canonical (or “Deuterocanonical”), though they differ over which books they include in this collection. Most of these books appear in the Septuagint. Most early Christians read the Bible in this Greek version, and they therefore tended to put these books on a par with other books of Scripture. Protestants, however, following the lead of the Reformers, reject the canonical status of these books because they are not part of the Hebrew canon. When and how the Hebrew OT took on its official canonical shape is debated, but evidence points to the recognition of a collection of books identical to the Protestant canon sometime before the time of Christ.

While not having canonical status among Protestants, the books of the Apocrypha, almost all of which were written in the time between the Testaments, are valuable sources for understanding Jewish life and thought during these years. They include histories (e.g., 1-2 Maccabees), expansions of Scripture (e.g., Additions to Daniel), stories of God’s faithfulness (e.g., Judith and Tobit), wisdom books (e.g., Sirach), and an apocalypse (2 Esdras).

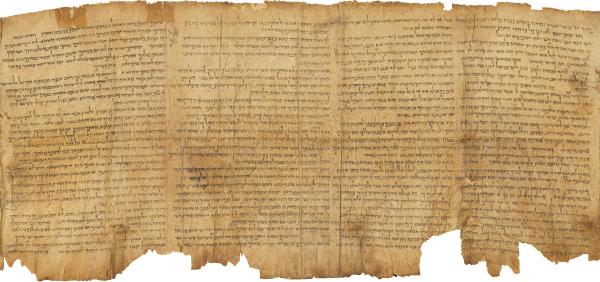

The Dead Sea Scrolls

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a shepherd boy stumbled across some ancient scrolls in a cave near the Dead Sea. Over the next years, a treasure trove of almost 1,000 ancient scrolls were discovered in this area. They are written mainly in Hebrew and include many different kinds of books (and often only fragments of books): biblical texts, apocalyptic works, interpretations of biblical texts, hymns, and directions for the life of a community. The community that produced the scrolls is almost certainly the community whose remains are found at Khirbet Qumran. The scrolls suggest that a group of Jews (perhaps from the hasidim of the Maccabean period) split off from the main body of Judaism and relocated in the wilderness to establish a true and faithful Jewish remnant. Most scholars think these Jews belonged to the Essenes (see The Parties: Jewish Diversity [Essenes]). The community flourished during the first century BC, and the members of the community probably wrote most of the books found on the scrolls.

The scrolls have had a great impact on three areas of study. First, the biblical texts push back written evidence for much of the Hebrew OT by 1,000 years. On the whole, the scrolls confirm that the Hebrew text that forms the basis for our English Bibles (the Masoretic Text) is old and reliable. Second, the scrolls portray a variant form of Judaism, helping us better understand the diversity of Jewish belief and practice at the time of Christ. Third, because the scrolls come from Jews who used the OT to prove that they were the righteous remnant preparing for the coming of the Messiah, they provide intriguing parallels to (and substantial differences from) the early Christian church.

The Pseudepigrapha

The Jews produced many other books in the time between the Testaments. These books vary considerably in genre, origin, and theology, so they are difficult to categorize. They range from collections of psalms (e.g., The Psalms of Solomon) to rewritings of Scripture (e.g., Jubilees) to collections of speeches from famous OT people on their deathbeds (e.g., Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs). Especially frequent are apocalypses, books of visions that are usually attributed to well-known biblical characters (e.g., Adam, Abraham, Moses). The falsely attributed authorship of these books has led to the title for this general collection: “pseudepigrapha,” which means “false writings.” This collection of writings provides invaluable insight into the nature and diversity of Judaism just before and during the time of Christ. But they must be used with caution because some of the books are very difficult to date. Many of the books in the pseudepigrapha were written after (some of them long after) the NT period. And other books in the collection have probably gone through a series of editions, making it difficult to determine which parts may have been in existence in the NT period. Thus, for instance, The Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs, while available in some form during the first century AD, probably did not reach its final form until the second century.

Philo and Josephus

Two Jewish writers responsible for a large body of literature related to the period between the Testaments were Philo and Josephus. Philo (ca. 20 BC–ca. AD 50), a native of Alexandria in Egypt, wrote many treatises about the OT and the Jewish faith. Keen to explain and defend the Jewish faith to his Greek-educated contemporaries, Philo extensively used allegory to interpret the OT in terms of contemporary philosophical categories. Josephus (AD 37–ca. 100) was a historian who took part in the Jewish revolt against Rome in AD 66–73 and later moved to Rome, where he wrote extensive histories of Israel. Although not without his own bias, Josephus provides a lot of information about the time between the Testaments that we would not otherwise possess.

Cultural and Religious Developments

Diaspora

“Diaspora” comes from the Greek for “scatter.” It refers to the “scattering” of Jews throughout the world, initially through exile and later through emigration as well. More Jews lived in the Diaspora than in the Holy Land during the NT period (see map). The contrast between the pagan culture in which Diaspora Jews were immersed and their Jewish faith created special challenges for them. Many undoubtedly assimilated their Judaism to their surroundings. But many others remained faithful to their heritage, maintaining ties to the Holy Land and the temple by sending regular contributions and making occasional pilgrimage trips.

The Synagogue

The many Jews who lived in the Diaspora were cut off from the vital community forming and shaping ceremonies of the Jerusalem temple and therefore had to develop other means of maintaining faithfulness to Judaism. It is possible that the synagogue had its origins in this Diaspora context. Jews would gather on the Sabbath to read the Torah, pray, and generally encourage one another in their faith. We cannot be sure when synagogues were first established, but they were widespread by the NT period (e.g., Matt 4:23; Acts 13:5).

The Parties: Jewish Diversity

The Jewish historian Josephus refers to three “philosophies” that were popular among the Jews of his day: the Essenes, the Sadducees, and the Pharisees (Antiquities, 18.11). By calling them “philosophies,” he hoped to make Judaism understandable for his Roman readers, but they are better called “parties.” The existence of these parties is a reminder that the Jewish faith in Jesus’ day was very diverse. At the same time, most first-century Jews belonged to no party. Those who prided themselves on their party affiliation sometimes labeled these average people the “people of the land” (the am ha-eretz).

Sadducees

The Sadducees were Jews, probably few in number, who were willing to work closely with the governing Romans. They controlled the priesthood through much of the NT period (cf. Acts 5:17). In theology, they insisted that doctrine had to be built on only the five books of Moses, and they rejected the increasingly popular belief in resurrection (Luke 20:27).

Essenes

Little was known about the Essenes until the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered. The NT does not mention the Essenes (at least by name). Most scholars now agree that the Essenes produced most of the scrolls. But we need to use caution concerning sweeping conclusions since there may have been other Essenes who did not hold all the beliefs of the Dead Sea Scrolls community. The group of Essenes who established the community at Khirbet Qumran was disenchanted with the temple establishment of their day, so they moved to the wilderness to reestablish a pure worship of the Lord. They were devoted to strict interpretation of the law and to personal purity, eagerly anticipating the appearance of the Lord to fulfill OT prophecies.

Pharisees

Jesus debated the Pharisees more than any other Jewish party—probably because the Pharisees lived among the people and were very influential. They practiced strict purity, often taking the form of separation from anything they considered impure. They tried to convince average Jews to pursue a similar purity. They sought to direct the life of the Jews through their interpretation of the law. These interpretations became so authoritative that they were viewed as a second law, an “oral” law. The Pharisees were the only party to survive the destruction of the temple in AD 70 and were the precursors to the rabbis.

Zealots

Although Josephus does not include them in his list of Jewish “philosophies,” the Zealots deserve mention. Their hero was Phinehas, who preserved Israel’s purity by killing an Israelite and his Midianite lover (Num 25:6–8). The Zealots embraced violence against the Romans as a way of purifying Israel from foreign influence. They sparked the rebellion against Rome that brought upon Israel the disaster of Roman invasion in AD 66–73. The NT does not mention the Zealots as a group, but one of the Twelve may have been a devotee of this movement: “Simon the Zealot” (Matt 10:4).

Theological Developments

Jewish beliefs during the intertestamental period were firmly rooted in the OT but also underwent significant revision. These revisions were made in response to three key factors:

1. The Jewish people needed to figure out how to live under relatively constant subjugation to foreign powers.

2. The many Jews living outside the Holy Land needed to develop a theology that enabled them to live in the midst of pagans and worship God apart from the temple.

3. The Jewish people of the intertestamental period were exposed to new ways of thinking that inevitably affected their beliefs. The most important of these was Hellenism, the dominant worldview of the period. Some Jews sought to syncretize their faith with Hellenistic ideas, while others resisted Hellenistic influence.

The existence of several different “parties” within Judaism reminds us that these theological developments were not uniform. Theological diversity characterized this period. This diversity is important to keep in mind when we assess “the Jewish background” to the NT. We might more accurately refer to “the Jewish backgrounds.”

Within this diversity, however, we also find certain beliefs that almost all Jews held in common. Four were particularly important: monotheism, election, the centrality of torah, and eschatology.

Monotheism

The idea that there is ultimately only one true, supreme God, who alone must be worshiped, was carried over from the OT into the intertestamental period. This monotheism distinguished Judaism from most of the other religions of the intertestamental and NT epochs. To be sure, some Jews during this time engaged in considerable speculation about the existence and influence of other powers closely related to God. They extensively developed the OT teaching about angels and sometimes gave important roles to OT concepts such as wisdom and the word in mediating God and his purposes to humans. These mediators became important partly because God was being viewed as increasingly transcendent and removed from the everyday lives of Jewish people. These speculations have left their mark on the NT, although the theory that these figures paved the way for the early Christians to ascribe deity to Christ goes beyond the evidence.

Election

Jews of the intertestamental period strongly maintained one of the central teachings of the OT: God chose Israel to be his special people. At his own gracious initiative, God entered into a covenant with this people. Indeed, this conviction became increasingly important as persecution (such as that under Antiochus IV Epiphanes) and dispersion forced the Jewish people to reaffirm and guard their unique identity. At the same time, the division of Judaism into competing parties meant that these groups entered into competition with one another for the distinction of being “true Israel.” Election, then, became not simply a matter of God’s choice of a nation. Election also became tied to certain kinds of behavior that marked those Jews who were truly “the elect ones.” In some Jewish circles, what one did, or one’s merits, became important as a basis for election. NT Christians entered into this debate, claiming that adherence to Jesus, the Messiah, was the only true mark of election.

The Centrality of Torah

When God chose Israel, he gave the people a series of commandments and prohibitions setting forth their obligations to him within the covenant. This covenant law (Hebrew torah), mediated through Moses, was central to the life of Israel. Israel’s stubborn refusal to live by this law led to her exile. The Jewish people of the intertestamental period were united in affirming the importance of living under the torah in order to maintain their place within God’s covenant and as a means of separating themselves from the hostile cultures in which they lived. But two developments in the Jewish view of torah during this period are important to note.

First, the content of torah was debated. While almost all Jews affirmed the continuing validity of the law of Moses, the conditions in which they lived (in the midst of pagans and for many away from the Holy Land) led to certain revisions. Groups such as the Sadducees insisted that only the written laws of Moses should govern the people. But others, such as the Pharisees, sought to give the people guidance for their lives by extending the written law of Moses. Their interpretations and applications of the written law morphed into virtually a second law, an “oral” law, standing alongside the written law. Many Pharisees claimed that this law originated with Moses himself. It is this extended law that Jesus had in view when he criticized some Pharisees and teachers of the law for insisting on obedience to “the tradition of the elders” even when that tradition undercut the written law (Matt 15:1–9).

Second, the great stress placed on torah obedience during this period fostered among some Jews a kind of legalism. The balance between God’s gracious choice and human response in salvation is a delicate one that is easy to tip too far one way or the other. The Jewish people in the intertestamental period maintained a lively conviction about the importance of God’s gracious election. But since so much emphasis was placed on obedience to torah as the expected means of accessing and living within this gracious election, a certain reliance on this obedience for one’s status before God became all too common. Diversity over the relative importance of God’s grace and human obedience to the law marked this period of Jewish history. But most Jews were united in insisting that “doing the law” was a necessary basis for securing God’s election. It is probably this tendency that Paul has in mind when he warns about seeking to be justified by “the works of the law” (e.g., Rom 3:28; Gal 2:16).

Eschatology

Most of the Jews during this period were anticipating a time when God would intervene decisively to reward his people and punish evildoers. The return of some Jews to the land of Israel made a start in the fulfillment of the prophetic promises. But many of those promises remained unfulfilled: Israel languished under Gentile domination, and the people were far from the righteousness that the prophets predicted (e.g., Isa 54; Ezek 34:20–31). Considerable diversity marked this general eschatological expectation. Groups who enjoyed positions of power and privilege, such as the Sadducees, did not have a strong eschatological hope. Those Jews who did entertain a robust expectation of the future differed considerably about how God would fulfill that expectation. Many looked for a royal, warrior Messiah, in the model of David, whom God would use to bring in his final kingdom (see especially the Psalms of Solomon). This expectation explains why the people tried to make Jesus their “king” after his spectacular miracle of feeding the 5,000 (John 6:15). Other Jews expected two Messiahs, one royal and one priestly (see The Parties: Jewish Diversity [Essenes]). Still others did not expect a Messiah at all, thinking that God would intervene directly or through an angelic intermediary. These diverse ideas about the Messiah made it particularly difficult for Jesus to identify himself as the Messiah without creating confusion or misunderstanding. It is probably for this reason that he was reluctant to use the title often.

One important intertestamental development related to eschatology was apocalyptic literature. Apocalyptic writing has its roots in the OT, especially in the book of Daniel. Apocalyptic is often associated with a certain kind of eschatology, one that focuses on a sudden and dramatic turn of events in which the present evil age gives way to an age of righteousness. This division of history into two epochs is fundamental to NT eschatology. However, the revelation that the Messiah would be coming twice requires an important modification in the scheme. The first coming of Christ inaugurates the new age but without eradicating the old age. It is with the second coming of Christ that this old age will cease to exist and the new age will be consummated. Though using “apocalyptic” to describe this kind of eschatology is appropriate, it is too narrow. The word apocalyptic comes from a Greek word meaning “revelation,” and its essence is the revelation of divine mysteries as a human being is given access to heavenly realities. Our world, with its sin and evil, is often hard to square with the realities of a powerful and loving God. The apocalyptic seers are taken behind the scenes of this world and given a vision of what is really going on. They see the reality and power of God and receive insight into his purposes in history. Books taking this form were often themselves called “apocalypses.” Written in the name of a great figure in Israel’s history (thus pseudonymous), apocalypses were an important literary genre in the intertestamental period. The book of Revelation shares many characteristics with these apocalypses (see Introduction to Revelation: Genre [Apocalypse]). While not pseudonymous (John writes in his own name), the book of Revelation takes God’s people behind the distressed scenes of this world to a vision of our God on his throne, infallibly working through the slain Lamb of God to accomplish his good and holy purposes for his entire creation.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()