Throughout history, insects have given us many products of great significance, and many of these products have retained their significance to this day. Some are well known, such as honey and silk. Others you may never have heard of, or even realised that they originated from an insect, like the red colouring in your strawberry jam or the glossy sheen on the skins of supermarket apples.

And, as always in the case of insects, we’re talking about enormous numbers. Even the 1.5 billion head of cattle on the planet pale into insignificance when we add up all the livestock in the insect world. According to statistics from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, more than 83 billion honeybees buzz around the world in our service. And every year, upwards of 100 billion silkworms sacrifice their lives to provide us with silk.

Wings of Wax

Honeybees make honey, of course, as discussed in Chapter 5 (see here). But honeybees also make beeswax, a soft mass produced by special glands in their abdomens, which they use to build nurseries, and warehouses for their honey. Beeswax also has many applications for humans and plays a major role in a mythological tale that will be familiar to many.

In Greek mythology, Daedalus and his son Icarus flee Crete using wings that Daedalus has created from birds’ feathers and beeswax. Daedalus cautions his son against the dangers of complacency and arrogance before they set off: if Icarus doesn’t make enough of an effort, he’ll end up flying too low and the sea will destroy his wings. If, on the other hand, he is overcome by hubris and fails to recognise his own limitations, he will fly too high and the sun will melt the beeswax holding his wings together (a psychologist might perhaps note at this point that the father would have been better off telling his son what he ought to do instead of teaching him about all the pathways to complete catastrophe). At any rate, young people clearly didn’t listen to their parents in those days either: Icarus flew too close to the sun, the wax melted, and he crashed into the ocean. But at least he had a sea (the Icarian Sea, which is part of the Aegean) and an island (Icaria) named after him.

Nowadays, we use beeswax to make candles and cosmetics rather than wings. The Catholic Church has traditionally been a major consumer because the candles used during Mass must be made of beeswax: the pale wax is supposed to symbolise Jesus’ body, while the wick at the centre represents his soul. The flame that burns when the wax candle is lit gives us light, while the wax candle itself burns down – sacrificing itself, as Jesus did for humanity. Only the purest wax can be used for this purpose, and bees score high on that count: since nobody had observed them mating, they were long assumed to be virgins who lived a life of sexual abstinence. Only in the 1700s was this misapprehension corrected (see here), but to this day the rules state that the candles used for Mass in the Catholic Church must contain at least 51 per cent beeswax.

It has become increasingly common to use beeswax in products such as creams and lotions, lip balm and moustache wax. Honey is also an important component of cosmetics, by the way. If, say, you fancy following one of the many recipes for homemade honey facemasks on the Internet, you’ll be glad to hear that you are in illustrious company: the wife of the Roman Emperor Nero, Poppaea – who, of course, didn’t have the option of ordering products from the online outlets of the finest French cosmetics companies – made her own facemasks from honey mixed with asses’ milk. At least that means it doesn’t matter if you happen to get some on your lips! Indeed, beeswax mixed with vegetable oils is actually an excellent lip balm.

Beeswax is also used to help oranges, apples and melons keep better, and to make them look shiny and tempting. This familiar foodstuff (E901) is applied to the surface of fruits, nuts and even food supplement pills (as is shellac, see here). A significant amount of the beeswax extracted from hives these days is also used to produce new beeswax frames that are placed back in the hives – a proper thank-you present!

Silk – a Fabric Fit for a Princess

Silk billows beautifully, is strong but light, cool against the skin, and has a special sheen all of its own. An exclusive fabric, it’s hardly surprising that silk from silkworms – the larvae of the Bombyx mori butterfly – was long reserved for the Chinese Emperor and those closest to him.

The history of silk reads like a tale from the Arabian Nights: exotic yet brutal, it’s difficult to separate fact from fiction. Two strong women play a central role in the legend. In the beginning, 2,600 years before the Western Common Era, the Chinese princess Lei-Tsu sat drinking her tea under a mulberry tree in the garden of the Imperial Palace when a silkworm cocoon fell out of the tree and into the Princess’s cup. Lei-Tsu tried to fish it out, but the heat of the liquid dissolved the cocoon, transforming it into the most beautiful thread – long enough to cover the entire garden. And in the very innermost part of the cocoon lay a tiny larva. Lei-Tsu immediately grasped the potential of this discovery and got the Emperor’s permission to plant more mulberry trees and breed more silkworms. She taught the women at the Imperial Court to spin the silk into a thread strong enough to be woven, thereby laying the foundations of Chinese silk production.

Silk production would remain an important cultural and economic factor in China for several thousand years. Indeed, the country is still the world’s largest silk producer, and to this day, the cocoons are placed in boiling water to kill the larvae and loosen the thin silk threads.

China guarded the secrets of silk for a good long time. Eventually, the trading routes known as the Silk Road opened up between China and the Mediterranean countries, where silk was an important product because the Romans loved it. That said, some viewed this new, almost transparent fabric as immoral; indeed, certain people went so far as to claim that silk dresses were practically an invitation to adultery because they left so little to the imagination.

Be that as it may, we might speculate whether it was actually the amount of gold leaving the Roman Empire to pay for the silk that people found immoral rather than the fabric itself – because China’s monopoly on silk production earned the country enormous income. Consequently, people were also strictly forbidden from sharing the secret: attempts to smuggle out silkworm larvae or eggs were punishable by death.

In the end, the secret came out anyway, and once again a woman played a central role, if we are to believe another of the many legends. It is said that a Chinese princess married the Prince of Khotan, a Buddhist kingdom in the west of modern-day China that lay along the Silk Road. On her departure, the princess smuggled out silkworm eggs and mulberry tree seeds in her headdress. In this way, the secret spread, the monopoly was broken and several other countries started to produce silk. Today, more than 200,000 tonnes of silk are produced each year to make clothing, bicycle tyres and surgical thread. Silkworms are still the main producers, although a few other related species are also used.

Hanging By a Thread

Silkworms are not the only insects that spin silk. This skill has probably cropped up more than 20 times among insects over the course of evolution. Green lacewings, for example, fasten their eggs onto small stalks of silk. They resemble tiny Q-tips, with the eggs like a clump at the end, and their purpose is to stop ants and other starving souls from getting their mitts on them. Caddisfly larvae spin silken trapping nets in streams, which they use to capture small creatures for their dinner; the larvae of certain members of the mosquito family spin a trapping net that they use to gather up spores beneath fungi or to trap small insects. Some of these fungus gnat larvae are even luminous, emitting a blue-green light – although nobody has actually managed to explain why. Unlike the luminous mosquito larvae in the caves of New Zealand, which are predators and use the light to lure their food into the net, our European Keroplatus species seem content to obtain their protein from fungus spores and have no obvious reason to play at being light bulbs.

© Carim Nahaboo 2019

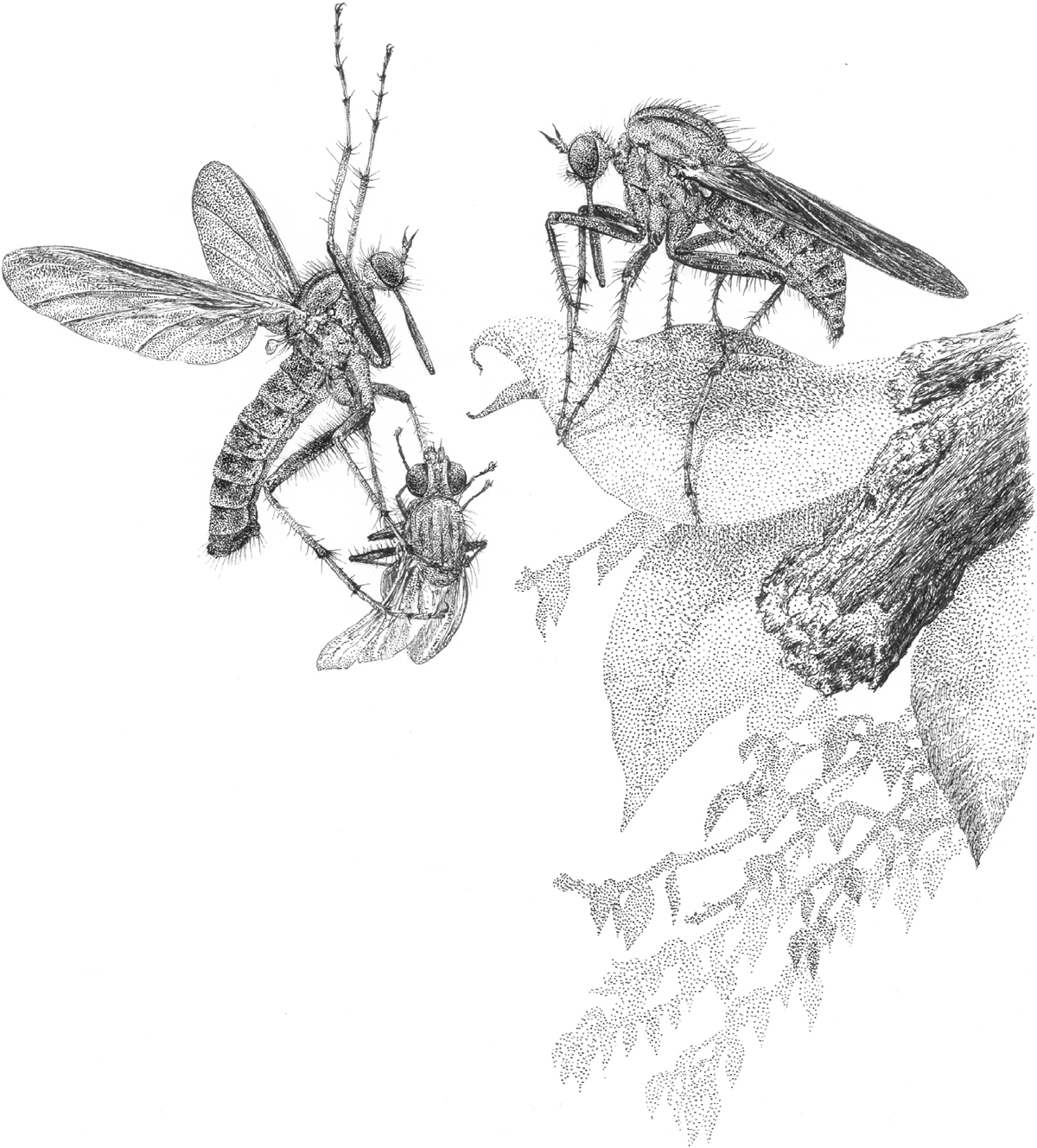

Among some species of dance flies the males use silk to pack up a delightful ‘nuptial gift’ for the female. The males are not predators themselves – they subsist peacefully on a diet of nectar – but they’ll do anything for their greedy, protein-crazy inamorata so they trap an insect (preferably another male because that reduces the competition for females – two birds with one stone, so to speak) and wrap their prey up beautifully in silk produced by special glands on their forelegs. A suitor bearing gifts that he’s even taken the trouble to package himself – it sounds delightful but the reality isn’t especially romantic. This behaviour simply shows the hidden hand of evolution at work, as always. One theory is that the bigger the present and the better the packaging, the more time the male gets to mate. Consequently, he transmits more sperm and has a greater chance of passing on his genes. And it’s fantastic for the female to receive a hefty dose of protein because laying eggs is an energy-intensive business.

But there’s always the odd trickster who’ll try to get the benefits without putting in the effort: some males give the female an empty ball of silk – and then have to get the mating over with pretty sharpish before the lady discovers she’s been duped.

Weaving Miracles: The Spider’s Silk

We can’t talk about silk without mentioning spiders, even though they are arachnids rather than insects. The group takes its name from the person who became the first spider, according to Greek mythology: a talented weaver called Arachne, who had the temerity to challenge none other than Athene, the Greek goddess of war and wisdom, claiming to be the better weaver. The punishment for her arrogance was to be transformed into a spider. And what an ancestral mother Arachne turned out to be! Today, we know of more than 45,000 species of spiders. And the silk isn’t just used to make webs for trapping the spider’s prey, it is also a kind of compensation to the arachnids for lacking the wings they can only envy their distant relatives, the insects. By climbing up to an airy spot and producing a long silken thread that the wind can catch, small spiders can sail away on the breeze using their own kiting technique.

Spider silk has impressive qualities. On a per-weight basis, it is six times stronger than steel, but at the same time highly elastic. That is why a heavy fly that blunders into the web can’t simply pass straight through it. Instead, the web gives, a bit like the arresting cables that help fighter planes land on aircraft carriers. This enables thin fabric made of spider silk to halt a flying projectile – a property that can be used to make extremely light bulletproof vests, super-absorbent helmets and a new type of airbag for cars. If only we were able to learn how to get hold of sufficient amounts of spider silk . . .

Experiments have shown that it is possible to harvest around 100 metres of silk from a single spider, but it’s when you want to scale up that the trouble starts. Unlike the fat, laid-back silkworm larvae who think of nothing but eating the leaves of the mulberry tree and spinning their raw silk, spiders are predators who have no qualms about eating each other, so it’s not especially easy to keep them in captivity in order to set up industrial-scale silk production.

A beautiful golden dress woven from the silk spun by golden orb spiders from Madagascar broke records for visitor numbers when exhibited in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 2012. And that’s hardly surprising because it is a truly remarkable garment, which was four years in the making. Every morning, 80 workers collected new spiders. They were hooked up to a small hand-operated machine, where they were ‘milked’ of their silk and then released again in the evening. In all, 1.2 million spiders were needed.

It’s plain to see that this is an unsustainable option for industrial production, so people have started to think along different lines. In 2002, the first ‘spider goats’ saw the light of day. With the aid of gene technology, scientists simply transferred ‘spinning genes’ from a spider to a goat, which then began to produce milk containing the proteins involved in silk production. This sparked considerable media attention but hasn’t yet yielded any concrete results to speak of. Norway’s neighbours have also thrown themselves into the race to produce synthetic spider silk. The Swedes recently reported that they had produced an entire kilometre of thread using water-soluble proteins produced by bacteria. The protein solution solidifies into spider silk when chemical conditions are altered – exactly the same thing that happens at the opening of the spider’s spinnerets.

We’re still a long way off commercial production and perhaps that’s not so surprising: after all, spiders have had around 400 million years to perfect their silk.

Thank Insects for 700 Years of Notes

Shakespeare’s plays and Beethoven’s symphonies. Linnaeus’s flower sketches and Galileo’s drawings of the sun and the moon. Snorre’s Sagas and the American Declaration of Independence. What do all these things have in common? They were all written using iron gall ink – a purplish-black ink that we have an insect to thank for. A tiny little insect called a gall wasp. These little critters are parasites on plants and trees, and are most commonly found on oaks. Gall wasps secrete a chemical substance that triggers a growth on the plant, which forms a house and pantry around one or several larvae.

There are many varieties of galls. One type that is often used for ink is the oak gall, also known as an oak apple. And it does, in fact, look like a small apple – perfectly round with a reddish tinge – except that it happens to be stuck to an oak leaf.

Inside their oak apples, gall wasp larvae lie chomping away on plant tissue in the peace and quiet, protected against all foes. Well, only partly, because some parasites have parasites of their own: unwelcome guests who turn up for dinner uninvited and refuse to leave again – such as guest gall wasps that simply move into other wasps’ galls because they can’t make their own. Worse still are the interlopers who use their long egg-laying stingers to poke their way through the walls of the gall and lay eggs in the very gall wasp larva living there. As a result, the insect that hatches out of a gall may be very different from the species responsible for the gall’s creation in the first place.

The walls of the oak gall are stiff with a form of tannic acid. This acid occurs naturally in many plants and trees, and is the substance that links your leather jacket with a fine red wine. Tannic acid is crucial for tanning hides and leather, and at the same time, a master wine connoisseur can distinguish grape varieties and storage methods based on the tannins in a wine.

The first types of ink, made in China several thousand years before the Common Era, used carbon from lamp soot. The soot was mixed with water and gum arabic, a natural gum obtained from acacia trees, which kept the soot suspended in the liquid. But if you were unlucky enough to spill a cup of tea over your writing, your thoughts would be lost forever. Carbon ink was water-soluble and easy to wash away – which people also tended to do if they ran short of writing materials.

Later, people learnt to make ink from oak galls mixed with an iron salt and gum arabic. The great advantage of this new ink was that it was non-soluble: it ate its way into the parchment or paper that it was written on. What’s more, it wasn’t lumpy and was easy to make. From the 1100s to well into the 1800s, oak gall ink was the most commonly used variant in the Western world.

If it hadn’t been for the little oak gall wasp it is far from certain that we would have so many well-preserved and legible documents from the great artists and scientists of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. If we’d only had lampblack ink, many ancient thoughts, tunes and texts would have been washed away by water, either because storage conditions were poor or somebody wanted to re-use the parchment.

Carmine Red: Spaniards’ Pride

Insects provide us with colours other than the brown-black hue of oak gall ink. They are also responsible for a beautiful, deep bright red colour that was, for several hundred years, exclusively produced in the Spanish colonies and which is still in use today, in both food and cosmetics.

Carmine dye is harvested from the females of a particular species of scale insect (Dactylopius coccus), peculiar creatures the size of a fingernail that are also known as cochineal bugs. Their natural habitat is in Southern and Central America, where the females spend their entire life on a single spot, wingless and firmly clamped beneath the protective shield of a prickly pear.

The dye was known to both the Aztecs and Mayans long before the arrival of the Europeans, and they bred a variant that yielded a more intense red colour. Since this colour was both difficult and expensive to produce in Late Medieval Europe, dried cochineal bugs were one of the Spanish colonies’ most important wares, valued on a par with silver – because carmine was an intense, powerful red colour that withstood sunlight without bleaching. The famous ‘redcoats’ of the British soldiers were dyed with carmine and Rembrandt, among others, used the colour in his paintings.

Since the dried insects were small and had no legs, and this was before the days of microscopes, Europeans were long uncertain whether the grains of carmine were animal, vegetable or mineral in origin. The Spaniards kept the secret close to their chests for nearly 200 years to assure their monopoly and the vast income the little insect generated for them.

Nowadays, carmine comes largely from Peru. The dye, whose E-number is E120, is used in many red food and beverage products, such as strawberry jam, Campari, yoghurt, juice, sauces and red sweets. You will also find it in different cosmetics, such as lipstick and eye shadow.

Shellac: From Varnish to False Teeth

What do jelly beans, gramophone records, violins and apples all have in common? A substance extracted from an insect, of course. It’s a product with an incredible number of applications, yet you’ll probably never have heard about its origins. We are talking about shellac, a resin-like substance produced by the lac bug (a relative of the cochineal bug that gives us carmine). There are heaps of these tiddlers on the branches of various tree species in Southeast Asia. According to some sources, the name derives from the Sanskrit word lakh, meaning 100,000, and refers to the enormous numbers of these bugs that can be found in a single place. (A brief diversion: the same source has it that the Norwegian word for salmon, laks, has the same linguistic origin for the same reason, because of the large amounts of salmon that gather in the mating season.)

There are several species of lac bugs, but the most common ‘productive’ variety is Kerria lacca. Lac bugs are members of the true bug family (see here) and spend most of their lives with their snouts stuck into plants. A pretty dull existence, then. But good heavens, the things this little life has given us humans! One science article went so far as to say that ‘Lac is one of the most valuable gifts of nature to man.’

The tradition of cultivating lac bugs goes back a long way. The insect is mentioned in Hindu documents from 1200 BCE and Pliny the Elder described it as ‘amber from India’ in writings dated 77 CE. But it wasn’t until the end of the 1300s that Europeans set their eyes on the product – first as a dye and later as a varnish – in other words, a substance you apply to wood to form a glossy, waterproof surface. Beautiful furniture, woodwork and violins were all traditionally treated with shellac.

But it turned out to have many more areas of application. For 50 years, from the end of the 1800s right up until the 1940s, shellac was the main ingredient in gramophone records. It was mixed with ground rock and cotton fibre to produce what Norwegians used to call ‘steinkaker’ or ‘stone cakes’: brittle, breakable 78 records (in other words, discs that rotated at 78 revolutions per minute). The sound reproduction was so-so but the early record players – or ‘talking machines’ as they were then known – were tremendous fun in those days. Bear in mind that radio hadn’t yet become common: the world’s first ever public radio broadcast wasn’t transmitted until 1910 in New York City, and in Norway, test broadcasts didn’t start until 1923, so for a long time gramophone records offered the only opportunity to host a ‘virtual’ orchestra or band in your own living room.

Record production was at such high levels in the 1900s that the American authorities started to get worried, because shellac was also important for the military industry, which used it in detonators and as a waterproof sealant for ammunition, among other applications. In 1942, the US authorities ordered the record industry to reduce its shellac consumption by 70 per cent.

But how do these tiny insects produce a substance with so many varied areas of application: in varnish, paint, glazing, jewellery and textile dyes, false teeth and fillings, cosmetics, perfume, electrical insulation, sealant, the glue used to restore dinosaur bones and a raft of other areas in the food and pharmaceutical industries?

It all starts with thousands of tiny lac bug nymphs settling on a suitable twig. With their sucking mouths, they slurp down plant sap; this undergoes a chemical change inside them and oozes out at the rear as an orange resin-like liquid, which hardens when it comes into contact with air. This forms small, shiny orange ‘rooftops’, which initially cover only the individual bugs, but gradually merge into one giant roof that shelters the entire colony and can cover a whole branch. After shedding their skins a few times, adult scale insects hatch out, then mate and lay eggs, well protected by the roof. The adults then die and the eggs hatch into thousands of new nymphs, which break through the resin roof and set off to find themselves a suitable new branch.

In order to make shellac, the resin coating must be scraped off the branches. It is then crushed and cleaned of insect fragments after which it is ready for market – as small amber-coloured flakes or dissolved in alcohol.

Most shellac production happens in India these days. And the good thing is that small-scale farmers in rural villages are the ones doing the job. Some three to four million people – many of whom have few other means of earning money – are estimated to earn their bread from keeping lac bugs as livestock. Moreover, the production helps keep species diversity rich in the ‘grazing areas’ of this tiny domestic creature. One reason for this is that little or no pesticide is used because that would also put the lac bugs’ lives at risk.

Lac Bugs’ Skincare Clinic for Dull Apples

Don’t those shiny apples in the fruit aisles look delicious? Hardly surprising, because they’ve been for a waxing session at the lac bug’s skincare clinic. What happens is this: we humans eliminate the apples’ natural wax coating when we wash them after harvesting. And without wax, the apples quickly turn into wrinkly, unappetising fare that few people would want to sell and even fewer would wish to buy. So, apples have to be waxed again – and that’s where shellac comes in, like a sort of anti-wrinkle cream.

Many other types of fruit and vegetables also undergo a round of shellacking to ensure that they last longer and look more appealing. The substance is approved for use on citrus fruits, melons, pears, peaches, pineapples, pomegranates, mangos, avocados, papayas and nuts. In 2013, shellac was also approved to buff up hens’ eggs in Norway. The idea is to make the eggs nice and shiny, and increase their shelf life.

In the guise of E-number E904, shellac also turns up as glazing for various sweets, such as jelly beans, sugar-coated chocolates, pastilles and the like. This glazing agent goes by many other names: lacca, lac resin, gum lack, candy glaze or confectioner’s glaze.

Shellac is used in cosmetics, too: in hairspray and nail varnish, and as a binding agent in mascara. It is also used in pills in capsule form, and not just to make the surface shiny: because shellac doesn’t dissolve very easily in acid, it can be used to make ‘delayed-release’ pills. In other words, capsules that only dissolve when they reach the gut system.

Once you realise just how many strange places this product pops up in, perhaps it no longer seems so peculiar that somebody should call shellac one of the most valuable gifts of nature to man.