Chapter 5

GETTING STARTED

Equipment, Methods, Issues

When I produced the first edition of this book there were virtually no home-roasting machines on the market. If you wanted to roast coffee at home, you had to improvise. Today, however, a growing number of home-roasting devices are available, all waiting for their big breakthrough to appliance-world stardom, meanwhile entertaining off-Broadway roasting aficionados like readers of this book.

True, the “perfect” home roasting device still eludes us. But perfection is boring anyhow, and the units currently on the market give the home roaster an engaging array of technologies that combine automated efficiency, good roasting practice, and an occasional whiff of coffee romance.

Plus there remain the many improvised home-roasting methods. For the coffee hobbyist who is patient and who doesn’t require the security of walk-away-from-it automation, these improvised approaches offer certain advantages over dedicated roasting equipment as well as the creative satisfaction of doing it yourself. Improvised equipment also is cheaper. As of this writing, dedicated home-roasting machines vary in price from about $70 to $580, whereas most improvised home roasting setups cost less than $30.

The following pages outline a range of both dedicated and improvised home-roasting devices and approaches, describing the virtues and limitations of each, and give some hints for obtaining good results no matter which machine or method you use. Thereafter, you will find advice on controlling degree or color of roast, cooling roasted beans, dealing with roasting chaff and smoke, and, for serious aficionados, advice on approaching roasting systematically using a roasting log.

To save you having to make notes or turn down the corners of pages, the important practical information contained in this chapter is summarized in list format in the “Quick Guide to Home-Roasting Options and Procedures”.

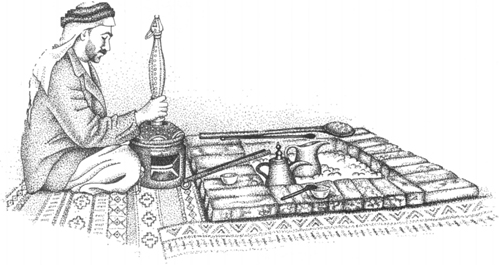

The Arabian coffee ceremony. The word ceremony may have originated with European commentators, who remarked on the similarities between this Arab (and the similar Ethiopian and Eritrean) practice to the better-known Japanese tea ceremony. The coffee ceremony is a bit less formal than its tea-drinking counterpart, but also technically more complex, since the coffee is not only brewed and drunk during the course of the event, but roasted and ground as well. Here the coffee beans, having already been roasted, are being pulverized in an ornate wooden mortar, while water for brewing is being heated in the open fire pit. The long-handled roasting ladle and spatula for stirring the roasting beans are neatly laid out on the far edge of the fire pit. From an early twentieth-century photograph.

Roasting Requirements

For orientation, let’s review what needs to take place during coffee roasting.

• The beans must be subjected to temperatures between 460°F and 530°F (240°C and 275°C). These temperatures can be considerably lower if the air around the beans is moving faster, as in hot-air or fluid-bed roasting apparatuses, or higher if the air is moving sluggishly, as it does in home gas ovens.

• The beans (or the air around them) must be kept moving to avoid uneven roasting or scorching.

• The roasting must be stopped at the right moment and the beans cooled promptly. (Prompt and effective cooling is an often overlooked but crucial element in coffee roasting.)

• Some provision must be made to vent the roasting smoke.

Here are some of the machines and methods for achieving these simple goals at home.

Overview of Methods and Machines

Roasting machines transfer heat to the beans in three fundamental ways.

• By convection: Beans are roasted by contact with rapidly moving hot air.

• By conductivity: Beans touch a hot surface.

• By radiation: Beans are bathed in heat from a hot surface or heat source.

In addition, the world may soon have its first genuine microwave coffee-roasting system, which works by a combination of microwaves and radiation.

Although no roasting method or machine works absolutely exclusively by any one of these three (or four) principles, they form a good starting point for understanding the differences in home-roasting technology and how they affect final cup character.

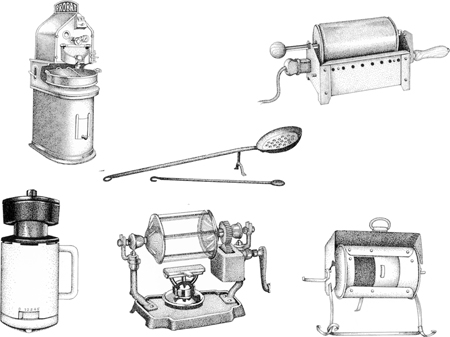

HOT-AIR OR FLUID-BED ROASTERS

Such devices roast coffee almost entirely by convection. Fast-moving currents of hot air surge through the beans, both heating and agitating them. The smallest and least expensive home-roasting devices work on this principle, as do hot-air corn poppers pressed into service as improvised coffee-roasting machines. These devices, which blow off roasting smoke and roast beans rapidly owing to an efficient transfer of heat, tend to produce a relatively bright, clean, high-toned cup. Both sweetness and acidity are accentuated, while body may be somewhat lighter than with coffee roasted by other methods. At this writing, hot-air roasters on the market include the Fresh Roast (here and here), the Brightway Caffé Rosto (here and here) and the Hearthware Gourmet Coffee Roaster (here and here).

The Sirocco home roaster, a small fluid-bed roaster manufactured in Germany and imported to the United States throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. Its cooling cycle is conveniently activated by a timer. A paper filter in the metal chaff collector atop the glass roasting chamber helps control roasting smoke. The Sirocco is no longer manufactured.

SLOWER CONVECTION ROASTERS

With Zach & Dani’s Gourmet Coffee Roaster (here and here), beans are roasted by convection but agitated mechanically by a screw in the middle of the roasting chamber. The gentler convection currents generated by the Zach & Dani’s device induce a slower, more deliberate pace of roasting than that induced by pure fluid-bed devices.

Improvised roasting in a home oven also qualifies as slow convection roasting. The beans, held in a perforated pan, are subject to slow-moving (in ordinary ovens) to moderately strong (in convection-option ovens) currents of hot air.

With the Zach & Dani’s device, with home ovens, and most likely with any other slow convection device that turns up on the market, the cup tends to be lower toned, with more muted acidity and sweetness, and body perhaps a bit heavier than with the fluid-bed method.

MICROWAVE ROASTERS

The latest wrinkle in home and small-batch roasting, Wave-Roast technology is an ingenious method for roasting coffee in microwave ovens. Beans are sealed inside a cardboard packet or cone that has an inner, heat-reflective lining. The beans are roasted by a combination of microwaves and heat radiated from the lining inside the cone, which converts microwaves to radiant heat. Most roasting smoke is trapped by the cardboard packet or cone, which acts as a filter. In the case of the more-sophisticated cone format, an attractive, rechargeable, battery-operated turntable rotates the cone inside the microwave, rolling it and thus tumbling the beans inside, assuring an even roast. In the case of the packets, the user (you) needs to agitate the beans by periodically opening the microwave and turning over the packet. The packets still produce a rather uneven roast.

At this writing the two roasting systems have not yet been released and are awaiting financial backers. I suspect that, short of further technological breakthroughs, the rather inconvenient packets will not enjoy much success on the market, although the clever cones may have a future.

Wave-Roast technology in general produces a low-toned, heavy-bodied cup, probably because the beans reabsorb moisture and roast smoke trapped inside the cone. Acidity, sweetness, and nuance are all muted; complexity is muddied. However, this technology comes into its own with dark-roast styles, which remain remarkably sweet and free of charred or burned flavor, deep and spicy rather than bitter or sharp.

DRUM ROASTERS

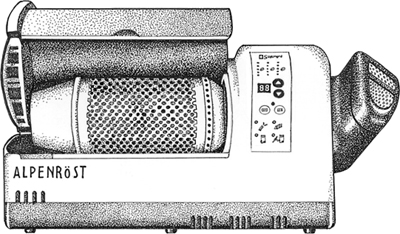

The most traditional of home-roasting technologies. Beans are mechanically agitated by tumbling inside a turning, perforated drum, while being roasted by a combination of direct radiation, conductivity, and gentle convection currents of hot air. At this writing two home drum roasters are available: the Swissmar Alpenrost (here) and the Hottop Bean Roaster (here).

The Alpenrost’s especially gentle convection currents and relatively slow roasting produce a round, low-toned, full-bodied cup with muted acidity and a roasty complexity concentrated toward the bottom rather than the top of the profile. With the Hottop Bean Roaster, brisker air movement and decisive cooling produce a classic cup with impressive clarity and balance, medium body, good sweetness, and crisp but not overbearing acidity.

STOVE-TOP DEVICES

This method roasts the beans entirely by radiation and direct contact with hot metal. Beans are enclosed inside a potlike metal chamber that sits atop the stove. A crank protruding from the top of the device turns metal rods or paddles inside the chamber, agitating the beans. Slow roasting and smoke working around the beans during roasting together tend to produce a round, low-toned cup with muted acidity and complexity concentrated at the bottom rather than the top of the profile.

At this writing, the stove-top options include the Aroma Pot ½-Pound Coffee Roaster, a manufactured-from-scratch device of traditional design, and the Whirley Pop (formerly the Felknor Theatre II) popcorn popper, which must be modified to accept a candy thermometer (here and here). At this writing, a version of the Whirley Pop already modified for coffee roasting is available for purchase on-line.

Which Is Best?

Choosing among these various roasting methods involves a trade-off among several factors: convenience (manufactured-from-scratch devices are easiest to use), volume of coffee roasted (drum roasters, stove-top devices, and oven methods all roast more coffee per batch than fluid-bed machines, microwave cones, or the Zach & Dani’s device), attitude toward roasting smoke (Zach & Dani’s produces the least smoke, the two drum roasters and stove-top devices by far the most), and preferences in cup (ranging from bright, clean, and crisp to low-toned and round). For some buyers, coffee romance and tradition may be an issue, with the old-fashioned looking Hottop drum roaster and the Aroma Pot stove-top roasters probably the leaders in this subjective arena. And then there is price: At this writing improvised equipment can cost as little as $30; drum roasters $280 to $580, with other options falling between these extremes.

A detailed summary of advantages and disadvantages of the various methods and devices is given in the “Quick Guide to Home-Roasting Options and Procedures”.

Fluidized-Bed Approaches

To repeat, fluidized-bed or hot-air roasting means that the beans are both roasted and agitated by a powerful current of hot air, much like hot-air corn poppers heat and agitate corn kernels.

MANUFACTURED-FROM-SCRATCH FLUID-BED ROASTERS

All three home fluid-bed roasters available at this writing work in approximately the same way and offer similar features.

• All roast a relatively small volume of green beans (three to four ounces) in about four to ten minutes using a powerful current of hot air to both move and roast the beans.

• All incorporate a timer that automatically triggers a cooling cycle by turning off the heating element while allowing the fan to continue driving room-temperature air up through the beans.

• All permit you to watch the beans during roasting and cooling.

• All permit you to either stop the roast or add time to it on the fly, while the beans are roasting.

• All incorporate a filter near the top of the roasting chamber to trap chaff, the tiny flakes of silver skin liberated by roasting, preventing them from floating around the kitchen and gathering in corners or incorporating themselves into sauces.

See here for details about the three currently available machines (currently $65 to $150), their capabilities, and advice for using them. See “Resources” for purchase information.

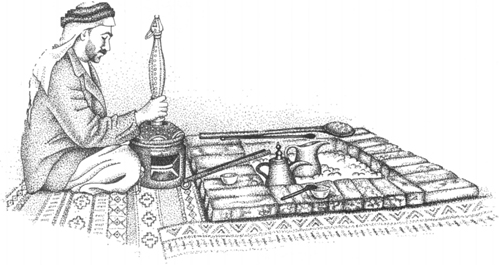

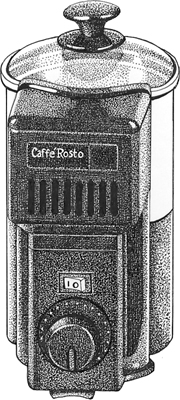

Caffé Rosto fluid-bed home roasting machine. As in competing fluid-bed devices, a current of heated air generated from the base of the machine both agitates and roasts the beans. The dial at the front of the unit controls the time of the roast and triggers an automatic cooling cycle. The cover at the top is glass and allows the user to peer down at the roasting beans. The chaff is collected in the unit protruding above the dial.

IMPROVISED FLUID-BED ROASTING WITH A HOT-AIR CORN POPPER

A very effective home coffee roaster can be improvised from the appropriate design of a hot-air corn popper. The ease with which the right popper can be modified to incorporate a candy/deep-fry thermometer as bean-temperature probe makes this option particularly attractive. Adding the thermometer is a simple (five-minute) modification that enables you to monitor the progress of the roast by the inner temperature of the beans rather than their outer color or appearance. See here. However, hot-air poppers require considerably more attention than their made-for-coffee fluid-bed counterparts. You need to unplug them to stop the roast, and you must cool the beans in a separate step.

Furthermore, hot-air corn poppers present particular issues in regard to chaff, the tiny paperlike flakes of coffee-fruit skin liberated by roasting. On the positive side, these devices, like store-bought fluid-bed roasting devices, blow the chaff up and out of the coffee beans while roasting them. On the negative side, the chaff blown out of the beans by hot-air poppers tends to float around the kitchen and complicate housekeeping rather than being trapped by a filter at the top of the machine as it is in dedicated home machines. The plastic hoods that fit over the top of hot-air poppers provide a fairly effective method for corralling the chaff, however. See here.

A more important chaff issue with hot-air poppers is the danger of combustion it poses with some designs. Use only poppers of the design recommended here for home coffee roasting, in other words, those machines that introduce the hot air from the sides of the popping/roasting chamber and circulate the beans in a circular pattern at the bottom of the roast/popping chamber. Do not use designs in which the hot air issues from grill-covered openings or slots on the bottom floor of the popping/roasting chamber. With such styles fragments of the roasting chaff can settle into the base of the popper, collect around the heating elements, and eventually cause the device to ignite.

Also keep in mind that if you use any unmodified hot-air popper for coffee roasting you void its warranty by employing it for a purpose other than the one for which it was originally intended. The recommended designs are sturdy as well as inexpensive, however, and stand up well when used to produce light through medium to Viennese roasts. If you enjoy darker roasts—espresso through very dark (dark French or Italian) styles—you should opt for a store-bought roasting machine.

Complete instructions for using a hot-air corn popper to roast coffee appear here, together with directions for adding a candy thermometer should you wish to. See “Resources” for information on buying hot-air poppers and thermometers.

Zach & Dani’s Gourmet Coffee Roaster

Zach & Dani’s new little roasting machine is unique among currently available home-roasting machines in two respects. First, it is a hybrid design that roasts the beans by means of a convection current of hot air but agitates them mechanically by means of a screw inside the roasting chamber that majestically stirs, lifts, and drops the beans. Second, it all but eliminates troublesome roasting smoke by means of a catalytic converter. No other home-roasting device employs such an effective way of reducing or diverting the roasting smoke.

The flow of hot air in the Zach & Dani’s machine is less intense in both temperature and velocity than that generated by any of the fluid-bed devices, which means it roasts more slowly: twenty to thirty minutes, counting cooling time. On the other hand, it roasts a bit more coffee than any of the pure fluid-bed units. The slower roast time produces a cleanly articulated cup profile but one that is lower-toned and less acidy and sweet than the cup produced by faster-roasting fluid-bed devices like the Fresh Roast or the Hearthware Gourmet.

Controls for the Zach & Dani’s machine are electronic rather than mechanical: You push buttons rather than twist a spring-loaded dial to control time of roast, and watch a digital readout as the roast counts down toward conclusion. The controls also allow you to prolong the roast as it is happening by adding time on the fly. Taken together, these features make the controls on the Zach & Dani’s machine among the most flexible and sophisticated available on currently available home-roasting machines.

In price the Zach & Dani’s (around $200 with grinder and green beans) falls between the simple little fluid-bed devices (around $70 to $150) and the larger-capacity, high-end drum roasters (currently around $280 to $580). See here for an illustration of the Zach & Dani’s device and here for details and some advice on using it. See “Resources” for purchase information.

Home Drum Roasters

So far the fledgling home-roasting industry has given us two small drum-style roasters for home use: the Swissmar Alpenrost and the Hottop Coffee Roaster. Both roast coffee much like traditional professional drum roasters do, making them attractive choices for coffee romantics.

They also roast eight or nine ounces of green beans per batch, considerably more than other dedicated home-roasting devices. On the other hand, they take a lot longer to roast each batch than the little fluid-bed machines do, and they produce a lot more roasting smoke, simply because they roast a lot more beans than competing devices. Furthermore, they also cost a good deal more than any of the smaller fluid-bed devices or the Zach & Dani’s unit: around $280 for the Alpenrost and $580 for the Hottop. Finally, like the Zach & Dani’s machine but unlike the compact little fluid-bed roasters, they are countertop space hogs.

Although both use similar technologies to roast about the same amount of coffee in about the same amount of time, and incorporate similar digital controls, they differ in several respects. The Hottop incorporates a window for observing the changing color of the beans, whereas the Alpenrost is entirely enclosed (you control the degree of roast by setting a timer and by trial and error or by listening to the crack and smelling the smoke). The Hottop dumps the beans into a pan outside the roasting chamber for cooling, a technical advantage; the Alpenrost cools the beans inside the roasting chamber with a current of room-temperature air. The Hottop is more traditional looking, the Alpenrost is rather sleekly high-tech. The exterior surfaces of the Alpenrost stay relatively cool to the touch during roasting, a unique safety feature among the current crop of home-roasting machines. By contrast, the exterior of the Hottop becomes very, very hot, although its manufacturers are promising an insulated version of their machine shortly.

See the illustration below of the Alpenrost, here for a picture of the current Hottop model, and here for details on both of these devices. See “Resources” for ordering and availability.

Swissmar Alpenrost home drum-roasting machine. Coffee is roasted inside the perforated drum revealed by the lifted hood, with heat provided by electric elements concealed beneath the drum. During roasting the hood is lowered over the drum, concentrating heat from the electric elements inside the machine and maintaining a safe surface temperature on the outside. The protruding component on the right can be turned to direct roasting smoke toward an exhaust fan or open window.

Microwave-Oven Roasting

Roasting coffee by simply microwaving the beans does not work. However, some persistent and ingenious technicians have developed a microwave coffee-roasting method that does work—remarkably well.

It should be mentioned that at this writing another organization calling itself Smiles Coffee is distributing preroasted coffee in microwave packages. Essentially you heat the already roasted coffee in the microwave to give the impression of fresh roasting. Hopefully this bizarre parody of home roasting will be off the market by the time these words appear in print, but if not, don’t be taken in.

On the other hand, technicians behind a system called Wave Roast have mastered the challenge of actually roasting coffee in a microwave oven. The trick is a lining inside the microwave packet that converts some of the microwave energy into radiant heat. The radiant heat roasts the outside of the beans while the remaining microwave energy roasts the inside.

At this writing it is not clear which of the several trial versions of Wave-Roast products finally will make it to market. The simplest form of the Wave Roast system involves packets of green coffee ready to be popped into the oven and roasted. The sealed but porous cardboard packet absorbs some roasting smoke and contains the rest, releasing only a little puff when the packet is opened to liberate the roasted beans. In order to prevent the beans from roasting unevenly, however, you need to wait for the first popping sounds that signal the beginning of the roast, then begin opening the oven and flipping the (rather hot) packet. The beans still roast unevenly, and the result is a cup much like the one achieved by oven roasting: either complex and layered or muddy and confusing, depending on your point of view.

More complex versions of the Wave Roast system eliminate the problem of uneven roast by sealing the beans inside a cone that is rapidly rotated inside a microwave oven by a roller device. One prototype (illustrated here) rotates the cone inside the microwave oven by means of a cute little rechargeable batter-operated roller device. Another tentative design involves a small, dedicated microwave with the roller device built into the microwave.

Assuming that the final released product works as well as the demonstration versions I reviewed for this book, the cone system could constitute the world’s easiest coffee-roasting method. And, although the coffee it produces is a bit flat and muddy at medium through medium-dark roast levels, at darker roast levels Wave Roast cone coffee is impressive: sweeter, deeper, and more complex than dark roasts produced by most other methods.

However, it remains to be seen whether investors will be willing to commit the money necessary to bring this system to market. And, if they are, whether consumers are willing to pick up the cost added to the green beans by the packets and cones: Two ounces of green beans inside a packet may sell for an average of one dollar, for example, and inside a cone for two or three dollars, versus about fifty cents if the same beans were bought through normal channels. I hope that some buyers will pop for the cones, at least, enough of them to keep this interesting product on the market and reward the ingenuity of its creators.

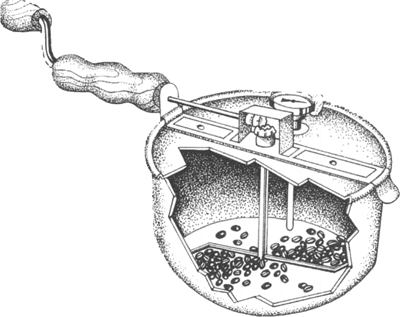

Stove-top Roasting

Stirring the beans in a pan over heat undoubtedly was the earliest method of coffee roasting, a method that is still practiced in many parts of the world. In Ethiopia and Eritrea the roasting device of choice is a shallow metal pan that looks much like a wok and sits atop a charcoal fire. In rural Latin America and Indonesia roasting is typically performed using a large, round-bottomed earthenware bowl that accumulates a shiny patina of coffee oils.

Although it is possible to do a passable roast in similar fashion at home by stirring beans in a wok or cast-iron skillet on a range top, I recommend instead stove-top methods that help raise the heat around the beans by keeping them covered during roasting. This is the principle behind the little devices that, until World War II, were the roasting method of choice in much of continental Europe. These picturesque little appliances look like heavy covered saucepans with cranks protruding from the top. You put the beans into the interior of the device through a little door and stir the beans during roasting by turning the crank.

STOVE-TOP ROASTING WITH THE AROMA POT ½-POUND COFFEE ROASTER

The sturdy Aroma Pot revives this time-honored design. Aside from being fabricated in stainless steel rather than cast iron, the Aroma Pot pretty much duplicates a typical stove-top roaster of the nineteenth or early twentieth centuries.

Which is unfortunate, perhaps, because this traditional design has some problems. The optimum roasting temperature inside the pot must be determined by very rough trial and error, for example. You put the beans into the interior of the pot through a tiny door. It is possible to open the door during roasting to check the developing color of the beans, but awkward. The closed design of the roaster makes it difficult to impossible to repair the vanes that push the beans around should they lose alignment owing to jamming on wayward beans. Most important, the vanes essentially push the beans around in a pile rather than mixing or agitating them, which means you need to lift the roaster occasionally and shake it to make sure the same beans do not remain rolling around at the bottom of the pile, overroasting.

Nevertheless, those who don’t mind standing over the stove and turning a crank for several minutes, plus administering a bonus shake now and then, may enjoy the Aroma Pot’s large capacity and simple, nostalgic design.

The Aroma Pot with a large kit of accessories sells for $140 via the Internet. See “Resources” for purchase information and here for more advice and details on using the Aroma Pot.

ROASTING WITH THE WHIRLEY POP CORN POPPER

A second option for stove-top coffee roasting is an old-fashioned corn popper, the kind that looks like a covered saucepan with a crank protruding from the top or side. The crank turns a pair of wire vanes that rotate just above the bottom of the pan, agitating the corn kernels (in our case the coffee beans) to keep them from scorching.

There are several stove-top poppers on the market at this writing, but the one that I find works best for coffee roasting is the Whirley Pop (around $25). The suggestions and instructions here and here are all based on my experience with the Whirley Pop.

Do not buy the somewhat similar West Bend electric countertop Stir Crazy corn popper to roast coffee, by the way. It does not generate quite enough heat and ends up baking the coffee rather than roasting it.

Whirley pop stove-top corn popper with candy thermometer installed to permit monitoring of roast-chamber temperature.

Although the manufacturer obviously designed the Whirley Pop to pop corn rather than roast coffee, it actually turns out to be superior to traditional stove-top coffee roasters like the Aroma Pot in two respects. First, it enables you to easily watch the beans while they roast. With the Whirley Pop, half of the lid opens and folds back, making dumping the beans and keeping an eye on them while they’re roasting relatively simple. A second advantage to the Whirley Pop is the ease with which it can be modified to accept an inexpensive candy thermometer (around $5). The candy thermometer provides rough readings of the temperature inside the popper, allowing you to safely and decisively manipulate burner settings to maintain optimum temperatures during the roast. Adding a candy thermometer to the Whirley Pop is a very easy procedure, requiring only a drill, a single drill bit, some odd nuts and washers as spacers, and about two minutes of elementary fiddling. Even better, at this writing one Internet supplier currently offers the Whirley Pop already modified with the thermometer (see “Resources”).

A caution: The body of the Whirley Pop popper is constructed of aluminum, and like all light-bodied aluminum cookware it will melt if abandoned over high heat for an extended period of time. Not that the Whirley Pop is shabbily made. It is very well made and, used following the instructions in this book, will last through years of coffee roasting. But for those who read quickly or are inattentive I offer the following warning: Never use a stove-top corn popper on burner settings above medium (with an electric range) or low (with a gas range), and never leave the popper unattended with the heat on.

Given that warning, I find the Whirley Pop popper does an excellent job, particularly with darker roasts. I’ve cupped coffees I’ve roasted in it against equally fresh, professionally roasted coffees from the same crop, and found the Whirley Pop–roasted beans often better than their professionally roasted counterparts, and at worst only slightly inferior in acidity and aroma. The edge in home-roasted freshness will completely outweigh any such slight deficiencies. And the Whirley Pop roasts a half-pound of coffee per session, so you needn’t hover over the stove cranking all that often.

Detailed instructions for using the Whirley Pop to roast coffee appear here with illustrations here and here. If you have trouble finding the Whirley Pop see “Resources” for ordering information, including a source for a version with the thermometer already installed.

Roasting in Gas and Convection Ovens

Three kinds of ovens can be used to roast coffee using improvised methods: most ordinary kitchen gas range ovens, electric range ovens offering a combination of both convection and conventional thermal operation, and some electric convection ovens. Microwave ovens only can be used to roast coffee with Wave-Roast packets or cones (See here and here). Toaster ovens and conventional electric ovens without convection should not be used to roast coffee; you will be disappointed by the results.

ROASTING IN A GAS OVEN

A single layer of coffee beans spread densely over a perforated surface, say a perforated baking pan, will permit the gentle air currents moving inside gas ovens to flow through the beans and roast them fairly evenly.

Some beans may roast more darkly than others, but (this will sound like heresy to many professionals) I’m not sure that matters. In fact, the added complexity achieved by mixing beans brought to slightly varying degrees of roast in the same cup often dramatically enhances flavor. During my experiments with gas ovens I’ve turned out some rather funky-looking roasts that have tasted superb, with a wide, deep flavor palette that no professional roast I’ve tasted has ever matched.

It is true, however, that achieving an acceptable roast in a given gas oven usually requires patient experimentation with that particular appliance. And precise control of roast style can be difficult under any circumstances. This means that gas-oven roasting may not be a good idea for those who prefer roast styles at the very light or the very dark ends of the spectrum, since with a very light roast some beans may hardly be roasted at all, while at the dark end some beans may end up literally burned. But for those who prefer medium through moderately dark styles, gas-oven roasting can produce a remarkably rich, complex cup, a gustatory surprise that can only be experienced through home roasting.

Monitoring the progress of the roast also can be tricky with a kitchen oven, since the smoke and crackling that signal the onset of pyrolysis are muted by the barrier of the oven door, and you may need to use a flashlight to check the color of the beans as you peek inside.

Nevertheless, the flexible, precise control of temperature provided by gas ovens is an advantage, as are the venting arrangements, which usually carry the roasting smoke outside. Most gas ovens will roast up to a pound or more of coffee at a time, and again, the flavor of oven-roasted coffee can be startlingly good.

Detailed, illustrated instructions for gas-oven roasting appear here.

ROASTING IN AN ELECTRIC CONVECTION OVEN

Ordinary electric ovens do not generate sufficient air movement to properly roast coffee evenly, but many convection ovens, which bake by means of rapidly moving currents of heated air, can be pressed into service as ad hoc coffee roasters.

The majority of convection ovens manufactured today have a maximum heat setting of 450°F/232°C. This temperature is barely enough to bring coffee beans to a proper roast. Smaller convection ovens, those that resemble toaster ovens, typically have maximum settings lower than 450°F/230°C and cannot be used to roast coffee successfully. Those few ovens built with a maximum setting of 500°F/260°C or higher usually will produce a good, if mild-tasting, roast.

If you own a convection oven, test its heat output with an oven thermometer before attempting to use it to roast coffee. Instructions for this simple evaluation are given here, along with detailed instructions for convection-oven roasting. If you decide to purchase a convection oven especially for use in roasting coffee, look for a model that provides a maximum heat setting of 500°F/260°C or higher and permits easy visual inspection of the roasting beans through nontinted glass.

Even those convection ovens that generate reasonable roast temperatures tend to produce long, slow roasts of eighteen to twenty-five minutes. This deliberate pace yields a rather mild-tasting coffee with low acidity and muted aroma in medium roasts and a rather sweet, gentle profile in dark roasts. Some coffee drinkers, particularly those who take their coffee black and unsweetened, may prefer the taste of coffee roasted in a convection oven to the more complex, acidy taste of coffees roasted by other methods. And those few Americans who sip their espresso straight, without frothed milk, also may find the smooth flavor profile of convection-oven dark roasts attractive. However, I suspect that the majority of American coffee fanciers will find convection-oven coffee bland.

OVENS WITH COMBINED THERMAL AND CONVECTION FUNCTIONS

Some sophisticated electric ovens now convert from conventional operation to convection mode at the touch of a button. Such ovens also permit simultaneous use of both conventional and convection functions. For coffee roasting the combination setting works best. Complete instructions for roasting with these versatile devices is included with the instructions for general oven roasting here.

Higher-Priced Professional Equipment

For the serious aficionado, professional sample and small shop roasters may offer an interesting alternative despite their high price. Small professional roasting machines are usually divided into two categories: sample roasters, which typically roast anywhere from four ounces to one pound of coffee per batch, and tabletop roasters, which roast from one pound up to anywhere from five to seven pounds at a time.

In fact, many of the home-roasting devices described here do an excellent job of sample roasting, especially sample roasting for green coffee evaluation. In particular, the fast-roasting Fresh Roast and Hearthware Gourmet fluid-bed machines produce a style of cup ideal for evaluating green coffees: clearly articulated without distracting smoky or roasty notes. A hot-air corn popper with thermometer installed as bean temperature probe (here) also works very well as a sample roaster for evaluation of green coffee, particularly because the thermometer makes it possible to achieve considerably more consistency in degree of roast than is possible with roasting equipment not equipped with thermometers or heat probes.

Nevertheless, the classic professional drum sample roaster, constructed of cast iron and brass and virtually indestructible, has many advantages over cheaper home equipment, including style, flexible control of heat and air flow, and, above all, durability. These handsome apparatuses start at around $4,200 for a “one-barrel” or single-cylinder model. See here for an illustration of the simplest and still most widely used style, most closely associated with the name Jabez Burns. Sample roasters from Probat, CoffeePER, and Quantik go beyond the Burns design by reproducing most of the features of the traditional full-scale drum-roasting machine (see diagram here). Unlike the Jabez Burns-style machines, the Probat, CoffeePER, and Quantik roasters enable you to control the velocity of airflow through the roasting chamber as well as the degree of heat applied to the coffee. The Quantik, manufactured in Colombia, adds to the basic drum-roaster design a heat probe inside the roasting drum (though not inside the bed of roasting beans) with digital readout. A heat probe that registers the temperature of the roasting beans themselves can be added as an option to the CoffeePER sample roaster. Both the Probat one-barrel and the Quantik run on ordinary household current. Models from other manufacturers typically require natural gas or a 220-volt connection.

Tabletop roasters, which roast a pound or more per batch, offer a considerable range of choice, too great a range to outline here. There are automated fluid-bed designs, like the simple, rugged, and relatively inexpensive one-pound-batch Sonofresco ($4,000); standard-configuration drum-style roasters for anywhere from $4,000 to $8,000, depending on features and batch size; and technically outstanding but awkwardly designed fluid-bed machines from Sivitz Coffee ($2,000 to $10,000). All run on natural gas, propane, or 220-volt current. See “Resources” for details.

Style of Roast

Different roasts for different folks. Some prefer an extremely light, brisk, almost tealike roast. Others prefer a dark, oily, nearly burned style. Between these two extremes the classicists range themselves, from those who prefer sweetly acidy medium roasts to those who enjoy a rich but balanced espresso. To review how these roast styles work out in terms of taste and terminology see the chart.

The main trick in home coffee roasting is figuring out where to stop to achieve the roast style you prefer. One way to translate your personal taste in roast into home practice is to find a store that sells a whole-bean coffee roasted in a style you like, buy some, and attempt to duplicate it at home. However, those who want to fully explore the nuances of home roasting may prefer to experiment and taste, even carry out systematic tests to determine their preferences in roast, and along the way learn in detail about green coffees and roast styles. See here near the end of this chapter for suggestions on how to carry out such experiments.

Controlling the Roast

The following section offers an orientation to the issues involved in controlling degree or darkness of roast. Detailed and sequential instructions for various specific home-roasting procedures are given in the section following this chapter.

Whichever roasting method you use or roast style you prefer, you will eventually develop a feel for timing through experience with your particular method and equipment. Again, only our general unfamiliarity with roasting technique makes these instructions any more intimidating than directions for broiling a steak or preparing an egg over easy.

CONTROLLING THE ROAST BY TIME, TRIAL, AND ERROR

One way to control degree of roast, particularly with store-bought roasting machines, is simply to set the timer or other control to the setting the manufacturer recommends for a “medium” roast, taste what you get, and begin adding or subtracting time accordingly. If the roast tastes too bright, acidy, or grainy, add time to make your next roast longer. If the cup is too pungent, bitter, or burned tasting, or if it seems too dull or low-toned, shorten the next roast to brighten and lighten the cup.

The problem with the trial-and-error approach is that every green coffee roasts somewhat differently, so you may need to go through the same procedure for each new green coffee you add to your repertory.

Also, keep in mind that whatever time range you come up with is relevant to your roasting machine and method only and not to other technologies and methods. Don’t be fooled by the illusion that there is some absolute “right” time for a good roast. Some small fluid-bed machines do a splendid roast in three or four minutes. If you tried to roast coffee in three or four minutes in a large drum roaster you would utterly destroy the coffee. Depending on the nature of the roasting equipment, a “good roast” can be achieved in as few as three minutes to as long as thirty minutes.

CONTROLLING THE ROAST BY SIGHT, SOUND, AND SMELL

The best and most versatile approach to controlling degree of roast is using your senses to follow the drama of the roast and ending it when the drama reaches the moment that produces the cup you prefer.

Recall that roasting coffee beans communicate to us by sight (gradually changing color from light brown to almost black), by sound (the “first crack” and “second crack”), and by smell (volume and scent of the roasting smoke). Although both color and smoke are helpful indicators of roast development, the sound of the two cracks are the most telling and dramatic of indicators.

Here are the acts in the roasting drama and what they mean for roast flavor. For more detail see the chart.

Overture. As the roast begins, beans silently turn brownish yellow and smell like bread or burlap. Never stop the roast at this point because the coffee has not yet started to roast.

First Act. Beans turn light brown, begin to smoke slightly, and start smelling more like coffee than bread. Most important, the beans begin to produce a rather loud popping or crackling sound. This is the onset of the “first crack,” the moment the roast transformation begins.

Second Act. Beans turn light to medium brown and the popping of the first crack reaches a crescendo. Stop the roast here, in the middle of the first crack, for a cup that is acidy and sweet but also grainlike and tealike in flavor.

Third Act. Popping gradually trails away in frequency. Beans turn medium brown. As the popping stops completely the roast smoke may begin to darken slightly and smell sweeter and fuller. Stop the roast here, in the lull at the end of the first crack, if you want a bright, acidy, high-toned, classic “breakfast”-style medium-roast cup.

Fourth Act. A new, more subdued crackling begins. If the first crack sounds like corn popping, the second crack sounds more like paper being crinkled. Immediately before the second crack begins, the roast smoke increases in volume and becomes sweeter and more pungent. Stop the roast here, just at the beginning of the second crack, if you prefer a round, sweet, but still bright cup of the kind roasters often call “full city” or “Viennese.”

Fifth Act. From here on, we enter the realm of “dark” roasts. The crackling or crinkling of the second crack becomes almost continuous. The smoke thickens and becomes dark and intensely pungent-smelling. The beans turn dark brown in color. Stop the roast here, just as the second crack rises toward a crescendo, if you enjoy a balanced dark-roast cup without acidity, pungent yet sweet, full-bodied, with a roasty but not burned flavor.

Denouement. As the second crack reaches a frenzied climax and a dark, heavy, sweet-smelling smoke fills the air, we reach the end of the roast story. Go no further. Stop the roast here if you enjoy the ultimate dark roast, the kind often called “dark French”: burned-tasting, thin-bodied, with only a vague overlay of sweetness and little nuance.

The Story Is Over. After this final point in the roast has been reached, the coffee’s aromatics have gone up in smoke entirely, the beans are completely black, the roasting chamber is oily, the neighbors have called the fire department, and the coffee, if you cared to sample it, would taste literally like burned rubber.

An Obvious Warning. Never abandon roasting beans if your roasting device lacks an automatic cool-down cycle or timer. This is a particularly important caution with the stove-top and improvised hot-air popper methods. With these approaches you should not even leave the room until the heat is off and the session is over. If coffee beans are abandoned inside a hot roasting chamber long enough they turn into semiflammable charcoal, not nearly as dangerous as many foods become when left over heat but flammable nevertheless.

CONTROLLING THE ROAST BY INSTRUMENT

In this case the “instrument” simply means a heat probe or thermometer arranged so that it is completely surrounded by the beans as they roast. The thermometer measures the approximate internal temperature of the mass of roasting beans, or “pseudo bean temperature” in professional roasting jargon. Since internal bean temperature is a measurement of roast style (see the chart), the reading on the heat probe will tell the operator when to conclude a roast so as to achieve a given style.

Unfortunately, the instrument approach is difficult to realize with most home-roasting methods. Inexpensive metal thermometers intended for candy making and deep frying can be used to measure bean temperature in hot-air poppers by means of a very simple, two-minute modification (See here). But with most other home-roasting setups the physical arrangements of the machine or method make it difficult to get the thermometer and beans into sustained and meaningful contact.

Concluding and Cooling the Roast

Cooling the hot beans rapidly and efficiently is one of the most important steps in home roasting, since coffee continues to roast from its own internal heat long after it has been removed from external heat. Coffee that is allowed to coast down to room temperature of its own accord will taste dramatically inferior to coffee that is promptly and decisively cooled.

COOLING THE ROAST WITH BUILT-FROM-SCRATCH EQUIPMENT

All dedicated, store-bought home-roasting devices cool the roast by circulating currents of room-temperature air through the hot beans. In all cases except the Hottop Coffee Roaster the cooling is performed inside the same chamber where the roasting occurred, which means the air is cooling both beans and chamber—a lousy idea technically; but given the small volume of beans being roasted it does not seem to compromise flavor.

IMPROVISED COOLING

Most hobbyist roasters who use improvised equipment prepare small batches of a few ounces of beans per session, so simply dumping the beans into a colander and stirring or tossing them is sufficient cooling procedure. This procedure is best performed over a sink or out-of-doors, so that the toasting chaff that floats free of the beans will not litter the kitchen.

If you have a kitchen range with an exhaust fan built into the stove-top, the kind that evacuates kitchen odors downward, you are in great luck. Simply place the colander full of hot beans over the exhaust fan and swirl or toss them. They will be warm to the touch within a minute or two.

Many exhaust fans located in hoods above kitchen ranges also can be used to air-quench beans. Simply dump the hot beans into a colander and hold the colander flush up against the filter or grill that covers the fan. (In the unlikely event the fan has no grill or covering, be careful not to touch the whirling fan blades!) The fan pulls air through the holes in the colander and up through the hot beans, typically cooling them within a couple of minutes.

You also can initiate the cooling process by water quenching, just as professional roasters often do. A pump- or trigger-spray dispenser, the kind with a nozzle that adjusts to a fine mist (illustrated here), works very well. Simply fill the dispenser with distilled or filtered water, and while stirring or tossing the hot beans, subject them to a few seconds of light, intermittent mist. You must perform this procedure immediately after roasting and be careful not to overdo the application of water by spraying too long or by using too coarse a spray. Complete instructions for water quenching are given here.

Why water quench? There are two reasons. If you roast a half-pound or more of coffee at a time using improvised methods you probably should water quench to hasten the cooling process, since the more coffee you roast the slower it cools. Second, I find that coffee water quenched with care and restraint tastes better than coffee that has been cooled simply by stirring or tossing.

But if you do water quench, don’t overdo it. Follow my instructions here with care and sensitivity. And, obviously, don’t spritz the beans while they are still inside an electric appliance. Liberate them and then apply the mist of water.

THE FREEZER STRATEGY

Another favorite cooling strategy among home roasters is sticking the hot beans into a freezer immediately after roasting. Make sure you take them out again well before they freeze, however. Like water quenching, freezer quenching shortens cooling and helps preserve aromatics.

Getting Out the Chaff

Chaff is paperlike stuff that appears as though by magic during roasting, apparently materializing straight out of the roasting beans. In fact these little brown flakes are fragments of the innermost skin (the silver skin) of the coffee fruit that still cling to the beans after processing has been completed. Roasting causes these bits of skin to lift off the bean.

With dedicated, manufactured-from-scratch home equipment, chaff is no problem. All you need to do is remember to follow the instructions that come with your roaster and empty the chaff receptacle after every roast batch.

CHAFF REMOVAL WITH IMPROVISED EQUIPMENT

With improvised equipment, chaff presents contrasting issues depending on which roasting method you employ.

With hot-air corn poppers the chaff will be blown free of the seething beans during roasting, creating one kind of problem: how to keep it from wafting around the kitchen and landing on the counter or in the soup. Solutions for this problem appear with the roasting instructions following this chapter.

If, on the other hand, you are using any other home-roasting method the chaff will remain mixed with the beans, presenting the problem of getting it out. Fortunately, the same tossing or stirring process that facilitates cooling will rid the beans of most of their chaff. Any amount that is left in the beans will have little to no effect on flavor. Only in very large amounts can chaff be detected at all, then only as a slight muting or dulling of the cup.

In fact, probably the single most important piece of advice to improvising home roasters in regard to chaff is to not become obsessive about it. However, advice for dealing with the occasional stubbornly chaff-retentive coffee is given here.

The Troublesome Roasting Smoke

Finally, there is the roasting smoke. The good news is, it smells wonderful while you’re roasting. To some people it still smells wonderful two hours later, but to most of us it turns stale and cloying.

Of the current crop of manufactured-from-scratch home-roasting devices, only one offers a solution to roaster smoke: Zach & Dani’s Gourmet Coffee Roaster, with its smoke-thinning catalytic converter. All of the others require positioning either under a kitchen exhaust fan or next to an open window. They also can be used on a porch or balcony in clement weather, much like the Neapolitans and their abbrustulaturi celebrated by Eduardo De Filippo in Chapter 1. Don’t try to use them outside in temperatures below 50°F/10°C, however. The cold may prevent them from achieving effective roast temperatures.

Improvising home roasters who use gas ovens and built-in convection ovens are in luck; typically ovens in kitchen ranges are well vented and carry the smoke outside. However, improvising roasters using hot-air poppers, stove-top apparatuses, or countertop convection ovens also need either a good kitchen exhaust fan or a partly open window.

Those who like light-to-medium roast styles will have less to be concerned about than those who prefer darker roasts, since beans produce their most voluminous and intense smoke as they are carried to darker styles. Also, keep in mind that the more coffee you roast the more roasting smoke you produce. Thus, those who roast a few ounces of coffee to a medium roast will have little to be concerned about. Those who roast a half-pound of coffee to a very dark “French” roast will need to make careful ventilating arrangements to avoid setting off the smoke alarm.

After-Roast Resting

Resting doesn’t refer to what you yourself do after several minutes of vigilant home roasting but to what you do to the coffee. Freshly roasted beans are at their best anywhere from four hours to a day after roasting. Coffee fresh out of the roaster is superb, however, so don’t deprive yourself of enjoying it owing to gourmet obsessiveness.

Systematic Roasting: Controlling Variables

Most home roasters rely on trial and error and accumulated experience to achieve the roast style they enjoy, with excellent results. Others relish the challenge of precision based on system and record keeping. A methodical approach also may be the best way to achieve intimate knowledge of roast and coffee taste.

Informative experiment depends on control of four roasting variables:

• the amount of coffee roasted

• the temperature inside the roasting chamber

• the identity of the green coffee (in particular its approximate moisture content)

• the time or duration of the roast.

With most home-roasting devices the first two variables are controlled for you and cannot be adjusted. The second two variables are controllable in all circumstances, however, and constitute a good starting point for home-roasting experiment.

Of course this list of variables assumes that you are using the same roasting method or technology (i.e., gas oven, hot-air corn popper, etc.) for all of your experiments. The taste of a given roast style gotten by different technologies will vary, sometimes greatly.

Like any good investigator, you need to control three of the four variables while systematically varying the fourth, meanwhile keeping careful record of the results. A sample form for recording notes on your roasting experiments appears here.

Again, the two variables with which you are most likely to experiment are the identity of the green coffee and the length of time the roast is sustained. In other words, if you want to find out how two green coffees or blends of green coffees compare when brought to roughly the same style of roast you should alter the identity of the coffees themselves while keeping the other three variables, including the approximate elapsed time of roast, constant. If, on the other hand, you are interested in how a single given coffee tastes at different styles or degrees of roast, obviously you should use the same green coffee or blend of coffees but increase the length of time you sustain the roast in regular, recorded increments.

THE FOUR VARIABLES IN DETAIL

Here is a closer look at the four variables, again assuming that the method or equipment you are using for your experiments remains constant.

Amount of Coffee You Roast. The more coffee you roast the slower the beans respond to heat, so if you vary the amount of coffee you roast from session to session you will not be able to make any meaningful connection between how long you have roasted a coffee and how it ends up looking and tasting. Fluid-bed roasters and hot-air corn poppers are particularly demanding in regard to how much coffee you roast, since they will not operate properly without the correct weight of beans to balance the upward thrust of the hot air. With oven and stove-top methods consistency in amount of coffee roasted per session is less important, particularly if you’re the impulsive type who simply “roasts them until they’re brown.” But anyone carrying on systematic experiments should control this variable carefully.

Measuring green beans by weight on a kitchen food scale is more reliable than measuring them by volume, since beans differ in density. However, volume will work well enough in most home-roasting contexts.

Temperature Inside the Roasting Chamber. For professional roasters who attempt to subtly influence the flavor profile of the coffee during roasting this is the most important variable of all. Unfortunately, the simple technology available to home roasters makes sophisticated control of roasting-chamber temperature difficult if not impossible.

With most home-roasting equipment, store-bought or improvised, you have no choice about roast-chamber temperature. With fluid-bed roasters and hot-air corn poppers the temperature is built in. Stove-top roasting affords very rudimentary control. With convection ovens you can change temperature settings, but usually the only practical setting for coffee roasting is the highest available, so the question is moot. Only gas-oven roasting enables you to control roast-chamber temperature deliberately and measurably.

Consequently, the best approach for most home-roasting methods is to maintain the same temperature throughout your sessions and influence style or degree of roast simply by varying the length of time you keep the beans in the roasting chamber. If your method allows you a choice of roast temperature (essentially, if you are using either a gas oven or a stove-top roaster fitted with a candy thermometer), start with a temperature of about 500°F/260°C. If you have to wait longer than eight or ten minutes for the onset of pyrolysis, signaled by coffee-smelling smoke and crackling sounds, raise the temperature to 520°F/270°C and try again. On the other hand, if pyrolysis sets in sooner than four minutes into the roast, lower your beginning temperature to about 475°F/245°C for your next session. Never attempt to roast coffee at temperatures lower than about 460°F/238°C. With stove-top poppers never go higher than 520°F/270°C; with gas ovens, never higher than about 550°F/290°C. Once you settle on a workable temperature, which induces pyrolysis in less than eight or ten minutes but no sooner than three or four, stay with it until you learn a bit about the roasting process.

Identity of the Green Coffee. Green beans all roast slightly differently; some roast very differently. If you are carrying out systematic experiments to learn about roast flavors or styles, control this variable by using the same crop or blend of green beans for every session in your series of experiments.

The moister and denser the bean the slower it roasts and the higher the temperatures it will absorb on the way to the same roast style. Professional roasters often measure bean density and adjust roast-chamber temperatures accordingly. More intuitive professionals may compensate for differences among green coffees by regulating roast temperatures based on the history of their experience with a particular coffee.

Most home roasters can do neither, since the majority of home-roasting methods don’t allow us to make adjustments to roast-chamber temperature for any reason. All we can do is be aware of differences in how quickly a given coffee may roast, and make very rough corresponding adjustments in our roast procedure. The following generalizations may be helpful, although in the context of home roasting only the last point concerning decaffeinated beans is of dramatic significance.

• Fresh beans less than a year old (new crop) from high growing areas (the best Guatemalan, Costa Rican, Kenyan, and Colombian coffees in particular) tend to be hard and moist, and may roast relatively slowly.

• Sumatran and Sulawesian coffees, which are often high in moisture content, may require longer roasting times or higher roast temperatures than those of other origins. Monsooned and aged coffees also tend to roast unpredictably or sluggishly.

• Older beans (a year or more since processing, called “past crop,” plus some deliberately aged coffees) and beans from lower growing areas may roast faster, sometimes dramatically faster, than newer-crop, higher-grown coffees.

• Decaffeinated coffees can be very sensitive and may roast dramatically faster (15 to 25 percent) than fresh hard-bean coffees. With decaffeinated beans you should be prepared from the first sign of roasting smoke and crackling to check the appearance of the beans obsessively.

Time or Duration of the Roast. This is the most easily controlled and most important variable in home roasting. If you carefully control the other three variables and use the same roasting method from session to session, you should be able to correlate the time of the roast fairly accurately with the final color, style, and taste of the roasted beans. You can’t achieve absolute consistency, since ambient temperature and atmospheric pressure both affect roasting time, but you can come close.

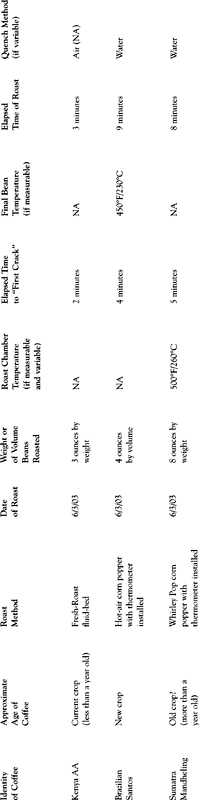

RECORD KEEPING

Take a look at the form on the following pages. Don’t be intimidated by the number of columns or headings; several can be ignored by all but the most dedicated home roaster. Note that if you are consistent from session to session with roast-chamber temperature, quantity of coffee roasted, and quench method, you can obtain useful results by recording only five to six columns: the identity of the green coffee, the date of the roast, the final bean temperature (if your method permits), the elapsed time of the roast, the appearance of the roasted beans, and your tasting notes.

You may not know or care about the age of the beans. The temperature in the roasting chamber may not be measurable, or you may choose never to vary it once you start your experiments. Pyrolysis or first crack may come at about the same time if you are using a consistent method and roast-chamber temperature.

For advice on systematically tasting or cupping coffee see the list of tasting terms and the afterword on cupping here.

Sample Home-Roasting Log

Note that “roast ’em till they’re brown” improvisors don’t need to fool with charts like this one. Also note that not all columns are relevant to all roasting methods; fill in the columns that tell you what you need to know. Finally, be prepared to accept the fact that no matter how consistent you are, roasts still will differ from session to session. Home-roasting methods are still too offhand to permit systematic compensation for subtleties like changes in atmospheric pressure and variations in green-bean density. Tasting and making observations about surface oils are activities ideally carried out the day following the roast. The examples are meant to suggest how the form might be used.

Home-Roasting Log

![]()